Abstract

Objective:

To determine if maternal health literacy influences early infant immunization status.

Methods:

Longitudinal prospective cohort study of 506 Medicaid-eligible mother-infant dyads. Immunization status at age 3 and 7 months was assessed in relation to maternal health literacy measured at birth using the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (short version). Multivariable logistic regression quantified the effect of maternal health literacy on immunization status adjusting for the relevant covariates.

Results:

The cohort consists of primarily African-American (87%), single (87%) mothers (mean age 23.4 yrs). Health literacy was inadequate or marginal among 24% of mothers. Immunizations were up-to-date among 73% of infants at age 3 months and 43% at 7 months. Maternal health literacy was not significantly associated with immunization status at either 3 or 7 months. In multivariable analysis, compared to infants who had delayed immunizations at 3 months, infants with up-to-date immunizations at 3 months were 11.3 times (95%CI 6.0–21.3) more likely to be up-to-date at 7 months. The only strong predictors of up-to-date immunization status at 3 months were maternal education (high school graduate or beyond) and attending a hospital-affiliated clinic.

Conclusions:

Though maternal health literacy is not associated with immunization status in this cohort, later immunization status is most strongly predicted by immunization status at 3 months. These results further support the importance of intervening from an early age to ensure that infants are fully protected against vaccine preventable diseases.

Keywords: health literacy, immunizations, pediatric care

Approximately one-third of adult Americans has limited health literacy, affecting their ability to obtain, understand and apply health information.1 Among adults, multiple studies have shown that limited health literacy is associated with poor health outcomes, inadequate receipt of preventive care services and increased health care costs.2–6 In spite of this evidence about adult health literacy, little is known about the relationship between parental health literacy (or literacy in general) and child health outcomes.7–10 Given that children most often depend on caregivers to obtain necessary health care, it is likely that parental health literacy influences child health outcomes. However, previous research shows mixed results. One recent retrospective cohort study at a university pediatric clinic demonstrated that asthmatic children of parents with low literacy were more likely to visit the emergency room, be hospitalized, or miss school.7 Other studies have found significant associations between high parental literacy and likelihood of breastfeeding 11 as well as improved glycemic control among diabetic children.12,13 Another study examined the association between literacy status, childhood health maintenance procedures, and parental understanding of child diagnosis and medication. No significant association was observed; however, this study followed families for only 48 hours after the visit.8

Vaccination is one of the most important preventive care practices for children and understanding the factors that predict immunization status can improve targeted immunization outreach activities. Specific socio-demographic characteristics and receipt of prenatal care services have all been associated with early immunization.14–21 Recent attention has also focused on the importance of early initiation of immunizations in predicting up-to-date immunizations in the future.18 However, the role of maternal health literacy in predicting immunization status remains unexplored. It is possible that low levels of maternal health literacy may hinder maternal understanding of the importance of vaccination or how to access infant vaccination programs, thus leading to delayed vaccination. Examining the role of health literacy also may help better explain the mechanisms by which other factors affect immunization status. For example, having adequate health literacy may attenuate the effects of other socio-demographic characteristics on immunization status.

The aim of this study is to investigate the association between maternal health literacy and early immunization status among a Medicaid-eligible inner city birth cohort. We hypothesize that mothers with an adequate level of health literacy will be more likely to have infants who are up-to-date on their immunization status at both 3 and 7 months of age after adjusting for other factors known to affect early immunization status. We also hypothesize that maternal health literacy might attenuate the effect of maternal education on immunization status.

Methods:

Study Design, Study Population and Data Sources:

This is a longitudinal prospective cohort study of Medicaid-eligible mothers and their healthy infants enrolled in an ongoing study entitled The Health Insurance Improvement Project (HIP) that aims to determine maternal and child patterns of Medicaid enrollment. Between June 15, 2005 and August 6, 2006, study subjects were recruited from the well baby nursery at a large urban hospital shortly after the infant’s birth. Inclusion criteria were maternal Medicaid eligibility and maternal English proficiency. Infants who had a gestational age less than 36 weeks, birth weight less than 2500 grams, or who were not in the well baby nursery after delivery were excluded. Infants entering foster care or adoption services were also excluded.

Upon enrollment, mothers completed a baseline survey, which included sociodemographic information, public benefits received and type of health insurance. In addition, each mother was given the short form Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (S-TOFHLA). The S-TOFHLA is a well-validated measure of functional health literacy that uses specific health related examples to assess reading comprehension.22 The short form contains 2 reading passages with scores ranging from 0 to 36 categorized as follows: ≤16 limited; 17–22 marginal; ≥ 23 adequate.22 The primary predictor of interest was maternal health literacy as measured by the S-TOFHLA score.

