Abstract

Fluoride intake from tap water supplied by fluoride-containing groundwater has been the primary cause of fluorosis among the residents of Buak Khang Subdistrict, Chiang Mai Province, Thailand. To reduce fluoride intake, bottled water treated using reverse-osmosis membranes has been made available by community-owned water treatment plants. This study aimed to assess the resultant reduction in fluoride intake from using bottled water for drinking and cooking. Water consumption surveys were conducted by providing bottled water to 183 individuals from 35 randomly selected households and recording the amount of water consumed for drinking and cooking. The mean drinking water consumption was 1.62–1.88 L/capita/day and the cooking water consumption on weekends (5.06 ± 3.04 L/household/day) was higher than that on weekdays (3.80 ± 1.90 L/household/day). The per capita drinking water consumption exhibited a positive correlation with body weight; however, the low-weight subjects consumed more drinking water per kilogram of body weight than the heavy subjects. Although sex and day of the week did not significantly affect drinking water consumption per capita, girls consumed less water in school possibly due to their group mentality. Drinking water consumption per kilogram of body weight was significantly higher among women, children, and the elderly because these groups generally have low body weights. The fluoride intake from using tap water for drinking and cooking was estimated to be 0.18 ± 0.10 mg/kg-body weight/day and 5.55 ± 3.52 mg/capita/day, respectively, whereas using bottled water for drinking and cooking reduced the fluoride intake to 0.002 ± 0.002 mg/kg-body weight/day and 0.07 ± 0.05 mg/capita/day, respectively. Despite the increased cost, 98% and 90% of the subjects selected bottled water over tap water for drinking and cooking, respectively; thus, bottled water delivery services could be used to mitigate fluoride intake in developing countries.

Keywords: Environmental science, Geochemistry, Drinking water, Water consumption, Fluoride, Bottled water, Groundwater

1. Introduction

In many countries, groundwater is preferred as a source of drinking water over surface water because of its easy access and superior quality, such as lower levels of turbidity and microbial contamination (Mohebbi et al., 2013; Hybel et al., 2015; Abbasnia et al., 2018). However, groundwater may be contaminated by naturally occurring hazardous substances such as arsenic and fluoride (Brindha and Elango, 2011; Banerjee, 2015; Navarro et al., 2017; Yeşilnacar et al., 2016). In Viet Nam, Pakistan, Argentina, Myanmar, and Nepal, at least a million people are thought to have been exposed to arsenic (Ravenscroft et al., 2009; Augustsson and Berger, 2014; Bhowmick et al., 2018; Li et al., 2018). Groundwater contamination with fluoride has also been reported in many countries including China, India, Iran, Mexico, and Thailand (Wood and Singharajwarapan, 2014; Ali et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2017; Dehbandi et al., 2018). However, presence of fluoride in groundwater have drawn less attention than arsenic because it has been believed that low levels of fluoride can protect human teeth from decay and that the only risks from fluoride are aesthetic problems, such as mottled teeth (Petersen and Ogawa, 2016).

Fluorine is present in groundwater as the negatively charged fluoride ion, F− (Brindha and Elango, 2011), which is emitted by the weathering and leaching of fluorine-bearing minerals, e.g., fluorite, fluorapatite, and biotite (Abiye et al., 2018). Geothermal water can also contribute fluoride to groundwater (Wood and Singharajwarapan, 2014). Fluoride in drinking water accumulates in teeth via ion exchange with hydroxyapatite to form fluorapatite, which is hard and resistant to acids (Paz et al., 2017). Thus, low levels of fluoride in drinking water, e.g. 0.5 mg/L, are considered to prevent and/or reduce dental decay (Sharma et al., 2017). Nevertheless, fluoride concentrations in drinking water greater than 1.5 mg/L have been known to cause several forms of fluorosis such as dental, skeletal, and non-skeletal fluorosis (Takahashi et al., 2001; McGrady et al., 2012). Dental fluorosis presents in children and young people as white spots or mottled enamel (Pramanik and Saha, 2017; Yuyan et al., 2017). Skeletal fluorosis results in discomfort or pain in the neck, bones, and/or joints, and ultimately causes bone fractures and/or permanent disability in elderly people (Liu et al., 2015). Thus, the large number of populations drinking groundwater that contains excess fluoride is a worldwide concern (Roy and Dass, 2013).

Drinking water is the main source of fluoride to human bodies, while cooking water and food are minor sources. It has been reported that 90% of the fluoride in drinking water is absorbed in the digestive tract, while only 30–60% of the fluoride in food is absorbed (WHO, 1996). Cerklewski (1997) reported that 80–95% of fluoride intake is absorbed in human body, of which 52.6–72.7% is excreted through urine (Fig. S1). Assuming a water intake of 2 L/capita/day for an average body weight of 60 kg, the World Health Organization (WHO) has set the guideline value of fluoride in drinking water at 1.5 mg/L. However, the WHO has suggested that each country sets its own guideline value based on its residents' water consumption, which depends on the country's climate (WHO, 2017). Since Thailand is located in a tropical region, its residents tend to consume more water than those living in cold or temperate regions (Hossain et al., 2013); thus, the guideline value of fluoride in drinking water in Thailand was revised from 1.5 mg/L to be no more than 0.7 mg/L in order to control fluorosis (Meyer et al., 2009; Ministry of Public Health Thailand, 2010). Furthermore, the water consumption of each person within a population varies depending on their activities and physical attributes, such as age, body weight, and sex; consequently, the fluoride intake of people in fluoride-affected areas may vary significantly.

Therefore, the water consumption of people in fluoride-affected areas must be accurately estimated to perform a risk assessment of fluoride intake. Water consumption studies have been reported using various methods (Table S1); conventional methods for estimating drinking water consumption are questionnaire surveys, interview surveys, and self-recording by participants (Samal et al., 2015; Guissouma et al., 2017; Yousefi et al., 2018). Since these conventional methods are low-cost and do not require plumbing, they are suitable for collecting large water consumption data sets in a short period of time (Jones et al., 2006; Goodman et al., 2013; Säve-Söderbergh et al., 2018). However, these methods are semi-quantitative and cannot be used to accurately record water consumption data for several reasons, such as participants' unfamiliarity with the measurement method, unwillingness to answer questions, and lost memories. Recently, a novel method using Short Message Service (SMS) questionnaires has been proposed to increase response rates relative to those of traditional methods, such as telephone interviews and web questionnaires, but this is still a semi-quantitative method (Säve-Söderbergh et al., 2018). In order to obtain direct water consumption measurements, one study counted the number of cups or packaged units of water consumed by individuals (Watanabe et al., 2004). Similarly, recent studies have estimated daily water consumption by counting the number of times that a PET bottle is refilled each day (Hossain et al., 2013; Craig et al., 2015); however, because the volume of each refill may vary, this method also has limited accuracy and may not be suitable in survey areas where local residents are not used to refilling bottled water.

Thai residents in the Chiang Mai Basin, which includes the Chiang Mai, Lamphun, and Mae Hong Son Provinces, have been suffering from fluorosis caused by drinking fluoride-laden groundwater for many years (Takeda and Takizawa, 2008; Chuah et al., 2016). For example, fluoride concentrations were reported to be 0.75–7.46 mg/L in the San Kamphaeng District of Chiang Mai Province (Namkaew and Wiwatanadate, 2012). In order to mitigate fluorosis, the Thai Government subsidized the installation of reverse-osmosis (RO) membrane filtration plants to remove fluoride from groundwater (Phromsakha Na Sakonnakhon et al., 2018). These plants are operated by local residents and the treated water is bottled and delivered to customers. Although the majority of residents are believed to drink bottled water produced by the RO membrane filtration plants because of their health concerns, the ratio of residents using bottled water as opposed to tap water distributed from fluoride-containing groundwater has yet to be studied. While bottled water has a lower fluoride content, it is more expensive than tap water; thus, some residents might continue to opt for tap water. Therefore, it is necessary to assess residents' preferences for drinking and cooking water sources, the fluoride concentrations of water from these sources, and residents' water consumption volumes.

The main objective of this study was to assess whether delivering RO-treated bottled water at an affordable price effectively reduces fluoride intake. We also aimed to identify the water sources currently used by residents in the Buak Khang Subdistrict of San Kamphaeng District, Chiang Mai Province, in order to estimate the daily consumption of drinking water (L/capita/day) and cooking water (L/household/day), and to identify the factors affecting water consumption. To obtain accurate volumes of water consumption, bottles filled with RO-treated water were delivered to participating households; the volume of drinking water consumed by each member of the household and the volume of cooking water consumed by the household were recorded on weekdays and weekends. We also recorded each household's selection of drinking and cooking water sources, the fluoride concentrations of those water sources, and each household member's physical attributes in order to estimate how much each subject's fluoride intake was reduced by the delivery of RO-treated bottled water and to identify the vulnerable population groups who drink more water than others. A water consumption survey was also conducted at the local junior high school to estimate water consumption during school hours.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study area

