Abstract

Breast cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-associated mortality among women worldwide, and the prevalence and mortality rates associated with this disease are high in Western countries. The melanoma-associated antigen (MAGE) family proteins are well-known tumor-specific antigens; this family includes >60 proteins that serve an important part in cell cycle withdrawal, neuronal differentiation and apoptosis. The aim of the present study was to identify a biomarker within the MAGE family that is specific for breast cancer. In the present study, the prognostic role of MAGE mRNA expression was investigated in patients with breast cancer using the Kaplan-Meier plotter database. The prognostic value of MAGE members in the different intrinsic subtypes of breast cancer was further investigated, as well as the clinicopathological features of the disease. The results of the present study indicated that patients with breast cancer that had high mRNA expression levels of MAGEA5, MAGEA8, MAGEB4 and MAGEB6 had an improved relapse-free survival, whereas those with high mRNA expression levels of MAGEB18 and MAGED4 did not. These results suggested that MAGEA5, MAGEA8, MAGEB4 and MAGEB6 may have roles as tumor suppressors in the occurrence and development of breast cancer, whereas MAGEB18 and MAGED4 may possess carcinogenic potential. MAGED2, MAGED3 and MAGEF1 had different effects depending on the type of breast cancer. In particular, high MAGEC3 mRNA expression was associated with worse RFS in lymph node-positive breast cancer, but with improved RFS in lymph node-negative breast cancer. In patients with wild-type TP53 and patients with different pathological grades of breast cancer, MAGEE2, MAGEH1 and MAGEL2 were more worthy of attention as potential prognostic factors. The results of the present study may help to elucidate the role of MAGE family members in the development of breast cancer, and may promote further research that identifies MAGE-targeting reagents for the treatment of breast cancer.

Keywords: breast cancer, melanoma-associated antigen gene family, intrinsic subtypes of breast cancer, clinicopathological features of breast cancer

Introduction

Breast cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-associated mortality among women worldwide (1). According to one published report, there were >240,000 new cases of breast cancer reported in the United States in 2017, of which >40,000 were expected to succumb to the disease (2). Distant metastasis and chemoresistance are leading causes of patient mortality and treatment failure (3). Despite advances in the screening, diagnosis and treatment options for breast cancer, the incidence and mortality of the disease are still increasing (4). Tumor recurrence and metastatic relapse remain the major contributing factors to the high mortality rates (5). Therefore, there is still an urgent need to investigate novel targets and/or biomarkers that can be used to predict or treat patients with breast cancer.

Melanoma-associated antigen (MAGE) family members are cancer/testis antigens that are expressed in germline cells, trophoblasts and various types of human cancer, including melanoma, lung cancer, breast cancer, oral squamous cell carcinoma, esophageal carcinoma, urothelial malignancies and hematopoietic malignancies (6–11). At present, >60 proteins in this family have been identified and subdivided into two categories on the basis of the location and expression patterns of the protein. The type I MAGE genes are restricted to clusters on the X-chromosome, and include MAGE-A, -B and -C. Their aberrant expression levels occur in numerous types of cancer and they serve as tumor-specific antigens (11,12). Unlike the type I genes, type II MAGE genes are not limited to chromosome clustering and include MAGE-D, -E, -F, -G, -H, -I, -J, -K, -L and necdin subfamilies (11,12). They serve an important role in cell cycle withdrawal, neuronal differentiation and apoptosis (13).

It has been reported that MAGEA1 can inhibit the proliferation and migration of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell lines (14). In addition, MAGEA1-A3 and A12 have been investigated in the early detection of breast cancer (15). Ayyoub et al (16) reported that MAGEA3 and MAGEA6 expression in primary breast cancer is associated with hormone receptor-negative status, high histological grade and poor survival. Cabezón et al (17) indicated that MAGEA3 and MAGEA4 may be associated with risk and the clinicopathological parameters of breast cancer (17,18). In breast cancer, MAGEA9-A11 have been identified as being associated with poor prognosis (19–23). Sypniewska et al (24,25) demonstrated that MAGEB1-B3 DNA vaccines are useful for breast cancer therapy in a mouse breast tumor model. Hou et al (26) reported that MAGEC1 and MAGEC2 may be potential targets for tumor immunotherapy, and demonstrated that MAGEC1 and MAGEC2 expression is associated with advanced stages of breast cancer and poor patient outcome. Du et al (27) demonstrated that MAGED1 inhibits the proliferation, migration and invasion of human breast cancer cells. However, the prognostic roles of each individual MAGE, particularly at the mRNA level in breast cancer, remain unknown.

The Kaplan-Meier plotter (KM-Plotter) database (http://kmplot.com/analysis/) is generated gene expression data and survival information of 1,809 patients downloading from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) (28). This database has been widely used to analyze the clinical impact of individual genes on relapse-free survival (RFS), distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS), overall survival (OS) and post-progression survival (PPS) for different types of cancer. In the present study, the prognostic role of the mRNA expression of each individual member of the MAGE family in breast cancer was assessed using the Kaplan-Meier plotter database.

Materials and methods

Data collection

The KM-Plotter database contains data regarding the survival of 3,955 patients with breast cancer (RFS data) (28). The association between the mRNA expression levels of individual MAGE family member genes and RFS was analyzed using an online KM-Plotter database using the gene expression data and the survival information of patients with breast cancer downloaded from the GEO (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20020197) (28). Cohorts of patients were split by median expression values through auto select best cut-off. A collection of clinical data, including estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) status, lymph node status, tumor pathological grade (29), intrinsic subtype and TP53 status were collected.

Different subtypes of breast cancer analysis by KM-Plotter

Briefly, 29 individual members of the MAGE family were entered into the database (kmplot.com/analysis/index.php?p=service&start=1) to obtain Kaplan-Meier survival plots. Of the 29 individual members of the MAGE family, 14 were selected to focus on: MAGEA5, -A8, -B4, -B6, -B18, -C3, -D2, -D3, -D4, -E1, -E2, -F1, -H1 and -L2, which, to the best of our knowledge, have not been reported in the literature by searching PubMed (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/), Elsevier ScienceDirect (http://www.sciencedirect.com/) and Google Scholar (https://scholar.google.com/). Subsequently, they were used to analyze the different subtypes of breast cancer by KM-Plotter.

Clinicopathological features of breast cancer by KM-Plotter

In addition, in order to further examine the clinicopathological survival condition 14 genes were studied. The clinicopathological features of breast cancer through the KM-Plotter, including the lymph node status, tumor grade, TP53 status and Pietenpol subtype (30) were examined.

Statistical analysis

The Kaplan-Meier survival plots with number at risk, hazard ratio (HR), 95% confidence intervals (CI) and log-rank P-values were obtained using the Kaplan-Meier plotter website. According to American Psychological Association (APA) formatting for P-values, P<0.05 was used indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

