Abstract

Introduction

This randomized, double-blind trial aimed to test effect of a Chinese herbal medicine, Qinggongshoutao (QGST) pill, on the cognition and progression of amnestic mild cognitive impairment (aMCI).

Methods

Patients with aMCI were randomly assigned to receive QGST, Ginkgo biloba extract, or placebo for 52 weeks. The primary outcome measures were progression to possible or probable Alzheimer's disease (AD) and change in Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale–cognitive subscale scores; secondary outcome measures included assessments for cognition and function.

Results

Total 350 patients were enrolled, possible or probable AD developed in 10. There were significant differences in the probability of progression to AD in the QGST group (1.15%) compared with placebo group (10%). There was significant difference in Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale–cognitive subscale scores in favor of QGST over the placebo group. Secondary outcome measure (Mini-Mental State Examination) also showed benefit in QGST at end point.

Discussion

In patients with aMCI, QGST showed lower AD progression rate than placebo at 8.85%, and may have benefit on global cognition.

Keywords: Amnestic mild cognitive impairment, Herbal medicine, Efficacy, Randomized clinical trial

1. Introduction

As the population of older people grows, dementia is becoming a challenging issue of global health and economy. It was estimated that 35.6 million people lived with dementia worldwide in 2010, with numbers expected to almost double every 20 years [1]. Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the most popular type of dementia, AD now affects about 6.25/1000 people per year in China [2]. The costs projected for care of dementias will increase over 330% by 2050 reported by Alzheimer's Association barring effective preventions or breakthrough treatments [3]. However, well-studied conventional treatments for AD are generally considered to be symptom-relieving rather than disease-modifying. Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a transitional state between the cognitive changes of normal aging and early AD [4]. Amnestic mild cognitive impairment (aMCI) is believed to be a precursor to AD and to progress to clinically diagnosable AD at a rate of approximately 10% to 15% per year, significantly higher than in the normal elderly [5]. Hence, aMCI is generally recognized as a treatment target for AD [6]. However, no high-quality evidence exists to support pharmacological treatments for MCI so far [7]. Ginkgo biloba extract (EGb761) is widely used for the treatment of MCI in China. However, regarding the efficacy of EGb761 to reduce the overall incidence rate of dementia, the results were not consistent [8], [9].

According to traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), memory decline and dementia are believed to be caused by a deficiency of kidney essence (Shenxu in Chinese), and the treatment approach is to supplement kidney essence, as described in the Complete Works of Jingyue (published in 1624). Qinggongshoutao (QGST) formulation, a traditional herbal pill that was originally derived from the Qing Dynasty Medical Archives of Emperor Qianlong, appears to serve the function. QGST is being used to treat symptoms, such as forgetfulness, backache, knee weakness, and urinary incontinence. Experimental studies suggest that QGST have multifaceted functions, including antioxidation, neuroprotection, and improvement of memory [10]. Up until now, there has been no well-controlled clinical trial to assess QGST for the treatment of dementia. The present study was designed to determine whether treatment with QGST can delay the clinical onset of AD in people with aMCI, as compared with EGb761 and placebo, and investigate further the effects of QGST on cognitive function.

2. Methods

As one of Chinese Alzheimer's Disease Research on Medicinal Products projects, this trial was conducted in 17 centers in China. The patients were required to meet the diagnostic criteria for aMCI [4]. The operational aMCI inclusion criteria were showed as follows: (1) memory complaints that were corroborated by an informant; (2) abnormal memory function as assessed by the Chinese version of the Adult Memory and Information Processing Battery Logical Memory Delayed Story Recall (AMIPB-DSR) subtest score of <15.5 for age (age 50-64 years < 15.5, 65-74 years < 12.5, and over 75 years < 10) [11]; (3) normal general cognitive function as determined by a clinician's judgment based on a structured interview with the patients, a Mini–Mental State Examination (MMSE) score of 24 to 30 for education [12], and Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) Scale score = 0.5, with the memory domain = 0.5 or 1, and no other domain greater than 1 [13]; (4) no or minimal impairments in activities of daily living as determined by a clinical interview with the patient and an informant, a score of 38 to 52 on the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study–Activities of Daily Living Scale for patients with MCI (ADCS-ADL-MCI-24 items) [14]; (5) absence of dementia judged by an experienced clinician, including no impairment of cognitive function that would meet the core clinical criteria of the National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer's Association workgroups [15]; (6) the patients were required to have adequate vision and hearing to participate in the study assessments; (7) all patients and legal guardians should provide written consent; and (8) deficiency of kidney essence to be confirmed using the kidney deficiency scale from the pattern elements scale ≥7 points [16].

