Abstract

Lifestyle risk factors, including tobacco and alcohol use, poor nutrition, and inactivity, comprise the leading actual causes of death and disproportionately affect diverse, lower-income and vulnerable populations. Fundamentally influenced by social determinants of health (including poverty, social linkages, food access, and built environment), these “unhealthy lifestyle” exposures perpetuate and sustain disparities in health outcomes, stealing years of healthy and productive life for minority, vulnerable groups. The authors call for implementation of a health equity framework within lifestyle medicine (LM). Community-engaged lifestyle medicine (CELM) is an evidence-based, participatory framework capable of addressing health disparities through LM, targeting health equity in addition to better health. CELM was developed in 2015 by the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley (UTRGV) Preventive Medicine Residency program to address lifestyle-related health disparities within marginalized border communities. The framework includes the following evidence-based principles: community engagement, cultural competency, and application of multilevel and intersectoral approaches. The rationale for each of these components and the growth of CELM within the American College of Lifestyle Medicine is described. Finally, illustrative examples are provided for how CELM can be instituted at micro and macro levels by LM practitioners.

Keywords: community engaged, lifestyle, underserved, health equity

‘Despite overall improvements in life expectancy and quality of health care in the United States, health disparities between certain groups have actually widened.’

Background

Lifestyle is the most fundamental and modifiable influence on risk of disease. Lifestyle risk factors, including tobacco and alcohol use, poor nutrition, and inactivity, comprise the leading actual causes of death.1 Today, 65% of the world’s population lives in a country where overweight and obesity kill more people than underweight and malnutrition.2 The 6 leading global risks for mortality, common to low-, middle-, and high-income countries, include high blood pressure, tobacco use, high blood glucose, inadequate physical activity, overweight, and obesity2. 70% to 90% of the most common and deadly chronic diseases, including diabetes, coronary artery disease, stroke, and cancer, could be prevented via tobacco cessation, avoidance of overweight, moderate physical activity, and a healthy diet.3

The Need for Health Equity–Oriented Lifestyle Medicine

Worldwide, lifestyle risk factors disproportionately affect diverse, lower-income, and vulnerable populations.2 These adverse lifestyle exposures—fundamentally influenced by social determinants of health such as poverty, built environment, education, and food access—systematically perpetuate and sustain pervasive disparities in health outcomes, stealing years of healthy and productive life for minority, vulnerable groups.4

Based on preventable and “unnatural” causes, lifestyle-related health disparities are unjust.5,6 The United States has some of the largest health inequities in the developed world, occurring by ethnicity, geography, and socioeconomic status.7,8 On average, black men and women die 6.3 and 4.5 years earlier than their white counterparts.9 One 2006 study illustrated that men and women in the best-off groups in the United States lived almost a decade and half longer (15.4 and 12.8 years, respectively) than worst-off groups; the persistent race-based gap in life expectancy had not narrowed significantly since 1987.10 Despite overall improvements in life expectancy and quality of health care in the United States, health disparities between certain groups have actually widened.11 Mortality rates for Native Americans are almost 50% higher than that for Caucasians; Native Americans are twice as likely to have diabetes, are twice as likely to have posttraumatic stress disorder, and are more likely to die from diabetes and heart disease.12 Compared with Caucasians, Hispanic Americans are 63% more likely to have diabetes and 30% more likely to die from the disease.13,14 Preventable and modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and blood pressure drive these differences in health. Indeed, researchers calculated that if levels of blood pressure, blood sugar, body fat, and smoking were controlled to optimal levels in vulnerable subgroups, disparities in cardiovascular disease deaths would be eliminated by 80%.9 Preventable health disparities are a threat to economic sustainability and affect the well-being of all residents; one estimate suggests that US health disparities cost more than $1.24 trillion.15