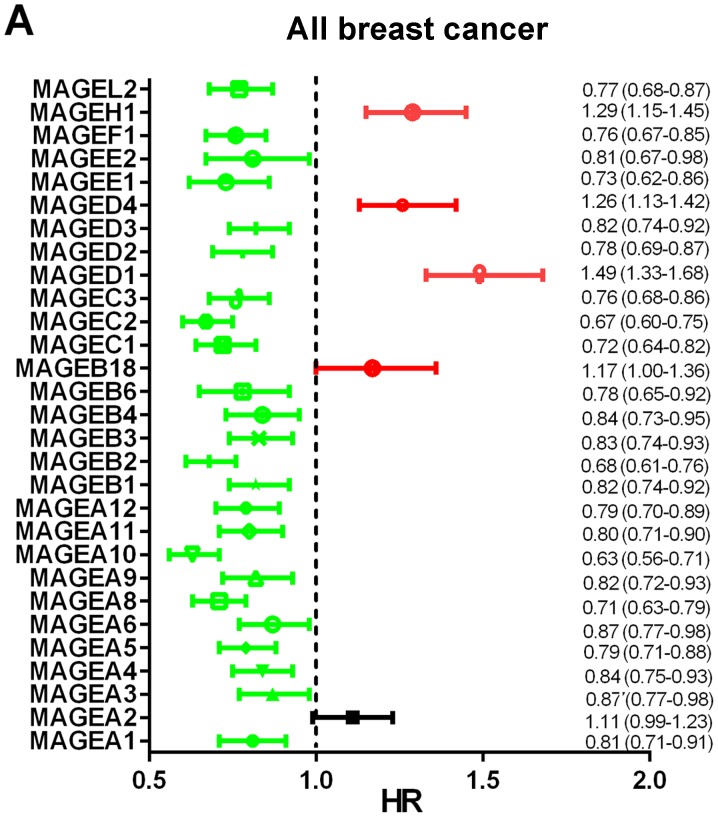

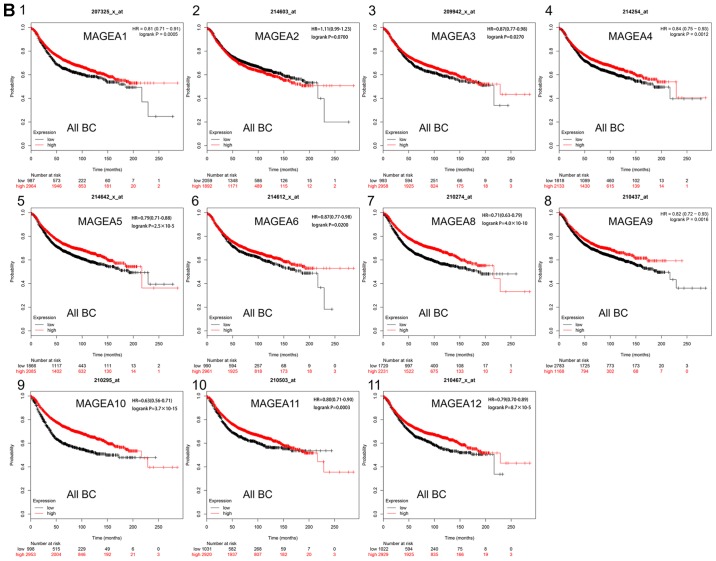

Prognostic values of MAGE members in all patients with breast cancer

The prognostic values of the mRNA expression levels of 29 MAGE family members in patients with breast cancer were obtained from the Kaplan-Meier plotter website. Among these 29 MAGE members, 28 were significantly associated with the prognosis of all types of breast cancer (Fig. 1A). High mRNA expression levels of MAGEA1 (HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.71–0.91; P=0.0005), MAGEA4 (HR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.75–0.93; P=0.0012), MAGEA5 (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.71–0.88; P=2.5×10−5), MAGEA6 (HR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.77–0.98; P=0.0200), MAGEA8 (HR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.63–0.79; P=4.0×10−10), MAGEA9 (HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.72–0.93; P=0.0016), MAGEA10 (HR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.56–0.71; P=3.7×10−15), MAGEA11 (HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.71–0.90; P=0.0003), MAGEA12 (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.70–0.89; P=8.7×10−5) (Fig. 1B-1/4/5/6/8/9/10/11); MAGEB1 (HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.74–0.92; P=0.0005), MAGEB2 (HR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.61–0.76; P=6.8×10−12), MAGEB3 (HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.74–0.93; P=0.0017), MAGEB4 (HR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.73–0.95; P=0.0058), MAGEB6 (HR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.65–0.92; P=0.0031), MAGEC1 (HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.64–0.82; P=2.2×10−7), MAGEC2 (HR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.60–0.75; P=6.7×10−13), MAGEC3 (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.68–0.86; P=7.5×10−6), MAGED2 (HR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.69–0.87; P=3.1×10−5), MAGED3 (HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.74–0.92; P=0.0009), MAGEE1 (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.62–0.86; P=8.7×10−5), MAGEF1 (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.67–0.85; P=4.2×10−6) and MAGEL2 (HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.68–0.87; P=4.3×10−5) (Fig. 1C-1/2/3/4/5/7/8/9/11/12/14/16/18) were observed to be significantly associated with better prognosis. High mRNA expression levels of MAGED1 (HR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.33–1.68; P=8.1×10−12), MAGED4 (HR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.13–1.42; P=6.6×10−5) and MAGEH1 (HR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.15–1.45; P=1.7×10−5) (Fig. 1C-10/13/17) were significantly associated with worse RFS, whereas the expression levels of MAGEA2 (HR, 1.11; 95% CI, 0.99–1.23; P=0.0700) (Fig. 1B-2) were not associated with RFS. High mRNA expression levels of MAGEA3 (HR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.77–0.98; P=0.0270; Fig. 1B-3) and MAGEE2 (HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.67–0.98; P=0.0290; Fig. 1C-15) were significantly associated with improved prognosis, and low mRNA expression of MAGEB18 (HR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.00–1.36; P=0.0490; Fig. 1C-6) was significantly associated with better prognosis.

Figure 1.

Prognostic value of the mRNA expression levels of the MAGE family members using the Kaplan-Meier plotter database. (A) Prognostic HRs of individual MAGE family members in all types of breast cancer. Red indicates HR≥1, green indicates HR<1 and black indicates HR (0.99–1.23). (B) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of the mRNA expression levels of MAGE family members. 1, MAGEA1; 2, MAGEA2; 3, MAGEA3; 4, MAGEA4; 5, MAGEA5; 6, MAGEA6; 7, MAGEA8; 8, MAGEA9; 9, MAGEA10; 10, MAGEA11; and-11, MAGEA12 for all breast cancer patients (n=3,955). All BC, all breast cancer; HR, hazard ratio; MAGE, melanoma-associated antigen. (C) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of the mRNA expression levels of MAGE family members. 1, MAGEB1; 2, MAGEB2; 3, MAGEB3; 4, MAGEB4; 5, MAGEB6; 6, MAGEB18; 7, MAGEC1; 8, MAGEC2; 9, MAGEC3; 10, MAGED1; 11, MAGED2; 12, MAGED3; 13, MAGED4; 14, MAGEE1; 15, MAGEE2; 16, MAGEF1; 17, MAGEH1; and 18, MAGEL2 for all breast cancer patients (n=3,955). All BC, all breast cancer; HR, hazard ratio; MAGE, melanoma-associated antigen.

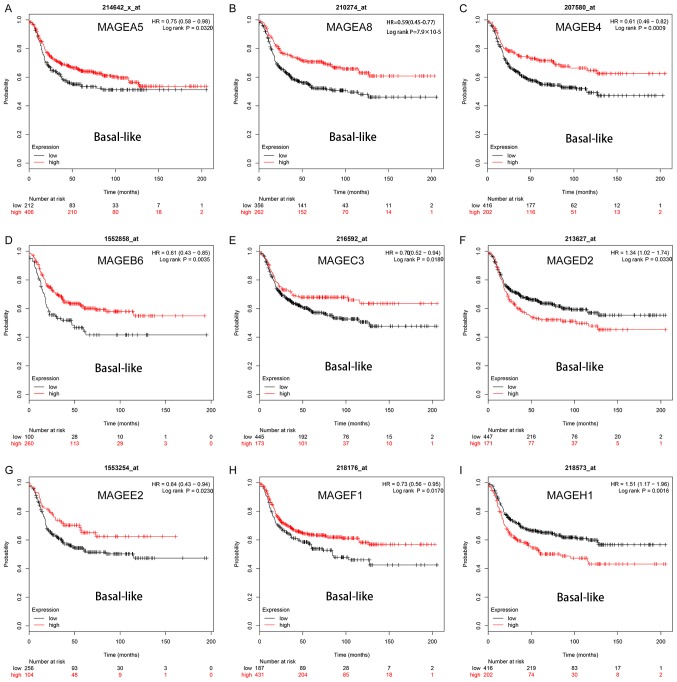

Prognostic value of 14 MAGE members in different subtypes of breast cancer

The prognostic values of 14 MAGE members within the different intrinsic subtypes of breast cancer were determined, including all basal-like, luminal A, luminal B and HER2+. As presented in Fig. 2, high mRNA expression levels of MAGEA8 (HR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.45–0.77; P=7.9×10−5; Fig. 2B), MAGEB4 (HR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.46–0.82; P=0.0009; Fig. 2C) and MAGEB6 (HR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.43–0.85; P=0.0035; Fig. 2D) were significantly associated with improved RFS in patients with the basal-like breast cancer subtype. High mRNA expression levels of MAGEA5 (HR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.58–0.98; P=0.0320; Fig. 2A), MAGEC3 (HR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.52–0.94; P=0.0180; Fig. 2E) MAGEE2 (HR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.43–0.94; P=0.0230; Fig. 2G) and MAGEF1 (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.56–0.95; P=0.0170; Fig. 2H) were significantly associated with improved RFS in patients with basal-like breast cancer subtype. However, high mRNA expression levels of MAGEH1 (HR, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.17–1.96; P=0.0016; Fig. 2I) were significantly associated with worse RFS in patients with the basal-like breast cancer subtype and high mRNA expression levels of MAGED2 (HR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.02–1.74; P=0.0330; Fig. 2F) was significantly associated with improved RFS in patients with basal-like breast cancer subtype. The survival curves for the remaining members of the MAGE family in patients with basal-like breast cancer subtype were investigated, but they were not significantly associated with prognosis (Fig. S1).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of the mRNA expression levels of (A) MAGEA5, (B) MAGEA8, (C) MAGEB4, (D) MAGEB6, (E) MAGEC3, (F) MAGED2, (G) MAGEE2, (H) MAGEF1 and (I) MAGEH1 for patients with basal-like breast cancer subtypes (n=879). HR, hazard ratio; MAGE, melanoma-associated antigen.

