Abstract

Capillary derecruitment distal to a coronary stenosis is implicated as the mechanism of reversible perfusion defect and potential myocardial ischemia during coronary hyperemia; however, the underlying mechanisms are not defined. We tested whether pericyte constriction underlies capillary derecruitment during hyperemia under conditions of stenosis. In vivo two-photon microscopy (2PM) and optical microangiography (OMAG) were used to measure hyperemia-induced changes in capillary diameter and perfusion in wild-type and pericyte-depleted mice with femoral artery stenosis. OMAG demonstrated that hyperemic challenge under stenosis produced capillary derecruitment associated with decreased RBC flux. 2PM demonstrated that hyperemia under control conditions induces 26 ± 5% of capillaries to dilate and 19 ± 3% to constrict. After stenosis, the proportion of capillaries dilating to hyperemia decreased to 14 ± 4% (P = 0.05), whereas proportion of constricting capillaries increased to 32 ± 4% (P = 0.05). Hyperemia-induced changes in capillary diameter occurred preferentially in capillary segments invested with pericytes. In a transgenic mouse model featuring partial pericyte depletion, only 14 ± 3% of capillaries constricted to hyperemic challenge after stenosis, a significant reduction from 33 ± 4% in wild-type littermate controls (P = 0.04). These results provide for the first time direct visualization of hyperemia-induced capillary derecruitment distal to arterial stenosis and demonstrate that pericyte constriction underlies this phenomenon in vivo. These results could have important therapeutic implications in the treatment of exercise-induced ischemia.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY In the setting of coronary arterial stenosis, hyperemia produces a reversible perfusion defect resulting from capillary derecruitment that is believed to underlie cardiac ischemia under hyperemic conditions. We use optical microangiography and in vivo two-photon microscopy to visualize capillary derecruitment distal to a femoral arterial stenosis with cellular resolution. We demonstrate that capillary constriction in response to hyperemia in the setting of stenosis is dependent on pericytes, contractile mural cells investing the microcirculation.

Keywords: capillaries, derecruitment, ischemia, pericytes, stenosis

INTRODUCTION

When coronary perfusion pressure drops in the presence of coronary stenosis, the combination of arterial autoregulation and collateral blood flow maintains resting capillary hydrostatic pressure (CHP) and myocardial blood flow (24, 36). However, exercise-induced or pharmacological hyperemia causes a reversible perfusion defect in tissue downstream of the stenosis, which is characterized by a reduction in capillary blood volume and increased capillary resistance (6, 23). This phenomenon, termed capillary derecruitment, appears to maintain CHP in the face of a drop in coronary perfusion pressure caused by an increase in blood flow through a stenosis during hyperemia, even at the expense of potential myocardial ischemia. The cellular mechanisms underlying capillary derecruitment are not defined.

Capillaries are generally presumed to be passive players in blood flow regulation due to their lack of contractile vascular smooth muscle cells. However, recent studies in the brain and retina suggest that pericytes, the contractile mural cells investing the microvasculature, can regulate blood flow at the capillary level (19, 30, 32, 35). Pharmacological or electrical stimulation of pericytes constricts capillaries. Furthermore, pericyte-mediated changes in capillary diameter contribute to the physiological regulation of cerebral blood flow during functional hyperemia (26) as well as pathological restriction of blood flow after experimental cerebral ischemia (19, 35).

We hypothesized that pericytes are responsible for capillary derecruitment during hyperemia in the presence of a stenosis. Because dynamic in vivo imaging with single-cell resolution is not currently practicable in the coronary microcirculation, we used in vivo two-photon microscopy (2PM) and optical microangiography (OMAG) to directly visualize capillary derecruitment in a skeletal muscle preparation. To visualize pericytes, we used the NG2-DsRed transgenic mice expressing red fluorescent protein in pericytes. To test the necessity of pericytes in capillary constriction, we used a mouse line featuring partial pericyte depletion (PPD) resulting from seven point mutations in the platelet-derived growth factor receptor-β gene (PdgfrßF7/F7 mice), which causes pericytes to degenerate.

METHODS

Animal preparation.

All experiments were approved by the Oregon Health and Science University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice of both sexes were used and were anesthetized with ketamine (0.12 mg/g ip) and xylazine (0.01 mg/g ip). Body temperature was held constant at 37°C with a temperature-controlled warming pad, and the left leg was stabilized in a custom-made cradle. A skin incision was made along the length of the femoral artery and skin dissected free above the medial hamstring muscle. For the stenosis experiments, the femoral artery was gently separated from the femoral vein and nerve proximal to the bifurcation of the superficial caudal epigastric artery. A 6-0 silk suture was looped under the femoral artery immediately proximal to the epigastric artery.

Changes in skeletal muscle perfusion distal to the planned stenosis site were monitored using laser-Doppler flowmetry. After 5 min of baseline data acquisition, a stenosis was created by placing a 33-G needle (outer diameter 260 µm) next to the femoral artery and tying the silk suture gently around the artery and needle and then immediately removing the needle to permit blood flow through the stenosis site (Fig. 1A). This procedure does not affect resting blood flow due to autoregulation (20). Laser-Doppler measurements were taken for an additional 10 min to confirm reestablishment of resting blood flow. In control sham treatment mice, the entire procedure was identical, except for stenosis creation. A fixation plate was mounted over the gracilis muscle, and saline was placed on top of the muscle before a 10-mm coverslip was attached. The anesthetized mouse was fixed in a stereotaxic frame and transferred either to the 2PM or OMAG imaging station.

