Abstract

The etiology of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD) is unknown. Recent epidemiological studies suggest that exposure to high levels of ozone (O3) may be a risk factor for LOAD. Nonetheless, whether and how O3 exposure contributes to AD development remains to be determined. In this study, we tested the hypothesis that O3 exposure synergizes with the genetic risk factor APOEε4 and aging leading to AD, using male apoE4 and apoE3 targeted replacement (TR) mice as men have increased risk exposure to high levels of O3 via working environments and few studies have addressed APOEε4 effects on males. Surprisingly, our results show that O3 exposure impairs memory in old apoE3, but not old apoE4 or you ng apoE3 and apoE4, male mice. Further studies show that old apoE4 mice have increased hippocampal activities or expression of some enzymes involved in antioxidant defense, diminished protein oxidative modification and neuroinflammation following O3 exposure, compared to old apoE3 mice. These novel findings highlight the complexity of interactions between APOE genotype, age, and environmental exposure in AD development.

Keywords: Ozone, APOE genotype, aging, oxidative stress, Alzheimer’s disease

Graphical abstract:

Cyclic O3 exposure synergizes with aging leading to memory impairment in apoE3, but not apoE4, targeted replacement male mice.

1. INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), a neurodegenerative disease, is a major cause of dementia in the elderly. Despite extensive studies, there is no effective treatment due, in part, to an incomplete understanding of its etiology and pathogenesis. Early-onset (familial) AD, which accounts for less than 5% of AD cases, is attributed to mutations in the genes coding for amyloid beta precursor protein (APP) or presenilin (PS). The causes for the majority (>95%) of AD cases (sporadic), which occurs after age 65 (late-onset Alzheimer’s disease, LOAD), however, are known. Human apolipoprotein E (apoE), existing in three isoforms (apoE2, apoE3, and apoE4), encoded by 3 distinct alleles ε2, ε3, and ε4, is a major carrier of lipids and cholesterol. Both epidemiologic and animal studies indicate that the APOEε4 allele, carried by approximately 15% of the population worldwide (Eisenberg, et al., 2010,Singh, et al., 2006), is a major genetic risk factor for AD (Farrer, et al., 1997,Liu, et al., 2013,Raber, et al., 2000) and women carrying the APOEε4 allele are at highest risk (Altmann, et al., 2014,Farrer, et al., 1997,Riedel, et al., 2016,Ungar, et al., 2014). Yet, not all APOE ε4 carriers, even older women, develop AD, suggesting that other factors, including environmental exposures, must play a role.

Ozone (O3), a highly reactive oxidant, is one of the most abundant urban pollutants. Unfortunately, over 30% of the US population lives in areas with unhealthy levels of O3 (American Lung Association State of the Air 2012). In addition, some workers (e.g., pulp mill and outdoor construction workers) are intermittently exposed to relatively high levels of O3 through their working environments (Chan and Wu, 2005,Henneberger, et al., 2005). Although the lung is a primary target, several studies, including our own, have shown that O3 exposure induces oxidative stress in the brain and impairs memory in rats (Hernandez-Zimbron and Rivas-Arancibia, 2015,Rivas-Arancibia, et al., 2010) and in genetically predisposed (APP/PS1 double transgenic) mice (Akhter, et al., 2015). Importantly, recent epidemiologic studies show a positive correlation between O3 levels and the incidence of AD (Chen and Schwartz, 2009,Cleary, et al., 2018,Gatto, et al., 2014,Jung, et al., 2015,Wu, et al., 2015). Nonetheless, whether O3 is a culprit for AD and whether O3 acts alone or synergizes with other risk factors such as APOEε4 and aging leading to AD remains to be determined.

Humanized or targeted replacement (TR) apoE4 and apoE3 mice, in which the endogenous murine APOE gene is replaced with human APOEε4 or APOEε3 (common human form) gene, respectively (Knouff, et al., 1999), are useful tools to study the mechanisms whereby APOEε4 modulates AD pathophysiology. As in humans, the APOEε4 allele mainly affects the memory of female mice under unchallenged conditions (Bour, et al., 2008,Raber, et al., 2000,Rijpma, et al., 2013,Villasana, et al., 2006). Consequently, most studies have used female apoE4 TR mice and very few have interrogated the effects of APOEε4 on male disease susceptibility. As men have increased risk to be exposed to elevated levels of O3 through their working environment (e.g. outdoor construction and pulp mills), the present studies used male apoE3 and apoE4 TR mice to test the hypothesis that O3 exposure synergizes with APOEε4 and/or aging to cause memory impairment. Moreover, we measured the levels of antioxidants glutathione and cysteine, the activities or expression of enzymes involved in antioxidant defense, protein oxidative modifications, and neuroinflammatory responses to further explore the potential mechanisms underlying O3-induced memory impairment.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Animals and ozone exposure:

Ten to twelve week-old male apoE4 and apoE3 TR mice, in which the endogenous murine APOE gene is replaced with human APOEε4 and APOEε3 gene, respectively (Knouff, et al., 1999), were purchased from Taconic and aged in UAB animal facility. The APOE genotype of the mice was confirmed by PCR and DNA sequencing as described (Hixson and Vernier, 1990). Three- and seventeen-month old apoE3 and apoE4 mice were exposed to a series of O3 exposure cycles, consisting of 5 days of O3 exposure (0.8 ppm, 7 hours/day ) followed by 9 days of filtered air (FA) recovery, for 8 cycles at the UAB Environmental Exposure Facility, as we have described previously (Akhter, et al., 2015,Katre, et al., 2011). FA controls were treated identically and were done in parallel to O3 exposed mice. Fourteen to sixteen mice were used for each genotype, age, and treatment group (total 120 mice for 8 groups). A 0.8 ppm O3 dose was used as rodents are insensitive to O3 insult due to obligatory nose breathing and other intrinsic factors, and as 0.2-0.3 ppm O3 is frequently achieved in highly polluted areas whereas a factor 3 is accepted practice to extrapolate O3 dose from rodents to human [Air Quality Criteria for Ozone and Related Photochemical Oxidants (Final). US Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC. EPA/600/R-05/004aF-cF, 2006] (Mumaw, et al., 2016,Ren, et al., 2008). A 5-day on and 9-day off exposure protocol was used to mimic what occurs in urban settings wherein several days of elevated O3 are usually followed by longer periods of ‘clean’ air. Animals were allowed free access to water whereas food was withheld during exposures to prevent ingestion of chow constituents oxidized by O3, which could introduce confounders. All procedures involving animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

2.2. The open field and zero maze tests:

After termination of O3 exposure at the end of 8 cycles, the open field test and then the zero maze test were conducted to assess general activity and anxiety levels of mice as described previously (Akhter, et al., 2015,Akhter, et al., 2018). The time spent in the center or at the sides in the open field test as well as in the closed or open area in the zero maze test were recorded using a camera driven tracker system (Ethovision XT11, Noldus).

2.3. Water maze test:

Following the open field and zero maze tests (next day), learning and memory was assessed by the well-established, hippocampus-dependent Morris water maze at UAB behavioral assessment core facility as described previously (Akhter, et al., 2015,Akhter, et al., 2018). During day 1 through day 5 of the training period, the mice were placed in the water basin next to and facing the wall successively in north (N), east (E), south (S), and west (W) positions (4 trials/day/mouse with the inter-trial interval of 2 min). The hidden platform was placed 0.5 cm below the water surface at the southeast (SE) quadrant. All mice were tested on the same day in a counterbalanced order. The escape latencies (from the time mice were placed into the water till they found the platform), swim path-lengths (distances), and swim speeds were recorded simultaneously with a camera driven tracker system (Noldus Ethovision system, version 7.1). On the day 5, probe trials were conducted after water maze tests by removing the platform and recording the time each mouse spent in each quadrant in a 1 min trial.

2.4. Tissue collection:

After memory tests, mice were euthanized by overdosing with isoflurane, followed by bilateral thoracotomy; blood was withdrawn from the heart, followed by transcardial perfusion (Liu, et al., 2011). The brain was dissected sagittally into right and left hemispheres with the right hemisphere fixed in 10% PBS buffered formalin and the left hemisphere dissected and the hippocampus and cerebral cortex frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately for subsequent biochemical analyses.

2.5. HPLC analyses of low molecular weight antioxidants in the hippocampus:

The hippocampus was homogenized with 5% perchloric acid/0.2 M Boric acid/10uM γ-glutamylglutamate (internal standard) solution (100 μl buffer/10 mg tissue) as described previously (Jones and Liang, 2009). Glutathione (GSH), glutathione disulfide (GSSG), cysteine (Cys), and cystine (Cyss) levels in the hippocampus were measured using a well-established HPLC method (Jones and Liang, 2009), calculated based on the standard curves run simultaneously with samples, and normalized by protein content. The total amount of GSH or cysteine was calculated based on the following equation: total [GSH]/[cysteine]=[GSH]/[cysteine] + 2 × [GSSG]/[cystine].

