Abstract

Background

Osteomyelitis (both acute and chronic) is one of the most common infectious complications in people with sickle cell disease. There is no standardized approach to antibiotic therapy and treatment is likely to vary from country to country. Thus, there is a need to identify the efficacy and safety of different antibiotic treatment approaches for people with sickle cell disease suffering from osteomyelitis. This is an update of a previously published Cochrane Review.

Objectives

To determine whether an empirical antibiotic treatment approach (monotherapy or combination therapy) is effective and safe as compared to pathogen‐directed antibiotic treatment and whether this effectiveness and safety is dependent on different treatment regimens, age or setting.

Search methods

We searched The Group's Haemoglobinopathies Trials Register, which comprises references identified from comprehensive electronic database searches and handsearching of relevant journals and abstract books of conference proceedings. We also searched the LILACS database (1982 to 20 October 2016), African Index Medicus (20 October 2016), ISI Web of Knowledge (20 October 2016) and World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (20 October 2016).

Date of most recent search of the Cochrane Cystic Fibrosis and Genetic Disorders Group's Haemoglobinopathies Trials Register: 18 August 2016.

Selection criteria

We searched for published or unpublished randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials.

Data collection and analysis

Each author intended to independently extract data and assess trial quality by standard Cochrane methodologies, but no eligible randomised controlled trials were identified.

Main results

This update was unable to find any randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials on antibiotic treatment approaches for osteomyelitis in people with sickle cell disease.

Authors' conclusions

We were unable to identify any relevant trials on the efficacy and safety of the antibiotic treatment approaches for people with sickle cell disease suffering from osteomyelitis. Randomised controlled trials are needed to establish the optimum antibiotic treatment for this condition.

Keywords: Humans; Anemia, Sickle Cell; Anemia, Sickle Cell/complications; Anti‐Bacterial Agents; Anti‐Bacterial Agents/therapeutic use; Osteomyelitis; Osteomyelitis/drug therapy

Antibiotics for treating osteomyelitis in people with sickle cell disease

Review question

We reviewed the evidence to determine whether antibiotics (alone or in combination) given to people with sickle cell disease who have osteomyelitis (a bone infection) before the specific bacterium causing an infection is known is effective and safe as compared to bacterium‐directed antibiotic treatment and whether this effectiveness and safety is dependent on different treatment regimens, age or setting. This is an update of a previously published Cochrane Review.

Background

Sickle cell disease affects millions of people throughout the world. Osteomyelitis is one of the major complications. Antibiotics are given to treat it, but there is no worldwide standard treatment.

Search date

The evidence is current to: 18 August 2016.

Study characteristics

There are no trials included in this review.

Key results

We conclude that a randomised controlled trial should attempt to answer these questions.

Background

Description of the condition

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a group of genetic haemoglobin disorders (Ballas 2010; Pauling 1949; Orkin 2010; Rees 2010) which have their origins in sub‐Saharan Africa and the Indian sub‐continent (Stuart 2004; Weatherall 2006). Recently, SCD history and others aspects have been reviewed (Mousa 2010; Prabhakar 2010; Serjeant 2010). Population mobility has spread the disorders through Europe, Asia and the Americas. The term SCD includes sickle cell anaemia (Hb SS), haemoglobin S combined with haemoglobin C (Hb SC), haemoglobin S associated with ß Thalassemia (Sß0 Thal and Sß+ Thal) and other double heterozygous conditions which cause clinical disease (Saunthararajah 2004; Serjeant 2001; Weatherall 2006). Haemoglobin S combined with normal haemoglobin (A) is known as sickle trait (AS) and is asymptomatic and therefore not part of this review.

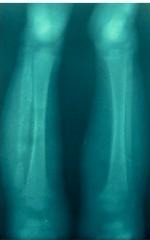

The pathophysiology of SCD has been reviewed extensively (Alexy 2010; Aslan 2007; Buchanan 2010; Darghouth 2011; Hagar 2008; Hebbel 2004; Kato 2007; Mack 2006; Rees 2010; Steinberg 2006; Stuart 2004; Weatherall 2006; Wood 2008). Although SCD is primarily a defect of red blood cells (a haematological defect); it is often observed in the evolution of SCD that the changes in the red blood cells result in damage to blood vessels (vasculopathy) (Hebbel 2004; Kato 2009; Wood 2008), it is caused by impaired nitric oxide pathway (Akinsheye 2010), and severe osteoarticular infections (Meddeb 2003). One of these infections is osteomyelitis, see additional figure attached (Figure 1); the pathophysiology of this condition has been reviewed by many researchers (Ciampolini 2000; Lew 2004; Paluska 2004). Recently, one study has shown that certain specific human leukocyte antigens haplotypes modify the risk of osteomyelitis in this population (Al‐Ola 2008). In addition, there have been two reviews published regarding the pathophysiology and clinical manifestations about osteomyelitis in people with SCD (Almeida 2005; Ejindu 2007). Recently, the effect of sickle cell disease on infection was reviewed (Booth 2010).

Figure 1.

