Abstract

Current understanding of human motor unit (MU) control and aging is mostly derived from hand and limb muscles that have spinal motor neuron innervations. The aim here was to characterize and test whether a muscle with a shared innervation supply from brainstem and spinal MU populations would demonstrate similar age-related adaptations as those reported for other muscles. In humans, the superior trapezius (ST) muscle acts to elevate and stabilize the scapula and has primary efferent supply from the spinal accessory nerve (cranial nerve XI) located in the brainstem. We compared electrophysiological properties obtained from intramuscular and surface recordings between 10 young (22–33 yr) and 10 old (77–88 yr) men at a range of voluntary isometric contraction intensities (from 15 to 100% of maximal efforts). The old group was 41% weaker with 43% lower MU discharge frequencies compared with the young (47.2 ± 9.6 Hz young and 26.7 ± 5.8 Hz old, P < 0.05) during maximal efforts. There was no difference in MU number estimation between age groups (228 ± 105 young and 209 ± 89 old, P = 0.33). Furthermore, there were no differences in needle detected near fiber (NF) stability parameters of jitter or jiggle. The old group had lower amplitude and smaller area of the stimulated compound muscle action potential and smaller NF MU potential area with higher NF counts. Thus, despite age-related ST weakness and lower MU discharge rates, there was minimal evidence of MU loss or compensatory reinnervation.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY The human superior trapezius (ST) has shared spinal and brainstem motor neuron innervation providing a unique model to explore the impact of aging on motor unit (MU) properties. Although the ST showed higher MU discharge rates compared with most spinally innervated muscles, voluntary strength and mean MU rates were lower in old compared with young at all contraction intensities. There was no age-related difference in MU number estimates with minimal electrophysiological evidence of collateral reinnervation.

Keywords: aging, firing rate, neck, upper trapezius, voluntary force

INTRODUCTION

In humans, current understanding of motor unit (MU) properties in aging is primarily derived from the investigation of muscles innervated by spinal motor neurons (Doherty and Brown 1993; Hepple and Rice 2016). From in situ counts of human motor neurons located in the spinal cord, there is significant loss after the 7th decade of life (Tomlinson and Irving 1977; Terao et al. 1996). Electrophysiological assessments of human hand and limb muscles in vivo have supported these findings and demonstrated age-related MU loss and remodeling through the process of collateral reinnervation (Allen et al. 2013; Brown et al. 1988; Campbell et al. 1973; Chan et al. 2001; Dalton et al. 2008; Doherty and Brown 1993; Gilmore et al. 2017, 2018; Hourigan et al. 2015; Ives and Doherty 2014a; McKinnon et al. 2015; McNeil et al. 2005; Saboisky et al. 2014). The only investigation to our knowledge that has explored age-related comparisons from nonspinally derived MUs in humans is from the genioglossus muscle recorded under quiet breathing, and the results were similar to studies of MU remodeling from human hand and limb muscles (Saboisky et al. 2014). Findings leading to the concept of MU loss and remodeling in vivo are derived from the age-related reduction of the maximum compound muscle action potential (CMAP) and measures of MU potential (MUP) size and stability. When MU loss from aging or axonal injury occurs, subsequent MU remodeling is associated with muscle fiber atrophy and fiber type grouping (Edström and Larsson 1987; Hashizume et al. 1988; Jakobsson et al. 1990; Lexell et al. 1988; Lexell and Downham 1991), increased MUP size (Doherty and Brown 1993; Krarup et al. 2016; Ling et al. 2009; Stålberg and Fawcett 1982), and motor end plate instability (Wokke et al. 1990). These features are supported in nonhuman, in vitro preparations of aged spinal MU samples that demonstrate motor neuron loss (Hashizume et al. 1988; Jacob 1998; Wright and Spink 1959), muscle fiber atrophy (Lopez et al. 2000), motor end plate instability (Kulakowski et al. 2011; Prakash and Sieck 1998; Rosenheimer and Smith 1985), and the loss of synaptic vesicles with decreases in nerve terminal area (Banker et al. 1983).

To investigate a MU population during voluntary contractions in humans, MUP characteristics are recorded from the muscle fibers of the MU, which fundamentally represent motor neuron output. Age-related comparisons using this technique have been studied in relatively few major hand and limb muscles (Connelly et al. 1999; Dalton et al. 2009, 2010; Erim et al. 1999; Kirk et al. 2016, 2018; Patten et al. 2001; Roos et al. 1999). Unique to these investigations, MU discharge rates recorded during isometric contractions at moderate to maximal voluntary intensities are generally lower in older compared with younger adults, and the frequency range and differences between age groups is variable among muscles explored. However, these age-related comparisons of MU discharge rates related to voluntary contraction intensity have mainly been made for muscles innervated by spinal MU populations, whereas the effects of aging on discharge rates with brainstem motor neuron innervation are unknown. Investigating muscles with brainstem innervation may provide novel insights due to the important differences in brainstem development, structure, and function compared with spinal motor neurons (Greer and Funk 2005). Therefore, it may not be sensible to extrapolate age-related MU changes found in hand and limb muscles to other muscles innervated by brainstem motor neurons (McComas 1998).

Skeletal muscle can be innervated by motor neurons from the spinal cord, brainstem, or both. Unlike the genioglossus, and hand and limb muscles, the superior trapezius (ST) is an axial muscle that has mixed innervation from spinal and brainstem motor neurons, and the MU can be assessed in vivo with minimally invasive techniques (Ives and Doherty 2012. 2014a, 2014b). The ST muscle is located superior and posterior on the axial skeleton and acts to elevate the scapulae. In humans, the ST muscle has primary efferent supply from the spinal accessory nerve with axons originating from motor neurons located in the accessory nucleus of the brainstem (Fahrer et al. 1974; Kierner et al. 2001) with afferent innervation through the cervical plexus (Alexander and Harrison 2002; Weisberger 1987). In some individuals, there is also evidence of motor and sensory contributions from C2-C5 regions of the spinal cord (Pu et al. 2008; Weisberger 1987). This unique innervation pattern enables the study of a brainstem MU population from the cranial accessory nucleus (cranial nerve XI) during voluntary contractions. Therefore, the purpose of this investigation was to compare in vivo electrophysiological parameters of a representative MU sample between young and old age groups in the ST muscle. Building on prior reports from human skeletal muscles that have exclusive spinal or brainstem motor neuron supply, we hypothesized that the ST muscle will undergo similar age-related adaptations, and in the old men compared with the young, will have lower MU discharge frequencies during voluntary contractions and show evidence of MU loss and collateral reinnervation.

METHODS

Participants

Twenty male participants (10 young and 10 old) volunteered for this investigation. Young participants (22–33 yr) were normally active University students. The older participants (77–88 yr) were independently living and participated three times per week in an organized fitness and light exercise program. Exclusion criteria included known: neurological or metabolic disease and any impairment to the upper limb, shoulder, head, and neck. This investigation was approved by the local institutional research ethics board for human experimentation and conformed to the latest revision of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent and were instructed to refrain from intense exercise and nonhabitual caffeine consumption within 48 h before testing. Participants visited the neuromuscular laboratory for two to four testing sessions, each separated by 2–7 days.

