Abstract

The Wnt signaling pathway is involved in tumorigenesis and various stages of tumor progression, including the epithelial-mesenchymal transition, metastasis, and drug resistance. Many efforts have been made to develop drugs targeting this pathway. CGX1321 is a porcupine inhibitor that can effectively block Wnt ligand synthesis and is currently undergoing clinical trials. However, drugs targeting the Wnt pathway may frequently cause adverse events in normal tissues, such as the intestine and skin. Formulation of the drug inside liposomes could enable preferential drug delivery to solid tumor tissues and limit drug exposure in normal organs. We developed a strategy to stably encapsulate CGX1321 inside liposomes with minimal drug releases in circulation. The liposomal drugs were shown to interfere with the aberrant Wnt signaling specifically in tumor tissues, resulting in focused effects on LGR5+ CSCs (cancer stem cells), while sparing other cells from significant cytotoxicity. We showed it is feasible to use such a CSC elimination approach to treat malignant cancers prone to rapid progression using a LoVo tumor model as well as a GA007 patient derived xenograft (PDX) model. Nano drug delivery systems may be required for precision medicine in cancer therapy.

Keywords: drug delivery, liposome, Wnt inhibitor, CGX1321, cancer stem cell, tumor growth inhibition

A liposomal drug delivery system enhances efficacy of Wnt inhibitor and reduces its undesirable side effects by changing the drug’s distribution and pharmacokinetics. In addition, liposome-encapsulated Wnt inhibitor results in focused effects on cancer stem cells, such as CSC differentiation and apoptosis.

Introduction

Wnt signaling plays an important role in development and disease.1 The overactive canonical Wnt signaling pathway has been implicated in many malignant cancers, including breast, liver, colon, lung, and gastric cancers.2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Signaling begins when a Wnt protein binds to a Frizzled receptor, a G-protein-coupled receptors, and its co-receptor LRP5/6.7 Then β-catenin accumulates in the cytoplasm and eventually is translocated to the nucleus to activate transcription factor/lymphoid enhancer-binding factor (TCF/LEF) transcription that regulates the expression of a large list of target genes. Studies show that some cancers may result from over-activation of the Wnt-dependent pathway, while others may be caused by Wnt-independent non-canonical Wnt signaling.8, 9 Certain types of tumor progression activation is achieved through overexpression of canonical Wnt pathway ligands10, 11, 12, 13 or reduced expression of its negative regulatory factors.14

Due to its importance in cancer tumorigenesis, the Wnt pathway is a frequent drug target for cancer therapy. A number of Wnt pathway inhibitors are currently being developed as cancer therapies to prevent over-activation of canonical Wnt pathway. Their mechanisms of action include blocking Frizzled and LGR5/6 receptor binding through inhibiting enzymes such as tankyrases or inhibiting porcupine, which is related to Wnt secreation.15, 16, 17, 18, 19 One of the inhibitors is CGX1321, a small molecule inhibitor of Wnt secretion. CGX1321 is a porcupine inhibitor that affects Wnt production and can block Wnt downstream signaling. Thus, CGX1321 only targets to patients with an active canonical Wnt pathway in their tumor. Currently, CGX1321 is being tested in clinical trials for oral formulation on colon cancer patients.

However, because the Wnt pathway also plays an important role in maintaining stem cell pluripotency and lineage specification in normal intestine or skin,20 modifying the Wnt pathway for cancer therapy is suspected to have negative side effects.21 Here, we hypothesized that a liposome delivery system for CGX1321 can inhibit the Wnt pathway in tumor cells and avoid disruption of function in non-cancerous cells. Liposome encapsulates drugs within phospholipid vesicles. When the nanoparticles size is at around 100 nm, they display good retention in the tumor because of the EPR effect (enhanced permeability and retention),22 making them appropriate for cancer treatment.

To treat canonical Wnt-pathway-positive tumors and to avoid side effects to normal organs such as intestine, we utilized a liposome delivery. We tested CGX1321 Wnt inhibition in two different mouse models: a colon cancer cell line (LoVo) xenograft and a much more heterogeneous patient-derived gastric tumor xenograft (GA007). We found that the liposomal drug exerted its effects by interfering with Wnt signaling and resulted in LGR5+ cancer stem cell (CSC) differentiation and apoptosis. Such a targeted effect could be valuable in complementing other treatment mechanisms in effective treatment of cancers while reducing undesirable side effects.

Results

CGX1321 Blocked Wnt Signaling Pathway In Vitro

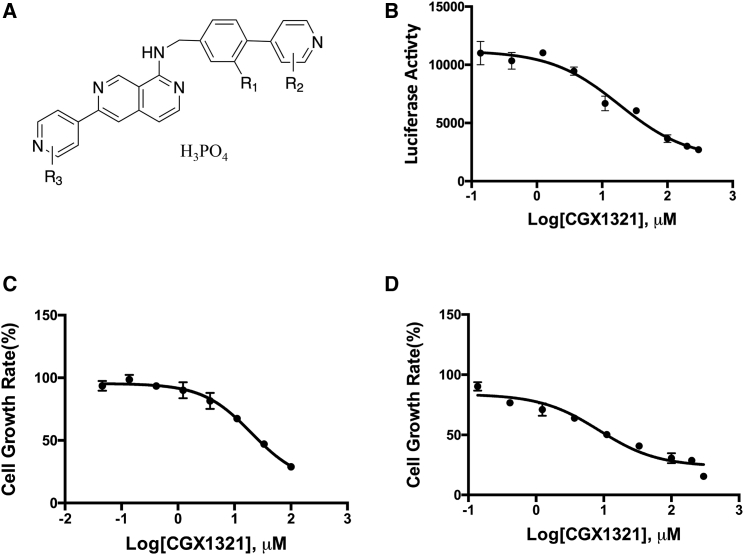

The Wnt inhibitor CGX1321 (Figure 1A) was developed and provided by Curegenix. It is a highly specific and potent porcupine inhibitor that affects Wnt expression (patent, WO2014165232A1). Its inhibitory effects on canonical Wnt signaling were shown using a HEK239-TCF luciferase reporter cell line, as shown in Figure 1B, with an estimated half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 18.4 μM. This inhibition could be reversed by addition of Wnt ligand 3a or RSPO2 in to the culture medium (Figure S1). The Wnt signaling inhibition effects result in cell growth inhibition in both HEK293-TCF cells (Figure 1C) as well as the human colorectal cancer LoVo cells (Figure 1D). LoVo cells had been shown previously to have high Wnt pathway signaling activity and high expression of the Wnt pathway co-receptor LGR5.23

Figure 1.