Although proven to treat, prevent, and reverse lifestyle-related chronic disease and its precursors, narrow lifestyle medicine (LM) prevention efforts could inadvertently widen health disparities, especially if least-accessible populations (those at highest risk of disease) are missed.16,17 This phenomenon occurred with cardiovascular disease prevention efforts in the United States: over the past several decades, mean serum cholesterol and prevalence of tobacco use dropped most in high-income groups, whereas prevalence of certain chronic diseases and lifestyle risk factors actually increased in lower-income groups.18,19

Community-Engaged Lifestyle Medicine (CELM) as a Health Equity Pathway

Health equity is defined as the “principle underlying a commitment to reduce—and ultimately, eliminate disparities in health and in its determinants, including social determinants.”20 Building health equity is a goal that is within scope, reach, and mission of LM health care reform and can be achieved through momentum of an organized and collective, rather than ad hoc and individual, approach. Evidence suggests that organized, multilevel and tailored disease prevention efforts targeting health equity are feasible on local, national, and global levels and can successfully narrow disparities in diverse groups around the world.13,14

CELM is defined as the practice of preventing chronic disease and promoting healthy lifestyle behaviors via collaborative, multistakeholder, and community-engaged delivery of LM in diverse, low-income populations.21 Originally developed at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley (UTRGV, Edinburg, Texas) in 2016, under the primary author’s leadership of the Preventive Medicine Residency Program and collaboration with public, private, and community stakeholders, CELM is an evidence-based framework for promoting health equity in low-resource settings. In the Rio Grande Valley, CELM informed a community-driven effort for lifestyle improvement that engaged some of the most historically marginalized, impoverished border communities in the United States.21 In this region of approximately 1.3 million, 35% of the population lives in poverty, compared with 17% at the national level; more than one-third are ineligible for health insurance.22-25 Nearly half the population (45%) is obese, and more than a quarter (22%) have diabetes.23 The specific CELM objectives (grouped into the themes of Engagement, Evaluation, and Education) and the collaborative development and evaluation process for the CELM framework are described in detail elsewhere.21

Evidence-based pathways to health equity feature 2 broad themes. The first, capacity-building partnerships, is a form of community activism that can ameliorate social determinants of poverty, food deserts, and community safety over time, through tenacious intersectoral partnerships operating at local, state, and federal levels and including representatives of vulnerable groups. The second theme engages health care providers to broaden health care impact by building health outside the hospital: engaging and empowering historically marginalized groups to reduce and eliminate lifestyle risk factors for common chronic diseases through culturally tailored LM outreach in clinical and community settings. Addressing the first theme comprehensively is often outside the scope of work for many LM practitioners. Indeed, one of the limitations of CELM is its inability to target the deeper societal power dynamics and structural discrimination that instigate and sustain pervasive disparities. Nonetheless, the CELM approach can help LM practitioners begin building the long-term health equity partnership infrastructure and momentum needed to address deeper social inequities, via engagement of diverse populations and expanding the reach of LM beyond the clinic walls.21

The specific principles of CELM have evidence-based associations with health equity and include community engagement (CE), multilevel and intersectoral approaches, and cultural responsiveness. CE refers to partnership and involvement of marginalized community members and stakeholders along all stages of health interventions (identifying priorities and needs, designing and delivering the intervention, and analysis and dissemination of results). By partnering respectfully with the community of interest, CE supports the creation of culturally tailored programs and can add meaningful value in furthering desired health outcomes.26,27 Multilevel approaches to changing lifestyle address the interconnected influences of levels of individual, peer/family group, health care team, neighborhood resources, and cultural context and, therefore, increase the likelihood that patients can sustain behavior changes outside the health care setting.28,29 Intersectoral partnerships, which refers to the coordination of clinical services with participation and resources drawn from the social, political, environmental, and economic sectors, build sustainability, momentum, and capacity for community-driven LM.30 Finally, cultural responsiveness is a crucial element of provider training and philosophy, enabling the delivery of tailored services that are “respectful of and responsive to the health beliefs, practices, and cultural needs of diverse patients.”31 Table 1 summarizes these principles, along with examples of general LM applications and those within the UTRGV Preventive Medicine residency program.

Table 1.

