Abstract

Objective: Much has been written about the patients’ perspective concerning weight management in health care. The purpose of this survey study was to assess perspectives of primary care providers (PCPs) and nurses toward patient weight management and identify possible areas of growth. Patients and Methods: We emailed a weight management–focused survey to 674 eligible participants (437 [64.8%] nurses and 237 [35.2%] PCPs) located in 5 outpatient primary care clinics. The survey focused on opportunities, practices, knowledge, confidence, attitudes, and beliefs. A total of 219 surveys were returned (137 [62.6%] from nurses and 82 [34.4%] from PCPs). Results: Among 219 responders, 85.8% were female and 93.6% were white non-Hispanic. In this study, PCPs and nurses believed obesity to be a major health problem. While PCPs felt more equipped than nurses to address weight management (P < .001) and reported receiving more training than nurses (50.0% vs 17.6%, respectively), both felt the need for more training on obesity (73.8% and 79.4%, respectively). Although, PCPs also spent more patient contact time providing weight management services versus nurses (P < .001), the opportunity/practices score was lower for PCPs than nurses (−0.35 ± 0.44 vs −0.17 ± 0.41, P < .001) with PCPs more likely to say they lacked the time to discuss weight and they worried it would cause a poor patient-PCP relationship. The knowledge/confidence score also differed significantly between the groups, with nurses feeling less equipped to deal with weight management issues than PCPs (−0.42 ± 0.43 vs −0.03 ± 0.55, P < .001). Neither group seemed very confident, with those in the PCP group only answering with an average score of neutral. Conclusion: By asking nurses and PCP general questions about experiences, attitudes, knowledge, and opinions concerning weight management in clinical care, this survey has identified areas for growth in obesity management. Both PCPs and nurses would benefit from additional educational training on weight management.

Keywords: obesity, primary care, community health centers, managed care, community health

Introduction

Practice guidelines are well established for the management of patients with overweight and obesity issues, which call for health care providers (HCPs) to identify, counsel, and offer treatment management (ie, ask, advise, treat).1 HCPs include both nurses and primary care providers (PCPs). The nurses include licensed practical nurses (LPNs) and registered nurses (RNs) while the PCPs include physician assistants (PAs), nurse practitioners (NPs), medical doctors (MDs), and doctors of osteopathic medicine (DOs). In 2003, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommended that clinicians screen all adult patients for obesity and offer intensive counseling and behavioral interventions for weight management. In 2011, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services delineated requirements for behavioral therapy for obesity2; the Obesity Expert Panel subsequently published practice guidelines to address weight management in the health care setting.1

A recent review of over 248 publications3 concluded that primary care doctors and nurses were well positioned to give weight related health advice; however, advice provided was overall of poor quality mainly due to educational barriers and availability of resources. In a recent web based survey of over 330 000 medical professionals, 67% of respondents indicated that having more time with patients would improve their ability to counsel on obesity.4 In addition, surveyed PCPs and nurses felt that their care of patients with obesity could be enhanced if given more time (70%), additional training in obesity management (53%), improved reimbursement (53%), and better tools to help patients recognize obesity risks (50%).4

Insufficient time and inadequate skills/training were the most frequently cited barriers in the literature that were associated with suboptimum implementation of the USPSTF guidelines on obesity management in primary care settings. A recent survey of family and pediatric practitioners identified lack of time (73%) as the most frequent barrier to pediatric obesity care.5 This has been corroborated by a past analysis of 6368 primary care visits from 2005-2006 in the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS).6 In this survey it was found that the average primary care visit was 21.77 minutes and the time spent addressing weight related conditions was 5.65 minutes (30%), with only 1.75 minutes (8.0%) attributable to overweight and obesity.6 The 8% included the amount of time spent to evaluate and treat patients with weight-related conditions that can be attributed to a single risk factor, excess weight (ie, overweight and obesity). Given the time constraints across practices, the USPSTF has acknowledged the potential difficulty in offering an intensive intervention program on obesity and has suggested that clinicians can increase patient motivation to engage in weight loss, if they consider collaborative treatment with multidisciplinary teams,7 which appears to be effective when they are being followed.8 Unfortunately, these treatment guidelines continued to be underutilized by PCPs,9-12 who often felt unable to initiate intensive behavioral treatments. In a recent web-based survey of 1506 practitioners, only 16% of the respondents indicated that obesity counseling should be provided according to the USPSTF guidelines, confirming significant gaps in HCP knowledge of the guidelines.11

Previous studies utilizing patient surveys demonstrated that while patients believed that their PCP should have a role in their weight management, they perceived that the PCP may not necessarily have the skills needed to help them.13,14 The PCPs lack of knowledge for diagnosing obesity, lack of confidence, and need for more training in caring for patients with obesity had been corroborated by a number of recent studies.10,15-17 An earlier study showed that general practitioners’ attendance at continuing professional development clearly increased their confidence to manage adult or childhood obesity.18 Interestingly, a study of 25 residency program showed that residency programs averaged 2.8 hours per year of didactics in training on obesity, nutrition, and physical activity–related topics; whereas, the didactics were associated with greater knowledge (P = .01), they were also associated with poorer attitudes (P < .001) and poorer perception of professional norms (P = .004) about counseling in this area.19 As the authors indicate, this could be that didactics highlighted the complexity of the issue and created a sense of frustration at the enormous task involved in addressing this area, but it could have also reinforced a pervasive negativity toward it.

The overall purpose of this study was to evaluate the knowledge, experiences, attitudes, and needs of the PCPs and nurses, within 5 outpatient community health clinics, regarding the delivery of weight management care to patients who are obese or overweight in order to identify opportunities for improving care to patients with overweight and obesity in primary care.

Methods

The present study was a cross-sectional survey of medical staff assigned to care of patients within the community health practices in a single institution. The medical staff surveyed included all LPNs, RNs, PAs, NPs, MDs and DOs, whose assignment was within the Employee Community Health (ECH) practice at a Midwest practice in the United States. This practice consists of 3 divisions: Community Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, Family Medicine, and Community Internal Medicine operating at 5 different free-standing local clinics.

This study was reviewed by the institutional review board (IRB) and determined to be exempt under section 45 CFR 46.101, item 2. During the study, all significant changes to study design and procedures continued to be appropriately filed and reviewed by the IRB, which continued exemption determination status.

Survey Development

The survey focused on opportunities, practices, knowledge, confidence, attitudes, and beliefs around weight management among PCP and nurses in a community health care setting. Ten of the 60 questions included in the survey had been used previously in other studies.10,20 The additional 50 questions were developed by the study team. Pilot testing of the survey was conducted with 9 clinicians to assess the acceptability, readability, and understandability of the survey. The pilot survey underwent 4 rounds of testing and refinement before it was finalized. Because of the burden of a busy practice, efforts were made to keep the survey instrument very brief. The resulting survey took 5 minutes to complete.