Radiological image of bone sequestrum in a Venezuelan with SCD suffering from chronic osteomyelitis Photo captured by Dr. Arturo Martí‐Carvajal

Osteomyelitis (both acute and chronic) is one of the most common infectious complications in people with SCD (Bennet 2006). The prevalence of osteomyelitis ranges between 12% and 17.8% (Bahebeck 2004; Neonato 2000; Tarer 2006); a possible relationship to spleen dysfunction in SCD has also been reported (William 2007). Osteomyelitis is characterized by an inflammatory process accompanied by bone destruction (Begue 2001; Lew 2004). The most common infecting organisms are the salmonella species and Staphylococcus aureus (Burnett 1998; Epps 1991; Nwadiaro 2000; Sadat‐Ali 1998; Tekou 2000). Streptococcus pneumoniae and bacteroides species have also been described (Carek 2001; Lew 2004; Mansingh 2003). Pathogen prevalence of bacterial osteomyelitis in people with SCD varies geographically (Thanni 2006). In the USA and Europe, salmonellae are the most common bacterial pathogens; whereas Staphylococcus aureus is the most common pathogen in sub‐Saharan Africa and the Middle East (Thanni 2006). Osteomyelitis is a debilitating condition in rural African communities (Ibingira 2003; Onche 2004) and is most common in people under 20 years old (Ibingira 2003; Nwadiaro 2000). Osteomyelitis is associated with a risk of physical and psychologic complications (Huber 2002).

Osteomyelitis and avascular necrosis are often interrelated and concurrent (Kim 2002; Serjeant 1992). A high level of technology is required to differentiate between bone infarction and acute osteomyelitis in people with SCD (Skaggs 2001; Witjes 2006). The difficulty in diagnosing this complication with confidence is well documented; a confirmed diagnosis of osteomyelitis often depends on the results of a bone biopsy and bone cultures (Sia 2006). The isolation of the infectious agent is not easy and least likely to be achieved in developing countries; thus, empirical therapy, based on epidemiological references, is essential.

Description of the intervention

Based on the above, antibiotic therapy in people with SCD suffering from osteomyelitis is not standardized worldwide. The fact that different bacteria necessitate the use of different antibiotics leads to non‐standardized therapy, although different prescribing practices, drug availability, pathogen frequency and drug resistance in different countries may also be responsible. Additionally, the choice of antibiotics may be affected by the need for prolonged antibiotic therapy and whether surgical drainage is required. As with other orthopedic injuries in this population, a multidisciplinary management of osteomyelitis for people with SCD is needed (Sathappan 2006). Osteomyelitis is also more frequent in those with more severe disease, thus further increasing their morbidity. The available literature on the treatment of osteomyelitis is not sufficient to determine the best agent(s), route, or duration of antibiotic therapy (Lazzarini 2005).

Why it is important to do this review

This Cochrane Review aims to determine the effectiveness and safety of the various antibiotic treatment approaches for people with SCD suffering from osteomyelitis. This is an update of a previously published Cochrane Review (Martí‐Carvajal 2009; Martí‐Carvajal 2012).

Objectives

To determine whether an empirical antibiotic treatment approach (monotherapy or combination therapy) is effective and safe as compared to pathogen‐directed antibiotic treatment and whether this effectiveness and safety is dependent on different treatment regimens, age or setting.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled clinical trials. We planned to include quasi‐randomised controlled trials if there was sufficient evidence that intervention and control groups were similar at baseline.

Types of participants

People with all types of SCD irrespective of age, type of osteomyelitis (acute, chronic), cause, or setting.

Osteomyelitis was defined as a progressive inflammatory destruction and new apposition of bone (Lew 2004). Acute osteomyelitis was regarded as a newly recognized bone infection; and chronic osteomyelitis was defined as infection associated with necrotic bone with or without fistulous tracts.

The criteria used for the diagnosis of osteomyelitis were (modified from Le Saux 2002):

clinical signs of osteomyelitis (swelling, warmth, tenderness and decreased ability to weight bear);

clinical signs and a compatible radiological study (nuclear scan or radiography);

confirmatory diagnosis of osteomyelitis based on the results of a bone biopsy and bone cultures.

Types of interventions

We included comparative trials of antibiotics (used either alone or in combination), administered parenterally or orally, or both, and compared with another antibiotic.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Time to resolution of signs and symptoms of active infection

Secondary outcomes

Residual pain

Residual disability (from a validated scale)

Function and movement of affected area (from a validated scale)

Quality of life (measured from a validated scale)

Number of days off work or school or normal daily activities related to infection

Adverse events, if possible, these will be classified as mild, moderate and severe

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Relevant trials were identified from the Cochrane Cystic Fibrosis and Genetic Disorders Group's Haemoglobinopathies Trials Register using the terms: 'sickle cell' AND 'antibiotics'.

The Haemoglobinopathies Trials Register is compiled from electronic searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (updated each new issue of the Cochrane Library) and weekly searches of MEDLINE. Unpublished work was identified by searching through the abstract books of four major conferences: the European Haematology Association conference; the American Society of Hematology conference; the Caribbean Health Research Council Meetings; and the National Sickle Cell Disease Program Annual Meeting. For full details of all searching activities for the register, please see the relevant section of the Cochrane Cystic Fibrosis and Genetic Disorders Group Module.