CGX1321 Inhibit WNT Signaling Activities and Wnt Active Cell Proliferation

(A) The structure of CGX1321. (B) CGX1321 inhibits Wnt signaling reporter assay with an IC50 of 18.4 μM. (C) CGX1321 inhibits HEK293 cell growth in vitro. (D) CGX1321 inhibits LoVo cell growth in vitro.

Liposome Formulation Improved CGX1321 Pharmacokinetics and Bio-Distribution in Tumor Tissues

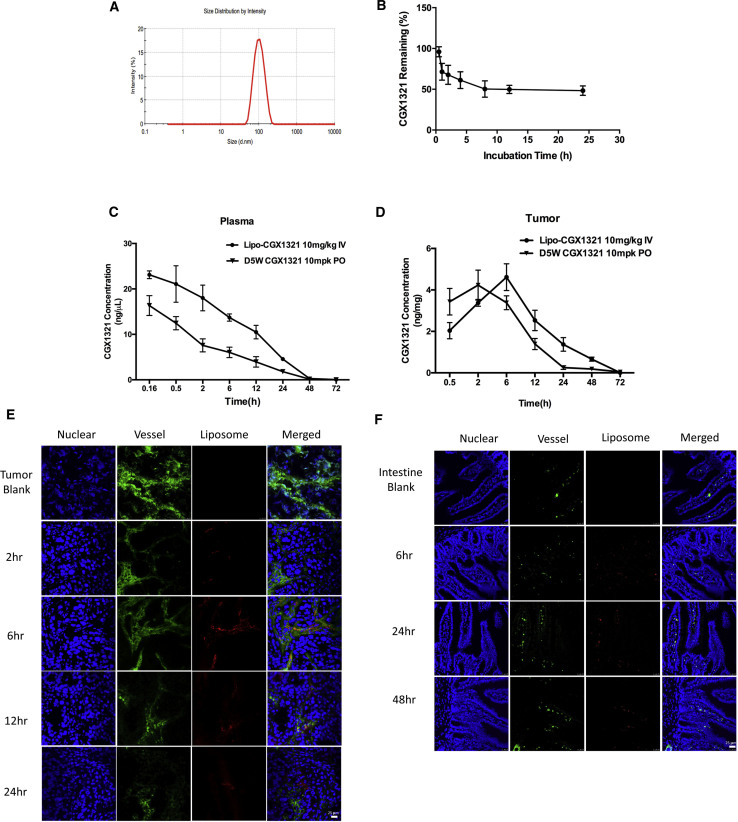

Despite its potent inhibition effects in vitro, CGX1321 has a very low solubility of 0.02 mg/mL at pH 7.4 in water, requiring special formulation for its usage in vivo via intravenous injection. More importantly, because free CGX1321 may interfere with normal cellular Wnt functions, we developed a formulation to encapsulate the drug with liposomes ∼100 nm in diameter (Figure 2A). The stability of CGX1321-loaded liposomes was analyzed by evaluating drug releases in vitro in the presence of 10% serum (Figure 2B). About 50% of the drug remained encapsulated inside liposomes for 24 h under experimental conditions. The pharmacokinetic properties of tail-vein-injected liposome-encapsulated CGX1321 differed from those of the orally administered CGX1321 (D5W formulation). The liposomal formulation had a longer half-life of 10.85 h instead of 6.29 h and higher retention in the tumor tissues (Figures 2C and 2D). To characterize liposome distribution in vivo, we followed liposome extravasation in different tissues to evaluate the differences in their intracellular liposome distribution and potential impacts on drug effectiveness. The liposomes were labeled using fluorescent DiI dye. Various tissue sections were analyzed. As shown in Figure 2E, in the tumor, liposomes (stained red) were found to begin accumulating in the tumor vessel (stained green) at 2 h, with accumulation peaking at 6 h. Afterward, liposomes remained in the tumor tissue and were cleared from blood vessels. Liposomes appeared to leak out easily into the tumor interstitial tissues. In intestinal immunofluorescence staining, the blood vessel image nearly overlaps with that of liposomes until 48 h. The result shows that liposomes stayed in intact micro-vessels in intestinal tissue, which had lower drug exposure since most of the drug was still encapsulated during circulation (Figure 2F). In liver, liposomes were mostly found in the para-vascular and sinusoid area (Figure S4). In summary, the distribution and accumulation of the liposome in the tumor tissues were more prominent.

Figure 2.

CGX1321 Liposome Formulation Changes Its Pharmacokinetics In Vivo

(A) Liposome-CGX1321 size distribution by Malvern particle size analyzer. (B) CGX1321 liposome stability analysis in vitro in the presence of 10% serum in PBS (pH 7.4); CGX1321 remaining in the dialysis tube was tested at different times points. (C) The pharmacokinetic curves of CGX1321 in D5W oral formulation or liposome formulations. Pharmacokinetic studies were done in GA007 xenograft mouse models; plasma was collected and CGX1321 concentration was measured at multi-time points (N = 3). (D) CXG1321 distribution in tumors from GA007 PDX mouse model (n = 3). CGX1321 concentrations were measured by LC-MS at multiple times post-dosing of liposome or D5W-formulated CGX1321. (E and F) Immunofluorescence staining in tumor (E) and intestine (F) from GA007 PDX mouse model after a single dosing of 10 mg/kg liposome-CGX1321 (liposome concentration is 50 mg/mL) via i.v. injection, detected by confocal microscopy. Scale bar, 25 μm.

