Abstract

Nicotine has acute pain-relieving properties and tobacco smokers often report using cigarettes to cope with pain. The proportion of smokers using menthol cigarettes has increased in recent years and there is reason to suspect that menthol may enhance the analgesic effects of nicotine. Up to 90% of African American smokers report using menthol cigarettes, and African Americans tend to report more severe pain and greater difficulty quitting. Yet no known research has examined the relationship between menthol cigarette use and pain reporting. Thus, the goal of the current study was to test associations between menthol (vs. non-menthol) cigarette use and pain among a sample of African American smokers. Current daily cigarette smokers (N = 115; 70% male; Mage = 47.05; MCPD = 15.2) were recruited to participate in a smoking cessation study. These data were collected at the baseline session. Daily menthol (vs. non-menthol) cigarette use was associated with lower current pain intensity, lower average and worst pain over the past three months, and less pain-related physical impairment over the past three months. This study demonstrates that menthol (vs. non-menthol) cigarette use is associated with less pain and pain-related functional interference among African American smokers seeking tobacco cessation treatment. Future research is needed to examine the potential acute analgesic effects of menthol vs. non-menthol cigarette use, examine temporal covariation between menthol cigarette use and pain reporting, and test whether pain-relevant processes contribute to the maintenance of menthol cigarette smoking among those with and without chronic pain.

Keywords: menthol, tobacco, nicotine, pain, African Americans

INTRODUCTION

Cigarette smoking and pain are both prevalent and costly health problems (Nahin, 2015; WHO, 2017), and there is evidence of covariation between tobacco use and pain intensity (Volkman et al., 2015). Factors that may influence the relationship between cigarette use and pain have received increasing empirical and clinical interest (Ditre, Langdon, Kosiba, Zale, & Zvolensky, 2015; Goesling et al., 2015; Shen et al., 2018). There is reason to suspect that menthol (vs. non-menthol) cigarette smoking may be associated with reduced pain reporting among daily smokers, and this is important to investigate given that menthol is the most common tobacco additive (Giovino et al., 2015), and the use of menthol cigarettes has increased in recent years (Giovino et al., 2015; Villanti et al., 2016).

Nicotine has been shown to confer acute pain-inhibitory (analgesic) effects (Ditre, Heckman, Zale, Kosiba, & Maisto, 2016) that are likely mediated via activation of α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) (Shi, Weingarten, Mantilla, Hooten, & Warner, 2010). Smokers who use menthol (vs. non-menthol) cigarettes exhibit a greater density of α4β2 nAChRs in the brain (Brody et al., 2013), which may lead to enhanced sensitivity to nicotine, and a subsequent increase in nicotine-induced analgesia (Alsharari et al., 2015; Brody et al., 2013). Menthol cigarette smokers also tend to exhibit impaired nicotine metabolism, which can increase exposure to nicotine (Benowitz, Herrera, & Jacob, 2004), and has been shown to lengthen the duration of nicotine-induced pain reduction (antinociception) in mouse models (Alsharari et al., 2015).

Up to 90% of African American adult smokers use menthol cigarettes, compared to just 26% of White smokers (Giovino et al., 2015; Lawrence et al., 2010), and as few as 5% of African American smokers ever switch from menthol to non-menthol cigarettes (Rath et al., 2015). As a result, African American smokers consume a disproportionate number of all menthol cigarettes produced in the United States (19.1%; SAMHSA, 2012). African American smokers are also at higher risk for pain conditions (compared to non-Hispanic White smokers) and evince lower pain tolerance (Meints, Stout, Abplanalp, & Hirsh, 2017; Sheffield, Biles, Orom, Maixner, & Sheps, 2000). Furthermore, data from a clinical pain sample indicated that a large percentage (63.2%) of African American tobacco users endorsed smoking cigarettes to cope with their pain (Patterson et al., 2012). Yet, no studies to date have tested between-group differences in pain reporting as a function of menthol (vs. non-menthol) cigarette use among African American smokers. This gap in knowledge hinders efforts to explicate the clinical significance of associations between menthol cigarette use and the experience of pain among this understudied group of smokers.

