Abstract

Birds present a stunning diversity of plumage colors that have long fascinated evolutionary ecologists. Although plumage coloration is often linked to sexual selection, it may impact a number of physiological processes, including microbial resistance. At present, the degree to which differences between pigment-based vs. structural plumage coloration may affect the feather microbiota remains unanswered. Using quantitative PCR and DGGE profiling, we investigated feather microbial load, diversity and community structure among two allopatric subspecies of White-shouldered Fairywren, Malurus alboscapulatus that vary in expression of melanin-based vs. structural plumage coloration. We found that microbial load tended to be lower and feather microbial diversity was significantly higher in the plumage of black iridescent males, compared to black matte females and brown individuals. Moreover, black iridescent males had distinct feather microbial communities compared to black matte females and brown individuals. We suggest that distinctive nanostructure properties of iridescent male feathers or different investment in preening influence feather microbiota community composition and load. This study is the first to point to structural plumage coloration as a factor that may significantly regulate feather microbiota. Future work might explore fitness consequences and the role of microorganisms in the evolution of avian sexual dichromatism, with particular reference to iridescence.

Subject terms: Microbial ecology, Coevolution, Environmental microbiology

Introduction

Avian plumage is a unique integumentary structure that is critical for multiple functions including flight1–3, thermoregulation4–6, and socio-sexual communication7,8. Feather coloration is a product of deposited pigments (e.g. carotenoids, melanins and psittacofulvins) responsible for pigment coloration9,10, feather integumentary nanostructures responsible for structural coloration11–13, or a combination of both14–17. Elaboration of feather coloration generated by combinations of these factors is considered to be primarily driven by sexual selection18. In this context, studies have demonstrated that variation in pigment-based and structural plumage coloration is under sexual selection by advertising quality and/or reproductive success16,19–22. Carotenoid-based coloration is more prone to diet, foraging strategy and an individual’s physiological state23–25. On the contrary, association between melanin-based plumage coloration and reproductive parameters and/or survival in birds is species-specific and dependent on adaptation to local environmental conditions26,27 that may include interactions with omnipresent microorganisms.

Feathers are subject to exposure to the external environment and host diverse microbial communities28–31 including antibiotic compounds-producing microorganisms31, pathogens32 or feather-degrading bacteria29,33. The latter can deteriorate feather structure34,35 and negatively affect signaling function of both pigment based and structural plumage coloration36–38. In addition, plumage bacterial load may significantly impair individual immunity and fitness39–41. However, experimental evidence suggests that feather pigments, particularly melanins and also parrot psittacofulvins, significantly improve resistance of feathers against bacterial degradation34,42,43. Moreover, feather melanization was found to inhibit attachment and colonization of keratinolytic bacterium B. licheniformis on black- and white-striped feathers44. Prevention of feather bacterial degradation via increased deposition of melanins into the feathers is one functional explanation in several studies that have documented more melanized individuals in colder, wetter and more densely vegetated habitats45–48. Yet, a study comparing feather microbial load and diversity in individuals adopting different melanin-based plumage phenotypes in natural population of birds is lacking.

Recent studies have highlighted the role of structural based plumage coloration such as iridescence, in the evolution of avian plumage coloration and dichromatism13,49–51. Iridescent feathers (which seem to be ancestral in birds52) have decreased hydrophobicity53 and are more sensitive to bacterial degradation54, which provide a potential mechanism for honest signaling of individual quality. However, increased plumage bacterial load has been shown to diminish brightness of iridescent neck feathers in pigeons38. Moreover, iridescent plumage phenotypes show greater diversity in tropical and sub-tropical species12,49,55–58 that are exposed to higher and more diversified microbial loads59,60. It follows, therefore, that apart from a protective role of feather pigments, birds may have developed other defense mechanisms for preventing detrimental effects of external parasites including microorganisms on feather wear61.

To date, no study has investigated the relationship between iridescent plumage phenotype and indices of feather microbiota in free living populations of birds. In the present study, we used molecular approaches to investigate feather microbial load and diversity in two populations of a tropical passerine bird, the White-shouldered Fairywren (Malurus alboscapulatus), of New Guinea that vary in the extent of melanin-based and structural plumage coloration both between populations and between sexes. No other study has investigated the consequences of feather microbial load and diversity for divergent plumage phenotypes in melanin-based and structural coloration for a natural bird population. We leverage this unique variation to ask how feather microbial load and diversity varies between plumage phenotypes and discuss mechanistic underpinnings and consequences for plumage signaling and evolution.

Material and Methods

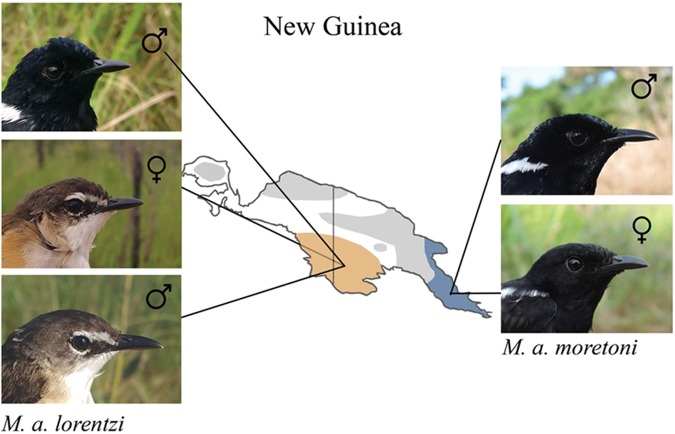

We analyzed feather microbial load, diversity and community profile in two subspecies of White-shouldered Fairywren (family Maluridae, Meyer, 1874), a socially breeding, tropical, insectivorous passerine endemic to grassland environments62 in New Guinea. Both subspecies are sexually dichromatic, yet their plumage phenotypes differ in melanin-based and structural coloration. While females and first year males of subspecies M. a. lorentzi are brown dorsally and white ventrally63 (“brown individuals” hereinafter), adult males are black with white shoulder patches including an iridescent blue satin sheen. In contrast, males and females of M. a. moretoni exhibit cryptic sexual dichromatism as they are similar in appearance and both are black with white shoulder patches, yet black females are matte, lack the male’s iridescent blue satin sheen and have lower barbule density compared to iridescent black males64 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Photographs and localities (i.e. populations) of White-shouldered Fairywren subspecies included in this study and sampled in Papua New Guinea. Within the M. a. lorentzi subspecies, we sampled white chest feathers from brown females and first-year males and black chest feathers from iridescent males, while within M. a. moretoni subspecies, black chest feathers from ornamented black males with iridescent plumage and black females with matte plumage were sampled (photographs: Erik D. Enbody).