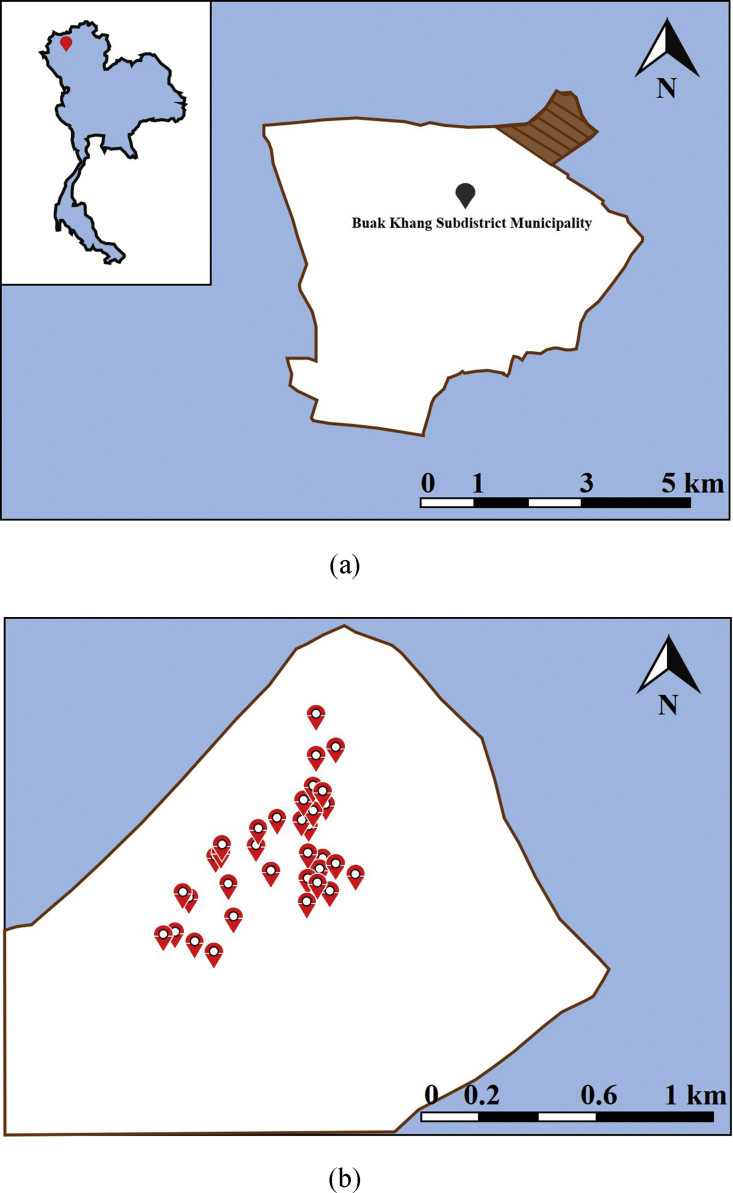

The study area – Buak Khang Subdistrict, San Kamphaeng District, Chiang Mai Province – is located in the northern part of Thailand (Fig. 1). The Buak Khang Subdistrict consists of 13 villages and has a population of 8,059. This study selected two villages, with populations of 1,001 and 577, for the water sampling and consumption surveys because their groundwaters have fluoride concentrations higher than 0.7 mg/L (Namkaew and Wiwatanadate, 2012).

Fig. 1.

Location of the study area: (a) Buak Khang Subdistrict and the study area (hatched area), (b) surveyed households (red pins) and the Banbuakkhang School (green pin).

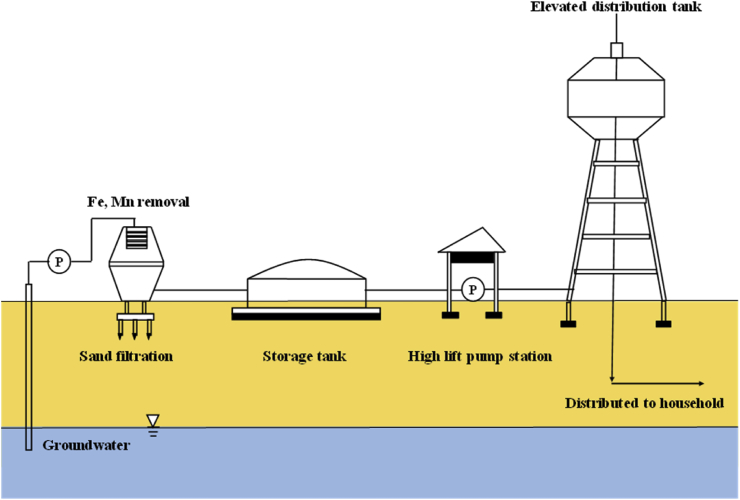

The residents of Buak Khang Subdistrict have long used tap water from the village waterworks (VWWs), which is supplied by groundwater. The VWWs use sand filters to remove iron and manganese from groundwater and distribute treated water from the elevated distribution tank (Fig. 2). Thus, fluoride is not removed by the VWWs.

Fig. 2.

Flow diagram of the village waterworks in Chiang Mai.

In order to remove fluoride from tap water supplied by the VWWs, a local village installed a RO filtration plant at a local junior high school, Banbuakkhang School; the plant was built in 2008 with a subsidy from the Department of Groundwater Resources, Government of Thailand. At the RO plant, RO-treated water is packaged in PET bottles for the school children and also delivered to the local residents in 1-L and 20-L bottles.

2.2. Research subject selection

Because young children tend to incorporate the fluoride that they consume from drinking water into their teeth and bones as they grow, households with children attending Banbuakkhang School were randomly selected with assistance from the school teachers. Among them, those who consented to participate in this survey were finally selected. In September 2017, a weekend survey was conducted for which 31 households with 69 female and 51 male subjects were selected (Table 1). In March 2018, both weekday and weekend surveys were conducted; 33 households with 73 female and 53 male subjects were randomly selected for the weekday water consumption survey and 15 households with 29 female and 28 male subjects were randomly selected for the weekend water consumption survey. Thus, the total number of subjects in the March water consumption surveys was 183, of which 102 were female and 81 were male. The results from March 2018 were used to estimate the effects of sex, age, body weight, and day of the week on water consumption, while the 2017 data set was only used to estimate water consumption per capita because this survey did not record the body weight of the subjects. The survey methods in this study followed the guidelines for a research on human subjects of the Graduate School of Engineering, the University of Tokyo, complied with relevant regulations, and were approved of by the Research Ethics Committee, Graduate School of Engineering, the University of Tokyo. Before the questionnaire survey, the objective and methods were explained to the subjects, and only those who consented to participate in the survey were selected as subjects.

Table 1.

Numbers of subjects in the weekday and weekend surveys.

| Survey periods | Day of the week | Number of households | Number of subjects |

Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Sub Total | ||||

| September 2017 | weekend | 31 | 69 | 51 | 120 | 120 |

| March 2018 | weekday | 33 | 73 | 53 | 126 | 183 |

| weekend | 15 | 29 | 28 | 57 | ||

| Total | 79 | 171 | 132 | 303 | 303 | |

2.3. Water consumption surveys

The first survey was conducted on weekends between September 8, 2017 and September 22, 2017, during which time the average ambient temperature was 28 °C (24.1–32.4 °C). The second survey was conducted between February 23, 2018 and March 19, 2018, during which time the average ambient temperature was 26 °C (18.0–38.0 °C). The second survey was conducted on both weekdays (Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday) and weekends (Saturday and Sunday) because household members spend different amounts of time at home during weekdays as compared to weekends; thus, the amount of water consumed by a household might differ between weekdays and the weekend.

2.3.1. Estimation of water consumption on weekdays

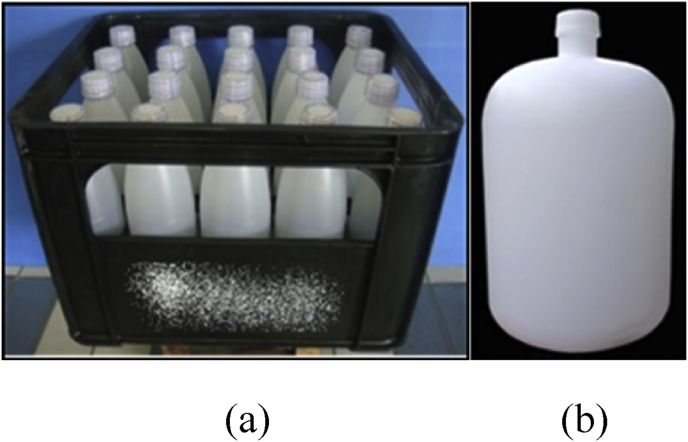

The water consumption survey was conducted by providing bottled water for free in order to use for drinking and cooking in each household. The survey timeline is illustrated in Table 2. Eleven households were surveyed each week for a total of three weeks and 33 households. Bottled water was purchased from the RO filtration plant operated in Banbuakkhang School. On Monday evening, each household received 40 1-L bottles of water (Fig. 3a) for drinking and one 20-L bottle (Fig. 3b) for cooking.

Table 2.

Timeline of the water consumption surveys.

| Weekday survey | Weekend survey | Procedure |

|---|---|---|

| Day 1: Monday | Day 1: Friday |

|

| Day 2: Tuesday Day 3: Wednesday Day 4: Thursday |

Day 2: Saturday Day 3: Sunday |

|

| Day 5: Friday | Day 4: Monday |

|

Fig. 3.

Bottled water from the RO filtration plant at the Banbuakkhang School: (a) 1 L, (b) 20 L.

Both subjects who stayed in their house during the day and those who went out during the day were selected for the drinking water survey. The 1-L bottles were labeled with each subject's name to measure their individual water consumption volume on weekdays, i.e. Tuesday to Thursday. Since most of the local residents had used the RO-treated bottled water prior to this study, we assumed that the subjects' water consumption habits during the survey were similar to those of their daily life.

The objectives of this survey were explained, and the questionnaire sheets written in Thai were given to a member of each household (Fig. S2). This questionnaire recorded the number of household members, their sex and age, and the water sources, namely; bottled water, tap water or groundwater normally used in the household for drinking and cooking. Rainwater harvesting was excluded in our study because it was not commonly used for drinking and cooking water in our study area (Areerachakul, 2013). Furthermore, the body weight of each subject was measured using a digital scale and entered into the questionnaire sheets.

The questionnaire sheets were returned to the survey team on Friday morning and the volumes of water consumed for drinking and cooking were recorded. Drinking water consumption was estimated by counting the empty 1-L water bottles; for bottles that still contained some water, the remaining water volume was measured using a graduated cylinder. The volume of drinking water consumed by each subject was calculated using Eq. (1):

| (1) |

where

DWC is the volume of drinking water consumed by each subject per day (L/capita/day: LCD), and

days is the number of days over which water consumption was measured: 3 (weekdays) or 2 (weekends).

In order to estimate cooking water consumption, the weight of each 20-L bottle was measured using a digital scale before and after the water contained within was consumed and the total amount of water consumed for cooking was calculated using Eq. (2):

| (2) |

where

CWC is the volume of cooking water consumed by each household per day (L/household/day: LHD),

ρ is the specific density of water (0.997 g/mL at 25 °C).

Samples of bottled water, tap water, filtered tap water, and groundwater used in daily life were collected for water quality analyses. Some households use filter units to treat tap water; the filter units treat tap water using a polypropylene sediment filter, softener filter (resin), and granular activated carbon (GAC), then they remove fluoride using a RO membrane filter. The fluoride concentration of the water samples was analyzed using a fluoride-sensitive electrode (Thermo Scientific, ORION STAR A324) and portable meters (HACH, MP Series Instrument Case, Cat. No. MP6K) were used to analyze pH, conductivity, temperature, and total dissolved solid (TDS).