The aim of the current study was to conduct the first test of self-reported pain intensity/severity and pain-related physical impairment as a function of menthol cigarette use in a sample of treatment-seeking African American smokers. We hypothesized that menthol (compared to non-menthol) cigarette use would be associated with lower current pain intensity. We also predicted that menthol cigarette use would be associated with lower average and worst pain severity, and less pain-related physical impairment over the last three months. Current and past-three-month assessment periods are consistent with clinical recommendations for evaluation of pain and limit the potential for recall bias (Treede et al., 2015; Turk & Melzack, 2011).

METHODS

Participants

Participants (N = 115) were recruited from Houston, Texas between 2013 and 2016. Following written informed consent, participants completed a diagnostic interview and a computerized assessment protocol. The current investigation is based on secondary analyses of baseline (pre-treatment) data obtained from a larger ongoing smoking cessation trial (Zvolensky et al., 2017). Inclusionary criteria for the current study included smoking a minimum of 6 CPD (for at least 1 year) and reporting motivation to quit smoking (i.e., scoring 5 or greater on a 0–10 Likert scale). Identifying as African American was not an inclusion criteria for this study. Participants were excluded if they reported using other tobacco products besides cigarettes, reported suicidality or psychotic symptoms consistent with a current psychotic disorder, were using any pharmacotherapy or enrolled in psychotherapy for smoking cessation, were unwilling to cease use of benzodiazepines or other fast-acting anxiolytics. Participants were also excluded if they reported concurrent psychotherapy initiated in the past three months or ongoing anxiety psychotherapy, or reported current or intended participation in a concurrent substance abuse treatment. Participants were not excluded based on other drug use. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Houston (Protocol number 11468–02/Augmenting Smoking Cessation with Transdiagnostic CBT for Smokers with Anxiety). Each participant was compensated $20 for completing the baseline portion of the study.

Measures

Sociodemographic and Tobacco Use Characteristics.

Sociodemographic and tobacco use characteristics including age, sex, race, average smoking frequency, and menthol cigarette use were based on self-report during the baseline assessment.

Psychiatric Disorders.

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2002) was used to assess for the presence of past-month, Axis-I psychiatric disorders. The SCID-I was administered by trained doctoral students under the supervision of a clinical psychologist.

Cigarette Dependence.

The Heaviness of Smoking Index (HSI; Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, Rickert, & Robinson, 1989) was used to index cigarette dependence, and is comprised of two items: (1) cigarettes smoked per day (CPD), and (2) time to first cigarette after waking. The HSI has demonstrated excellent sensitivity and specificity (Huang, Lin, and Wang 2008), and good reliability over time (Borland, Yong, O’Connor, Hyland, & Thompson, 2010). The HSI is highly correlated with the widely used Fagerstrom Test for Cigarette Dependence (FTCD), and avoids potential confounds associated with additional items included in the FTCD (Chabrol, Niezborala, Chastan, & de Leon, 2005; Fagerstrom, Russ, Yu, Yunis, & Foulds, 2012).

Pain Intensity, Severity, and Pain-Related Interference.

The Graded Chronic Pain Scale (GCPS; Von Korff, Ormel, Keefe, & Dworkin, 1992) was administered to index current pain intensity, and past three month pain intensity and pain-related physical interference), and has been used among those without chronic pain (Smith et al., 1997). Participants rated the intensity of their pain right now and their average and worst pain in the past three months, using separate numerical rating scales from 0 (“No pain”) – 10 (“Pain as bad as could be”). Participants also reported the extent to which pain interfered with their ability to perform daily and work-related activities over the past three months, using separate numerical rating scales from 0 (“No interference”) – 10 (“Unable to carry on activities”).

Data Analytic Plan

Analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics 21 (IBM Corp, 2012). Descriptive statistics were generated to characterize sample demographics and smoking history. Group differences in gender distribution, cigarettes per day, and HSI scores were tested given known gender differences in pain reporting (Fillingim, King, Ribeiro-Dasilva, Rahim-Williams, & Riley, 2009), and the positive association between cigarette use frequency and nicotine exposure (Baker et al., 2007). A series of independent-samples t-tests was used to evaluate mean differences in pain intensity, severity, and pain-related interference between smokers using menthol (vs. non-menthol) cigarettes. Given the different group sizes between menthol (n = 90) and non-menthol (n = 25) smokers, Levene’s test was used to check for equality of variance, and t-test results with adjusted degrees of freedom were reported where indicated. Specifically, Levene’s test indicated unequal group variances with respect to worst pain severity (F=9.73; p=.002), and pain-related interference in daily activities (F=4.56; p=.03). Given unequal group sizes, Hedge’s g was used to calculate effect sizes using a pooled standard deviation.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic and Tobacco Use Characteristics

