Abstract

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) is associated with increased chemokines, cytokines, and growth factors in the diseased kidney. We found that both isoforms of IL-1, IL-1α and IL-1β, were upregulated in ADPKD tissues. Here, we used a unique murine ADPKD model with selective deletion of polycystin-1 (pkd1) in the kidney (KPKD1) to study the role of IL-1 signaling in ADPKD progression. In KPKD mice, genetic deletion of the IL-1 receptor [IL-1 receptor (IL-1R) knockout (KO)] prolongs survival and attenuates cyst volume. Compared with IL-1R wild-type KPKD1 kidneys, IL-1R KO KPKD1 kidneys have upregulated TNF-α gene expression, with consequent elevations in markers for TNF-dependent regulated necrosis. We further observed that regulated necrosis was increased in ADPKD tissues from both humans and mice. To confirm that enhanced necroptosis is protective in ADPKD, we treated KPKD1 mice with an inhibitor of regulated necrosis (Nec-1). Regulated necrosis suppression augments kidney weights, suggesting that regulated necrosis is required to limit kidney growth in ADPKD. Thus, IL-1R activation drives ADPKD progression by paradoxically limiting regulated necrosis.

Keywords: autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, interleukin-1, necroptosis, tumor necrosis factor-α

INTRODUCTION

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) is the most common inherited kidney disease and is a major cause of end-stage kidney disease worldwide (27). ADPKD is caused by polycystin-1 (PKD1) or polycystin-2 (PKD2) mutations, but the mechanisms through which mutations in PKD genes lead to the neoplastic cyst growth in kidneys are still not fully understood. The morphology of ADPKD in the kidney includes cyst formation in all regions of the nephron and subsequently vascular-interstitial inflammation, fibrosis, and even cyst hemorrhage (10). The expansion of cysts is attributed to increased tubular epithelial cell proliferation (15).

Beyond the well-documented intracellular signaling that contributes to the onset of the disease (11, 33), the inflammatory microenvironment in the kidney, including recruitment of immune cells and generation of inflammatory cytokines, plays an important role in PKD progression (5, 24). The IL-1 isoforms, IL-1α and IL-1β, are the prototypical cytokines from the innate immune system (8b). Both are produced primarily by stimulated monocytes and macrophages but to a lesser degree by several other cell types, including neutrophils and epithelial and endothelial cells (8). As early as 1997, Merta et al. (23) reported that in patients with ADPKD, urinary excretion of the IL-1 receptor (IL-1R) antagonist is decreased. However, to our knowledge, the effects of IL-1 signaling on PKD progression have not been directly investigated. Here, we used a unique model with deletion of pkd1 restricted to the kidney to establish that activating IL-1R worsens the severity of ADPKD, at least in part by attenuating regulated necrosis in the kidney.

METHODS

Surgical specimen collection.

Polycystic kidneys were surgical specimens from recipients of kidney transplantation. Patients were diagnosed with ADPKD according to the following criteria (37): 1) family history of ADPKD or 2) large kidneys with multiple bilateral cysts on ultrasonography or computed tomography scanning. Control kidney tissues were from healthy parts of renal cell carcinoma surgical specimens. The procedures for the use of human kidneys and the consent form were approved by the Second Military Medical University Institutional Review Board and were administered by the staff at the institution where the nephrectomy was performed and then signed by the principal investigator (C. Mei).

Animals.

IL-1R1−/− [IL-1R1 knockout (KO)] (B6.129S7-Il1r1tm1Glm/J) mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. Ksp1.3/Cre, KspCre mice were also obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. Pkd1flox/flox mice were generously provided by Prof. Somlo (Section of Nephrology, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT). KPKD1 (pkd1 f/f; KspCre+) mice and IL-1R KO KPKD1 (IL-1R mutant/mutant; pkd1 f/f; KspCre+) mice were generated via intercrosses of the KPKD1 and IL-1R1 KO lines. All animal experiments were approved by the Durham Veterans Affairs Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Genotyping of the mice.

Genotyping was performed by ear DNA PCR analysis. Ear DNA was isolated using a Mouse Direct PCR Kit. The primer sequences used for genotyping were as follows: IL-1R, wild-type (WT) forward 5ʹ-GGTGCAACTTCATAGAGAGATGA-3ʹ, mutant forward 5ʹ-CTCGTGCTTTACGGTATCGC-3ʹ, and common reverse 5ʹ-TTCTGTGCATGCTGGAAAAC-3ʹ; KspCre, forward: 5ʹ-GCGGTCTGGCAGTAAAAACTATC-3ʹ and reverse 5ʹ-GTGAAACAGCATTGCTGTCACTT-3ʹ; and PKD1, forward 5ʹ-CCTGCCTTGCTCTACTTTCC-3ʹ and reverse 5ʹ-AGGGCTTTTCTTGCTGGTCT-3ʹ. PCR products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Interruption of regulated necrosis with Nec-1 in mice.

Mice were treated with 0.6 mg·kg−1·day−1 Nec-1 from day 1 after birth for a consecutive 6 days (42). The control group was treated with vehicle for the same period of time. Mice were euthanized at day 7 after birth.

Primary cell culture.

Using previously described methods (12, 38), primary tubular epithelial cells from control and KPKD1 mice (day 8 after birth) were isolated and cultured under sterile conditions. Tubular fragments were seeded onto collagen-coated cell culture dishes and left unstirred for 48 h at 37°C, after which the culture media were changed for the first time. Media were then replaced every 2 days. After confluent monolayers formed, cells were harvested and analyzed.

Morphological and immunohistochemical analyses.

