Abstract

Objective

Administration of FGF21 and FGF21 analogues reduce body weight; improve insulin sensitivity and dyslipidemia in animal models of obesity and in short term clinical trials. However potential adverse effects identified in mice have raised concerns for the development of FGF21 therapeutics. Therefore, this study was designed to address the actions of FGF21 on body weight, glucose and lipid metabolism and importantly its effects on bone mineral density (BMD), bone markers, and plasma cortisol in high-fat fed obese rhesus macaque monkeys.

Methods

Obese non-diabetic rhesus macaque monkeys (five males and five ovariectomized (OVX) females) were maintained on a high-fat diet and treated for 12 weeks with escalating doses of FGF21. Food intake was assessed daily and body weight weekly. Bone mineral content (BMC) and BMD were measured by DEXA scanning prior to the study and on several occasions throughout the treatment period as well as during washout. Plasma glucose, glucose tolerance, insulin, lipids, cortisol, and bone markers were likewise measured throughout the study.

Results

On average, FGF21 decreased body weight by 17.6 ± 1.6% after 12 weeks of treatment. No significant effect on food intake was observed. No change in BMC or BMD was observed, while a 2-fold increase in CTX-1, a marker of bone resorption, was seen. Overall glucose tolerance was improved with a small but significant decrease in HbA1C. Furthermore, FGF21 reduced concentrations of plasma triglycerides and very low density lipoprotein cholesterol. No adverse changes in clinical chemistry markers were demonstrated, and no alterations in plasma cortisol were observed during the study.

Conclusion

In conclusion, FGF21 reduced body weight in obese rhesus macaque monkeys without reducing food intake. Furthermore, FGF21 had beneficial effects on body composition, insulin sensitivity, and plasma triglycerides. No adverse effects on bone density or plasma cortisol were observed after 12 weeks of treatment.

Introduction

Fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) belongs to the FGF19 subgroup of endocrine FGFs [1, 2] and is highly expressed in and secreted from the liver [3, 4]. The metabolic action of FGF21 is mediated through receptors in the adipose tissue and [5] the central nervous system (CNS) [6]. Since the identification of FGF21 as a metabolic regulator by Kharitonenkov in 2005 [7], many groups have studied the anti-diabetic and anti-obesity effect of FGF21 and analogues in various animal models of diabetes and obesity [8–11]. The anti-diabetic and anti-obesity effects of FGF21 have also led to clinical testing of stable protracted FGF21 analogues [10, 12].

The anti-obesity effect of FGF21 in mice is primarily driven by an increase in energy expenditure [9, 13] via UCP-1. However, UCP1 null mice treated with FGF21 still exhibited reduced body weight but via a reduction in food intake, suggesting multiple pathways in FGF21 mediated weight loss. Most rodent studies with FGF21 have been carried out at room temperature below thermo-neutrality, so therefore it is important to investigate the effects of FGF21 in non-rodent species in order to predict efficacy in humans. FGF21 and analogues have been shown to lower body weight in spontaneously obese cynomolgus monkeys [8, 12, 14] as well as obese diabetic rhesus monkeys [14]. The FGF21-induced weight loss has, in these studies, been driven by a decrease in food intake [12 14, 15].

Several risk factors for clinical development have been observed in mice chronically exposed to FGF21. In 2008, FGF21 was shown to cause hepatic growth hormone (GH) resistance and FGF21 overexpressing mice show low circulating insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) levels and impaired linear growth [16]. Also, adverse effects on bone mineral density (BMD) have been described [17]. FGF21 was further shown to inhibit female reproduction [18], and to increase activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA) [19]. Yet some of the findings may relate to the extensive weight loss, as high-fat feeding restored estrus cycling in the FGF21 overexpressing transgenic mice [20].

This study was designed to evaluate FGF21 pharmacology in high-fat diet-induced obese rhesus macaques. The animals’ diet had a high content of fat and cholesterol and resembled the typical American diet, making these monkeys a relevant model for human obesity [21, 22]. A 12-week dose escalating study was performed with once daily administration of native recombinant human FGF21. In addition to the effects on body weight, food intake, insulin sensitivity, glucose tolerance, and lipid parameters, potential effects of FGF21 therapy on bone mineral content (BMC), BMD, and the HPA axis were measured.

Materials and methods

Animals

Ten rhesus macaque monkeys, (five males and five ovariectomized (OVX) females) 11–22 years of age with a body-weight ranging from 8.3 to 21.1 kg were assigned to the study. The animals were maintained on a HFD for at least 2 years before study start. Animals were pair-housed (one male and one female) in custom designed cages (Carter2 Systems, Inc, Oregon, USA; 2.0 m2 enclosure size, 3.6 m3 enclosure volume, and 1.8 m enclosure height). Shelves and changeable plastic toys were available for the monkeys. The study was approved by Novo Nordisk ethical council and all animal care and procedures were performed according to the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the ONPRC at Oregon Health and Science University as well as Novo Nordisk internal standards for nonhuman primates (NHP) studies.

Diet and food intake measurements

Animals were fed a diet high in sucrose and fat, manufactured by LabDiet (Diet 5L0P, 36.6% of calories from fat, 45.0% calories from carbohydrates, 18.4% from protein; cholesterol 612 ppm; Richmond, Indiana, USA). Food was provided twice daily and food intake was measured after morning and afternoon meals. Animals were also provided a caloric dense peanut butter treat as well as additional enrichment (vegeTables, fruit or popcorn) every day. The animals did not have access to food overnight. Lights were on from 7:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m.