Experimental Protocol

Bilateral voluntary isometric contractions were performed on a modified dynamometer (neck and shoulder, Nautilus Sports Medical Industries) at submaximal [15, 25, and 50% of maximal voluntary contraction (MVC)] and MVC intensities (Fig. 1). Bilateral voluntary contractions were used to control for unilateral confounds of force and voluntary activation (Taylor et al. 2009). Seat height was controlled with the use of padded cushions to maintain the knees and hips at ~90°. Padded supports firmly secured the elbow joint at 90° with forearms supinated, wrists extended, and hands open. In this position, any elbow flexor moment was not directed through the load cell that was mounted distally on the lever arm that only registered force in the vertical direction (Fig. 1). Thus, to produce force during voluntary contractions, the participant retracted and then raised (performed a shrug) both shoulders vertically with the forearms acting as strut to engage the lever arm vertically. This setup also minimized any contribution from lower limb or torso movements. Voltage from the load cell (model SSM-AJ-SK; Durham Instruments, Ontario, Canada) was calibrated in Newtons, digitized with an analog-to-digital converter (Power1401; Cambridge Electronics Design, Cambridge, UK), and sampled at 1 kHz. Each session included a familiarization and three to five attempts to produce a maximal force output during isometric MVC with 3–5 min of rest between contractions to mitigate fatigue. Maximal force output, which was used to normalize all contraction intensities, was achieved when the force of successive attempts did not increase. During each voluntary contraction, real-time visual feedback of voluntary strength was provided to the participant on a 24-in. monitor positioned ~1 m away at eye level, and strong verbal encouragement was given to each participant during all voluntary contractions.

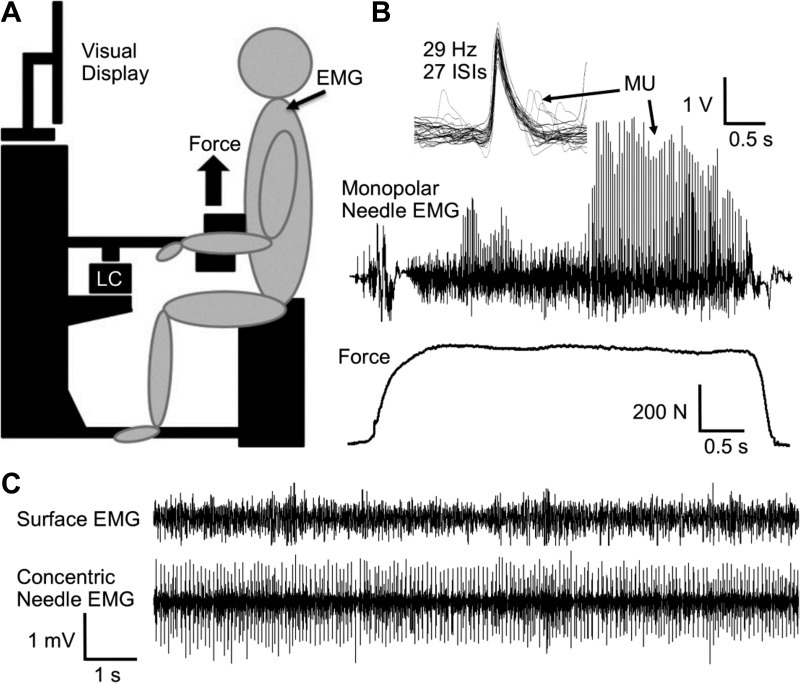

Fig. 1.

Representations of the experimental set-up and recorded electromyography (EMG). A: schematic of the dynamometer. B: motor unit (MU) potential overlay of the monopolar needle EMG and force tracing during an isometric maximal voluntary contraction (MVC) of an old participant (82 yr). C: surface EMG and concentric needle EMG during 15% of MVC. LC, load cell. Scale bars are associated with the EMG and force tracings.

Electrophysiology

Bilateral superior trapezius activation.

Surface electromyography (EMG) from the left and right ST muscles was used as a control measure to assess differences in global MU activity between the two sides. The skin was cleansed with 70% ethanol, and surface electrodes (H59P-127 Electrodes; Kendall) were positioned in line with the muscle in a bipolar configuration with a 1-cm interelectrode distance located half-way between the C7 spinous process and superior border of the scapulae (Taylor et al. 2009), and a ground electrode was placed on the C7 spinous process. Surface EMG of the left and right ST was recorded, preamplified 1,000 times, filtered between 0.01 and 1 kHz, and sampled at 2 kHz.

MU discharge frequencies.

Intramuscular EMG was recorded for each participant following existing protocols from other muscles (Bellemare et al. 1983; Dalton et al. 2010; Kirk et al. 2016; Kirk and Rice 2017). The monopolar electrodes used were insulated tungsten wire needles (123-µm shaft diameter and 45-mm length; Frederick Haer). The skin was cleansed with 70% ethanol, and two intramuscular electrodes were inserted independently into the same portion of the ST muscle half-way between the acromion and C7 spinous process, and each was manipulated by separate investigators. The electrodes were manipulated at a superficial depth and care was taken to not advance the needle through the muscle to avoid recording from the levator scapulae or middle trapezius. A surface reference electrode was placed on the acromion process, and a ground electrode was placed over the surface of the deltoid muscle. The EMG was preamplified 100–200 times, filtered between 0.01 and 10 kHz, digitized, and sampled at 20 kHz, with independent auditory and visual feedback of each channel provided to each operator.

Voluntary isometric contractions were held for 5–10 s at submaximal intensities (25 and 50% of MVC) and ~5 s at MVC. Between each randomized contraction, 3–5 min of rest was provided to minimize the effects of fatigue. To increase the probability of discrete MU sampling, the intramuscular electrodes were advanced 1–3 mm per contraction, and over a series of contraction intensities the intramuscular electrodes were repositioned and reinserted into different portions of the ST muscle maintaining the superficial depth Several isometric voluntary contractions (8–10) were made at each intensity. To further control for fatigue, if the MVC force was reduced by ≥5% from the baseline MVC, the session for that day ended. Therefore to acquire many MUP trains (MUPTs) per person without the influence of fatigue, some participants returned to the laboratory to repeat these intramuscular recording procedures on a different day.

Decomposition-Based Quantitative Electromyography

On a separate day, a maximum compound muscle action potential (CMAP) was evoked by stimulation (100-µs square wave pulse at 400 V, model DS7AH; Digitimer, Welwyn Garden City, Hetfordshire, UK) of the spinal accessory nerve just posterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle with a handheld bipolar bar electrode. The active surface EMG electrode in a monopolar configuration (see below) was moved in small increments to a position in which the negative peak amplitude of the CMAP was maximized and the rise time minimized. Once the position was found, the surface EMG electrodes were taped to the skin to control for electrode movement. The stimulus current was incrementally increased to elicit the maximum negative peak amplitude of the CMAP, and then the current was increased to ×1.15 to elicit a supramaximal CMAP, with the range of 50–160 mA in the young and 80–160 mA in the old.

