Abstract

Background

Over the last 5 years, national policy has encouraged general practices to serve populations of >30 000 people (called ‘working at scale’) by collaborating with other practices.

Aim

To describe the number of English general practices working at scale, and their patient populations.

Design and setting

Observational study of general practices in England.

Method

Data published by the NHS on practices’ self-reports of working in groups were supplemented with data from reports by various organisations and practice group websites. Practices were categorised by the extent to which they were working at scale; within these categories, the age distribution of the practice population, level of socioeconomic deprivation, rurality, and prevalence of longstanding illness were then examined.

Results

Approximately 55% of English practices (serving 33.5 million patients) were working at scale, individually or collectively serving populations of >30 000 people. Organisational models representing close collaboration for the purposes of core general practice services were identifiable for approximately 5% of practices; these comprised large practices, superpartnerships, and multisite organisations. Approximately 50% of practices were working in looser forms of collaboration, focusing on services beyond core general practice; for example, primary care in the evenings and at weekends. Data on organisational models and the purpose of the collaboration were very limited for this group.

Conclusion

In early 2018, approximately 5% of general practices were working closely at scale; approximately half of practices were working more loosely at scale. However, data were incomplete. Better records of what is happening at practice level should be collected so that the effect of working at scale on patient care can be evaluated.

Keywords: England, general practice, health policy, organisational models, primary health care

INTRODUCTION

Over 7000 general medical practices deliver primary health care in England.1 For the last 70 years, the main organisational form of general practice has been the small private partnership of GPs, working in a single business unit, employing other staff.1 When the NHS was established in 1948, practices with a single partner GP were the norm.2 By 2017, practices had grown but were still small: the average number of partner GPs (full or part time) per practice was around three, and the average registered population was about 7000 people.1

Although many practices have collaborated on a voluntary basis (for example, in out-of-hours cooperatives, GP fundholding in the 1990s, and, more formally, in primary care trusts from 2000 until 2013), general practices are organisationally separate, with no routine contractual obligations to work together. NHS England’s Five Year Forward View 3 and the General Practice Forward View 4 promoted further collaboration; the argument was that ‘working at scale’, as this has been called, will promote integrated care, innovation, staff development and organisational resilience, improve access to services, reduce costs, and give primary care a stronger voice.4,5 The NHS Long Term Plan of January 2019 and the new general practice contract for 2019/20206 set out plans for all practices to join primary care networks (PCNs);7 it will be mandatory for all practices to participate.6

Arguably, until early 2019, when detailed guidance on PCNs was published, there had been no specific organisational model for collaborative working between practices in England, with NHS England arguing that the model should ‘depend on local circumstances’.5,8,9 A number of models, with different ambitions and names (for example, mergers, superpartnerships, multisite organisations, multispecialty community providers, primary care homes, federations, networks, and alliances) have been implemented,2,10–14 with many building on older groupings, relationships, and agreements between practices.14 Published surveys have suggested that 60–80% of general practices work in collaboration with others.11,15 One survey provided the names of collaborations, but offered limited information about how these were organised, the closeness of links, or their ambitions.15 Another survey provided more-detailed information, but the response rate was low.11

The size of collaboration proposed by NHS England has been ‘at least’ 30 000–50 000 registered patients,4,6,16 although evidence from the UK and elsewhere that any particular size of primary care organisation is better than any other is very limited.13,14,17–19 Commentators have argued that smaller practices offer better access, have better local focus, and may better meet the needs of some patient groups.20 The Care Quality Commission (the independent regulator of English health services) observed that, although bigger general practices appeared to deliver better care in general, many smaller practices that had a good knowledge of their population, planning of care to meet their needs, and good clinical networks, also delivered outstanding care.21

How this fits in

| There are no firm data on the number of general practices working at scale in England, and which organisational models are being followed. This study found that close collaborations for the purposes of delivering core general practice served approximately 5% of the population and looser collaborations focusing on other services served approximately half of the population. However, data about these were very limited; it is important to ascertain what is happening at practice level to be able to evaluate working at scale. |

In preparation for a study on the impact of working at scale on quality of care, this study aimed to quantify the number of practices working at scale in England. General practice anecdotes suggest that some groups are strong and active, while others have little impact on the practice’s work; as such, this study aimed to build on previous work to develop a comprehensive picture of working at scale, while also attempting to differentiate between those practices working substantively together and those between which the links were weaker.