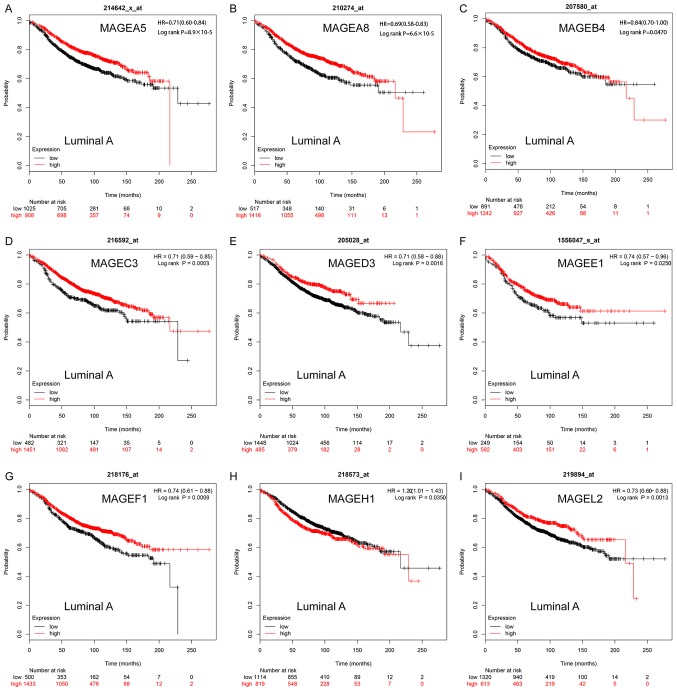

In patients with luminal A breast cancer, high mRNA expression levels of MAGEA5 (HR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.60–0.84; P=8.9×10−5; Fig. 3A), MAGEA8 (HR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.58–0.83; P=6.6×10−5; Fig. 3B), MAGEC3 (HR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.59–0.85, P=0.0003; Fig. 3D); MAGED3 (HR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.58–0.88; P=0.0016; Fig. 3E), MAGEF1 (HR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.61–0.88; P=0.0009; Fig. 3G) and MAGEL2 (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.60–0.88; P=0.0013; Fig. 3I) were significantly associated with improved RFS. In contrast, high mRNA expression levels of MAGEH1 (HR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.01–1.43; P=0.0350; Fig. 3H) were significantly associated with worse RFS. High expression levels of MAGEB4 (HR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.70–1.00; P=0.0470; Fig. 3C) and MAGEE1 (HR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.57–0.96; P=0.0250; Fig. 3F) were significantly associated with improved RFS. The remaining MAGE family members were not significantly associated with the prognosis of luminal A breast cancer (Fig. S2).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of the mRNA expression levels of (A) MAGEA5, (B) MAGEA8, (C) MAGEB4, (D) MAGEC3, (E) MAGED3, (F) MAGEE1, (G) MAGEF1, (H) MAGEH1 and (I) MAGEL2 for patients with the luminal A breast cancer subtype (n=2,504). HR, hazard ratio; MAGE, melanoma-associated antigen.

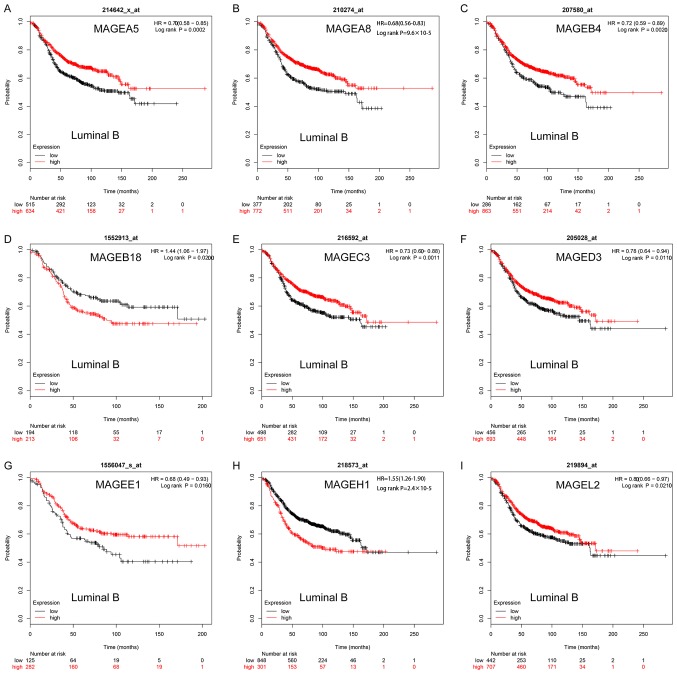

In luminal B breast cancer, high mRNA expression levels of MAGEA5 (HR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.58–0.85; P=0.0002; Fig. 4A), MAGEA8 (HR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.56–0.83; P=9.6×10−5; Fig. 4B), MAGEB4 (HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.59–0.89; P=0.0020; Fig. 4C), MAGEC3 (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.60–0.88; P=0.0011; Fig. 4E), MAGED3 (HR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.64–0.94; P=0.0110; Fig. 4F), MAGEE1 (HR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.49–0.93; P=0.0016; Fig. 4G) was significantly associated with improved RFS. High mRNA expression levels of MAGEL2 (HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.66–0.97; P=0.0210; Fig. 4I) was significantly associated with improved RFS. However, high mRNA expression levels of MAGEH1 (HR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.26–1.90; P=2.4×10−5; Fig. 4H) was significantly associated with worse RFS and high mRNA expression levels of MAGEB18 (HR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.06–1.97; P=0.0200; Fig. 4D) was significantly associated with worse RFS. The remaining MAGE members were not significantly associated with the prognosis of luminal B breast cancer (Fig. S3).

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of the mRNA expression levels of (A) MAGEA5, (B) MAGEA8, (C) MAGEB4, (D) MAGEB18, (E) MAGEC3, (F) MAGED3, (G) MAGEE1, (H) MAGEH1 and (I) MAGEL2 for patients with the luminal B breast cancer subtype (n=1,425). HR, hazard ratio; MAGE, melanoma-associated antigen.

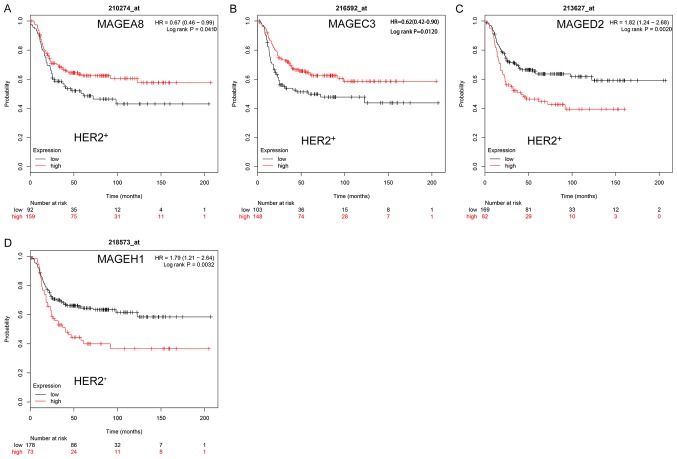

In HER2+ breast cancer, high mRNA expression levels of MAGEA8 (HR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.46–0.99; P=0.0410; Fig. 5A) and MAGEC3 (HR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.42–0.90; P=0.0120; Fig. 5B) were significantly associated with improved RFS. However, high mRNA expression levels of MAGED2 (HR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.24–2.68; P=0.0020; Fig. 5C) and MAGEH1 (HR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.21–2.64; P=0.0032; Fig. 5D) were significantly associated with worse RFS. The remaining MAGE family members were not significantly associated with the RFS of HER2+ breast cancer (Fig. S4).

Figure 5.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of the mRNA expression levels of (A) MAGEA8, (B) MAGEC3, (C) MAGED2 and (D) MAGEH1 for patients with the HER2+ breast cancer subtype (n=335). HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; HR, hazard ratio; MAGE, melanoma-associated antigen.

Prognostic values of 14 MAGE members in breast cancer according to clinicopathological features

The present study also investigated the association between the MAGE family members and patients' clinicopathological features. As presented in Table I, high mRNA expression levels of MAGEF1 (HR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.61–0.93; P=0.0094) were significantly associated with improved RFS in lymph node-positive breast cancer. In contrast, high mRNA expression levels of MAGEF1 (HR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.07–1.50; P=0.0063) were significantly associated with worse RFS in lymph node-negative breast cancer. High mRNA expression levels of MAGED2 were significantly associated with improved RFS in lymph node-positive breast cancer (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.65–0.96; P=0.0200) and lymph node-negative breast cancer (HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.68–0.99; P=0.0400) breast cancer. MAGED4 expression levels were significantly associated with worse prognosis in lymph node-positive breast cancer (HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.02–1.51; P=0.0290) and significantly associated with worse prognosis in lymph node-negative breast cancer (HR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.07–1.51; P=0.0062). High mRNA expression levels of MAGED3 (HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.67–0.99; P=0.0390) were significantly associated with improved RFS in lymph node-positive breast cancer. High mRNA expression levels of MAGEA5 (HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.00–1.53; P=0.0447), MAGED4 (HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.02–1.51; P=0.0290) and MAGEH1 (HR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.04–1.62; P=0.0185) were significantly associated with worse RFS in lymph node-positive breast cancer. However, high mRNA expression levels of MAGEB6 (HR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.33–0.91; P=0.0188), MAGEE2 (HR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.33–0.98; P=0.0376) and MAGEL2 (HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.69–1.00; P=0.0464) were significantly associated with improved RFS in lymph node-negative breast cancer. The remaining MAGE family members were not significantly associated with the RFS of lymph node positive and negative breast cancer.

Table I.