The daily fluoride intake from drinking water per kilogram of body weight and the mean daily fluoride intake from cooking water were calculated using Eqs. (3) and (4), respectively.

| (3) |

where

FD is the daily fluoride intake from drinking water per kilogram of body weight (mg/kg-body weight/day)

CD is the fluoride concentration of the drinking water (mg/L)

W is the body weight of the subject (kg).

| (4) |

where

FC is the mean daily fluoride intake from cooking water of a household (mg/capita/day)

CC is the fluoride concentration of the cooking water (mg/L).

2.3.2. Estimation of water consumption on weekends

As shown in Table 2, the weekend surveys followed the same procedure as the weekday surveys and they were also conducted for three weeks. Water bottles for the weekend surveys were delivered on Friday evening and water consumption volumes were recorded on Monday morning each week. Five households were surveyed each week for a total of three weeks and 15 households.

2.4. Water consumption survey of the students at Banbuakkhang School

The total number of students attending Banbuakkhang School was 122, from which 41 junior high school students with 17 female and 24 male students (aged 12–15 years old) were selected to participate in the water consumption survey during their time at school on weekdays. Before the survey, the objective and methods were explained to the students, and only those who consented to participate in the survey were selected as subjects. At 8 a.m., each student received a bottle of drinking water (0.6 L) labeled with their name. If students wanted to drink more than one bottle of water each day, they could receive another after showing their empty bottle to the teacher. The amount of drinking water consumed by the students was recorded at 4 p.m. by counting the number of empty bottles and/or measuring the remaining water with a graduated cylinder. The body weight of each student was measured using a digital scale and the total volume of drinking water consumed by each student was calculated using Eq. (1).

2.5. Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using R v.3.2.3 (R Core Team, 2014) and results were considered significant when p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Water quality

The water qualities of the collected samples are summarized in Table 3, The fluoride concentrations of bottled water and filtrated tap water were 0.07 mg/L and 0.57 mg/L, respectively. The RO plant at Banbuakkhang School was stably operated by the local managers and the fluoride content of the treated water was less than the guideline value for drinking water in Thailand (0.7 mg/L); RO treatment also reduced the conductivity and TDS of the water. Conversely, tap water from the VWWs (5.94 mg/L) and private wells (0.73 mg/L) contained fluoride concentrations greater than 0.7 mg/L. Filtration of tap water from private wells only marginally reduced fluoride concentration to 0.57 mg/L due to inadequate maintenance of the filter units.

Table 3.

Water quality data of samples obtained from various sources.

| Water type | Fluoride concentration, mg/L | pH | Conductivity, μs/cm | TDS, mg/L |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bottled water (n = 33) | 0.07 ± 0.05 | 7.95 ± 0.32 | 14.0 ± 8.8 | 8.7 ± 5.6 |

| Tap water from village waterworks (n = 32) | 5.94 ± 0.29 | 7.89 ± 0.21 | 546.1 ± 30.5 | 359.0 ± 20.7 |

| Tap water from private wells (n = 3) | 0.73 ± 0.05 | 7.37 ± 0.37 | 781.1 ± 198.4 | 522.6 ± 140.2 |

| Filtered tap water from private wells (n = 2) | 0.57 ± 0.24 | 7.59 ± 0.35 | 644.1 ± 60.6 | 426.8 ± 42.5 |

Note: data shown as Mean ± SD.

3.2. Summary of water consumption

Table 4 presents a summary and comparison of the water consumption surveys conducted during March 2018 and September 2017. The amount of drinking water consumed during the March survey (18.0–38.0 °C) was less than that consumed during the September survey (24.1–32.4 °C), but not significantly (t-test, p > 0.05). The average drinking water consumption was equal or less than 2 LCD and the cooking water consumption was 3.80–5.06 LHD; thus, the sum of drinking and cooking water consumption was approximately 3 LCD for a representative four-member household in the study area. For comparison, the volume of water consumption reported by a Swedish study was approximately 0.98 LCD (Säve-Söderbergh et al., 2018) and Watanabe et al. (2004) reported the mean drinking water consumption in Bangladeshi communities to be 3 LCD; these results suggest that local climate is a factor that influences drinking water consumption. The temperature difference between the March and September surveys in this study was minimal and there was no significant difference in water consumption between the surveys.

Table 4.

Volume of water consumed on weekdays and weekends.

| Day in week | Water use | Number of subjects | Amount of water consumed |

Survey period | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Min | Max | ||||

| Weekday | Drinking, L/capita/day | Female (n = 73) | 1.75 ± 0.75 | 0.26 | 3.33 | March 2018 |

| Male (n = 53) | 1.62 ± 0.85 | 0.10 | 3.67 | |||

| Cooking, L/household/day | n = 33 | 3.80 ± 1.90 | 0.33 | 7.05 | ||

| Weekend | Drinking, L/capita/day | Female (n = 29) | 1.78 ± 0.79 | 0.50 | 3.73 | |

| Male (n = 28) | 1.81 ± 1.04 | 0.50 | 4.00 | |||

| Cooking, L/household/day | n = 15 | 5.06 ± 3.40 | 0.00 | 10.50 | ||

| Weekend | Drinking, L/capita/day | Female (n = 69) | 2.03 ± 1.24 | 0.50 | 3.73 | September 2017 |

| Male (n = 51) | 1.88 ± 1.26 | 0.50 | 4.00 | |||

| Cooking, L/household/day | n = 31 | 4.31 ± 3.53 | 0.00 | 10.5 | ||

3.3. Age and body weight of the subjects

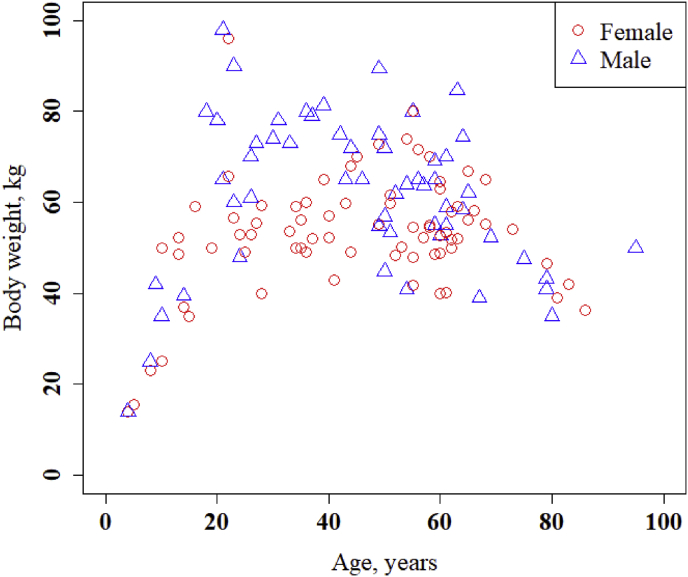

The subjects in this survey spanned a wide range of ages (4–95 years old) and body weights (14–98 kg). Overall, the age and body weight of the subjects exhibit three different trends (Fig. 4):

-

•

For subjects younger than 20 (female) or 30 (male) years old, body weight increased linearly with age.

-

•

Male body weight increased slightly between 30–40 years old, reaching a maximum near 40 years old, and then gradually decreased. Female body weight was stable between 20–60 years old.

-

•

Both males and females older than 60 years old tended to have lower body weights, which has been attributed to reduced food intake relative to the young generation.

-

•

This study included some heavy subjects in the 20–60 year age group that weighed greater than 80 kg; however, there were no heavy subjects over 65 years old (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The relationship between subjects' age and body weight (n = 183).

3.4. Drinking water consumption

3.4.1. Relationship between day of the week and drinking water consumption

While the reason that subjects who go to work on weekdays consume the same median amount of water on weekdays and weekends is not clear, the inter-quartile ranges (IQRs) of their water consumption were slightly larger on weekdays than on weekends. On both weekdays and weekends, the drinking water consumption of the subjects who stay at home was slightly higher than that of the subjects who work outside of their home, but not significantly (p > 0.05).

