Abstract

Introduction

Prevalence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in Malaysia is 9.07% of the total population, of which 0.36% are at stage 5 CKD or end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Public-private partnership has improved accessibility of renal replacement therapies (RRT), especially dialysis, in Malaysia, but the economic burden of the existing RRT financing mechanism, which is predominantly provided by the public sector, has never been quantified.

Methods

Primary data were collected through a standardized survey, and secondary data analysis was used to derive estimates of the ESRD expenditure.

Results

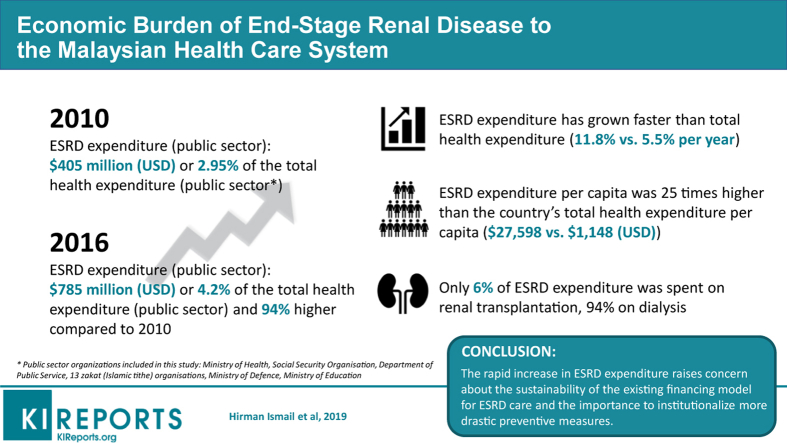

Total annual expenditure of ESRD by the public sector has grown 94% within a span of 7 years, from Malaysian Ringgit [MYR] 572 million (US dollars [USD] 405 million, purchasing power parity [PPP] 2010) in 2010 to MYR 1.12 billion (USD 785 million, PPP 2016) in 2016. The total ESRD expenditure in 2010 constituted 2.95% of the public sector’s total health expenditure, whereas in 2016, the proportion has increased to 4.2%. Only 6% of ESRD expenditure was spent on renal transplantation, and the remaining 94% was spent on dialysis.

Conclusion

The share of ESRD expenditure in total health expenditure for the public sector is considered substantial given only a small proportion of the population is affected by the disease. The rapid increase in expenditure relative to the national total health expenditure should warrant the relevant authorities about sustainability of the existing financing mechanism of ESRD and the importance to institutionalize more drastic preventive measures.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, dialysis, end-stage renal disease, microeconomics, national health expenditure, renal transplantation

Graphical abstract

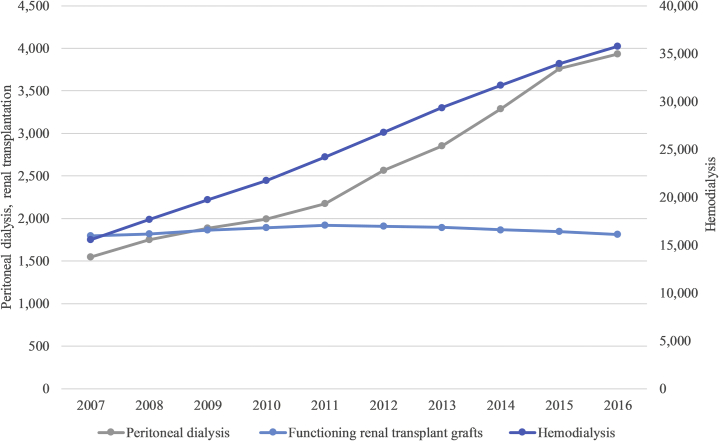

In Malaysia, a population-based study in 2011 reported that 9.1% of Malaysians were found to have CKD.1 The global prevalence of CKD is between 11% and 13%.2 Breakdown of the prevalence by stages were as follows: stage 1, 4.16%; stage 2, 2.0%; stage 3, 2.26%; stage 4, 0.24%; and stage 5, 0.36%. The most common type of RRT in Malaysia is hemodialysis (HD) with the prevalence of 1059 patients per million population (pmp) in 2016 followed by peritoneal dialysis (PD) (127 patients pmp) and renal transplantation (RT) (59 patients pmp).3 In 2016, there were 35,781 patients on HD, 3930 on PD, and 1814 patients with functioning RT grafts.3 Only 1% of the total dialysis patients were at home/office HD. Between 2007 and 2016, the prevalence of HD in Malaysia has increased 2.3 times and PD has increased 2.5 times. However, the prevalence of RT has remained static.

Despite the rapid development of dialysis provision in Malaysia, the actual total economic burden of ESRD by the public sector remains unknown. Most of HD treatment (67.1%) is funded by the public sector,3 which involves not only the Ministry of Health (MOH) but multiple organizations owned by either federal or state governments. Participation of multiple public sector organizations in funding dialysis, especially HD, has made the process of monitoring financial implications of ESRD difficult because the keeping of the expenditure data is not centralized. Economic factors, sometimes referred to as nonmedical factors, influence the choice of the modality of RRT. These factors include financing and reimbursement policy and resource availability.4, 5, 6 Policy related to financing RRT, especially by the public sector, in Malaysia may have played a significant role in influencing the distribution of the different types of RRT and its total economic burden on the country. The aim of this study was to determine the total expenditure of ESRD by the public sector in Malaysia and examine how it has affected the total public sector expenditure on health.