Health Equity Principles of Community-Engaged Lifestyle Medicine and Associated Practice Applications Within LM and the UTRGV Preventive Medicine Residency.

| Health Equity Principle | Key Principle | Example of LM Application | Example of LM Application: UTRGV Preventive Medicine Program |

|---|---|---|---|

| Community engagement | Partnership and engagement of at-risk community members and relevant stakeholders in health intervention | Training health coaches and peer advocates from vulnerable, at-risk communities | Engaging multistakeholder focus groups to inform health program planning and priorities; hiring 2 promotoras (community health workers) on clinic staff to engage, recruit, and communicate with patients between visits |

| Multilevel approaches | Build/sustain healthy behaviors by addressing multiple levels of influence: individual, family, social linkages, neighborhood, culture | Home, community, and group LM visits that engage patients and families in shared approaches to behavior change; leading community workshops in vulnerable neighborhoods | Holding lifestyle medicine educational sessions and classes in the region’s largest grocery store |

| Intersectoral approaches | Coordinate clinical services with resources and involvement of non–health care sectors (public, private, economic, social) | Partner with local public health department to understand local epidemiology of chronic preventable diseases and offer coordinated approaches to lifestyle-based change | Partnership with local school board to engage middle and high school students in developing community lifestyle change programs |

| Cultural responsiveness | Receptiveness and awareness of patient’s beliefs, practices, and social context; tailoring of care and recommendations to patient context | Inquire about patient culture, context, and practices during clinical encounter; multilingual and multiethnic educational and promotional material; offering LM prescriptions tailored to patient (eg, zumba, ethnic foods) | Hold multistakeholder training in cultural responsiveness led by experts from State Capitol; offer all material in Spanish and English; engaging local faith-based groups to inform care |

Abbreviation: LM, lifestyle medicine.

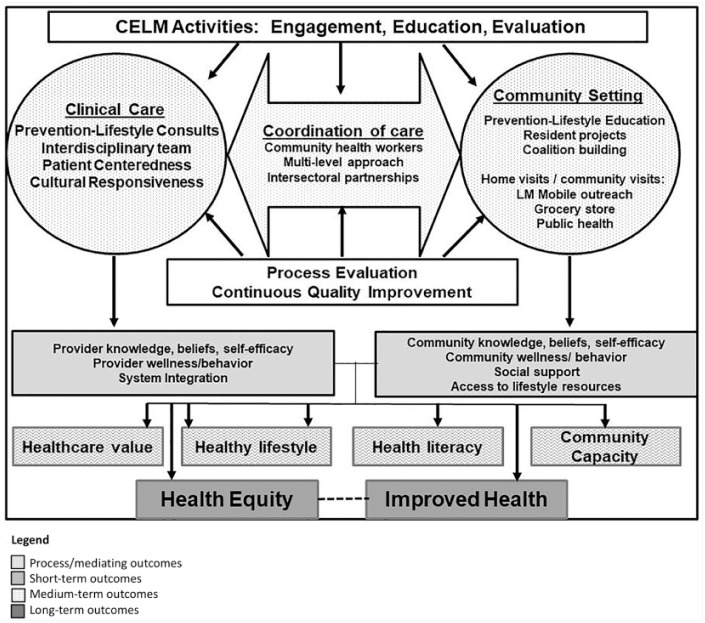

Figure 1 illustrates the CELM logic model, highlighting the role of coordinated, community-clinic linkages and the emphasis on quality improvement and continuous evaluation.

Figure 1.

Logic model for CELMa (reprinted with permission from the author).

Abbreviations: CELM, community-engaged lifestyle medicine; LM, lifestyle medicine.

aKrishnaswami et al.21

CELM Efforts Within the American College of Lifestyle Medicine

When a small group of ACLM members were approached in 2017 with the idea of starting a new committee focused on bringing lifestyle medicine to the underserved, the response was overwhelmingly supportive. The leadership and expertise of the initial members along with the enthusiasm of new members has helped this committee grow. The CELM committee is dedicated to highlighting the extraordinary work that many ACLM members are already doing within underserved populations, providing a space to learn from each other’s challenges and triumphs and holding educational workshops to provide ACLM members with the evidence-based tools necessary to enterprise lifestyle medicine–rooted initiatives within those disadvantaged communities.