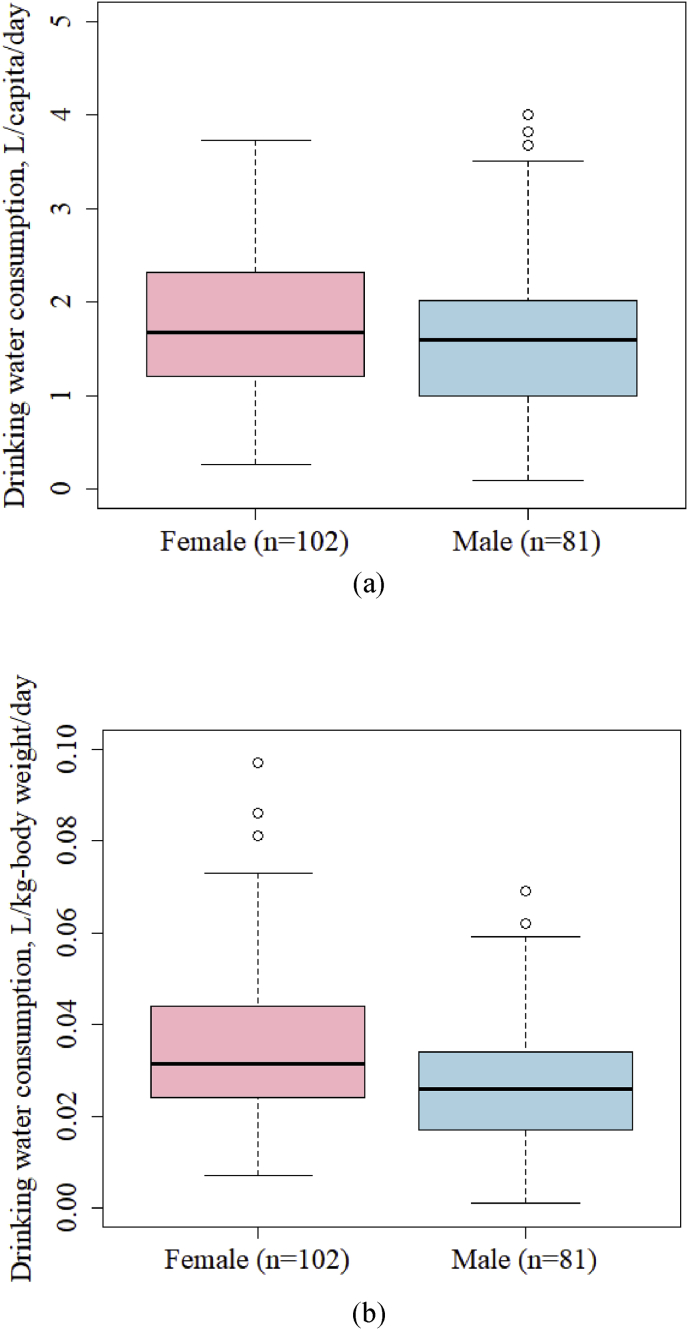

3.4.2. Drinking water consumption of male and female subjects

Despite their lower body weights (Fig. 4), the median drinking water consumption of females (1.67 LCD) was slightly higher than that of males (1.60 LCD); however, the difference was not significant (t-test, p > 0.05) (Fig. 5a). While some studies have reported that the total liquid intake of adolescents and adults does not differ significantly based on sex (Watanabe et al., 2004; Stookey and König, 2018), a contrary study reported that the average water intake of males and females were significantly different (Hossain et al., 2013). In this study, the female subjects stayed in their houses longer than the male subjects in order to do their housework, and most of the male subjects went out to work during the day without bringing water from their house. Thus, the amount of time spent at home might contribute to the slight difference between male and female water consumption, as described in the previous section.

Fig. 5.

Drinking water consumption (DWC) of male and female subjects: (a) DWC per capita (L/capita/day, LCD), and (b) DWC per body-weight (L/kg-body weight/day, LWD) (n = 183).

Although the majority of previous studies have reported water consumption in units of LCD (Watanabe et al., 2004; Vieux et al., 2017; Kavouras et al., 2017), water consumption per kilogram of body weight (L/kg-body weight/day, LWD) might be a more accurate indicator of fluoride intake and risk for fluorosis than daily water consumption per capita (LCD). Because the female subjects' body weights (52.5 ± 13.1 kg-body weight) were less than those of the male subjects (62.3 ± 16.1 kg-body weight) (Fig. S3), the water consumption per kilogram of body weight per day (LWD) of the female subjects was higher than that of the male subjects (Fig. 5b). This indicates that the female subjects were more likely to be exposed to a higher fluoride intake and the associated risks.

3.4.3. Body weight and drinking water consumption

Drinking water consumption in relation to body weight exhibited a significant linear relationship (p < 0.05). This relationship is in agreement with a previous study that reported subjects' total water consumption was correlated with their body weight (Heller et al., 1999). However, there were subjects who were over 70 kg but drank less than 2 LCD, the majority of whom were people younger than 35 years old, which indicates that they might prefer drinking beverages probably containing sugar rather than water.

Most of the subjects older than 37 years old who drink more than 3 LCD weigh over 55 kg. This trend may be caused by the need for heavier subjects to sweat more to maintain their body temperature. Heat generated by our bodies is linearly related to body weight, whereas heat released from our bodies is linearly related to body surface; thus, in order for a heavy person to release the same proportion of body heat as a slim person, they need to sweat more (Thornton, 2016). There is a negative correlation between body weight and drinking water consumption per kilogram of body weights for both male (p > 0.05) and female (p < 0.05) subjects; while the heavy-weight subjects consumed larger volumes of water than the low-weight subjects, they consumed less water than the low-weight subjects in terms of consumption per kilogram of body weight. Thus, the low-weight subjects are predicted to be at higher risk of fluorosis, such as dental and skeletal fluorosis, than the heavy-weight subjects (Takahashi et al., 2001; McGrady et al., 2012).

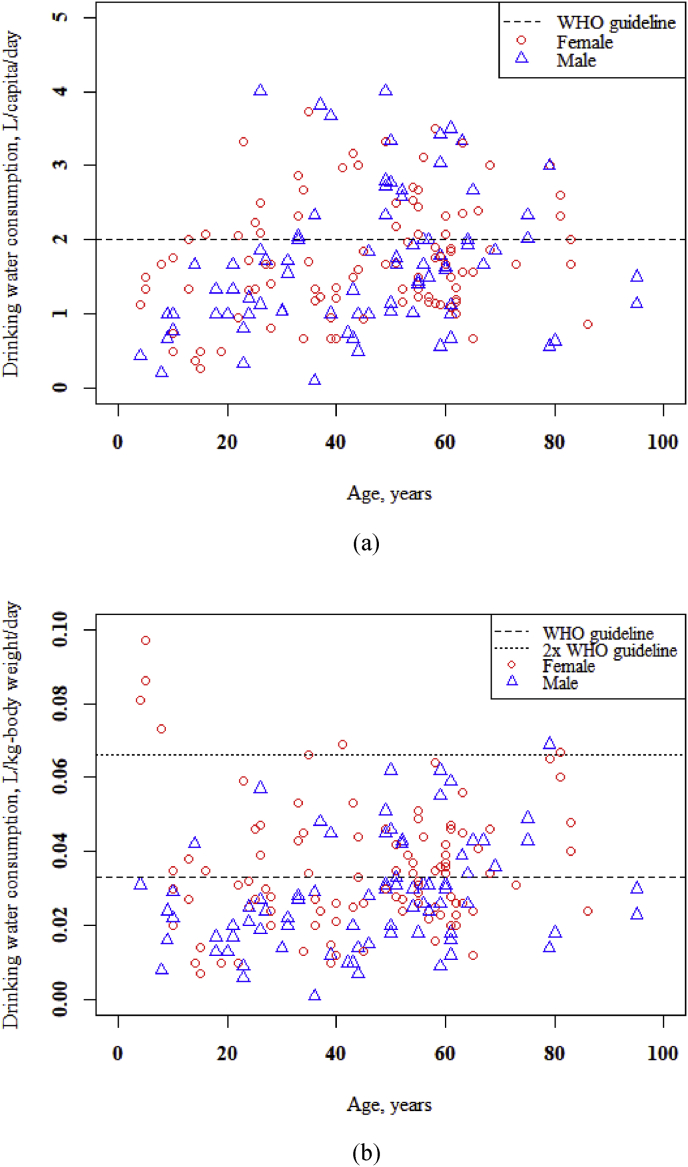

3.4.4. Age and drinking water consumption

The drinking water consumption of both female and male subjects exhibits increasing trends as a function of age (p < 0.05, regression line not plotted in Fig. 6a). A linearly increasing trend was also observed among subjects up to 15 years old (Hossain et al., 2013). Barraj et al. (2009) reported that the age and sex of subjects were significant predictors of total water consumption (p < 0.0001), while daily mean water consumption data obtained by the 12mSMS (SMS questionnaire) method was not significantly different for age groups above 40 years old (Barrj et al., 2009; Säve-Söderbergh et al., 2018).

Fig. 6.

Relationship between age and drinking water consumption: (a) DWC per capita (L/capita/day, LCD), and (b) DWC per body-weight (L/kg-body weight/day, LWD) (n = 183).

In this study, the body weights of female subjects were stable between 20 and 60 years, while the body weights of male subjects did not stabilize, continuously increasing up to 40 years. Moreover, the children (age 0–20 years) and elderly subjects (>60 years) in this study had lower body weights than the intermediate age groups (20–60 years). Therefore, when the same volume of drinking water is consumed by subjects of different ages, children and elderly subjects tend to consume more water than the other subjects in terms of drinking water consumption per kilogram of body weight (LWD). Ahada and Suthar (2017) reported that children absorbed more fluoride than adults because their small bodies tend to accumulate more fluoride. Thus, female children and the elderly female subjects were identified to be the highest risk groups because of their high-water consumption per kilogram of body weights. This is especially true for females younger than 10 years old; hence, they should be protected from fluoride exposure.

Many subjects younger than 45 years old consumed less than 2 LCD and some drank less than 1 LCD because (1) they were away from their house during the day and (2) they might prefer to drink other beverages, such as sparkling water, ice coffee, and ice tea, instead of water. Subjects between 20 and 64 years old tend to drink carbonated beverages and juices (Heller et al., 1999), and thus drink less water. There are some other pathways of fluoride ingestion through beverages, food, and/or toothpaste which should also be considered (Gupta and Banerjee, 2011; Joshi et al., 2011; Oganessian et al., 2011).

Conversely, middle-aged and elderly subjects tended to drink more than 2 LCD. In this survey, some elderly subjects reported that they spend all day in their house and must take medication several times per day. In contrast to the results of this survey, a previous study indicated that the drinking water consumption of people aged 55 years or older was lower than that of 18–34 year olds (Goodman et al., 2013), which suggests that the water consumption of the elderly differs between populations in different countries. There were some male and female subjects between 20 and 60 years old who drank more than 3 LCD and the body weights of these subjects were higher than those of others, as discussed in the previous section.

Overall, 30.6% of the subjects (183 subjects total) consumed more than 2 LCD of water (Fig. 6a), including 32 of 102 females (31.4%) and 24 of 81 males (28.9%). The percentage of female subjects who consumed more than 2 LCD was not significantly different from that of the male subjects (Chi-squared test, p > 0.05). Based on drinking 2 LCD of water and the average body weight of 60 kg used by the WHO to set the guideline value of fluoride in drinking water, the average drinking water consumption per kilogram of body weight is calculated to be 0.033 LWD. Accordingly, 37.7% of the subjects consumed more than 0.033 LWD (Fig. 6b), including 48 females (47.1%) and 21 males (25.3%). The percentage of male subjects that consumed more than 0.033 LWD (25.3%) was far less than the percentage of female subjects, and less than the percentage of male subjects that consumed more than 2 LCD (28.9%). Conversely, the percentage of female subjects that consumed more than 0.033 LWD (47.1%) was higher than the percentage of female subjects that drank more than 2 LCD (31.4%) because of their low body weight.

The female subjects between 4 to 8 years old consumed significantly more water per kilogram of body weight (0.073–0.097 LWD) than those of other ages because of their low body weight (t-test, p < 0.001) (Fig. 6b). The water consumption of some elderly subjects (approximately 80 years) was also greater than 0.033 LWD because of their low body weights. Moreover, some of the subjects consumed more than 0.066 LWD, which is twice as much as the average daily water consumption per kilogram of body weight (0.033 LWD) derived using the average body weight used by the WHO guideline value. These high-volume water consumers are identified to be in the high fluorosis-risk group.

