Abstract

Objective

Since less invasive endovascular treatment was introduced to South Korea in 1994, a considerable proportion of endovascular treatments have been performed by neuroradiology doctors, and endovascular treatments by vascular neurosurgeons have recently increased. However, few specific statistics are known regarding how many endovascular treatments are performed by neurosurgeons. Thus, authors compared endovascular treatments collaboratively performed by vascular neurosurgeons with all cases throughout South Korea from 2013 to 2017 to elucidate the role of neurosurgeons in the field of endovascular treatment in South Korea.

Methods

The Society of Korean Endovascular Neurosurgeons (SKEN) has issued annual reports every year since 2014. These reports cover statistics on endovascular treatments collaboratively or individually performed by SKEN members from 2013 to 2017. The data was requested and collected from vascular neurosurgeons in various hospitals. The study involved 77 hospitals in its first year, and 100 in its last. National statistics on endovascular treatment from all over South Korea were obtained from the Healthcare Bigdata Hub website of the Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service based on the Electronic Data Interchange (EDI) codes (in the case of intra-arterial (IA) thrombolysis, however, statistics were based on a combination of the EDI and I63 codes, a cerebral infarction disease code) from 2013 to 2017. These two data sets were directly compared and the ratios were obtained.

Results

Regionally, during the entire study period, endovascular treatments by SKEN members were most common in Gyeonggi-do, followed by Seoul and Busan. Among the endovascular treatments, conventional cerebral angiography was the most common, followed by cerebral aneurysmal coiling, endovascular treatments for ischemic stroke, and finally endovascular treatments for vascular malformation and tumor embolization. The number of endovascular treatments performed by SKEN members increased every year.

Conclusion

The SKEN members have been responsible for the major role of endovascular treatments in South Korea for the recent 5 years. This was achieved through the perseverance of senior members who started out in the midst of hardship, the establishment of standards for the training/certification of endovascular neurosurgery, and the enthusiasm of current SKEN members who followed. To provide better treatment to patients, we will have to make further progress in SKEN.

Keywords: Endovascular procedures, Big data, Data interpretation, Statistical

INTRODUCTION

We live in an era of many medical upheavals. For instance, the development of technology and medical knowledge due to material engineering and basic sciences have led to rapid advances in medical equipment. In addition, rapid changes in national medical policies, such as introduction of telemedicine, abolition of uncovered health services or the reduced workload for residents as 80-hour per week, have changed the medical environment [16]. Vascular neurosurgeons must adapt to these changes to stay current. Recently, vascular neurosurgery has become more popular, even though it is perceived as 3D-jobs in the neurosurgical field, because vascular neurosurgeons have begun to perform less invasive endovascular treatment as well as the traditional open surgical treatments. In fact, younger vascular neurosurgeons view endovascular treatment as a necessity, not an option, and so-called “hybrid” vascular neurosurgeons who can perform both craniotomies and endovascular surgery are taken for granted. Relatedly, the residents’ training regulations of the Korean Neurosurgical Society have been changed to allow more endovascular treatment in training programs.

Although, a considerable proportion of endovascular treatment in South Korea since 1994 has been carried out by neuroradiology doctors, endovascular treatment performed by vascular neurosurgeons had been increased gradually, and they have increased much more since the establishment of standards for the training and certification of endovascular neurosurgery in South Korea has been firstly published [17]. However, few specific statistics are known regarding how many endovascular treatments are performed by neurosurgeons, so the role of neurosurgeons in this field is unclear. For this reason, the annual reports of the Society of Korean Endovascular Neurosurgeons (SKEN) from 2013 to 2017 have included a statistical report on endovascular treatment performed by or with the participation of vascular neurosurgeons. In the present study, authors compared endovascular treatment cases by vascular neurosurgeons of the SKEN annual reports with data obtained from the nationwide Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (HIRA) of South Korea from 2013 to 2017. In this way, authors ascertained the pattern of endovascular treatment in South Korea and examined the role of vascular neurosurgeons in the field of endovascular treatment in South Korea.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data collection and period in annual report of SKEN from 2013 to 2017

The SKEN has been issuing annual reports since 2014; these include statistics on all endovascular treatments performed alone or collaboratively with another clinician, such as a neuroradiologist, by SKEN members between 2013 and 2017. These data were collected using a data sheet that recorded the number of endovascular treatments performed in each year. Firstly, the editorial director of the annual report notified each hospital via e-mail. The hospitals then sent data via e-mail using the data sheet (Fig. 1). The data were also requested and collected from vascular neurosurgeons of various hospitals, including certified institutions of the SKEN via one-on-one telephone calls and text messages by the editorial director. This data collection was carried out over about 3 months each year from 2014 to 2018. The number of hospitals involved ranged from 77 to 100, and the number of endovascular treatments was assumed to be the number of patients, except in the case of aneurysms, whereby the number of aneurysm itself was recorded. In this regard, the report differed from the HIRA, in which the number of patients with aneurysm was counted. This was taken into account during data analysis. The present study analyzed these clinical data from annual SKEN report between 2013 and 2017.

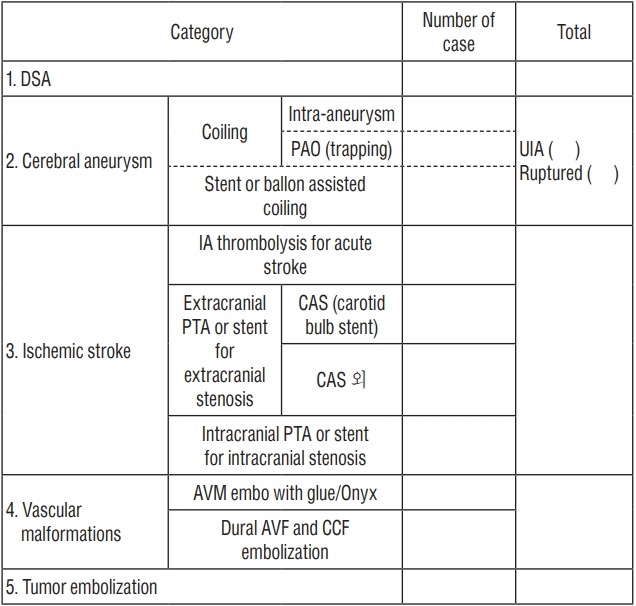

Fig. 1.

Required statistical data sheet delivered to SKEN members. The number of aneurysmal treatments reported in this annual report was counted as the number of aneurysms, which is different from the number in the HIRA, which was counted by patient. SKEN : The Society of Korean Endovascular Neurosurgeons, HIRA : the Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service, DSA : digital subtraction angiography, PAO : parent artery occlusion, UIA : unruptured intracranial aneurysms, PTA : percutaneous transluminal angioplasty, CAS : carotid artery stenting, AVM : arteriovenous malformation, AVF : arteriovenous fistula, CCF : carotid-cavernous stula.

Data collection and period from the Healthcare Bigdata Hub of HIRA

National statistics on endovascular treatment in South Korea were obtained from the Healthcare Bigdata Hub website of the HIRA. The target period for data collection was also 2013–2017. These data were collected in accordance with the Electronic Data Interchange (EDI) code, which was matched to the endovascular treatments on the data sheet distributed to SKEN members (Table 1). However, in the case of intra-arterial (IA) thrombolysis, data collection was based on a combination of the EDI and I63 codes, a cerebral infarction disease code, because the HIRA provided additional data on combining the EDI and I63 codes. We believe that the combined data are more accurate than data from the EDI code only.

Table 1.

Endovascular treatments and EDI codes matched

| Endovascular treatments | EDI code |

|---|---|

| DSA | HA 601, HA602, HA603, HA604, HA605, HA606, HA691, HA692, HA693, HA694 |

| Coiling | M1662 |

| Stent or balloon assisted coiling | M1661 |

| IA thrombolysis for cerebral infarction* | M6630, M6631, M6633, M6636 + I63 |

| Extracranial PTA or Stent | M6602, M6594 |

| Intracranial PTA or Stent | M6601, M6593 |

| AVM embolization | M1663, M1667, M1668, M1669 |

| Dural AVF or CCF embolization | M1664, M1665, M1666 |

| Tumor embolization | M1673, M1674, M1675 |

Exceptionally, in the case of IA thrombolysis, it was based by combining EDI code and I63, a cerebral infarction disease code.

