To the Editor:

Clinical Implications.

-

•

Acid-suppressant medications are commonly used during pregnancy. In a cohort of US children at high risk for asthma due to severe bronchiolitis in infancy, we found that prenatal exposure to acid-suppressant medications increased the risk of developing recurrent wheeze. Future research is needed on this topic. During the interim, clinicians may wish to discuss with patients the potential risks and benefits of acid-suppressant medication use in pregnancy.

Asthma, one of the most common chronic diseases of childhood, develops through complex interactions between genetic susceptibilities and environmental exposures.1, 2 In the United States, acid-suppressant medications (ASMs) are available widely, either by prescription or over-the-counter purchase, and are commonly used throughout the lifespan, including during pregnancy.3, 4 Recent evidence from outside the United States suggests that prenatal exposure to ASMs may be associated with an increased risk of asthma in children.5, 6 These previous studies were performed in mostly European populations and were conducted retrospectively in large databases and thus relied primarily on prescription records and diagnosis codes to identify exposures and outcomes.7 Despite efforts to control for bias and confounding, these retrospective observational studies were potentially affected by misclassification of both the exposure and outcome and inability to adjust for various factors, including maternal atopy.7

Our objective was to evaluate whether prenatal exposure to ASMs increases the risk of recurrent wheeze in a population of racially/ethnically diverse US children who already are at high risk of developing asthma due to severe bronchiolitis in infancy. We investigated the 35th Multicenter Airway Research Collaboration (MARC-35) cohort composed of children with a history of severe bronchiolitis in infancy. This population is novel due to their racial/ethnic diversity as well as their increased risk of developing asthma due to their bronchiolitis event.8

Among the 921 participants in the MARC-35 longitudinal cohort, 900 (98%) had complete exposure and outcome data. Exposure was defined by parental report of maternal use of ASMs during pregnancy with either histamine-2 receptor antagonists or proton pump inhibitors. The outcome of recurrent wheeze by age 3 years was defined per the 2007 National Institutes of Health asthma guidelines: (1) having at least 2 corticosteroid-requiring exacerbations within 6 months, or (2) having at least 4 wheezing episodes within 1 year, each lasting at least 1 day and affecting sleep.9 Unadjusted and adjusted analyses were performed using Cox-proportional hazards modeling stratified by age, with multivariable models adjusted for 9 potential confounders using STATA SE 15.1 (College Station, Texas) (for detailed methods and results, see this article's Online Repository www.jaci-inpractice.org).

