Abstract

Background

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) is the most common monogenic cause of renal failure. For several decades, ADPKD was regarded as an adult-onset disease. In the past decade, it has become more widely appreciated that the disease course begins in childhood. However, evidence-based guidelines on how to manage and approach children diagnosed with or at risk of ADPKD are lacking. Also, scoring systems to stratify patients into risk categories have been established only for adults. Overall, there are insufficient data on the clinical course during childhood. We therefore initiated the global ADPedKD project to establish a large international pediatric ADPKD cohort for deep characterization.

Methods

Global ADPedKD is an international multicenter observational study focusing on childhood-diagnosed ADPKD. This collaborative project is based on interoperable Web-based databases, comprising 7 regional and independent but uniformly organized chapters, namely Africa, Asia, Australia, Europe, North America, South America, and the United Kingdom. In the database, a detailed basic data questionnaire, including genetics, is used in combination with data entry from follow-up visits, to provide both retrospective and prospective longitudinal data on clinical, radiologic, and laboratory findings, as well as therapeutic interventions.

Discussion

The global ADPedKD initiative aims to characterize in detail the most extensive international pediatric ADPKD cohort reported to date, providing evidence for the development of unified diagnostic, follow-up, and treatment recommendations regarding modifiable disease factors. Moreover, this registry will serve as a platform for the development of clinical and/or biochemical markers predicting the risk of early and progressive disease.

Keywords: ADPKD, ADPedKD Registry, children, longitudinal

ADPKD is the most common monogenic cause of renal failure, and therefore constitutes a substantial worldwide socioeconomic health concern. This multiorgan disorder arises due to gene mutations in the PKD genes: PKD1, in up to 85% of cases, and PKD2, in approximately 15% of cases, encoding the polycystin proteins PC1 and PC2, respectively.1 Recently, mutations in GANAB and DNAJB11 have been described to cause rare, atypical forms of ADPKD.2, 3

ADPKD is typically characterized by bilateral, progressive cyst formation and growth in all nephron segments, often leading to end-stage kidney disease. Although there is substantial individual variability in phenotypic severity,4 there are clear renal phenotype progression patterns associated with differing genetic backgrounds. Indeed, adults with PKD2 mutations are more mildly affected compared with patients with PKD1. Among the latter, carriers of truncating mutations are more seriously affected than nontruncating mutation carriers.5 Evidence has been published demonstrating interventions that slow disease progression in adults: the vasopressin-2-receptor antagonist tolvaptan,6 and meticulous attention to blood pressure.7, 8

Importantly, ADPKD is not an isolated renal disease, as patients may display a broad range of extrarenal phenotypes, including polycystic liver disease, inguinal hernias, intracranial aneurysms, and cardiac valve abnormalities.9, 10 The current consensus holds that extrarenal manifestations are rare in childhood; however, this has not been rigorously studied, and our registry will address this gap in knowledge.

For several decades, ADPKD was regarded as an adult-onset disease, but initial cyst formation starts in utero.11 Possible symptoms, such as urinary concentration defects, hypertension, and proteinuria, have been described in childhood.12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 Moreover, early intervention needs to be considered to attenuate long-term renal and extrarenal complications.19 Guidelines unfortunately are lacking with regard to children diagnosed with ADPKD,20 and more controversially, those asymptomatically at risk for ADPKD based on family history,21 as shown in a recently performed survey of European caregivers.22 Diagnostic, follow-up, and treatment protocols for childhood ADPKD are therefore very heterogeneous, despite several initiatives undertaken to standardize patient care, namely the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) consensus, the first initiative to provide clinical practice guidelines on the management of ADPKD,23 the European ADPKD Forum (EAF) Reports,24, 25 and the Australasian Kidney Health Australia–Caring for Australasians with Renal Impairment (KHA-CARI) guidelines,26 and the very recently published international consensus statement.27

Strikingly, for most medical conditions, there is still a significant discrepancy regarding data obtained in adults versus children, explaining our current relative ignorance with regard to pediatric ADPKD (Table 128, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71). Moreover, the available data are often obtained from small cohorts, as neither long-term nor large cohorts of children affected by ADPKD have been published. The Colorado Registry published cohort data with retrospective follow-up of up to 16 years (Supplementary Table S1), but some results should be carefully interpreted, as at-risk children were included and regarded as non-ADPKD when they had no renal cysts on ultrasound before the age of 18 years even if the disease was not ruled out by genetic analysis.17, 28, 72 As illustrated in Supplementary Table S1, diagnostic criteria for childhood ADPKD are highly variable, leading to incomparable study groups and results.

Table 1.

Overview of the literature of adult versus pediatric ADPKD

| Studied topic | Adult ADPKD | Pediatric ADPKD |

|---|---|---|

| Routine presymptomatic screening for at-risk persons | Recommended25 | Not recommended,25 but polarized opinion among caregivers22 |

| Diagnostic criteria | Renal ultrasound criteria28 | Renal ultrasound criteria only applicable from the age of 15 yr28 |

| Prevalence | No reports | |

| Renal manifestations and complications (frequency, % of studied patients) |

|

|

| Extrarenal manifestations and complications (frequency, % of studied patients) |

|

|

| FDA-approved prognostic enrichment biomarker | (ht)TKV since 201658 | No reports |

| Validated prognostic indicators |

PKD genotype5 TKV33 |

No reports |

| Suggested prognostic indicators (in bold those suggested in both adult and pediatric populations) | Age, male sex, LBW, race, BMI, BSA, PKD genotype, ciliopathy genes (e.g., HNF1B), low RBF, hypertension, urologic events, chronic asymptomatic pyuria, presence of hernia, TKV, (e)GFR, proteinuria, cholesterol, urinary sodium excretion, urine osmolality, uric acid, thrombocyte count, copeptin, plasma ADH, MCP-1, high caffeine intake, high protein intake, low water intake and smoking4, 59 | VEO ADPKD,60, 61, 62, 63hypertension,12, 13, 14, 49, 64 glomerular hyperfiltration,46PKD genotype,65, 66proteinuria,17urine osmolality,44 presentation at diagnosis (screening versus symptoms),15, 63 and LVMI13 |

| Patient stratification scoring systems predicting disease progression | No reports | |

| Evidence-based interventions to slow down disease progression, currently in clinical practice | ACEi if blood pressure > percentile 95 for age, sex, and height23; however, the only RCT performed in the pediatric cohort failed to demonstrate a significant effect of ACEi on renal growth over the 5-yr study period71 |

ACEi, angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor; ADH, antidiuretic hormone; ADPKD, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease; ADPKD-OM, ADPKD Outcomes Model; BMI, body mass index; BSA, body surface area; (e)GFR, (estimated) glomerular filtration rate; ESKD, end-stage kidney disease; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; (ht)TKV, (height-adjusted) total kidney volume; LBW, low birth weight; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1; PRO-PKD, predicting renal outcomes in ADPKD; RBF, renal blood flow; RCT, randomized clinical trial; VEO, very early onset.