MetFGF21 protein

MetFGF21 is mature human FGF21 carrying an N-terminal methionine added by the E. coli expression host. Production was carried out at Novo Nordisk A/S sites in Denmark and China by methods essentially described in WO2016102562.

Dosing

Following an eight-week period of baseline measurements, animals were treated for 12 weeks with once daily administration of increasing doses of native human FGF21 starting at an initial dose of 10 μg/kg/day, followed by 30, 100, 300, and 1000 μg/kg/day. Nine of the ten animals were maintained on 1000 μg/kg/day for the last 6 weeks, whereas the last animal was maintained on the 300 μg/kg/day for the remainder of the study. The treatment period was followed by a 16-week washout period.

Body composition analysis and glucose tolerance tests

Total body fat, non-fat mass, BMC, and BMD for each animal were measured using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA; Hologic QDR Discovery A; Hologic, Inc., Bedford, MA, USA). After an overnight fast, animals were sedated with 3–5 mg/kg Telazol (Tiletamine HCl/Zolazepam HCl, Fort Dodge Animal Health, Fort Dodge, Iowa, USA) and then supplemented with small doses of Ketamine (5–10 mg/kg, Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, Illinois, USA) to maintain sedation during the procedure and positioned prone on the bed of the scanner. Total body scans (core; collar bones through to hip bones and periphery; limbs) were performed on each animal. QDR software (Hologic) was used to calculate body composition, BMC, and BMD.

Immediately following the DEXA scans, glucose tolerance was assessed by an intravenous glucose tolerance test (IVGTTs) pre-dose, at 12 weeks of treatment and after washout. Animals were administered a glucose bolus (50% dextrose solution) at a dose of 0.6 g/kg via the saphenous vein. Baseline blood samples were obtained prior to the infusion, and 500 μl blood samples were taken at 1, 3, 5, 10, 20, 40, and 60 min after infusion via the contralateral saphenous vein. Blood glucose was measured immediately using a hand-held glucometer (OneTouch Ultra2 Blood Glucose Monitor; LifeScan, Milpitas, CA). Plasma insulin and c-peptide levels were assayed by the ONPRC/OHSU Endocrine Services Laboratory using a Cobas 411 (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Glucose area under the curve (gAUC), insulin area under the curve (iAUC) and c-peptide area under the curve (cAUC) were calculated using T = 0 as baseline. To differentiate between different fat stores body composition was measured by MRI (3T Tim Trio, Siemens) from a cross sectional view from the thigh (muscle) and the abdomen (1 inch above umbilicus). Animals were anesthetized during the procedure using isoflurane.

Tissue biopsies and gene expression

Subcutaneous adipose tissue biopsies were collected under isoflurane anesthesia at baseline, after 12 weeks of treatment and after washout (this procedure was performed immediately prior to the MRI scanning). Biopsies were collected from an incision site in the abdomen, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C.

Total RNA isolation, reverse transcription, and quantitative PCR were performed and analyzed as described previously [23]. Real-time mRNA expression of UCP-1 and leptin was normalized to 18 s, and data were analyzed using the Pfaffl method as described previously [24].

Analysis of plasma samples

Blood was collected in EDTA vacutainers (K3-EDTA 8mM, BD BioScience, San Jose, CA, USA) and in the presence of HALT protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Fisher, Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and DPP4 inhibitor (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) and plasma was collected by centrifugation of the samples at 2400 × g at 4 °C for 20 min. The hormones concentrations were measured by the Endocrine Services Laboratory at ONPRC using the following assays: Leptin (Human Leptin RIA, EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), adiponectin (HMW & Total Adiponectin ELISA assay from ALPCO, Salem, NH, USA), insulin growth factor binding protein-2 (IGFBP-2), IGF-1 (ELISA assay from R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), CTX-1 (Serum CrossLaps, ELISA assay from Immunodiagnostic systems, Boldon, UK), osteocalcin (Immunochemiluminescence assay, Roche cobas e411, Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA), and myostatin (ELISA assay from R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Blood for thyroid hormone analysis was collected in lithium heparin coated tubes, and plasma analyzed for T3 and T4 (Immunochemiluminescence assay, Roche cobas e411, Roche Diagnostics), FGF21 levels were determined in EDTA plasma using the FGF21 human ELISA assay (BioVendor Research and Diagnostic Products, Asheville, NC, USA).

Lipoprotein analysis

Lipoprotein levels were analyzed by the Lipid, Lipoprotein and Atherosclerosis Laboratory at Wake Forest. Lipoprotein classes were separated by gel filtration chromatography. An aliquot of plasma containing between 10–20 μg of plasma cholesterol was injected onto a Superose 6 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK) using a Hitachi Elite La Chrome system with an auto-sampler (Hitachi High Technologies America Inc., Schaumburg, IL, USA). After lipoprotein separation on the column, effluent was mixed during online elution with Pointe Scientific Total Cholesterol Reagent. Lipoprotein classes were determined by dropline analysis with individual lipoprotein cholesterol peaks being separately evaluated. Lipoprotein class cholesterol percentages were calculated as a percentage of total plasma cholesterol concentrations.

Statistics

Data (except MRI and sex hormones) are presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed with one-way ANOVA repeated measurements. The analysis was followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test comparing different periods during treatment or after treatment (washout) to predose. In Fig. 1c statically differences are calculated from percentage change in weight relative to baseline. MRI and sex hormone data were analyzed with a paired t-test. Significance level was P < 0.05. Data were analyzed using the software GraphPad Prism version 6.4 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA 92037 USA).