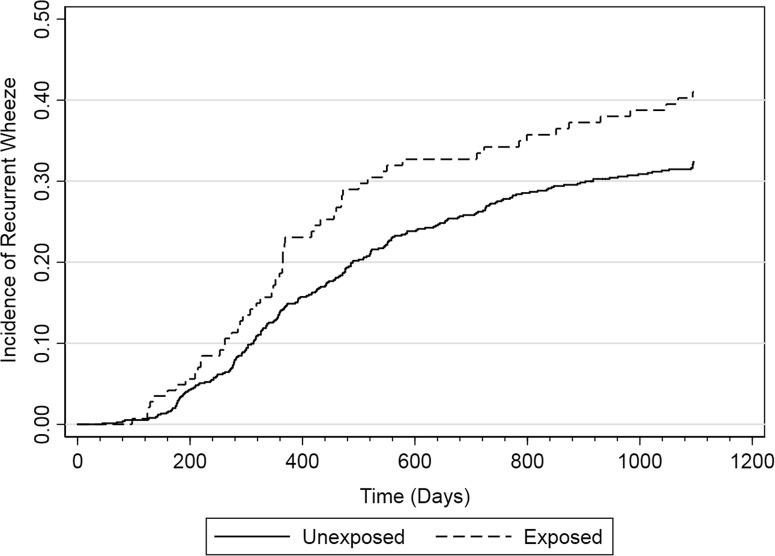

In this cohort of geographically and racial/ethnically diverse children in the United States, 16% (144 of 900) of mothers reported using ASMs during pregnancy (Table I ). Of these mothers, 17% (24 of 144) reported use for 1 month or less, 31% (44 of 144) for 2 to 3 months, 20% (29 of 144) for 4 to 5 months, 32% (46 of 144) for 6 months or more, and less than 1% (1 of 144) had an unknown duration of use. At enrollment, the median total serum IgE level did not differ significantly between the exposed children at 4.64 kU/L (interquartile range, 1.9-15.5) as compared with the unexposed children at 4.20 kU/L (interquartile range, 1.9-12.15) (P = .70). Recurrent wheeze developed in 32% (289 of 900) of children by age 3 years. In unexposed children, 31% (233 of 756) developed recurrent wheeze as compared with 39% (56 of 144) of exposed children (unadjusted hazard ratio [HR], 1.38; 95% CI, 1.03-1.85). The increased risk persisted despite adjustment for potential confounders (adjusted HR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.02-1.91) (Table II ; see Figure E1 in this article's Online Repository at www.jaci-inpractice.org). Although statistical power was low, we performed exploratory analyses to investigate the relationship between duration of exposure to ASMs during pregnancy and the risk of recurrent wheeze. Those exposed for less than 2 months during pregnancy had a lower risk of developing recurrent wheeze (adjusted HR, 1.27; 95% CI, 0.64-2.54) than those exposed for more than 2 months during pregnancy (adjusted HR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.02-1.98).

Table I.

Baseline characteristics of infants hospitalized for bronchiolitis by prenatal ASM exposure

| Demographic characteristics | Analytical cohort (n = 900) | ASM Exposed (n = 144) | ASM Unexposed (n = 756) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at enrollment (mo), median (IQR) | 3.22 (1.67-6.00) | 3.42 (1.81-6.05) | 3.20 (1.64-5.93) | .48 |

| Sex | .61 | |||

| Female | 361 (40) | 55 (38) | 306 (40) | |

| Male | 539 (60) | 89 (62) | 450 (60) | |

| Race/ethnicity | <.001 | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 396 (44) | 93 (65) | 303 (40) | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 201 (22) | 22 (15) | 179 (24) | |

| Hispanic | 268 (30) | 27 (19) | 241 (32) | |

| Other | 35 (4) | 2 (1) | 33 (4) | |

| Insurance status | <.001 | |||

| Private | 367 (41) | 88 (61) | 279 (37) | |

| Public | 519 (58) | 54 (38) | 465 (62) | |

| Uninsured | 12 (1) | 2 (1) | 10 (1) | |

| Median household income | .03 | |||

| <$40,000 per year | 304 (34) | 37 (26) | 267 (35) | |

| ≥$ 40,000 per year | 596 (66) | 107 (74) | 489 (65) | |

| Gestational age at birth (wk) | <.001 | |||

| >40 | 352 (39) | 38 (26) | 314 (42) | |

| >37-40 | 382 (42) | 59 (41) | 323 (43) | |

| >34-37 | 134 (15) | 39 (27) | 95 (13) | |

| >32-34 | 32 (4) | 8 (6) | 24 (3) | |

| Birth weight (lb) | .15 | |||

| <5 | 57 (6) | 13 (9) | 44 (6) | |

| ≥5 | 838 (94) | 131 (91) | 707 (94) | |

| Mode of delivery | .07 | |||

| Vaginal | 589 (66) | 85 (59) | 504 (67) | |

| C-Section | 310 (34) | 59 (41) | 251 (33) | |

| Multiple birth (ie, twin) | <.001 | |||

| Yes | 41 (5) | 16 (11) | 25 (3) | |

| No | 859 (95) | 128 (89) | 731 (97) | |

| Maternal antibiotics before labor | .004 | |||

| Yes | 242 (27) | 52 (37) | 190 (25) | |

| No | 647 (73) | 88 (63) | 559 (75) | |

| Maternal smoking during pregnancy | .16 | |||

| Yes | 123 (14) | 25 (17) | 98 (13) | |

| No | 776 (86) | 119 (83) | 657 (87) | |

| Maternal history of asthma | .002 | |||

| Yes | 192 (21) | 45 (31) | 147 (20) | |

| No | 702 (79) | 98 (69) | 604 (80) | |

| Maternal history of atopic condition∗ | <.001 | |||

| Yes | 208 (23) | 50 (35) | 158 (21) | |

| No | 689 (77) | 93 (65) | 596 (79) |

C-section, Cesarean section; IQR, interquartile range.

Data are expressed as n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Atopic conditions include asthma, allergic rhinitis, food allergy, and eczema.

Table II.

Prenatal exposure to ASMs and risk of recurrent wheeze by age 3 y

| Exposed (n = 144, cases = 56) | Unexposed (n = 756, cases = 233) | |

|---|---|---|

| Cox-proportional hazards∗ | ||

| Unadjusted | 1.38 (1.03-1.85)† | 1.00 (reference) |

| Adjusted model A | 1.40 (1.03-1.89)† | 1.00 (reference) |

| Adjusted model B | 1.40 (1.02-1.91)† | 1.00 (reference) |

Model A: Adjusted for sex, insurance, race/ethnicity, and median household income.

