Abstract

Background

We encounter interstitial lung disease (ILD) patients with psoriasis. The aim of this case series was to examine clinical and radiographic characteristics of patients with concomitant psoriasis and ILD.

Methods

This is a retrospective review of our institutional experience of ILD concomitant with psoriasis, from the database in the Advanced Lung/Interstitial Lung Disease Program at the Mount Sinai Hospital. Out of 447 ILD patients, we identified 21 (4.7%) with antecedent or concomitant diagnosis of psoriasis. Clinical, radiographic, pathological, and outcome data were abstracted from our medical records.

Results

Median age was 66 years (range, 46–86) and 14 (66.7%) were male. Thirteen (61.9%) had not previously or concomitantly been exposed to immunosuppressive therapy directed against psoriasis. Two (9.5%) ultimately died. Clinical diagnosis of ILD included idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, 11 (52.4%); nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), 2 (9.5%); cryptogenic organizing pneumonia, 2 (9.5%); chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis, 2 (9.5%); and the others, while radiographic diagnosis included usual interstitial pneumonia pattern, 9 (42.9%); NSIP pattern, 6 (28.6%); organizing pneumonia pattern, 4 (19.0%); hypersensitivity pneumonitis pattern, 2 (9.5%); and the others.

Conclusions

We report 21 ILD cases with antecedent or concomitant diagnosis of psoriasis. Further prospective studies are required to determine the association between ILD and psoriasis.

1. Introduction

Psoriasis commonly presents with sharply defined erythematous plaques with overlying silvery scales. The scalp, elbow extensors, knees, and back are common locations for plaque psoriasis [1]. This hyperproliferative state is characterised by increased numbers of epidermal stem cells and cells undergoing DNA synthesis, shortened keratinocyte cell cycle time, and decreased epidermal turnover time [1]. Psoriatic arthritis is an inflammatory arthritis/synovitis that occurs in 25% of patients with psoriasis; it is a distinct clinical entity characterised by involvement of the distal interphalangeal joints of the hands and feet as well as the absence of rheumatoid factor [2]. Previous studies demonstrate that psoriasis is associated with diabetes mellitus [3], arterial hypertension [4], obesity [5], dyslipidaemia [6], cardiovascular disease [7], and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease [8].

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is defined as any lung disease occurring in the parenchymal interstitium (i.e., the alveolar wall or alveolar septa) or loose-binding connective tissue (i.e., the peribronchovascular sheath, interlobular septa, or pleura) [9]. Type 17 helper T (T(H)17) cells were reported to be one of the common pathways which contribute to alveolitis and enhance cytokine production in pulmonary fibroblasts. T(H)17 cells are also the hallmark of pathogenesis in psoriasis; therefore, the coexistence of ILD and psoriasis is worth exploring on the basis of possibly shared underlying immunologic pathways. A previous small study (N = 50) in the Tucson VA Hospital showed that pulmonary fibrosis was not more common in a population of patients with psoriasis than would be expected in a control VA population [10]. ILD is occasionally reported in patients with psoriasis, most cases of which have been reported previously as drug-induced pneumonitis secondary to concomitant use of immunosuppressants. However, in the ILD program at Mount Sinai Hospital, we frequently encounter ILD patients with a concomitant diagnosis of psoriasis, who had been free from immunosuppressive therapy directed against psoriasis. In this pilot case series, we reported our experience with ILD in patients with psoriasis to assess their clinical features and outcomes.

2. Methods

2.1. Patients

This case series was a retrospective review of our institutional experience with ILD concomitant with psoriasis at the Advanced Lung/Interstitial Lung Disease Program at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York. The medical records of 447 consecutive patients who visited the ILD program were reviewed retrospectively. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients who visited the Advanced Lung/Interstitial Lung Disease Program from October 2009 through September 2015, (2) age ≥ 18 years old, (3) a diagnosis of ILD, and (4) diagnosed with either psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis by dermatologists. Patients who had ILD associated with sarcoidosis were excluded. Of the 447 patients who visited the ILD program, 21 (4.7%) had a diagnosis of both ILD and psoriasis. All findings on computed tomography (CT) were reviewed by a board-certified radiologist (MS), and pathological specimens were reviewed by a board-certified pathologist (MBB). All clinical and outcome data of the 21 patients were abstracted from our medical records.