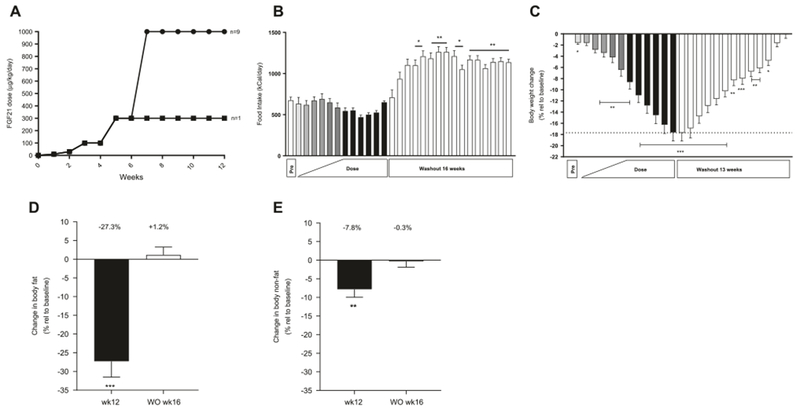

Fig. 1.

Effect of FGF21 treatment on food intake, body weight and body composition. Dosing regimen (a) ∎ one female monkey • remaining nine monkeys (four females and five males), food intake (b), body weight change in % (c), changes in body fat (d), and non-fat mass (e) in obese rhesus monkeys treated with FGF21 once daily for 12 weeks, n = 10. Data are means ± SEM, ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 compared to predose (pre)

Results

Ten (five males and five OVX females) rhesus macaques on HFD were treated with recombinant human FGF21 for 12 weeks according to the study design shown in Fig. 1a. Initially a very low dose of 10 μg/kg/day human FGF21 was administered for one week and after 6 weeks of increasing titration; a dose of 1 mg/kg was reached. As the study was not only designed to look for metabolic endpoints but also potential adverse effects on bone and plasma cortisol, 1 mg/kg was dosed daily for the last 6 weeks. However, one female monkey was very sensitive to the FGF21 treatment and experienced a profound weight loss; therefore, the FGF21 dose was not further increased in this animal after reaching a level of 300 μg/kg/day. Food intake was measured daily and no significant changes were observed during the treatment period. A trend towards reduced food intake was observed at the 1 mg/kg/day dose level but the difference was not significant (Fig. 1b). Alternatively, during washout the food consumption was enhanced compared to pre-dosing. A significant body weight reduction was observed after 1 week of dosing (p = 0.0125) and after 12 weeks of dosing the obese rhesus macaques had lost 17.6 ± 1.6% of their body weight (Fig. 1c). There were no significant differences between the magnitudes of weight loss observed in male versus female monkeys. During the washout period the body weight slowly increased and reached baseline levels at 13 weeks (Fig. 1c) after the last dose. The data clearly indicate that the weight loss in these monkeys was not caused by a decrease in food intake, but presumably due to an increase in energy expenditure. No changes in fecal or urine excretions were observed during the FGF21 treatment.

Native FGF21 has a half-life of 4.3 h after subcutaneous dosing in cynomolgus monkeys [8] and 1 mg/kg FGF21 led to a FGF21 plasma concentration of approx. 950 ng/ml (~50 nM) 24 h after dosing (Suppl. data Fig. 1). Plasma FGF21 returned to baseline levels 5 weeks after the end of treatment but as this was the first time point exposure was measured after the last dose, the baseline level may have been reached earlier. The applied ELISA cannot distinguish between the endogenous rhesus monkey FGF21 and the administrated human FGF21. However, the endogenous FGF21 levels in obese rhesus monkeys are approx. 500 pg/ml [22] and therefore more than 99.9% of the measured plasma FGF21 is exogenous human FGF21 at the 1 mg/kg dose.

The body weight reduction was primarily due to loss of fat mass which was decreased 27.3 ± 4.2% (Fig. 1d). Concomitantly, a decrease of 7.8 ± 2.1% in non-fat body mass was observed in response to treatment (Fig. 1e). Fat mass and non-fat mass returned to pre-treatment levels 16 weeks after end of dosing. An MRI scan showed that the weight loss in both females and males was greatest in the area of intra-abdominal fat which was reduced by 38.5 ± 7.9% (Suppl. Table 1). Subcutaneous abdominal fat and retroperitoneal fat areas were also significantly reduced by 23.4 ± 4.0% and 33.3 ± 8.2%, respectively. The subcutaneous leg fat area and the intramuscular fat area were also both significantly reduced (Suppl. Table 1). Moreover, the thigh muscle area was reduced by 14.5 ± 4.3% as shown in Suppl. Table 1.