Detailed exclusion criteria comprised the following: (1) nonamnestic MCI; (2) meeting the diagnostic criteria for dementia; (3) cognitive impairment resulting from conditions, such as acute cerebral trauma, cerebral damage due to a lack of oxygen, epilepsy vitamin deficiency, infections such as meningitis or AIDS, significant endocrine or metabolic disease, mental retardation, a brain tumor, or drug abuse or alcohol abuse; (4) having significant psychiatric disease, depression, the Hamilton Depression Scale >12; (5) magnetic resonance imaging scan having showed cerebral infarction, hemorrhage or focal lesions, and infections within 12 months; (6) accompanying poorly controlled diabetes or hypertension or severe arrhythmias; (7) having suffered from heart infarction within 3 months; (8) severe asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; (9) severe indigestion; (10) gastrointestinal tract obstruction or gastroduodenal ulcer; (11) use of cholinesterase inhibitors or memantine within 1 month; (12) history of hypersensitivity to the treatment drugs; (13) use of concomitant drugs with the potential to interfere with cognition, such as anticholinergics, anticonvulsants, antiparkinsonian agents, stimulants, cholinergic agents, antipsychotics, or antidepressants, or anxiolytics; (14) administration of other investigational drugs; (15) severe impairment of the liver or kidney function; and (16) vegetarians or contraindications for animal innards.

2.1. Study design

There was a 2-week run-in period before randomization followed by a 52-week double-blind treatment period. Patients with aMCI were randomly assigned to receive (1) QGST pill (7g per time, twice daily) and EGb761 placebo (2 tablets per time, twice daily); (2) EGb761 tablet (Ginaton) (80 mg per time, twice daily) and QGST placebo (7 g per time, twice daily); or (3) QGST placebo pill (7 g per time, twice daily) and EGb761 placebo (2 tablets per time, twice daily). QGST was supplied by Tianjin Zhongxin Pharmaceutical Group Co., Ltd. Darentang Pharmaceutical Factory (branch number: 141001). EGb761 was supplied by Germany's Dr. Weimar Shu Pei Pharmaceutical Factory (branch number: 5890913), and both placebos for EGb761 (branch number: 5890915) and QGST (branch number: 150101) were supplied by Tianjin Zhongxin Pharmaceutical Group Co., Ltd. The active ingredients of QGST include Ginseng (Renshen in Chinese), Radix Asparagi (Tiandong in Chinese), Radix Ophiopogonis (Maidong in Chinese), Fructus Lyczz (Gouqizi in Chinese), Radux Rehmanniae (Dihuang in Chinese), Radix Angelicae Sinensis (Danggui in Chinese), Alpinia Oxyphylla Miq (Yizhiren in Chinese), Semen Ziziphi Spinosae (Suanzaoren in Chinese), and lignum distraction (Fenxinmu in Chinese). The detailed quality control method for Chinese medicinal preparation of QGST was presented in a China Patent File (CN102048990B) (see https://patents.google.com/patent/CN102048990B/en). To preserve blinding, the placebos of QGST and EGb761 have an identical taste and appearance to the matched drugs. Study visits took place at screening, baseline (week 0), middle points (week 4, 12, 24, 36, 48), and at the end point of treatment (week 52).

2.2. Randomization

This was a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel group study, including a 2-week run-in period followed by a 52-week randomization period. All participants were given EGb761 placebo and QGST placebo during the run-in period, after which the patients were randomly assigned in a 5:3:2 ratio to QGST, EGb761, or placebo. The randomization was stratified by center using the SAS statistical software (version 9.13) (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Balanced randomization generated by the SAS statistical software was carried out in three steps (in blocks of 10) by a statistician with no access to information on the patients or physicians. Patients were sequentially assigned to the lowest randomization number available at the time of each enrollment at each center. The randomized code was generated in the randomization process and sealed in an envelope. Statisticians assigned the medication group according to the randomization code. Blinding was broken only if a patient's trial medication requires specific emergency treatment. Once the blinding was broken, the patient was managed as off-trial. Patients, legal guardian, the study investigator, any other personnel involved in the study, and the investigating staff of sponsor were blinded until all patients complete the study and analysis was completed.

2.3. Sample size

Previous studies showed that Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale–Cognition subscale (ADAS-cog) increased by 0.61 points over 12 months, with a standard deviation of 4.104. We estimated that the sample size of 360 would have 80% power to detect a difference (Cohen's d = 0.5) between the treatment and placebo groups, assuming an expected rate of 20% for missed visits, at a two-sided significance level of 5%. The ratio of the QGST group, EGb761 group, and placebo group was 5:3:2.

2.4. Efficacy measures

The primary outcome measures were the rate of progression to possible or probable AD at end point, defined according to the core clinical criteria of the National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer's Association workgroups [15] and CDR-GS score ≥ 1. The other primary outcome was the change from baseline to 52 weeks in ADAS-cog scores [17], an 11-item scale with scores ranging from 0 to 70 and higher scores indicating more severe cognitive impairment.

Secondary outcome measures included changes from baseline to 52 weeks in the MMSE scores (ranging from 0 to 30) [12], AMIPB-DSR (scores range from 0 to 56) [11], and ADCS-ADL-MCI-24 items (scores range from 0 to 69), with lower scores indicating worse function [14].In addition, the changes in the deficiency of kidney essence using Clinical Global Impression of Change of Kidney Deficiency (CGIC-KDS) was assessed [18]. CGIC-KDS, based on information from a semistructured interview with the patient and the legal guardian, was designed specifically to evaluate the global assessment of changes of kidney function deficiency based on clinician and caregiver in TCM. The CGIC-KDS score ranges from 1 to 7, and the score of 1-3 indicates improvement, 4 means no change, and 5-7 indicates worse [18].