The following data were extracted: age, sex, symptoms, time from diagnosis of ILD (months) prior to initial enrolment, time from diagnosis of psoriasis (years), comorbid illnesses (i.e., other autoimmune diseases, gastroesophageal reflux, and pulmonary hypertension (PH)), body mass index, smoking history, New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class, medications, home oxygen therapy, pulmonary function test, 6-minute walking test, clinical diagnosis of ILD, CT findings, pathological results, and follow-up information. We defined both radiographic “definitive UIP pattern” and “probable UIP pattern” as “UIP pattern” in the present study. Echocardiographic evidence of possible PH was defined as estimated pulmonary artery systolic pressure >40 mmHg.

Our ILD program involves weekly multidisciplinary discussions with board-certified pulmonary physicians (AM, DS, and MLP), radiologist (MS), and pathologist (MBB), who make clinical diagnoses based on the clinical, radiographic, and pathological findings of each ILD case.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Mount Sinai Hospital (HS#: 17-01088, GCO#1: 17-2284 (0001) ISMMS, IDEATE #IRB-17-02560).

2.2. Statistical Methods

Descriptive analyses were performed. Continuous variables are presented as median and range, and categorical variables are presented as frequency and percentage unless stated otherwise.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics and Clinical and Pathological Presentation

The characteristics of the 21 patients with ILD and an antecedent or concomitant diagnosis of either psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis are shown in Table 1; their demographic and clinical features are shown in Table 2. Median patient age was 66 years (range, 46–86 years). There were 14 (66.7%) men and 7 women. There were 15 (71.4%) current or former smokers. The most common symptom on presentation was “cough,” followed by “dyspnea on exertion.” The median time from ILD diagnosis prior to initial enrolment was 24 months (range, 0–132 months), while the median time from psoriasis diagnosis prior to the enrolment was 2 years (range, 1–22 years). Most patients maintained relatively good performance status (NYHA I/II: 19 (90.5%)).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Overall n = 21 median (range) n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Demographic | |

| Age (years) | 66 (46, 86) |

| Male | 14 (66.7) |

| Clinical | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.9 (20.8, 34.5) |

| Smoking | 15 (71.4) |

| Home oxygen therapy | 5 (23.8) |

| Time from diagnosis of ILD (months) | 27 (0, 36) |

| Time from diagnosis of psoriasis (years) | 2 (1, 45) |

| Family history of psoriasis | 1 (4.8) |

| PH or possible PH | 9 (42.9) |

| Gastroesophageal reflux | 10 (47.6) |

| NYHA functional class I/II/III/IV | 5/14/2/0 |

| Pulmonary function test, % predicted | |

| FVC | 69 (38, 89) |

| FEV1.0/FVC | 80 (71, 104) |

| DLco | 47 (17, 95) |

| FEV1.0 | 73 (42, 95) |

| 6-minute walking test (m) | 280 (104, 579) |

| Lung biopsy | 5 (23.8) |

ILD: interstitial lung disease; NYHA: New York Heart Association; PH: pulmonary hypertension.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical features of 21 ILD patients with psoriasis.

| Patient | Age/sex | Arthritis | Autoimmune disease/marker | Prior/concomitant immunosuppressants | Clinical diagnosis | Radiographic diagnosis | ILD stage∗ | Pathology | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 68/M | No | SSA (+)∗∗ | No | IPF | UIP pattern# | Limited | Not obtained | Survived at 3 months |

| 2 | 66/M | No | No | No | RBILD/DIP | RBILD/DIP pattern | Limited | RBILD/DIP pattern | Survived at 34 months |

| 3 | 52/M | Yes | PM/DM CREST | No | CTD-ILD | NSIP pattern | Limited | OP/EP pattern | Survived at 56 months |

| 4 | 80/M | No | No | No | COP | OP pattern | Limited | OP/EP pattern | Survived at 13 months |

| 5 | 78/M | No | No | No | IPF | UIP pattern | Limited | Not obtained | Survived at 51 months |

| 6 | 46/M | Yes | No | MTX, etanercept | IPF/IgG4-related lung disease | NSIP/OP pattern | Limited | Not obtained | Survived at 11 months |

| 7 | 58/F | Yes | No | Hydroxychloroquine sulfate, MTX, infliximab | NSIP | NSIP/OP pattern | Limited | Not obtained | Survived at 3 months |

| 8 | 76/M | No | No | No | IPF | UIP pattern | Extensive | Not obtained | Unknown |

| 9 | 49/M | No | No | No | IPF | UIP pattern | Limited | Not obtained | Survived at 23 months |