Methodology

The main objective of this analysis was to estimate the total expenditure of ESRD treatment in Malaysia. The total expenditure of ESRD is referred to expenditure to provide RRT services, HD, PD, and RT, and expenditure to provide funds or financial assistance related to RRT. The analysis of cost was conducted from the perspective of the public sector, the main funder of RRT in Malaysia. The cost incurred by the private sector, including out-of-pocket spending and indirect costs such as invalidity or compensation and loss of productivity, was not included in this analysis.

Definition of the public sector was based on the Malaysia National Health Account, which conforms to the System of Health Account adopted by the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development and the World Health Organization. Based on this definition, public sector organizations identified to be financing RRT in Malaysia are the MOH, Department of Public Service, Ministry of Education, Ministry of Defence, Social Security Organisation, and zakat institutions. Zakat or tithe is a form of a mandatory contribution of a part of the Muslims' wealth to be given to the poor or other beneficiaries in Malaysia. There are 14 zakat organizations in Malaysia, all of which are managed by the State Islamic Religious Councils under the State Government that coordinates the collection and distribution of zakat. Some of these organizations function not only as the source of financing, but also as providers for the RRT services. As an example, MOH serves both as the source for financing and as the provider of the services. This is because it does not only manage and distribute public funds to nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) HD centers providing RRT services to eligible patients, but the MOH itself operates HD centers at government hospitals and health clinics. MOH also provides PD services and performs RT at selected hospitals.

Primary and secondary data analyses were conducted to derive estimates of the total ESRD expenditure by the public sector. Standardized format of surveys was distributed to relevant public sector organizations to obtain historical expenditure data (2007–2016) on financial assistance related to RRT. These include reimbursement payments for dialysis; erythropoietin supply; immunosuppressant supply; surgical procedures to create dialysis, such arteriovenous fistulae or PD catheter insertion; and capital grants given to HD centers (including donations of HD machines). The secondary data analysis was done mainly to estimate the expenditure of the selected public sector organizations to provide RRT at their respective facilities. Public sector budgeting systems do not provide explicit tracing on the exact expenditure of a hospital, for example, on HD service. Therefore, an estimate shall be made based on the number of patients and the annual cost of each RRT service at government facilities. A specially tabulated dataset provided by the Malaysia Dialysis and Transplantation Registry was used to obtain the number of RRT patients managed at government facilities, such as the MOH hospitals, university hospitals (Ministry of Education), and Ministry of Defence facilities. The cost of providing HD and PD at public sector facilities was estimated based on the cost analysis by Kumar Surendra et al.,7 and the cost of providing RT was based on the analysis by Bavanandan et al.8 The cost was analyzed from the perspective of MOH hospitals and that includes direct medical costs related to dialysis, medication costs, laboratory costs, inpatient admission costs, and first-year cost of RT inclusive of the cost of surgery and subsequent year cost of maintaining patients with functioning kidney grafts inclusive of the immunosuppressant supply.8, 9 It was assumed that the costs of RRT in MOH centers and non-MOH center were the same. The annual cost of HD, PD, and RT for each patient for 2007 to 2016 was adjusted according to the consumer price index of the corresponding years as published on the World Bank Open Data Web site (https://data.worldbank.org/). All monetary estimates were provided in the local currency units, MYR, and adjusted to the USD based on the World Bank’s PPP index for growth domestic product (GDP). PPP conversion factor is an index of units of a country’s local currency that is required to buy the same amount of goods and services in the US market using USDs. The index can be used to convert local currency unit to the USD, which signifies units of USD needed to buy the same goods and services (in the case of this study, dialysis or renal transplant services) in the United States, based on the country’s purchasing power. All analysis was conducted using Microsoft Excel (2016) (Redmond, WA).

Results

RRTs were funded by multiple public sector organizations at the federal level, state level, and local governments. Contribution by the local government is at the minimal and was not included in this analysis. Eighteen public sector organizations participated in the survey, namely MOH, Ministry of Defence, Ministry of Education, Department of Public Service, Social Security Organisation, and zakat organizations for the state of Kedah, Pulau Pinang, Perak, Selangor, Wilayah Persekutuan (Kuala Lumpur/Putrajaya/Labuan), Negeri Sembilan, Melaka, Johor, Pahang, Terengganu, Kelantan, Sarawak, and Sabah. Only 1 zakat organization for the state of Perlis did not participate in the survey. Perlis is the smallest state in Malaysia and contribution by its zakat organization was expected to be small.

The Malaysian Dialysis and Transplantation Registry provided specially tabulated data on the number of RRT patients managed at the MOH, Ministry of Education, and Ministry of Defence facilities. The Malaysia National Health Account Unit provided updated data on the national health expenditure.