The safety assessment included (1) physical examination and vital signs; (2) electrocardiography; (3) laboratory testing, and (4) documentation of any adverse events (AEs) that occurred during the treatment period, including the severity, time of onset, duration, treatment, and relationship to the tested drugs.

2.5. Oversight

This study was undertaken in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use guidelines for good clinical practice. The study protocol was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Dongzhimen Hospital to Beijing University of Chinese Medicine and the Medical Ethics Committee of the study institutions where this study was conducted. Written informed consent was provided by the patients and their legal representatives. The sponsor (Tianjin Zhongxin Pharmaceutical Group Co., Ltd. Darentang Pharmaceutical Factory) funded the trial and provided tested drugs and placebo. The principal investigator designed the trial in consultation with the academic authors. Data were collected by the investigators, analyzed by the third party, and interpreted by all the authors.

2.6. Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis of efficacy was conducted in two populations: the full-analysis set (FAS) population and the per-protocol set (PPS) population. Safety was analyzed in the safety set. The FAS included patients who received at least one dose of the trial regimen and who had both a baseline outcome measurement and at least one postrandomization outcome measurement. The PPS included patients who completed 52 weeks of the medication with good compliance and with complete data, with no major protocol violations. The ADAS-cog, MMSE, AMIPB-DSR, and ADCS-ADL-MCI-24 were analyzed using a mixed-effects model (MEM); the progression rate of AD, was analyzed using the generalized estimating equation. Both the MEM and the generalized estimating equation of repeated measurements were based on the likelihood estimation. Under the two data missing mechanisms including missing completely at random and missing at random, the missing data filling was not needed and the model could be directly fitted. Therefore, this MEM analysis did not filled in the missing data. The safety set included all patients who received at least one dose of the trial regimen and at least one safety evaluation. All P values were two-tailed, and all analyses were significant if the value was ≤0.05.

3. Results

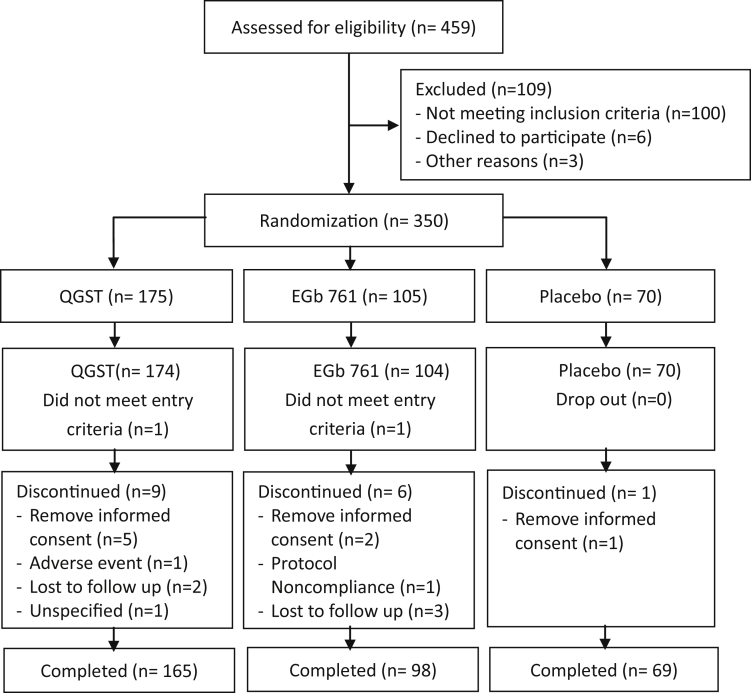

A total of 459 patients were screened, and 350 were randomized between May 2015 and October 2017. Of those 175 received QGST treatment, 105 received EGb761and 70 received placebo, and 1 patient in the QGST group and 1 patient in the EGb761 group did not meet the inclusion criteria and they were excluded from the FAS. Of these 348 patients, 16 discontinued their treatment before week 52, and a total of 332 patients (165 of the patients in the QGST group, 98 in the EGb761 group, and 69 of those in the placebo group) completed the trial and were included in the PPS (Fig. 1). The reason for discontinuing the study was showed in Fig. 1. Nine patients in the QGST group discontinued research (5 patients withdrew the informed consent, 1 patient discontinued because of AEs, 2 lost to follow up, and 1 discontinued with unspecified reason); 6 patients in the EGb761 group discontinued the study (2 patients withdrew the informed consent, 1 patient violated the protocol, and 3 lost to follow up); 1 patient in the placebo group discontinued the study because of withdrawing the informed consent. There were no significant differences between the three groups in dropouts (P = .362).There were no significant differences between the three groups in baseline demographics and neuropsychological test performance (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of enrollment, randomization, and follow-up. Abbreviations: QGST, Qinggongshoutao; EGb761, Ginkgo biloba extract.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants by group