Kidneys were fixed in 10% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Paraffin sections (4 μm thick) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and subjected to immunohistochemical staining with anti-Ki-67. Cystic indexes were quantified using Adobe Photoshop CC 2017. Human kidney paraffin-embedded sections were subjected to immunohistochemical staining with anti-phospho-mixed lineage kinase domain-like pseudokinase (MLKL).

RNA extraction and real-time PCR examination.

mRNA was isolated with an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Kidney pieces of the recommended size were homogenized in RLT buffer with 0.01% β-mercaptoethanol. The mRNA concentration in each sample was determined by Nanodrop (ThermoFisher). cDNA was synthesized with a High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (catalog no. 4368814, Applied Biosystemshe ) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Gene expression levels of the corresponding genes were determined by RT-PCR on a QuantStudio 3 machine (ThermoFisher) using TaqMan and SYBR primers (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

SYBR primers used for PCR

| Gene Name | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | 5′-GTCTTCACCACCATGGAGAAGG-3′ | 5′-CTAAGCAGTTGGTGGTGCAGGA-3′ |

| TNF-α | 5′-TAGCCCACGTCGTAGCAAAC-3′ | 5′-ACAAGGTACAACCCATCGGC-3′ |

| RIP1 | 5′-GCCTTCGTTCAGCTTGTGTC-3′ | 5′-ACAGTCCATGAAGCGGGAAG-3′ |

| RIP3 | 5′-GGACATCTTCTGACCCCGTG-3′ | 5′-GTCATTGGATTCGGTGGGGT-3′ |

| MLKL | 5′-TCTGGGAAATTGCCACTGGA-3′ | 5′-CCCACTGGTTCCTGCTTCTT-3′ |

| Caspase-3 | 5′-TGTCATCTCGCTCTGGTACG-3′ | 5′-AAATGACCCCTTCATCACCA-3′ |

| Caspase-8 | 5′-CTCCGAAAAATGAAGGACAGA-3′ | 5′-CGTGGGATAGGATACAGCAGA-3′ |

RIP, receptor-interacting protein; MLKL, mixed lineage kinase domain-like pseudokinase.

Table 2.

Taqman primers used for PCR

| Gene Name | Accession Number/Catalog Number |

|---|---|

| IL-1α | Mm00439620_m1 |

| IL-1β | Mm00434228_m1 |

| IL-6 | Mm01210732_g1 |

| IL-1R | Mm00434235_m1 |

| Ccl2 | Mm00441242_m1 |

| TGF-β | Mm01178820_m1 |

| Arg1 | Mm00475988_m1 |

| ccl3 | Mm00441258_m1 |

IL-1R, IL-1 receptor; Ccl, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β; Arg1, arginase 1.

Western blot analyses.

Cell or tissue lysates were prepared in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris·HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 2% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, and phosphatase and protease inhibitors) and clarified by centrifugation. Equal amounts of protein were run on SDS-polyacrylamide gels under reducing conditions, transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, blocked in 3% BSA, and incubated with various primary antibodies. The appropriate secondary antibodies were used before development with enhanced chemiluminescence reagent. The primary antibodies used were as follows: phospho-receptor-interacting protein 3 (RIP3; mouse, catalog no. ab195117, Abcam), phospho-MLKL (mouse, catalog no. ab196436, Abcam), phospho-RIP3 (human, catalog no. CST 93654, Cell Signaling Technology), TNF-α (mouse, catalog no. CST 11948s, Cell Signaling Technology), and phospho-MLKL (human, catalog no. ab187091, Abcam). Anti-GAPDH (catalog no. CST 5174, Cell Signaling Technology) served as a loading control.

Statistical analyses.

All data examined are presented as means ± SE. Comparisons between two groups were conducted using a two-tailed t-test when the data were normally distributed. Survival analyses were performed using the Kaplan-Meier log rank χ2-test. P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were carried out using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software), and all graphs were generated with the same software.

RESULTS

IL-1α and IL-1β upregulation in ADPKD tissue.

