Abstract

Introduction

Lipocalin-2 is an acute-phase protein with pleotropic functions that has been implicated in several diseases including Alzheimer's disease (AD). However, it is unknown if circulating lipocalin-2 levels are altered in the preclinical stage of AD, where AD pathology has accumulated but cognition remains relatively intact.

Methods

In this cross-sectional study, we used an immunoassay to measure plasma lipocalin-2 levels in cognitively normal (Clinical Dementia Rating 0) elderly individuals. 38 of 156 subjects were classified as preclinical AD by cerebrospinal fluid criteria.

Results

Plasma lipocalin-2 levels were higher in preclinical AD compared with control subjects and associated with cerebrospinal fluid amyloid-beta42 levels but not cerebrospinal fluid tau or phosphorylated-tau181 levels. Exploratory analyses revealed that plasma lipocalin-2 was associated with executive function but not episodic memory.

Discussion

Collectively, these results raise the possibility that circulating lipocalin-2 is involved early in AD pathogenesis and may represent an early blood biomarker of amyloid-beta pathology.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, Amyloid beta-Peptides, Biomarkers, Blood, Dementia, Immunoassay, Lipocalin, NGAL, Preclinical

1. Introduction

Although Alzheimer's disease (AD) remains incurable, progress has been made toward elucidating key elements of AD pathogenesis including the identification of a preclinical stage, where neuropathological abnormalities such as amyloid-beta (Aβ) peptides and tau aggregates accumulate for decades before any significant cognitive symptoms [1]. Importantly, through neuroimaging with positron emission tomography or measurement of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels of Aβ and tau, it is now possible to identify individuals in vivo with AD pathology during the preclinical stage of AD [2], [3]. Furthermore, recent failures in intervention trials suggest that targeting AD once cognitive impairment manifests and significant neuronal death occurs may be too late [4]. Therefore, understanding the full pathobiology of AD during the preclinical stage is critical for early diagnosis and intervention. As accumulating evidence suggests that changes in systemic metabolism and inflammation occurs early in AD [5], [6], circulating signaling molecules modulating both systemic metabolism and inflammation that can cross the blood-brain barrier may be critical components of AD pathogenesis. However, the identity of these signaling molecules in biomarker-defined preclinical AD, and any association with Aβ and tau pathology, remain unclear.

Lipocalin-2, also known as neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin, 24p3, or siderocalin, is a secreted glycoprotein and a member of the diverse lipocalin family of carriers of lipophilic/hydrophobic molecules [7], [8]. Lipocalin-2 is expressed and found in a wide range of peripheral cell types including epithelial cells from various organs, osteoblasts, adipocytes, and immune cells with reported roles in innate immunity, iron homeostasis, and regulation of body weight and insulin signaling [7], [8]. In the central nervous system, lipocalin-2, produced locally or transported from the periphery through the blood-brain barrier, has been implicated in neuroinflammation, iron homeostasis, appetite, cognition, and memory, and as such, is well positioned to be a potential contributor to AD pathobiology.

Because lipocalin-2 is an acute-phase protein with pleotropic functions, circulating lipocalin-2 has been proposed as a biomarker for several diseases such as acute kidney injury, heart failure, obesity, and various brain disorders including AD [7]. However, all studies to date investigating circulating lipocalin-2 in AD have been conflicting and inconclusive [9], [10], possibly reflecting the fact that these studies have used subjects who were classified solely by clinical criteria without any supporting evidence from Aβ or tau biomarkers. Therefore, our study sought to determine whether plasma levels of lipocalin-2 are altered in cognitively normal subjects with CSF biomarker-defined preclinical AD compared with CSF biomarker–negative controls and whether plasma levels of lipocalin-2 are associated with Aβ or tau pathology and cognitive function.

2. Methods

2.1. Study participants

Participants were community-dwelling volunteers (age in years: mean 68.7, range 51.1 to 86.3) enrolled in longitudinal studies of healthy aging and dementia through the Charles F. and Joanne Knight Alzheimer's Disease Research Center at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis [11]. Study participants were in good general health, with no other known medical illness that could contribute to dementia. Specifically, the following systemic diseases were screened: cancer (all type), heart disease (i.e., heart attack, atrial fibrillation, and congestive heart failure), hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, kidney, lung, and thyroid diseases. All participants had baseline body mass index (BMI) recorded. In addition, baseline fasting plasma and CSF samples were obtained from all subjects. CSF samples were analyzed for Aβ42, total tau, and tau phosphorylated at threonine 181 (p-tau181) by ELISA (INNOTEST; Innogenetics) as previously described [11]. Apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotypes were obtained from all participants [11].