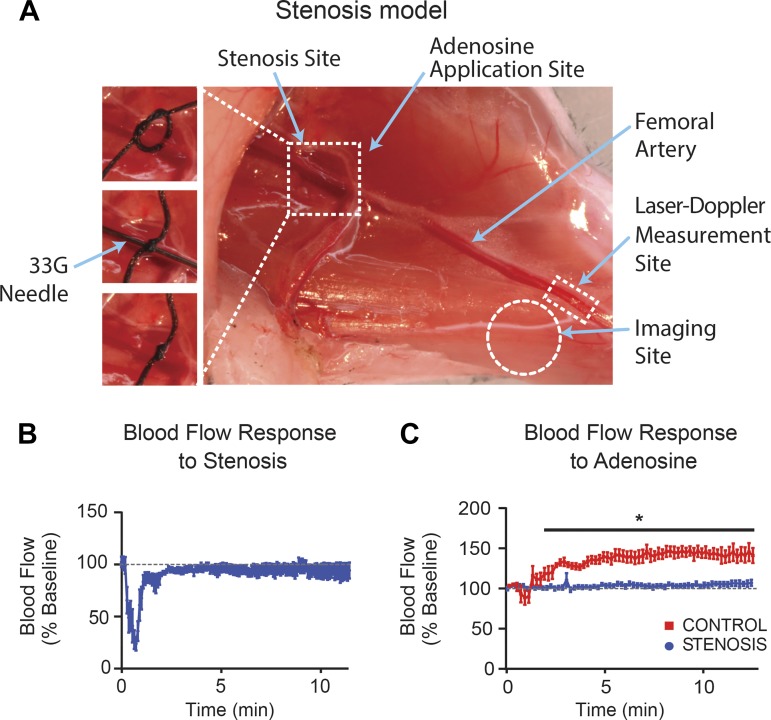

Fig. 1.

Experimental stenosis of femoral artery. A: image of the skeletal muscle preparation indicating stenosis site (dashed line square), femoral artery (arrow), and imaging site (dashed line circle). B: laser-Doppler flowmetry shows that, after an initial drop at the time of stenosis induction, femoral arterial blood flow (BF) recovers to baseline levels. C: in controls, adenosine (6 mM) increases femoral arterial BF, whereas in the presence of stenosis this hyperemic response is abolished. *P < 0.05.

For ATP superfusion experiments, the skin around the gracilis muscle was removed and a fixation plate mounted on the skeletal muscle with PE10 tubing attached to it, creating a perfusion chamber that allowed the superfusion of ATP and saline (vehicle control). A 10-mm coverslip placed on the fixation plate without trapping air bubbles and the animal was moved to the imaging site.

Optical microangiography.

OMAG based on opticalcoherence tomography was used to measure capillary blood flow changes in the gracilis muscle (9, 29). It allows acquisition of blood flow information at the capillary level from the volumetric data set by analyzing the intrinsic scattering properties of moving blood cells (blood flow image) without the need for contrast agents. Blood flow can be imaged ≤2 mm beneath the tissue surface (4).

A custom-built spectral domain optical coherence tomography system was used. The system is equipped with a broadband super-luminescent diode light source with a central wavelength of 1,310 nm and a spectral bandwidth of 110 nm, providing axial resolution of ∼5.1 µm in tissue. A ×10 objective lens was used to deliver and collect the probing beam from the sample, providing a lateral resolution of 10 µm. The collected light was combined with the reference light that was detected by a high-resolution spectrometer to provide depth (z) information.

Images were acquired at 92,000 axial scans/s, with the light power of the probe beam set to 5 mW. To enable three-dimensional imaging, an x-y galvanometer scanner was used to raster scan the probing beam over the sample. For structural microangiography, a cube representing a tissue volume of 2.0 mm3 was imaged. For flux images, a smaller volume of 0.50 mm3 was imaged to capture the total number of blood cells passing through the imaging voxel per unit time (10, 28).

Anesthetized animals were placed on the OMAG station, and a structural image was first acquired for correct positioning and focus. The skeletal vasculature was then repeatedly imaged. Both structural and flux images were sequentially acquired at 60-s intervals for the duration of the experiment. After five baseline scans, adenosine (6 mM) was superfused over the stenosis site.

A custom barrier was placed between the stenosis and imaging sites to ensure that the imaging region was not directly superfused by adenosine. Although we cannot rule out the possibility that adenosine administered abluminally to the proximal femoral artery diffuses across the arterial wall into the blood column to act on distal pericytes, the physical separation between the adenosine administration site and the distal imaging field makes this unlikely. Thus, adenosine applied in this manner is expected to dilate the artery while largely avoiding its local vasomotor effects on pericytes in the distal capillary bed. To test the effect of pericyte constriction on capillary flow, the vasoconstrictor ATP (1 and 10 mM) or a vehicle control (saline) was superfused directly over the imaging site.

Flux images were processed to separate dynamic pixels (e.g., moving red blood cells within vessel) from static pixels (e.g., tissue structure) (Supplemental Fig. S1, A–C; Supplemental Figures for this article are available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.8059754.v1). Only capillaries were assessed for flux changes using a size filter, excluding all vessels >10 µm in diameter. RBC/s data from each image were obtained as relative counts of pixels in RBC/s bins of a multiple of ∼7 (0, 7, 14, 21, 29, 36, 43, 51, 58, 65, 73, 80, 87, and 94 RBC/s).

In vivo two-photon microscopy.

2PM was conducted in a separate cohort of animals from those used for OMAG experiments. To visualize the vascular lumen, 0.1 ml of FITC-dextran (molecular mass, 70 kDa, 1% in saline) was injected via tail vein before imaging. A Chameleon laser (Coherent, LSM 7MP; Zeiss) was used in conjunction with a ×20 (0.9 NA) water-immersed lens and ×2 optical zoom to image the vasculature of the gracilis muscle in vivo. Excitation wavelength was 925 nm. Skeletal muscle was first imaged using 896 × 896 pixel frames of 70-µm z-stack with 5-µm z-steps for a high-resolution image. Image stacks encompassing 45–60 µm in depth at 5-µm z-steps were captured every 40 s for the duration of the experiment. After 10 baseline scans, adenosine (6 mM in saline) was superfused over the stenosis site to induce hyperemia, as described above, with care taken not to superfuse the imaging site. To image pericyte constriction, ATP (1 and 10 mM) was superfused directly over the imaging site. A stepwise increase in ATP concentration was implemented to minimize tissue movement during the superfusion period.

Image analysis was performed with Bitplane IMARIS software (version 8.4.2). To measure the temporal changes in capillary diameter, filaments were drawn over all capillaries that stayed within the field of view for the duration of the experiment and volumetric analysis of the whole segments performed. Thus, diameter measurements were integrated along the entire segment length for each capillary. Segments that increased or decreased in average diameter by >5% were classified as “dilating” or “constricting,” respectively. To define overall network-aggregate changes in diameter (Supplemental Fig. S1D), vessel diameters across all segments were averaged at each time point.