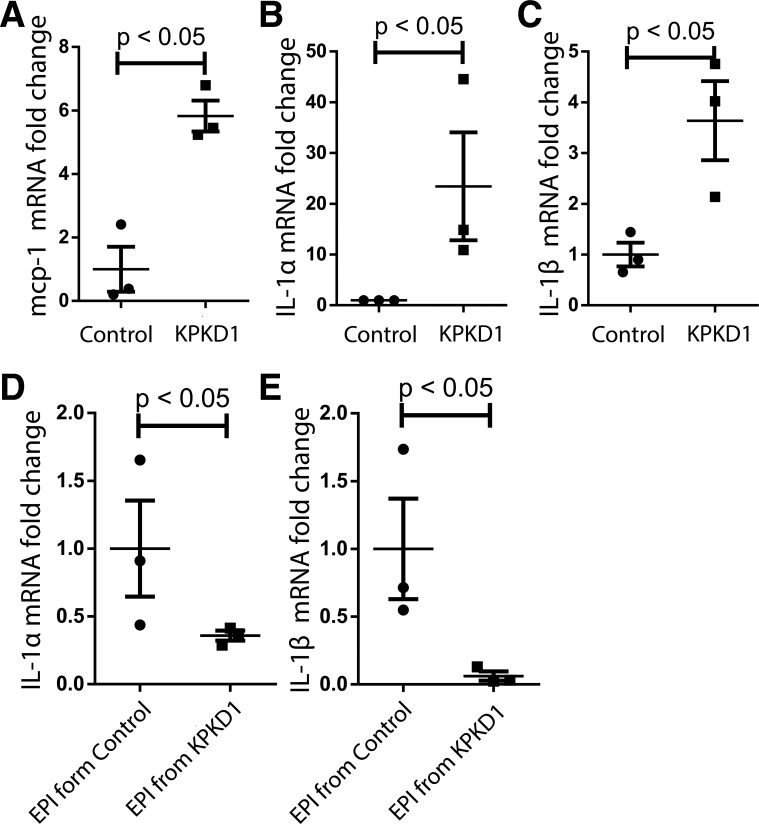

ADPKD is associated with increased inflammation, both within the kidney and systemically (22, 24). To examine the role of inflammation in ADPKD, we used a mouse model in which pkd1 gene deletion is restricted to the kidney (Ksp1.3 Cre+ pkd1flox/flox; referred to here as “KPKD1”). We measured mRNA expression of the cytokine macrophage chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1, known to be important to PKD pathogenesis (6), and the prototypical macrophage cytokine IL-1 in KPKD1 kidneys. We found that MCP-1 and both isoforms of IL-1 were upregulated in ADPKD tissues (Fig. 1, A–C). However, when KPKD1 epithelial cells were isolated and cultured, IL-1α and IL-1β levels were downregulated (Fig. 1, D and E), indicating that the microenvironment in cystic kidneys drives IL-1 upregulation.

Fig. 1.

IL-1α and IL-1β upregulation in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease tissues. A−C: renal mRNA levels in control mice and mice with selective deletion of polycystin-1 in the kidney (KPKD1 mice) for macrophage chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1 (A), IL-1α (Β), and IL-1β (C). D and E: mRNA levels in primary kidney epithelial (EPI) cells from control mice and KPKD1 mice for IL-1α (D) and IL-1β (E).

IL-1R deficiency prolongs survival in KPKD mice.

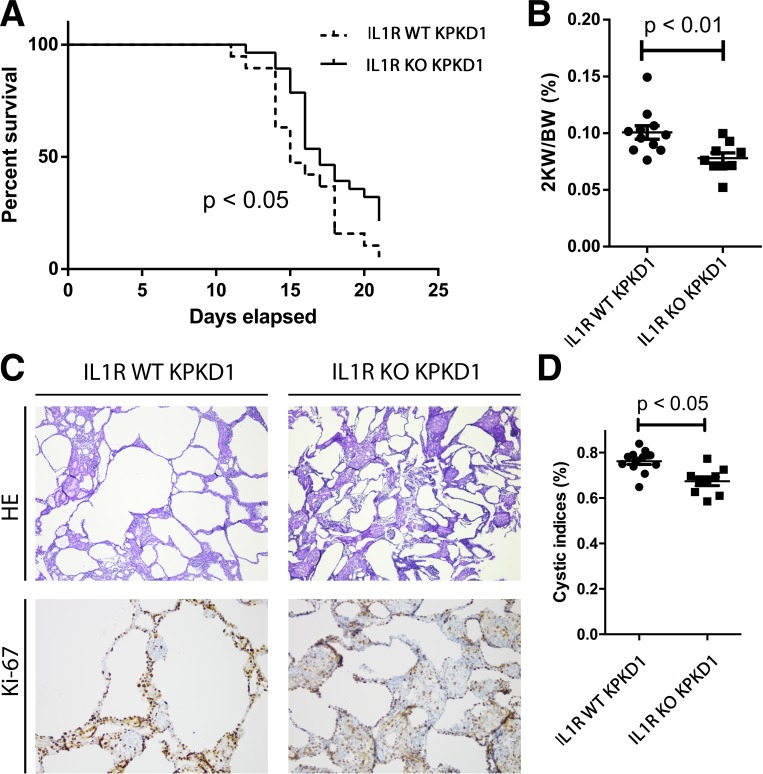

To directly test the role of IL-1 signaling in ADPKD progression, we established KPKD1 mice with genetic deletion of IL-1R (IL-1R KO KPKD1) and analyzed disease progression compared with KPD1 mice expressing normal IL-1R levels in all tissues (IL-1R WT KPKD1). The KPKD1 mouse model is a very aggressive model, with most mice dying before day 21 after birth (30). Compared with the IL-1R WT KPKD1 cohort, IL-1R KO KPKD1 animals had a mild prolongation in survival (Fig. 2A). We also measured kidney weight-to-body weight ratios at day 8 after birth. IL-1R KO KPKD1 mice had reduced kidney weight-to-body weight ratios and lower cystic indexes compared with IL-1R WT control mice (Fig. 2, B–D).

Fig. 2.

IL-1 receptor (IL-1R) deficiency ameliorates cyst progression in mice with selective deletion of polycystin-1 in the kidney (KPKD1 mice). A: median survival in IL-1R knockout (KO) KPKD1 mice was longer than in IL-1R wild-type (WT) KPKD1 mice (P < 0.05). B: kidney weight-to-body weight ratios (2KW/BW) in the IL-1R KO KPKD1 mouse group were lower compared with the IL-1R WT control group. C: representative images of kidneys from both groups. D: the cystic index was lower in the IL-1R KO KPKD1 group compared with the IL-1R WT KPKD1 group. HE, hematoxylin and eosin.