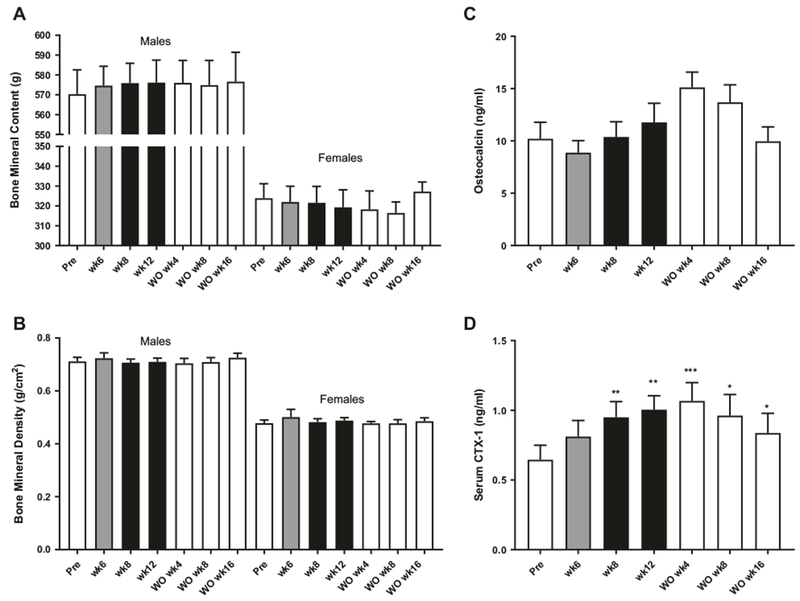

To determine if FGF21 had any adverse effects on bone density BMC and BMD were measured utilizing DEXA imaging before (pre) treatment as well as after 6, 8, and 12 weeks of treatment and during washout. BMC (Fig. 2a) and BMD (Fig. 2b) were not altered during the 12 weeks of treatment or during the washout period. To further investigate the potential impact on bone health, the bone markers osteocalcin, and CTX-1 were measured. While there was no significant effect on osteocalcin (Fig. 2c), CTX-1 were increased after 8 and 12 weeks of treatment (Fig. 2d) and stayed elevated during the washout period.

Fig. 2.

Effect of FGF21 treatment on bone measurements. Bone mineral content (a), bone mineral density (b), plasma osteocalcin (c), and Serum CTX-1 (d) in obese rhesus monkeys treated with FGF21 once daily for 12 weeks, n = 10. Data are means ± SEM, ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 compared to predose (pre)

Similar to observations in mice [16], FGF21 treatment significantly decreased IGF-1 and increased IGFBP2 (Table 1). Compared to pre-treatment, IGF-1 was significantly increased at the end of washout. No change in plasma T3 was observed, while T4 increased with treatment. Notably, T3 was significantly decreased during the washout period. Total adiponectin, as well as high molecular weight (HMW) adiponectin, suggested as markers for FGF21 activity [25], were also significantly increased with FGF21 treatment (Table 1). The plasma level of myostatin, an inhibitor of skeletal muscle growth [26] was significantly decreased upon treatment (Table 1). A decrease in myostatin is also observed during diet-induced weight loss [27]. Leptin levels remained unchanged (Table 1) despite an almost 18% weight loss, while mRNA expression of leptin in the subcutaneous fat was decreased 3-fold (p = 0.066) while no expression (CT values >34) of UCP-1 was observed neither before nor after treatment with FGF21 (data not shown).

Table 1.

Plasma biochemical markers

| Marker | Pre | wk12 | WO wk16 |

|---|---|---|---|

| IGF-1 (ng/ml) | 300.4 ± 22.2 | 237.4 ± 24.1** | 384.6 ± 30.4** |

| IGFBP-2 (ng/ml) | 145.3 ± 14.9 | 267.5 ± 38.0** | 144.1 ± 11.4 |

| T3 (ng/ml) | 2.39 ± 0.08 | 2.41 ± 0.24 | 1.84 ± 0.08*** |

| T4 (ng/ml) | 3.55 ± 0.24 | 4.69 ± 0.51* | 3.26 ± 0.30 |

| Adiponectin total (ng/ml) | 6564 ± 397 | 12738 ± 2258** | 6120 ± 994 |

| Adiponectin HMW (ng/ml) | 4187 ± 873 | 9211 ± 1993* | 3202 ± 738 |

| Myostatin (pg/ml) | 2901 ± 400 | 1836 ± 221* | 3012 ± 347 |

| Leptin (ng/ml) | 9.13 ± 0.65 | 9.37 ± 2.12 | 9.14 ± 0.46 |

Data are means ± SEM, n = 10

p < 0.001,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.05 compared to predose (pre)

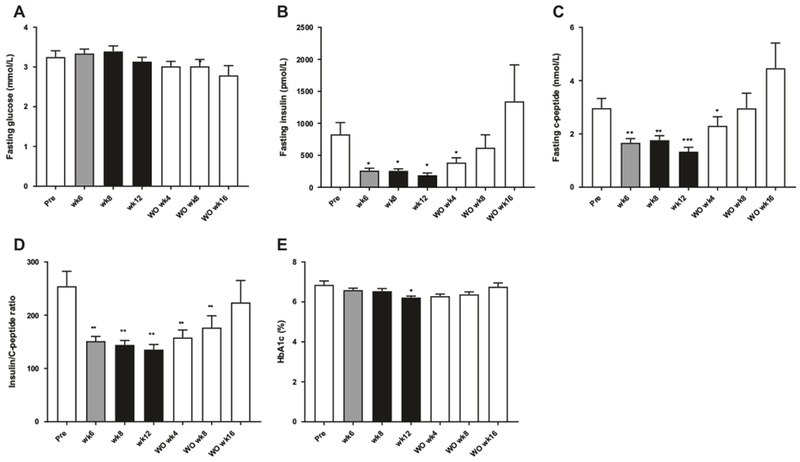

The ten obese monkeys used in the study were not diabetic and fasting blood glucose (Fig. 3a) was unchanged during the study while fasting insulin (Fig. 3b) and c-peptide levels (Fig. 3c) were decreased significantly by FGF21 after 6 weeks of treatment. The insulin/c-peptide ratio was also significantly reduced (P < 0.01, Fig. 3d) by the FGF21 treatment indicating a better hepatic insulin clearance by the liver potentially caused by a decrease in liver fat [28]. HbA1C was significantly lowered (P < 0.05) after 12 weeks of treatment (Fig. 3e).