Wording of the questions are found in Appendix Tables A1-A5. A number of the questions had branching logic and a majority of the questions had Likert-type scale responses, which included responses such as “strongly agree,” “agree,” “neutral,” “disagree,” and “strongly disagree.” The 7 overarching components of the survey were (1) demographics, (2) training, (3) beliefs/opinions, (4) knowledge, (5) attitudes, (6) practices, and (7) perceived needs.

All surveys consisted of an email, which informed the subjects of the general purpose of the study, the fact that it the survey was voluntary, who to contact if they had any questions or complaints and that participation/nonparticipation did not jeopardize their care or employment at their institution. It also reassured all participants of the anonymity of the survey participation. If they did not wish to participate, they could ignore the email, if they wished to participate; they would follow the link at the bottom of the email. All nonresponders received an email reminder 3 times before all correspondence ceased. There was no incentive to participate in this study.

Data Collection and Response Rate

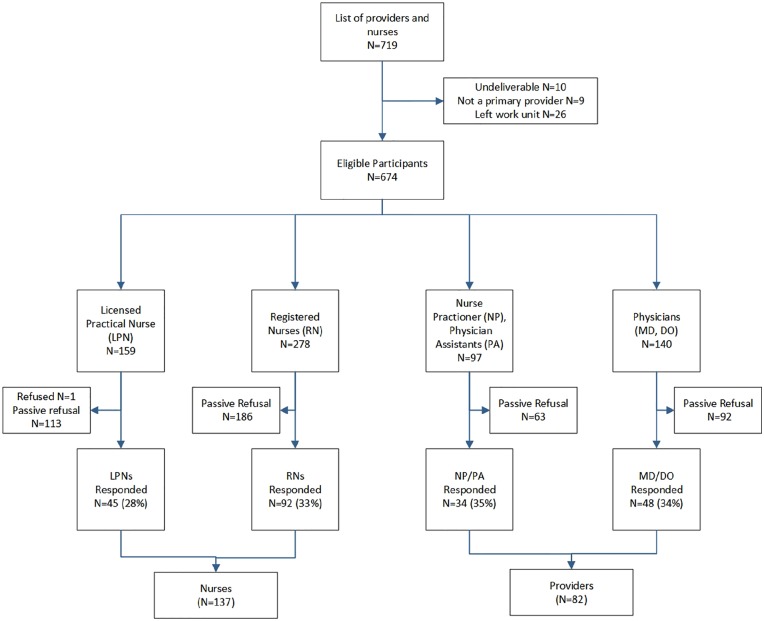

There were 719 PCPs and nurses identified for potential inclusion in the present study. Of these, 45 were excluded (10 had nonviable/incomplete email addresses, 9 were not PCPs (PhDs or other type of providers), and 26 had left the work unit. Among the 674 individuals who were surveyed, 437 (64.8%) were licensed nurses (159 were LPNs and 278 were RNs) and 237 (35.2%) were licensed PCPs (97 were NP or PA and 140 were MD or DO). For purposes of the present report nurses will refer to LPNs/RNs and PCPs will refer to NP/PA, MD/DO.

The initial survey was sent through email on October 15, 2018; the nonresponders received a reminder email with the survey attached on November 5, 2018; the final and third reminder email with attached survey was sent to non-responders on November 26, 2018. Study collection was closed on January 31, 2019. A detailed summary of the above is found in the consort diagram presented in Figure 1, which adheres to consort guidelines.21

Figure 1.

Participant flow in study from first study contact to last study contact.

Data Analysis

Baseline demographics and training background information provided by the responders are summarized for continuous variables using mean, standard deviation, minimum and maximum and for categorical variables using frequency percentages. These variables were calculated in total and for both groups: nurses and PCPs. A knowledge score with a potential value ranging from 0 to 5 was calculated for each individual as the sum of the number of correct responses to 5 questions pertaining to obesity assessment and treatment (see Appendix Table A2). Knowledge scores were compared between the job groups using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. All questions assessing respondent attitudes and behaviors were assessed using a 5-point Likert-type scale (ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree). For analysis purposes responses for “agree” and “strongly agree” were combined, as were the responses of “disagree” and “strongly disagree.” The resulting analysis variables had 3 levels (1 = agree, 0 = neutral, and −1 = disagree). An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used to describe the factor structure of the attitude and behavior questions. The EFA utilized promax rotation because of the possible correlated nature of the factors. Maximum likelihood was used as the extraction method. An initial scree plot and eigenvalue table indicated that a 4-factor model was most appropriate. In order to assess internal consistency Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for each factor. The 4 factors were then scored for each individual using average of the items which loaded on the given factor, with some items reversed score for consistency. Factor scores were compared between nurse and PCP groups using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. To supplement the analysis of the factor score, the individual questions were summarized using frequency percentages with the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare responses between groups. In all cases, a 2-tailed P value of less than .05 was considered significant. Statistical analysis was done using SAS statistical software, version 9.4.22

Results

Of the 674 surveys emailed, a total of 219 (32.3%) surveys were returned (137/437 (31.4%) from nurses and 82/237 (34.6%) from the licensed PCPs) (see Figure 1). Among those who responded to the survey, 85.8% were female, 93.6% were white non-Hispanic, 57.3% worked full time, 65.6% have worked in the same health care facility for 10 years or more, 59.6% were older than 40 years, 31.5% had a body mass index BMI of 25 to 29.9 kg/m2 and 28% had a BMI >30 kg/m2. These descriptive demographics are summarized for each of the job categories in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics.

