Abstract

Background

Homeless women are twice as likely to become pregnant and are less likely to receive antenatal care than women who are not homeless. Prevalent biopsychosocial complexity and comorbidities, including substance use and mental illness, increase the risk of obstetric complications, postnatal depression, and child loss to social services.

Aim

To explore the perspectives of women who have experienced pregnancy and homelessness to ascertain how to improve perinatal care.

Design and setting

A qualitative study with a purposive sample of women who had experienced pregnancy and homelessness, recruited from three community settings.

Method

Semi-structured interviews continued to data saturation and were recorded, transcribed, and analysed thematically using a self-conscious approach, with independent verification of emergent themes.

Results

Eleven women, diverse in age (18–40 years) and parity (one to five children), participated. Most women had experienced childhood trauma, grief, mental illness, and substance use. Overarching themes of ‘mistrust‘ and ‘fear of child loss to social services’ (CLSS) influenced their interactions with practitioners. The women experienced stigma from practitioners, and lacked effective support networks. Women who mistrusted practitioners attended appointments but concealed their needs, preventing necessary care. Further themes were being seen to do ‘the best for the baby’; pregnancy-enabled access to necessary holistic biopsychosocial care; and lack of postnatal support for CLSS or parenting.

Conclusion

Pregnancy offered a pivotal opportunity for homeless women to engage with care for their complex needs and improve self-care, despite mistrust of practitioners. Poor postnatal support and the distress of CLSS reinforced an ongoing cycle of grief, mental health crises, substance use relapse, and homelessness.

Keywords: childhood trauma, homelessness, perinatal care, pregnancy, substance use, vulnerable patients

INTRODUCTION

Homelessness occurs as a result of complex, interacting, individual, and societal factors.1 Individual factors include childhood poverty, abuse and parental neglect, parental illness, foster care, a lack of supportive networks, adult mental illness, and substance use.1–3 At a societal level, individual factors are compounded by inequality, unemployment, supply and affordability of housing, and the increase in debt and delayed benefit payments caused by the introduction of Universal Credit, associated with UK ‘austerity’ policies, recently outlined by Lord Adebowale.4–6 Overall, the issues homeless people face stem from vulnerability and poverty rather than merely a lack of housing.

In 2018, there were more than 58 000 homeless households in England according to statutory figures. However, Crisis estimates this to be far higher and growing, with a 71% increase in numbers in temporary accommodation over 8 years to 82 310 households in 2018.7,8 True UK homelessness rates, however, are unknown because statutory figures do not include the ‘invisible’ population who are unregistered with local councils or who ‘sofa surf’, a high proportion of whom are female.9 In Sheffield in 2017, a council audit found that 63% of individuals experiencing homelessness also experienced mental illness, 36% used drugs, and around 30% drank more than 10 units of alcohol per day.10 Poor uptake of substance use and mental health services was common.10

A study from 2000 found that 24% of homeless women in London experienced pregnancy within 1 year.11 Homeless women have been found to present late to antenatal care services and to deliver infants of low birthweight, prematurely.12 Infants are also at increased risk of complications relating to substance use, including neonatal alcohol syndrome, bloodborne virus infection, and developmental delay.2,13–15 Furthermore, substance use in pregnancy is associated with postnatal depression, which affects infants’ emotional and psychological development.16,17 Child loss to social services (CLSS) is common, and women with low educational attainment, socioeconomic status, social support, and high unplanned parity are at greater risk.18 It is estimated that between 50 and 80% of children placed in foster care are there as a result of parental substance use.18

Homeless women describe feeling ‘unsettled’ by events experienced in childhood, and move frequently because of an inability to ‘settle’.19 In a UK study in 2001, homeless women described believing that having children might help them to ‘settle’, but later found this to be ‘too hard on the kids’.19 Housing is a major source of stress during and after pregnancy, and women report being placed in social housing only after delivery, and often into unsuitable or unsafe places.20