Model B: Adjusted for sex, insurance, race/ethnicity, median household income, maternal history of atopic disease (asthma, allergic rhinitis, food allergy, and eczema), maternal smoking during pregnancy, gestational age at birth, multiple gestation (eg, twin), mode of delivery, and maternal use of antibiotics during pregnancy before labor.

All models were stratified by age at enrollment.

Statistically significant with P < .05.

Figure E1.

Incidence of recurrent wheeze from birth to age 3 years by prenatal exposure to ASMs.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate prenatal exposure to ASMs and recurrent wheeze in a prospective US based-cohort, and the first to investigate this issue among infants at high risk of developing asthma. The study design and analysis enabled us to limit several potential sources of bias. Direct ascertainment of maternal ASM use from the parent decreases misclassification of the exposure. In the United States, maternal report of ASM use is likely superior to medical record documentation due to availability of these medications by over-the-counter purchase. We report that 16% of mothers used ASMs during pregnancy; however, the baseline population rates of ASM use in pregnancy in the United States have not been accurately identified because of easy over-the-counter purchase. Recurrent wheeze was determined by detailed parental interviews every 6 months and is consistent with current National Institutes of Health guidelines.9 Thus, we expect less outcome misclassification. Our cohort is racially/ethnically diverse (>50% nonwhite), which may be more generalizable to the US population than previous studies performed primarily in European populations. Finally, we gathered detailed information directly from the children's parents regarding many potential confounders including parental history of allergic disease and sociodemographic and perinatal factors. Despite these adjustments, prenatal ASM exposure had a consistent association with the development of recurrent wheeze in all main analyses.

The underlying mechanism by which ASMs may increase the risk of recurrent wheeze and subsequent asthma is not known. There is evidence to suggest that ASMs, including proton pump inhibitors and histamine-2 receptor antagonists, may predispose to allergic sensitization, the propensity to express TH2 cytokines, and dysbiosis of the microbiome.7, 10, 11 These effects are thought to be related to their common function of suppressing gastric acid. In our study, we found no significant difference in the total IgE between exposed and unexposed infants. However, these samples were collected at enrollment (median age, 3.2 months), which may either be too distant from the exposure or too early in infancy to detect meaningful differences. Likewise, the role of the microbiome is increasingly recognized in the development of asthma7; however, more research is needed to determine whether ASM use is associated with alterations in the microbiome that predispose individuals to developing asthma.

Limitations of our study include the observational design, which precludes strong statements about causality. Despite efforts to adjust for confounding, it is possible that unmeasured confounding remains, including confounding by indication. Prenatal exposure to ASMs was obtained at the time of study enrollment, which raises the possibility of recall bias. However, all children were young infants (median age, 3.2 months) at the time of enrollment and all were currently hospitalized for an acute illness; thus, we would not expect maternal recall bias. On the basis of the nature of the data, we are limited in our ability to determine the trimester of exposure in which the effect of ASMs may be the greatest. Most mothers (52%) reported the use of ASMs for at least 4 months, inherently accounting for exposure in more than 1 trimester. All the children in the cohort are at high risk for developing recurrent wheeze due to their shared history of severe bronchiolitis in infancy, which limits the generalizability of the study. However, bronchiolitis is not a rare infection in childhood and is the most common cause of hospitalization in US infants (130,000 hospitalizations/y); thus, although our study is not generalizable to all children, it is generalizable to a large patient population.8

In conclusion, prenatal ASM exposure appears to further increase the risk of recurrent wheeze in children with a history of severe bronchiolitis in infancy. This finding is important because prenatal exposure to ASMs is modifiable. Although further research is needed in low-risk populations, clinicians may wish to discuss the potential risks and benefits of elective ASM therapy before initiation in pregnancy. We will continue to follow these children for the development of asthma and plan to investigate the association of ASM exposure with this important outcome. We encourage future research on the risk of ASM exposure in a low-risk general population, the risk of bronchiolitis after prenatal exposure to ASMs, the potential for a dose-dependent or trimester-dependent effect of ASM exposure, potential confounding (including confounding by indication), and elucidating the potential underlying mechanism.