EDI : Electronic Data Interchange, DSA : digital subtraction angiography, IA : intra-arterial, PTA : percutaneous transluminal angioplasty, AVM : arteriovenous malformation, AVF : arteriovenous fistula, CCF : carotid-cavernous fistula

Data analysis

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of CHA Bundang Medical Center, CHA Univeristy School of Medicine on July 4th, 2019 as a deliberative exemption (IRB No. CHAMC 2019-06-035). Authors directly compared the data collected from SKEN with the nationwide data from the Healthcare Bigdata Hub of the HIRA. However, the category of extracranial percutaneous transluminal angioplasty or stent including carotid artery stenting (“EC-PTA or stent [CAS]”) and EC-PTA or stent excluding carotid artery stenting (“EC-PTA or stent [the rest of CAS]”) in the data collected from SKEN were combined into “EC-PTA or stent (including CAS)” and compared to the “EC-PTA or stent (including CAS)” in HIRA’s data. Authors also obtained the ratio between the data collected from SKEN and the nationwide data. Using these data, authors analyzed the flow and trends of endovascular treatments performed in South Korea from 2013 to 2017.

RESULTS

Endovascular treatments performed collaboratively by vascular neurosurgeons from 2013 to 2017

In the years 2013 to 2017, 77, 82, 85, 93, and 100 hospitals participated in the survey, respectively. The data for each hospital were analyzed by region and category, and the overall data were analyzed according to each category (Table 2). Regionally, in all the years analyzed, endovascular treatments were most common in Gyeonggi-do, followed by Seoul and Busan (Fig. 2). With regards to specific endovascular treatments, conventional cerebral angiography was the most common (that is digital subtraction angiography; “DSA”), followed by cerebral aneurysmal coiling and treatments for ischemic stroke, vascular malformation, and tumor embolization (Fig. 3).

Table 2.

Data from SKEN members according to category from 2013 to 2017

| Year | The number of participating hospitals | DSA | Cerebral aneurysm |

Ischemic stroke |

Vascular malformation |

Tumor embolization | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coiling | PAO | Stent or balloon | Sub total* | UIA | Ruptured | Sub total† | IA thrombolysis for cerebral infarction | EC PTA or stent (CAS) | EC PTA or stent (the rest of CAS) | IC PTA or stent | AVM | Dural AVF or CCF | ||||

| 2013 | 77 | 25889 | 3275 | 83 | 1944 | 5302 | 3303 | 1999 | 5302 | 1179 | 1197 | 0 | 422 | 177 | 184 | 295 |

| 2014 | 82 | 28354 | 3577 | 77 | 2211 | 5865 | 3595 | 2270 | 5865 | 1570 | 1378 | 194 | 466 | 226 | 170 | 258 |

| 2015 | 85 | 33537 | 4022 | 107 | 2481 | 6610 | 4233 | 2377 | 6610 | 1738 | 1425 | 300 | 540 | 246 | 243 | 349 |

| 2016 | 93 | 38860 | 4513 | 112 | 3104 | 7729 | 5030 | 2699 | 7729 | 2187 | 1598 | 240 | 532 | 249 | 305 | 427 |

| 2017 | 100 | 44596 | 4935 | 118 | 3348 | 8401 | 5563 | 2838 | 8401 | 2666 | 1820 | 226 | 719 | 221 | 276 | 401 |

| Ratio of 2017/2013 | 129.9 | 172.3 | 150.7 | 142.2 | 172.2 | 158.4 | 168.4 | 142.0 | 158.4 | 226.1 | 152 | 116.5‡ | 170.4 | 124.9 | 150 | 135.9 |

The meaning of this 'subtotal' is the sum of the 'coiling', 'PAO' and 'Stent or balloon'.

The meaning of this 'subtotal' is the sum of the 'UIA' and 'Ruputred'.

Ratio of 2014 to 2017.

SKEN : The Society of Korean Endovascular Neurosurgeons, DSA : digital subtraction angiography, PAO : parent artery occlusion, UIA : unruptured intracranial aneurysms, IA : intra-arterial, ECPTA : extracranial percutaneous transluminal angioplasty, CAS : carotid artery stenting, ICPTA : intracranial percutaneous transluminal angioplasty, AVM : arteriovenous malformation, AVF : arteriovenous fistula, CCF : carotid-cavernous fistula

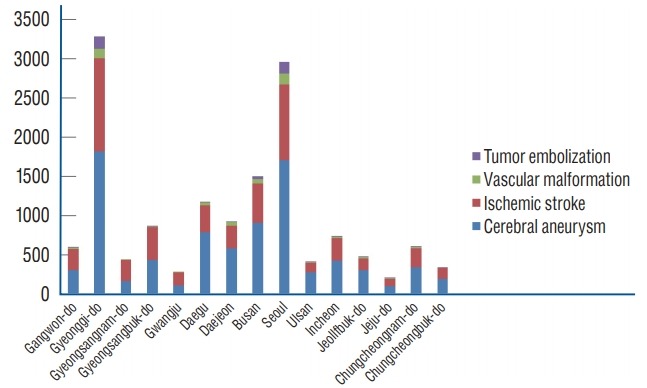

Fig. 2.

Graphical data from the SKEN members according to region and category in 2017. Endovascular treatments were the most common in Gyeonggi-do, followed by Seoul and Busan. This trend was also observed in all periods from 2013 to 2017. SKEN : The Society of Korean Endovascular Neurosurgeons.

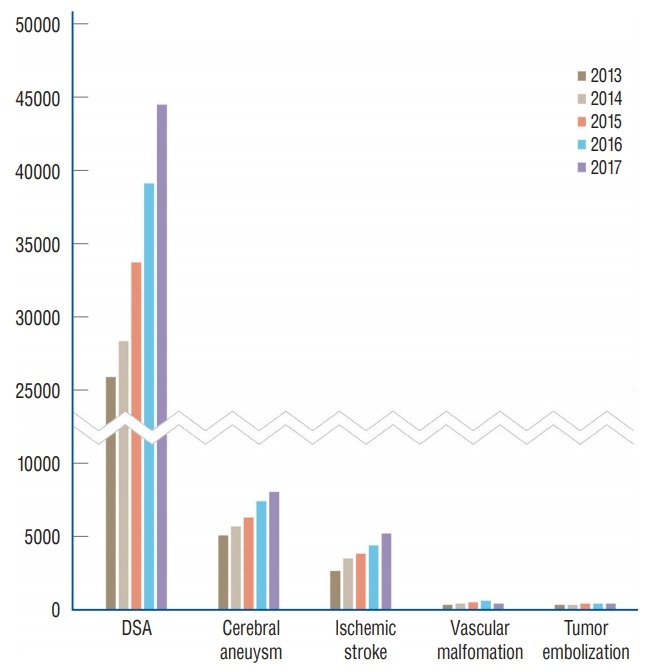

Fig. 3.

Serial data from SKEN members according to each category. With the exception of digital subtraction angiography (DSA), cerebral aneurysmal coiling was the most common, endovascular treatments for ischemic stroke were second, followed by endovascular treatments for vascular malformation and tumor embolization. SKEN : The Society of Korean Endovascular Neurosurgeons.

The number of hospitals participating in data collection gradually increased during the study period, as did the number of endovascular treatments performed collaboratively by SKEN members. However, the increase in the number of endovascular treatments was greater than the increase in the number of participating hospitals. Specifically, the rate of increase in each category was higher than the rate of increase in the number of participating hospitals (from 77 to 100; 29.9%), with the exception of “EC-PTA or stent (the rest of CAS)”, which increased from 194 to 226 patients (16.5%), and treatment for arteriovenous malformation (“AVM”), which increased from 177 to 221 patients (24.9%) (Table 2). The rates of increase exceeded 50% in “DSA”, simple coilings (“coiling”), stent- or balloon-assisted coilings (“stent or balloon”), “IA thrombolysis for cerebral infarction”, “EC-PTA or stent (CAS)”, “intracranial (IC)-PTA or stent” and dural arteriovenous fistula or carotid- cavernous fistula (“dural AVF or CCF”), especially in the case of “IA thrombolysis for cerebral infarction”, which showed an increase of more than 200% (Table 2). The increase in the number of unruptured intracranial aneurysms (“UIA”, from 3303 to 5563; 68.4%) was higher than the increase in the number of ruptured aneurysms (“Ruptured”, from 1999 to 2838; 42%).

Nationwide data from the Healthcare Bigdata Hub of the HIRA from 2013 to 2017

Nationwide data from the HIRA between 2013 and 2017 were analyzed by region and category, and the overall data were analyzed according to each category (Tables 3-8). Regionally, endovascular treatment was the most common in Seoul, followed by Gyeonggi-do and Busan in all years analyzed. Concerning specific endovascular treatments, “DSA” was the most common, followed by cerebral aneurysmal coiling and treatments for ischemic stroke, vascular malformation, and tumor embolization.

Table 3.