Fig. 3.

Effect of FGF21 treatment on glucose homeostasis. Fasting levels of glucose (a), insulin (b), and c-peptide (c), c-peptide/insulin ratio and (d) HbA1c (e), n = 10. Data are means ± SEM, ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 compared to predose (pre)

To gain more insight into the effect of FGF21 on insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance IVGTTs were performed. Treatment with FGF21 had no effect on glucose clearance (Suppl. Figure 2A), however, the same rate of glucose clearance was observed at much lower plasma concentration of insulin (Suppl. Figure 2B) and c-peptide (Suppl. Figure 2C) after 12 weeks of dosing. gAUC was not significantly reduced during the treatment period although there was a tendency for a decrease in cAUC and a significantly reduction in iAUC (suppl. Figures 2C, 2D and 2E). During washout, 16 weeks after the last FGF21 dose, the insulin and c-peptide levels were slightly elevated compared to pre-dose. However, at this time point food intake (Fig. 1b) was also significantly increased compared to pre-dose.

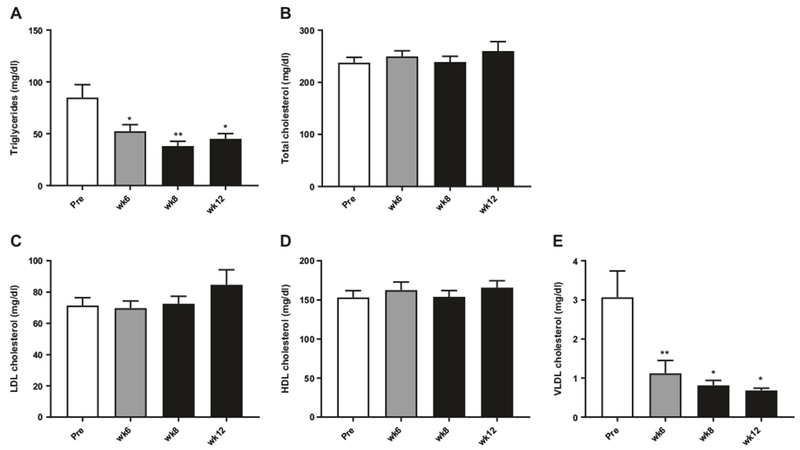

FGF21 has previously been shown to lower plasma lipids in obese diabetic rhesus monkeys [8, 14]. To examine if this is also the case in diet-induced obese rhesus monkey, plasma samples were analyzed before treatment (pre) and after 6, 8, and 12 weeks of treatment. Plasma triglyceride (TG) levels were significantly decreased after 6 weeks of treatment and by 8 and 12 weeks of treatment TGs were reduced by more than 50% (Fig. 4a). The monkeys were fed a high-fat/high-cholesterol diet throughout the study and no significant changes in total plasma cholesterol (Fig. 4b) were observed. The lipoproteins were separated by gel filtration chromatography (FPLC) and the cholesterol levels in low density lipoprotein (LDL) (Fig. 4c), and high density lipoprotein (HDL) (Fig. 4d) were unchanged with treatment, whereas VLDLc levels (Fig. 4e) were decreased at all-time points in agreement with the decreased plasma TGs and observed despite no significant changes in dietary intake.

Fig. 4.

Effect of FGF21 treatment on plasma lipids. Plasma triglycerides (a), total cholesterol (b), LDL cholesterol (c), HDL cholesterol (d), and VLDL cholesterol (e) in obese rhesus monkeys treated with FGF21 once daily for 12 weeks, n = 10. Data are means ± SEM, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 compared to predose (pre). Data are means ± SEM

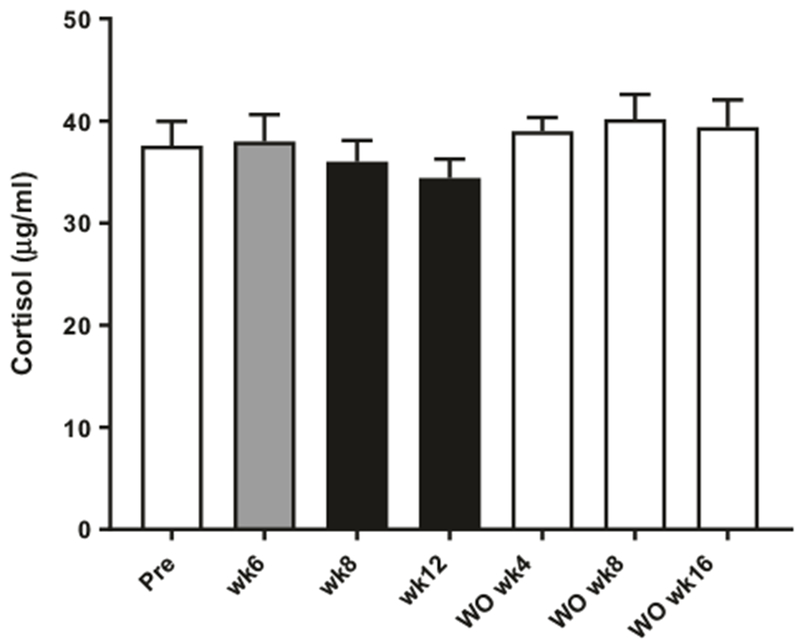

The HPA axis has been described to be activated and plasma corticosterone increased in mice treated with FGF21 [19]. However, no changes in plasma cortisol were observed in the present study (Fig. 5). Likewise, no changes in luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), or testosterone (Suppl. Table 2) were detected. However, the female monkeys were OVX as also indicated by the high plasma LH [29] and therefore these animals were not suited to study effects of FGF21 on changes in female gonadotropins.