The primary outcomes of interest were infant up-to-date immunization status at 3 and 7 months of age as established by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.23 For 3 months of age, up-to-date status was measured as the receipt of at least one Hepatitis B (HepB), one polio, one Haemophilus Influenza Type b (Hib), one conjugate pneumococcal vaccine (PCV7) and one diphtheria / tetanus / acellular pertussis (DTaP) containing vaccine. For 7 months of age, up-to-date status was measured as the receipt of 3 HepB, 2 polio, at least 2 Hib, 3 PCV7 and 3 DTaP containing vaccines. Exclusion of PCV7 from assessment of up-to-date status did not significantly change any reported results. Of note, there were no vaccine shortages during the study period. Using individual identifiers collected at enrollment, immunization data for study subjects were abstracted from the Philadelphia Department of Health Division (PDPH) of Disease Control Immunization Registry (KIDS) by PDPH staff. KIDS contains information for every infant vaccinated within Philadelphia county, reporting to the registry is mandated for all vaccinations given to children under the age of 19 years by Philadelphia providers, and medical record audits are performed regularly to ensure and increase data accuracy. A recent study found that 92% of children living in Philadelphia have an immunization record in KIDS 24 and the registry has served as a reliable source of data for several studies.25–27

Based on review of the literature about known predictors of immunization,14–21 covariates included maternal race/ethnicity, age, education level, receipt of prenatal care, WIC participation, marital status, employment status, infant birth order, presence of a congenital or chronic disease in the infant, and infant’s health care location (hospital-affiliated site, private office or community clinic / health center). In modeling the outcome of immunization status at age 7 months, we also included immunization status at age 3 months as a predictor because underimmunization at age 3 months is a known predictor for subsequent up-to-date status.18, 26

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Pennsylvania and The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses assessed whether maternal health literacy was significantly associated with up-to-date immunization status (yes/no) at 3 and 7 months of age after adjusting for relevant covariates. Maternal health literacy and all covariates except maternal age (continuous) were included as categorical variables. Chi-square tests were used to compare characteristics between enrolled mothers who provided immunization data and did not. Chi square tests were also used to compare the distribution of maternal health literacy and other covariates between infants based on immunization status. Logistic regression models were used to explore the association of each of the covariates as well as maternal health literacy with immunization status. We used a best subsets approach to create multivariable logistic regression models and choose the best fitting ones. We also explored the associations between covariates to exclude any variables highly associated with each other from these models. Plausible two-way interactions were evaluated. To assess the effect of missing immunization data on our results we conducted a sensitivity analysis assuming children with missing data were up to date and were not up to date. The results from this analysis remained unchanged, so we excluded children with missing immunization data from the analysis. To determine whether maternal health literacy attenuated the effect of maternal education on immunization status, we compared the coefficient for maternal education in nested models with and without maternal health literacy.

A Type I error level of 0.05 was used for all analyses. Subjects with missing values for any variables were excluded from multivariable models. All analyses were conducted using SAS software, version 9.1.3.

Results:

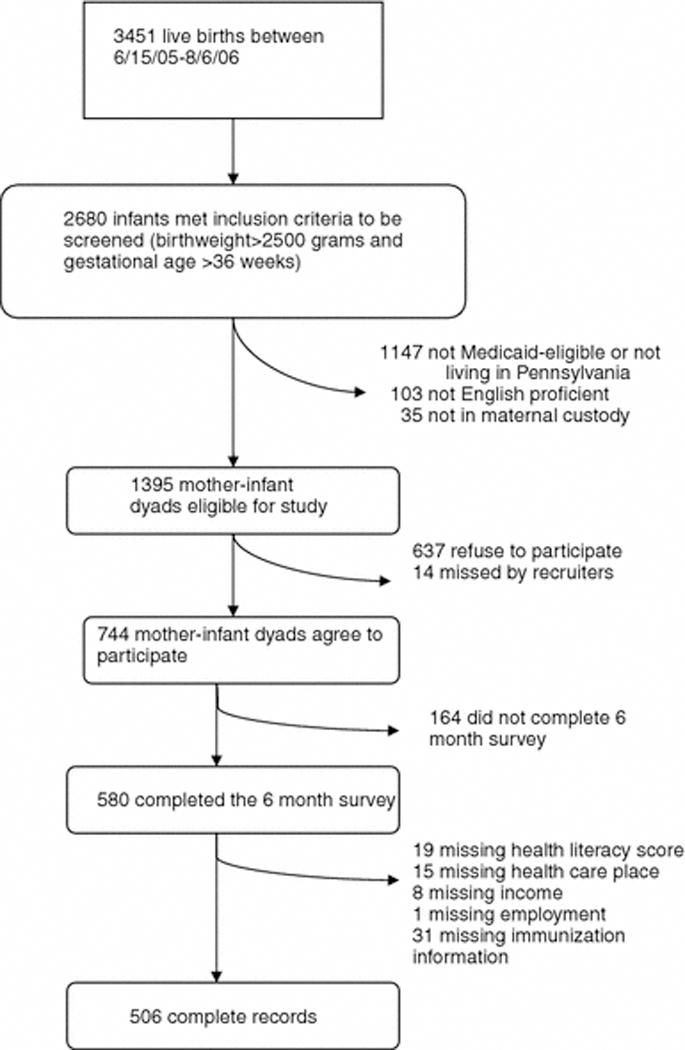

Of 3,451 live births during the recruitment period (6/15/2005–8/6/2006), 2,680 (77.7%) met inclusion criteria to be screened for the study (Figure 1). Of these, 1,285 were excluded based on study eligibility criteria leaving 1,395 eligible mother-infant dyads. Among eligible dyads, 637 (46%) mothers refused participation and 14 (1%) were missed by the recruiting team resulting in 744 (53% of eligible infants) enrolled in the study. Though African-American and working mothers were less likely to participate than mothers from other groups, there were no significant differences in maternal age, maternal education, maternal country of origin, or infant birth weight between participants and non-participants. Of the 744 enrolled mothers, 580 (78%) participants completed our 6 month follow up survey of which 19 (3%) were excluded for missing S-TOFHLA scores and 55 (7%) for missing other data leaving us with a sample size of 506 for our analysis. The 506 participants in the analytic sample were representative of the entire study sample (n = 744) in the distribution of maternal health literacy and other sociodemographic characteristics. Among the 580 participants who completed the 6 month follow-up, African-American infants were more likely to have immunization data than other groups, but there were no significant differences in maternal health literacy or other socio-demographic characteristics between infants with and without immunization data (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Study enrollment protocol

Table 1:

Characteristics of Infants With and Without Immunization Data

| Have Immunization Data (N=538) |

No Immunization Data (N=42) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race (%) | 0.06 | ||

| Black | 450 (83.6) | 30 (71.4) | |

| Other | 88 (16.4) | 12 (28.6) | |

| Marital Status (%) | 0.31 | ||

| Single/Divorced/Widowed | 478 (88.9) | 35 (83.3) | |

| Married | 60 (11.2) | 7 (16.7) | |

| Education (%) | 0.67 | ||

| Less than high school | 169 (31.4) | 11 (26.2) | |

| High school | 126 (23.4) | 12 (28.6) | |

| More than high school | 243 (45.2) | 19 (42.2) | |

| Health Literacy (%) | 0.23 | ||

| Inadequate | 53 (9.9) | 5 (11.9) | |

| Marginal | 72 (13.4) | 2 (4.8) | |

| Adequate | 394 (73.2) | 35 (83.3) | |

| Missing | 19 (3.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Prenatal Care (%) | 0.76 | ||

| All/Most of the time | 496 (92.2) | 40 (95.2) | |

| Some/None of the time | 42 (7.8) | 2 (4.8) | |

| Birth Order (%) | 0.79 | ||

| First born | 200 (37.2) | 17 (40.5) | |

| Second born | 142 (26.4) | 12 (28.6) | |

| Third or more | 196 (36.4) | 13 (31.0) | |

| Income (%) | 0.19 | ||

| Under $250/month | 57 (10.6) | 1 (2.4) | |

| $251-$500/month | 143 (26.7) | 14 (33.3) | |

| $501-$999/month | 155 (28.8) | 12 (28.6) | |

| $1000-$1499/month | 63 (11.7) | 7 (16.7) | |

| $1500+/month | 64 (11.9) | 2 (4.8) | |

| Missing | 56 (10.4) | 6 (14.3) | |

| Country (%) | 1.00 | ||

| US Born | 501 (93.1) | 39 (92.9) | |

| Non-US Born | 37 (6.9) | 3 (7.1) | |

| Maternal Age (IQR) | 23.4 (19–26) | 24.1 (19–29) | 0.94 |

Note: p-value is for the exact X2 test of association for categorical variables and for the t-test for maternal age.