Comparison between data collected from SKEN members and nationwide data from the Healthcare Bigdata Hub of the HIRA from 2013 to 2017

| Year | DSA |

Cerebral aneurysm |

Ischemic stroke |

Vascular malformation |

Tumor embolization |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coiling+PAO |

Stent or balloon |

IA thrombolysis for cerebral infarction |

EC PTA or stent (including CAS) |

IC PTA or stent |

AVM |

Dural AVF or CCF |

||||||||||||

| SKEN | HA601-6, HA691-4 | SKEN | M1662 | SKEN | M1661 | SKEN* | M6630, 1,3,6 + I63 | SKEN | M6602, M6594 | SKEN | M6601, M6593 | SKEN | M1663, 7-9 | SKEN | M1664-6 | SKEN | M1673-5 | |

| 2013 | 25889 (55.6%) | 46541 | 3358 (101.5%) | 3307 | 1944 (60.1%) | 3236 | 1179 (72.8%) | 1620 | 1197 (52.1%) | 2297 | 422 (66.2%) | 637 | 177 (60.8%) | 291 | 184 (76.0%) | 242 | 295 (47.9%) | 616 |

| 2014 | 28354 (54.6%) | 51975 | 3654 (98.6%) | 3707 | 2211 (64.9%) | 3409 | 1570 (83.5%) | 1880 | 1572 (66.7%) | 2358 | 466 (72.5%) | 643 | 226 (61.4%) | 368 | 170 (62.7%) | 271 | 258 (41.5%) | 622 |

| 2015 | 33537 (49.6%) | 67651 | 4129 (102.0%) | 4050 | 2481 (67.2%) | 3691 | 1738 (69.0%) | 2520 | 1725 (71.0%) | 2431 | 540 (77.1%) | 700 | 246 (70.7%) | 348 | 243 (85.6%) | 284 | 349 (52.8%) | 661 |

| 2016 | 38860 (50.5%) | 77024 | 4625 (105.9%) | 4369 | 3104 (66.3%) | 4684 | 2187 (75.1%) | 2912 | 1838 (68.8%) | 2672 | 532 (73.9%) | 720 | 249 (73.9%) | 337 | 305 (95.3%) | 320 | 427 (59.1%) | 722 |

| 2017 | 44596 (53.6%) | 83268 | 5053 (108.5%) | 4655 | 3348 (63.7%) | 5258 | 2666 (77.5%) | 3442 | 2046 (69.9%) | 2929 | 719 (87.2%) | 825 | 221 (66.2%) | 334 | 276 (80.5%) | 343 | 401 (45.7%) | 878 |

| Ratio of 2017/2013 | 172.3 | 178.9 | 150.5 | 140.8 | 172.2 | 162.5 | 226.1 | 212.5 | 170.9 | 127.5 | 170.4 | 129.5 | 124.9 | 114.8 | 150 | 141.7 | 135.9 | 142.5 |

These data from SKEN members may include non-cerebral infarction cases, for example, when IA thrombectomy were performed for the thromboembolism that occurred during any endovascular procedures.

SKEN : The Society of Korean Endovascular Neurosurgeons, DSA : digital subtraction angiography, PAO : parent artery occlusion, IA : intra-arterial, EC : extracranial, PTA : percutaneous transluminal angioplasty, CAS : carotid artery stenting, IC : intracranial, AVM : arteriovenous malformation, AVF : arteriovenous fistula, CCF : carotid-cavernous fistula

Table 4.

Comparison between data collected from SKEN members and nationwide data from the Healthcare Bigdata Hub of the HIRA in 2013

| Category | DSA | Cerebral aneurysm |

Ischemic stroke |

Vascular malformation |

Tumor embolization | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coiling+PAO |

Stent or balloon |

IIA thrombolysis for cerebral infarction |

EC PTA or stent (including CAS) |

IC PTA or stent |

AVM |

Dural AVF or CCF |

||||||||||||

| SKEN | HA601-6, HA691-4 | SKEN | M1662 | SKEN | M1661 | SKEN | M6630, M6631, M6633, M6636 + I63 | SKEN | M6602, M6594 | SKEN | M6601, M6593 | SKEN | M1663, M1667, M1668, M1669 | SKEN | M1664, M1665, M1666 | SKEN | M1673, M1674, M1675 | |

| Seoul | 3270 | 14448 | 774 | 1163 | 218 | 833 | 97 | 302 | 164 | 592 | 31 | 171 | 52 | 135 | 55 | 141 | 69 | 366 |

| Busan | 3843 | 4452 | 377 | 312 | 315 | 385 | 201 | 157 | 164 | 190 | 71 | 60 | 24 | 26 | 24 | 20 | 48 | 45 |

| Incheon | 2207 | 2048 | 171 | 156 | 71 | 64 | 83 | 57 | 72 | 85 | 41 | 24 | 9 | 9 | 7 | 0 | 13 | 12 |

| Daegu | 2922 | 3152 | 307 | 241 | 184 | 170 | 179 | 200 | 78 | 143 | 14 | 27 | 22 | 20 | 13 | 5 | 3 | 8 |

| Gwangju | 384 | 1491 | 91 | 85 | 57 | 56 | 9 | 117 | 26 | 87 | 10 | 38 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Daejeon | 1450 | 1927 | 205 | 193 | 122 | 159 | 91 | 81 | 50 | 136 | 31 | 36 | 8 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Ulsan | 724 | 791 | 133 | 13 | 69 | 167 | 36 | 26 | 18 | 24 | 8 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 3 |

| Gyeonggi-do | 5351 | 8463 | 605 | 497 | 446 | 671 | 152 | 213 | 235 | 440 | 70 | 117 | 32 | 44 | 49 | 41 | 133 | 143 |

| Gangwon-do | 660 | 959 | 78 | 62 | 64 | 59 | 54 | 53 | 66 | 85 | 19 | 21 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 4 | 6 | 4 |

| Chungcheongbuk-do | 974 | 1272 | 87 | 73 | 70 | 116 | 39 | 60 | 54 | 88 | 8 | 18 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Chungcheongnam-do | 509 | 1225 | 33 | 107 | 61 | 134 | 12 | 22 | 33 | 93 | 33 | 32 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Jeollabuk-do | 1264 | 1854 | 112 | 121 | 81 | 60 | 42 | 150 | 112 | 135 | 35 | 54 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 8 | 7 |

| Jeollanam-do | 0 | 109 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Gyeongsangbuk-do | 1571 | 2258 | 165 | 49 | 61 | 155 | 101 | 71 | 73 | 81 | 25 | 21 | 13 | 16 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Gyeongsangnam-do | 207 | 1570 | 170 | 186 | 89 | 180 | 61 | 91 | 31 | 97 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 11 | 6 | 17 |

| Jeju-do | 553 | 522 | 50 | 49 | 36 | 27 | 22 | 20 | 21 | 21 | 26 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Total | 25889 (55.6%) | 46541 | 3358 (101.5%) | 3307 | 1944 (60.1%) | 3236 | 1179 (72.8%) | 1620 | 1197 (52.1%) | 2297 | 422 (66.2%) | 637 | 177 (60.8%) | 291 | 184 (76.0%) | 242 | 295 (47.9%) | 616 |

SKEN : The Society of Korean Endovascular Neurosurgeons, HIRA : the Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service, DSA : digital subtraction angiography, PAO : parent artery occlusion, IA : intra-arterial, EC : extracranial, PTA : percutaneous transluminal angioplasty, CAS : carotid artery stenting, AVM : arteriovenous malformation, AVF : arteriovenous fistula, CCF : carotid-cavernous fistula

Table 5.

