Abstract

Many patients with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency have CAH-X syndrome, a connective tissue dysplasia consistent with hypermobility-type Ehlers-Danlos syndrome due to a contiguous gene deletion involving the adjacent CYP21A2 and TNXB genes. CAH-X syndrome is caused by carrying CYP21A1P-TNXA/TNXB chimeric genes [CAH-X chimera 1 (CH-1) and chimera 2 (CH-2)] on one or more alleles. Genetic analysis is cumbersome due to pseudogene interference. We developed a PCR-based CAH-X high-throughput screening method to assess the copy numbers of TNXB exons 35 and 40; this method is amenable to either real-time quantitative PCR or droplet digital PCR (ddPCR). The assay was validated in a cohort of 278 subjects from 146 unrelated CAH families. Results were confirmed by a validated Sanger sequencing platform. A total of 44 CAH-X–positive calls were made, with 42 (26 CH-1 and 16 CH-2) confirmed. The assay had 100% sensitivity (42 true/42 positives), 99.2% specificity (234 true/236 negatives), and an overall 99.3% accuracy (276/278). Calls made by real-time quantitative PCR and ddPCR were consistent (100%), and ddPCR offered easier data interpretation. The CAH-X prevalence was 15.6% (21/135 probands), higher than the previously estimated 8.5%, and was particularly high (29.2% or 21/72) in those with a 30-Kb deletion. This assay is suitable for high-throughput CAH-X screening, especially in subjects testing positive for CAH in neonatal screening.

Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) is a group of autosomal recessive disorders in steroidogenesis, with 95% of cases due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man number 201910). CAH is classified into three major subtypes according to clinical severity: two classic subtypes of salt-wasting and simple virilizing combined are estimated to occur in 1 in 15,000 live births,1 and a mild or late-onset, nonclassic subtype that is more common and affects 1 in 200 to 1 in 1000 Caucasians.2 Because severe salt-wasting CAH can be life-threatening if left without prompt treatment, CAH screening by a hormonal assay is part of the mandatory neonatal screening in the United States and approximately 40 other countries.3

The CYP21A2 gene (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man number 613815) encoding 21-hydroxylase is mapped at a locus of low copy repeats termed the RCCX module(s) (RP-C4-CYP21-TNX) in the human histocompatibility complex on chromosome 6 (p21.33). RP signifies RP1 (synonym for STK19) encoding a serine/threonine nuclear protein kinase and pseudogene RP2 (STK19P); C4 signifies C4A and C4B encoding two isotopes of complement component 4; CYP21 signifies CYP21A2 and a pseudogene CYP21A1P; and TNX signifies TNXB encoding tenascin-X and a pseudogene TNXA (Figure 1). These gene pairs are highly homologous; thus, the entire locus is vulnerable to unequal crossovers, leading to commonly existing RCCX copy number variation that is found in 14% to 17% of human alleles.4, 5, 6 Among them, chimeric genes of CYP21A1P/CYP21A2 and CYP21A1P-TNXA/TNXB, due to the recombination between respective CYP21 or TNX genes, are two major CAH-causing genotypes accounting for 30% of CAH-causing alleles.7 They are also termed 30-Kb deletions. CYP21A1P-TNXA/TNXB chimeras impair both the CYP21A2 and TNXB genes and are pathogenic for hypermobility type of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS; Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man number 130020).8, 9 The presence of both CAH and hypermobility-type EDS due to the contiguous deletion of CYP21A2 and TNXB is termed CAH-X syndrome. The CAH-X chimeras cause EDS in an autosomal dominant manner regardless of CAH status,10, 11, 12, 13 although patients with CAH usually have more severe EDS manifestations than do carriers without CAH. We previously found that 8.5% of patients with CAH due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency are affected by CAH-X.13