METHOD

In January 2018, the authors requested data from NHS England regarding the extent of collaborations between practices with which it held contracts. Responding that it did not hold such data, it suggested looking at a survey it had carried out in September 2017 with the aim of understanding whether general practices were offering extended opening hours.22 As well as asking about extended access, the questionnaire asked: ‘What is the name of the group of which your practice is a member; for example, this could be the name of your federation?’ Only one free-text answer to this question was recorded. The dataset provided only the name of the group and no data on the type of group to which the practice belonged. It was not clear which member of the practice had completed the questionnaire. The decision was made, therefore, to seek to enrich the data with information on the type of group, according to the strength of the links between practices.

At this stage, it was not clear how the practices should be categorised. The groups listed in the NHS England survey described themselves using many different terms, such as federations, consortia, provider organisations, networks, alliances, membership organisations, companies, collaborations; or simply as groups with no data on organisational form, purpose, or closeness of links. As such, guidance was sought from other literature, namely:

a systematic review of the impact of collaborations between general practices;13

an online article, in which a list of GP organisations working at scale had been collated by a journalist;15

the websites of NHS England, the British Medical Association, the Royal College of General Practitioners, health policy think tanks the King’s Fund and the Nuffield Trust, and the online magazines Pulse and GP Online.

This exercise also provided the names of other general practice groups; including information on organisational structure, purpose, and closeness of links for some. Using Google, two authors searched online for all the named groups to identify constituent practices and information on organisational form, purpose, and closeness of links. It became clear from this process that three distinct types of practice could be identified:

those working closely at scale for the purposes of core general practice, with shared strategy and risk;

those working loosely at scale to deliver services over and above core general practice only, such as extended access or specialist clinics in the primary care setting; and

those apparently not working with other practices at all (not working at scale).

Working at scale was defined as serving a population of >30 000 people, either as a single practice or as part of a group. Core general practice was defined as in the national contracts between NHS England and practices; namely, the management, during core hours, of patients: ‘... who are, or believe themselves to be: ill with conditions from which recovery is generally expected; terminally ill; or suffering from chronic disease ...’.23,24

A list of all general practices in England was compiled according to whether they were working at scale. Those working at scale were further categorised according to whether they were working together (working closely at scale) for the purposes of core general practice, or for the purposes of services over and above core general practice only (working loosely at scale). Practices with ≤1000 patients were excluded from the dataset as these tend to be either closing down or serve specific populations, such as homeless people. The authors identified:

whether practices were rural or urban;

the proportion of patients aged 0–5 years and ≥75 years;25

the level of socioeconomic deprivation in the lower layer super output area of the main practice surgery postcode (using the Index of Multiple Deprivation);1 and

the proportion who reported a limiting longstanding illness in the GP Patient Survey.26

The authors identified a separate group of university practices serving >30 000 people as those in which ≥30% of the registered population was aged 15–24 years (using demographic data on population served25); it is likely that these would be able to work at this scale as a result of low rates of life-limiting chronic conditions among patients who may be resident in the area for only part of the year, rather than being able to deliver the benefits envisaged by national policy.

Differences in these factors between those practices working at scale for the purposes of core general practice, those working at scale for services over and above core general practice only, and those not working at scale were examined.