Scoring systems to stratify patients into risk categories for end-stage kidney disease development, mainly based on height-adjusted total kidney volume (htTKV)73 and ADPKD genotype,5 have been developed for adult patients.67, 68, 69 In children, no progression markers have been validated yet, although some are suggested, such as the appearance of very early onset polycystic kidney disease. In this group, in whom ADPKD is diagnosed in utero or within the first 18 months of life, clinical outcomes are worse compared with non–very early onset ADPKD.60 Other clinical or biochemical risk makers have not yet been established for childhood ADPKD, nor have screening and treatment approaches. This demonstrates the need for a large pediatric cohort in which these and other relevant factors will be studied. This is of growing importance, as ADPKD-affected children are increasingly regarded as candidates for early treatment of modifiable morbidities, as well as for future therapies, once available.11, 19 Therefore, we have aimed to initiate the global ADPedKD registry to build a large, longitudinal international childhood-diagnosed ADPKD cohort, detailing with both renal and extrarenal disease manifestations and including familial and genetic data.

Methods

Aim of the Study

Global ADPedKD is an international, multicenter, observational study, including both retrospective and prospective longitudinal data. As data on pediatric ADPKD are scarce, the study is designed to generate data on its prevalence and presentation in childhood, and of its comorbidities, such as hypertension, left ventricular hypertrophy, and proteinuria. Thereby, we aim to provide an observational evidence base for the development of unified diagnostic, follow-up, and treatment recommendations to slow disease progression. Second, our goal is to establish clinical markers predicting the risk of early progressive disease, and thus to combine disease progression factors for pediatric ADPKD into a pediatric scoring system. The latter could enable caregivers to stratify patients from an early disease stage into low to high risk categories, to determine the required intensity of follow-up and to select patients for potential future therapies. Particular attention will be paid to the initial presentation, prenatal and perinatal history, familial history, genetic analysis, and longitudinal evolution of renal function and volume. Finally, ADPedKD will generate a well-characterized cohort that will be available for epidemiologic studies in the future, and possibly lay the foundation for future clinical trial patient selection. The participation of major pediatric nephrology centers throughout Africa, Asia, Australia, Europe, North America, South America, and the United Kingdom will optimize patient enrollment and will expedite new knowledge transfer into clinical patient care, while harmonizing the quality of care for this patient group globally. The study is endorsed by University Hospitals Leuven, the Working Group of Inherited Kidney Diseases of the European Society of Pediatric Nephrology, the International Pediatric Nephrology Association, the Working Group of Inherited Kidney Diseases of the European Renal Association–European Dialysis and Transplant Association, and the European Reference Network for Rare Kidney Diseases. Furthermore, the members of the Executive Committee will engage with local pediatric nephrology communities via local organizations in the various international regions and jurisdictions. Another ongoing outreach effort is through the European ADPKD Forum, and the patient organizations PKD International (Switzerland) and PKD Foundation (United States).

Executive Committee

ADPedKD was initiated by UZ Leuven, Djalila Mekahli, and Max C. Liebau. The global ADPedKD platform was initiated and coordinated by UZ Leuven, Stéphanie De Rechter, and Djalila Mekahli. The Global Executive Committee will be responsible for the governance of global ADPedKD. The members are, in alphabetical order, Detlef Bockenhauer, Stéphanie De Rechter, Lisa M. Guay-Woodford, Max C. Liebau, Isaac Liu, Andrew J. Mallett, Djalila Mekahli, Franz Schaefer, L.C. Sylvestre, and Neveen A. Soliman. These members will also lead the Regional Operational Committees, in Africa (Neveen A. Soliman), Asia (Isaac Liu), Australia (Andrew J. Mallett), Europe (Stéphanie De Rechter, Franz Schaefer, Max C. Liebau, and Djalila Mekahli), North America (Lisa M. Guay-Woodford), South America (L.C. Sylvestre), and the United Kingdom (Detlef Bockenhauer) and coordinate the participation of patients and centers in their region. All the data will be protected and managed by the Executive Committee. Requests for data and/or research proposals will be handled by the Global Executive and Regional Operational Committees. Furthermore, each participating center is exclusively able to review the data from the corresponding site after request.

Characteristics of Participants

Patients eligible for inclusion are individuals diagnosed with ADPKD before the age of 19 years. Each pediatric center will have the option to include data from their patients who have transitioned to adult clinics. This “transitioned” cohort will allow us to optimize our analysis on long-term progression. The diagnosis is defined by the presence of at least 1 renal cyst with a positive family history74 and/or a positive molecular assessment of the known ADPKD genes. Also, children diagnosed with the contiguous gene syndrome (TSC2-PKD1) will be included and studied as a subgroup. Patient inclusion is preceded by written informed consent of the patient and/or their parents or legal representatives, after approval of the study and the related study documents, including informed consent forms by the corresponding local ethics committee. Patients can be included only by their treating nephrologists and cannot participate directly in the registry without involvement of their treating clinician/s. The study has been reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of University Hospitals Leuven (S59638) as the leading center and confirmed by the local institutional review boards of all participating centers, including the lead centers in Africa, Asia, Australia, Europe, North America, South America, and the United Kingdom. The study is conducted according to the 2013 Declaration of Helsinki, the guidelines of Good Clinical Practice, and with all applicable regulatory requirements, including the recently enforced European Union General Data Protection Regulation.75

Design of the Study and Study Procedures

This global collaborative project is based on interoperable Web-based databases, comprising 7 regional and independent but uniformly organized chapters, each led by their own principal investigator, namely Africa, Asia, Australia, Europe, North America, South America, and the United Kingdom. After signing the informed consent forms, patients’ data are pseudonymously entered by the patient’s caregiver and/or his or her team member(s) in the Web-based database, accessible via https://www.adpedkd.org/. Local investigators are able to access the ADPedKD Web site at any time for the following purposes: entering and editing data, posing questions, and accessing center enrollment overview. Also, the Downloads section of the Web site gives access to all study-related documents, including a handbook, patient information, and informed consent forms sorted per language for all participating countries and the complete study protocol and ethics committee statement. Currently, we already have 11 languages available (Dutch, English, French [Belgium], French [France], German, Italian, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Serbian, and Turkish).

Africa, Asia, and Europe share 1 common database. Its data entry section is secured by restriction to a personal username and password for each investigator. Moreover, the use of Secure Sockets Layer encrypted-connections ensure data protection. Only the responsible local study site is able to identify their own included subjects based on the identification pseudonym, and this will be protected from disclosure as described in both the research protocol and informed consent forms. Therefore, participating centers are exclusively able to review and/or modify data of patients from the corresponding site and are responsible for data protection. To ensure the highest levels of data quality, the online case report forms require mandatory inclusion of key variables and include automated entry checks based on predefined plausibility ranges. Moreover, wherever possible, values are calculated and updated automatically. For instance: body mass index, weight standard deviation score, height SD score, and body mass index SD score are calculated automatically after entry of weight and height, based on the World Health Organization reference standards, as these can be applied to all children regardless of ethnicity, socioeconomic status, or type of feeding.76 Also, in case of different standard units, laboratory results are converted automatically. By these precautions, the risk of data entry errors or incomplete data is minimized. Next, data entries will be randomly reviewed, during regular interim analyses and for outlying values, a query will be sent to the local investigators.

Data acquisition (Figure 1) is subdivided into 3 sections: basic data, visits (initial and follow-up), and study termination (Table 2).

Figure 1.

ADPedKD study design. ICF, informed consent form.

Table 2.

Overview of data captured in ADPedKD, including ADPedKD Australia (via Australasian Registry of Rare and Genetic Kidney disease), ADPKD North America (via Hepatorenal Fibrocystic Diseases [HRFD] Database) and ADPKD UK (via National Registry of Rare Kidney Diseases)

| Basic data |

|---|

|

| Initial visit/follow-up visits |

|

| Study termination |

|

ADPKD, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease; CNS, central nervous system; CV, cardiovascular; RRT, renal replacement therapy.