We undertook searches of the following registers and databases: LILACS (From 11 November 2010 to 20 October 2016); African Index Medicus (up to 20 October 2016); ISI Web of Knowledge (2008 to 20 October 2016); and World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform. The latest searches of these registers and databases was 20 October 2016. We used the search terms 'sickle cell' AND 'osteomyelitis' for all these registers and databases.

The search in LILACS was performed using an RCT filter plus combined with the terms 'sickle' and 'osteomyelitis' (Appendix 1). The search in African Index Medicus was performed using an RCT filter plus combined with the terms 'sickle' and 'osteomyelitis' (Appendix 2). The search in ISI Web of Knowledge was performed using an RCT filter plus combined with the terms 'sickle' and 'osteomyelitis' (Appendix 3). The search in World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform was performed using an RCT filter plus combined with the terms 'sickle' and 'osteomyelitis' (Appendix 4).

Date of the most recent search of the Cochrane Cystic Fibrosis and Genetic Disorders Group's Haemoglobinopathies Trials Register: 18 August 2016.

Searching other resources

The bibliographic references of all retrieved literature was reviewed for additional reports of trials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two authors (AM, LA) assessed each reference identified by the searches to see if they met the inclusion criteria.

We were unable to identify any randomised controlled trials eligible for inclusion in this review. Therefore, we could not perform the data analyses that we had planned. If, in the future, trials are identified and included in the review, we will adhere to the protocol described in detail below in the remainder of this section.

Data extraction and management

Each author will independently undertake data extraction using a customised data extraction form. The review authors will resolve any disagreements by consensus or through discussion with the Contact Editor. Once any disagreements have been resolved, we will record the extracted data on the final data extraction form.

For both acute and chronic osteomyelitis, we plan to group outcome data into those measured at up to one month, two, three, six, twelve months and annually thereafter. These groupings of time‐points were decided upon based on our clinical experience. If outcome data were recorded at other time periods, then consideration will given to examining these as well.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Each author will independently assess the quality of each trial using a simple form and will follow the domain‐based evaluation as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 5.1 (Higgins 2011). We will compare the assessments and discuss any discrepancies between the authors. We aim to resolve any disagreements through discussion.

We will assess the following domains as having either a low, unclear, or high risk of bias.

Generation of the allocation sequence

Allocation concealment

Blinding (of participants, assessors and providers of care)

Incomplete outcome data

Selective outcome reporting

Other sources of bias

For each trial the authors will classify the overall risk of bias as 'high' or 'low' or 'unclear'.

The trials will be classified as follows:

Generation of the allocation sequence

We will grade each trial with regards to the generation of the allocation sequence as follows:

'Low risk', if methods of randomisation include e.g. a random number table, computer‐generated lists or similar methods;

'Unclear risk', if the trial is described as randomised, but no description of the methods used to allocate participants to treatment group was given;

'High risk', if methods of randomisation include e.g. alternation; the use of case record numbers, dates of birth or day of the week, and any procedure that is entirely transparent before allocation, such as an open list of random numbers.

Allocation concealment

We will grade each trial with regards to allocation concealment as follows:

'Low risk', if the allocation of participants involved, e.g. a central independent unit, on‐site locked computer, identically appearing numbered drug bottles or containers prepared by an independent pharmacist or investigator, or sealed opaque envelopes;

'Unclear risk', if the method used to conceal the allocation was not described;

'High risk', if the allocation sequence was known to, or could be deciphered by the investigators who assigned participants or if the trial was quasi‐randomised.

Blinding (of participants, assessors and providers of care)

We will assess each trial as having either a low, unclear or high risk of bias with regard to the following levels of blinding:

blinding of clinician (person delivering treatment) to treatment allocation;

blinding of participant to treatment allocation;

blinding of outcome assessor to treatment allocation.

Incomplete outcome data

Reasons for missing data will be discussed. Trials will be graded as:

'Low risk', if the numbers and reasons for drop‐outs and withdrawals in all intervention groups were described or if it was specified that there were no drop‐outs or withdrawals;

'Unclear risk', if the report gave the impression that there had been no drop‐outs or withdrawals, but this was not specifically stated;

'High risk', if the number or reasons for drop‐outs and withdrawals were not described.

We will also evaluate the risk of attrition bias, as estimated by the percentage of participants lost. Trials with a total attrition of more than 30% or where differences between the groups exceed 10%, or both, will be excluded from meta‐analysis but will be included in the review.

We will further examine the percentages of dropouts overall in each trial and per randomisation arm and we will evaluate whether intention‐to‐treat analysis has been performed or could be performed from the published information.

Selective outcome reporting

When there is suspicion of or direct evidence for selective outcome reporting we will ask trial authors for additional information (trial protocols if possible). We aim to assess the risk of bias due to selective reporting of outcomes for the trial as a whole, rather than for each outcome. We will grade each trial with regards to selective outcome reporting as follows:

'Low risk', if the trial protocol is available and all of the trial's pre‐specified (primary and secondary) outcomes that are of interest in the review have been reported in the pre‐specified way; the trial protocol is not available but it is clear that the published reports include all expected outcomes, including those that were pre‐specified.

'Unclear risk', if there is insufficient information to permit judgement of ‘Yes’ or ‘No’.