2.6. Analyses of enzyme activities:

Total activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD) in hippocampal homogenates was measured using a kit from Sigma (catalog number 19160-1KT), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Catalase activity was determined using a fluorescence-based method as described previously (Ando, et al., 2008). Activities of thioredoxin8 1 (Trx1) and thioredoxin reductase 1 (TXNRD1) were assessed under non-reducing conditions using a Kit from Cayman (catalog number 11526) as we have described before (Li, et al., 2016). The activity of glutathione peroxidase was assessed following the protocol described previously (Flohe and Gunzler, 1984).

2.7. Western analyses of specific proteins:

For Western analysis of the abundances of specific proteins, mouse hippocampus was homogenized in a buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 250 mM sucrose, 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.1 mM of diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA), and protease inhibitor cocktail. DTPA was used to block adventitious iron-mediated sample auto-oxidation. For analysis of proteins modified by 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE), a lipid peroxidation product, or by glutathione (glutathionylation), equal amounts of proteins (50 μg) from each sample were subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis using non-reducing buffers, and the proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membrane using Trans-blot Turbo system (Bio-Rad) at room temperature for 2 hours. The membranes were then blocked with 5% milk and probed with anti 4-HNE antibody (alpha Diagnostic, HNE-11S, 1:1000 dilution). The membranes were then stripped with a mild stripping buffer containing no reducing agent and reprobed with anti-GSH antibody (Virogen, 101-A-100,1:1000 dilution). For analyses of other proteins, 50 μg of proteins were subjected to 4-20% gel electrophoresis under reducing conditions and proteins transferred to nitrocellulose membranes as described above. The membranes were probed with antibodies to glial fibrillary acid protein (GFAP, Sigma, G9269, 1:1000 dilution), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα, Santa Cruz, sc52746, 1:500 dilution), glutaredoxin 1 (abcam, ab45953, dilution 1:1000 dilution), and GAPDH (Santa Cruz sc47724, 1:2000 dilution). Semi-quantifications of band intensities were performed using Image J software and protein loading normalized by GAPDH.

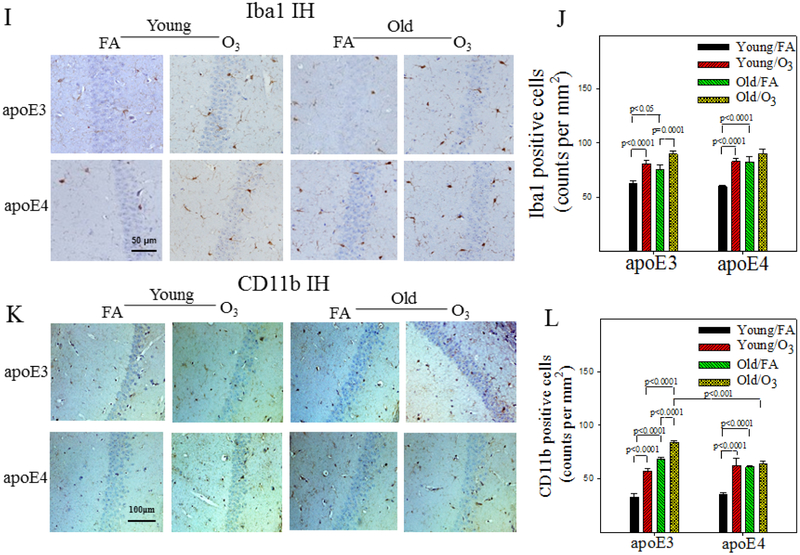

2.8. Immunostaining of activated astrocytes and microglia in the hippocampus:

Activated astrocytes were revealed by immunostaining of brain tissue sections with anti-GFAP antibody (Sigma, G9269, 1:500 dilution) and anti-aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family member L1 antibody (Aldh1L1, abcam, ab87117, 1:500 dilution). Microglia were revealed with antibodies to ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule 1 (Iba1, abcam, ab178847, 1:1000 dilution) and to CD11b (abcam, ab133357, 1:200 dilution). The numbers of activated astrocytes and microglia were counted in hippocampus and results expressed as numbers of cells/mm2.

2.9. Analysis of amyloid beta peptide (Aβ) deposition in the hippocampus:

Brain Aβ deposits (plaques) were assessed by immunohistochemical staining techniques using anti-mouse Aβ1-42 monoclonal antibody (Signet-39142). For the measurement of hippocampal Ab42 and Ab40, mouse hippocampus was homogenated in cell extraction buffer (FNN0011, Invitrogen) containing protease inhibitor cocktail and then extracted with guanidine hydroxide. After centrifugation, the amounts of Aβ42 and Aβ40 in the supernatant were quantified using the ELISA kits from Invitrogen, following the protocol provided by the manufacturer.

2.10. Statistical analysis:

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviations. T-tests were performed for the data presented in Fig 1A to compare body weights between unchallenged apoE3 and apoE4 mice at same age. Body weights were also compared by analysis of variance with two fixed factors (genotype and exposure) (2-factor AVONA) at the ages indicated (Fig 1B). For the memory function data presented in Fig 2A&2B, SAS version 9.4 was used for general linear model analysis with repeated measures to determine if changes in escape latencies over 5 days are different by experiment factors: genotype (apoE3 vs. apoE4), age (old vs. young), and exposure (FA vs. O3). The comparison was repeated for the evaluation of differences in escape latencies between two groups at the same level of genotype, age, or treatment. Because memory deficits usually become evident at day 5, we have also compared the escape latencies at day 5 using analyses of variance with three fixed factors (age, exposure, and genotype) (3-factor ANOVA), followed by Tukey's Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) post-hoc analysis. For the data presented in Fig 3-7 as well as in the supplementary figures, 3-factor ANOVA and HSD analyses were performed. The p values presented in the figures are from post-hoc analysis. Sample sizes are included in figure legends for each experimental measure.

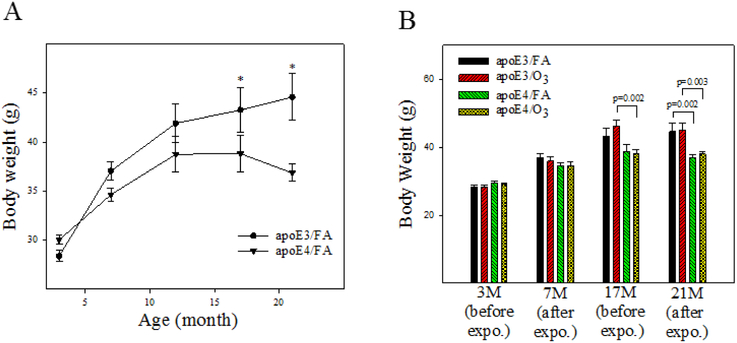

Figure 1. Effects of age and O3 exposure on body weights of male apoE3 and apoE4 TR mice.

A) Age-dependent increases in body weights of unchallenged apoE3 and apoE4 male mice. *, Significantly different from same ages of apoE4 mice (p<0.05, n=13-16). B) Effects of O3 exposure on body weights of apoE3 and apoE4 mae mice. Body weights were recorded at before and after 8 cycles of filtered air (FA) or O3 exposure (n=13-16).

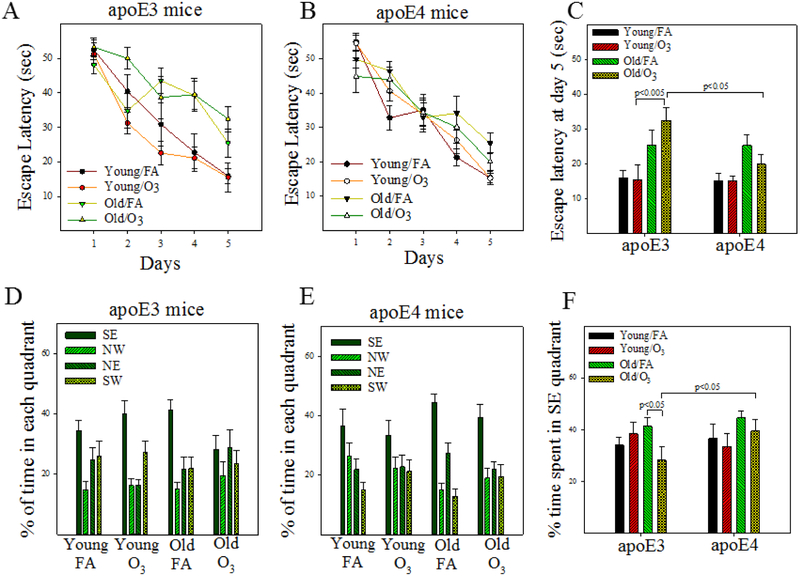

Figure 2. Effect of age and O3 exposure on memory of male apoE3 and apoE4 TR mice.

Memory function was assessed by Morris Water Maze (MWM) as described in the Materials and Methods section. A&B) Time-dependent changes in escape latencies of filtered air (FA) and O3 exposed young and old apoE3 (A) and apoE4 (B) mice. C) Escape latencies at the day 5 of MWM test. D-F) Probe trials were performed 24 hours after MWM test and the percentage of time spent in south east (SE), north west (NW), north east (NE), and south west (SW) quadrants are presented in D (apoE3) and E (apoE4) panels while the times spent in SE (the correct) quadrant are summarized in panel F. Statistical analyses were performed using general linear models with repeated measures and three fixed factors (age, exposure, and genotype) as described in the Material and Method section. The p-values are from Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) post-hoc analyses (n = 13-16).