Australia and the United Kingdom have their separate source databases, namely Australasian Registry of Rare and genetic Kidney disease and National Registry of Rare Kidney Diseases, which are accessible via www.adpedkd.org or directly via www.kidgen.org.au and http://rarerenal.org/rare-disease-groups/adpkd-rdg/, respectively. These databases have a fully interoperable data structure with the ADPedKD database, including a uniform dataset. The Australasian Registry of Rare and genetic Kidney disease is embedded within the local KidGen Collaborative, and its Web site launch will occur within the coming months. It is designed to be a “node” of as well as interact with other global registry efforts. In North America, the ADPedKD Registry will be implemented under the auspices of the National Institutes of Health–funded Hepato-Renal Fibrocystic Disease database.77

Currently, the data are stored on a secure server, managed in Köln, Germany, for the European, Asian, African, and South American data. The National Registry of Rare Kidney Diseases (United Kingdom), United States, and Australia have their own secure data storage arrangements that have been established for this registry and other related registries, for example, the ARPKD Database (United States).

Depending on the participating center, we expect the number of children enrolled per center to range from a minimum of 10 to a maximum of 100, although this is an open registry with no formal maximal number of centers and patients. The anticipated sample size is 2000 patients.

Basic Data

Personal information on the pre- and perinatal period, the initial diagnosis, genetic information, and a detailed family history are documented (Figure 1, Table 2). The latter includes a questionnaire on family history of tuberous sclerosis complex, diabetes mellitus, intracranial aneurysm, gout, colon diverticulosis, heart valvular defects, liver cyst(s), pancreatic cyst(s), and kidney cyst(s) other than caused by ADPKD. Moreover, for all known affected family members, including children already included in ADPedKD (e.g., siblings or cousins) the age at diagnosis, age at end-stage kidney disease (if applicable), and abdominal imaging results are queried. This enables characterization of family phenotypes in detail.

Initial Visit/Follow-up Visits

After completion of the baseline data collection, data can be entered in the “visits” section, starting with the initial visit and further visits, which are suggested to be annual (Figure 1, Table 2). The latter is generated for the registration of clinical, radiologic, laboratory, and other findings of the different organ systems possibly affected in ADPKD (kidney, liver, cardiovascular, neurologic, eye, and others), apart from general information, including biometry (weight, height, blood pressure, heart rate, and Tanner staging78). The patient’s medication, even if not directly related to ADPKD, is entered, including dosing and duration. Other therapeutic interventions, such as cyst fenestration, dialysis, nephrectomy, renal transplantation, or other urological/surgical procedure, are noted with date, indication, and possible complications. An identical questionnaire is then available for all follow-up visits, to provide data on the clinical course in both a retrospective and prospective manner. For each visit, an open field box is provided at the end of this visit’s section, to add user-defined comments: any further symptoms, performed diagnostic procedures, or other developments.

Study Termination

In case the study is terminated, date and reason for this will be entered (Figure 1, Table 2). The patient might have future follow-up in a pediatric nephrology center not participating in ADPedKD, transition to adult nephrology care, it might be the patient’s wish to withdraw his or her informed consent, the patient might be deceased, or the patient might be lost to follow-up for another or unknown reason. In case of transfer to adult nephrology departments, the local site is asked to engage with the future center and provide contact with the adult nephrologist. Also, if patients subsequently participate in an adult ADPKD registry, the registry’s name and the patient’s registry ID will be requested. As several registries for adult ADPKD data are ongoing, we have added a specific item “termination of the study” in case of transfer to adult nephrology programs. The local site is asked to fill in the future center, the contact of the nephrologist, and if the patients will participate in an adult ADPKD registry, the registry’s name and the patient’s registry ID will be requested. This approach will allow us to trace the patient in the future and to merge registry data in collaboration with the adult nephrologist community. We note that the National Registry of Rare Kidney Diseases and Australasian Registry of Rare and Genetic Kidney disease initiatives include patients from all the ages on a national basis and it will be easier to track their course in the same database.

Importantly, in case of a transfer to another pediatric nephrology center participating in ADPedKD, the patient is not terminating the study. The local study site then informs the destination center about the transfer by filling in a transfer form available in this patient’s data entry section. The destination center can accept or decline the transfer, and in case of acceptance, the patient's data will be completely transferred to the new center, and the patient will “disappear” from the first site. A detailed overview of all collected data is given in the Supplementary Material.

Statistical Analysis

Initially, we will perform a descriptive analysis, including the calculation of relative and absolute frequencies for binary/categorical variables and of mean, SD, median, interquartile range, minimum, and maximum for the continuous variables. Further longitudinal data regarding outcomes of markers of renal function, renal size and volume, and cardiovascular morbidity will be analyzed using appropriate statistical methods, such as mixed modeling. Missing data will be handled by means of multiple imputation. Also, the aspect of multiple testing and potential sources of bias will be examined and considered in all analyses. If required, the distribution of variables will be normalized by appropriate transformation. Methods will also include multivariable adjusted linear and logistic regression analysis for cross-sectional data, and linear regression and proportional hazards regression for longitudinal data. Stepwise regression procedures (P value for entry and removal set at 0.15) will be applied to identify potential important covariables. We will search for optimized discrimination limits for predictive baseline factors by maximizing Youden's index.

Discussion

The global ADPedKD initiative aims to remedy the current paucity of information regarding pediatric ADPKD, especially from regions other than Europe and the United States (Table 1, Supplementary Table S1). Patient registries are well-recognized tools to advance epidemiological characterization of patient cohorts and to evaluate clinical therapies.79 Future analyses of the ADPedKD Registry will be conducted to increase the understanding of disease progression from early disease stages. Data gathered during the follow-up period will be collected from clinicians worldwide and will be valuable to help describe childhood ADPKD prevalence, presentation, progression, and current management and its effect on the disease history (e.g., strict versus standard blood pressure control) and patient outcomes. Initial focus will be placed on undertaking a descriptive analysis of the dataset, once enrollment reaches 1000 patients. These initial cross-sectional analyses will focus on the prevalence of renal and extrarenal disease manifestations, the current practices in different regions of the world regarding monitoring and treatment. For this, data at inclusion, including sonomorphological markers, family history, and genetics, will be analyzed. The documented prevalence might be different from adult ADPKD prevalence, given the controversy about testing for disease presence in minors22 and the fact that the ADPKD diagnosis in children might have different origins: by coincidence via ultrasound for another reason, or by a presenting symptom such as a urinary tract infection, hematuria, or bedwetting.44 Also, children might be diagnosed prenatally, and in some cases because of screening by means of renal ultrasound or genetic analysis of the ADPKD genes on parental request. Moreover, diagnosis of the disease and its different renal and extrarenal manifestations might be region-specific, as this is dependent on patients’ and caregivers’ awareness, availability of resources, and organization of health care.80 These will be important confounders in our analysis of region-specific differences and their effects on outcomes.