All individuals were sampled under permit 2194 issued by the Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme and protocols were reviewed under the Tulane University IACUC number 0395 and all experiments were performed in accordance with relevant institutional guidelines and regulations.

Study area and sampling procedure

We collected chest contour feathers from 24 individuals of White-shouldered Fairywren that were mist-netted during February-March 2016 in two provinces of Papua New Guinea. Specifically, white chest feathers from two first-year males and three females of the subspecies M. a. lorentzi were sampled in Western Province, Papua New Guinea (141°19′E, 7°35′S, 10–20 m ASL; Fig. 1). Black chest feathers from four matte black females of the M. a. moretoni subspecies were sampled in Milne Bay Province, Papua New Guinea (150°30′E, 10°15′S, 0–20 m ASL; Fig. 1) and fifteen iridescent black males were sampled between two allopatric subspecies populations; Western Province (n = 11), and Milne Bay Province (n = 4).

Chest contour feathers (approx. 10–15) were plucked from each individual using sterile forceps and immediately placed into a sterile tube filled with 1 mL of 96% sterile-filtered ethanol. To avoid contamination, feathers for microbiological analyses were collected directly from individuals trapped in mist net (i.e. prior to handling). After removing the individuals from the mist net, age and sex of each individual was assigned. We also collected a blood sample from each brown individual of M. a. lorentzi and stored it in Longmire’s lysis buffer for subsequent genetic determination of sex.

Sex identification

We assigned sex in the field to individuals with cloacal protuberances, brood patches, or sex-specific plumage phenotypes. As first year males and adult females of M. a. lorentzi are apparently identical in appearance (Fig. 1), we used molecular markers to sex the five brown individuals sampled in this population. We extracted DNA from blood samples using a DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen) and amplified a sex-specific intron within the CHD gene using primers 2550F/2718R65. We ran CHD intron fragments through electrophoresis using a 2% agarose minigel and stained with SYBR Safe DNA gel stain (Life Technologies). Bands were scored visually following66, using positive controls to confirm accuracy.

Analyses of feather microbial load and diversity

DNA extraction

To measure feather microbial load and diversity, microbial genomic DNA was isolated from feather samples stored in ethanol. See Supplementary Material and Methods for complete DNA extraction protocol.

Quantification of feather microbial load

To analyze feather microbial load, we used quantitative PCR targeting 16S rRNA in extracted microbial DNA from feather samples using a LightCycler®480 Instrument (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). See Supplementary Material and Methods for complete qPCR amplification conditions.

Analysis of feather microbial diversity and community profiling

Denaturing Gradient Gel Electrophoresis (DGGE) was used to assess feather microbial diversity and community profile. See supplementary Material and Methods for detailed DGGE protocol.

DGGE gel image was processed in BioNumerics software v 7.6 (Applied Maths, Belgium) for normalization, bands detection and band matching table construction. Bands were detected using the band-search algorithm with densitometric curves describing the optical density along each lane and enabling background subtraction. Band detection criterions was set as 5% relative to maximum densitometric value of lane to eliminate uncertain bands. Then, for each sample running on DGGE gel, the number of Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) and Shannon-Wiener diversity index (Hsw) were calculated based on equation:

where n is the total number of bands, hi the intensity of the individual band i and H the total intensity of all bands in a profile, were calculated. Band matching tables were computed using band densitometric peak height, peak surface, and 2D band areas. We measured the relative OTUs abundances with band matching optimization and tolerance set as 0.5%. This semi-quantitative band matching table was used for the computation of Bray-Curtis and Jaccard distance matrices using the R package phyloseq.67.

Taxonomy of feather microbial communities

To identify the most representative and abundant bacteria within White-shouldered Fairywren plumage microbial communities, the 12 most pronounced DGGE bands (see Supplementary Fig. S1) were cut out of the stained polyacrylamide gels by the sterile scalpel in a dark room on a UV light-box. DNA was eluted by the addition of 100 µL of sterile dH2O and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 minutes. Then, 2 µL of this solution with primers FP341 (5′-CCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3′) and RP534 (see above) was used for amplification under the PCR-DGGE program68. The resulting PCR products were cleaned with QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Germany) and sequenced using standard Sanger methods from both sides (SeqMe service, Czech Republic).

Taxonomy assignment of obtained representative sequences were done with the RDP classifier69 by combining the Greengenes database (version 13_8)70 with 80% posterior probability limit and Geneious Prime (version 2019.0.4). To assess prevalence of the most representative OTUs among plumage phenotypes, presence vs. absence data for all 12 sequenced DGGE bands within White-shouldered Fairywren indiviudals was extracted from the normalised DGGE gel (see Supplementary Fig. S1) using Bionumerics software v 7.6 (Applied Maths, Belgium). Heatmap showing the phylogeny and prevalence of the 12 representative OTUs (i.e. DGGE bands) within White-shouldered Fairywren plumage phenotypes were generated using the R packages ggtree71 ape72 and ggplot273.

Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed in RStudio (Version 1.1.453)74. We used Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) models with log-transformed 16S rRNA copy number per mg of feather and Shannon diversity index as response variables to evaluate factors affecting differences in feather microbial load, and feather microbial alpha diversity in White-shouldered Fairywren subspecies, respectively. Plumage phenotype (brown vs. black), sex (male vs. female) nested within plumage phenotype, and age coded as binary variable (0 = first-year birds, 1 = birds older than first-year) were included as categorical explanatory variables in each ANOVA model. Tukey HSD post-hoc tests were used for multiple comparison of significant effects and their means between tested categories.

Iridescent black males were sampled in two geographically distinct populations; Milne Bay and Western (see Material and Methods for details), and we used Welch’s Two Sample t-test due to unequal variance in the case of microbial load, and Student’s t-test in the case of alpha diversity testing between-population effect on feather microbial load and diversity.

To assess factors responsible for divergence in similarity (i.e. β-diversity) of feather microbial communities among White-shouldered Fairywren individuals, we used a PERMANOVA permutation test (R package vegan, function: adonis) by fitting a linear model based on both Bray-Curtis and presence/absence version of Jaccard similarity coefficients including plumage phenotype (brown vs. black) sex (male vs. female) nested within plumage phenotype and age as response variables. Due to unbalanced sampling design, we also assessed heterogeneity of variance (i.e. inter-individual variation of feather microbiota composition) between plumage phenotypes using the betadisper function75. Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) was used to visualize among-sample divergence in composition of feather microbial communities.

Results

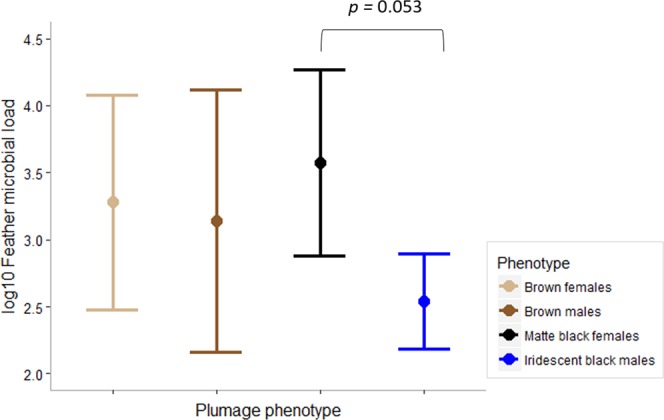

Feather microbial load

We found sex nested within plumage phenotype as significant predictor of White-shouldered Fairywren microbial load (ANOVA: F(2,21) = 3.856, p = 0.038), with iridescent black males tended to have lower feather microbial loads than did matte black females (Tukey’s HSD test: p = 0.053; Table S1, Fig. 2). However, neither iridescent black males nor matte black females significantly differed in feather microbial load compared to brown individuals (Table S1, Fig. 2). Moreover, there was no effect of individual’s age on feather microbial load (ANOVA: F(1,22) = 0.252, p = 0.621).

Figure 2.

Differences (mean ± 95% CI) in feather microbial load (log10 16S rRNA copy numbers per mg of feather) between White-shouldered Fairywren plumage phenotypes. Significant differences are based on Tukey’s HSD.

We found no differences in microbial loads of iridescent black males sampled in the two geographically distinct populations (Welch Two sample t-test: t = −1.398, df = 8.825, p = 0.196).

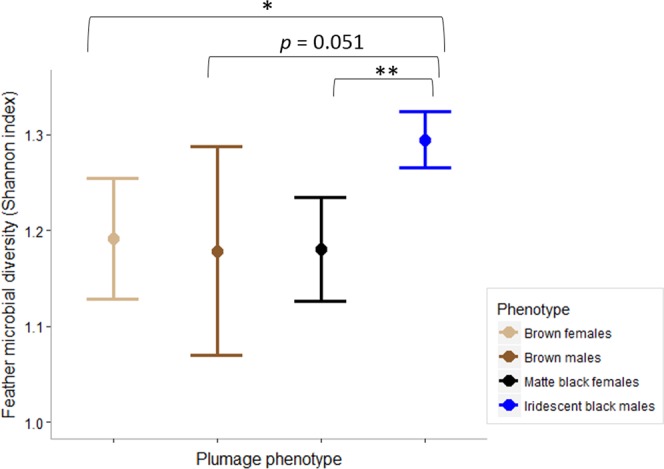

Feather microbial diversity and taxonomic profile

Alpha diversity of feather microbial communities varied within sex nested in plumage phenotypes (ANOVA: F(2,21) = 11.555, p < 0.001) with iridescent black males having significantly more diversified microbial communities than matte black females (Tukey’s HSD test: p = 0.001, Table S2, Fig. 3), brown females (Tukey’s HSD test: p = 0.017; Table S2, Fig. 3) and brown males where the effect was marginally non-significant (Tukey’s HSD test: p = 0.051; Table S2, Fig. 3). Effect of age on feather microbial alpha diversity was not significant (ANOVA: F(1,22) = 1.668, p = 0.213). In addition, we did not find between-population differences in feather microbial alpha diversities between iridescent black males sampled in two geographically distinct populations (Student’s Two sample t-test: t = −1.375, df = 12, p = 0.194).

Figure 3.

Differences (mean ± 95% CI) in feather microbial α-diversity (Shannon-Wiener index) between White-shouldered Fairywren plumage phenotypes. Significant differences are based on Tukey’s HSD (statistical significance: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

