Abstract

A mutation in the Cdh23 gene is implicated in both syndromic and non-syndromic hearing loss in humans and age-related hearing loss in C57BL/6 mice. It is generally assumed that human patients (as well as mouse models) only have a hearing loss phenotype if the mutation is homozygous. However, a major complaint for patients with a hearing disability is a reduced speech intelligibility that may be related to temporal processing deficits rather than just elevated thresholds. In this study, we used the amplitude modulation following response (AMFR) to test whether mice heterozygous for Cdh23735A>G have an auditory phenotype that includes temporal processing deficits. The hearing of mice heterozygous for the Cdh23735A>G mutation was compared to age-matched mice homozygous for either the mutation or the wild-type in three cohorts of mice of both sexes at 2–3, 6 and 12 months of age. The AMFR technique was used to generate objective hearing thresholds for all mice across their range of hearing and to test their temporal processing. We found a genotype dependent hearing loss in mice homozygous for the mutation starting at 5–11 weeks of age, an age when mice on the C57BL/6 background are often presumed to have normal hearing. The heterozygous animals retained normal hearing thresholds up to one year of age. Nevertheless, the heterozygous animals showed a decline in temporal processing abilities at one year of age that was independent of their hearing thresholds. These results suggest that mice heterozygous for the Cdh23 mutation do not have truly normal hearing.

Keywords: Hearing loss, Cadherin 23, Amplitude modulation following response, Ageing, Hearing test, Temporal precision

1. Introduction

Age-related hearing loss can be devastating for affected individuals as well as their environment. It can lead to social withdrawal and depression (Rutherford et al., 2018). The prevalence of hearing loss increases with age. One gene that has been found to be involved in syndromic (Usher syndrome type 1D) and non-syndromic hearing loss (DFNB 12) as well as age-related hearing loss is Cadherin 23/Otocadherin (Cdh23) (Bork et al., 2001; Kim et al., 2016). It codes for Cadherin 23, a glycoprotein necessary for both development and maintenance of the hair bundle and tip links of the hair cells and is therefore essential for mechanotransduction (Müller, 2008). A point mutation, Ahl1 (Cdh23735A>G), has been identified to cause age-related hearing loss in several inbred mouse strains, including C57BL/6 (Johnson et al., 1997; Noben-Trauth et al., 2003). Mice homozygous for this mutation show a progressive high frequency hearing loss starting at about 3 months of age that eventually results in severe hearing loss at one year of age (Bowl and Dawson, 2015). Similar to the heterozygous carriers of the human mutations of Cdh23, mice heterozygous for this mutation are considered to be unaffected (Bork et al., 2001; Noben-Trauth et al., 2003), but this assumption may be false.

A common complaint of patients with age-related hearing loss is reduced speech intelligibility, especially in noisy environments. This phenomenon cannot be sufficiently explained by elevated hearing thresholds, but it may be related to a decline in the temporal processing abilities in those patients (Babkoff and Fostick, 2017; Fitzgibbons and Gordon-Salant, 1996; Robert Frisina and Frisina, 1997). Behavioral tests, such as the gap detection test, are usually used to assess temporal processing performance in humans (Gordon-Salant and Fitzgibbons, 1993). Unfortunately, they are very time consuming and therefore not performed during standard hearing tests. It is possible that animals heterozygous for Ahl1 also may have auditory deficits that cannot be found using standard hearing tests (e.g. hearing thresholds). The standard electrophysiological test to assess auditory function in both humans and animals is the auditory brainstem response (ABR) measurement. While this is a very well established method, it has one big disadvantage: the threshold is determined by the subjective identification of the response (François et al., 2016). So, a more objective method is necessary, one that can test threshold as well as temporal processing.

The amplitude modulation following response (AMFR) allows for both objective measurement of hearing thresholds and assessment of temporal processing abilities. AMFR, also known as the envelope following response, was first suggested as a test for frequency specific hearing thresholds by Kuwada et al (1986) and can also be used to test for temporal processing abilities. Purcell et al. (2004) reported that envelope following responses predict gap detection performance in humans. Consequently, the AMFR may provide a better way to assess changes in temporal processing with age.

Here, we used AMFR to test mice heterozygous for the Ahl1 mutation for their hearing performance including temporal processing at different ages. Their results were compared to mice carrying two alleles of the mutation or the wild-type. For this purpose, we tested transgenic mice on a C57BL/6 background expressing channelrhodopsin that had not been previously genotyped for this mutation. We also tested a second C57BL/6 background strain created to remove the Ahl1 mutation and replace it with the wild-type gene. Hearing thresholds of that strain were previously evaluated and showed a rescue of low hearing thresholds up to 18 months of age (Johnson et al., 1997). Additionally, CBA/J mice were used for comparisons at one year of age as they are reported to retain low hearing thresholds up to an old age. Our results show that the hearing thresholds of the heterozygous mice at one year of age were comparable to those of younger ages and mice homozygous for the wild-type genotype (Cdh23735G). Despite this, the heterozygous mice at one year of age had temporal processing deficits.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal model

All experiments were performed in accordance with the institutional guidelines and the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Connecticut Health Center. Animals of either sex were used. They were housed and bred in the local animal facility and every care was taken to reduce the number of animals and to refine the protocol to reduce any suffering.

Three different mouse strains were used. Breeding pairs were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Previous experiments used a mouse with a C57BL6 background in order to identify GABAergic neurons optogenetically where channelrhodopsin was expressed under the VGAT promoter (B6.Cg-Tg(Slc32a1-COP4*H134R/EYFP)8Gfng/J; Jackson Stock #14548) (Ono et al., 2017). (Abbreviated here as VGAT.) Since mice with the C57BL6 background are known to have the mutation for age-related hearing loss (Ahl1), we bred these mice with B6.CAST-Cdh23Ahl+/Kjn (Stock #002756) mice (B6.CAST), as they are reported to not have an age-related hearing loss. The result of this breeding created a hybrid of both strains (VGAT × B6.CAST). Additional CBA/J mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Stock #000656) and were used as a control group for the one-year old cohort after acclimating to the facility. Each tested animal was either ear punched or tail snipped to obtain a DNA sample.

2.2. Group design

This cross-sectional study included mice of both sexes. B6.CAST and VGAT × B6.CAST mice with different genotypes (A/A, A/G, G/G) for the Ahl point mutation (Cdh23735A>G) were compared at different ages (5–11 weeks, 24–29 weeks and 45–52 weeks). In the 1-year-old group, CBA/J mice were added as an additional aged-matched control group. In the youngest group tested, only the A/A and A/G genotypes were found in the experimental animals. The genotyping results were obtained routinely after the auditory phenotype had been assessed. The experimenter was therefore only aware of the age of the tested mouse and blinded to the genotype. The distribution of genotypes for each strain is given in Table 1.

Table 1 -.

Genotype distribution according to age and background strain

| Strain╲Genotype | A/A | A/G | G/G | total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B6.CAST | 3 | 13 | 5 | 21 |

| VGAT × B6.CAST | 15 | 6 | 0 | 21 |

| CBA/CaJ | 0 | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| Total | 18 | 19 | 11 | 48 |

This table shows that the majority of the B6.CAST mice had a A/G genotype while the VGAT × B6.CAST mice had predominately an A/A genotype and all CBA/J mice had a G/G genotype.

2.3. Anesthesia and surgical procedures

All recordings were performed on anesthetized mice (90 mg/kg ketamine, 9 mg/kg xylazine, and 2.7 mg/kg acepromazine, i.m. or i.p.) located in a sound attenuated chamber (IAC, Bronx, NY). If needed, supplemental doses of 1/2 of the initial dose were administered (i.m. or i.p.). The animals were placed on a heating pad coupled to a rectal thermometer and kept at 36–38 °C (FHC, Bowdoin, ME). Oxygen was provided via a nose cone at a flow rate of 0.5 L/min. To avoid dry corneas, artificial tear salve was applied to the eyes. Approximately every 30 min the animal received warm saline (0.3 mL s.c.). The anesthesia level was checked via the toe pinch reflex (~every 30 min) as well as through a continuous measurement of heart rate and O2 saturation levels via a pulse oximeter (MouseOx, Starr Life Science Corp, PA). Prior to the surgery, 0.03 mL lidocaine hydrochloride (1%, s.c.) was injected at the site of incision dorsal to the midbrain. A craniotomy was performed to place a recording electrode directly over the inferior colliculus (IC). After a midline incision of the skin, the skull was exposed and a small indentation was made with an electrical drill about 0.5–1 mm caudal to lambda on the right side. To avoid damage to the underlying brain tissue, the final step of the craniotomy was done with a manual drill bit matched to the stainless-steel screw (#0–80) that was placed into the craniotomy.