Comparison between data collected from SKEN members and nationwide data from the Healthcare Bigdata Hub of the HIRA in 2014

| Category | DSA | Cerebral aneurysm |

Ischemic stroke |

Vascular malformation |

Tumor embolization | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coiling+PAO |

Stent or balloon |

IIA thrombolysis for cerebral infarction |

EC PTA or stent (including CAS) |

IC PTA or stent |

AVM |

Dural AVF or CCF |

||||||||||||

| SKEN | HA601-6, HA691-4 | SKEN | M1662 | SKEN | M1661 | SKEN | M6630, M6631, M6633, M6636 + I63 | SKEN | M6602, M6594 | SKEN | M6601, M6593 | SKEN | M1663, M1667, M1668, M1669 | SKEN | M1664, M1665, M1666 | SKEN | M1673, M1674, M1675 | |

| Seoul | 3446 | 15556 | 733 | 1218 | 256 | 825 | 142 | 296 | 177 | 540 | 23 | 127 | 35 | 161 | 40 | 130 | 71 | 390 |

| Busan | 4082 | 5031 | 478 | 346 | 386 | 462 | 263 | 208 | 224 | 253 | 52 | 60 | 40 | 30 | 28 | 25 | 26 | 38 |

| Incheon | 1922 | 2276 | 203 | 186 | 70 | 74 | 113 | 64 | 60 | 64 | 42 | 21 | 16 | 16 | 8 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Daegu | 3117 | 3516 | 346 | 301 | 222 | 247 | 180 | 258 | 86 | 136 | 17 | 20 | 33 | 31 | 11 | 10 | 4 | 7 |

| Gwangju | 300 | 1556 | 68 | 60 | 82 | 77 | 20 | 106 | 20 | 74 | 3 | 33 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| Daejeon | 1985 | 2227 | 337 | 277 | 150 | 151 | 102 | 95 | 127 | 165 | 38 | 35 | 16 | 15 | 12 | 11 | 18 | 18 |

| Ulsan | 756 | 933 | 75 | 33 | 33 | 120 | 34 | 31 | 10 | 19 | 10 | 7 | 9 | 11 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 7 |

| Gyeonggi-do | 6593 | 10150 | 658 | 582 | 548 | 771 | 222 | 314 | 368 | 462 | 156 | 157 | 49 | 57 | 46 | 54 | 111 | 128 |

| Gangwon-do | 764 | 1124 | 109 | 96 | 57 | 56 | 43 | 33 | 85 | 75 | 37 | 36 | 9 | 8 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Chungcheongbuk-do | 504 | 1005 | 58 | 50 | 37 | 98 | 23 | 45 | 28 | 53 | 1 | 12 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Chungcheongnam-do | 731 | 1430 | 119 | 116 | 127 | 172 | 33 | 29 | 75 | 109 | 15 | 23 | 5 | 13 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| Jeollabuk-do | 1249 | 1798 | 112 | 133 | 96 | 40 | 136 | 161 | 146 | 165 | 33 | 40 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 10 |

| Jeollanam-do | 0 | 302 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 22 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Gyeongsangbuk-do | 2209 | 2843 | 182 | 75 | 58 | 139 | 112 | 80 | 96 | 92 | 31 | 27 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Gyeongsangnam-do | 356 | 1575 | 123 | 176 | 60 | 151 | 86 | 102 | 40 | 99 | 1 | 10 | 3 | 8 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 5 |

| Jeju-do | 340 | 653 | 53 | 57 | 29 | 22 | 61 | 36 | 30 | 40 | 7 | 24 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Total | 28354 (54.6%) | 51975 | 3654 (98.6%) | 3707 | 2211 (64.9%) | 3409 | 1570 (83.5%) | 1880 | 1572 (66.7%) | 2358 | 466 (72.5%) | 643 | 226 (61.4%) | 368 | 170 (62.7%) | 271 | 258 (41.5%) | 622 |

SKEN : The Society of Korean Endovascular Neurosurgeons, HIRA : the Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service, DSA : digital subtraction angiography, PAO : parent artery occlusion, IA : intra-arterial, EC : extracranial, PTA : percutaneous transluminal angioplasty, CAS : carotid artery stenting, AVM : arteriovenous malformation, AVF : arteriovenous fistula, CCF : carotid-cavernous fistula

Table 6.

Comparison between data collected from SKEN members and nationwide data from the Healthcare Bigdata Hub of the HIRA in 2015

| Category | DSA | Cerebral aneurysm |

Ischemic stroke |

Vascular malformation |

Tumor embolization | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coiling+PAO |

Stent or balloon |

IIA thrombolysis for cerebral infarction |

EC PTA or stent (including CAS) |

IC PTA or stent |

AVM |

Dural AVF or CCF |

||||||||||||

| SKEN | HA601-6, HA691-4 | SKEN | M1662 | SKEN | M1661 | SKEN | M6630, M6631, M6633, M6636 + I63 | SKEN | M6602, M6594 | SKEN | M6601, M6593 | SKEN | M1663, M1667, M1668, M1669 | SKEN | M1664, M1665, M1666 | SKEN | M1673, M1674, M1675 | |

| Seoul | 6046 | 19383 | 852 | 1180 | 421 | 948 | 238 | 445 | 379 | 624 | 61 | 157 | 92 | 171 | 95 | 133 | 108 | 394 |

| Busan | 4462 | 6629 | 508 | 393 | 387 | 468 | 239 | 228 | 186 | 226 | 51 | 50 | 45 | 21 | 21 | 26 | 51 | 28 |

| Incheon | 1789 | 2693 | 254 | 236 | 69 | 66 | 83 | 95 | 42 | 64 | 15 | 18 | 9 | 12 | 6 | 3 | 9 | 7 |

| Daegu | 2201 | 4163 | 262 | 304 | 157 | 193 | 106 | 267 | 65 | 132 | 10 | 20 | 9 | 23 | 9 | 11 | 1 | 12 |

| Gwangju | 643 | 1915 | 77 | 68 | 54 | 52 | 30 | 123 | 14 | 49 | 2 | 16 | 2 | 7 | 10 | 14 | 3 | 1 |

| Daejeon | 2245 | 2924 | 368 | 295 | 176 | 179 | 114 | 97 | 109 | 120 | 37 | 39 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 7 | 10 | 14 |

| Ulsan | 767 | 1545 | 131 | 69 | 51 | 151 | 44 | 58 | 17 | 23 | 13 | 21 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 20 |

| Gyeonggi-do | 8447 | 13818 | 759 | 675 | 679 | 922 | 329 | 471 | 417 | 548 | 158 | 150 | 52 | 59 | 47 | 51 | 124 | 132 |

| Gangwon-do | 963 | 1709 | 153 | 131 | 65 | 69 | 62 | 52 | 111 | 90 | 43 | 56 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 6 | 3 | 2 |

| Chungcheongbuk-do | 432 | 1815 | 72 | 83 | 41 | 73 | 43 | 94 | 44 | 64 | 4 | 26 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Chungcheongnam-do | 769 | 1874 | 107 | 113 | 109 | 155 | 32 | 44 | 68 | 129 | 22 | 25 | 6 | 12 | 8 | 5 | 10 | 13 |

| Jeollabuk-do | 1151 | 2067 | 146 | 151 | 72 | 39 | 49 | 175 | 97 | 137 | 37 | 46 | 5 | 6 | 16 | 11 | 9 | 9 |

| Jeollanam-do | 0 | 543 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 23 | 0 | 21 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Gyeongsangbuk-do | 2222 | 3798 | 250 | 128 | 66 | 164 | 144 | 140 | 99 | 91 | 29 | 35 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| Gyeongsangnam-do | 926 | 2004 | 118 | 152 | 106 | 180 | 162 | 171 | 62 | 88 | 42 | 16 | 1 | 10 | 3 | 9 | 5 | 13 |

| Jeju-do | 474 | 771 | 72 | 61 | 28 | 20 | 63 | 37 | 15 | 25 | 16 | 17 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 11 | 7 |

| Total | 33537 (49.6%) | 67651 | 4129 (102.0%) | 4050 | 2481 (67.2%) | 3691 | 1738 (69.0%) | 2520 | 1725 (71.0%) | 2431 | 540 (77.1%) | 700 | 246 (70.7%) | 348 | 243 (85.6%) | 284 | 349 (52.8%) | 661 |

SKEN : The Society of Korean Endovascular Neurosurgeons, HIRA : the Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service, DSA : digital subtraction angiography, PAO : parent artery occlusion, IA : intra-arterial, EC : extracranial, PTA : percutaneous transluminal angioplasty, CAS : carotid artery stenting, AVM : arteriovenous malformation, AVF : arteriovenous fistula, CCF : carotid-cavernous fistula

Table 7.