| Characteristic | QGST (n = 174) | EGb761 (n = 104) | Placebo (n = 70) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, male/female | 88/86 | 44/60 | 37/33 | .2970 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 63.17 (6.59) | 64.43 (7.72) | 64.15 (7.25) | .3112 |

| Education, mean (SD) | 9.14 (3.58) | 9.59 (3.69) | 8.91 (3.88) | .4492 |

| Smoking history, yes/no | 45/129 | 20/84 | 18/52 | .4182 |

| Drinking history, yes/no | 46/128 | 20/84 | 18/52 | .3744 |

| Dementia family history, yes/no | 7/167 | 4/100 | 5/65 | .5236 |

| History of stroke, yes/no | 22/152 | 12/92 | 8/62 | .9471 |

| MMSE, mean (SD) | 27.60 (1.41) | 27.74 (1.47) | 27.51 (1.59) | .5837 |

| ADAS-cog, mean (SD) | 12.99 (3.58) | 13.07 (3.74) | 13.23 (3.44) | .8926 |

| CDR-SB, mean (SD) | 3.71 (1.19) | 3.41 (1.30) | 3.67 (1.29) | .1500 |

| AMIPB-DSR, mean (SD) | 11.78 (2.46) | 11.45 (2.46) | 11.69 (2.08) | .5484 |

| ADCS-MCI-ADL-24, mean (SD) | 45.72 (3.91) | 45.45 (4.00) | 46.53 (4.23) | .2052 |

| HIS, mean (SD) | 2.17 (0.80) | 2.14 (0.81) | 2.06 (0.93) | .6441 |

| HAMD, mean (SD) | 5.06 (2.42) | 4.87 (2.43) | 5.01 (2.50) | .8142 |

| DPES-KDS, mean (SD) | 14.74 (4.02) | 14.68 (4.32) | 14.16 (3.79) | .5874 |

Abbreviations: MMSE, Mini–Mental State Examination; ADAS-cog, Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale–cognitive subscale; CDR-SB, Clinical Dementia Rating Scale–sum of boxes; AMIPB-DSR, Adult Memory and Information Processing Battery-Logical Memory Delayed Story Recall; ADCS-ADL-MCI-24, Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study–Activities of Daily Living for mild cognitive impairment-24 items; HIS, Hachinski Ischemia Scale; HAMD, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; DPES-KDS, Pattern Element Scale for Dementia–Subscale of Kidney Deficiency; QGST, Qinggongshoutao; EGb761, Ginkgo biloba extract.

3.1. Primary outcomes

A total of 10 participants had progressed to possible or probable AD at the end point (2 in the QGST group, 1 in the EGb761 group, and 7 in the placebo group), the conversion rate being 1.15% in QGST, 0.96% in EGb761, and 10.0% in placebo, respectively. There was a significant difference between the three groups (P = .001); the frequency of progression to AD was lower in the QGST group than in the placebo group (8.85%). No difference was found between QGST and EGb761.

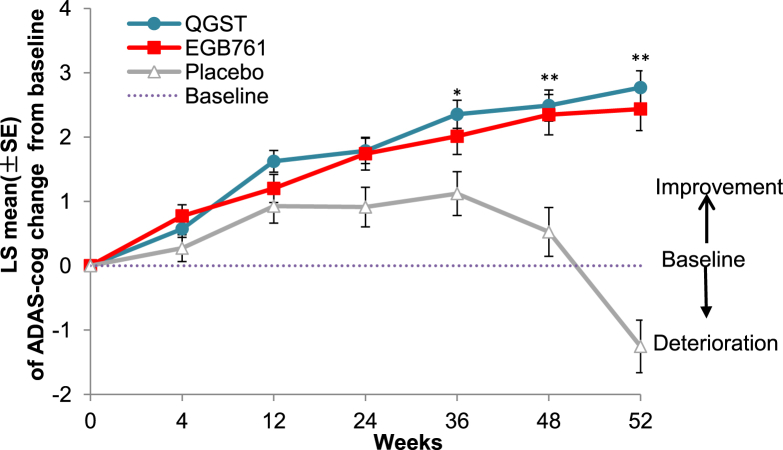

Using the MEM analysis, in the FAS population, there was significant difference in ADAS-cog scores, favoring the QGST over the placebo group (least squares mean change from baseline to the end points: 2.76 in the QGST group, 2.43 in the EGb761 group, and −1.25 in the placebo group; P < .001) (Table 2). The least squares mean changes in the ADAS-cog score in all study groups and at all visits were shown in Fig. 2. From the trend line at different time points, it can be seen that the improvement in ADAS-cog scores was time dependent with no difference before 36 weeks. The responder rate (ADAS-cog change ≥ −4) was significantly higher in the QGST (29.27%, P < .001) and EGb761 (27.84%, P < .001) groups than placebo (5.80%). The results in the PPS population were consistent with the FAS population.

Table 2.

