Abstract

Pneumorrhachis refers to the clinical presentation of air within the spinal canal, and it is rarely associated with pneumomediastinum, particularly in young children. Pneumorrhachis associated with pneumomediastinum is generally asymptomatic. Here we report 2 unusual cases involving very young children with pneumorrhachis secondary to pneumomediastinum and present a review of the relevant literature. Case 1 involved a 4-year-old girl who presented with wheezing, violent coughing, and dyspnea associated with bronchiolitis. Case 2 involved a 3-year-old boy who presented with wheezing, violent coughing, and dyspnea associated with interstitial pneumonia possibly caused by graft-versus-host disease with human herpesvirus 6 infection after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. In both cases, pneumorrhachis improved with oxygen inhalation therapy and treatment of the underlying disease. Pneumorrhachis is rarely associated with neurological problems; however, decompressive laminectomy may be indicated to relieve the air block. Because pneumorrhachis is rare in children and neurological sequelae may be difficult to identify, close clinical, and radiographic observations are necessary. Plain radiography is not sufficient, and computed tomography should be performed to rule out intraspinal air.

Keywords: Pneumorrhachis, Pneumomediastinum, Children

Introduction

Pneumorrhachis is characterized by the presence of air in the epidural space. It is most commonly associated with iatrogenic or traumatic etiologies, including epidural anesthesia, lumbar puncture, spinal surgery, spinal injury, and traumatic pneumothorax [1]. Although pneumorrhachis is rarely associated with pneumomediastinum complicated by bronchial asthma and violent cough [2], [3], Tsuji et al. first reported cases of pneumorrhachis associated with asthma and/or violent coughing [4]. In such cases, the peripheral pulmonary alveoli may rupture because of a sudden increase in the intraalveolar pressure. Subsequently, the air present in the pulmonary perivascular interstitium may migrate along the fascial planes and move from the posterior mediastinum or retropharyngeal space to the epidural space through the neural foramina. There are no fascial barriers to block connections between the posterior mediastinum or retropharyngeal space and the epidural space [4], [5], [6].

There are few reports of young children with pneumorrhachis secondary to pneumomediastinum. Here we describe 2 unusual cases involving very young children and present a review of the relevant literature.

Case Presentation

Case 1

A 4-year-old girl presented with wheezing, violent coughing, and dyspnea since 3 days. She had initially consulted the community hospital for her symptoms. She had a history of viral-induced wheezing, which was treated with bronchodilators, montelukast sodium, and dexamethasone. However, her symptoms did not improve, and physical examination indicated subcutaneous emphysema in the chest and neck. Chest radiography showed subcutaneous emphysema and pneumomediastinum (Fig. 1), while computed tomography (CT) further indicated pneumorrhachis (Fig. 2). She was transferred to our institute and admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit. Her respiratory rate was 40/min, while the oxygen saturation (SO2) was 100% in pulse oximetry with oxygen delivery at 4 L/min through a mask. Physical examination revealed subcutaneous emphysema in the chest and neck with retractive breathing. Auscultation revealed decreased inspiratory sounds and bilateral wheezing. Her general and neurological conditions were normal. Arterial blood gas analysis revealed the following: pH, 7.355; partial pressure of carbon dioxide, 30.5 mmHg; partial pressure of oxygen, 148 mmHg; SO2, 98.6%; and bicarbonate (HCO3−), 17 mEq/L. A blood test revealed a white blood cell count of 14600/µL (neutrophils: 91%) and C-reactive protein level of 4.3 mg/dL. Other biochemical parameters showed no abnormalities. She was treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics, inhalation bronchodilators, systemic corticosteroids, and oxygen inhalation therapy. We also performed polymerase chain reaction for a throat swab specimen, whole blood, and serum. The throat swab specimen was positive for adenovirus (Ct value: 37.371). Her condition improved and she was shifted from pediatric intensive care unit on the second day of admission. A respiratory function test was not performed because of her age. She was discharged from the hospital on day 10 of hospitalization and prescribed inhaled corticosteroid treatment because of the history of recurrent bronchiolitis.

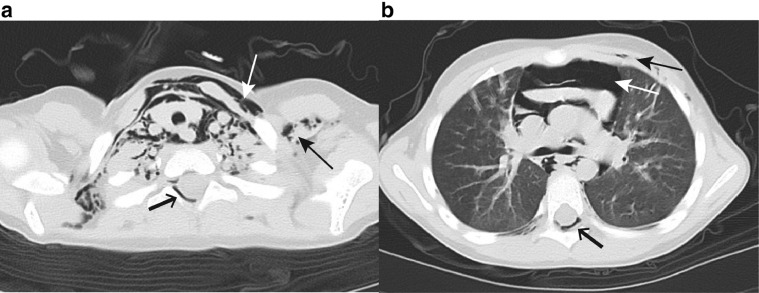

Fig. 1.