Comparison between data collected from SKEN members and nationwide data from the Healthcare Bigdata Hub of the HIRA in 2016

| Category | DSA | Cerebral aneurysm |

Ischemic stroke |

Vascular malformation |

Tumor embolization | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coiling+PAO |

Stent or balloon |

IIA thrombolysis for cerebral infarction |

EC PTA or stent (including CAS) |

IC PTA or stent |

AVM |

Dural AVF or CCF |

||||||||||||

| SKEN | HA601-6, HA691-4 | SKEN | M1662 | SKEN | M1661 | SKEN | M6630, M6631, M6633, M6636 + I63 | SKEN | M6602, M6594 | SKEN | M6601, M6593 | SKEN | M1663, M1667, M1668, M1669 | SKEN | M1664, M1665, M1666 | SKEN | M1673, M1674, M1675 | |

| Seoul | 8380 | 21915 | 1055 | 1266 | 570 | 1273 | 327 | 502 | 397 | 609 | 85 | 150 | 92 | 167 | 139 | 157 | 168 | 439 |

| Busan | 4602 | 7074 | 548 | 464 | 485 | 529 | 243 | 231 | 211 | 226 | 35 | 36 | 38 | 26 | 27 | 24 | 47 | 49 |

| Incheon | 2015 | 2998 | 249 | 261 | 81 | 71 | 136 | 144 | 67 | 95 | 11 | 13 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 10 |

| Daegu | 3894 | 4983 | 370 | 330 | 245 | 228 | 260 | 285 | 79 | 137 | 18 | 12 | 12 | 20 | 13 | 13 | 4 | 14 |

| Gwangju | 488 | 2120 | 63 | 63 | 55 | 57 | 51 | 142 | 26 | 88 | 2 | 25 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 12 | 2 | 1 |

| Daejeon | 2061 | 3305 | 309 | 221 | 166 | 274 | 124 | 115 | 96 | 157 | 35 | 42 | 19 | 22 | 9 | 5 | 10 | 10 |

| Ulsan | 283 | 1936 | 101 | 91 | 66 | 198 | 35 | 52 | 17 | 41 | 12 | 11 | 7 | 10 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 12 |

| Gyeonggi-do | 8579 | 15140 | 938 | 726 | 834 | 1076 | 375 | 559 | 455 | 534 | 152 | 183 | 43 | 48 | 61 | 54 | 154 | 139 |

| Gangwon-do | 1514 | 2042 | 162 | 144 | 89 | 79 | 93 | 80 | 110 | 85 | 51 | 60 | 7 | 11 | 14 | 8 | 9 | 2 |

| Chungcheongbuk-do | 615 | 2165 | 85 | 106 | 45 | 114 | 30 | 86 | 48 | 87 | 13 | 27 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Chungcheongnam-do | 1005 | 2495 | 123 | 134 | 158 | 228 | 58 | 79 | 65 | 174 | 32 | 41 | 9 | 4 | 10 | 9 | 7 | 6 |

| Jeollabuk-do | 1317 | 2548 | 179 | 209 | 119 | 55 | 68 | 151 | 96 | 150 | 22 | 46 | 7 | 2 | 10 | 4 | 3 | 8 |

| Jeollanam-do | 0 | 784 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 18 | 0 | 71 | 0 | 44 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Gyeongsangbuk-do | 2669 | 4068 | 292 | 159 | 83 | 186 | 152 | 137 | 83 | 83 | 29 | 31 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 3 |

| Gyeongsangnam-do | 827 | 2717 | 79 | 123 | 87 | 273 | 182 | 236 | 58 | 131 | 33 | 22 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 16 | 1 | 19 |

| Jeju-do | 611 | 734 | 72 | 62 | 21 | 25 | 53 | 42 | 30 | 31 | 2 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 8 |

| Total | 38860 (50.5%) | 77024 | 4625 (105.9%) | 4369 | 3104 (66.3%) | 4684 | 2187 (75.1%) | 2912 | 1838 (68.8%) | 2672 | 532 (73.9%) | 720 | 249 (73.9%) | 337 | 305 (95.3%) | 320 | 427 (59.1%) | 722 |

SKEN : The Society of Korean Endovascular Neurosurgeons, HIRA : the Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service, DSA : digital subtraction angiography, PAO : parent artery occlusion, IA : intra-arterial, EC : extracranial, PTA : percutaneous transluminal angioplasty, CAS : carotid artery stenting, AVM : arteriovenous malformation, AVF : arteriovenous fistula, CCF : carotid-cavernous fistula

Table 8.

Comparison between data collected from SKEN members and nationwide data from the Healthcare Bigdata Hub of the HIRA in 2017

| Category | DSA | Cerebral aneurysm |

Ischemic stroke |

Vascular malformation |

Tumor embolization | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coiling+PAO |

Stent or balloon |

IIA thrombolysis for cerebral infarction |

EC PTA or stent (including CAS) |

IC PTA or stent |

AVM |

Dural AVF or CCF |

||||||||||||

| SKEN | HA601-6, HA691-4 | SKEN | M1662 | SKEN | M1661 | SKEN | M6630, M6631, M6633, M6636 + I63 | SKEN | M6602, M6594 | SKEN | M6601, M6593 | SKEN | M1663, M1667, M1668, M1669 | SKEN | M1664, M1665, M1666 | SKEN | M1673, M1674, M1675 | |

| Seoul | 8964 | 24477 | 1162 | 1392 | 537 | 1468 | 434 | 642 | 427 | 667 | 103 | 195 | 50 | 142 | 91 | 165 | 147 | 531 |

| Busan | 5310 | 7326 | 482 | 478 | 418 | 566 | 250 | 282 | 214 | 250 | 43 | 48 | 21 | 24 | 32 | 30 | 38 | 49 |

| Incheon | 2470 | 3525 | 314 | 272 | 107 | 114 | 161 | 158 | 102 | 125 | 28 | 30 | 5 | 6 | 10 | 7 | 2 | 8 |

| Daegu | 4012 | 4565 | 501 | 391 | 279 | 300 | 250 | 263 | 82 | 147 | 16 | 28 | 13 | 24 | 20 | 13 | 4 | 2 |

| Gwangju | 412 | 2358 | 56 | 55 | 53 | 48 | 82 | 196 | 41 | 114 | 40 | 22 | 10 | 9 | 1 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| Daejeon | 2632 | 3345 | 340 | 204 | 243 | 296 | 147 | 130 | 102 | 141 | 37 | 32 | 25 | 20 | 17 | 11 | 8 | 8 |

| Ulsan | 839 | 2258 | 129 | 82 | 142 | 227 | 67 | 75 | 32 | 41 | 19 | 15 | 10 | 13 | 6 | 3 | 9 | 15 |

| Gyeonggi-do | 10667 | 17000 | 958 | 741 | 857 | 1162 | 507 | 658 | 485 | 607 | 195 | 180 | 45 | 45 | 70 | 62 | 161 | 213 |

| Gangwon-do | 1869 | 2286 | 192 | 171 | 108 | 97 | 127 | 114 | 101 | 91 | 39 | 38 | 10 | 12 | 7 | 4 | 6 | 1 |

| Chungcheongbuk-do | 501 | 2145 | 79 | 121 | 111 | 142 | 37 | 116 | 73 | 114 | 28 | 42 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 3 |

| Chungcheongnam-do | 1602 | 2576 | 166 | 152 | 175 | 213 | 73 | 74 | 123 | 147 | 41 | 48 | 8 | 10 | 7 | 4 | 12 | 12 |

| Jeollabuk-do | 1088 | 2508 | 196 | 201 | 109 | 74 | 42 | 165 | 53 | 179 | 50 | 37 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 2 | 5 |

| Jeollanam-do | 0 | 700 | 0 | 19 | 0 | 26 | 0 | 70 | 0 | 37 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Gyeongsangbuk-do | 2957 | 4347 | 311 | 158 | 116 | 213 | 238 | 192 | 140 | 126 | 44 | 47 | 9 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 5 |

| Gyeongsangnam-do | 726 | 3193 | 94 | 148 | 65 | 282 | 197 | 262 | 48 | 118 | 24 | 38 | 2 | 9 | 7 | 15 | 0 | 14 |

| Jeju-do | 547 | 659 | 73 | 70 | 28 | 30 | 54 | 45 | 23 | 25 | 12 | 17 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 12 |

| Total | 44596 (53.6%) | 83268 | 5053 (108.5%) | 4655 | 3348 (63.7%) | 5258 | 2666 (77.5%) | 3442 | 2046 (69.9%) | 2929 | 719 (87.2%) | 825 | 221 (66.2%) | 334 | 276 (80.5%) | 343 | 401 (45.7%) | 878 |

SKEN : The Society of Korean Endovascular Neurosurgeons, HIRA : the Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service, DSA : digital subtraction angiography, PAO : parent artery occlusion, IA : intra-arterial, EC : extracranial, PTA : percutaneous transluminal angioplasty, CAS : carotid artery stenting, AVM : arteriovenous malformation, AVF : arteriovenous fistula, CCF : carotid-cavernous fistula

Additionally, national data showed an overall increase in the number of endovascular treatments during the study period, and the rates of increase exceeded 50% in “DSA”, aneurysm (“coiling + parent artery occlusion [“PAO”]” and “stent or balloon”), and “IA thrombolysis for cerebral infarction”; “IA thrombolysis for cerebral infarction” showed an increase of more than 200% (Table 3). The rates of increase were about 40% in “dural AVF or CCF” and “tumor embolization”, about 30% in “EC-PTA or stent (including CAS)” and intracranial percutaneous transluminal angioplasty or stent (“IC-PTA or stent”), and about 15% in “AVM”.

