Abstract

Herpesviruses are enveloped viruses prevalent in the human population, responsible for a host of pathologies ranging from cold sores to birth defects and cancers. They are characterized by a highly pressurized, T (triangulation number) = 16 pseudo-icosahedral capsid encapsidating a tightly packed dsDNA genome1–3. A key process in the herpesvirus life cycle involves the recruitment of an ATP-driven terminase to a unique portal vertex to recognize, package, and cleave concatemeric dsDNA, ultimately giving rise to a pressurized, genome-containing virion4,5. Though this process has been studied in dsDNA phages6–9—with which herpesviruses bear some similarities—a lack of high-resolution in situ structures of genome-packaging machinery has prevented the elucidation of how these multi-step reactions, which require close coordination among multiple actors, occur in an integrated environment. Thus, to better define the structural basis of genome packaging and organization in the prototypical herpesvirus, herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), we developed sequential localized classification and symmetry relaxation methods to process cryoEM images of HSV-1 virions, enabling us to decouple and reconstruct hetero-symmetric and asymmetric elements within the pseudo-icosahedral capsid. Here we show in situ structures of the unique portal vertex, genomic termini, and ordered dsDNA coils in the capsid spooled around a disordered dsDNA core. We identify tentacle-like helices and a globular complex capping the portal vertex not observed in phages, indicative of adaptations in the DNA-packaging process specific to herpesviruses. Finally, our atomic models of portal vertex elements reveal how the five-fold-related capsid accommodates symmetry mismatch imparted by the dodecameric portal—long a mystery in icosahedral viruses—and inform possible DNA sequence-recognition and headful-sensing pathways involved in genome packaging. Our work represents the first fully symmetry-resolved structure of a portal vertex and first atomic model of a portal complex in a eukaryotic virus.

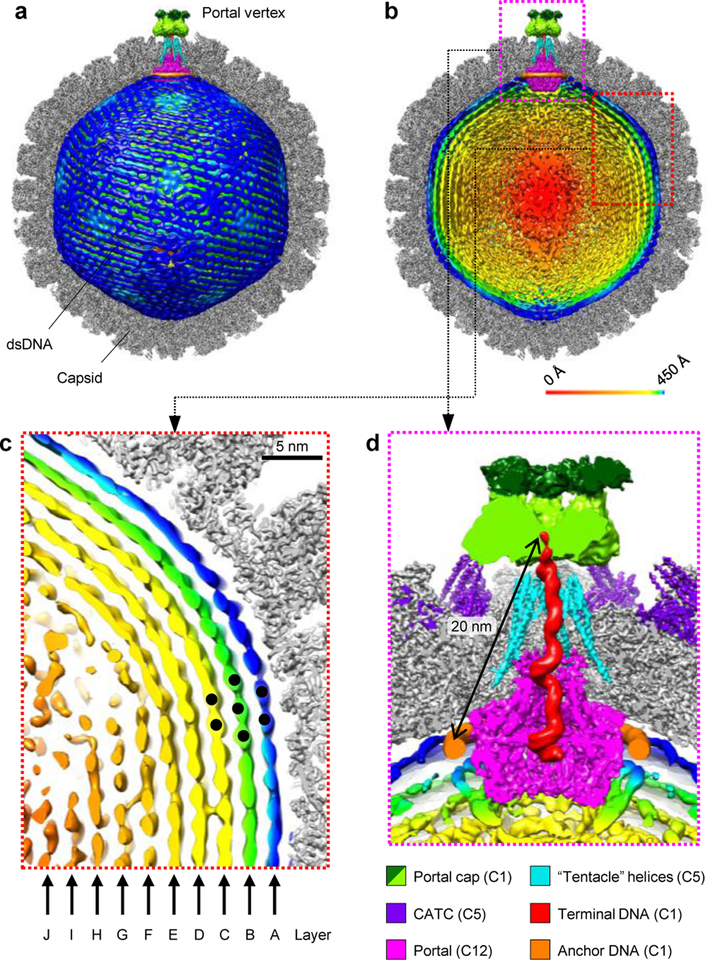

Applying our method of symmetry relaxation, we first sorted out the unique portal vertex from eleven penton vertices for each capsid, obtaining a 4.3-Å resolution structure of the portal vertex region with 5-fold (C5) symmetry (Extended Data Table 1; Extended Data Figs. 1–2). Subsequent rounds of sequential localized classification and sub-particle reconstruction yielded four other reconstructions: a 12-fold-symmetric (C12) reconstruction of the dodecameric portal (Extended Data Fig. 2a,e) and asymmetric (C1) reconstructions of the portal vertex region (Extended Data Fig. 2a,d), genome-containing virion (Extended Data Fig. 2a,f), and genome terminus in the DNA translocation channel (Extended Data Fig. 2b,g; Extended Data Table 1). Segmenting and aligning these reconstructions allow for the simultaneous visualization of all elements in the capsid-associated tegument complex (CATC)-decorated, genome-containing capsid (Fig. 1a; Supplementary Video 1).

Figure 1 |. Structures of the portal vertex and dsDNA genome.

a, Composite structure showing capsid (z-clipped), left-handed-spooled dsDNA genome, and portal vertex elements. b, Same view as (a), but with dsDNA (radially colored) z-clipped, revealing concentric shells of dsDNA density around a disordered core. c, Red inset from (b) reveals ten layers of near-crystalline, honeycomb-packed dsDNA. d, Magenta inset from (b) illustrates portal vertex structures. See Supplementary Video 1

Our C1 virion reconstruction reveals ordered, concentric dsDNA shells spooled in a left-handed manner around a disordered, ellipsoidal core of dsDNA (Fig. 1b). Up to ten concentrically equidistant layers are distinguishable, which we denote alphabetically from the outside in (Fig. 1c). As expected given the extreme space constraints within the capsid, inter- and intra-layer dsDNA strands exhibit a space-efficient honeycomb topology, consistent with indications of near-crystalline genomic packing in many dsDNA viruses10,11. Two other genomic structures are visible at the portal vertex. An asymmetric serpent-like density exhibiting major grooves and two distinctive right-handed toroidal regions occupies the portal vertex channel extending from the base of the portal to a portal vertex-capping density (Fig. 1d). On account of phage studies indicating one viral genomic end is so positioned as to poise the genome for ejection7,10 as well as the consensus that the last-packaged end is the first ejected12, we interpret this serpent-like density to be the last-packaged end of the HSV-1 genome and name it “terminal DNA”. In close proximity, a ringed density exhibits faint groove-like patterns and encircles the base of the dodecameric portal (Fig. 1d). Notably, this ringed density is exceptionally strong relative to adjacent concentric genomic density, indicative of an especially strong and perhaps specific association with the portal. Intriguingly, a previous study demonstrated that T4 phage’s genomic ends are consistently localized to maintain a 9-nm separation13. Given HSV-1 portal vertex contains ~11-nm long “tentacle helices” for which T4 has no analogues, the ~20-nm distance between the last-packaged end of terminal DNA and the portal-anchored ringed density suggest the ringed density to be the first-packaged anchoring segment of genome. We thus name this density “anchor DNA”.