| Total (N = 219), n (%) | Nurses (n = 137), n (%) | Primary Care Providers (n = 82), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 187 (85.8)a | 130 (95.6)a | 57 (69.5) |

| White, non-Hispanic | 205 (93.6)b | 128 (93.4)a | 77 (93.9)a |

| Patient contact: based on 40-hour week | a | a | |

| ≤49% | 38 (17.4) | 31 (22.6) | 7 (8.6) |

| 50% to 74% | 51 (23.4) | 24 (17.5) | 27 (33.3) |

| 75% to 100% | 125 (57.3) | 78 (56.9) | 47 (58.0) |

| Varies/supplemental | 4 (1.8) | 4 (2.9) | 0 (0) |

| Worked at the institution | |||

| <5 years | 45 (20.6) | 26 (19.0) | 19 (23.2) |

| 5-9 years | 31 (14.2) | 20 (14.6) | 11 (13.4) |

| 10-14 years | 40 (18.3) | 25 (18.2) | 15 (18.3) |

| 15-19 years | 38 (17.4) | 20 (14.6) | 18 (22.0) |

| 20-24 years | 14 (6.4) | 7 (5.1) | 7 (8.5) |

| ≥25 | 51 (23.3) | 39 (28.5) | 12 (14.6) |

| Current age | |||

| ≤30 years | 22 (10.1) | 17 (12.4) | 5 (6.1) |

| 31-40 years | 67 (30.6) | 36 (26.3) | 31 (37.8) |

| 41-50 years | 45 (20.6) | 24 (17.5) | 25 (30.5) |

| 51-60 years | 63 (28.8) | 50 (36.5) | 13 (15.9) |

| ≥60 years | 22 (10.1) | 10 (7.3) | 12 (14.6) |

| Body mass index range | |||

| <25 kg/m2 | 69 (31.5) | 30 (21.9) | 39 (47.6) |

| 25-29.9 kg/m2 | 69 (31.5) | 41 (29.9) | 28 (34.1) |

| 30-34.9 kg/m2 | 40 (18.3) | 31 (22.6) | 9 (11.0) |

| 35-39.9 kg/m2 | 17 (7.8) | 14 (10.2) | 3 (3.7) |

| 40-45.9 kg/m2 | 4 (1.8) | 4 (2.9) | 0 (0) |

| ≥46 kg/m2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Don’t know | 20 (9.1) | 17 (12.4%) | 3 (3.7%) |

Data were missing for 1 respondent.

Data were missing for 2 respondents.

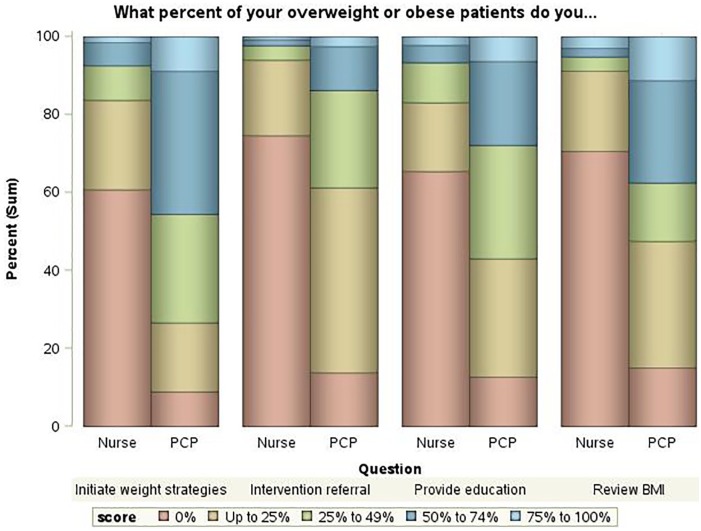

The results of knowledge scores and questions pertaining to weight management training are shown in Table 2. The percentage of respondents who responded correctly to all 5 knowledge questions was highest for the PCPs. A statistically significant difference in knowledge scores was found between the 2 groups (Wilcoxon rank-sum test P < .001). The questions relating to types of training that the participants had been involved in showed consistent trends of nurses receiving less training than PCPs, even though all groups showed high levels of interest in further training. Figure 2 shows the reported frequency of performing various interventions with overweight or obese patients according to job group. In all cases, nurses were significantly less likely to report providing the given intervention compared with PCPs (P < .001).

Table 2.

Training and Knowledge Score Results: Scale of 0 to 5, With 5 Equal to All Questions Answered Correctly.

| Total (N = 219) | Nurses (n = 137) | Primary Care Providers (N = 82) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge score, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 5 (2.2) | 4 (2.9) | 1 (1.2) |

| 1 | 24 (11.0) | 22 (16.1) | 2 (2.4) |

| 2 | 24 (11.0) | 21 (15.3) | 3 (3.7) |

| 3 | 41 (18.7) | 27 (19.7) | 14 (17.1) |

| 4 | 75 (34.3) | 43 (31.4) | 32 (39.0) |

| 5 | 50 (22.8) | 20 (14.6) | 30 (36.6) |

| Median (25, 75) | 4.0 (3, 4) | 3.0 (2, 4) | 4.0 (4, 5) |

| Mean ± SD | 3.40 ± 1.36 | 3.04 ± 1.40 | 4.00 ± 1.05 |

| Pa | <.001 | ||

| During medical training, did you have any special training in weight management | b | ||

| Yes | 18 (8.4) | 7 (5.2) | 11 (13.6) |

| No | 174 (80.9) | 112 (83.6) | 62 (76.5) |

| Don’t remember | 23 (10.7) | 15 (11.2) | 8 (9.9) |

| Since your medical training, have you had any special training in weight management | c | ||

| Yes, n (%) | 65 (29.8) | 24 (17.6) | 41 (50.0) |

| Types of training (can choose more than one) | |||

| Lectures | 37 (17.9) | 9 (6.6) | 28 (34.1) |

| Classes | 19 (8.7) | 13 (9.5) | 6 (7.3) |

| Conferences | 43 (19.6) | 13 (9.5) | 30 (36.6) |

| Workshops | 9 (4.1) | 5 (3.6) | 4 (4.9) |

| Fellowship training | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Rotations | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) |

| Would be interested in further training, n (%) | 167 (77.3)d | 108 (79.4) | 59 (73.8) |

Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare knowledge scores between nurses and primaryc are providers (PCPs).

Data are missing for 4 respondents (3 nurses, 1 PCP).

Data are missing for 1 respondent (1 nurse).

Data are missing for 3 respondents (1 nurse, 2 PCPs).

Figure 2.

Percent of time spent with overweight/obese patients addressing . . . PCP, primary care provider.

Results of the exploratory factor analysis of questions related to the 4 major factors are shown in Table 3. The 4 factors are labeled opportunity and practices, knowledge and confidence, attitudes, and beliefs. Survey questions that load above 0.3 were considered to be grouped within that factor. The Cronbach alpha showed that the factors had high internal consistency. Answers for all questions that loaded within a factor were added together for each subject and then the average score for each group was found. As seen in Table 4, belief scores were extremely high for both nurses and PCPs (0.99 ± 0.06 vs 0.97 ± 0.23, P = .30), indicating that nearly all respondents believed obesity to be a major health problem. The attitudes scores were similar for nurses and PCPs (−0.61 ± 0.38 vs −0.59 ± 0.37, P = .49) with the average scores indicating that in general respondents do not endorse negative attitudes about patients who have overweight or obesity, however for both groups there was evidence of some unconscious bias;, for example 7.3% of nurses and 17.3% of PCPs agreed with the statement “obese patients lack motivation for lifestyle changes” (see Appendix Table A3). The opportunity and practices score was lower for PCPs than for nurses (−0.35 ± 0.44 vs −0.17 ± 0.41, P < .001) with PCPs more likely to say that they lacked the time to discuss weight and they worried it would cause a poor patient-PCP relationship. The knowledge and confidence score also differed significantly between the groups, with nurses feeling less equipped to deal with weight management issues than PCPs (−0.42 ± 0.43 vs −0.03 ± 0.55, P < .001). Neither group was very confident, with those in the PCP group only answering with an average score of neutral. The responses to each individual question used in the survey are found in Appendix Tables A1-A5.