How this fits in

| Previous literature accurately describes characteristics of individuals experiencing homelessness but fails to capture the impact of childhood trauma as a primary cause of future vulnerability. This study is the first to explore attitudes and experiences of homeless women surrounding perinatal care. This study discovered that, though antenatal service provision was recognised by homeless women to be biomedically thorough, postnatal care was absent, and a lack of trust due to poor communication with healthcare practitioners limited women’s ability to use available services effectively. There is a great need for improved communication and understanding from healthcare practitioners, and for greater postnatal support. This research suggests that postnatal support is as important as antenatal care for vulnerable women, to mitigate further trauma across the lifespan of both mother and child. |

Canadian studies found that healthcare practitioners struggle to communicate with homeless women, and that homeless women mistrust and feel unsupported by healthcare practitioners.1,21,22 There have been no UK studies published regarding homelessness and perinatal care for more than 15 years. Therefore, this study aimed to explore how this vulnerable population conceptualises perinatal care.

METHOD

An information leaflet and consent form were developed with service staff and users, mindful of potential low health literacy. A literature review was used to develop an interview topic guide, which was adjusted iteratively during the interview process.

Semi-structured interviews were undertaken at three facilities for individuals experiencing homelessness in South Yorkshire in January and February 2018 (a shelter, a short-term residence for families, and a day-care facility). Interviews were conducted by one researcher, following thorough training in interview theory and technique. Women were recruited by self-identification as having experienced homelessness and pregnancy. Convenience and ‘snowball’ sampling were used based on women’s availability and the recommendation of facility staff to recruit a purposive maximum variety sample.23

Interviews aimed to establish a portrait of the women and explore their journey through pregnancy, including their attitudes to, and experiences of, care they received. Women were interviewed one-to-one in a private room for approximately 35 minutes; interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Transcribed data were organised using NVivo (version 10). Iterative thematic data analysis was undertaken by one researcher.24 Sampling continued until data saturation of the main themes occurred, and no new insights were apparent. Findings were independently verified and consensus was reached regarding core themes by all members of the research team during regular analysis meetings. A reflexive diary was kept throughout by the main researcher who carried out the interviews to maximise self-awareness throughout the process.