CGX1321 Liposomes Inhibited Tumor Growth in LoVo Xenograft Model

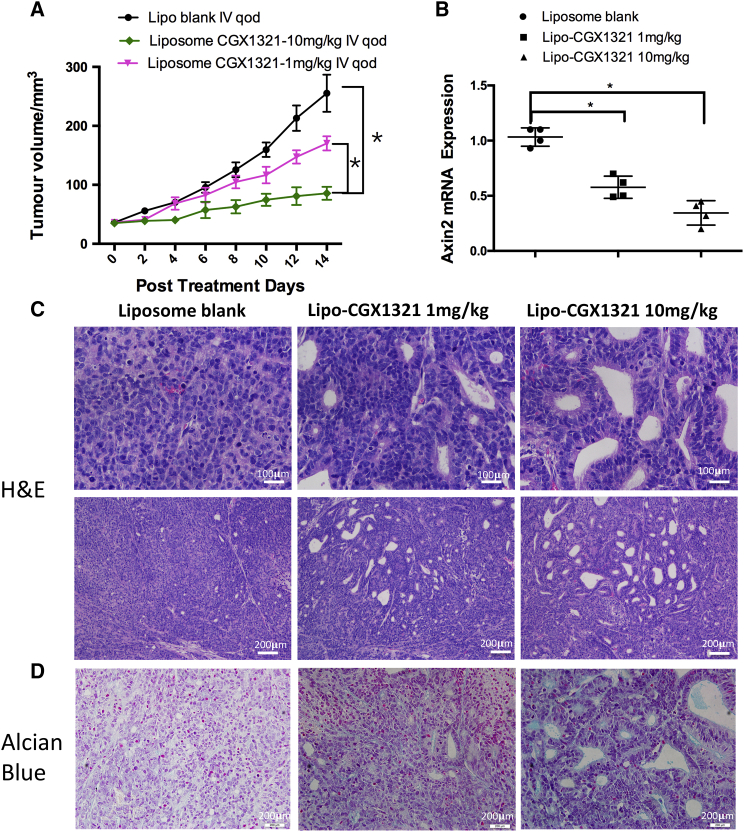

To test the Wnt inhibition effects and anti-tumor activity of CGX1321 liposomes in vivo, we first established a LoVo xenograft tumor model in nude mice. Then, LoVo xenograft mice were treated using CGX1321 liposome once every 2 days at two different doses (1 or 10 mg/kg). Tumor growth was significantly inhibited, compared with that of the liposome vehicle control group (Figure 3A). After 14 days, the mice were sacrificed and the tumor tissues were harvested for both histology and gene expression analysis. Axin2 mRNA level was used as an indicator for Wnt pathway activities. There was a dose-dependent reduction of Axin2 mRNA level in CGX1321 liposome-treated tumors (Figure 3B). Both H&E and Alcian blue staining of the tissues indicated distinctive treatment effects in the tumor tissues (Figures 3C and 3D). Compared with the control group, cells in the treated tissues appeared to have differentiated. In the differentiation area, cells were arranged in a one-by-one configuration. This effect increased with higher CGX1321 doses. The histological changes correlated with decreased Wnt signaling activities specifically in tumor tissues.

Figure 3.

CGX1321 Liposome Efficacies in LoVo Xenograft Mouse Model

(A) LoVo xenograft mice were treated with 10 mL/kg blank liposome, 1 mg/kg CGX1321 in liposome, or 10 mg/kg CGX1321 in liposome, i.v., q.o.d. for 14 days. The tumor volumes (mm3) were measured and plotted as mean with SEM (N = 8 per group), *p < 0.05. (B) Axin2 mRNA levels detected by qRT-PCR in vehicle and treatment groups 7 h after the last dose. Graphs represent mean with SEM (N = 4), *p < 0.05. (C) Representative images with H&E staining after 14 days of treatment. (D) Representative images of Alcian blue staining for mucin after 14 days of treatment.

CGX1321 Liposome Inhibited Tumor Growth in GA007 PDX Models

We further tested the effects of CGX1321 liposomes in patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models with aberrant Wnt activities. The GA007 PDX model was found to have high LGR5 and β-catenin mRNA levels (Figure 4A). Therefore, GA007 PDX mice were treated with CGX1321 liposomes once every 2 days at two different doses for 16 days. Data showed that CGX1321 liposome at 1 mg/kg resulted in significant tumor growth inhibition, while further increasing the dose did not show augmented inhibition (Figure 4B). Furthermore, these treatments also resulted in Wnt signaling inhibition, as indicated by Axin2 (Figure 4C). Histological analysis of tumor tissues after 16 days treatment showed greater tumor cell differentiation and apoptosis (Figure 4D). The treatment effects were more visually discernible under Alcian blue staining, with extensive mucin staining throughout the tissue structures (Figure 4E).

Figure 4.

Therapeutic Effects of CGX1321 Liposome Treatment in GA007 PDX Tumor

(A) LGR5 and β-catenin mRNA expression in GA007 by NanoString assay detection. (B) The tumor volumes (mm3) were measured and plotted as mean with SEM after CGX1321 liposome treatment for 16 days (N = 8 per group), **p < 0.01. (C) Axin2 mRNA levels in vehicle and treatment groups 7 h after final dosing, *p < 0.05. (D and E) H&E (D) and Alcian blue (E) staining of the tumor tissues. Tumor samples were from GA007 PDX mice, which were treated with 10 mL/kg liposome blank or 10 mg/kg CGX1321 in liposome, i.v., q.o.d. for 16 days.