Participants (70% male; Mage = 47.05, SD = 9.95) endorsed smoking approximately 15 cigarettes per day (MCPD = 15.2; SD = 8.5), and 78% reported smoking mentholated cigarettes. The mean HSI score was 2.90 (SD = 1.03) among menthol smokers, compared to 2.65 (SD = 0.70) among non-menthol smokers, both indicating a moderate level of cigarette dependence (Chaiton, Cohen, McDonald, & Bondy, 2007). Expected group differences were observed between cigarette use frequency categories and smoking dependence scores; F(2) = 14.09, p = < .001). Specifically, light smokers reported a mean HSI score of 2.19 (SD = 0.87), followed by moderate-heavy smokers (2.71, SD = 0.87), and heavy smokers (3.4, SD = 0.9). In terms of criterion variables, moderate-heavy smokers evinced lower pain-related interference (M = 1.77, SE = 0.47) that either light (M = 3.84, SE = 0.69) or heavy smokers (M = 3.27, SE = 0.48); (p = .01, and p = .03, respectively). There were no other statistically significant differences in criterion variables as a function of sociodemographic or tobacco use variables. In addition, no differences in cigarette dependence scores were observed among those who reported a “0” vs. a higher score on any of these measures (ps = .37 – .89). Full sample characteristics organized by menthol vs. non-menthol use status are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

|

Non-Menthol Smokers (N = 25) N (%) |

Menthol Smokers (N = 90) N (%) |

|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 20 (80) | 60 (66.7) |

| Male | 5 (20) | 30 (33.3) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 1 (4.2) | 2 (2.2) |

| Education | ||

| Partial high school | 3 (12.5) | 9 (10) |

| High school graduate | 12 (50) | 33 (36.7) |

| Partial college | 6 (25) | 26 (28.9) |

| Graduate School | 3 (12.5) | 9 (10) |

| College graduate | 0 (0) | 8 (8.9) |

| Junior High School | 0 (0) | 4 (4.4) |

| Less than 7 years of school | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) |

| Income | ||

| $0 - $4,999 | 14 (56) | 28 (30.8) |

| $5,000 - $9,999 per year | 4 (16) | 12 (13.2) |

| $10,000 - $14,999 per year | 1 (4) | 10 (11) |

| $15,000 - $24,999 per year | 1 (4) | 12 (13.2) |

| $25,000 - $34,999 per year | 2 (8) | 7 (7.7) |

| $35,000-$49,999 per year | 1 (4) | 3 (3.3) |

| $50,000 - $74,999 per year | 0 (0) | 3 (3.3) |

| ≥ 75,000/year per year | 1 (4) | 2 (2.2) |

| Cigarette Use Frequency*† | ||

| Light (<10/day) | 5 (27.8) | 17 (19.5) |

| Moderate-Heavy (10–15/day) | 2 (11.1) | 40 (46) |

| Heavy (>15/day) | 11 (44) | 30 (34.5) |

| Cannabis Use1 | ||

| Yes | 15 (71.4) | 51 (59.3) |

| No | 6 (28.6) | 35 (40.7) |

| Past-Month Psychiatric Disorder4 | ||

| Yes | 14 (56) | 67 (74.4) |

| No | 11 (44) | 23 (25.6) |

| M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Age | 47.1 (9.7) | 48.1 (10.05) |

| Number of years smoked | 27.78 (13.76) | 25.31 (12.09) |

| Number of cigarettes per day | 17.56 (12.18) | 14.75 (8.84) |

| Cigarette dependence2 | 2.65 (0.70) | 2.9 (1.03) |

| Alcoholic drinks per day3 | 2.91 (2.6) | 2.75 (2.36) |

Note. 0 = Female, 1 = Male.

Do you currently or have you ever smoked cannabis? (yes/no),

Heaviness of Smoking Index (HSI) scores.