| 10 | 60/M | No | ANCA (+)∗∗∗ | No | CHP | OP/HP pattern | Extensive | Early UIP/OP | Survived at 8 months |

| 11 | 62/M | No | No | No | NSIP | NSIP pattern | Extensive | Not obtained | Survived at 48 months |

| 12 | 81/F | No | No | 6-MP | COP | NSIP pattern | Limited | Not obtained | Died at 13 months |

| 13 | 80/F | No | ANCA (+)∗∗∗ | Azathioprine | IPF | UIP pattern | Limited | Not obtained | Survived at 1 month |

| 14 | 63/M | No | No | No | IPF | UIP pattern | Limited | Not obtained | Survived at 46 months |

| 15 | 48/M | No | No | No | IPF | NSIP pattern | Extensive | Not obtained | Survived at 18 months |

| 16 | 53/F | No | No | No | Mitral valve lung disease | Reticular and GGO in lung bases with innumerable small nodules | Limited | Not obtained | Survived at 17 months |

| 17 | 67/M | No | No | MTX, etanercept | IPF | UIP pattern | Extensive | Not obtained | Survived at 4 months |

| 18 | 62/F | No | No | Chemotherapy for breast cancer | IPF | UIP pattern | Extensive | Not obtained | Survived at 12 months |

| 19 | 86/F | No | No | No | IPF | UIP pattern | Extensive | Not obtained | Died at 8 months |

| 20 | 79/M | No | No | Chemotherapy for lymphoma | Unspecific | Mosaic attenuation | Limited | Not obtained | Survived at 53 months |

| 21 | 69/F | Yes | No | MTX, etanercept sulfasalazine | CHP | HP pattern | Limited | Not obtained | Survived at 4 months |

ANA: antinuclear antibody, ANCA: antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, CHP: chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis, COP: cryptogenic organizing pneumonia, CTD-ILD: connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease, EP: eosinophilic pneumonia, F: female, GGO: ground glass opacities, HP: hypersensitivity pneumonitis, IPF: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, M: male, MP: mercaptpurine, MTX: methotrexate, NSIP: nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, OP: organizing pneumonia, PE: pulmonary embolus, PM/DM: polymyositis/dermatomyositis, RBILD/DIP: respiratory bronchiolitis-associated interstitial lung disease/desquamative interstitial pneumonia, SSA: SS-A antibody, and UIP: usual interstitial pneumonia. ∗A staging system, originally proposed for ILD with systemic sclerosis, by Goh et al. [11]. ∗∗Patient had a mild elevation of serum SS-A (1.20 AI) but lacked sicca symptom and other symptoms suggestive of underlying autoimmune disease (i.e., arthralgia, digital fissuring/ulceration, and Raynaud's phenomenon). ∗∗∗Patients had positivity of serum ANCA but lacked clinical symptom suggestive of underlying systemic vasculitis (i.e., skin rash, alveolar haemorrhage, and glomerulonephritis). #We defined both radiological “definitive UIP pattern” and “probable UIP pattern” as “UIP pattern” in the present study.

The clinical diagnoses after multidisciplinary discussions were as follows: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), 11 (52.4%); nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), 2 (9.5%); cryptogenic organizing pneumonia, 2 (9.5%); chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis, 2 (9.5%); and the others. The median FVC% predicted was 69 (range, 38–89), and DLco% predicted was 47 (range, 17–95). Nine (42.9%) patients had PH or possible PH diagnosed by either echocardiography or right heart catheterization. One (4.8%) patient had other concomitant autoimmune diseases (polymyositis/dermatomyositis/CREST syndrome), and 3 others (14.3%) were positive for serum markers without a definitive diagnosis of collagen vascular disease. Thirteen (61.9%) had not previously or concomitantly been exposed to immunosuppressant, whereas 8 (38.1%) had been exposed. The most common immunosuppressants included methotrexate (n = 4), followed by etanercept (n = 3). Of the 4 patients who underwent lung biopsy, including 2 who underwent video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) and 2 who underwent transbronchial lung biopsy (TBLB), 2 patients had organizing pneumonia (OP), 1 had respiratory bronchiolitis-associated interstitial lung disease/desquamative interstitial pneumonia (RBILD/DIP) pathologic patterns, and 1 had early UIP pattern.