Primary and secondary outcomes at week 52 in groups

| Scale | Week 52 (FAS) |

Week 52 (PPS) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QGST (n = 174) | EGb761 (n = 104) | Placebo (n = 70) | P* | QGST (n = 165) | EGb761 (n = 98) | Placebo (n = 69) | P* | |

| ADAS-cog | 2.76 (0.26) | 2.43 (0.33) | −1.25 (0.40) | <.001 | 2.66 (0.26) | 2.45 (0.34) | −1.22 (0.40) | <.001 |

| CDR-GS > 1, n (%) | 2 (1.15) | 1 (0.96) | 7 (10.00) | .002 | 2 (1.22) | 1 (1.03) | 7 (10.14) | .002 |

| CDR-SB | 0.22 (0.10) | 0.25 (0.13) | −0.02 (0.16) | .064 | 0.20 (0.16) | 0.29 (0.13) | −0.01 (0.16) | .057 |

| MMSE | −0.92 (0.14) | −0.86 (0.18) | 0.25 (0.22) | <.001 | −0.94 (0.14) | −0.88 (0.19) | 0.26 (0.22) | <.001 |

| ADCS-ADL-MCI-24 | −3.02 (0.39) | −2.98 (0.51) | −1.35 (0.61) | .051 | −2.96 (0.40) | −2.97 (0.52) | 1.33 (0.61) | .053 |

| AMIPB-DSR | −3.02 (0.39) | −2.98 (0.51) | −1.35 (0.61) | .196 | −2.96 (0.40) | −2.97 (0.52) | −1.33 (0.61) | .265 |

| CGIC-KDS | 0.57 (0.08) | 0.26 (0.11) | −0.03 (0.14) | .001 | 0.56 (0.08) | 0.28 (0.12) | −0.02 (0.12) | <.001 |

NOTE. * indicates comparison between the three treatment groups. Values are in least squares mean (SE), unless otherwise specified.

Abbreviations: MMSE, Mini–Mental State Examination; ADAS-cog, Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale–cognitive subscale; CDR-SB, Clinical Dementia Rating Scale–sum of boxes; CDR-GS, Clinical Dementia Rating Scale-global score; AMIPB-DSR, Adult Memory and Information Processing Battery-Logical Memory Delayed Story Recall; ADCS-ADL-MCI-24, Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study–Activities of Daily Living for mild cognitive impairment-24 items; CGIC-KDS, Clinical Global Impression of Change of Kidney deficiency; QGST, Qinggongshoutao; EGb761, Ginkgo biloba extract; FAS, full-analysis set; PPS, per-protocol set; SE, standard error.

Fig. 2.

ADAS-cog LS mean change from baseline scores to endpoint in the three groups. Notes: This figure showed the mean least squares change from baseline in the ADAS-cog score; scores range from 0 to 70, with higher scores indicating worse dementia. *P < .05 QGST versus placebo, and **P < .01 QGST versus placebo. Abbreviations: ADAS-cog, Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale–cognitive subscale; QGST, Qinggongshoutao; EGb761, Ginkgo biloba extract; LS, least squares.

3.2. Secondary efficacy outcomes

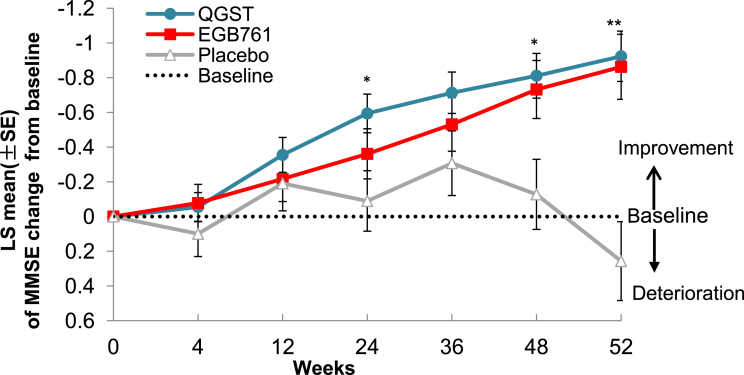

In the MEM analysis (FAS population), there were significant differences in the least squares mean change from baseline scores between the QGST and placebo groups in MMSE. After 52 weeks of treatment, the mean least squares of MMSE in the QGST group was (−0.92) greater than that in the placebo group (0.25, P < .001). There was no significant difference between the QGST and EGb761 groups (−0.86, P = .792) (Fig. 3). There was no significant difference in the least squares mean change from baseline to the end points between the three groups in the ADCS-ADL-MCI-24 (P = .054). We did not observe a significant difference in AMIPB-DSR scores between the three groups.

Fig. 3.

MMSE LS mean change from baseline scores to endpoints in the three groups. Note: This figure showed the mean least squares change from baseline to endpoints in the MMSE score; scores range from 0 to 30, with lower scores indicating worse function. *P < .05 QGST versus placebo, and **P < .01 QGST versus placebo. Abbreviations: MMSE, Mini–Mental State Examination; QGST, Qinggongshoutao; EGb761, Ginkgo biloba extract; LS, least squares.

