Abstract

Background

This is an update of the original Cochrane review published in 2013 (Issue 6). Pruritus occurs in patients with disparate underlying diseases and is caused by different pathologic mechanisms. In palliative care patients, pruritus is not the most prevalent but is one of the most puzzling symptoms. It can cause considerable discomfort and affects patients' quality of life.

Objectives

To assess the effects of different pharmacological treatments for preventing or treating pruritus in adult palliative care patients.

Search methods

For this update, we searched CENTRAL (the Cochrane Library), and MEDLINE (OVID) up to 9 June 2016 and Embase (OVID) up to 7 June 2016. In addition, we searched trial registries and checked the reference lists of all relevant studies, key textbooks, reviews and websites, and we contacted investigators and specialists in pruritus and palliative care regarding unpublished data.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) assessing the effects of different pharmacological treatments, compared with a placebo, no treatment, or an alternative treatment, for preventing or treating pruritus in palliative care patients.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed the identified titles and abstracts, performed data extraction and assessed the risk of bias and methodological quality. We summarised the results descriptively and quantitatively (meta‐analyses) according to the different pharmacological interventions and the diseases associated with pruritus. We assessed the evidence using GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) and created 10 'Summary of findings' tables.

Main results

In total, we included 50 studies and 1916 participants in the review. We added 10 studies with 627 participants for this update. Altogether, we included 39 different treatments for pruritus in four different patient groups.

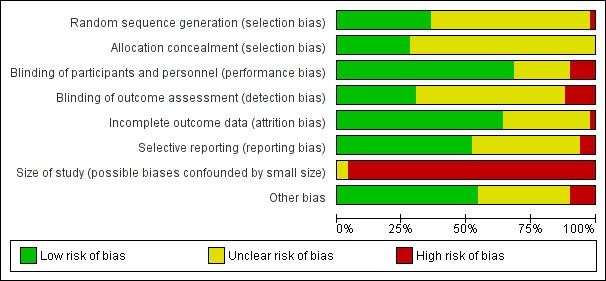

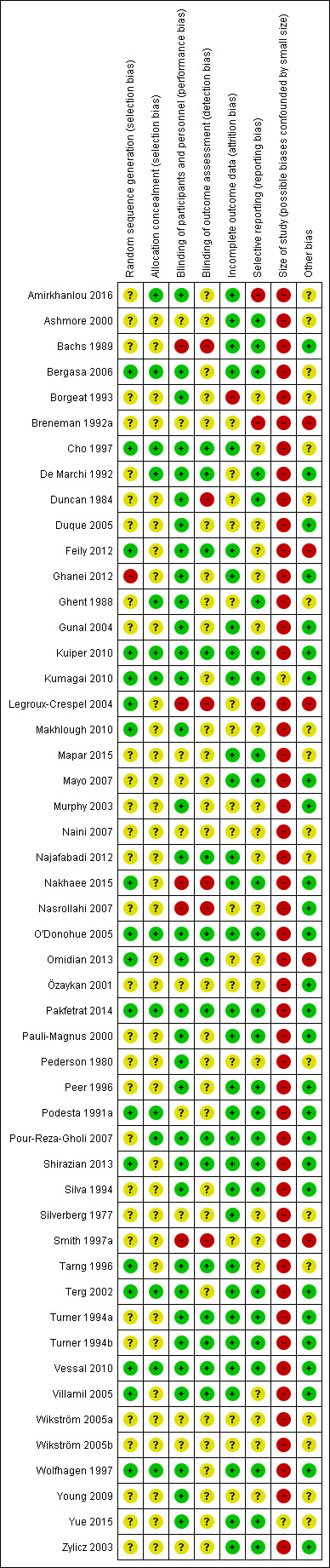

The overall risk of bias profile was heterogeneous and ranged from high to low risk. However, 48 studies (96%) had a high risk of bias due to low sample size (i.e. fewer than 50 participants per treatment arm). Using GRADE criteria, we downgraded our judgement on the quality of evidence to moderate in seven and to low in three comparisons for our primary outcome (pruritus), mainly due to imprecision and risk of bias.

In palliative care participants with pruritus of different nature, the treatment with the drug paroxetine, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, reduced pruritus by 0.78 points (numerical analogue scale from 0 to 10; 95% confidence interval (CI) −1.19 to −0.37; one RCT, N = 48, quality of evidence: moderate) compared to placebo.

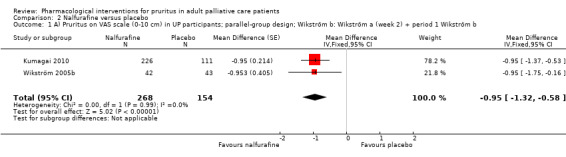

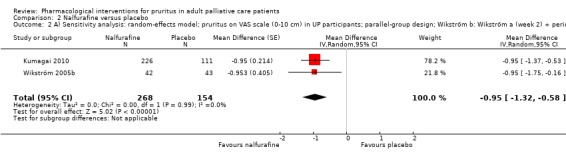

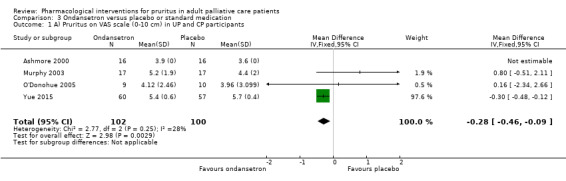

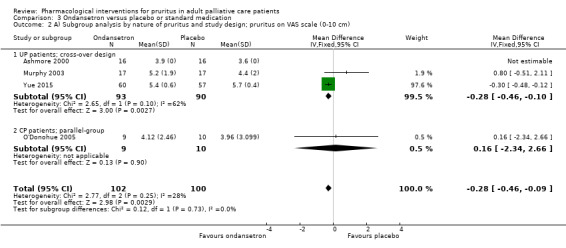

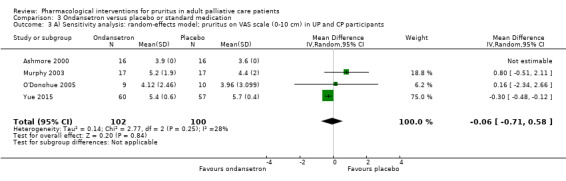

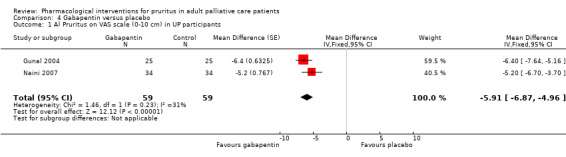

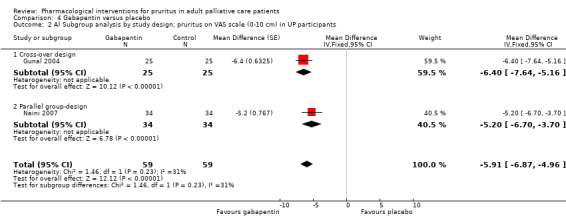

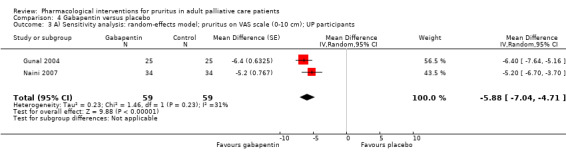

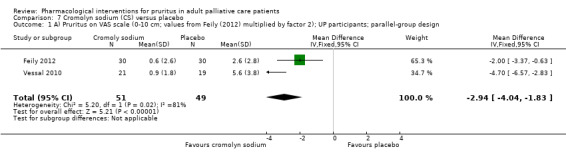

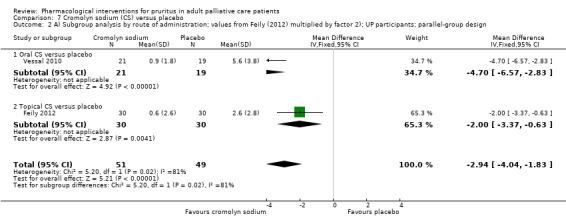

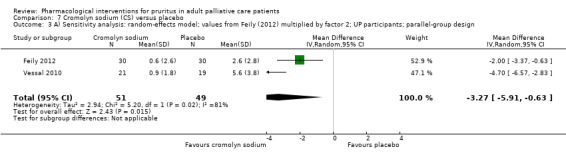

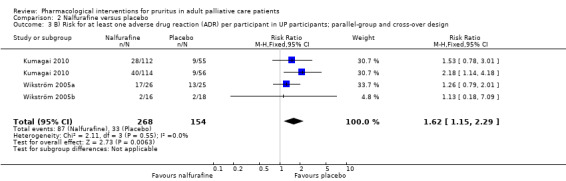

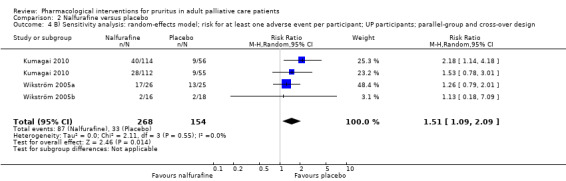

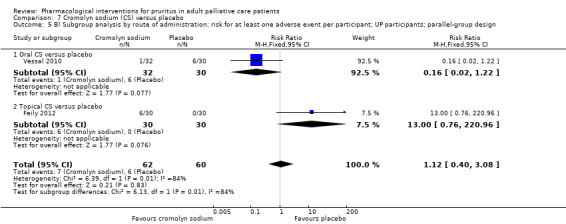

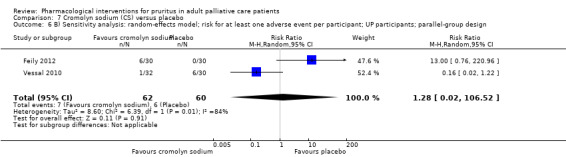

For participants suffering from uraemic pruritus (UP), gabapentin was more effective than placebo (visual analogue scale (VAS): 0 to 10), mean difference (MD) −5.91, 95% CI −6.87 to −4.96; two RCTs, N = 118, quality of evidence: moderate). The κ‐opioid receptor agonist nalfurafine showed amelioration of UP (VAS 0 to 10, MD −0.95, 95% CI −1.32 to −0.58; three RCTs, N = 422, quality of evidence: moderate) and only few adverse events. Moreover, cromolyn sodium relieved UP participants from pruritus by 2.94 points on the VAS (0 to 10) (95% CI −4.04 to −1.83; two RCTs, N = 100, quality of evidence: moderate) compared to placebo.