RESULTS

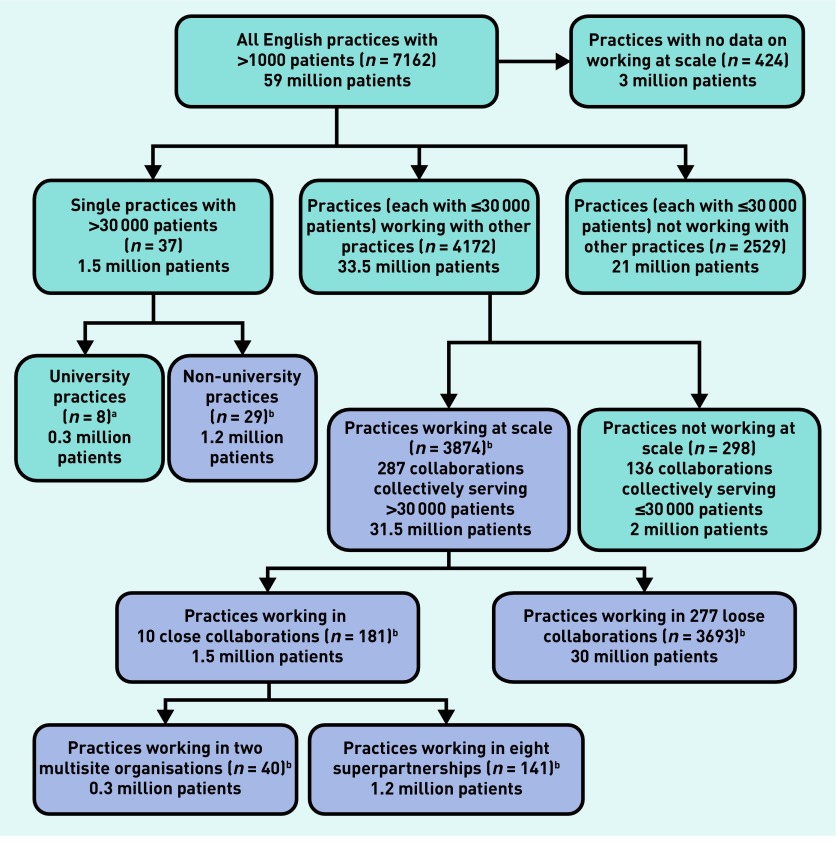

In February 2018, NHS England listed 7162 general practices with >1000 registered patients, each with a unique practice code. Figure 1 shows the number of practices and collaborations of different types, and indicates the total size of the population registered with each type.

Figure 1.

English general practices with >1000 patients, and collaboration types. aPractices with >30 000 patients of whom 30% were aged 15–24 years (assumed to be university practices). bWorking at scale (to serve populations >30 000 patients) as single practices or in collaborations with other practices. All numbers have been rounded so as not to overstate the precision of the estimates. The purple boxes represent practices working at scale.

Of these 7162 practices, 37 (0.5%) were large single practices with >30 000 registered patients, all working from multiple sites across a limited, definable geographical area (although, often there were other practices within the same geographical area that were not part of the large practice). Approximately 1.5 million people (∼2%) were registered with these large practices. Eight were university practices.

Of the 7125 practices with ≤30 000 registered patients, it was possible to find at least some information about group working for 6701 (94%) practices; of these, 4172 (62%) reported working as part of a group.

A total of 298 practices reported working in 136 groups that could not be defined as working at scale; that is, with collective populations of ≤30 000 patients. Approximately 2 million people were registered with these practices.

There were 3874 practices working in groups with collective registered populations of >30 000 patients. Of these, 181 practices were working in 10 groups that could be classified as working in close collaboration for the purposes of core general practice. In these groups, individual practices retained practice contracts with NHS England and a degree of autonomy.14 Nine out of the 10 groups served >50 000 patients, with the largest serving a population of >300 000 people. Some delivered general practice in distant geographical areas; for example, one included practices in Birmingham and Surrey, while another had practices in Leeds, the Midlands, and London. The 10 groups were either superpartnerships (n = 8), in which all GPs were in partnership but individual practices held contracts with the NHS, or multisite organisations (n = 2), in which a parent company held all the individual practice contracts with the NHS on their behalf.14 About 1.2 million people (2% of the English population) were registered with a superpartnership and about 290 000 (0.5%) with a multisite organisation.