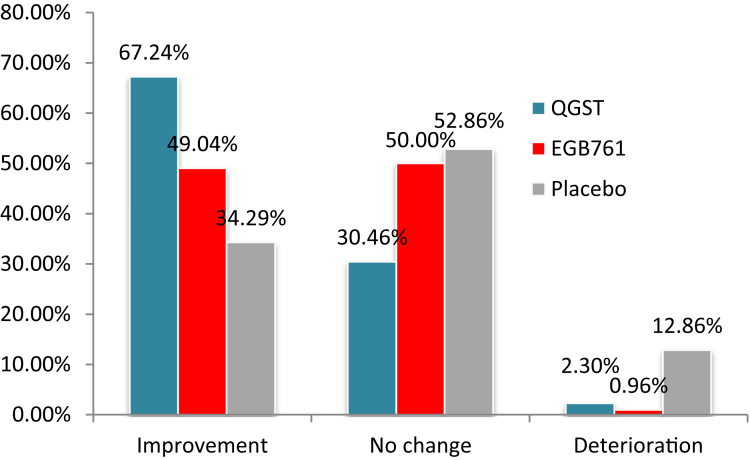

Because QGST is a Chinese herbal medicine that enhances kidney function defined by TCM, we also examined the effect of treatment on changes in CGIC-KDS scores. After 52 weeks of treatment, the rate of improvement in kidney deficiency essence in the QGST group as measured by CGIC-KDS was 67.2%, significantly higher than the EGb761 group (49.0%) and placebo group (34.2%). Significant differences in CGIC-KDS scores between the QGST or EGb761 and placebo groups began at 12 weeks and lasted to 52 weeks; thus, the improvement in CGIC-KDS scores appeared earlier than the improvement in cognitive function (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Between-group comparison of the CGIC-KDS score at 52 weeks. Notes: This figure showed changes in the CGIC-KDS score, which was designed specifically to evaluate global assessment of changes of kidney function deficiency based on clinician and caregiver in traditional Chinese medicine. The CGIC-KDS score ranges from 1 to 7, and the score of 1-3 indicates improvement, 4 means no changed, and 5-7 indicates worse. Abbreviations: CGIC-KDS, Clinical Global Impression of Change of Kidney deficiency; QGST, Qinggongshoutao; EGb761, Ginkgo biloba extract; LS, least squares.

3.3. Safety

All 348 patients in this study received at least one follow-up, and all were included in the safety analysis. A total of 87 (50%) patients in the QGST group had at least one AE during the double-blind period in the safety population, and 43 (41.35%) in the EGb761 group, 30 (42.86%) in the placebo group, with no significant differences among groups (P = .315). The most reported AEs included upper respiratory tract infection, diarrhea, constipation, urinary tract infection, and increased blood glucose. The most frequent AEs assessed as probably related to the study medication were constipation in the QGST group (2 patients) and diarrhea in the EGb761 group, and the constipation led one patient in the QGST group to discontinue the trial. Two of 174 (1.1%) patients in the QGST group and four of 104 (3.8%) in the EGb761 group had at least one serious AE and were hospitalized during the trial. None of the serious AEs led to treatment discontinuation, and all were assessed as not related to the study medication by the investigator. No significant changes from baseline were observed in vital signs, physical examination findings, electrocardiography status, or laboratory values in all three treatment groups.

4. Discussion

According to our previous study, insufficiency of the kidney Qi (flowing energy from kidney) is the characteristic in the early stage of dementia, stagnation of phlegm, blood stasis, and fiery are the characteristics in the middle stage, and excess of toxic heat is the characteristic in the late stage during the AD process. The therapeutic method is the nourishment of the kidney in the early stage, resolution of phlegm, blood stasis, and fiery in the middle stage, and detoxification in the late stage according to a full-course, sequential and disease-syndrome integrated treatment optimization protocol applicable to patients with AD [19]. QGST, an approved Chinese herbal drug by the China FDA, was developed from an ancient herbal prescription. The main effect of QGST pills is to nourish the kidney, and it is used to treat patients with MCI in China.

In recent years, biomarker research has made great progress in AD. However, limited progress has been made in the treatment of AD and several treatments for known pathological markers of AD have failed [20], [21], [22]. Two different Aβ antibodies (solanezumab and verubecestat) did not reduce cognitive or functional decline in patients with mild-to-moderate AD [23], [24]. As known, AD is a complex systemic disease with multiple etiologies and pathophysiology at different stage of disease [25]. Herbal formulations may have advantages with multiple target regulation compared with the single target antagonist in the view of TCM [26]. QGST is a compound containing multiple active components that may have an effect on multiple targets for AD. Studies have shown that QGST has ginseng- or ginsenosides-mediated neuroprotective mechanisms, including maintaining homeostasis, and antiinflammatory, antioxidant, antiapoptotic, and immune-stimulatory activities, and antiinflammatory seem contradictory; all of which may suggest a potential benefit in neurodegenerative disease, such as AD [27]. Other components, such as Angelica sinensis and Rehmannia glutinosa, may also have potential neuroprotective effects and antiaging effects and reduce plasma lipid peroxide [28], [29]. These pharmacological findings support the clinical observation, i.e., prevent progression of AD and decline of cognition in the present study.