3.2. Radiographic Findings

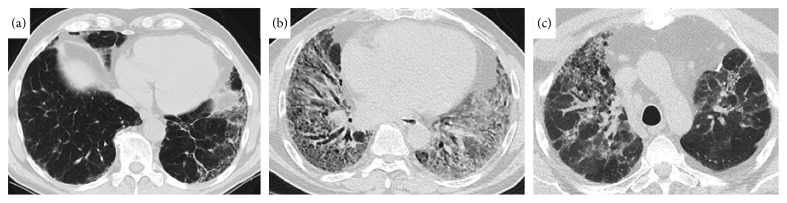

All patients had CT for current review from the time of their diagnostic evaluation. Radiographic diagnoses were as follows: usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) pattern, 9 (42.9%, Figure 1(a)); NSIP pattern, 6 (28.6%, Figure 1(b)); organizing pneumonia pattern, 4 (19.0%); hypersensitivity pneumonitis pattern, 2 (9.5%, Figure 1(c)); and the others (Table 2). Seven patients (33.3%) had an extensive disease in CT, based on a staging system originally proposed for ILD with systemic sclerosis, by Goh et al. [11].

Figure 1.

(a) Radiographic probable UIP pattern (Patient 1). (b) Radiographic NSIP pattern (Patient 11). (c) Radiographic HP pattern (Patient 10). HP: hypersensitivity pneumonitis, NSIP: nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, and UIP: usual interstitial pneumonia.

3.3. Treatments and Outcomes

Three patients with IPF started antifibrotic agents (pirfenidone, 2; nintedanib, 1) during follow-up, and 4 patients (COP, 2; IPF, 1; NSIP, 1) started additional anti-inflammatory agents (prednisone, 2; mycophenolate mofetil, 2; azathioprine, 1). During follow-up, most patients continued to have stable pulmonary function, as shown by mild worsening of predicted FVC% per year (range, −5.7% to +18%/year). One patient eventually died from pneumonia and 1 from an unknown cause (found in cardiac arrest at home).

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, the present case series is the first to fully investigate the clinical and radiographic features of ILD with psoriasis. Of 447 patients who visited the ILD program in a referral practice, 21 ILD patients (4.7%) had concomitant psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis, and most of them (63.6%) had not been previously or concomitantly exposed to immunosuppressants. In previous studies (Table 3), the following immunosuppressants were associated with pneumonitis in patients with psoriasis: methotrexate [32], infliximab [26], fumaric acid ester [25], leflunomide [24], gold [18], and sulfasalazine [17]. In contrast, only 3 cases of ILD without concomitant or prior use of immunosuppressants have been reported. Messina et al. [21] report a case of psoriasis with a pathologically OP pattern, even though concomitant cytomegalovirus infection might have induced pneumonitis; therefore, the causality is unclear in this case. Meanwhile, Hiki et al. report a case of severe IgA nephropathy associated with psoriatic arthritis and idiopathic interstitial pneumonia [13]. Third, Gupta and Espiritu showed a case of worsening exertional dyspnea, found to have NSIP pattern in CT chest, and subsequently developing punch biopsy-proven psoriasis [29]. Our institutional experience with 21 ILD/psoriasis cases, most of which had been without concomitant or prior use of immunosuppressants, potentially suggests a possible direct association between these 2 different disease entities. The previous small study (N = 50) in the Tucson VA Hospital failed to reveal their correlation, and perhaps, this might have been attributed to the underpowered nature of the study (i.e., insufficient sample size) [10]. Therefore, prospective studies with sufficient sample size, involving careful assessment with pulmonary function testing and high-resolution CT in a psoriasis cohort, are imperative for accurately determining the prevalence of ILD and assessing their possible association.

Table 3.

Summary of previous reports on interstitial lung disease in conjunction with psoriasis.

| Reference | Age/sex | Arthritis | Concomitant autoimmune disease | Prior or concomitant immunosuppressant use | Radiological finding | Pathology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kaplan and Waite [12] | 70/M | No | No | MTX | Interstitial fibrosis with honeycombing | Not specified |

|

| ||||||

| Guzman [10] | 54/M | Yes | No | A variety of anti-inflammatory drugs | Considerable loss of volume in both upper lobes with advanced fibrosis | Notable interstitial fibrosis with dilated bronchi and bronchioles |

|

| ||||||

| Hiki et al. [13] | 23/M | Yes | IgA nephropathy | No | A reticular or reticulonodular pattern with bilateral pneumonic consolidation | Severe interstitial pneumonia |

|

| ||||||

| Salaffi et al. [14] | 62/M | Yes | No | Gold salts, etretinate, sulfasalazine, MTX | Bilateral and diffuse interstitial infiltrates, broader in the upper right lobe | Not specified |