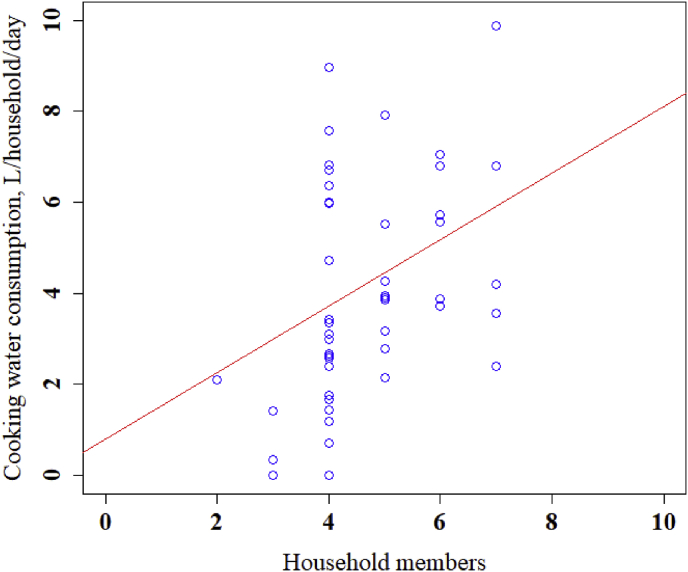

3.5. Cooking water consumption

Most of the households have four or more household members (Fig. 7); four is the mode and considered to be a representative number. The cooking water consumption of households increased as the number of household members increased (p < 0.05); however, cooking water consumption varied significantly, ranging from 0 to 8.98 LHD for four-member households. Cooking water consumption depends on the water usage activities of each household, such as cooking, rice cooking, rice soaking, steaming milk bottles, and preparing milk for babies. Some households reported that they did not use any water for cooking because they bought prepared food and did not cook in their house.

Fig. 7.

Relationship between cooking water consumption and the number of household members (n = 48, March 2018).

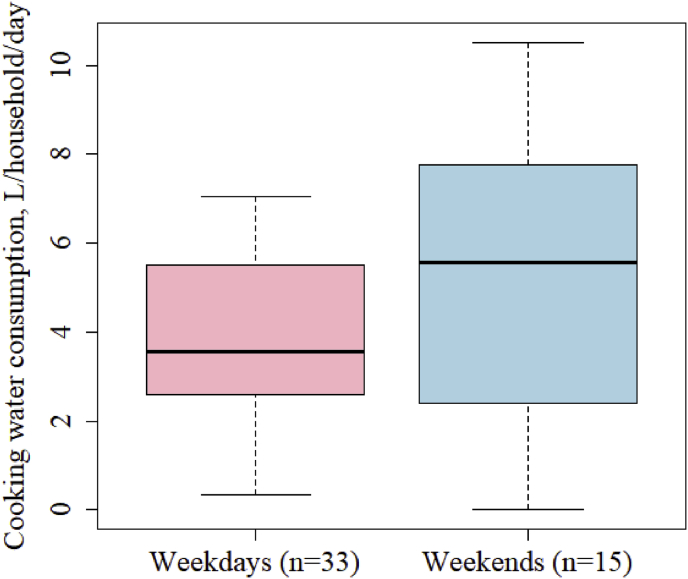

Fig. 8 presents boxplots of cooking water consumption on weekdays and weekends. The median value and inter-quartile range (IQR) were greater on weekends than on weekdays (Kruskal-Wallis test, p < 0.05) because the subjects stayed in their house and cooked at home more frequently on weekends. This dependence on day of the week is in contrast to the drinking water consumption results, which were independent of the day of the week.

Fig. 8.

Cooking water consumption on weekdays and weekends.

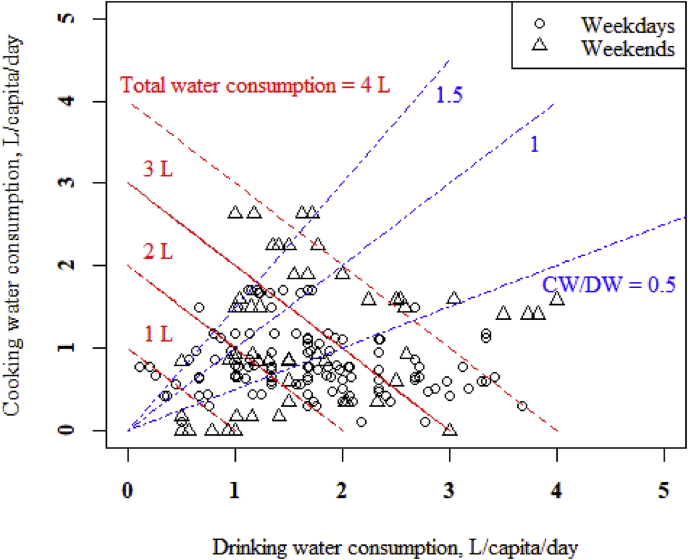

Combining drinking and cooking water consumption, 75.4% of the subjects consumed more than 2 LCD and 32.8% consumed more than 3 LCD (Table S2). The median ratio between cooking water and drinking water consumption (CW/DW) was 0.5, which means that the CW/DW was less than 0.5 for approximately half of the households and greater than 0.5 for the other half (Table S2). Thus, it is important to take cooking water consumption, in addition to drinking water, into consideration for estimating the total amount of fluoride intake from water.

Fig. 9 compares drinking water and cooking water consumption. It should be noted that cooking water consumption was an average of each household member's consumption, while drinking water consumption was measured for each subject. Nevertheless, Fig. 9 illustrates the comparative significance of drinking and cooking water consumption as a source of fluoride intake. The CW/DW was low on weekdays (<0.5), but it increased on weekends because more subjects cooked at home. On weekends, 5.6% of subjects consumed cooking water significantly more than drinking water (CW/DW > 1.5), which indicates that cooking water could be the main source of fluoride intake for these subjects. Six of 183 subjects consumed less than 1 LCD of total water (drinking and cooking) on weekends, which suggests that they were not home during most of the weekend.

Fig. 9.

Relationship between drinking and cooking water consumption on weekdays and weekends.

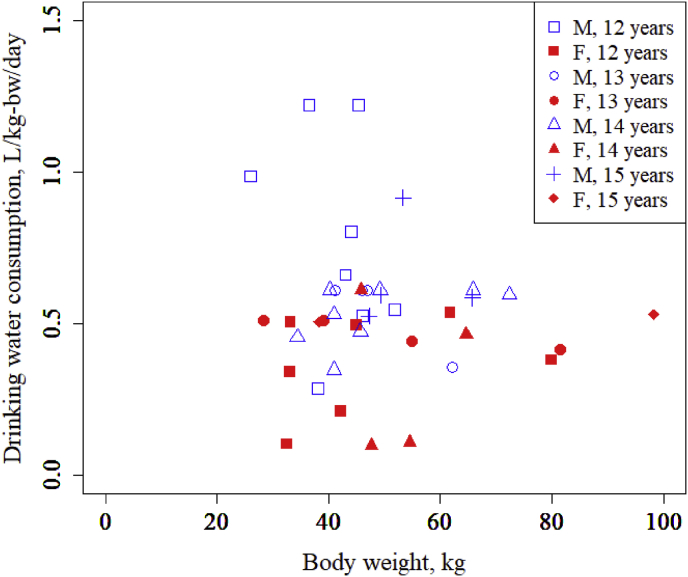

3.6. Drinking water consumption of the students at Banbuakkhang School

Fig. 10 shows the drinking water consumption of the Banbuakkhang School students, who consumed a wide range of water volumes; some students drank more than 1 L, while other students drank less than 0.3 L. The students' drinking water consumption did not significantly correlate with their body weight (p > 0.05) or age (p > 0.05).

Fig. 10.

Relationship between drinking water consumption and body weight for the students at Banbuakkhang School (n = 41).

Overall, the students can be divided into three groups based on their drinking water consumption: less than 0.3 L, between 0.4 and 0.6 L, and more than 0.8 L. The students who consumed less than 0.3 L were all female students, while those who consumed more than 0.8 L were all male students, mostly 12 years old; both male and female students consumed between 0.4–0.6 L of water. Only male students of the same age, i.e. 12 years old, consumed more than 1 L. A previous study reported that people who perform 150 minutes per week of moderate physical activity consumed significantly more water because of dehydration than people who undertake less physical activity (Goodman et al., 2013).

The female students consumed nearly the same amount of drinking water irrespective of body weight, which may be the result of their group cohesiveness. Although female subjects in their teens consumed more water than male subjects of the same age at home (Fig. 5), this was not the case in school. Thus, water consumption at home was more significant for female students, whereas some male students consumed significantly large volumes of water at school.

The students at Banbuakkhang School used to drink tap water from the VWWs; however, now that RO-treated bottled water has been made available, fluoride intake from drinking water has been minimized when they drink water at school.