RESULTS

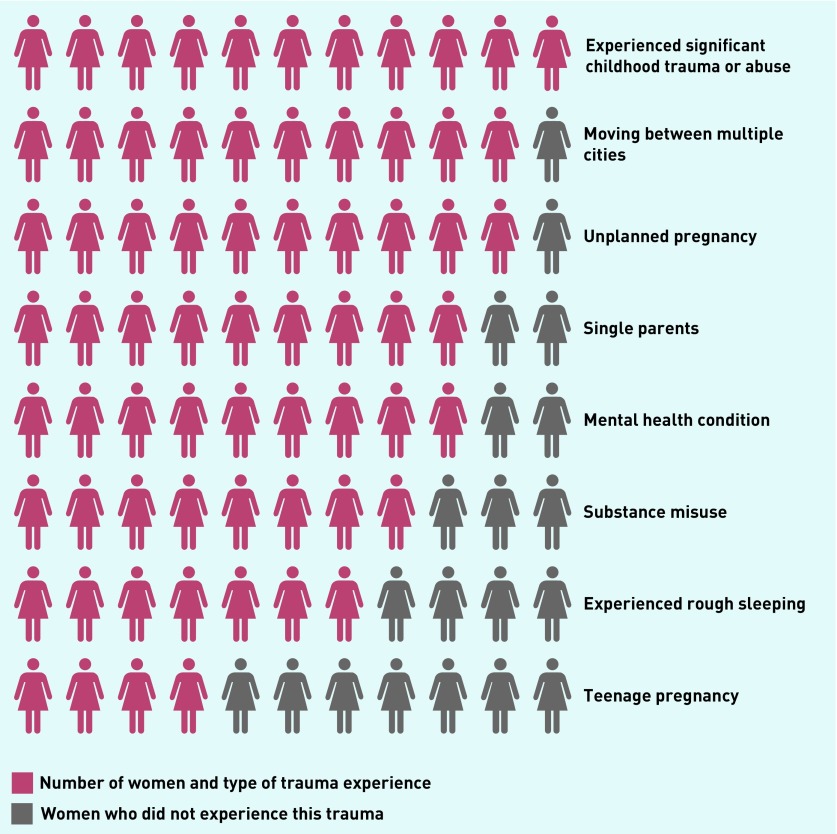

The sample of 11 women was diverse and their past traumas are described in Figure 1. Women were aged 18–40 years, nine were white British, and two were of British/Indian origin. They had lived in 15 cities across the UK. All had experienced trauma or abuse in childhood. Four had left home by the age of 16 years, and four had experienced teenage pregnancy. Most had not completed secondary education. Two had never worked and the remainder had worked in short-term, low-skilled jobs. Three women had experienced domestic abuse. The mean age of first pregnancy was 24 years (4 years below the national average), parity was high in multiparous women (the maximum being five children, none of whom were in the mother’s custody), and eight of the women identified as single. Of the 11 pregnancies, 10 were unplanned.

Figure 1.

Types of trauma experienced by women in the study. Domestic abuse not included for ethical reasons.

The women moved between living on the streets, and living in hostels, private tenancies, and supported accommodation, staying in each for several months. Ten women had moved between multiple cities and seven had slept rough (three during pregnancy). Eight women used drugs, predominantly heroin followed by crack cocaine, while five used multiple drugs. One woman engaged in sex work, and three discussed criminal histories. Figure 1 provides a visual representation of the spread of trauma experienced by these women.

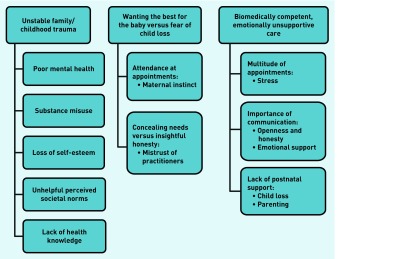

The findings were grouped into three main themes, with subthemes (Figure 2):

unstable family and childhood trauma;

wanting the best for the baby versus fear of child loss; and

biomedically competent, emotionally unsupportive care.

Figure 2.

Themes and subthemes found in the study.

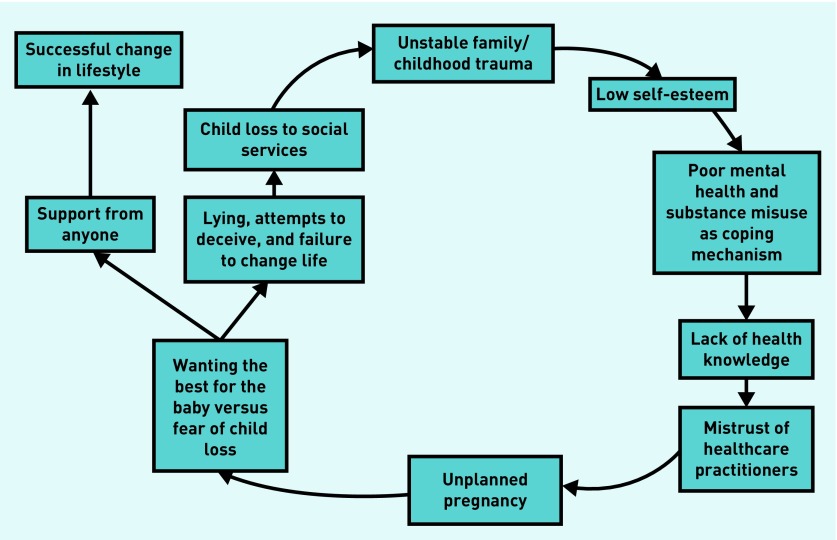

The link between these themes, and overall pathway of homelessness, pregnancy, and child loss, is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Cycles of trauma: pathway of homelessness, pregnancy, and child loss.