Immunofluorescence evaluation of pericytes.

At the end of in vivo imaging, PPD mice (PdgfrβF7/F7) and their wild-type littermate controls (Pdgfrβ+/+) were perfusion-fixed (4% paraformaldehyde in PBS) 15 min after intravenous injection of fluorescent isolectin (1:5 dilution in 0.9% saline, Isolectin GS-IB4, Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 20-µm-thick cryosections were obtained. Sections were rehydrated in PBS and blocked in PBS containing 4% normal goat serum, 1% bovine serum albumin, and 0.3% Triton X-100 for 1 h at room temperature. This was followed by incubation with mouse anti-Pdgfrβ antibody (1:100; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) at 4°C overnight. After washing with PBS, sections were incubated with donkey anti-mouse IgG Alexa Fluor 594 for 2 h at room temperature (Thermo Fisher Scientific), followed by 10 min of staining with DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich) and mounting with Fluoromount-G (Thermo Fisher scientific). All images were acquired by a blinded observer using confocal laser-scanning microscopy (Nikon A1R). Three separate 220 × 220-µm fields from four different sections were imaged per animal and analyzed using Bitplane IMARIS software. The percentage of PDGFRβ-positive pericyte coverage of isolectin-positive capillaries was quantified in the Bitplane IMARIS software environment by normalizing the PDRFRβ-positive signal to the isolectin positive capillary signal.

Statistics.

Unless otherwise noted, all data are expressed as means ± 1SE, and differences were considered to be significant at P < 0.05. Differences in blood flow (BF) and proportion of responsive capillary segments were evaluated by two-way repeated-measures ANOVA with Sidak post hoc test. Capillary response distributions were evaluated using unpaired nonparametric Mann-Whitney test with Kolmogorov-Smirnov post hoc test. Differences in PDGFRβ coverage of capillaries were evaluated by unpaired Student’s t-test. For OMAG RBC flux data, we evaluated the associations between capillary response and factors such as stenosis, treatments, time, and layer, using Poisson regression with random effects. Random effects were incorporated to account for animal-level repeated measurements. All hypothesis tests were two sided.

RESULTS

Induction of stenosis resulted in a transient reduction in laser-Doppler measured blood flow that returned to baseline within 3–4 min (n = 5; Fig. 1B). Following sham surgery, local administration of 6 mM adenosine to the femoral artery increased BF to ∼150% of baseline, whereas in the presence of stenosis the hyperemic response was abolished (n = 5–8, P < 0.001; Fig. 1C). Maintenance of normal resting blood flow with complete abolishment of the hyperemic response fulfills the criterion of critical stenosis.

Hyperemia causes capillary constriction and derecruitment in the setting of critical stenosis.

We acquired RBC flux images by OMAG (Fig. 2A and Supplemental Fig. S1, A–C) at 1-min intervals and used angiography scans to verify stable imaging position. In sham controls, hyperemia increased RBC flux [Fig. 2B, compare black (baseline) with blue (5 min posthyperemia) plots], whereas in the presence of stenosis it significantly reduced RBC flux [P < 0.001; Fig. 2B, compare orange (baseline) to red (5 min postadenosine) plots; n = 6–8/group].

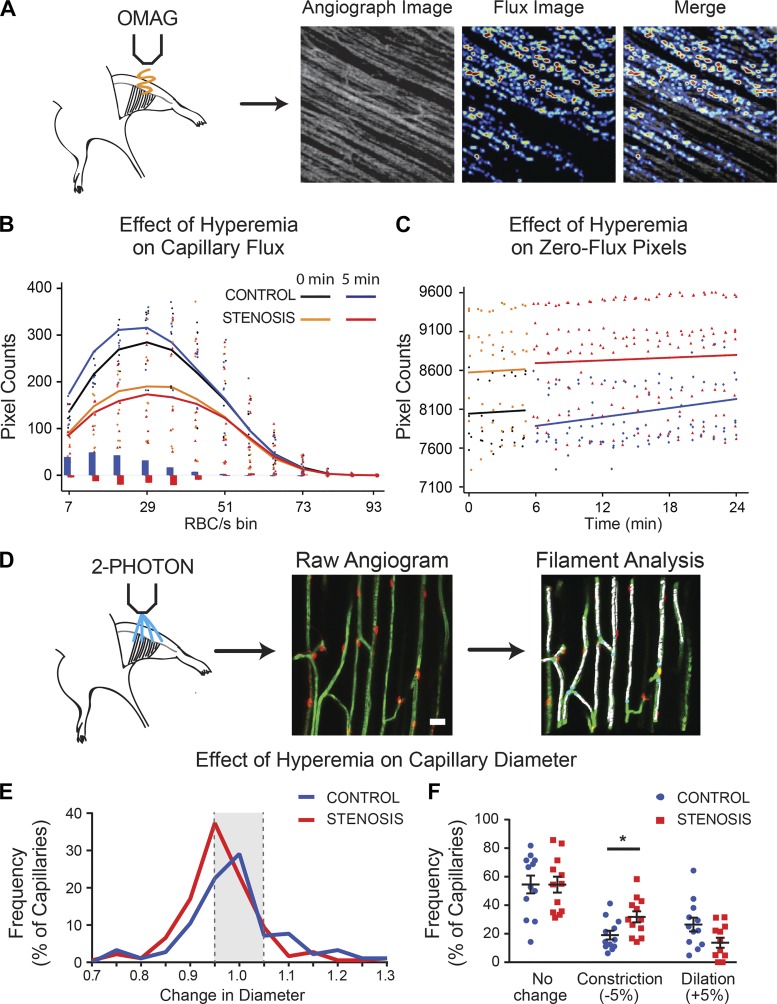

Fig. 2.