Chest radiography findings at admission of a 4-year-old girl with pneumorrhachis. Subcutaneous emphysema (black arrows) and pneumomediastinum (white arrow) can be observed.

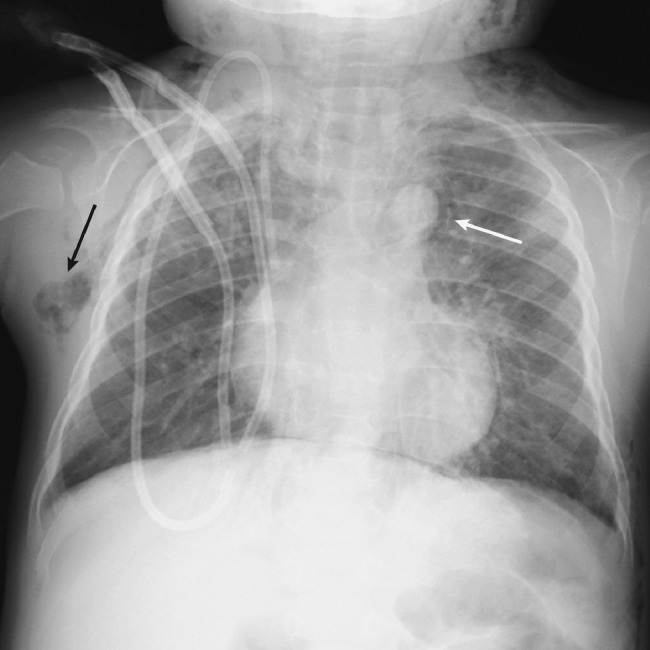

Fig. 2.

Computed tomography findings at admission of a 4-year-old girl with pneumorrhachis.

(A) Axial reconstruction of the cervical spine shows subcutaneous emphysema (black arrow), pneumomediastinum (white arrow), and epidural emphysema (short arrow).

(B) Subcutaneous emphysema (black arrow), pneumomediastinum (white arrow), and epidural emphysema (short arrow) can be observed at the level of the tracheal bifurcation.

Case 2

A 3-year-old boy with refractory juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia received chemotherapy and 2 rounds of allogeneic stem cell transplantation. However, his condition relapsed, and he received HLA-haploidentical bone marrow transplantation. At 3 months after the final transplant procedure, he presented with tachypnea, violent coughing, and wheezing. Chest radiography revealed bilateral ground-glass opacities, subcutaneous emphysema, and pneumomediastinum (Fig. 3). These findings were confirmed on chest CT, which also demonstrated cervical epidural air (Fig. 4). There were no neurological abnormalities. A blood test revealed a white blood cell count of 8800/µL (neutrophils: 60%) and C-reactive protein level of 0.15 mg/dL. Aspartate aminotransferase (normal range: 24–43 IU/L) and alanine aminotransferase (9–30 IU/L) levels were 45 and 63 IU/L, respectively. The serum level of KL-6, a marker for interstitial pneumonia, was elevated to 1470 U/mL (normal: <500 U/mL). Candida and Aspergillus antigens were absent. Polymerase chain reaction for a throat swab specimen, whole blood, and serum revealed human herpesvirus 6 (HHV6) infection (1.2 × 107 copies/mL, 2.6 × 109 copies/mL, and 4.0 × 106 copies/mL, respectively). The patient was diagnosed with interstitial pneumonia possibly caused by graft-versus-host-disease with HHV6 reactivation. He received prednisolone, antiherpesvirus agents, and oxygen inhalation therapy, and the subcutaneous emphysema resolved in 7 days.

Fig. 3.

Chest radiography findings at admission of a 3-year-old boy with pneumorrhachis. Bilateral ground-glass opacities, subcutaneous emphysema (long arrow), and pneumomediastinum (white arrow) can be observed.

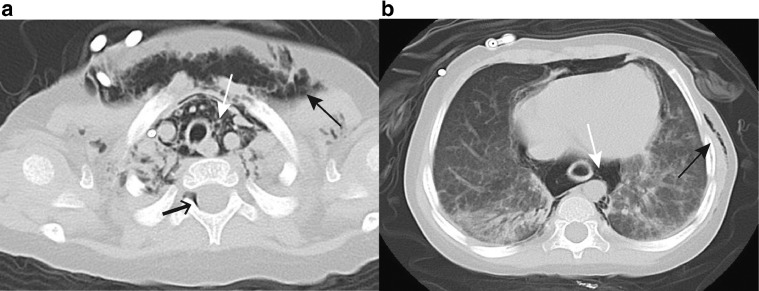

Fig. 4.