The cohort consists of young, primarily African-American (84%), single (90%) mothers (Table 2). Maternal health literacy was inadequate or marginal among nearly one-fourth of mothers and 31% had less than a high school education. Seventy-three percent of infants had up-to-date immunizations at age 3 months and 43.3% were up-to-date at age 7 months. In bivariate analysis, infants whose mothers had completed high school or beyond were at least 3 times more likely to be up-to-date at 3 months of age than those whose mothers had not completed high school. Furthermore, infants receiving care in a hospital-affiliated setting were nearly 4 times more likely to be up-to-date at 3 months than those attending private practices or community health centers. At 7 months, though health care location remained significantly associated with up-to-date status, maternal education did not and different factors emerged as important predictors. At 7 months of age, third-born children were nearly twice as likely to not be up-to-date as first-or second-born children and children of single mothers were 1.3 times more likely to not be up-to-date than others. In particular, compared to infants who were up-to-date at 3 months, children who were not up-to-date at 3 months were 9.2 times more likely to not be up-to-date at 7 months (p<0.001). Notably, though the correlation between maternal education and health literacy was strong, it was not perfect (Table 3); one-third of mothers who had graduated high school had inadequate/marginal health literacy.

Table 2:

Population characteristics and association with immunization status at ages 3 and 7 months.

| Up to Date at 3 Months | Up to Date at 7 Months | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N(%) | Yes | No | P – Valuea | Yes | No | P – Valuea | |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||||

| Total sample (N = 506) | 373 (74) | 133 (26) | 219 (43) | 287 (57) | |||

| Maternal Health Literacy | |||||||

| Inadequate/Marginal | 121(24) | 88 (73) | 33 (27) | 0.78 | 50 (41) | 71 (59) | 0.62 |

| Adequate | 385 (76) | 285 (74) | 100 (26) | 169 (44) | 216 (56) | ||

| Maternal Age | |||||||

| Under 18 | 46 (9) | 33 (72) | 13 (28) | 0.88 | 21 (46) | 25 (54) | 0.77 |

| 18 – 24 | 298 (59) | 222 (75) | 76 (26) | 125 (42) | 173 (58) | ||

| 25 and over | 162 (32) | 118 (73) | 44 (27) | 73 (45) | 89 (55) | ||

| Race | |||||||

| Black | 426 (84) | 316 (74) | 110 (26) | 0.59 | 181 (43) | 245 (58) | 0.41 |

| Otherb | 80 (16) | 57 (71) | 23 (29) | 38 (48) | 42 (53) | ||

| Marital Status | |||||||

| Single/Divorced/Widowed | 453 (90) | 329 (73) | 124 (27) | 0.08 | 189 (42) | 264(58) | 0.04 |

| Married | 53 (11) | 44 (83) | 9 (17) | 30 (57) | 23 (43) | ||

| Maternal Education | |||||||

| Less than High School | 159 (31) | 104 (65) | 55 (35) | 0.01 | 63 (40) | 96 (60) | 0.50 |

| High School | 119 (24) | 94 (79) | 25 (21) | 55 (46) | 64 (54) | ||

| More than High School | 228 (45) | 175 (77) | 53 (23) | 101 (44) | 127 (56) | ||

| Birth Order | |||||||

| First Born | 191 (38) | 144 (75) | 47 (25) | 0.26 | 96 (50) | 95 (50) | 0.01 |

| Second Born | 131 (26) | 101 (77) | 30 (23) | 60 (46) | 71 (54) | ||

| Third or More | 184 (36) | 128 (70) | 56 (30) | 63 (34) | 121 (66) | ||

| WIC | |||||||

| Yes | 347 (66) | 256 (74) | 91 (26) | 0.96 | 160 (46) | 187 (54) | 0.06 |

| No | 159 (31) | 117 (74) | 42 (26) | 59 (37) | 100 (63) | ||

| Prenatal Care | |||||||

| All/Most of the time | 467 (92) | 348 (75) | 119 (26) | 0.16 | 205 (44) | 262 (56) | 0.33 |