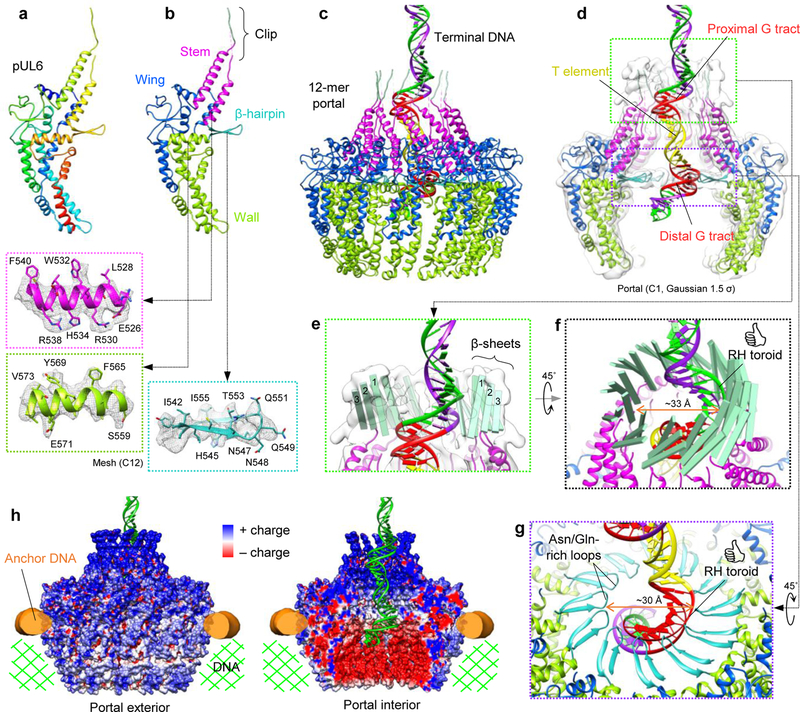

We next atomically modeled pUL6 using our C12 portal reconstruction (Fig. 2a; Extended Data Table 1). Structurally, each 676 amino acid (aa) pUL6 monomer consists of five domains—wing (aa. 33–62 and 150–271), stem (aa. 272–300 and 517–540), clip (aa. 301–516 [aa. 308–516 unmodeled]), β-hairpin (aa. 541–558), and wall (aa. 63–149 and 559–623)—and unresolved N- and C-terminal stretches of 32 and 53 residues, respectively (Fig. 2b; Extended Data Fig. 3; Supplementary Video 2). Twelve pUL6 monomers constitute the portal and are arranged such that their loop-rich wing domains form the outer periphery of the complex (Fig. 2c). The remaining stem, clip, β-hairpin, and wall domains line the interior of the portal’s DNA translocation channel (Fig. 2d).

Figure 2 |. pUL6 portal structure and interactions with dsDNA.

a, b, pUL6 atomic models colored in rainbow (red→blue: N-terminus→C-terminus) (a) and by domain (b). Insets show ribbon-and-stick models in mesh density (C12 portal reconstruction). c, Terminal DNA threads through a dodecameric portal comprising twelve pUL6 monomers. d, Z-clipped portal shown with C1 density (portal vertex reconstruction) Gaussian-filtered to 1.5 σ to show clip structure. Terminal DNA contains two right-handed toroidal regions each containing a conserved G tract, flanking a spacer T element. e, Green inset from (d) shows three-stranded β-sheets in each pUL6 monomer’s clip. f, Twelve three-stranded β-sheets form a right-handed-twisted turret in the clip, which interacts with proximal toroidal DNA. g, Purple inset from (d) shows twelve β-hairpins forming an apertured disk through which distal toroidal DNA passes. h, Electrostatic-surface renderings of the portal in a DNA environment. See Supplementary Videos 2 and 3.

Within this channel, aforementioned terminal DNA extends outwards, terminating within the bell-like portal cap (Fig. 1d). Taking this as the site of concatemeric cleavage, we used our C1 reconstruction of terminal DNA to generate a density-fitted 3D model of the final 67-base pair (bp) stretch of HSV-1 genome terminus, comprised of the cleavage site’s 3’ overhang, a single bp of directly-repeated elements (DR1) preceding the cleavage site, and the preceding 66-bp stretch of unique sequence (Ub)14–16 (Fig. 2d; Extended Data Fig. 4; Supplementary Video 3). Within the 66-bp Ub sequence, a stretch consisting of pac1 T element flanked by two short G tracts (GGGGGG and GGGGGGGG from pac1 proximal and distal GC elements of Ub, respectively) forms the major conserved motif at the termini of herpesvirus genomes, constituting the minimal sequence necessary for proper concatemeric cleavage17,18. Whereas both flanking G tracts are sequence critical, the T element tolerates substitutions, though not deletions, suggesting it may function as a regulatory spacer element15. Interestingly, proximal and distal G tracts in our fitted model map to the two right-handed toroidal densities of terminal DNA, which contact the portal channel’s interior walls, while the T element occupies a straight segment of density that exhibits no such contacts (Fig. 2d; Extended Data Fig. 4). Though reflecting a packaged state, our structure and model may be circumstantial evidence of sequence sensitivity of portal during genome packaging.

On the portal side, contact with terminal DNA’s proximal and distal toroids occur through clip and β-hairpin domains, both of which contain distinctive β-sheet motifs. Density of the clip is visible at lower thresholds in our C1 reconstructions, but disordered in our C12 reconstruction, indicating flexibility and/or deviation from strict 12-fold symmetry. While the full clip could not be modeled atomically, three β-strands visibly form a β-sheet in the clip above each monomer (Fig. 2e). Twelve sets of clip β-sheets give rise to a right-handed-twisted turret-like structure, which walls an upper narrow region of portal channel ~33-Å across at its narrowest, and where interactions with proximal toroidal DNA occur through the inner ring of β-strands (Fig. 2f). In contrast, β-hairpins are well-resolved in our C12 reconstruction, indicating a high degree of 12-fold symmetry. Each β-hairpin consists of two β-strands joined by an asparagine and glutamine-rich loop, which contacts distal toroidal DNA at several registers. Twelve β-hairpins extend perpendicularly towards the portal channel’s central axis, forming a disk-like structure with a central aperture ~30-Å in diameter that defines the portal channel’s narrowest point (Fig. 2g).

Unlike the clip and β-hairpin, stem and wall domains do not contact terminal DNA. Prominently, stem helices give rise to a left-handed corkscrew structure (distinctively shared with phage portals6 just beneath the clip (Fig. 2c; Extended Data Fig. 5). In tandem, helix-rich stem and wall domains appear to form the structural framework upon which the DNA-interacting clip and β-hairpin aperture are mounted. Indeed, force studies of ϕ29 portal demonstrated that these structural elements optimize the portal to withstand extreme mechanical stress, as might be imparted by translocating DNA19. Further evidence of portal’s highly optimized structure is apparent in an electrostatic-surface rendering calculated from our model (Fig. 2h). Generally, surfaces that interact with negatively-charged DNA are positively-charged. Particularly, a chamber-like space beneath the portal aperture is strongly negatively-charged, likely preventing interactions with newly translocated DNA that might otherwise affect proper genome compaction.

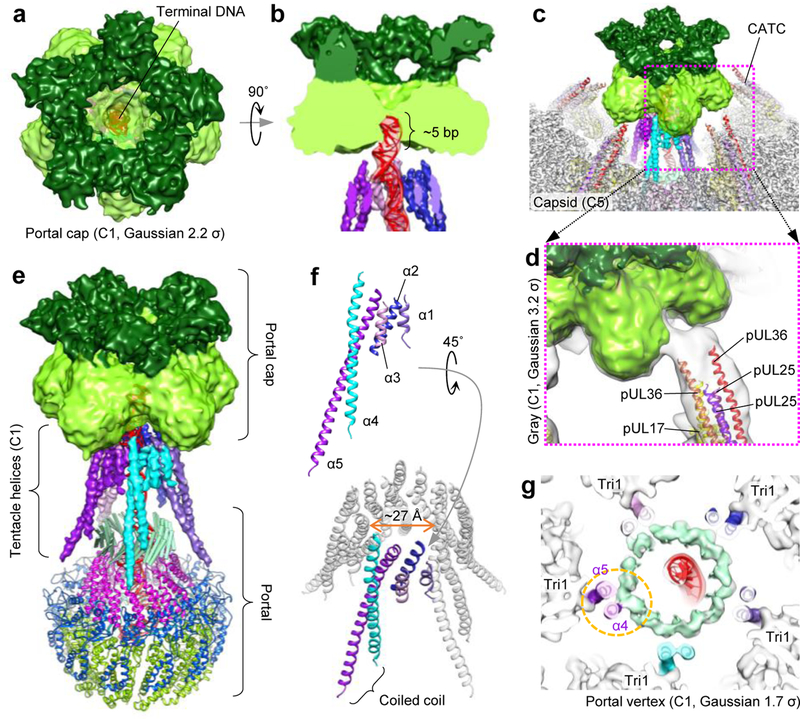

A pseudo-5-fold-symmetric portal cap emerges upon filtering our C1 portal vertex reconstruction (Fig. 3a). When aligned with terminal DNA, portal cap appears to anchor the last five bp of genome terminus (Fig. 3b). Interestingly, studies implicate CATC’s pUL25 in several DNA/portal vertex-related capacities, including direct binding of DNA20, DNA cleavage during packaging termination20, and interaction with nuclear pore complexes during viral genome uncoating21,22. Given that 1) five sets of pUL25 head domain dimers form pentameric complexes above penton capsomers23–25; 2) the volume and five dual-lobed appearance of portal cap density align with five pUL25 head dimers; and 3) connections between portal cap and CATC helix bundles are visible at lower thresholds (Fig. 3c–d), consistent with pUL25 head domain being flexibly-linked23,24; we posit the portal cap is a portal-vertex specific configuration of five sets of pUL25 dimers, which plugs the DNA translocation channel upon dissolution of actively-packaging terminase complex.