CGX1321 Liposomes Caused LGR5+ CSCs Apoptosis in PDX Tumor Tissues

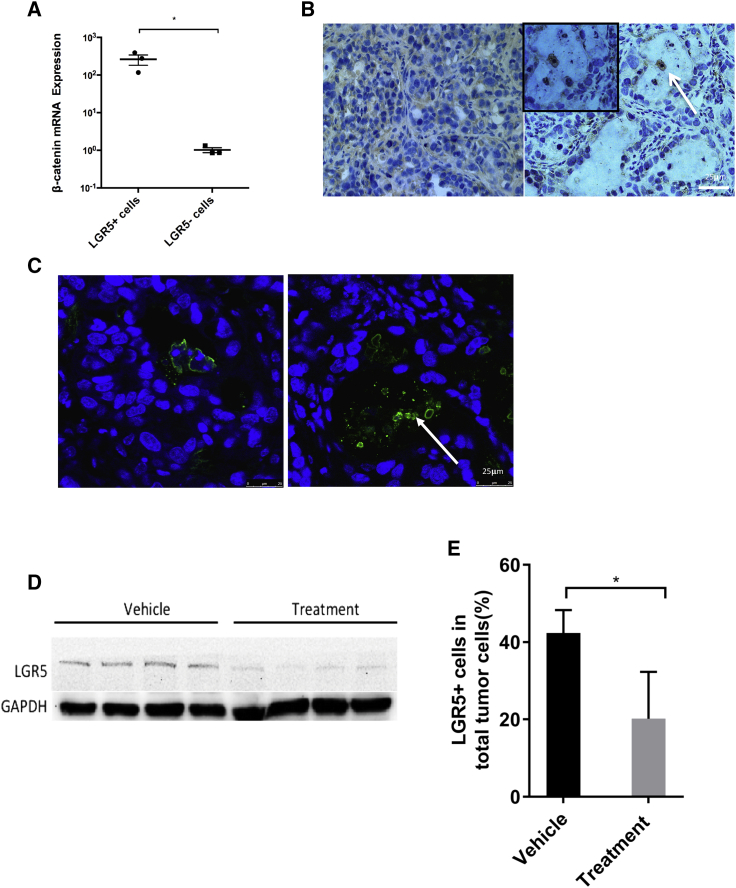

In order to understand the molecular mechanism of the anti-cancer effects of CGX1321 liposomes, we analyzed the various cells that constitute the PDX tumor tissue. We found that 42.4% ± 5.9% of cells were LGR5+ (Figure S5), and interestingly LGR5+ cells showed active Wnt signaling, as indicated by high β-catenin mRNA levels (Figure 5A). We also analyzed the features of LGR5+ cells in vivo and in vitro, after sorting them out by FACS from initial tumors. The LGR5+ cells showed the CSC property (Figure S6; Table S2). The CGX1321 liposome treatments caused mostly arrest of LGR5+ cell growth and apoptosis in the PDX tissues after 7 days treatment, based on immunohistochemistry (IHC) and TUNEL staining of the tissue sections (Figures 5B and 5C). Figure 5B shows dead and apoptotic LGR5+ cells in the debris after treatment. The overall LGR5 protein levels were greatly reduced (Figure 5D), and the numbers of LGR5+ cells in the tissue dropped from 42.4% ± 5.9% to 20.2% ± 12.1% (Figure 5E).

Figure 5.

LGR5+ Cells as Cancer Stem Cell Identification

(A) β-catenin mRNA expression in LGR5+ and LGR5− cells were detected by qPCR after FACS sorting. *p < 0.05. (B) H&E staining of the vehicle and treated tumor samples. The arrow indicates LGR5+ cell patches. (C) TUNEL assay of vehicle and treated tumor samples. Blue indicates nuclear staining, and the arrow indicates DNA fragments caused by apoptosis. (D) Western blot of LGR5 in vehicle and treatment groups (N = 4). (E) FACS analysis of LGR5+ cells in the vehicle group and treatment group.

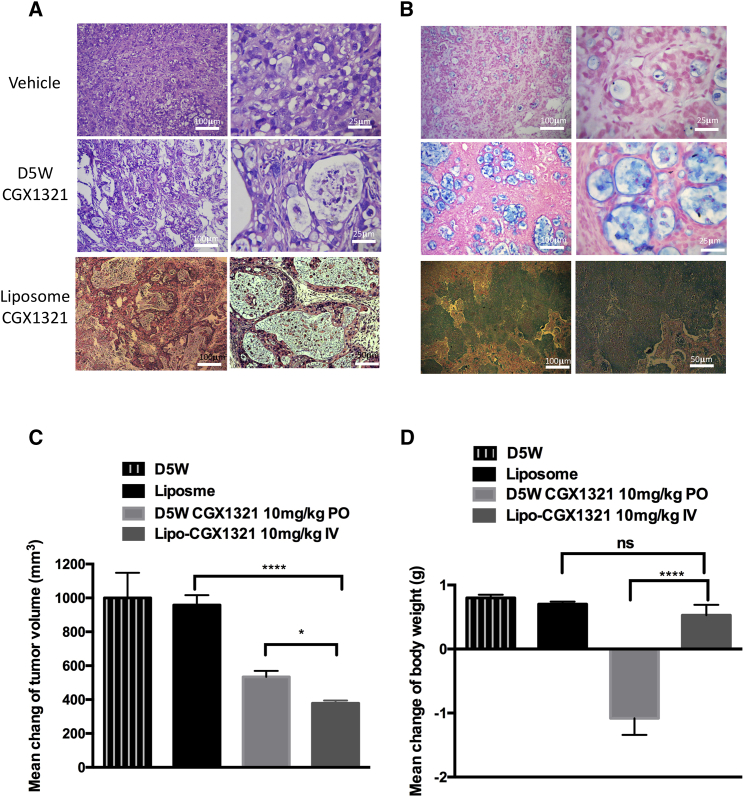

CGX1321 Liposomes Improve Drug Efficacy while Also Reducing Toxicity

Histological analysis of tissue sections showed higher drug efficacy of CGX1321 liposomes in GA007 PDX mouse model, when compared to orally dosed CGX1321. Tissue from the CGX1321 liposome-treated groups showed larger necrotic regions (Figure 6A). Alcian blue staining for GA007 PDX tumor again indicated profound extensive mucinous differentiation (Figure 6B). Tumor size reduction was significantly greater in the liposome-treatment groups compared with the oral-formulation group (Figure 6C). The CGX1321 liposomes had higher efficacy and better therapeutic index than CGX1321 oral dosing, particularly with targeting LGR5+ CSCs in the tumor. In addition, the liposomal formulation enhanced CGX1321 tolerance in mouse models. Mice treated with CGX1321 liposomes showed no decrease in body weight 14 days after treatment, while orally dosed mice showed significant weight loss (Figure 6D).