None of the other 277 groups working at scale could be defined as a superpartnership or a multisite organisation; it was, therefore, assumed that they represented looser collaborations. Approximately 30 million patients were registered with practices in these groups. For most, no documentation indicating the organisational model could be found and, for 100 groups, no online presence was found. More than 100 groups served populations of >100 000 patients, with the largest serving 500 000 people. Most worked over a defined geographical area and included all, or nearly all, of the practices in that area.

After categorising all the practices, there were 210 practices working closely at scale for the purposes of core general practice (29 practices with >30 000 patients; 40 practices working in two multisite organisations; 141 practices working in eight superpartnerships); 3693 practices working loosely at scale for delivering only services over and above core general practice; and, 2827 practices not working at scale.

For approximately half of the 277 looser collaborations, an organisational website gave some information about the purpose of collaboration. In nearly all cases, this was to provide extended access out of hours; in many, it was also to deliver services that are traditionally provided in the secondary care setting — for example, anticoagulation, dermatology, or diabetes clinics — in other words, services over and above core general practice.

The data on working in groups that the NHS England survey had collected22 may have been unreliable for the purposes of understanding the composition of groups as many practices provided group names that were not cited by any other practices, suggesting that the groups may not actually exist; in some cases, several different names for a group were used by constituent practices.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of practices, classified by the three categories used in this study (working closely at scale: serving a population >30 000 patients for the purposes of core general practice, either as single practice or group made up of several practices; working loosely at scale: working as a group serving a population of >30 000 patients only for the purposes of services over and above core general practice; and not working at scale). Compared with practices not working at scale, practices working at scale were more likely to be urban, had younger populations, slightly fewer patients with long-standing illnesses, and higher levels of socioeconomic deprivation. These differences were all statistically significant. The differences were more marked for practices working at scale to deliver core general practice than those working at scale to deliver only non-core general practice services.

Table 1.

| Not working at scale | Working at scale | University practices | No working at scale data | All practices | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Non-core general practice onlyc | Core general practiced | |||||

| Number of practices, n | 2827 | 3693 | 210 | 8 | 424 | 7162 |

|

| ||||||

| Rurality of practice | ||||||

| Rural, % | 19.1 | 12.1 | 10.0 | 0.0 | 13.0 | 14.9 |

| OR versus not working at scale, 95% CI | 0.6 (0.5 to 0.7) | 0.5 (0.3 to 0.7) | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Level of deprivation | ||||||

| Median IMD scoree 2015 | 20.6 | 22.9 | 30.2 | 21.5 | 23.0 | 22.2 |

| Difference versus not working at scale, 95% CI | 1.9 (1.0 to 2.7) | 5.9 (3.5 to 8.4) | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Characteristics of practice population | ||||||

| Mean aged <5 years, % | 5.5 | 5.7 | 6.1 | 1.8 | 5.7 | 5.7 |

| Difference versus not working at scale, % (95% CI) | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.3) | 0.6 (0.4 to 0.8) | ||||

| Mean aged >75 years, % | 8.3 | 7.4 | 6.6 | 1.7 | 7.3 | 7.7 |

| Difference versus not working at scale, % (95% CI) | −0.9 (−0.8 to −1.1) | −1.7 (−1.3 to −2.2) | ||||

| Mean longstanding illness, % | 54.5 | 53.0 | 52.3 | 41.5 | 53.6 | 53.6 |

| Difference versus not working at scale, % (95% CI) | −1.5 (−1.1 to −2.0) | −2.3 (−1.2 to −3.4) | ||||

Practices in existence in February 2018, except practices with <1000 registered patients.

Working at scale defined as working to serve populations of >30 000 patients, either as single practices or in collaboration with other practices.