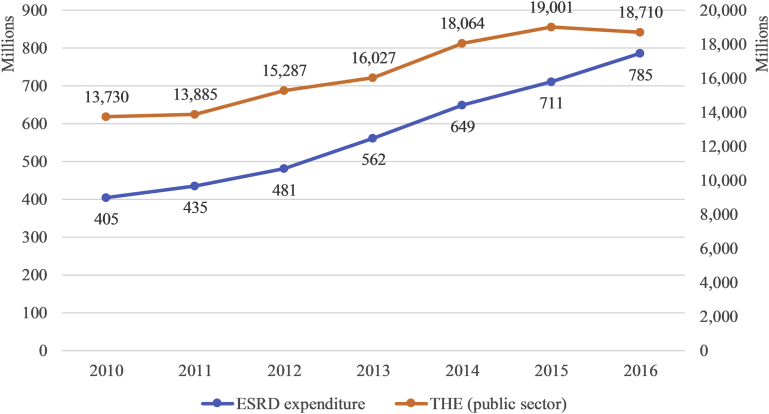

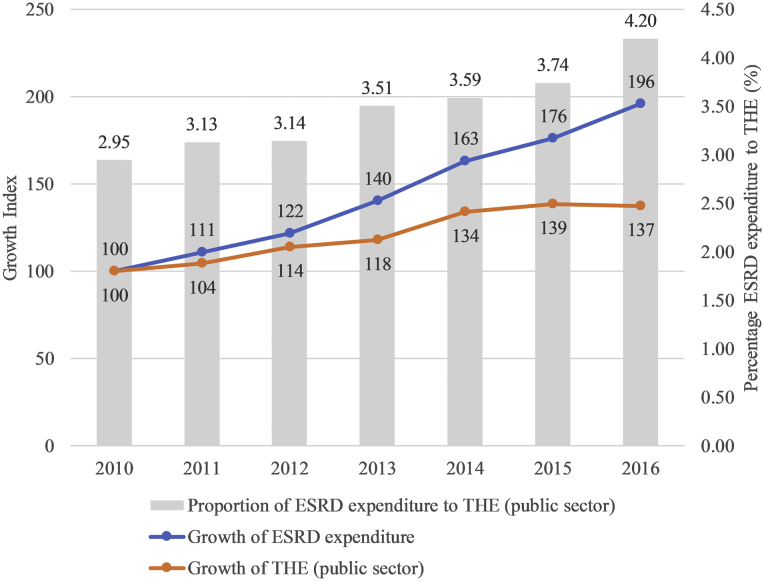

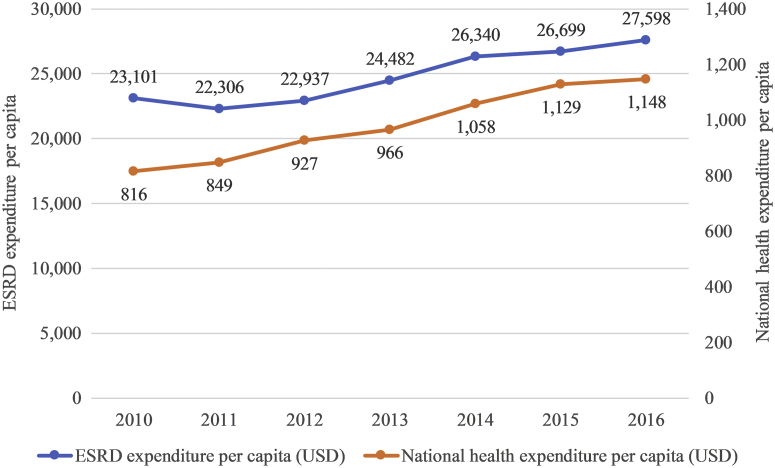

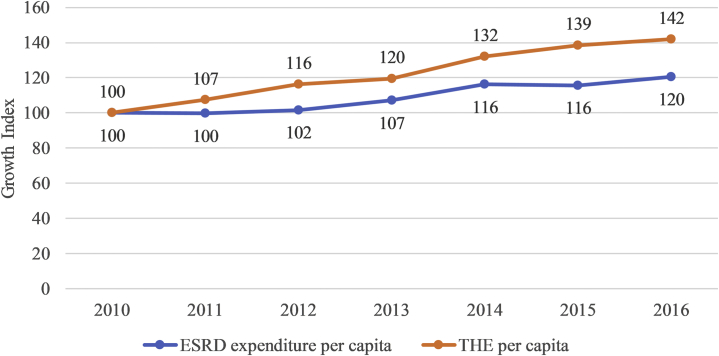

All monetary estimates in this article were provided in the local currency units, MYR and adjusted to the USD based on the World Bank’s PPP index for GDP (published on the World Bank Open Data Web site). The total annual expenditure of ESRD by the public sector in Malaysia has grown by 94% over a period of 7 years; from MYR 572 million (USD 405 million) in 2010 to MYR 1.12 billion (USD 785 million) (Figure 1). Average ESRD expenditure between 2010 and 2016 was MYR 823 million per year (USD 575 million) with an average annual growth of expenditure of 11.89%. Growth index of 100 (2010 as base year) was used to compare the growth of ESRD expenditure with the total health expenditure by the public sector. The total health expenditure by the public sector has grown at slower rates, with lower growth index compared with the total ESRD expenditure (Figure 2). The average annual growth of total health expenditure (public sector) was lower, at 5.54% compared with 11.89% for ESRD expenditure as mentioned earlier. ESRD expenditure constituted between 2.95% and 4.20% of the total health expenditure for the public sector (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

End-stage renal disease (ESRD) expenditure versus total health expenditure (THE) by the public sector in Malaysia (2010–2016; US dollars purchasing power parity).

Figure 2.

Comparison of growth of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) expenditure versus growth of total health expenditure (THE) by the public sector (growth index) and proportion of ESRD expenditure to THE (%) in Malaysia (2010–2016).

The total public sector expenditure on ESRD over a period of 7 years (2010–2016) was MYR 5.76 billion (USD 4.03 billion), of which the MOH shared as the main contributor (55%) followed by Social Security Organisation (16%), Department of Public Service (11%), zakat organizations (11%), Ministry of Defence (5%), and Ministry of Education (2%).