Hyperemia in the presence of stenosis causes capillary derecruitment. A: angiography image was used for initial positioning. B: red blood cell (RBC) flux in superficial layer capillaries at baseline (0 min) and 5 min following adenosine (6 mM) administration. Adenosine increased RBC flux (RBC/s) under control conditions, but in the presence of stenosis. Solid line plots reflect mean counts across animals within each experimental group, whereas dot plots reflect individual data points. Vertical blue and red lines reflect mean differences in pixel counts between t = 0 and 5 min for control and stenosis groups, respectively. C: in contrast to controls, the number of zero-flux pixels increased after stenosis, reflecting capillary derecruitment. D: changes in capillary diameter were evaluated in vivo by 2-photon microscopy in NG2-DsRed mice injected intravenously with FITC-dextran. Raw angiograms were skeletonized to filaments using IMARIS software and analyzed. Scale bar = 20 µm. E: compared with controls, the distribution of hyperemia-induced change in diameter of capillary segments shifted leftward, toward greater constriction. F: a greater proportion of capillary segments constricted during hyperemia when a stenosis was present. See text for details. *P < 0.05.

We evaluated capillary recruitment or derecruitment by plotting decreases or increases, respectively, in the number of zero-value pixels in the flux image (where a value of zero indicates no flux; Supplemental Fig. S1C and Fig. 2C). In controls, an increase in RBC flux following hyperemia was accompanied by a reduction in the number of zero-value pixels, suggesting capillary recruitment [n = 6–8/group; relative rate of treatment to control = 0.966, 95% confidence interval (CI) = (0.962, 0.971), P < 0.001; Fig. 2C (compare black with blue lines)]. In contrast, in the setting of stenosis, hyperemia-induced decline in RBC flux was accompanied by an increase in the number of zero-value pixels, corresponding to capillary derecruitment that persisted throughout the 20 min of imaging following adenosine administration [n = 6/group; relative rate of change = 1.066, 95% CI = (1.017, 1.118), P = 0.0080; Fig. 2C (compare orange with red lines)].

We next evaluated changes in capillary diameter by imaging the microvascular bed under 2PM at 40-s intervals following intravenous administration of the fluorescent tracer FITC-conjugated dextran (molecular mass, 70 kDa). The diameters of all capillary segments within the imaging frame were measured volumetrically using the filaments module in IMARIS (Fig. 2D). Following hyperemic challenge in sham animals, the average capillary segment diameters increased transiently in controls, but returned to baseline within 1–2 min (n = 12 animals/group, 15–16 capillaries/animal, P = 0.03; Supplemental Fig. S1D). After stenosis, hyperemia induced a transient decline in the diameter followed by slow normalization (P = 0.04). A distribution plot of the change in capillary diameters over the first 5 min following hyperemic challenge showed a marked leftward shift, indicating an increase in constricting capillaries in the presence of stenosis compared with sham (P = 0.003; Fig. 2E). In sham-treated animals, hyperemia dilated 26 ± 5% (>5% increase in diameter) and constricted 19 ± 3% of capillaries (>5% decrease in diameter). In stenosis animals, hyperemia dilated only 14 ± 4% of capillaries and constricted 32 ± 4% of capillaries (P = 0.049 compared with control; Fig. 2, E and F).

Thus, although there is variation in capillary segments that dilated and constricted in response to hyperemia (Fig. 2, E and F), the greater number of constricting segments in the presence of stenosis resulted in an overall reduction in capillary network diameter (Supplemental Fig. S1D). Therefore, visualization of both RBC flux and the direct measurement of capillary diameter throughout the microvascular network demonstrate that hyperemia in the presence of a stenosis results in capillary derecruitment, led predominantly by capillary constriction.

Capillary derecruitment is associated with constriction of pericyte-invested capillaries.

The skeletal muscle microvascular bed was visualized (Fig. 3A), and individual capillary segments were classified based on whether they were associated with pericyte soma (Fig. 3B), pericyte processes, or neither (Fig. 3C). The numbers of segments represented in each classification for each experimental group are detailed in Supplemental Table S1 (Supplemental Table S1 can be found at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.8059772.v1).

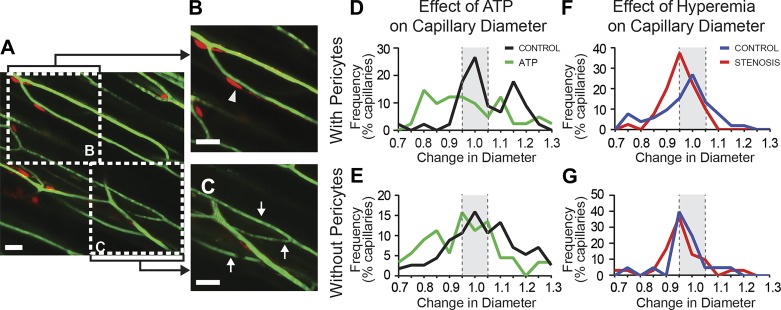

Fig. 3.

Capillary constrictions occur at pericyte locations. A: skeletal muscle microvasculature visualized by in vivo 2-photon microscopy in NG2-DsRed mice. Vessel segments were categorized based on the presence (B) or absence (C) of pericytes. Scale bars = 20 µm; arrowheads, segments invested with pericytes; arrows, segments lacking pericyte investment. D: compared with controls, topical administration of ATP (1–10 mM) resulted in a significant leftward shift, toward constriction, in capillary diameter in segments containing pericytes. E: capillaries lacking pericytes did not exhibit an altered response to ATP. F: in the presence of stenosis, hyperemia-induced capillary segments were invested with pericytes to shift toward constriction. G: capillary segments lacking pericyte investment did not exhibit any difference in response to hyperemia. See text for details.

We first used ATP, a pericyte constrictor (25, 35), as a positive control to confirm that pericyte constriction can be detected using 2PM. ATP superfusion evoked a pronounced constriction in pericyte-associated capillary segments (n = 10, P = 0.001; Fig. 3D) but no change in vessels devoid of pericytes (n = 10, P = 0.10; Fig. 3E). We next tested whether capillary constriction following hyperemic challenge in the setting of stenosis was associated with pericyte investment of capillary segments. In the presence of stenosis, hyperemia evoked an increase in the number of constrictions and a decrease in the number of dilations among capillary segments invested with pericytes (n = 12, P = 0.04; Fig. 3F) but no change in segments lacking pericytes (n = 12, P = 0.36; Fig. 3G).