2.4. Electrophysiological recordings.

The screw placed above the right inferior colliculus served as the vertex recording electrode for auditory brainstem responses (ABR) and amplitude modulation following responses (AMFR). The reference and ground electrodes were needle electrodes placed retroauricularly on the contra- and ipsilateral side, respectively. A speaker (Revelator R2904/7000–05 Tweeter, ScanSpeak, Denmark) was placed 9 cm above the animal’s head. The sound system was calibrated from 122 – 46387 Hz by using a 1/4” microphone (Type 4135, Brüel & Kjaer, Naerum, Denmark) placed also at a distance of 9 cm. An RZ6 auditory processor (TDT, Tucker Davis Technology, Alachua, USA) was used for the generation of the acoustic stimuli, and a TDT RA4PA medusa preamp with TDT RA4LI low impedance headstage provided the input to the RZ6 for the signal acquisition. For the click-evoked ABR recording, 512 0.2 ms clicks with alternating polarity were delivered at a presentation rate of 21 Hz at 0–85 dB SPL in 5 dB steps using TDT BioSig software. The signal was bandpass filtered (300–3000 Hz), and the click threshold was determined to be the midpoint between the first stimulus intensity with a detectable ABR waveform and the last stimulus intensity without a detectable ABR waveform. For offline analysis, the recorded signal was filtered (500–3000 Hz) and the individual peaks were determined at all supra-threshold stimulus intensities by an experienced observer. Unclear responses were resolved by consensus with a second experienced observer. AMFR recordings were used to obtain objective frequency-specific thresholds and to evaluate the temporal processing abilities of the mice. We used a custom software written in MATLAB and TDT RPvdsEX (© Gongqiang Yu, UConn Health) based on the methods developed by Kuwada et al (1986). The acoustic stimuli were generated digitally and delivered with a sample rate of 97.7 kHz. For the recording of the evoked potentials the signals were sampled at a rate of 9.7 kHz.

To establish the audiogram, a narrowband noise carrier (0.3 octave bandwidth) was centered at 2–40 kHz and modulated by a 42.9 Hz sine wave, raise to exponent 8 (see Equation 1) where m is the modulation depth, n is the exponent (the power of the raised sine-wave dc-shift), and fm is the modulator’s frequency. We chose a modulation frequency (MF) of 42.9 Hz as this frequency was a good compromise of speed and auditory structures involved in generating the signal. Higher modulation frequencies would have sped up the process, but it would limit the number of auditory structures that were able to follow the modulation. The AMFR to a MF of 42.9 Hz include generators from the cochlea up the midbrain (Kuwada et al., 2002).

| (1) |

During the recording, the coherence (COH) between the recorded signal at the MF and the MF of the stimulus was calculated online using the “mscohere” function in MATLAB. The coherence strength (CS) was determined using Equation 2 where COH is the MSC (magnitude squared coherence) value of the bin containing the modulation frequency and Nnoise and SDnoise correspond to the mean and standard deviation, respectively, of the noise floor (bin 5–10 to the right side of the MF).

| (2) |

If the COH value was above 0.25 and the CS exceeded 3, or if COH was > 0.50 for 5 consecutive blocks, (1 block = 8 epochs, 1 epoch = 10 cycles or min 250 ms) it was considered to be a positive response to the stimulus. At least five sequential positive responses were required to “pass” at that SPL level. In that case, the intensity level was decreased by 5 dB SPL and the process was repeated until a response could no longer be obtained at that intensity level. The AMFR was considered to be absent (“fail”) if five sequential positive responses were not obtained after the presentation of 350 epochs. Depending on the thresholds obtained with the click ABR measurements and the carrier frequency to be tested we usually started our recordings at 60–90 dB SPL and then decreased the stimulus intensity by 5 dB steps. The AMFR threshold was considered to be the midpoint between the lowest stimulus intensity with a response and the highest stimulus intensity without a response.

To assess the temporal processing abilities, the carrier frequency with the lowest threshold was presented at 30 dB above threshold with varying modulation frequencies (17–544 Hz, 0.3 octave steps and randomized order). During the offline analysis, the accumulated signal (length of one block) was segmented into the length of an epoch. These epochs were then averaged together and further filtered (1 octave bandwidth at MF). From this, peak synchrony and amplitude were extracted. To extract peak synchrony (PS), the averaged epochs of the stimulus and the recorded signal were both aligned and segmented into cycles, followed by a comparison of the stimulus and the recorded signal for each cycle (using Equation 3) where N is the total number of cycles of the stimulus, θi is phase (in radian) between the peak of the evoked potentials to the peak of the stimulus at ith cycle.

| (3) |

To extract the amplitude of the response, the cycles of the recorded signal were all averaged and the maximum and minimum were determined to calculate the amplitude.

2.5. Software and code accessibility

The code for recording the AMFR was written in MATLAB and TDT RPvdsEX and require the TDT hardware cited above. The analysis code for the AMFR was written in MATLAB. Both programs are available upon request.

2.6. DNA isolation.

Genomic DNA was extracted by one of two methods. In the first, the tissue sample was incubated (ear punch or tail snip) with 100 μL 50 mM NaOH at ~95 ° C for 15 min and then spun at 13000 rpm at 4 ° C for 5 min. This reaction was stopped with 10 μL of 1 M Tris-HCl (pH 8) followed by another spin. Alternatively, the DNA was extracted from the tissue sample using 100 μL lysis buffer (12.5 μL 10N NaOH, 2.0 μL 0.5M EDTA and 5 mL H2O) at ~97 ° C for 30 min, vortexing the tube every 5 min. This reaction was stopped with 100 μL neutralization buffer (500 μL 0.5 M Tris HCl, pH 6.8 and 9.5 mL H2O) and followed by a 10 min spin at room temperature. The DNA thus extracted was further diluted 1:1 in water. All DNA samples were stored at −20 ° C.

2.7. PCR and Sequencing

For the PCR reaction we used the GoTaq Flexi DNA polymerase kit (Promega, USA). We added 0.6 μL DNA to 19 μL reaction mix, which included 0.2 μL of each primer at a concentration of 20 μM. The following primer sequences were used: GTCTCCCAAGGATCAAGACAAG (For) and CCACTGCTCTAAGGGAATCAAA (Rev). The final PCR product was purified using a column purification kit (GeneJET PCR Purification kit, Thermo Scientific, USA) and sequenced using Sanger sequencing (Genewiz LLC,South Plainfield, NJ USA) and the forward primer.

2.8. Statistics

All statistical analyses, except the post-hoc power analysis were performed using Origin (OriginLab Corperation, Northampton, MA USA). The power analysis was performed using G*Power 3.1 (Heinrich-Heine University, Düsseldorf, Germany). For the audiograms, a one-way ANOVA was performed at each individual frequency (and the click threshold). For the temporal processing analysis, a 2-way ANOVA using the factors modulation frequency and genotype was performed for each age. The amplitude growth functions for the one-year old cohort were also analyzed using a 2-way ANOVA with genotype and intensity level as the two factors. Post-hoc mean comparisons were done using the Scheffe-test. If not stated otherwise, all tests were performed on mice with a C57BL/6 background only and did not include CBA/J mice. All data not representing individual animals is plotted as mean ± SEM. Statistical results for the data shown can be found in the appendix. For statistical analysis of hearing performance, we compared mice of different genotypes within the C57BL/6 background if not stated otherwise.

3. Results

3.1. Genotyping

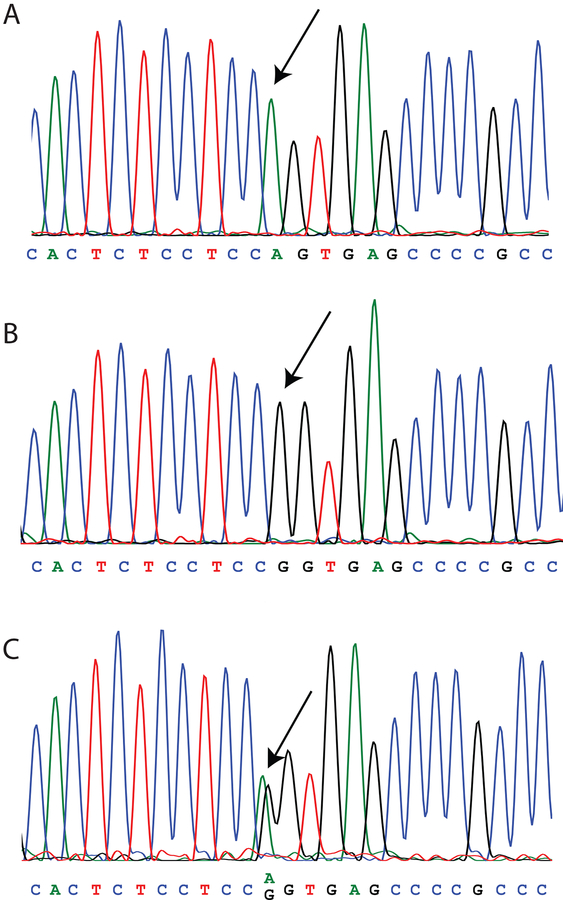

VGAT and B6.CAST mice were cross-bred to reduce the prevalence of the Ahl phenotype resulting from the Cdh23 point mutation in chromosome 10 at position 753 in the genetically modified VGAT strain. All three genotypes (A/A, A/G, G/G) were found in mice of the B6.CAST strain. A representative example of all three genotypes in the sequencing results can be found in Fig.1. By chance, only A/G and A/A were found in mice tested at the youngest age. The offspring of the cross-breeding, the VGAT × B6.CAST mice, were predominately of the A/A genotype, but some mice were A/G. Every CBA/J mouse tested had the G/G genotype. An overview of the distribution of genotypes across strains is given in Table 1. In most cases, the acoustic recordings occurred before the tissue used for genotyping was obtained, so the investigators were blind to the genotype during the recording sessions.