|

| ||||||

| Kawakami et al. [15] | 50/F | No | Polymyalgia rheumatic | Not specified | Bilateral basilar reticulonodular shadows | NSIP |

|

| ||||||

| Ameen et al. [16] | 53/F | No | No | MTX, cyclosporin | Widespread changes in the mid- and upper zones with thickening and nodularity of the interlobular septae | Not specified |

|

| ||||||

| Woltsche et al. [17] | 78/M | Yes | No | Sulfasalazine | Small nodular densities over both lungs | Lymphoplasmocytic interstitial infiltration |

|

| ||||||

| Manero Ruiz et al. [18] | Not specified | Yes | No | Gold salts | Not specified | Not specified |

|

| ||||||

| Tokunaga et al. [19] | 56/M | No | No | Sho-saiko-to (Chinese herbs) | Microcystic lesions, reticular shadows, and traction bronchiectasis underneath the pleura at the back of both lower lobes | UIP |

|

| ||||||

| Abou-Samra et al. [20] | 35/F | No | No | MTX, cyclosporin, acitretin | Bilateral interstitial infiltrate and alveolar filling of the right pulmonary base | Not specified |

|

| ||||||

| Abou-Samra et al. [20] | 61/F | No | No | Acitretin, MTX | Bilateral interstitial infiltrate of the pulmonary bases | Not specified |

|

| ||||||

| Messina et al. [21] | 63/F | No | No | No | Diffuse interstitial infiltrates | Obliteration of the alveolar spaces connective tissue |

|

| ||||||

| El-Hag et al. [22] | Not specified | No | No | Infliximab, azathioprine | Not specified | Not specified |

|

| ||||||

| Penizzotto et al. [23] | 51/F | No | No | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified |

|

| ||||||

| Lee and Hutchinson [24] | 52/F | Yes | No | MTX, leflunomide, sulfasalazine | Ground glass appearance throughout the lung fields | Not specified |

|

| ||||||

| Deegan et al. [25] | 49/M | No | No | Fumaric acid esters | Bilateral, mostly peripheral foci of consolidation with air bronchograms | Pattern of organizing pneumonia |

|

| ||||||

| Leger et al. [26] | 68/F | No | No | Infliximab | Bilateral basal interstitial infiltrates with pleural effusion | Not specified |

|

| ||||||

| Bale and Chee [27] | 67/M | No | No | Infliximab | Patchy alveolar and ground glass infiltrates | Not specified |

| Kakavas et al. [28] | 64/M | No | No | Infliximab | Bilateral ground glass and interstitial infiltrates | Not specified |

|

| ||||||

| Gupta and Espiritu [29] | 43/F | No | No | No | NSIP pattern | Not specified |

|

| ||||||

| Miyachi et al. [30] | 71/F | No | No | Etretinate, cyclosporin, methotrexate | Basal interstitial ground glass opacities | Not specified |

|

| ||||||

| Deng et al. [31] | 30/F | Yes | Rheumatoid arthritis | Prednisone, iguratimod, total glucosides of peony | Not specified | Not specified |

F: female, M: male, MTX: methotrexate, NSIP: nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, and UIP: usual interstitial pneumonia.

The relation between psoriasis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was recently demonstrated [33]. Due to its possible autoimmune-related pathogenesis, psoriasis-related immune dysfunction could lead to an abnormal immunologic response in the lung parenchyma. We hypothesise that immune dysfunction in patients with psoriasis similarly causes inflammation and fibrotic process in the lung interstitium. Activated T(H)17 cells were recently found to produce several mediators such as interleukin 17A, 17F, and 22, which induce keratinocyte proliferation and other hallmark features of psoriasis [34]. Interestingly, interleukin 17, which is produced by T(H)17 cells, contributes to alveolitis and enhances cytokine production of pulmonary fibroblasts [35]. However, the future immunology research is crucial to confirm our speculation that the pathogenic role of interleukin 17 is equivalent in the skin and lungs. Another study reports that dermal cell proliferation in psoriasis is secondary to activated TGF-α, which may also be associated with activated TGF-β, leading to pulmonary fibrosis [19]. Moreover, abnormal histologic features of lung tissue were observed in 4 (44.4%) out of 9 patients with rheumatoid factor-negative arthritis (2 with fibrosis, 1 with follicular lymphoid hyperplasia, and 1 with DIP) who did not have respiratory-related symptoms [36]. These findings collectively suggest that the coexistence of ILD and psoriasis is mechanistically plausible.