Longer term, we will focus on longitudinal data to assess disease progression and evaluate risk factors that distinguish slow versus rapid disease progression. These analyses will facilitate appropriate patient selection for future clinical trials. As part of these analyses, we will assess whether hypertension of varying grades and other possible disease features, such as proteinuria and left ventricular hypertrophy, should be regarded as modifiable risk factors, early treatment of which can slow disease progression. Moreover, the registry will provide us with the current clinical practice regarding monitoring of hypertension and its treatment, including the most recommended drug class for this indication, namely angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors. As the only randomized controlled trial evaluating the use of angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors in pediatric ADPKD in a limited number of children did not show a treatment benefit over a 5-year follow-up period,71 we will evaluate angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor use versus other antihypertensive drug classes and its effect on renal volume and function from the registry’s observational data. We will also be able to compare outcomes of children with low blood pressure (≤50th percentile for age, sex, and height23) versus standard blood pressure (≤95th percentile for age, sex, and height23) regardless of treatment, as this might be more relevant than antihypertensive treatment intensity, as shown in adults with ADPKD in the secondary analysis of HALT PKD Study A.81 Importantly, by these means, we will generate data not only from centers already involved in ADPKD research, but from nephrology centers worldwide.

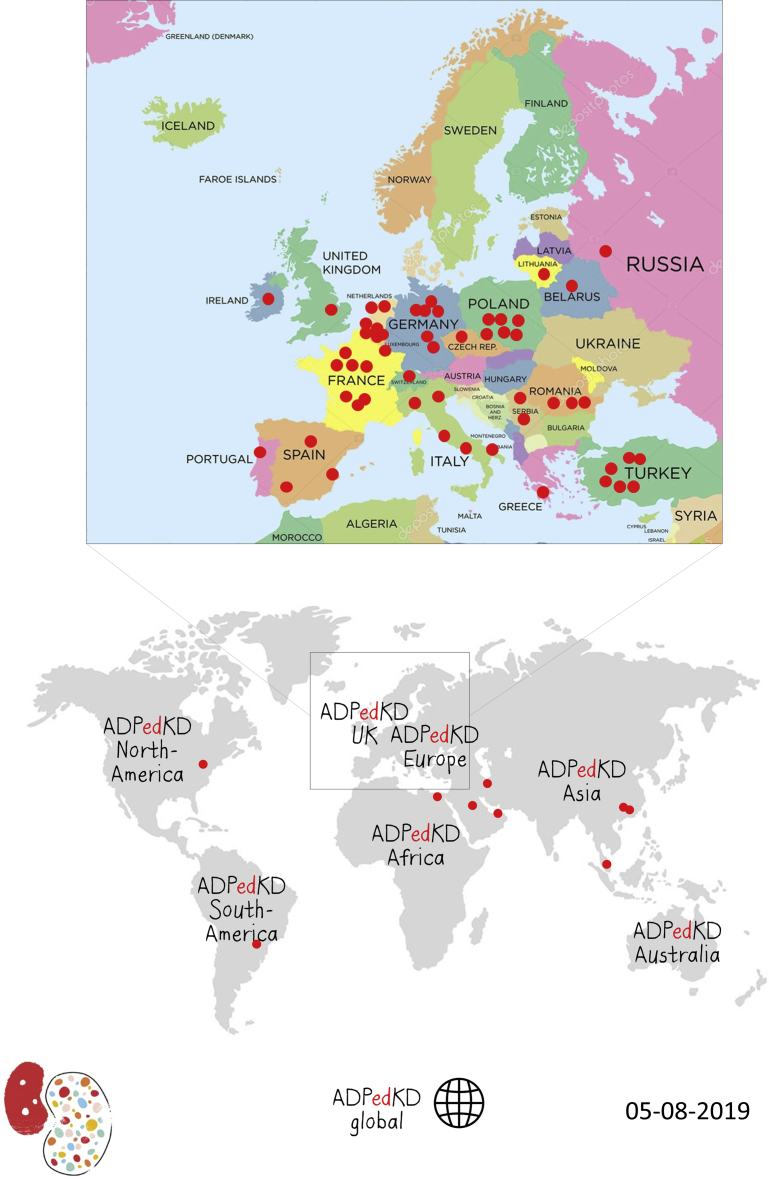

Currently, we already have 379 patients registered from 30 different centers. Another 41 centers are currently in the preenrollment phase (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

ADPedKD participating centers. Because inclusion of new centers is continuously growing, we mentioned the last date of production.

The strengths of this study are (i) the focus on an ADPKD cohort diagnosed during childhood, representing the earliest disease stages; (ii) the unique global collaboration established, with coverage of patients with ADPKD from infancy to young adulthood at pediatric nephrology centers around the world; (iii) the inclusion of diverse sociodemographic backgrounds; and (iv) the possibility to characterize family phenotypes, based on data from both pediatric patients with ADPKD and their (adult) relatives.

However, we recognize the inevitable possibility of selection bias. We will not be able to include information on undiagnosed children at risk for ADPKD, or on pregnancies terminated for ADPKD. Although the latter occurs only rarely in our experience, we have no incidence reported in the literature. According to a recent patient survey, 17% of patients with ADPKD with chronic kidney disease and 18% of patients with ADPKD with end-stage kidney disease would consider prenatal diagnosis or termination of pregnancy for ADPKD.82 Such selection bias may impact data analysis validity; however, given the paucity of data about childhood ADPKD, we accept this potential limitation and believe it to be outweighed by the numerous potential benefits inherent with such an initiative and approach. The immediate goal of ADPedKD is to describe current clinical practices and to analyze the patient population that is already under care in reference centers and tertiary hospitals. Although this approach might bias the cohort toward more severe cases, the lack of a validated approach for screening asymptomatic at-risk offspring suggests that this limitation is identifiable but unable to be minimized at present without clearer understanding more broadly of ADPKD in the pediatric age group. Moreover, ADPedKD, like any registry study, will be limited by the use of real-life clinical data resulting in missing, incomplete, or inaccurate data entry, even despite the established automated plausibility checks. This is especially true for retrospectively entered data. Also, laboratory and molecular investigations are performed using multiple techniques. Finally, entering data is labor intensive and time-consuming, jeopardizing the completeness of reporting. Based on our beta-testing, completion of the case report form requires approximately 1 hour per patient visit, with some variation introduced by differences in how patient data are stored at each referral center storage. Going forward, we expect that with the global transition to electronic health records, data entry increasingly will be automated; however, funding will be sought to support centers with data entry.

In summary, the global ADPedKD registry aims to establish a large longitudinal pediatric ADPKD cohort, which will be jointly evaluated by the partners of the global ADPedPKD consortium.