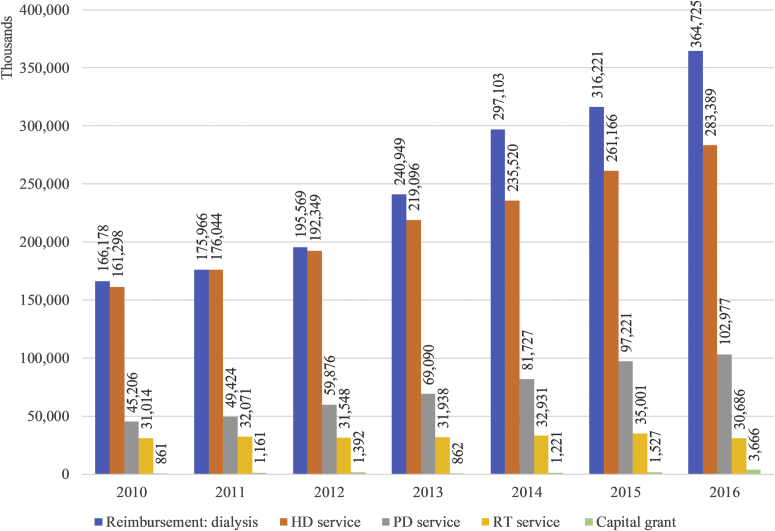

Only 6% of ESRD expenditure was spent on RT, and the remaining 94% was spent on dialysis. Between 2010 and 2016, MYR 2.5 billion (USD 1.8 billion) of public sector funds was spent on reimbursement on dialysis at centers managed by the private sector or NGOs. MYR 2.2 billion (USD 11.5 billion) was spent to provide HD at centers managed by the government (such as HD centers owned by the MOH). The public sector spent MYR 723 million (USD 505 million) to provide PD and MYR 323 million (USD 225 million) to provide RT services at public sector facilities. The public sector also spent MYR 15 million (USD 11 million) to provide a capital grant to other entities, such as NGOs, to develop or upgrade HD centers or to buy new HD machines. Distribution of type of ESRD expenditure by year is provided in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Distribution of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) expenditure by the public sector in Malaysia (2010–2016) by category of expenditure (US dollars purchasing power parity). HD, hemodialysis; PD, peritoneal dialysis; RT, renal transplantation.

ESRD expenditure per capita ranged between MYR 32,545 and MYR 39,327 (USD 22,306 and USD 27,598), although national health expenditure per capita ranged between MYR 1153 and MYR 1636 (USD 816 and USD 1148) (Figure 4). On average, ESRD expenditure per capita was 25 times higher than national health expenditure per capita. Growth index of 100 (2010 as base year) was used to compare the growth rate of ESRD expenditure per capita with national health expenditure per capita, as shown in Figure 5. In contrast to total ESRD expenditure, ESRD expenditure per capita grew at slower rates compared with national health expenditure per capita. This could reflect that the increasing total ESRD expenditure was contributed by the increase in covered population of patients, and the growth of total ESRD expenditure as shown in Figure 3 may not necessary be reflected in expenditure per capita.10 Also, the increasing trend in total ESRD expenditure may not necessarily be contributed by the increase in the cost of the treatment, for example, increased cost of medications, change of clinical practice, change in reimbursement policy, but rather contributed by the overall increase in the prevalence of ESRD.

Figure 4.

End-stage renal disease (ESRD) expenditure per capita versus total health expenditure per capita in Malaysia (2010–2016; US dollars [USD] purchasing power parity).

Figure 5.

Comparison of growth of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) expenditure per capita versus growth of total health expenditure (THE) per capita (growth index) in Malaysia (2010–2016).

It is important to note that this analysis was done from the perspective of the public sector. The public sector in Malaysia shared 67.1% contribution of overall dialysis expenditure in Malaysia.11 It is also estimated from the Malaysia Dialysis and Transplantation Registry data that 93.89% of patients with RT with functioning graft were managed by the public sector. A simple calculation could be done to derive the overall ESRD expenditure for both the public and private sectors by considering the 67.1% share for dialysis and 93.89% share for RT, as mentioned previously. It is estimated that the total ESRD expenditure for both sectors in 2016 was MYR 1.65 billion (USD 1.16 billion), which constituted 3.2% of the total health expenditure for public and private sectors (MYR 51,742 billion or USD 36,619 billion). This estimation is true assuming the cost of ESRD in the private sector in Malaysia is similar to the cost in the public sector. Thus far, all economic evaluations on ESRD were conducted from the perspective of the MOH and none from the perspective of the private sector. Even though the estimation may not be accurate due to uncertainty of the actual cost or expenditure on ESRD by the private sector, it gives a rough estimate to allow comparison with other countries’ expenditure. Many of these expenditure figures were cited as total ESRD expenditure, not itemized into public and private sector expenditures.

Discussion

Malaysia is a country with a population of 32.4 million.12 It has the 38th largest economy in the world and it is categorized as a middle-income country by the World Bank.13 Since 2010, Malaysia’s economy has been on an upward trajectory, with an average growth of 5.4% per year.13 Malaysia’s total health expenditure for 2010 to 2016 was between MYR 33 billion (USD 23.3 billion, PPP 2010) and MYR 51.7 billion (USD 36.6 billion, PPP 2016) per year.14 Total health expenditure in 2016 was 4.21% of the country’s GDP. The public sector contributed between 51% and 58% of the total health expenditure, and the remaining was contributed by the private sector, a fairly equal share between these 2 sectors.14 In general, the public sector provides 82% of inpatient services and 35% of ambulatory care, whereas the private sector provides 18% of inpatient services and 62% of ambulatory care.15