Figure 3 |. Tentacle helices and the portal cap.

a, b, Axial view (a) and z-clipped side view (b) of the portal cap, which plugs the DNA translocation channel and interacts with terminal DNA. Shades of green emphasize the density’s five dual lobes (C1 portal vertex reconstruction, Gaussian 2.2 σ). c, Portal cap with surrounding capsid/CATC density (C5 portal vertex reconstruction) and CATC atomic models. d, Connecting density between portal cap and CATC’s helix bundles are visible in C1 density (portal vertex reconstruction) Gaussian-filtered to 3.2 σ. e, Tentacle helices emanate upwards from the portal’s clip region, extending towards the portal cap. f, Poly-alanine models of tentacle helices. Five helices (α1-α5) constitute one set, and five sets encircle the DNA translocation channel. α4 and α5 form a coiled-coil motif. g, Slab view, axial perspective of the portal clip region shows emerging α4-portal clip connecting density at lower thresholds (C1 portal vertex reconstruction, Gaussian 1.7 σ). α5 also interacts with surrounding Tri1. See Supplementary Video 3.

Visible in both C1 and C5 structures of the portal vertex, five sets of tentacle-like helix densities ring the DNA translocation channel, extending from the portal’s clip to the portal cap (Fig. 3e). While unable to be modeled atomically, Cα bumps were sufficiently visible to permit poly-alanine traces for each helix set. Each set consists of three short helices (α1-α3) and two long helices (α4-α5) arranged in a classic coiled coil (Fig. 3f). Gradually decreasing the threshold in our C1 portal vertex reconstruction reveals increasingly connected density between the portal clip and α4 (Fig. 3g). Given that the portal’s missing clip residues (aa. 308–516) contain predicted long helical stretches interspersed with disordered residues (Extended Data Fig. 3)—in agreement with our density’s strong but unconnected helical densities—we postulate that tentacle helices belong to unmodeled residues of the clip. While this interpretation necessitates an at-first-glance outlandish 12-to-5-fold symmetry reorganization within the portal structure, dodecameric procapsid portal in P22 phage is known to expose a “quasi-5-fold symmetric surface” at the apex of its clip26, where pentameric terminase presumably interfaces. (HSV-1 portal association with terminase is known to require a leucine zipper in the unmodeled region of pUL6’s clip27.) Though the degree of 5-fold symmetry in our tentacle helices exceeds that of P22 procapsid portal, both examples underscore a tendency of plasticity, which one can imagine as necessary, in a symmetry-mismatched interfacing region.

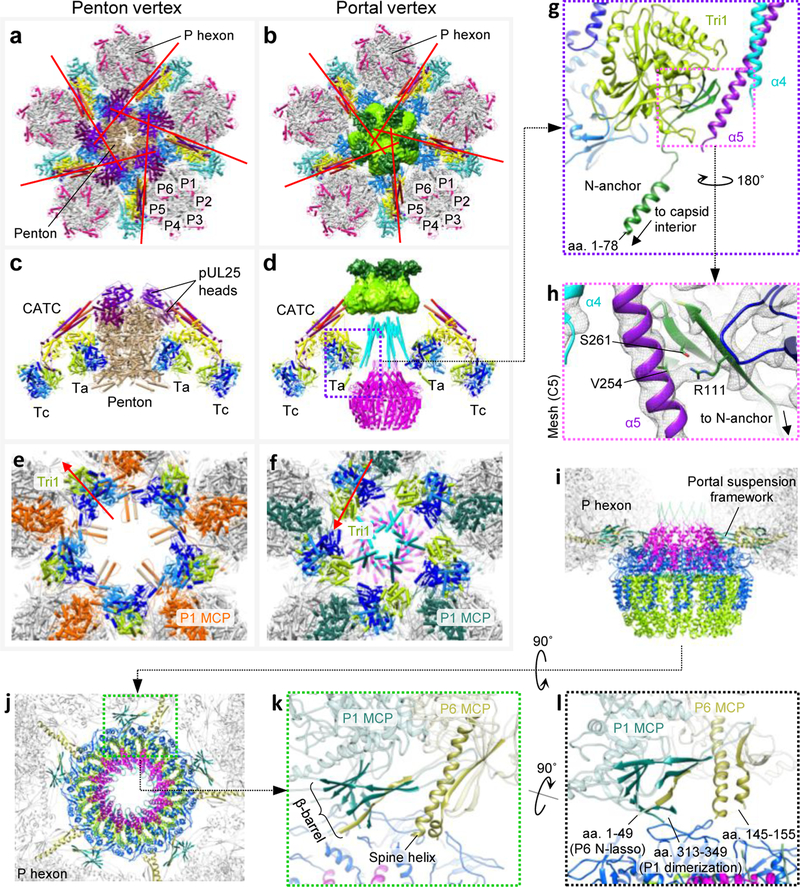

Finally, using our C5 reconstruction, we built atomic models of periportal SCP-decorated P hexon, Ta and Tc triplex, and CATC, enabling direct comparison of penton23 and portal vertices (Supplementary Video 4). Portal-specific structures aside—i.e., portal, tentacle helices, and portal cap—periportal CATC helix bundles are visibly oriented more perpendicularly to the vertex’s central axis (Fig. 4a–b), perhaps to facilitate a portal vertex-specific configuration of pUL25 head dimers required to form the portal cap. Furthermore, periportal Ta triplexes are rotated ~120° counter-clockwise about their respective centers, relative to peripenton Ta (Fig. 4c–f), such that periportal Ta Tri1’s capsid-penetrating N-anchor (of which an additional 24 residues are visible versus peripenton Ta Tri1’s [Extended Data Fig. 6]) is brought into direct contact with α5 of the tentacle helices through Tri1’s Arg111 (Fig. 4g–h). Our models also reveal a repurposing of MCP N-lasso and dimerization domains23 in the periportal floor, facilitating a “rigid framework-flexible contact” strategy to accommodate the symmetry-mismatched pseudo-5-fold-symmetric capsid and dodecameric portal (Fig. 4i–j; Extended Data Fig. 6). This rearrangement results in five sets of β-barrels occupying five portal-surrounding registers, which, together with five corresponding MCP spine helices, provide a structured framework from which short, flexible MCP elements extend to interface with portal’s loop-rich wing domains (Fig. 4k–l).

Figure 4 |. Capsid accommodations at the portal vertex.

a, b, Axial views of penton vertex (a) and portal vertex (b). Pipe-and-plank models are colored: pUL17, yellow; pUL36c, red and orange; pUL25, cherry and purple; triplex Ta, blue; triplex Tc, teal. Red lines denote CATC helix bundle orientations. c, d, Side views of penton vertex (c) and portal vertex (d) structures. Triplexes are colored: Tri1, lime; Tri2A, light blue; Tri2B, dark blue. e, f, Axial views of penton vertex with CATC and most of penton removed (e) and portal vertex with CATC/portal cap removed (f). Red arrows denote triplex orientations. Five penton dimerization domain helices forming “star helix” interactions23 with P1 MCPs are retained in (e), exemplifying an alternate domain-level conformation. g, Ta Tri1’s capsid-penetrating N-anchor runs into a three-stranded β-sheet (dark green), which contacts α5 of the tentacle helices. h, Mesh density (C5 portal vertex reconstruction) shows interactions between α5 and Tri1 through Arg111 (also Val254 and Ser261 at lower thresholds). i, j, Side (i) and axial (j) views show the dodecameric portal suspended by five sets of β-barrels and spine helices from surrounding P hexons. k, Enlarged view of a β-barrel and spine helix motif. l, Flexible elements extend from the β-barrel and spine helix at the capsid-portal interface. See Supplementary Video 4.

Our work here thus resolves previously averaging-obscured structures of the HSV-1 portal vertex and reveals an accommodation of symmetry mismatches through both intermolecular and intramolecular plasticity. Exceptionally, the projection of tentacle helices from the portal clip toward the terminase docking site/portal cap and α4/α5’s coiled-coil arrangement (widely implicated in propagating conformation changes28) are evocative of a signaling pathway. In light of evidence of sequence- and headful-sensing regulatory effects in genome packaging17,18,29,30, that α4 contacts the DNA-interacting region of portal clip and α5 interacts with the probe-like, capsid penetrating N-anchor of Tri1 provide tantalizing structural clues as to possible mechanistic bases of these modes of genome packaging regulation.