In this study, the rate of conversion to AD from aMCI in the placebo group was 10% at week 52 and this was consistent with a meta-analysis, which showed a cumulative dementia incidence of 14.9% in individuals with MCI older than 65 years and followed up for 2 years [7]. The study finding on AD progression was also consistent with another study showing that a rate of progression from MCI to AD of 10 to 15 percent per year [5]. With the rate of ∼1%, our results showed that QGST and EGb761 were effective in preventing or delaying the onset of AD in participants with aMCI. A meta-analysis has also shown that EGb761 at 240 mg/day was able to stabilize or slow the decline in cognition, function, behavior, and global change at 22-26 weeks in cognitive impairment and dementia, especially for patients with neuropsychiatric symptoms, consistent with the findings of our study [30]. Another meta-analysis on effects of Ginkgo biloba in dementia showed that the standardized mean differences in change scores for cognition were obtained of ginkgo compared to placebo [31]. However, other studies indicated an opposite conclusion on ginkgo, and it showed that long-term use of Ginkgo biloba extract did not reduce the risk of progression to AD compared with placebo [32]. The different conclusions between different trials are possibly due to the heterogeneity of the study population.

In this study, the change in ADAS-cog scores from baseline was 2.76, 2.43, and −1.25, respectively, in QGST, EGb761, and placebo groups at the end point. Both QGST and EGb761 groups showed significant improvement after 52 weeks' treatment in global cognition and function. Compared with the placebo group, the QGST and EGb761 showed improvement in both ADAS-cog and MMSE scores from 24 weeks, and thereafter continue to improve.

At present, the cognition outcome has been suggested as a suitable and sole primary end point for the accelerated approval of a pharmaceutical treatment for MCI (FDA Draft Guidelines for Early-Stage AD) [33]. In this trial, we used the ADAS-cog and MMSE as the efficacy measurements; however, the cognition tests used may result in unappreciated but artifactual gains because of practice effects, which means that the end point may be influenced by previous testing [34] and the practice effect may lead to false-positive findings.

QGST and EGb761 were safe and well tolerated. The frequencies of AEs in the QGST and EGb761 groups were similar to those of the placebo group. The most frequent AE assessed as probably related to the study medication in the QGST group was constipation. Because the ingredients of QGST contain honey, blood glucose was tested as a safety assessment in our study. The results showed that there was no significant difference in blood glucose after 52 weeks' treatment among the three groups.

There are some limitations in the study that should be noted. First, APOE ε4 carrier increases the risk of aMCI to develop into AD dementia [35], but, in this study, the ApoE ε4 carrier status was not detected in this study and we did not know whether there was a difference in the distribution of ApoE genotyping among the three groups. Second, for a preventive trial, the treatment duration and the sample size were not adequate to draw a conclusion on the longer-term (5 to 10 years) preventive effect or a disease-modifying effect.

In conclusion, QGST and EGb761 may have effect on improvement of global cognition and lower the progression rate of AD in patients with aMCI.

Research in Context.

-

1.

Systematic review: No effective medication was approved to treat mild cognitive impairment (MCI) so far. We reviewed literature studies using CNKI for Chinese articles and PubMed and Google Scholar for English articles. Most studies of herbal formula were short term of less than 6 months. This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of Qinggongshoutao (QGST) pills, a traditional herbal medicine in amnestic subtype of MCI.

-

2.

Interpretation: Our finding showed that in patients with amnestic MCI, QGST showed significant benefits with lower progression rate of Alzheimer's disease and global cognition improvement.

-

3.

Future directions: The observation study of QGST gives us an inspiration for the future herbal therapy for amnestic MCI. Further study will be needed to evaluate the efficacy of QGST on reducing the overall incidence rate of dementia with longer follow-up.

Acknowledgments

The data collection was supported by a grant from the “111” project (No: B08006), National Natural Science Foundation of China, China [grant numbers 81473518 and 81573824], Capital Health Research and Development of Special, China [No: SF2016-4-4193], and Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission Foundation, China [No: Z151100003815021]. Dr. Jinzhou Tian had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Prince M., Bryce R., Albanese E., Wimo A., Ribeiro W., Ferri C.P. The global prevalence of dementia: a systematic review and meta analysis. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan K.Y., Wang W., Wu J.J., Liu L., Theodoratou E., Car J. Epidemiology of Alzheimer's disease and other forms of dementia in China, 1990-2010: a systematic review and analysis. Lancet. 2013;381:2016–2023. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60221-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alzheimer’s Association Changing the trajectory of Alzheimer’s disease: How a treatment by 2025 saves lives and dollars. 23 Jun, 2017. https://www.alz.org/alzheimers_disease_trajectory.asp