'High risk', if, for example, not all of the study’s pre‐specified primary outcomes have been reported; one or more primary outcomes is reported using measurements, analysis methods or subsets of the data (e.g. subscales) that were not pre‐specified;

Other sources of bias

We will assess whether included trials are free of other problems that could put them at a high risk of bias. We will grade each trial with regards to other sources of bias as follows:

'Low risk', if the study appears to be free of other sources of bias.

'Unclear risk', if there is insufficient information to assess whether an important risk of bias exists; or there is an insufficient rationale or evidence that an identified problem will introduce bias.

'High risk', if, for example, the trial has a potential source of bias related to the specific study design used; or was stopped early due to some data‐dependent process (including a formal‐stopping rule).

Summary of findings tables

We will add the GRADE proposals (Guyatt 2008) to assess the quality of the body of evidence associated with the following outcomes: time to resolution of signs and symptoms of active infection; quality of life; and safety. We will construct a summary of findings table (SoF) using the GRADEPro software (GradePro 2008). GRADE classifies the quality of a body of evidence based on the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association reflects the item being assessed.

Measures of treatment effect

To estimate overall time to resolution of signs and symptoms of active infection by the end of therapy, the authors will calculate hazard ratios (HR), with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

We plan to summarise binary outcome measures (residual pain, and safety) in terms of risk ratios (RR), with 95% CI, by extracting numbers in each group. For continuous outcomes (number of days off work or school or normal daily activities related to infection) we plan to record either mean change from baseline for each group or mean post‐treatment or intervention values and their standard deviation or standard error for each group. We also plan to calculate a pooled estimate of treatment effect by calculating the mean difference (MD). We plan to calculate the standardized mean difference (SMD) for residual disability, function and movement of affected area, and quality of life. If statistics are missing (such as standard deviations), we will try to extract them from other relevant information in the paper, such as P values and confidence intervals. If this is not possible, the first author of the paper will be contacted.

We will examine data to see if there is evidence of a skewed distribution using the means and standard deviations as described in the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews for Interventions (Higgins 2011). Continuous data will be classed as being skewed if the standard deviation is over half the size of the mean (this is only true if the data can take positive values only, it does not apply to change data, for example). If data are skewed, when appropriate, we will aim to present log‐transformed data. Skewed data will not be pooled, the results will be presented in additional tables, with no statistical analyses performed on these data.

Dealing with missing data

If necessary, in the future, we will contact the authors of included trials for any missing data.

In order to allow an intention‐to‐treat analysis, we will seek data on the number of participants by allocated treatment group, irrespective of compliance and whether or not the participant was later thought to be ineligible or otherwise excluded from treatment or follow up.

Regarding issues of censoring, we will conduct the analysis according the recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews for Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We will quantify statistical heterogeneity using the I² statistic, which describes the percentage of total variation across trials that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error (Higgins 2003). We will consider there to be significant statistical heterogeneity if I² is over 50% (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

We will attempt to assess whether the review is subject to publication bias by using a funnel plot to graphically illustrate variability between trials. If asymmetry is detected, causes other than publication bias will be explored.

We will attempt to contact subject experts, to search the USA FDA web site and any other relevant register databases in an attempt to identify unpublished papers. Our aim is to reduce the chance of outcome reporting bias.

Data synthesis

If any future identified trials are comparable enough, we will summarize their findings using a fixed‐effect model, if not (I² is over 50%), we will use a random‐effects model, and we will devote to search the cause of the heterogeneity according the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews for Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If we identify significant heterogeneity we plan to investigate identify possible causes by exploring the effect of participant, intervention and study design characteristics.

We anticipate clinical heterogeneity in the effect of the intervention and, if this is found, plan to conduct the following subgroup analyses if possible:

microbiological cause of osteomyelitis;

acute versus chronic osteomyelitis;

type of antibiotic;

age groups (children, adults).

This subgroup analysis will be only conducted for the primary outcome:

time to resolution of signs and symptoms of active infection.

Sensitivity analysis

If sufficient trials are identified, we plan to conduct a sensitivity analysis comparing the results using all trials with those with an overall high risk of bias (studies classified as having a 'low risk of bias' versus those identified as having a 'high risk of bias') (Higgins 2011).

Results

Description of studies

For the 2012 update four potentially relevant references were identified through the initial bibliographical searches. After manually checking the titles and abstracts, none of the papers were regarded as eligible for further evaluation as they did not report on antibiotic therapy for osteomyelitis in SCD (Akakpo‐Numado 2008; Akakpo‐Numado 2009; Berger 2009; Hernigou 2010). See Characteristics of excluded studies for details.

For the 2016 update, no potentially relevant trials were identified by the searches.

Risk of bias in included studies

No trials were included.

Effects of interventions

The searches did not identify any randomised controlled trials eligible for inclusion in this systematic review, nor were we able to identify any ongoing trials.

Discussion

We have been unable to identify any clinical trials addressing the efficacy and safety of antibiotic treatment approaches for treating osteomyelitis in people with sickle cell disease (SCD). This is surprising in light of the number of people worldwide who suffer from this severe complication of SCD, and the strong link between infection and SCD.

There have been "three decades of innovation in the management of sickle cell disease" to improve the quality of treatment management for people with SCD (Bonds 2005); but no randomised controlled trials (RCTs) investigating the efficacy and safety of antibiotic treatment approaches for osteomyelitis in people with SCD have been conducted. This lack of trials shows a gap between clinical medicine and clinical investigation which has been emphasised recently (Ballas 2010).