In the last year, how many days per week did you drink alcohol on average?,

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-1). Valid percentages reported as a small subset of participants were missing demographic data.

chi-square test of group differences interpreted as unreliable given expected cell count less than 5.

p < .05

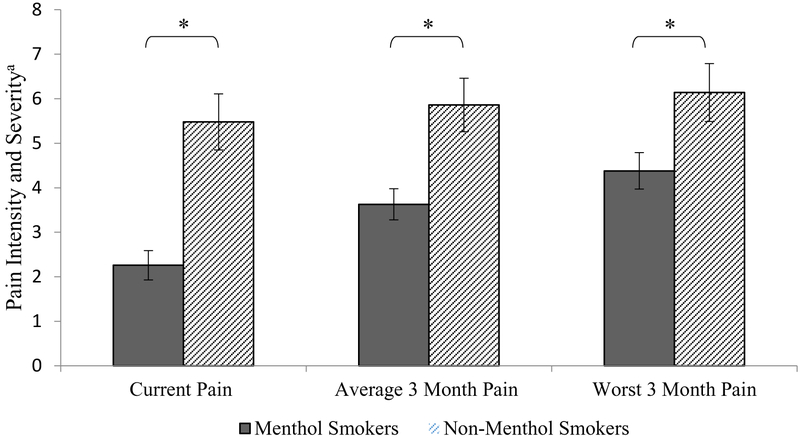

Current Pain Intensity

Analyses revealed that menthol smokers reported lower current pain intensity (M = 2.76, SE = 0.33) than non-menthol smokers (M = 5.48, SE = 0.63), t(106) = 3.67, p < .001; CI: 1.25 – 4.19; corresponding to a large effect size (Hedge’s g = .89). This result is depicted in Figure 1. Reporting a current pain intensity of “0” was more common among menthol smokers (41.4%), compared to non-menthol smokers (9.5%; chi-square = 8.87, p = < .01).

Figure 1.

Pain intensity and severity by menthol cigarette use. Unadjusted mean pain ratings (with standard errors) as a function of menthol vs. nonmenthol cigarette use. Note. aGraded Chronic Pain Scale (GCPS), Range for each variable: 0–10, *p < .05.

Past 3-Month Pain Intensity

Menthol smokers also reported lower average pain severity over the past 3 months (M = 3.63, SE = 0.35), compared to non-menthol smokers (M = 5.86, SE = 0.60), t(106) = 2.96, p = .004, CI: 0.74–3.75; corresponding to a large effect size (Hedge’s g = .71). Menthol smokers also reported lower pain at its worst over the past 3 months (M = 4.38, SE = 0.41), compared to non-menthol smokers (M = 6.14, SE = 0.65), t(38.16) = 2.29, p = .027, CI: 0.21 – 3.32; corresponding to a medium effect size (Hedge’s g = .47; see Figure 1). Reporting an average pain intensity of “0” was more common among menthol smokers (32.6%), compared to non-menthol smokers (9.5%; chi-square = 5.3, p = .02).

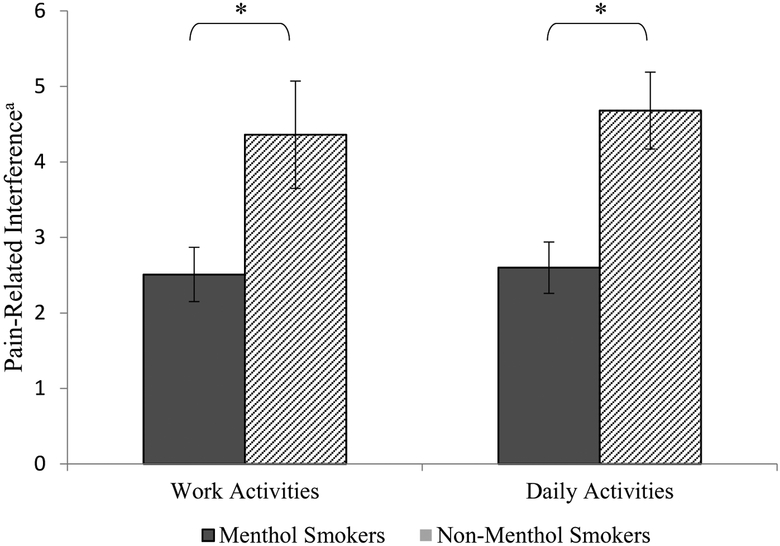

Past 3-Month Pain-Related Interference

Analyses further revealed that menthol smokers reported less pain-related interference in daily activities over the past 3 months (M = 2.60, SE = 0.34), compared to non-menthol smokers (M = 4.68, SE = 0.51). This difference was statistically significant t(41.39) = 3.40, p = .001, CI: 0.85 – 3.32; corresponding to a medium-large effect size (Hedge’s g = .69). Menthol smokers also reported less interference in work activities over the past 3 months (M = 2.51, SE = 0.36) compared to non-menthol smokers (M = 4.36, SE = 0.71). Once again, this difference was statistically significant t(107) = 2.34, p = .021, CI: 0.28 – 3.43; corresponding to a medium effect size (Hedge’s g = .56; see Figure 2). Reporting a pain interference score of “0” was more common among menthol smokers (range = 46% - 51.7%), compared to non-menthol smokers (range = 4.5% - 22.7%; all ps < .05).