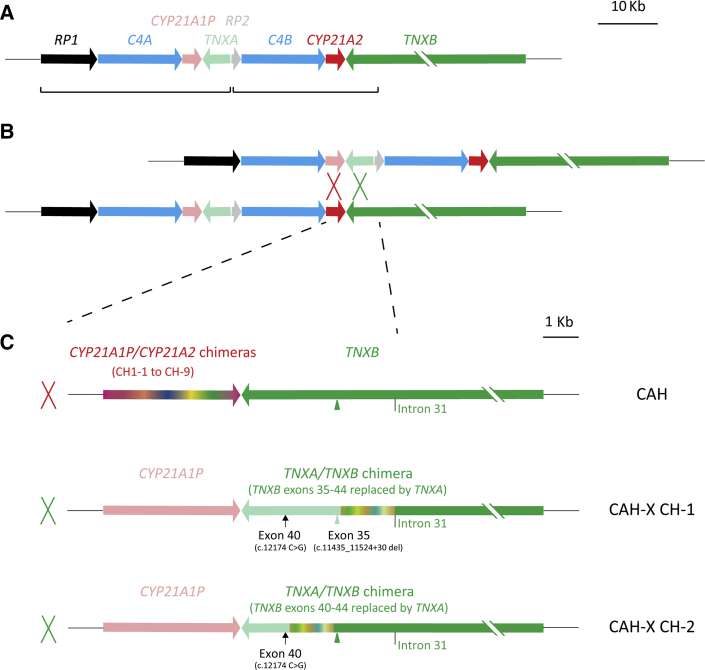

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) and CAH-X chimeric genes. A: Typical bimodular RCCX module: each pair of the homologous genes is shown in similar colors, with lighter colors representing pseudogenes; two RCCX units vulnerable for gene conversion are in brackets. B: Unequal crossover between CYP21A1P and CYP21A2 or TNXA and TNXB results in a commonly termed 30-Kb deletion CAH genotype. Dashed lines denote the window for unequal crossovers leading to CAH genotypes of 30-kb deletion. C: Schemes of three major subtypes of 30-Kb deletion: CYP21A1P/CYP21A2 chimeric genes with intact TNXB, pathogenic for CAH (top row); CYP21A1P-TNXA/TNXB chimera CAH-X CH-1 with TNXB exons 35–44 replaced by TNXA causes CAH-X due to tenascin-X haploinsufficiency (middle row); CYP21A1P-TNXA/TNXB chimera CAH-X CH-2 with TNXB exons 40-44 replaced by TNXA causes CAH-X due to a dominant negative effect (bottom row). CAH-X CH-1 has an exon 35 c.11435_11524+30 deletion (light green arrowhead) and an exon 40 c.12174 C>G mutation (arrow) in tandem, whereas CAH-X CH-2 has an intact exon 35 (green arrowhead) and an exon 40 c.12174 C>G mutation. The junction site window for each chimeric gene is shown in chameleonic colors. Schemes from CYP21A1P to TNXB intron 31, which is the boundary of RCCX module homologous repeats, are shown in scale. The size of TNXB is 68 Kb. CAH-X, a connective tissue dysplasia consistent with hypermobility-type Ehlers-Danlos syndrome due to a contiguous gene deletion involving the adjacent CYP21A2 and TNXB genes; CAH-X CH-1, CYP21A1P-TNXA/TNXB chimera with TNXB exons 35-44 replaced by TNXA; CAH-X CH-2, CYP21A1P-TNXA/TNXB chimera with TNXB exons 40-44 replaced by TNXA.

EDS is a group of genetic disorders of the connective tissue that affect approximately 1 in 5000 individuals.14 Five of the six major EDS types are associated with genes encoding collagens or collagen-modifying enzymes. Hypermobility-type EDS, the most common type of EDS, has been associated with TNXB defects, but the etiology is mostly unknown.9 The TNXB gene encodes tenascin-X, a large extracellular matrix–forming glycoprotein that is a crucial component of connective tissue and is found in the dermis, skeletal muscle, heart, and blood vessels.15 Although mutations throughout the TNXB gene have been reported to cause hypermobility-type EDS, CAH-X chimeras are most prevalent in CAH populations.9, 10, 12, 13, 16, 17, 18 Clinical EDS manifestation caused by CAH-X chimeras include joint hypermobility, frequent joint dislocations, skin laxity, tissue fragility, chronic myalgia, and cardiac malformations. A genetic test for the presence of CAH-X chimeras is mostly not available in clinical practice due to technical obstacles including pseudogene interference and the 70-Kb size of the TNXB gene. Currently, the diagnosis of CAH-X relies on clinical evaluation of joint hypermobility and subluxations; this type of evaluation is not reliably performed during infancy. Thus, infants who test positive for CAH based on neonatal screening are not screened for CAH-X.