Services beyond the core general practice contract, for example, extended access out of hours, and services normally delivered in secondary care.

Large practices, superpartnerships, and multisite organisations, working to deliver core general practice at scale. The core general practice contract requires practices to manage patients who are acutely ill, chronically ill, or terminally ill, during office hours.

IMD 2015 of lower layer super-output area of practice postcode. IMD = Index of Multiple Deprivation. OR = odds ratio.

DISCUSSION

Summary

In February 2018, approximately 55% of the population registered with an English general practice was registered with a practice working at scale; in other words, serving a population of >30 000 people, either individually or collectively. However, only ∼5% of the population was registered with a practice working at scale to deliver core general practice, in one of three organisational models: large practices, superpartnerships, and multisite organisations. Superpartnerships and multisite organisations often did not serve geographically neighbouring populations, although large practices did.

For practices working at scale in looser collaborations, serving just over half of the population, data on composition, purpose, and organisational model were limited, although the practices were mostly neighbours geographically. Where data were available, the purpose of the collaborations was to deliver services over and above core general practice. Many collaborations, of all kinds, were working together to deliver services for very large populations of >50 000 patients. There was variation in practice and patient characteristics according to type of group: practices working at scale were less likely to be rural, had younger populations, and greater levels of socioeconomic deprivation.

Strengths and limitations

This study builds on previous work to identify the extent of working at scale over England. NHS England’s survey about extended hours22 only allowed practices to cite one collaboration; given that the survey focused on extended access, many practices may not have provided complete data on collaborations. Moreover, there may be fewer groups than the dataset suggested because practices within the same group may have given different names for that group.

Some data sources, such as organisational websites, may not be reliable, and may not reflect current practice in a context of rapid change in group members and services. Therefore, the multiple collaborative links may not have been mapped fully. Data on websites relating to large practices, superpartnerships, and multisite organisations, were generally more comprehensive than data from websites relating to federations or other types of group. However, it is recognised that some federations or other types of group may have sophisticated functioning of which the authors were not be able to find documentary evidence.

The data sources did not identify certain other models of working at scale that are known to be operating. These include GP At Hand, which delivers digital remote services (https://www.gpathand.nhs.uk) and is reported to have >30 000 patients registered,27 and a hospital-led model in Wolverhampton is reported to be providing general practice services for 70 000 patients.28 Moreover, it did not reliably identify practices participating in the New Models of Care programme (outlined by the King’s Fund29), which focuses on integration across whole local healthcare systems.

Some of the data sources used in this study were unreliable, which means that the extent of working at scale may have been under- or overestimated, both in terms of working closely together to provide core general practice, and in terms of less-formal arrangements to deliver benefits over and above the requirements of core general practice. One of the key problems in this regard is that practices may be part of more than one collaborative group, as shown in previous studies.11

Comparison with existing literature

It was found that working at scale was common, but not as common as suggested by a recent survey led by the Nuffield Trust of about 600 GPs and 50 staff employed by clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) that suggested that 80% of practices were working in formal or informal collaborations. The Nuffield Trust study had a low response rate (about 25%) but it did provide rich data on the nature of collaborations in responding practices.11

A survey of CCGs by a journalist estimated that ‘70% of the country’ was covered by some sort of ‘scale GP group’.15 However, that survey provided limited data on the nature of collaborations.

Implications for research and practice

Understanding the extent of working at scale in general practice is the first step to evaluating the impact of different models of working at scale, and identifying the optimal size and appropriate models needed to tackle the challenges facing general practice. Evaluation needs to take into account practice and population characteristics. This study highlights many of the challenges of collecting data on working at scale in general practice and can be used to inform better ways of doing so.

It may be that small practices offer better continuity of care, especially for certain patient groups, such as people with multiple long-term conditions. Evidence from the US and Canada suggests that, in comparison with their larger counterparts, small practices may deliver benefits such as better patient experience, more cheaply, with fewer hospital admissions.19,30–32 Whether, however, these benefits are due to smaller organisational size, or other characteristics associated with a smaller registered population, is not known.