To obtain quantitative measures of MU number and size, decomposition-based quantitative electromyography (DQEMG) of the ST muscle was used for each participant (Ives and Doherty 2012, 2014a, 2014b). Briefly, self-adhering silver Mactrode electrodes (GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI) were used to detect surface EMG and a 25 mm × 30-gauge TECA elite disposable concentric needle electrode (CareFusion, Middleton, WI) was used to detect intramuscular EMG. Surface EMG was preamplified 1,000 times, filtered between 0.01 and 5 kHz and sampled at 20 kHz. Intramuscular EMG was preamplified 1,000 times, filtered between 0.01 and 10 kHz, and sampled at 20 kHz. The skin was cleansed with 70% ethanol; surface electrodes were cut in strips (1.5 × 3.5 cm), with the active electrode positioned transversely over the belly of the ST muscle, midway between the acromion process and C7 spinous process; and the reference electrode was placed over the acromion process. A full-sized surface electrode (2.5 × 3.5 cm) was placed over the deltoid muscle as a ground. The concentric needle electrode was inserted at an acute 30–45° angle into the ST ~1–2 mm in distance from the active surface electrode, and always at a minimal muscle depth just below the superficial fascia of the ST (Ives and Doherty 2014b). Participants were instructed to perform low-intensity voluntary contractions (<5% MVC) while the operator repositioned the needle within the ST muscle to an active area. The needle was maintained and not manipulated once in an optimal position within the muscle while the participant was instructed to increase isometric contraction intensity to 15% MVC and sustained this level of voluntary contraction for 30–45 s duration. Participants performed 8–12 contractions at this intensity with ~1–3 min rest between each. These submaximal contractions were repeated until a minimum of 20 MUPTs were collected. The needle was repositioned after each contraction and reinserted after three concurrent contractions to sample from slightly different portions of the muscle.

Data Analyses

The software applications Spike 2 (version 7.02 and 7.20; Cambridge Electronics Design) and DQEMG (version 4.0; Waterloo University, Waterloo, Canada) were used for signal acquisition and analysis.

Bilateral superior trapezius activation.

For surface EMG, the root-mean-square (RMS) EMG amplitude was calculated with a time constant of 0.2 s. The EMG RMS at 25 and 50% of MVC were normalized by the EMG RMS at MVC for each participant’s left and right ST muscle, respectively.

MU discharge frequencies.

For MU discharge frequencies, MUPTs were accepted for measurement during the steady state force produced during the isometric contractions (Fig. 1B). A template shape algorithm was applied facilitating the process to define parameters of each MUPT as described by existing protocols (Connelly et al. 1999; Kirk et al. 2016; Rich et al. 1998). This involved visual inspection by an experienced operator to confirm MUP sorting and shape overlay of each MUPT. For inclusion, a MUPT was required to have consistent MUP waveform shapes and amplitudes, a minimum of five contiguous MUPs, and an interspike interval duration coefficient of variation <0.3. Doublets (>100 Hz) occurred rarely and were excluded.

DQEMG

For DQEMG analysis, the EMG was recorded using Spike 2 (version 7.02). For inclusion, the EMG signal must have occurred during a steady state of the isometric force tracing at 15% MVC; contain no observable needle movement artifact; and have observable MUPT within the intramuscular EMG channel concurrent with surface EMG activity (Fig. 1C). The DQEMG method, associated algorithms, and inclusion criteria for MUPTs have been described previously (Boe et al. 2004; Doherty and Stashuk 2003; Stashuk 1999a, 1999b). For the investigation of electrophysiological measures related to collateral reinnervation and neuromuscular transmission variability, characteristics of the near fiber (NF) MUP were made. These measures are comprised of contributions from fibers close to the recording surface of the intramuscular electrode identified by high-pass filtering and required validation by an experienced investigator (Gilmore et al. 2017; Hourigan et al. 2015; Stashuk 1999b).

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using R (version 3.5.2). All data are presented as means ± SD unless otherwise stated. To compare the effects of contraction intensity, age group, and ST muscle side on relative surface EMG RMS, an ANOVA was used. MU discharge frequencies were grouped into three bins based on contraction intensity: a 25% bin contained 12.5–37.5% of MVC, a 50% bin contained 37.5–62.5% of MVC, and a 100% bin contained 87.5–100% of MVC. With the use of these bin parameters, mean MU frequencies were then computed for each participant. To assess the effect of contraction intensity and age group on MU frequencies, an ANOVA was used. If a significant group difference was detected Tukey honestly significant difference post hoc test was used to determine differences within the interaction. To assess the distribution of sampled MU discharge frequencies, kernel density plots were generated for each contraction intensity, muscle, and age group. For differences in anthropometric measurements between age groups, unpaired one-tailed t-tests were used. For DQEMG, descriptive statistics from quantitative MU analysis were automatically calculated based on all validated and accepted MUPTs, MUPs, and surface MUP (SMUPs). To assess differences in DQEMG parameters between age groups, an unpaired one-tailed t-test was used for MUNE and unpaired two-tail t-tests were used for all other measures. A Pearson correlation was used to compare DQEMG parameters. An α ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant, with significant group differences corrected for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg method.

RESULTS

Voluntary Strength, Anthropometric Parameters, and Bilateral Surface EMG of the ST Muscles

Bilateral voluntary strength and anthropometric values for the young and old groups are presented in Table 1. With a mean age difference of 55 yr, the old group had 41% lower mean force at MVC compared with the young (Table 1). Because only the left ST muscle was assessed using intramuscular EMG, but the force recording apparatus required a bilateral action, the relative submaximal surface EMG activity (normalized to the MVC EMG) between the left and right ST muscles was compared with control for unilateral differences (Table 1). For the interaction between EMG RMS and contraction intensity, there was a significant effect (F1,19 = 105.4, P < 0.001) such that higher targeted MVC intensities had greater surface EMG RMS (Table 1). However, when comparing the surface EMG RMS between the right and left ST muscle, there was no significant effect of age group or contraction intensity (F1,19 = 0.169, P = NS).

Table 1.

Voluntary strength, anthropometric parameters, and bilateral surface EMG of the ST muscles

| Parameter | Young | Old |

|---|---|---|

| N | 10 | 10 |

| Age, yr | 26 ± 4 | 81 ± 4* |

| Height, cm | 183 ± 4 | 176 ± 6* |

| Mass, kg | 85 ± 7 | 81 ± 9 |

| MVC, N | 690.3 ± 122.3 | 409.3 ± 140.5* |

| Surface EMG at 25% MVC | ||

| Left side, %RMS | 28.9 ± 7.1 | 30.5 ± 6.9 |

| Right side, %RMS | 33.1 ± 10.4 | 38.6 ± 12.5 |

| Surface EMG at 50% MVC | ||

| Left side, %RMS | 55.5 ± 6.1 | 54.4 ± 9.3 |

| Right side, %RMS | 58.0 ± 10.5 | 57.4 ± 3.9 |

Values are presented as the means ± SD. ST, superior trapezius; MVC, maximal voluntary isometric contraction; RMS, root mean square.

P < 0.05.