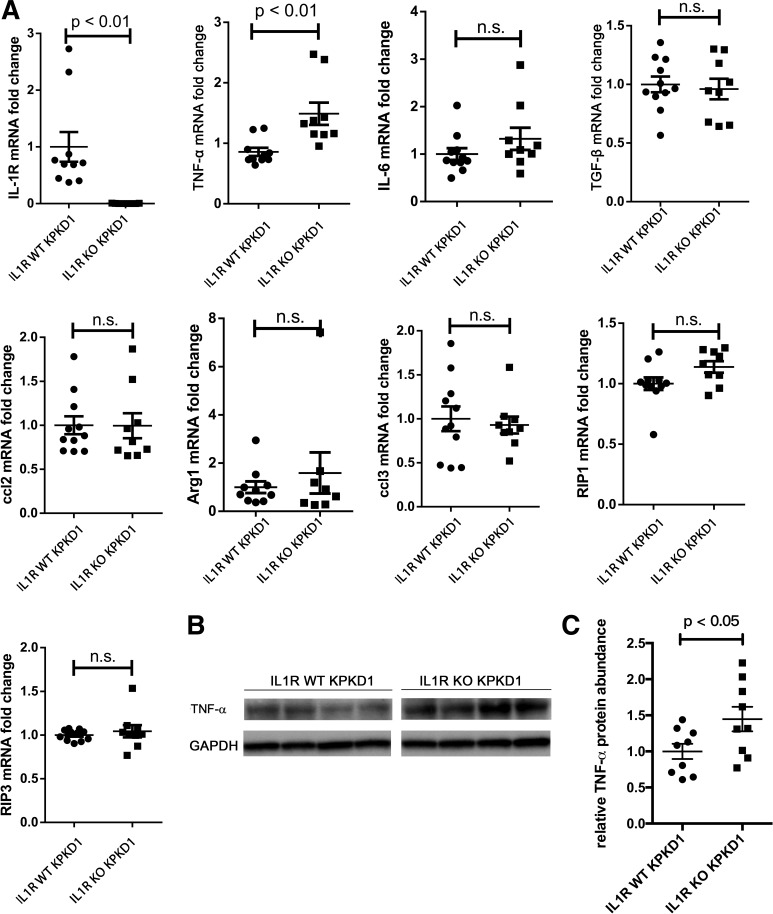

IL-1R deficiency associates with higher TNF-α levels in the KPKD1 kidney.

As IL-1 signaling is important in directing the innate immune response (1, 9, 34), we posited that IL-1R activation aggravates PKD progression via effects on inflammatory signals within the kidney. We therefore profiled the expression of several inflammatory cytokines within IL-1R WT and KO KPDK1 kidneys at day 8. Surprisingly, we could not detect any differences in gene expression for inflammatory cytokines, with the exception of TNF-α. TNF-α mRNA levels were significantly higher in the IL-1R KO cohort compared with the IL-1R WT control cohort (Fig. 3A). This finding was confirmed by quantitating TNF-α protein levels via Western blot analysis (Fig. 3, B and C). Thus, although IL-1R signaling is typically proinflammatory in most diseases, IL-1R activation in KPKD1 is associated with renal TNF-α suppression, as has been previously reported in certain contexts (8a).

Fig. 3.

IL-1 receptor (IL-1R) activation suppresses TNF-α expression and attenuates regulated necrosis. A: receptor-interacting protein (RIP)1, RIP3, and cytokine mRNA levels were quantitated in kidneys from IL-1R wild-type (WT) mice with selective deletion of polycystin-1 in the kidney and IL-1R knockout (KO) KPKD1 control mice. Compared with IL-1R WT KPKD1 kidneys, TNF-α protein was upregulated in IL-1R KO KPKD1 kidneys [typical Western blot bands (B) and protein abundance analysis (C)]. n.s., not significant.

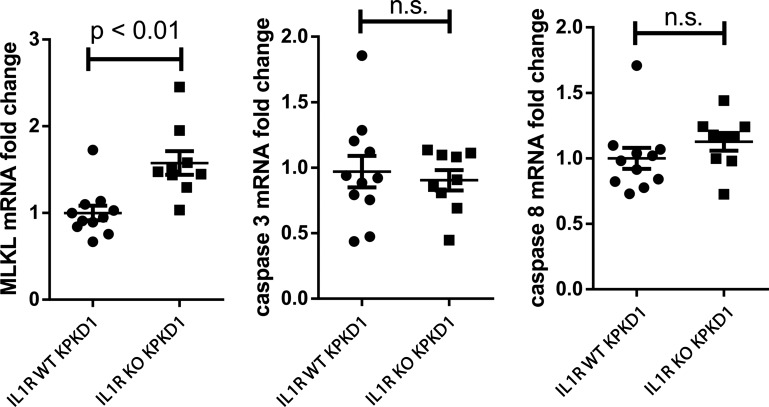

IL-1R1 activation suppresses regulated necrosis in KPKD.

We then explored a possible mechanism through which TNF-α could afford protection in our model. As TNF-α is a classic inducer of both apoptosis and necroptosis (18, 20), we tested markers of apoptosis and regulated necrosis in our experimental animals. We found that mRNA levels for MLKL were increased in IL-1R KO PKD1 kidneys, indicating enhanced susceptibility to regulated necrosis (21), whereas markers of apoptosis, caspase-3 and caspase-8, were not (Fig. 4). Thus, by reducing the net survival of proliferating epithelial cells, enhanced regulated necrosis mediated via TNF-α could contribute to the amelioration in PKD1 seen with IL-1R deficiency.

Fig. 4.

IL-1 receptor type 1 (IL-1R1) stimulation suppresses regulated necrosis but not apoptosis with kidney-selective deletion of polycystin-1 (KPKD). Mixed lineage kinase domain-like pseudokinase (MLKL), caspase-3, and caspase-8 mRNA levels were quantitated in IL-1R wild-type (WT) and knockout (KO) KPKD1 kidneys. n.s., not significant.