Fig. 5.

Effect of FGF21 treatment on plasma cortisol. Plasma cortisol in obese rhesus monkeys measured during treatment with FGF21 once daily for 12 weeks and during washout, n = 10. Data are means ± SEM

Throughout the study clinical chemistry was recorded (Suppl. Table 3). Alanine transaminase (ALT) was significantly decreased with FGF21 treatment, and there was a tendency for a decrease in aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels. Alkaline phosphatase levels were also significantly decreased with treatment. Conversely, blood urea nitrogen levels were significantly increased with FGF21 dosing as expected with the observed reduction in body weight.

This study in obese rhesus macaques confirms that FGF21 can lower body weight in NHPs. However, contrary to previous reports, the weight loss was obtained with no effect on food intake indicating that the weight loss in our study was driven by an increase in energy expenditure. The weight reduction was primarily caused by a decrease in fat mass. No negative effect on bone density was observed during the treatment period, while increases in CTX-1 were noted. Importantly, no increase in cortisol was observed at the tested doses of FGF21.

Discussion

FGF21 and FGF21 analogues have been tested in NHP models [12, 14, 30], but FGF21 has not previously been tested in obese rhesus macaques maintained on a HFD. In the current study, FGF21 decreased body weight without reducing food intake. The weight loss was therefore likely caused by an increase in energy expenditure; however as energy expenditure was not directly measured it cannot be firmly established. In spontaneously obese cynomolgus monkeys a long-acting FGF21 analogue PF-05231023 reduced body weight by decreasing food intake [12, 15]. A pair fed group was included and it could thereby been shown that the loss of body weight was solely driven by a decrease in food intake [12, 15]. Furthermore, in diabetic rhesus monkeys FGF21 analogue LY2405319 lowered body weight by decreasing food intake up to 60%, although high doses of up to 50 mg/kg were used [14]. Utilizing more modest doses, as observed in the current study, clearly demonstrates that FGF21 can induce weight loss independent of changes in food intake in a diet-induced obese NHP model.

This raises the question of how energy expenditure is increased by FGF21 in the NHPs in this study. In diet-induced obese mice, FGF21 lowers body weight without decreasing food intake, and a strong increase in energy expenditure has been observed [9, 13]. In mice an induction of UCP-1 seems to be responsible for the increase in energy expenditure, as shown by an increased UCP-1 expression in the adipose tissues (brown and white) of FGF21 treated mice [9, 31] and with no effect of FGF21 on energy expenditure in UCP-1 knockout mice [32]. Moreover, the FGF21 knockout mice display an impaired adaptive response to cold exposure with lower induction of UCP-1 compared to the wild type litter mates [33]. In our study, no expression of UCP-1 was detected in the subcutaneous white adipocytes, neither before nor after treatment with FGF21. The potential effect of FGF21 on the brown adipose tissue was not assessed, and therefore the brown adipose tissue may have contributed by increasing UCP-1 expression and activity. Moreover, an increase in free T4 was observed while no effect on T3 was seen. In mice, FGF21 increases the expression of 5′-deiodinase type II activity (DIO2) in the brown adipose tissue [9]. DIO2 converts T4 to T3 which enhances BAT thermogenesis [34]. Therefore, a local rise in free T3 in the brown adipose tissue may have contributed to the effects of FGF21 on energy expenditure in our study. In mice, it has furthermore been shown that FGF21-induced energy expenditure in the adipose tissue is centrally mediated by sympathetic nerve activity via the adrenergic system [35] and neuropeptide corticotrophin-releasing factor (CRF) release [19]. In mice an increase in plasma corticosterone has also been observed [6]. However, our data showed no increase in plasma cortisol. Cortisol displays a well-known circadian pattern [36] and a limitation of this study is that cortisol only was measured at single time points. We did however, sample for cortisol at the same time for each measure (8 a.m. fasting and right before next dosing) and importantly, increases in morning plasma cortisol can be observed in NHPs challenged with changes in housing and dominance hierarchy [37]. Therefore, from this study it is unclear how the observed increase in energy expenditure is mediated and if sympathetic nerve activity is increased as has been observed in mice [19, 35]. To clarify if the adrenergic system contributes to the increase in energy expenditure in these monkeys urine norepinephrine could have been measured or a beta-blocker added on top of the FGF21 treatment; but these measurements were out of scope of this study.

Circulating leptin has been shown to be decreased in FGF21 transgenic mice [7]. In the current study, FGF21 did not lower plasma leptin levels, despite a weight loss of almost 18%, which is opposite to the observations in two other studies that showed a decrease in leptin in response to FGF21 treatment of NHPs [12, 14]. However, a threefold decrease in leptin mRNA expression was observed in the subcutaneous white adipose tissue; thus, the lack of a measureable decrease in plasma leptin in response to an 18% loss of body weight may challenge the reliability of the leptin assays used in our study. Interestingly, Talukdar et al. [12] saw only a decrease in leptin on day 8 and not on day 29 despite an approx. 11% decrease in body weight in obese cynomolgus monkeys at day 29 compared to 3% decrease in body weight at day 8. Furthermore, Adams et al. [14] observed significant decrease in plasma leptin at a dose of 50 mg/kg of LY405319.