Associations between the different MAGE family members and positive or negative lymph node status of patients with breast cancer.

| MAGE family member | Affymetrix ID | Lymph node status | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAGEA5 | 214642_x_at | Positive | 1.24b | 1.00–1.53b | 0.0447b |

| Negative | 0.90 | 0.76–1.06 | 0.2129 | ||

| MAGEA8 | 210274_at | Positive | 1.22 | 0.99–1.52 | 0.0646 |

| Negative | 0.85 | 0.71–1.03 | 0.0946 | ||

| MAGEB4 | 207580_at | Positive | 1.18 | 0.95–1.48 | 0.1385 |

| Negative | 0.87 | 0.72–1.06 | 0.1809 | ||

| MAGEB6 | 1552858_at | Positive | 0.78 | 0.60–1.00 | 0.0515 |

| Negative | 0.55a | 0.33–0.91a | 0.0188a | ||

| MAGEB18 | 1552913_at | Positive | 0.84 | 0.65–1.09 | 0.1869 |

| Negative | 1.47 | 0.98–2.21 | 0.0601 | ||

| MAGEC3 | 216592_at | Positive | 1.20 | 0.98–1.48 | 0.0810 |

| Negative | 0.85 | 0.71–1.01 | 0.0640 | ||

| MAGED2 | 213627_at | Positive | 0.79a | 0.65–0.96a | 0.0200a |

| Negative | 0.82a | 0.68–0.99a | 0.0400a | ||

| MAGED3 | 205028_at | Positive | 0.81a | 0.67–0.99a | 0.0390a |

| Negative | 1.10 | 0.93–1.30 | 0.2800 | ||

| MAGED4 | 221261_x_at | Positive | 1.24b | 1.02–1.51b | 0.0290b |

| Negative | 1.27b | 1.07–1.51b | 0.0062b | ||

| MAGEE1 | 1556047_s_at | Positive | 0.81 | 0.62–1.04 | 0.1013 |

| Negative | 0.79 | 0.54–1.17 | 0.2400 | ||

| MAGEE2 | 1553254_at | Positive | 1.23 | 0.95–1.58 | 0.1096 |

| Negative | 0.57a | 0.33–0.98a | 0.0376a | ||

| MAGEF1 | 218176_at | Positive | 0.75a | 0.61–0.93a | 0.0094a |

| Negative | 1.26b | 1.07–1.50b | 0.0063b | ||

| MAGEH1 | 218573_at | Positive | 1.30b | 1.04–1.62b | 0.0185b |

| Negative | 0.91 | 0.75–1.11 | 0.3438 | ||

| MAGEL2 | 219894_at | Positive | 1.08 | 0.88–1.31 | 0.4600 |

| Negative | 0.83a | 0.69–1.00a | 0.0464a |

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

High mRNA expression levels associated with improved RFS

high mRNA expression levels associated with worse RFS. Total patients assigned a lymph node status, n=3,718; lymph node-positive patients, n=1,459; lymph node-negative patients, n=2,259, analyzed by ANOVA. CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; MAGE, melanoma-associated antigen; RFS, relapse-free survival.

As presented in Table II, high mRNA expression levels of MAGEB6 (HR, 0.29; 95% CI, 0.10–0.83; P=0.0136), MAGEE1 (HR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.12–1.02; P=0.0435) and MAGEH1 (HR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.30–0.88; P=0.0140) in grade I breast cancer; MAGEA8 (HR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.57–0.96; P=0.0248) and MAGEC3 (HR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.57–0.96; P=0.0210) in grade II breast cancer; and MAGEA8 (HR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.61–0.99; P=0.0373) in grade III breast cancer were significantly associated with improved RFS. High expression levels of MAGEF1 (HR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.54–0.90; P=0.0057) and MAGEH1 (HR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.47–0.85, P=0.0020) in grade II breast cancer; and MAGEB4 (HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.58–0.90; P=0.0041) and MAGEB6 (HR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.46–0.85; P=0.0029) in grade III breast cancer were significantly associated with improved RFS.

Table II.

Association between the MAGE family members and pathological tumor grade of patients with breast cancer.

| MAGE family member | Affymetrix ID | Tumor grade | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAGEA5 | 214642_at | I | 0.72 | 0.43–1.22 | 0.2269 |

| II | 1.27 | 0.95–1.68 | 0.1038 | ||

| III | 1.12 | 0.88–1.43 | 0.3578 | ||

| MAGEA8 | 210274_at | I | 0.63 | 0.33–1.22 | 0.1702 |

| II | 0.74a | 0.57–0.96a | 0.0248a | ||

| III | 0.78a | 0.61–0.99a | 0.0373a | ||

| MAGEB4 | 207580_at | I | 1.91b | 1.06–3.43b | 0.0288b |

| II | 0.79 | 0.60–1.02 | 0.0732 | ||

| III | 0.72a | 0.58–0.90a | 0.0041a | ||

| MAGEB6 | 1552858_at | I | 0.29a | 0.10–0.83a | 0.0136a |

| II | 1.19 | 0.72–1.99 | 0.4982 | ||

| III | 0.62a | 0.46–0.85a | 0.0029a | ||

| MAGEB18 | 1552913_at | I | 3.46b | 1.20–9.98b | 0.0142b |

| II | 1.65 | 0.93–2.93 | 0.0840 | ||

| III | 1.27 | 0.90–1.78 | 0.1706 | ||

| MAGEC3 | 216592_at | I | 1.51 | 0.80–2.85 | 0.2000 |

| II | 0.74a | 0.57–0.96a | 0.0210a | ||

| III | 0.89 | 0.71–1.11 | 0.2900 | ||

| MAGED2 | 213627_at | I | 1.47 | 0.87–2.48 | 0.1500 |

| II | 0.86 | 0.67–1.10 | 0.2200 | ||

| III | 1.39b | 1.11–1.73b | 0.0042b | ||

| MAGED3 | 205028_at | I | 1.64 | 0.95–2.83 | 0.0720 |

| II | 0.79 | 0.62–1.01 | 0.0620 | ||

| III | 1.35b | 1.07–1.69b | 0.0101b | ||

| MAGED4 | 221261_x_at | I | 0.54 | 0.26–1.10 | 0.0827 |

| II | 1.52b | 1.18–1.95b | 0.0009b | ||

| III | 1.20 | 0.97–1.50 | 0.0946 | ||

| MAGEE1 | 1556047_s_at | I | 0.35a | 0.12–1.02a | 0.0435a |

| II | 0.61 | 0.35–1.05 | 0.0730 | ||

| III | 1.53b | 1.12–2.08b | 0.0075b | ||

| MAGEE2 | 1553254_at | I | 0.56 | 0.19–1.67 | 0.2903 |

| II | 1.22 | 0.73–2.04 | 0.4500 | ||

| III | 1.18 | 0.87–1.61 | 0.2900 | ||

| MAGEF1 | 218176_at | I | 0.67 | 0.36–1.24 | 0.1993 |

| II | 0.70a | 0.54–0.90a | 0.0057a | ||

| III | 0.85 | 0.67–1.08 | 0.1788 | ||

| MAGEH1 | 218573_at | I | 0.52a | 0.30–0.88a | 0.0140a |

| II | 0.63a | 0.47–0.85a | 0.0020a | ||

| III | 1.18 | 0.94–1.49 | 0.1600 | ||

| MAGEL2 | 219894_at | I | 0.71 | 0.42–1.19 | 0.1907 |

| II | 0.79 | 0.62–1.00 | 0.0513 | ||

| III | 1.25b | 1.01–1.56b | 0.0420b |

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

High mRNA expression levels associated with improved RFS

high mRNA expression levels associated with worse RFS. Total patients with a pathological tumor grade, n=2,545; patients with tumor grade I, n=378; patients with tumor grade II, n=1,077; patients with tumor grade III, n=1,090 patients. CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; MAGE, melanoma-associated antigen; RFS, relapse-free survival.

High mRNA expression levels of MAGEB4 (HR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.06–3.43; P=0.0288) and MAGEB18 (HR, 3.46; 95% CI, 1.20–9.98; P=0.0142) in grade I breast cancer were significantly associated with worse RFS; high mRNA expression levels of MAGED4 (HR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.18–1.95; P=0.0009) in grade II breast cancer; and MAGED2 (HR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.11–1.73; P=0.0042), MAGED3 (HR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.07–1.69; P=0.0101), MAGEE1 (HR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.12–2.08; P=0.0075) in grade III breast cancer were significantly associated with worse RFS; high mRNA expression levels of MAGEL2 (HR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.01–1.56; P=0.0420) in grade III were significantly associated with worse RFS. The remaining MAGE family members were not associated with the RFS of different grade breast cancer.

As shown in Table III, high mRNA expression levels of MAGEB4 (HR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.31–0.88; P=0.0136) and MAGED3 (HR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.37–0.95; P=0.0280) were significantly associated with improved RFS in patients with TP53-mutated breast cancer, whereas high mRNA expression levels of MAGEL2 (HR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.34–0.99; P=0.0430) were significantly associated with improved RFS in TP53 wild-type breast cancer. In contrast, high mRNA expression levels of MAGED2 (HR, 2.10; 95% CI, 1.28–3.46; P=0.0028) were significantly associated with worse RFS in TP53-mutated breast cancer. High mRNA expression levels of MAGEB18 (HR, 3.51; 95% CI, 1.50–8.22; P=0.0021) and MAGED4 (HR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.18–2.83; P=0.0065) were significantly associated with worse RFS in TP53 wild-type breast cancer; and high mRNA expression levels of MAGEE2 (HR, 2.35; 95% CI, 1.01–5.48; P=0.0414), MAGEB6 (HR, 5.08; 95% CI, 1.18–21.89; P=0.0157) were significantly associated with worse RFS in TP53 wild-type breast cancer. Notably, high mRNA expression levels of MAGEF1 were significantly associated with worse RFS in TP53-mutated (HR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.04–2.71; P=0.0318) and TP53 wild-type (HR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.06–2.55; P=0.0240) breast cancer. The remaining MAGE family members were not significantly associated with RFS of TP53 mutated and wild-type breast cancer.

Table III.