Figure 1. Sequencing results of three representative animals with the arrows pointing at the point of interest.

A, The trace shows a clear peak for adenine (A), indicating that the animal is homozygous for the mutation. B, This animal is homozygous for the wild-type gene as only a peak for guanine (G) can be seen. C, The presence of a peak for both adenine and guanine classifies this animal as heterozygous.

The mice were separated into three cohorts depending on their age. The young group was 5 – 11 weeks old and consisted of seven A/A and 7 A/G mice. The six-month old group (24 – 29 weeks) consisted of five A/A, eight A/G, and two G/G mice. The one-year old cohort (45 – 53 weeks) had six A/A, four A/G, and three G/G mice of a C57BL/6 background. Additionally, six G/G mice with CBA/J background were tested at this age.

3.2. Hearing Thresholds

When we compared hearing thresholds, the Cdh23 genotype was a better predictor of the audiogram than the strain. The hearing thresholds of B6.CAST and VGAT × B6.CAST at a young age (Fig. 2A, B) revealed lower thresholds for VGAT × B6.CAST mice at 16 kHz, but at other frequencies there were no differences. There was no difference in click stimulus thresholds. Comparing the same animals grouped according to their genotype instead of strain (Fig. 2C, D) revealed no differences at 16 kHz, but a significantly higher threshold at 40 kHz for the A/A genotype. This grouping reveals a clear genotype-dependent high-frequency hearing loss, which is dissimilar to the strain dependent results (please see Appendices Table A1 for statistical results). The observed strain differences at 16 kHz can be explained by the fact that the genotypes distribution in the two groups varied (see Table 1). While the click thresholds are nearly the same for both A/A and A/G mice in the young cohort, note that at 40 kHz every single A/A mouse had a higher threshold than the A/G mice (Fig. 2C). Thus, the homozygous A/A genotype reveals a high-frequency difference even at 5–11 weeks when many investigators presume that mice on a C57Bl/6 background have normal hearing. For this reason, all further data is grouped according to genotype.

Figure 2. Audiograms and click thresholds show a genotype dependent phenotype at a young age.

A, B, Young animals sorted according to strain (VGAT × B6.CAST: n=6, B6.CAST: n=7). Red open circles represent VGAT × B6.CAST mice, dark grey open squares with dotted lines represent B6.CAST mice. C, D, The same animals as in A+B are plotted according to genotype (A/A: n=7, A/G: n=6). Magenta circles and solid lines indicate A/A mice, black squares and dotted lines indicate A/G mice, green triangles and dashed lines indicate G/G mice. The left column shows individual animals, in the right column the respective groups are plotted as mean ± SEM. The dashed line at 90 dB SPL indicates the maximum stimulus intensity used in this study. In cases in which no sound elicited a response, the threshold was assigned to be 92.5 dB SPL. *: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01, #: statistical result between A/A and both A/G and G/G. ##: p <0.01, ###: p < 0.001. For the statistical results see Appendices Table A1–1.

The genotype dependent high frequency hearing loss is even more pronounced in the comparison of 6-month-old mice. Although the click thresholds were similar, the A/A mice had significantly higher thresholds at 32 and 40 kHz compared to both A/G and G/G (Fig. 3A, B). High-frequency hearing in the A/G mice remains at the same levels as seen in the younger mice and is similar to the G/G mice (for statistical results please see Appendices Tables A1–1 and A1–2).

Figure 3. Audiograms of the middle and older aged cohort reveal a clear genotype dependent hearing loss.

A, B, The 6 month old mice (A/A: n=5, A/G: n=9, G/G: n=2). C, D, One year-old cohort mice (A/A: n=4, A/G: n=4, G/G: B6.CAST: n=3, CBA/J: n=6). The left column shows individual animals, in the right column the respective groups are plotted as mean ± SEM. Maximum stimulus level 9 dB SPL. The blue open triangles represent the G/G mouse with CBA/J background the other color codes, symbols, and significance values as in Figure 2C–D. For the statistical results see Appendices Table A1–1 (1-way ANOVA) and Table A1–2 (Scheffe test).

In the one-year old cohort, the A/A mice show clear hearing deficits across most of the audiogram as well as the click threshold (Fig. 3C, D). The heterozygous mice do not differ in their hearing phenotype from the G/G animals, both mice with B6.CAST and CBA/J background. There were significantly higher thresholds for A/A mice from 4–40 kHz. The click threshold only showed a significant threshold difference at this age with again the A/A mice having the highest thresholds. For exact statistical results, please see Appendices Table A1–1 (1-way ANOVA) and Table A1–2 (Scheffe test).

3.3. Temporal processing

We analyzed the temporal processing abilities of the mice using the AMFR data at the carrier frequency that corresponded to the most sensitive part of the audiogram for each individual mouse. The modulation frequency was varied from 17 – 544 Hz (3rd octave steps) at a stimulus intensity of 30 dB above threshold. For the oldest A/A mice, a 90 dB SPL sound intensity was used since the thresholds were too high to allow a 30 dB increase in several cases (30 dB above threshold: n=2; 25 dB: n=1; 20 dB: n=1, 15 dB: n=1, one mouse was excluded as 90 dB SPL did not elicit a strong enough response to all MF to pass criteria (threshold: 82.5 dB SPL)).

A clear influence of modulation frequency on peak amplitude is present for each age group and is depicted in Fig. 4. It can be clearly seen that as the modulation frequency increases, the amplitude of the AMFR decreases. A 2-way ANOVA confirmed a significant influence of modulation frequency at all ages (see Appendices Table A2–1; for post-hoc analysis see Table A2–2). This decrease in amplitude at higher modulation frequencies is an expected result since fewer neurons in the auditory system are able to follow the higher modulation frequencies. An influence of genotype on peak amplitude was not observed in any age group (CBA/J mice excluded), and there was no interaction between modulation frequency and genotype at any age (see Appendices Table A2–1).

Figure 4. AMFR peak amplitude for different modulation frequencies at 30 dB above threshold at most sensitive carrier frequency shows a decline at high modulation frequencies.

A clear influence of modulation frequency is present for each age group. A genotype dependent difference is present only for the oldest tested group. The left column shows individual animals, in the right column the respective groups are plotted as mean ± SEM. A, B, 5 – 11 week old mice (A/A: n=7, A/G: n=6), C, D, 24 – 29 week old mice (A/A: n=5, A/G: n=9, G/G: n=2), E, F, 45 – 53 week old mice (A/A: n=5, A/G: n=4, G/G: n=3 (C57Bl/6) + 6 (CBA/J)). In this age group A/A mice were stimulated at 90dB SPL (<30 dB above threshold in 3 animals). Color codes and symbols as in Figure 2C–D. For the statistical results see Appendices Table A2–1 (2-way ANOVA) and Table A2–2 (Scheffe test for post-hoc comparison of genotypes).