MU Discharges of the ST Muscle Between Age Groups

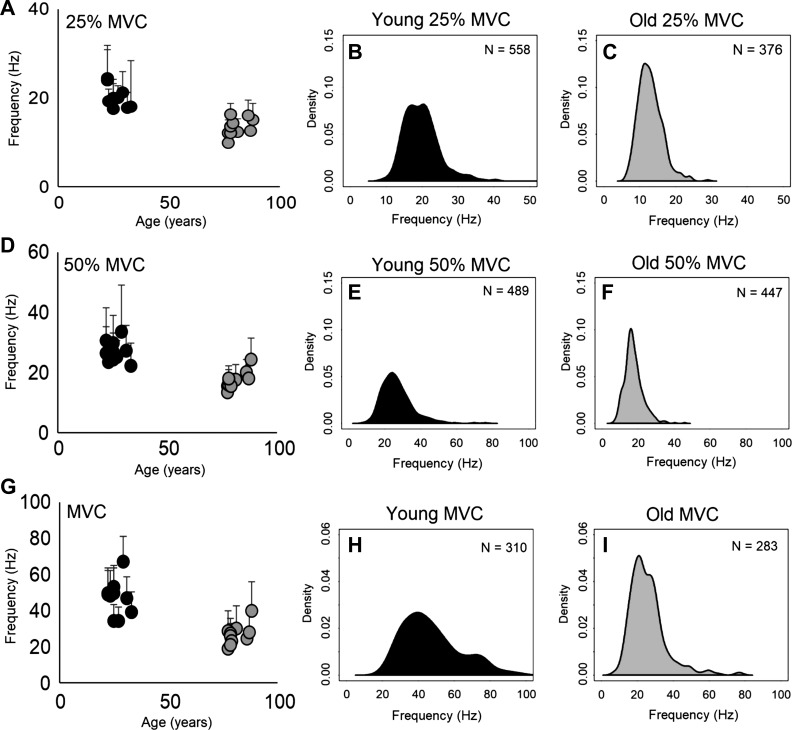

From recording intramuscular EMG using monopolar electrodes, a total of 2,463 MUPTs were measured from the ST muscle, with 1,357 from the young and 1,106 from the old group. MU discharge frequencies at submaximal (25 and 50% of MVC) and MVC are shown in Table 2. For mean MU discharge frequencies binned by target contraction intensity, there was a main effect of age and contraction intensity (F2, 19 = 10.1, P < 0.001), and at all contraction intensities the old had lower mean frequencies that were statistically significantly different from the young (Table 2). Mean MU discharge frequencies for each participant are presented by targeted contraction intensity stratified by age (Fig. 2). For the distribution of MU discharge frequencies dependent on age and contraction intensity, the old had a lower frequency distribution as compared with the young for each intensity (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

MU discharge parameters of the ST muscle

| Parameter | Young | Old | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Targeted contraction, %MVC | 25 | 50 | 100 | 25 | 50 | 100 |

| Voluntary contraction, %MVC | 24 ± 2 | 49 ± 3 | 94 ± 2 | 26 ± 3 | 49 ± 4 | 94 ± 2 |

| MU discharges, Hz | 20.2 ± 2.4 | 27.0 ± 3.5 | 47.2 ± 9.6 | 13.4 ± 2.0* | 17.6 ± 3.0* | 26.7 ± 5.8* |

| Total number MUPTs | 558 | 489 | 310 | 376 | 447 | 283 |

| MUPTs/participant | 56 ± 12 | 49 ± 17 | 31 ± 14 | 38 ± 11 | 45 ± 11 | 28 ± 10 |

| Number of ISI | 13 ± 4 | 11 ± 3 | 9 ± 2 | 13 ± 4 | 12 ± 3 | 9 ± 2 |

| Coefficient of variation | 12.1 ± 1.4 | 13.2 ± 0.7 | 14.6 ± 1.4 | 12.0 ± 1.6 | 13.0 ± 1.5 | 14.5 ± 1.2 |

Values are presented as the ensemble means ± SD; n = 20. Motor unit (MU) potential trains (MUPTs) were recorded during left superior trapezius (ST) submaximal [25 and 50% maximal voluntary isometric contraction (MVC)] and MVC intensities. ISI, interspike interval.

P < 0.001, between age groups (young vs. old) comparing the same targeted MVC.

Fig. 2.

Motor unit (MU) discharge frequencies of the superior trapezius (ST) muscle. A, D, and G: scatterplots are of mean MU frequencies and SD (error bars) for each participant dependent on age for 25% of maximal voluntary contraction (MVC; A), 50% of MVC (D), and MVC intensities (G) (n = 20). B, C, E, F, H, and I: kernel density plots representing the distribution of MU discharge frequencies dependent on age group and contraction intensity, with the smoothing bandwidth being scaled to the SD of the smoothing kernel.

DQEMG

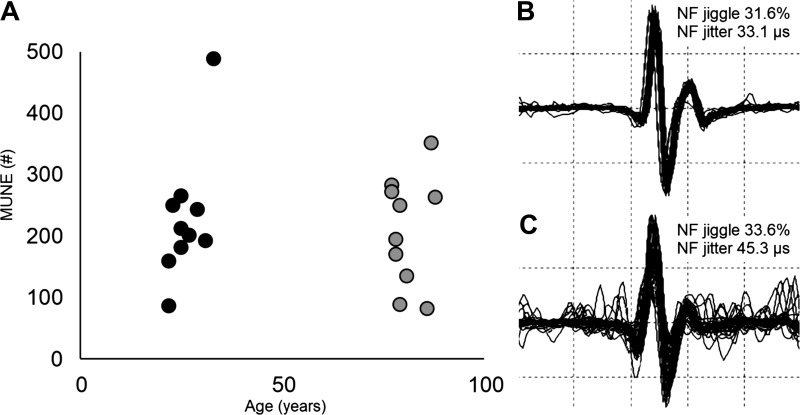

A total of 524 MUPTs were measured from the ST muscle with 254 from the young and 270 from the old. During contractions at 15% of MVC, the number of contractions, validated MUPTs averaged per individual, and mean DQEMG parameters for each age group are presented in Table 3. Unexpectedly, the derived MU number estimate (MUNE) of the ST muscle was not statistically different between young and old groups (t18 = 1.73, P = 0.33; Fig. 3A), despite significant differences in age, force, CMAP parameters and MU discharge frequencies (Tables 1 and 2). Considering parameters that importantly contribute to the MUNE calculation, negative peak amplitude and area of the CMAP were smaller and statistically different in the old group (Table 3). The mean SMUP negative peak amplitude (P = 0.17) and area (P = 0.23) had smaller mean values in the old group; however, they did not achieve statistical significance. In addition, there was also no difference in MUP peak-to-peak amplitude between age groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Accessory nerve stimulation and DQEMG of the ST muscle

| Parameter | Young | Old |

|---|---|---|

| Supramaximal stimulation, mA | 120 ± 31 | 114 ± 29 |

| CMAP –pk amplitude, mV | 12.6 ± 1.9 | 6.8 ± 1.3* |

| CMAP –pk area, mV·ms | 1,287.4 ± 552.7 | 589.5 ± 409.1* |

| Number of contractions | 8 ± 2 | 9 ± 1 |

| MUPTs/participant number | 25 ± 5 | 27 ± 6 |

| MUPTs/contraction | 3 ± 1 | 3 ± 1 |

| MUP pk-pk amplitude, µV | 702.1 ± 128.4 | 688.4 ± 160.9 |

| mSMUP –pk amplitude, µV | 71.1 ± 27.9 | 53.3 ± 16.4 |

| mSMUP –pk area, µV·ms | 427.7 ± 111.2 | 361.3 ± 104.9 |

| MUNE –pk area number | 228 ± 105 | 209 ± 89 |

Values are presented as the ensemble means ± SD; n = 20. Decomposition-based quantitative electromyography (DQEMG) of the superior trapezius (ST) muscle at 15% maximal voluntary isometric contraction (MVC). CMAP, compound mass action potential; –pk, negative peak; MUPT, motor unit potential trains; MUNE, motor unit number estimate; MUP, motor unit potential; pk-pk, peak to peak; mSMUP, mean surface motor unit potential.

P < 0.05.

Fig. 3.

Negative peak motor unit (MU) number estimates (MUNE) of the superior trapezius muscle. A: scatterplot representing the MUNE for each participant dependent on age (n = 20). B and C: near fiber (NF) MU potential overlay from the concentric needle and measurement from the decomposition-based quantitative electromyography algorithm between a young (B) and old (C) participant, respectively. the y-axis is 10 kV·s−2·division−1, and the x-axis is 1 ms/division.