Association between MAGE family members and the TP53 status of patients with breast cancer.

| MAGE family member | Affymetrix ID | TP53 status | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAGEA5 | 214642_at | Mutated | 1.38 | 0.81–2.37 | 0.2357 |

| Wild-type | 1.39 | 0.88–2.17 | 0.1236 | ||

| MAGEA8 | 210274_at | Mutated | 0.69 | 0.43–1.12 | 0.1317 |

| Wild-type | 0.80 | 0.50–1.27 | 0.3462 | ||

| MAGEB4 | 207580_at | Mutated | 0.53a | 0.31–0.88a | 0.0136a |

| Wild-type | 0.78 | 0.51–1.20 | 0.2634 | ||

| MAGEB6 | 1552858_at | Mutated | 0.64 | 0.34–1.18 | 0.1506 |

| Wild-type | 5.08b | 1.18–21.89b | 0.0157 | ||

| MAGEB18 | 1552913_at | Mutated | 0.66 | 0.35–1.24 | 0.1931 |

| Wild-type | 3.51b | 1.50–8.22b | 0.0021b | ||

| MAGEC3 | 216592_at | Mutated | 0.75 | 0.46–1.23 | 0.2500 |

| Wild-type | 0.85 | 0.56–1.31 | 0.4700 | ||

| MAGED2 | 213627_at | Mutated | 2.10b | 1.28–3.46b | 0.0028b |

| Wild-type | 0.80 | 0.53–1.23 | 0.3100 | ||

| MAGED3 | 205028_at | Mutated | 0.59a | 0.37–0.95a | 0.0280a |

| Wild-type | 0.74 | 0.45–1.21 | 0.2286 | ||

| MAGED4 | 221261_x_at | Mutated | 0.71 | 0.44–1.14 | 0.1513 |

| Wild-type | 1.82b | 1.18–2.83b | 0.0065b | ||

| MAGEE1 | 1556047_s_at | Mutated | 1.76 | 0.96–3.25 | 0.0660 |

| Wild-type | 0.48 | 0.19–1.23 | 0.1200 | ||

| MAGEE2 | 1553254_at | Mutated | 0.54 | 0.25–1.17 | 0.1138 |

| Wild-type | 2.35b | 1.01–5.48b | 0.0414b | ||

| MAGEF1 | 218176_at | Mutated | 1.68b | 1.04–2.71b | 0.0318b |

| Wild-type | 1.65b | 1.06–2.55b | 0.0240b | ||

| MAGEH1 | 218573_at | Mutated | 1.60 | 0.98–2.64 | 0.0600 |

| Wild-type | 0.67 | 0.44–1.04 | 0.0710 | ||

| MAGEL2 | 219894_at | Mutated | 1.58 | 0.95–2.64 | 0.0777 |

| Wild-type | 0.58a | 0.34–0.99a | 0.0430a |

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

High mRNA expression levels associated with improved RFS

high mRNA expression levels associated with worse RFS. Total patients assigned a TP53 status, n=595; patients with TP53-mutated breast cancer, n=232; patients with wild-type TP53 breast cancer, n=363. CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; MAGE, melanoma-associated antigen; RFS, relapse-free survival.

As presented in Table IV, high mRNA expression levels of MAGEA8 in the basal-like 1 subtype (HR, 0.50; 95% CI, 0.31–0.83; P=0.0059) and luminal androgen receptor subtype (HR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.31–0.85; P=0.0076); and MAGEB18 in mesenchymal stem-like breast cancer subtype (HR, 0.19; 95% CI, 0.05–0.66; P=0.0039) were significantly associated with improved RFS. High expression levels of MAGEA5 in the basal-like 1 subtype (HR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.37–0.96; P=0.0327); MAGEB6 (HR, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.19–0.97; P=0.0356), MAGED2 (HR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.23–0.95; P=0.0308), MAGEE1 (HR, 0.25; 95% CI, 0.07–0.85; P=0.0160), MAGEF1 (HR 0.33; 95% CI, 0.14–0.81; P=0.0110) in the basal-like 2 subtype; MAGEB6 (HR, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.17–0.96; P=0.0333) in the immunomodulatory subtype; MAGEA8 (HR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.38–0.95; P=0.0268), MAGEB6 (HR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.24–0.89; P=0.0181), MAGEL2 (HR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.39–0.99; P=0.0433) in the mesenchymal subtype; MAGEA8 (HR, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.18–0.93; P=0.0280), MAGEC3 (HR, 0.32; 95% CI, 0.12–0.85; P=0.0159), MAGEE2 (HR, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.12–0.97; P=0.0345), MAGEF1 (HR, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.18–0.94; P=0.0292) in the mesenchymal stem-like subtype; and MAGEA5 (HR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.41–0.93; P=0.0195), MAGEB4 (HR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.41–1.00; P=0.0471), MAGEF1 (HR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.41–0.91; P=0.0158) and MAGEL2 (HR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.41–0.93; P=0.0188) in the luminal androgen receptor breast cancer subtype were significantly associated with improved RFS. However, high mRNA expression levels of MAGEH1 (HR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.16–3.02; P=0.0090) in the basal-like 1 subtype; MAGED3 (HR, 2.93; 95% CI, 1.34–6.39; P=0.0047) in the basal-like 2 subtype; MAGEA5 (HR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.17–2.79; P=0.0066) in the mesenchymal subtype; and MAGEH1 (HR, 1.72; 95% CI, 1.15–2.59; P=0.0079) in the luminal androgen receptor breast cancer subtype were significantly associated with worse RFS. High mRNA expression levels of MAGED2 (HR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.02–2.77; P=0.0386), MAGED4 (HR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.00–2.59; P=0.0494) in the basal-like 1 subtype; MAGEB4 (HR, 2.74; 95% CI, 1.22–6.14; P=0.0106) and MAGEH1 (HR, 2.17; 95% CI, 1.06–4.40; P=0.0288) in the basal-like 2 subtype; MAGEB18 (HR, 2.39; 95% CI, 1.03–5.51; P=0.0353) and MAGEH1 (HR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.05–3.42; P=0.0314) in the immunomodulatory subtype; MAGED3 (HR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.04–2.43; P=0.0317), MAGEE1 (HR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.06–3.15; P=0.0284) and MAGEH1 (HR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.01–2.42; P=0.0421) in the mesenchymal subtype; MAGED4 (HR, 3.16; 95% CI, 0.94–10.56; P=0.0488) in the mesenchymal stem-like subtype; and MAGEB18 (HR, 2.04; 95% CI, 1.11–3.77; P=0.0211) and MAGED4 (HR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.05–2.40; P=0.0267) in the luminal androgen receptor breast cancer subtype were significantly associated with worse RFS.

Table IV.

Association between the MAGE family members and different Pietenpol subtypes of patients with breast cancer.

| MAGE family member | Affymetrix ID | Pietenpol subtype | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAGEA5 | 214642_at | Basal-like 1 | 0.60a | 0.37–0.96a | 0.0327a |