This young committee was invited to hold a workshop focusing on CELM for the 2018 ACLM national conference. A portion of the workshop focused on highlighting innovative speakers who were implementing successful CELM-based work both across the country and internationally. An important goal of the workshop was to provide those who attended with a practical step-by-step framework as presented by the Centers for Disease Control, which they could use to guide their very own CELM-focused projects. Session attendees were also given the opportunity to ask questions and collaborate with each other during small group sessions while the expert speakers served as a resource to answer questions and share constructive advice. CELM activities presented by the committee during the inaugural workshop are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

CELM Inaugural Workshop at American College of Lifestyle Medicine 2018: Presenters and Activities.

| Presenter | Location/Institution | Summary of CELM Activity |

|---|---|---|

| Janani Krishnaswami, MD | UTRGV, Texas | UTRGV Preventive Medicine Residency Program: establishing the CELM movement in the border communities of the RGV; creating a multistakeholder partnership with the region’s largest grocery store chain; helping launch the first Lifestyle Medicine—Family Planning mobile clinic for women’s health; starting the first LM practice in a free clinic for 100% uninsured patients |

| Shipra Bansal, MD | Flagstaff, Arizona | “Eating for Life”: based at a federally qualified health clinic, this innovative, cost-effective program aims to encourage and sustain healthy dietary changes among the low-resource, diverse patient population it serves. This program utilized structured group visits, food demonstrations and group meals where costs are kept minimal (<$3/meal), grocery store tours, and sessions focused on goal setting to empower its participants to remain healthy for a lifetime |

| Cheryl True, MD | Davenport, Iowa | This Walk with a Doc chapter utilized a unique twist to tackle the current rise in overweight and obesity in Iowa. Dr True held sessions in partnership with a local veterinarian to create engaging, community-based opportunities for both humans and their animal counterparts to improve their physical activity and reduce their risks of developing chronic medical illnesses simultaneously |

| Blecenda Varona, DrPH, RND, MPH | Philippines | Dr Varona, a licensed nutritionist-dietician and founder of the Asian Institute of Lifestyle Medicine has created and implemented several culturally relevant comprehensive lifestyle medicine programs that incorporate the 6 pillars of lifestyle medicine. These series of measures target the rural, low-income populations of the Philippines who are disproportionately at risk for heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, and obesity. These programs include educational workshops, food demonstrations, and counseling |

Abbreviations: CELM, community-engaged lifestyle medicine; LM, lifestyle medicine.

Prescriptions for Lifestyle Medicine Practitioners: What to Do Today

Although originally developed as a health equity framework for the border communities of the Rio Grande Valley in Texas, CELM can be translated by clinical providers around the world for the betterment and welfare of diverse, vulnerable, and unhealthy communities. Examples of how to build CELM into existing practices in the short- and long-term levels are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

CELM Prescriptions for Lifestyle Medicine Practitioners Based on Short-, Medium-, and Long-Term Outcomes.

| CELM Theme | Short-Term Practice Enhancement | Medium-Term Practice Enhancement | Long-Term Practice Enhancement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Community engagement | • Organize focus groups in partnership with community

organizations to set LM priorities for the community and

identify issues facing vulnerable groups in your

community • Engage diverse patients in the clinic visit (eg, motivational interviewing, patient-centered care); learn from your patients the key community-level barriers for healthy lifestyle and develop shared strategies for addressing barriers |

• Convene a community advisory board that includes diverse

representation from public, private, health care, economic, and

social sectors as well as patients • Work with board and members of a vulnerable community to develop a lifestyle medicine outreach and engagement strategy • Identify opportunities in your LM programming to engage non–health care stakeholders—for example, high school students, volunteers, patient advocate (eg, social media campaigns, data evaluation, anthropometric measurements) |