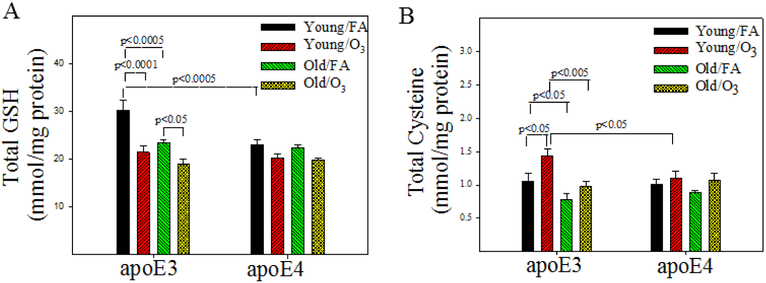

Figure 3. Effect of age, APOE genotype, and O3 exposure on the concentrations of total GSH and cysteine in the hippocampus.

The amounts of GSH, gluthione disulfide (GSSG), cysteine, and cystine in mouse hippocampus were measured by HPLC and normalized by protein as described in Materials and Methods section. The total amounts of GSH (A) and cysteine (B) were calculated according to the equation: [GSH]/[cysteine] = [GSH]/[cysteine] + 2 × [GSSG]/[cysteine]. The results were analyzed by 3-factor ANOVA and the p-values are from Tukey post-hoc analyses (n=8).

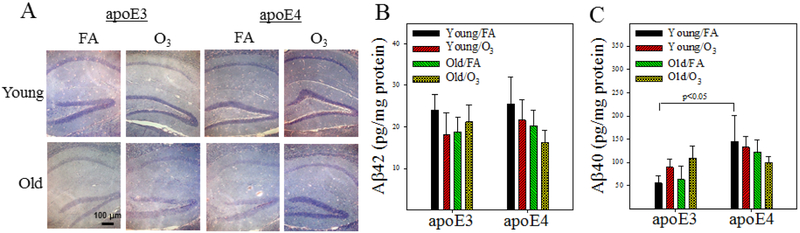

Figure 7. Effect of age and O3 exposure on Aβ deposition in the hippocampus of apoE3 and apoE4 TR male mice.

A) Representative immunostaining pictures of Aβ plaque in the hippocampus of mice; B&C) The amounts of guanidine soluble Aβ42 and Aβ40 in the hippocampus were determined by ELISAs. The results were analyzed by 3-factor ANOVA and the p-values are from Tukey post-hoc analyses (n=8).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Effects of age and O3 exposure on the body weights of male apoE3 and apoE4 TR mice

Mouse body weights were determined at 3, 7, 12, 17, and 21 months of age and every week during the O3 exposure period. Results show that, under unchallenged conditions (FA exposure), male apoE3 mice have significantly greater body weights than male apoE4 mice at 17 and 21 months of age (Fig 1A). Two-factor ANOVA further identifies a significant effect of genotype, but not O3 exposure, on the body weights at 17 and 21 months of age (Table 1 and Fig 1B). O3 exposure also has no immediate effect on body weights, measured right after each exposure cycle (data not shown).

Table 1.

Two-factor ANOVO of body weights at different ages

| Ages | Genotype | O3 | Genotype x O3 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | P value | F | P value | F | P value | |

| 3 months | 2.975 | 0.091 | 0.254 | 0.617 | 0.058 | 0.811 |

| 7 months | 3.017 | 0.089 | 0.309 | 0.581 | 0.243 | 0.625 |

| 17 months | 12.037 | 0.001 | 0.374 | 0.543 | 1.079 | 0.303 |

| 21 months | 20.309 | <0.001 | 0.265 | 0.608 | 0.032 | 0.859 |

3.2. Effect of age and O3 exposure on memory of male apoE3 and apoE4 TR mice

To test whether O3 exposure synergizes with ApoEε4 and aging to impair memory, we exposed 3- and 17-month old male apoE4 mice to a cyclic O3 exposure protocol, which mimics human exposure scenarios, and compared the results to age-matched male apoE3 mice. Statistical analyses (performed using a general linear model with repeated measures) show that the trends of escape latency decline over 5 days of water maze test are significantly different overall among 8 groups [F(28,416)=2.21, p=0.0007]. Subgroup analyses identify a significant difference in the trends of escape latency decline between FA and O3 exposed old apoE3 mice (F(4, 112)=2.27, p=0.0332; treatment effect, p=0.1146; day effect, p=0.0005). There is no significant difference in the trends between the other groups (Fig 2A&B). As memory deficits usually become evident at day 5, we also analyzed the day 5 escape latency data using 3-factor ANOVA. Statistical analyses reveal significant effects of genotype and age on day-5 escape latencies (Table 2, Fig 2C). Post hoc analyses further show that the escape latencies at day-5 are significantly increased in O3 exposed old apoE3 mice when compared to O3-exposed young apoE3 mice and O3-exposed old apoE4 mice (Fig 2C). Statistical analyses of probe trial data also show that O3 exposed old apoE3 mice spend significantly shorter time in the SE (correct) quadrant than do FA exposed old apoE3 mice and O3 exposed old apoE4 mice (Fig 2D-F). These data suggest that O3 exposure synergizes with age leading to impairment of learning/memory in male apoE3, but not male apoE4, mice.

Table 2.

Three -factor ANOVA of day-5 escape latency, probe trial, open field (OF) and zero maze (ZM) tests

| Genotype | O3 | Age | Genotype x O3 |

Genotype x Age |

O3 x Age |

Genotype x Age x O3 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F(1, 104) | P | F(1, 104) | P | F(1, 104) | P | F(1, 104) | P | F(1, 104) | P | F(1, 104) | P | F(1, 104) | P | |

| Day-5 escape latency | 8.48 | 0.0044 | 0.34 | 0.5605 | 6.43 | 0.0127 | 2.14 | 0.1468 | 3.55 | 0.0625 | 0.05 | 0.8277 | 1.24 | 0.2678 |

| Probe trial | 0.25 | 0.6211 | 3.40 | 0.0679 | 2.09 | 0.1517 | 0.13 | 0.7159 | 3.81 | 0.0537 | 1.47 | 0.2284 | 2.94 | 0.0895 |

| OF test (at the side) | 43.6 | <0.001 | 0.53 | 0.4681 | 12.2 | 0.0007 | 0.22 | 0.6418 | 2.49 | 0.1179 | 0.00 | 0.9445 | 0.05 | 0.8243 |

| ZM test (in open area) | 39.1 | <0.001 | 0.37 | 0.5441 | 13.3 | 0.0004 | 0.45 | 0.5062 | 0.39 | 0.5349 | 0.27 | 0.6054 | 5.27 | 0.0237 |

No significant difference is observed in swimming speeds between O3 and FA exposed mice, apoE3 or apoE4, although swimming speeds are slightly higher in old vs. young mice (Supplementary Fig 1A&B). Three-factor ANOVA of the data from open field and zero maze tests identifies significant effects of genotype and age, but not O3 exposure, on anxiety levels (Table 2, Supplementary Fig 2). Post hoc analyses further show that, compared to age-matched male apoE3 mice, both young and old male apoE4 mice have higher levels of fear/anxiety, as indicated by significantly less time spent in the center in the open field test (Supplementary Fig 2B) and in the open area in the zero maze test (Supplementary Fig 2D). There is no effect of age on the anxiety level of apoE4 mice (Supplementary Fig 2C&D). Age effect on anxiety levels in apoE3 mice is uncertain as old apoE3 male mice spend less time in the center in the open field test (higher anxiety) (Supplementary Fig 2B) but more time in the open area in the zero maze test (less anxiety) (Supplementary Fig 2D), compared to young apoE3 mice. O3 exposure alone does not increase fear/anxiety levels in young or old mice of either genotype. Together, the results suggest that the increased escape latency in the water maze test and the decreased retention time in the correct quadrant in the probe trial in O3 exposed old apoE3 mice is not due to a decline in motor activity or an increase in anxiety level.

3.3. Effects of age, APOE genotype, and O3 exposure on the concentrations of total glutathione and cysteine in the hippocampus

Glutathione (GSH) is the most abundant intracellular free thiol and an important antioxidant, whereas cysteine is a rate-limiting substrate for GSH synthesis. To explore the mechanism whereby O3, a highly reactive oxidant, impairs memory of old apoE3 mice, we measured the total amounts (reduced and oxidized) of GSH and cysteine in the hippocampus by HPLC. Three-factor ANOVA reveals significant effects of genotype, O3 exposure, and age on GSH levels as well as O3 exposure and age on cysteine levels (Table 3). There are significant interactions between genotype and age on both GSH and cysteine levels (Table 3). Post hoc analyses further show that the basal level of GSH in young apE4 mice is significantly lower than that in young apoE3 mice; apoE3, not apoE4, mice, however, experience significant age- and O3 exposure-related decline in GSH concentrations (Fig 3A). Cysteine levels decrease with increased age in apoE3, not apoE4, mice (Fig 3B), whereas O3 exposure increases cysteine level in young apoE3 (Fig 3B).