Table 3.

Factor Pattern.a

| Opportunity and Practices | Knowledge and Confidence | Attitudes | Beliefs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Practice is too busy to treat weight management | 0.72 | |||

| Can handle treating comorbidities, but not lifestyle issues | 0.64 | |||

| Not comfortable initiating conversation | 0.60 | |||

| Most patients with obesity live in denial, so I give general advice | 0.60 | |||

| Afraid of creating poor provider-patient dynamic by bringing up weight | 0.58 | |||

| Few methods are effective at maintaining weight loss, so I give general advice | 0.55 | |||

| Obesity is complex condition, so I prefer focus on treating comorbidities | 0.46 | |||

| Feel comfortable discussing weightb | 0.44 | |||

| Duty to discuss weight, but long-term follow-up is outside capacity in busy practice | 0.43 | |||

| Afraid to make patient feel guilty | 0.36 | |||

| More difficulty discussing obesity than sexuality | 0.36 | |||

| Difficult to charge fees for suggesting simple changes in diet and exercise | 0.34 | |||

| Know how to treat obese patients | 0.80 | |||

| Feel trained enough to intervene | 0.76 | |||

| Lack specialty skills to properly address problemb | 0.61 | |||

| Know how to screen for eating disorders | 0.50 | |||

| Confident assessing and managing eating disorders | 0.45 | |||

| Taking care of obese patients requires specific trainingb | 0.32 | |||

| More irritated treating obese patients | 0.85 | |||

| Disgust when treating obese patients | 0.79 | |||

| Difficult to feel empathy for obese patients | 0.49 | |||

| Obese patients lack motivation for lifestyle changes | 0.43 | |||

| Healthier to be underweight than overweight | 0.41 | |||

| Dislike treating obese patients | 0.39 | |||

| Treating obese patients is rewardingb | 0.37 | |||

| Obesity is a health problem | 1.00 | |||

| Obesity itself is mortality risk factor | 0.74 | |||

| Obesity leads to serious med complications | 0.70 | |||

| Standardized Cronbach’s alpha | 0.82 | 0.77 | 0.78 | 0.86 |

Factor loadings are presented from exploratory factor analysis with promax rotation, extraction method = maximum likelihood.

Scale reversed.

Table 4.

Factor Scores.a

| Nurse |

Primary Care Provider |

P b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Min, Max | Mean ± SD | Min, Max | ||

| Opportunity and practices | −0.17 ± 0.41 | −1, 0.75 | −0.35 ± 0.44 | −1, 0.83 | <.001 |

| Knowledge and confidence | −0.42 ± 0.43 | −1, 1 | −0.03 ± 0.55 | −1, 1 | <.001 |

| Attitudes | −0.61 ± 0.38 | −1, 0.86 | −0.59 ± 0.37 | −1, 0.57 | .49 |

| Beliefs | 0.99 ± 0.06 | 0.33, 1 | 0.97 ± 0.23 | −1, 1 | .30 |

On scale of −1 = disagree, 0 = neutral, 1 = agree. Average factor score was taken for each subject, and then an average score was calculated for each group.

Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Discussion

We analyzed data from 219 PCPs and nurses practicing within a community health system who responded to a survey concerning weight management. Resulting data showed that PCPs and nurses felt they needed more training on how to deal with patients’ overweight and obesity issues irrespective the amount of prior training received in weight management. In addition, PCPs indicated 2 barriers: lack of time to discuss and/or fear of creating a poor patient-PCP relationship. While both PCPs and nurses agreed that they were not comfortable initiating discussion, nurses expressed higher level of discomfort. Nurses also felt less equipped compared with PCPs in dealing with weight management issues due to lack of training, inadequate specialty skills and/or they did not wish to harm the patient-PCP relationship. In an analysis of the reported duration of time spent with patients in weight management intervention/discussion (Figure 2), it appears that nurses are under-utilized in helping patients with weight management, which may partly explain why nurses reported lower confidence in assessment and intervention.

The findings from our survey are consistent with results from past surveys where physicians (ie, PCPs) cited similar reasons for not delivering weight management in their practices, which included insufficient time,23 insufficient training, and poor knowledge of the tools needed to diagnose and treat obesity.24-27 There are multiple prior surveys of PCPs that have demonstrated that provider weight bias and stigma exist.28-35 In our survey, the overall average response did not indicate a negative bias toward overweight or obese patients; however, approximately 5% of responders indicated that they were more irritated treating obese/overweight patients and over 10% indicated that obese overweight patients lacked motivation for lifestyle changes. It should also be noted that overall the respondents did indicate a lack of comfort with their skill level, lack of time, and concern about placing patients at a discomfort level or initiating feelings of guilt which reflect awareness of bias and stigma associated with obesity. Bias and stigma associated with obesity may be improving with time36 and that is possibly why our levels were low. Further longitudinal studies of stigma and bias are needed. Bias, stigma as well as pessimism about weight-loss success28,29,31,37,38 can all contribute negatively to patient care.39

Some of the cited reasons why some PCPs prefer not to initiate a discussion on weight management include lack of competence on overweight and obesity care stemming from lack of training,4,20 concern about possible negative consequences elicited by introducing the topic to patients during a consultation, time constraints,4,20 and limited resources to raise the sensitive topic,40 especially if overweight and obesity are not the presenting complaint in a given consultation.41 These reasons were echoed by the PCPs and nurses surveyed in this study. Consequently, there was also reported hesitancy among PCPs who indicated that they would not bring up the topic of weight management with their patients unless their patient brings it up first while patients felt that it is their PCPs responsibility to initiate the discussion.42-45 In other cases, some patients had expressed frustration and anger when the PCP attributed all their presenting complaints to their weight.46 This was corroborated by patients who had self-reported lower confidence in their PCPs’ adequacy of necessary skills to help them with their weight management.14 All these data support the presence of unmet need among PCPs for further training in the art of conversation with patients on sensitive topics such as those that revolve around weight, an observation which is corroborated by results from this survey where our PCPs and nurses have indicated that they would welcome additional training in weight management regardless of the amount of past training.