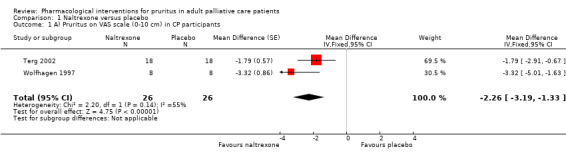

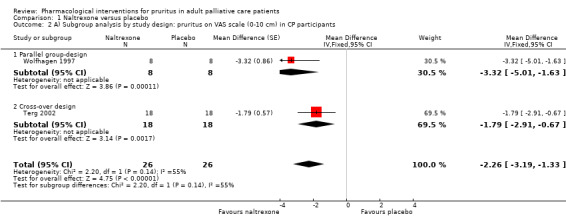

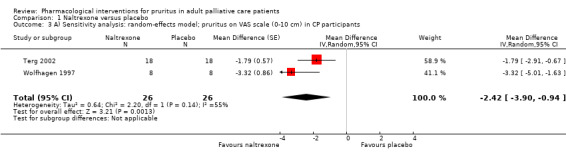

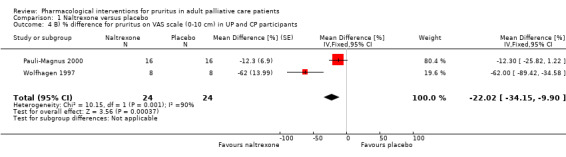

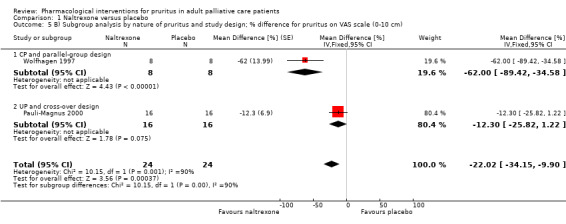

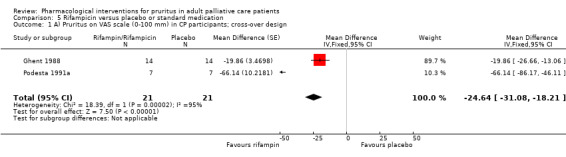

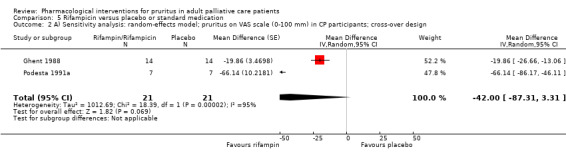

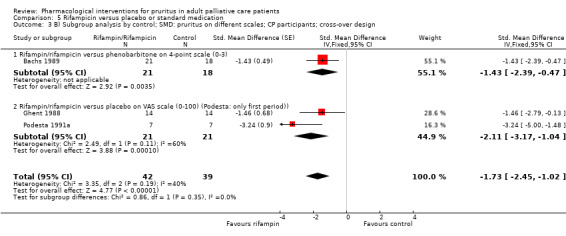

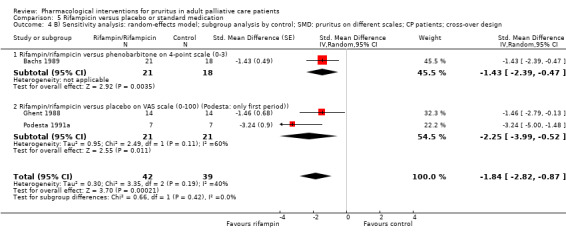

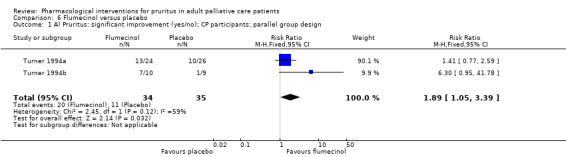

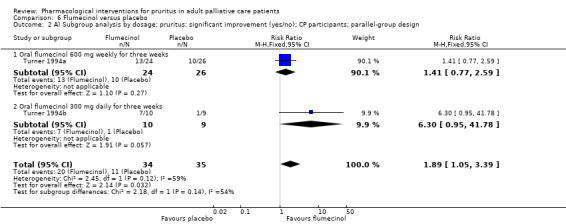

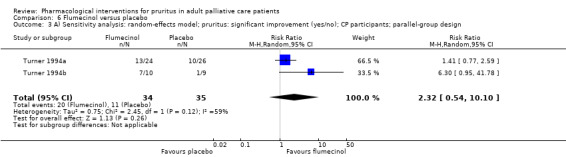

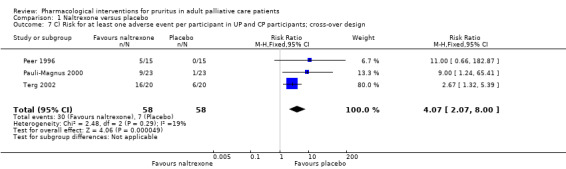

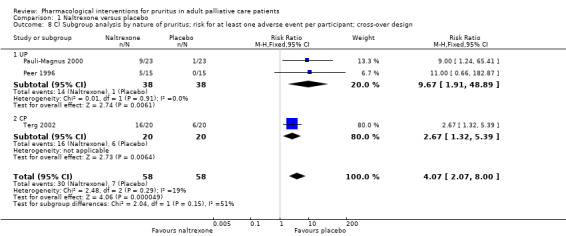

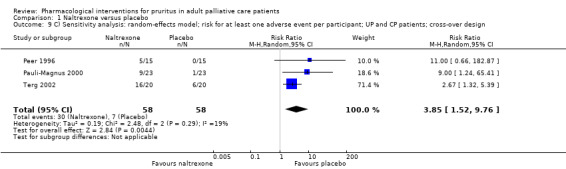

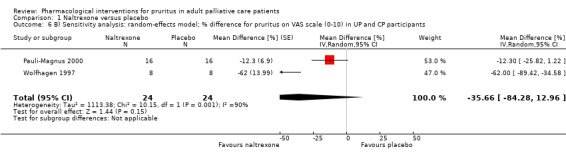

In participants with cholestatic pruritus (CP), data favoured rifampin (VAS: 0 to 100, MD −24.64, 95% CI −31.08 to −18.21; two RCTs, N = 42, quality of evidence: low) and flumecinol (RR > 1 favours treatment group; RR 1.89, 95% CI 1.05 to 3.39; two RCTs, N = 69, quality of evidence: low) and showed a low incidence of adverse events in comparison with placebo. The opioid antagonist naltrexone reduced pruritus for participants with CP (VAS: 0 to 10, MD −2.26, 95% CI −3.19 to −1.33; two RCTs, N = 52, quality of evidence: moderate) compared to placebo. However, effects in participants with UP were inconclusive (percentage difference −12.30%, 95% CI −25.82% to 1.22%, one RCT, N = 32). Furthermore, large doses of opioid antagonists (e.g. naltrexone) could be inappropriate in palliative care patients because of the risk of reducing analgesia.

For participants with HIV‐associated pruritus, it is uncertain whether drug treatment with hydroxyzine hydrochloride, pentoxifylline, triamcinolone or indomethacin reduces pruritus because the evidence was of very low quality (e.g. small sample size, lack of blinding).

Authors' conclusions

Different interventions tended to be effective for CP and UP. However, therapies for patients with malignancies are still lacking. Due to the small sample sizes in most meta‐analyses and the heterogeneous methodological quality of the included trials, the results should be interpreted cautiously in terms of generalisability.

Plain language summary

Drugs for itching in adult palliative care patients

Background

Pruritus is the medical term for itching. This symptom can be a problem in palliative care settings where treatments for cancer or severe kidney disease are given at the same time. In this updated review, we searched for high quality clinical trials of drugs for preventing or treating itch in palliative care.

Key findings and quality of evidence

In June 2016, we found 50 studies that tested 39 different drugs in 1916 people with itch. An ideal antipruritic (anti‐itch) therapy is currently lacking. However, there was enough evidence to point out some possibly useful treatments for particular causes of the itch. These included gabapentin, nalfurafine and cromolyn sodium for itch associated with chronic kidney disease, and rifampicin and flumecinol for itch associated with liver problems. Paroxetine may be useful for palliative care patients whatever the cause of the itching, although evidence was only available from one study. Overall, most of the drugs caused few and mild side effects. Naltrexone showed by far the most side effects. Overall the evidence ranged from very low to moderate quality.

Further research

Research in palliative care is challenging and often limited to a restricted period of time at the end of life. More high‐quality studies on preventing and treating itch (pruritus) are needed.

Summary of findings

Background

This is an updated version of the original Cochrane review published in 2013 (Issue 6), on "pharmacological interventions for pruritus in adult palliative care patients". Pruritus, derived from the Latin word prurire, which means 'to itch', is defined as "an unpleasant sensation associated with the desire to scratch". This definition of pruritus was introduced in 1660 by the German physician Samuel Hafenreffer (Haffenreffer 1660; Misery 2010; Proske 2010). In modern medicine, the term pruritus is generally used to refer to a pathological condition in which the sensations of itch are intense and often generalised and trigger repeated scratching in an attempt to relieve the discomfort. Pruritus is not a disease, but rather a common and still poorly understood symptom of both localised and systemic disorders that may accompany many conditions (Bernhard 2005; Summey 2009; Zylicz 2004). Pruritus is a prevalent symptom in many skin conditions. However, much less is known about pruritus that is not associated with primary skin disease. This latter problem is of major relevance to many medical specialities, and notably to palliative care. Pruritus or itch is not the most prevalent but is one of the most puzzling symptoms in advanced incurable diseases, and it can cause considerable discomfort in patients receiving treatment for cancer or other non‐malignant terminal illnesses. In addition to social embarrassment, the itch‐scratch‐itch cycle damages skin integrity, decreases resistance to infections, and impairs quality of life in a similar way to pain.

Prevalence of pruritus

Pruritus and malignant diseases

Pruritus may be associated with virtually any malignancy (Chiang 2011). Some neoplasms, particularly haematologic malignancies, are frequently associated with pruritus. Among patients with polycythaemia vera, 48% to 70% have aquagenic pruritus. About 30% of people with Hodgkin's disease also suffer from pruritus (Krajnik 2001b). The incidence and significance of pruritus in other lymphomas and leukaemia are unknown, but investigators have reported its presence in approximately 3% of patients with non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma (Lober 1988). Solid tumours can be associated with paraneoplastic pruritus, which in fact might be a presenting symptom that precedes the diagnosis by months or years. The pathophysiology is not well understood, but it appears to involve an immunologic reaction to tumour‐specific antigens (Seccareccia 2011). Pruritus is also frequent in cutaneous lymphomas (Ahern 2012). Additionally, it is a common symptom in malignancies of the biliary tract. Retrospective studies have revealed that malignant diseases are present in 2% to 11% of chronic itch cases (Weisshaar 2009).

Pruritus and non‐malignant internal diseases

Many internal diseases other than cancer may be associated with pruritus. Pruritus has been reported to herald the onset of thyroid disease, renal insufficiency, liver disease, iron deficiency, diabetes mellitus, paraproteinaemia, Sjögren's syndrome, and other conditions. In internal diseases, itch has been best studied in cholestatic pruritus (CP) and uraemic pruritus (UP) (Metz 2010; Wang 2010; Weisshaar 2009). About one third of uraemic patients treated without dialysis exhibit UP, and on maintenance haemodialysis, the incidence of uraemic itching increases to 70% to 80% (Manenti 2009; Narita 2006). CP affects 100% of patients with biliary cirrhosis and is the initial symptom in almost half of the patients with this disease (Bergasa 2008). Furthermore, the prevalence of pruritus in patients with end‐stage HIV is over 20% (Smith 1997b; Uthayakumar 1997).

Pruritus in palliative care in general

In advanced diseases, as seen in palliative care units, the prevalence of severe pruritus is not too high, but pruritus is a distressing symptom for palliative care patients and may be difficult to manage. A specific problem in palliative medicine involves systemic pruritus in terminal illnesses because pruritus is often a result of changing organ functions in this phase of illness (Twycross 2001; Twycross 2004). In this case, the itch is multifactorial, associated with both liver and kidney function deterioration and increased anxiety (Yosipovitch 2003). Additionally, in the field of palliative care, pruritus is a well‐known adverse effect of opioid administration. Even though the incidence is low (approximately 1% after systemic administration), pruritus as an adverse effect must be kept in mind (Krajnik 2001a).