If osteomyelitis has a high occurrence with a poor prognosis for people with SCD; the question would be "Why are there no randomised clinical trials for that clinical condition?".There is an ethical need to test the efficacy and safety of new and already approved medicines in the paediatric age, as data obtained in adults cannot be extrapolated to children. Is the natural history of osteomyelitis in people with SCD similar to the natural history of osteomyelitis in people without SCD? Given that individuals with SCD are immunosuppressed, is the clinical course of osteomyelitis in this population similar to the clinical course of the osteomyelitis in those without SCD? Also, is the clinical impact of antibiotic use in people with or without SCD suffering from osteomyelitis the same?

The paucity of data on antibiotic treatment for osteomyelitis in people with SCD should stimulate the development of well‐planned RCTs in an attempt to evaluate the widespread empirical practice in treating osteomyelitis in people with SCD. However, several efforts have been made to improve the management quality of care in people with SCD (Ballas 2010; DeBaun 2010).

Authors' conclusions

No RCTs of antibiotics in people with SCD suffering from osteomyelitis were found for inclusion in this review. Therefore, it was not possible to determine the efficacy and safety of the antibiotic treatment approaches (used either alone or in combination) for people with SCD suffering from osteomyelitis.

This systematic review has identified the need for well‐designed, adequately‐powered randomised controlled trials to assess the benefits and harms of antibiotic treatment approaches (used either alone or in combination) in people with SCD suffering from osteomyelitis. The following questions should be addressed using RCTs.

What is the clinical effectiveness of antibiotic use per oral versus intravenous route?

What regimen is most effective: single or combined antibiotic therapy?

When can patients affected by osteomyelitis be discharged?

When can intravenous antibiotic regimens be switched to oral administration?

The RCTs should consider the following clinical outcomes: time to resolution of signs and symptoms of active infection; residual disability, function and movement of affected area; and quality of life.

Trials should be structured and reported according to the 'Consort Statement' for improving the quality of reporting of efficacy and get better reports of harms in clinical research (Moher 2010; Schulz 2010).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Iberoamerican Cochrane Center, Barcelona, Spain. We would like to show our gratitude to peer reviewers for improving the quality of this review.

We also thank to Miss Tracey Remmington, Managing Editor of the Cochrane Cystic Fibrosis and Genetic Disorders Group.

Appendices

Appendix 1. LILACS search strategy (20 October 2016).

((Pt ENSAYO CONTROLADO ALEATORIO OR Pt ENSAYO CLINICO CONTROLADO OR Mh ENSAYOS CONTROLADOS ALEATORIOS OR Mh DISTRIBUCIÓN ALEATORIA OR Mh METODO DOBLE CIEGO OR Mh METODO SIMPLECIEGO OR Pt ESTUDIO MULTICÉNTRICO) or ((tw ensaio or tw ensayo or tw trial) and (tw azar or tw acaso or tw placebo or tw control$ or tw aleat$ or tw random$ or (tw duplo and tw cego) or (tw doble and tw ciego) or (tw double and tw blind)) and tw clinic$)) AND NOT ((Ct ANIMALES OR Mh ANIMALES OR Ct CONEJOS OR Ct RATÓN OR MH Ratas OR MH Primates OR MH Perros OR MH Conejos OR MH Porcinos) AND NOT (Ct HUMANO AND Ct ANIMALES)) [Palavras] and osteomyelitis [Palavras] and sickle [Palavras].

Result: 8 references

Appendix 2. African Index Medicus (20 October 2016).

1. sickle or anemia falciforme anemia de celulas falciformes or drepanocitosis or "SICKLE" or "SICKLE CELL HEMOGLOBIN C DISEASE" or "SICKLE CELL HEMOGLOBIN C DISEASE/" or "SICKLE CELL HEMOGLOBIN C DISEASE/BL" or "SICKLE CELL HEMOGLOBIN C DISEASE/CO" or "SICKLE CELL HEMOGLOBIN C DISEASE/DI" or "SICKLE CELL HEMOGLOBIN C DISEASE/DT" or "SICKLE CELL HEMOGLOBIN C DISEASE/EP" or "SICKLE CELL HEMOGLOBIN C DISEASE/ET" or "SICKLE CELL HEMOGLOBIN C DISEASE/GE" or "SICKLE CELL HEMOGLOBIN C DISEASE/MI" or "SICKLE CELL HEMOGLOBIN C DISEASE/PA" or "SICKLE CELL HEMOGLOBIN C DISEASE/PC" or "SICKLE CELL HEMOGLOBIN C DISEASE/PP" or "SICKLE CELL HEMOGLOBIN C DISEASE/TH" or "SICKLE CELL HEMOGLOBIN C DISEASE/UR" or "SICKLECELL" or "ANEMIA, SICKLE CELL" or "ANEMIA, SICKLE CELL/" or "ANEMIA, SICKLE CELL/AN" or "ANEMIA, SICKLE CELL/BL" or "ANEMIA, SICKLE CELL/CL" or "ANEMIA, SICKLE CELL/CN" or "ANEMIA, SICKLE CELL/CO" or "ANEMIA, SICKLE CELL/DI" or "ANEMIA, SICKLE CELL/DT" or "ANEMIA, SICKLE CELL/EH" or "ANEMIA, SICKLE CELL/EN" or "ANE" [Key Word]

2. osteomyelitis [Key Word] Result: 1 references.