Inclusion criteria for our analysis of these cohorts were (1) normal cognition at study entry (defined as having a Clinical Dementia Rating of 0) [12]; (2) BMI less than 30 to exclude obese subjects; and (3) availability of baseline fasting CSF and plasma samples.

This study was approved by the Human Research Protection Office at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and their informants.

2.2. Preclinical Alzheimer's disease status

Preclinical AD was defined as a CSF Aβ42 level <459 pg/mL, a previously established CSF criterion of preclinical AD for this cohort [11], [13]. Controls were all subjects who were amyloid-negative, defined as a CSF Aβ42 level ≥459 pg/mL. A secondary analysis was conducted by classifying preclinical AD using all three CSF AD biomarkers with cutoff points of CSF Aβ42 level <459 pg/mL, CSF tau level >339 pg/mL, and CSF p-tau181 level >67 pg/mL, as previously defined for this cohort [11].

2.3. Neuropsychological testing

All subjects underwent cognitive testing in the form of the Mini–Mental State Examination (MMSE, score range 0 to 30 with higher scores better) [14]. A subset of subjects also completed testing for immediate and delayed memory with Wechsler Memory Scale–Revised, Logical Memory (WMS-R-LM I & II; n = 82 controls and 32 preclinical AD subjects, score range 0 to 25 with higher scores better) [15] and executive function with Trail Making Test Parts A and B (n = 83 controls and 33 preclinical AD subjects, score range 0 to 180 seconds with higher scores worse) [16].

2.4. Plasma collection and lipocalin-2 measurement

Fasting plasma samples were collected at the baseline from all eligible study participants and were stored in frozen aliquots at -80°C at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. Deidentified aliquots were sent to Weill Cornell Medicine, where plasma levels of lipocalin-2 were measured by a commercial immunoassay (Catalog Number HADK1MAG-61K; MilliporeSigma) analyzed with the MAGPIX system (Luminex Corporation) following the manufacturers' protocols. All plasma samples were initially diluted 1:400 before running the immunoassay. A standard curve was constructed using known recombinant lipocalin-2 protein levels ranging from 3.2 to 50,000 pg/mL. The mean minimum detectable dose of lipocalin-2 for this immunoassay was 1.7 pg/mL. All samples were run in duplicates, and mean values were used. The mean %CV of replicates was 3.7%. For any samples found to be above the standard curve, the sample was diluted further to 1:2000 before rerunning the immunoassay. All values used are from samples with values found within the standard curve.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Variables were summarized as mean (standard deviation) and compared between groups using 2 tailed t-tests for continuous measures. For comparison between groups with categorical measures, Fisher's exact test was used. Associations between plasma lipocalin-2 and the individual CSF AD biomarker levels as continuous measures were examined by linear regression. As a significant difference in age was seen between preclinical and control groups, all of the multiple linear regression analyses were adjusted for age in addition to sex. Subgroup analyses were conducted to test for an interaction between APOE genotype (E4 carriers compared with non-E4 carriers) and plasma lipocalin-2 levels in relation to the individual CSF AD biomarkers. Associations between plasma lipocalin-2 and neuropsychological scores or BMI as continuous measures were examined by linear regression and were adjusted for age and sex. All tests were two-tailed, and the threshold of statistical significance was defined as P < .05. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 13.1 (StataCorp, TX).

3. Results

3.1. Demographic characteristics of study participants

A total of 156 subjects (65 men and 91 women) met all study criteria and had samples suitable for analysis. Using previously defined CSF criteria for preclinical AD [11], 38 subjects (20 male and 18 female) were categorized as being in the preclinical stage of AD based on CSF Aβ42 only. Of the 38 preclinical AD subjects, 22 subjects (15 male and 7 female) met all three CSF criteria (i.e., Aβ42, tau, and p-tau181). 118 subjects (45 male and 73 female) were categorized as amyloid-negative controls. Compared with control subjects, preclinical AD subjects had significantly lower CSF Aβ42 levels, higher CSF tau, and higher p-tau181 levels (Table 1). As expected, the preclinical AD group was older and had an increased percentage of subjects with at least one copy of the APOE ε4 allele as compared with biomarker negative control subjects (Table 1). The rest of the demographic characteristics, including education and race, were similar between the two groups. There were no significant differences between the control and preclinical AD groups in the proportion of cancer (all types), kidney disease, thyroid disease, heart disease (i.e., heart attack, atrial fibrillation, and congestive heart failure), hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes (all P > .05).

Table 1.