• Create job opportunities in the clinic for marginalized

communities (lay health worker, patient advocate, coach

training) • Recruit patients from diverse groups who have successfully achieved LM change to serve as volunteers or trained/paid coaches to motivate and engage peers in clinical and community settings • Hold regular community town halls and community advisory board meetings to share knowledge, success stories, and collectively troubleshoot areas for improvement |

| Intersectoral partnerships | • Identify key stakeholders—for example, patients,

administrators, food pantries, church group, YMCA

representative, and so on—who could help inform and broaden the

health-equity focus of your practice • Become a community citizen: identify coalitions, power agents, and nonprofit groups already in place; consider serving on local boards and pitching your work to health-oriented groups in the community to build networks, credibility, and visibility |

• Strengthen partnerships with entities such as local grocery stores, local schools, and policymakers to enable programs such as grocery store tours, food pharmacies, media messaging, and advertising | • Create processes in partnership with local health professions

and medical residency programs, including social workers,

engaging a regular stream of students and volunteers to expand

and sustain outreach efforts • Create strong networks with local mayor and congressional representatives to present community data, pushing for needed built environment changes such as bike trails and farmers’ markets |

| Multilevel approaches | • Begin holding group and family lifestyle medicine

visits • Identify the most common places where vulnerable patients eat, work, and move; develop strategies to organize educational workshops or community events at these locations |

• Create a map of community-level resources supporting lifestyle

medicine that can help patients navigate healthier

choices • Hold community potlucks in partnership with local YMCA or churches featuring healthy, plant-based foods |

• Utilize technology, via processes such as text-message systems or app-based platforms, to engage groups of patients outside the clinic in healthy living practices |

| Cultural responsiveness | • Learn about your patient’s culture and values during the

clinical encounter; acknowledge and link the care provided to

those values • Respect the cultural practices that inform a patient’s dietary practices; refrain from “extremist” dietary advice that is misaligned with a patient’s culture; be able to meet patients halfway • Ask patients from diverse groups for advice on how to reach and connect with more patients in need of lifestyle medicine |

• Arrange local lay health worker or promotora

groups to hold cultural competency trainings for clinical

staff • Survey patients on their perception of respect, bias, and tolerance perceived in your practice • Research and provide recipes and activity advice that include culturally tailored foods, flavors, and spices |

• Employ a community health worker or health coach representing

diverse/vulnerable communities to work with your staff and

patients • Hire diverse staff and health care providers, who represent vulnerable communities, to promote comfort and trust in patients |

Abbreviations: CELM, community-engaged lifestyle medicine; LM, lifestyle medicine.

In line with CE principles, achieving outcomes of health equity must ultimately extend beyond a single clinic’s efforts. Sustainable partnerships boosting capacity of lifestyle medicine practitioners and community-based organizations at the national, regional, and local levels are needed, engaging stakeholders to address upstream causes of poverty and increasing grassroots community momentum and ownership of health-building programs. Nevertheless, systemic transformation can begin via innovation at the ground level: translating theoretically effective CELM mechanisms to build equitable and efficacious pathways for health.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: This article is based on a workshop given at the Annual Meeting of the American College of Lifestyle Medicine 2018 in Indiana, IN. Janani Krishnaswami, MD, MPH, lead author of “Community Engaged Lifestyle Medicine: Building Health Equity Through Preventive Medicine Residency Training,” gives permission for the publication of Figure 1, originally published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine (2018). Janani Krishnaswami is currently affiliated with UWorld LLC, Irving TX.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Informed Consent: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Trial Registration: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any clinical trials.

References

- 1. Mokdad AH. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291:1238. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization. Global health risks. https://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/GlobalHealthRisks_report_part2.pdf. Accessed March 2, 2019.