Computed tomography findings at admission of a 3-year-old boy with pneumorrhachis.

(A) Axial reconstruction of the cervical spine shows subcutaneous emphysema (black arrow), pneumomediastinum (white arrow), and epidural emphysema (short arrow).

(B) Bilateral ground-glass opacities, predominantly dorsolateral lobes, subcutaneous emphysema (black arrow), and pneumomediastinum (white arrow) can be observed at the T10 level.

Discussion

We presented 2 important cases of pneumorrhachis associated with pneumomediastinum in very young patients. The findings are clinically significant because most previous reports involved young adults. We reviewed the relevant literature regarding cases involving children aged <15 years and retrieved 25 articles reporting 32 cases [3], [4], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29]. In total, 22 boys and 10 girls aged between 1 and 15 years (mean age: 9 years) were identified. Pneumorrhachis occurred concomitantly with pneumomediastinum in all cases. Underlying conditions included bronchial asthma (n = 15); lower respiratory tract infection or bronchiolitis (n = 3); foreign body aspiration, graft-versus-host disease, and upper respiratory tract infection (n = 2); and anorexia nervosa and vomiting (n = 1). Two patients developed neurological symptoms that did not require surgical intervention.

Chaichana et al. described neurological complications in patients with pneumorrhachis associated with both trauma and pneumomediastinum [2]. In addition, Song reported a case of pneumorrhachis secondary to pneumomediastinum that presented with progressive motor weakness and sensory deficits in the lower extremities. These neurological symptoms resolved after C7 laminectomy [30]. Our patients did not present with any neurological abnormalities, and their condition resolved after treatment for the underlying disease and high flow oxygen therapy.

In summary, pneumorrhachis presents with subtle clinical findings and is difficult to diagnose on chest radiographs. Noncontrast-enhanced CT is additionally required for further neurological evaluations and treatment planning. Once abnormal neurological findings are recognized or ruled out, further CT studies are necessary for confirming the etiology [1]. Pneumomediastinum is also difficult to identify in young children, necessitating close clinical examinations and noncontrast-enhanced CT for neurological evaluations.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

Informed Consent: The parents/guardians of the 2 patients provided informed consent for publication of this report.