Table 3.

Three -factor ANOVA of antioxidants in the hippocampus

| Genotype | O3 | Age | Genotype x O3 |

Genotype x Age |

O3 x Age |

Genotype x Age x O3 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F(1, 63) | P | F(1, 63) | P | F(1, 63) | P | F(1, 63) | P | F(1, 63) | P | F(1, 63) | P | F(1, 63) | P | |

| Total GSH | 10.12 | 0.0024 | 36.8 | <0.001 | 10.1 | 0.0025 | 2.36 | 0.1299 | 4.31 | 0.0425 | 1.12 | 0.2955 | 1.59 | 0.2120 |

| Total Cysteine | 0.33 | 0.5706 | 9.90 | 0.0026 | 10.6 | 0.0019 | 1.04 | 0.3124 | 4.39 | 0.0407 | 0.04 | 0.8496 | 0.89 | 0.3505 |

| SOD activity | 8.65 | 0.0044 | 2.97 | 0.0890 | 3.91 | 0.0519 | 0.25 | 0.6204 | 0.04 | 0.8331 | 3.14 | 0.0805 | 5036 | 0.0234 |

| Catalase activity | 1.08 | 0.3011 | 2.13 | 0.1488 | 9.06 | 0.0036 | 0.63 | 0.4312 | 0.15 | 0.6965 | 0.48 | 0.4920 | 1.52 | 0.2217 |

| Trx1 activity | 22.6 | <0.001 | 0.35 | 0.5538 | 28.9 | <0.001 | 1.21 | 0.2760 | 8.31 | 0.0056 | 0.61 | 0.4375 | 0.15 | 0.7017 |

| TXNRD1 activity | 0.97 | 0.3300 | 8.49 | 0.0052 | 49.7 | <0.001 | 8.58 | 0.0050 | 5.26 | 0.0258 | 8.00 | 0.0066 | 1.30 | 0.2586 |

| GPx | 3.62 | 0.0644 | 2.48 | 0.1229 | 2.35 | 0.1331 | 0.19 | 0.6663 | 2.67 | 0.1100 | 2.68 | 0.1097 | 1.09 | 0.3032 |

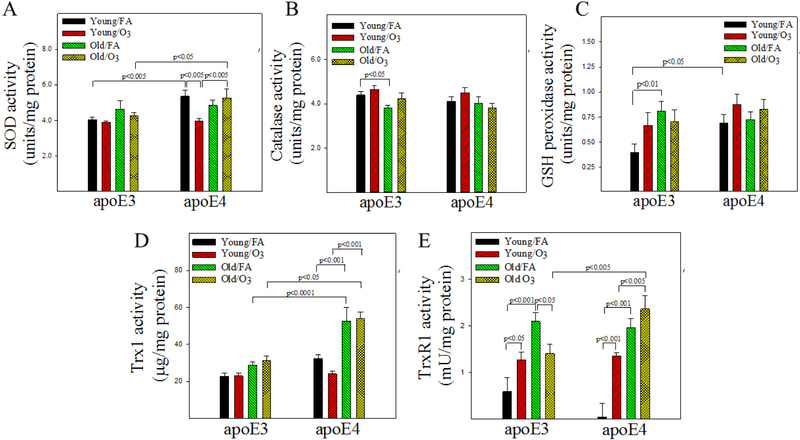

3.4. Age- and O3 exposure-dependent changes in the activities of enzymes involved in antioxidant defense in the hippocampus of male apoE3 and apoE4 TR mice

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase are responsible for the reduction of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide, respectively, whereas glutathione peroxidase (GPx) reduces hydrogen peroxide and lipid peroxide. In addition to their role in hydroperoxide reduction, thioredoxin 1 (Trx1) and thioredoxin reductase 1 (TXNRD1) also contribute to protein thiol maintenance by reducing protein disulfide bonds formed during oxidative stress. Thus, we measured the activities of these enzymes in the hippocampus to further explore the mechanism underlying O3 induced memory impairment in old apoE3 mice. Three-factor ANOVA show significant effects of genotype on SOD activity, age on catalase activity, genotype and age on Trx1 activity, as well as age and O3 exposure on TXNRD1 activity (Table 3). There are significant interactions between genotype, age, and exposure on SOD, Trx1, and TXNRD1 activities (3 factors or 2 factors interact) (Table 3). Post hoc analyses further show that basal SOD activity in FA exposed mice is significantly higher in young apoE4 mice compared to young apoE3 mice and remains elevated even after O3 exposure (Fig 4A). Catalase activity is decreased with increased age in apoE3, but not apoE4, mice (Fig 4B). GPx activity is significantly higher in young apoE4 and old apoE3 mice compared to young apoE3 mice under unchallenged condition (Fig 4C). Trx 1 activity is significantly higher in old apoE4 mice when compared to other groups, with or without O3 exposure (Fig 4D). TXNRD1 activity, on the other hand, is increased with age in both apoE3 and apoE4 mice and in O3 exposed young mice. O3 exposure, however, significantly reduces TXNRD1 activity in old apoE3, but not old apoE4, mice (Fig 4E). Together, the results suggest that some antioxidant defense mechanisms are up-regulated in the hippocampus of male apoE4 mice, especially old apoE4 mice.

Figure 4. Effect of age, APOE genotype, and O3 exposure on the activities of antioxidant enzyems in the hippocampus.

The activities of total superoxide dismutase (SOD) (A), catalase (B), thioredoxin 1 (Trx1) (C), thioredoxin reductase 1 (TXNRD1) (D), and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) (E) in mouse hippocampus tissue were measured as described in the Materials and Methods section. The results were analyzed by 3-factor ANOVA and the p-values are from Tukey post-hoc analyses (n=6-10).

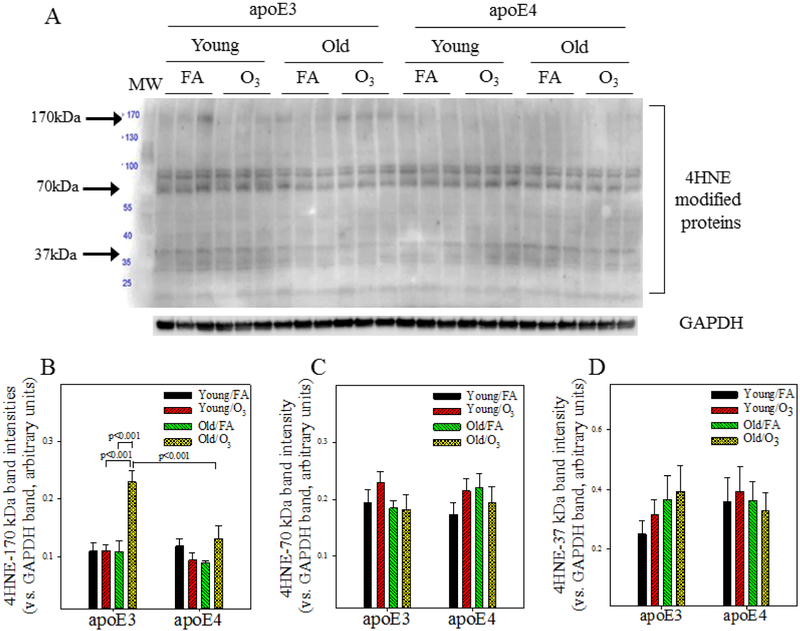

3.5. Age- and O3 exposure-dependent protein oxidative modifications in the hippocampus of male apoE3 and apoE4 TR mice

To further assess oxidative stress responses in these mice, we determined the levels of proteins that are modified by 4-hydroxynonenonal (4HNE), a lipid peroxidation product, and by GSH (glutathionylation) in the hippocampus. Three-factor ANOVA reveals significant effects of O3 exposure and age on the levels of 4HNE-modified proteins as well as effects of genotype, O3 exposure, and age on the levels of glutathionylated proteins (Table 4). Post hoc analyses further show that the levels of 4-HNE-modified proteins at 170 kDa size are significantly higher in the hippocampus of O3 exposed old apoE3 male mice when compared to other groups of mice (Fig 5A&B). There is no significant difference in the amounts of 4HNE-modified proteins at sizes of 70 kDa or 37 kDa (Fig 5A&C&D). The levels of glutathionylated proteins at 170 kDa and 130 kDa are significantly higher in O3 exposed old apoE3 mice when compared to mice in other groups (Fig 5E-G). A smaller but statistically significant increase in 170 kDa glutathionylated proteins is also detected in O3 exposed old apoE4 mice when compared to FA exposed old apoE4 and young O3 exposure apoE4 mice (Fig 5E&F).

Table 4.