Description of the condition

In the field of palliative care, pruritus is a symptom occurring in patients with disparate underlying diseases and is caused by different pathologic mechanisms. The pathogenesis of pruritus is complex and not fully elucidated, but it is known that central and peripheral nerves and specific brain regions are involved (Langner 2009). For a long time, itch was regarded as a variant of pain; however, the neural transmission associated with pruritus follows distinct neuronal pathways and causes unique sensations (Ikoma 2006; Schmelz 1997). The pathogenesis of itch is diverse and involves a complex network of cutaneous and neuronal cells. Mediators of pruritus presumably act on nerve fibres or lead to a cascade of mediator release, resulting in nerve stimulation and the sensation of pruritus. The group of potential chemical mediators is large and is steadily increasing. It contains amines (e.g. histamine, serotonin), proteases (e.g. tryptases), neuropeptides (e.g. substance P (SP), calcitonin gene‐related peptide (CGRP), bradykinin), opioids (e.g. morphine, beta‐, met‐, leu‐enkephalin), eicosanoids, growth factors and cytokines (Weisshaar 2003). The identification of different itch‐specific mediators and receptors, such as interleukin‐31, gastrin‐releasing peptide receptor or histamine H4 receptor, is increasing, and the characterisation of itch‐specific neurons is taking shape. The physiological basis of pruritus includes multiple mechanisms that are quite variable. Pruritus is initiated by the stimulation of unmyelinated C‐fibers in the dermal‐epidermal junction (Krajnik 2001a; Steinhoff 2006). Mediators of pruritus include histamine through H1 receptors and serotonin through 5‐HT2 and 5‐HT3 receptors (Jones 1999; Krajnik 2001a; Yamaguchi 1999). The actual sensation may depend on special temporal patterns of neural excitation and location of receptors (Seiz 1999). The perception of pruritus leads to a motor response to scratch, which stimulates myelinated A‐delta sensory fibres and temporarily blocks the sensation.

Description of the intervention

Due to the complex physiology of pruritus, many of the underlying mechanisms are still poorly understood (Krajnik 2001b). Modulations by serotonergic and enkephalinergic systems take place on all levels of the 'pruritus tract'. Additionally, opioid receptors seem to be of particular importance, which is not surprising considering the involvement of almost identical mediators for pain and itch (Moore 2009). This implies that various completely different pathologic mechanisms may form the basis of pruritus, making it difficult to find an effective medication for managing the symptom. Until now, no universally valid therapeutic concept has been developed. For the treatment of pruritus, researchers have tested the efficacy of several different substance classes. Among these, our review includes trials on antiphlogistic substances, psychotropic drugs, antagonistic drugs, anaesthetics, adsorbent substances and topical treatments.

How the intervention might work

For this update, we identified 50 trials studying 39 drugs from different classes. Below we have listed each drug class and individual pharmacological intervention included in this review.

Histaminergic drugs

Of the mediators that trigger pruritus, histamine is the best known and most thoroughly researched. Preformed histamine is present in large amounts in mast cell granules. For this reason, after cell activation, it can be immediately released into the surrounding area, where it may induce pruritus via H1 receptors on nerve fibres. Antihistamines act via prevention of the histamine fixation on the surface of the histamine receptors (Gaudy‐Marqueste 2010; Ständer 2008). Some of the antihistamines mentioned in this review are hydroxyzine and ketotifen.

Opioid receptor antagonists and (partial) agonists

Opioid receptor antagonists were originally developed for the treatment of heroin addiction and for symptom reversal of postanaesthetic depression, narcotic overdose, and opioid intoxication (Gowing 2010; Rösner 2010). Clinical and experimental observations have demonstrated that endogenous or exogenous opioids can evoke or intensify pruritus (Metze 1999a; Metze 1999b). This phenomenon can be explained by the activation of spinal opioid receptors, mainly μ‐opioid receptors on pain transmitting neurons, which often induce analgesia in combination with pruritus. Thus, reversing this effect through μ‐opioid antagonists inhibits pruritus (Ständer 2008).

Serotonergic drugs

Pruritus sensations may arise from the superficial layers of the skin, which contain clustered nerve endings at 'itch points' close to the dermoepidermal junction, as well as the mucous membranes and conjunctiva (Krajnik 2001a; Yosipovitch 2003). These receptors may be acted upon directly by physical or chemical stimuli, or indirectly via histamine release. Itch impulses are transmitted through the C fibres of polymodal nociceptors to the dorsal root ganglia, where a synapse occurs with secondary neurons. Efferents traverse to the contralateral spinothalamic tract and pass to the posterolateral spinothalamic tract, the posterolateral ventral thalamic nucleus, and then to the somatosensory cortex of the postcentral gyrus (Mela 2003). One important neurotransmitter in these pathways is 5‐hydroxytryptamine (5‐HT; serotonin) (O'Donohue 2005). Ondansetron is one of a group of drugs that act as antagonists at 5‐HT3 serotonin subtype receptors. Properties of drugs within this group differ with respect to the selectivity of receptor binding, potency, duration of action and dose‐response relationships.

Serotonin reuptake inhibitors and antidepressants

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) like sertraline and paroxetine play an increasingly important role in the management of pruritus (Balaskas 1998; Larijani 1996; Raap 2012; Schworer 1995; Tandon 2007; Tennyson 2001; Wilde 1996; Ye 2001; Zylicz 1998). Experts believe that they raise the extracellular level of the neurotransmitter serotonin by inhibiting its reuptake into the presynaptic cell and increasing the level of serotonin in the synaptic cleft that is available to bind to the postsynaptic receptor. They have varying degrees of selectivity for the other monoamine transporters, with pure SSRIs having only weak affinity for the noradrenaline and dopamine transporters.

Antiepileptics

Antiepileptics are used to prevent or reduce the severity and frequency of seizures (Duley 2010; Ratilal 2005; Wiffen 2011). Gabapentin and pregabalin, which are γ‐aminobutyric acid analogues, were originally developed as antiepileptics and may hinder the transmission of nociceptive sensations to the brain, thereby also suppressing pruritus (Ständer 2008).

Rifampicin

Rifampicin, or rifampin in the USA, is an antibiotic that induces detoxicating hepatic enzymes and competitively inhibits the reuptake of bile acids by hepatocytic transporters (Trauner 2005). Some hypothesise that rifampicin might influence pruritus by changing the bacterial growth in the intestines, which can influence the reabsorption of pruritrogens.

Thalidomide

Thalidomide is a drug that modifies or regulates the immune system and has anti‐inflammatory properties. It is used as an immunomodulator to treat graft versus host reactions. It suppresses tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF‐α) production and leads to a predominant differentiation of Th2 lymphocytes with suppression of interleukin‐2 (IL‐2) producing Th1 cells (McHugh 1995; Mettang 2010). The antipruritic action of this drug may be secondary to inhibition of TNF‐α. Another possibility is that thalidomide can act as both a peripheral and a central nerve depressant (Moretti 2010).

Flumecinol

There are reports that flumecinol (3‐trifluoromethyl‐alpha‐ethylbenzhydrol), a benzhydrol derivative, induces microsomal drug metabolising enzymes (Turner 1990). Flumecinol also lowers serum bilirubin in Gilbert's syndrome, possibly by inducing bilirubin undine diphosphate (UDP)‐glucuronyltransferase. Therefore, it may induce a range of enzymes, similar to phenobarbitone and rifampicin.

Colestyramine

Colestyramine is an intestinally active anion exchange resin. It interrupts the enterohepatic circulation of bile acids and has been used for many years to relieve pruritus in cholestatic disorders (Datta 1966; Sharp 1967). Another bile acid sequestrant also used for the treatment of pruritus is colesevelam.

Cromolyn sodium

Cromolyn sodium is a drug that blocks mast cell degranulation in response to antigens, leading to decreased release of histamine, leukotrienes and other inflammatory mast cell products. It is hypothesised that mediators released from mast cells are most likely to be responsible for UP. Another hypothesis is that cromolyn sodium may decrease the severity of pruritus via reducing serum tryptase levels. Both oral and topical administration is possible.

Leukotriene antagonists

Leukotriene antagonists prevent the inflammatory response produced by leukotrienes (Watts 2012).

Erythropoietin

Erythropoietin is a hormone produced naturally by the kidneys that stimulates the production of red blood cells in the bone marrow. Studies have hypothesised that erythropoietin may have an antipruritic effect related to a lowering effect of the hormone on plasma histamine concentrations (Bohlius 2009).

Activated charcoal

Activated charcoal is an agent that can bind many poisons in the stomach and therefore prevent them from being absorbed. Charcoal has also been shown to be effective in UP (Giovanetti 1995; Yatzidis 1972).

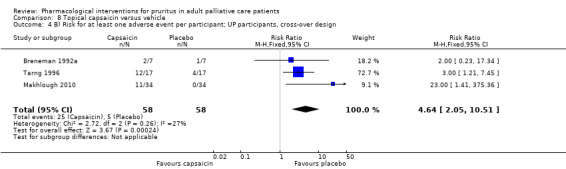

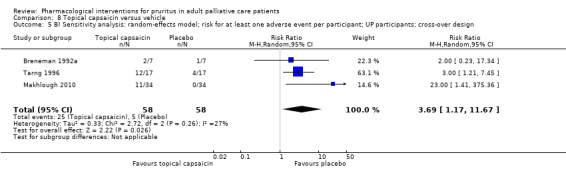

Topical capsaicin

Capsaicin is the prototype of topical antipruritic agents that target the transient receptor potential (TRP) gene family of ion channels, which respond to physical activation (heat, cold), protons (pH changes) or biological mediators (for example prostanoids) and counteract itch via activating pain neurons (Derry 2012; Derry 2013; Steinhoff 2011). Capsaicin (trans‐8‐methyl‐N‐vanillyl‐6‐nonenamide) is an alkaloid naturally found in many botanical species of the nightshade plant family (Solanacea).

Tacrolimus

Tacrolimus is an immunosuppressant used for the prevention of transplant rejection. It suppresses the differentiation of Th1 lymphocytes and the ensuing IL‐2 production (Suthanthiran 1994; Webster 2005).

Pramoxine hydrochloride

Pramoxine hydrochloride is a local anaesthetic. Pramoxine stabilises the neuronal membrane by an uncertain mechanism (Elmariah 2011; Hedayati 2005).

Ergocalciferol

Patients under haemodialysis often experience pruritus and may have an impaired metabolism of vitamin D. It is supposed that the administration of ergocalciferol (vitamin D2) may have an antipruritic effect (Shirazian 2013).

Nicotinamide

Nicotinamide (which is the amid of nicotinic acid, i.e. vitamin B3/niacin) may have an antipruritic effect, mediated by its anti‐inflammatory and histamine‐release blocking characteristics (Omidian 2013).

Omega‐3 fatty acids

Fish oil tends to support the immune system and reduces inflammation, free radicals and leukotriene B‐4. Hence, omega‐3 fatty acids may be effective in UP (Ghanei 2012).