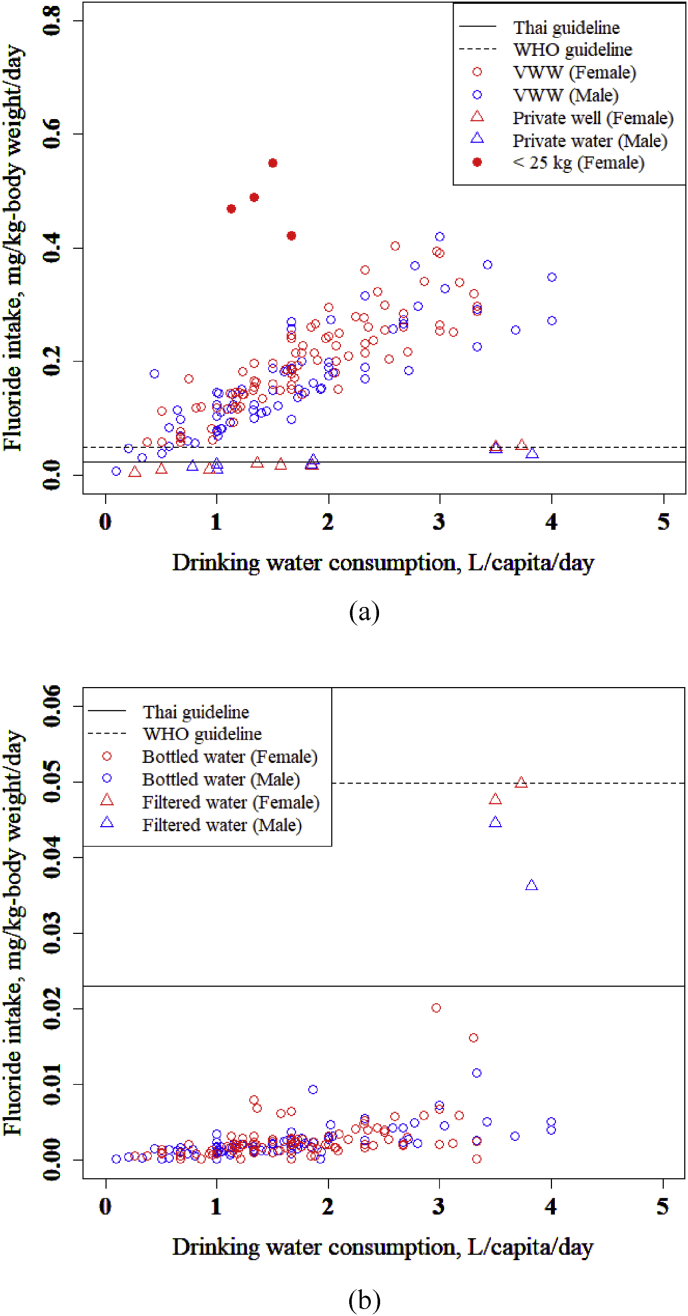

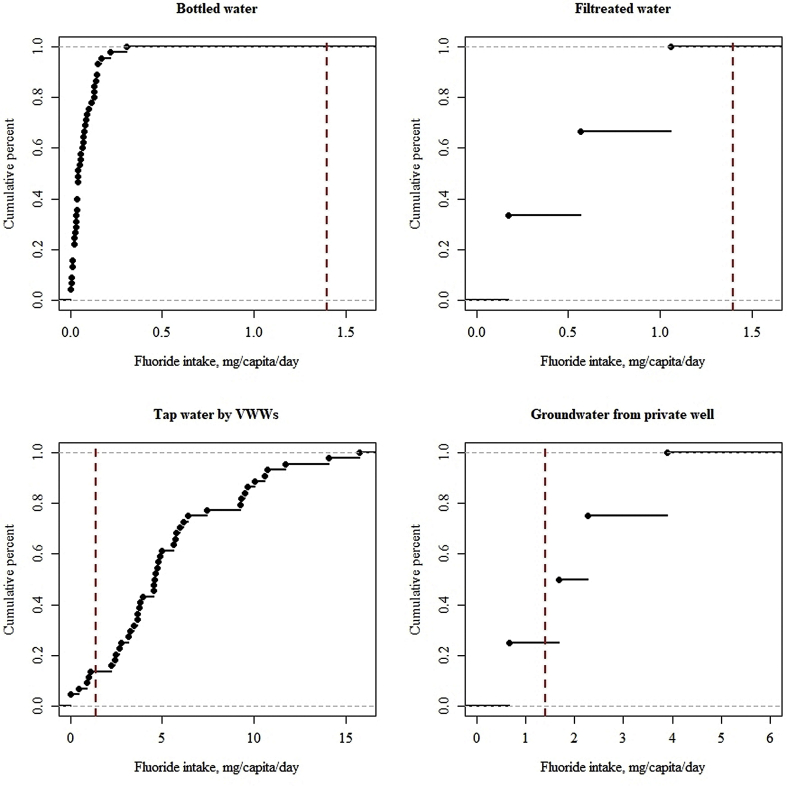

3.7. Estimation of fluoride intake from drinking water consumption

Previous studies reported the daily exposure to fluoride of an individual, i.e. chronic daily intake (CDI), assuming water consumption of 2 L/day for adults and 1 L/day for children, and average body weights of 70 kg for adults and 15 kg for children (Amalraj and Pius, 2013; Ahada and Suthar, 2017); this study calculated fluoride intake based on direct measurements of the water consumption and body weight of each subject as it is suggested to be preferable by WHO (2017). We estimated subjects' fluoride intake prior to drinking exclusively bottled water by assuming that people drank tap water from the VWWs or their private wells in the same volume as they drank bottled water during the survey. Fig. 11a shows that before bottled water was made available to the local population, most subjects used to intake significantly greater amounts of fluoride (0.18 ± 0.10 mg/kg-body weight/day) than the fluoride intake calculated from the Thai drinking water standard (0.023 mg/kg-body weight/day) and the RfD set by the US EPA (0.06 mg/kg-body weight/day). As shown by the plots in Fig. 11a, the female subjects tended to intake more fluoride per kilogram of body weight than the male subjects because of their lower body weights, which indicates that females are exposed to more fluoride than males. The upper outliers in Fig. 11a are the subjects with very low body weights whose fluoride intake per kilogram of body weight were higher than the average-weight subjects who consumed nearly the same volume of water. The subjects who previously drank tap water from their private well (see the lower outlier dots in Fig. 11a) ingested less fluoride than the other subjects because their groundwater contains less fluoride than the VWWs.

Fig. 11.

Drinking water consumption and fluoride intake by drinking water from: (a) tap water (n = 183, estimated consumption); (b) bottled water and filtered water (n = 183, actual consumption).

The fluoride intake from drinking bottled water or filtered water – the current sources of drinking water – were estimated (Fig. 11b) and compared to the fluoride intake from drinking the tap water distributed by the VWWs (Fig. 11a). Most of the subjects preferred drinking bottled water to tap water despite the higher cost; consequently, their fluoride intake was reduced to 0.002 ± 0.002 mg/kg-body weight/day, which is much less than the value calculated from the Thai drinking water guideline assuming subjects consume 2 LCD (0.023 mg/kg-body weight/day). However, the subjects who drank filtered water ingested more than 0.023 mg/kg-body-weight/day of fluoride (the triangle outlier points in Fig. 11b). Therefore, the RO filter units installed in houses did not remove sufficient amounts of fluoride (Table 3). The fluoride removal efficiency of RO membranes depends on maintenance of the filters, which must be done in each household; hence, we cannot expect high fluoride removal rates by household water treatment units.

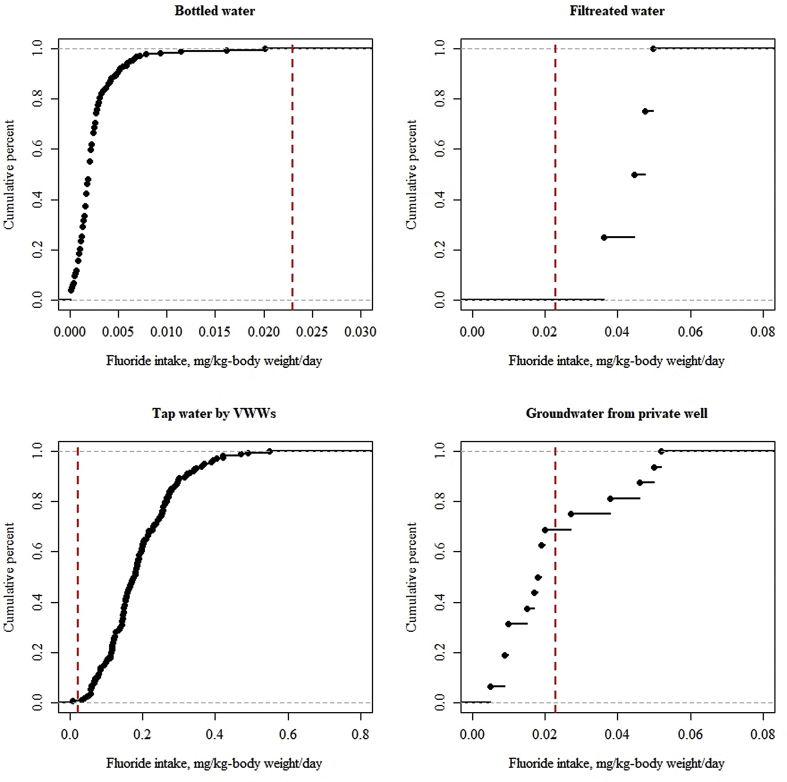

Fig. 12 compares the fluoride intake per kilogram of body weight from drinking bottled water and filtered water with those from drinking tap water distributed by the VWWs. Before the bottled water delivery service was made available, most of the subjects drank tap water supplied by the VWWs. When drinking this tap water, 95.1% of the subjects ingested amounts of fluoride above the Thai guideline value of 0.023 mg/kg-body weight/day, and the highest 0.55% is expected to have ingested more than 0.5 mg/kg-body weight/day of fluoride; this is equivalent to 30 mg/capita/day of fluoride for a person weighing 60 kg. Currently, most of the subjects, including these highest intake groups, use bottled water for drinking and cooking and their fluoride intake has been reduced to less than 0.023 mg/kg-body weight/day. The fluoride intake of the 97.8% of subjects who used bottled water for drinking was estimated to be reduced by 90.4–99.9%. However, 2.2% of the subjects drank filtered water, which only removed 20–60% of fluoride because the unit of household water treatment was so ineffective, and their fluoride intake was above the Thai guideline value.

Fig. 12.

Estimated fluoride intake from drinking bottled water, filtrated water, tap water and groundwater from private well (n = 183). The red dashed line is the Thai guideline value.

3.8. Fluoride intake from cooking water

Since it was not possible to estimate the cooking water consumption of each household member, we assumed that all members in each household consumed the same amount of cooking water per day. In this study, cooking water included only directly ingested water and did not included drained water, such as water for dish washing. Figs. S4a and S4b present each household's fluoride intake from cooking water, assuming that the household used either VWWs tap water or bottled water for cooking. Comparing these figures, using bottled water for cooking reduced a household's fluoride intake to nearly 1% of that using the VWWs tap water.