The pulmonary disease in psoriasis could potentially be similar to that in ankylosing spondylitis (AS) because of their clinical similarities (negative rheumatoid factor) between psoriatic spondylitis and AS. However, the incidence of pulmonary involvement in AS is also uncommon; a previous review at the Mayo Clinic suggests that the frequency is <2% [37]. The patients in the present study showed relatively mild impairment in FVC% predicted (median, 69; range, 38–89) in contrast to a severely decreased DLco% predicted (median, 47; range, 17–95). Given the high prevalence of concomitant PH or possible PH (42.9%) in our patients, this discrepancy between FVC and DLco might result from disproportionally elevated pulmonary artery pressure. Expectedly, mild PH is reported to be significantly more frequent in psoriasis patients, implying that increased antigen presentation, increased cutaneous T-lymphocyte activity, interleukins, and tumour necrosis factor-α in psoriasis cause endothelial dysfunction, which is an important pathophysiological characteristic of PH [38]. Therapeutic modalities for PH triggered by psoriasis should be investigated further.

In the present study, 11 (52.4%) patients had a clinical diagnosis of IPF; regarding radiographic findings, the UIP pattern was more common (42.9%) than the NSIP/OP pattern. This might suggest that immune dysfunction in the lungs triggered by psoriasis tends to cause fibrotic change rather than the conventional inflammatory process. The findings in our patients resemble the patterns observed in rheumatoid arthritis, in which a radiographic UIP pattern is the most common. Therefore, these 2 different diseases might have a common respiratory pathophysiology in setting of a shared clinical manifestation such as joint synovitis. Furthermore, compared to conventional IPF patients, the decline of pulmonary function was relatively mild, as indicated by a modest change in the rate of predicted FVC% (range, −5.7% to +18%/year). This also implicates a distinct feature of IPF associated with psoriasis as compared to conventional IPF. In terms of ILD treatment, Gupta and Espiritu [29] reported of a patient with NSIP associated with psoriasis responding to azathioprine, while Miyachi et al. [30] demonstrated a case which highlights the improvement of the interstitial lung pattern during psoriasis treatment with secukinumab. These two reports anecdotally support the efficacy of immunomodulatory therapy for ILD in a patient with underlying psoriasis. The efficacy of antifibrotic agents (i.e., pirfenidone and nintedanib) for psoriasis-associated IPF would be worth exploring in the future.

The major limitation of this study is that the direct association between psoriasis and ILD cannot be concluded from the findings of this case series, although the prevalence of psoriasis in our ILD cohort was not negligible. Due to the retrospective nature, the study information was loaded with several confounding factors (varied ILD patterns, smoking status, use of immunosuppressants, and other autoimmune features) that make it difficult to draw a valid conclusion. For example, the high prevalence of smoking status (71.4%) in our cohort might have been accounting for increased incidence of ILD as smoking was known to be one of the risk factors for IPF [39]. Prospective studies comparing prevalence of ILD in the psoriasis cohort and that in the general population are required to delineate the association. Second limitation is that the diagnosis of psoriasis was a self-reported diagnosis, despite being driven by dermatologists, and not based on clinical-pathological evidence saved in our electric medical record system. Likewise, most of the ILD diagnosis was only based on radiographic and clinical evaluation (except for 4 patients who underwent lung biopsies). Therefore, the inaccuracy of diagnosis makes the obtained results weaker.

5. Conclusion

We reported 21 ILD cases with antecedent or concomitant diagnosis of psoriasis. Among our ILD cohort, 4.7% of those had concomitant diagnosis of psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis. Considering the 3.2% prevalence of psoriasis among adults [40], this might suggest real association between two different disease entities, which cannot be concluded by this case series due to the major limitation discussed above. Further prospective and large clinical studies are warranted to investigate the association between these two different disease entities.

Abbreviations

- ANA:

Antinuclear antibody

- ANCA:

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody

- AS:

Ankylosing spondylitis

- CHP:

Chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis

- CT:

Computed tomography

- CTD-ILD:

Connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease

- EP:

Eosinophilic pneumonia

- GGO:

Ground glass opacities

- HP:

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis

- ILD:

Interstitial lung disease

- IPF:

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- MP:

Mercaptpurine

- MTX:

Methotrexate

- NSIP:

Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia

- NYHA:

New York Heart Association

- OP:

Organizing pneumonia

- PE:

Pulmonary embolus

- PM/DM:

Polymyositis/dermatomyositis

- PH:

Pulmonary hypertension

- RBILD/DIP:

Respiratory bronchiolitis-associated interstitial lung disease/desquamative interstitial pneumonia

- TBLB:

Transbronchial lung biopsy

- T(H)17:

Type 17 helper T

- UIP:

Usual interstitial pneumonia

- VATS:

Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Disclosure

An abstract reporting preliminary data of this work was presented at the 2017 American Thoracic Society Annual Meeting, May 24, 2017, Washington, DC.