Figure 6.

CGX1321 in Liposome Formulation Enhances CGX1321 Tolerance and Decreased the Toxicity to Mice

H&E (A) and Alcian blue (B) staining of the vehicle and treated tumor samples. (C) Tumor growth was plotted by mean with SEM (n = 8). Tumor samples were from GA007 PDX mice, which were treated with 10 mL/kg liposome blank, 10 mg/kg CGX1321 in D5W, p.o., q.d., or 10 mg/kg CGX1321 in liposome, i.v., q.o.d., for 14 days. (D) Bodyweight changes were calculated before and after CGX1321 in D5W or liposome formulation treatments for 14 days (n = 8), ***p < 0.0001.

Discussion

A number of Wnt pathway inhibitors are currently under development to target the canonical Wnt-pathway-driven aberrant cancers. The LGK974 molecular compound, a porcupine inhibitor developed by Novartis, is being tested on lung and pancreatic cancers in the clinical trial phase I.19, 24 Wnt antibodies are also being developed to inhibit the Wnt pathway, including Frizzled receptor OMP18R5 or Fzd8-Fc fusion protein OMP-54F28. Both are in clinical trial studies on solid tumors currently.25, 26 However, blocking the canonical Wnt pathway is not without risk.21 The canonical Wnt pathway is involved in maintaining stem cell pluripotency and lineage specification in normal tissues.20

CGX1321 is another highly specific and potent porcupine inhibitor under development. It has very low solubility in water (0.02 mg/mL). For animal experiments, the oral dosing in 10 mg/kg was given in suspension of PEG400 and solutal (D5W). In our study, we observed drops in mouse bodyweight following treatments via oral dosing (Figure 6D). Weight loss could be the result of off-target effects due to canonical Wnt blocking in non-cancerous cells, such as in intestine.

In contrast, liposomes containing polyethylene glycol (PEG) has been shown to have long half-life in circulation and to accumulate preferentially in tumor tissues.22, 27, 28, 29, 30 Therefore, we developed the liposome formulation in order to improve CGX1321 solubility as well as to improve its distribution in tumor tissue. The analysis of CGX1321 liposome distribution in Figure 2F suggested the liposomes remain confined to the blood vessels and do not leak into the crypt in the intestine. This is probably because the permeability of vessel in intestine is not high enough for 100-nm liposome to leak outside. Encouragingly, mice treated with the liposomal drug maintained their body weights even after repeated doses, compared with the significant weight loss in the non-liposome oral-dosing group (Figure 6D).

The pharmacological effects of CGX1321 in tumor tissues were mostly directed against LGR5+ cells. LGR5 is a well-characterized member of the Wnt family of co-receptors.31 LGR5+ cells isolated from PDX cancer tissue in this study had been confirmed to show high Wnt signaling activities and effective tumor-initiating properties (Figure S6; Table S2). After treatment, the expression of Wnt pathway biomarker Axin2 decreased significantly (Figure 4C). Evidences indicated that CGX1321 with either oral formulation or liposome formation promote differentiation of LGR5+ cancer stem cells, as shown by Alcian blue staining (Figures 3D and 4E). The effects were very similar to RSPO3 antibody treatment to RSPO3-PTPRK fusion tumors.15 The antibody study showed stem cells were reduced by blocking Wnt pathway with RSPO3 antibody. Both treatments resulted in patches of cell death and mucinous holes in the tumor tissues, which indicated CSC differentiation.25 The effect of CGX1321 liposomes in both LoVo and GA007 tumors were more prominent when compared to the results of the oral treatment. The fluorescence-labeled liposomes were shown to distribute and persist more extensively in tumor tissues (Figure 2E), whereas the delayed drug release from liposomes improve the focused CSC elimination effects. Consequently, the effect of drug to LGR5+ cells was enlarged in tumor as a result of liposome CGX1321. In conclusion, the high retention of CGX1321 contributed to the therapeutic efficacy by liposome-encapsulating drug.

Based on the data we presented, inhibitors of the Wnt pathway could be packed by liposome to enhance its tumor inhibition effects and to reduce its off-target toxicities. To extend our findings, we will test liposome enveloping other Wnt inhibitors that may interfere with over-activation of Wnt in animal models in the future. Thus, changing formulation such as utilizing liposome could be a valuable approach to avoid toxicity and enhance efficacy in drug discovery and development.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines and Tumor Samples

The LGR5 positive cell lines Hek293 and LoVo were obtained from the ATCC. HEK293-TCF was a gift from Curegenix. Cells were cultured in relevant cell culture medium recommended by ATCC, supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS). Testing for potential mycoplasma contamination was done by ELISA. PDX frozen samples were prepared and provided by Shanghai LIDE Biotech. Samples were obtained with ethics committee approval and with consent from patients. All procedures were performed according to the LIDE Human Samples Procedure Guideline and Policies.

H&E and Alcian Blue

Xenograft tumor samples were fixed in 10% (v/v) neutral-buffered formalin for 6–24 h, processed, and paraffin embedded. Tissue sections were cut using a microtome. The paraffin-embedded tissues sections on glass slides were washed twice with xylene for 5 min each, followed by incubation in 100% ethanol twice, and sequential rehydration in 95%, 70%, 50%, 30% ethanol, and finally water. The tissue sections on slides were stained in hematoxylin solution for 10 min, washed in running water for 5 min, differentiated in 1% acid alcohol for 30 s, and finally washed in running water for 1 min. Subsequently, the slides were rinsed in 95% ethanol and counterstained in eosin solution for 1 min. Finally, tissue sections were dehydrated in 95% ethanol for 5 min, cleared in xylene for 5 min, and mounted with a xylene-based mounting medium.