This consistent theme of inadequate training in obesity management was observed at early learning levels. A study that looked into nursing students’ perception on obesity found that nursing curriculum lacked educational modules on obesity, and advanced communication skills training which led to lack of confidence and technical competence in weight management.47 These nurses-in-training felt ill-equipped in their training and experience to address obesity: They lacked exposure to patients who were overweight or obese and were not taught strategies to facilitate behavior change and special communication skills to tackle sensitive health issues.39 In a study of medical students, it had been shown that weight bias, including negative attitudes that patients with obesity are lazy, noncompliant with treatment, less responsive to counseling, responsible for their condition, have no willpower, and deserve to be targets of derogatory humor, even in the clinical care environment48,49 led to the opinion that treatment would be futile50 and feelings of discomfort around patients with obesity, and decreased likelihood of initiating any conversation concerning weight management51; all of which contribute to failure in delivering appropriate health care. In another study done across medical schools in Norway, that compared senior medical students’ knowledge on obesity to first-year medical students, knowledge gap was still seen among the senior students, with in understanding obesity, particularly with regard to etiology, diagnosis, and treatment, despite a significant improvement in obesity knowledge during the course of medical education. Responses to a knowledge/opinion survey showed negative attitudes toward time-consuming follow-up, treatment outcomes, and confidence in weight management; where the majority of final-year students perceived themselves as competent in treating patients with obesity, did not have the confidence, time, resources, and capacity to commit to long-term follow-up for patients with obesity.20

On the flip side, in an earlier study of 586 nurses, nurses had confidence in their ability to give weight loss advice, but did not have high expectations that the patient would be compliant nor would that they would lose weight, justifying their skill level as separate from the outcome.52 Rather than believing that the poor outcome may be due to lack of skill in the advice giving, they preferred to believe that the failed outcome would be due to patient poor motivation and noncompliance. This may imply bias and while a discussion of stigma associated with obesity is beyond the scope of this article, observations such as this provide valuable insight on training focus.

Indeed, well-structured training would greatly benefit PCPs and nurses, and training programs should emphasize the potential impact that language has when discussing obesity with patients; addressing any negative emotional effect of the PCPs’ language should be first and foremost. These can start with clear guidelines on the terminology and the communication styles that should be used as a way to initiate the educational focus on eliminating any unconscious acceptable form of prejudice/bias toward patients who are overweight or obese.17,53 The program must include not just skills training but also awareness of the factors involved in both advice giving and self-appraisal.52 Curricula that emphasize building skills in behavior change counseling techniques, with the opportunity to practice, engage patients, and receive feedback to hone counseling skills, are likely to improve clinician confidence in counseling and thus increase the likelihood of providing counseling on a routine basis.19 This was corroborated by a study of medical students where it was found that factors associated with high self-competence included increased interaction with peers with obesity (39% vs 49%, P < .001) and increased partnership skills training (32% vs 61%, P < .001).54 In one prime example of the impact education had in practice, Busch et al5 found that an educational program to PCPs improved detection, documentation and follow-up/referral of pediatric obesity and comorbid conditions by improving appropriate laboratory studies and referrals for patients with overweight by 10%.

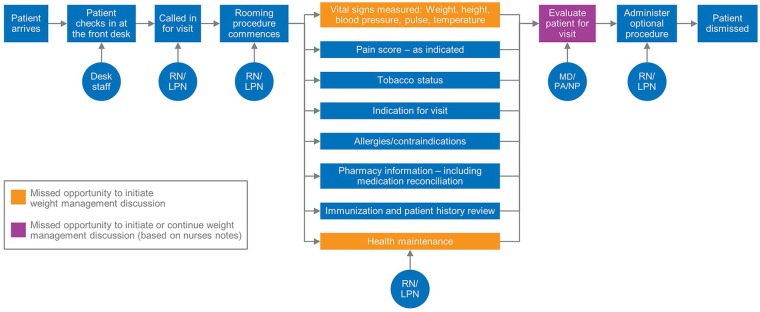

While appropriate training is essential, identifying opportunities when discussion can be initiated with patient is equally important. Figure 3 illustrates a breakdown of a hypothetical current practice with 3 prime points where initiating and reinforcing a weight management conversation is possible, within the health practice. The first two could be an opportunity for the nurse to intervene: taking the vitals, which includes weight and BMI recording in the electronic medical record, and the health maintenance discussion. The next opportunity is with the PCP, when they come in for the health visit with the patient. If the nurse has already initiated the conversation and the patient seems amenable to continuing the conversation, it will be noted in the charts and the PCP can continue the conversation. This allows for 3 opportunities to intervene, which are now areas for growth within a clinical care practice.

Figure 3.

Opportunities for growth with a clinical practice. LPN, licensed practical nurse; RN, registered nurse; PA, physician assistant; NP, nurse practitioners; MD, medical doctor.

Our study was unique in that we recorded responses across the professional HCP spectrum and not just in PCPs. Our study had a 32.3% return rate, which is high for an online survey distributed during the holiday season, when the practice is at its peak. The 32.3% is larger than other comparable survey studies completed among health care PCPs, which have varied from 11% to 30%,10,55-58 but lower for other studies which either used multiple targeted mailings during the spring months or monetary incentives and had a return range of 53% to 77%.4,30 Limitations of this study include the fact that it is limited to one health care system, which limits generalizability of the findings. Given our response rate, our analysis was performed using a convenience sample which may have been influenced by unmeasurable nonresponse bias. Another limitation is that although we surveyed all PCPs and nurses within a community practice in one health care practice, our respondents were predominantly non-Hispanic white (93.6%) and female (85.8%). Despite the uniformity of the race and ethnicity of our population, the self-reported experiences and attitudes are similar to those identified by study samples of differing race.23-27 Finally, the results of the factor analysis and the 4 resulting scale scores were used for analysis purposes in the present study. These scales should not be viewed as fully validated for use in future studies.