Pericyte depletion prevents capillary derecruitment.

To determine the obligatory role of pericytes in mediating capillary derecruitment, we used PPD mice, a transgenic line in which pericytes are partially but significantly depleted due to mutations in the Pdgfrβ (5, 41). We confirmed that PPD mice have fewer pericytes by using immunofluorescence labeling for PDGFRβ to identify pericytes and fluorescent isolectin B4 to label vessels. In the skeletal muscle of PPD mice, coverage of isolectin-labeled vascular structures with PDGFRβ-positive pericytes was reduced by 45% compared with wild-type littermate controls (37 ± 4% of vessels covered in PPD mice compared with 69 ± 4% in wild-type animals, P < 0.001; Fig. 4A).

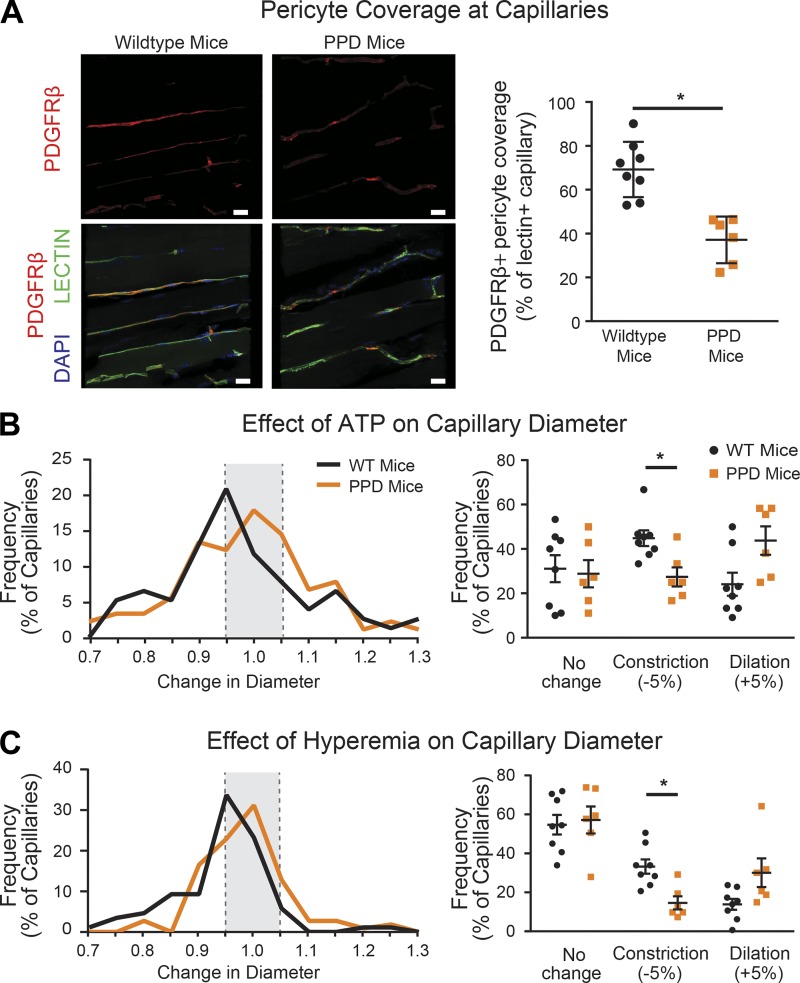

Fig. 4.

Pericyte depletion prevents capillary derecruitment in the setting of stenosis. A: representative images of the platelet-derived growth factor receptor-β (PDGFRβ) immunofluorescence (red) and isolectin B4-labeled capillaries (green) in the skeletal muscle of partial pericyte depletion (PPD) mice and wild-type littermate controls. Scale bars = 20 µm. B: compared with controls, ATP superfusion caused a rightward shift in capillary responses in PPD mice and a decrease in the number of constricting capillary segments. C: during stenosis, the distribution of capillary responses to hyperemic challenge in PPD mice shifted rightward toward dilation compared with controls, reflecting a decline in the number of constricting capillary segments. See text for details. Compared with controls, ATP superfusion caused a rightward shift in capillary responses in PPD mice and a decrease in the number of constricting capillary segments. *P < 0.05.

We next tested the contractile capacity of capillaries in PPD and control mice. ATP induced constriction of 45 ± 4% of capillaries in wild-type littermate controls compared with only 27 ± 4% of capillaries in PPD animals (n = 6–8, P = 0.04; Fig. 4B), a reduction of ∼40%. Conversely, the proportion of capillary segments dilating to ATP was significantly increased from 24 ± 5% in wild-type to 44 ± 6% in PPD mice (n = 6–8, P = 0.02). Because ATP-induced capillary constriction depends upon pericytes (8, 12, 35), these findings are consistent with loss of pericyte function in PPD mice.

In the presence of stenosis, PPD mice displayed a significant reduction in the proportion of constricting capillary segments during hyperemia compared with wild-type littermate controls (33 ± 4% in wild-type vs. 14 ± 3% in PPD mice, n = 6–8, P = 0.04; Fig. 4C). These findings confirm that pericyte depletion prevents capillary derecruitment in the setting of stenosis.

DISCUSSION

CHP is a key determinant of tissue homeostasis and is maintained within a very narrow range by autoregulation (38). When systemic blood pressure increases or falls, arterioles constrict or dilate, respectively (17), maintaining both blood flow and CHP despite fluctuations in perfusion pressure. In the presence of coronary stenosis and reduced coronary perfusion pressure, resistance vessels dilate to maintain constant coronary blood flow and CHP. Under these conditions, hyperemia causes the perfusion pressure distal to the stenosis to drop. To maintain a constant CHP in the face a falling perfusion pressure, capillary resistance increases by closing off or constricting capillaries, a phenomenon termed capillary derecruitment. We previously inferred capillary decruitment by noting a decrease in myocardial blood volume measured on echocardiography using gas-filled microbubbles in the presence of a coronary stenosis. Because capillaries do not have smooth muscle, we conjectured that “pre-capillary sphincters” or pericytes could be responsible for this phenomenon (23, 24).