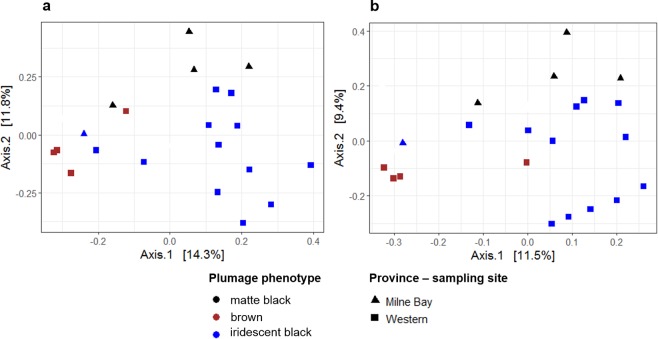

Similarity (i.e. β-diversity) of feather microbial communities between White-shouldered Fairywren individuals was best explained by sex nested in plumage phenotype (PERMANOVAs: Bray-Curtis - 23% variance explained, F = 1.571, p = 0.001; Jaccard - 21% variance explained, F = 1.380, p = 0.002) with age having no significant effect (PERMANOVAs: Bray-Curtis - 10% variance explained, F = 1.361, p = 0.054; Jaccard - 9% variance explained, F = 1.147, p = 0.135). Heterogeneity of inter-individual variance among plumage phenotypes was significant for Bray-Curtis (betadisper: F = 26.123, p < 0.001) as well as Jaccard (betadisper: F = 37.400, p < 0.001). PCoA ordination shown that composition of feather microbial communities of iridescent black males varied from microbial communities of matte black females and brown individuals (Fig. 4a,b). PCoA visualization of between-population microbial community divergence showed no apparent dissimilarities in feather microbial community profiles of iridescent black males sampled in geographically distinct populations (Fig. 4a,b).

Figure 4.

Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) for among-sample divergence in composition (β-diversity) of White-shouldered Fairywren feather microbial communities based on (a) Bray-Curtis and (b) Jaccard dissimilarities. Different colors denoted plumage phenotypes and different shapes geographically distinct provinces (i.e. sampling localities).

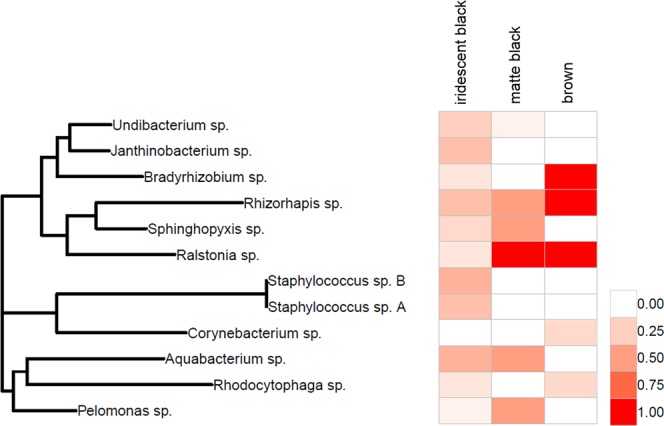

Taxonomic composition of the most representative feather microorganisms was dominated by the phyla Betaproteobacteria, Alphaproteobacteria, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria and Bacteroidetes. Prevalence of the most representative bacterial genera differed among plumage phenotypes, with brown individuals dominated by the genera Bradyrhizobium, Rhizorhapis and Ralstonia while black individuals hosted other genera with various prevalence depending on presence/absence of structural coloration (Fig. 5). A detailed taxonomy of the most representative bacterial genera found in White-shouldered Fairywren plumage and their prevalence among plumage phenotypes is presented in Fig. 5.

Figure 5.

Heatmap showing taxonomic assignment and prevalence (%) of the most representative microbial genera detected in feather of White-shouldered Fairywren with different plumage phenotypes.

Discussion

We show that the presence or absence of iridescent plumage, not melanized plumage per se, was associated with differences in feather microbiota in free-living populations of a tropical bird. Iridescent black males had the lowest feather microbial load, the highest microbial diversity and harbored a distinct microbial community relative to brown and matte black individuals of either sex. Our findings regarding feather microbial load are inconsistent with a recent study investigating bacterial load on ornamental throat feathers in free-living population of spotless starling (Sturnus unicolor), which documented higher bacterial load on iridescent feathers compared to un-ornamented adjacent or female feathers54.

Most existing research has shown that feather microbial diversity and community structure are primarily driven by horizontal transmission of microbes from the environment31,76. However, species-specific feather microorganisms that are able to produce antimicrobial substances31, or particular chemical substances contained in preen gland secretions77–79 may also affect feather microbiota diversity. Our data show that iridescent individuals originating from two geographically (>1000 km apart) and ecologically distinct populations63 do not differ in feather microbial diversity and harbor similar microbial communities on their feathers. Due to the similarity in microbial communities between individuals living in different environments, it is unlikely that horizontal transmission of microbes from the environment drive differences we observe in microbiota communities. Instead, chemical composition of preen gland secretions or physical properties of iridescent feathers based on UV reflectance and absorbance of solar radiation may be more important contributors to feather microbiota diversity and community structure in iridescent individuals.

We found no evidence that feather melanization impacts White-shouldered Fairywren feather microbiota. These findings did not necessarily exclude the hypothesis that melanins play a protective role against bacterial degradation of plumage34,35,46,48, as we did not directly test changes in degradability of differently melanized White-shouldered Fairywren feathers. Existing evidence suggests a preferential colonization and attachment of bacteria on white (i.e. non-melanized) compared to black (i.e. fully melanized) feathers or feather parts44,80, which we did not observe in our study system. A negative correlation between feather melanization and preening effort has been shown in barn owls81, suggesting that it is possible that brown individuals balance the feather microbiota via increased preening effort compared to matte black individuals that may comparatively invest less into the preening.

White-shouldered Fairywren individuals with iridescent feathers tended to have reduced feather microbial load compared to non-ornamented individuals. One possible explanation for this is differences in investment for plumage maintenance. Presently, we have no observational data proving that iridescent White-shouldered Fairywren individuals invest more into preening, but there is evidence that ornamented males of the Red-backed Fairywren (Malurus melanocephalus), the White-shouldered Fairywren’s sister species, preen at higher rates than do unornamented males (J. Karubian, unpublished data). In other avian species, studies have documented that preening behavior can significantly reduce feather microbial load38,82, enhance feather condition including waterproofness83, or increase feather visual signaling properties84,85. There is also evidence for associations between degree of feather microbial load and preen gland size86–88 supporting significant role of preen gland and its secretions in alterations of feather microbiota. Furthermore, allopreening (e.g. preening between mates) is important for maintaining social bonds across the genus Malurus62 and may be a mechanism through which male iridescent plumages are maintained by reducing microbial load. In this sense, our findings may be consistent with the “attractive preening” hypothesis, which suggests that ornamental iridescent plumage is linked with increased investment in plumage maintenance via preening89, which may come with a high energetic costs39,90 and may thus reflect bearer quality91.