Footnotes

The cohort is supported by National Institutes of Health awards U01 AI-087881, R01 AI-114552, and UG3 OD-023253 awarded to C.A.C. L.B.R. is supported by the National Institutes of Health award T32HL116275. A.J.C.A. is supported by the National Institutes of Health award 5T32AI00730631. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflicts of interest: The authors report that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

Online Repository. Methods

Study design and study population

The 35th Multicenter Airway Research Collaboration (MARC-35) is a multicenter prospective cohort study of infants younger than 1 year enrolled during an episode of severe bronchiolitis from 2011 to 2014. Severe bronchiolitis was defined by the need for hospitalization. The study was conducted at 17 sites in the United States using a standardized protocol, details of which have been previously published.E1 Children who met the end point of recurrent wheeze before study entry were excluded.

We enrolled 1016 children in the study, of which 921 children were followed in the longitudinal cohort. The analytic cohort for the present analysis was defined as the 900 (98%) participants in the longitudinal cohort with complete exposure and outcome data. At the time of enrollment, a parent participated in a detailed in-person interview to capture demographic, parental health, perinatal, and child health information. The subject's parent subsequently underwent structured telephone interview by trained study staff every 6 months. Blood samples were obtained from all participants at enrollment. Serum was analyzed for multiple parameters including total IgE level. Allergen testing was performed by Phadia Immunology Reference Laboratory (Portage, Mich). This analysis was a predetermined secondary analysis.

The study was approved by the institutional review board at each participating site and conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice Standards. Written informed consent was obtained from the parent or guardian of each study subject.

Exposure

Information on the maternal use of ASMs (proton pump inhibitors or histamine-2 receptor antagonists) during pregnancy was obtained from the parent by questionnaire at enrollment. The following questions were used to determine exposure status:

-

•

“When pregnant with your child, did you/the biological mother take H2 blockers or proton pump inhibitors for gastroesophageal reflux (heartburn, GERD) or ulcers? Examples were provided. Respondents were instructed not to include antacids.

-

•

If the response was yes, they were asked “How many months of the pregnancy did you/she take these medications?”

Outcome

Recurrent wheeze by age 3 years was defined per the 2007 National Institutes of Health asthma guidelines: (1) having at least 2 corticosteroid-requiring exacerbations within 6 months, or (2) having at least 4 wheezing episodes within 1 year, each lasting at least 1 day and affecting sleep.E2 This outcome was continually assessed by structured telephone interviews with the parents every 6 months for the first 36 months of life. For all breathing problems, detailed information was gathered including date of onset of symptoms, duration of symptoms, effect on sleep, medical care received, and medications used.

Covariates

At enrollment, the parent provided detailed information regarding multiple covariates including demographic characteristics of race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white [NHW], non-Hispanic black [NHB], Hispanic, and other), insurance status, maternal and paternal history of allergic conditions (asthma, allergic rhinitis, food allergy, and eczema), maternal smoking during pregnancy, gestational age at birth, child's birth weight, multiple gestation (eg, twin), mode of delivery, maternal use of antibiotics during pregnancy, and child's health before study enrollment. Household income at enrollment was estimated on the basis of median household income by ZIP code obtained from Esri ArcGIS Business Analyst Desktop (Redlands, Calif).

Statistical analysis

Summary data on demographic characteristics and maternal factors were compared using Pearson chi-square test for categorical variables and Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables as appropriate. Unadjusted and adjusted HRs were calculated using Cox-proportional hazards modeling stratified by the age of the child at enrollment. The assumption of proportional hazards was verified using Schoenfeld residuals. The hazards for age at enrollment were not proportional over time; thus, all multivariable models were specified to stratify by age. Two adjusted models were used to assess for the effect of potential confounders. The first model adjusted for sociodemographic factors including sex, race/ethnicity, and median household income. The fully adjusted model adjusted for sex, race/ethnicity, median household income, maternal history of atopy (asthma, allergic rhinitis, food allergy, or eczema), maternal smoking during pregnancy, gestational age at birth, multiple gestation (eg, twin), mode of delivery, and maternal use of antibiotics during pregnancy before labor. All covariates included in the model were determined a priori on the basis of current understanding of the biologic model. We performed stratified analysis by race/ethnicity (NHW, NHB, and Hispanic) including full adjustment for the potential confounders listed above. In addition, we performed analysis on the basis of duration of exposure to ASMs during pregnancy (No ASM use, <2 months of use, and ≥2 months of use) including full adjustment for potential confounders. Statistical significance was determined by a 2-sided P value of less than .05.