Figure 2.

Pain-related interference by menthol cigarette use. Unadjusted mean pain-related interference ratings (with standard errors) as a function of menthol vs. nonmenthol cigarette use. Note. aGraded Chronic Pain Scale (GCPS), Range for each variable: 0–10, *p < .05.

CONCLUSIONS

This study represents the first empirical test of cross-sectional relations between menthol cigarette use and pain reporting. As hypothesized, treatment-seeking African-American daily smokers who used menthol (vs. non-menthol) cigarettes reported lower current pain intensity and lower pain severity over the past 3 months. Additionally, pain-related physical interference for both daily and work activities was lower among individuals who reported menthol (vs. non-menthol) cigarette use. The medium to large magnitude of observed associations in this study is notable, and suggests that menthol cigarettes smokers may be experiencing clinically meaningful reductions in pain intensity and interference, relative to non-menthol smokers.

There are least two mechanisms that may help to explain the present findings. First, menthol cigarettes (compared to non-menthol cigarettes) may enhance the pain-inhibiting (antinociceptive) properties of nicotine. The activation of α4β2 nAChR receptors during cigarette smoking is thought to mediate the analgesic effects of nicotine (Shi et al., 2010), and animal models have shown that menthol - administered alone or in combination with nicotine - increases the expression of nAChRs (Alsharari et al., 2015). Human models have produced similar results. For example, menthol (vs. non-menthol) cigarette use has been associated with up to 28% greater density of both α4 and β2* nAChR receptors, using positive emission topography (Brody et al., 2013). There is also evidence that menthol may act independently to upregulate these receptors (Henderson et al., 2016), possibly leading to blunted pain signaling (Brody et al., 2013). Menthol has also been shown to increase exposure to nicotine by impairing nicotine metabolism (Benowitz et al., 2004), thus potentially enhancing the bioavailability of nicotine (Wickham, 2015). Although greater exposure to nicotine could result in more pronounced antinociceptive effects, a dose-response relationship between nicotine and relief of either acute or chronic pain has not yet been established (Ditre et al., 2016).

A second possible explanation for the current findings is that menthol (vs. non-menthol) cigarette use has been associated with less frequent smoking (Blot et al., 2011). Smoking less over time could limit exposure to the harmful constituents in tobacco smoke (i.e., carbon monoxide (Clark, Gautam, & Gerson, 1996)), which have been implicated in the development of several clinical pain conditions, including musculoskeletal and headache pain (Aamodt, Stovner, Hagen, Brathen, & Zwart, 2006; Akmal et al., 2004). Current daily smoking rates were not different across menthol vs. non-menthol smokers in the current sample. Yet, there may be utility in examining pain reporting as a function of cumulative (i.e., lifetime) exposure to menthol cigarettes, as this is an important determinant of the accumulative health effects of smoking (USDHHS, 2014).

Menthol cigarette use has been linked with greater risk for cessation failure (Robles, Singh-Franco, & Ghin, 2008), and there is evidence that African American individuals who smoke menthol (vs. non-menthol) cigarettes experience greater difficulty when attempting to quit smoking (Alexander et al., 2016). For example, in a sample of 374 African American smokers receiving empirically-supported cessation treatment, the odds of remaining abstinent up to 6-months post-cessation was lower among those using menthol (vs. non-menthol) cigarettes prior to quitting (Gandhi, Foulds, Steinberg, Lu, & Williams, 2009). Thus, consistent with a reciprocal model of pain and smoking (Ditre, Brandon, Zale, & Meagher, 2011), one potential implication of the current findings is that smokers who come to rely on the acute analgesic effects of nicotine may also come to experience greater difficulty when attempting to quit smoking. Future research should examine the extent to which these processes may be amplified in the context of menthol cigarette use (which may enhance acute nicotine analgesia), and in the presence of co-occurring chronic pain (which would presumably increase the number of occasions to experience acute nicotine analgesia). Indeed, the discontinuation of menthol cigarette smoking could result in greater sensitivity to pain (Ditre, Zale, LaRowe, Kosiba, & De Vita, (in press), which in turn may warrant high-dose or combination nicotine replacement therapy (Hatsukami et al., 2007; Mills et al., 2012).