Theme 1: Unstable family and childhood trauma

All women described childhood experiences of neglect, grief, or abuse leading to homelessness. This adversity in childhood left women with inadequate health knowledge and unhelpful perceived societal norms surrounding personal safety, health care, and support. The strong sense of community among individuals experiencing homelessness reinforced these ‘norms’:

‘I was hanging out with the wrong people … like drinkers and users … people asking me to score for them and take this and take that.’

(Participant 5, multigravida)

The resultant lack of helpful support left them vulnerable to further abuse:

‘My mum was a drinker … I was drinking a lot … me and my mum, we weren’t always getting on and arguing all the time … so, yeah, left home … to a friend’s house which wasn’t very good, because she got me on prostitution … just before I lost my dad when I was 17.’

(Participant 6, primigravida)

These experiences led to low self-esteem, which was accentuated by homelessness itself. Women described themselves as ‘disgusting’ (Participant 2, multigravida) and anticipated negative stigma, making them hypersensitive. This increased the likelihood of developing, or propagating, mental illness. The combination of mental illness, trauma, and poor support was the driving force behind the development and maintenance of substance use:

‘I was going through a hard time trying to find my real dad and, no excuse, took amphetamine, which gave me psychosis and then I stopped it and then I started taking ecstasy and all sorts of things like that because I was only a teenager as well at the time.’

(Participant 4, multigravida)

Overall, these perceived norms and an expectation of stigma as a result of extensive adversity and low self-esteem produced a mistrust of health and social care practitioners. These included doctors, midwives, health visitors, and social workers, and women felt ‘looked down on because [they were] homeless’ (Participant 2, multigravida) and ‘judged’ (Participant 1, multigravida).

Theme 2: Wanting the best for the baby versus fear of child loss

Loss and trauma in childhood meant that pregnancy was the first time women had felt ‘depended on’ (Participant 3, primigravida). All women expressed deep joy at having ‘somebody that will be mine that I can nurture and do the right thing for’ (Participant 9, multigravida). They felt connected to, and protective of, their unborn children; one participant recounted assuring a social worker ‘over my dead body are you going to take my child, I will fight my dying breath for her’ (Participant 10, primigravida). Women described it as the first time they had had ‘responsibility’, which increased their self-esteem.

This was a motivator to attend appointments, expressed unanimously as wanting to ‘do the best for baby’ (Participant 3, primigravida) and ‘make sure baby is healthy and everything is all right’ (Participant 4, multigravida). All women reported attending what they considered to be all necessary antenatal appointments. Ultrasounds were a highlight:

‘… it was literally like the first time I remember just everything going away, you just see his little body in your tummy.’

(Participant 10, primigravida)

All of the women with substance use issues wanted to ‘get clean’ during pregnancy because of the ‘guilt and blame’ (Participant 2, multigravida) they felt. None considered substance use acceptable, and they were aware that substance use in pregnancy would likely cause CLSS. The maternal joy, and attendance at appointments, therefore came paired with fear that their homelessness or substance use might cause practitioners to report them to social services, risking CLSS:

‘I was really scared, proper scared, because … they’re going to get involved, they’re going to take my baby and everything.’

(Participant 9, multigravida)

In response to fear, women attended what they perceived to be all necessary appointments. This particularly included ultrasound scans and drug-testing appointments in order to ‘look normal’ (Participant 9, multigravida), but four women concealed their needs, particularly around substance use (including manipulating drug tests) because they felt they could not trust practitioners. The women mostly maintained that their care was ‘best’ for the child despite their situation, and would not risk CLSS by admitting the truth:

‘I said if it weren’t such a dim view on social services wanting to whip babies [away], maybe I would have worked openly and honest with them but this was half the problem, I couldn’t do it.’

(Participant 10, primigravida)

This mistrust meant that women did not receive professional support, being too afraid to ask, meaning that ‘getting clean’ was, in most cases, beyond them.

Conversely, women who felt they could trust their GPs, midwives, or substance misuse specialists reported tackling substance use throughout their pregnancy. All those who received help with addiction from healthcare practitioners managed to ‘get clean’ during pregnancy before delivery:

‘They wanted me to get clean … to have the best future for her. If I was using, I think she would have been removed but they actually tried to keep us together and I didn’t think that then but now thinking about it, they actually helped me.’