Appendix

Members of the ADPedKD Consortium (alphabetically ordered)

P. Adamczyk (Department of Pediatrics, Zabrze, Poland), N. Akinci (Sariyer (SISLI) Hamidiye Etfal Research and Education Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey), H. Alpay (Marmara University, School of Medicine, Division of Pediatric Nephrology, İstanbul, Turkey), C. Ardelean (Timisoara Children Hospital, Timisoara, Romania), N. Ayasreh (Fundacio Puigvert, Barcelona, Spain), Z. Aydin (Ankara University of Health Sciences, Child Health and Disease, Ankara, Turkey), A. Bael (Koningin Paola Kinderziekenhuis Antwerpen, Belgium), V. Baudouin (Hopital Robert-Debré, APHP, Paris, France), U.S. Bayrakci (Ankara University of Health Sciences, Child Health and Disease, Ankara, Turkey), A. Bensman (Pediatric Nephrology Necker Hospital, Paris, France), H. Bialkevich (National Center for Pediatric Nephrology & RRT, 2nd City Childrens Clin Hosp, Minsk, Republic of Belarus), A. Biebuyck (Pediatric Nephrology Necker Hospital, Paris, France), O. Boyer (Pediatric Nephrology Necker Hospital, Paris, France), O. Bjanid (Department of Pediatrics, Zabrze, Poland), O. Boyer (Pediatric Nephrology Necker Hospital, Paris, France), A. Bryłka (Department of Pediatrics, Zabrze, Poland), S. Çalışkan (Istanbul Cerrahpasa Faculty of Medicine, Turkey), A. Cambier (Hopital Robert-Debré, APHP, Paris, France), A. Camelio (CHU de Besançon, France), V. Carbone (Pediatric Nephrology Unit Bari, Italy), M. Charbit (Pediatric Nephrology Necker Hospital, Paris, France), B. Chiodini (HUDERF, Brussels, Belgium), A. Chirita (Timisoara Children Hospital, Timisoara, Romania), N. Çiçek (Marmara University, School of Medicine, Division of Pediatric Nephrology, İstanbul, Turkey), R. Cerkauskiene (Vilnius, Lithuania), L. Collard (CHR La Citadelle, Liège, Belgium), M. Conceiçao (Centro Materno Infantil do Norte, Centro Hospitalar do Porto, Portugal), I. Constantinescu (Fundeni Clinical Institute, Bucharest, Romania), A. Couderc (Hopital Robert-Debré, APHP, Paris, France), B. Crapella (Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda - Pediatric Nephrology Dialysis and Transplant Unit, Milano, Italy), M. Cvetkovic (University Children's Hospital Belgrade, Serbia), B. Dima (Cliniques de l'Europe - Hôpital Sainte Elisabeth, Brussels, Belgium), F. Diomeda (Pediatric Nephrology Unit Bari, Italy), M. Docx (Koningin Paola Kinderziekenhuis Antwerpen, Belgium), N. Dolan (Our Lady’s Children’s Hospital, Dublin, Ireland), C. Dossier (Hôpital Robert-Debré, APHP, Paris, France), D. Drozdz (Pediatric Nephrology and Hypertension Jagiellonian University Medical College of Cracow, Cracow, Poland), J. Drube (Hannover Medical School, Hannover, Germany), O. Dunand (Pediatric Nephrology Unit St Denis, France), P. Dusan (University Children's Hospital Belgrade, Serbia), L.A. Eid (Pediatric Nephrology Department Dubai Hospital, Dubai, United Arab Emirates), F. Emma (Bambino Gesu Children's Hospital, Rome, Italy), M. Espino Hernandez (Hospital Infantil 12 de Octubre Madrid, Madrid, Spain), M. Fila (CHU Arnaud de Villeneuve, Montpellier, France), M. Furlano (Fundacio Puigvert, Barcelona, Spain), M. Gafencu (Timisoara Children Hospital, Timisoara, Romania), MS. Ghuysen (CHU Liège, Belgium), M. Giani (Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda - Pediatric Nephrology Dialysis and Transplant Unit, Milano, Italy), M. Giordano (Pediatric Nephrology Unit, Bari, Italy), I. Girisgen (Pamukkale University Medical Faculty Department of Pediatric Nephrology, Denizli, Turkey), N. Godefroid (Cliniques Universitaires Saint-Luc, Brussels, Belgium), A. Godron-Dubrasquet (Bordeaux University Children's Hospital, France), I. Gojkovic (University Children's Hospital Belgrade, Serbia), E. Gonzalez (Children's University Hospital, Geneva, Switzerland), I Gökçe (Marmara University, School of Medicine, Division of Pediatric Nephrology, İstanbul, Turkey), JW. Groothoff (Emma Children's Hospital, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), S. Guarino (Università degli Studi della Campania Luigi Vanvitelli, Caserta, Italy), A. Guffens (CHC clinique de l'Espérence, Montegnée, Belgium), P. Hansen (CHU Tivoli, La Louvière, Belgium), J. Harambat (Bordeaux University Children's Hospital, France), S. Haumann (Universitätsklinikum Köln, Germany), G. He (Foshan Women and Children Hospital, Foshan City, China), L. Heidet (Pediatric Nephrology Necker Hospital, Paris, France), R. Helmy (Kasr Al Ainy School of Medicine, Cairo University, Cairo, Egypt), F. Hemery (CHU Arnaud de Villeneuve, Montpellier, France), N. Hooman (Aliasghar Clinical Research Development Unit, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran), B. llanas (Bordeaux University Children's Hospital, France), A. Jankauskiene (Vilnius, Lithuania), P. Janssens (University Hospital Brussels, Brussels, Belgium), S. Karamaria (UZ Gent, Belgium), I. Kazyra (National Center for Pediatric Nephrology & RRT, 2nd City Childrens Clin Hosp, Minsk, Republic of Belarus), J. Koenig (University Hospital Muenster, Germany), S. Krid (Pediatric Nephrology Necker Hospital, Paris, France), P. Krug (Pediatric Nephrology Necker Hospital, Paris, France), V. Kwon (Hopital Robert-Debré, APHP, Paris, France), A. La Manna (Università degli Studi della Campania Luigi Vanvitelli, Caserta, Italy), V. Leroy (Pediatric Nephrology Unit St Denis, France), M. Litwin (The Children’s Memorial Health Institute, Warsaw, Poland), J. Lombet (CHR Citadelle, Liège, Belgium), G. Longo (Pediatric Nephrology, Dialysis and Transplant Unit-Hospital University of Padova, Italy), AC. Lungu (Fundeni Clinical Institute, Bucharest, Romania), A. Mallawaarachchi (Garvan Institute; Royal Prince Alfred Hospital; and KidGen), A. Marin (Fundeni Clinical Institute, Bucharest, Romania), P. Marzuillo (Università degli Studi della Campania Luigi Vanvitelli, Caserta, Italy), L. Massella (Bambino Gesu Children's Hospital, Rome, Italy), A. Mastrangelo (Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda - Pediatric Nephrology Dialysis and Transplant Unit, Milano, Italy), H. McCarthy (Childrens Hospital Westmead and Sydney Children’s Hospital; and KidGen), M. Miklaszewska (Pediatric Nephrology and Hypertension Jagiellonian University Medical College of Cracow, Cracow, Poland), A. Moczulska (Pediatric Nephrology and Hypertension Jagiellonian University Medical College of Cracow, Cracow, Poland), G. Montini (Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda - Pediatric Nephrology Dialysis and Transplant Unit, Milano, Italy), A. Morawiec-Knysak (Department of Pediatrics, Zabrze, Poland), D. Morin (CHU Arnaud de Villeneuve, Montpellier, France), L. Murer (Pediatric Nephrology, Dialysis and Transplant Unit-Hospital University of Padova, Italy), I. Negru (Fundeni Clinical Institute, Bucharest, Romania), F. Nobili (CHU de Besançon, France), L. Obrycki (The Children’s Memorial Health Institute, Warsaw, Poland), H. Otoukesh (Aliasghar Clinical Research Development Unit, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran), S. Özcan (Istanbul Cerrahpasa Faculty of Medicine, Turkey), L. Pape (Hannover Medical School, Hannover, Germany), S. Papizh (Research & Clinical Institute for Pediatrics, Pirogov Russian Nat. Res. Med. Uni, Moscow, Russian Federation), P. Parvex (Children's University Hospital Geneva, Switzerland), M. Pawlak-Bratkowska (Polish Mother's Memorial Hospital Research Institute, Lodz, Poland), L. Prikhodina (Research & Clinical Institute for Pediatrics, Pirogov Russian Nat. Res. Med. Uni., Moscow, Russian Federation), A. Prytula (UZ Gent, Belgium), C. Quinlan (RCH Melbourne and KidGen), A. Raes (UZ Gent, Belgium), B. Ranchin (Hôpital Femme Mère Enfant, Bron, France), N. Ranguelov (Cliniques Universitaires Saint-Luc, Brussels, Belgium), R. Repeckiene (Vilnius, Lithuania), C. Ronit (Clinique Pédiatrique du Centre Hospitalier de Luxembourg, Luxembourg), R. Salomon (Pediatric Nephrology Necker Hospital, Paris, France), R. Santagelo (Pediatric Nephrology Unit Bari, Italy), SK. Saygılı (Istanbul Cerrahpasa Faculty of Medicine, Turkey), S. Schaefer (Division of Pediatric Nephrology Center for Pediatrics & Adolescent, Heidelberg, Germany), M. Schreuder (Radboudumc Amalia Children's Hospital, Nijmegen, the Netherlands), T. Schurmans (CHU Charleroi, Belgium), T. Seeman (Charles University in Prague and Motol University Hospital, Prague, Czech Republic), N. Segers (Koningin Paola Kinderziekenhuis Antwerpen, Belgium), M. Sinha (Evelina London Children's Hospital, London, UK), E. Snauwaert (UZ Gent, Belgium), B. Spasojevic (University Children's Hospital Belgrade, Serbia), S. Stabouli (Department of Pediatrics, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece), C. Stoica (Fundeni Clinical Institute, Bucharest, Romania), R. Stroescu (Timisoara Children Hospital, Timisoara, Romania), E. Szczepanik (Polish Mother's Memorial Hospital Research Institute, Lodz, Poland), M. Szczepańska (Department of Pediatrics, Zabrze, Poland), K. Taranta-Janusz (Department of Pediatrics and Nephrology, Bialystok, Poland), A. Teixeira (Centro Materno Infantil do Norte, Centro Hospitalar do Porto, Porto, Portugal), J. Thumfart (Berlin Charité Universitätsmedizin, Berlin, Germany), M. Tkaczyk (Polish Mother's Memorial Hospital Research Institute, Lodz, Poland), R. Torra (Fundacio Puigvert, Barcelona, Spain), D. Torres (Pediatric Nephrology Unit Bari, Italy), N. Tram (CHU Charleroi, Belgium), B. Utsch (Department of Paediatrics, Herford Hospital, Germany), J. Vande Walle (UZ Gent, Belgium), R. Vieux (CHU de Besançon, France), R. Vitkevic (Vilnius, Lithuania), A. Wilhelm-Bals (Children's University Hospital Geneva, Switzerland), E. Wühl (Division of Pediatric Nephrology, Center for Pediatrics & Adolescent, Heidelberg, Germany), Z.Y. Yildirim (Istanbul University, Faculty of Medicine, Pediatric Nephrology Department, Istanbul, Turkey), S. Yüksel (Pamukkale University Medical Faculty, Department of Pediatric Nephrology, Denizli, Turkey), and K. Zachwieja (Pediatric Nephrology and Hypertension, Jagiellonian University Medical College of Cracow, Cracow, Poland).