Three -factor ANOVA of protein oxidative modifications in the hippocampus

| Genotype | O3 | Age | Genotype x O3 |

Genotype x Age |

O3 x Age |

Genotype x Age x O3 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F(1, 40) | P | F(1, 40) | P | F(1, 40) | P | F(1, 40) | P | F(1, 40) | P | F(1, 40) | P | F(1, 40) | P | |

| 4HNE170kDa band | 3.21 | 0.0808 | 13.1 | 0.0008 | 6.96 | 0.0118 | 3.95 | 0.0537 | 8.82 | 0.0050 | 22.0 | <0.001 | 2.39 | 0.1303 |

| GSH130kDa band | 16.3 | 0.0002 | 19.9 | <0.001 | 52.4 | <0.001 | 0.78 | 0.3837 | 12.9 | 0.0009 | 6.72 | 0.0133 | 5.94 | 0.0194 |

| GSH170kDa band | 27.1 | <0.001 | 10.5 | 0.0024 | 40.7 | <0.001 | 0.91 | 0.3447 | 3.08 | 0.0868 | 28.2 | <0.001 | 5.02 | 0.0306 |

| Glrx1 Westerns | 61.8 | <0.001 | 0.12 | 0.7350 | 7.68 | <0.001 | 2.36 | 0.1324 | 5.30 | 0.0266 | 6.07 | 0.0182 | 4.64 | 0.0372 |

Figure 5. Effect of age and O3 exposure on protein oxidative modifications and glutaredoxin 1 protein expression in the hippocampus of male apoE3 and apoE4 TR mice.

A-D, 4HNE-modified proteins; E-H, GSH-modified proteins (glutathionylation). Top Panels (A&E): representative Western blots; Bottom panels (B-D and F-H): semi-quantifications of the intensities of the bands as indicated by arrows after normalized to corresponding GAPDH band using Image J software. I&J) Western blots of glutaredoxin 1 (Glrx1) protein in mouse hippocampus. GAPDH was used to normalize sample loading. The quantitative results are from 6 samples per group. Statistical analyses were performed by 3-factor ANOVA and the p-values are from Tukey post-hoc analyses (n=6)

To explore possible mechanisms underlying differences in protein glutathionylation, we assessed hippocampal expression of glutaredoxin1 (Glrx1), an enzyme that catalyzes the reduction of glutathionylated proteins. Three-factor ANOVA reveals significant effects of genotype and age on hippocampal Glrx1 protein levels and an interaction between genotype, exposure, and age (Table 4). Post hoc analyses further show that O3 exposure significantly increases hippocampal Glrx1 protein levels in young apoE4, but not young apoE3, male mice (Fig 5I&J), and that Glrx1 protein levels are significantly higher in old apoE4 than in old apoE3 male mice, with or without O3 exposure (Fig 5I&J). Together, the data suggest that up-regulation of some antioxidant defense mechanism may render male apoE4 mice higher resistance to O3-induced oxidative stress.

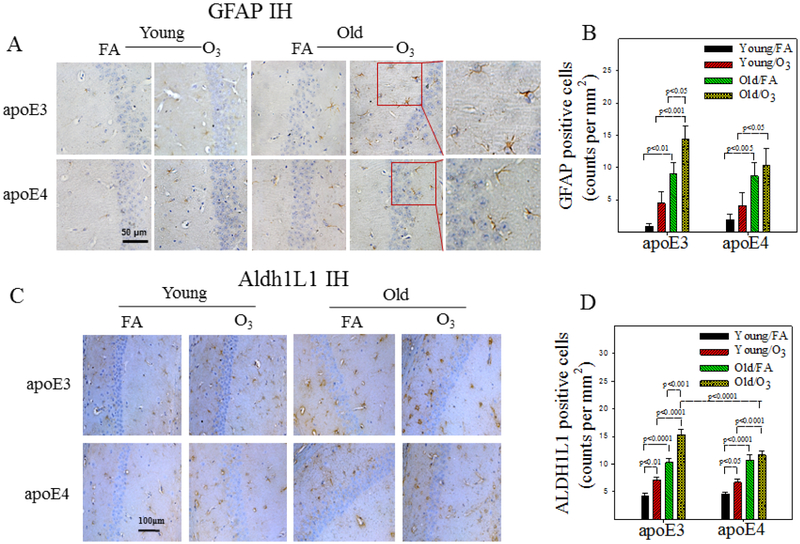

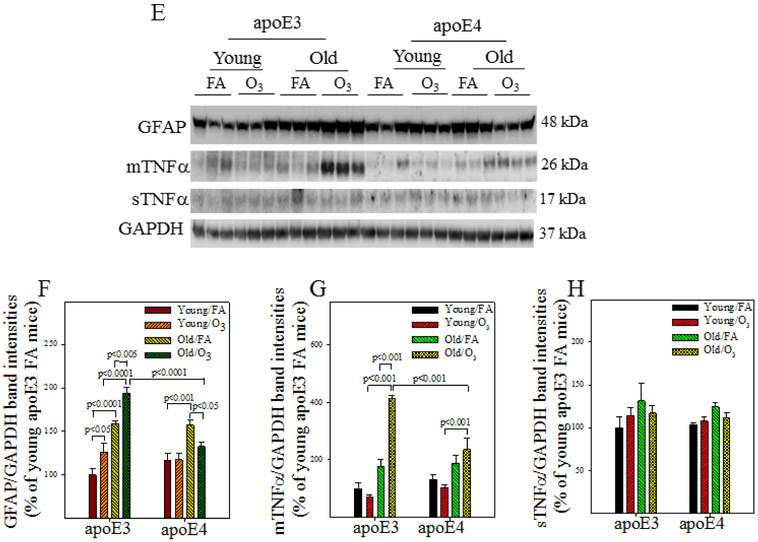

3.6. Effect of age and O3 exposure on neuroinflammation in the hippocampus of male apoE3 and apoE4 TR mice

Astrocytes and microglia play important role in neuroinflammatory response. To assess astrocyte and microglia activation, brain tissue sections were immuno-stained with antibodies to GFAP and Aldh1L1, two astrocyte markers, or with antibodies to Iba1 and CD11b, two microglia markers. Hippocampal proteins of GFAP and TNFα were also assessed by Western blotting. Three-factor ANOVA reveals significant effects of genotype, age, and exposure on astrocyte activation and TNFα protein expression (Table 5). Post hoc analyses further show that there are significant age-dependent increases in the numbers of GFAP (Fig 6A&B) or Aldh1L1 (Fig 6C&D) positive cells in FA exposed apoE3 and apoE4 mice. O3 exposure, however, further promotes astrocyte activation in aged apoE3, but not aged apoE4, male mice (Fig 6A-D). Western blotting data further show that the amount of GFAP protein increases with age in both apoE3 and apoE4 mice (Fig 6E&F). O3 exposure, on the other hand, further increases GFAP expression in old apoE3, not apoE4, mice. Western data also show that the amounts of membrane bound TNFα (mTNFα) increase more in O3 exposed old apoE3 mice compared to O3 exposed old apoE4 mice, although there is no significant difference in the amounts of soluble TNFα (sTNFα) between any groups (Fig 6E&G&H). Three-factor ANOVA also reveals significant effects of genotype, age, and exposure on the number of Iba1 or CD11b positive cells and an interaction between 3 factors (Table 5). Post hoc analyses show that the numbers of Iba1 and/or CD11b positive cells increase with age in the hippocampus of FA exposed apoE3 and apo4 mice (Fig 6I-L). O3 exposure, on the other hand, significantly increases Iba1 and/or CD11b positive cell counts in young apoE3 and apoE4 mice as well as in old apoE3 mice (Fig 6I-L). Together, the results suggest that astrocytes and microglia are activated without challenge in both apoE3 and apoE4 male mice; O3 exposure, however, further activates these cells and increases inflammatory response in old apoE3, but not old apoE4, male mice.

Table 5.

Three -factor ANOVA of neuroinflammation markers in the hippocampus

| Genotype | O3 | Age | Genotype x O3 |

Genotype x Age |

O3 x Age |

Genotype x Age x O3 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F(1, 40) | P | F(1, 40) | P | F(1, 40) | P | F(1, 40) | P | F(1, 40) | P | F(1, 40) | P | F(1, 40) | P | |

| GFAP | ||||||||||||||

| Western | 7.47 | 0.0093 | 3.54 | 0.0674 | 80.1 | <0.001 | 17.76 | <0.001 | 12.41 | 0.0011 | 0.64 | 0.4302 | 2.94 | 0.0942 |

| IH | 0.14 | 0.7149 | 21.6 | <0.001 | 45.1 | <0.001 | 0.36 | 0.5493 | 0.18 | 0.6712 | 7.84 | 0.0075 | 0.05 | 0.8320 |

| TNFα protein | 4.77 | 0.0349 | 18.3 | <0.001 | 90.2 | <0.001 | 12.81 | <0.001 | 10.58 | 0.0023 | 25.27 | <0.001 | 6.87 | 0.0123 |

| ALDH1L1 IH | 2.68 | 0.1081 | 30.1 | <0.0001 | 159 | <0.0001 | 5.52 | 0.0230 | 2.23 | 0.1415 | 0.25 | 0.6205 | 2.68 | 0.1081 |

| Iba 1 IH | 1.40 | 0.2439 | 65.3 | <0.0001 | 26.8 | <0.0001 | 1.01 | 0.3209 | 5.06 | 0.0301 | 10.8 | 0.0021 | 6.71 | 0.0133 |

| CD11b IH | 4.62 | 0.0367 | 64.4 | <0.0001 | 101 | <0.0001 | 1.19 | 0.2815 | 14.9 | 0.0003 | 13.4 | 0.0006 | 3.15 | 0.0822 |

Figure 6. Effects of age and O3 exposure on inflammatory responses in the hippocampus of male apoE3 and apoE4 TR mice.