Parameters of NF MUP stability were compared for further examination of collateral reinnervation due to the possibility of age-related MU loss that was not detected in the mean SMUP (Table 4). From the original sample of MUPTs accepted from DQEMG analysis, a total subset of 314 discrete MUPTs with 132 from the young and 182 from the old were acceptable for NF statistics used for stability comparisons (Fig. 3, B and C). Consistent with the MUNE calculation, there was no difference in the NF jitter and NF jiggle between age groups (Table 4). Parameters that demonstrated age-related differences were NF MUP area, mean turn area, and NF duration values, which were significantly lower in the old as compared with the young. The old group also had significantly higher NF counts as compared with the young group (Table 4). In the young, a correlation was nonsignificant between NF MUP area and NF counts (r = −0.11, P = 0.23), whereas in the old this relationship was positive and significant (r = 0.22, P < 0.05). This may indicate that although mean NF MUP area was smaller in the old group (Table 4), larger NF MUP area had a positive relationship with NF counts as compared with the young group.

Table 4.

NF MUP stability of the ST muscle

| Parameter | Young | Old |

|---|---|---|

| MUPTs/participant | 13 ± 4 | 18 ± 8 |

| NF jitter, µs | 37.3 ± 12.4 | 40.6 ± 11.6 |

| NF jiggle, % | 40.1 ± 4.7 | 38.8 ± 5.6 |

| NF MUP area, kV·s−2·ms−1 | 9.4 ± 2.1 | 6.2 ± 1.4* |

| Mean turn area, kV·s−2·ms−1 | 9.4 ± 3.8 | 6.3 ± 2.0* |

| NF duration, ms | 0.66 ± 0.10 | 0.55 ± 0.11* |

| NF count number | 1.67 ± 0.21 | 1.91 ± 0.25* |

Values are presented as the ensemble means ± SD; n = 20. Decomposition-based quantitative electromyography motor unit potential (MUP) stability of the superior trapezius (ST) muscle during 15% MVC. MUPTs, motor unit potential trains; NF, near fiber.

P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

This investigation compared electrophysiological parameters in the ST muscle between young and old men. These findings indicate that the ST muscle is unique in comparison to the human genioglossus, hand, and limb muscles studied to date. With advanced age, MU discharge frequencies were lower in the old during normalized contraction intensities (Fig. 2), despite no statistical differences in MUNE (Table 3) or NF MUP stability parameters of jitter and jiggle (Table 4). Furthermore, MU size was not greater in the old compared with the young based on evidence from lower CMAP amplitude and area; no difference in mean SMUP amplitude and area; lower NF duration; lower NF MUP area; and higher NF counts in the old (Tables 3 and 4). Therefore, reduced voluntary strength in the old group occurred with lower MU discharge frequencies and no detected increase in MU size for the ST muscle.

The DQEMG MUNE method has been used in numerous human hand and limb muscles detecting statistically significant differences of MUNE in aging and disease (Allen et al. 2013; Chan et al. 2001; Dalton et al. 2008; Gilmore et al. 2017, 2018; Hourigan et al. 2015; Ives and Doherty 2014a; McKinnon et al. 2015; McNeil et al. 2005; Saboisky et al. 2014). With the use of this method, the ST muscle did not demonstrate a significant age-related difference of MUNE in the old (Table 3 and Fig. 3), and this finding was unexpected given the age range between groups (22–33 and 77–88 yr). From prior investigations of other muscles, lower MUNE values are reported in the old due to smaller CMAPs and increased mean SMUPs and have supported the hypothesis of age-related collateral reinnervation (Doherty and Brown 1993; Ling et al. 2009; Stålberg and Fawcett 1982). From the present investigation, mean MUNE counts in the ST muscle (Table 3) agree with mean values reported from other investigators using the same (Ives and Doherty 2014b) and a different MUNE technique (Grimaldi et al. 2017). In comparing present MUNE values to anatomical counts of the spinal accessory nerve (Vathana et al. 2007), myelinated axons counted at the superior (1,383 ± 291), midway (1,064 ± 185), and posterior segments (868 ± 148) of the same nerve were reported from 10 cadavers (75–95 yr). Because the myelinated axons counts were lower at the midway region, as compared with the superior segment (Vathana et al. 2007), inferences can be made by the difference in mean values of ~319 myelinated axons that may be specific to the ST muscle region (Table 3). It is important to consider that such anatomical counts could not discriminate between intrafusal and extrafusal myelinated axons, whereas DQEMG provides an estimate of extrafusal fiber activity in the local area of the CMAP. Thus, although absolute numbers of extrafusal motor axons or neurons are unknown, the present MUNE values for the ST muscle may be reasonable based on the anatomical data.

In humans, electrophysiological evidence for enlargement of the surviving MU population by collateral sprouting and reinnervation of near-by denervated muscle fibers has been described (Doherty and Brown 1993; Krarup et al. 2016; Ling et al. 2009; Stålberg and Fawcett 1982). In the ST muscle, expansion of MU size was not detected as supported by no increase of the MUP or SMUP sizes (Tables 3 and 4), and no difference in transmission stability parameters of NF jitter or NF jiggle between age groups (Fig. 3 and Table 4). NF jitter values (Table 4) were within the range of clinically normal values from the single fiber EMG technique (<50 µs) (Stålberg et al. 2016), and NF jiggle values were higher as compared with the tibialis anterior and vastus medialis muscles (Hourigan et al. 2015) but were below values reported in the tibialis anterior for individuals classified as presarcopenic or sarcopenic (Gilmore et al. 2017). The finding that NF jitter and jiggle values are not different between age groups supported that muscle fibers may not be undergoing active reinnervation. This finding in the human ST muscle was also unexpected, as investigations derived from muscles supplied by spinal motor neurons show evidence of age-related MU loss, instability, and expansion in humans (Allen et al. 2013; Chan et al. 2001; Dalton et al. 2008; Gilmore et al. 2017, 2018; Hourigan et al. 2015; McKinnon et al. 2015; McNeil et al. 2005). Instead, smaller NF MUP size and greater NF counts in the old group combined with measures of the MUP and SMUP indicate age-related ST muscle fiber atrophy (Tables 3 and 4). Specifically, mean NF counts in the old were significantly higher by ~114% and mean NF MUP area was lower by ~34% (Table 4). In muscles from aged humans, atrophy and fiber grouping occurs (Edström and Larsson 1987; Hashizume et al. 1988; Jakobsson et al. 1990; Lexell and Downham 1991), with similar findings of atrophy and degradation of muscle fibers in murine models (Gutmann and Hanzliková 1966; Hooper 1981). With atrophy, there are reports for maintained collateral reinnervation in very old rats (Gutmann et al. 1971; Kung et al. 2014); however, it is also possible that the physiological mechanisms required for reinnervation are not attained or halted (Aare et al. 2016). As demonstrated in one investigation of very old men, there was evidence for deceased or halted collateral reinnervation concurrent with lower MUNE values in a muscle supplied by spinal efferents (Gilmore et al. 2018). Altogether, the present findings indicated that in the ST muscle the age-related effect of collateral reinnervation was not detected with the relative preservation of motor axons quantified using the DQEMG MUNE technique. This result may be influenced by factors related to the mixed innervation to the ST muscle and evidence for decreased MU remodeling that have been observed in very old age (Gilmore et al. 2018).