Methods

CryoEM sample preparation and imaging.

Sample preparation (HSV-1 virion) and cryoEM imaging have been described previously23. Briefly, virions of HSV-1 strain KOS were purified with density gradient centrifugation and frozen for cryoEM imaging. About 8,000 movies were collected with Leginon31 in a Titan Krios with energy filter and K2 direct electron detector. Each movie stack was drift-corrected32 and averaged to produce a corresponding micrograph. Defocus values for each micrograph were determined with CTFFIND333 and found to be in the range of −1 μm to −3 μm. A total of 45,445 particles (1,440×1,440 pixels and 1.03 Å/pixel) were picked manually with the boxer program in EMAN34 and boxed out from the micrographs with relion_preprocess in Relion35.

Icosahedral reconstruction and vertex sub-particle extraction.

At 1,440×1,440 pixels per individual particle image, the dataset required an unrealistic amount of computational resources and was too large to process with Relion. Thus, particles were binned 4 times using relion_preprocess and submitted for auto refinement with Relion2.135,36 imposing I3 symmetry. A Gaussian ball was used as an initial reference of the icosahedral reconstruction.

To perform symmetry relaxation, we expanded the icosahedral symmetry of the particles using relion_particle_symmetry_expand, generating 60 orientations for each particle. Each orientation has three Euler angles denoted as parameters within the Relion star files: rot (_rlnAngleRot), tilt (_rlnAngleTilt), and psi (_rlnAnglePsi). We then selected 12 orientations of 12 vertices from the 60 icosahedrally-related orientations as follows. First, we noted that because the icosahedral reconstruction was performed using I3 symmetry, there are 5 redundant orientations relative to each vertex that differ only in their rot angles (the first angle rotated about the z-axis). Given this observation, we then assigned 60 orientations into 12 groups with 5 orientations in each group. Importantly, the orientations within a group each have different rot angles, but the same tilt and psi angles. Lastly, we selected one orientation in each group as the orientation of a vertex, thereby generating one orientation for each vertex out of the 60 icosahedral-related orientations.

Previous study showed sub-particle reconstruction could solve structures of symmetry-mismatched parts of macromolecular complexes37. We then sought to extract sub-particles containing only vertices from the unbinned virion particles based upon the unique orientations previously selected. To do so, the two-dimensional Cartesian positions (x, y) of each sub-particle on their respective particle images were calculated using the following formula:

| (1) |

where d is the distance from the center of the reconstructed capsid to the vertex (in our case, d = 567 pixels) and C is the center of the 2D projection image (in our case, the projection center is at [720, 720], so C = 720 pixels). Because icosahedral reconstruction was performed with 4 times-binned particles, Ox and Oy are four times the offset distance (_rlnOriginX and _rlnOriginY in Relion) of each particle image relative to the projection center of the icosahedral reconstruction. Finally, sub-particles (384×384 pixels) containing only vertices, henceforth termed “vertex sub-particles,” were extracted from particle images based on their calculated positions using relion_preprocess without further normalization.

The resolution of the enormous virus particles was largely limited by the well-documented depth-of-focus problem38,39. To overcome this limitation, the defocus value of each vertex sub-particle was calculated based upon their locations with the following formula, where is the original defocus and Δz is the new defocus for each vertex:

| (2) |

Classification and refinement of vertex sub-particles with 5-fold symmetry.

To classify the portal vertex from the 12 vertices of each virus, we used Relion2.1 to perform 3D classification without rotational search (only ±4 pixels offset search) on the extracted vertex sub-particle, using the predetermined orientation of vertices while imposing 5-fold symmetry. The initial reference for classification was a 30Å reconstruction of the vertex sub-particles using relion_reconstruct. After 29 iterations, 4 classes were generated through 3D classification. 1 of the 4 classes exhibited apparent structural differences compared to the rest of the classes, which we deemed a portal vertex. This class contained 7.9% (~1/12) of the vertex sub-particles, consistent with exactly 1 out of 12 capsid vertices being a portal vertex. In rare cases, more than one vertex from each capsid were classified into the portal vertex class, likely due to the low quality of these particles and/or errors in classification. These redundant particles were removed per the following: if two or more vertices from the same virus particle were assigned to the portal vertex class, only the vertex sub-particle with the highest _rlnMaxValueProbDistribution score was retained. Upon removing all redundant particles, 42,857 vertex sub-particles remained and were deemed sub-particles of the portal vertex, henceforth referred to as “portal vertex sub-particles”. 3D auto refinement with imposed 5-fold symmetry was then performed on these portal vertex sub-particles with only a local search for orientation determination. The final resolution of the reconstruction was estimated with two independently refined maps from halves of the dataset with gold-standard FSC at the 0.143 criterion40 using relion_postprocess, and determined to be 4.3Å (Extended Data Fig. 2a). This reconstruction of the portal vertex contains a well-resolved 5-fold-arranged capsid, tegument, and 5-fold-symmetric DNA packaging-related structures, but a smeared portal dodecamer density due to symmetry mismatch.

Reconstructing the pUL6 dodecameric portal with 12-fold symmetry.

In the portal vertex sub-particles, we can further extract sub-particles that contain only the pUL6 dodecamer in order to reconstruct the 12-fold symmetric portal. The positions of pUL6 dodecamer on portal vertex sub-particles were determined using formula (1). The Euler angles (rot, tilt, and psi), Ox, and Oy are the orientation parameters of the portal vertex sub-particles; d is the distance from the center of the dodecamer to the center of the portal vertex sub-particle reconstruction (−126 pixels); and C is the center of 2D projection image of the portal vertex sub-particle (192 pixels). The sub-particles of pUL6 dodecamer (192×192 pixels), henceforth referred to as “dodecamer sub-particles” were then extracted with relion_preprocess using these parameters.

To obtain a reconstruction of the pUL6 dodecamer, we first expanded the 5-fold symmetry of the dodecamer sub-particles using relion_particle_symmetry_expand, generating five unique orientations for each dodecamer sub-particle. We then applied 3D classification with imposed C12 symmetry without orientation search, which after 100 iterations yielded 5 classes of similar structures with a rotational difference of approximately 72° in between classes. Ideally, each of the 5 expanded orientations of each dodecamer sub-particle should be assigned to exactly one of the five classes such that each class should contain 20% of the symmetry expanded sub-particles. After removing redundant particles as previously described—only particles with the highest _rlnMaxValueProbDistribution score was retained—the 5 classes contained 32,975, 39,939, 38,694, 36,102 and 34,722 particles, respectively. Since the 5 reconstructed classes were of the same quality upon visual inspection, we chose the class with the most abundant particles for 3D refinement with imposed 12-fold symmetry and limited to local orientation search. As before, the resolution of the pUL6 dodecamer was determined with relion_postprocess using gold-standard FSC at the 0.143 criterion40 (Extended Data Fig. 2a), indicating an overall resolution of approximately 5.6 Å for our 12-fold-symmetric reconstruction. However, a visual assessment of the region’s density quality and the local resolution estimate from ResMap41 indicates the majority of the portal itself to be within the 4–5 Å resolution range (Extended Data Fig. 2e), thereby allowing ab initio modeling. The lower resolution estimated by FSC may be due to unresolved, fairly flexible regions of the portal as well as other protein and nucleic acid densities that deviate from proper 12-fold symmetry.

Asymmetric reconstruction of the portal vertex and virion.

As the orientations determined from the previous classification of pUL6 dodecamer were selected from one of the five expanded orientations, these orientations can be used for 3D refinement of the portal vertex and whole virion without symmetry. Due to the large computational requirement for refinement of the whole virion, we performed this refinement using two times binned particles. The asymmetric auto refinement for both portal vertex sub-particles and virion particles were performed with a local search for orientations determined from the classification of the pUL6 dodecamer. The resolution of the portal vertex complex and the whole virion as determined by relion_postprocess are 5.4 Å and 6.2 Å, respectively (Extended Data Fig. 2a), according to the gold-standard FSC at 0.143 criterion40.

Asymmetric reconstruction of terminal DNA.