| Some/None of the time | 39 (8) | 25 (64) | 14 (36) | 14 (36) | 25 (64) | ||

| Incomec | |||||||

| Under $250/month | 73 (14.7) | 54 (74) | 19 (26) | 0.65 | 32 (44) | 41 (56) | 0.91 |

| $251 - $500/month | 149 (30.0) | 106 (71) | 43 (29) | 68 (46) | 81 (54) | ||

| $501 - $999/month | 153 (30.9) | 116 (76) | 37 (24) | 67 (44) | 86 (56) | ||

| $1000 - $1499/month | 57 (11.5) | 45 (79) | 12 (21) | 23 (40) | 34 (60) | ||

| $1500+/month | 64 (12.9) | 44 (69) | 20 (31) | 25 (39) | 39 (61) | ||

| Health Care Location | |||||||

| Hospital-affiliated site | 293 (58) | 232 (79) | 61 (21) | 0.01 | 144 (49) | 149 (51) | 0.01 |

| Private Office | 58 (12) | 38 (66) | 20 (35) | 18 (31) | 40 (69) | ||

| Community Clinic/Health Center | 155 (31) | 103 (67) | 52 (34) | 57 (37) | 98 (63) | ||

| Employment Statusd | |||||||

| Student | 118 (25) | 89 (75) | 29 (25) | 0.22 | 53 (45) | 65 (55) | 0.86 |

| Full Time | 106 (22) | 84 (79) | 22 (21) | 48 (45) | 58 (55) | ||

| Unemployed | 249 (53) | 176 (71) | 73 (29) | 106 (43) | 143 (57) | ||

| Up to Date at 3 Months | |||||||

| Yes | 373 (74) | --- | --- | --- | 206 (55) | 167 (45) | <.0001 |

| No | 133 (26) | --- | --- | --- | 13 (10) | 120(90) | |

p-value is for the X2 test of association.

Includes Hispanic, Asian and “Ethnically-Challenged” (as self-reported)

Missing 10 (<2.0% of sample)

Missing 33 (6.5% of sample)

Table 3.

The Association between Maternal Health Literacy and Maternal Education

| Maternal Health Literacy |

Less than High School (n, )%) |

High School (n, %) |

More than High School (n, %) |

P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 159 (31) | 119 (24) | 228 (45) | |

| Adequate | 112 (29) | 85 (22) | 188 (49) | 0.0096 |

| Inadequate/Marginal | 47 (39) | 34 (28) | 40 (33) | |

Results are from the x2 test for association (value of x2 = 9.29).

The variables that were found to be significantly associated with immunization status at 3 or 7 months of age in the bivariate analysis remained significant in multivariable models (Table 4). Maternal health literacy was not significantly associated with immunization status at either 3 or 7 months. Instead, other maternal characteristics and clinic type were associated with up-to-date status. These findings remained essentially unchanged when we analyzed mothers with inadequate health literacy separately from those with marginal health literacy. Thus, for ease of interpretation, we present the results by combining mothers with inadequate and marginal health literacy into one group. At 3 months, infants whose mothers had completed high school or beyond or who received care in a hospital-affiliated site were more likely to be up-to-date than others. At 7 months, infants whose mothers were married, whose mothers were older, who were first born or second born, and who were up-to-date at age 3 months were more likely to be up-to-date. Comparison of log-likelihoods between models with and without maternal education showed that maternal education had a significant impact on immunization status at 3 months of age but not at 7 months of age.

Table 4:

Adjusted odds ratios for predictors of up-to-date immunization status at ages 3 and 7 months.

| Up to Date at 3 Months | Up to Date at 7 Months | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval |

P-value | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval |

P-value |

| Maternal Health Literacy | ||||||

| Adequate | Reference | --- | --- | Reference | --- | --- |

| Marginal/Inadequate | 1.08 | 0.67 – 1.76 | 0.76 | 0.92 | 0.57 – 1.48 | 0.74 |

| Maternal Age | 1.02 | 0.97 – 1.08 | 0.44 | 1.07 | 1.01 – 1.12 | 0.01 |

| Race | ||||||

| Black | Reference | --- | --- | Reference | --- | --- |

| Other | 0.86 | 0.49 – 1.49 | 0.58 | 1.38 | 0.79 – 2.42 | 0.26 |

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Single | Reference | --- | --- | Reference | --- | --- |