Study demographics and characteristics

| Control (n = 118) | Preclinical AD (n = 38) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex, number (%) | 73 (61.9) | 18 (47.4) | .13 |

| Age at lumbar puncture, mean (SD), years | 67.4 (7.7) | 72.8 (8.0) | ∗ |

| Caucasian, number (%) | 115 (97) | 38 (100) | .999 |

| CSF Aβ42, mean (SD), pg/mL | 778.7 (236.7) | 355.3 (74.0) | ∗ |

| CSF tau, mean (SD), pg/mL | 289.1 (165.3) | 453.8 (269.2) | ∗ |

| CSF p-tau181, mean (SD), pg/mL | 61.1 (31.1) | 77.1 (36.6) | .009 |

| APOE ε4 isoform carrier, number (%) | 31 (26.3) | 23 (60.5) | ∗ |

| Education, mean (SD), years | 16.1 (2.5) | 15.7 (2.7) | .41 |

| BMI, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 24.8 (2.8) | 24.2 (3.0) | .24 |

Abbreviations: APOE, apolipoprotein E; SD, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

Denotes P < .001.

3.2. Plasma lipocalin-2 levels are similar between men and women

Because circulating lipocalin-2 levels have been reported to be higher in men [17], we examined if plasma lipocalin-2 levels were different between men and women regardless of preclinical AD status. In our cohort, the plasma lipocalin-2 levels were not statistically different between males and females (men 76.4 ± 22.6 ng/mL vs. women 72.3 ± 20.3 ng/mL; P = .24). Therefore, plasma lipocalin-2 values from males and females were combined for all subsequent analyses.

3.3. Plasma lipocalin-2 levels are elevated in preclinical Alzheimer's disease and are associated with cerebrospinal fluid Aβ42 levels

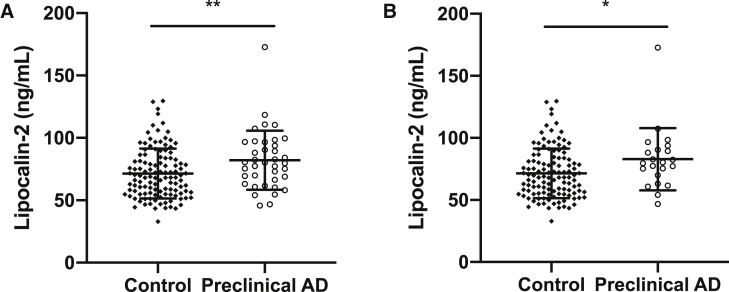

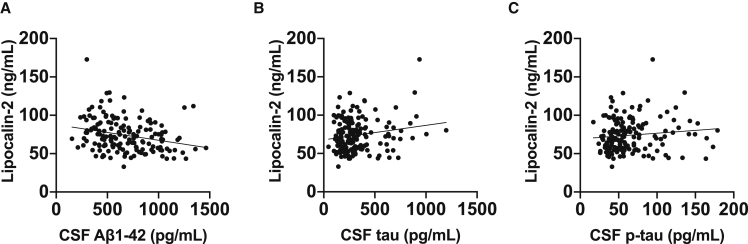

We then examined whether plasma lipocalin-2 levels were different between preclinical AD and control subjects. Compared with the control group, plasma lipocalin-2 levels were higher in the preclinical AD group (Fig. 1A). Reclassifying preclinical AD to include only subjects meeting all three CSF criteria (i.e., Aβ42, tau, and p-tau181) resulted in similar results of higher plasma lipocalin-2 levels in the preclinical AD group (Fig. 1B). In addition, plasma lipocalin-2 levels were associated with CSF levels of Aβ42 but not with CSF levels of tau or p-tau181 (Fig. 2). Subgroup analyses were conducted by APOE ε4 carrier status. There was no significant difference in plasma lipocalin-2 levels in APOE ε4 carriers compared with non-E4 carriers (E4 carriers 76.5 ± 21.0 ng/mL vs. non-E4 carriers 72.7 ± 21.5 ng/mL; P = .29). Furthermore, APOE ε4 carrier status did not interact significantly with plasma lipocalin-2 levels in relation to the individual CSF AD biomarkers (i.e., Aβ42, tau, or p-tau181) (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Plasma lipocalin-2 levels in preclinical AD group are higher than the control group. Lipocalin-2 levels were measured in fasting plasma samples by a commercial immunoassay. (A) Using CSF Aβ42 only as a criterion, preclinical AD group had higher plasma lipocalin-2 levels than control group (plasma lipocalin-2: 71.5 ± 20 for control and 82.0 ± 23.7 ng/mL, P = .007, n = 118 control and 38 preclinical AD subjects). (B) Using all three CSF AD biomarkers (Aβ42, tau, and p-tau181), plasma lipocalin-2 levels in preclinical AD group were higher than the control group (plasma lipocalin-2: 71.5 ± 20 for control and 82.9 ± 25.1 ng/mL, P = .0196, n = 118 control and 22 preclinical AD subjects). All individual values are presented with bars for means and standard deviations. *P < .05 and **P < .01. Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer's disease; Aβ, amyloid-beta; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

Fig. 2.