However, it is certainly possible that other factors may drive this pattern. For example, iridescent plumage in this system differs in terms of nanostructure from non-iridescent plumage64, which may in turn influence many physical properties, including solar reflectivity92. It has been hypothesized that iridescent nanostructuring of feathers might reduce heat loss of colorful sexually selected pigment-based coloration by reflecting solar energy92 and iridescent feathers often have reflectance peaks in UVA and UVB spectrum93,94, which may inactivate or be lethal for most microorganisms95–97. Consequently, the solar heat absorption properties of iridescent feathers might have temperature-dependent effects on microorganisms present on feathers. Some of the bacterial genera detected in our study (Staphylococcus, Aquabacterium) and having different prevalences among plumage phenotypes, have been found in digestive tract of feather mites98. Consequently, another explanation is that feather mites may act as effector symbionts able to digest and thus selectively affect (based on plumage phenotype) feather microbiota99, which has been found in other species98. Feather mites have been detected on White-shouldered Fairywrens (E. Enbody, unpublished data), but further testing is needed to evaluate the interplay between feather mites and microbiota in this system.

Our observation of distinct microbiota communities and abundance between feather types suggests an overlooked role for structural coloration in complex plumage evolution and for the wild microbiome in host evolution. A better understanding of the proximate mechanisms behind the documented association between iridescent plumage phenotype and feather microbiota diversity, particularly in relation to preening gland secretions chemistry and preening behavior, is a priority for future research into the feather microbiome and plumage evolution.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Czech Science Foundation project Number 14-16861P and the National Science Foundation (Award Number 1354133 to Jo.K. and 1701781 to Jo.K. and E.D.E.). Many thanks also go to Eva Holánová for her help with laboratory work and Radka Valterová for sample sorting. We appreciate assistance in the field from R. Biggoneau, P. Chaon, G. Kareba, S. Ketaloya, D. Nason, K. Saiga, and M. Saiga. We also thank the local landowners in the villages of Garuahi, Porotona, and Obo for permissions for field data collection.

Author Contributions

V.G.J. developed the study concept, experimental design, obtained funding, is responsible for sample processing, laboratory (qPCR) and complete data analyses and wrote the manuscript; E.D.E. conducted bird sampling, bird sexing and wrote the manuscript; J.K. substantially contributed to statistical analyses (ordination methods, heatmap and PERMANOVA) and reviewed the manuscript, K.C.H. arranged fieldwork and reviewed the manuscript; J.M. conducted DGGE analysis, provided sequence data and reviewed the manuscript; Jo.K. obtained funding, wrote and revised the manuscript.

Data Availability

The nucleotide sequence data reported are uploaded in the GenBank database under the submission Numbers: MK215669, MK215670, MK215671, MK215672, MK215673, MK215674, MK215675, MK215676, MK215677, MK215678 and MK215679. The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-49220-y.

References

- 1.Echeverry-Galvis Maria Angela, Hau Michaela. Flight Performance and Feather Quality: Paying the Price of Overlapping Moult and Breeding in a Tropical Highland Bird. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(5):e61106. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tomotani BM, Muijres FT, Koelman J, Casagrande S, Visser ME. Simulated moult reduces flight performance but overlap with breeding does not affect breeding success in a long-distance migrant. Funct. Ecol. 2018;32:389–401. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.12974. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pap PL, et al. Interspecific variation in the structural properties of flight feathers in birds indicates adaptation to flight requirements and habitat. Funct. Ecol. 2015;29:746–757. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.12419. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osvath G, et al. How feathered are birds? Environment predicts both the mass and density of body feathers. Funct. Ecol. 2018;32:701–712. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.13019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butler LK, Rohwer S, Speidel MG. Quantifying structural variation in contour feathers to address functional variation and life history trade-offs. J. Avian Biol. 2008;39:629–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-048X.2008.04432.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pap PL, et al. A phylogenetic comparative analysis reveals correlations between body feather structure and habitat. Funct. Ecol. 2017;31:1241–1251. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.12820. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Penteriani Vincenzo, Delgado María del Mar. Living in the dark does not mean a blind life: bird and mammal visual communication in dim light. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2017;372(1717):20160064. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2016.0064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moller AP, Cuervo JJ. Speciation and feather ornamentation in birds. Evolution. 1998;52:859–869. doi: 10.2307/2411280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galván Ismael, Solano Francisco. Bird Integumentary Melanins: Biosynthesis, Forms, Function and Evolution. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2016;17(4):520. doi: 10.3390/ijms17040520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.LaFountain AM, Prum RO, Frank HA. Diversity, physiology, and evolution of avian plumage carotenoids and the role of carotenoid-protein interactions in plumage color appearance. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2015;572:201–212. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2015.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Igic B, D’Alba L, Shawkey MD. Manakins can produce iridescent and bright feather colours without melanosomes. J. Exp. Biol. 2016;219:1851–1859. doi: 10.1242/jeb.137182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doucet SM, Shawkey MD, Hill GE, Montgomerie R. Iridescent plumage in satin bowerbirds: structure, mechanisms and nanostructural predictors of individual variation in colour. J. Exp. Biol. 2006;209:380–390. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shawkey MD, D’Alba L. Interactions between colour-producing mechanisms and their effects on the integumentary colour palette. Philos. T. R. Soc. B. 2017;372:9. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2016.0536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D’Alba L, et al. Melanin-Based Color of Plumage: Role of Condition and of Feathers’ Microstructure. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2014;54:633–644. doi: 10.1093/icb/icu094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eliason Chad M., Bitton Pierre-Paul, Shawkey Matthew D. How hollow melanosomes affect iridescent colour production in birds. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2013;280(1767):20131505. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dakin R, Montgomerie R. Eye for an eyespot: how iridescent plumage ocelli influence peacock mating success. Behav. Ecol. 2013;24:1048–1057. doi: 10.1093/beheco/art045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maia R, Caetano JVO, Bao SN, Macedo RH. Iridescent structural colour production in male blue-black grassquit feather barbules: the role of keratin and melanin. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2009;6:S203–S211. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2008.0460.focus. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hill, G. E. & McGraw, K. J. Bird Coloration, Volume 2: Function and Evolution. (Harvard University Press, 2006).