| Basal-like 2 | 1.71 | 0.84–3.46 | 0.1324 | ||

| Immunomodulatory | 1.48 | 0.73–2.99 | 0.2723 | ||

| Mesenchymal | 1.81b | 1.17–2.79b | 0.0066b | ||

| Mesenchymal stem-like | 2.62 | 0.78–8.76 | 0.1041 | ||

| Luminal androgen receptor | 0.62a | 0.41–0.93a | 0.0195a | ||

| MAGEA8 | 210274_at | Basal-like 1 | 0.50a | 0.31–0.83a | 0.0059a |

| Basal-like 2 | 1.51 | 0.75–3.06 | 0.2499 | ||

| Immunomodulatory | 1.36 | 0.71–2.61 | 0.3555 | ||

| Mesenchymal | 0.60a | 0.38–0.95a | 0.0268a | ||

| Mesenchymal stem-like | 0.41a | 0.18–0.93a | 0.0280a | ||

| Luminal androgen receptor | 0.52a | 0.31–0.85a | 0.0076a | ||

| MAGEB4 | 207580_at | Basal-like 1 | 0.60 | 0.36–1.02 | 0.0550 |

| Basal-like 2 | 2.74b | 1.22–6.14b | 0.0106b | ||

| Immunomodulatory | 0.66 | 0.36–1.20 | 0.1708 | ||

| Mesenchymal | 0.82 | 0.5–1.33 | 0.4204 | ||

| Mesenchymal stem-like | 0.40 | 0.14–1.16 | 0.0794 | ||

| Luminal androgen receptor | 0.64a | 0.41–1.00a | 0.0471a | ||

| MAGEB6 | 1552858_at | Basal-like 1 | 0.64 | 0.31–1.33 | 0.2293 |

| Basal-like 2 | 0.43a | 0.19–0.97a | 0.0356a | ||

| Immunomodulatory | 0.41a | 0.17–0.96a | 0.0333a | ||

| Mesenchymal | 0.47a | 0.24–0.89a | 0.0181a | ||

| Mesenchymal stem-like | 0.54 | 0.17–1.72 | 0.2907 | ||

| Luminal androgen receptor | 0.58 | 0.33–1.02 | 0.0546 | ||

| MAGEB18 | 1552913_at | Basal-like 1 | 1.75 | 0.90–3.40 | 0.0922 |

| Basal-like 2 | 0.51 | 0.22–1.18 | 0.1092 | ||

| Immunomodulatory | 2.39b | 1.03–5.51b | 0.0353b | ||

| Mesenchymal | 1.70 | 0.98–2.93 | 0.0543 | ||

| Mesenchymal stem-like | 0.19a | 0.05–0.66a | 0.0039a | ||

| Luminal androgen receptor | 2.04b | 1.11–3.77b | 0.0211b | ||

| MAGEC3 | 216592_at | Basal-like 1 | 0.63 | 0.35–1.14 | 0.1255 |

| Basal-like 2 | 0.55 | 0.27–1.12 | 0.0933 | ||

| Immunomodulatory | 0.69 | 0.35–1.37 | 0.2890 | ||

| Mesenchymal | 0.65 | 0.43–1.00 | 0.0505 | ||

| Mesenchymal stem-like | 0.32a | 0.12–0.85a | 0.0159a | ||

| Luminal androgen receptor | 0.73 | 0.47–1.12 | 0.1508 | ||

| MAGED2 | 213627_at | Basal-like 1 | 1.68b | 1.02–2.77b | 0.0386b |

| Basal-like 2 | 0.46a | 0.23–0.95a | 0.0308a | ||

| Immunomodulatory | 1.34 | 0.72–2.49 | 0.3553 | ||

| Mesenchymal | 1.43 | 0.83–2.46 | 0.1993 | ||

| Mesenchymal stem-like | 0.60 | 0.27–1.32 | 0.2002 | ||

| Luminal androgen receptor | 1.32 | 0.86–2.02 | 0.2000 | ||

| MAGED3 | 205028_at | Basal-like 1 | 0.74 | 0.43–1.25 | 0.2584 |

| Basal-like 2 | 2.93b | 1.34–6.39b | 0.0047b | ||

| Immunomodulatory | 1.46 | 0.80–2.65 | 0.2138 | ||

| Mesenchymal | 1.59b | 1.04–2.43b | 0.0317b | ||

| Mesenchymal stem-like | 2.06 | 0.92–4.63 | 0.0729 | ||

| Luminal androgen receptor | 0.70 | 0.47–1.05 | 0.0839 | ||

| MAGED4 | 221261_x_at | Basal-like 1 | 1.61b | 1.00–2.59b | 0.0494b |

| Basal-like 2 | 0.56 | 0.25–1.26 | 0.1558 | ||

| Immunomodulatory | 0.64 | 0.34–1.18 | 0.1502 | ||

| Mesenchymal | 0.80 | 0.51–1.26 | 0.3402 | ||

| Mesenchymal stem-like | 3.16b | 0.94–10.56b | 0.0488b | ||

| Luminal androgen receptor | 1.59b | 1.05–2.40b | 0.0267b | ||

| MAGEE1 | 1556047_s_at | Basal-like 1 | 1.74 | 0.90–3.37 | 0.0980 |

| Basal-like 2 | 0.25a | 0.07–0.85a | 0.0160a | ||

| Immunomodulatory | 0.41 | 0.12–1.37 | 0.1343 | ||

| Mesenchymal | 1.82b | 1.06–3.15b | 0.0284b | ||

| Mesenchymal stem-like | 0.41 | 0.15–1.13 | 0.0757 | ||

| Luminal androgen receptor | 0.73 | 0.43–1.26 | 0.2576 | ||

| MAGEE2 | 1553254_at | Basal-like 1 | 0.58 | 0.27–1.26 | 0.1636 |

| Basal-like 2 | 0.60 | 0.25–1.43 | 0.2440 | ||

| Immunomodulatory | 1.91 | 0.82–4.41 | 0.1257 | ||

| Mesenchymal | 0.72 | 0.39–1.30 | 0.2718 | ||

| Mesenchymal stem-like | 0.34a | 0.12–0.97a | 0.0345a | ||

| Luminal androgen receptor | 1.59 | 0.90–2.80 | 0.1067 | ||

| MAGEF1 | 218176_at | Basal-like 1 | 0.75 | 0.46–1.23 | 0.2538 |

| Basal-like 2 | 0.33a | 0.14–0.81a | 0.0110a | ||

| Immunomodulatory | 0.57 | 0.32–1.04 | 0.0623 | ||

| Mesenchymal | 1.67 | 0.98–2.84 | 0.0573 | ||

| Mesenchymal stem-like | 0.41a | 0.18–0.94a | 0.0292a | ||

| Luminal androgen receptor | 0.61a | 0.41–0.91a | 0.0158a | ||

| MAGEH1 | 218573_at | Basal-like 1 | 1.87b | 1.16–3.02b | 0.0090b |

| Basal-like 2 | 2.17b | 1.06–4.40b | 0.0288b | ||

| Immunomodulatory | 1.89b | 1.05–3.42b | 0.0314b | ||

| Mesenchymal | 1.56b | 1.01–2.42b | 0.0421b | ||

| Mesenchymal stem-like | 0.56 | 0.23–1.36 | 0.1943 | ||

| Luminal androgen receptor | 1.72b | 1.15–2.59b | 0.0079b | ||

| MAGEL2 | 219894_at | Basal-like 1 | 1.55 | 0.96–2.49 | 0.0726 |

| Basal-like 2 | 0.55 | 0.25–1.20 | 0.1258 | ||

| Immunomodulatory | 1.63 | 0.82–3.25 | 0.1574 | ||

| Mesenchymal | 0.62a | 0.39–0.99a | 0.0433a | ||

| Mesenchymal stem-like | 1.50 | 0.67–3.33 | 0.3206 | ||

| Luminal androgen receptor | 0.61a | 0.41–0.93a | 0.0188a |

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

High mRNA expression levels associated with improved RFS

high mRNA expression levels associated with worse RFS. Total patients assigned a Pietenpol subtype (31), n=1,246; patients with the basal-like 1 subtype, n=239; patients with the basal-like 2 subtype, n=97; patients with the immunomodulatory subtype, n=290; patients with the mesenchymal subtype, n=229; patients with the mesenchymal stem-like subtype, n=115; patients with the luminal androgen receptor subtype, n=276. CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; MAGE, melanoma-associated antigen.

Discussion

Breast cancer, which is one of the most common malignant tumors, was the second leading cause of cancer-associated mortality among women worldwide in the year 2017 (1,2). MAGE gene family members have been demonstrated to be expressed in male germ line and placental cells, as well as in a number of different tumor types, including melanoma, brain, lung, prostate and breast cancer (31,32). The aberrant expression levels of the MAGE family members have been demonstrated to be associated with progressive disease; however, the mechanisms underlying how individual MAGE family members contribute to disease occurrence are largely unknown (33). In addition, to the best of our knowledge, many of these genes have not been reported in breast cancer.

In the present study, high mRNA expression levels of MAGEA5 were significantly associated with improved prognosis in luminal and basal-like breast cancer subtypes, and significantly associated with worse RFS in lymph node-positive breast cancer. In addition, high mRNA expression levels of MAGEA8 were significantly associated with improved prognosis in luminal and basal-like breast cancer subtypes, as well as HER2+ breast cancer. Previously, there have been few reports regarding the genes MAGEA5 and MAGEA8 in breast cancer, despite other members of the MAGEA family being investigated in this disease. Raghavendra et al (34) revealed that MAGEA1 is frequently expressed in triple-negative breast cancer, and Park et al (35) demonstrated that MAGEA2 promotes the progression of breast cancer by regulating the Akt and Erk1/2 pathways. Taylor et al (36) suggested that a vaccine that targets MAGEA10 may be of potential use in ≤70% of breast cancers. Abd-Elsalam and Ismaeil (37) reported that measuring the expression levels of the gene MAGEA1-A6 and MAGEA12 at the same time may aid in monitoring the effectiveness of breast cancer therapy. Through a comprehensive analysis, MAGEA5 and MAGEA8 were predicted to serve a protective role in the occurrence and development of breast cancer in the present study.

The administration of a MAGEB vaccination to elderly mice (20 months) leads to the absence of CD8 T-cell responses and reduced protection against metastatic breast cancer (38). In the present study, high mRNA expression levels of MAGEB4 and MAGEB6 were significantly associated with improved RFS in all breast cancer subtypes; high MAGEB6 expression was significantly associated with improved RFS in lymph node-negative, tumor grades I and III, but was also associated with worse RFS in TP53 wild-type breast cancer. High mRNA expression levels of MAGEB4 were significantly associated with improved RFS in TP53-mutated breast cancer, but also with worse RFS in grade I breast cancer. MAGEB18 was moderately associated with worse RFS in all breast cancer, and in immunomodulatory and luminal androgen receptor breast cancer subtypes. Previous studies have demonstrated that MAGEB4 may be a potential biomarker in patients with transitional cell carcinoma (39), and that it is specifically expressed during germ cell differentiation (40). The mRNA-positivity expression of MAGEB6 is associated with a poor prognosis in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (41), and the mouse MAGEB18 gene encodes a ubiquitously expressed type I MAGE protein, and regulates cell proliferation and apoptosis in melanoma B16-F0 cells (42). Overall, to the best of our knowledge, there are currently no published studies that demonstrate the function of the MAGE family members in breast cancer, and only a small number of studies that indicate their association with other diseases. Following a detailed database analysis, MAGEB18 was predicted to have a damaging effect on the occurrence and development of breast cancer in the present study. Despite the contrasting prognostic effects of MAGEB4 and MAGEB6 in the different types of breast cancer, it could be suggested that these two molecules are more likely to serve roles as tumor suppressor genes, according to the results from the present study. Further investigation is required to verify this suggestion.

MAGEC was also analyzed in the present study. It was revealed that high mRNA expression levels of MAGEC3 were significantly associated with improved RFS in luminal, basal, HER2+, tumor grade II and mesenchymal stem-like breast cancer subtypes. Eng et al (43) indicated that MAGEC3 may be associated with earlier onset of ovarian cancer. Bao et al (44) used a single-cell sample of >100 pairs of primary breast cancer and corresponding metastatic lymph node samples to perform whole exome and deep-target sequencing analyses, and revealed that MAGEC3 is associated with lymph node metastasis in patients with breast cancer. In the present study it was demonstrated that high mRNA expression levels of MAGEC3 were associated with worse RFS in lymph node-status (positive) breast cancer, but were also associated with improved RFS in lymph node-status (negative)breast cancer; however, these results were not statistically significant. These results provided further support for the hypothesis that MAGEC3 may promote cell metastasis in breast cancer, particularly lymph node metastasis.