Despite obtaining an asymmetric reconstruction of the portal vertex structure with well-resolved high-resolution features, the terminal DNA within the portal channel remained smeared. Given that terminal DNA interacts with the portal, it could occupy any one of the twelve equivalent registers of the portal channel and the smeared DNA density is likely a result of undistinguished orientations of the terminal DNA among 12 possibilities.

To determine terminal DNA structure, we further expanded the orientations determined during the asymmetric portal vertex reconstruction with 12-fold symmetry using relion_particle_symmetry_expand. A cylindrical mask with a radius of 1.8 nm and a length of 18.5 nm encompassing the inner portal channel region was generated to facilitate 3D masked classification, which was performed without orientation search on the symmetry-expanded portal vertex particles (384×384 pixels). To enhance the signal-to-noise ratios of the classified structures, we classified the particles into six rather than twelve classes, setting the tau factor in Relion to 8042, given the small size of the mask region. After 72 iterations of classification, six classes were generated, from which we chose the class with the best structure of continuous DNA density. Redundant particles from this class were removed as previously described, after which we performed 3D refinement with local searching for orientations and with a mask covering both the portal and terminal DNA. Using relion_postprocess, we determined the resolution of our terminal DNA reconstruction to be 10.1 Å (Extended Data Fig. 2b), once again according to the gold-standard FSC at 0.143 criterion40.

Atomic modeling of capsid, CATC, and portal proteins.

Atomic models of peripentonal (i.e., non-portal vertex adjacent) MCP, Tri1, Tri2A, Tri2B, SCP, pUL17, pUL25, and pUL36 have been described previously23. Using our C5 map of the portal vertex region, we docked in peripentonal copies of the SCP-decorated P hexon, Ta triplex, and CATC in Chimera43. We then refined these models as necessary based on our density maps using the crystallographic program COOT44 to produce portal vertex-specific atomic models. Notably, periportal P1 and P6 MCP demonstrated substantial deviation from their peripenton counterparts in the MCP floor and required full re-traces in some regions. Periportal Ta triplex also exhibited a different orientation than peripenton Ta triplex, requiring manual rebuilding of some loop and interfacing regions. Periportal capsid and CATC models were then improved using real space refinement in Phenix45. Subsequent iterations of manual refinement in COOT and real space refinement in Phenix were applied to optimize the atomic models.

We traced and atomically modeled the pUL6 dodecameric portal ab initio using the C12 symmetry map and with the aid of secondary structure predictions obtained from Phyre246. Homologs of HSV-1 pUL6 from enterobacteria phage P22 (PDBs 5JJ1 and 5JJ3), bacteriophage SPP1 (PDB 2JES), and bacteriophage T4 (PDB 3JA7) were also used to help determine the correct trace (Extended Data Fig. 5). Side chain densities were consistently visible in the C12 map and served as reliable markers during registration; manually built models were then refined with real space refinement in Phenix. Final post-refinement validation statistics for all atomic models are tabulated in Extended Data Table 1. As we were unable to definitively identify the proteins that constituted the tentacle helices observed in between the dodecameric portal and portal cap, we were unable to register amino acid sequences for these densities. However, we built poly-alanine helices into these densities using observable C-alpha bumps through the C-alpha_Baton_Mode and Ca_Zone->Mainchain utilities in COOT.

Flexible fitting of terminal DNA.

To model the terminal DNA within the portal channel, we first generated a relaxed, straight segment of double-stranded B-form DNA with 90 repeating cytosine base pairs using the Ideal_DNA/RNA utility in COOT. After rigid body-fitting our ideal dsDNA into our asymmetric reconstruction of terminal DNA, we used Chimera43 to mask out density beyond the central cylindrical region of the portal channel. The resulting map and 90 bp ideal dsDNA model were then submitted to a Molecular Dynamics Flexible Fitting (MDFF)47 simulation session to flexibly fit the ideal dsDNA into the density map. Using the resulting dsDNA atomic model with improved density map fit, we determined that the length of visible dsDNA within the portal channel was approximately 67 bp long. Given that the last-packaged terminal DNA base pair must be oriented most distal from the capsid interior, we assigned this 67 bp long sequence to the last 67 bp of the HSV-1 concatemer and truncated and mutated our flexibly-fit dsDNA model accordingly. After manually adding an overhanging cytosine at the distal 3’ end (adjacent to the portal cap) as consistent with the concatemeric cleavage site, we used Color_Zone in Chimera43 to segment out a more accurate DNA density from our asymmetric terminal DNA reconstruction. This improved segmented map and our modified 67 bp model were then submitted for a second round of MDFF simulation to obtain our final terminal DNA model.

Data availability.

The five cryoEM maps have been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB) under accession numbers EMD-9860 (C5 portal vertex reconstruction), EMD-9861 (C1 portal vertex reconstruction), EMD-9862 (C12 portal reconstruction), EMD-9863 (C1 terminal DNA and portal vertex reconstruction), and EMD-9864 (C1 virion reconstruction). The atomic models for pUL6 and periportal capsid/CATC proteins have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) under accession numbers PDB-6OD7 and PDB-6ODM, respectively.

Extended Data

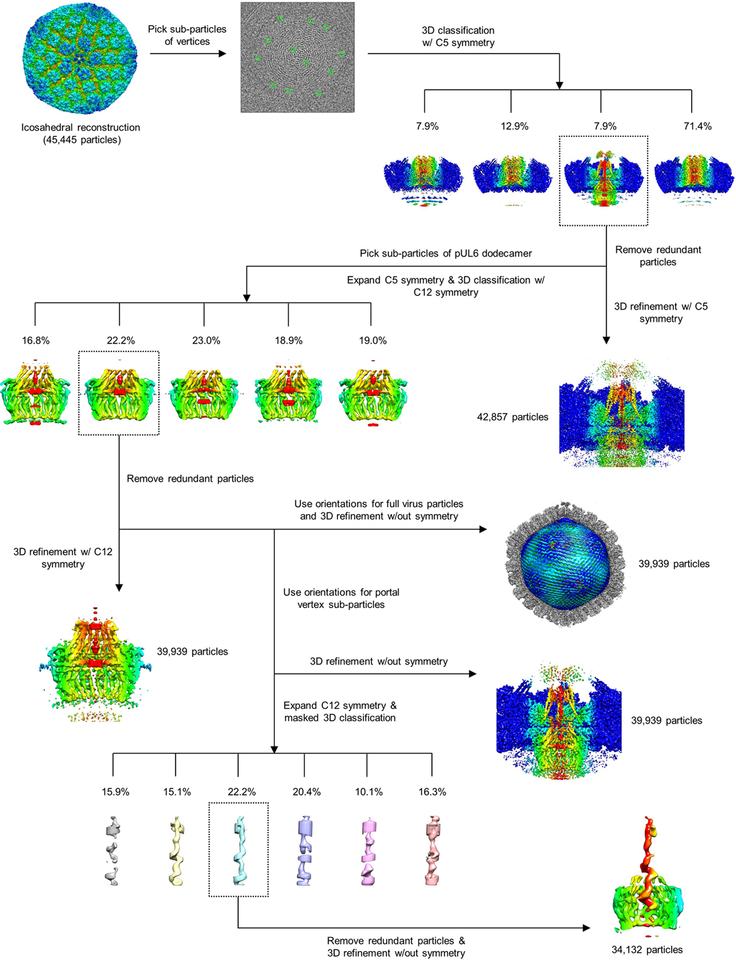

Extended Data Figure 1 |. Sequential localized classification and sub-particle reconstruction.

Flowchart illustrates the identification and resolution of symmetry-mismatched structures of the unique portal vertex.