Differences found in the ST muscle compared with other muscles studied may be due to how spinal and brainstem axons respond differently to injury. For age-related comparisons of a muscle with only brainstem innervation, the genioglossus (cranial nerve XII), concentric needle macro MUP amplitude, and area were larger and had longer duration in the old suggesting active MU remodeling (Saboisky et al. 2014). From murine models, there is evidence for the preservation of hypoglossal motor nuclei in aged animals (Schwarz et al. 2009), therefore, such MU remodeliing may not be dependent on motor neuron loss. In comparing permanent axotomy in murine spinal and brainstem motor neurons (Rende et al. 1995), there is evidence for brainstem (hypoglossal) motor neurons having a different response to axotomy with longer maintenance for a low-affinity nerve growth factor receptor (p75) with short-term progressive decreases in choline acetyltransferase as compared with spinal motor neurons. Greater motor neuron survival and protective responses of brainstem motor neurons from the murine model may provide some rationale as to why MUNE, MUP size, and NF stability in the ST muscle do not follow the usual age-related findings of spinally innervated muscles.

The mammalian brainstem is an evolutionarily conserved region housing cranial nerves essential for survival, which may have importance in our observation of ST MU preservation (Fig. 3). In murine models, the brainstem has greater protection from ischemic injury (Brisson et al. 2014) and motor neuron loss is not observed to occur in some brainstem nuclei (Schwarz et al. 2009; Sturrock 1989, 1991). In motor nuclei from cranial nerves III, IV, and VI, which have oculomotor efferent supply (Sturrock 1989, 1991) and cranial nerve XII which has hypoglossal efferent supply (Schwarz et al. 2009), age-related motor neuron loss was not detected. However, in cranial nerves V, VII, IX, and X, age-related motor neuron loss did occur (Sturrock 1987, 1988a, 1988b, 1990). From these studies of brainstem nuclei, chronic use was suggested to facilitate the preservation of motor neurons in advanced aging (Sturrock 1991), although motor neuron counts of the cranial accessory nucleus (which supply the ST muscle) were not reported. Rationale for the age-related preservation of motor neurons that supply the ST muscle, supported from no age-related difference in MUNE (Fig. 3), may be further influenced by shorter motor axons (McComas 1998) and complex chronic activity of the ST muscle (Falla and Farina 2008).

In addition to electrophysiological measures of MU size and stability from DQEMG at 15% MVC, MU discharge rate profiles at a range of contraction intensities up to MVC for each participant were investigated. In the ST muscle, the large number of sampled MU showed the capacity to discharge at high frequencies, similar to mean frequencies of some human hand muscles at MVC (Erim et al. 1999; Kamen et al. 1995; Patten et al. 2001). At MVC in the ST muscle of the young, mean discharge frequencies were near 50 Hz (Table 2), and these higher frequencies may be explained by the greater intrinsic excitability of brainstem motor neurons (Bailey et al. 2007; Tadros et al. 2016) as compared with large limb muscles which rate code within a lower frequency range (Bellemare et al. 1983; Dalton et al. 2009, 2010; Kamen 2005; Kirk et al. 2016, 2018; Roos et al. 1999). Because MUNE counts were not different, significant reductions of MU discharge frequencies with advanced age may be more explained from a variety of other factors independent of motor neuron loss, including the degeneration of synaptic inputs (Maxwell et al. 2018), altered depolarization threshold at the motor neuron (Webber et al. 2009), and changes in afferent transmission to the motor neuron (Vaughan et al. 2017). Despite muscle weakness occurring in adult aging, it is apparent that unlike many limb muscles tested to date, diminished discharge rates in the ST can occur without a relative difference in MUNE or apparent strong evidence for remodeling of the sampled MU population.

To control for age-dependent variance based on biological sex and physical activity, only males were tested and recruited from active exercising populations (Booth et al. 2017). A limitation of the present study, consistent with most in vivo studies using humans, is the assessment of neuronal properties from the muscle and not directly at the motor neuron. Furthermore, this study design is cross-generational comparing young and old not taking into consideration the heritable influences among individuals and groups. It should also be considered that a sample of the entire MU population may not have been captured because MUNE were compared between young and old at a contraction intensity of 15% MVC (Stevens et al. 2014). In addition, the DQEMG technique, like all MUNE methods, provides an estimate with no accepted standard but likely reflects relative values between groups. Furthermore, because DQEMG was used during a low contraction intensity, it should also be considered that parameters of NF MUP stability (such as jitter and jiggle) could be different between age groups as a higher contraction intensity would have recruited larger MU types.

In summary, age-related changes in the human ST muscle resulted in muscle weakness and lower MU discharge frequencies that were not related to lower MUNE values or our detected parameters of collateral reinnervation between age groups. In the ST muscle, electrophysiological evidence of muscle fiber atrophy without differences in MUNE and NF MUP stability parameters indicated that compensatory MU remodeling by collateral reinnervation may not have been initiated. These data support that motor neurons located within the brainstem and the proximal portion of the spinal cord may have differential outcomes with aging.

GRANTS

This investigation was supported by a Discovery Grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (180970; to C. L. Rice) and from the Alexander Graham Bell Canada Graduate Scholarships (awarded to E. A. Kirk and K. J. Gilmore).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

E.A.K., K.J.G., D.W.S., T.J.D., and C.L.R. conceived and designed research; E.A.K., K.J.G., and C.L.R. performed experiments; E.A.K., K.J.G., D.W.S., and C.L.R. analyzed data; E.A.K., K.J.G., D.W.S., T.J.D., and C.L.R. interpreted results of experiments; E.A.K. prepared figures; E.A.K., D.W.S., and C.L.R. drafted manuscript; E.A.K., K.J.G., D.W.S., T.J.D., and C.L.R. edited and revised manuscript; E.A.K., K.J.G., D.W.S., T.J.D., and C.L.R. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank those at the Canadian Centre for Activity and Aging and Retirement Research Association for participation. We also are grateful to J. J. W. Watson for guidance and helpful suggestions about head and neck muscle force measures.