In the current study, FGF21 treatment did not affect bone density (as measured by BMC or BMD). Wei et al. [15] have found FGF21 to promote bone loss in rodents by a direct effect on PPARγ, while other studies show that FGF21 does not affect bone homeostasis [38]. However, increases in plasma corticosterone [6] as well as decreases in estradiol (female) [18] or IGF-1 [16] can also affect bone turnover. In our study a decrease in IGF-1 was observed while no changes in plasma cortisol was observed. As the female monkeys were OVX no meaningful changes in estradiol could be observed. While 12 weeks treatment of NHP with FGF21 is a relatively short treatment period, McKenzie et al. [39] observed a decrease in BMD of the lumbar spine in humans treated with a low dose of glucocorticoid after 12 weeks of treatment. FGF21 did however, in our study cause an almost 2-fold increase in CTX-1, a marker of bone resorption. These findings resemble the observations in humans treated with an FGF21 analogue (PF-05231023) but as discussed by Takdular et al. [12] changes in body weight will also increase bone turnover and induce changes in plasma bone markers [40]. A weight matched control group is therefore needed to firmly establish if the changes in bone markers are caused by FGF21 treatment or weight loss. The lack of gonads in our female monkeys might furthermore have affected the outcome on bone density.

In conclusion, the study shows that FGF21 can reduce body weight up to 18% during a 12 weeks treatment period in NHP without affecting food intake. This is a clinical meaningful weight loss and future studies will be needed to address if FGF21-induced weight loss in humans is driven by a decrease in food intake or an increase in energy expenditure. No adverse effects on bone density or plasma cortisol were observed in this 12 weeks study, but as bone markers have been shown to be altered in humans treated with a FGF21 analogue, more clinical data are needed to guide future clinical development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Funding This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant P51 OD011092 (to PK and Oregon National Primate Research Center) and Novo Nordisk Grant SRA-11-061 (to PK).