High mRNA expression levels of MAGED2 and MAGED3 were significantly associated with improved RFS in all breast cancer. High mRNA expression levels of MAGED2 were significantly associated with improved RFS in lymph node-positive and -negative breast cancer, as well as in the basal-like 2 breast cancer subtype; in contrast, high mRNA expression levels of MAGED2 were associated with worse RFS in HER2+, all basal-like, TP53-mutated, tumor grade III and basal-like 1 breast cancer subtype; high mRNA expression levels of MAGED3 were significantly associated with improved RFS in luminal, lymph node-positive and TP53-mutated breast cancer, but also with worse RFS in basal-like 2 subtype, mesenchymal subtype and tumor grade III breast cancer. High mRNA expression levels of MAGED4 were significantly associated with worse RFS in lymph node-positive and -negative, TP53 wild-type, basal-like 1, mesenchymal stem-like, luminal androgen receptor breast cancer, and all breast cancer. A previous study revealed that MAGED2 is able to control cell cycle progression and modulate the DNA damage response (45), and that increased expression of MAGED2 is associated with nodal and hematogenous metastasis and is an independent prognostic factor for gastric cancer (26,46). Zhang et al (47) reported that MAGED4 is frequently and highly expressed in glioma, and is partly regulated by DNA methylation. Ma et al (48) reported that MAGED4 may be used as a specific antigen for non-small cell lung cancer to influence the improvement of diagnosis, prognosis and immunological therapy outcomes in patients with lung cancer. According to these data, it was predicted that MAGED4 may be a cancer-promoting gene in breast cancer; however, MAGED2 and MAGED3 may have different effects depending on the type of breast cancer.

High mRNA expression levels of MAGEE1 were significantly associated with improved RFS in grade I and basal-like 2 breast cancer, but also with worse RFS in grade III and mesenchymal breast cancer; high mRNA expression levels of MAGEE2 were significantly associated with improved RFS in basal, lymph node-negative and mesenchymal stem-like breast cancer, but also with worse RFS in TP53 wild-type breast cancer. MAGEE2 expression has been reported to be associated with poor OS in The Cancer Genome Atlas human breast cancer cohort (n=1,082) (49). In general, these findings indicated that MAGEE2 was closely associated with the occurrence and development of breast cancer, particularly in TP53 wild-type breast cancer. However, whether MAGEE2 can be used as a prognostic factor requires further investigation.

High mRNA expression levels of MAGEF1 were significantly associated with improved RFS in basal, lymph node-positive, grade II, basal-like 2, mesenchymal stem-like and luminal androgen receptor breast cancer, but also with worse RFS in lymph node-negative, TP53-mutated and TP53 wild-type breast cancer. Stone et al (50) demonstrated that MAGEF1 is ubiquitously expressed in normal tissues, as well as in melanoma, leukemia, ovarian and cervical tumor tissues and cell lines. It is possible, therefore, that the mechanism underlying MAGEF1 in these different types of breast cancer varies, but whether MAGEF1 can be used as a prognostic factor in TP53-mutated or wild-type patients requires further investigation.

Finally, high mRNA expression levels of MAGEH1 were significantly associated with worse RFS in luminal B, HER2+, basal, basal-like 1 and luminal androgen receptor breast cancer subtypes, but also with improved RFS in tumor grades I and II breast cancer. High mRNA expression levels of MAGEL2 were significantly associated with improved RFS in luminal A breast cancer subtypes, but also with worse RFS in tumor grade III breast cancer. Wang et al (51) demonstrated that MAGEH1 enhances hepatocellular carcinoma progression and serves as a biomarker for patient prognosis, whereas Ojima et al (52) revealed that negative expression (anti-MAGEH1) of the MAGEH1 protein serves as a potential predictive marker for the effectiveness of gemcitabine therapy in biliary tract carcinoma. These findings, while preliminary, suggested that MAGEH1 and MAGEL2 have effects in breast cancer patients with different pathological grades.

Despite obtaining a number of useful insights in the present study, there were some limitations. Firstly, the roles that the selected members of the MAGE family serve in breast cancer were demonstrated using bioinformatics analyses only. Secondly, the underlying molecular mechanisms were not identified. Thus, more in-depth investigations in vitro and in vivo are required in order to verify the conclusions drawn within the present study.

In summary, the prognostic value of the mRNA expression levels of 29 members of the MAGE family were analyzed in patients with breast cancer using the Kaplan-Meier plotter database. Through searching PubMed and other database, among these 29 members, 14 members were significantly associated with the prognosis of patients with breast cancer. Further investigation regarding the prognostic values of the MAGE family members in breast cancer with different clinical features suggested that MAGEA5, MAGEA8, MAGEB4 and MAGEB6 may have protective roles in the occurrence and development of breast cancer, whereas MAGEB18 and MAGED4 may possess carcinogenic effects. MAGED2, MAGED3 and MAGEF1 incur different effects depending on the type of breast cancer. It is worth noting that MAGEC3 may promote cell metastasis in breast cancer, particularly lymph node metastasis. Whether MAGEE2, MAGEH1 and MAGEL2 may be used as prognostic factors in TP53 wild-type breast cancer, as well as in the different pathological grades of breast cancer requires further study.

The present study provided novel insights regarding the contribution of the MAGE family members to breast cancer progression and may aid in the discovery of MAGE-target inhibitors for treating breast cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- MAGE

melanoma-associated antigen

- GEO

Gene Expression Omnibus

- RFS

relapse-free survival

- OS

overall survival

- DMFS

distant metastasis-free survival

- PPS

post-progression survival

- HR

hazard ratio

- CI

confidence interval

Funding

The present study was funded by Beijing Dongcheng District Excellent Talents Training Project (grant no. 2014080536381G064).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