References

- 1.Oertel M.F., Korinth M.C., Reinges M.H., Krings T., Terbeck S., Gilsbach J.M. Pathogenesis, diagnosis and management of pneumorrhachis. Eur Spine J. 2006;15(suppl 5):636–643. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-0160-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chaichana K.L., Pradilla G., Witham T.F., Gokaslan Z.L., Bydon A. The clinical significance of pneumorachis: a case report and review of the literature. J Trauma. 2010;68:736–744. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181c46dd3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belotti E.A., Rizzi M., Rodoni-Cassis P., Ragazzi M., Zanolari-Caledrerari M., Bianchetti M.G. Air within the spinal canal in spontaneous pneumomediastinum. Chest. 2010;137:1197–1200. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsuji H., Takazakura E., Terada Y., Makino H., Yasuda A., Oiko Y. CT demonstration of spinal epidural emphysema complicating bronchial asthma and violent coughing. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1989;13:38–39. doi: 10.1097/00004728-198901000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooley J.C., Gillespie J.B. Mediastinal emphysema: pathogenesis and management. Rep Case Dis Chest. 1966;49:104–108. doi: 10.1378/chest.49.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Macklin C.C. Transport of air along sheaths of pulmonic blood vessels from alveoli to mediastinum. Arch Intern Med. 1939;64:913. [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Meulder A., Michaux L. Aerorachia. Intensive Care Med. 1990;16:275–276. doi: 10.1007/BF01705167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pifferi M., Marrazzini G., Baldini G., Caramella D., Bulleri A., Bartolozzi C. Epidural emphysema in children with asthma. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1997;24:125–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caramella D., Bulleri A., Battolla L., Pifferi M., Baldini G., Bartolozzi C. Spontaneous epidural emphysema and pneumomediastinum during an asthmatic attack in a child. Pediatr Radiol. 1997;27:929–931. doi: 10.1007/s002470050274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hatzitolios A.I., Sion M.L., Kounanis A.D., Toulis E.N., Dimitriadis A., Ioannidis I., Ziakas G.N. Diffuse soft tissue emphysema as a complication of anorexia nervosa. Postgrad Med J. 1997;73:662–664. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.73.864.662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dosios T., Fytas A., Zarifis G. Spontaneous epidural emphysema and pneumomediastinum. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2000;18:123. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(00)00454-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tambe P., Kasat L.S., Tambe A.P. Epidural emphysema associated with subcutaneous emphysema following foreign body in the airway. Pediatr Surg Int. 2005;21:721–722. doi: 10.1007/s00383-005-1445-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakai M., Murayama S., Gibo M. Frequent cause of the Macklin effect in spontaneous pneumomediastinum: demonstration by multidetector-row computed tomography. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2006;30:92–94. doi: 10.1097/01.rct.0000187416.07698.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kono T., Kuwashima S., Fujioka M., Kobayashi C., Koike K., Tsuchida M., Seki I. Epidural air associated with spontaneous pneumomediastinum in children: uncommon complication? Pediatr Int. 2007;49:923–927. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2007.02480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dontu V.S., Kramer D. Spontaneous pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, and epidural emphysema presenting as neck pain suspicious for meningitis. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2007;23:469–471. doi: 10.1097/01.pec.0000280512.21160.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harrod C.C., Boykin R.E., Kim Y.J. Epidural pneumatosis of the cervicothoracic spine associated with transient upper motor neuron findings complicating Haemophilus influenzae pharyngitis, bronchitis, and mediastinitis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2010;30:455–459. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e3181df44b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karaoglan A., Cal M.A., Orki A., Arpaozu B.M., Colak A. Pneumorrhachis associated with bronchial asthma, subcutaneous emphysema and pneumomediastinum. Turk Neurosurg. 2011;21:666–668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhadane S., Singh H., Konde S., Sasane A.G. Pneumorrhachis associated with bronchial asthma. Med J Armed Forces India. 2011;67:93. doi: 10.1016/S0377-1237(11)80033-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanada T., Ishikuro A., Hasegawa Y., Shimamoto M., Kobayashi M., Kudo K. Two cases of spontaneous epidural emphysema during asthmatic attack. Respir Investig. 2012;50:62–65. doi: 10.1016/j.resinv.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Showkat H.I., Jan A., Sarmast A.H., Bhat G.M., Jan B.M., Bashir Y. Pneumomediastinum, pneumorachis, subcutaneous emphysema: an unusual complication of leukemia in a child. World J Clin Cases. 2013;1:224–226. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v1.i7.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sankar J., Jain A., Suresh C.P.Peanut aspiration leading to pneumorrhachis in a pre-schooler. BMJ CaseRep. 2013:bcr2012007675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Showkat H.I., Jan A., Sarmast A.H., Bhat G.M., Jan B.M., Bashir Y. Epidural air in child with spontaneous pneumomediastinum. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2013;23:249–250. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1313341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bilir O., Yavasi O., Ersunan G., Kayayurt K., Giakoup B. Pneumomediastinum associated with pneumopericardium and epidural pneumatosis. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/275490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Emiralioğlu N., Ozcan H.N., Oğuz B., Yalçın E., Doğru D., Özçelik U., Kiper N. Pneumomediastinum, pneumorrhachis and subcutaneous emphysema associated with viral infections: report of three cases. Pediatr Int. 2015;57:1038–1040. doi: 10.1111/ped.12785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Colavita L., Cuppari C., Pizzino M.R., Sturiale M., Mondello B., Monaco F., Barone M., Salpietro C. Pneumomediastinum, subcutaneous emphysema and pneumorrhachis in asthmatic children. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2016;30:585–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fantacci C., Ferrara P., Franceschi F., Chiaretti A. Pneumopericardium, pneumomediastinum, and pneumorrachis complicating acute respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis in children. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2017;21:3465–3468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borem L.M.A., Stamoulis D.N.J., Ramos A.F.M. A rare case of pneumorrhachis accompanying spontaneous pneumomediastinum. Radiol Bras. 2017;50:345–346. doi: 10.1590/0100-3984.2015.0031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hochhegger B., Irion K.L., Hochhegger D., Santos C.S.P., Marchiori E. Pneumorrhachis as a complication of bronchial asthma: computed tomography findings. Radiol Bras. 2018;51:268. doi: 10.1590/0100-3984.2016.0228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guataqui A.E.C., Muniz B.C., Ribeiro B.N.F., Spielmann L.H., Milito M.A. Hamman's syndrome accompanied by pneumorrhachis. Radiol Bras. 2019;52:64–65. doi: 10.1590/0100-3984.2017.0141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Song K.J., Lee K.B. Spontaneous extradural pneumorrhachis causing cervical myelopathy. Spine J. 2009;9:e16–e18. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]