Conclusion

This self-reported survey of PCPs, NPs, PAs, LPNs, and RNs found that past training in weight management received by HCPs are inadequate; more is needed and requested by those in practice. Within our health care practice, our PCPs and nurses did not endorse any negative attitudes about patients with overweight or obesity. They recognized that obesity is a major health problem; they wanted to do more but did not feel they have the skill to address this issue adequately. This survey has identified potential areas of growth—more educational training to our PCPs and nurses in weight management and allowing our practice nurses to lead the charge on initiating the discussion concerning weight management among patients with overweight and obesity issues.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, jpc-19-0087 for Identifying Opportunities for Advancing Weight Management in Primary Care by Ivana T. Croghan, Jon O. Ebbert, Jane W. Njeru, Tamim I. Rajjo, Brian A. Lynch, Ramona S. DeJesus, Michael D. Jensen, Karen M. Fischer, Sean Phelan, Tara K. Kaufman, Darrell R. Schroeder, Lila J. Finney Rutten, Sarah J. Crane and Sidna M. Tulledge-Scheitel in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Dr Robert Jacobson and Dr Thomas Thacher, for the endless support and advice during the entire study process. Finally, a special thanks to all the survey participants who took the time to complete this survey. Without their participation, this study would not have been possible.

Appendix

Table A1.

Opportunity and Practices.a

| Nurse |

Primary Care Provider |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Missing | P b | |

| Practice is too busy to treat weight management | 18 (13.7) | 63 (48.1) | 50 (38.2) | 13 (16.9) | 28 (36.4) | 36 (46.8) | 11 | .48 |

| Can handle treating comorbidities, but not lifestyle issues | 17 (13.1) | 78 (60.0) | 35 (26.9) | 16 (20.0) | 25 (31.3) | 39 (48.8) | 9 | .07 |

| Not comfortable initiating conversation | 35 (27.1) | 50 (38.8) | 44 (34.1) | 6 (7.5) | 15 (18.8) | 59 (73.8) | 10 | <.001 |

| Most patients with obesity live in denial, so I give general advice | 9 (6.8) | 49 (37.1) | 74 (56.1) | 4 (5.0) | 17 (21.3) | 59 (73.8) | 7 | .01 |

| Afraid of creating poor provider-patient dynamic by bringing up weight | 26 (19.9) | 61 (46.6) | 44 (33.6) | 20 (25.3) | 14 (17.7) | 45 (57.0) | 9 | .05 |

| Few methods are effective at maintaining weight loss, so I give general advice | 14 (10.7) | 58 (44.3) | 59 (45.0) | 17 (21.3) | 20 (25.0) | 43 (53.8) | 8 | .79 |

| Obesity is complex condition, so I prefer focus on treating comorbidities | 15 (11.2) | 76 (56.7) | 43 (32.1) | 11 (13.8) | 23 (28.8) | 46 (57.5) | 5 | .006 |

| Feel comfortable discussing weight | 61 (45.2) | 46 (34.1) | 28 (20.7) | 58 (71.6) | 16 (19.8) | 7 (8.6) | 3 | <.001 |

| Duty to discuss weight, but long term follow-up is outside capacity in busy practice | 29 (22.1) | 62 (47.3) | 40 (30.5) | 30 (37.5) | 22 (27.5) | 28 (35.0) | 8 | .35 |

| Afraid to make patient feel guilty | 68 (50.4) | 28 (20.7) | 39 (28.9) | 34 (42.0) | 15 (18.5) | 32 (39.5) | 3 | .14 |

| More difficulty discussing obesity than sexuality | 27 (19.9) | 50 (36.8) | 59 (42.4) | 8 (9.9) | 20 (24.7) | 53 (65.4) | 2 | .002 |

| Difficult to charge fees for suggesting simple changes in diet and exercise | 13 (9.8) | 95 (71.4) | 25 (18.8) | 30 (37.5) | 14 (17.5) | 36 (45.0) | 6 | .88 |

Values are given as number (%).

Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Table A2.

Knowledge and Confidence.a

| Nurse |

Primary Care Provider |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Missing | P b | |

| Know how to treat obese patients | 13 (9.9) | 65 (49.2) | 54 (40.9) | 39 (48.8) | 24 (30.0) | 17 (21.3) | 7 | <.001 |

| Feel trained enough to intervene | 19 (14.2) | 57 (42.5) | 58 (43.3) | 43 (53.1) | 23 (28.4) | 15 (18.5) | 4 | <.001 |

| Lack specialty skills to properly address problem | 62 (48.4) | 52 (40.6) | 14 (10.9) | 29 (36.3) | 22 (27.5) | 29 (36.3) | 11 | .002 |

| Know how to screen for eating disorders | 9 (6.8) | 29 (22.0) | 94 (71.2) | 22 (27.2) | 25 (30.9) | 34 (42.0) | 6 | <.001 |

| Confident assessing and managing eating disorders | 16 (11.8) | 47 (34.6) | 73 (53.7) | 12 (14.6) | 30 (36.6) | 40 (48.8) | 1 | .44 |

| Taking care of obese patients requires specific training | 80 (59.7) | 39 (29.1) | 15 (11.1) | 41 (50.6) | 20 (24.7) | 20 (24.7) | 4 | .06 |

Values are given as number (%).

Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Table A3.

Attitudes.a

| Nurse |

Primary Care Provider |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Missing | P b | |

| More irritated treating obese patients | 6 (4.4) | 32 (23.4) | 99 (72.3) | 5 (6.3) | 18 (22.5) | 57 (71.3) | 2 | .82 |

| Disgust when treating obese patients | 2 (1.5) | 29 (21.2) | 106 (77.4) | 0 (0) | 11 (13.6) | 70 (86.4) | 1 | .10 |

| Difficult to feel empathy for obese patients | 8 (5.8) | 23 (16.8) | 106 (77.4) | 4 (4.9) | 12 (14.8) | 65 (80.3) | 1 | .62 |

| Obese patients lack motivation for lifestyle changes | 10 (7.3) | 34 (24.8) | 93 (67.9) | 14 (17.3) | 19 (23.5) | 48 (59.3) | 1 | .10 |

| Healthier to be underweight than overweight | 12 (8.8) | 30 (21.9) | 95 (69.3) | 8 (9.8) | 26 (31.7) | 48 (58.5) | 0 | .14 |

| Dislike treating obese patients | 5 (3.7) | 34 (24.8) | 98 (71.5) | 4 (4.9) | 23 (28.4) | 54 (66.7) | 1 | .44 |

| Treating obese patients is rewarding | 39 (28.9) | 87 (64.4) | 9 (6.7) | 35 (44.3) | 37 (46.8) | 7 (8.9) | 5 | .08 |

Values are given as number (%).

Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Table A4.

Beliefs.a

| Nurse |

Primary Care Provider |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Missing | P b | |

| Obesity is a health problem | 136 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 81 (98.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) | 1 | .20 |

| Obesity leads to serious med complications | 134 (99.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) | 81 (98.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) | 2 | .73 |

| Obesity itself is mortality risk factor | 134 (99.3) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 77 (96.3) | 2 (2.5) | 1 (1.3) | 4 | .12 |

Values are given as number (%).

Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Table A5.