BJ and YW conceived and designed the study. JW and YYW managed and maintained research data for initial and future use, and applied statistical, mathematical, compu-tational, and other techniques to analyze or synthesize research data. BJ, XZ and YY prepared figures and tables, interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Mansoori B, Mohammadi A, Ghasabi M, Shirjang S, Dehghan R, Montazeri V, Holmskov U, Kazemi T, Duijf P, Gjerstorff M, Baradaran B. miR-142-3p as tumor suppressor miRNA in the regulation of tumorigenicity, invasion and migration of human breast cancer by targeting Bach-1 expression. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:9816–9825. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng CW, Yu JC, Hsieh YH, Liao WL, Shieh JC, Yao CC, Lee HJ, Chen PM, Wu PE, Shen CY. Increased cellular levels of MicroRNA-9 and MicroRNA-221 correlate with cancer stemness and predict poor outcome in human breast cancer. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;48:2205–2218. doi: 10.1159/000492561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao L, Zhao Y, He Y, Li Q, Mao Y. The functional pathway analysis and clinical significance of miR-20a and its related lncRNAs in breast cancer. Cell Signal. 2018;51:152–165. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2018.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shen J, Cao B, Wang Y, Ma C, Zeng Z, Liu L, Li X, Tao D, Gong J, Xie D. Hippo component YAP promotes focal adhesion and tumour aggressiveness via transcriptionally activating THBS1/FAK signalling in breast cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018;37:175. doi: 10.1186/s13046-018-0850-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jungbluth AA, Ely S, DiLiberto M, Niesvizky R, Williamson B, Frosina D, Chen YT, Bhardwaj N, Chen-Kiang S, Old LJ, Cho HJ. The cancer-testis antigens CT7 (MAGE-C1) and MAGE-A3/6 are commonly expressed in multiple myeloma and correlate with plasma-cell proliferation. Blood. 2005;106:167–174. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sienel W, Varwerk C, Linder A, Kaiser D, Teschner M, Delire M, Stamatis G, Passlick B. Melanoma associated antigen (MAGE)-A3 expression in Stages I and II non-small cell lung cancer: Results of a multi-center study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;25:131–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2003.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiser TS, Ohnmacht GA, Guo ZS, Fischette MR, Chen GA, Hong JA, Nguyen DM, Schrump DS. Induction of MAGE-3 expression in lung and esophageal cancer cells. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71:295–302. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(00)02421-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bergeron A, Picard V, LaRue H, Harel F, Hovington H, Lacombe L, Fradet Y. High frequency of MAGE-A4 and MAGE-A9 expression in high-risk bladder cancer. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:1365–1371. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Otte M, Zafrakas M, Riethdorf L, Pichlmeier U, Löning T, Jänicke F, Pantel K. MAGE-A gene expression pattern in primary breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6682–6687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simpson AJ, Caballero OL, Jungbluth A, Chen YT, Old LJ. Cancer/testis antigens, gametogenesis and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:615–625. doi: 10.1038/nrc1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chomez P, De Backer O, Bertrand M, De Plaen E, Boon T, Lucas S. An overview of the MAGE gene family with the identification of all human members of the family. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5544–5551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Espantman KC, O'Shea CC. aMAGEing new players enter the RING to promote ubiquitylation. Mol Cell. 2010;39:835–837. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao J, Wang Y, Mu C, Xu Y, Sang J. MAGEA1 interacts with FBXW7 and regulates ubiquitin ligase-mediated turnover of NICD1 in breast and ovarian cancer cells. Oncogene. 2017;36:5023–5034. doi: 10.1038/onc.2017.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joosse SA, Müller V, Steinbach B, Pantel K, Schwarzenbach H. Circulating cell-free cancer-testis MAGE-A RNA, BORIS RNA, let-7b and miR-202 in the blood of patients with breast cancer and benign breast diseases. Br J Cancer. 2014;111:909–917. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ayyoub M, Scarlata CM, Hamaï A, Pignon P, Valmori D. Expression of MAGE-A3/6 in primary breast cancer is associated with hormone receptor negative status, high histologic grade, and poor survival. J Immunother. 2014;37:73–76. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cabezon T, Gromova I, Gromov P, Serizawa R, Timmermans Wielenga V, Kroman N, Celis JE, Moreira JM. Proteomic profiling of triple-negative breast carcinomas in combination with a three-tier orthogonal technology approach identifies Mage-A4 as potential therapeutic target in estrogen receptor negative breast cancer. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2013;12:381–394. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M112.019786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hussein YM, Gharib AF, Etewa RL, El-Shal AS, Abdel-Ghany ME, Elsawy WH. The melanoma-associated antigen-A3, -A4 genes: relation to the risk and clinicopathological parameters in breast cancer patients. Mol Cell Biochem. 2011;351:261–268. doi: 10.1007/s11010-011-0734-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lian Y, Sang M, Ding C, Zhou X, Fan X, Xu Y, Lü W, Shan B. Expressions of MAGE-A10 and MAGE-A11 in breast cancers and their prognostic significance: A retrospective clinical study. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2012;138:519–527. doi: 10.1007/s00432-011-1122-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu X, Tang X, Lu M, Tang Q, Zhang H, Zhu H, Xu N, Zhang D, Xiong L, Mao Y, Zhu J. Overexpression of MAGE-A9 predicts unfavorable outcome in breast cancer. Exp Mol Pathol. 2014;97:579–584. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hou SY, Sang MX, Geng CZ, Liu WH, Lü WH, Xu YY, Shan BE. Expressions of MAGE-A9 and MAGE-A11 in breast cancer and their expression mechanism. Arch Med Res. 2014;45:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Badovinac Crnjevic T, Spagnoli G, Juretić A, Jakić-Razumović J, Podolski P, Šarić N. High expression of MAGE-A10 cancer-testis antigen in triple-negative breast cancer. Med Oncol. 2012;29:1586–1891. doi: 10.1007/s12032-011-0120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xia LP, Xu M, Chen Y, Shao WW. Expression of MAGE-A11 in breast cancer tissues and its effects on the proliferation of breast cancer cells. Mol Med Rep. 2013;7:254–258. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sypniewska RK, Hoflack L, Tarango M, Gauntt S, Leal BZ, Reddick RL, Gravekamp C. Prevention of metastases with a Mage-b DNA vaccine in a mouse breast tumor model: potential for breast cancer therapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;91:19–28. doi: 10.1007/s10549-004-6454-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sypniewska RK, Hoflack L, Bearss DJ, Gravekamp C. Potential mouse tumor model for pre-clinical testing of mage-specific breast cancer vaccines. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2002;74:221–233. doi: 10.1023/A:1016367104015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hou S, Sang M, Zhao L, Hou R, Shan B. The expression of MAGE-C1 and MAGE-C2 in breast cancer and their clinical significance. Am J Surg. 2016;211:142–151. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Du Q, Zhang Y, Tian XX, Li Y, Fang WG. MAGE-D1 inhibits proliferation, migration and invasion of human breast cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2009;22:659–665. doi: 10.3892/or_00000486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gyorffy B, Lanczky A, Eklund AC, Denkert C, Budczies J, Li Q, Szallasi Z. An online survival analysis tool to rapidly assess the effect of 22,277 genes on breast cancer prognosis using microarray data of 1,809 patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;123:725–731. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0674-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bertero L, Massa F, Metovic J, Zanetti R, Castellano I, Ricardi U, Papotti M, Cassoni P. Eighth Edition of the UICC Classification of Malignant Tumours: An overview of the changes in the pathological TNM classification criteria-What has changed and why? Virchows Arch. 2018;472:519–531. doi: 10.1007/s00428-017-2276-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haffty BG, Yang Q, Reiss M, Kearney T, Higgins SA, Weidhaas J, Harris L, Hait W, Toppmeyer D. Locoregional relapse and distant metastasis in conservatively managed triple negative early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5652–5657. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Campagnolo C, Meyers KJ, Ryan T, Atkinson RC, Chen YT, Scanlan MJ, Ritter G, Old LJ, Batt CA. Real-Time, label-free monitoring of tumor antigen and serum antibody interactions. J Biochem Biophys Methods. 2004;61:283–298. doi: 10.1016/j.jbbm.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krishnadas DK, Bai F, Lucas KG. Cancer testis antigen and immunotherapy. Immunotargets Ther. 2013;2:11–19. doi: 10.2147/ITT.S35570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weon JL, Potts PR. The MAGE protein family and cancer. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2015;37:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raghavendra A, Kalita-de Croft P, Vargas AC, Smart CE, Simpson PT, Saunus JM, Lakhani SR. Expression of MAGE-A and NY-ESO-1 cancer/testis antigens is enriched in triple-negative invasive breast cancers. Histopathology. 2018;73:68–80. doi: 10.1111/his.13498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park S, Sung Y, Jeong J, Choi M, Lee J, Kwon W, Jang S, Park SJ, Kim HS, Lee MH, et al. hMAGEA2 promotes progression of breast cancer by regulating Akt and Erk1/2 pathways. Oncotarget. 2017;8:37115–37127. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taylor M, Bolton LM, Johnson P, Elliott T, Murray N. Breast cancer is a promising target for vaccination using cancer-testis antigens known to elicit immune responses. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9:R46. doi: 10.1186/bcr1749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abd-Elsalam EA, Ismaeil NA. Melanoma-associated antigen genes: A new trend to predict the prognosis of breast cancer patients. Med Oncol. 2014;31:285. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0285-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Castro F, Leal B, Denny A, Bahar R, Lampkin S, Reddick R, Lu S, Gravekamp C. Vaccination with Mage-b DNA induces CD8 T-cell responses at young but not old age in mice with metastatic breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:1329–1337. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Afsharpad M, Nowroozi MR, Ayati M, Saffari M, Nemati S, Mohebbi E, Nekoohesh L, Zendehdel K, Modarressi MH. ODF4, MAGEA3, and MAGEB4: Potential biomarkers in patients with transitional cell carcinoma. Iran Biomed J. 2018;22:160–170. doi: 10.22034/ibj.22.3.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Osterlund C, Töhönen V, Forslund KO, Nordqvist K. Mage-b4, a novel melanoma antigen (MAGE) gene specifically expressed during germ cell differentiation. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1054–1061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zamunér FT, Karia BT, de Oliveira CZ, Santos CR, Carvalho AL, Vettore AL. A comprehensive expression analysis of cancer testis antigens in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma revels MAGEA3/6 as a marker for recurrence. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;14:828–834. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin Y, Wen T, Meng X, Wu Z, Zhao L, Wang P, Hong Z, Yin Z. The mouse Mageb18 gene encodes a ubiquitously expressed type I MAGE protein and regulates cell proliferation and apoptosis in melanoma B16-F0 cells. Biochem J. 2012;443:779–788. doi: 10.1042/BJ20112054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eng KH, Szender JB, Etter JL, Kaur J, Poblete S, Huang RY, Zhu Q, Grzesik KA, Battaglia S, Cannioto R, et al. Paternal lineage early onset hereditary ovarian cancers: A Familial Ovarian Cancer Registry study. PLoS Genet. 2018;14:e1007194. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bao L, Qian Z, Lyng MB, Wang L, Yu Y, Wang T, Zhang X, Yang H, Brünner N, Wang J, Ditzel HJ. Coexisting genomic aberrations associated with lymph node metastasis in breast cancer. J Clin Invest. 2018;128:2310–2324. doi: 10.1172/JCI97449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kömhoff M, Laghmani K. MAGED2: A novel form of antenatal Bartter's syndrome. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2018;27:323–328. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hashimoto R, Kanda M, Takami H, Shimizu D, Oya H, Hibino S, Okamura Y, Yamada S, Fujii T, Nakayama G, et al. Aberrant expression of melanoma-associated antigen-D2 serves as a prognostic indicator of hepatocellular carcinoma outcome following curative hepatectomy. Oncol Lett. 2015;9:1201–1206. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.2823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang QM, Shen N, Xie S, Bi SQ, Luo B, Lin YD, Fu J, Zhou SF, Luo GR, Xie XX, Xiao SW. MAGED4 expression in glioma and upregulation in glioma cell lines with 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine treatment. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:3495–3501. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.8.3495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ma QY, Pang LW, Chen ZM, Zhu YJ, Chen G, Chen J. The significance of MAGED4 expression in non-small cell lung cancer as analyzed by real-time fluorescence quantitative PCR. Oncol Lett. 2012;4:733–738. doi: 10.3892/ol.2012.786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leung YK, Govindarajah V, Cheong A, Veevers J, Song D, Gear R, Zhu X, Ying J, Kendler A, Medvedovic M, et al. Gestational high-fat diet and bisphenol A exposure heightens mammary cancer risk. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2017;24:365–378. doi: 10.1530/ERC-17-0006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stone B, Schummer M, Paley PJ, Crawford M, Ford M, Urban N, Nelson BH. MAGE-F1, a novel ubiquitously expressed member of the MAGE superfamily. Gene. 2001;267:173–182. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(01)00406-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang PC, Hu ZQ, Zhou SL, Zhan H, Zhou ZJ, Luo CB, Huang XW. Downregulation of MAGE family member H1 enhances hepatocellular carcinoma progression and serves as a biomarker for patient prognosis. Future Oncol. 2018;14:1177–1186. doi: 10.2217/fon-2017-0672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ojima H, Yoshikawa D, Ino Y, Shimizu H, Miyamoto M, Kokubu A, Hiraoka N, Morofuji N, Kondo T, Onaya H, et al. Establishment of six new human biliary tract carcinoma cell lines and identification of MAGEH1 as a candidate biomarker for predicting the efficacy of gemcitabine treatment. Cancer Sci. 2010;101:882–888. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01462.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.