Most of the HD patients in Malaysia (76.84%) undergo HD sessions at centers run by the private sectors: 53.74% owned by private entities and 23.10% owned by NGOs.11 The remaining HD patients undergo HD sessions at centers run by the public sector: 22.55% by the MOH, 0.46% by university hospitals, and 0.15% by the Ministry of Defence centers.11 PD services are mainly provided by the public sector and only 0.92% of all PD patients are managed by the private sector. There are 3 public hospitals providing RT services: 2 MOH hospitals and 1 university hospital, and, currently, only 1 private hospital is licensed to provide RT services. Most patients with functioning renal grafts are managed by the public hospitals, including those who had undergone transplantation from unknown sources in foreign countries. However, in contrast to the distribution of provider of services, the public sector contributed the biggest share in funding RRT services in the country: 67.1% for dialysis and 93.89% for RT. A financing mechanism that allows public sector organizations to provide financial assistance to eligible patients undergoing dialysis at private centers has encouraged the expansion of private HD centers and, in turn, has helped to ease the burden of centers managed by the public sector. Lim et al.16 described the role of the government in spearheading the public-private partnership for dialysis treatment and the reform of financing mechanism of RRT that took place in early 2000. The reform has increased private sector participation in dialysis provision and has increased access to treatments, especially to patients in the lower income group.16 The government has been providing capital injections to encourage the expansion of RRT through the national budget. Financial allocation related to dialysis was announced by the Finance Minister in 6 consecutive annual national budgets (2013–2018),17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 signifying the importance of dialysis in setting up the national agenda, especially in people’s well-being and health sector. Although recognizing the importance of the role of the government and the public-private partnership in improving access to RRT, especially dialysis, it is important for the government to examine the sustainability of the current financing mechanism by understanding the economic burden of ESRD as a result of the continuous capital injections. The finding of this study would be relevant especially to the developing countries in understanding the potential effect of such a model of financing on the national expenditure on health.

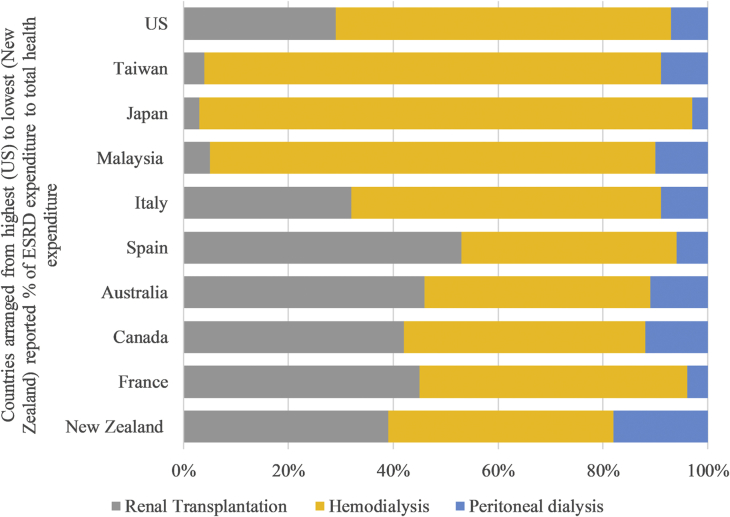

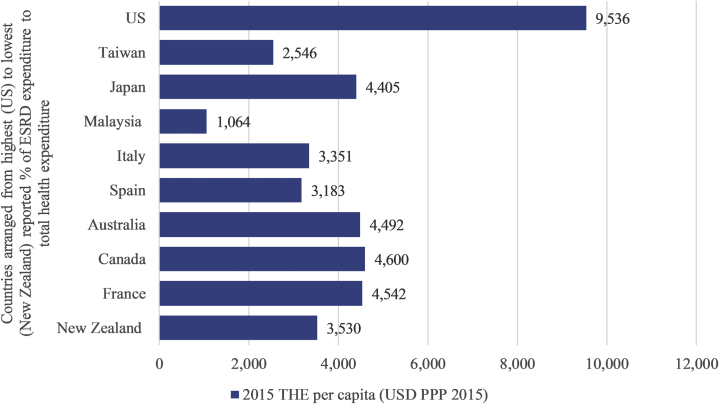

Even though only 0.36% of the total Malaysian population was affected by stage 5 CKD,1 the annual ESRD expenditure constituted between 2.95% and 4.20% of total health expenditure by the public sector. In 2016 alone, ESRD expenditure has inflated to MYR 1.12 billion (USD 785 million, PPP 2016). In a crude estimation as described in the earlier section, total ESRD expenditure for both public and private sectors in 2016 was MYR 1.65 billion (USD 1.16 billion, PPP 2016), which was 3.2% of national total health expenditure (public and private sectors). Is ESRD expenditure in Malaysia considered high? Medicare spent 7.1% of its total expenditure on ESRD, which represented three-quarters of overall ESRD expenditure in the United States.23 Seven percent of Taiwan’s national health insurance budget was spent on ESRD,24, 25 and Japan spent 3.8% of its medical spending on ESRD.26 Taiwan, Japan, and the United States were the 3 countries with the highest prevalence of ESRD (3317pmp, 2529 pmp, and 2138 pmp, respectively27), which could then explain the high ESRD expenditure. Even though Malaysia stood only at number 12 in US Renal Data System international comparison, with prevalence on ESRD of 1295 cases pmp, the proportion of ESRD expenditure to total health expenditure has reached 3.49%, which was near to Japan. Canada, on the other hand, with ESRD prevalence of 1314 pmp,28 almost similar to Malaysia, reported lower ESRD expenditure at 1.3% of its total health expenditure.29 Canada spent 11.1% of its GDP on health in 2016, with higher per capita spending at Canada dollar 6299 (USD 5031, PPP 2016)30 compared with Malaysia: 4.21% total health expenditure to GDP in 2016, with per capita spending of MYR 1636 (USD 1148, PPP 2016). The larger spending on health could explain why Canada had a lower proportion of ESRD expenditure to total health expenditure even though Canada’s prevalence of ESRD was almost similar to Malaysia. For other comparisons, Italy spent 1.8% of its total health expenditure on ESRD,31 followed by Spain (1.5%),32 Australia (1.4%),33 France (1.3%),34 and New Zealand (0.9%).35 It is observed that countries with lower proportion of ESRD expenditure to total health expenditure used more RT as RRT modality compared with dialysis (Figure 636) and had higher per capita spending on health (Figure 737), except the United States.