Questions That Did Not Load Into Factors.a

| Nurse |

Primary Care Provider |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Missing | P b | |

| Every visit appropriate time to discuss weight | 65 (47.8) | 29 (21.3) | 42 (30.9) | 45 (56.3) | 14 (17.5) | 21 (26.3) | 3 | .27 |

| Easier to help patient stop smoking than to help lose weight | 33 (24.3) | 56 (41.1) | 47 (34.6) | 34 (42.0) | 20 (24.7) | 27 (33.3) | 2 | .10 |

| Health promotion is a priority in my area | 99 (73.9) | 25 (18.7) | 10 (7.5) | 69 (85.2) | 9 (11.1) | 3 (3.7) | 4 | .05 |

| Prefer to refer to specialty health services | 24 (18.6) | 80 (62.0) | 25 (19.4) | 18 (22.5) | 27 (33.8) | 35 (43.8) | 10 | .03 |

Values are given as number (%).

Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: All the authors participated in the study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting and revising the paper, and have seen and approved the final version of the manuscript.

ITC conceived of the study concept and design; obtained funding and provided administrative, technical, and material support; had full oversight of the study conduct during data collection; had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis; and also drafted the manuscript and participated in critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

JOE, JWN, TIR, BAL, MDJ, SP, RSD, TKK, LJF, SJC, SMT participated in the study design, review and editing of the protocol and survey and participated in the safety and ethics oversight of the study subjects while on study. They also participated in the review and interpretation of study results, and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

KF and DRS participated in the study design and was responsible for data quality checks and data analysis; he also had full access to all the data in the study and takes full responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis as well as participating in the manuscript reviews and edits.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported in part by our Institution. The data entry system used was RedCap, supported in part by the Center for Clinical and Translational Science award (UL1 TR000135) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS).

Ethics and Consent to Participate: In accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, this study was reviewed and determined to be exempt (ID 18-007792) by the Institutional Review Board (IRB). The IRB-approved passive consent was obtained for all study participants prior to study participation.

Ethical Standards: This study was reviewed by expedited process and determined to be EXEMPT from the requirement for Institutional Review Board Approval under 45 CFR 46.101b, item 2. All modifications to the study design or procedures continued to be submitted to the IRB during the study for determination on whether the study continued to be exempt. The oral contact cover letter (which served as the passive consent) and the survey were both reviewed by the IRB and noted. Passive consent was obtained from all study participants prior to study initiation.

ORCID iDs: Ivana T. Croghan  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3464-3525

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3464-3525

Brian A. Lynch  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4155-7182

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4155-7182

References

- 1. Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Obesity Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 pt B):2985-3023. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Decision memo for intensive behavioral therapy for obesity (CAG-00423N). https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?&NcaName=Intensive%20Behavioral%20Therapy%20for%20Obesity&bc=ACAAAAAAIAAA&NCAId=253&. Accessed April 12, 2018.

- 3. Walsh K, Grech C, Hill K. Health advice and education given to overweight patients by primary care doctors and nurses: a scoping literature review. Prev Med Rep. 2019;14:100812. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2019.01.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Petrin C, Kahan S, Turner M, Gallagher C, Dietz WH. Current attitudes and practices of obesity counselling by health care providers. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2017;11:352-359. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2016.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Busch AM, Hubka A, Lynch BA. Primary care provider knowledge and practice patterns regarding childhood obesity. J Pediatr Health Care. 2018;32:557-563. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2018.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tsai AG, Abbo ED, Ogden LG. The time burden of overweight and obesity in primary care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:191. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for obesity in adults: recommendations and rationale. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:930-932. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-11-200312020-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wadden TA, Volger S, Sarwer DB, et al. A two-year randomized trial of obesity treatment in primary care practice. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1969-1979. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Koball AM, Mueller PS, Craner J, et al. Crucial conversations about weight management with healthcare providers: patients’ perspectives and experiences. Eat Weight Disord. 2018;23:87-94. doi: 10.1007/s40519-016-0304-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Torre SBD, Courvoisier DS, Saldarriaga A, Martin XE, Farpour-Lambert NJ. Knowledge, attitudes, representations and declared practices of nurses and physicians about obesity in a university hospital: training is essential. Clin Obes. 2018;8:122-130. doi: 10.1111/cob.12238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Turner M, Jannah N, Kahan S, Gallagher C, Dietz W. Current knowledge of obesity treatment guidelines by health care professionals. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2018;26:665-671. doi: 10.1002/oby.22142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wadden TA, Butryn ML, Hong PS, Tsai G. Behavioral treatment of obesity in patients encountered in primary care settings: a systematic review. JAMA. 2014;312:1779-1791. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.14173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Croghan IT, Huber JM, Hurt RT, et al. Patient perception matters in weight management. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2018;19:197-204. doi: 10.1017/S1463423617000585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Croghan IT, Phelan SM, Bradley DP, et al. Needs assessment for weight management: the learning health system network experience. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2018;2:324-335. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2018.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Teixeira FV, Pais-Ribeiro JL, Maia AR. Beliefs and practices of healthcare providers regarding obesity: a systematic review. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992). 2012;58:254-262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bleich SN, Bennett WL, Gudzune KA, Cooper LA. National survey of US primary care physicians’ perspectives about causes of obesity and solutions to improve care. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e001871. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wynn T, Islam N, Thompson C, Myint KS. The effect of knowledge on healthcare professionals’ perceptions of obesity. Obes Med. 2018;11:20-24. doi: 10.1016/j.obmed.2018.06.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Buffart LM, Allman-Farinelli M, King LA, et al. Are general practitioners ready and willing to tackle obesity management? Obes Res Clin Pract. 2008;2:I-II. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2008.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Antognoli EL, Seeholzer EL, Gullett H, Jackson B, Smith S, Flocke SA. Primary care resident training for obesity, nutrition, and physical activity counseling: a mixed-methods study. Health Promot Pract. 2017;18:672-680. doi: 10.1177/1524839916658025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Martins C, Norsett-Carr A. Obesity knowledge among final-year medical students in Norway. Obes Facts. 2017;10:545-558. doi: 10.1159/000481351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. CONSORT. The CONSORT flow diagram. http://www.consort-statement.org/consort-statement/flow-diagram. Accessed August 2016.