| Other | 1.83 | 0.83 – 4.04 | 0.14 | 1.65 | 0.83 – 3.28 | 0.15 |

| Education | ||||||

| Less than high school | Reference | --- | Reference | --- | ---- | |

| High school | 2.04 | 1.16 – 3.57 | 0.01 | 0.96 | 0.55 – 1.65 | 0.87 |

| More than high school | 1.63 | 1.00–2.66 | 0.049 | 0.82 | 0.50–1.35 | 0.43 |

| Birth Order | ||||||

| First born | 1.53 | 0.86–2.73 | 0.15 | 2.91 | 1.63–5.19 | 0.0003 |

| Second born | 1.53 | 0.87–2.70 | 0.14 | 1.88 | 1.09–3.26 | 0.02 |

| Third or more | Reference | --- | --- | Reference | --- | --- |

| WIC | ||||||

| Yes | Reference | --- | --- | Reference | --- | --- |

| No | 1.14 | 0.72–1.80 | 0.58 | 0.67 | 0.43–1.05 | 0.08 |

| Prenatal Care | ||||||

| All/Most of the time | Reference | --- | --- | Reference | --- | --- |

| Some/None of the time | 0.57 | 0.29–1.24 | 0.17 | 1.15 | 0.51–2.57 | 0.74 |

| Health Care Location | ||||||

| Hospital-affiliated Site | Reference | --- | --- | Reference | --- | --- |

| Private Office | 0.50 | 0.27–0.94 | 0.03 | 0.51 | 0.26–1.01 | 0.05 |

| Community Clinic/Health Center | 0.52 | 0.33–0.83 | 0.005 | 0.75 | 0.48–1.18 | 0.22 |

| Up to Date at 3 Months | ||||||

| Yes | --- | ---- | --- | 11.32 | 6.04–21.21 | <.0001 |

| No | --- | --- | --- | Reference | --- | --- |

Note: Comparison of log-likelihoods between models with and without maternal education showed a significant effect of maternal education at 3 months but not at 7 months. The c-statistics were 0.65 for the model predicting up-to-date status at 3 months, 0.66 for the model predicting up-to date status at 7 months excluding the variable for status at 3 months, and 0.77 for the fully inclusive model predicting up-to-date status at 7 months as presented in the table. There were no significant differences in odds ratio estimates between models with and without maternal education. For ease of interpretation, only results for models including maternal education are presented.

Discussion:

To our knowledge, this is the first study that prospectively investigates the role of maternal health literacy on immunization status. In this cohort, maternal health literacy does not predict immunization status at either 3 or 7 months of age, suggesting that other factors are driving this health maintenance practice. Instead, early infant immunization status is associated with maternal education and age, marital status, health care location, prior immunization status, and birth order. These findings further support the importance of intervening from an early age through targeted outreach efforts to ensure that infants are fully protected against vaccine preventable diseases. In light of the current H1N1 epidemic, our findings also support continued investments in broad messaging to enhance seasonal and H1N1 vaccination programs for adults and children

As summarized in our introduction, previous studies investigating the influence of parental literacy, and specifically health literacy, on child health outcomes and health care utilization have produced mixed findings.7–12 In this study, we did not find an association between maternal health literacy and the specific child health outcome of immunization status. There are several potential explanations for our findings. First, as the cornerstone of preventive medicine, immunization is a high priority outcome for health care providers. In fact, there is a growing trend towards providing financial incentives (i.e. pay for performance) to providers for achieving high immunization rates.28,29 Thus, health care providers have strong incentives to ensure children are immunized, regardless of parental health literacy level and time required for parent education, obtaining consent, or scheduling visits. Second, we assessed immunization status using Philadelphia’s registry as opposed to provider charts. Though registry records have been shown to have lower up-to-date status than some types of physician charts, this non-differential misclassification is markedly reduced for practices utilizing electronic medical records.24 In this study, nearly half of the cohort attends practices that use electronic medical records and this would lead to an overestimate of the strength of association between health literacy and immunization status. Notably, in this cohort, we found no association between these factors. Apart from these limitations, our sample was predominantly African-American, English speaking, and restricted to those living in Pennsylvania; thus our findings may not be generalized to other populations. However, African-Americans are a historically medically underserved group and our findings provide specific information about risk factors in this population that can support targeted immunization outreach efforts.