Results

The exposed cohort was primarily composed of 65% (93 of 144) NHW children who were insured privately and had a median household income of greater than or equal to $40,000/y (Table E1). There were no significant differences between the ASM-exposed and ASM-unexposed groups in the types of viral pathogens isolated during the initial bronchiolitis event. There was no significant difference in the severity of initial bronchiolitis event (intensive care unit admission and intubation) (Table E2).

Although statistical power was low, we performed an exploratory analysis in different racial/ethnic groups and found an adjusted HR above 1.00 for all 3 major groups: NHW 1.07 (95% CI, 0.69-1.66), NHB 1.34 (95% CI, 0.65-2.79), and Hispanics 2.16 (95% CI, 1.07-4.39); the excess risk among Hispanics with prenatal exposure to ASM was statistically significant (P interaction = .045).

Table E1.

Baseline characteristics of infants hospitalized for bronchiolitis by prenatal ASM exposure and development of recurrent wheeze

| Demographic characteristics | Analytical cohort (n = 900) | ASM exposed with recurrent wheeze (n = 56) | ASM exposed without recurrent wheeze (n = 88) | ASM unexposed with recurrent wheeze (n = 233) | ASM unexposed without recurrent wheeze (n = 523) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at enrollment (mo), median (IQR) | 3.22 (1.67-6.00) | 4.47 (2.62-7.52) | 2.94 (1.38-5.63) | 3.58 (2.07-6.08) | 2.96 (1.51 -5.91) | .47 |

| Sex | .92 | |||||

| Female | 361 (40) | 20 (36) | 35 (40) | 95 (41) | 211 (40) | |

| Male | 539 (60) | 36 (64) | 53 (60) | 138 (59) | 312 (60) | |

| Race/ethnicity | <.001 | |||||

| NHW | 396 (44) | 32 (57) | 61 (69) | 104 (45) | 199 (38) | |

| NHB | 201 (22) | 10 (18) | 12 (14) | 62 (27) | 117 (22) | |

| Hispanic | 268 (30) | 13 (23) | 14 (16) | 60 (26) | 181 (35) | |

| Other | 35 (4) | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | 7 (3) | 26 (5) | |