The Alcian blue staining of the paraffin sections was done after de-paraffinization by immersing in 3% (v/v) acetic acid solution for 3 min and staining using 1% alcian blue (Sigma) in 3% acetic acid solution at pH 1.0 for 30 min. The slides were then washed in running water for 10 min and counterstained with nuclear fast red 0.1% (Sangon) for 5 min. Finally, slides were washed again in water and mounted.

Immunohistochemistry

IHC staining was done after de-paraffinization, rehydration, and antigen retrieval by microwaving for 10 min in citric acid buffer (pH 6.0), followed by washing in PBS for 2 min.32 Endogenous peroxidases were inactivated with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 min (Zhongshang Jinqiao SP-9000). Then, slides were washed three times in PBS and blocked in 5% donkey serum for 1 h. Primary antibodies (Abgent, AP2745A) were diluted in PBS at a 1:40 ratio and incubated on tissue sections overnight. Slides were washed with PBS three times, after which secondary antibody anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (Abgent, ASS1006) diluted at 1:2,000 in PBS was added and incubated for 1 h at room temperature (25°C). Finally, after washing, freshly prepared 3,3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB) substrates were incubated on tissue sections at room temperature until visually discernable staining developed. Tissue sections were washed with water and counterstained with hematoxylin. Slides were sequentially dehydrated, rinsed twice with 95% ethanol, rinsed twice with xylene, and mounted before imaging.

NanoString Assay

NanoString assay directly measures the gene expression by digital counting of nucleic acids. This assay employs the nCounter analysis system, which is based on a digital molecular barcoding technology, which uses molecular “barcodes” and microscopic imaging to detect and count unique transcripts in one hybridization reaction.33 The assays were conducted by Wuxi AppTec (Shanghai, China) following the manufacturer’s manual.

Sorting of LGR5+ Cells by Flow Cytometry

PDX primary cells were obtained by digesting the explanted tumor into single cell suspension. Tumor fragments were dissociated for 2 hr in a mixture of 2 U/mL of dispase (Yisen Bio) and 2,000 U/mL of collagenase VI (Yisen Bio) in pH 7.4 PBS at 37°C by shaking repeatedly. The dissociated sample was then filtered (40 μm pore size) and washed in PBS. Single cell suspensions from PDX tumor tissues were obtained in 0.5% BSA (Sangon) DMEM medium. Specifically, 2 × 106 cells were suspended in 300 μL of PBS containing diluted primary antibody LGR5 (Abcam, ab-75732) at 1:40 and incubated on ice for 30 min. The cells were rinsed in PBS and labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) conjugated secondary antibody at 1:100 (CWBio, CW0219S) for 30 min on ice. Flow cytometric analysis and cell sorting were performed on a Beckman Coulter MoFloXDP under 20 psi with a 100-mm nozzle.

Spherical Cell Culture

Sorted LGR5+ and LGR5− cells were further cultured in 24-well ultra-low attachment plates (Corning) in DMEM/F12 (Gibco) medium containing 20 ng/mL epidermal growth factor (EGF) (Qianchen Bio), 10 ng/mL fibroblast growth factor (Qianchen Bio), 5 μg/mL insulin (Sigma), 0.4% BSA, and 2% B27 (Invitrogen). Cells were cultured for 5 days at 37°C with 5% CO2.

LGR5+ Cell Xenograft Model

All in vivo studies and establishments of tumor models have been approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Shanghai Jiaotong University, under IACUC protocol no. A2016039. All animal procedures and animal care were performed according to institutional animal research guidelines and were also in compliance with Shanghai Laboratory animal management regulations. LGR5+/− single cell suspensions from PDX tumor tissues were re-suspended in 0.5% BSA DMEM after flow sorting and then diluted in 50% 1640 medium and 50% matrigel (Corning) at varying cell concentrations. 100 μL of the cell suspension was inoculated subcutaneously in each 6- to 8-week-old female nude mouse (SLAC Shanghai). Tumor sizes were measured by caliper, with tumor volume calculated as (length × width2)/2.34

Analysis of PDX mRNA Samples

The RNeasy mini kit (QIAGEN) was used for mRNA extraction from PDX tissue samples and cells. First-strand cDNA was synthesized using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). Real-time quantitative PCR was performed by using the first-strand cDNA for RNA expression, using 250 nM forward and reverse primers and SYBR green PCR master mix (Bio-Rad) on an ABI 7900 fast real-time PCR machine (Applied Biosystems). The primer sequences and PCR conditions are summarized in Table S1. RNA expression levels were calculated as the relative expression compared with human GAPDH.

Western Blot

PDX GA007 tumors were dissociated and homogenized in RAPID buffer with 1% PMSF (Beyotime). Protein extracts were combined with loading dye (Invitrogen), boiled, and loaded onto 4%–15% SDS-PAGE gel (Invitrogen). After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Invitrogen) using semi-dry trans-blot (Bio-Rad). The membrane was blocked by using 5% milk for 30 min then incubated with the respective primary antibodies (Abcam, Ab75850) diluted in TBST (Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 and 2% BSA) overnight at 4°C. The blots were washed and incubated with the 800CW donkey anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies (LI-COR) in TBST. The blotting signals were detected using an Odyssey scanner (LI-COR).35

Cell Proliferation Assay

The cell proliferation assay was measured using the CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution cell proliferation assay kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega).36, 37 HEK293 or LoVo cells were cultured by seeding 10,000 cells into each well in a 96-well-plate with CGX1321 conditioned medium mixed with 10 μL per well of CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution reagent. After 1 h incubation in cell culture incubator, absorbance at 490 nm was measured every 24 h using Bio-Rad microplate reader 680.

Luciferase Reporter Assay

HEK293-TCF reporter cells were treated with Wnt3a (10 ng/mL)-, RSPO2 (10 ng/mL)-, or CGX1321 (18 μM)-conditioned medium. Luciferase activity detection was conducted with luciferase assay system kits (Promega).