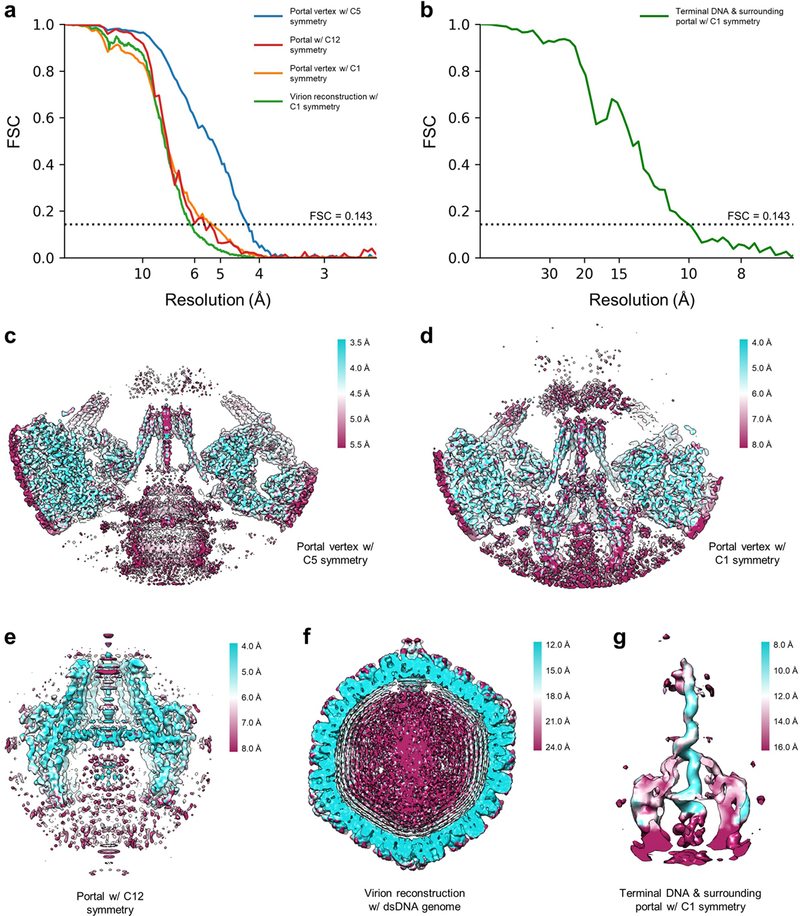

Extended Data Figure 2 |. Resolution verification.

a, b, Resolution of reconstructions determined by gold-standard FSC at the 0.143 criterion. c-g, Density slices colored by local resolution estimated from ResMap41.

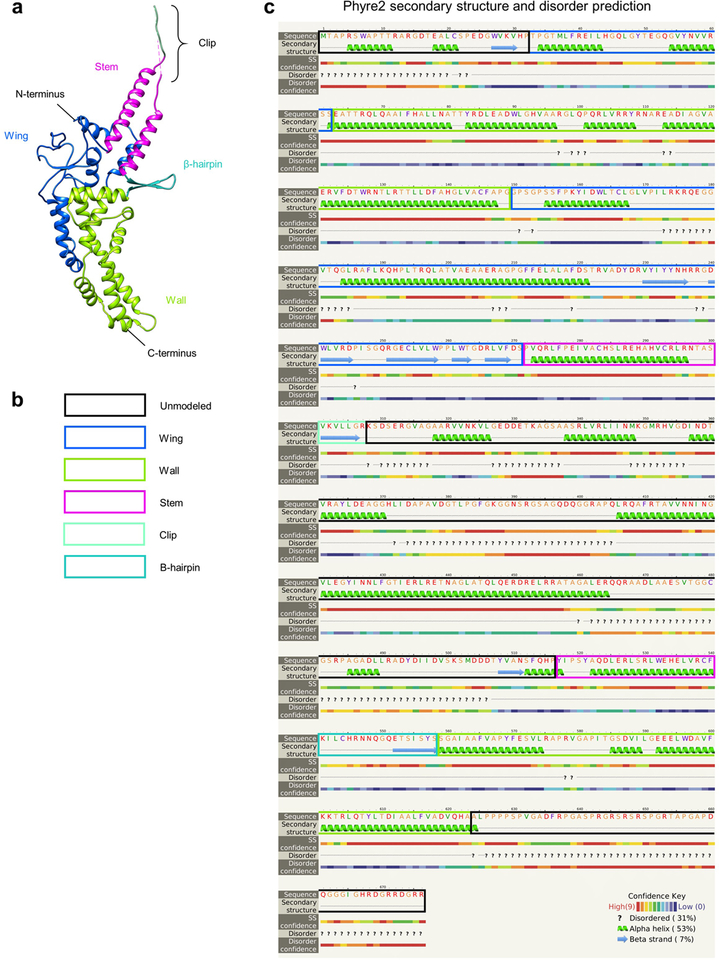

Extended Data Figure 3 |. pUL6 secondary structure and disorder prediction.

a-c, pUL6 monomer colored by domain for reference (a) and key (b) used to annotate a secondary structure and disorder prediction of pUL6 amino acid sequence obtained from Phyre246.

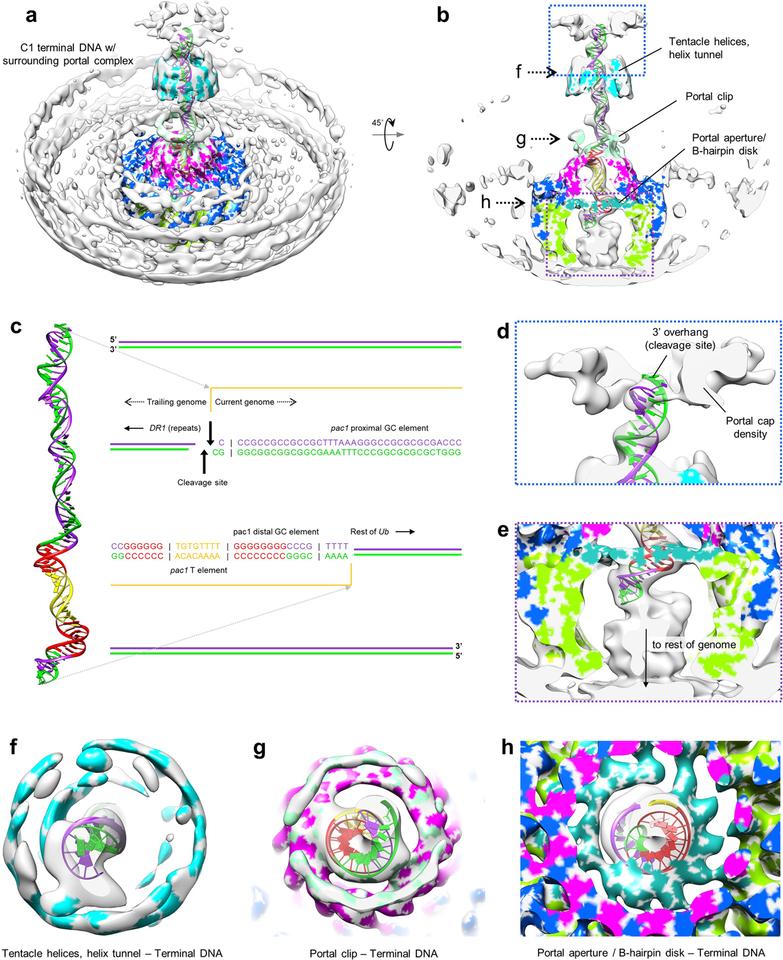

Extended Data Figure 4 |. Reconstruction of terminal DNA with surrounding portal.

a, b, C1 reconstruction of terminal DNA with surrounding portal color-zoned by pUL6 domains and tentacle helices. c, Sequence of terminal DNA mapped onto our fitted terminal DNA model. d, Enlarged view of terminal DNA’s trailing end, where concatemeric cleavage occurs. e, Enlarged view of terminal DNA’s disordered leading end, which extends down through the portal aperture towards the interior of the capsid. f-h, Slab views of C1 density showing terminal DNA’s interaction with tentacle helices (f), portal clip (g), and the portal aperture (h).