We also found that maternal education and health literacy were strongly, but not perfectly, correlated. This finding supports the conceptualization of health literacy as a functional set of skills that may be an important predictor of individual ability to navigate the health care system and, ultimately, influence health outcomes. Though we did not observe an association between maternal health literacy and immunization status, we did observe that maternal education significantly influences immunization status at age 3 months whereby infants whose mothers have high school or greater education were more likely to be up-to-date. However, maternal education was not a significant influence on immunization status at 7 months. As we and others have shown,18 up-to-date status at 3 months is an overwhelmingly strong predictor of timely vaccination later in infancy and childhood and this effect may overshadow the influence of maternal education in later years. Our findings may also reflect the influence of maternal education on decisions about initiating vaccinations; that is, once mothers have decided to vaccinate and learned how to access the health care system, the likelihood of continuing vaccinations is overwhelmingly high. For providers, our findings reinforce the importance of avoiding medical jargon and resisting assumptions about health literacy skills based on a patient’s educational attainment. Additional research in this area is warranted.

Consistent with previous studies, 15,17,19,21,30,31 we found that birth order, maternal age, and practice type were important predictors of immunization status in early infancy. Though birth order was not important at 3 months of age, first and second-born children were more likely to up-to-date at 7 months of age than subsequent children. This pattern may reflect the competing demands for time among mothers with multiple children or, perhaps, the false sense of security among mothers whose prior children are healthy and have not suffered from vaccine-preventable illnesses.16 Given that we found that married mothers were also more likely to have infants with up-to-date immunizations at 7 months lends some support to the notion that married mothers have greater social supports to assist in managing competing demands and have greater capacity to ensure timely vaccinations.

Consistent with other studies,26 we also found that attending a hospital-affiliated site was a strong predictor of up-to-date immunization status at 3 months. Compared to private offices and community health centers, hospital-affiliated sites may have greater resources in terms of electronic health record immunization alerts or other information infrastructure supports that facilitate early initiation of immunizations and that this effect diminishes once immunizations are initiated.32 Notably, although our findings support a trend towards association between prenatal care and immunization status that did not reach statistical significance, this relationship has been established in previous studies.16,17,21,30,31

In summary, we found that health literacy is not associated with immunization status in early infancy. Instead, the strongest and vastly overwhelming predictor of future up-to-date immunization status is prior immunization status. We also found that maternal education is a strong predictor of early initiation of immunizations. Taken together, these findings support continued investments in early intervention efforts directed at improving early initiation of immunizations.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank Drs. Vic Spain and Barbara Watson at the Philadelphia Department of Public Health for supervising confirmation of immunizations from the Philadelphia electronic immunization registry and their support of this project. We thank the network of primary care physicians, their patients and families for their contribution to clinical research through the Pediatric Research Consortium (PeRC) at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Support: Dr. Pati and Ms. Mohamad were supported by a K23 HD047655 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Foerderer-Murray Award. Dr. Feemster was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars program at the University of Pennsylvania. Dr. Fiks was supported by institutional development funds from The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. The findings and conclusions in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Philadelphia Department of Public Health.