Association between plasma lipocalin-2 and CSF AD biomarkers. All subjects regardless of preclinical AD status were included in the analysis. (A) Plasma lipocalin-2 were significantly associated with CSF Aβ42 (age- and sex-adjusted, beta coefficient –0.213, P = .009). (B, C) However, plasma lipocalin-2 were not associated with CSF tau (age- and sex-adjusted, beta coefficient 0.0561, P = .46) or with CSF p-tau181 (age- and sex-adjusted, beta coefficient 0.018, P = .82). Scatterplots with individual values and unadjusted regression lines are shown. Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer's disease; Aβ, amyloid-beta; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

Table 2.

Association of plasma lipocalin-2 levels with CSF AD biomarkers

| CSF AD biomarker | APOE genotype | Beta coefficient | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSF Aβ42 levels | All | −0.213 | .009 |

| E4 carrier | −0.085 | .35∗ | |

| Non-E4 carrier | −0.261 | ||

| CSF tau levels | All | 0.0561 | .46 |

| E4 carrier | 0.100 | .34∗ | |

| Non-E4 carrier | 0.0151 | ||

| CSF p-tau181 levels | All | 0.018 | .82 |

| E4 carrier | −0.110 | .36∗ | |

| Non-E4 carrier | 0.101 |

All were adjusted for age and sex.

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer's disease; APOE, apolipoprotein E; Aβ, amyloid-beta; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

P value for the interaction between APOE ε4 carrier status and plasma lipocalin-2 in relation to the respective CSF AD biomarker levels.

3.4. Plasma lipocalin-2 levels are associated with executive function but not with episodic memory function

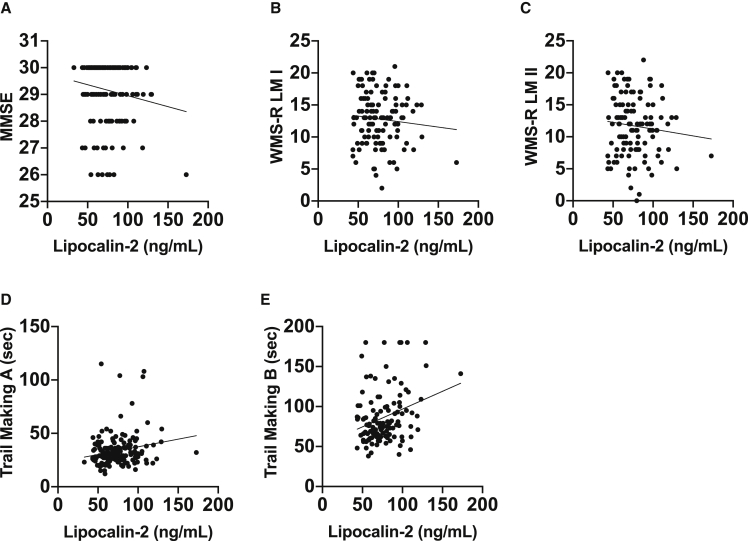

Exploratory analyses investigated whether there were any associations between plasma lipocalin-2 levels and select neuropsychological measures. We specifically focused on measures that can be affected during preclinical AD [18], [19] including overall cognitive function (MMSE), immediate and delayed episodic memory (WMS-R LM I & II), and executive function (Trail Making A and B). Despite preclinical AD subjects having a small but statistically significant lower MMSE score than control subjects (controls 29.3 ± 1.0 vs. preclinical AD 28.8 ± 1.3; P = .02), plasma lipocalin-2 levels were not associated with MMSE scores (Fig. 3). Preclinical AD subjects had lower scores on immediate memory (WMS-R LM I: controls 13.4 ± 3.0 vs. preclinical AD 11.4 ± 4.4; P = .02) but not delayed memory (WMS-R LM II: control 12.2 ± 4.2 vs. preclinical AD 10.5 ± 5.4; P = .08) as compared with controls. However, plasma lipocalin-2 levels were not associated with either immediate or delayed memory scores after adjusting for age and sex (Fig. 3). For executive function, preclinical AD subjects did worse on Trail Making B (controls 82.0 ± 30.9 seconds vs. preclinical AD 99.0 ± 36.9 seconds; P = .013) but not with Trail Making A (controls 34.5 ± 13.3 seconds vs. preclinical AD 40.9 ± 23.4 seconds; P = .07) compared with controls. Moreover, after adjusting for age and sex, plasma lipocalin-2 levels were associated with Trail Making B but not with Trail Making A scores (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Association between plasma lipocalin-2 and neuropsychological measures. All subjects regardless of preclinical AD status were included in the analysis. (A-D) Plasma lipocalin-2 levels were not associated with MMSE (age- and sex-adjusted, beta coefficient –0.0629, P = .42), WMS-R-LM I (age- and sex-adjusted, beta coefficient −0.0142, P = .46), WMS-R-LM II (age- and sex-adjusted, beta coefficient –0.0186, P = .831), and Trail Making A scores (age- and sex-adjusted, beta coefficient 0.145, P = .14). (E) Plasma lipocalin-2 levels were associated with Trail Making B scores (age- and sex-adjusted, beta coefficient 0.228, P = .014). Scatterplots with individual values and unadjusted regression lines are shown. Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer's disease; MMSE, Mini–Mental State Examination; WMS-R-LM, Wechsler Memory Scale–Revised, Logical Memory.