A&B) Representative pictures of hippocampal immunostaining and quantitative data of GFAP positive cells. C&D) Representative pictures of hippocampal immunostaining and quantitative data of Aldh1L1 positive cells. E-H) Representative Western blot pictures of GFAP, mTNFα, and sTNFα proteins as well as semi-quatification of the band intensities. GAPDH was used to normalize sample loading. I&J) Representative immunostaining and quantification of Iba1 positive microglia in the hippocampus. K&L) Representative immunostaining and quantification of CD11b positive microglia in the hippocampus. The results were compared between 8 groups by 3-factor ANOVA and the p-values are from Tukey post-hoc analyses (n=6-7).

3.7. Hippocampal amyloid load in O3 exposed male apoE3 and apoE4 TR mice

The amyloid cascade theory of AD remains controversial. To elucidate whether memory impairment in O3 exposed old apoE3 mice was associated with an increase in brain Aβ load, we measured the amounts of Aβ42 and Aβ40 as well as Aβ plaques in the hippocampus of apoE3 and apoE4 male mice by ELISAs and immunohistochemical staining. The results show no obvious Aβ plaque in the brain of any group of mice (Fig 7A). There is also no significant difference in the amounts of Aβ42 between any groups, although there is a trend of increase in the amounts of Aβ40 in FA exposed young apoE4 mice when compared to FA exposed young apoE3 mice (Fig 7B&C). O3 exposure has no significant effect on brain Aβ load in either genotype or aged mice.

4. DISCUSSION

The etiology of LOAD, which accounts for >95% of AD cases, is unknown. Accumulated evidence suggests that LOAD results from complex interactions between genetic and environmental risk factors plus aging. The APOEε4 allele is a major genetic risk factor for LOAD with women APOEε4 carriers at greatest risk (Farrer, et al., 1997,Liu, et al., 2013,Raber, et al., 2000). Which environmental factor(s) contributes to the onset of LOAD, however, is unknown. Recent epidemiological studies show that exposure to high levels of O3 is associated with increased incidence of AD (Chen and Schwartz, 2009,Cleary, et al., 2018,Gatto, et al., 2014,Jung, et al., 2015,Wu, et al., 2015). Nonetheless, whether O3 is a culprit for AD and whether O3 acts alone or synergizes with other risk factors leading to AD remain to be determined. In this study, we tested the hypothesis that O3 exposure synergizes with APOEε4 and aging leading to the development of AD, using male apoE3 and apoE4 TR mice. Our results show, surprisingly, that O3 exposure synergizes with aging leading to memory impairment in male apoE3, but not apoE4, mice. These novel findings reveal a complex interaction between APOE genotype, aging, and environmental exposure in AD pathophysiology.

APOEε4 is a major genetic risk factor for AD and predominantly impacts the susceptibility of women (Altmann, et al., 2014,Farrer, et al., 1997,Riedel, et al., 2016,Ungar, et al., 2014). Animal studies using apoE TR mice have also shown that female, not male, apoE4 mice experience memory loss under unchallenged condition (Bour, et al., 2008,Raber, et al., 2000,Rijpma, et al., 2013,Villasana, et al., 2006). Consequently, most studies have used female mice to address the effects of APOEε4 on neuropathophysiology. Whether and how APOEε4 affects the response of males to challenges has received very little attention. The results from the present study show, unexpectedly, that APOEε4 protects old male mice from O3-induced memory loss. Whether this is a sex-specific response warrants further investigation. Interestingly, similar to our results, Peris-Sampedro at al. found that exposure to an organophosphate pesticide chlorpyrifos impaired spatial memory in male apoE3, not male apoE4, TR mice (Peris-Sampedro, et al., 2015). Using different exposure strategy, the same group further showed that postnatal chlorpyrifos exposure impaired spatial memory in apoE3 but not apoE4 female mice (Basaure, et al., 2019). Together, the results suggest that interaction between APOEε4 and environmental exposure is genotype, sex, and age dependent. It should be stressed that a recent epidemiologic study showed that APOEε4 carriers were more sensitive than non-APOEε4 carriers to O3-induced cognitive decline (Cleary, et al., 2018). However, as no sex-stratified data were reported, it was unclear whether the synergy was sex-related or not (Cleary, et al., 2018). So far, no study has addressed the sex-dependent interaction between APOEε4 and O3 exposure in AD pathophysiology in either human population or experimental animal models. More studies are warranted to answer these important questions.

The mechanism underlying selective effect of O3 exposure on memory of old male apoE3 mice is unclear. Given that O3 is a highly reactive oxidant, we assessed age and O3 exposure-related changes in the levels of antioxidants and oxidative stress in the hippocampus of these mice. Our data show that O3 exposed old apoE3 mice have significantly increased protein oxidative modifications than any other groups, consistent with memory impairment data. Our results further show that, although the basal level (FA exposure) of GSH is higher in young apoE3 mice compared to young apoE4 mice, both GSH and cysteine concentrations decline with age and with O3 exposure in apoE3, not apoE4, mice. Moreover, young male apoE4 mice have higher basal levels of SOD and GPx activities compared to young male apoE3 mice, whereas old apoE4 mice have higher activities of SOD, Trx1, and TXNRD1 as well as increased expression of Glrx1 compared to other groups, with or without O3 exposure. These data suggest that decreases in GSH and cysteine levels at old age may render male apoE3 mice highly sensitivity to O3-induced oxidative stress and memory impairment. ApoE4 mice, which have lower GSH since young, have developed some other compensatory mechanisms to combat O3-induced damaging effects. It should be stressed that, besides Trx and Glrx, other enzymes such as sulfiredoxin also play a critical role in maintaining protein thiol homoeostasis (Mishra, et al., 2015,Ramesh, et al., 2014). Whether the expression/activity of this protein is altered in apoE3 and/or apoE4 mice and contributes to increased resistance of apoE4 mice to O3-induced oxidative stress remains to be determined. It should also be pointed out, although it has been reported that oxidative stress level is higher and antioxidant levels are lower in APOEε4 positive AD patients compared to non-APOEε4 AD patients, none of these studies have addressed sex difference (Duits, et al., 2013,Glodzik-Sobanska, et al., 2009,Kharrazi, et al., 2008,Ramassamy, et al., 2000). The studies showing apoE4 TR mice have decreased antioxidant levels and increased sensitivity to oxidative challenge than apoE3 TR mice were all conducted with young female mice (Graeser, et al., 2011,Persson, et al., 2017,Villasana, et al., 2016). Collectively, the data from this lab and from others suggest that APOEε4-associated decline in the antioxidant levels may be age- and sex-dependent. Our results also suggest that oxidative modifications of the proteins that are critical for cell signaling and/or neuron survival may contribute to O3-induced memory impairment in old apoE3 male mice. Future studies are warranted to identify these redox sensitive proteins that contribute to increased sensitivity of old apoE3 mice to O3 induced memory impairment.

Besides oxidative stress, other aging- and/or genotype-related factors may also contribute to the increased sensitivity of old apoE3 male mice to O3-iduced memory impairment. One of these factors is inflammation. Neuroinflammation contributes importantly to neuronal damage, whereas astrocytes and microglia are the key players in neuro-inflammatory responses. Our data show that both astrocytes and microglia are activated with increased age in apoE3 and apoE4 mice. O3 exposure, however, further activates astrocytes and microglia in old apoE3, but not old apoE4, male mice. Our data are consistent with previous publications using non-O3 stimuli, which showed that apoE3 mice exhibited greater astrocyte activation upon LPS challenge compared to apoE4 mice (Maezawa, et al., 2006,Ophir, et al., 2003). The mechanism underlying the augmented response of astrocytes and microglia in old apoE3 male mice following O3 exposure is unclear at moment. As oxidative stress plays a critical role in inflammatory responses, it is speculated that increased oxidative stress likely contributes to augmented inflammatory response in old apoE3 mice. It should be mentioned, however, that some studies have shown increased inflammatory responses in apoE3 mice compared to apoE4 mice, although opposite observation has also been reported (Belinson and Michaelson, 2009,Liu, et al., 2013,Maezawa, et al., 2006,Ophir, et al., 2003,Zhu, et al., 2012). Therefore, it is possible that augmented inflammatory response drives excessive oxidative stress and thus memory impairment in O3 exposed old apE3 mice. Although we could not exclude this possibility, we believe that increased oxidative stress is more likely the driver of augmented inflammatory response and memory loss in old apoE3 mice as O3 is highly reactive oxidant. More studies are needed to address this issue.