- 22. SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT User’s Guide—Version 9.4. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kushner RF. Barriers to providing nutrition counseling by physicians: a survey of primary care practitioners. Prev Med. 1995;24:546-552. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1995.1087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999-2008. JAMA. 2010;303:235-241. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Forman-Hoffman V, Little A, Wahls T. Barriers to obesity management: a pilot study of primary care clinicians. BMC Fam Pract. 2006;7:35. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-7-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vetter ML, Herring SJ, Sood M, Shah NR, Kalet AL. What do resident physicians know about nutrition? An evaluation of attitudes, self-perceived proficiency and knowledge. J Am Coll Nutr. 2008;27:287-298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jay M, Gillespie C, Ark T, et al. Do internists, pediatricians, and psychiatrists feel competent in obesity care? Using a needs assessment to drive curriculum design. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1066-1070. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0519-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Price JH, Desmond SM, Krol RA, Snyder FF, O’Connell JK. Family practice physicians’ beliefs, attitudes, and practices regarding obesity. Am J Prev Med. 1987;3:339-345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Huizinga MM, Cooper LA, Bleich SN, Clark JM, Beach MC. Physician respect for patients with obesity. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:1236-1239. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1104-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ferrante JM, Piasecki AK, Ohman-Strickland PA, Crabtree BF. Family physicians’ practices and attitudes regarding care of extremely obese patients. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2009;17:1710-1716. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Steeves JA, Liu B, Willis G, Lee R, Smith AW. Physicians’ personal beliefs about weight-related care and their associations with care delivery: the US National Survey of Energy Balance Related Care Among Primary Care Physicians. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2015;9:243-255. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2014.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Epling JW, Morley CP, Ploutz-Snyder R. Family physician attitudes in managing obesity: a cross-sectional survey study. BMC Res Notes. 2011;4:473. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Salinas GD, Glauser TA, Williamson JC, Rao G, Abdolrasulnia M. Primary care physician attitudes and practice patterns in the management of obese adults: results from a national survey. Postgrad Med. 2011;123:214-219. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2011.09.2477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jay M, Kalet A, Ark T, et al. Physicians’ attitudes about obesity and their associations with competency and specialty: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:106. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schwartz MB, Chambliss HO, Brownell KD, Blair SN, Billington C. Weight bias among health professionals specializing in obesity. Obes Res. 2003;11:1033-1039. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Budd GM, Mariotti M, Graff D, Falkenstein K. Health care professionals’ attitudes about obesity: an integrative review. Appl Nurs Res. 2011;24:127-137. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2009.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kristeller JL, Hoerr RA. Physician attitudes toward managing obesity: differences among six specialty groups. Prev Med. 1997;26:542-549. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1997.0171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Huang J, Yu H, Marin E, Brock S, Carden D, Davis T. Physicians’ weight loss counseling in two public hospital primary care clinics. Acad Med. 2004;79:156-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dietz WH, Baur LA, Hall K, et al. Management of obesity: improvement of health-care training and systems for prevention and care. Lancet. 2015;385:2521-2533. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61748-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Blackburn M, Stathi A, Keogh E, Eccleston C. Raising the topic of weight in general practice: perspectives of GPs and primary care nurses. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e008546. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mkhatshwa VB, Ogunbanjo GA, Mabuza LH. Knowledge, attitudes and management skills of medical practitioners regarding weight management. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2016;8:e1-e9. doi: 10.4102/phcfm.v8i1.1187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Swift JA, Choi E, Puhl RM, Glazebrook C. Talking about obesity with clients: preferred terms and communication styles of UK pre-registration dieticians, doctors, and nurses. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;91:186-191. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Thomas SL, Hyde J, Karunaratne A, Herbert D, Komesaroff PA. Being “fat” in today’s world: a qualitative study of the lived experiences of people with obesity in Australia. Health Expect. 2008;11:321-330. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2008.00490.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gray CM, Hunt K, Lorimer K, Anderson AS, Benzeval M, Wyke S. Words matter: a qualitative investigation of which weight status terms are acceptable and motivate weight loss when used by health professionals. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:513. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tham M, Young D. The role of the general practitioner in weight management in primary care—a cross sectional study in general practice. BMC Fam Pract. 2008;9:66. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-9-66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ward SH, Gray AM, Paranjape A. African Americans’ perceptions of physician attempts to address obesity in the primary care setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:579-584. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0922-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Keyworth C, Peters S, Chisholm A, Hart J. Nursing students’ perceptions of obesity and behaviour change: implications for undergraduate nurse education. Nurse Educ Today. 2013;33:481-485. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2012.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Swift JA, Hanlon S, El-Redy L, Puhl RM, Glazebrook C. Weight bias among UK trainee dietitians, doctors, nurses and nutritionists. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2013;26:395-402. doi: 10.1111/jhn.12019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wear D, Aultman JM, Varley JD, Zarconi J. Making fun of patients: medical students’ perceptions and use of derogatory and cynical humor in clinical settings. Acad Med. 2006;81:454-462. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000222277.21200.a1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Block JP, DeSalvo KB, Fisher WP. Are physicians equipped to address the obesity epidemic? Knowledge and attitudes of internal medicine residents. Prev Med. 2003;36:669-675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Pedersen PJ, Ketcham PL. Exploring the climate for overweight and obese students in a student health setting. J Am Coll Health. 2009;57:465-469. doi: 10.3200/JACH.57.4.471-480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hoppé R, Ogden J. Practice nurses’ beliefs about obesity and weight related interventions in primary care. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1997;21:141-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bardia A, Holtan SG, Slezak JM, Thompson WG. Diagnosis of obesity by primary care physicians and impact on obesity management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:927-932. doi: 10.4065/82.8.927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Doshi RS, Gudzune KA, Dyrbye LN, et al. Factors influencing medical student self-competence to provide weight management services. Clin Obes. 2019;9:e12288. doi: 10.1111/cob.12288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Anderson C, Peterson CB, Fletcher L, Mitchell JE, Thuras P, Crow SJ. Weight loss and gender: an examination of physician attitudes. Obes Res. 2001;9:257-263. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Bleich SN, Bandara S, Bennett WL, Cooper LA, Gudzune KA. US health professionals’ views on obesity care, training, and self-efficacy. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48:411-418. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zuzelo PR, Seminara P. Influence of registered nurses’ attitudes toward bariatric patients on educational programming effectiveness. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2006;37:65-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Granara B, Laurent J. Provider attitudes and practice patterns of obesity management with pharmacotherapy. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2017;29:543-550. doi: 10.1002/2327-6924.12481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, jpc-19-0087 for Identifying Opportunities for Advancing Weight Management in Primary Care by Ivana T. Croghan, Jon O. Ebbert, Jane W. Njeru, Tamim I. Rajjo, Brian A. Lynch, Ramona S. DeJesus, Michael D. Jensen, Karen M. Fischer, Sean Phelan, Tara K. Kaufman, Darrell R. Schroeder, Lila J. Finney Rutten, Sarah J. Crane and Sidna M. Tulledge-Scheitel in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health