Figure 6.

Distribution of renal replacement modalities, by country (2015). Source: United States Renal Data System. Chapter 11: International Comparisons. Available at: https://www.usrds.org/2017/view/v2_11.aspx. Accessed July 23, 2018.36

Figure 7.

Total health expenditure (THE) per capita by country (2015; US dollars purchasing power parity [USD PPP] 2015). Source: The World Bank. Current health expenditure (% of GDP). Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.CHEX.GD.ZS. Accessed July 15, 2018.37 ESRD, end-stage renal disease.

The ESRD expenditure has grown at faster rates compared with the total health expenditure for the public sector. The inflated ESRD expenditure was largely contributed by the rapid increase in the prevalence of dialysis patients. In 2016, PD and HD have grown 2.5 and 2.3 times, respectively, when compared with 2010, whereas RT has remained static (Figure 811).

Figure 8.

Prevalence of renal replacement therapy in Malaysia (2007–2016). Source: Malaysian Society of Nephrology. 24th Report of the Malaysian Dialysis and Transplant Registry 2016. Available at: https://www.msn.org.my/nrr/mdtr2016.jsp. Accessed July 24, 2019.11

Such a trend shall raise concerns about the opportunity cost of RRT as a result of possible displacement of other health activities or interventions, especially in a fixed budget system in the public sector. ESRD expenditure per capita exceeding 25 times more than the total health expenditure per capita (Figure 4) indicates a high volume of health resources are currently being used to provide care for patients with ESRD, who constitute a relatively small proportion of the total Malaysian population. Comparison of the ESRD expenditure with Canada, as mentioned previously, shall reiterate the possibility of displacement of other health activities or medical services, especially when the health resources are comparatively more constrained than other countries. Policy and strategy reviews are needed to further optimize the use of health resources and maximize the health benefits of the public sector’s investments in health. This could be achieved partly by giving emphasis on more cost-effective measures, such as screening of CKD and utilization of RT or PD. There is evidence to show that screening of CKD through estimated glomerular filtration rate and/or microalbuminuria in a high-risk population, like patients with diabetes and hypertension, has proven to be cost-effective.38 Increasing RT rates would increase the cumulative saving in ESRD expenditure and is also associated with better clinical outcome.39, 40 As discussed earlier, Malaysia spends only 6% of its ESRD expenditure on RT, which is lower when compared with Canada (31.4%),29 Australia (20.2%),41 and the United States (9.7%).23 Even though in Malaysia PD is marginally more cost-effective than HD,9 there is other evidence that PD is more cost-effective and associated with better clinical outcome.39, 42, 43, 44 Increasing utilization of PD may result in considerable savings of health care spending.39, 45 The higher growth of prevalence of PD compared with HD in Malaysia is a positive development and shall be further supported. Participation by the private sector, including NGOs, could be encouraged to expand its capacity to provide PD service, which is currently concentrated only in the public sector. Introduction of a “bundle system” or prospective payment system, like in the United States,46 could be explored to provide financial incentive to promote utilization of PD over HD, especially at centers run by the private sector. In 2014, the government announced a special allocation to promote continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis in the national budget speech,19 and could be an impetus for more initiatives by the government to encourage PD utilization.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus is the most common cause of ESRD in Malaysia.11 Controlling diabetes and preventing its complications may not only reduce the incidence of ESRD, but also its other complications. Recent advances in diabetes care, including in acute clinical management and health promotion, have led to reduction in complications of diabetes including progression to ESRD.47 A major policy review and holistic approach to the management of CKD, especially diabetic kidney disease, is imperative if we aim to reduce the cost of managing ESRD. Known strategies and resources that are shown to reduce progression to ESRD, including the more recent advancements such as newer classes of antihyperglycemic agents, including sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors and the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor,48 should be made available in primary care where most patients with diabetes are seen in Malaysia.

There are several limitations of this research. Public sector organizations include entities under the jurisdiction of the federal government, state governments, and local authorities. This study took account of only the main contributors of funds and service providers, and has excluded the local authorities because of the lack of resources for data collection. There are 149 local authorities nationwide and only a few provided direct financial assistance to their employees. The total contribution is expected to be small. The public sector accounting system does not explicitly provide details of expenditure based on the type of disease or treatment. Therefore, the expenditure to provide RRT was estimated based on the available works in the literature and database on the cost of treatment. However, the cost dialysis and RT was taken from recent articles published in 2018 and 2015, respectively.7, 8 The international comparison as discussed previously was made based on reported figures available in the literature and published reports. In some of these sources, methodology of estimation of ESRD expenditure was not elaborated and therefore it was difficult to make a fair and standardized comparison.

In conclusion, Malaysia’s ESRD expenditure is comparatively high compared with other countries, and has grown faster than the national health expenditure. A large volume of health resources that are currently being spent on each patient with ESRD shall raise concern about the opportunity cost of RRT, especially dialysis, that could otherwise be spent on more cost-effective measures to attain better health outcomes. Focused initiatives to promote primary and secondary prevention of CKD, utilization of PD, and development of RT and an organ donation program shall be further explored to be implemented as part of long-term cost-containment strategies. The centralization of resources of the different public sector agencies and standardization of policy, procedures, and charges relating to the financing mechanism of RRT could be considered to promote more efficient use of public resources.