To date, two major types of pathogenic CYP21A1P-TNXA/TNXB chimera have been identified: CAH-X chimera 1 (CH-1) has TNXB exons 35-44 replaced with TNXA, and CAH-X chimera 2 (CH-2) has TNXB exons 40-44 replaced with TNXA.8, 12, 13 The substitution of TNXB exon 35 by TNXA features a nonsense 120-bp deletion (c.11435_11524+30del) that is causative of tenascin-X haploinsufficiency in CAH-X CH-1, whereas the substitution of TNXB exon 40 by TNXA features two contiguous mutations of c.12150 C>G (synonymous) and c.12174 C>G (p.C4058W) in CAH-X CH-2, with the latter causing more severe EDS manifestations, likely due to a dominant negative effect.13 In addition, a third chimera, termed CAH-X CH-3 and having TNXB exons 41-44 substituted by TNXA, has been reported in one patient, and its significance is still under investigation.19 In this study, we focused on CAH-X CH-1 and CH-2 only.

Here we present an allele-specific PCR–based assay developed to efficiently screen for CAH-X. The assay determines the copy numbers of TNXB exons 35 and 40; CAH-X CH-1 is expected to have copy number losses in both exons 35 and 40, whereas CAH-X CH-2 is expected to have loss in only exon 40.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

A total of 278 subjects (145 patients, 118 carriers, and 1 unaffected relative from 135 unrelated families of CAH due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency; and 11 patients and 3 carriers from 11 unrelated families of other CAH types) were evaluated. All subjects were enrolled in an ongoing Natural History Study at the NIH Clinical Center (Bethesda, MD; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00250159). All subjects (and parents of subjects aged <18 years) gave written informed consent, and the study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Subjects were selected based on the availability of genomic DNA samples at the time of study.

Genetic Analysis

All subjects had previously completed comprehensive genetic analysis related to 21-hydroxylase deficiency at the time of study, including a targeted PCR-based CYP21A2 mutation analysis of 12 common CYP21A2 mutations and screening for the presence of a 30-Kb deletion based on 12 single-nucleotide polymorphic markers (Esoterix Laboratory Services, Calabasas Hills, CA). Samples testing positive for a 30-Kb deletion underwent a validated Sanger sequencing test to identify CYP21 chimeras (Prevention Genetics LLC, Marshfield, WI).7, 20 Patients with rarer forms of CAH underwent testing using commercially available platforms for other CAH types. Subjects with clinical manifestations of EDS were also subjected to a validated Sanger-based test of TNX chimeras (Prevention Genetics).12, 13

DNA Sample Preparation

All genomic DNA samples were extracted from frozen peripheral blood by ReproCELL Inc (Beltsville, MD) and stored at −80°C with an estimated concentration of 100 ng/μL. An aliquot of 10 μL of each DNA sample was diluted with 40 μL of water to make 20 ng/μL of working solution and stored at 4°C. Five samples were randomly selected for repeated assay by real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) on a monthly basis, and the consistent results suggested that the DNA samples were stable without detectable degradation during the study period of 3 months.

qPCR

Each test included two separate qPCR reactions testing TNXB exons 35 and 40, respectively, with hemoglobin subunit β (HBB) as a reference gene. The primers and hydrolysis probes were as described in Table 1. Each qPCR reaction was composed of 1 μL of DNA, 1 unit of MyTaq HS DNA Polymerase (Bioline, London, UK), 12.5 μL of TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (2×) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), 400 nmol/L of each primer, and 250 nmol/L of each probe for a TNXB exon (35 or 40) and HBB, and PCR-grade water to make a final volume of 25 μL. An ABI 7300 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) equipped with FAM and VIC channels was used for the assay with ROX as a passive reference. PCR reaction was 50°C for 2 minutes, 95°C for 10 minutes, 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 seconds, 58°C for 20 seconds, and 60°C for 40 seconds (plate read). Samples with an HBB cycle of quantitation (Cq) value within the range of 20 to 30 were subjected to analysis or otherwise repeated by qPCR assay.

Table 1.