Turmeric

Turmeric is the powder of Curcuma longa L. (Zingiberaceae) containing the active component curcumin (diferuloylmethane), which has an anti‐inflammatory effect and may be beneficial for UP (Pakfetrat 2014).

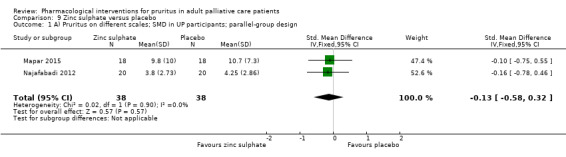

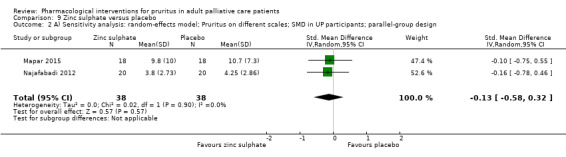

Zinc sulphate

Pruritus patients with UP may benefit from zinc sulphate, as it is an antagonist of calcium (releases histamine) and prevents degranulation of mast cells (Mapar 2015; Najafabadi 2012).

Other treatments

Photodynamic therapy, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), and other non‐pharmaceutical therapies for pruritus may be assessed in a separate systematic review.

Summary of interventions

In conclusion, pruritus is a frequent and distressing symptom. The medical literature is full of recommendations for its management, but it contains only a few clinical trials and evidence‐based data. There are some reviews about pruritus in general (Winkelmann 1964; Winkelmann 1982), dermatologic causes of pruritus (Fransway 1988), pruritus in systemic diseases (Kantor 1983; Summey 2005), and pruritus related to specific causes like cholestasis or uraemia (Khandelwal 1994; Szepietowski 2004). There is also some literature on the management of pruritus in palliative care patients (Krajnik 2001b). There have also been two recent systematic reviews that assessed the effectiveness of different medical interventions on pruritus in the field of palliative care (Siemens 2014; Xander 2013). This is an updated version of the original Cochrane review by Xander and colleagues.

Why it is important to do this review

Pruritus or itch is one of the most puzzling symptoms in advanced incurable diseases and can cause considerable discomfort in patients. Nevertheless, it is a kind of Cinderella symptom, tucked away and hidden behind more 'fashionable' symptoms such as pain. As already explained, pruritus is multifactorial in origin and can be a symptom of diverse pathophysiologies. Particularly over the last decade, clinical observation and controlled trials have done much to aid the understanding and treatment of pruritus, especially in liver disease, uraemia and other kinds of chronic pruritus. Therefore, this review aimed to systematically collect and evaluate the evidence for adequate treatment of pruritus in the field of palliative care, to put this symptom into perspective, and to make new therapeutic strategies accessible for clinicians and patients (Wee 2008).

Objectives

To assess the effects of different pharmacological treatments for preventing or treating pruritus in adult palliative care patients.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered full reports concerning pruritus in patients with advanced diseases with a focus on pharmacological treatment. The primary outcome of the studies had to be subjective measures of pruritus. We only included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in adults. We defined 'randomised' as studies described as such by the authors anywhere in the manuscripts. Both published and unpublished studies were eligible for inclusion.

Contrary to our initial considerations in the protocol, we did not include controlled clinical trials (CCTs) (Differences between protocol and review).

Types of participants

Previous reviews have cited problems defining the population for systematic reviews in palliative care. Therefore, we drew upon the definition that other Cochrane reviews have used, "adult patients in any setting, receiving palliative care or suffering an incurable progressive medical condition" (Dorman 2010; Perkins 2009). Studies eligible for this review included participants:

suffering from pruritus combined with an incurable advanced malignant or non‐malignant disease such as advanced cancer, HIV/AIDS, renal failure, liver failure or others;

aged 18 years or older; and

of both sexes.

Since many of the studies we considered also included participants who were not necessarily in advanced stages of their disease and were not palliative care patients, we decided to define comprehensible criteria for the patients included in this systematic review. Concretely, we included all patients who were described as palliative care patients or as patients in advanced stages of malignant or non‐malignant diseases.

If no detailed information on the stages of the underlying disease was available, we considered the following patients to have palliative care needs.

UP (also known as chronic kidney disease (CKD)‐associated pruritus, renal pruritus or end‐stage renal disease (ESRD) pruritus) in need of haemodialysis.

CP or hepatogenic pruritus: all patients suffering from primary biliary cholestasis or primary sclerosing cholestasis and all patients who were described as being in an advanced stage of the disease. If patients with different kinds of CP were included in the studies, only studies that included more than 75% of patients with primary biliary cholestasis, primary sclerosing cholangitis or advanced‐stage disease were eligible for the systematic review.

HIV‐associated pruritus: all patients with pruritus associated with HIV.

Pruritus associated with malignancies: all patients in advanced stages of cancer (with metastases or described as in an advanced stage of the disease).

We excluded studies in people with pruritus related to acute or chronic cholestasis, acute or chronic dermatological diseases, or acute medical or surgical interventions. Furthermore, we did not include participants with primarily dermatological diseases or infections.

Types of interventions

We included studies using any pharmacological medication to treat pruritus, regardless of dosage, route of administration or duration of follow‐up. Interventions with both internal and external application of the treatment were eligible for inclusion in the review. We did not focus on pharmacological interventions targeting the treatment of underlying diseases but rather on pharmacological interventions for treating pruritus as an accompanying symptom of advanced diseases. We excluded complementary medical interventions and non‐pharmaceutical treatments such as photodynamic therapy or TENS, but a separate review may evaluate them.

Types of outcome measures

Given the heterogeneity of included trials, in the Effects of interventions we organise the reporting of primary and secondary outcomes according to types of participants and pharmacological interventions.

Primary outcomes

Primary outcomes were subjective measurements of pruritus.

Scores on validated and reliable scales, such as unidimensional scales (e.g. visual analogue scales (VAS), numeric rating scales (NRS), categorical scales).

Patient‐reported pruritus according to non‐validated pruritus scores (e.g. 1 to 3 or 1 to 4), which were substituted by estimations by nursing or medical staff if self‐assessment was not possible.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes included:

quality of life;

patient satisfaction;

depression;

adverse events.

Search methods for identification of studies

There were no language restrictions for either the searching strategies or study inclusion.

Electronic searches

For this update, we searched the following databases using slightly revised search strategies (see Appendix 1; Appendix 2; Appendix 3) after consultation with the Cochrane Pain, Palliative Care and Supportive Care Cochrane Review Group.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2016, Issue 5) in the Cochrane Library (searched 2012 to 9 June 2016)

MEDLINE Ovid (2012 to 9 June 2016);

Embase Ovid (2012 to 7 June 2016).

We used the Cochrane highly sensitive search strategy (CHSSS) for identifying RCTs in MEDLINE, a sensitivity maximising version as referenced in Chapter 6.4.11.1 and detailed in box 6.4.c of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 (Higgins 2011). We used a similar study design filter for other databases, as appropriate.

We decided not to search the other databases used for the original review as they did not yield any useful records.

In the original review, we searched the following databases (see Appendix 4, Appendix 5, Appendix 6, Appendix 7, Appendix 8 and Appendix 9).

Cochrane Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care Trials Register (searched August 2012).

The Cochrane Library via Wiley, including the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) (searched August 2012);

MEDLINE Ovid (including MEDLINE In‐process and other non‐indexed citations) (1950 to August 2012);

Embase Ovid, including Embase Alert (1980 to August 2012);

BIOSIS previews Ovid and Web of Knowledge (1969 to August 2012);

CINAHL EBSCO (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; 1982 to August 2012);

PsycINFO EBSCO (1806 to August 2012).

In addition, we performed Internet searches using Scirus (www.scirus.com) and Google Scholar (scholar.google.de) in the original review.

Searching other resources

We searched the following trial registers.

Current Controlled Trials (www.controlled‐trials.com; searched 9 June 2016).

WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (apps.who.int/trialsearch; searched 9 June 2016).

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov; searched 9 June 2016).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

For this update, two review authors (WS, CX) screened all titles and abstracts of studies identified by the search strategies for relevance. We resolved disagreement by consensus and after discussion with a third review author (GB). If it was not possible to accept or reject a study with certainty, we obtained the full text of the study for further evaluation. Two review authors (WS, CX) independently assessed the full text of all potentially relevant studies in accordance with the above inclusion criteria. We resolved any differences in opinion at this stage by consensus and discussion with a third review author (GB). We kept a record of all excluded studies and the reasons for exclusion.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (WS, CX) independently extracted data from the selected studies using a standardised coding form. We discussed differences in data extraction and sought the input of a third review author (GB) as necessary. The data extraction form, specifically designed for the review, included the following.

Study ID and publication details

Study aim

Study design (randomised, not randomised, controlled, prospective etc.)

Primary and secondary outcomes

Type of control group

Number of participants in each group

Quality of the study

Randomisation procedure

Concealment of treatment allocation

Details of blinding

Per protocol analysis or intention‐to‐treat analysis

Number of withdrawals described

Management of missing data

Follow‐up data

Details of analysis

Patient characteristics

Demographics

Diagnosis

Status or course of disease

Type and stage of treatment

Type of pruritus

Pharmacological interventions

Drug characteristics

Duration of therapy

Pharmacological regimen of drug treatment with the drug of interest (dose, frequency of application)

Description of placebo

Description of alternative treatment

Description of additional non‐pharmacological techniques if additionally used during similar regimens

Outcome measures

Primary outcome, including the measurement of pruritus (mean, standard deviation (SD)) and the change in level of pruritus

Secondary outcomes, including the measurement of quality of life, patient satisfaction, depression and adverse events of treatments

Additional information

Patient narrative comments, etc.

We contacted authors of studies to, if possible, provide unpublished data if required for analysis.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We performed the 'Risk of bias' assessment for RCTs as recommended by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011; RevMan 2014). Two review authors (WS, CX) independently assessed the quality of included studies using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2011; RevMan 2014).

Random sequence generation

Low risk: every participant had an equal chance to be selected for either treatment, and the investigator was unable to predict which treatment the participant would be assigned to.

Unclear risk: no information given.

High risk: for example, randomisation by date of birth or date of admission.

Allocation concealment

Low risk: methods to conceal allocation included central randomisation, serially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes, or other descriptions with convincing concealment.

Unclear risk: authors did not adequately report the method of concealment.

High risk: investigators enrolling participants could possibly foresee assignments because of the use of high risk methods to conceal allocation, such as an open random allocation schedule (e.g. a list of random numbers), assignment envelopes without appropriate safeguards (e.g. if envelopes were unsealed, nonopaque, or not sequentially numbered), alternation or rotation, date of birth.

Blinding of participants and personnel

Low risk: blinding of participants and providers stated and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken.

Unclear risk: blinding not adequate, but the outcome measurement is not likely to have been influenced by lack of blinding.

High risk: no blinding or incomplete blinding, and the outcome or outcome measurement is likely to have been influenced by lack of blinding.

Blinding of outcome assessors

Low risk: blinding of providers and outcome assessor stated and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken.

Unclear risk: blinding of outcome assessment not adequate, but the outcome measurement is not likely to have been influenced by lack of blinding.

High risk: no blinding or incomplete blinding of outcome assessment, and the outcome or outcome measurement is likely to have been influenced by lack of blinding.

Incomplete outcome data

Low risk: no missing outcome data, or reasons for missing outcome data are unlikely to be related to true outcome.