Comparison between data collected from SKEN members and nationwide data from the Healthcare Bigdata Hub of the HIRA from 2013 to 2017

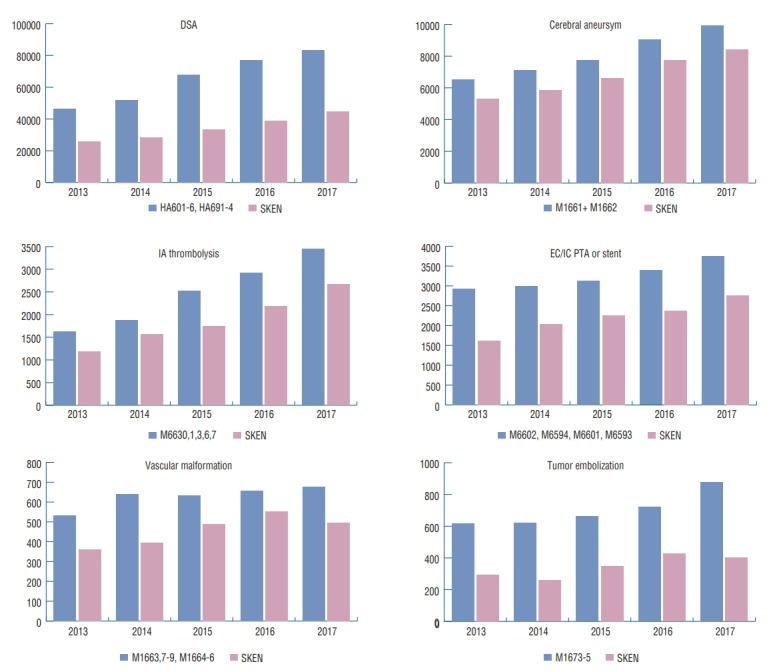

During the 5 years from 2013 to 2017, SKEN members participated in 50–55% of “DSA”, 70–80% of “IA thrombolysis for cerebral infarction”, 50–70% of “EC-PTA or stent (including CAS)”, 65–85% of “IC-PTA or stent”, 60–75% of “AVM”, 75–95% of “dural AVF or CCF”, 40–60% of “tumor embolization” (Tables 3-8; Fig. 4). Although the overall number of endovascular treatments performed by SKEN members increased during the study period, there were no significant changes in the categories “DSA”, “IA thrombolysis for cerebral infarction”, “AVM”, “dural AVF or CCF”, and “tumor embolization” with regard to the ratio of data from SKEN members to those from HIRA. An increase in the ratio was observed for “EC-PTA or stent (including CAS)” and “IC-PTA or stent” (Tables 3-8). In the category of aneurysm treatments, SKEN members participated in approximately 100–108% of “coiling” and about 60–65% of “stent or balloon” (Tables 3-8). Because the number of aneurysmal treatments involving SKEN members was counted as the number of aneurysms, while the number of aneurysmal treatments in the HIRA was counted as the number of patients, authors could not directly compare the two data sets, so the derived ratios cannot be meaningful (100–108% and 60–65%). During the 5-year study period, there were no significant changes in the ratio of aneurysmal data between SKEN members and the HIRA (Tables 3-8).

Fig. 4.

Comparison between data collected from SKEN members and nationwide data from the Healthcare Bigdata Hub of the HIRA from 2013 to 2017. SKEN : The Society of Korean Endovascular Neurosurgeons, HIRA : the Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service.

In summary, the ratio of data from SKEN members to that from HIRA was about 50–70% for “DSA”, aneurysm (“coiling + PAO” and “stent or balloon”), and “AVM”, 70–90% for “IA thrombolysis for cerebral infarction” and “dural AVF or CCF”, and 45–60% for “tumor embolization”; these ratios did not change much over the 5-year study period. For “EC-PTA or stent (including CAS)” and “IC-PTA or stent”, the ratios were 50–70% and 65–85%, respectively, and the increasing trend was significant.

DISCUSSION

Clinical and autopsy studies suggest that intracranial aneurysms have a frequency of 1–8% [9], and that the incidence of subarachnoid hemorrhage due to ruptured aneurysms ranges from 6 to 8 people per 100,000 in western populations [5]. In the 1960s, McKissock et al. [6-8] were the first to report some controlled trials into the conservative and surgical treatment of ruptured aneurysms. They showed better outcomes using surgical management [6-8]. Since then, surgical techniques, instruments, and management methods have developed greatly, resulting in better outcomes. In 1991, electrolytically detachable coils (Guglielmi detachable coils; Boston scientific/Target Therapeutics, Freemont, CA, USA) were introduced to treat ruptured aneurysms using an endovascular approach. They were approved by United States Food and Drugs Administration (FDA) in 1995 [4]. Since then, endovascular coiling has widely been used to treat ruptured and unruptured aneurysms [1,2,15]. In particular, the serial trial known as the International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial, which was carried out from 2002 to 2015, proved the efficacy and safety of endovascular coiling methods [11-14]. With these successful trials, endovascular coiling could be recommended in the 2012 guidelines as a first option to treat patients with ruptured aneurysms judged to be technically amenable to both endovascular coiling and neurosurgical clipping [3]. In unruptured aneurysms, endovascular coiling is associated with lower procedural morbidity and mortality than surgical clipping in selected cases, and it is recommended at Class IIa with Level of Evidence B [18].

In South Korea, endovascular treatment research meetings began in 1994. In particular, two meetings were started by neurosurgeons and neuroradiologists, respectively. Each meeting then developed into a society : the SKEN, as well as the Korean Society of Interventional Neuroradiology (KSIN). At first, endovascular treatments were mainly performed by neuroradiologists. However, many vascular neurosurgeons eventually became interested and involved in endovascular treatment. Recently, endovascular treatment has been performed by neurosurgeons, neuroradiology doctors, or both, and the specific situations vary among hospitals.

According to data collected from SKEN members over 5 years from 2013 to 2017, the number of endovascular treatments performed collaboratively by SKEN members continuously increased over the period. Big cities such as Gyeonggi-do, Seoul, and Busan led this, but the phenomenon was observed nationwide. Among the endovascular treatments, conventional cerebral angiography was the most common, followed by cerebral aneurysmal coiling, endovascular treatments for ischemic stroke, and finally endovascular treatments for vascular malformation and tumor embolization. With the number of hospitals participating in data collection increasing year by year, it was natural that the total number of endovascular treatments performed would increase (Fig. 3). However, the rate of increase in endovascular treatments was higher than that participating hospitals; even when each category was analyzed separately, the rate of increase was higher in all categories of endovascular treatment than in the number of participating hospitals, except for the categories of “EC-PTA or stent(the rest of CAS)”, and “AVM” (Table 2). In several categories, the rate showed an increase of more than 50%, and in the “IA thrombolysis for cerebral infarction” category it showed an increase of more than 200% (Table 3). This shows that the number of endovascular treatments performed by SKEN members has increased, although this may have been due to the increase in hospital participation in some cases.

According to data collected from SKEN members, the “EC-PTA or stent(the rest of CAS)” category likely showed a lower rate of increase because this category lies outside the traditional remit of neurosurgery, and the absolute case number of such procedures was small. Authors expect that there will be little future change in this category of “EC-PTA or stent”. In the category of “AVM”, it is likely that trial known as “A Randomized trial of Unruptured Brain Arteriovenous Malformations” (ARUBA) released in 2014 was the cause of the lower rate of increase. In the ARUBA trial, medical management alone was superior to medical management with interventional therapy in the prevention of death or stroke in patients with unruptured brain AVMs [10]. Therefore, endovascular treatment for unruptured AVM was probably reduced. Unless other studies contradict the results of the ARUBA trail, there may be no change in the rate of increase in the “AVM” category. In the category of aneurysms, there was a higher rate of increase in the number of unruptured aneurysm than in the number of ruptured aneurysms, perhaps because diagnostic tools such as brain computed tomography angiography or magnetic resonance angiography have been developed, or because health screening has been applied nationwide.