REFERENCES

- Aare S, Spendiff S, Vuda M, Elkrief D, Perez A, Wu Q, Mayaki D, Hussain SN, Hettwer S, Hepple RT. Failed reinnervation in aging skeletal muscle. Skelet Muscle 6: 29, 2016. doi: 10.1186/s13395-016-0101-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander CM, Harrison PJ. The bilateral reflex control of the trapezius muscle in humans. Exp Brain Res 142: 418–424, 2002. doi: 10.1007/s00221-001-0951-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen MD, Choi IH, Kimpinski K, Doherty TJ, Rice CL. Motor unit loss and weakness in association with diabetic neuropathy in humans. Muscle Nerve 48: 298–300, 2013. doi: 10.1002/mus.23792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey EF, Rice AD, Fuglevand AJ. Firing patterns of human genioglossus motor units during voluntary tongue movement. J Neurophysiol 97: 933–936, 2007. doi: 10.1152/jn.00737.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banker BQ, Kelly SS, Robbins N. Neuromuscular transmission and correlative morphology in young and old mice. J Physiol 339: 355–377, 1983. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellemare F, Woods JJ, Johansson R, Bigland-Ritchie B. Motor-unit discharge rates in maximal voluntary contractions of three human muscles J Neurophysiol 50: 1380–1392, 1983. doi: 10.1152/jn.1983.50.6.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boe SG, Stashuk DW, Doherty TJ. Motor unit number estimation by decomposition-enhanced spike-triggered averaging: control data, test-retest reliability, and contractile level effects. Muscle Nerve 29: 693–699, 2004. doi: 10.1002/mus.20031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth FW, Roberts CK, Thyfault JP, Ruegsegger GN, Toedebusch RG. Role of inactivity in chronic diseases: evolutionary insight and pathophysiological mechanisms. Physiol Rev 97: 1351–1402, 2017. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00019.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brisson CD, Hsieh YT, Kim D, Jin AY, Andrew RD. Brainstem neurons survive the identical ischemic stress that kills higher neurons: insight to the persistent vegetative state. PLoS One 9: e96585, 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown WF, Strong MJ, Snow R. Methods for estimating numbers of motor units in biceps‐brachialis muscles and losses of motor units with aging. Muscle Nerve 11: 423–432, 1988. doi: 10.1002/mus.880110503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell MJ, McComas AJ, Petito F. Physiological changes in ageing muscles. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 36: 174–182, 1973. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.36.2.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan KM, Doherty TJ, Brown WF. Contractile properties of human motor units in health, aging, and disease. Muscle Nerve 24: 1113–1133, 2001. doi: 10.1002/mus.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connelly DM, Rice CL, Roos MR, Vandervoort AA. Motor unit firing rates and contractile properties in tibialis anterior of young and old men. J Appl Physiol (1985) 87: 843–852, 1999. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.2.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton BH, Harwood B, Davidson AW, Rice CL. Triceps surae contractile properties and firing rates in the soleus of young and old men. J Appl Physiol (1985) 107: 1781–1788, 2009. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00464.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton BH, Jakobi JM, Allman BL, Rice CL. Differential age-related changes in motor unit properties between elbow flexors and extensors. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 200: 45–55, 2010. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2010.02100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton BH, McNeil CJ, Doherty TJ, Rice CL. Age-related reductions in the estimated numbers of motor units are minimal in the human soleus. Muscle Nerve 38: 1108–1115, 2008. doi: 10.1002/mus.20984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty TJ, Brown WF. The estimated numbers and relative sizes of thenar motor units as selected by multiple point stimulation in young and older adults. Muscle Nerve 16: 355–366, 1993. doi: 10.1002/mus.880160404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty TJ, Stashuk DW. Decomposition-based quantitative electromyography: methods and initial normative data in five muscles. Muscle Nerve 28: 204–211, 2003. doi: 10.1002/mus.10427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edström L, Larsson L. Effects of age on contractile and enzyme-histochemical properties of fast- and slow-twitch single motor units in the rat. J Physiol 392: 129–145, 1987. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erim Z, Beg MF, Burke DT, de Luca CJ. Effects of aging on motor-unit control properties. J Neurophysiol 82: 2081–2091, 1999. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.5.2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahrer H, Ludin HP, Mumenthaler M, Neiger M. The innervation of the trapezius muscle. An electrophysiological study. J Neurol 207: 183–188, 1974. doi: 10.1007/BF00312559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falla D, Farina D. Motor units in cranial and caudal regions of the upper trapezius muscle have different discharge rates during brief static contractions. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 192: 551–558, 2008. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2007.01776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore KJ, Kirk EA, Doherty TJ, Rice CL. Effect of very old age on anconeus motor unit loss and compensatory remodelling. Muscle Nerve 57: 659–663, 2018. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore KJ, Morat T, Doherty TJ, Rice CL. Motor unit number estimation and neuromuscular fidelity in 3 stages of sarcopenia. Muscle Nerve 55: 676–684, 2017. doi: 10.1002/mus.25394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer JJ, Funk GD. Perinatal development of respiratory motoneurons. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 149: 43–61, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2005.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimaldi S, Duprat L, Grapperon AM, Verschueren A, Delmont E, Attarian S. Global motor unit number index sum score for assessing the loss of lower motor neurons in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve 56: 202–206, 2017. doi: 10.1002/mus.25595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutmann E, Hanzlíková V. Motor unit in old age. Nature 209: 921–922, 1966. doi: 10.1038/209921b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutmann E, Hanzlíková V, Vysokocil F. Age changes in cross striated muscle of the rat. J Physiol 216: 331–343, 1971. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1971.sp009528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashizume K, Kanda K, Burke RE. Medial gastrocnemius motor nucleus in the rat: age-related changes in the number and size of motoneurons. J Comp Neurol 269: 425–430, 1988. doi: 10.1002/cne.902690309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepple RT, Rice CL. Innervation and neuromuscular control in ageing skeletal muscle. J Physiol 594: 1965–1978, 2016. doi: 10.1113/JP270561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper AC. Length, diameter and number of ageing skeletal muscle fibres. Gerontology 27: 121–126, 1981. doi: 10.1159/000212459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hourigan ML, McKinnon NB, Johnson M, Rice CL, Stashuk DW, Doherty TJ. Increased motor unit potential shape variability across consecutive motor unit discharges in the tibialis anterior and vastus medialis muscles of healthy older subjects. Clin Neurophysiol 126: 2381–2389, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ives CT, Doherty TJ. Intra- and inter-rater reliability of motor unit number estimation and quantitative motor unit analysis in the upper trapezius. Clin Neurophysiol 123: 200–205, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ives CT, Doherty TJ. Intra-rater reliability of motor unit number estimation and quantitative motor unit analysis in subjects with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Clin Neurophysiol 125: 170–178, 2014a. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2013.04.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ives CT, Doherty TJ. Influence of needle electrode depth on DE-STA motor unit number estimation. Muscle Nerve 50: 587–592, 2014b. doi: 10.1002/mus.24208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob JM. Lumbar motor neuron size and number is affected by age in male F344 rats. Mech Ageing Dev 106: 205–216, 1998. doi: 10.1016/S0047-6374(98)00117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsson F, Borg K, Edström L. Fibre-type composition, structure and cytoskeletal protein location of fibres in anterior tibial muscle. Comparison between young adults and physically active aged humans. Acta Neuropathol 80: 459–468, 1990. doi: 10.1007/BF00294604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamen G. Aging, resistance training, and motor unit discharge behavior. Can J Appl Physiol 30: 341–351, 2005. doi: 10.1139/h05-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamen G, Sison SV, Du CC, Patten C. Motor unit discharge behavior in older adults during maximal-effort contractions. J Appl Physiol (1985) 79: 1908–1913, 1995. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.79.6.1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kierner AC, Zelenka I, Burian M. How do the cervical plexus and the spinal accessory nerve contribute to the innervation of the trapezius muscle? As seen from within using Sihler’s stain. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 127: 1230–1232, 2001. doi: 10.1001/archotol.127.10.1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk EA, Copithorne DB, Dalton BH, Rice CL. Motor unit firing rates of the gastrocnemii during maximal and sub-maximal isometric contractions in young and old men. Neuroscience 330: 376–385, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.05.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk EA, Gilmore KJ, Rice CL. Neuromuscular changes of the aged human hamstrings. J Neurophysiol 120: 480–488, 2018. doi: 10.1152/jn.00794.