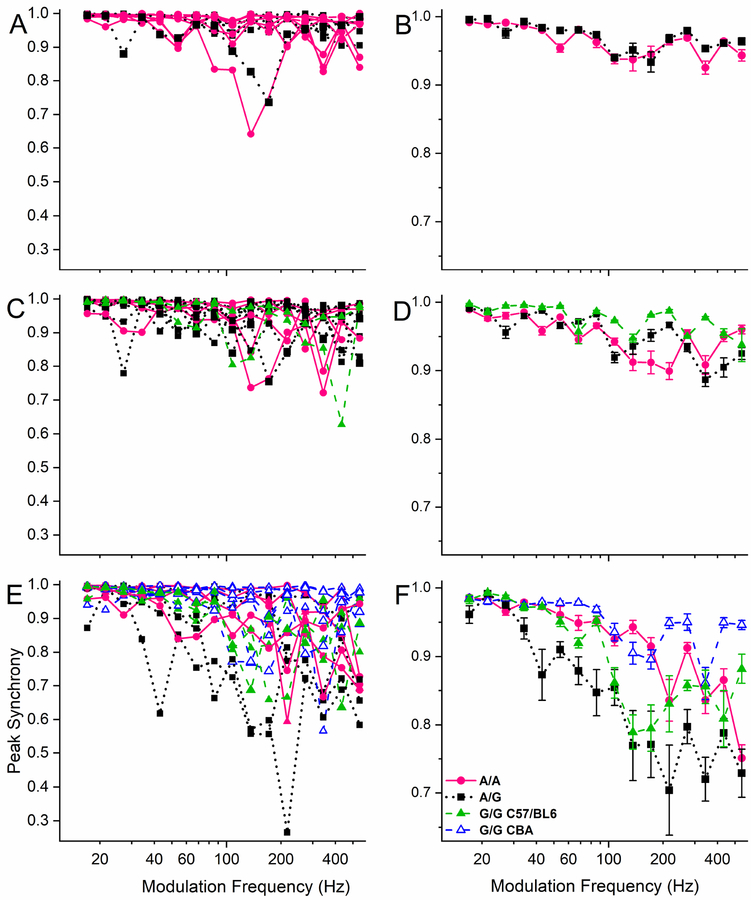

The temporal precision of the AMFR was significantly influenced by both modulation frequency and genotype. The temporal precision of the AMFR was evaluated by measuring the peak synchrony of the repeated cycles of the response (Fig. 5). Similar to the results for peak amplitude, a significant influence of modulation frequency could be detected for all tested ages, but an interaction between genotype and modulation frequency was not detected at any age (for results of a 2way-ANOVA analysis see Appendices: Table A3–1; for the post-hoc analysis see Table A3–2). Interestingly, the genotype was a major influence that was present for the 6-month and the 1-year old cohorts (Fig. 5 C–F). In the middle-aged cohort, the heterozygous animals show a slightly lower peak synchrony than the G/G mice (Fig. 5C, D). At one year of age, all three genotypes on a C57BL/6 background show a decrease in peak synchrony at higher modulation frequencies compared to CBA/J mice (Fig. 5E, F).

Figure 5. AMFR peak synchrony as a measure for temporal precision reveals deficits in the one year-old heterozygous animals.

The peak synchrony is plotted as a function of modulation frequency in the 1-year old cohort. A significant influence of genotype is seen. A strain difference between CBA/J and C57Bl/6 mice is also present for matched G/G Cdh23 genotype. A, B, 5 – 11 week old mice (A/A: n=7, A/G: n=6), C, D, 24 – 29 week old mice (A/A: n=5, A/G: n=9, G/G: n=2), E, F, 45 – 53 week old mice (A/A: n=5, A/G: n=4, G/G: n=6 (CBA/J) + 3 (B6.CAST)). In this age group A/A mice were stimulated at 90dB SPL (<30 dB above threshold in 3 animals). Color codes and symbols as in Figure 2C–D. For the statistical results see Appendices Table A3–1 (2-way ANOVA) and Table A3–2 (Scheffe test for post-hoc comparison of genotypes).

Besides the background strain difference, we also found a Cdh23 genotype-dependent influence on peak synchrony (Appendices Tables A3–1 and A3–2). Remarkably, the cohort of one-year old A/G mice with apparently “normal hearing” showed a clear deficit in temporal precision at high modulation frequencies compared to both other genotypes. This was surprising as their hearing thresholds are much better than for the age-matched A/A mice and did not differ from the G/G mice. This suggests that there are deficits in temporal processing abilities in the heterozygous mice despite their relatively normal audiograms. Altogether, this argues that the Cdh23753A>G mutation adds to another strain-dependent temporal processing difference in these mice. To establish that this effect is not due to the small sample size we performed a post-hoc power analysis and verified that the F-values indeed exceeded the critical F-value (1.29), resulting in a power of > 0.99.

To remove the influence of threshold on testing the temporal processing abilities, we stimulated each mouse at the same sensation level, e.g. 30 dB above threshold. Moreover, the hearing thresholds of the Cdh23735A/G mice were comparable both to younger genotype-matched mice as well as to the age-matched Cdh23735G/G mice. Emphasizing that this temporal processing deficit is threshold independent. The fact that the C57BL/6 Cdh23735A/A mice did not show such severe temporal deficits might be due to the fact that in those mice we were not able to always stimulate 30 dB above threshold.

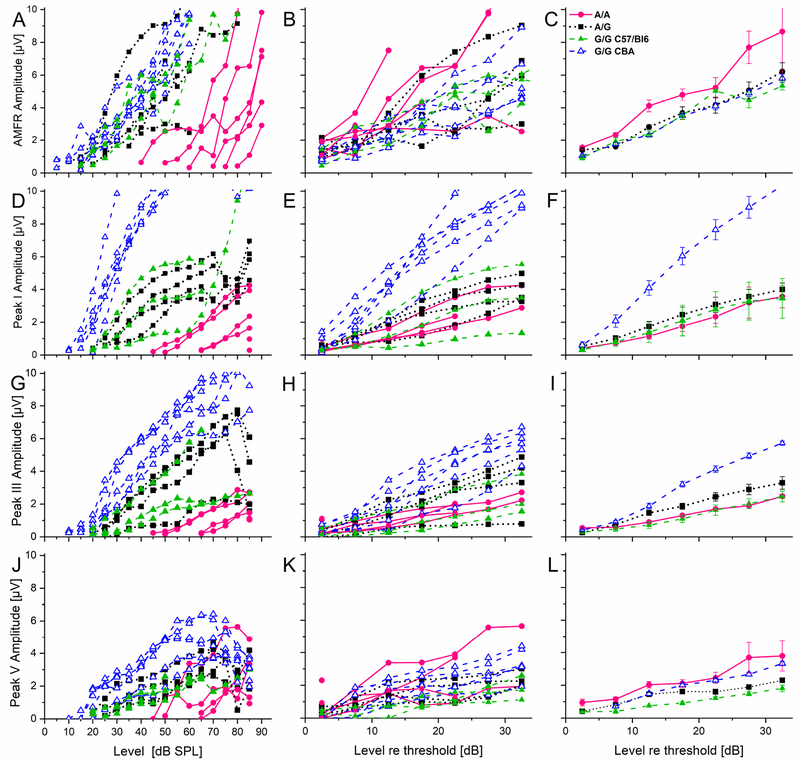

3.4. Intensity coding

It was possible that this unexpected finding in temporal processing was accompanied by a difference in intensity coding. To investigate this, we analyzed the growth function of the AMFR peak amplitude relative to increasing sound intensity in mice at one year of age. Figure 6 (A, B, C) shows plots of the AMFR amplitude growth function at the same carrier frequency used for the temporal processing. It can be clearly seen that most of the A/A mice had a much higher hearing threshold than all other mice (Fig. 6 A, D, G, J) and therefore a direct comparison of amplitude growth (slope) was easier if it was done if the amplitude growth was compared at dB above threshold (=sensation level) (Fig.6 middle and right column). This analysis, however, showed no difference between A/G and G/G mice. On the other hand, the slope of the A/A mice was steeper and reached higher amplitudes than both other genotypes, even at lower levels relative to threshold (Fig.6B, C). In the A/A group, the maximum response amplitude was reached already at 12.5 dB above threshold for one animal and at 27.5 dB above threshold for another animal (Fig. 6A). This shows that the very high hearing thresholds of the A/A mice can produce an AMFR amplitude that is as large or larger than of animals with lower thresholds but over a more limited range of intensities. This suggests a possible increase in central gain after hearing loss that could be related to hyperacusis, as (Hickox and Liberman, 2014) have shown that central gain after noise exposure can lead to increased startle responses in mice.

Figure 6. Amplitude growth functions of different auditory structures show both a genotype and strain dependent phenotype at one year of age.

Left column shows individual amplitude growth functions plotted for stimulus intensity in dB SPL. Middle column shows the growth functions as in the left column plotted for stimulus level respective to threshold (up to 35 dB above threshold). Right column shows the average group data of the corresponding plot in the middle column. B, C, The AMFR growth functions of the one year-old cohort show a significant influence of genotype with the A/A mice having the highest amplitudes. E, F, A significant strain dependent difference can be observed for ABR wave I, but no difference between the different C57Bl/6 mice. H, I, For ABR wave III again the CBA/CaJ mice showed a steeper growth curve than all other mice. K, L, For peak V the CBA/J mice show a steeper growth function than both the homozygous G/G C57Bl/6 mice and the heterozygous C57Bl/6 animals, while there was no difference to the homozygous A/A mice. Animal numbers, stimulation parameters, color codes and symbols as in Figure 5. For the statistical results see Appendices Table A4–1 (2-way ANOVA), Table A4–2 (Scheffe test for post-hoc comparison excluding CBA/J mice) and Table A4–3 (Scheffe test including CBA/J mice).