Primers and Probes Used for the CAH-X Assay

| Exon/primer | Sequence, dye, and quencher∗ |

|---|---|

| TNXB exon 35 | |

| Forward | 5′-GAGCCTCAGAGTGTGCAGGT-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GTTTTCTTGgCTCCCAcctc-3′ |

| Probe | 5′-FAM-ctgggatcagccCCTGGAGT-MGB-3′ |

| TNXB exon 40 | |

| Forward | 5′-TCCTCAACGGCAACCGc-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GAACACCTGGGAAGCAAGTG-3′ |

| Probe | 5′-FAM-CGTGTTTTGcGACATGGAGAC-MGB-3′ |

| HBB | |

| Forward | 5′-TATCATGCCTCTTTGCACCA-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-AATCCAGCCTTATCCCAACC-3′ |

| Probe3 | 5′-VIC-CAGCTACAATCCAGCTACCATTCTGC-MGB-3′ |

CAH-X, connective tissue dysplasia consistent with hypermobility-type Ehlers-Danlos syndrome due to a contiguous gene deletion involving the adjacent CYP21A2 and TNXB genes.

DNA bases specific to the active gene TNXB are marked in lowercase, and bases shared by both TNXB and pseudogene TNXA are shown in capitals.

ddPCR

The copy numbers of TNXB exons 35 and 40 were also tested separately by droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) using the same primers and probes as used in the qPCR assay. Each 20-μL ddPCR reaction contained 1 μL of DNA, 10 μL of 2× ddPCR Supermix for probes (no deoxyuridine triphosphate; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), 900 nmol/L of each primer, and 250 nmol/L of each probe for a TNXB exon (35 or 40) and HBB. A QX200 AutoDG Droplet Digital PCR System (Bio-Rad Laboratories) was used for the assay by following the manufacturers' instructions, except the PCR reaction was set to be 95°C for 10 minutes; 40 cycles at 94°C for 30 seconds, 58°C for 20 seconds, and 60°C for 40 seconds; a final cycle at 98°C for 10 minutes before cooling to 4°C; with a 2°C/second ramp. Samples with ≥10,000 total accepted droplets and an HBB concentration ranging from 100 to 2000 were subjected to analysis or otherwise repeated by ddPCR assay.

Statistical Analysis

For qPCR, the ΔRn (Rn minus baseline with Rn signifying the reporter signal normalized to ROX signal) thresholds for the Cq values of FAM and VIC channels were set as 0.2 and 0.07, respectively. The ratio of TNXB exons 35 or 40 to HBB was calculated as:

| (1) |

and RX35 <1.2 and RX40 <1 were the cutoff values used for calling the respective exon loss. For ddPCR, standard CNV2 program in QuantaSoft software version 1.7.4.0917 supplied by the manufacturers (Bio-Rad Laboratories) was used to determine the copy numbers of TNXB exons 35 and 40. In both platforms, samples with exons 35 and 40 losses were called as CAH-X CH-1, whereas samples with only exon 40 loss were called as CAH-X CH-2.