For some collaborations — especially some superpartnerships and multisite organisations — the geography of participating practices was not conducive to delivering population-based care, which requires knowledge of the needs of a defined population, with good clinical networks.4 Collaborations serving definable neighbouring geographical populations may be better placed to deliver population-based care. The less-formal collaborations working at scale did tend to cover geographically defined populations; many served very large populations, where achieving agreement between several partners to achieve efficiencies and deliver care according to need may be challenging.

It is generally believed that how general practice is currently organised is not sustainable or fit for purpose. However, the difficulty of sustaining general practice needs to be interpreted in light of pressure from demographic, social, and political forces, including the funding context, workforce, patient characteristics, and changing expectations. The traditional organisational model itself may not be the cause of the problem, nor working at scale the solution. In addition, what ‘working at scale’ actually means in practice is not clear, although the announcement in the new GP contract of a requirement for practices to join PCNs goes some way towards clarifying this.6 What remains very uncertain is how the new PCNs, which will go beyond general practice and attempt to integrate across community services, will be integrated with existing primary care organisations working at scale, especially when these are not defined by shared geography and links with other parts of the health and social care system. Tracking progress towards working at scale and defining what it means in practical terms are critical if the benefits and harms in relation to efficiency, workforce, patient experience, and quality of care, are to be understood.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Institute of Health Research Policy Research Programme through the Policy Research Unit in Commissioning and the Healthcare System (PRUComm). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, the Department of Health and Social Care, or its arm’s length bodies.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required for this study.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.NHS Digital General and Personal Medical Services, England: final 31 December 2017 and provisional 31 March 2018, experimental statistics. 2018. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/general-and-personal-medical-services/final-31-december-2017-and-provisional-31-march-2018-experimental-statistics (accessed 27 Aug 2019)

- 2.Baird B, Reeve H, Ross S, et al. Innovative models of general practice. 2018. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/innovative-models-general-practice (accessed 27 Aug 2019)

- 3.NHS England NHS five year forward view. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/5yfv-web.pdf (accessed 27 Aug 2019)

- 4.NHS England General practice forward view. 2014. https://www.england.nhs.uk/gp/gpfv/ (accessed 27 Aug 2019)

- 5.NHS England Supporting sustainable general practice: a guide to networks and federations for general practice. 2016. https://www.england.nhs.uk/south/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2015/12/guide-netwrks-feds-gp.pdf (accessed 27 Aug 2019)

- 6.NHS England, British Medical Association. Investment and evolution: a five-year framework for gp contract reform to implement. The NHS Long Term Plan.; 2019. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/gp-contract-2019.pdf (accessed 27 Aug 2019) [Google Scholar]

- 7.NHS England The NHS long term plan. 2019. https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/publication/nhs-long-term-plan (accessed 27 Aug 2019)

- 8.Connor R, Primary Care Transformation Programme. Supporting sustainable general practice: a guide to collaboration for general practice. 2016. https://www.england.nhs.uk/south/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2015/12/guide-collaboration-gp.pdf (accessed 27 Aug 2019)

- 9.NHS England Supporting sustainable general practice: a guide to mergers for general practice. 2016. https://www.england.nhs.uk/south/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2015/12/guide-mergers-gp.pdf (accessed 27 Aug 2019)

- 10.Kumpunen S, Rosen R, Kossarova L, Sherlaw-Johnson C. Primary care home: evaluating a new model of primary care. 2017. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/research/primary-care-home-evaluating-a-new-model-of-primary-care (accessed 27 Aug 2019)

- 11.Kumpunen S, Curry N, Farnworth MJ, Rosen R. Collaboration in general practice: surveys of GP practices and clinical commissioning groups. 2017. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/files/2017-10/collaboration-in-general-practice-2017-final.pdf (accessed 27 Aug 2019)