Unclear risk: insufficient information to permit judgement.

High risk: reasons for missing outcome data likely to be related to true outcome, with either imbalance in numbers or reasons for missing data across intervention groups, or 'as‐treated' analysis done with substantial departure of the intervention received from that assigned at randomisation.

Selective outcome reporting

Low risk: reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting.

Unclear risk: insufficient information to permit judgement.

High risk: reports of the study suggest selective outcome reporting.

Size of study

Low risk: 200 participants or more per treatment arm.

Unclear risk: 50 to 199 participants per treatment arm.

High risk: fewer than 50 participants per treatment arm.

Other sources of bias

Low risk of bias: the trial appears to be free of other components that could put it at risk of bias.

Unclear risk of bias: the trial may or may not be free of other components that could put it at risk of bias.

High risk of bias: there are other factors in the trial that could put it at risk of bias, e.g. for‐profit involvement, authors have conducted trials on the same topic, etc.

The review authors were blinded to each others' assessments. We resolved any disagreements by discussion. We did not automatically exclude any study as a result of a rating of 'unclear' or 'high' risk or based on a low quality score. We considered trials assessed as being at low risk of bias in all of the specified individual domains to be trials with overall low risk of bias. We considered studies at unclear risk of bias in one or more of the specified individual domains to be trials with unclear risk of bias. Finally, we considered studies assessed at high risk of bias in one or more of the specified individual domains to be trials with high risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

Primary outcome: measurement of itch

Pruritus measurement is problematic because of its subjective nature and poor localisation. In addition, itch has multidimensional aspects (for example severity, duration, frequency, spatial distribution, and quality). Although several authors have suggested that VAS is subjective and represents an inadequate and unreliable method of assessing pruritus (Jones 1999), more sophisticated and objective methods pose several practical difficulties since the main goal of pruritus treatment is to improve patients' well‐being and quality of life. It is only possible to measure these aspects subjectively, as pruritus is primarily based on the subjective perception of the patient. Therefore, for the direct evaluation of itch, we have to rely on the patients' own ratings of their subjective symptoms and on the assumption that the participant is able to relate their experiences accurately.

Studies commonly employ categorical research scales that consist of discrete divisions of the frequency or intensity of pruritus (e.g. none, mild, moderate severe). Moreover, the Duo scale is used by some researches (Duo 1987; Mettang 2002), which is a sum score covering areas like pruritus severity, distribution, frequency and sleep disturbance. The instrument is used in different ways resulting in ranges from 0‐36 to 0‐48.

Continuous scales like the VAS or numeric rating scales (NRS) consist of a line with a specific length (e.g. 100 mm or 10 cm) with descriptive anchors at the extremes, for example 'no pruritus' and 'pruritus as bad as it can be imagined'. Since the VAS is validated (Reich 2008), simple, accurate, and supposedly the most sensitive approach to measuring pruritus intensity, it is probably the most commonly used scale in pruritus research (Wallengren 2010; Weisshaar 2003).

Another approach to measurement of pruritus is scratching behaviour measurement. In contrast to patient‐reported measures of pruritus, it is possible to objectively quantify scratching activity by report of scratching behaviour, for example with hand‐activated counters to record scratching (Melin 1986). This method is not suitable for recording nocturnal scratching, but other methods are, for example nocturnal bed movement measured by a vibration transducer on one of the legs of the bed, and limb or forearm activity measured by movement‐sensitive meters. Researchers can also observe nocturnal scratching by infrared videotaping or by direct observation during the night.

One instrument for recording daily and nocturnal scratching is the pruritometer, which processes the signals of a piezoelectric vibration sensor fixed on the middle finger of the patient's dominant hand and sent to a counter worn by the patient like a wristwatch (Wallengren 2010).

Scores and measurement of scratching may also be determined through questionnaires asking for more information regarding the pruritus, for example the 'Worcester Itch Index' or the 'Eppendorf Itch Questionnaire' (Weisshaar 2003).

In this systematic review, investigators evaluated treatment effect by estimations of nursing or medical staff if self‐assessment was not possible.

Since no gold standard concerning treatment or improvement of pruritus exists, we considered a reduction of pruritus symptoms by 30% as moderate and a reduction by 50% as substantial, assuming that there were no other specifications given in the studies. This is consistent with the IMMPACT recommendations introduced in Turk 2008.

Secondary outcomes

Quality of life, patient satisfaction, depression, and adverse events were recorded as secondary outcomes.

For measuring quality of life, we considered the following scales or methods.

Short Form 36 (8 dimensions that can be transformed on a 0‐100 scale, higher values = better status) and Liver Disease Symptom Index 2.0 (18 items, 0‐4, higher score = worse status) (Kuiper 2010).

VAS (0 to 100 mm), 0 = able to cope with normal activities, 100 = completely incapacitated (Turner 1994a; Turner 1994b).

Other investigators assessed patient satisfaction using a seven‐point scale, where 0 meant indifferent, a value of −3 meant extremely poor, and a value +3 meant excellent (Zylicz 2003).

We considered depression using:

the Hamilton depression rating scale (includes items intrinsic to medical conditions (i.e. fatigue, sleep) and concern about health) (Bergasa 2006);

the Structured Clinical Interview Questionnaire (SCID) for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM‐IV), Axis I Disorders (a measure for the diagnosis of depression and anxiety syndromes) (Bergasa 2006); and

the 30‐item Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology‐Self‐Report (IDS‐SR30) (Mayo 2007).

Most included studies reported adverse events.

Unit of analysis issues

We evaluated the data of the RCTs. Identified studies had to evaluate and report the effect of a pharmacological treatment versus placebo, no treatment, or an alternative treatment on pruritus in individuals. Our results did not contain studies with multiple observations or cluster RCTs. However, there were cross‐over studies, and we considered specific challenges, such as possible carryover effects.

Cross‐over trials may be combined with parallel‐group trials in principle (Higgins 2011, chapter 16.4). We included properly reported cross‐over trials (i.e. analysed with paired t‐test and without a carryover or period effect) in meta‐analyses using the generic inverse variance (GIV) method Higgins 2011. When authors reported or analysed results in an inappropriate way that did not allow calculation of the standard error (SE) of the mean difference in a paired analysis, we tried to approximate the SE by estimating the correlation within participants. In case there were insufficient data to calculate the correlation coefficient, we assumed a correlation of zero, which results in a conservative scenario, i.e. SE is slightly overestimated (Gunal 2004; Murphy 2003). Each comparison includes a subgroup analysis by study design when both cross‐over and parallel‐group trials were included in a meta‐analysis.

In addition, the meta‐analyses and 'Summary of findings' tables show the number of patients for parallel‐group trials and the number of cases for cross‐over trials, since there are two post‐treatment values for each patient in a cross‐over trial. However, the number of participants included in this review and also shown in the tables refers to participants and not to cases of the cross‐over RCTs.

Dealing with missing data

We did not impute missing outcome data. We analysed them on an endpoint basis, including only participants for whom final data were available. We did not assume that participants who dropped out after randomisation had a negative outcome.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We investigated heterogeneity using visual inspection of the forest plots as well as the I2 statistic (Higgins 2002).

Assessment of reporting biases

There were insufficient studies in each of the meta‐analyses to assess reporting bias. We had planned funnel plots corresponding to meta‐analyses of the primary outcome to assess the potential for small study effects, such as publication bias.

Data synthesis

We used Review Manager 5 (RevMan) and R statistical software for data entry, statistical analysis, and creation of graphs (R Foundation 2015; RevMan 2014; Schwarzer 2015). We analysed each drug class separately and compared it with its respective control group or alternative intervention. We presented most outcomes in this review as continuous variables. We presented continuous outcomes, including the mean change in pruritus score between treatment and placebo, either as mean difference (MD) or standardised mean difference (SMD; 0.2 = small effect, 0.5 = moderate effect, 0.8 = large effect, Cohen 1988) with 95% confidence intervals (CI), depending on whether trials reported results on the same or different scales. We anticipated that some individual studies would have used final scores and others would use change scores and even analysis of covariance in their statistical analyses of the results. In this case, we combined these different types of analysis as MDs. We used the fixed‐effect model in all meta‐analyses.

We decided not to pool the results in cases of significant clinical heterogeneity. We calculated the 95% CI for each effect size estimate.

We made the following treatment comparisons.

Naltrexone versus placebo.

Nalfurafine versus placebo.

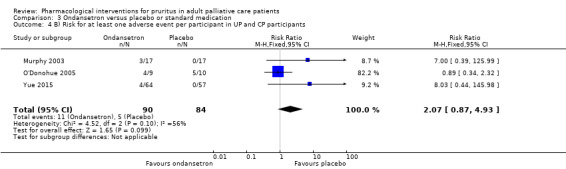

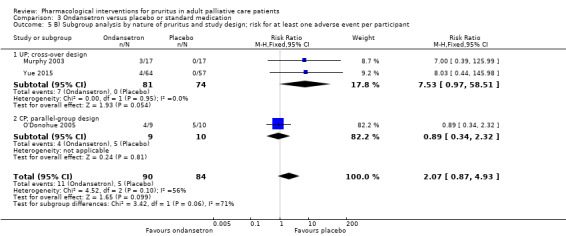

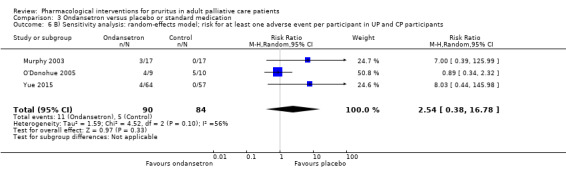

Ondansetron versus placebo.

Gabapentin versus placebo.

Rifampicin versus placebo.

Flumecinol versus placebo.

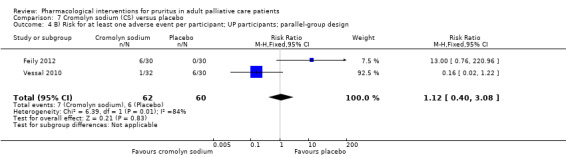

Cromolyn sodium versus placebo.

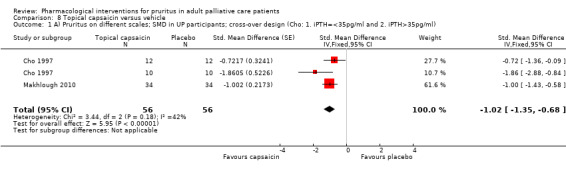

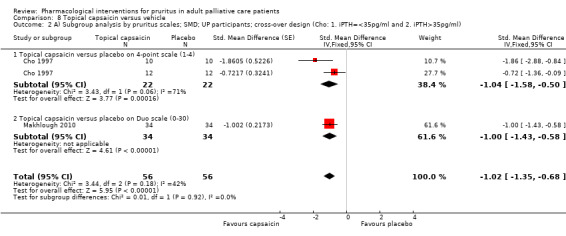

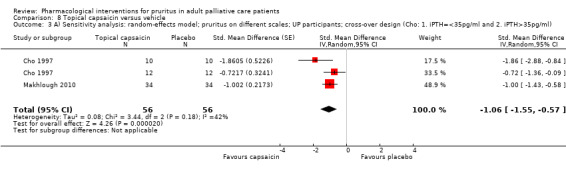

Capsaicin versus placebo.