Several study limitations are worth noting. First, the use of cross-sectional, self-report data precludes causal interpretations and conclusions regarding temporal precedence, and limits testing biochemical markers of cigarette exposure (i.e., carbon-monoxide). It is presently unclear if chronic exposure to menthol cigarette smoking exacerbates or relieves chronic pain. Prospective research will be an important next step to test our hypothesis that smoking menthol cigarettes leads to pain reduction vs. the alternate possibility that those who smoke menthol cigarettes experience less pain or have a greater pain tolerance. Second, although the current sample reported mild-to-moderate past 3-month pain, these participants were not recruited based on pain status and chronic pain-relevant diagnostic data were not collected. Thus, the extent to which these results may generalize to individuals with chronic pain remains unclear. Furthermore, future research might usefully extend the current study by testing the role of painful medical conditions (i.e., rheumatoid arthritis, migraine) and physical activity in relation to menthol cigarette use. Third, although self-report measures are central to human pain assessment (Dansie & Turk, 2013), future work should examine the effects of menthol (vs. non-menthol) cigarette smoking on acute pain using laboratory methods (e.g., quantitative sensory testing) that can provide insight into potential mechanisms of action (Arendt-Nielsen & Yarnitsky, 2009). Finally, although menthol cigarette use is especially common among African American smokers (Fiore et al., 2008; Garrett et al., 2011; Harper & Lynch, 2007), future research would benefit from extending this work to more racially-diverse samples of smokers, and those not seeking treatment for smoking cessation. These studies are needed to test if observed findings are specific to African American smokers.

Public Significance Statement.

This study represents the first empirical test of cross-sectional relations between menthol cigarette use and pain reporting. Results indicated that menthol (vs. non-menthol) cigarette use was associated with less current and past 3-month pain and pain-related functional interference among African American smokers. Future research is needed to examine the potential acute analgesic effects of menthol vs. non-menthol cigarette use, and potential effects on cessation outcomes.