- 3. Willett WC, Koplan JP, Nugent R, Dusenbury C, Puska P, Gaziano TA. Prevention of chronic disease by means of diet and lifestyle changes. In: Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, et al. , eds. Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: International Bank for Reconstruction and Development; 2006:chap 44. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11795/. Accessed March 13, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. A Framework for Educating Health Professionals to Address the Social Determinants of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Unnatural Causes. About the series—episode descriptions. https://www.unnaturalcauses.org/episode_descriptions.php. Accessed March 2, 2019.

- 6. Harrington NG. Health Disparities, a Social Determinant of Health and Risk: Considerations for Health and Risk Messaging. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2017. doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.222 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hero JO, Zaslavsky AM, Blendon RJ. The United States leads other nations in differences by income in perceptions of health and health care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36:1032-1040. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Division of priority populations. http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/factsheets/priority-populations/index.html. Accessed March 2, 2019.

- 9. Danaei G, Rimm EB, Oza S, Kulkarni SC, Murray CJ, Ezzati M. The promise of prevention: the effects of four preventable risk factors on national life expectancy and life expectancy disparities by race and county in the United States. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000248. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Murray CJ, Kulkarni SC, Michaud C, et al. Eight Americas: investigating mortality disparities across races, counties, and race-counties in the United States. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Institute of Medicine. How Far Have We Come in Reducing Health Disparities? Progress Since 2000: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2012. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK100492/. Accessed March 13, 2019. doi: 10.17226/13383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Committee on Community-Based Solutions to Promote Health Equity in the United States. The state of health disparities in the United States. In: Baciu A, Negussie Y, Geller A, et al. , eds. Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2017:chap 2. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK425844/. Accessed March 13, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015-2016. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db288.pdf. Accessed March 13, 2019. NCHS data brief, no 288. [PubMed]

- 14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes statistics report, 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf. Accessed March 13, 2019.

- 15. Graham G. Disparities in cardiovascular disease risk in the United States. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2015;11:238-245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Riley R, Coghill N, Montgomery A, Feder G, Horwood J. Experiences of patients and healthcare professionals of NHS cardiovascular health checks: a qualitative study. J Public Health (Oxf). 2016;38:543-551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Capewell S, Graham H. Will cardiovascular disease prevention widen health inequalities? PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000320. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kanjilal S, Gregg EW, Cheng YJ, et al. Socioeconomic status and trends in disparities in 4 major risk factors for cardiovascular disease among US adults, 1971-2002. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2348-2355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Oldroyd J, Burns C, Lucas P, Haikerwal A, Waters E. The effectiveness of nutrition interventions on dietary outcomes by relative social disadvantage: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62:573-579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Braveman P. What are health disparities and health equity? We need to be clear. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(suppl 2):5-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Krishnaswami J, Jaini P, Howard RA, Ghaddar S. Community-engaged lifestyle medicine: building health equity through preventive medicine residency training. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55:412-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. US Census Bureau, Population Division. Annual estimates of the resident population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2014. https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk. Accessed March 2, 2019.

- 23. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. US County Profiles. Seattle, WA: IHME; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24. US Census Bureau. Small Area Health Insurance Estimates (SAHIE) program. http://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/sahie.html. Accessed March 2, 2019.

- 25. Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Health Workforce. Area Health Resource Files, 2015-2016. Rockville, MD: HRSA; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wallerstein N, Duran B. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(suppl 1):S40-S46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Krishnaswami J, Martinson M, Wakimoto P, Anglemeyer A. Community-engaged interventions on diet, activity and weight outcomes in US schools: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43:81-91. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.02.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Frieden TR. A framework for public health action: the health impact pyramid. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:590-595. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.185652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Peek ME, Cargil A, Huang ES. Diabetes health disparities: a systematic review of health care interventions. Med Care Res Rev. 2007;64(5, suppl):101S-156S. doi: 10.1177/1077558707305409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. World Health Organization. Centre for Health Development. https://extranet.who.int/kobe_centre/en. Accessed March 2, 2019.

- 31. Saha S, Beach MC, Cooper LA. Patient centeredness, cultural competence/responsiveness, and healthcare quality. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100:1275-1285. doi: 10.1016/S0027-9684(15)31505-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]