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk EA, Rice CL. Contractile function and motor unit firing rates of the human hamstrings. J Neurophysiol 117: 243–250, 2017. doi: 10.1152/jn.00620.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krarup C, Boeckstyns M, Ibsen A, Moldovan M, Archibald S. Remodeling of motor units after nerve regeneration studied by quantitative electromyography. Clin Neurophysiol 127: 1675–1682, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2015.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulakowski SA, Parker SD, Personius KE. Reduced TrkB expression results in precocious age-like changes in neuromuscular structure, neurotransmission, and muscle function. J Appl Physiol (1985) 111: 844–852, 2011. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00070.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung TA, Cederna PS, van der Meulen JH, Urbanchek MG, Kuzon WM Jr, Faulkner JA. Motor unit changes seen with skeletal muscle sarcopenia in oldest old rats. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 69: 657–665, 2014. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lexell J, Downham DY. The occurrence of fibre-type grouping in healthy human muscle: a quantitative study of cross-sections of whole vastus lateralis from men between 15 and 83 years. Acta Neuropathol 81: 377–381, 1991. doi: 10.1007/BF00293457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lexell J, Taylor CC, Sjöström M. What is the cause of the ageing atrophy?. Total number, size and proportion of different fiber types studied in whole vastus lateralis muscle from 15- to 83-year-old men. J Neurol Sci 84: 275–294, 1988. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(88)90132-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling SM, Conwit RA, Ferrucci L, Metter EJ. Age-associated changes in motor unit physiology: observations from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 90: 1237–1240, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.09.565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez ME, Van Zeeland NL, Dahl DB, Weindruch R, Aiken JM. Cellular phenotypes of age-associated skeletal muscle mitochondrial abnormalities in rhesus monkeys. Mutat Res 452: 123–138, 2000. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(00)00059-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell N, Castro RW, Sutherland NM, Vaughan KL, Szarowicz MD, de Cabo R, Mattison JA, Valdez G. α-Motor neurons are spared from aging while their synaptic inputs degenerate in monkeys and mice. Aging Cell 17: e12726, 2018. doi: 10.1111/acel.12726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McComas AJ. Oro-facial muscles: internal structure, function and ageing. Gerodontology 15: 3–14, 1998. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.1998.00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon NB, Montero-Odasso M, Doherty TJ. Motor unit loss is accompanied by decreased peak muscle power in the lower limb of older adults. Exp Gerontol 70: 111–118, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil CJ, Doherty TJ, Stashuk DW, Rice CL. Motor unit number estimates in the tibialis anterior muscle of young, old and very old men. Clin Neurophysiol 116: 1342–1347, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patten C, Kamen G, Rowland DM. Adaptations in maximal motor unit discharge rate to strength training in young and older adults. Muscle Nerve 24: 542–550, 2001. doi: 10.1002/mus.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash YS, Sieck GC. Age-related remodeling of neuromuscular junctions on type-identified diaphragm fibers. Muscle Nerve 21: 887–895, 1998. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pu YM, Tang EY, Yang XD. Trapezius muscle innervation from the spinal accessory nerve and branches of the cervical plexus. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 37: 567–572, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rende M, Giambanco I, Buratta M, Tonali P. Axotomy induces a different modulation of both low-affinity nerve growth factor receptor and choline acetyltransferase between adult rat spinal and brainstem motoneurons. J Comp Neurol 363: 249–263, 1995. doi: 10.1002/cne.903630207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich C, O’Brien GL, Cafarelli E. Probabilities associated with counting average motor unit firing rates in active human muscle. Can J Appl Physiol 23: 87–94, 1998. doi: 10.1139/h98-006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos MR, Rice CL, Connelly DM, Vandervoort AA. Quadriceps muscle strength, contractile properties, and motor unit firing rates in young and old men. Muscle Nerve 22: 1094–1103, 1999. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenheimer JL, Smith DO. Differential changes in the end-plate architecture of functionally diverse muscles during aging. J Neurophysiol 53: 1567–1581, 1985. doi: 10.1152/jn.1985.53.6.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saboisky JP, Stashuk DW, Hamilton-Wright A, Trinder J, Nandedkar S, Malhotra A. Effects of aging on genioglossus motor units in humans. PLoS One 9: e104572, 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz EC, Thompson JM, Connor NP, Behan M. The effects of aging on hypoglossal motoneurons in rats. Dysphagia 24: 40–48, 2009. doi: 10.1007/s00455-008-9169-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stålberg E, Fawcett PR. Macro EMG in healthy subjects of different ages. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 45: 870–878, 1982. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.45.10.870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stålberg E, Sanders DB, Ali S, Cooray G, Leonardis L, Löseth S, Machado F, Maldonado A, Martinez-Aparicio C, Sandberg A, Smith B, Widenfalk J, Aris Kouyoumdjian J. Reference values for jitter recorded by concentric needle electrodes in healthy controls: A multicenter study. Muscle Nerve 53: 351–362, 2016. doi: 10.1002/mus.24750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stashuk DW. Decomposition and quantitative analysis of clinical electromyographic signals. Med Eng Phys 21: 389–404, 1999a. doi: 10.1016/S1350-4533(99)00064-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stashuk DW. Detecting single fiber contributions to motor unit action potentials. Muscle Nerve 22: 218–229, 1999b. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens DE, Harwood B, Power GA, Doherty TJ, Rice CL. Anconeus motor unit number estimates using decomposition-based quantitative electromyography. Muscle Nerve 50: 52–59, 2014. doi: 10.1002/mus.24092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturrock RR. Age-related changes in the number of myelinated axons and glial cells in the anterior and posterior limbs of the mouse anterior commissure. J Anat 150: 111–127, 1987. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturrock RR. Loss of neurons from the motor nucleus of the facial nerve in the ageing mouse brain. J Anat 160: 189–194, 1988a. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturrock RR. A quantitative histological study of neuroglial number in the retrofacial, facial and trigeminal motor nuclei in the ageing mouse brain. J Anat 161: 153–157, 1988b. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturrock RR. Stability of neuron and glial number in the parabigeminal nucleus of the ageing mouse. Acta Anat (Basel) 134: 322–326, 1989. doi: 10.1159/000146710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturrock RR. A comparison of age-related changes in neuron number in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus and the nucleus ambiguus of the mouse. J Anat 173: 169–176, 1990. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturrock RR. Stability of motor neuron number in the oculomotor and trochlear nuclei of the ageing mouse brain. J Anat 174: 125–129, 1991. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadros MA, Fuglevand AJ, Brichta AM, Callister RJ. Intrinsic excitability differs between murine hypoglossal and spinal motoneurons. J Neurophysiol 115: 2672–2680, 2016. doi: 10.1152/jn.01114.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JL, Olsen HB, Sjøgaard G, Søgaard K. Voluntary activation of trapezius measured with twitch interpolation. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 19: 584–590, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terao S, Sobue G, Hashizume Y, Li M, Inagaki T, Mitsuma T. Age-related changes in human spinal ventral horn cells with special reference to the loss of small neurons in the intermediate zone: a quantitative analysis. Acta Neuropathol 92: 109–114, 1996. doi: 10.1007/s004010050497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson BE, Irving D. The numbers of limb motor neurons in the human lumbosacral cord throughout life. J Neurol Sci 34: 213–219, 1977. doi: 10.1016/0022-510X(77)90069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vathana T, Larsen M, de Ruiter GC, Bishop AT, Spinner RJ, Shin AY. An anatomic study of the spinal accessory nerve: extended harvest permits direct nerve transfer to distal plexus targets. Clin Anat 20: 899–904, 2007. doi: 10.1002/ca.20545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan SK, Stanley OL, Valdez G. Impact of aging on proprioceptive sensory neurons and intrafusal muscle fibers in mice. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 72: 771–779, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webber SC, Porter MM, Gardiner PF. Modeling age-related neuromuscular changes in humans. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 34: 732–744, 2009. doi: 10.1139/H09-052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisberger EC. The efferent supply of the trapezius muscle: a neuroanatomic basis for the preservation of shoulder function during neck dissection. Laryngoscope 97: 435–445, 1987. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198704000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wokke JH, Jennekens FG, van den Oord CJ, Veldman H, Smit LM, Leppink GJ. Morphological changes in the human end plate with age. J Neurol Sci 95: 291–310, 1990. doi: 10.1016/0022-510X(90)90076-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright EA, Spink JM. A study of the loss of nerve cells in the central nervous system in relation to age. Gerontologia 3: 277–287, 1959. doi: 10.1159/000210907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]