Disclosure

All the authors declared no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Patient inclusion is preceded by informed consent of the patient and/or his or her parents or legal representatives, after approval of the study by a corresponding local ethics committee. The registry study protocol and patient informed consent forms have been reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of University Hospitals Leuven (S59638). The study is conducted according to the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki, the guidelines of Good Clinical Practice, and with all applicable regulatory requirements, including the recently enforced European Union General Data Protection Regulation.35

DM is supported by the Clinical Research Fund of UZ Leuven. LGW is supported by the UAB Hepatorenal Fibrocystic Disease Core Center (National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases P30 DK074038), the Polycystic Kidney Disease Foundation, and the Clinical and Translational Science Institute at Children’s National (CTSI-CN; NIH/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences UL1TR001876). MCL is supported by the Koeln Fortune program and the GEROK program of the Medical Faculty of University of Cologne. SDR is supported by the Fund for Scientific Research, Flanders 11M5214N.

To date, ADPedKD has been supported by an initiation award from the University Hospitals Leuven coordinating center, as well as a research grant from the European Society of Pediatric Nephrology and the European Renal Association–European Dialysis and Transplant Association. The funding agencies had no role in study design, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, or in the manuscript preparation.

The authors would like to thank the German Society for Pediatric Nephrology (GPN) for their endorsement; ‘VZW Bas, Stoere strijder’ for financial support of the project; and Joanna De Vis, Veerle Verbeek and Helga Wielandt for data entry of the Leuven patient cohort. The authors would like to thank the patients enrolled in the ADPedKD registry and their families.

Also, the authors acknowledge the effort, dedication, and commitment of the enrolling clinicians within the ADPedKD consortium (see Appendix for ADPedKD members).

Author Contributions

The authors had the following contribution to the manuscript: drafting of the manuscript: SDR; conception, design of the work, data collection, data interpretation: SDR, FS, MCL, and DM. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Table S1. Overview of published pediatric ADPKD cohorts (studies including subjects from the age of 15 year onward are not presented here).

Supplementary Data. Detailed overview of data entered in ADPedKD.

Supplementary Acknowledgements.

Contributor Information

Djalila Mekahli, Email: djalila.mekahli@uzleuven.be.

ADPedKD Consortium:

P. Adamczyk, N. Akinci, H. Alpay, C. Ardelean, N. Ayasreh, Z. Aydin, A. Bael, V. Baudouin, U.S. Bayrakci, A. Bensman, H. Bialkevich, A. Biebuyck, O. Boyer, O. Bjanid, O. Boyer, A. Bryłka, S. Çalışkan, A. Cambier, A. Camelio, V. Carbone, M. Charbit, B. Chiodini, A. Chirita, N. Çiçek, R. Cerkauskiene, L. Collard, M. Conceiçao, I. Constantinescu, A. Couderc, B. Crapella, M. Cvetkovic, B. Dima, F. Diomeda, M. Docx, N. Dolan, C. Dossier, D. Drozdz, J. Drube, O. Dunand, P. Dusan, L.A. Eid, F. Emma, M. Espino Hernandez, M. Fila, M. Furlano, M. Gafencu, M.S. Ghuysen, M. Giani, M. Giordano, I. Girisgen, N. Godefroid, A. Godron-Dubrasquet, I. Gojkovic, E. Gonzalez, I. Gökçe, J.W. Groothoff, S. Guarino, A. Guffens, P. Hansen, J. Harambat, S. Haumann, G. He, L. Heidet, R. Helmy, F. Hemery, N. Hooman, B. llanas, A. Jankauskiene, P. Janssens, S. Karamaria, I. Kazyra, J. Koenig, S. Krid, P. Krug, V. Kwon, A. La Manna, V. Leroy, M. Litwin, J. Lombet, G. Longo, A.C. Lungu, A. Mallawaarachchi, A. Marin, P. Marzuillo, L. Massella, A. Mastrangelo, H. McCarthy, M. Miklaszewska, A. Moczulska, G. Montini, A. Morawiec-Knysak, D. Morin, L. Murer, I. Negru, F. Nobili, L. Obrycki, H. Otoukesh, S. Özcan, L. Pape, S. Papizh, P. Parvex, M. Pawlak-Bratkowska, L. Prikhodina, A. Prytula, C. Quinlan, A. Raes, B. Ranchin, N. Ranguelov, R. Repeckiene, C. Ronit, R. Salomon, R. Santagelo, S.K. Saygılı, S. Schaefer, M. Schreuder, T. Schurmans, T. Seeman, N. Segers, M. Sinha, E. Snauwaert, B. Spasojevic, S. Stabouli, C. Stoica, R. Stroescu, E. Szczepanik, M. Szczepańska, K. Taranta-Janusz, A. Teixeira, J. Thumfart, M. Tkaczyk, R. Torra, D. Torres, N. Tram, B. Utsch, J. Vande Walle, R. Vieux, R. Vitkevic, A. Wilhelm-Bals, E. Wühl, Z.Y. Yildirim, S. Yüksel, and K. Zachwieja