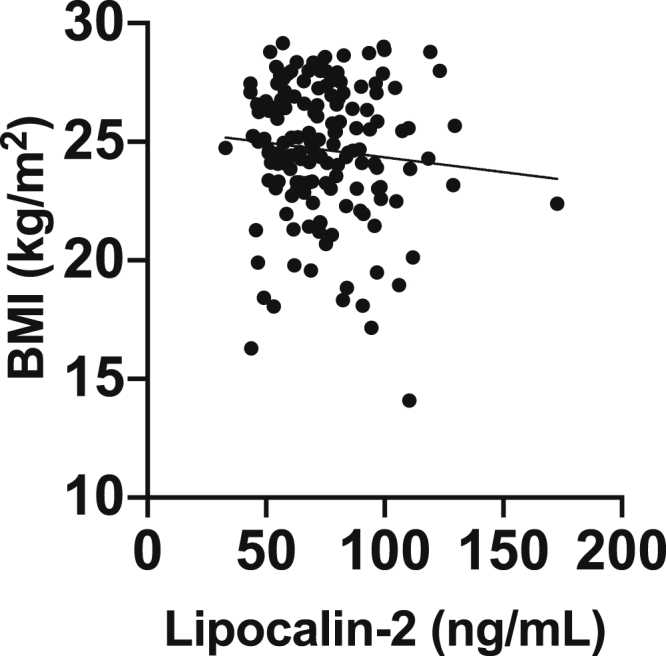

3.5. Plasma lipocalin-2 levels are not associated with body mass index in older nonobese individuals

Finally, in mouse models, circulating lipocalin-2 can act on the hypothalamus to decrease appetite and is regulated by obesity [20], [21]. However, whether lipocalin-2 is associated with BMI in humans remains inconclusive [17], [22]. Therefore, we examined the association between plasma lipocalin-2 levels and BMI and found that in this cohort of older nonobese individuals there was no significant association after adjusting for age and sex (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Association between plasma lipocalin-2 and BMI. BMI was not associated with plasma lipocalin-2 (age- and sex-adjusted, beta coefficient, –0.0864; P = .27). All individuals regardless of preclinical AD status or sex were included. Scatterplots with individual values and unadjusted regression lines are shown. Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer's disease; BMI, body mass index.

4. Discussion

In this cross-sectional study of cognitively normal community dwelling volunteers, plasma lipocalin-2 levels were significantly higher in subjects with CSF evidence of Aβ pathology consistent with preclinical AD. Importantly, the plasma lipocalin-2 levels were associated with CSF Aβ42 levels but not with CSF tau or p-tau181 levels, suggesting a link between circulating lipocalin-2 and Aβ pathology. Furthermore, exploratory analyses revealed that plasma lipocalin-2 levels were associated with a measure of executive function (Trail Making B) but not with episodic memory (WMS-R LM I & II) or overall cognition (MMSE). These findings support a role for circulating lipocalin-2 early in AD pathogenesis, and raise the possibility that this glycoprotein could be a biomarker of Aβ pathology and executive dysfunction.

The higher levels of plasma lipocalin-2 seen in preclinical AD are consistent with prior studies implicating lipocalin-2 in AD pathobiology [9], [23]. Lipocalin-2 has been hypothesized to be an important modulator of inflammation, neurotoxicity, and brain iron homeostasis, which may all contribute directly to AD pathogenesis [7], [8]. However, whether lipocalin-2 plays a significant role in AD pathogenesis is controversial. In mouse models, knocking-out the lipocalin-2 gene in the J20 mouse model of Aβ pathology significantly decreased the AD-like brain iron accumulation in the hippocampus but did not affect cognition, Aβ plaque load, and glial activation [24]. One possible explanation for the null effect, particularly in cognition, is that lipocalin-2 can act in a complex dual capacity of having a baseline beneficial role such as with hippocampal function but when induced to high levels, may be detrimental by enhancing neurotoxicity and promoting pathological iron accumulation in the brain [25], [26].