- 12.NHS England The multispecialty community provider (MCP) emerging care model and contract framework. 2016. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/mcp-care-model-frmwrk.pdf (accessed 27 Aug 2019)

- 13.Pettigrew LM, Kumpunen S, Mays N, et al. The impact of new forms of large-scale general practice provider collaborations on England’s NHS: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Rosen R, Kumpunen S, Curry N, et al. Is bigger better? Lessons for large-scale general practice. 2016. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/research/is-bigger-better-lessons-for-large-scale-general-practice (accessed 27 Aug 2019)

- 15.Thomas R. Analysis: England’s Changing GP Landscape. Health Service Journal. 2017. Apr 5, https://www.hsj.co.uk/primary-care/analysis-englands-changing-gp-landscape-/7017089.article (accessed 27 Aug 2019)

- 16.NHS England Next steps on the NHS five year forward view. 2017. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/NEXT-STEPS-ON-THE-NHS-FIVE-YEAR-FORWARD-VIEW.pdf (accessed 27 Aug 2019) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Ng CWL, Ng KP. Does practice size matter? Review of effects on quality of care in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Kelly E, Stoye G. Does GP practice size matter? GP practice size and the quality of primary care. 2014. https://www.ifs.org.uk/uploads/publications/comms/R101.pdf (accessed 27 Aug 2019)

- 19.Casalino LP, Pesko MF, Ryan AM, et al. Small primary care physician practices have low rates of preventable hospital admissions. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33(9):1680–1688. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mostashari F. The paradox of size: how small, independent practices can thrive in value-based care. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14(1):5–7. doi: 10.1370/afm.1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Care Quality Commission. The state of care in general practice 2014 to 2017: Findings from CQC’s programme of comprehensive inspections of GP practices. 2017. https://www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/20170921_state_of_care_in_general_practice2014-17.pdf (accessed 27 Aug 2019)

- 22.NHS England General Practice extended access data — September 2017. 2017. https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical-work-areas/extended-access-general-practice (accessed 27 Aug 2019)

- 23.NHS England NHS England standard general medical services contract 2017/18. 2018. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/17-18-gms-contract.pdf (accessed 27 Aug 2019)

- 24.NHS England NHS England standard Personal Medical Services agreement 2017/18. 2018. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/17-18-pms-contract.pdf (accessed 27 Aug 2019)

- 25.NHS Business Services Authority (NHSBSA). Population demographic data. Newcastle upon Tyne: NHSBSA; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 26.NHS England GP Patient Survey Surveys & Reports. 2017. https://www.gp-patient.co.uk/surveysandreports2017 (accessed 27 Aug 2019)

- 27.Lind S. Scores of GP practices interested in GP at Hand collaboration, claims Babylon. Pulse. 2018. Aug 29, http://www.pulsetoday.co.uk/news/gp-topics/it/scores-of-gp-practices-interested-in-gp-at-hand-collaboration-claims-babylon/20037367.article (accessed 27 Aug 2019)

- 28.Wickware C. Hospital in mass takeover of GP practices will soon have 70k patient list. Pulse. 2017. Jun 21, http://www.pulsetoday.co.uk/news/gp-topics/employment/hospital-in-mass-takeover-of-gp-practices-will-soon-have-70k-patient-list/20034631.article (accessed 27 Aug 2019)

- 29.Collins B. New care models: emerging innovations in governance and organisational form. 2016. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/field_publication_file/New_care_models_Kings_Fund_Oct_2016.pdf (accessed 27 Aug 2019)

- 30.Robinson JC, Miller K. Total expenditures per patient in hospital-owned and physician-owned physician organizations in California. JAMA. 2014;312(16):1663–1669. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.14072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McWilliams JM, Chernew ME, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Delivery system integration and health care spending and quality for Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(15):1447–1456. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Willis TA, West R, Rushforth B, et al. Variations in achievement of evidence-based, high-impact quality indicators in general practice: an observational study. PloS One. 2017;12(7):e0177949. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]