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Torres V.E., Harris P.C., Pirson Y. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Lancet. 2007;369:1287–1301. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60601-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cornec-Le Gall E., Olson R.J., Besse W. Monoallelic mutations to DNAJB11 cause atypical autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2018;102(5):832–844. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Porath B., Gainullin V.G., Cornec-Le Gall E. Mutations in GANAB, encoding the glucosidase IIalpha subunit, cause autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney and liver disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;98(6):1193–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ong A.C., Devuyst O., Knebelmann B., Walz G. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: the changing face of clinical management. Lancet. 2015;385:1993–2002. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60907-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cornec-Le Gall E., Audrézet M.P., Chenn J.M. Type of PKD1 mutation influences renal outcome in ADPKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:1006–1013. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012070650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torres V.E., Chapman A.B., Devuyst O. Tolvaptan in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2407–2418. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1205511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schrier R.W., Abebe K.Z., Perrone R.D. Blood pressure in early autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2255–2266. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Torres V.E., Abebe K.Z., Chapman A.B. Angiotensin blockade in late autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2267–2276. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ecder T., Schrier R.W. Cardiovascular abnormalities in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2009;5:221–228. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2009.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mikolajczyk A.E., Te H.S., Chapman A.B. Gastrointestinal manifestations of autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grantham J.J. Rationale for early treatment of polycystic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2014;30:1053–1062. doi: 10.1007/s00467-014-2882-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cadnapaphornchai M.A., Masoumi A., Strain J.D. Magnetic resonance imaging of kidney and cyst volume in children with ADPKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:369–376. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03780410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cadnapaphornchai M.A., McFann K., Strain J.D. Increased left ventricular mass in children with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease and borderline hypertension. Kidney Int. 2008;74:1192–1196. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Massella L., Mekahli D., Paripovic D. Prevalence of hypertension in children with early-stage ADPKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13:874–883. doi: 10.2215/CJN.11401017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mekahli D., Woolf A.S., Bockenhauer D. Similar renal outcomes in children with ADPKD diagnosed by screening or presenting with symptoms. Pediatr Nephrol. 2010;25:2275–2282. doi: 10.1007/s00467-010-1617-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Selistre L., de Souza V., Ranchin B. Early renal abnormalities in children with postnatally diagnosed autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2012;27:1589–1593. doi: 10.1007/s00467-012-2192-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharp C., Johnson A., Gabow P. Factors relating to urinary protein excretion in children with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998;9:1908–1914. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V9101908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rizk D., Chapman A. Treatment of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD): the new horizon for children with ADPKD. Pediatr Nephrol. 2008;23:1029–1036. doi: 10.1007/s00467-007-0706-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cadnapaphornchai M.A. Clinical trials in pediatric autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Front Pediatr. 2017;5:53. doi: 10.3389/fped.2017.00053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Rechter S., Breysem L., Mekahli D. Is autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease becoming a pediatric disorder? Front Pediatr. 2017;5:272. doi: 10.3389/fped.2017.00272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harris T. Is it ethical to test apparently "healthy" children for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease and risk medicalizing thousands? Front Pediatr. 2017;5:291. doi: 10.3389/fped.2017.00291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Rechter S., Kringen J., Janssens P. Clinicians' attitude towards family planning and timing of diagnosis in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. PLoS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chapman A.B., Devuyst O., Eckardt K.U. Autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD): executive summary from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int. 2015;88:17–27. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.European ADPKD Forum. Translating science into policy to improve ADPKD care. Available at: https://pkdinternational.org/component/content/article/2-uncategorised/3-european-adpkd-forum-report-launched. Published January 29, 2015. Accessed July 6, 2019.