According to national data from HIRA from 2013 to 2017, the number of endovascular treatments continuously increased over the 5-year period and were the highest in Seoul, followed by Gyeonggi-do and Busan, which is slightly different from the trend for SKEN data, according to which endovascular treatments were most common in Gyeonggi-do (Tables 3-8). During the study period, the rate of increase in endovascular treatments exceeded 50% in “DSA”, aneurysm (“coiling + PAO” and “stent or balloon”) and “IA thrombolysis for cerebral infarction”, was about 40% in “dural AVF or CCF” and “tumor embolization”, and was about 15% in “AVM”, which were similar to the results from SKEN data (Table 3). In contrast, the rate of increase was about 30% in “EC-PTA or stent (including CAS)” and “IC-PTA or stent”, which was different from the results from SKEN data, according to which the rate of increase was about 70% (Table 3). These results are consistent with the following analysis from a different point of view. Compared with the national data collected from HIRA, there were no significant changes in the ratio of data from SKEN members to data from HIRA in “DSA”, aneurysm (“coiling + PAO” and “stent or balloon”), “IA thrombolysis for cerebral infarction”, “AVM”, “dural AVF or CCF” and “tumor embolization”, however, an increase in the ratio was noted for “EC-PTA or stent (including CAS)” and “IC-PTA or stent” (Table 3).

The categories of “DSA” and aneurysm (“coiling” + “PAO” and “stent or balloon”) showed a 50–60% ratio for data from SKEN members and from HIRA and “IA thrombolysis for cerebral infarction” showed a 70–80% ratio, which did not change significantly and the rates of increase exceeded 50% during the 5-year study period (Table 3). The reasons might be as follows. Diseases belonging to these categories are representative ones that require endovascular treatment and are quite common, so many of these categories have already been performed by vascular neurosurgeons since 2013. Therefore, this ratio is expected to proceed in a similar trend into the future. And in the category of aneurysmal treatments, the ratio in “coiling” was more than 100%, while in the “stent or balloon” it was 60–65%. The number of aneurysmal treatments involving SKEN members was counted as the number of aneurysms, while the number in the HIRA was counted as the number of patients. Therefore, it was not possible to directly compare the two data sets. However, assuming that multiple aneurysms occur in 25% of cases, SKEN members likely participated in the treatment of more than 50% of aneurysms. In addition, even though the ratio itself was meaningless, there were no significant changes in the ratio of aneurysmal data between SKEN members and the HIRA over the 5-year study period, which may indicate that the data collected by the SKEN were quite reliable. In the category of “IA thrombolysis for cerebral infarction”, the rates of increase was above 200%, which was from that the treatment performance improved greatly due to the rapid development of treatment technology in recent years (Table 3). Therefore, the ratio of data from SKEN members to those from HIRA will be similar, but the total number will continue to increase.

“AVM” showed a 60–75% ratio, which did not change significantly during the study period. The rate of increase was about 15–25% during the study period, which was assumed to remain unchanged per the ARUBA trial, as mentioned above. The categories “dural AVF or CCF” and “tumor embolization” showed 75–95% and 40–60% ratios, which did not change significantly over the 5-year study period. The rate of increase was about 40–50% and 36–40%, respectively. Although these categories are not common, they are likely of interest to vascular neurosurgeons. The categories “EC-PTA or stent (including CAS)” and “IC-PTA or stent” showed 50– 70% and 65–85% ratios, respectively, and the difference in the rate of increase between SKEN members and HIRA was found to be 30–70%. These ratios seem to change from conventional surgical (in the case of “EC-PTA or stent [including CAS])” or medical (in the case of “IC-PTA or stent”) treatment to endovascular treatment, possibly led by vascular neurosurgeons (SKEN members).

In 1997, Veith [19], the President of the Society for Vascular Surgery, delivered the Presidential address in celebration of the 50th anniversary of the foundation of the Society. In that speech, he mentioned the threats to the specialized field of vascular surgery, emphasizing that advances in technology have allowed less-invasive, more cost-effective treatments, and that fiscal policy has encouraged it. This has increased the possibility that vascular surgery will become extinct. The less-invasive treatments of vascular disease he mentioned were endovascular treatments such as catheter-guidewire-imaging techniques involving catheters, balloons, atherectomy devices, stents, stented grafts, etc. He thought these were threats to the vascular surgeons because they confer similar or better results to open surgical treatments, and because they can be performed by non-surgical interventional specialists with training in radiology or cardiology [19]. For this reason, he argued that vascular surgeons must learn and practice endovascular treatment skills, and that, if they do not, they will be culled.

This was the situation in the US vascular surgery (not vascular neurosurgery) around 1997, and it is surprisingly similar to the situation of vascular neurosurgery in South Korea since 1994. At that time, endovascular treatment began in South Korea, but no one could be sure about the potential of the treatment for development. Fortunately, our forerunners had foresight and tried to adapt to these changes in the environment. Since 1994, they have established a research meeting and developed it into a society (SKEN) to continue and expand the role of vascular neurosurgeons. Of course, this development process produced many difficulties. While conventional open surgery was already established, endovascular treatment was a field in which results had to be made: there were many trials and errors, and it was difficult to be recognized by the Korean Neurosurgical Society. Furthermore, there were many conflicts with neuroradiologists, who had already taken an important positions in the field of endovascular treatment. Despite these difficulties, our forerunners did not stop their efforts. As the result, a substantial proportion of endovascular treatment in South Korea is now carried out by vascular neurosurgeons, as shown above. The SKEN, which has grown in quantity and quality, still makes such efforts and will continue to do so.

Limitations of the study

The data from the present study were collected from vascular neurosurgeons across the country over 5 years, with 77–100 hospitals involved (Table 9). However, this number does not include all hospitals with vascular neurosurgeons. In other words, the data in this study reflect only a subsection of all vascular neurosurgeons in South Korea. As mentioned earlier, aneurysm cases collected by the SKEN were based on the number of treated aneurysms, while the cases in the HIRA were based on the number of patients. Therefore, it was not possible to directly compare them. If comparisons were made using the same criteria, more accurate results could be obtained.

Table 9.

The list of the hospitals participated in the 2018 survey

| Hospital | Regions |

|---|---|

| Gachon University Gill Medical Center | Incheon |

| Catholic Kwandong University International 乳 Mary's Hospital | Incheon |

| The Catholic University of Korea Daejeon St. Mary's Hospital | Daejeon |

| The Catholic University of Korea Bucheon St. Mary's Hospital | Gyeonggi-do |

| The Catholic University of Korea Seoul St. Mary's Hospital | Seoul |

| The Catholic University of Korea St. Vincent's Hospital | Gyeonggi-do |

| The Catholic University of Korea Uijeongbu St. Mary's Hospital | Gyeonggi-do |

| The Catholic University of Korea Incheon St. Mary's Hospital | Incheon |

| Kyung Hee University Hospital at Gangdong | Seoul |

| Ulsan University Gangneung Asan Hospital | Gangwon-do |

| Kangwon National University Hospital | Gangwon-do |

| Konkuk University Hospital | Chungcheongbuk-do |

| Konyang University Hospital | Daejeon |

| Gumdan Top General Hospital | Incheon |

| Kyungpook National University Hospital | Daegu |

| Gyeongsang National University Hospital | Gyeongsangnam-do |

| Kyunghee National University Hospital | Seoul |

| Kyunghee University Medical Center E&C Jungang General Hospital | Gyeongsangnam-do |