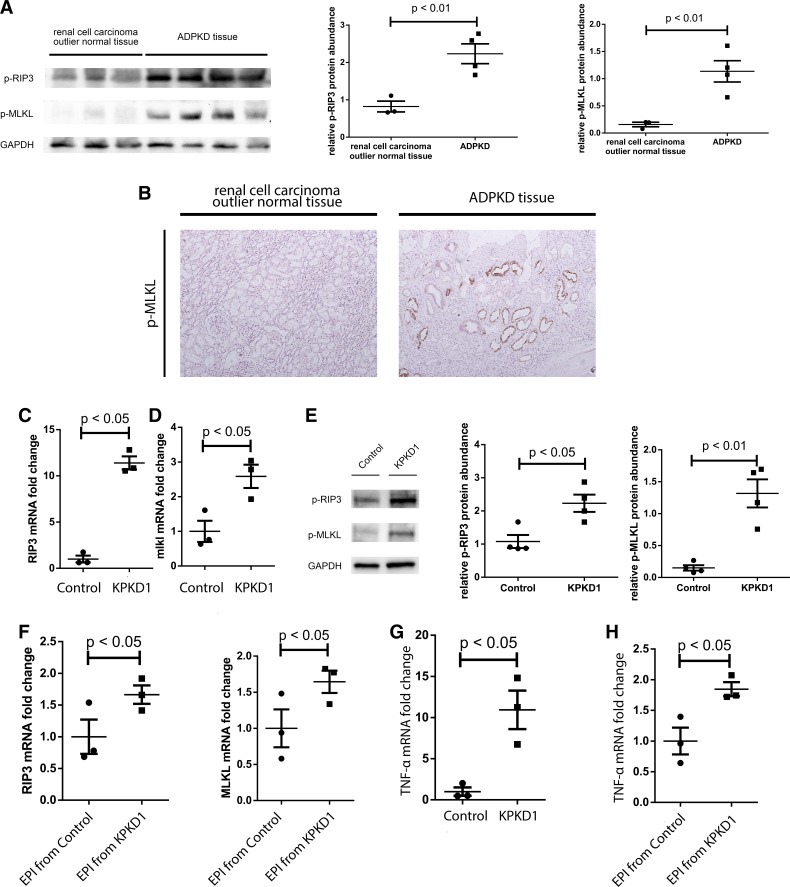

Regulated necrosis is compensatorily upregulated in multiple ADPKD tissues.

To understand if regulated necrosis is a relevant phenomenon in human ADPKD, we examined markers of regulated necrosis in human ADPKD tissues. To this end, we collected human ADPKD surgical specimens from recipients of kidney transplantation who had undergone native nephrectomy. Control kidney tissues were from healthy parts of renal cell carcinoma surgical specimens. Western blot analysis indicated that phosphorylation of RIP3 and MLKL was upregulated in human ADPKD tissue, consistent with increased necroptosis (Fig. 5A). Immunohistochemistry on a human ADPKD kidney specimen detected phospho-MLKL staining in tubular epithelial cells lining the cysts (Fig. 5B). This pattern recapitulated that which we saw in KPKD1 mice at day 8 after birth. Compared with non-PKD controls, mRNA levels of RIP3 and MLKL were upregulated in KPKD1 kidneys (Fig. 5, C and D), and phosphorylation levels of RIP3 and MLKL were also increased (Fig. 5E). In primary epithelial cells isolated from KPKD1 mice, RIP3 and MLKL mRNA levels were upregulated by only 1.5-fold compared with control mice (Fig. 5F) rather than >10- and >2-fold, respectively, seen in vivo, suggesting that the inflammatory milieu in vivo may drive TNF-α-dependent regulated necrosis in PKD. Indeed, we found that TNF-α mRNA levels were upregulated in KPKD1 tissues and primary KPDK1 tubular epithelial cells (Fig. 5, G and H).

Fig. 5.

Necroptosis is upregulated in multiple autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) tissues. A: phosphorylation of receptor-interacting protein 3 (RIP3) and mixed lineage kinase domain-like pseudokinase (MLKL) was upregulated in human ADPKD tissues by Western blot analysis. B: immunohistochemical stains detected phosphorylated (p-)MLKL in epithelial cells lining cysts in human ADPKD sections. C and D: mRNA levels of RIP3 (C) and MLKL (D) were increased in kidneys from mice with selective deletion of polycystin-1 (pkd1) in the kidney (KPKD1 mice). E: phosphorylation of RIP3 and MLKL was upregulated in KPKD1 kidneys. Typical Western blot bands and protein abundance analysis are shown. F: in primary epithelial (EPI) cells, pkd1 knockout (KO) induced ~1.5-fold RIP3 and MLKL mRNA upregulation. G and H: TNF-α mRNA levels were induced in KPKD1 tissues (G) and primary KPDK1 tubular epithelial cells (H).

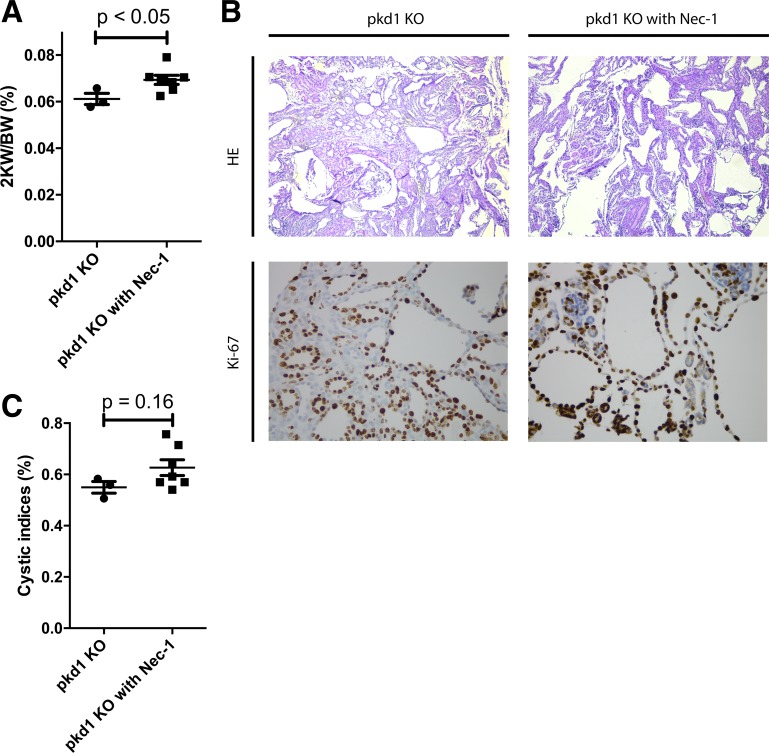

Blockade of regulated necrosis augments PKD kidney volume.