Capillary derecruitment results in a perfusion defect on ultrasound imaging with microbubbles (23, 24) as well as on MRI and CT using contrast agents. Evaluation of radionuclide tracers has shown that capillary derecruitment decreases the permeability surface area product, thereby reducing tracer uptake and resulting in a perfusion defect. Intriguingly, in the setting of coronary stenosis and hyperemia, capillary derecruitment functions to maintain CHP at the expense of myocardial blood flow, possibly contributing to myocardial ischemia (40).

In this study, we tested the hypothesis that pericytes are responsible for capillary derecruitment, seeking to corroborate our prior findings using microbubbles with direct visualization of capillary derecruitment. Owing to the rapid beating of the mouse heart, which complicates microscopic vascular imaging considerably, we used the skeletal muscle as surrogate tissue and employed two novel imaging approaches (2PM and OMAG) to directly visualize capillary derecruitment. We found that hyperemia in the setting of femoral artery stenosis produced a loss of RBC flux through a fraction of the capillary bed, reflecting capillary derecruitment, that coincided with increasing constriction of a larger subset of capillary segments within the microvascular bed. Although it is possible that capillary constriction in this setting could result from passive constriction, due to the drop in perfusion pressure distal to the stenosis, in addition to active constriction, capillary segments that constricted were invested with pericytes, and depletion of pericytes in PPD mice (wherein altered signaling via the mutant PDGFRβ causes pericytes to degenerate) prevented capillary derecruitment in response to hyperemia. These data provide strong evidence that active capillary constriction by pericytes underlies the reversible perfusion defects observed in the presence of stenosis.

Pericytes represent a heterogeneous cell population with several subtypes that differ by morphology and location within the vascular tree (2). Pericytes on pre- and postcapillary microvessels express α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and other contractile proteins (34), and therefore, they can contribute to capillary BF regulation. In contrast, reports on pericytes residing on capillaries (pericapillary pericytes) are not consistent, with some studies reporting expression of α-SMA (3, 42) and others not (21, 39).

A recent study using techniques to prevent F-actin depolymerization showed that pericapillary pericytes do indeed express α-SMA (1). Capillary pericytes also express other contractile proteins, including β- and γ-SMA, skeletal muscle actin, desmin, and non-smooth muscle myosin variants (3). Although some studies failed to show contractility in capillaries (21, 39), the majority have found that pericytes can constrict or dilate capillary diameter in response to chemical or electrical stimuli and thus can regulate capillary blood flow (2, 18, 19, 26, 32, 35). Our observation that ATP-evoked constriction of skeletal muscle capillaries is abolished in PPD animals confirms a contractile role for pericytes in skeletal muscle capillaries.

Our study demonstrates that pericytes mediate capillary constriction in response to a drop in perfusion pressure during hyperemic challenge in the setting of a stenosis. Whether this vasomotor response originates locally or within the pericyte or capillary endothelial cell or is propagated from proximal arterioles was not addressed by us. Studies of the cerebral vasculature demonstrate that pericytes actively dilate capillaries during neuronal activation and that capillary dilation precedes arteriolar dilation, suggesting that pericyte vasomotor responses to functional stimuli can be initiated locally (19). Similar results have been reported in the hamster cremaster muscle (11). Capillary endothelial cells respond directly to depolarizing concentrations of potassium and calcium with changes in membrane potential (15) that can be conducted along the endothelium to upstream vessels to induce remote vasodilation or constriction (11).

Recent evidence suggests that pericytes also play an important role in BF regulation under pathological conditions, including ischemia (19, 35, 42) and spinal cord injury (30). Under ischemic conditions, pericytes restrict capillary BF and then die in a permanently contracted state, which can contribute to no-reflow and tissue damage (19). Furthermore, the PPD mice we used show impaired cerebral BF regulation, which may contribute to age-related vascular dysfunction (26, 33). The novel finding of the current study is that pericytes constrict under nonischemic conditions in response to hyperemia in the setting of stenosis, likely in response to reduced perfusion pressure (23). Physiologically, this derecruitment would have the effect of reducing the total cross-sectional area of the capillary bed and maintaining perfusion pressure across the microcirculation. Because the majority of resistance in the coronary circulation during hyperemia is offered by the capillary bed and not the stenosis itself (23), when autoregulation is exhausted, pericytes may represent the last line of defense for maintaining a constant CHP, possibly even at the expense of tissue ischemia. If severe, however, such capillary derecruitment in the presence of a coronary stenosis could also cause myocardial tissue ischemia, a possibility that has significant clinical implications.

Although we made our original observations of capillary derecruitment in the coronary vascular bed, the current findings suggest that this phenomenon may also occur in the peripheral vasculature. Peripheral arterial disease is common in older patients who have diabetes and other comorbidities. These patients develop intermittent claudication that in some cases leads to critical limb ischemia requiring amputation (13, 14). It is likely that, similar to the myocardium, pericyte-mediated capillary derecruitment during exercise-induced hyperemia contributes to limb ischemia. Therefore, pharmacological approaches aimed specifically at preventing pericyte contractility may represent a valuable clinical intervention to ameliorate both myocardial and limb ischemia. Clearly, further studies are warranted to investigate this possibility.

Even at baseline we noted a heterogenous response of capillaries to adenosine, with about one-third showing dilation, one-sixth showing constriction, and half showing no change. Whereas the mean arteriolar dimensions increase in the presence of adenosine, about one-sixth of feeding arterioles constrict through the action of adenosine on A3 receptor on mast cells (37). Furthermore, the volumetric arterial flow in the myocardium induced by adenosine exceeds that in the capillaries, indicating that the drop in capillary resistance does not parallel a drop in arteriolar resistance, probably because of heterogeneity in capillary diameter responses (27). In our study, the ratio of constricting to dilating capillaries was reversed when adenosine was applied in the presence of stenosis.

There are several limitations of this study. First, we used a skeletal muscle preparation in lieu of the heart for practical reasons. We could not have visualized pericyte function in a beating heart. Second, blood supply to the femoral arterial bed is somewhat dissimilar to that of the coronary arterial bed, with a lot fewer open capillaries at rest and resting flow being minimal. However, as shown in this study, the skeletal muscle exhibits a similar capillary derecruitment as the myocardium during hyperemia in the presence of a stenosis. There are extensive studies in the tissue fluid hemostasis of the skeletal muscle, the results of which closely resemble that of the myocardium (7, 22, 31). Third, whether the vasomotor response to hyperemia in the setting of stenosis is intrinsic to the pericyte itself, or whether it requires communication between endothelial cells and pericytes, remains unclear and an important direction for subsequent studies. The structure of the capillary network in the skeletal muscle did not allow concurrent imaging of capillaries or their feeding arterioles in the present study.