Although experimental models support a direct role for central lipocalin-2 in various aspects of AD pathogenesis [9], [23], the contribution, if any, of peripheral lipocalin-2 to AD pathogenesis is not clear. Because peripheral lipocalin-2 has been shown to cross the blood-brain barrier to modulate central pathways such as by activating hypothalamic neurons to decrease appetite [20], it is plausible for circulating lipocalin-2 to act on central processes involved early in AD pathogenesis including neuroinflammation, systemic metabolism, and brain iron homeostasis [7], [8]. As there was a lack of association between plasma lipocalin-2 and BMI in our cohort, the results from our study do not support peripheral lipocalin-2 contributing to the early dysregulation of body weight seen in preclinical AD [6]. We did not specifically assess brain iron levels or neuroinflammatory markers. Therefore, additional studies will be needed to elucidate any relation between peripheral lipocalin-2 and brain iron homeostasis or neuroinflammation.

Our exploratory analyses of neuropsychological measures found a significant association between plasma lipocalin-2 levels and Trail Making B scores, suggesting that lipocalin-2 is related to executive function. Furthermore, because Trail Making A is thought to provide a baseline measure of psychomotor speed, visuospatial search, and target-directed motor tracking, while Trail Making B is a more cognitively demanding task due to set-switching [27], the lack of an association with Trail Making A scores may signify that lipocalin-2 is only related to more challenging cognitive processing tasks of executive function rather than to simply psychomotor speed. These findings suggest that lipocalin-2 could be related specifically to brain regions that are important for executive function such as prefrontal and parietal structures and their connections [27]. Alternatively, it is possible that in our cohort, episodic memory or overall cognitive status is minimally affected, which would make it difficult to identify any association with these other neurocognitive measures and lipocalin-2. Indeed, we did not find any association between plasma lipocalin-2 levels and overall cognition by MMSE scores, although this type of brief screening measure is unlikely to be sensitive to subtle cognitive differences in asymptomatic individuals. This is in contrast to another study that found a positive association between plasma lipocalin-2 levels and MMSE scores in MCI and AD subjects [10]. Overall, the results from these neuropsychological tests have to be taken with caution as these are exploratory studies; all subjects are cognitively normal with the individual neurocognitive scores measured well within normal limits despite any statistically significant differences between preclinical AD and control subjects.

Regardless of the exact functional role of lipocalin-2, as an acute-phase protein, lipocalin-2 has been investigated as a possible biomarker that is modulated in a wide range of pathological conditions including several systemic disorders such as acute kidney injury and heart failure [7]. In our cohort, we found no significant difference between the preclinical AD and control groups in the proportion of cancer, kidney disease, thyroid disease, heart disease including congestive heart failure, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes. In addition, our cohort is in general good health with low probability for any significant acute pathologies. Therefore, it appears unlikely that systemic diseases are confounding our results.

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to investigate circulating lipocalin-2 in biomarker-defined preclinical AD. The higher plasma lipocalin-2 levels in preclinical AD subjects are consistent with similar findings of higher plasma lipocalin-2 levels in MCI subjects compared with cognitively normal subjects [10]. Furthermore, we had previously found that another member of the lipocalin family retinol binding protein 4 was not altered in preclinical AD [13], suggesting that alterations in plasma lipocalin-2 are not from a general pathological process affecting all lipocalins. However, circulating lipocalin-2 levels may differ with AD progression, as a cross-sectional study of normal, MCI, and AD subjects found the highest plasma lipocalin-2 levels in MCI subjects but AD subjects with more advanced disease had similar levels to normal controls [10]. This would be consistent with other studies showing a similar pattern of high levels of peripheral cytokines only in the early stages of AD [28], [29]. Interestingly, lipocalin-2 levels in the CSF may act differently than in the blood. In a similar fashion to Aβ, CSF lipocalin-2 levels have been reported to be significantly lower in clinically diagnosed MCI and AD subjects, whereas lipocalin-2 levels were increased in select postmortem brain regions affected by AD [9]. However, all of these prior studies did not confirm the diagnosis of AD with established AD biomarkers and were cross-sectional in nature. Future prospective longitudinal studies with AD biomarker-defined subjects will be needed to determine whether circulating or CSF lipocalin-2 levels changes with disease progression.

An important finding of our study is that plasma lipocalin-2 levels were negatively associated with CSF Aβ42 levels. This suggests that those individuals with significant Aβ pathology, as reflected by low CSF Aβ42 levels, have high plasma lipocalin-2 levels. Interestingly, serum lipocalin-2 was positively associated with plasma Aβ42 in Down syndrome individuals with dementia, which further supports a possible link between lipocalin-2 and Aβ [30]. In our study, the absolute difference in the plasma lipocalin-2 levels was modest with significant overlap between the groups. Based on these results, it is unlikely that plasma lipocalin-2 would contribute to the diagnosis of preclinical AD on an individual basis, but may serve as a nonspecific proxy for Aβ pathology.