Appendix 3. ISI Web of Knowledge (2008 to 3 November 2012).

TS=(sickle*) AND TS=osteomyelitis Timespan=2008‐2012. Results: 38 references.

Appendix 4. World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (20 October 2016).

sickle AND osteomyelitis Result: 0 references.

Appendix 5. ClinicalTrials.gov (20 October 2016).

sickle AND osteomyelitis Result: 0 references.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 9 November 2016 | New search has been performed | A search of the Cystic Fibrosis and Genetic Disorders Haemogobinopathies Trials Register did not identify any potentially relevant trials for inclusion in this review. |

| 9 November 2016 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Minor changes have been made throughout. The 'Plain language summary' has been re‐formatted. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2008 Review first published: Issue 2, 2009

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 24 January 2013 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 12 December 2012 | Review declared as stable | There are no trials included in the review to October 2012. We therefore do not plan to update this review until new trials are published, although we will search the Grouup's Haemoglobinopathies Trials Register on a two‐yearly cycle. |

| 19 October 2012 | New search has been performed | A search of the Cystic Fibrosis and Genetic Disorders Group's Haemoglobinopathies Trials Register did not identify any potentially eligible trials. |

| 19 October 2012 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | The review has been updated, with minor changes throughout. |

| 22 May 2012 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 11 December 2010 | New search has been performed | 1. This review is an update of the previous Cochrane systematic review (Martí‐Carvajal 2009) that contained no included, excluded or ongoing trials. 2. In the previous version we searched the databases to 14 November 2008. In this updated version we re‐ran the searches to 08 December 2010. 3. No potentially eligible trials were identified by the search of the Group's Haemoglobiniopathies Trials Register. 4. There were 36 potentially eligible trials identified by the search of LILACS, African Index Medicus and ISI Web of Knowledge. 5. No studies identified were eligible for inclusion in Included studies. Four studies have been listed as Excluded studies (Akakpo‐Numado 2008; Akakpo‐Numado 2009; Berger 2009; Hernigou 2010). 6. Change in authors: Marcela Cortés (co‐author on the previous version Martí‐Carvajal 2009) has left the review team. 7. We have included new subheadings in the Background, Methods and Discussion sections. 8. We have incorporated information on the structure of any future risk of bias (ROB) and summary of findings tables (SOF). |

| 11 November 2010 | Amended | Added information on search results. |

| 26 April 2010 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

Differences between protocol and review

We have inserted a statement at the end of the Assessment of risk of bias in included studies section on the 'Summary of findings tables'.

We have inserted a flowchart of the search results.

The contact details of Arturo Martí‐Carvajal (contact person) has been changed.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Akakpo‐Numado 2008 | A retrospective survey to determine the distribution of causative bacteria. |

| Akakpo‐Numado 2009 | A retrospective study of locations of osteomyelitis. |

| Berger 2009 | A prospective study for differentiating osteomyelitis from vaso‐occlusive crisis in children with SCD. |

| Hernigou 2010 | A case report. |

SCD: sickle cell disease

Contributions of authors

Arturo Martí‐Carvajal conceived and drafted the review with comments from Luís Agreda‐Pérez. Arturo Martí‐Carvajal acts as guarantor for the review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

Iberoamerican Cochrane Center, Spain.

-

National Institute for Health Research, UK.

This systematic review was supported by the National Institute for Health Research, via Cochrane Infrastructure funding to the Cochrane Cystic Fibrosis and Genetic Disorders Group.

Declarations of interest

Arturo Martí‐Carvajal: none known. Luis H Agreda‐Pérez: none known.

New search for studies and content updated (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies excluded from this review

- Akakpo‐Numado GK, Gnassingbe K, Boume MA, Songne B, Tekou H. Current bacterial causes of osteomyelitis in children with sickle cell disease [Bacteriologie des osteomyelites de l'enfant drepanocytaire au CHU de Tokoin (Togo): tentative d'evaluation et therapeutiques]. Sante 2008;18(2):67‐70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akakpo‐Numado GK, Gnassingbe K, Abalo A, Boume MA, Sakiye KA, Tekou H. Locations of osteomyelitis in children with sickle‐cell disease at Tokoin teaching hospital (Togo). Pediatric Surgery International 2009;25(8):723‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger E, Saunders N, Wang L, Friedman JN. Sickle cell disease in children: differentiating osteomyelitis from vaso‐occlusive crisis. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 2009;163(3):251‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernigou P, Daltro G, Flouzat‐Lachaniette CH, Roussignol X, Poignard A. Septic arthritis in adults with sickle cell disease often is associated with osteomyelitis or osteonecrosis. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 2010;468(6):1676‐81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