- 19.Van Wijk S, Bourret A, Belisle M, Garant D, Pelletier F. The influence of iridescent coloration directionality on male tree swallows’ reproductive success at different breeding densities. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2016;70:1557–1569. doi: 10.1007/s00265-016-2164-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Owens IPF, Hartley IR. Sexual dimorphism in birds: why are there so many different forms of dimorphism? P. R. Soc. B. 1998;265:397–407. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1998.0308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garratt M, Brooks RC. Oxidative stress and condition-dependent sexual signals: more than just seeing red. P. R. Soc. B. 2012;279:3121–3130. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.0568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loyau A, et al. Iridescent structurally based coloration of eyespots correlates with mating success in the peacock. Behav. Ecol. 2007;18:1123–1131. doi: 10.1093/beheco/arm088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Price TD. Phenotypic plasticity, sexual selection and the evolution of colour patterns. J. Exp. Biol. 2006;209:2368–2376. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Badyaev AV, Hill GE. Evolution of sexual dichromatism: contribution of carotenoid- versus melanin-based coloration. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2000;69:153–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2000.tb01196.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thompson CW, Hillgarth N, Leu M, McClure HE. High parasite load in house finches (Carpodacus mexicanus) is correlated with reduced expression of a sexually selected trait. Am. Nat. 1997;149:270–294. doi: 10.1086/285990. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meunier J, Pinto SF, Burri R, Roulin A. Eumelanin-based coloration and fitness parameters in birds: a meta-analysis. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2011;65:559–567. doi: 10.1007/s00265-010-1092-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roulin A. Condition-dependence, pleiotropy and the handicap principle of sexual selection in melanin-based colouration. Biol. Rev. 2016;91:328–348. doi: 10.1111/brv.12171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shawkey MD, Mills KL, Dale C, Hill GE. Microbial diversity of wild bird feathers revealed through culture-based and culture-independent techniques. Microb. Ecol. 2005;50:40–47. doi: 10.1007/s00248-004-0089-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kent CM, Burtt EH. Feather-degrading bacilli in the plumage of wild birds: Prevalence and relation to feather wear. Auk. 2016;133:583–592. doi: 10.1642/auk-16-39.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bisson IA, Marra PP, Burtt EH, Sikaroodi M, Gillevet PM. Variation in Plumage Microbiota Depends on Season and Migration. Microb. Ecol. 2009;58:212–220. doi: 10.1007/s00248-009-9490-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Javůrková Veronika Gvoždíková, Kreisinger Jakub, Procházka Petr, Požgayová Milica, Ševčíková Kateřina, Brlík Vojtěch, Adamík Peter, Heneberg Petr, Porkert Jiří. Unveiled feather microcosm: feather microbiota of passerine birds is closely associated with host species identity and bacteriocin-producing bacteria. The ISME Journal. 2019;13(9):2363–2376. doi: 10.1038/s41396-019-0438-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miskiewicz A, Kowalczyk P, Oraibi SM, Cybulska K, Misiewicz A. Bird feathers as potential sources of pathogenic microorganisms: a new look at old diseases. Anton. Leeuw. Int. J. G. 2018;111:1493–1507. doi: 10.1007/s10482-018-1048-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gunderson AR. Feather-degrading bacteria: a new frontier in avian and host-parasite research? Auk. 2008;125:972–979. doi: 10.1525/auk.2008.91008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldstein G, et al. Bacterial degradation of black and white feathers. Auk. 2004;121:656–659. doi: 10.1642/0004-8038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gunderson AR, Frame AM, Swaddle JP, Forsyth MH. Resistance of melanized feathers to bacterial degradation: is it really so black and white? J. Avian Biol. 2008;39:539–545. doi: 10.1111/j.2008.0908-8857.04413.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shawkey MD, Pillai SR, Hill GE, Siefferman LM, Roberts SR. Bacteria as an agent for change in structural plumage color: Correlational and experimental evidence. Am. Nat. 2007;169:S112–S121. doi: 10.1086/510100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shawkey MD, Pillai SR, Hill GE. Do feather-degrading bacteria affect sexually selected plumage color? Naturwissenschaften. 2009;96:123–128. doi: 10.1007/s00114-008-0462-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leclaire S, Pierret P, Chatelain M, Gasparini J. Feather bacterial load affects plumage condition, iridescent color, and investment in preening in pigeons. Behav. Ecol. 2014;25:1192–1198. doi: 10.1093/beheco/aru109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leclaire S, Czirjak GA, Hammouda A, Gasparini J. Feather bacterial load shapes the trade-off between preening and immunity in pigeons. BMC Evol. Biol. 2015;15:8. doi: 10.1186/s12862-015-0338-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saag P, et al. Plumage bacterial load is related to species, sex, biometrics and fledging success in co-occurring cavity-breeding passerines. Acta Ornithol. 2011;46:191–201. doi: 10.3161/000164511x62596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Horrocks Nicholas P. C., Matson Kevin D., Shobrak Mohammed, Tinbergen Joost M., Tieleman B. Irene. Seasonal patterns in immune indices reflect microbial loads on birds but not microbes in the wider environment. Ecosphere. 2012;3(2):art19. doi: 10.1890/ES11-00287.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burtt EH, Schroeder MR, Smith LA, Sroka JE, McGraw KJ. Colourful parrot feathers resist bacterial degradation. Biol. Lett. 2011;7:214–216. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2010.0716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ruiz-De-Castaneda R, Burtt EH, Gonzalez-Braojos S, Moreno J. Bacterial degradability of an intrafeather unmelanized ornament: a role for feather-degrading bacteria in sexual selection? Biol.J. Linn. Soc. 2012;105:409–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2011.01806.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Justyn NM, Peteya JA, D’Alba L, Shawkey MD. Preferential attachment and colonization of the keratinolytic bacterium Bacillus licheniformis on black- and white-striped feathers. Auk. 2017;134:466–473. doi: 10.1642/auk-16-245.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Galeotti P, Rubolini D, Dunn PO, Fasola M. Colour polymorphism in birds: causes and functions. J. Evol. Biol. 2003;16:635–646. doi: 10.1046/j.1420-9101.2003.00569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Delhey K. Darker where cold and wet: Australian birds follow their own version of Gloger’s rule. Ecography. 2018;41:673–683. doi: 10.1111/ecog.03040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zink, R. M. & Remsen, J. V. J. Evolutionary processes and patterns of geographic variation in birds., Vol. 4 1–69 (Plenum Press, 1986).