Disclosures and Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse grant R34DA031313-01A1. All authors contributed in a significant way to the manuscript and that all authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aamodt AH, Stovner LJ, Hagen K, Brathen G, & Zwart J (2006). Headache prevalence related to smoking and alcohol use. The Head-HUNT Study. European Journal of Neurology, 13, 1233–1238. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01492.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akmal M, Kesani A, Anand B, Singh A, Wiseman M, & Goodship A (2004). Effect of nicotine on spinal disc cells: a cellular mechanism for disc degeneration. Spine, 29, 568–575. doi: 00007632-200403010-00018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander LA, Trinidad DR, Sakuma KL, Pokhrel P, Herzog TA, Clanton MS, … Fagan P (2016). Why We Must Continue to Investigate Menthol’s Role in the African American Smoking Paradox. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 18 Suppl 1, S91–101. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsharari SD, King JR, Nordman JC, Muldoon PP, Jackson A, Zhu AZ, … Damaj MI (2015). Effects of Menthol on Nicotine Pharmacokinetic, Pharmacology and Dependence in Mice. PLoS ONE, 10, e0137070. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arendt-Nielsen L, & Yarnitsky D (2009). Experimental and clinical applications of quantitative sensory testing applied to skin, muscles and viscera. Journal of Pain, 10, 556–572. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Bolt DM, Smith SS, Kim SY, … Toll BA (2007). Time to first cigarette in the morning as an index of ability to quit smoking: implications for nicotine dependence. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 9 Suppl 4, S555–570. doi: 10.1080/14622200701673480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz NL, Herrera B, & Jacob P 3rd. (2004). Mentholated cigarette smoking inhibits nicotine metabolism. Journal of Pharmacology and Expimental Theraputics, 310, 1208–1215. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.066902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blot WJ, Cohen SS, Aldrich M, McLaughlin JK, Hargreaves MK, & Signorello LB (2011). Lung cancer risk among smokers of menthol cigarettes. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 103, 810–816. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borland R, Yong HH, O’Connor RJ, Hyland A, & Thompson ME (2010). The reliability and predictive validity of the Heaviness of Smoking Index and its two components: findings from the International Tobacco Control Four Country study. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 12 Suppl, S45–50. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody AL, Mukhin AG, La Charite J, Ta K, Farahi J, Sugar CA, … Mandelkern MA (2013). Up-regulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in menthol cigarette smokers. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 16, 957–966. doi: 10.1017/S1461145712001022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabrol H, Niezborala M, Chastan E, & de Leon J (2005). Comparison of the Heavy Smoking Index and of the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence in a sample of 749 cigarette smokers. Addictive Behaviors, 30, 1474–1477. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaiton MO, Cohen JE, McDonald PW, & Bondy SJ (2007). The Heaviness of Smoking Index as a predictor of smoking cessation in Canada. Addictive Behaviors, 32, 1031–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark PI, Gautam S, & Gerson LW (1996). Effect of menthol cigarettes on biochemical markers of smoke exposure among black and white smokers. Chest, 110, 1194–1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dansie EJ, & Turk DC (2013). Assessment of patients with chronic pain. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 111, 19–25. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditre JW, Brandon TH, Zale EL, & Meagher MM (2011). Pain, nicotine, and smoking: Research findings and mechanistic considerations. Psychological Bulletin, 137, 1065–1093. doi: 10.1037/a0025544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditre JW, Heckman BW, Zale EL, Kosiba JD, & Maisto SA (2016). Acute analgesic effects of nicotine and tobacco in humans: a meta-analysis. Pain, 157, 1373–1381. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditre JW, Langdon KJ, Kosiba JD, Zale EL, & Zvolensky MJ (2015). Relations between pain-related anxiety, tobacco dependence, and barriers to quitting among a community-based sample of daily smokers. Addictive Behaviors, 42C, 130–135. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.11.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditre JW, Zale EL, LaRowe LR, Kosiba JD, & De Vita M (in press). Nicotine deprivation increases pain intensity, neurogenic inflammation, and mechanical hyperalgesia among daily tobacco smokers. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerstrom K, Russ C, Yu CR, Yunis C, & Foulds J (2012). The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence as a predictor of smoking abstinence: a pooled analysis of varenicline clinical trial data. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 14, 1467–1473. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillingim RB, King CD, Ribeiro-Dasilva MC, Rahim-Williams B, & Riley JL 3rd. (2009). Sex, gender, and pain: a review of recent clinical and experimental findings. Journal of Pain, 10, 447–485. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, Bailey WC, Benowitz NL, Curry SJ, & Dorfman SF (2008). Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service. May 2008. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, & Williams JB (2002). Structured clinical interviewfor DSM-IV-TR axis I disorders, research version Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Insitute, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi KK, Foulds J, Steinberg MB, Lu SE, & Williams JM (2009). Lower quit rates among African American and Latino menthol cigarette smokers at a tobacco treatment clinic. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 63, 360–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01969.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett BE, Dube SR, Trosclair A, Caraballo RS, Pechacek TF, Centers for Disease, C., & Prevention. (2011). Cigarette smoking - United States, 1965–2008. MMWR Suppl, 60, 109–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovino GA, Villanti AC, Mowery PD, Sevilimedu V, Niaura RS, Vallone DM, & Abrams DB (2015). Differential trends in cigarette smoking in the USA: is menthol slowing progress? Tobacco Control, 24, 28–37. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goesling J, Brummett CM, Meraj TS, Moser SE, Hassett AL, & Ditre JW (2015). Associations between Pain, Current Tobacco Smoking, Depression, and Fibromyalgia Status Among Treatment-Seeking Chronic Pain Patients. Pain Medicine. doi: 10.1111/pme.12747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper S, & Lynch J (2007). Trends in socioeconomic inequalities in adult health behaviors among U.S. states, 1990–2004. Public Health Reports, 122, 177–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatsukami D, Mooney M, Murphy S, LeSage M, Babb D, & Hecht S (2007). Effects of high dose transdermal nicotine replacement in cigarette smokers. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior, 86, 132–139. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.12.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Rickert W, & Robinson J (1989). Measuring the heaviness of smoking: using self-reported time to the first cigarette of the day and number of cigarettes smoked per day. British Journal of Addiction, 84, 791–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson BJ, Wall TR, Henley BM, Kim CH, Nichols WA, Moaddel R,… Lester HA (2016). Menthol Alone Upregulates Midbrain nAChRs, Alters nAChR Subtype Stoichiometry, Alters Dopamine Neuron Firing Frequency, and Prevents Nicotine Reward. J Neurosci, 36, 2957–2974. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4194-15.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence D, Rose A, Fagan P, Moolchan ET, Gibson JT, & Backinger CL (2010). National patterns and correlates of mentholated cigarette use in the United States. Addiction, 105 Suppl 1, 13–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03203.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meints SM, Stout M, Abplanalp S, & Hirsh AT (2017). Pain-Related Rumination, But Not Magnification or Helplessness, Mediates Race and Sex Differences in Experimental Pain. Journal of Pain, 18, 332–339. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2016.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills EJ, Wu P, Lockhart I, Thorlund K, Puhan M, & Ebbert JO (2012). Comparisons of high-dose and combination nicotine replacement therapy, varenicline, and bupropion for smoking cessation: a systematic review and multiple treatment meta-analysis. Annals of Medicine, 44, 588–597. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2012.705016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahin RL (2015). Estimates of pain prevalence and severity in adults: United States, 2012. Journal of Pain, 16, 769–780. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson AL, Gritzner S, Resnick MP, Dobscha SK, Turk DC, & Morasco BJ (2012). Smoking cigarettes as a coping strategy for chronic pain is associated with greater pain intensity and poorer pain-related function. Journal of Pain. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.11.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rath JM, Villanti AC, Williams VF, Richardson A, Pearson JL, & Vallone DM (2015). Patterns of Longitudinal Transitions in Menthol Use Among US Young Adult Smokers. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 17, 839–846. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robles GI, Singh-Franco D, & Ghin HL (2008). A review of the efficacy of smoking-cessation pharmacotherapies in nonwhite populations. Clinical Theraputics, 30, 800–812. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. (2012). Results from the 2011 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. 12–4713 Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Sheffield D, Biles PL, Orom H, Maixner W, & Sheps DS (2000). Race and sex differences in cutaneous pain perception. Psychosomatic Medicine, 62, 517–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen L, Wei K, Chen Q, Qiu H, Tao Y, Yao Q, … Lu Z (2018). Decreased pain tolerance before surgery and increased postoperative narcotic requirements in abstinent tobacco smokers. Addictive Behaviors, 78, 9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Weingarten TN, Mantilla CB, Hooten WM, & Warner DO (2010). Smoking and pain: Pathophysiology and clinical implications. Anesthesiology, 113, 977–992. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181ebdaf900000542-201010000-00033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BH, Penny KI, Purves AM, Munro C, Wilson B, Grimshaw J, … Smith WC (1997). The Chronic Pain Grade questionnaire: validation and reliability in postal research. Pain, 71, 141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treede RD, Rief W, Barke A, Aziz Q, Bennett MI, Benoliel R, … Wang SJ (2015). A classification of chronic pain for ICD-11. Pain, 156, 1003–1007. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turk DC, & Melzack R (2011). The measurement of pain and the assessment of people experiencing pain In Turk DC & Melzack R (Eds.), Handbook of pain assessment (3rd ed., pp. 3–18). New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- USDHHS. (2014). The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. [Google Scholar]

- Villanti AC, Mowery PD, Delnevo CD, Niaura RS, Abrams DB, & Giovino GA (2016). Changes in the prevalence and correlates of menthol cigarette use in the USA, 2004–2014. Tobacco Control, 25, ii14–ii20. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkman JE, DeRycke EC, Driscoll MA, Becker WC, Brandt CA, Mattocks KM, … Bastian LA (2015). Smoking Status and Pain Intensity Among OEF/OIF/OND Veterans. Pain Medicine, 16, 1690–1696. doi: 10.1111/pme.12753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Korff M, Ormel J, Keefe FJ, & Dworkin SF (1992). Grading the severity of chronic pain. Pain, 50, 133–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2017: monitoring tobacco use and prevention policies. Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham RJ (2015). How Menthol Alters Tobacco-Smoking Behavior: A Biological Perspective. Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, 88, 279–287. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Bakhshaie J, Norton PJ, Smits JAJ, Buckner JD, Garey L, & Manning K (2017). Visceral sensitivity, anxiety, and smoking among treatment-seeking smokers. Addictive Behaviors, 75, 1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.06.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]