- 4.Petersen R.C., Thomas R.G., Grundman M., Bennett D., Doody R., Ferris S. Vitamin E and donepezil for the treatment of mild cognitive impairment. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2379–2388. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petersen R.C., Doody R.S., Kurz A., Mohs R.C., Morris J.C., Rabins P.V. Current concepts in mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:1985–1992. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.12.1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petersen R.C., Morris J.C. Mild cognitive impairment as a clinical entity and treatment target. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:1160–1163. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.7.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petersen R.C., Lopez O., Armstrong M.J., Getchius T.S.D., Ganguli M., Gloss D. Practice guideline update summary: Mild cognitive impairment: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2018;90:126–135. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dodge H.H., Zitzelberger T., Oken B.S., Howieson D., Kaye J. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of Ginkgo biloba for the prevention of cognitive decline. Neurology. 2008;70:1809–1817. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000303814.13509.db. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeKosky S.T., Williamson J.D., Fitzpatrick A.L., Kronmal R.A., Ives D.G., Saxton J.A. Ginkgo biloba for prevention of dementia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2008;300:2253–2262. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen K., Zhou W., Li C., Shi T., Wang W., Wang J.S. Study on the anti-aging function of Qinggongshoutao pills. J Traditional Chin Med. 1985:25–28. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi J., Wei M., Tian J., Snowden J., Zhang X., Ni J. The Chinese version of story recall: a useful screening tool for mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease in the elderly. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:71. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Folstein M.F., Folstein S.E., McHugh P.R. ‘Mini-mental state’. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1974;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hughes C.P., Berg L., Danziger W.L., Coben L.A., Martin R.L. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 1982;140:566–572. doi: 10.1192/bjp.140.6.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galasko D., Bennett D., Sano M., Ernesto C., Thomas R., Grundman M. An Inventory to assess activities of daily living for clinical trials in Alzheimer's disease. The Alzheimer's disease cooperative study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1997;11:S33–S39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McKhann G.M., Knopman D.S., Chertkow H., Hyman B.T., Jazk C.R., Jr., Kawas C.H. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi J., Tian J., Long Z., Liu X., Wei M., Ni J. The pattern element scale: a brief tool of traditional medical subtyping for dementia. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:460562. doi: 10.1155/2013/460562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosen W.G., Mohs R.C., Davis K.L. A new rating scale for Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1984;141:1356–1364. doi: 10.1176/ajp.141.11.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shi J., Ni J., Wei M., Zhang X., Li T., Kang S. Association between pattern changes and cognitive outcome in Alzheimer's disease. J Beijing Univ Tradit Chin Med. 2017:339–343. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joint Consensus Group (JCG) on TCM Diagnosis and Treatment of Alzheimer's Disease Consensus on TCM diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Chin J Integr Tradit West Med. 2018;3:1–7. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doody R.S., Thomas R.G., Farlow M., Iwatsubo T., Vellas B., Joffe S. Phase 3 trials of solanezumab for mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:311–321. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1312889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Strooper B. Lessons from a failed γ-secretase Alzheimer trial. Cell. 2014;159:721–726. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salloway S., Sperling R., Fox N.C., Blennow K., Klunk W., Raskind M. Two phase 3 trials of bapineuzumab in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:322–333. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Honig L.S., Vellas B., Woodward M., Boada M., Bullock R., Borrie M. Trial of solanezumab for mild dementia due to Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:321–330. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1705971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Egan M.F., Kost J., Tariot P.N., Aisen P.S., Cummings J.L., Vellas B. Randomized trial of Verubecestat for mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1691–1703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1706441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jack C.R., Jr., Knopman D.S., Jagust W.J., Petersen R.C., Weiner M.W., Aisen P.S. Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer's disease: an updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:207–216. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70291-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tian J., Shi J., Zhang X., Wang Y. Herbal therapy: a new pathway for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2010;2:30. doi: 10.1186/alzrt54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cho I. Effects of Panax ginseng in neurodegenerative diseases. J Ginseng Res. 2012;36:342–353. doi: 10.5142/jgr.2012.36.4.342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang X., Zhang A., Jiang B., Bao Y., Wang J., An L. Further pharmacological evidence of the neuroprotective effect of catalpol from Rehmannia glutinosa. Phytomedicine. 2008;15:484–490. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou D., Li N., Zhang Y., Yan C., Jiao K., Sun Y. Biotransformation of neuro-inflammation inhibitor kellerin using Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels callus. RSC Adv. 2016;6:97302–97312. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gavrilova S.I., Preuss U.W., Wong J.W., Hoerr R., Kaschel R., Bachinskaya N. Efficacy and safety of Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761 in mild cognitive impairment with neuropsychiatric symptoms: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, multi-center trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;29:1087–1095. doi: 10.1002/gps.4103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weinmann S., Roll S., Schwarzbach C., Vauth C., Willich S.N. Effects of Ginkgo biloba in dementia: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2010;10:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-10-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vellas B., Coley N., Ousset P.J., Berrut G., Dartigues J.F., Dubois B. Long-term use of standardised Ginkgo biloba extract for the prevention of Alzheimer's disease (GuidAge): a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:851–859. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70206-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kozauer N., Katz R. Regulatory innovation and drug development for early-stage Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1169–1171. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1302513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldberg T.E., Harvey P.D., Wesnes K.A., Snyder P.J., Schneider L.S. Practice effects due to serial cognitive assessment: implications for preclinical Alzheimer's disease randomized controlled trials. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2015;1:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bertram L., McQueen M.B., Mullin K., Blacker D., Tanzi R.E. Systematic meta-analyses of Alzheimer disease genetic association studies: the AlzGene database. Nat Genet. 2007;39:17–23. doi: 10.1038/ng1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]