- 48.Burtt EH, Ichida JM. Gloger’s rule, feather-degradlng bacteria, and color variation among song sparrows. Condor. 2004;106:681–686. doi: 10.1650/7383. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maia R, Rubenstein DR, Shawkey MD. Selection, constraint, and the evolution of coloration in African starlings. Evolution. 2016;70:1064–1079. doi: 10.1111/evo.12912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eliason CM, Maia R, Shawkey MD. Modular color evolution facilitated by a complex nanostructure in birds. Evolution. 2015;69:357–367. doi: 10.1111/evo.12575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hung, H. Y. et al. Himalayan black bulbuls (Hypsipetes leucocephalus niggerimus) exhibit sexual dichromatism under ultraviolet light that is invisible to the human eye. Sci. Rep. 7, 10.1038/srep43707 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Hu, D. Y. et al. A bony-crested Jurassic dinosaur with evidence of iridescent plumage highlights complexity in early paravian evolution. Nat. Comm. 9, 10.1038/s41467-017-02515-y (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Eliason CM, Shawkey MD. Decreased hydrophobicity of iridescent feathers: a potential cost of shiny plumage. J. Exp. Biol. 2011;214:2157–2163. doi: 10.1242/jeb.055822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ruiz-Rodriguez M, Tomas G, Martin-Galvez D, Ruiz-Castellano C, Soler JJ. Bacteria and the evolution of honest signals. The case of ornamental throat feathers in spotless starlings. Funct. Ecol. 2015;29:701–709. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.12376. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Simpson RK, McGraw KJ. Two ways to display: male hummingbirds show different color-display tactics based on sun orientation. Behav. Ecol. 2018;29:637–648. doi: 10.1093/beheco/ary016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Taysom AJ, Stuart-Fox D, Cardoso GC. The contribution of structural-, psittacofulvin- and melanin-based colouration to sexual dichromatism in Australasian parrots. J. Evol. Biol. 2011;24:303–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2010.02166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Doucet SM, Montgomerie R. Structural plumage colour and parasites in satin bowerbirds Ptilonorhynchus violaceus: implications for sexual selection. J. Avian Biol. 2003;34:237–242. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-048X.2003.03113.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Doucet SM, Meadows MG. Iridescence: a functional perspective. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2009;6:S115–S132. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2008.0395.focus. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bisson IA, Marra PP, Burtt EH, Sikaroodi M, Gillevet PM. A molecular comparison of plumage and soil bacteria across biogeographic, ecological, and taxonomic scales. Microb. Ecol. 2007;54:65–81. doi: 10.1007/s00248-006-9173-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pajares, S., Bohannan, B. J. M. & Souza, V. Editorial: The Role of Microbial Communities in Tropical Ecosystems. Front. Microbiol. 7, 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01805 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Bush Sarah E., Clayton Dale H. Anti-parasite behaviour of birds. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2018;373(1751):20170196. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2017.0196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rowley, I. & Russell, E. Fairy-wrens and Grasswrens: Maluridae., (Oxford: Oxforfd University Press, 1997).

- 63.Enbody ED, et al. Social organisation and breeding biology of the White-shouldered Fairywren (Malurus alboscapulatus) Emu. 2019;119:274–285. doi: 10.1080/01584197.2019.1595663. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Enbody ED, Lantz SM, Karubian J. Production of plumage ornaments among males and females of two closely related tropical passerine bird species. Ecol. Evol. 2017;7:4024–4034. doi: 10.1002/ece3.3000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fridolfsson AK, Ellegren H. A simple and universal method for molecular sexing of non-ratite birds. Journal of Avian Biology. 1999;30:116–121. doi: 10.2307/3677252. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kahn NW, St John J, Quinn TW. Chromosome-specific intron size differences in the avian CHD gene provide an efficient method for sex identification in birds. Auk. 1998;115:1074–1078. doi: 10.2307/4089527. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McMurdie PJ, Holmes S. phyloseq:an Rpackage for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics o microbiome census data. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e61217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Muyzer G, Dewaal EC, Uitterlinden AG. Profiling of complex microbial-populations by Denaturing Gradient Gel-Electrophoresis analysis of polymerase chain reaction-amplified genes-coding for 16S ribosomal-RNA. Appl.Environ. Microbiol. 1993;59:695–700. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.3.695-700.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang Q, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM, Cole JR. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl. Environ.Microbiol. 2007;73:5261–5267. doi: 10.1128/aem.00062-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.DeSantis TZ, et al. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl. Environ.Microbiol. 2006;72:5069–5072. doi: 10.1128/aem.03006-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yu G, Lam TTY, Zhu H, Guan Y. Two methods for mapping and visualizing associated data on phylogeny using ggtree. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018;35(2):3041–3043. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Paradis E, Schliep K. ape 5.0: an environment for modern phylogenetics and evolutionary analyses in R. Bioinformatics. 2018;35:526–528. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Springer-Verlag, New York, USA (2016).