CGX1321 Liposome Formulation

Drug-loaded liposomes were composed of hydrogenated soybean phosphatidylcholine (HSPC), cholesterol, and 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanol-amine-N-[methoxy (polyethylene glycol)-2000] (DSPE-PEG2000) with a molar ratio of 55:40:5. The liposome had a lipid concentration of 50 mg/mL. CGX1321 liposomes were prepared using the remote loading method through transmembrane ammonium sulfate gradient, similar to Doxil.30 The uncapsulated drug was removed by dialysis against sucrose. The final concentration of CGX1321 in liposome was 1.233 mg/mL. Fluorescence-labeled liposomes were generated by incorporating 1% (molar percentage) of DiI (Sigma) in the same formulation.

CGX1321 Liposome Stability Testing

The liposome suspension after active drug loading was dialyzed against 50× volume of 10% sucrose buffer with a 100-kDa cutoff membrane for removal of unencapsulated drugs from the liposome preparation. The dialysis buffer was changed three times, and each time the samples were dialyzed for 4–6 hours. For liposome stability analysis in vitro, the CGX1321 liposomes with a final concentration of 1 mg/mL were added into PBS with 10% FBS and put into a dialysis tube (Spectra-Por Float-A-Lyzer G2, 100 kDa molecular weight [MW] cutoff, 10 mL; Sigma) in 50× volume of PBS with 10% FBS at 37°C with gentle agitation. The liposome samples remaining in the dialysis tube were collected at different times points and assayed for the amount of CGX1321 inside liposomes by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS). Thus, any released drugs would be diluted out in the buffer. Only liposome-encapsulated drugs would remain.

CGX1321 Efficacy Studies In Vivo

PDX mice were sacrificed to obtain tumor tissue. Tumors were cut into 3-mm3 pieces and then re-implanted subcutaneously in 6- to 8-week-old female nude mice (SLAC, Shanghai, China) for in vivo studies. Compound efficacy studies were started when the tumors grew to 100–200 mm3 in size. Compound CGX1321 was received as a gift from Curegenix (Guangzhou, China; batch, lot no. PT-C14010931-D14001). The oral vehicle formulation (D5W) was composed of 20% PEG400, 25% Solutol (20% Solutol in purified water, w/v), and 55% dextrose (5% dextrose in purified water, w/v). Animals in the D5W oral formulation group were dosed once a day (q.d.) orally (p.o.). Animals in the liposome formulation group were dosed every other day (q.o.d.) via intravenous injection (i.v.). Tumor volumes were calculated based on the modified ellipsoidal formula.38 Endpoints for mice were when tumor sizes reached above 2,000 mm3 or after 14 days of treatment.

Confocal Analysis

Fluorescently labeled liposomes were used for distribution studies. After dosing with fluorescent liposomes, tumor samples were collected at different time points and fast frozen after embedding. Tumor, intestine, and liver sections (7 μm) were mounted and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. Immunofluorescent staining was performed using CD34 antibody for vessel staining (Ab81298, Abcam) and DAPI. Images were taken using a scanning confocal microscope (Leica TCS SP2). The tumor sections were also used for TUNEL staining (Roche Laboratories).

CGX1321 Pharmacokinetic Properties In Vivo

Plasma and tissue samples were collected at various time points after a single dose of the 10 mg/kg D5W oral formulation or the 10 mg/kg liposomal formulation. Plasma and methanol were mixed at a 1:4 ratio, vortexed thoroughly to subside protein, and then centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. Supernatant was removed, and samples were diluted 500-fold with methanol. 200 μL of diluted samples were transferred to 96-well plates, and drug concentration was measured via liquid chromatograph-mass spectrometer (LC-MS). Drug concentration was measured using 50-mg tissue samples that were collected from the tumor, liver, skin, or intestine and then washed in PBS. All samples were homogenized in 250 μL PBS. The lysate was processed in the same method as the plasma. The tissue supernatant diluted in methanol was analyzed by LC-MS.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Data are presented as means ± SEM of three independent experiments. Two-way ANOVA was used to calculate statistical significance of tumor volumes, while a paired t test is used for animal bodyweight statistics.