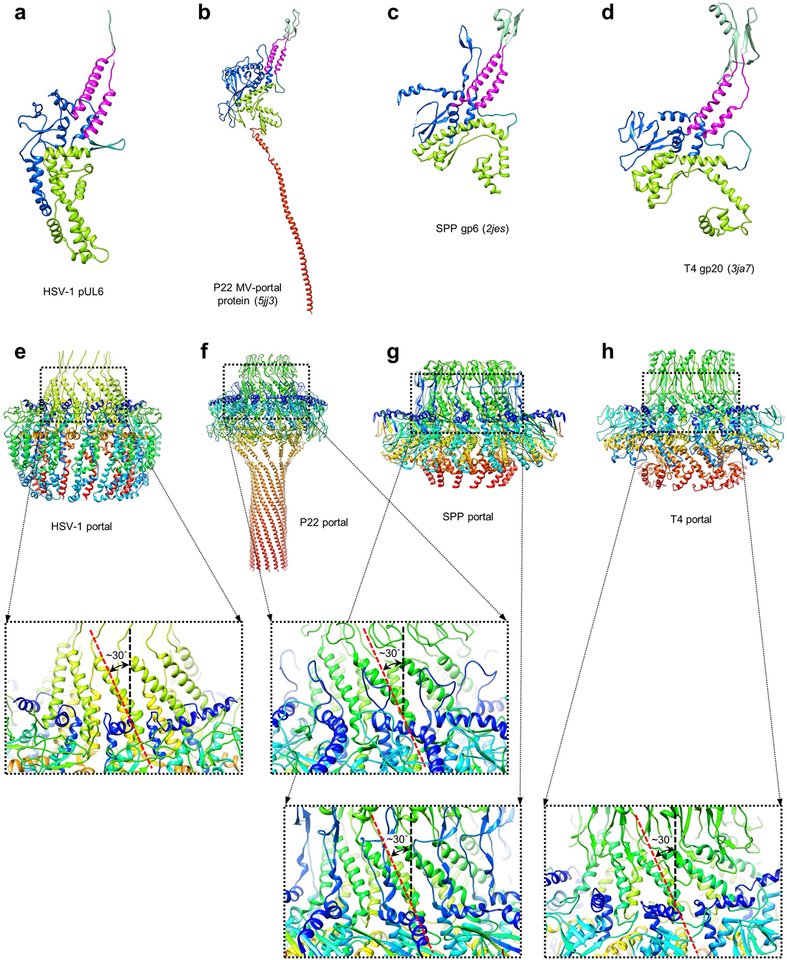

Extended Data Figure 5 |. pUL6 portal protein homologs.

a-d, HSV-1 pUL6 and pUL6 homologs colored analogously by pUL6 domain. e-h, HSV-1 pUL6 portal complex and homologs colored in rainbow (red→blue: N-terminus→C-terminus). Respective insets illustrate the conserved left-handed corkscrew of stem helices in the portal channel beneath the clip.

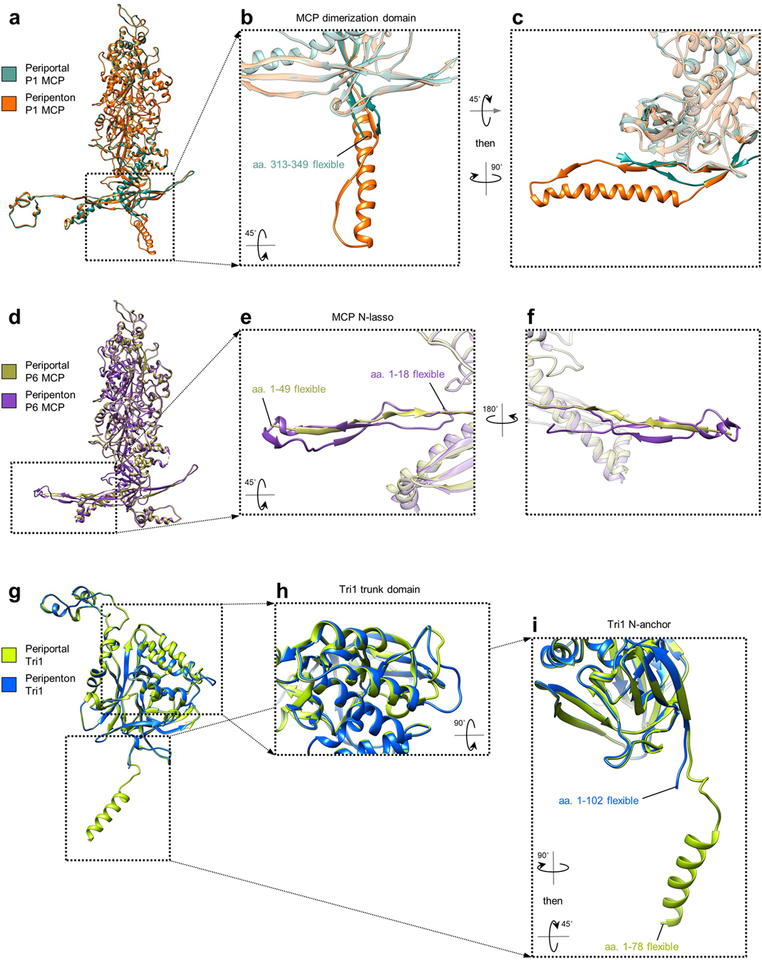

Extended Data Figure 6 |. Comparison of periportal and peripenton capsid proteins.

a-c, Comparison of periportal and peripenton P1 MCPs (a) reveal conformational differences in their dimerization domains (b, c). d-f, Comparison of periportal and peripenton P6 MCPs (d) reveal conformational differences in their N-lassos (e, f). g-i, Comparison of periportal and peripenton Tri1s (g) reveal differences in a trunk loop where periportal Tri1 interfaces with tentacle helices (h) and a visible N-anchor helix in periportal Tri1 (i).

Extended Data Table 1 |. CryoEM parameters and statistics.

Table shows cryoEM data collection, refinement, and validation statistics. Atomic models were iteratively refined using real-space refinement in Phenix45.

| C5 portal vertex reconstruction (EMDB-9860) (PDB-6ODM) | C12 portal reconstruction (EMDB-9862) (PDB-6OD7) | C1 virion reconstruction (EMDB-9864) | C1 portal vertex reconstruction (EMDB-9861) | C1 terminal DNA & portal vertex reconstruction (EMDB-9863) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection and processing | |||||

| Magnification | 14000 | 14000 | 14000 | 14000 | 14000 |

| Voltage (kV) | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 |

| Electron exposure (e−/Å2) | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 |

| Defocus range (μm) | −1 to −3 | −1 to −3 | −1 to −3 | −1 to−3 | −1 to−3 |

| Pixel size (Å) | 1.03 | 1.03 | 2.06 | 1.03 | 1.03 |

| Symmetry imposed | C5 | C12 | C1 | C1 | C1 |

| Initial particle images (no.) | 45,445 | 45,445 | 45,445 | 45,445 | 45,445 |

| Final particle images (no.) | 42,857 | 39,939 | 39,939 | 39,939 | 34,132 |

| Map resolution (Å) | 4.3 | 5.6 | 6.2 | 5.4 | 10.1 |

| FSC threshold | 0.143 | 0.143 | 0.143 | 0.143 | 0.143 |

| Map resolution range (Å) | 3.5–5.5 | 4–6 | 5–30 | 4–8 | 8–16 |

| Refinement | |||||

| Initial model used (PDB code) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Model resolution (Å) | |||||

| FSC threshold | |||||

| Model resolution range (Å) | |||||

| Map sharpening B factor (Å2) | 100 | 250 | |||

| Model composition | |||||

| Non-hydrogen atoms | -- | -- | |||

| Protein residues | 8,562 | 4,596 | |||

| Ligands | -- | -- | |||

| B factors (Å2) | |||||

| Protein | 144.05 | 157.06 | |||

| Ligand | -- | -- | |||

| R.m.s. deviations | |||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.005 | 0.008 | |||

| Bond angles (°) | 0.921 | 1.145 | |||

| Validation | |||||

| Mol Probity score | 1.69 | 1.89 | |||

| Clashscore | 5.66 | 9.73 | |||

| Poor rotamers (%) | 0.23% | 0.92% | |||

| Ramachandran plot | |||||

| Favored (%) | 94.45% | 94.46% | |||

| Allowed (%) | 5.29% | 5.54% | |||

| Disallowed (%) | 0.26% | 0.00% | |||

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements.

We thank Wei Liu for assistance in Molecular Dynamic Flexible Fitting. Our research has been supported in part by grants from the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2017YFA0505300 and No. 2016YFA0400900) and the US National Institutes of Health (GM071940/DE025567/AI094386). We acknowledge the use of instruments at the Electron Imaging Center for Nanomachines supported by UCLA and by instrumentation grants from NIH (1S10RR23057 and 1U24GM116792) and NSF (DBI-1338135 and DMR-1548924). We thank the Bioinformatics Center of the University of Science and Technology of China, School of Life Science, for providing supercomputing resources for this project.