Fig. 13 shows the fluoride intake per capita per day, assuming that either the VWWs tap water or bottled water was used for cooking. While fluoride intake from drinking water was reported as mg/kg-body weight/day, fluoride intake from cooking water was reported as mg/capita/day because we have to assume average consumption of cooking water by each household member. The maximum intake of fluoride from cooking water was 16.0 mg/capita/day, which is approximately half of the maximum fluoride intake from drinking water (30.0 mg/capita/day). When the bottled water delivery service was not available, subjects in 70.8% of the households ingested more fluoride from cooking water only than the WHO guideline value (3 mg/capita/day), while 87.5% ingested more than the Thai guideline value (1.4 mg/capita/day). However, 89.6% of the households in this area use bottled water for cooking, which reduces their fluoride intake by 84.3–99.9% (Fig. 13). Accordingly, fluoride intake decreased from 5.55 ± 3.52 mg/capita/day when using VWWs tap water for cooking to 0.07 ± 0.05 mg/capita/day by using the delivered bottled water. As a result, all subjects ingested much less than 3 mg/capita/day of fluoride from cooking water.

Fig. 13.

Estimated fluoride intake from cooking water using bottled water, filtrated water, tap water and groundwater from private well (n = 48 households). The red dashed line is the Thai guideline value.

As shown in the preceding and this section, the majority of the residents preferred bottled water for drinking and cooking to tap water supplying fluoride-containing groundwater. Thus, it was verified that the price difference between tap water (0.005 Baht/L or 5 Baht/m3) and bottled water (1.25 Baht/L) did not significantly influence residents' choice of water for drinking and cooking.

4. Discussion

The best way to reduce fluoride intake is to consume fluoride-free or low-fluoride water. Rainwater is fluoride-free, but rainwater can only be obtained during rainy seasons and can be contaminated with pathogens. Hence, disinfection processes such as heat treatment or chlorination are required before rainwater can be consumed (De Kwaadsteniet et al., 2013). Several methods can reduce the fluoride concentration of drinking water, e.g., chemical coagulation or bone char adsorption (Atasoy et al., 2013, 2016; Atasoy and Yesilnacar, 2017a, 2017b; Yadav et al., 2018). These methods are easy to operate and low-cost, but they have some drawbacks, including the production of large amounts of sludge and/or waste, high level of water hardness after chemical dosage, and unpleasant water color and odor (Jadhav et al., 2015; Waghmare and Arfin, 2015). Furthermore, specific conditions are required to produce the adsorbents, i.e., charcoal or bone char, that remove fluoride from water (Rojas-Mayorga et al., 2013; Wendimu et al., 2017).

Household water treatment to remove fluoride requires a RO membrane unit, which is relatively expensive and difficult to maintain properly, as was found in this study. Bottled water is now very popular in countries and regions where piped water is not accessible or safe to drink. While bottled water supplies a finite unit for consumption, water bottles are reused in many developing countries. Bottled water delivery businesses are often operated by private enterprises, but they may be run by public entities or cooperatives in some cases. Thus, bottled water delivery has become a viable alternative for reducing fluoride intake from drinking fluoride-containing groundwater.

In this study, we estimated the effectiveness of reducing fluoride intake by making bottled water available. Of the 183 subjects, 97.8% used bottled water for drinking and 89.6% used it for cooking, which proves that delivering RO-treated bottled water may be an effective strategy for reducing fluoride intake. The bottled water contained low levels of fluoride (<0.7 mg/L) and was widely accepted by the local residents. Because the RO plant was operated by residents of Buak Khang Subdistrict, the price of bottled water (25 Baht/20 1-L bottles or 1.25 Baht/L) was less than the price of commercial bottled water produced by a factory in the city (6 Baht/1-L bottle); however, the cost was significantly higher than that of the VWW tap water (5 Baht/m3). The monthly expenditure in Baht on drinking water based on drinking water consumption data in this study was 65.5 ± 31.9 Baht/month. Although the RO filtration plant had a high installation cost and low water production capacity (Bejaoui et al., 2014), it can reduce the fluoride concentration of tap water from VWWs in the Buak Khang area (>5 mg/L) to meet the Thai guideline value for drinking water (0.7 mg/L). Thus, with the National Government's subsidy for the installation cost of the RO plant, the RO plant can be operated and financially managed by the local community and can deliver fluoride-free bottled water to the residents who have suffered from high fluoride intake for a long time.

5. Conclusions

In order to estimate the reduction to fluoride intake achieved by using bottled water for drinking and cooking, the residents' actual drinking and cooking water consumption was quantified in Buak Khang Subdistrict, Thailand, where the local people have used tap water sourced from fluoride-containing groundwater for drinking and cooking. The effects of the subjects' physical attributes and activities, such as sex, age, body weight, and time spent at home, on drinking water consumption were also investigated.

-

(1)

The average drinking water consumption per capita per day was 1.69 ± 0.78 LCD on weekdays and 1.79 ± 0.92 LCD on weekends, while the average cooking water consumption per household per day was 3.80 ± 1.90 LHD on weekdays and 5.06 ± 3.40 LHD on weekends.

-

(2)

Sex and day of the week had no significant effect on water consumption per capita per day. However, body weight was the main factor affecting drinking water consumption. Low body-weight groups, such as females, children, and the elderly, were found to drink more water in terms of volume per kilogram of body weight per day, and thus were considered to be high risk groups for fluoride intake.

-

(3)

The cooking water consumption varied significantly with the number of household members and the household eating customs, such as cooking in house or bringing back prepared food purchased in shops. On average, the cooking water consumption per capita was estimated to be approximately half the drinking water consumption per capita, but it went up to 1.5 times on weekends. Thus, it was found to be important to take both drinking and cooking water consumption into consideration for estimation of the total water consumption.

-

(4)

Most of the subjects selected bottled water containing low levels of fluoride (0.07 ± 0.05 mg/L) for drinking (97.8%) and cooking (89.6%) over fluoride-containing tap water (5.94 ± 0.29 mg/L). The price difference between tap water (0.005 Bath/L or 5 Bath/m3) and bottled water (1.25 Bath/L) did not significantly influence residents' choice of water for drinking and cooking. Thus, delivering RO-treated bottled water was found to be an effective and viable strategy to mitigate health risks from consuming high levels of fluoride, which is of particular concern to fluoride-contaminated areas in developing countries such as Thailand.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

S. Takizawa: Conceived and designed the experiments; Wrote the paper.

B. Sawangjang: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

T. Hashimoto: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

A. Wongrueng: Performed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

S. Wattanachira: Conceived and designed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (No. 26303013, No. 704 17H04587) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS).

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

The 2016 University of Tokyo Fellowship (Special Scholarships for International Students) is greatly appreciated for supporting this study. The assistance provided by the graduate students at Chiang Mai University and the teachers of Banbuakkhang School during the field survey is also acknowledged.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- Abbasnia A., Alimohammadi M., Mahvi A.H., Nabizadeh R., Yousefi M., Mohammadi A.A., Pasalari H., Mirzabeigi M. Assessment of groundwater quality and evaluation of scaling and corrosiveness potential of drinking water samples in villages of Chabahr city, Sistan and Baluchistan province in Iran. Data Brief. 2018;16:182–192. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2017.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abiye T., Bybee G., Leshomo J. Fluoride concentrations in the arid Namaqualand and the Waterberg groundwater, South Africa: understanding the controls of mobilization through hydrogeochemical and environmental isotopic approaches. Gr. Sustain. Dev. 2018;6:112–120. [Google Scholar]

- Ahada C.P.S., Suthar S. Assessment of human health risk associated with high groundwater fluoride intake in southern districts of Punjab, India. Expo. Health. 2017;1–9 doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-2581-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali S., Thakur S.K., Sarkar A., Shekhar S. Worldwide contamination of water by fluoride. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2016;14:291–315. [Google Scholar]

- Amalraj A., Pius A. Health risk from fluoride exposure of a population in selected areas of Tamil Nadu South India. Food Sci. Human Wellness. 2013;2:75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Areerachakul N. vol. 7(2) 2013. pp. 1553–1560. (Overviews of rainwater harvesting and utilization in Thailand : Bangsaiy Municipality). [Google Scholar]

- Atasoy A.D., Yesilnacar M.I. Assessment of iron oxide and local cement clay as potential fluoride adsorbents. Environ. Protect. Eng. 2017;44(2):109–118. [Google Scholar]

- Atasoy A.D., Yesilnacar M.I. The hydrochemical occurrence of fluoride in groundwater and its effect on human health: a case study from Sanliurfa, Turkey. Environ. Ecol. Res. 2017;5(2):167–172. [Google Scholar]

- Atasoy A.D., Yesilnacar M.I., Sahin M.O. Removal of fluoride from contaminated ground water using raw and modified bauxite. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2013;91(5):595–599. doi: 10.1007/s00128-013-1099-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atasoy A.D., Yesilnacar M.I., Yazici B., ŞAHİN M.Ö. Fluoride in groundwater and its effects on human dental health. World J. Environ. Res. 2016;6(2):51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Augustsson A., Berger T. Assessing the risk of an excess fluoride intake among Swedish children in households with private wells — expanding static single-source methods to a probabilistic multi-exposure-pathway approach. Environ. Int. 2014;68:192–199. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2014.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee A. Groundwater fluoride contamination: a reappraisal. Geosci. Front. 2015;6(2):277–284. [Google Scholar]

- Barraj L., Scrafford C., Lantz J., Daniels C., Mihlan G. Within-day drinking water consumption patterns: results from a drinking water consumption survey. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2009;19:382–395. doi: 10.1038/jes.2008.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejaoui I., Mnif A., Hamrouni B. Performance of reverse osmosis and nanofiltration in the removal of fluoride from model water and metal packaging industrial effluent. Separ. Sci. Technol. 2014;49:1135–1145. [Google Scholar]

- Bhowmick S., Pramanik S., Singh P., Mondal P., Chatterjee D., Nriagu J. Arsenic in groundwater of West Bengal, India: a review of human health risks and assessment of possible intervention options. Sci. Total Environ. 2018;612:148–169. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.08.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brindha K., Elango L. Fluoride in groundwater: causes, implications and mitigation measures. In: Monroy S.D., editor. 2011. pp. 111–136. (Fluoride Properties, Applications and Environmental Management). [Google Scholar]