To investigate if this difference in the amplitude growth function is uniformly present at different stations of the auditory brainstem, we analyzed the amplitude growth of peaks I, III and V of the click-evoked ABR of animals at one year of age (Fig. 6D–L). The growth function for peak I, that represents cochlear activity (Fig. 6D–F), showed a significantly greater amplitude (growth) for aged CBA/J mice compared to all mice on a C57BL/6 background but no differences within the different C57BL/6 genotypes (see Appendices Tables A4–1, A4–2 and A4–3). The A/A mice did not differ in their peak I amplitude growth compared to the A/G or G/G (C57BL/6) mice (Appendices Table A4–1), even though their thresholds did differ significantly (Fig. 6D and Fig. 3). The growth curve for peak III, presumably from the superior olivary complex, showed a similar pattern as for peak I, even though the difference between the CBA/J mice and the C57BL/6 mice was reduced but still significant (see Appendices Tables A4–1 and A4–3). Comparing the different genotypes of the C57BL/6 mice revealed no significant difference between the genotypes (see Appendices Tables A4–1, A4–2 and A4–3). At peak V, a signal presumed to come from the inferior colliculus, a genotype dependent phenotype is still present, but it changed (Fig. 6J–L). Here, the A/A mice had significantly larger amplitudes compared to the G/G mice of the C57BL/6 background but not compared to the CBA/J mice. The G/G mice of the two different background strains on the other hand did differ significantly in their amplitude growth function with the C57BL/6 mice showing the shallower growth curve (see Appendices Tables A4–1, A4–2 and A4–3). These data suggest that differences in intensity coding with aging are more related to the strain of the mouse than the Cdh23753A>G genotype.

4. DISCUSSION

The present study shows that using AMFR measurements allowed us to detect a previously unknown temporal processing deficit in mice heterozygous for the Ahl1 (Cdh23735 A>G) mutation. This deficit was independent of hearing thresholds.

4.1. Sensitivity and objectivity of AMFR for threshold measurements

The AMFR technique has a greater sensitivity and objectivity than other methods to obtain audiograms. An AMFR signal obtained with a 42.9 Hz modulation frequency includes activity from the cochlea up to the inferior colliculus (IC), while the AMFR to lower modulation rates also contains signals from the thalamus and cortex (Kuwada et al., 2002). The tone pip- evoked ABR is a well-established procedure to obtain audiograms in a variety of species, but its analysis is subjective (François et al., 2016). This explains why hearing thresholds measured with the tone pip ABR often do not match those obtained with behavioral tests (Radziwon et al., 2009). The AMFR was suggested as a diagnostic test by Kuwada et al in 1986 (Kuwada et al., 1986); it is often called the envelope following response and is commercially available in advanced test equipment for clinical audiology. Several studies have shown that the AMFR method yields thresholds similar to behavioral thresholds (Aoyagi et al., 1994; Griffiths and Chambers, 1991). Our custom software for the AMFR method has the advantage of being independent of the previous experience of the experimenter, e.g. it is a truly objective test. Pre- determined criteria were used to define a positive response in the EEG to the modulation frequency where the signal was significantly above the noise floor, and had to be present 5 times without interruption.

The AMFR method may be especially useful in the assessment of temporal processing in relation to genetic abnormalities. Gap detection is the behavioral test usually performed to evaluate temporal processing abilities (Harris et al., 2010). (Williamson et al., 2015) proposed to use gap-in-noise ABR measurements instead of behavioral experiments. While this method also allows the detection of temporal processing deficits, it still has the disadvantage of all ABR recordings – the need to reliably identify the respective peaks. The AMFR on the other hand is faster than behavioral testing and more objective than ABR peak analysis and can also predict the outcome of gap detection (Purcell et al., 2004). Thus, the AMFR is highly desirable as a fast clinical screening tool for disorders of temporal processing.

4.2. Strain differences

Aging may further accentuate differences between strains of mice. At one year of age, the amplitude growth of ABR wave I in relation to sound intensity revealed differences between the mouse strains but not the Cdh23735 genotype (Fig. 6). The growth function for the Cdh23735G/G mice on the CBA background was steep, but flatter for all three Cdh23735 genotypes on the C57BL/6 background. Such difference in intensity coding at the level of the auditory nerve may be further evidence of additional loci in the C57BL/6 genome influencing the hearing phenotype as already suggested (Johnson et al., 2017). A study by (Frisina et al., 2007) reported a reduced activity of the medial olivocochlear efferent system in young adult C57 mice compared to age- matched CBA mice, indicating further strain differences in different parts of the auditory system besides the cochlea. The amplitude growth functions of the later ABR waves (click evoked) and the AMFR (42.9 Hz modulation frequency) were more similar between strains and suggests that this intensity coding deficit is, at least partially, compensated by central gain mechanisms. Such a phenomenon of central gain is also observed in other models of aging as well as models of cochlear synaptopathy (Chambers et al., 2016; Parthasarathy et al., 2019). Cochlear synaptopathy (e.g. the loss of the synapse between inner hair cell and auditory nerve fiber) is usually accompanied by a reduction in ABR peak I amplitude and an increase in the amplitude ratio of peak V to I (Sergeyenko et al., 2013). Following the loss of synaptic input, a degeneration of spiral ganglion cells (SGC) is observed. However, the age of onset and extend of this SGC loss is different between C57BL/6 mice and CBA mice (~20% at 3 month of age for C57BL/6 (Hequembourg and Liberman, 2001) and <10 % at ~3 month of age in CBA/CaJ mice (Sergeyenko et al., 2013)). It is therefore possible that the observed strain dependent differences in amplitude growth function are influenced by differences in SGC survival in the two strains.

4.3. The heterozygous Cdh23735 A>G mutation

Mice on a C57BL/6 background, among other strains, are known to have age-related hearing loss beginning at three months of age (Bowl and Dawson, 2015) and evident at 5–11 weeks in the present study (Fig. 2). This is unfortunate since the C57BL/6 strain is preferred by the NIH for transgenic experiments (2005) as well as the background strain used by the IMPC (International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium) to create their mutant mouse lines (Simon et al., 2013). The first mutation identified for age-related hearing loss in C57BL/6 mice is Ahl1, which is localized at the same position in chromosome 10 as the later identified Cdh23 gene. Cdh23 plays a crucial role during the development and maintenance of the hair-bundle and the tip-links. Nonsense mutations in Cdh23 lead to a disruption in the formation of transient lateral-links and kinociliary-links during development, resulting in a disarray of the hair-bundle and, consequently, to congenital deafness as seen in Usher 1D patients or waltzer mice (Palma et al., 2001). Missense mutations on the other hand are presumed not to interrupt development, but to affect the mature tip-links (Manji et al., 2011). The point mutation that was the focus of this study leads to an in-frame skipping of exon 7 and is suspected to lead to an increased breakage and reduced repair of the tip-links (Johnson et al., 2017). Presumably, the protein levels of CDH23 missing exon 7 are sufficient even in homozygous animals to allow normal development, but are not sufficient to maintain the tip-links during aging or noise exposure (Miyasaka et al., 2013). Our findings suggest that the phenotype of heterozygous Cdh23735A/G mice also differs from the wild-type mice. Our sensitive AMFR testing revealed that by one year of age, the heterozygous Cdh23735A/G mice showed a deficit in terms of temporal processing (see below), even though their hearing thresholds were comparable to wild-type animals.

Our results support the hypothesis that the reduced amount of wild-type Cdh23 protein in the heterozygous animals makes the tip-links more vulnerable to breakage or impairs the repair mechanisms. While the amount of intact tip-links is sufficient to retain low hearing thresholds, it is not sufficient to maintain the high level of synchrony needed to faithfully code higher modulations frequencies. Holme and Steel (Holme and Steel, 2004) also reported a phenotype corresponding to an estimated 50 % protein reduction in heterozygous waltzer mice compared to mice homozygous for the wild-type gene. Especially interesting is that this mutation (Cdh23v) was also assumed to be recessive e.g. having unaffected carriers (Miyasaka et al., 2013).

4.4. AMFR detected temporal coding deficits in mice heterozygous for Ahl1.

The present results show that the heterozygosity of Cdh23735A/G did not conserve temporal processing in aged mice. There was a decline in temporal acuity for high modulation frequencies for Cdh23735A/G mice at one year in comparison to age-matched Cdh23735G/G mice. This deficit in the heterozygous mice has not been reported previously and is in addition to any strain difference between aging C57BL/6 and CBA mice.

If the heterozygous Cdh23735A/G mice have more surviving tip links than the homozygous Cdh23735A mice, why then do they have worse temporal processing? A study by Indzhykulian et al. (Indzhykulian et al., 2013) describe the repair mechanism of broken tip-links as a two-step process in which only the second step involves CDH23 and restores the adaptation properties of the mechanotransducer channels. It might be that CDH23 missing exon 7 cannot fulfill this task to the same amount as the correctly transcribed protein. As only 50 % of the proteins are affected, only some of the tip-links might be affected and this number may increase with age. Slight differences in the structure of some tip-links might be just enough to alter the mechanics and timing of tip link movement and introduce internal noise into the system during acoustic stimulation. Internal noise is implicated in the subtle deficits in binaural processing found in human subjects with “normal” hearing (Bernstein and Trahiotis, 2018).