| Keimyung University Dongsan Medical Center | Daegu |

| Korea University Ansan Hospital | Gyeonggi-do |

| Kosin University Gospel Hospital | Busan |

| National Medical Center | Seoul |

| Bongseng Memorial Hospital | Busan |

| Namyangju Hanyang General Hospital | Gyeonggi-do |

| New Korea Hospital | Gyeonggi-do |

| Dankook University Hospital | Chungcheongnam-do |

| Daegu Catholic University Medical Center | Daegu |

| Daegu Fatima Hospital | Daegu |

| Sun Medical Center | Daejeon |

| Daejeon Hankook Hospital | Daejeon |

| Dongkang Medical Center | Ulsan |

| Dongguk University Gyeongju Hospital | Gyeongsangbuk-do |

| Dongguk University Ilsan Hospital | Gyeonggi |

| Donggunsan General Hospital | Jeollabuk-do |

| Dongrae-Bongseng Hospital | Busan |

| Dong-A University Hospital | Busan |

| Dong-Eui Medical Center | Busan |

| Mediplex Sejong Hospital | Gyeonggi-do |

| Myongji Hospital | Gyeonggi-do |

| Myongji St. Mary's Hospital | Seoul |

| Pusan National University Hospital | Busan |

| Seoul National University Bundang Hospital | Gyeonggi-do |

| Bundang Jesaeng Hospital | Gyeonggi-do |

| Seodaegu Hospital | Daegu |

| Ulsan University Asan Medical Center | Seoul |

| Seoul Medical Center | Seoul |

| SMG-SNU Boramae Medical Center | Seoul |

| Kangbuk Samsung Hospital | Seoul |

| Sungkyunkwan University Samsung Changwon Hospital | Gyeongsangnam-do |

| Pohang Semyoung Christian Hospital | Gyeongsangbuk-do |

| Soon Chun Hyang University Hospital Gumi | Gyeongsangbuk-do |

| Soon Chun Hyang University Hospital Bucheon | Gyeonggi-do |

| Soon Chun Hyang University Hospital Seoul | Seoul |

| Soon Chun Hyang University Hospital Cheonan | Chungcheongnam-do |

| Asan Chungmu Hospital | Chungcheongnam-do |

| Ajou University Hospital | Gyeonggi-do |

| Andong Medical Group Hospital | Gyeongsangbuk-do |

| Andong Sungso Hospital | Gyeongsangbuk-do |

| Pohang Stroke and Spine Hospital | Gyeongsangbuk-do |

| Yonsei University Gangnam Severance Hospital | Seoul |

| Yonsei University Severance Hospital | Seoul |

| Wonju Severance Christian Hospital | Gangwon-do |

| Yeungnam University Medical Center | Daegu |

| Presbyterian Medical Center | Jeollabuk-do |

| On Hospital | Busan |

| Ulsan University Ulsan Hospital | Ulsan |

| Wonkwang University Hospital | Jeollabuk-do |

| Sun Medical Center | Daejeon |

| Eulji University Nowon Eulji Medical Center | Seoul |

| Eulji University Daejeon Eulji Medical Center | Daejeon |

| Ewha Womans University Mokdong Hospital | Seoul |

| Hallym Hospital | Incheon |

| Inje University Seoul Paik Hospital | Seoul |

| Inje University Haeundae Paik Hospital | Busan |

| Inha University Hospital | Incheon |

| Chonnam National University Hospital | Gwangju |

| Chonbuk National University Hospital | Jeollabuk-do |

| Jeju National University Hospital | Jeju |

| Cheju Halla General Hospital | Jeju |

| Chosun University Hospital | Gwangju |

| Chung-Ang University Hospital | Seoul |

| VHS Medical Center | Seoul |

| CHA University Kumi Medical Center | Gyeongsangbuk-do |

| CHA University Bundang Medical Center | Gyeonggi-do |

| Chamjoeun Hospital | Gyeonggi-do |

| Cheonan Chungmu Hospital | Chungcheongnam-do |

| Cheongju St. Mary's Hospital | Chungcheongbuk-do |

| Hankook General Hospital | Chungcheongbuk-do |

| Chungnam National University Hospital | Daejeon |

| Pohang St. Mary's Hospital | Gyeongsangbuk-do |

| Hallym University Kangnam Sacred Heart Hospital | Seoul |

| Hallym University Kangdong Sacred Heart Hospital | Seoul |

| Hallym University Dongtan Sacred Heart Hospital | Gyeonggi-do |

| Hallym University Chuncheon Sacred Heart Hospital | Gangwon-do |

| Hallym University Medical Center | Gyeonggi-di |

| Hallym University Hangang Sacred Heart Hospital | Seoul |

| Hanyang University Guri Hospital | Gyeonggi-do |

| Hanyang University Seoul Hospital | Seoul |

| Hongik Hospital | Seoul |

| Hyosung Hospital | Chungcheongbuk-do |

CONCLUSION

The SKEN members have been responsible for the major role of endovascular treatments in South Korea for the recent 5 years. This was achieved through the perseverance of senior members who started out in the midst of hardship, the establishment of standards for the training/certification of endovascular neurosurgery, and the enthusiasm of current SKEN members who followed. To provide better treatment to patients, we will have to make further progress in SKEN.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Bio Industrial Strategic Technology Development Program (20001234) funded by the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MOTIE, Korea) and Soonchunhyang University Research Fund.

Authors would like to express deep gratitude to the hospitals and SKEN members who responded to the survey.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

INFORMED CONSENT

This type of study does not require informed consent.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization : BTK

Data curation : TGK, OKK, YSS, JHS, JSK, BTK

Formal analysis : TGK

Funding acquisition : TGK, BTK

Methodology : TGK, BTK

Project administration : BTK

Visualization : TGK

Writing - original draft : TGK

Writing - review & editing : BTK

References

- 1.Brilstra EH, Rinkel GJ, van der Graaf Y, van Rooij WJ, Algra A. Treatment of intracranial aneurysms by embolization with coils: a systematic review. Stroke. 1999;30:470–476. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.2.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Byrne JV, Molyneux AJ, Brennan RP, Renowden SA. Embolisation of recently ruptured intracranial aneurysms. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1995;59:616–620. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.59.6.616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Connolly ES, Jr, Rabinstein AA, Carhuapoma JR, Derdeyn CP, Dion J, Higashida RT, et al. Guidelines for the management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2012;43:1711–1737. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e3182587839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guglielmi G, Viñuela F, Dion J, Duckwiler G. Electrothrombosis of saccular aneurysms via endovascular approach. Part 2: preliminary clinical experience. J Neurosurg. 1991;75:8–14. doi: 10.3171/jns.1991.75.1.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Linn FH, Rinkel GJ, Algra A, van Gijn J. Incidence of subarachnoid hemorrhage: role of region, year, and rate of computed tomography: a metaanalysis. Stroke. 1996;27:625–629. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.4.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKissock W, Richardson A, Walsh L. "Posterior-communicating" aneurysms: a controlled trial of the conservative and surgical treatment of ruptured aneurysms of the internal carotid artery at or near the point of origin of the posterior communicating artery. The Lancet. 1960;275:1203–1206. [Google Scholar]

- 7.McKissock W, Richardson A, Walsh L. Middle-cerebral aneurysms further results in the controlled trial of conservative and surgical treatment of ruptured intracranial aneurysms. The Lancet. 1962;280:417–421. [Google Scholar]

- 8.McKissock W, Richardson A, Walsh L. Anterior communicating aneurysms: a trial of conservative and surgical treatment. Lancet. 1965;1:874–876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meyer FB, Morita A, Puumala MR, Nichols DA. Medical and surgical management of intracranial aneurysms. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:153–172. doi: 10.4065/70.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohr JP, Parides MK, Stapf C, Moquete E, Moy CS, Overbey JR, et al. Medical management with or without interventional therapy for unruptured brain arteriovenous malformations (ARUBA): a multicentre, nonblinded, randomised trial. Lancet. 2014;383:614–621. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62302-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Molyneux A, Kerr R, Stratton I, Sandercock P, Clarke M, Shrimpton J, et al. International subarachnoid aneurysm trial (ISAT) of neurosurgical clipping versus endovascular coiling in 2143 patients with ruptured intracranial aneurysms: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;360:1267–1274. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11314-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Molyneux AJ, Birks J, Clarke A, Sneade M, Kerr RS. The durability of endovascular coiling versus neurosurgical clipping of ruptured cerebral aneurysms: 18 year follow-up of the UK cohort of the international subarachnoid aneurysm trial (ISAT) Lancet. 2015;385:691–697. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60975-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Molyneux AJ, Kerr RS, Birks J, Ramzi N, Yarnold J, Sneade M, et al. Risk of recurrent subarachnoid haemorrhage, death, or dependence and standardised mortality ratios after clipping or coiling of an intracranial aneurysm in the international subarachnoid aneurysm trial (ISAT): long-term follow-up. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:427–433. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70080-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Molyneux AJ, Kerr RS, Yu LM, Clarke M, Sneade M, Yarnold JA, et al. International subarachnoid aneurysm trial (ISAT) of neurosurgical clipping versus endovascular coiling in 2143 patients with ruptured intracranial aneurysms: a randomised comparison of effects on survival, dependency, seizures, rebleeding, subgroups, and aneurysm occlusion. Lancet. 2005;366:809–817. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67214-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nichols DA. Endovascular treatment of the acutely ruptured intracranial aneurysm. J Neurosurg. 1993;79:1–2. doi: 10.3171/jns.1993.79.1.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park HR, Park SQ, Kim JH, Hwang JC, Lee GS, Chang JC. Geographic analysis of neurosurgery workforce in Korea. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2018;61:105–113. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2017.0303.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shin DS, Park SQ, Kang HS, Yoon SM, Cho JH, Lim DJ, et al. Standards for endovascular neurosurgical training and certification of the society of korean endovascular neurosurgeons 2013. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2014;55:117–124. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2014.55.3.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson BG, Brown RD, Jr, Amin-Hanjani S, Broderick JP, Cockroft KM, Connolly ES, Jr, et al. Guidelines for the management of patients with unruptured intracranial aneurysms: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2015;46:2368–2400. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Veith FJ. Presidential address: Charles Darwin and vascular surgery. J Vasc Surg. 1997;25:8–18. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(97)70316-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]