Increased production and deposition of Aβ, due to APP and PS1/PS2 gene mutation, is believed to attribute importantly to the neuropathophysiology in familial AD, although the amyloid cascade theory of AD remains controversial. ApoEε4 has been shown to increase brain Aβ load in familial AD model mice (ApoE4xAPP mice) (Chan, et al., 2016,Tachibana, et al., 2019,Youmans, et al., 2012); very few studies, however, demonstrate Aβ plaques in the brain of apoE4 TR only mice. In a previous study, Sullivan et al. showed Aβ deposition in cerebral vessels in apoE4 TR mice (Sullivan, et al., 2008). In a recent study, Zhang et al. showed a positive staining for Aβ42 in the cortex of old (10 months) female, but not male, apoE4 TR mice (Zhang, et al., 2019). No Aβ plaques were detected in these studies. In this study, we show a slight increase in the amount of Aβ40 in the hippocampus of male apoE4 mice with no Aβ plaque. Nonetheless, the results from this study suggest that memory impairment observed in O3 exposed old male apoE3 mice is not caused by increased brain amyloidosis.

Obesity affects cognitive function through multiple mechanisms (Solas, et al., 2017,Sripetchwandee, et al., 2018,Toda, et al., 2014). Consistent with previous reports (Huebbe, et al., 2015), our data show that apoE3 male mice gain more body weight with increased age compared to apoE4 male mice. However, O3 exposure has no significant effect on age-dependent body weight gain in either genotype. Therefore, it is suggested that O3 exposure impairs memory in old apoE3 male mice not by increasing body wright. Our data also show that apoE4 mice have an increased anxiety level compared to apoE3 mice, which is consistent with the results reported by others (Meng, et al., 2017,Villasana, et al., 2016). O3 exposure, however, has no significant effect on anxiety levels of either genotype of mice, suggesting that O3 exposure impairs memory of old apoE3 mice not by increasing their anxiety.

In summary, the results from this study show, for the first time, that cyclic O3 exposure impairs memory in old apoE3, not old apoE4 or young apoE3 and apoE4, male mice. In other words, APOEε4, a well-established genetic risk for AD, protects old male mice from O3-induced memory impairment. This is associated with up-regulation of some antioxidant defense mechanisms in the hippocampus of apoE4 mice. The results from this study suggest complex interactions between APOE genotype, age, and environmental exposure in AD pathophysiology.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Effect of age and O3 exposure on swimming speed and swimming distance of male apoE3 and apoE4 TR mice. A) Swimming speeds of apoE3 mice; B) Swimming speeds of apoE4 mice. The results were analyzed by 3-factor ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc analyses. *, Significantly different from the corresponding young apoE3/apoE4 mice (p<0.05, n=13-16).

Supplementary Figure 2. Effect of age and O3 exposure on anxiety levels of male apoE3 and apoE4 TR mice. A&B) Open field test results: time spent at sides (A) or in the center (B). C&D) Zero maze test results: time spent in the close area (C) or in the open area (D). The results were analyzed by 3-factor ANOVA and the p-values are from Tukey post-hoc analyses (n=13-16).

Highlights:

Cyclic O3 exposure impairs memory in old male apoE3, but not apoE4, TR mice

Cyclic O3 exposure has no effect on memory in young male apoE3 or apoE4 TR mice

O3 induces severe oxidative stress & neuroinflammation in old male apoE3 mice

Some antioxidant enzymes are up-regulated in the hippocampus of apoE4 male mice

Old apoE4 mice are resistant to O3-induced oxidative stress & neuroinflammation

Acknowledgement:

The work was supported by the grants from National Institute of Health and National Institute of Aging to Rui-Ming Liu (HL088141 and AG046701).

Footnotes

Declaration: The authors declare they have no actual or potential competing financial interests