A major strength of our study is the use of established CSF AD biomarkers in a well-characterized study cohort. Past studies have relied on clinical diagnosis of MCI or AD, which may lead to inaccurate categorization of study subjects and the inability to identify those individuals with AD pathology before detectable cognitive impairment. A limitation of this study is the cross-sectional nature and the inability to determine causality in the association between plasma lipocalin-2 and CSF Aβ42. In addition, the lack of CSF measurement of lipocalin-2 levels makes it difficult to discern any differences between central versus circulating lipocalin-2. Finally, the study cohort is relatively small, racially homogenous with high levels of education, which may lead to a selection bias that is common in studies conducted in a single academic medical center. Therefore, these results need to be verified and validated in additional prospective longitudinal studies with larger more diverse cohorts.

In conclusion, plasma lipocalin-2 levels were significantly higher in CSF biomarker defined preclinical AD subjects compared with biomarker negative control subjects. Furthermore, plasma lipocalin-2 levels were associated with CSF Aβ42 levels and executive function. Although the exact pathophysiological role of lipocalin-2 in AD remains controversial and verification of these results in additional prospective studies are needed, these results support circulating lipocalin-2 as a marker of early Aβ pathology.

Research in Context.

-

1.

Systematic review: Review of 15+ years of literature (e.g., PubMed) on the relation between lipocalin-2 (also known as neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin, 24p3, or siderocalin) and Alzheimer's disease (AD) revealed results from human studies to be inconclusive, which may be from lack of validation of the clinical diagnosis with AD biomarkers. In addition, there were no studies that measured plasma lipocalin-2 in biomarker-confirmed preclinical AD.

-

2.

Interpretation: The results from this cross-sectional study support lipocalin-2 playing a role early in AD pathogenesis and plasma lipocalin-2 as a potential early blood biomarker of amyloid-beta pathology.

-

3.

Future directions: Additional research is needed to validate these findings in larger more diverse cohorts and in longitudinal studies. The use of cerebrospinal fluid lipocalin-2 as a potential AD biomarker and any differences with plasma lipocalin-2 should be clarified. Finally, the role of lipocalin-2 in iron metabolism and neuroinflammation in biomarker-confirmed AD should be explored.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the volunteers for participating in the study. The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Drs. Anne Fagan, Betsy Grant, Krista Moulder, John Morris, and David Holtzman, the core facilities of The Charles F. and Joanne Knight Alzheimer's Disease Research Center (P50 AG05681), Healthy Aging and Senile Dementia (P01 AG03991), and Adult Children Study (P01 AG026276) for providing biospecimens and associated clinical, biomarker, and psychometrics data. The authors thank Mr. Matthew McGuire, Ms. Laurie Pham, and Ms. Abigail Hiller for providing technical or administrative assistance. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (UL1TR002384, K08AG051179, K23NS082367, and R01NS37853) and the BrightFocus Foundation (A2015485S). The support of Lauren and Andy Weisenfeld is gratefully acknowledged. The sponsors did not have any role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the article.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: Dr. Ishii owns stock in Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. No other disclosures were reported.