To directly assess whether regulated necrosis plays a role in PKD progression, we treated KPKD1 mice with an inhibitor of regulated necrosis (Nec-1) or vehicle and examined the severity of ADPKD at day 7 after birth. In Nec-1-treated animals, kidney weight-to-body weight ratios were significantly higher than in vehicle-treated control animals (Fig. 6A), and the cystic index trended higher in Nec-1-treated animals (Fig. 6, B and C). These data suggest that regulated necrosis plays a protective role in PKD by limiting cyst expansion.

Fig. 6.

Regulated necrosis limits kidney expansion in polycystin-1 (PKD1). A: kidney weight-to-body weight ratios (2KW/BW) were increased when regulated necrosis was blocked with Nec-1 in mice with selective deletion of pkd1 in the kidney (KPKD1 mice). B: typical images of kidneys from both groups. C: cystic indexes trended higher in KPKD1 mice with Nec-1 treatment. HE, hematoxylin abd eosin.

DISCUSSION

ADPKD, which is characterized by uncontrolled tubular epithelial cell proliferation, is both a genetic and inflammatory disease. Macrophages play a key role in influencing cyst expansion (6), and IL-1 is the prototypical macrophage cytokine. An observational study (23) in patients with ADPKD suggested that IL-1 signaling may be involved in disease pathogenesis, and we found that both isoforms of IL-1 were upregulated in murine PKD1 kidneys. We therefore interrogated the role of IL-1R signaling in ADPKD by comparing the severity of renal disease in KPKD1 mice harboring genetic deletion of IL-1R with IL-1R WT control mice. In our system, IL-1R deficiency yielded an attenuation in disease severity coupled with an increase in renal TNF-α expression and regulated necrosis. Further experiments established that regulated necrosis was upregulated in ADPKD and can limit kidney expansion in this context by counterbalancing increased epithelial cell proliferation. Thus, IL-1R activation may aggravate ADPKD, not by provoking inflammation but rather by suppressing TNF-α generation and consequent regulated necrosis.

TNF-α can directly stimulate cyst formation in ADPKD accruing from the pkd2 mutation (16). Nevertheless, in our more aggressive KPKD1 model, we identify here a potential counterregulatory mechanism through which TNF-α acting as a key mediator of regulated necrosis may limit overall kidney expansion (17). Thus, the effects of TNF-α in PKD progression may depend on the PKD mutation and consequent disease severity. Moreover, we deleted pkd1 primarily from the distal nephron, possibly bypassing the known injurious effects of TNF-α in the proximal tubule. The relationship between IL-1R signaling and TNF-α levels seems to be disease dependent. In previous studies (31, 41), we found that IL-1R activation induces TNF-α mRNA in the kidney after toxin-induced injury and during hypertension. We were therefore surprised to find that IL-1R activation blunts renal TNF-α expression in the ADPKD model, but there is precedent for this inverse relationship in the setting of tuberculosis infection (8a).

Although germline mutations in pkd1 and pkd2 genes are the dominant factors in determining the onset and severity of disease (7), several nongenetic factors may modulate disease progression and thus provide a potential opportunity for therapeutic intervention. These factors include alterations directly within renal tubular cells, such as cell polarity alternation (25), chemokine secretion (40), and metabolism (19), all of which interact with factors in the kidney’s inflammatory milieu such as macrophage recruitment and polarization (40), immune cell population activation (13), and oxidative stress (26). In our model, by altering the expression of IL-1R, we observed a modest improvement in survival. Although few studies in this field have measured survival as an outcome, we posit from the cystic index results that the role of IL-1R activation may contribute to the effects of macrophage infiltration on PKD progression (40) while playing a less prominent role in PKD than classically recognized cAMP (3) and mammalian target of rapamycinpathways (36).

Regulated necrosis, a term that includes both necroptosis and ferroptosis, represents a tubule-specific phenomenon that is influenced by the inflammatory milieu and has been widely studied in contexts other than PKD. For example, the sizes of malignant tumors are inversely related to the regulated necrosis markers RIP3 and MLKL (4, 14, 32, 35). In that way, cancer cells may achieve some resistance to the prodeath factors in the microenvironment. Indeed, we acknowledge this potential confounder in using human kidney tissues bordering renal cell carcinoma specimens as necroptosis controls. Cyst growth in ADPKD shares several attributes in common with cancer, including elevated protooncogene activation, elevated cell cycle activity, macrophage infiltration, and induction of cytokines, including TNF-α (2). Regulated necrosis may thus represent a common mechanism that limits the expansion of malignant tumors and PKD kidneys. Given that Nec-1 inhibits both ferroptosis and necroptosis, we cannot distinguish which of these forms of regulated necrosis is more central in controlling the progression of PKD. Indeed, as renal cell carcinoma can emerge from PKD tissues, and renal cell carcinomas are sensitive to ferroptosis (39), ferroptosis may well play a more critical role in PKD severity than necroptosis.