Footnotes

Supplementary information. Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Author information. Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Bauer DW, Huffman JB, Homa FL & Evilevitch A Herpes virus genome, the pressure is on. J Am Chem Soc 135, 11216–11221, doi: 10.1021/ja404008r (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou ZH et al. Seeing the herpesvirus capsid at 8.5 Å. Science 288, 877–880. (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu XK, Jih J, Jiang JS & Zhou ZH Atomic structure of the human cytomegalovirus capsid with its securing tegument layer of pp150. Science 356, 1350-+, doi: 10.1126/science.aam6892 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heming JD, Huffman JB, Jones LM & Homa FL Isolation and characterization of the herpes simplex virus 1 terminase complex. J Virol 88, 225–236, doi: 10.1128/JVI.02632-13 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neuber S et al. Mutual Interplay between the Human Cytomegalovirus Terminase Subunits pUL51, pUL56, and pUL89 Promotes Terminase Complex Formation. J Virol 91, doi: 10.1128/JVI.02384-16 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao VB & Feiss M Mechanisms of DNA Packaging by Large Double-Stranded DNA Viruses. Annu Rev Virol 2, 351–378, doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-100114-055212 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang J et al. DNA poised for release in bacteriophage phi29. Structure 16, 935–943, doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.02.024 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mao H et al. Structural and Molecular Basis for Coordination in a Viral DNA Packaging Motor. Cell Rep 14, 2017–2029, doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.01.058 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harjes E et al. Structure of the RNA claw of the DNA packaging motor of bacteriophage Phi29. Nucleic Acids Res 40, 9953–9963, doi: 10.1093/nar/gks724 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang W et al. Structure of epsilon15 bacteriophage reveals genome organization and DNA packaging/injection apparatus. Nature 439, 612–616 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Booy FP et al. Liquid-crystalline, phage-like packing of encapsidated DNA in herpes simplex virus. Cell 64, 1007–1015 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newcomb WW, Cockrell SK, Homa FL & Brown JC Polarized DNA ejection from the herpesvirus capsid. J Mol Biol 392, 885–894, doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.07.052 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ray K, Ma J, Oram M, Lakowicz JR & Black LW Single-molecule and FRET fluorescence correlation spectroscopy analyses of phage DNA packaging: colocalization of packaged phage T4 DNA ends within the capsid. J Mol Biol 395, 1102–1113, doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.11.067 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mocarski ES & Roizman B Structure and role of the herpes simplex virus DNA termini in inversion, circularization and generation of virion DNA. Cell 31, 89–97 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tong L & Stow ND Analysis of herpes simplex virus type 1 DNA packaging signal mutations in the context of the viral genome. J Virol 84, 321–329, doi: 10.1128/JVI.01489-09 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Umene K Cleavage in and around the DR1 element of the A sequence of herpes simplex virus type 1 relevant to the excision of DNA fragments with length corresponding to one and two units of the A sequence. J Virol 75, 5870–5878, doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.13.5870-5878.2001 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McVoy MA, Nixon DE, Adler SP & Mocarski ES Sequences within the herpesvirus-conserved pac1 and pac2 motifs are required for cleavage and packaging of the murine cytomegalovirus genome. J Virol 72, 48–56 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang JB, Nixon DE & McVoy MA Definition of the minimal cis-acting sequences necessary for genome maturation of the herpesvirus murine cytomegalovirus. J Virol 82, 2394–2404, doi: 10.1128/JVI.00063-07 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar R & Grubmuller H Elastic properties and heterogeneous stiffness of the phi29 motor connector channel. Biophys J 106, 1338–1348, doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.01.028 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ogasawara M, Suzutani T, Yoshida I & Azuma M Role of the UL25 gene product in packaging DNA into the herpes simplex virus capsid: location of UL25 product in the capsid and demonstration that it binds DNA. J Virol 75, 1427–1436 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huffman JB et al. The C Terminus of the Herpes Simplex Virus UL25 Protein Is Required for Release of Viral Genomes from Capsids Bound to Nuclear Pores. J Virol 91, doi: 10.1128/JVI.00641-17 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pasdeloup D, Blondel D, Isidro AL & Rixon FJ Herpesvirus capsid association with the nuclear pore complex and viral DNA release involve the nucleoporin CAN/Nup214 and the capsid protein pUL25. J Virol 83, 6610–6623, doi: 10.1128/JVI.02655-08 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dai X & Zhou ZH Structure of the herpes simplex virus 1 capsid with associated tegument protein complexes. Science 360, doi: 10.1126/science.aao7298 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu YT et al. A pUL25 dimer interfaces the pseudorabies virus capsid and tegument. J Gen Virol 98, 2837–2849, doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.000903 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang J et al. Structure of the herpes simplex virus type 2 C-capsid with capsid-vertex-specific component. Nat Commun 9, 3668, doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06078-4 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lokareddy RK et al. Portal protein functions akin to a DNA-sensor that couples genome-packaging to icosahedral capsid maturation. Nat Commun 8, 14310, doi: 10.1038/ncomms14310 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang K, Wills E & Baines JD The putative leucine zipper of the UL6-encoded portal protein of herpes simplex virus 1 is necessary for interaction with pUL15 and pUL28 and their association with capsids. J Virol 83, 4557–4564, doi: 10.1128/JVI.00026-09 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Truebestein L & Leonard TA Coiled-coils: The long and short of it. Bioessays 38, 903–916, doi: 10.1002/bies.201600062 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rao VB & Black LW DNA Packaging in Bacteriophage T4 in Viral Genome Packaging Machines. (Plenum Press, 2005). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berndsen ZT, Keller N & Smith DE Continuous allosteric regulation of a viral packaging motor by a sensor that detects the density and conformation of packaged DNA. Biophys J 108, 315–324, doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.11.3469 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suloway C et al. Automated molecular microscopy: The new Leginon system. J Struct Biol 151, 41–60, doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.03.010 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li XM et al. Electron counting and beam-induced motion correction enable near-atomic-resolution single-particle cryo-EM. Nat Methods 10, 584-+, doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2472 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mindell JA & Grigorieff N Accurate determination of local defocus and specimen tilt in electron microscopy. J Struct Biol 142, 334–347, doi: 10.1016/S1047-8477(03)00069-8 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ludtke SJ, Baldwin PR & Chiu W EMAN: Semiautomated software for high-resolution single-particle reconstructions. J Struct Biol 128, 82–97, doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1999.4174 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scheres SHW RELION: Implementation of a Bayesian approach to cryo-EM structure determination. J Struct Biol 180, 519–530, doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2012.09.006 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scheres SHW A Bayesian View on Cryo-EM Structure Determination. J Mol Biol 415, 406–418, doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.11.010 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ilca SL et al. Localized reconstruction of subunits from electron cryomicroscopy images of macromolecular complexes. Nat Commun 6, 8843, doi: 10.1038/ncomms9843 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.DeRosier DJ Correction of high-resolution data for curvature of the Ewald sphere. Ultramicroscopy 81, 83–98 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang X & Zhou ZH Limiting factors in atomic resolution cryo electron microscopy: No simple tricks. J Struct Biol 175, 253–263, doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2011.05.004 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosenthal PB & Henderson R Optimal determination of particle orientation, absolute hand, and contrast loss in single-particle electron cryomicroscopy. J Mol Biol 333, 721–745, doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.07.013 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kucukelbir A, Sigworth FJ & Tagare HD Quantifying the local resolution of cryo-EM density maps. Nat Methods 11, 63–65, doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2727 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scheres SH Processing of Structurally Heterogeneous Cryo-EM Data in RELION. Methods Enzymol 579, 125–157, doi: 10.1016/bs.mie.2016.04.012 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pettersen EF et al. UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem 25, 1605–1612 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG & Cowtan K Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D 66, 486–501, doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adams PD et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D 66, 213–221, doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kelley LA, Mezulis S, Yates CM, Wass MN & Sternberg MJE The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat Protoc 10, 845–858, doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.053 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trabuco LG, Villa E, Mitra K, Frank J & Schulten K Flexible fitting of atomic structures into electron microscopy maps using molecular dynamics. Structure 16, 673–683, doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.03.005 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The five cryoEM maps have been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB) under accession numbers EMD-9860 (C5 portal vertex reconstruction), EMD-9861 (C1 portal vertex reconstruction), EMD-9862 (C12 portal reconstruction), EMD-9863 (C1 terminal DNA and portal vertex reconstruction), and EMD-9864 (C1 virion reconstruction). The atomic models for pUL6 and periportal capsid/CATC proteins have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) under accession numbers PDB-6OD7 and PDB-6ODM, respectively.