Results

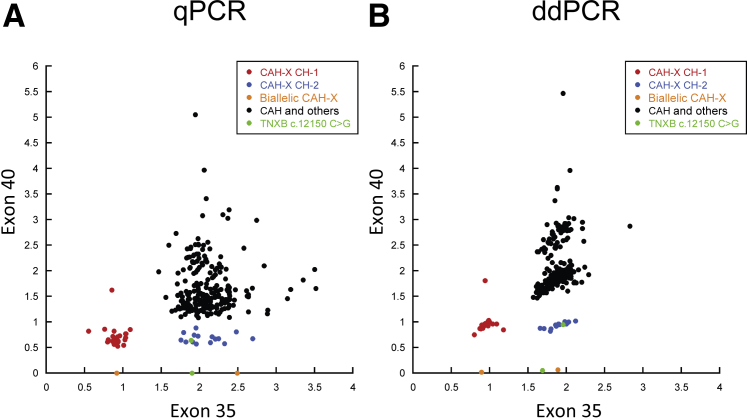

A total of 44 positive calls (26 CAH-X CH-1 and 18 CAH-X CH-2) were made from the cohort of 278 subjects. Heterozygous, homozygous CAH-X chimeras, and the negatives clearly separated into different clusters (Figure 2). All positive calls were confirmed by Sanger sequencing. Two false-positives of CAH-X CH-2 (one hetero- and one homozygous) were observed, due to a rare TNXB exon 40 haplotype having a c.12150C>G (synonymous) variant without the pathogenic c.12174C>G (p.C4058W). No false-negatives were observed. The copy number assay had a sensitivity of 100% (42 positives/42 true-positives), a specificity of 99.2% (234 negatives/236 true negatives) and an overall accuracy rate of 99.3% (276/278) in determining a CAH-X genotype, and results were consistent between the qPCR and ddPCR systems (Figure 2). Six samples had one-time borderline results by qPCR but were negative in the follow-up repeats (data not shown). There were no borderline results by ddPCR. Notably, one subject (CAH carrier with one CAH-X CH-1 allele) had an unusual two copies of TNXB exon 40 measured. Further analysis revealed that the other allele (non-CAH) had contiguous single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of rs77471377 (C>G) and rs4959086 (C>G) to cause a TNXA locus identical to TNXB exon 40 that masked the latter's loss in the CAH-X CH-1 allele. These TNXA SNPs might be common because a total of 46 subjects had ≥2.5 copy numbers measured in TNXB exon 40 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Identification of CYP21A1P-TNXA/TNXB chimeric type by real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) and droplet digital PCR (ddPCR). A: The ratio of TNXB exons 35 and 40 to HBB determined by qPCR. B: The copy numbers of TNXB exons 35 and 40 determined by ddPCR. CAH-X, connective tissue dysplasia consistent with hypermobility-type Ehlers-Danlos syndrome due to a contiguous gene deletion involving the adjacent CYP21A2 and TNXB genes; CAH-X CH-1, CYP21A1P-TNXA/TNXB chimera with TNXB exons 35-44 replaced by TNXA; CAH-X CH-2, CYP21A1P-TNXA/TNXB chimera with TNXB exons 40-44 replaced by TNXA.

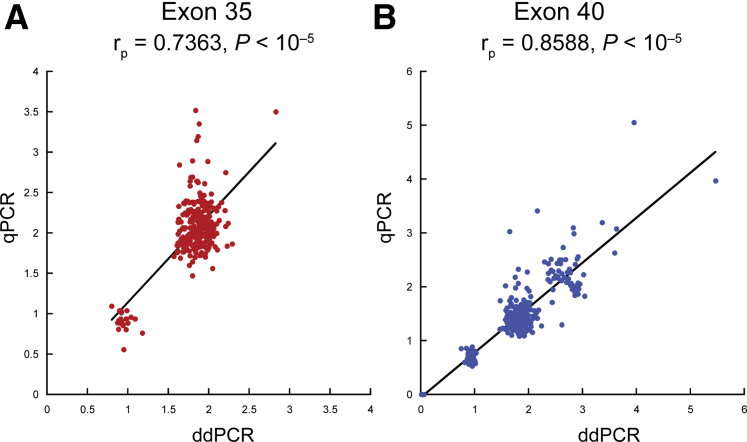

The ratio of TNXB to HBB determined by qPCR and the copy numbers determined by ddPCR provided similar results (Figure 3). However, given that most copy number results fell close to an integer range from 0 to 3, the ddPCR system was considerably more convenient in terms of data interpretation and making the calls.

Figure 3.

Correlation between real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) and droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) results in TNXB exons 35 and 40. A and B: Results by qPCR and ddPCR were comparable for both exon 35 (A) and exon 40 (B). The rp and P values were determined by Pearson correlation. Black lines indicate linear fit.

The CAH cohort of this study had a 15.6% (21/135 21-hydroxylase deficiency CAH probands) prevalence of CAH-X that was higher than the previously estimated 8.5%.13 The prevalence was especially high (29.2% or 21/72) in the subjects with a 30-Kb deletion genotype. As expected due to autosomal dominant inheritance, the prevalence of CAH-X was found to be similar among the affected patients, carriers, and families of CAH (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence of the CAH-X Chimeras in a Cohort of Subjects with Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia due to 21-Hydroxylase Deficiency

| Genotype | Probands |

Patients |

Carriers |

Cohort |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 30-Kb deletion∗ | Total | 30-Kb deletion∗ | Total | 30-Kb deletion∗ | Total | 30-Kb deletion∗ | |

| CAH-X CH-1† | 9.6% (13/135) | 18.1% (13/72) | 10.3% (15/145) | 19.7% (15/76) | 9.3% (11/118) | 21.6% (11/51) | 9.9% (26/263) | 20.5% (26/127) |

| CAH-X CH-2‡ | 5.9% (8/135) | 11.1% (8/72) | 6.9% (10/145) | 13.2% (10/76) | 5.1% (6/118) | 11.8% (6/51) | 6.1% (16/263) | 12.6% (16/127) |

| CAH-X | 15.6% (21/135) | 29.2% (21/72) | 17.2% (25/145) | 32.9% (25/76) | 14.4% (17/118) | 33.3% (17/51) | 16.0% (42/263) | 33.1% (42/127) |