(Participant 7, multigravida)

Interestingly, establishing good rapport with even one of their practitioners made women more positive towards the others, and more likely to comply effectively with care.

Theme 3: Biomedically competent, emotionally unsupportive care

All women were referred for multiple appointments on presentation to care. These included scans (with additional growth scans for some), GP, key worker, specialist substance misuse worker, and midwife appointments. In addition, they had housing and social care reviews, and, in some cases, probation appointments. Six women experienced complications during pregnancy and required additional monitoring. Although this addressed their medical needs effectively, it added ‘stress’ such that they ‘couldn’t enjoy pregnancy’ (Participant 8, multigravida) and ‘there wasn’t a day in my life I didn’t see a professional’ (Participant 9, multigravida).

The women said that the outcome of healthcare encounters was dependent on the trust they felt towards practitioners. Lack of effective cooperation between mother and practitioners put both mother and baby at risk:

‘As soon as I went to the doctors I felt pissed off because they were referring me to social workers … before they even checked on anything.’

(Participant 2, multigravida)

‘If [practitioners] understood, I wouldn’t lie … because where they say “how much heroin are you using?”, “oh, I use a bag a day” but really I’m using six … and then they think the baby’s going to be fine but, no, the baby was really withdrawing.’

(Participant 9, multigravida)

Conversely, women who trusted services described ‘the whole stress just [coming] off’ (Participant 9, multigravida) and they engaged effectively with available care, including requesting parenting classes. They later attributed keeping their child to the practitioners they worked with.

In order to trust practitioners, women needed to believe that they were not ‘just another statistic who’s going to lose their child’ (Participant 6, primigravida) to practitioners, and wanted practitioners to ‘be kind’ (Participant 9, multigravida), ‘believe in’, and ‘understand’ them. Most crucially, the women reported a profound need to address their fear of CLSS. This was described as:

‘… a two-way street … that I don’t work openly and honestly with them if they don’t work openly and honestly with me.’

(Participant 6, primigravida)

The women needed to know exactly how the information they offered to the practitioner would be used, and what the criteria for keeping their child were to avoid the feeling that it is done ‘sneakily’ (Participant 2, multigravida).

Finally, although care during pregnancy was felt to be biomedically thorough, women described receiving no postnatal support at all. This was particularly problematic for women whose primary coping mechanism had been substance use, because, when they struggled with parenting or CLSS, they instinctively returned to this. This led two women to take themselves to social services out of concern for their children:

‘I went to social services myself because … I was going through a bad place like depression and all that and I weren’t coping. So I’ve never done the drugs around children, do you know what I mean, but it still wasn’t good.’

(Participant 4, multigravida)

Relapse often coincided with mental health collapses and suicide attempts. One woman described the day her children were removed, saying:

‘I only had a friend with me when the kids got took off me, [they] supported me there and then I tried to commit suicide and he stopped me from doing it.’

(Participant 1, multigravida)

Another described coping with CLSS, saying:

‘I just got on with it, just took more amphetamine then moved here and just drank.’

(Participant 2, multigravida)

Others described CLSS as the cause of their heroin addiction, and a further woman described self-medicating with amphetamine to cope with postnatal depression while caring for her baby.

DISCUSSION

Summary

The authors believe this is the first study to explore qualitatively how homeless women conceptualise perinatal care in the UK. The findings illustrate how homeless women’s lifestyles are a reflection of a traumatised past, and therefore the predominant social determinant of their health is not homelessness itself, but rather its causes.25 In order for women to settle successfully, factors including traumatic childhood experiences and resultant substance use must be addressed during their care.