Zinc sulphate versus placebo.

We included studies with parallel‐group and cross‐over designs in the review, handling data from cross‐over trials according to the recommendations in section 16.4 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). If all necessary data were provided in the publications of cross‐over trials and if no carryover effect or periodic effect was apparent, we included the results of a paired analysis in the meta‐analyses. If the required data were available, we included only data from the first period of the cross‐over trial (if available) and thus treated this trial as a parallel‐group trial.

Summary of findings table

We prepared 'Summary of findings' tables with GRADEpro GDT software and in accordance with the latest recommendations of the GRADE working group (GRADEproGDT 2015; Guyatt 2013a; Guyatt 2013b). The 'Summary of findings' tables include each comparison and the primary outcome (pruritus) as well as all secondary outcomes. We included the number of participants who experienced at least one adverse event as a binary outcome in our meta‐analyses and 'Summary of findings' tables.

We assessed the overall quality of the evidence for each outcome using the GRADE system and presented it along with the main findings of the review in 'Summary of findings' tables, following a transparent and simple format (GRADE Handbook; GRADEproGDT 2015). In particular, we included key information concerning the quality of evidence, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of available data on the main outcomes.

The GRADE system uses the following criteria for assigning grade of evidence.

High: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect.

Moderate: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate.

Low: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate.

Very low: any estimate of effect is very uncertain.

We downgraded the quality of evidence under the following conditions.

Serious (−1) or very serious (−2) limitation to study design or execution (risk of bias).

Serious (−1) or very serious (−2) inconsistency of results.

Serious (−1) or very serious (−2) indirectness of evidence.

Serious (−1) or very serious (−2) imprecision.

Serious (−1) or very serious (−2) publication bias.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned the following subgroup analyses a priori and performed them when possible.

UP versus CP.

Parallel‐group versus cross‐over study design.

We conducted subgroup analyses as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions section 9.6 (Higgins 2011).

Sensitivity analysis

We performed sensitivity analyses to assess whether the quality of the chosen trials influenced the results of the meta‐analysis or whether the analysis by the fixed‐effect or the random‐effects model changed the results.

Due to the small numbers of studies for a single comparison, we did not conduct sensitivity analyses based on quality criteria.

Results

Description of studies

Please see the Characteristics of included studies table for full information on the included studies.

Results of the search

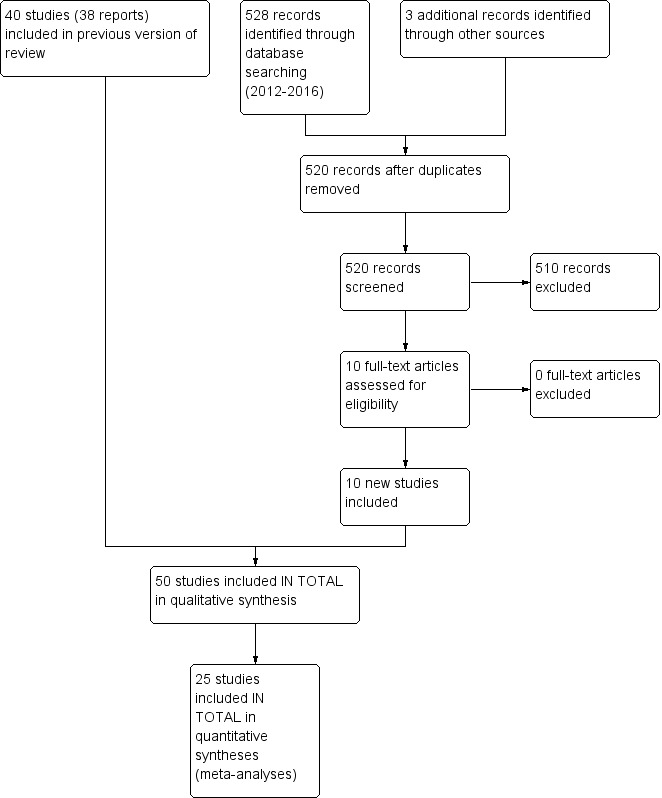

In total, we identified 50 studies with 1916 participants for this update. See Figure 1 for a flowchart of the study selection process. We included 10 new studies with 627 additional participants: Amirkhanlou 2016 (N = 52), Feily 2012 (N = 60), Ghanei 2012 (N = 22), Mapar 2015 (N = 40), Najafabadi 2012 (N = 40), Nakhaee 2015 (N = 25), Omidian 2013 (N = 50), Pakfetrat 2014 (N = 100), Shirazian 2013 (N = 50)and Yue 2015 (N = 188). We updated the study flow diagram (Figure 1) according to the latest recommendations (Stovold 2014). The 50 identified studies contained different assessment scales (Table 11) and a total of 39 different drugs for the treatment of pruritus associated with different underlying diseases (Table 12). The drugs assessed were antiphlogistic substances, psychotropic drugs, antagonistic drugs, anaesthetics, adsorbent substances and topical treatments. The participants suffered from UP (1574 participants, 82%), CP caused by hepatobiliary diseases (276 participants, 14%), pruritus associated with malignancies (26 participants, 1%) (Zylicz 2003), and pruritus as a symptom associated with HIV (40 participants, 2%) (Smith 1997a). Among the included studies, 20 were cross‐over studies, while the remaining 30 studies had a parallel‐group design. Two studies were already pooled in a meta‐analysis (Wikström 2005a; Wikström 2005b). The studies took place in 25 different countries in Europe, North America and Asia. Fourteen studies were multicentre trials. A few studies assessed quality of life (Kuiper 2010; Turner 1994a; Turner 1994b; Yue 2015), depression (Zylicz 2003), and patient satisfaction (Bergasa 2006; Mayo 2007), and most of them reported adverse events (see Table 13; Table 14; Table 15).

1.

Study flow diagram.

1. Measurement of pruritus.

| Study | Pruritus scale | Determination of Score | Description of scale | Description of partial resolution | |

| Amirkhanlou 2016 | Clinical response | Number and percentage post treatment | 1 | Complete response (no itching or minimal itching after treatment) | See description of scale |

| 2 | Partial response (mild or moderate severity of itching after treatment) | ||||

| 3 | No response (severe pruritus after treatment) | ||||

| Ashmore 2000 | 0‐10 cm VAS | Median daily pruritus score and interquartile range for each period | 0 | No pruritus | Score reduction of 40% to 50% was chosen as desired improvement |

| 10 | Maximum pruritus | ||||

| Bachs 1989 | 0‐3 score | Mean and standard deviation for pruritus 7 days before, and daily during treatment | 0 | No itching | Not available |

| 1 | Mild intermittent pruritus which did not affect the patient's routine or disturb sleep pattern | ||||

| 2 | Moderate pruritus present most of the time but tolerable and not interfering with sleep pattern | ||||

| 3 | Continuous pruritus disturbing sleep pattern | ||||

| Bergasa 2006 | 0‐10 cm VAS | Mean difference of VAS: "Mean differences in measurements were determined by subtracting each on‐treatment value from each pretreatment value for each subject and calculating the mean of all the differences." | — | Not stated | Not available |

| Borgeat 1993 | 0‐10 verbal rating score | Evaluation 10 minutes after administration and then every 10 minutes during the first hour | 0 | No pruritus | Decrease of at least 4 points |

| 10 | Most severe pruritus imaginable | ||||

| Breneman 1992a | 4‐point scale | Follow‐up evaluations at weeks 1, 2, 3, 4 and 6 | 1 | No itching | Not available |

| 2 | Mild itching, occasionally noticeable | ||||

| 3 | Moderate itching, not interfering with daily life and/or sleep | ||||

| 4 | Severe itching, disturbing daily life and/or sleep | ||||

| Cho 1997 | 4‐point scale | Mean values and standard error of the mean | 1 | None | Not available |

| 2 | Mild | ||||

| 3 | Moderate | ||||

| 4 | Severe | ||||

| De Marchi 1992 | Scoring system proposed by Duo and modified by Mettang (Duo 1987; Mettang 1990) | Daily mean values and standard error | Scoring of severity: | Not available | |

| 1 | Pruritus without the need to scratch | ||||

| 2 | Pruritus with the need to scratch but without excoriations | ||||

| 3 | Pruritus that was unrelieved by scratching | ||||

| 4 | Pruritus accompanied by excoriations | ||||

| 5 | Total restlessness | ||||

| Scoring of distribution: | |||||

| 1 | Pruritus at a single location | ||||

| 2 | Scattered pruritus | ||||

| 3 | Generalised pruritus | ||||

| Scoring of frequency: each four short episodes (< 10 min) or one long episode (> 10 min) received 1 point, max. 5 points | |||||

| Scoring sleep disturbance: each episode of awaking due to pruritus received 2 points, max. 14 points | |||||

| The highest possible score for a 24‐hour period: 40 (with 35% of the points attributed to the night‐time period); total range: 0‐26 | |||||

| Duncan 1984 | 0‐3 score | Mean cumulative pruritus score (over 10 days) | 0 | No pruritus | Not available |

| 1 | Mild | ||||

| 2 | Moderate | ||||

| 3 | Severe | ||||

| Duque 2005 | 0‐10 cm VAS | Mean pruritus score; VAS was measured every visit for the intensity of itch in the last 24 hours | 0 | No itch | Not available |

| 10 | Very strong itch | ||||

| Feily 2012 | 0‐5 VAS | Mean weekly score | 0 | No pruritus | Not available |

| 5 | The worst pruritus | ||||

| Ghanei 2012 | Detailed pruritus score introduced by Duo (Duo 1987) | Mean scores, 95% confidence interval | Scoring of severity: | Not available | |

| 1 | Itching sensation without necessity of scratching | ||||

| 2 | Itching that necessitates scratching, but without excoriations | ||||

| 3 | Itching that necessitates frequent scratching | ||||

| 4 | Itching that necessitates scratching accompanied by excoriation | ||||

| 5 | Pruritus causing total restlessness | ||||

| Scoring of distribution: | |||||

| 1 | Pruritus in 2 areas of the body or less | ||||

| 2 | Pruritus in more than 2 areas of the body | ||||

| 3 | Generalised pruritus | ||||

| Scoring sleep disturbance: | |||||

| Every waking up due to pruritus received 2 points (max. 10 points) and every scratching due to pruritus received 1 point (max. 5 points); total range: 0‐45 | |||||

| Ghent 1988 | 0‐100 VAS | Summed 7‐day pruritus score on mean VAS | 0 | None | Preference of rifampicin |

| 100 | Severe | ||||

| Gunal 2004 | 0‐10 cm VAS | Mean and standard deviation; measurement once a day for each period | 0 | No itch | Not available |

| 10 | Worst possible imaginable itch | ||||

| Kuiper 2010 | 0‐10 cm VAS | Morning and evening VAS; proportion of responders | 0 | No pruritus | 40% reduction in pruritus visual analogue scale |

| 10 | Severe pruritus | ||||

| Kumagai 2010 | 0‐100 mm VAS | Mean VAS values of previous 12 hours (morning and evening) were calculated for the last 7 days of the pre‐observation period, the first and latter 7 days of the treatment period and the 8‐day post‐observation period; 95% confidence interval | 0 | No itch | "[A]ssuming an expected difference of 10.0 mm [with a common standard deviation (SD) of 25 mm]" |