- Chuah C.J., Lye H.R., Ziegler A.D., Wood S.H., Kongpun C., Rajchagool S. Fluoride: a naturally-occurring health hazard in drinking-water resources of Northern Thailand. Sci. Total Environ. 2016;545–546:266–279. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.12.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerklewski F.L. Fluoride bioavailability—nutritional and clinical aspects. Nutr. Res. 1997;17:907–929. [Google Scholar]

- Craig L., Lutz A., Berry K.A., Yang W. Recommendations for fluoride limits in drinking water based on estimated daily fluoride intake in the Upper East Region, Ghana. Sci. Total Environ. 2015;532:127–137. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.05.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Kwaadsteniet M., Dobrowsky P.H., Van Deventer A., Khan W., Cloete T.E. Domestic rainwater harvesting: microbial and chemical water quality and point-of-use treatment systems. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2013;224:1629. [Google Scholar]

- Dehbandi R., Moore F., Keshavarzi B. Geochemical sources, hydrogeochemical behavior, and health risk assessment of fluoride in an endemic fluorosis area, central Iran. Chemosphere. 2018;193:763–776. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman A.B., Blanck H.M., Sherry B., Park S., Nebeling L., Yaroch A.L. Behaviors and attitudes associated with low drinking water intake among US adults, food attitudes and behaviors survey, 2007. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2013;10 doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guissouma W., Hakami O., Al-Rajab d, A.J., Tarhouni J. Risk assessment of fluoride exposure in drinking water of Tunisia. Chemosphere. 2017;177:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S., Banerjee S. Fluoride accumulation in crops and vegetables and dietary intake in a fluoride-endemic area of West Bengal. Fluoride. 2011;44(3):153–157. [Google Scholar]

- Heller K.E., Sohn W., Burt B.A., Eklund S.A. Water consumption in the United States in 1994–96 and implications for water fluoridation policy. J. Public Health Dent. 1999;59(1) doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1999.tb03228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain M.A., Rahman M.M., Murrill M., Das B., Roy B., Dey S., Maity D., Chakraborti D. Water consumption patterns and factors contributing to water consumption in arsenic affected population of rural West Bengal, India. Sci. Total Environ. 2013;463–464:1217–1224. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.06.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hybel A.M., Godskesen B., Rygaard M. Selection of spatial scale for assessing impacts of groundwater-based water supply on freshwater resources. J. Environ. Manag. 2015;160:90–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadhav S.V., Bringas E., Yadav G.D., Rathod V.K., Ortiz I., Marathe K.V. Arsenic and fluoride contaminated groundwaters: a review of current technologies for contaminants removal. J. Environ. Manag. 2015;162:306–325. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones A.Q., Dewey C.E., Doré K., Majowicz S.E., McEwen S.A., Waltner-Toews D. Drinking water consumption patterns of residents in a Canadian community. J. Water Health. 2006:125–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi S., Hlaing T., Whitford G.M., Compston J.E. Skeletal fluorosis due to excessive tea and toothpaste consumption. Osteoporos. Int. 2011;22(9):2557–2560. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1428-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavouras S.A., Bougatsas D., Johnson E.C., Arnaoutis G., Tsipouridi S., Panagiotakos D.B. Water intake and urinary hydration biomarkers in children. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017;71:530–535. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2016.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P., He X., Li Y., Xiang G. Occurrence and health implication of fluoride in groundwater of loess aquifer in the Chinese loess plateau: a case study of Tongchuan, northwest China. Expo. Health. 2018:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Liu G., Ye Q., Chen W., Zhao Z., Li L., Lin P. Study of the relationship between the lifestyle of residents residing in fluorosis endemic areas and adult skeletal fluorosis. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2015;40(1):326–332. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2015.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrady M., Ellwood R., Srisilapanan P., Korwanich N., Taylor A., Goodwin M., Pretty I. Dental fluorosis in populations from Chiang Mai, Thailand with different fluoride exposures--Paper 2: the ability of fluorescence imaging to detect differences in fluorosis prevalence and severity for different fluoride intakes from water. BMC Oral Health. 2012;12:33. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-12-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer G.W., Counselor A., Sirikeratikul S. Thailand Thai FDA revising pesticide MRLs in foods. Policy. 2009;0–2 [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Public Health, Department of Health, Thailand . 2010. Drinking Water Standards. [Google Scholar]

- Mohebbi M.R., Saeedi R., Montazeri A., Vaghefi K.A., Labbafi S., Oktaie S., Abtahi M., Mohagheghian A. Assessment of water quality in groundwater resources of Iran using a modified drinking water quality index (DWQI) Ecol. Indicat. 2013;30:28–34. [Google Scholar]

- Namkaew M., Wiwatanadate P. Association of fluoride in water for consumption and chronic pain of body parts in residents of San Kamphaeng district, Chiang Mai, Thailand. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 2012;17(9):1171–1176. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.03061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro O., González J., Júnez-Ferreira H.E., Bautista C.F., Cardona A. Correlation of Arsenic and Fluoride in the groundwater for human consumption in a semiarid region of Mexico. Proc. Eng. 2017;186:333–340. [Google Scholar]

- Oganessian E., Ivancakova R., Lencova E., Broukal Z. Alimentary fluoride intake in preschool children. BMC Public Health. 2011;11 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paz S., Jaudenes J.R., Gutiérrez A.J., Rubio C., Hardisson A., Revert C. Determination of fluoride in organic and non-organic wines. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2017;178:153–159. doi: 10.1007/s12011-016-0910-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen P.E., Ogawa H. Prevention of dental caries through the use of fluoride – the WHO approach. Commun. Dent. Health. 2016;33:66–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phromsakha Na Sakonnakhon C., Chumnanpai S., Inta P. 2018. Report Title: “Solving Evaluation the High Fluoride Concentration in Drinking Watering Chiang Mai.http://icoh.anamai.moph.go.th/ewt_dl_link.php?nid=378 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Pramanik S., Saha D. The genetic influence in fluorosis. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2017;56:157–162. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2017.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravenscroft P., Brammer H., Richards K. 2009. Arsenic Pollution: A Global Synthesis (First) [Google Scholar]

- Rojas-Mayorga C.K., Bonilla-Petriciolet A., Aguayo-Villarreal I.A., Hernández-Montoya V., Moreno-Virgen M.R., Tovar-Gómez R., Montes-Morán M.A. Optimization of pyrolysis conditions and adsorption properties of bone char for fluoride removal from water. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis. 2013;104:10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Roy S., Dass G. Fluoride contamination in drinking water – a review. Resour. Environ. 2013;3(3):53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Samal A.C., Bhattacharya P., Mallick A., Ali M.M., Pyne J., Santra S.C. A study to investigate fluoride contamination and fluoride exposure dose assessment in lateritic zones of West Bengal, India. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2015;22:6220–6229. doi: 10.1007/s11356-014-3817-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Säve-Söderbergh M., Toljander J., Mattisson I., Åkesson A., Simonsson M. Drinking water consumption patterns among adults - SMS as a novel tool for collection of repeated self-reported water consumption. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2018;28(2):131–139. doi: 10.1038/jes.2017.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma D., Singh A., Verma K., Paliwal S., Sharma S., Dwivedi J. Fluoride: a review of pre-clinical and clinical studies. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2017;56:297–313. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2017.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stookey J.D., König J. Describing water intake in six countries: results of Liq.In7 surveys, 2015–2018. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018;57(S3):35–42. doi: 10.1007/s00394-018-1746-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K., Akiniwa K., Narita K. Regression Analysis of Cancer Incidence Rates and Water Fluoride in the U.S.A. based on IACR/IARC (WHO) Data (1978-1992) Canc. Incidence Water Fluoridation U.S.A. 2001;11(No. 4):170–179. doi: 10.2188/jea.11.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda T., Takizawa S. Health risks of fluoride in the Chiang Mai Basin, Thailand. In: Takizawa S., editor. Groundwater Management in Asian Cities: Technology and Policy for Sustainability. Springer; Japan: 2008. pp. 301–327. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton S.N. Increased Hydration Can Be Associated with Weight Loss. Front. Nutr. 2016;3:18. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2016.00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieux F., Maillot M., Constant F., Drewnowski A. Water and beverage consumption patterns among 4 to 13-year-old children in the United Kingdom. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:479. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4400-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waghmare S.S., Arfin T. Fluoride removal from water by various techniques - review. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2015;2(9):560–571. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe C., Kawata A., Sudo N., Sekiyama M., Inaoka T., Bae M., Ohtsuka R. Water intake in an Asian population living in arsenic-contaminated area. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2004;198:272–282. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2003.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendimu G., Zewge F., Mulugeta E. Aluminium-iron-amended activated bamboo charcoal (AIAABC) for fluoride removal from aqueous solutions. J. Water Proc. Eng. 2017;16:123–131. [Google Scholar]

- WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva: 1996. Trace Elements in Human Nutrition and Health World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- WHO . 2017. Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality: Fourth Edition Incorporating the First Addendum. Geneva. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood S.H., Singharajwarapan F.S. Geothermal Systems of Northern Thailand and Their Association With Faults Active During the Quaternary. GRC Trans. 2014;38:607–615. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav K.K., Gupta N., Kumar V., Khan S.A., Kumar A. A review of emerging adsorbents and current demand for defluoridation of water: Bright future in water sustainability. Environ. Int. 2018;111:80–108. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2017.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeşilnacar M.İ., Yetiş A.D., Dülgergil Ç.T., Kumral M., Atasoy A.D., Doğan T.R., Tekiner S.İ., Bayhan İ., Aydoğdu M. Geomedical assessment of an area having high-fluoride groundwater in southeastern Turkey. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016;75(2):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Yousefi M., Ghoochani M., Mahvi A.H. Health risk assessment to fluoride in drinking water of rural residents living in the Poldasht city, Northwest of Iran. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018;148:426–430. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2017.10.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuyan X., Hua H., Qibing Z., Chun Y., Maolin Y., Feng H., Peng L., Xueli P., Alihua Z. The effect of elemental content on the risk of dental fluorosis and the exposure of the environment and population to fluoride produced by coal burning. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2017;56:329–339. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2017.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Huang D., Yang J., Wei X., Qin J., Ou S., Zhang Z., Zou Y. Probabilistic risk assessment of Chinese residents' exposure to fluoride in improved drinking water in endemic fluorosis areas. Environ. Pollut. 2017;222:118–125. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.12.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.