In summary, we found in an ADPKD model that IL-1R activation leads to augmented cystic indexes and kidney weight due in part to suppression of regulated necrosis. We posit that, uniquely in PKD, IL-1R stimulation limits regulated necrosis by suppressing TNF-α in the kidney. In that case, IL-1R activation aggravates PKD by mitigating rather than augmenting local inflammation with consequent reductions in tubular necrosis. The induction of regulated necrosis that we detect in multiple ADPKD models may therefore represent a protective counterbalance to increased epithelial cell proliferation. Thus, blunting IL-1R signaling and stimulating necroptosis or ferroptosis warrant further testing as novel therapeutic interventions in ADPKD. However, the application of IL-1R antagonists such as anakinra must be approached with caution in human patients with PKD given that the downstream effects of TNF-α on PKD progression appear to be context specific. Moreover, it is not certain that the paradoxical effects of IL-1R activation to suppress TNF-α generation in the murine cystic kidney would be recapitulated in human PKD.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK-118019 and HL-128355, United States Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development Grant BX-000893, American Heart Association Award 18TPA34170047, and China Scholarship Council Grant 201803170125.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

B.Y., C.M., and S.D.C. conceived and designed research; B.Y., L.F., J.R.P., X.L., and J.R. performed experiments; B.Y., L.F., J.R.P., X.L., and J.R. analyzed data; B.Y. and S.D.C. interpreted results of experiments; B.Y. prepared figures; B.Y. drafted manuscript; B.Y., C.M., and S.D.C. edited and revised manuscript; B.Y., L.F., J.R.P., X.L., C.M., and S.D.C. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anders HJ. Of inflammasomes and alarmins: IL-1β and IL-1α in kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 2564–2575, 2016. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016020177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antignac C, Calvet JP, Germino GG, Grantham JJ, Guay-Woodford LM, Harris PC, Hildebrandt F, Peters DJ, Somlo S, Torres VE, Walz G, Zhou J, Yu AS. The future of polycystic kidney disease research−as seen by the 12 Kaplan awardees. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 2081–2095, 2015. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014121192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belibi FA, Reif G, Wallace DP, Yamaguchi T, Olsen L, Li H, Helmkamp GM Jr, Grantham JJ. Cyclic AMP promotes growth and secretion in human polycystic kidney epithelial cells. Kidney Int 66: 964–973, 2004. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cabal-Hierro L, O’Dwyer PJ. TNF signaling through RIP1 kinase enhances SN38-induced death in colon adenocarcinoma. Mol Cancer Res 15: 395–404, 2017. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-16-0329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carney EF. Polycystic kidney disease: macrophage migration inhibitory factor regulates cyst growth in ADPKD. Nat Rev Nephrol 11: 388, 2015. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2015.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cassini MF, Kakade VR, Kurtz E, Sulkowski P, Glazer P, Torres R, Somlo S, Cantley LG. Mcp1 promotes macrophage-dependent cyst expansion in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 29: 2471–2481, 2018. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2018050518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cornec-Le Gall E, Audrézet MP, Chen JM, Hourmant M, Morin MP, Perrichot R, Charasse C, Whebe B, Renaudineau E, Jousset P, Guillodo MP, Grall-Jezequel A, Saliou P, Férec C, Le Meur Y. Type of PKD1 mutation influences renal outcome in ADPKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 1006–1013, 2013. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012070650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dinarello CA. The interleukin-1 family: 10 years of discovery. FASEB J 8: 1314–1325, 1994. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.8.15.8001745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8a.Di Paolo NC, Shafiani S, Day T, Papayannopoulou T, Russell DW, Iwakura Y, Sherman D, Urdahl K, Shayakhmetov DM. Interdependence between interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor regulates TNF-dependent control of mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Immunity 43: 1125–1136, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8b.Di Paolo NC, Shayakhmetov DM. Interleukin 1α and the inflammatory process. Nat Immunol 17: 906–913, 2016. doi: 10.1038/ni.3503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gabay C, Lamacchia C, Palmer G. IL-1 pathways in inflammation and human diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol 6: 232–241, 2010. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grantham JJ, Mulamalla S, Swenson-Fields KI. Why kidneys fail in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 7: 556–566, 2011. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2011.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris PC, Torres VE. Genetic mechanisms and signaling pathways in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Clin Invest 124: 2315–2324, 2014. doi: 10.1172/JCI72272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jans F, Vandenabeele F, Helbert M, Lambrichts I, Ameloot M, Steels P. A simple method for obtaining functionally and morphologically intact primary cultures of the medullary thick ascending limb of Henle’s loop (MTAL) from rabbit kidneys. Pflugers Arch 440: 643–651, 2000. doi: 10.1007/s004240000304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kleczko EK, Marsh KH, Tyler LC, Furgeson SB, Bullock BL, Altmann CJ, Miyazaki M, Gitomer BY, Harris PC, Weiser-Evans MCM, Chonchol MB, Clambey ET, Nemenoff RA, Hopp K. CD8+ T cells modulate autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease progression. Kidney Int 94: 1127–1140, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2018.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koo GB, Morgan MJ, Lee DG, Kim WJ, Yoon JH, Koo JS, Kim SI, Kim SJ, Son MK, Hong SS, Levy JM, Pollyea DA, Jordan CT, Yan P, Frankhouser D, Nicolet D, Maharry K, Marcucci G, Choi KS, Cho H, Thorburn A, Kim YS. Methylation-dependent loss of RIP3 expression in cancer represses programmed necrosis in response to chemotherapeutics. Cell Res 25: 707–725, 2015. doi: 10.1038/cr.2015.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee EJ. Cell proliferation and apoptosis in ADPKD. Adv Exp Med Biol 933: 25–34, 2016. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-2041-4_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li X, Magenheimer BS, Xia S, Johnson T, Wallace DP, Calvet JP, Li R. A tumor necrosis factor-α-mediated pathway promoting autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nat Med 14: 863–868, 2008. doi: 10.1038/nm1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Linkermann A, Green DR. Necroptosis. N Engl J Med 370: 455–465, 2014. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1310050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu X, Shi F, Li Y, Yu X, Peng S, Li W, Luo X, Cao Y. Post-translational modifications as key regulators of TNF-induced necroptosis. Cell Death Dis 7: e2293, 2016. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Magistroni R, Boletta A. Defective glycolysis and the use of 2-deoxy-D-glucose in polycystic kidney disease: from animal models to humans. J Nephrol 30: 511–519, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s40620-017-0395-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Makrygiannakis D, Catrina AI. Apoptosis as a mechanism of action of tumor necrosis factor antagonists in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 39: 679–685, 2012. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.110974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin-Sanchez D, Fontecha-Barriuso M, Carrasco S, Sanchez-Niño MD, Mässenhausen AV, Linkermann A, Cannata-Ortiz P, Ruiz-Ortega M, Egido J, Ortiz A, Sanz AB. TWEAK and RIPK1 mediate a second wave of cell death during AKI. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115: 4182–4187, 2018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1716578115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Menon V, Rudym D, Chandra P, Miskulin D, Perrone R, Sarnak M. Inflammation, oxidative stress, and insulin resistance in polycystic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 7–13, 2011. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04140510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Merta M, Tesar V, Zima T, Jirsa M, Rysavá R, Zabka J. Cytokine profile in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Biochem Mol Biol Int 41: 619–624, 1997. doi: 10.1080/15216549700201651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mun H, Park JH. Inflammation and fibrosis in ADPKD. Adv Exp Med Biol 933: 35–44, 2016. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-2041-4_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nigro EA, Castelli M, Boletta A. Role of the polycystins in cell migration, polarity, and tissue morphogenesis. Cells 4: 687–705, 2015. doi: 10.3390/cells4040687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nowak KL, Wang W, Farmer-Bailey H, Gitomer B, Malaczewski M, Klawitter J, Jovanovich A, Chonchol M. Vascular dysfunction, oxidative stress, and inflammation in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 1493–1501, 2018. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05850518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ong AC, Devuyst O, Knebelmann B, Walz G; ERA-EDTA Working Group for Inherited Kidney Diseases . Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: the changing face of clinical management. Lancet 385: 1993–2002, 2015. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60907-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pema M, Drusian L, Chiaravalli M, Castelli M, Yao Q, Ricciardi S, Somlo S, Qian F, Biffo S, Boletta A. mTORC1-mediated inhibition of polycystin-1 expression drives renal cyst formation in tuberous sclerosis complex. Nat Commun 7: 10786, 2016. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Privratsky JR, Zhang J, Lu X, Rudemiller N, Wei Q, Yu YR, Gunn MD, Crowley SD. Interleukin 1 receptor (IL-1R1) activation exacerbates toxin-induced acute kidney injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 315: F682–F691, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00104.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ruan J, Mei L, Zhu Q, Shi G, Wang H. Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein is a prognostic biomarker for cervical squamous cell cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 8: 15035–15038, 2015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saigusa T, Bell PD. Molecular pathways and therapies in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. Physiology (Bethesda) 30: 195–207, 2015. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00032.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schett G, Dayer JM, Manger B. Interleukin-1 function and role in rheumatic disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol 12: 14–24, 2016. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2016.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seldon CS, Colbert LE, Hall WA, Fisher SB, Yu DS, Landry JC. Chromodomain-helicase-DNA binding protein 5, 7 and pronecrotic mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein serve as potential prognostic biomarkers in patients with resected pancreatic adenocarcinomas. World J Gastrointest Oncol 8: 358–365, 2016. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v8.i4.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shillingford JM, Murcia NS, Larson CH, Low SH, Hedgepeth R, Brown N, Flask CA, Novick AC, Goldfarb DA, Kramer-Zucker A, Walz G, Piontek KB, Germino GG, Weimbs T. The mTOR pathway is regulated by polycystin-1, and its inhibition reverses renal cystogenesis in polycystic kidney disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 5466–5471, 2006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509694103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simms RJ. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. BMJ 352: i679, 2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Terryn S, Jouret F, Vandenabeele F, Smolders I, Moreels M, Devuyst O, Steels P, Van Kerkhove E. A primary culture of mouse proximal tubular cells, established on collagen-coated membranes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F476–F485, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00363.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang WS, SriRamaratnam R, Welsch ME, Shimada K, Skouta R, Viswanathan VS, Cheah JH, Clemons PA, Shamji AF, Clish CB, Brown LM, Girotti AW, Cornish VW, Schreiber SL, Stockwell BR. Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by GPX4. Cell 156: 317–331, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang Y, Chen M, Zhou J, Lv J, Song S, Fu L, Chen J, Yang M, Mei C. Interactions between macrophages and cyst-lining epithelial cells promote kidney cyst growth in Pkd1-deficient mice. J Am Soc Nephrol 29: 2310–2325, 2018. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2018010074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang J, Rudemiller NP, Patel MB, Karlovich NS, Wu M, McDonough AA, Griffiths R, Sparks MA, Jeffs AD, Crowley SD. Interleukin-1 receptor activation potentiates salt reabsorption in angiotensin II-induced hypertension via the NKCC2 Co-transporter in the nephron. Cell Metab 23: 360–368, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou F, Jiang X, Teng L, Yang J, Ding J, He C. Necroptosis may be a novel mechanism for cardiomyocyte death in acute myocarditis. Mol Cell Biochem 442: 11–18, 2018. doi: 10.1007/s11010-017-3188-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]