Disclosure

All the authors declared no competing interests.

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: unconditional research grant awarded by the Malaysian Society of Nephrology and the National Kidney Foundation. Both are not-for-profit nongovernmental organizations. This research was approved by the Research Committee UKM (UKM PPI/111/8/JEP-2017-558) and Medical Research Committee, Faculty of Medicine UKM (UKM FPR.4/224/FF-2017-354). This research was registered in the National Medical Research Registry, Ministry of Health Malaysia (NMRR-17-1527-37186), and also was approved by the Ministry of Health’s Medical Research and Ethics Committee (KKM.NIHSEC.P17-1942[5]).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Director General of Health Malaysia for the permission to publish this article. The authors also thank funders of their research, the National Kidney Foundation (grant 1001/ADAM/780) and the Malaysian Society of Nephrology (grant MSN2018), for their continuous support. This study is part of ongoing PhD research to understand the microeconomic consequences of CKD stage 5 to the public sector in Malaysia, currently undertaken by the Department of Community Health, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. The authors especially thank those who have cooperated in providing relevant input and data, namely the Ministry of Health Malaysia, Department of Public Service, Ministry of Defence, Social Security Organisation (SOCSO), and various zakat organizations. The authors especially acknowledge the Malaysian Dialysis and Transplantation Registry and the Malaysia National Health Account Unit, Ministry of Health, for providing the relevant data needed for this study. The authors acknowledge Dr. Ong Loke Meng, the Head of Nephrology Services, Ministry of Health Malaysia, for reviewing this article.

References

- 1.Hooi L.S., Ong L.M., Ahmad G. A population-based study measuring the prevalence of chronic kidney disease among adults in West Malaysia. Kidney Int. 2013;84:1034–1040. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hill N.R., Fatoba S.T., Oke J.L. Global prevalence of chronic kidney disease – a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MSN. Malaysia Dialysis and Transplant Registry Annual Report 2014. Vol 22. Kuala Lumpur: Malaysian Society of Nephrology; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Just P.M., de Charro F.T., Tschosik E.A. Reimbursement and economic factors influencing dialysis modality choice around the world. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:2365–2373. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nissenson A.R., Prichard S.S., Cheng I.K. Non-medical factors that impact on ESRD modality selection. Kidney Int Suppl. 1993;40:S120–S127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wauters J.-P., Uehlinger D. Non-medical factors influencing peritoneal dialysis utilization: the Swiss experience. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:1363–1367. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar Surendra N., Rizal Abdul Manaf M., Lai Seong H. The cost of dialysis in Malaysia: haemodialysis and continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Malaysian Journal of Public Health Medicine. 2018;18:70–81. https://www.mjphm.org.my/mjphm/journals/2018 - Volume 18 (2)/THE COST OF DIALYSIS IN MALAYSIA HAEMODIALYSIS AND CONTINUOUS AMBULATORY PERITONEAL DIALYSIS.pdf Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bavanandan S., Yap Y.-C., Ahmad G. The cost and utility of renal transplantation in Malaysia. Transplant Direct. 2015;1:e45. doi: 10.1097/TXD.0000000000000553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hooi L.S., Lim T.O., Goh A. Economic evaluation of centre haemodialysis and continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis in Ministry of Health hospitals, Malaysia. Nephrology (Carlton) 2005;10:25–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2005.00360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boccuti C., Moon M. Comparing Medicare and private insurers: growth rates in spending over three decades. Health Aff (Millwood) 2003;22:230–237. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.2.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malaysian Society of Nephrology 24th Report of the Malaysian Dialysis and Transplant Registry 2016. https://www.msn.org.my/nrr/mdtr2016.jsp Available at:

- 12.Department of Statistics Malaysia Official Portal . Department of Statistics Malaysia; 2018. Population and Demography.https://www.dosm.gov.my/v1/index.php?r=column/ctwoByCat&parent_id=115&menu_id=L0pheU43NWJwRWVSZklWdzQ4TlhUUT09 Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Bank Malaysia Overview. 2018. http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/malaysia/overview Available at:

- 14.Ministry of Health Malaysia; Putrajaya: 2014. Malaysia National Health Accounts Health Expenditure Report 1997–2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15.WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific . World Health Organization, Regional Office for the Western Pacific; Manila: 2012. Malaysia Health System Review.http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/206911 Available at: Accessed September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lim T.-O., Goh A., Lim Y.-N., Mohamad Zaher Z.M., Suleiman A.B. How public and private reforms dramatically improved access to dialysis therapy in Malaysia. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:2214–2222. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Government of Malaysia . Putrajaya: Government of Malaysia; 2016. 2017 Budget Speech by Prime Minister of Malaysia - Introducing Supply Bill (2017)https://www.treasury.gov.my/pdf/budget/speech/bs17.pdf Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 18.Government of Malaysia 2013 Budget Speech by Prime Minister of Malaysia - Introducing Supply Bill (2013). Government of Malaysia; 2012. https://www.pmo.gov.my/dokumenattached/bajet2013/SPEECH_BUDGET_2013_28092012_E.pdf Available at: Accessed October 2018.

- 19.Government of Malaysia 2014 Budget Speech by Prime Minister of Malaysia - Introducing Supply Bill (2014). Putrajaya: Government of Malaysia; 2013. http://www.treasury.gov.my/pdf/budget/speech/bs14.pdf Available at: Accessed October 2018.