In summary, we were able to directly visualize capillary derecruitment in the setting of stenosis in the skeletal muscle of mice in vivo. We further demonstrate that capillary derecruitment results from capillary constriction by pericytes. These findings suggest that pericytes are key regulators of capillary BF and hydrostatic pressure. Strategies aimed at preventing pericyte constriction may serve as a novel therapeutic approach for preventing tissue damage during or after coronary ischemic events.

GRANTS

This study was funded by the Oregon Health and Science University Knight Cardiovascular Institute and the National Institutes of Health Grants R01-HL-093140 (to R. K. Wang) and NS-100459 (to B. Zlokovic).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.M., A.M., B.Z., R.K.W., N.J.A., S.K., and J.J.I. conceived and designed research; C.M., A.M., K.G., Y.L., W.W., and N.D.Y. performed experiments; C.M., A.M., K.G., Y.L., W.W., N.D.Y., and B.Z. analyzed data; C.M., A.M., K.G., N.D.Y., B.Z., R.K.W., N.J.A., S.K., and J.J.I. interpreted results of experiments; C.M., A.M., K.G., N.D.Y., B.Z., and J.J.I. prepared figures; C.M., A.M., K.G., N.D.Y., B.Z., S.K., and J.J.I. drafted manuscript; C.M., A.M., K.G., N.D.Y., B.Z., R.K.W., N.J.A., S.K., and J.J.I. edited and revised manuscript; C.M., A.M., K.G., Y.L., W.W., N.D.Y., B.Z., R.K.W., N.J.A., S.K., and J.J.I. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Stefanie Kaech-Petrie and Aurelie Snyder (Oregon Health and Science University Advance Light Microscopy Core) for assistance with microscopy and image processing.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alarcon-Martinez L, Yilmaz-Ozcan S, Yemisci M, Schallek J, Kılıç K, Can A, Di Polo A, Dalkara T. Capillary pericytes express α-smooth muscle actin, which requires prevention of filamentous-actin depolymerization for detection. eLife 7: e34861, 2018. doi: 10.7554/eLife.34861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Attwell D, Mishra A, Hall CN, O’Farrell FM, Dalkara T. What is a pericyte? J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 36: 451–455, 2016. doi: 10.1177/0271678X15610340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bandopadhyay R, Orte C, Lawrenson JG, Reid AR, De Silva S, Allt G. Contractile proteins in pericytes at the blood-brain and blood-retinal barriers. J Neurocytol 30: 35–44, 2001. doi: 10.1023/A:1011965307612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baran U, Zhu W, Choi WJ, Omori M, Zhang W, Alkayed NJ, Wang RK. Automated segmentation and enhancement of optical coherence tomography-acquired images of rodent brain. J Neurosci Methods 270: 132–137, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2016.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bell RD, Winkler EA, Sagare AP, Singh I, LaRue B, Deane R, Zlokovic BV. Pericytes control key neurovascular functions and neuronal phenotype in the adult brain and during brain aging. Neuron 68: 409–427, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bin JP, Le DE, Jayaweera AR, Coggins MP, Wei K, Kaul S. Direct effects of dobutamine on the coronary microcirculation: comparison with adenosine using myocardial contrast echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 16: 871–879, 2003. doi: 10.1067/S0894-7317(03)00423-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bosman J, Tangelder GJ, Oude Egbrink MG, Reneman RS, Slaaf DW. Capillary diameter changes during low perfusion pressure and reactive hyperemia in rabbit skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol 269: H1048–H1055, 1995. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.3.H1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cai C, Fordsmann JC, Jensen SH, Gesslein B, Lønstrup M, Hald BO, Zambach SA, Brodin B, Lauritzen MJ. Stimulation-induced increases in cerebral blood flow and local capillary vasoconstriction depend on conducted vascular responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115: E5796–E5804, 2018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1707702115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen CL, Wang RK. Optical coherence tomography based angiography [Invited]. Biomed Opt Express 8: 1056–1082, 2017. doi: 10.1364/BOE.8.001056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi WJ, Qin W, Chen CL, Wang J, Zhang Q, Yang X, Gao BZ, Wang RK. Characterizing relationship between optical microangiography signals and capillary flow using microfluidic channels. Biomed Opt Express 7: 2709–2728, 2016. doi: 10.1364/BOE.7.002709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen KD, Berg BR, Sarelius IH. Remote arteriolar dilations in response to muscle contraction under capillaries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 278: H1916–H1923, 2000. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.6.H1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crawford C, Wildman SS, Kelly MC, Kennedy-Lydon TM, Peppiatt-Wildman CM. Sympathetic nerve-derived ATP regulates renal medullary vasa recta diameter via pericyte cells: a role for regulating medullary blood flow? Front Physiol 4: 307, 2013. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Criqui MH, Aboyans V. Epidemiology of peripheral artery disease. Circ Res 116: 1509–1526, 2015. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.303849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Criqui MH, Langer RD, Fronek A, Feigelson HS, Klauber MR, McCann TJ, Browner D. Mortality over a period of 10 years in patients with peripheral arterial disease. N Engl J Med 326: 381–386, 1992. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199202063260605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dai M, Nuttall A, Yang Y, Shi X. Visualization and contractile activity of cochlear pericytes in the capillaries of the spiral ligament. Hear Res 254: 100–107, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duncker DJ, Bache RJ. Regulation of coronary blood flow during exercise. Physiol Rev 88: 1009–1086, 2008. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00045.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fernández-Klett F, Priller J. Diverse functions of pericytes in cerebral blood flow regulation and ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 35: 883–887, 2015. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2015.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hall CN, Reynell C, Gesslein B, Hamilton NB, Mishra A, Sutherland BA, O’Farrell FM, Buchan AM, Lauritzen M, Attwell D. Capillary pericytes regulate cerebral blood flow in health and disease. Nature 508: 55–60, 2014. doi: 10.1038/nature13165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris PJ, Behar VS, Conley MJ, Harrell FE Jr, Lee KL, Peter RH, Kong Y, Rosati RA. The prognostic significance of 50% coronary stenosis in medically treated patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation 62: 240–248, 1980. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.62.2.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hill RA, Tong L, Yuan P, Murikinati S, Gupta S, Grutzendler J. regional blood flow in the normal and ischemic brain is controlled by arteriolar smooth muscle cell contractility and not by capillary pericytes. Neuron 87: 95–110, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Järhult J, Mellander S. Autoregulation of capillary hydrostatic pressure in skeletal muscle during regional arterial hypo- and hypertension. Acta Physiol Scand 91: 32–41, 1974. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1974.tb05654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jayaweera AR, Wei K, Coggins M, Bin JP, Goodman C, Kaul S. Role of capillaries in determining CBF reserve: new insights using myocardial contrast echocardiography. Am J Physiol 277: H2363–H2372, 1999. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.6.H2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaul S, Ito H. Microvasculature in acute myocardial ischemia: part II: evolving concepts in pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Circulation 109: 310–315, 2004. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000111583.89777.F9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kawamura H, Sugiyama T, Wu DM, Kobayashi M, Yamanishi S, Katsumura K, Puro DG. ATP: a vasoactive signal in the pericyte-containing microvasculature of the rat retina. J Physiol 551: 787–799, 2003. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.047977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kisler K, Nelson AR, Rege SV, Ramanathan A, Wang Y, Ahuja A, Lazic D, Tsai PS, Zhao Z, Zhou Y, Boas DA, Sakadžić S, Zlokovic BV. Pericyte degeneration leads to neurovascular uncoupling and limits oxygen supply to brain. Nat Neurosci 20: 406–416, 2017. doi: 10.1038/nn.4489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kiyooka T, Hiramatsu O, Shigeto F, Nakamoto H, Tachibana H, Yada T, Ogasawara Y, Kajiya M, Morimoto T, Morizane Y, Mohri S, Shimizu J, Ohe T, Kajiya F. Direct observation of epicardial coronary capillary hemodynamics during reactive hyperemia and during adenosine administration by intravital video microscopy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H1437–H1443, 2005. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00088.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee J, Wu W, Lesage F, Boas DA. Multiple-capillary measurement of RBC speed, flux, and density with optical coherence tomography. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 33: 1707–1710, 2013. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Y, Choi WJ, Qin W, Baran U, Habenicht LM, Wang RK. Optical coherence tomography based microangiography provides an ability to longitudinally image arteriogenesis in vivo. J Neurosci Methods 274: 164–171, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2016.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Y, Lucas-Osma AM, Black S, Bandet MV, Stephens MJ, Vavrek R, Sanelli L, Fenrich KK, Di Narzo AF, Dracheva S, Winship IR, Fouad K, Bennett DJ. Pericytes impair capillary blood flow and motor function after chronic spinal cord injury. Nat Med 23: 733–741, 2017. doi: 10.1038/nm.4331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mellander S. On the control of capillary fluid transfer by precapillary and postcapillary vascular adjustments. A brief review with special emphasis on myogenic mechanisms. Microvasc Res 15: 319–330, 1978. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(78)90032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mishra A, Reynolds JP, Chen Y, Gourine AV, Rusakov DA, Attwell D. Astrocytes mediate neurovascular signaling to capillary pericytes but not to arterioles. Nat Neurosci 19: 1619–1627, 2016. doi: 10.1038/nn.4428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Montagne A, Nikolakopoulou AM, Zhao Z, Sagare AP, Si G, Lazic D, Barnes SR, Daianu M, Ramanathan A, Go A, Lawson EJ, Wang Y, Mack WJ, Thompson PM, Schneider JA, Varkey J, Langen R, Mullins E, Jacobs RE, Zlokovic BV. Pericyte degeneration causes white matter dysfunction in the mouse central nervous system. Nat Med 24: 326–337, 2018. doi: 10.1038/nm.4482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 34.Nehls V, Drenckhahn D. Heterogeneity of microvascular pericytes for smooth muscle type alpha-actin. J Cell Biol 113: 147–154, 1991. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.1.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peppiatt CM, Howarth C, Mobbs P, Attwell D. Bidirectional control of CNS capillary diameter by pericytes. Nature 443: 700–704, 2006. doi: 10.1038/nature05193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rouleau J, Boerboom LE, Surjadhana A, Hoffman JI. The role of autoregulation and tissue diastolic pressures in the transmural distribution of left ventricular blood flow in anesthetized dogs. Circ Res 45: 804–815, 1979. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.45.6.804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shepherd RK, Linden J, Duling BR. Adenosine-induced vasoconstriction in vivo. Role of the mast cell and A3 adenosine receptor. Circ Res 78: 627–634, 1996. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.78.4.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Starling EH. On the absorption of fluids from the connective tissue spaces. J Physiol 19: 312–326, 1896. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1896.sp000596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wei HS, Kang H, Rasheed ID, Zhou S, Lou N, Gershteyn A, McConnell ED, Wang Y, Richardson KE, Palmer AF, Xu C, Wan J, Nedergaard M. Erythrocytes are oxygen-sensing regulators of the cerebral microcirculation. Neuron 91: 851–862, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wei K, Le E, Bin JP, Coggins M, Jayawera AR, Kaul S. Mechanism of reversible (99m)Tc-sestamibi perfusion defects during pharmacologically induced vasodilatation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 280: H1896–H1904, 2001. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.4.H1896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Winkler EA, Sengillo JD, Bell RD, Wang J, Zlokovic BV. Blood-spinal cord barrier pericyte reductions contribute to increased capillary permeability. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 32: 1841–1852, 2012. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yemisci M, Gursoy-Ozdemir Y, Vural A, Can A, Topalkara K, Dalkara T. Pericyte contraction induced by oxidative-nitrative stress impairs capillary reflow despite successful opening of an occluded cerebral artery. Nat Med 15: 1031–1037, 2009. doi: 10.1038/nm.2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]