| 100 | Strongest possible itch | ||||

| Legroux‐Crespel 2004 | 0‐10 cm VAS | Mean VAS scores; pruritus was evaluated on days 0, 7 and 14. | 0 | Not pruritus or sleep disorders | A marked improvement of pruritus was assessed by a decrease in the VAS score > 3. |

| 10 | Maximum intense of these disorders | ||||

| Makhlough 2010 | Detailed pruritus score introduced by Duo (Duo 1987) | Mean scores ± standard deviation; at the beginning of the study and at the end of weeks 1, 2, 3, and 4 of each study period | Scoring of severity: | Not available | |

| 1 | Itching sensation without necessity of scratching | ||||

| 2 | Itching that necessitates scratching, but without excoriations | ||||

| 4 | Itching that necessitates scratching accompanied by excoriation | ||||

| 5 | Pruritus causing total restlessness | ||||

| Scoring of distribution: | |||||

| 1 | Pruritus in 2 areas of the body or less | ||||

| 2 | Pruritus in more than 2 areas of the body | ||||

| 3 | Generalised pruritus | ||||

| Scoring sleep disturbance | |||||

| Every waking up due to pruritus received 2 points (max. 10 points) and every scratching due to pruritus received 1 point (max. 5 points); total range: 0‐30 | |||||

| Mapar 2015 | Modified Duo Score (0‐45) | Mean scores ± standard deviation; baseline, week 1, 2, 3, and 4 | 0‐45 | higher scores indicating more severe symptoms; (calculation of the final score is based on severity, distribution and sleep disturbance of pruritus) | Discontinuation of pruritus: zinc sulphate: 4 (20%); placebo: 1 (5%) |

| Mayo 2007 | 0‐10 cm VAS | Daily VAS scores were averaged | 0 | No pruritus | Clinically significant improvement defined as a 20% reduction in pruritus from baseline |

| 10 | Worst pruritus imaginable | ||||

| Murphy 2003 | 0‐10 cm VAS | Composite mean VAS score (morning and evening); mean score of the last 5 days of each week was calculated and referred to as the composite mean VAS score | 0 | No itch | Effect size of d = 0.8 |

| 10 | Maximum itch | ||||

| Naini 2007 | 0‐10 cm VAS | Mean pruritus score ± standard deviation; mean score of the last 5 days of each week was calculated and referred to as the composite mean VAS score | 0 | No itch | Not available |

| 10 | Worst possible itch | ||||

| Najafabadi 2012 | 0‐10 VAS | Mean pruritus score ± standard deviation; every two weeks | 0 | No itching | Not available |

| 10 | Worst pruritis | ||||

| Nakhaee 2015 | 0‐10 cm VAS | Mean pruritus score ± standard deviation at baseline and after 2 weeks | 0 | No pruritus | Not available |

| 10 | Worst pruritus imaginable | ||||

| Nasrollahi 2007 | Detailed pruritus score introduced by Duo (Duo 1987) | Not stated | "Assessment of pruritus was done using Detailed Pruritus Score introduced by Duo. The scores for sleep disturbances and intensity, area of pruritus were added and the final score at the beginning and at the end of the study were calculated (maximum score: 45)" | Not available | |

| O'Donohue 2005 | 0‐10 cm VAS; additional measurement of scratching activity by piezo‐electric vibration transducer |

Mean pruritus score standard error of the mean; On day 0 and day 1: every 15 min during the first hour, and hourly thereafter during waking hours. On days 2–5 recordings were made at 3 h intervals from 09:00 to 24:00 hours. | 0 | No pruritus | > 50% reduction in the severity of pruritus |

| 10 | Worst imaginable pruritus | ||||

| Omidian 2013 | 0‐5 VAS | Weekly mean score ± standard deviation | 0 | No itching | Not available |

| 5 | Worst pruritus | ||||

| Pakfetrat 2014 | Detailed pruritus score proposed by Duo (Duo 1987) | Mean scores ± standard deviation; the pruritus score was calculated before and at the end of the study. | Scoring of severity: | Not available | |

| 1 | Itching sensation without necessity of scratching | ||||

| 2 | Itching that necessitates scratching, but without excoriations | ||||

| 3 | Itching that necessitates frequent scratching | ||||

| 4 | Itching that necessitates scratching accompanied by excoriation | ||||

| 5 | Pruritus causing total restlessness | ||||

| Scoring of distribution: | |||||

| 1 | Pruritus in 2 areas of the body or less | ||||

| 2 | Pruritus in more than 2 areas of the body | ||||

| 3 | Generalised pruritus | ||||

| Scoring sleep disturbance: | |||||

| Every waking up due to pruritus received 2 points (max. 10 points) and every scratching due to pruritus received 1 point (max. 5 points); range: 0‐45 | |||||

| Pauli‐Magnus 2000 | 0‐10 cm VAS | Mean weekly pruritus score in percent of initial pruritus score; 95% confidence interval | 0 | No pruritus | Not available |

| 10 | Unbearable pruritus | ||||

| Detailed pruritus score proposed by Duo (Duo 1987) | Mean detailed score and 95% confidence interval | Scoring of severity: | |||

| 1 | Itching sensation without necessity of scratching | ||||

| 2 | Itching that necessitates scratching, but without excoriations | ||||

| 3 | Itching that necessitates frequent scratching | ||||

| 4 | Itching that necessitates scratching accompanied by excoriation | ||||

| 5 | Pruritus causing total restlessness | ||||

| Scoring of distribution: | |||||

| 1 | Pruritus in 2 areas of the body or less | ||||

| 2 | Pruritus in more than 2 areas of the body | ||||

| 3 | Generalised pruritus | ||||

| Scoring sleep disturbance: | |||||

| Every waking up due to pruritus received 2 points (max. 10 points) and every scratching due to pruritus received 1 point (max. 5 points); range: 0‐45 | |||||

| Pederson 1980 | Questionnaire as suggested by Lowrie and Ingham (Lowrie 1975) | Pruritus scores in each individual are presented at week 0, 8 and 16; few information | 1 | I never itch | Not available |

| 2 | I itch rarely but never complain | ||||

| 3 | I itch occasionally with mild annoyance | ||||

| 4 | I itch often; it may be severe but I can be active or rest easily | ||||

| 5 | I itch often; it may be severe and interferes with rest but not activity | ||||

| 6 | I itch always; it is severe and interferes both with rest and activity | ||||

| Statements were arranged in nine paired response alternatives, allowing the ranking of the itching as a severity continuum on a scale of one (no itching) to 10 (severe constant itching) | |||||

| Peer 1996 | 0‐10 cm VAS | Mean daily scores (recorded every 6 hours); medians and interquartile ranges are reported | 0 | No pruritus | Not available |

| 10 | Maximum intensity of pruritus | ||||

|

Podesta 1991a |

0‐100 cm VAS | Mean pruritus score; pruritus was evaluated 15 days before and daily (between 8 and 12 AM, 12‐8 PM, and 8‐8 AM) during treatment | 100 | Pruritus that interfered with sleep, altered daily activities, or resulted in self‐inflicted skin‐breakdown | Full response to treatment was defined as the complete lack of pruritus and a partial response as a 50% reduction in the pruritus score |

| Pour‐Reza‐Gholi 2007 | Not stated | Not stated | Response to treatment was recorded as: complete improvement (no more itching) relative improvement (reduction of the symptom) no effect (symptom remained unchanged or worsened) | Not available | |

| Shirazian 2013 | Pruritus Severity Questionnaire | Biweekly mean scores ± standard deviation | Maximum pruritus score on the survey: 21 points | Not available | |

| 5 | Active itching (yes = 5) | ||||

| 4 | Itching affecting sleep or other activities in the past few days (yes = 4) | ||||

| In the past few days, how would you describe your itching? | |||||

| 0 | None | ||||

| 1 | Mild itching | ||||

| 3 | Moderate itching | ||||

| 4 | Severe itching | ||||

| In the past few days, what part of your body has felt itchy? | |||||

| 1 | Localised itching | ||||

| 2 | Itching in most of the body | ||||

| 3 | Itching in all of the body | ||||

| 5 | Use of medications for itching (yes = 5) | ||||

| Silva 1994 | 0‐3 score | Depicted as a percent of maximum score possible ± standard error; pruritus intensity was scored three times daily | 0 | Absent | Reduction of at least 50% |

| 1 | Pruritus at rest or during usual tasks but not interfering with its accomplishment | ||||

| 2 | Pruritus perturbing but not interrupting performance of regular tasks | ||||

| 3 | Pruritus causing interruption of tasks or sleep | ||||

| Silverberg 1977 | 0‐3 score | Mean of all daily scores; score for the 3 weeks before treatment was the mean of 21 days' values and the score during treatment was the mean of 28 days' values. | 0 | None | Not available |

| 1 | Slight | ||||

| 2 | Moderate | ||||

| 3 | Great | ||||

| Smith 1997a | 1‐4 score | Not stated | 1 | Periodic at night only | Not available |

| 2 | Periodic during the day and night | ||||

| 3 | Periodic during the day, but interferes with sleep at night | ||||

| 4 | Interferes with daily activities as well as sleep at night | ||||

| 0‐4 score | Categorial evaluation; median improvement; 25th and 75th percentile | Overall changes in pruritus after 4‐6 weeks of therapy were graded as follows: | Not available | ||

| 0 | Increased pruritus | ||||

| 1 | No decrease | ||||

| 2 | Slight but definite decrease in pruritus | ||||

| 3 | Moderate decrease in pruritus | ||||

| 4 | Complete resolution of pruritus | ||||

| Tarng 1996 | 4‐point scale | Weekly mean values ± standard deviation | 1 | No itching | Not available |

| 2 | Mild itching, occasionally noticeable | ||||

| 3 | Moderate itching, not interfering with daily life and/or sleep | ||||

| 4 | Severe itching, disturbing daily life and/or sleep | ||||

| Terg 2002 | 0‐10 cm VAS | Mean values ± standard deviation of each period; assessment 1 week before starting treatment and during the 5 weeks of the study; Daytime pruritus was assessed before retiring to sleep while night‐time pruritus was assessed at wake‐up. | 0 | Absence of pruritus | Complete response was defined as disappearance of pruritus and partial response as 50% reduction in the pruritus score |

| 10 | Were pruritus that interfered with sleep, altered daily activities or resulted in self‐inflicted skin breakdown | ||||

|

Turner 1994a Turner 1994b |

0‐100 mm VAS | Mean VAS scores for the last 7 days (daily assessment reflecting the preceding 24 hours); 95% confidence interval | 0 | No itch | Subjective itch improvement (yes or no) |

| 100 | Severe | ||||

| Vessal 2010 | 0‐10 cm VAS | Weekly mean scores ± standard deviation for 12 weeks | 0 | Absence of pruritus | Not available |

| 10 | Greatest severity of symptoms | ||||

| Villamil 2005 | 0‐100 mm VAS | Daily mean VAS scores for the 7 days (measurement at baseline and every 12 hours before going to bed and after awakening); 95% confidence interval | 0 | Absence of pruritus | Difference of 30% |

| 100 | Unbearable intensity | ||||

|

Wikström 2005a Wikström 2005b |

0‐100 mm VAS | Mean worst itching VAS from run‐in to the end of week 4 (study 1) and week 2 (study 2) during the previous 12 hours; assessment every 12 hours during the run‐in period and throughout the studies; 95% confidence interval and standard deviation |