Decreased synchrony or increased internal noise at the level of the hair cells would result in reduced synchrony in the central auditory system (Frisina, 2001). Any change in timing in the brainstem may be more obvious after the convergence of inputs in the IC, the location of our vertex electrode. Studies of temporal processing abilities at the level of single units in the IC also report age-related changes such as higher minimum gap detection thresholds (Walton et al., 1997; Walton et al., 1998). Plasticity in response to the changed input from the cochlea and/or aging per se has been reported at the level of the cochlear nucleus and inferior colliculus (Chambers et al., 2016; Frisina and Walton, 2006; Walton et al., 2002) and might further contribute to the observed changes in the AMFRs, which include these structures as signal generators. Normally, the IC receives brief, well-timed, transient excitatory synaptic inputs from the auditory brainstem (Kopp-Scheinpflug and Forsythe, 2018; Ono and Oliver, 2014; Rubio, 2018). Such inputs would be necessary to maintain a high level of peak synchrony in the midbrain response to modulated stimuli with raised sine-envelopes and rapid rise times. Glutamatergic neurons in the IC in particular are well synchronized to the envelope of the raised sine stimulus (Ono et al., 2017). Thus, an increase in internal noise in the timing of the cochlear response to sound may result in a degraded timing signal at the level of the auditory midbrain.

4.5. Functional implications for auditory processing in carriers of mutations

Our findings suggest that even though the Ahl1/Cdh23735 A>G mutation is reported to only affect homozygous individuals (Noben-Trauth et al., 2003), heterozygous individuals have a less obvious, and therefore, overlooked phenotype. While all mutations of Cdh23 in mice have been considered to be recessive (Miyasaka et al., 2013), our findings support the notion that heterozygous “carriers” show a more subtle phenotype than the homozygous animals.

Since mutations of Cdh23 are involved in human syndromic as well as non-syndromic hearing loss, it is likely that the assumingly unaffected carriers might also have auditory deficits. In homozygous individuals, the overall hearing loss may mask additional auditory processing deficits. We postulate that the AMFR method is a powerful tool for the assessment of auditory function in the heterozygous population.

Deficits in temporal processing will cause poor speech recognition (He et al., 2009; Snell et al., 2002; Zeng et al., 1999). Decreased speech intelligibility, especially in noisy environments, is a common phenomenon seen even in older considered “normal hearing” listeners (Füllgrabe et al., 2015; Snell et al., 2002). While different stations of the auditory system as well as other factors such as cognitive decline might contribute to this phenomenon (Harris et al., 2010; Kujawa and Liberman, 2009; Xie and Manis, 2017), the very first step in this process is the mechanotransduction in the cochlear hair cells. Studying the subtle changes in heterozygous animal models might shed light on both the physiological and pathophysiological states of this key process in the auditory system.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Amplitude modulation following response can identify differences in auditory temporal processing that standard hearing tests cannot.

Mice heterozygous for Ahl1 show a temporal processing deficit at one year of age.

This age-related temporal processing deficit is independent of hearing threshold.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

This work was supported by grants HHS | NIH | National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD) - R21-DC013822 [DLO, ALB] and DOD | United States Army | MEDCOM | Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs (CDMRP) - W81XWH-18-1-0135 [DLO, ALB] and the UConn Health Research Program [NPM]. We want to thank Professor Shigeyuki Kuwada for creating the AMFR method and his helpful comments and his teaching of the AMFR method. We also want to thank Dr. Gongqiang Yu for writing the AMFR program for us.

Abbreviations

- Cdh23

Cadherin 23 gene

- AMFR

Amplitude modulation following response

- Ahl1

age-related hearing loss gene 1

- VGAT

the mouse strain B6.Cg-Tg(Slc32a1-COP4*H134R/EYFP)8Gfng/J; Jackson Stock #14548

- B6.CAST

the mouse strain B6.CAST-Cdh23Ahl+/Kjn (Stock #002756

- VGAT × B6.CAST

the strain created by crossbreeding VGAT and B6.CAST mice

- ABR

auditory brainstem response

- MF

modulation frequency

- COH

coherence

- CS

coherence strength

- PS

peak synchrony

Table A1–1:

1-way ANOVA – Audiogram young mice

| Stimulus | Click | 2 kHz | 4 kHz | 8 kHz | 12 kHz | 16 kHz | 24 kHz | 32 kHz | 40 kHz | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 – 11 | strain | F1,11 = 0.56 P: 0.4710 |

F1,11 = 0.92 P: 0.3574 |

F1,11 = 1.05 P: 0.3285 |

F1,11 = 0.56 P: 0.4683 |

FU1 = 0.28 P: 0.6090 |

F1,11 = 6.62 P: 0.0259 |

F1,11 = 0.14 P: 0.7111 |

F1,11 = 0.24 P: 0.6369 |

F1,11 = 0.002 P: 0.9695 |

| weeks | genotype | F1,11 = 0.11 P: 0.7511 |

F1,11 = 0.92 P: 0.3574 |

F1,11 = 0.09 P: 0.7740 |

F1,11 = 0.16 P: 0.6966 |

F1,11 = 1.93 P: 0.19183 |

F1,11 = 0.22 P: 0.6511 |

F1,11 = 2.29 P: 0.1587 |

F1,11 = 3.54 P: 0.0866 |

F1,11 = 10.66 P: 0.0075 |

| 24 – 29 weeks | genotype | F2,13 = 0.15, p= 0.8656 |

F2,13 = 0.13, p= 0.8753 |

F2,13 = 0.26, p= 0.7785 |

F2,13 = 0.40, p= 0.6772 |

F2,13 = 0.09, p= 0.9122 |

F2,13 = 0.35, p= 0.7132 |

F2,13 = 2.49, p= 0.1212 |

F2,13 = 21.26, p= 0.0000797095 |

F2,13 = 21.21, p= 0.0000806224 |

| 45 – 53 weeks | genotype | F2,10 = 27.19, p= 0.0000903735 |

F2,10 = 3.24, p= 0.08243 |

F2,10 = 5.09, p= 0.02982 |

F2,10 = 15.50, p= 0.000863841 |

F2,10 = 30.44, p= 0.0000559285 |

F2,10 = 75.78, p= 0.000000908733 |

F2,10 = 39.16, p= 0.0000186061 |

F2,10 = 96.82, p= 0.000000285621 |

F2,10 = 99.79, p= 0.000000247344 |

Table A1–2:

Scheffe test – Audiogram 24–29 & 45–53 week old mice

| 24 – 29 weeks | 45 – 53 weeks | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| stimulus | genotype | A/A | A/G | A/A | A/G |

| Click | A/G | n/a | - | 0.000373502 | - |

| G/G | n/a | n/a | 0.000499574 | 0.95839 | |

| 2 kHz | A/G | n/a | - | n/a | - |

| G/G | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |

| 4 kHz | A/G | n/a | - | 0.03079 | - |

| G/G | n/a | n/a | 0.36626 | 0.45822 | |

| 8 kHz | A/G | n/a | - | 0.00171 | - |

| G/G | n/a | n/a | 0.00863 | 0.83729 | |

| 12 kHz | A/G | n/a | - | 0.000371364 | - |

| G/G | n/a | n/a | 0.000209041 | 0.66286 | |

| 16 kHz | A/G | n/a | - | 0.00000332111 | - |

| G/G | n/a | n/a | 0.0000092946 | 0.98114 | |

| 24 kHz | A/G | n/a | - | 0.0000542069 | - |

| G/G | n/a | n/a | 0.000201104 | 0.9176 | |

| 32 kHz | A/G | 0.00016708 | - | 0.00000112765 | - |

| G/G | 0.00132 | 0.71872 | 0.00000281276 | 0.99733 | |

| 40 kHz | A/G | 0.000270745 | - | 0.000000980476 | - |

| G/G | 0.000628417 | 0.35219 | 0.00000244054 | 0.99757 | |

Table A2–1:

2-way ANOVA – Peak Amplitude

| Stimulus | Genotype | Modulation Frequency |

Interaction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 −11 weeks | genotype | F1,177 = 0.30 P: 0.58553 |

F15,177 = 34.58 P: 0 |

F15,177 = 0.24 P: 0.99846 |

| 24 – 29 weeks | genotype | F2,238 = 2.63, p= 0.0741 |

F15,238 = 25.82, p= 0 |

F30,238 = 0.36, p= 0.99921 |

| 45 – 53 weeks | Only C57BL6 | F2,144 = 1.32, p= 0.27041 |

F15,144 = 15.05, p= 0 |

F30,144 = 0.18, p= 1 |

| Including CBA/J |

F3,224 = 2.70, p= 0.04647 |

F15,224 = 30.96, p= 0 |

F45,224 = 0.25, P= 1 |

Table A2–2:

Scheffe test including CBA/J mice – Peak Amplitude

| 5 – 11 weeks | 24 – 29 weeks | 45 – 53 weeks | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | genotype | A/A | A/A | A/G | A/A | A/G | G/G (C57BL/6) |

| Peak Amplitude | A/G | n/a | 0.03622 | - | 0.29437 | - | - |

| G/G (C57BL/6) | - | 0.14034 | 0.94461 | 0.94736 | 0.74024 | - | |

| G/G CBA/J | - | - | 0.87869 | 0.05475 | 0.62371 | ||

Table A3–1:

2-way ANOVA – Peak Synchrony

| Background strain |

Genotype | Modulation Frequency | Interaction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 −11 weeks | Only C57BL6 | F1,177 = 2.07 P: 0.15173 |

F15,177 = 1.97 P: 0.02006 |

F15,177 = 0.49 P: 0.94532 |

| 24 – 29 weeks | Only C57BL6 | F2,238 = 3.72, p= 0.02556 |

F15,13 = 1.86, p= 0.0285 |

F2,13 = 0.59, p= 0.95764 |

| 45 – 53 weeks | Only C57BL6 | F2,144 = 9.53, p= 0.00012976 |

F15,144 = 5.32, p= 0.000000020555 |

F30,144 = 0.56, p= 0.96786 |

| Including CBA/J |

F3,224 = 17.28, p= 0.000000000396295 |

F15,224 = 7.23, p= 0.000000000000675793 |

F45,224 = 0.89, p= 0.67197 |

Table A3–2:

Scheffe test including CBA/J mice – Peak Synchrony

| 5 – 11 weeks | 24 – 29 weeks | 45 – 53 weeks | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | genotype | A/A | A/A | A/G | A/A | A/G | G/G (C57BL/6) |

| Peak Synchrony | A/G | n/a | 0.79337 | - | 0.0000483811 | - | - |

| G/G (C57BL/6) | - | 0.12337 | 0.02574 | 0.70576 | 0.02107 | - | |

| G/G CBA/J | - | - | 0.20166 | 0.000000000744168 | 0.02607 | ||

Table A4–1:

2-way ANOVA – Amplitude Growth

| Stimulus | Genotype | Level regarding threshold | Interaction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak I | Only C57BL6 | F2,54 = 1.57 P: 0.2177 |

F6,54 = 16.76 P: 0.0000000000832874 |

F12,54 = 0.08 P: 0.99998 |

| Including CBA/J |

F3,89 = 93.43 P: 0 |

F6,89 = 41.07 P: 0 |

F18,89 = 5.96 P: 0.00000000387043 |

|

| Peak III | Only C57BL6 | F2,51 = 2.67 P: 0.0791 |

F6,51 = 11.87 P: 0.0000000272195 |

F12,51 = 0.34 P: 0.97687 |

| Including CBA/J |

F3,89 = 9.26 P: 0.0000215479 |

F6,89 = 14.10 P: 0.0000215479 |

F18,89 = 0.90 P: 0.58006 |

|

| Peak V | Only C57BL6 | F2,47 = 10.96 P: 0.000123837 |

F6,47 = 5.77, p= 0.000146874 |

F12,47 = 0.38, p= 0.96504 |

| Including CBA/J |

F3,74 = 7.29 P: 0.000238592 |

F6,74 = 7.77 P: 0.0000016857 |

F18,74 = 0.44 P: 0.97508 |

|

| AMFR | Only C57BL6 | F2,57 = 4.52 P: 0.0151 |

F6,57 = 10.53 P: 0.0000000770325 |

F12,57 = 3.64 P: 0.0000672204 |

| Including CBA/J |

F3,92 = 5.27 P: 0.00213 |

F6,92 = 19.84 P: 0.00000000000000965894 |

F18,92 = 0.40 P: 0.98525 |

Table A4–2:

Scheffe test excluding CBA/J mice – Amplitude Growth

| Genotype | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | genotype | A/A | A/G |

| Peak I | A/G | n/a | |

| G/G (C57Bl/6) | |||

| Peak III | A/G | n/a | |

| G/G (C57Bl/6) | |||

| Peak V | A/G | 0.0714 | - |

| G/G (C57Bl/6) | 0.00378 | 0.3496 | |

| AMFR | A/G | 0.57589 | - |

| G/G (C57Bl/6) | 0.42366 | 0.94331 | |

Table A4–3:

Scheffe test including CBA/J mice – Amplitude Growth

| Genotype | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | genotype | A/A | A/G | G/G (C57BL/6) |

| Peak I | A/G | 0.0766 | - | - |

| G/G (C57BL/6) | 0.54288 | 0.79237 | - | |

| G/G CBA/J | 0.00000000000000000000000257525 | 0.000000000000000000258666 | 0.000000000000000000235836 | |

| Peak III | A/G | 0.17134 | - | - |

| G/G (C57BL/6) | 0.866 | 0.77126 | - | |

| G/G CBA/J | 0.00000322792 | 0.01624 | 0.00381 | |

| Peak V | A/G | 0.11034 | - | - |

| G/G (C57BL/6) | 0.00391 | 0.425 | - | |

| G/G CBA/J | 0.99061 | 0.02971 | 0.000676471 | |

| AMFR | A/G | 0.68244 | - | - |

| G/G (C57BL/6) | 0.50579 | 0.98402 | - | |

| G/G CBA/J | 0.32494 | 0.96458 | 0.99997 | |

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Literature Cited

- 2005. NIH Planning Meeting for a Knockout Mouse Project. https://www.genome.gov/15014549/nih-planning-meeting-for-knockout-mouse-project. (Accessed 9/7/2018 2018).

- Aoyagi M, Kiren T, Furuse H, Fuse T, Suzuki Y, Yokota M, Koike Y, 1994. Pure-tone threshold prediction by 80-hz amplitude-modulation following response. Acta Oto-Laryngologica 114(S511), 7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babkoff H, Fostick L, 2017. Age-related changes in auditory processing and speech perception: cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. European Journal of Ageing 14(3), 269–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein LR, Trahiotis C, 2018. Effects of interaural delay, center frequency, and no more than “slight” hearing loss on precision of binaural processing: Empirical data and quantitative modeling. J Acoust Soc Am 144(1), 292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bork JM, Peters LM, Riazuddin S, Bernstein SL, Ahmed ZM, Ness SL, Polomeno R, Ramesh A, Schloss M, Srisailpathy CR, Wayne S, Bellman S, Desmukh D, Ahmed Z, Khan SN, Kaloustian VM, Li XC, Lalwani A, Riazuddin S, Bitner-Glindzicz M, Nance WE, Liu XZ, Wistow G, Smith RJ, Griffith AJ, Wilcox ER, Friedman TB, Morell RJ, 2001. Usher syndrome 1D and nonsyndromic autosomal recessive deafness DFNB12 are caused by allelic mutations of the novel cadherin-like gene CDH23. Am J Hum Genet 68(1), 26–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowl MR, Dawson SJ, 2015. The mouse as a model for age-related hearing loss - a mini-review. Gerontology 61(2), 149–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers AR, Resnik J, Yuan Y, Whitton JP, Edge AS, Liberman MC, Polley DB, 2016. Central Gain Restores Auditory Processing following Near-Complete Cochlear Denervation. Neuron 89(4), 867–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgibbons PJ, Gordon-Salant S, 1996. Auditory temporal processing in elderly listeners. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 7(3), 183–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- François M, Dehan E, Carlevan M, Dumont H, 2016. Use of auditory steady-state responses in children and comparison with other electrophysiological and behavioral tests. European Annals of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Diseases 133(5), 331–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisina RD, 2001. Subcortical neural coding mechanisms for auditory temporal processing. Hearing Research 158(1–2), 1–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisina RD, Newman SR, Zhu X, 2007. Auditory efferent activation in CBA mice exceeds that of C57s for varying levels of noise. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 121(1), EL29–EL34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisina RD, Walton JP, 2006. Age-related structural and functional changes in the cochlear nucleus. Hearing Research 216–217(1–2), 216–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Füllgrabe C, Moore BCJ, Stone MA, 2015. Age-group differences in speech identification despite matched audiometrically normal hearing: Contributions from auditory temporal processing and cognition. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 7(JAN). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon-Salant S, Fitzgibbons PJ, 1993. Temporal factors and speech recognition performance in young and elderly listeners. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research 36(6), 1276–1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths SK, Chambers RD, 1991. The amplitude modulation-following response as an audiometric tool. Ear and Hearing 12(4), 235–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KC, Eckert MA, Ahlstrom JB, Dubno JR, 2010. Age-related differences in gap detection: Effects of task difficulty and cognitive ability. Hearing Research 264(1), 21–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He NJ, Mills JH, Ahlstrom JB, Dubno JR, 2009. Age-related differences in the temporal modulation transfer function with pure-tone carriers. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 124(6), 3841–3849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hequembourg S, Liberman MC, 2001. Spiral ligament pathology: A major aspect of age-related cochlear degeneration in C57BL/6 mice. JARO - Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology 2(2), 118–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickox AE, Liberman MC, 2014. Is noise-induced cochlear neuropathy key to the generation of hyperacusis or tinnitus? Journal of Neurophysiology 111(3), 552–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holme RH, Steel KP, 2004. Progressive Hearing Loss and Increased Susceptibility to Noise-Induced Hearing Loss in Mice Carrying a Cdh23 but not a Myo7a Mutation. JARO - Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology 5(1), 66–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indzhykulian AA, Stepanyan R, Nelina A, Spinelli KJ, Ahmed ZM, Belyantseva IA, Friedman TB, Barr-Gillespie PG, Frolenkov GI, 2013. Molecular Remodeling of Tip Links Underlies Mechanosensory Regeneration in Auditory Hair Cells. PLoS Biology 11(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KR, Erway LC, Cook SA, Willott JF, Zheng QY, 1997. A major gene affecting age-related hearing loss in C57BL/6J mice. Hearing Research 114(1–2), 83–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KR, Tian C, Gagnon LH, Jiang H, Ding D, Salvi R, 2017. Effects of Cdh23 single nucleotide substitutions on age-related hearing loss in C57BL/6 and 129S1/Sv mice and comparisons with congenic strains. Sci Rep 7, 44450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim BJ, Kim AR, Lee C, Kim SY, Kim NKD, Chang MY, Rhee J, Park MH, Koo SK, Kim MY, Han JH, Oh SH, Park WY, Choi BY, 2016. Discovery of CDH23 as a Significant Contributor to Progressive Postlingual Sensorineural Hearing Loss in Koreans. PLoS ONE 11(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp-Scheinpflug C, Forsythe ID, 2018. Integration of Synaptic and Intrinsic Conductances Shapes Microcircuits in the Superior Olivary Complex, in: Oliver DL, Cant NB, Fay RR, Popper AN (Eds.), The Mammalian Auditory Pathways: Synaptic Organization and Microcircuits. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp. 101–126. [Google Scholar]