- Akinsheye I, Klings ES. Sickle cell anemia and vascular dysfunction: the nitric oxide connection. Journal of Cellular Physiology 2010;224(3):620‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al‐Ola K, Mahdi N, Al‐Subaie AM, Ali ME, Al‐Absi IK, Almawi WY. Evidence for HLA class II susceptible and protective haplotypes for osteomyelitis in paediatric patients with sickle cell anaemia. Tissue Antigens 2008;71(5):453‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexy T, Sangkatumvong S, Connes P, Pais E, Tripette J, Barthelemy JC, et al. Sickle cell disease: selected aspects of pathophysiology. Clinical Hemorheology and Microcirculation 2010;44(3):155‐66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida A, Roberts I. Bone involvement in sickle cell disease. British Journal of Haematology 2005;129(4):482‐90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslan M, Freeman BA. Redox‐dependent impairment of vascular function in sickle cell disease. Free Radical Biology & Medicine 2007;43(11):1469‐83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahebeck J, Atangana R, Techa A, Monny‐Lobe M, Sosso M, Hoffmeyer P. Relative rates and features of musculoskeletal complications in adult sicklers. Acta Orthopaedica Belgica 2004;70(2):107‐11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballas SK, Lieff S, Benjamin LJ, Dampier CD, Heeney MM, Hoppe C, et al. Definitions of the phenotypic manifestations of sickle cell disease. American Journal of Hematology 2010;85(1):6‐13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begue P, Castello‐Herbreteau B. Severe infections in children with sickle cell disease: clinical aspects and prevention. Archives de Pédiatrie 2001;8(Suppl 4):732‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennet GC, Bennet SJ. Infection of bone and joint. Surgery 2006;24(6):211‐4. [Google Scholar]

- Booth C, Inusa B, Obaro SK. Infection in sickle cell disease: a review. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2010;14(1):2‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan G, Vichinsky E, Krishnamurti L, Shenoy S. Severe sickle cell disease‐‐pathophysiology and therapy. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation 2010;16(Suppl 1):64‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett MW, Bass JW, Cook BA. Etiology of osteomyelitis complicating sickle cell disease. Pediatrics 1998;101(2):296‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carek PJ, Dickerson LM, Sack JL. Diagnosis and management of osteomyelitis. American Family Physician 2001;63(12):2413‐20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciampolini J, Harding KG. Pathophysiology of chronic bacterial osteomyelitis. Why do antibiotics fail so often?. Postgraduate Medical Journal 2000;76(898):479‐83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darghouth D, Koehl B, Madalinski G, Heilier JF, Bovee P, Xu Y, et al. Pathophysiology of sickle cell disease is mirrored by the red blood cell metabolome. Blood 2011;117(6):e57‐66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBaun MR. Finally, a consensus statement on sickle cell disease manifestations: a critical step in improving the medical care and research agenda for individuals with sickle cell disease. American Journal of Hematology2010; Vol. 85, issue 1:1‐3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ejindu VC, Hine AL, Mashayekhi M, Shorvon PJ, Misra RR. Musculoskeletal manifestations of sickle cell disease. Radiographics 2007;27(4):1005‐21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epps CH Jr, Bryant DD 3rd, Coles MJ, Castro O. Osteomyelitis in patients who have sickle‐cell disease. Diagnosis and management. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 1991;73(9):1281‐94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brozek J, Oxman A, Schünemann H. GRADEpro. Version Version 3.2 for Windows. Grade Working Group, 2008.

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Vist GE, Falck‐Ytter Y, Schünemann HJ. What is "quality of evidence"and why is it important to clinicians. BMJ 2008;336(7651):995‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagar W, Vichinsky E. Advances in clinical research in sickle cell disease. British Journal of Haematology 2008;141(3):346‐56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebbel RP, Osarogiagbon R, Kaul D. The endothelial biology of sickle cell disease: inflammation and a chronic vasculopathy. Microcirculation 2004;11(2):129‐51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta‐analyses. BMJ 2003;327(7414):557‐60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 20011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

- Huber AM, Lam PY, Duffy CM, Yeung RS, Ditchfield M, Laxer D, et al. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis: clinical outcomes after more than five years of follow‐up. Journal of Pediatrics 2002;141(2):198‐203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibingira CB. Chronic osteomyelitis in a Ugandan rural setting. East African Medical Journal 2003;80(5):242‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato GJ, Gladwin MT, Steinberg MH. Deconstructing sickle cell disease: reappraisal of the role of hemolysis in the development of clinical subphenotypes. Blood Reviews 2007;21(1):37‐47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato GJ, Hebbel RP, Steinberg MH, Gladwin MT. Vasculopathy in sickle cell disease: Biology, pathophysiology, genetics, translational medicine, and new research directions. American Journal of Hematology2009; Vol. 84, issue 9:618‐25. [PUBMED: 19610078] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kim SK, Miller JH. Natural history and distribution of bone and bone marrow infarction in sickle hemoglobinopathies. Journal of Nuclear Medicine 2002;43(7):896‐900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazzarini L, Lipsky BA, Mader JT. Antibiotic treatment of osteomyelitis: what have we learned from 30 years of clinical trials?. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2005;9(3):127‐38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saux N, Howard A, Barrowman NJ, Gaboury I, Sampson M, Moher D. Shorter courses of parenteral antibiotic therapy do not appear to influence response rates for children with acute hematogenous osteomyelitis: a systematic review. BMC Infectious Diseases 2002;14(2):16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lew DP, Waldvogel FA. Osteomyelitis. Lancet 2004;364(9431):369‐79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack AK, Kato GJ. Sickle cell disease and nitric oxide: a paradigm shift?. International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology 2006;38(8):1237‐43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansingh A, Ware M. Acute haematogenous anaerobic osteomyelitis in sickle cell disease. A case report and review of the literature. West Indian Medical Journal 2003;52(1):53‐5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meddeb N, Gandoura N, Gandoura M, Sellami S. Osteoarticular manifestations of sickle cell disease. La Tunisie Médicale 2003;81(7):441‐7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, Montori V, Gotzsche PC, Devereaux PJ, et al. CONSORT 2010 Explanation and Elaboration: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2010;63(8):1‐37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mousa SA, Qari MH. Diagnosis and management of sickle cell disorders. Methods in Molecular Biology (Clifton, N.J.) 2010;663:291‐307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neonato MG, Guilloud‐Bataille M, Beauvais P, Begue P, Belloy M, Benkerrou M, et al. Acute clinical events in 299 homozygous sickle cell patients living in France. French Study Group on Sickle Cell Disease. European Journal of Haematology 2000;65(3):155‐64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nwadiaro HC, Ugwu BT, Legbo JN. Chronic osteomyelitis in patients with sickle cell disease. East African Medical Journal 2000;77(1):23‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onche II, Obiano SK. Chronic osteomyelitis of long bones: reasons for delay in presentation. Nigerian Journal of Medicine 2004;13(4):355‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orkin SH, Higgs DR. Medicine. Sickle cell disease at 100 years. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2010;329(5989):291‐2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paluska SA. Osteomyelitis. Clinics in Family Practice 2004;6(1):127‐56. [Google Scholar]