Author Contributions

Y.X. and C.L. conceived and initiated the research. Y.X. and C.L. designed the research. C.L., Y.L., J.C., N.Z., X.W., F.X., and M.T. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. C.L. and Y.X. wrote and/or edited the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Alex Chen for proofreading the manuscript. This work is supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China grants No. 31571019 and No. 81690262.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.06.013.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.Mohammed M.K., Shao C., Wang J., Wei Q., Wang X., Collier Z., Tang S., Liu H., Zhang F., Huang J. Wnt/β-catenin signaling plays an ever-expanding role in stem cell self-renewal, tumorigenesis and cancer chemoresistance. Genes Dis. 2016;3:11–40. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clevers H., Nusse R. Wnt/β-catenin signaling and disease. Cell. 2012;149:1192–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stewart D.J. Wnt signaling pathway in non-small cell lung cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2014;106:djt356. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krausova M., Korinek V. Wnt signaling in adult intestinal stem cells and cancer. Cell. Signal. 2014;26:570–579. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clevers H. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell. 2006;127:469–480. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Howe L.R., Brown A.M. Wnt signaling and breast cancer. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2004;3:36–41. doi: 10.4161/cbt.3.1.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wodarz A., Nusse R. Mechanisms of Wnt signaling in development. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1998;14:59–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.14.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacDonald B.T., Tamai K., He X. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: components, mechanisms, and diseases. Dev. Cell. 2009;17:9–26. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Komiya Y., Habas R. Wnt signal transduction pathways. Organogenesis. 2008;4:68–75. doi: 10.4161/org.4.2.5851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.To K.F., Chan M.W., Leung W.K., Yu J., Tong J.H., Lee T.L., Chan F.K., Sung J.J. Alterations of frizzled (FzE3) and secreted frizzled related protein (hsFRP) expression in gastric cancer. Life Sci. 2001;70:483–489. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(01)01422-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katoh M., Katoh M. Molecular genetics and targeted therapy of WNT-related human diseases (Review) Int. J. Mol. Med. 2017;40:587–606. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.3071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ilmer M., Boiles A.R., Regel I., Yokoi K., Michalski C.W., Wistuba I.I., Rodriguez J., Alt E., Vykoukal J. RSPO2 Enhances Canonical Wnt Signaling to Confer Stemness-Associated Traits to Susceptible Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Cancer Res. 2015;75:1883–1896. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li C., Cao J., Zhang N., Tu M., Xu F., Wei S., Chen X., Xu Y. Identification of RSPO2 Fusion Mutations and Target Therapy Using a Porcupine Inhibitor. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:14244. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-32652-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang X., Hao H.-X., Growney J.D., Woolfenden S., Bottiglio C., Ng N., Lu B., Hsieh M.H., Bagdasarian L., Meyer R. Inactivating mutations of RNF43 confer Wnt dependency in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:12649–12654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307218110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Storm E.E., Durinck S., de Sousa e Melo F., Tremayne J., Kljavin N., Tan C., Ye X., Chiu C., Pham T., Hongo J.A. Targeting PTPRK-RSPO3 colon tumours promotes differentiation and loss of stem-cell function. Nature. 2016;529:97–100. doi: 10.1038/nature16466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lenz H.J., Kahn M. Safely targeting cancer stem cells via selective catenin coactivator antagonism. Cancer Sci. 2014;105:1087–1092. doi: 10.1111/cas.12471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang S.M., Mishina Y.M., Liu S., Cheung A., Stegmeier F., Michaud G.A., Charlat O., Wiellette E., Zhang Y., Wiessner S. Tankyrase inhibition stabilizes axin and antagonizes Wnt signalling. Nature. 2009;461:614–620. doi: 10.1038/nature08356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen B., Dodge M.E., Tang W., Lu J., Ma Z., Fan C.W., Wei S., Hao W., Kilgore J., Williams N.S. Small molecule-mediated disruption of Wnt-dependent signaling in tissue regeneration and cancer. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009;5:100–107. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu J., Pan S., Hsieh M.H., Ng N., Sun F., Wang T., Kasibhatla S., Schuller A.G., Li A.G., Cheng D. Targeting Wnt-driven cancer through the inhibition of Porcupine by LGK974. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:20224–20229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314239110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clevers H., Loh K.M., Nusse R. Stem cell signaling. An integral program for tissue renewal and regeneration: Wnt signaling and stem cell control. Science. 2014;346:1248012. doi: 10.1126/science.1248012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kahn M. Can we safely target the WNT pathway? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014;13:513–532. doi: 10.1038/nrd4233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maeda H. The enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect in tumor vasculature: the key role of tumor-selective macromolecular drug targeting. Adv. Enzyme Regul. 2001;41:189–207. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2571(00)00013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang X., Gaspard J.P., Chung D.C. Regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor by the Wnt and K-ras pathways in colonic neoplasia. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6050–6054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guimaraes P.P.G., Tan M., Tammela T., Wu K., Chung A., Oberli M., Wang K., Spektor R., Riley R.S., Viana C.T.R. Potent in vivo lung cancer Wnt signaling inhibition via cyclodextrin-LGK974 inclusion complexes. J. Control. Release. 2018;290:75–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2018.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gurney A., Axelrod F., Bond C.J., Cain J., Chartier C., Donigan L., Fischer M., Chaudhari A., Ji M., Kapoun A.M. Wnt pathway inhibition via the targeting of Frizzled receptors results in decreased growth and tumorigenicity of human tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:11717–11722. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120068109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Le P.N., McDermott J.D., Jimeno A. Targeting the Wnt pathway in human cancers: therapeutic targeting with a focus on OMP-54F28. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015;146:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh R., Lillard J.W., Jr. Nanoparticle-based targeted drug delivery. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2009;86:215–223. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silverman J.A., Deitcher S.R. Marqibo® (vincristine sulfate liposome injection) improves the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of vincristine. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2013;71:555–564. doi: 10.1007/s00280-012-2042-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang J.A., Anyarambhatla G., Ma L., Ugwu S., Xuan T., Sardone T., Ahmad I. Development and characterization of a novel Cremophor EL free liposome-based paclitaxel (LEP-ETU) formulation. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2005;59:177–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barenholz Y. Doxil®—the first FDA-approved nano-drug: lessons learned. J. Control. Release. 2012;160:117–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carmon K.S., Lin Q., Gong X., Thomas A., Liu Q. LGR5 interacts and cointernalizes with Wnt receptors to modulate Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2012;32:2054–2064. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00272-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Natarajan G., Perriotte-Olson C., Bhinderwala F., Powers R., Desouza C.V., Talmon G.A., Yuhang J., Zimmerman M.C., Kabanov A.V., Saraswathi V. Nanoformulated copper/zinc superoxide dismutase exerts differential effects on glucose vs lipid homeostasis depending on the diet composition possibly via altered AMPK signaling. Transl. Res. 2017;188:10–26. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2017.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cesano A. nCounter(®) PanCancer Immune Profiling Panel (NanoString Technologies, Inc., Seattle, WA) J. Immunother. Cancer. 2015;3:42. doi: 10.1186/s40425-015-0088-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiang J., Zhang Y., Chuai S., Wang Z., Zheng D., Xu F., Zhang Y., Li C., Liang Y., Chen Z. Trastuzumab (herceptin) targets gastric cancer stem cells characterized by CD90 phenotype. Oncogene. 2012;31:671–682. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiang Y., Arounleut P., Rheiner S., Bae Y., Kabanov A.V., Milligan C., Manickam D.S. SOD1 nanozyme with reduced toxicity and MPS accumulation. J. Control. Release. 2016;231:38–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Endo H., Owada S., Inagaki Y., Shida Y., Tatemichi M. Glucose starvation induces LKB1-AMPK-mediated MMP-9 expression in cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:10122. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-28074-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Promega. Measuring Absorbance Using the CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay with the GloMax Discover System. Promega Application Notes, AN261. 2013. https://www.promega.com/resources/pubhub/applications-notes/measuring-absorbance-with-celltiter96-proliferation-assay-and-glomax-discover-system-application/

- 38.Euhus D.M., Hudd C., LaRegina M.C., Johnson F.E. Tumor measurement in the nude mouse. J. Surg. Oncol. 1986;31:229–234. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930310402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.