Pregnancy offers a unique window of opportunity for settlement and stability, as women sought care despite their barriers of mistrust and fear of CLSS. The effectiveness of this care is dependent on the practitioner’s ability to establish rapport and gain trust. For 83% of women, the GP is the first practitioner they encounter in pregnancy,26 and has an important role to play in the assessment of physical and psychosocial issues, and early referral to specialist antenatal services where appropriate.27,28 This sets the tone for all future healthcare encounters throughout pregnancy. Effective communication with these women requires GPs to be open and honest about CLSS, and to provide emotional support. Women also require help in defining and establishing a healthy lifestyle, outside of their prior experience. Furthermore, good communication about physical and mental health problems between GPs and maternity care providers is necessary to reduce maternal morbidity and mortality.28

This study has identified a pressing need for greater postnatal support to enable homeless women to parent effectively, or to cope with CLSS. For women with a previous coping mechanism of substance use, the consequences of relapse triggered by the stress of either circumstance are devastating. Furthermore, CLSS does not merely affect mothers, because social or foster care provides temporary and unstable care to children, who may already be potentially traumatised by the loss of their parents, or adversely affected by maternal substance use. Longitudinal observational studies suggest that the ‘looked-after’ children of substance users perform less well academically than their peers, putting them in similarly traumatised and under-educated positions to their mothers, risking propagating a multigenerational cycle of deprivation.29 The current study suggests that postnatal support is as important as antenatal care for vulnerable women, to mitigate further trauma across the lifespan of mother and child.

Strengths and limitations

This study population broadly represents the characteristics of the pregnant homeless population described in the literature (‘transferability’).30 Data saturation was achieved in a maximum variety sample recruited from three community settings, and the women had experienced pregnancy care in 15 cities across the UK. Intensive sampling strategies were used, enlisting support from the staff in the care settings, to interview as many women as possible, in this hard-to-reach population. Women were interviewed in supportive and caring environments, and thus it was possible to conduct in-depth explorations of their experiences in a place of familiarity and relative safety. Although member checking was not possible to triangulate the findings with the women, data analysis was iterative, self-conscious, and subject to independent verification and interpretive challenge in analysis meetings (‘credibility’ and ‘dependability’).24

Comparison with existing literature

The findings of this study are in keeping with previous descriptions of low educational attainment, unemployment, sex work, criminal activity, high rates of substance use, and psychiatric comorbidity in the female homeless population.2,31 The literature also predicted high levels of unplanned parity, young age at first pregnancy, and poorer health in socioeconomically deprived women who move because of negative circumstances, or who experience homelessness during pregnancy.2,32 The findings also echoed previous studies that described unsuitable housing offered to homeless pregnant women and young mothers, and the stress associated with this.20

No previous qualitative studies were identified, and this may explain why the impact of childhood trauma, as the primary cause of vulnerability surrounding pregnancy, is under-recognised. Reported adherence to recommended antenatal appointments is a new finding and contradicts prevalent assumptions about non-engagement with antenatal care services. Women described ‘lying out of fear’, mistrust, stigma, and feeling judged, which contributed to communication failure and missed opportunities to intervene and improve outcomes.

Finally, the current study highlights the psychosocial risk factors and unmet needs of these women, which echo previous studies exploring the circumstances surrounding suicide as the leading cause of maternal mortality in the first year, and current insufficiencies in postnatal support, particularly in mental health.27,33 Shakespeare and Knight27 have highlighted that 50% of women who died postnatally of suicide had previously been diagnosed with recurrent mental illness, and that the structure of current services still places women at risk of inadequate access to perinatal mental health services. The present study demonstrated that CLSS increases the risk of depression postnatally and increases the risk of suicide still further. Further, women who engaged in substance use were found to have multiple factors making them psychosocially vulnerable, and, despite contact with multiple services, none were under the care of perinatal mental health services.27 Better Births also recommends that maternity services be ‘personalised’ to women’s needs and preferences, with increased emphasis on the importance of ‘continuity in care’, based on mutual respect and trust.33 The findings of the current study mirror these recommendations, as they are particularly necessary in vulnerable patients.

Implications for research and practice

There is little UK research published surrounding the health of homeless mothers. Further work is needed to establish true pregnancy rates in the population, and attendance rates at perinatal care.