References

- 1.Nielsen-Bohlman L, Panzer AM, Kindig DA, eds. Health Literacy: A prescription to end confusion. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2004. Committee on Health Literacy, Board on Neuroscience and Behavioral Health, Institute of Medicine. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gazmararian JA, Parker RM, Baker DW. Reading skills and family planning knowledge and practices in a low-income managed-care population. Obstet Gynecol. February 1999;93(2):239–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindau ST, Tomori C, Lyons T, Langseth L, Bennett CL, Garcia P. The association of health literacy with cervical cancer prevention knowledge and health behaviors in a multiethnic cohort of women. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2002;186(5):938–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller LG, Liu H, Hays RD, et al. Knowledge of antiretroviral regimen dosing and adherence: a longitudinal study. Clin Infect Dis. February 15 2003;36(4):514–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schillinger D, Grumbach K, Piette J, et al. Association of health literacy with diabetes outcomes.[see comment]. JAMA. 2002;288(4):475–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scott TL, Gazmararian JA, Williams MV, Baker DW. Health literacy and preventive health care use among Medicare enrollees in a managed care organization. Medical Care. 2002;40(5):395–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeWalt DA, Dilling MH, Rosenthal MS, Pignone MP. Low parental literacy is associated with worse asthma care measures in children. AmbulPediatr. Jan-February 2007;7(1):25–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moon RY, Cheng TL, Patel KM, Baumhaft K, Scheidt PC. Parental literacy level and understanding of medical information. Pediatrics. August 1998;102(2):e25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenthal MS, Socolar RR, DeWalt DA, Pignone M, Garrett J, Margolis PA. Parents with low literacy report higher quality of parent-provider relationships in a residency clinic. Ambul Pediatr. Jan-February 2007;7(1):51–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanders LM, Thompson VT, Wilkinson JD. Caregiver health literacy and the use of child health services. Pediatrics. January 2007;119(1):e86–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaufman H, Skipper B, Small L, Terry T, McGrew M. Effect of literacy on breast-feeding outcomes. South Med J. March 2001;94(3):293–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ross LA, Frier BM, Kelnar CJ, Deary IJ. Child and parental mental ability and glycaemic control in children with Type 1 diabetes. DiabetMed. May 2001;18(5):364–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schillinger D, Piette J, Grumbach K, et al. Closing the loop: physician communication with diabetic patients who have low health literacy. Arch Intern Med. January 13 2003;163(1):83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allred NJ, Wooten KG, Kong Y. The association of health insurance and continuous primary care in the medical home on vaccination coverage for 19-to 35-month-old children. Pediatrics. 2007;119(Supp1):S4–S11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bardenheier BH, Yusuf HR, Rosenthal J, et al. Factors associated with underimmunization at 3 months of age in four medically underserved areas. Public Health Reports. 2004;119(5):479–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bates AS, Fitzgerald JF, Dittus RS, Wolinsky FD. Risk factors for underimmunization in poor urban infants. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1994;272(14):1105–1110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bates AS, Wolinsky FD. Personal, financial, and structural barriers to immunization in socioeconomically disadvantaged urban children. Pediatrics. April 1998;101(4 Pt 1):591–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fiks AG, Alessandrini EA, Luberti AA, Ostapenko S, Zhang X, Silber JH. Identifying factors predicting immunization delay for children followed in an urban primary care network using an electronic health record. Pediatrics. December 2006;118(6):e1680–1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luman ET, McCauley MM, Shefer A, Chu SY. Maternal characteristics associated with vaccination of young children. Pediatrics. 2003;111(5):1215–1218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ross A, Kennedy AB, Holt E, Guyer B, Hou W, Hughart N. Initiating the first DTP vaccination age-appropriately: a model for understanding vaccination coverage. Pediatrics. 1998;101(6):970–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wiecha J, Gann P. Does maternal prenatal care use predict infant immunization delay? Family Medicine. 1994;26(3):172–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nurss JR, Parker RM, Williams MV, Baker DW. TOFHLA: Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults. Second ed. Camp Snow, Carolina North: Peppercorn Books & Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Notice to readers: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) for the control and elimination of mumps. MMWRMorb Mortal Wkly Rep. June 9 2006;55(22):629–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kolasa MS, Chilkatowsky AP, Clarke KR, Lutz JP. How complete are immunization registries? The Philadelphia story. AmbulPediatr. Jan-February 2006;6(1):21–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chaves SS, Zhang J, Civen R, et al. Varicella disease among vaccinated persons: clinical and epidemiological characteristics, 1997–2005. J Infect Dis. March 1 2008;197 Suppl 2:S127–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feemster KA, Spain CV, Eberhart M, Pati S, Watson B. Identifying infants at increased risk for late initiation of immunizations: maternal and provider characteristics. Public Health Rep. Jan-February 2009;124(1):42–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kolasa MS, Chilkatowsky AP, Stevenson JM, et al. Do laws bring children in child care centers up to date for immunizations? Ambul Pediatr. May-June 2003;3(3):154–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fairbrother G, Hanson KL, Friedman S, Butts GC. The impact of physician bonuses, enhanced fees, and feedback on childhood immunization coverage rates. Am J Public Health. February 1999;89(2):171–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fairbrother G, Siegel MJ, Friedman S, Kory PD, Butts GC. Impact of financial incentives on documented immunization rates in the inner city: results of a randomized controlled trial. Ambul Pediatr. Jul-August 2001;1(4):206–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brenner RA, Simons-Morton BG, Bhaskar B, Das A, Clemens JD. Prevalence and predictors of immunization among inner-city infants: a birth cohort study. Pediatrics. September 2001;108(3):661–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wood D, Donald-Sherbourne C, Halfon N, et al. Factors related to immunization status among inner-city Latino and African-American preschoolers. Pediatrics. 1995;96(2):295–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fiks AG, Grundmeier RW, Biggs LM, Localio AR, Alessandrini EA. Impact of clinical alerts within an electronic health record on routine childhood immunization in an urban pediatric population. Pediatrics. October 2007;120(4):707–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]