- 25.Co-chairs E.A.F., Harris T., Sandford R. European ADPKD Forum multidisciplinary position statement on autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease care: European ADPKD Forum and Multispecialist Roundtable participants. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2018;33:563–573. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfx327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rangan G.K., Savige J. Introduction to the KHA-CARI guidelines on ADPKD. Semin Nephrol. 2015;35:521–523. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gimpel C, Bergmann C, Bockenhauer D, et al. International consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease in children and young people [e-pub ahead of print]. Nat Rev Nephrol. 10.1038/s41581-019-0155-2. Published May 22, 2019. Accessed July 2, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Pei Y., Obaji J., Dupuis A. Unified criteria for ultrasonographic diagnosis of ADPKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:205–212. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008050507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Willey C.J., Blais J.D., Hall A.K. Prevalence of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease in the European Union. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32:1356–1363. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfw240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yersin C., Bovet P., Wauters J.P. Frequency and impact of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease in the Seychelles (Indian Ocean) Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12:2069–2074. doi: 10.1093/ndt/12.10.2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iglesias C.G., Torres V.E., Offord K.P. Epidemiology of adult polycystic kidney disease, Olmsted County, Minnesota: 1935–1980. Am J Kidney Dis. 1983;2:630–639. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(83)80044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Higashihara E., Nutahara K., Kojima M. Prevalence and renal prognosis of diagnosed autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease in Japan. Nephron. 1998;80:421–427. doi: 10.1159/000045214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grantham J.J., Torres V.E., Chapman A.B. Volume progression in polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2122–2130. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gabow P.A., Duley I., Johnson A.M. Clinical profiles of gross hematuria in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 1992;20:140–143. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)80541-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chapman A.B., Johnson A.M., Gabow P.A., Schrier R.W. Overt proteinuria and microalbuminuria in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1994;5:1349–1354. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V561349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martinez-Vea A., Gutierrez C., Bardají A. Microalbuminuria in normotensive patients with autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1998;32:356–359. doi: 10.1080/003655998750015331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Idrizi A., Barbullushi M., Koroshi A. Urinary tract infections in polycystic kidney disease. Med Arh. 2011;65:213–215. doi: 10.5455/medarh.2011.65.213-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.D'Agnolo H.M.A., Casteleijn N.F., Gevers T.J.G. The association of combined total kidney and liver volume with pain and gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with later stage autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Am J Nephrol. 2017;46:239–248. doi: 10.1159/000479436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fick G.M., Duley I.T., Johnson A.M. The spectrum of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease in children. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1994;4:1654–1660. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V491654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dimitrakov D., Simeonov S. Studies on nephrolithiasis in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Folia Med (Plovdiv) 1994;36:27–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gabow P.A., Kaehny W.D., Johnson A.M. The clinical utility of renal concentrating capacity in polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 1989;35:675–680. doi: 10.1038/ki.1989.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reddy B.V., Chapman A.B. The spectrum of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease in children and adolescents. Pediatr Nephrol. 2017;32:31–42. doi: 10.1007/s00467-016-3364-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Firinci F., Soylu A., Kasap Demir B. An 11-year-old child with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease who presented with nephrolithiasis. Case Rep Med. 2012;2012:428749. doi: 10.1155/2012/428749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Seeman T., Dusek J., Vondrák K. Renal concentrating capacity is linked to blood pressure in children with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Physiol Res. 2004;53:629–634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sallee M., Rafat C., Zahar J.R. Cyst infections in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:1183–1189. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01870309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Helal I., Reed B., McFann K. Glomerular hyperfiltration and renal progression in children with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:2439–2443. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01010211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bae K.T., Zhu F., Chapman A.B. Magnetic resonance imaging evaluation of hepatic cysts in early autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease: the Consortium for Radiologic Imaging Studies of Polycystic Kidney Disease cohort. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:64–69. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00080605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dell K.M. The spectrum of polycystic kidney disease in children. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2011;18:339–347. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Seeman T., Dusek J., Vondrichová H. Ambulatory blood pressure correlates with renal volume and number of renal cysts in children with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Blood Press Monit. 2003;8:107–110. doi: 10.1097/01.mbp.0000085762.28312.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marlais M., Cuthell O., Langan D. Hypertension in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: a meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child. 2016;101:1142–1147. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2015-310221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chapman A.B., Johnson A.M., Rainguet S. Left ventricular hypertrophy in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1997;8:1292–1297. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V881292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ivy D.D., Shaffer E.M., Johnson A.M. Cardiovascular abnormalities in children with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1995;5:2032–2036. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V5122032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zeier M., Geberth S., Schmidt K.G. Elevated blood pressure profile and left ventricular mass in children and young adults with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1993;3:1451–1457. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V381451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xu H.W., Yu S.Q., Mei C.L., Li M.H. Screening for intracranial aneurysm in 355 patients with autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. Stroke. 2011;42:204–206. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.578740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mikolajczyk A.E., Te H.S., Chapman A.B. Gastrointestinal manifestations of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kubo S., Nakajima M., Fukuda K. A 4-year-old girl with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease complicated by a ruptured intracranial aneurysm. Eur J Pediatr. 2004;163:675–677. doi: 10.1007/s00431-004-1528-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thong K.M., Ong A.C. Sudden death due to subarachnoid haemorrhage in an infant with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29(Suppl 4):iv121–iv123. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfu014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Food and Drug Administration. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/guidances/ucm458483.pdf Available at: Accessed September 2016.

- 59.Woon C., Bielinski-Bradbury A., O'Reilly K., Robinson P. A systematic review of the predictors of disease progression in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 2015;16:140. doi: 10.1186/s12882-015-0114-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nowak K.L., Cadnapaphornchai M.A., Chonchol M.B. Long-term outcomes in patients with very-early onset autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Am J Nephrol. 2016;44:171–178. doi: 10.1159/000448695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fick G.M., Johnson A.M., Strain J.D. Characteristics of very early onset autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1993;3:1863–1870. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V3121863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sedman A., Bell P., Manco-Johnson M. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease in childhood: a longitudinal study. Kidney Int. 1987;31:1000–1005. doi: 10.1038/ki.1987.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shamshirsaz A.A., Reza Bekheirnia M., Kamgar M. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease in infancy and childhood: progression and outcome. Kidney Int. 2005;68:2218–2224. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Seeman T., Sikut M., Konrad M. Blood pressure and renal function in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 1997;11:592–596. doi: 10.1007/s004670050343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Audrézet M.P., Corbiere C., Lebbah S. Comprehensive PKD1 and PKD2 mutation analysis in prenatal autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:722–729. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014101051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fencl F., Janda J., Bláhová K. Genotype-phenotype correlation in children with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2009;24:983–989. doi: 10.1007/s00467-008-1090-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cornec-Le Gall E., Audrézet M.P., Rousseau A. The PROPKD score: a new algorithm to predict renal survival in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;27:942–951. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015010016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Irazabal M.V., Rangel L.J., Bergstralh E.J. Imaging classification of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: a simple model for selecting patients for clinical trials. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:160–172. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013101138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McEwan P., Bennett Wilton H., Ong A.C.M. A model to predict disease progression in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD): the ADPKD Outcomes Model. BMC Nephrol. 2018;19:37. doi: 10.1186/s12882-017-0804-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gansevoort R.T., Arici M., Benzing T. Recommendations for the use of tolvaptan in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: a position statement on behalf of the ERA-EDTA Working Groups on Inherited Kidney Disorders and European Renal Best Practice. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31:337–348. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cadnapaphornchai M.A., McFann K., Strain J.D. Prospective change in renal volume and function in children with ADPKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:820–829. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02810608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fick-Brosnahan G.M., Tran Z.V., Johnson A.M. Progression of autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease in children. Kidney Int. 2001;59:1654–1662. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.0590051654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Alam A., Dahl N.K., Lipschutz J.H. Total kidney volume in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: a biomarker of disease progression and therapeutic efficacy. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:564–576. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Reddy B.V., Chapman A.B. The spectrum of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease in children and adolescents. Pediatr Nephrol. 2017;32:31–42. doi: 10.1007/s00467-016-3364-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.European Commission 2018 reform of EU data protection rules. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/priorities/justice-and-fundamental-rights/data-protection/2018-reform-eu-data-protection-rules_en Available at:

- 76.de Onis M. Update on the implementation of the WHO child growth standards. World Rev Nutr Diet. 2013;106:75–82. doi: 10.1159/000342550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Alzarka B., Morizono H., Bollman J.W. Design and implementation of the Hepatorenal Fibrocystic Disease Core Center Clinical Database: a centralized resource for characterizing autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease and other hepatorenal fibrocystic diseases. Front Pediatr. 2017;5:80. doi: 10.3389/fped.2017.00080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tanner J.M. Physical growth and development. In: Forfar J.O., Arnell C.C., editors. Textbook of Pediatrics. 2nd ed. Churchill Livingstone; Edinburgh: 1978. pp. 249–303. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gliklich R., Dreyer N., Leavy M., editors. Registries for Evaluating Patient Outcomes: A User's Guide. Third edition. Two volumes. (Prepared by the Outcome DEcIDE Center [Outcome Sciences, Inc., a Quintiles company] under Contract No. 290 2005 00351 TO7.) AHRQ Publication No. 13(14)-EHC111. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: April 2014. http://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/registries-guide-3.cfm Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 80.Soliman N.A., Nabhan M.M., Bazaraa H.M. Clinical and ultrasonographical characterization of childhood cystic kidney diseases in Egypt. Ren Fail. 2014;36:694–700. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2014.883996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Brosnahan G.M., Abebe K.Z., Moore C.G. Determinants of progression in early autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: is it blood pressure or renin-angiotensin-aldosterone-system blockade? Curr Hypertens Rev. 2018;14:39–47. doi: 10.2174/1573402114666180322110209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Swift O., Vilar E., Rahman B. Attitudes in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease toward prenatal diagnosis and preimplantation genetic diagnosis. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2016;20:741–746. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2016.0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.