Conflicts of Interest

Mary Salvatore is a speaker for Genentech and Boehringer Ingelheim. The rest of the authors do not have any conflicts of interest to declare.

Authors' Contributions

GI was the principal author and had full access to all data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis; SD, AM, SOA, MS, MB, and MLP contributed substantially to the study design, interpretation, and writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Boehncke W.-H., Schön M. P. Psoriasis. The Lancet. 2015;386(9997):983–994. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61909-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daudén E., Castañeda S., Suárez C., et al. Clinical practice guideline for an integrated approach to comorbidity in patients with psoriasis. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2013;27(11):1387–1404. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coto-Segura P., Eiris-Salvado N., González-Lara L., et al. Psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Dermatology. 2013;169(4):783–793. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armstrong A. W., Harskamp C. T., Armstrong E. J. The association between psoriasis and hypertension. Journal of Hypertension. 2013;31(3):433–443. doi: 10.1097/hjh.0b013e32835bcce1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armstrong A. W., Harskamp C. T., Armstrong E. J. The association between psoriasis and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutrition & Diabetes. 2012;2(12):p. e54. doi: 10.1038/nutd.2012.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller I. M., Ellervik C., Yazdanyar S., Jemec G. B. E. Meta-analysis of psoriasis, cardiovascular disease, and associated risk factors. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2013;69(6):1014–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gu W.-J., Weng C.-L., Zhao Y.-T., Liu Q.-H., Yin R.-X. Psoriasis and risk of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. International Journal of Cardiology. 2013;168(5):4992–4996. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.07.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van der Voort E. A. M., Koehler E. M., Dowlatshahi E. A., et al. Psoriasis is independently associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in patients 55 years old or older: results from a population-based study. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2014;70(3):517–524. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Webb W. R. High-Resolution CT of the Lung. 4th. Philadelphia, PA, USA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guzman L. R., Gall E. P., Pitt M., Lull G. Psoriatic spondylitis. Association with advanced nongranulomatous upper lobe pulmonary fibrosis. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1978;239(14):1416–1417. doi: 10.1001/jama.239.14.1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goh N. S. L., Desai S. R., Veeraraghavan S., et al. Interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2008;177(11):1248–1254. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200706-877oc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaplan R. L., Waite D. H. Progressive interstitial lung disease from prolonged methotrexate therapy. Archives of Dermatology. 1978;114(12):1800–1802. doi: 10.1001/archderm.114.12.1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hiki Y., Kokubo T., Horii A., et al. A case of severe IgA nephropthy associated with psoriatic arthritis an idopathic interstitial pneumonia. Pathology International. 1993;43(9):522–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1993.tb01166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salaffi F., Manganelli P., Carotti M., Subiaco S., Lamanna G., Cervini C. Methotrexate-induced pneumonitis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis: report of five cases and review of the literature. Clinical Rheumatology. 1997;16(3):296–304. doi: 10.1007/bf02238967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawakami K., Kadota J., Abe K., et al. A case of non-specific interstitial pneumonia associated with psoriasis vulgaris and polymyalgia rheumatic. Nihon Kyobu Shikkan Gakkai Zasshi. 1997;35(12):1395–1399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ameen M., Taylor D. A., Williams I. P., Wells A. U., Barker J. N. W. N. Pneumonitis complicating methotrexate therapy for pustular psoriasis. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2001;15(3):247–249. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2001.t01-1-00223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woltsche M., Woltsche-Kahr I., Roeger G. M., Aberer W., Popper H. Sulfasalazine-induced extrinsic allergic alveolitis in a patient with psoriatic arthritis. European Journal of Medical Research. 2001;6(11):495–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manero Ruiz F. J., Larraga Palacio R., Herrero Labarga I., Ferrer Peralta M. Neumonitis por sales de oro en la artritis psoriásica: a propósito de dos casos. Anales de Medicina Interna. 2002;19(5):237–240. doi: 10.4321/s0212-71992002000500006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tokunaga T., Ohno S., Tajima S., Oshikawa K., Hironaka M., Sugiyama Y. Usual interstitial pneumonia associated with psoriasis vulgaris. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi. 2002;40(8):692–696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abou-Samra T., Constantin J.-M., Amarger S., et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis complicated by acute respiratory distress syndrome. British Journal of Dermatology. 