- Pauling L, Itano HA, Singer SJ, Wells IC. Sickle cell anemia, a molecular disease. Science 1949;110:543‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakar H, Haywood C Jr, Molokie R. Sickle cell disease in the United States: looking back and forward at 100 years of progress in management and survival. American Journal of Hematology 2010;85(5):346‐53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees DC, Williams TN, Gladwin MT. Sickle‐cell disease. Lancet 2010;Dec 3:Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadat‐Ali M. The status of acute osteomyelitis in sickle cell disease. A 15‐year review. International Surgery 1998;83(1):84‐7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sathappan SS, Ginat D, Cesare PE. Multidisciplinary management of orthopedic patients with sickle cell disease. Orthopedics 2006;29(12):1094‐101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunthararajah Y, Vichinsky EP, Embury SH. Sickle cell disease. Hoffman: Hematology: Basic Principles and Practice. Churchill Livingstone, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 Statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2010;63(8):834‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serjeant GR. Sickle Cell Disease. New York: Oxford Medical Publications, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Serjeant GR. The emerging understanding of sickle cell disease. British Journal of Haematology 2001;112(1):3‐18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serjeant GR. One hundred years of sickle cell disease. British journal of haematology 2010;151(5):425‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sia IG, Berbari EF. Infection and musculoskeletal conditions: Osteomyelitis. Baillière's Best Practice & Research. Clinical Rheumatology 2006;20(6):1065‐81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaggs DL, Kim SK, Greene NW, Harris D, Miller JH. Differentiation between bone infarction and acute osteomyelitis in children with sickle‐cell disease with use of sequential radionuclide bone‐marrow and bone scans. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American volume 2001;83‐A(12):1810‐3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg MH. Pathophysiologically based drug treatment of sickle cell disease. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 2006;27(4):204‐10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart MJ, Nagel RL. Sickle‐cell disease. Lancet 2004;364(9442):1343‐60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarer V, Etienne‐Julan M, Diara JP, Belloy MS, Mukizi‐Mukaza M, Elion J, et al. Sickle cell anemia in Guadeloupean children: pattern and prevalence of acute clinical events. European Journal of Haematology 2006;76(3):193‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tekou H, Foly A, Akue B. Current profile of hematogenous osteomyelitis in children at the Tokoin University Hospital Center in Lome, Togo. Report of 145 cases. Médecine Tropicale: Revue du Corps de Santé Colonial 2000;60(4):365‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thanni LO. Bacterial osteomyelitis in major sickling haemoglobinopathies: geographic difference in pathogen prevalence. African Health Sciences 2006;6(4):236‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weatherall D, Akinyanju O, Fucharoen S, Olivieri N, Musgrove P. Inherited Disorders of Hemoglobin. Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. 2nd Edition. Washington DC: The World Bank and Oxford University Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- William BM, Corazza GR. Hyposplenism: a comprehensive review. Part I: basic concepts and causes. Hematology 2007;12(2):1‐13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witjes MJ, Berghuis‐Bergsma N, Phan TT. Positron emission tomography scans for distinguishing between osteomyelitis and infarction in sickle cell disease. British Journal of Haematology 2006;133(2):212‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood KC, Hsu LL, Gladwin MT. Sickle cell disease vasculopathy: a state of nitric oxide resistance. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2008;44(8):1506‐28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to other published versions of this review

- Martí‐Carvajal AJ, Agreda‐Pérez LH. Antibiotics for treating osteomyelitis in people with sickle cell disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007175.pub2] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martí‐Carvajal AJ, Agreda‐Pérez LH. Antibiotics for treating osteomyelitis in people with sickle cell disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 12. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007175.pub3] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]