Two subjects had biallelic CAH-X chimeras. One subject with a CH-2/CH-2 genotype was counted once as CH-2 whereas the other subject with a CH-1/CH-2 genotype was counted once as CH-1 in calculating the prevalence in probands, patients, and cohort, respectively.

CAH-X, connective tissue dysplasia consistent with hypermobility-type Ehlers-Danlos syndrome due to a contiguous gene deletion involving the adjacent CYP21A2 and TNXB genes.

Carrier of a 30-Kb deletion.

CAH-X CH-1: CYP21A1P-TNXA/TNXB chimera with TNXB exons 35–44 replaced by TNXA.

CAH-X CH-2: CYP21A1P-TNXA/TNXB chimera with TNXB exons 40–44 replaced by TNXA.

Forty of the 42 CAH-X–positive subjects had a complete or partial clinical evaluation for EDS, and 39 had at least one finding characteristic of EDS. The lone CAH-X–positive subject without EDS findings was an 11-year–old male with CAH carrying a CAH-X CH-1 chimera; and the 2 subjects not evaluated were CAH carriers carrying a CAH-X CH-1 chimera.

In general, patients with monoallelic CAH-X CH-1 had fewer EDS characteristics than did patients with monoallelic CAH-X CH-2, and patients with biallelic CAH-X had the most severe EDS phenotype (Table 3). In addition, carriers of CAH who were heterozygous for a CAH-X mutation tended to have less of an EDS phenotype than did their relatives with CAH who carried the same CAH-X mutation.

Table 3.

Clinical Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome Characteristics of Subjects with CAH-X

| Parameter | CAH patients |

CAH carriers |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAH-X CH-1 | CAH-X CH-2 | Biallelic | CAH-X CH-1 | CAH-X CH-2 | |

| n | 14 | 10 | 2 | 9 | 5 |

| Age, years | 17.2 ± 10.7 (4–39) | 13.1 ± 12.0 (2–44) | 16.0 ± 14.1 (6–26) | 46.9 ± 11.1 (30–63) | 40.8 ± 11.3 (21–49) |

| Females/males | 6/8 | 4/6 | 0/2 | 5/4 | 4/1 |

| Musculoskeletal | |||||

| Generalized hypermobility∗ | 7/13 | 5/10 | 2/2 | 4/9 | 2/5 |

| Small joint hypermobility | 5/14 | 5/10 | 1/2 | 4/9 | 1/5 |

| Large joint hypermobility | 3/14 | 4/10 | 1/2 | 1/9 | 1/5 |

| Subluxations | 4/14 | 3/10 | 1/2 | 3/9 | 0/5 |

| Chronic arthralgia | 4/14 | 2/10 | 2/2 | 4/9 | 1/5 |

| Chronic tendonitis, bursitis or fasciitis | 2/14 | 2/10 | 1/2 | 3/9 | 0/5 |

| Pes planus | 3/14 | 2/10 | 1/2 | 2/9 | 0/5 |

| Dermatologic | |||||

| Skin laxity | 1/14 | 2/10 | 2/2 | 0/9 | 0/5 |

| Wide scars | 0/14 | 2/10 | 1/2 | 0/9 | 0/5 |

| Piezogenic papules | 3/14 | 1/10 | 2/2 | 0/9 | 0/5 |

| Cardiac | |||||

| Congenital defect† | 3/13 | 3/7 | 0/2 | 3/8 | 0/5 |

| Chamber enlargement | 4/13 | 3/7 | 1/2 | 1/8 | 2/5 |

| Enlarged aortic root | 0/13 | 2/7 | 0/2 | 3/8 | 0/5 |

| Gastrointestinal disorder‡ | 1/14 | 1/10 | 1/2 | 1/9 | 1/5 |

| Hernia or prolapse | 0/14 | 4/10 | 1/2 | 3/9 | 1/5 |

Ages are shown as means ± SD (range), and rates of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome findings are shown as number of positives/number evaluated.