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-018-0080-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Conflict of interest BA, EMS, KMH, TBB, KR, KLG are employers and minor stock holders of Novo Nordisk A/S. DLT, VR, GD, KL, and PK have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Fukumoto S Actions and mode of actions of FGF19 subfamily members. Endocr J. 2008;55:23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fisher FM, Maratos-Flier E. Understanding the physiology of FGF21. Annu Rev Physiol. 2016;78:223–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fon Tacer K, Bookout AL, Ding X, Kurosu H, John GB, Wang L, et al. Research resource: comprehensive expression atlas of the fibroblast growth factor system in adult mouse. Mol Endocrinol 2010;24:2050–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Markan KR, Naber MC, Ameka MK, Anderegg MD, Mangelsdorf DJ, Kliewer SA, et al. Circulating FGF21 is liver derived and enhances glucose uptake during refeeding and overfeeding. Diabetes. 2014;63:4057–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adams AC, Yang C, Coskun T, Cheng CC, Gimeno RE, Luo Y, et al. The breadth of FGF21’s metabolic actions are governed by FGFR1 in adipose tissue. Mol Metab. 2012;2:31–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bookout AL, de Groot MH, Owen BM, Lee S, Gautron L, Lawrence HL, et al. FGF21 regulates metabolism and circadian behavior by acting on the nervous system. Nat Med. 2013;19:1147–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kharitonenkov A, Shiyanova TL, Koester A, Ford AM, Micanovic R, Galbreath EJ, et al. FGF-21 as a novel metabolic regulator.J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1627–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kharitonenkov A, Wroblewski VJ, Koester A, Chen YF, Clutinger CK, Tigno XT, et al. The metabolic state of diabetic monkeys is regulated by fibroblast growth factor-21. Endocrinology. 2007;148:774–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coskun T, Bina HA, Schneider MA, Dunbar JD, Hu CC, Chen Y, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 21 corrects obesity in mice.Endocrinology. 2008;149:6018–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaich G, Chien JY, Fu H, Glass LC, Deeg MA, Holland WL, et al. The effects of LY2405319, an FGF21 analog, in obesehuman subjects with type 2 diabetes. Cell Metab.2013;18:333–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Veniant MM, Komorowski R, Chen P, Stanislaus S, Winters K, Hager T, et al. Long-acting FGF21 has enhanced efficacy in dietinduced obese mice and in obese rhesus monkeys. Endocrinology. 2012;153:4192–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Talukdar S, Zhou Y, Li D, Rossulek M, Dong J, Somayaji V, et al. A long-acting FGF21 molecule, PF-05231023, decreases body weight and improves lipid profile in non-human primates and type 2 diabetic subjects. Cell Metab. 2016;23:427–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu J, Lloyd DJ, Hale C, Stanislaus S, Chen M, Sivits G, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 21 reverses hepatic steatosis, increases energy expenditure, and improves insulin sensitivity in diet-induced obese mice. Diabetes. 2009;58:250–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adams AC, Halstead CA, Hansen BC, Irizarry AR, Martin JA, Myers SR, et al. LY2405319, an engineered FGF21 variant, improves the metabolic status of diabetic monkeys. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e65763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson WC, Zhou Y, Talukdar S, Musante CJ. PF-05231023, a long-acting FGF21 analogue, decreases body weight by reduction of food intake in non-human primates. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2016;43:411–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inagaki T, Lin VY, Goetz R, Mohammadi M, Mangelsdorf DJ, Kliewer SA. Inhibition of growth hormone signaling by the fasting-induced hormone FGF21. Cell Metab. 2008;8:77–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wei W, Dutchak PA, Wang X, Ding X, Wang X, Bookout AL, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 21 promotes bone loss by potentiating the effects of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:3143–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Owen BM, Bookout AL, Ding X, Lin VY, Atkin SD, Gautron L, et al. FGF21 contributes to neuroendocrine control of female reproduction. Nat Med. 2013;19:1153–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Owen BM, Ding X, Morgan DA, Coate KC, Bookout AL, Rahmouni K, et al. FGF21 acts centrally to induce sympathetic nerve activity, energy expenditure, and weight loss. Cell Metab. 2014;20:670–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singhal G, Douris N, Fish AJ, Zhang X, Adams AC, Flier JS, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 21 has no direct role in regulating fertility in female mice. Mol Metab. 2016;5:690–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kievit P, Halem H, Marks DL, Dong JZ, Glavas MM, Sinnayah P, et al. Chronic treatment with a melanocortin-4 receptor agonist causes weight loss, reduces insulin resistance, and improves cardiovascular function in diet-induced obese rhesus macaques. Diabetes. 2013;62:490–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nygaard EB, Moller CL, Kievit P, Grove KL, Andersen B. Increased fibroblast growth factor 21 expression in high-fat diet-sensitive non-human primates (Macaca mulatta). Int J Obes. 2014;38:183–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Comstock SM, Pound LD, Bishop JM, Takahashi DL, Kostrba AM, Smith MS, et al. High-fat diet consumption during pregnancy and the early post-natal period leads to decreased alpha cell plasticity in the nonhuman primate. Mol Metab. 2012;2:10–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holland WL, Adams AC, Brozinick JT, Bui HH, Miyauchi Y, Kusminski CM, et al. An FGF21-adiponectin-ceramide axis controls energy expenditure and insulin action in mice. Cell Metab. 2013;17:790–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McPherron AC, Lawler AM, Lee SJ. Regulation of skeletal muscle mass in mice by a new TGF-beta superfamily member. Nature. 1997;387:83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Milan G, Dalla Nora E, Pilon C, Pagano C, Granzotto M, Manco M, et al. Changes in muscle myostatin expression in obese subjects after weight loss. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2724–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kotronen A, Juurinen L, Tiikkainen M, Vehkavaara S, Yki-Jarvinen H. Increased liver fat, impaired insulin clearance, and hepatic and adipose tissue insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:122–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mello NK, Mendelson JH, Bree MP, Skupny A. Alcohol effects on LH and FSH in ovariectomized female monkeys. Alcohol. 1989;6:147–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stanislaus S, Hecht R, Yie J, Hager T, Hall M, Spahr C, et al. A novel Fc FGF21 with improved resistance to proteolysis, increased affinity towards beta-Klotho and enhanced efficacy in mice and cynomolgus monkeys. Endocrinology. 2017;158:1314–27 10.1210/en.2016-1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muise ES, Souza S, Chi A, Tan Y, Zhao X, Liu F, et al. Down-stream signaling pathways in mouse adipose tissues following acute in vivo administration of fibroblast growth factor 21. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e73011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Samms RJ, Smith DP, Cheng CC, Antonellis PP, Perfield JW 2nd, Kharitonenkov A, et al. Discrete aspects of FGF21 in vivo pharmacology do not require UCP1. Cell Rep. 2015;11:991–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fisher FM, Kleiner S, Douris N, Fox EC, Mepani RJ, Verdeguer F, et al. FGF21 regulates PGC-1alpha and browning of white adipose tissues in adaptive thermogenesis. Genes Dev. 2012;26:271–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Jesus LA, Carvalho SD, Ribeiro MO, Schneider M, Kim SW, Harney JW, et al. The type 2 iodothyronine deiodinase is essential for adaptive thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue. J Clin Invest. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Douris N, Stevanovic DM, Fisher FM, Cisu TI, Chee MJ, Nguyen NL, et al. Central fibroblast growth factor 21 browns white fat via sympathetic action in male mice. Endocrinology. 2015;156:2470–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quabbe HJ, Gregor M, Bumke-Vogt C, Hardel C. Pattern of plasma cortisol during the 24-hour sleep/wake cycle in the rhesus monkey. Endocrinology. 1982;110:1641–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Czoty PW, Gould RW, Nader MA. Relationship between social rank and cortisol and testosterone concentrations in male cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis). J Neuroendocrinol. 2009;21:68–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li X, Stanislaus S, Asuncion F, Niu QT, Chinookoswong N, Villasenor K, et al. FGF21 Is not a major mediator for bone homeostasis or metabolic actions of PPARalpha and PPARgamma agonists. J Bone Miner Res. 2016;32:834–45 10.1002/jbmr.2936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McKenzie R, Reynolds JC, O’Fallon A, Dale J, Deloria M, Blackwelder W, et al. Decreased bone mineral density during lo dose glucocorticoid administration in a randomized, placebo controlled trial. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:2222–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hinton PS, Rector RS, Linden MA, Warner SO, Dellsperger KC, Chockalingam A, et al. Weight-loss-associated changes in bone mineral density and bone turnover after partial weight regain with or without aerobic exercise in obese women. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2012;66:606–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.