References

- 1.Sperling R.A., Aisen P.S., Beckett L.A., Bennett D.A., Craft S., Fagan A.M. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dubois B., Hampel H., Feldman H.H., Scheltens P., Aisen P., Andrieu S. Preclinical Alzheimer's disease: Definition, natural history, and diagnostic criteria. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12:292–323. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jack C.R., Bennett D.A., Blennow K., Carrillo M.C., Dunn B., Haeberlein S.B. NIA-AA Research Framework: toward a biological definition of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14:535–562. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Honig L.S., Vellas B., Woodward M., Boada M., Bullock R., Borrie M. Trial of Solanezumab for mild dementia due to Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:321–330. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1705971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kinney J.W., Bemiller S.M., Murtishaw A.S., Leisgang A.M., Salazar A.M., Lamb B.T. Inflammation as a central mechanism in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 2018;4:575–590. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2018.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hiller A.J., Ishii M. Disorders of body weight, sleep and circadian rhythm as manifestations of hypothalamic dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Cell Neurosci. 2018;12:471. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2018.00471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferreira A.C., Da Mesquita S., Sousa J.C., Correia-Neves M., Sousa N., Palha J.A. From the periphery to the brain: Lipocalin-2, a friend or foe? Prog Neurobiol. 2015;131:120–136. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiao X., Yeoh B.S., Vijay-Kumar M. Lipocalin 2: an emerging player in iron homeostasis and inflammation. Annu Rev Nutr. 2017;37:103–130. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-071816-064559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naudé P.J.W., Nyakas C., Eiden L.E., Ait-Ali D., van der Heide R., Engelborghs S. Lipocalin 2: novel component of proinflammatory signaling in Alzheimer's disease. Faseb J. 2012;26:2811–2823. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-202457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi J., Lee H.-W., Suk K. Increased plasma levels of lipocalin 2 in mild cognitive impairment. J Neurol Sci. 2011;305:28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2011.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vos S.J., Xiong C., Visser P.J., Jasielec M.S., Hassenstab J., Grant E.A. Preclinical Alzheimer's disease and its outcome: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:957–965. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70194-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morris J.C. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) Neurology. 1993;43:2412–2413. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishii M., Kamel H., Iadecola C. Retinol binding protein 4 levels are not altered in preclinical Alzheimer's disease and not associated with cognitive decline or incident dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;67:257–263. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Folstein M.F., Folstein S.E., McHugh P.R. “Mini-mental state.” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wechsler D. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio: 1987. Wechsler Memory Scale - Revised Edition. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reitan R.M., Wolfson D. Neuropsychology Press; Tucson: 1985. The Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y., Lam K.S.L., Kraegen E.W., Sweeney G., Zhang J., Tso A.W.K. Lipocalin-2 is an inflammatory marker closely associated with obesity, insulin resistance, and hyperglycemia in humans. Clin Chem. 2007;53:34–41. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.075614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen P., Ratcliff G., Belle S.H., Cauley J.A., DeKosky S.T., Ganguli M. Patterns of cognitive decline in presymptomatic Alzheimer disease: a prospective community study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:853–858. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.9.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mortamais M., Ash J.A., Harrison J., Kaye J., Kramer J., Randolph C. Detecting cognitive changes in preclinical Alzheimer's disease: a review of its feasibility. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13:468–492. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.06.2365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mosialou I., Shikhel S., Liu J.-M., Maurizi A., Luo N., He Z. MC4R-dependent suppression of appetite by bone-derived lipocalin 2. Nature. 2017;543:385–390. doi: 10.1038/nature21697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yan Q.-W., Yang Q., Mody N., Graham T.E., Hsu C.-H., Xu Z. The Adipokine Lipocalin 2 is regulated by obesity and promotes insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2007;56:2533–2540. doi: 10.2337/db07-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elkhidir A.E., Eltaher H.B., Mohamed A.O. Association of lipocalin-2 level, glycemic status and obesity in type 2 diabetes mellitus. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10:285. doi: 10.1186/s13104-017-2604-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mesquita S.D., Ferreira A.C., Falcao A.M., Sousa J.C., Oliveira T.G., Correia-Neves M. Lipocalin 2 modulates the cellular response to amyloid beta. Cell Death Differ. 2014;21:1588–1599. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dekens D.W., Naudé P.J.W., Keijser J.N., Boerema A.S., De Deyn P.P., Eisel U.L.M. Lipocalin 2 contributes to brain iron dysregulation but does not affect cognition, plaque load, and glial activation in the J20 Alzheimer mouse model. J Neuroinflammation. 2018;15:330. doi: 10.1186/s12974-018-1372-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferreira A.C., Pinto V., Mesquita S.D., Novais A., Sousa J.C., Correia-Neves M. Lipocalin-2 is involved in emotional behaviors and cognitive function. Front Cell Neurosci. 2013;7:122. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mucha M., Skrzypiec A.E., Schiavon E., Attwood B.K., Kucerova E., Pawlak R. Lipocalin-2 controls neuronal excitability and anxiety by regulating dendritic spine formation and maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:18436–18441. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107936108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Varjacic A., Mantini D., Demeyere N., Gillebert C.R. Neural signatures of Trail Making Test performance: Evidence from lesion-mapping and neuroimaging studies. Neuropsychologia. 2018;115:78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2018.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.King E., O’Brien J.T., Donaghy P., Morris C., Barnett N., Olsen K. Peripheral inflammation in prodromal Alzheimer's and Lewy body dementias. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018;89:339–345. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2017-317134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Motta M., Imbesi R., Di Rosa M., Stivala F., Malaguarnera L. Altered plasma cytokine levels in Alzheimer's disease: correlation with the disease progression. Immunol Lett. 2007;114:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naudé P.J.W., Dekker A.D., Coppus A.M.W., Vermeiren Y., Eisel U.L.M., van Duijn C.M. Serum NGAL is associated with distinct plasma amyloid-β peptides according to the clinical diagnosis of dementia in Down syndrome. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;45:733–743. doi: 10.3233/JAD-142514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]