2004;150(2):353–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Messina M., Scichilone N., Guddo F., Bellia V. Rapidly progressive organising pneumonia associated with cytomegalovirus infection in a patient with psoriasis. Monaldi Archives for Chest Disease. 2007;67(3):165–168. doi: 10.4081/monaldi.2007.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.El-Hag K., Dercken H.-G., Prenzel R., Hölzle E. Medikamenten-induzierte alveolitis unterInfliximab-/azathioprin-therapie. Pneumologie. 2008;62(4):204–208. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1016443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Penizzotto M., Retegui M., Arrién Zucco M. F. Neumonía organizada asociada a psoriasis. Archivos de Bronconeumología. 2010;46(4):210–211. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee M. A., Hutchinson D. G. HRCT-proven leflunomide pneumonitis in a patient with psoriatic arthritis and normal lung function tests and chest radiography. Rheumatology. 2010;49(6):1206–1207. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deegan A. P., Kirby B., Rogers S., Crotty T. B., McDonnell T. J. Organising pneumonia associated with fumaric acid ester treatment for psoriasis. The Clinical Respiratory Journal. 2010;4(4):248–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-699x.2009.00180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leger S., Etienne M., Duval-Modeste A.-B., Roussel A., Caron F., Thiberville L. Pneumopathie interstitielle subaiguë après traitement d’un psoriasis par infliximab. Annales de Dermatologie et de Vénéréologie. 2011;138(6-7):499–503. doi: 10.1016/j.annder.2011.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bale J., Chee P. Acute alveolitis following infliximab therapy for psoriasis. Australasian Journal of Dermatology. 2013;54(1):61–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2012.00924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kakavas S., Balis E., Lazarou V., Kouvela M., Tatsis G. Respiratory failure due to infliximab induced interstitial lung disease. Heart & Lung. 2013;42(6):480–482. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gupta R., Espiritu J. Azathioprine for the rare case of nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis in a patient with psoriasis. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2015;12(8):1248–1251. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201505-274LE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miyachi H., Nakamura Y., Nakamura Y., Matsue H. Improvement of the initial stage of interstitial lung disease during psoriasis treatment with secukinumab. The Journal of Dermatology. 2017;44(12):e328–e329. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.14026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deng W., Miao C., Zhang X. Abrupt generalized pustules in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and interstitial lung disease. The Journal of Dermatology. 2018;45(2):198–201. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.14126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lateef O., Shakoor N., Balk R. A. Methotrexate pulmonary toxicity. Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 2005;4(4):723–730. doi: 10.1517/14740338.4.4.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ungprasert P., Srivali N., Thongprayoon C. Association between psoriasis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Dermatological Treatment. 2016;27(4):316–321. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2015.1107180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh T. P., Schön M. P., Wallbrecht K., Gruber-Wackernagel A., Wang X.-J., Wolf P. Involvement of IL-9 in Th17-associated inflammation and angiogenesis of psoriasis. PLoS One. 2013;8(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051752.e51752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Molet S., Hamid Q., Davoineb F., et al. IL-17 is increased in asthmatic airways and induces human bronchial fibroblasts to produce cytokines. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2001;108(3):430–438. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.117929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scherak O., Kolarz G., Popp W., Wottawa A., Ritschka L., Braun O. Lung involvement in rheumatoid factor-negative arthritis. Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology. 1993;22(5):225–228. doi: 10.3109/03009749309095127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosenow E., Strimlan C. V., Muhm J. R., Ferguson R. H. Pleuropulmonary manifestations of ankylosing spondylitis. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 1977;52(10):641–649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gunes Y., Tuncer M., Calka O., et al. Increased frequency of pulmonary hypertension in psoriasis patients. Archives of Dermatological Research. 2008;300(8):435–440. doi: 10.1007/s00403-008-0859-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baumgartner K. B., Samet J. M., Stidley C. A., Colby T. V., Waldron J. A. Cigarette smoking: a risk factor for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1997;155(1):242–248. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.1.9001319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rachakonda T. D., Schupp C. W., Armstrong A. W. Psoriasis prevalence among adults in the United States. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2014;70(3):512–516. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.