| Insurance status | <.001 | |||||

| Private | 367 (41) | 29 (52) | 59 (67) | 84 (36) | 195 (38) | |

| Public | 519 (58) | 25 (45) | 29 (33) | 146 (63) | 319 (61) | |

| Uninsured | 12 (1) | 2 (4) | 0 | 2 (1) | 8 (2) | |

| Median household income | .17 | |||||

| <$40,000 per year | 304 (34) | 14 (25) | 23 (26) | 81 (35) | 186 (36) | |

| ≥$ 40,000 per year | 596 (66) | 42 (75) | 65 (74) | 152 (65) | 337 (64) | |

| Gestational age at birth (wk) | <.001 | |||||

| >40 | 352 (39) | 20 (36) | 18 (20) | 93 (40) | 221 (42) | |

| >37-40 | 382 (42) | 20 (36) | 39 (44) | 101 (43) | 222 (43) | |

| >34-37 | 134 (15) | 10 (18) | 29 (33) | 28 (12) | 67 (13) | |

| >32-34 | 32 (4) | 6 (11) | 2 (2) | 11 (5) | 13 (2) | |

| Birth weight (lb) | .041 | |||||

| <5 | 57 (6) | 7 (13) | 6 (7) | 20 (9) | 24 (5) | |

| ≥5 | 838 (94) | 49 (88) | 82 (93) | 211 (91) | 496 (95) | |

| Mode of delivery | .07 | |||||

| Vaginal | 589 (66) | 28 (50) | 57 (65) | 160 (69) | 344 (66) | |

| C-Section | 310 (34) | 28 (50) | 31 (35) | 73 (31) | 178 (34) | |

| Multiple birth (ie, twin) | <.001 | |||||

| Yes | 41 (5) | 6 (11) | 10 (11) | 6 (3) | 19 (4) | |

| No | 859 (95) | 50 (89) | 78 (89) | 227 (97) | 504 (96) | |

| Maternal antibiotics before labor | .010 | |||||

| Yes | 242 (27) | 22 (40) | 30 (35) | 67 (29) | 123 (24) | |

| No | 647 (73) | 33 (60) | 55 (65) | 161 (71) | 398 (76) | |

| Maternal smoking during pregnancy | .065 | |||||

| Yes | 123 (14) | 14 (25) | 11 (13) | 34 (15) | 64 (12) | |

| No | 776 (86) | 42 (75) | 77 (88) | 199 (85) | 458 (88) | |

| Maternal history of asthma | <.001 | |||||

| Yes | 192 (21) | 24 (43) | 21 (24) | 60 (26) | 87 (17) | |

| No | 702 (79) | 32 (57) | 66 (76) | 171 (74) | 433 (83) | |

| Maternal history of atopic condition∗ | <.001 | |||||

| Yes | 208 (23) | 22 (39) | 28 (32) | 61 (26) | 97 (19) | |

| No | 689 (77) | 34 (61) | 59 (68) | 172 (74) | 424 (81) |

C-Section, Cesarean section; IQR, interquartile range.

Data are expressed as n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Atopic conditions include asthma, allergic rhinitis, food allergy, and eczema.

Table E2.

Viral pathogens and severity of initial bronchiolitis event by prenatal ASM exposure

| Characteristics of initial bronchiolitis event | ASM Exposed (n = 144) | ASM Unexposed (n = 756) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viral pathogen∗ | |||

| HRV | 31 (22) | 152 (20) | .70 |

| RSV A | 86 (60) | 445 (59) | .85 |

| RSV B | 29 (20) | 180 (24) | .34 |

| Human metapneumovirus | 7 (5) | 40 (5) | .83 |

| Coronavirus | 5 (6) | 48 (6) | .72 |

| Adenovirus | 5 (3) | 37 (5) | .46 |

| Mycoplasma | 2 (1) | 9 (1) | .84 |

| Influenza A | 2 (1) | 6 (1) | .49 |

| Influenza B | 2 (1) | 3 (0.4) | .14 |

| Parainfluenza 1 | 0 | 4 (1) | .38 |

| Parainfluenza 2 | 0 | 2 (0.2) | .54 |

| Parainfluenza 3 | 3 (2) | 16 (2) | .98 |

| ICU Admission | .98 | ||

| Yes | 21 (15) | 111 (15) | |

| No | 123 (85) | 645 (85) | |

| Intubation | .33 | ||

| Yes | 3 (2) | 28 (4) | |

| No | 141 (98) | 728 (96) |

HRV, Human rhinovirus; ICU, intensive care unit; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

Children could have no virus detected, 1 virus detected, or multiple viruses detected.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National current asthma prevalence. 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/most_recent_data.htm Available from:

- 2.Bonnelykke K., Ober C. Leveraging gene-environment interactions and endotypes for asthma gene discovery. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:667–679. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richter J.E. Review article: the management of heartburn in pregnancy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:749–757. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gawron A.J., Feinglass J., Pandolfino J.E., Tan B.K., Bove M.J., Shintani-Smith S. Brand name and generic proton pump inhibitor prescriptions in the United States: insights from the national ambulatory medical care survey (2006-2010) Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2015;2015:689531. doi: 10.1155/2015/689531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Devine R.E., McCleary N., Sheikh A., Nwaru B.I. Acid-suppressive medications during pregnancy and risk of asthma and allergy in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:1985–1988. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lai T., Wu M., Liu J., Luo M., He L., Wang X., et al. Acid-suppressive drug use during pregnancy and the risk of childhood asthma: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2018;141:e20170889. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robinson L.B., Camargo C.A., Jr. Acid suppressant medications and the risk of allergic diseases. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2018;14:771–780. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2018.1512405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hasegawa K., Mansbach J.M., Camargo C.A., Jr. Infectious pathogens and bronchiolitis outcomes. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2014;12:817–828. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2014.906901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma-summary report 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:S94–S138. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Untersmayr E., Bakos N., Scholl I., Kundi M., Roth-Walter F., Szalai K., et al. Anti-ulcer drugs promote IgE formation toward dietary antigens in adult patients. FASEB J. 2005;19:656. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3170fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scholl I., Ackermann U., Ozdemir C., Blumer N., Dicke T., Sel S., et al. Anti-ulcer treatment during pregnancy induces food allergy in mouse mothers and a Th2-bias in their offspring. FASEB J. 2007;21:1264–1270. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7223com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

- Hasegawa K., Stewart C.J., Celedon J.C., Mansbach J.M., Tierney C., Camargo C.A., Jr. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D, metabolome, and bronchiolitis severity among infants: a multicenter cohort study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2018;29:441–445. doi: 10.1111/pai.12880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma—summary report 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:S94–S138. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]