The GP’s role in pregnancy is widely debated, but most women first discuss their pregnancy with a GP, and GPs are expected to undertake a comprehensive physical and mental health assessment, and refer accordingly to appropriate antenatal care.26 Antenatal communication between vulnerable women and GPs is therefore paramount in establishing rapport and gaining trust early in pregnancy, to facilitate compliance and cooperation with care from other professionals later on. Education for practitioners should teach them to engender trust through open, honest communication and the provision of psychosocial support, remembering that these women often lack any other support. Currently, women are offered a 6-week postnatal maternal examination with a GP to assess their physical and mental health, and this appointment is often linked to the 6–8-week new baby check.33 There may be an additional disincentive for women who experienced CLSS before this point to attend to their own postnatal health needs when they do not have a baby to take to a parallel assessment. Increased awareness by GPs of the risks posed by a lack of other support services is necessary, as well as actions to improve the current support available.

Furthermore, the Pathway model for homeless healthcare provision, which is becoming increasingly established nationally, places primary healthcare professionals at the centre of a homeless individual’s care, drawing on support from secondary care practitioners when required. This could be extended to suggest that GPs could, in future, take more of a lead in coordinating joined-up care to homeless women during and after pregnancy.34

Enhanced postnatal support is needed for women who have experienced homelessness, regardless of whether or not they still have their children. Women who experience insecure housing during pregnancy struggle to cope with either parenting or CLSS, and are likely to instinctively return to old coping mechanisms such as substance use, further reinforcing a cycle of homelessness, relapse of mental illness, and compounding all the personal vulnerabilities that expose these women to unplanned pregnancy. Support must therefore include prolonged mental health care to address previous trauma, support in tackling substance use, as well as holistic care to ensure that practical needs such as housing and financial needs are met. The vulnerability of these women reduces their resilience, such that failure to meet any of these needs seriously risks total collapse in any previous progress achieved in helping them achieve stability during pregnancy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Archer Project, Together Women, Sheffield Area Refuge and Support (SARAS), and Phoenix Futures for their professional support of this project, and Bobbie Walker for her advice and support.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, or from commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval

The project was considered high risk because of the vulnerability of subjects, and required internal and independent scientific review, following which an application was submitted to the University of Sheffield’s School of Health and Related Research Ethics Committee. Approval was granted on 30 January 2018 (reference 016515).

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.Esen UI. The homeless pregnant woman. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017;30(17):2115–2118. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2016.1238896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aldridge RW, Story A, Hwang SW, et al. Morbidity and mortality in homeless individuals, prisoners, sex workers, and individuals with substance use disorders in high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2018;391(10117):241–250. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31869-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mabhala MA, Yohannes A, Griffith M. Social conditions of becoming homelessness: qualitative analysis of life stories of homeless peoples. Int J Equity Health. 2017;16(1):150. doi: 10.1186/s12939-017-0646-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adebowale V. There is no excuse for homelessness in Britain in 2018. BMJ. 2018;360:k902. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Public Health England. Homelessness: applying All Our Health. 2018. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/homelessness-applying-all-our-health/homelessness-applying-all-our-health (accessed 30 Aug 2019)

- 6.Trussell Trust. The next stage of universal credit: moving onto the new benefit system and foodbank use. 2018. https://www.trusselltrust.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2018/10/The-next-stage-of-Universal-Credit-Report-Final.pdf (accessed 30 Aug 2019)

- 7.Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. Statutory homelessness in England: April to June 2018. 2018. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/statutory-homelessness-in-england-april-to-june-2018 (accessed 30 Aug 2019)

- 8.Bax A, Middleton J. Healthcare for people experiencing homelessness. BMJ. 2019;364:l1022. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wood T, Watts K. Challenges of caring for homeless pregnant women — 2. Br J Midwifery. 2005;13(3):142–146. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roberts V, Skinner J. Sheffield homeless health needs audit, 2015. 2016. http://democracy.sheffield.gov.uk/documents/s24516/Homeless%20Health%20Needs%20Audit%20Background%20Paper.pdf (accessed 30 Aug 2019)