0 | No itching | Patient responders as defined by a reduction from run‐in of at least 50% in "worst itching" VAS |

| 100 | Worst itching ever | ||||

| Wolfhagen 1997 | 0‐100 mm VAS | Mean daytime/night‐time scores each day; ± standard error of the mean and 95% confidence interval | 0 | No itching | Not available |

| 100 | Unbearable itching | ||||

| Young 2009 | 0‐10 cm VAS | [1 − (mean VAS at the end of the study)/(mean VAS at baseline)*100] | Itch intensity after a mosquito bite | Not available | |

| Individual itch on its best intensity | |||||

| Individual itch on its worst intensity | |||||

| Yue 2015 | 0‐10 cm VAS | Biweekly mean scores ± standard deviation (12 weeks) | 0 | No pruritus | Not available |

| 10 | Worst pruritus imaginable | ||||

| Modified Duo's VAG: 0 to 40 | mean scores ± standard deviation at baseline and week 12 | 0 | Higher scores indicating more severe symptoms; (based on criteria such as scratching, severity, frequency, distribution of pruritus, number of sleeping hours, and frequency of waking‐up during the night for scratching) | ||

| 40 | |||||

| Zylicz 2003 | 0 ‐10 numerical analogue scale | Mean value of 7 days ± standard error and 95% confidence interval | 0 | No symptoms | Proportion of clinical responses defined as a pruritus reduction of at least 50% in the last 3 days of each period as compared to the last 3 days of the run‐in period |

| 10 | Worst possible symptoms | ||||

| Özaykan 2001 | Scoring system proposed by Duo and modified by Mettang (Duo 1987; Mettang 1990) | Weekly mean scores | 0‐48 | Period: 0‐3 | Not available |

| Intensity: 0‐10 | |||||

| Allocation: 0‐10 | |||||

| Frequency: 0‐10 | |||||

| Sleeping‐time: 0‐10 | |||||

| Wake‐up time: 0‐5 | |||||

NRS: numerical rating scale; VAS: visual analogue scale.

2. Study interventions and numbers attached to intervention.

| Substance and participants | Dose |

No. of participants included (with dropouts and placebo) |

Authors |

Total number of participants (with dropouts and placebo) |

|

| Paroxetine: 26 participants | |||||

| Palliative care patients | Paroxetine | 20 mg/d | 26 | Zylicz 2003 | 26 |

| Naltrexone: 100 participants | |||||

| UP | Naltrexone | 50 mg/d | 15 | Peer 1996 | 126 (26 from loratidine group) |

| UP | Naltrexone | 50 mg/d | 23 | Pauli‐Magnus 2000 | |

| UP | Naltrexone vs. loratadine | 50 mg/d 50 mg/d |

26 26 |

Legroux‐Crespel 2004 | |

| CP | Naltrexone | 50 mg/d | 16 | Wolfhagen 1997 | |

| CP | Naltrexone | 50 mg/d | 20 | Terg 2002 | |

| Nalfurafine: 450 participants | |||||

| UP | Nalfurafine | 5 µg 3x/week IV | 79 | Wikström 2005a | 450 |

| UP | Nalfurafine | 5 µg 3x/week IV | 34 | Wikström 2005b | |

| UP | Nalfurafine | 2.5µg/d or 5 µg/d | 337 | Kumagai 2010 | |

| Ondansetron: 270 participants | |||||

| UP | Ondansetron | 8 mg 3x/d | 24 | Murphy 2003 | 270 (10 from cyproheptadine and 67 from pregabalin group) |

| UP | Ondansetron | 8 mg 3x/d | 19 | Ashmore 2000 | |

| CP | Ondansetron | 8 mg 2x/d, 5 days | 19 | O'Donohue 2005 | |

| UP | Ondansetron/cyproheptadine | 8 mg/d, 30 days | 20 (10/10) | Özaykan 2001 | |

| UP | Ondansetron vs. pregabalin vs. placebo | ondansetron: 8 mg/d pregabalin: 75 mg twice‐weekly |

188 (64/67/57) | Yue 2015 | |

| Sertraline: 12 participants | |||||

| CP | Sertraline | 25–100 mg/d | 12 | Mayo 2007 | 12 |

| Gabapentin: 127 participants | |||||

| UP | Gabapentin | 300 mg 3x/week | 25 | Gunal 2004 | 127 (26 from ketotifen group) |

| UP | Gabapentin | 400 mg 2x/week | 34 | Naini 2007 | |

| CP | Gabapentin | 300 mg‐2400 mg/d | 16 | Bergasa 2006 | |

| UP | Gabapentin vs ketotifen | Gabapentin 100 mg daily Ketotifen 1 mg twice daily |

26 26 |

Amirkhanlou 2016 | |

| Rifampicin: 23/22 participants | |||||

| CP | Rifampicin | 300 mg 2x/d | 14 | Podesta 1991a | 45 |

| CP | Rifampicin | 150 mg 2‐3x/d | 9 | Ghent 1988 | |

| CP | Rifampicin | 10 mg/kg/d | 22 | Bachs 1989 | |

| Phenobarbitone | 3 mg/kg/d | ||||

| Doxepin: 24 participants | |||||

| UP | Doxepin | 10 mg 2x/d | 24 | Pour‐Reza‐Gholi 2007 | 24 |

| Cholestyramine: 18 participants | |||||

| UP | Cholestyramine | 5 g 2x/d | 10 | Silverberg 1977 | 18 |

| CP | Cholestyramine | 4 g/d | 8 for 2 weeks each | Duncan 1984 | |

| Terfenadine | 60‐180 mg/d | ||||

| Chlorpheniramine | 4 mg–12 mg/d | ||||

| Colesevelam: 38 participants | |||||

| CP | Colesevelam | 1875 mg 2x/d | 38 | Kuiper 2010 | 38 |

| Thalidomide: 29 participants | |||||

| UP | Thalidomide | 100 mg/d | 29 | Silva 1994 | 29 |

| Montelukast: 16 participants | |||||

| UP | Montelukast | 10 mg/d | 16 | Nasrollahi 2007 | 16 |

| Flumecinol: 69 participants | |||||

| CP | Flumecinol low dose | 600 mg 1x/week | 50 | Turner 1994a | 69 |

| CP | Flumecinol high dose | 300 mg/d | 19 | Turner 1994b | |

| Erythropoietin: 20 participants | |||||

| UP | Erythropoietin | 36 units/kg body weight 3x/week IV | 20 | De Marchi 1992 | 20 |

| Cromolyn Sodium: 122 participants | |||||

| UP | Topical cromolyn sodium (CS) | Topical CS 4% 2x/d | 60 | Feily 2012 | 122 |

| UP | Oral CS | 135 mg 3x/d | 62 | Vessal 2010 | |

| Activated oral charcoal: 11 participants | |||||

| UP | Activated oral charcoal | 6 g/d | 20 | Pederson 1980 | 11 |

| Propofol: 12 participants | |||||

| CP | Propofol | 15 mg (1.5 mL)/d IV | 12 | Borgeat 1993 | 12 |

| Lidocaine: 18 participants | |||||

| CP | Lidocaine | 100 mg/d IV | 18 | Villamil 2005 | 18 |

| Topical capsaicin: 105 participants | |||||

| UP | Capsaicin | 0.03% ointment 4x/d | 34 | Makhlough 2010 | 105 |

| UP | Capsaicin | 0.025% cream 4x/d | 19 | Tarng 1996 | |

| UP | Capsaicin | 0.025% cream 4x/d | 22 | Cho 1997 | |

| UP | Capsaicin | 0.025% cream 4x/d | 7 | Breneman 1992a | |

| Tacrolimus: 22 participants | |||||

| UP | Tacrolimus | 0.1% ointment 2x/d | 22 | Duque 2005 | 22 |

| Pramoxine‐HCl: 28 participants | |||||

| UP | Pramoxine‐HCl | 1% lotion 2x/d | 28 | Young 2009 | 28 |

| Hydroxyzine/Pentoxifylline/Indomethacin/Triamcinolone: 65 participants per intervention | |||||

| HIV‐1 disease patients | Hydroxyzine‐HCl with or without doxepin‐HCl at night | 25 mg 3x/d or 25 mg at bedtime | 10 | Smith 1997a | 65 (10 from pentoxifylline, 10 from indomethacin, 10 from triamcinolone, 8 from avena sativa and 9 from vinegar group) |

| Pentoxifylline | 400 mg 3x/d | 10 | |||

| Indomethacin | 25 mg 3x/d | 10 | |||

| Triamcinolone | 0.025% lotion120 mL/week | 10 | |||

| UP | Hydroxyzine vs avena sativa vs vinegar | Hydroxyzine tablet, 10‐mg tablets every night Avena sativa lotion, twice daily Vinegar solution (30‐mL synthetic white vinegar 5% in 500 mL of water), twice daily |

25 (8/8/9) | Nakhaee 2015 | |

| Ergocalciferol: 50 participants | |||||

| UP | Ergocalciferol | 50.000 IU capsule, 1 pill/week | 50 | Shirazian 2013 | 50 |

| Nicotinamide: 50 participants | |||||

| UP | Nicotinamide | 500 mg 2x/d | 50 | Omidian 2013 | 50 |

| Omega‐3 fatty acids: 22 participants | |||||

| UP | Omega‐3 fatty acids | 1 g omega‐3 capsule 3x/d | 22 | Ghanei 2012 | 22 |

| Turmeric: 100 participants | |||||

| UP | Turmeric | 500 mg 3x/d | 100 | Pakfetrat 2014 | 100 |

| Zinc sulphate: 80 participants | |||||

| UP | Zinc sulphate | 220 mg 2x/d | 40 | Najafabadi 2012 | 80 |

| UP | Zinc sulphate | 220 mg daily | 40 | Mapar 2015 | |

CP: cholestatic pruritus; CS: cromolyn sodium; IU: international unit; UP: uraemic pruritus.

3. Secondary outcomes.

| Quality of life | Method/scale | Results |

| Yue 2015 | Health‐related quality of life: Mental Component Summary scale (MCS) from the 12‐item short‐form (SF‐12; version 2); SF‐12 was scored from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better HRQoL | Results: Post‐treatment scores:

Mean change from baseline versus placebo (95% CI): statistically significant for pregabalin and not statistically significant for ondansetron or placebo

|

| Kuiper 2010 | Quality‐of‐life scores: Short Form 36 and Liver Disease Symptom Index 2.0 |

No statistically significant changes were found. Both treatment groups were comparable before and after treatment: Short Form 36 questionnaire in the colesevelam group before and after treatment physical functioning (P = 0.67), role physical functioning (P = 0.50), bodily pain (P = 1.00), general health (P = 0.48), vitality (P = 0.90), social functioning (P = 0.37), emotional functioning (P = 0.17) and mental health (P = 0.26) |

| Turner 1994a | VAS: 0 = able to cope with normal activities 100 = completely incapacitated |

Median improvement in quality of life assessment between flumecinol and placebo was 5.0 mm (95% CI 0.4 to 13.0, P = 0.02), in favour of flumecinol At entry: active = 26, placebo = 11 At completion: active = 21, placebo = 7 Median fall: active = 3.5, placebo = 0.1 |