- 20.Government of Malaysia 2015 Budget Speech by Prime Minister of Malaysia - Introducing Supply Bill (2015). Putrajaya: Government of Malaysia; 2014. http://www.bnm.gov.my/files/2014/budget2015_en.pdf Available at: Accessed October 2018.

- 21.Government of Malaysia 2016 Budget Speech by Prime Minister of Malaysia - Introducing Supply Bill (2016). Putrajaya: Government of Malaysia; 2015. http://www.bnm.gov.my/files/Budget_Speech_2016.pdf Available at: Accessed October 2018.

- 22.Government of Malaysia 2018 Budget Speech by Prime Minister of Malaysia - Introducing Supply Bill (2018). Putrajaya: Government of Malaysia; 2017. http://www.treasury.gov.my/pdf/budget/speech/bs18.pdf Available at: Accessed October 2018.

- 23.US Renal Data System Chapter 9. Healthcare Expenditures for Persons with ESRD. 2017. https://www.usrds.org/2017/view/v2_09.aspx Available at:

- 24.Kao T.-W., Chang Y.-Y., Chen P.-C. Lifetime costs for peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis in patients in Taiwan. Perit Dial Int. 2013;33:671–678. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2012.00081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bureau of National Health Insurance National Health Insurance Annual Statistical Report. Taiwan; 2002. https://www.nhi.gov.tw/english/Content_List.aspx?n=9899572B6F2E63A0&topn=616B97F8DF2C3614 Available at: Accessed September 2018.

- 26.Nawata K., Kimura M. Evaluation of medical costs of kidney diseases and risk factors in Japan. Health. 2017;9:1734–1749. [Google Scholar]

- 27.US Renal Data System Chapter 12. International comparisons. 2017. https://www.usrds.org/2012/view/v2_12.aspx Available at:

- 28.US Renal Data System Chapter 11: International comparisons. 2017. https://www.usrds.org/2017/view/v2_11.aspx Available at:

- 29.Zelmer J.L. The economic burden of end-stage renal disease in Canada. Kidney Int. 2007;72:1122–1129. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Canadian Institute for Health Information National Health Expenditure Trends, 1975 to 2016. Ottawa, Canada; 2016. https://www.cihi.ca/en/health-spending/2018/national-health-expenditure-trends Available at:

- 31.Pontoriero G., Pozzoni P., Del Vecchio L., Locatelli F. International Study of Health Care Organization and Financing for renal replacement therapy in Italy: an evolving reality. Int J Health Care Finance Econ. 2007;7:201–215. doi: 10.1007/s10754-007-9016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luno J. The organization and financing of end-stage renal disease in Spain. Int J Health Care Finance Econ. 2007;7:253–267. doi: 10.1007/s10754-007-9021-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare Projections of the prevalence of treated end-stage kidney disease in Australia 2012–2020. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-kidney-disease/projections-of-the-prevalence-2012-2020/contents/table-of-contents Available at:

- 34.Durand-Zaleski I., Combe C., Lang P. International Study of Health Care Organization and Financing for end-stage renal disease in France. Int J Health Care Finance Econ. 2007;7:171–183. doi: 10.1007/s10754-007-9025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ashton T., Marshall M.R. The organization and financing of dialysis and kidney transplantation services in New Zealand. Int J Health Care Finance Econ. 2007;7:233–252. doi: 10.1007/s10754-007-9023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.United States Renal Data System Chapter 11: International Comparisons. https://www.usrds.org/2017/view/v2_11.aspx Available at:

- 37.The World Bank. Current health expenditure (% of GDP) https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.CHEX.GD.ZS Available at:

- 38.Komenda P., Ferguson T.W., Macdonald K. Cost-effectiveness of primary screening for CKD: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63:789–797. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Howard K., Salkeld G., White S. The cost-effectiveness of increasing kidney transplantation and home-based dialysis. Nephrology. 2009;14:123–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2008.01073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cass Chadban S.J., Gallagher M.P., Howard K. Kidney Health Australia; Melbourne, Australia: 2010. The Economic Impact of End-Stage Kidney Disease in Australia: Projections to 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; Canberra, Australia: 2009. Health Care Expenditure on Chronic Kidney Disease in Australia.https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/health-welfare-expenditure/health-care-expenditure-on-chronic-kidney-disease/formats Available at: Accessed October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chang Y.-T., Hwang J.-S., Hung S.-Y. Cost-effectiveness of hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis: a national cohort study with 14 years follow-up and matched for comorbidities and propensity score. Sci Rep. 2016;6:30266. doi: 10.1038/srep30266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang F., Lau T., Luo N. Cost-effectiveness of haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis for patients with end-stage renal disease in Singapore. Nephrology. 2016;21:669–677. doi: 10.1111/nep.12668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haller M., Gutjahr G., Kramar R. Cost-effectiveness analysis of renal replacement therapy in Austria. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:2988–2995. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Treharne C., Liu F.X., Arici M. Peritoneal dialysis and in-centre haemodialysis: a cost-utility analysis from a UK payer perspective. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2014;12:409–420. doi: 10.1007/s40258-014-0108-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hirth R.A. The organization and financing of kidney dialysis and transplant care in the United States of America. Int J Health Care Finance Econ. 2007;7:301–318. doi: 10.1007/s10754-007-9019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gregg E.W., Li Y., Wang J. Changes in diabetes-related complications in the United States, 1990–2010. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1514–1523. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1310799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cherney D.Z.I., Bakris G.L. Novel therapies for diabetic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2018;8:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.kisu.2017.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]