- 11.Gorton S. Homeless young women and pregnancy: pregnancy in hostels for single homeless people. 2000. https://www.homelesshub.ca/resource/homeless-young-women-and-pregnancy-pregnancy-hostels-single-homeless-people (accessed 30 Aug 2019)

- 12.Paterson CM, Roderick P. Obstetric outcome in homeless women. BMJ. 1990;301(6746):263–266. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6746.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kapaya H, Mercer E, Boffey F, et al. Deprivation and poor psychosocial support are key determinants of late antenatal presentation and poor fetal outcomes: a combined retrospective and prospective study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:309. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0753-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fajemirokun-Odudeyi O, Sinha C, Tutty S, et al. Pregnancy outcome in women who use opiates. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2006;126(2):170–175. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dryden C, Young D, Hepburn M, Mactier H. Maternal methadone use in pregnancy: factors associated with the development of neonatal abstinence syndrome and implications for healthcare resources. BJOG. 2009;116(5):665–671. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.02073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cutts DB, Coleman S, Black MM, et al. Homelessness during pregnancy: a unique, time-dependent risk factor of birth outcomes. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19(6):1276–1283. doi: 10.1007/s10995-014-1633-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D’Souza L, Garcia J. Improving services for disadvantaged childbearing women. Child Care Health Dev. 2004;30(6):599–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2004.00471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Canfield M, Radcliffe P, Marlow S, et al. Maternal substance use and child protection: a rapid evidence assessment of factors associated with loss of child care. Child Abuse Negl. 2017;70:11–27. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walters S, East L. The cycle of homelessness in the lives of young mothers: the diagnostic phase of an action research project. J Clin Nurs. 2001;10(2):171–179. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2001.00458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith D, Roberts R. Young parents: the role of housing in understanding social inequality. J Fam Health Care. 2011;21(1):20–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woith WM, Kerber C, Astroth KS, Jenkins SH. Lessons from the homeless: civil and uncivil interactions with nurses, self-care behaviors, and barriers to care. Nurs Forum. 2017;52(3):211–220. doi: 10.1111/nuf.12191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richter S, Caine V, Kubota H, et al. Delivering care to women who are homeless: a narrative inquiry into the experience of health care providers in an obstetrical unit. Divers Equal Health Care. 2017;14(3):122–129. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bryman A. Social research methods. 5th edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boyatzis RE. Transforming qualitative information: thematic analysis and code development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marmot M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet. 2005;365(9464):1099–1104. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith A, Shakespeare J, Dixon A. The role of GPs in maternity care — what does the future hold?. London: King’s Fund; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shakespeare J, Knight M. The Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths 2015: lessons for GPs. Br J Gen Pract. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Knight M, Bunch K, Tuffnell D, et al., editors. Saving lives, improving mothers’ care: lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2014–16. 2018. https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/downloads/files/mbrrace-uk/reports/MBRRACE-UK%20Maternal%20Report%202018%20-%20Web%20Version.pdf (accessed 30 Aug 2019)

- 29.Morse A. Children in care. 2014. https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Children-in-care1.pdf (accessed 30 Aug 2019)

- 30.Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Richards R, Merrill RM, Baksh L. Health behaviors and infant health outcomes in homeless pregnant women in the United States. Pediatrics. 2011;128(3):438–446. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tunstall H, Pickett K, Johnsen S. Residential mobility in the UK during pregnancy and infancy: are pregnant women, new mothers and infants ‘unhealthy migrants’? Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(4):786–798. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.National Maternity Review. Better births: improving outcomes of maternity services in England A Five Year Forward View for maternity care. 2016. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/national-maternity-review-report.pdf (accessed 30 Aug 2019)

- 34.Faculty of Homeless and Inclusion Health, Pathway. Homeless and inclusion health standards for commissioners and service providers. 2018. https://www.pathway.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Version-3.1-Standards-2018-Final.pdf (accessed 30 Aug 2019)