- 74.RStudio Team RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, Inc., Boston, MA URL, http://www.rstudio.com/ (2015).

- 75.Anderson MJ, Walsh DC. PERMANOVA, ANOSIM, and the Mantel test in the face of heterogeneous dispersions: what null hypothesis are you testing? Ecol. monogr. 2013;83:557–574. doi: 10.1890/12-2010.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.van Veelen, H. P. J., Salles, J. F. & Tieleman, B. I. Multi-level comparisons of cloacal, skin, feather and nest-associated microbiota suggest considerable influence of horizontal acquisition on the microbiota assembly of sympatric woodlarks and skylarks. Microbiome5, 10.1186/s40168-017-0371-6 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 77.Jacob S, et al. Chemical regulation of body feather microbiota in a wild bird. Mol. Ecol. 2018;27:1727–1738. doi: 10.1111/mec.14551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jacob J, Eigener U, Hoppe U. The structure of preen gland waxes from pelecaniform birds containing 3,7-dimethyloctan-1-ol - An active ingredient against dermatophytes. Z. Naturforsch. C. 1997;52:114–123. doi: 10.1515/znc-1997-1-220. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shawkey MD, Pillai SR, Hill GE. Chemical warfare? Effects of uropygial oil on feather-degrading bacteria. J. Avian Biol. 2003;34:345–349. doi: 10.1111/j.0908-8857.2003.03193.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Peralta-Sanchez JM, Moller AP, Martin-Platero AM, Soler JJ. Number and colour composition of nest lining feathers predict eggshell bacterial community in barn swallow nests: an experimental study. Funct. Ecol. 2010;24:426–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2009.01669.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Roulin A. Melanin pigmentation negatively correlates with plumage preening effort in barn owls. Funct. Ecol. 2007;21:264–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2006.01229.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Czirjak GA, et al. Preen gland removal increases plumage bacterial load but not that of feather-degrading bacteria. Naturwissenschaften. 2013;100:145–151. doi: 10.1007/s00114-012-1005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Giraudeau M, et al. Effects of access to preen gland secretions on mallard plumage. Naturwissenschaften. 2010;97:577–581. doi: 10.1007/s00114-010-0673-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Griggio M, Hoi H, Pilastro A. Plumage maintenance affects ultraviolet colour and female preference in the budgerigar. Behav. Proc. 2010;84:739–744. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lopez-Rull I, Pagan I, Garcia CM. Cosmetic enhancement of signal coloration: experimental evidence in the house finch. Behav. Ecol. 2010;21:781–787. doi: 10.1093/beheco/arq053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Giraudeau M, Stikeleather R, McKenna J, Hutton P, McGraw KJ. Plumage micro-organisms and preen gland size in an urbanizing context. Sci. Total Environ. 2017;580:425–429. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.09.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fulop A, Czirjak GA, Pap PL, Vagasi CI. Feather-degrading bacteria, uropygial gland size and feather quality in House Sparrows Passer domesticus. Ibis. 2016;158:362–370. doi: 10.1111/ibi.12342. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jacob Staffan, Immer Anika, Leclaire Sarah, Parthuisot Nathalie, Ducamp Christine, Espinasse Gilles, Heeb Philipp. Uropygial gland size and composition varies according to experimentally modified microbiome in Great tits. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2014;14(1):134. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-14-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Walther BA, Clayton DH. Elaborate ornaments are costly to maintain: evidence for high maintenance handicaps. Behav. Ecol. 2005;16:89–95. doi: 10.1093/beheco/arh135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Viblanc Vincent A., Mathien Adeline, Saraux Claire, Viera Vanessa M., Groscolas René. It Costs to Be Clean and Fit: Energetics of Comfort Behavior in Breeding-Fasting Penguins. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(7):e21110. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pérez-Rodríguez Lorenzo, Jovani Roger, Stevens Martin. Shape matters: animal colour patterns as signals of individual quality. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2017;284(1849):20162446. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2016.2446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Shawkey MD, et al. Beyond colour: consistent variation in near infrared and solar reflectivity in sunbirds (Nectariniidae) Sci. Nat-Heidelberg. 2017;104:5. doi: 10.1007/s00114-017-1499-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.McGraw KJ. Multiple UV reflectance peaks in the iridescent neck feathers of pigeons. Naturwissenschaften. 2004;91:125–129. doi: 10.1007/s00114-003-0498-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kinoshita S, Yoshioka S, Miyazaki J. Physics of structural colors. Reports on Progress in Physics. 2008;71(7):076401. doi: 10.1088/0034-4885/71/7/076401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Nelson KL, et al. Sunlight-mediated inactivation of health-relevant microorganisms in water: a review of mechanisms and modeling approaches. Environ. Sci.-Proc. Imp. 2018;20:1089–1122. doi: 10.1039/c8em00047f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Probst-Rud S, McNeill K, Ackermann M. Thiouridine residues in tRNAs are responsible for a synergistic effect of UVA and UVB light in photoinactivation of Escherichia coli. Environ. Microbiol. 2017;19:434–442. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zepp RG, Callaghan TV, Erickson DJ. Effects of enhanced solar ultraviolet radiation on biogeochemical cycles. J. Photoch.Photobio. B. 1998;46:69–82. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(98)00186-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Doña J, et al. Feather mites play a role in cleaning host feathers: New insights from DNA metabarcoding and microscopy. Mol. Ecol. 2019;28:203–218. doi: 10.1111/mec.14581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Doña J, Proctor H, Mironov S, Serrano D, Jovani R. Global associations between birds and vane‐dwelling feather mites. Ecology. 2016;97:3242–3242. doi: 10.1002/ecy.1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The nucleotide sequence data reported are uploaded in the GenBank database under the submission Numbers: MK215669, MK215670, MK215671, MK215672, MK215673, MK215674, MK215675, MK215676, MK215677, MK215678 and MK215679. The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.