- Kujawa SG, Liberman MC, 2009. Adding insult to injury: Cochlear nerve degeneration after “temporary” noise-induced hearing loss. Journal of Neuroscience 29(45), 14077–14085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwada S, Anderson JS, Batra R, Fitzpatrick DC, Teissier N, D’Angelo WR, 2002. Sources of the scalp-recorded amplitude-modulation following response. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 13(4), 188–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwada S, Batra R, Maher VL, 1986. Scalp potentials of normal and hearing-impaired subjects in response to sinusoidally amplitude-modulated tones. Hearing Research 21(2), 179–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manji SS, Miller KA, Williams LH, Andreasen L, Siboe M, Rose E, Bahlo M, Kuiper M, Dahl HH, 2011. An ENU-induced mutation of Cdh23 causes congenital hearing loss, but no vestibular dysfunction, in mice. Am J Pathol 179(2), 903–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyasaka Y, Suzuki S, Ohshiba Y, Watanabe K, Sagara Y, Yasuda SP, Matsuoka K, Shitara H, Yonekawa H, Kominami R, Kikkawa Y, 2013. Compound Heterozygosity of the Functionally Null Cdh23(v-ngt) and Hypomorphic Cdh23(ahl) Alleles Leads to Early-onset Progressive Hearing Loss in Mice. Experimental Animals 62(4), 333–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller U, 2008. Cadherins and mechanotransduction by hair cells. Current Opinion in Cell Biology 20(5), 557–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noben-Trauth K, Zheng QY, Johnson KR, 2003. Association of cadherin 23 with polygenic inheritance and genetic modification of sensorineural hearing loss. Nat Genet 35(1), 21–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M, Bishop DC, Oliver DL, 2017. Identified GABAergic and Glutamatergic Neurons in the Mouse Inferior Colliculus Share Similar Response Properties. J Neurosci 37(37), 8952–8964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M, Oliver DL, 2014. Asymmetric Temporal Interactions of Sound-Evoked Excitatory and Inhibitory Inputs in the Mouse Auditory Midbrain. The Journal of Physiology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palma FD, Holme RH, Bryda EC, Belyantseva IA, Pellegrino R, Kachar B, Steel KP, Noben-Trauth K, 2001. Mutations in Cdh23, encoding a new type of cadherin, cause stereocilia disorganization in waltzer, the mouse model for Usher syndrome type 1D. Nature Genetics 27(1), 103–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parthasarathy A, Herrmann B, Bartlett EL, 2019. Aging alters envelope representations of speech- like sounds in the inferior colliculus. Neurobiology of Aging 73, 30–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell DW, John SM, Schneider BA, Picton TW, 2004. Human temporal auditory acuity as assessed by envelope following responses. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 116(6), 3581–3593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radziwon KE, June KM, Stolzberg DJ, Xu-Friedman MA, Salvi RJ, Dent ML, 2009. Behaviorally measured audiograms and gap detection thresholds in CBA/CaJ mice. Journal of Comparative Physiology A: Neuroethology, Sensory, Neural, and Behavioral Physiology 195(10), 961–969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert Frisina D, Frisina RD, 1997. Speech recognition in noise and presbycusis: Relations to possible neural mechanisms. Hearing Research 106(1–2), 95–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio ME, 2018. Microcircuits of the Ventral Cochlear Nucleus, in: Oliver DL, Cant NB, Fay RR, Popper AN (Eds.), The Mammalian Auditory Pathways: Synaptic Organization and Microcircuits. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp. 41–71. [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford BR, Brewster K, Golub JS, Kim AH, Roose SP, 2018. Sensation and psychiatry: Linking age-related hearing loss to late-life depression and cognitive decline. American Journal of Psychiatry 175(3), 215–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sergeyenko Y, Lall K, Charles Liberman M, Kujawa SG, 2013. Age-related cochlear synaptopathy: An early-onset contributor to auditory functional decline. Journal of Neuroscience 33(34), 13686–13694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon MM, Greenaway S, White JK, Fuchs H, Gailus-Durner V, Wells S, Sorg T, Wong K, Bedu E, Cartwright EJ, Dacquin R, Djebali S, Estabel J, Graw J, Ingham NJ, Jackson IJ, Lengeling A, Mandillo S, Marve J, Meziane H, Preitner F, Puk O, Roux M, Adams DJ, Atkins S, Ayadi A, Becker L, Blake A, Brooker D, Cater H, Champy MF, Combe R, Danecek P, Di Fenza A, Gates H, Gerdin AK, Golini E, Hancock JM, Hans W, Hölter SM, Hough T, Jurdic P, Keane TM, Morgan H, Müller W, Neff F, Nicholson G, Pasche B, Roberson LA, Rozman J, Sanderson M, Santos L, Selloum M, Shannon C, Southwel A, Tocchini-Valentini GP, Vancollie VE, Westerberg H, Wurst W, Zi M, Yalcin B, Ramirez-Solis R, Steel KP, Mallon AM, De Angelis MH, Herault Y, Brown SDM, 2013. A comparative phenotypic and genomic analysis of C57BL/6J and C57BL/6N mouse strains. Genome Biology 14(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snell KB, Mapes FM, Hickman ED, Frisina DR, 2002. Word recognition in competing babble and the effects of age, temporal processing, and absolute sensitivity. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 112(2), 720–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton JP, Frisina RD, Ison JR, O’Neill WE, 1997. Neural correlates of behavioral gap detection in the inferior colliculus of the young CBA mouse. Journal of Comparative Physiology - A Sensory, Neural, and Behavioral Physiology 181(2), 161–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton JP, Frisina RD, O’Neill WE, 1998. Age-Related Alteration in Processing of Temporal Sound Features in the Auditory Midbrain of the CBA Mouse. The Journal of Neuroscience 18(7), 2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton JP, Simon H, Frisina RD, Giraudet P, 2002. Age-related alterations in the neural coding of envelope periodicities. Journal of Neurophysiology 88(2), 565–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson TT, Zhu X, Walton JP, Frisina RD, 2015. Auditory brainstem gap responses start to decline in mice in middle age: a novel physiological biomarker for age-related hearing loss. Cell and Tissue Research 361(1), 359–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie R, Manis PB, 2017. Synaptic transmission at the endbulb of Held deteriorates during age-related hearing loss. Journal of Physiology 595(3), 919–934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng F-G, Oba S, Garde S, Sininger Y, Starr A, 1999. Temporal and speech processing deficits in auditory neuropathy. NeuroReport 10(16), 3429–3435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.