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Akhter H, Ballinger C, Liu N, van Groen T, Postlethwait EM, Liu RM 2015. Cyclic Ozone Exposure Induces Gender-Dependent Neuropathology and Memory Decline in an Animal Model of Alzheimer's Disease. Toxicol Sci 147(1), 222–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhter H, Huang WT, van Groen T, Kuo HC, Miyata T, Liu RM 2018. A Small Molecule Inhibitor of Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor-1 Reduces Brain Amyloid-beta Load and Improves Memory in an Animal Model of Alzheimer's Disease. J Alzheimers Dis 64(2), 447–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altmann A, Tian L, Henderson VW, Greicius MD, Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, I. 2014. Sex modifies the APOE-related risk of developing Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol 75(4), 563–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando T, Mimura K, Johansson CC, Hanson MG, Mougiakakos D, Larsson C, Martins da Palma T, Sakurai D, Norell H, Li M, Nishimura MI, Kiessling R 2008. Transduction with the antioxidant enzyme catalase protects human T cells against oxidative stress. J Immunol 181(12), 8382–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basaure P, Guardia-Escote L, Cabre M, Peris-Sampedro F, Sanchez-Santed F, Domingo JL, Colomina MT 2019. Learning, memory and the expression of cholinergic components in mice are modulated by the pesticide chlorpyrifos depending upon age at exposure and apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotype. Arch Toxicol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belinson H, Michaelson DM 2009. ApoE4-dependent Abeta-mediated neurodegeneration is associated with inflammatory activation in the hippocampus but not the septum. J Neural Transm 116(11), 1427–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bour A, Grootendorst J, Vogel E, Kelche C, Dodart JC, Bales K, Moreau PH, Sullivan PM, Mathis C 2008. Middle-aged human apoE4 targeted-replacement mice show retention deficits on a wide range of spatial memory tasks. Behav Brain Res 193(2), 174–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CC, Wu TH 2005. Effects of ambient ozone exposure on mail carriers' peak expiratory flow rates. Environ Health Perspect 113(6), 735–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan ES, Shetty MS, Sajikumar S, Chen C, Soong TW, Wong BS 2016. ApoE4 expression accelerates hippocampus-dependent cognitive deficits by enhancing Abeta impairment of insulin signaling in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model. Scientific reports 6, 26119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JC, Schwartz J 2009. Neurobehavioral effects of ambient air pollution on cognitive performance in US adults. Neurotoxicology 30(2), 231–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary EG, Cifuentes M, Grinstein G, Brugge D, Shea TB 2018. Association of Low-Level Ozone with Cognitive Decline in Older Adults. J Alzheimers Dis 61(1), 67–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duits FH, Kester MI, Scheffer PG, Blankenstein MA, Scheltens P, Teunissen CE, van der Flier WM 2013. Increase in cerebrospinal fluid F2-isoprostanes is related to cognitive decline in APOE epsilon4 carriers. J Alzheimers Dis 36(3), 563–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg DT, Kuzawa CW, Hayes MG 2010. Worldwide allele frequencies of the human apolipoprotein E gene: climate, local adaptations, and evolutionary history. American journal of physical anthropology 143(1), 100–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrer LA, Cupples LA, Haines JL, Hyman B, Kukull WA, Mayeux R, Myers RH, Pericak-Vance MA, Risch N, van Duijn CM 1997. Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease. A meta-analysis. APOE and Alzheimer Disease Meta Analysis Consortium. Jama 278(16), 1349–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flohe L, Gunzler WA 1984. Assay of glutathione peroxidase in: L. P (Ed.). Methods in Enzymology. Academic Press, New York, pp 114–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatto NM, Henderson VW, Hodis HN, St John JA, Lurmann F, Chen JC, Mack WJ 2014. Components of air pollution and cognitive function in middle-aged and older adults in Los Angeles. Neurotoxicology 40, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glodzik-Sobanska L, Pirraglia E, Brys M, de Santi S, Mosconi L, Rich KE, Switalski R, Saint Louis L, Sadowski MJ, Martiniuk F, Mehta P, Pratico D, Zinkowski RP, Blennow K, de Leon MJ 2009. The effects of normal aging and ApoE genotype on the levels of CSF biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging 30(5), 672–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graeser AC, Boesch-Saadatmandi C, Lippmann J, Wagner AE, Huebbe P, Storm N, Hoppner W, Wiswedel I, Gardemann A, Minihane AM, Doring F, Rimbach G 2011. Nrf2-dependent gene expression is affected by the proatherogenic apoE4 genotype-studies in targeted gene replacement mice. J Mol Med (Berl) 89(10), 1027–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henneberger PK, Olin AC, Andersson E, Hagberg S, Toren K 2005. The incidence of respiratory symptoms and diseases among pulp mill workers with peak exposures to ozone and other irritant gases. Chest 128(4), 3028–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Zimbron LF, Rivas-Arancibia S 2015. Oxidative stress caused by ozone exposure induces beta-amyloid 1-42 overproduction and mitochondrial accumulation by activating the amyloidogenic pathway. Neuroscience 304, 340–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hixson JE, Vernier DT 1990. Restriction isotyping of human apolipoprotein E by gene amplification and cleavage with HhaI. J Lipid Res 31(3), 545–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huebbe P, Dose J, Schloesser A, Campbell G, Gluer CC, Gupta Y, Ibrahim S, Minihane AM, Baines JF, Nebel A, Rimbach G 2015. Apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotype regulates body weight and fatty acid utilization-Studies in gene-targeted replacement mice. Molecular nutrition & food research 59(2), 334–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DP, Liang Y 2009. Measuring the poise of thiol/disulfide couples in vivo. Free Radic Biol Med 47(10), 1329–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung CR, Lin YT, Hwang BF 2015. Ozone, particulate matter, and newly diagnosed Alzheimer's disease: a population-based cohort study in Taiwan. J Alzheimers Dis 44(2), 573–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katre A, Ballinger C, Akhter H, Fanucchi M, Kim DK, Postlethwait E, Liu RM 2011. Increased transforming growth factor beta 1 expression mediates ozone-induced airway fibrosis in mice. Inhal Toxicol 23(8), 486–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharrazi H, Vaisi-Raygani A, Rahimi Z, Tavilani H, Aminian M, Pourmotabbed T 2008. Association between enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant defense mechanism with apolipoprotein E genotypes in Alzheimer disease. Clin Biochem 41(12), 932–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knouff C, Hinsdale ME, Mezdour H, Altenburg MK, Watanabe M, Quarfordt SH, Sullivan PM, Maeda N 1999. Apo E structure determines VLDL clearance and atherosclerosis risk in mice. J Clin Invest 103(11), 1579–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Wall SB, Ren C, Velten M, Hill CL, Locy ML, Rogers LK, Tipple TE 2016. Thioredoxin Reductase Inhibition Attenuates Neonatal Hyperoxic Lung Injury and Enhances Nuclear Factor E2-Related Factor 2 Activation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 55(3), 419–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CC, Liu CC, Kanekiyo T, Xu H, Bu G 2013. Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: risk, mechanisms and therapy. Nature reviews Neurology 9(2), 106–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu RM, van Groen T, Katre A, Cao D, Kadisha I, Ballinger C, Wang L, Carroll SL, Li L 2011. Knockout of plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 gene reduces amyloid beta peptide burden in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging 32(6), 1079–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maezawa I, Maeda N, Montine TJ, Montine KS 2006. Apolipoprotein E-specific innate immune response in astrocytes from targeted replacement mice. J Neuroinflammation 3, 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng FT, Zhao J, Fang H, Zhang LF, Wu HM, Liu YJ 2017. Upregulation of Mineralocorticoid Receptor in the Hypothalamus Associated with a High Anxiety-like Level in Apolipoprotein E4 Transgenic Mice. Behav Genet 47(4), 416–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra M, Jiang H, Wu L, Chawsheen HA, Wei Q 2015. The sulfiredoxin-peroxiredoxin (Srx-Prx) axis in cell signal transduction and cancer development. Cancer Lett 366(2), 150–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumaw CL, Levesque S, McGraw C, Robertson S, Lucas S, Stafflinger JE, Campen MJ, Hall P, Norenberg JP, Anderson T, Lund AK, McDonald JD, Ottens AK, Block ML 2016. Microglial priming through the lung-brain axis: the role of air pollution-induced circulating factors. Faseb J 30(5), 1880–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ophir G, Meilin S, Efrati M, Chapman J, Karussis D, Roses A, Michaelson DM 2003. Human apoE3 but not apoE4 rescues impaired astrocyte activation in apoE null mice. Neurobiol Dis 12(1), 56–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peris-Sampedro F, Basaure P, Reverte I, Cabre M, Domingo JL, Colomina MT 2015. Chronic exposure to chlorpyrifos triggered body weight increase and memory impairment depending on human apoE polymorphisms in a targeted replacement mouse model. Physiol Behav 144, 37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson T, Lattanzio F, Calvo-Garrido J, Rimondini R, Rubio-Rodrigo M, Sundstrom E, Maioli S, Sandebring-Matton A, Cedazo-Minguez A 2017. Apolipoprotein E4 Elicits Lysosomal Cathepsin D Release, Decreased Thioredoxin-1 Levels, and Apoptosis. J Alzheimers Dis 56(2), 601–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raber J, Wong D, Yu GQ, Buttini M, Mahley RW, Pitas RE, Mucke L 2000. Apolipoprotein E and cognitive performance. Nature 404(6776), 352–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramassamy C, Averill D, Beffert U, Theroux L, Lussier-Cacan S, Cohn JS, Christen Y, Schoofs A, Davignon J, Poirier J 2000. Oxidative insults are associated with apolipoprotein E genotype in Alzheimer's disease brain. Neurobiol Dis 7(1), 23–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh A, Varghese SS, Doraiswamy J, Malaiappan S 2014. Role of sulfiredoxin in systemic diseases influenced by oxidative stress. Redox biology 2, 1023–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren C, Williams GM, Morawska L, Mengersen K, Tong S 2008. Ozone modifies associations between temperature and cardiovascular mortality: analysis of the NMMAPS data. Occup Environ Med 65(4), 255–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedel BC, Thompson PM, Brinton RD 2016. Age, APOE and sex: Triad of risk of Alzheimer's disease. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 160, 134–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rijpma A, Jansen D, Arnoldussen IA, Fang XT, Wiesmann M, Mutsaers MP, Dederen PJ, Janssen CI, Kiliaan AJ 2013. Sex Differences in Presynaptic Density and Neurogenesis in Middle-Aged ApoE4 and ApoE Knockout Mice. Journal of neurodegenerative diseases 2013, 531326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Arancibia S, Guevara-Guzman R, Lopez-Vidal Y, Rodriguez-Martinez E, Zanardo-Gomes M, Angoa-Perez M, Raisman-Vozari R 2010. Oxidative stress caused by ozone exposure induces loss of brain repair in the hippocampus of adult rats. Toxicol Sci 113(1), 187–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh PP, Singh M, Mastana SS 2006. APOE distribution in world populations with new data from India and the UK. Annals of human biology 33(3), 279–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solas M, Milagro FI, Ramirez MJ, Martinez JA 2017. Inflammation and gut-brain axis link obesity to cognitive dysfunction: plausible pharmacological interventions. Curr Opin Pharmacol 37, 87–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sripetchwandee J, Chattipakorn N, Chattipakorn SC 2018. Links Between Obesity-Induced Brain Insulin Resistance, Brain Mitochondrial Dysfunction, and Dementia. Frontiers in endocrinology 9, 496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PM, Mace BE, Estrada JC, Schmechel DE, Alberts MJ 2008. Human apolipoprotein E4 targeted replacement mice show increased prevalence of intracerebral hemorrhage associated with vascular amyloid deposition. Journal of stroke and cerebrovascular diseases : the official journal of National Stroke Association 17(5), 303–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachibana M, Holm ML, Liu CC, Shinohara M, Aikawa T, Oue H, Yamazaki Y, Martens YA, Murray ME, Sullivan PM, Weyer K, Glerup S, Dickson DW, Bu G, Kanekiyo T 2019. APOE4-mediated amyloid-beta pathology depends on its neuronal receptor LRP1. J Clin Invest 129(3), 1272–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toda N, Ayajiki K, Okamura T 2014. Obesity-induced cerebral hypoperfusion derived from endothelial dysfunction: one of the risk factors for Alzheimer's disease. Curr Alzheimer Res 11(8), 733–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungar L, Altmann A, Greicius MD 2014. Apolipoprotein E, gender, and Alzheimer's disease: an overlooked, but potent and promising interaction. Brain imaging and behavior 8(2), 262–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villasana L, Acevedo S, Poage C, Raber J 2006. Sex- and APOE isoform-dependent effects of radiation on cognitive function. Radiat Res 166(6), 883–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villasana LE, Weber S, Akinyeke T, Raber J 2016. Genotype differences in anxiety and fear learning and memory of WT and ApoE4 mice associated with enhanced generation of hippocampal reactive oxygen species. J Neurochem 138(6), 896–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu YC, Lin YC, Yu HL, Chen JH, Chen TF, Sun Y, Wen LL, Yip PK, Chu YM, Chen YC 2015. Association between air pollutants and dementia risk in the elderly. Alzheimer's & dementia 1(2), 220–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youmans KL, Tai LM, Nwabuisi-Heath E, Jungbauer L, Kanekiyo T, Gan M, Kim J, Eimer WA, Estus S, Rebeck GW, Weeber EJ, Bu G, Yu C, Ladu MJ 2012. APOE4-specific changes in Abeta accumulation in a new transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem 287(50), 41774–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Xu J, Gao J, Chen P, Yin M, Zhao W 2019. Decreased immunoglobulin G in brain regions of elder female APOE4-TR mice accompany with Abeta accumulation. Immunity & ageing : I & A 16, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Nwabuisi-Heath E, Dumanis SB, Tai LM, Yu C, Rebeck GW, LaDu MJ 2012. APOE genotype alters glial activation and loss of synaptic markers in mice. Glia 60(4), 559–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Effect of age and O3 exposure on swimming speed and swimming distance of male apoE3 and apoE4 TR mice. A) Swimming speeds of apoE3 mice; B) Swimming speeds of apoE4 mice. The results were analyzed by 3-factor ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc analyses. *, Significantly different from the corresponding young apoE3/apoE4 mice (p<0.05, n=13-16).

Supplementary Figure 2. Effect of age and O3 exposure on anxiety levels of male apoE3 and apoE4 TR mice. A&B) Open field test results: time spent at sides (A) or in the center (B). C&D) Zero maze test results: time spent in the close area (C) or in the open area (D). The results were analyzed by 3-factor ANOVA and the p-values are from Tukey post-hoc analyses (n=13-16).