CAH-X, connective tissue dysplasia consistent with hypermobility-type Ehlers-Danlos syndrome due to a contiguous gene deletion involving the adjacent CYP21A2 and TNXB genes; CAH-X CH-1, CYP21A1P-TNXA/TNXB chimera with TNXB exons 35-44 replaced by TNXA; CAH-X CH-2, CYP21A1P-TNXA/TNXB chimera with TNXB exons 40-44 replaced by TNXA.

Generalized hypermobility defined as a Beighton score of 5 of 9 or greater in children and of 4 of 9 or greater in postpubertal adolescents and adults.

Congenital heart defect includes mitral leaflet thickening, structural valve abnormality, left ventricular diverticulum, and patent foramen ovale.

Includes gastroesophageal reflux, irritable bowel syndrome, chronic constipation, and diverticulitis.

Discussion

Patients with CAH due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency commonly have a connective tissue dysplasia, CAH-X, due to tenascin-X defects caused by CYP21A1P-TNXA/TNXB chimeric genes.8, 10, 12, 13 In this study, a high-throughput and cost-effective assay that accurately identifies CAH-X in a large cohort of patients with CAH was reported. This assay is based on allele-specific PCR and screens for the two most common CYP21A1P-TNXA/TNXB chimeras causing CAH-X. Cardiovascular abnormalities have been identified in some patients with CAH-X, and clinical management aimed at preventing musculoskeletal manifestations is warranted.12, 13 Thus, early detection of CAH-X is beneficial.

TNXB encodes tenascin-X, which is highly expressed in connective tissues. It is essential in the maintenance of the integrity of the extracellular matrix by regulating the collagen fibril deposition, in which defects lead to EDS, a hereditary connective tissue disorder.21 Complete tenascin-X deficiency has been reported to cause classic EDS (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man number 130000) in an autosomal recessive manner,9 whereas the most prevalent type of hypermobile EDS is associated with defects in tenascin-X in an autosomal dominant manner.10, 12, 13 Although mutations in other parts of TNXB have also been reported in cases of hypermobile EDS, the most prevalent and well-studied type of mutation is the CYP21A1P-TNXA/TNXB chimera, termed CAH-X.16, 17, 18 CAH-X CH-1 causes haploinsufficiency, whereas CAH-X CH-2 causes a dominant negative p.C4058W mutation in tenascin-X, both leading to phenotypic EDS. The assay presented here could also be used to screen patients with hypermobile EDS of unknown etiology.

The diagnosis of EDS due to CAH-X relies mainly on clinical evaluations, such as physical examination for joint hypermobility, skin characteristics, and imaging.14 Options of molecular diagnostic support are mostly unavailable in general clinics or are very limited in research institutes. The serum tenascin-X test based on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay has been used to identify complete deficiency, but it is not accurate in identifying heterozygous forms and is not commercially available for general practice.9, 10 Next-generation sequencing often presents difficulties in mapping the RCCX module genes due to interference by highly homologous pseudogenes and commonly existing copy number variations.22, 23, 24 A multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification–based hypermobility type EDS panel containing COL3A1 and TNXB (MRC-Holland, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) is commercially available for research purposes; however, it detects only CAH-X CH-1 and misses CAH-X CH-2. To date, Sanger sequencing is the most reliable and informative molecular diagnostic method for TNXB variations, but it is laborious and expensive. We therefore developed an assay based on allele-specific PCR for the CAH-X chimera screening. The assay was designed to determine the copy numbers of TNXB exons 35 and 40, then to call and specify the CAH-X chimeras based on the nature of their copy number losses.

The application utilizing data from our cohort indicated that the assay was accurate, high throughput, convenient, and cost-effective. The assay presented here confirmed all 42 previously known CAH-X cases with an overall accuracy rate of 99.28% (276/278) in our CAH cohort. It was compatible with the hydrolysis probe type of digital PCR and real-time PCR systems, and had a typical capacity of 48 samples (96-well plate format) within a few hours. The results were reliable and highly reproducible, as revealed by technical repeats on 84 randomly selected samples by qPCR and 24 by ddPCR. Moreover, only 6 samples had one-time borderline results by qPCR, likely due to heterogeneity of the genomic DNA solution in concentration, quality, or purity; therefore a technical repeat is generally unnecessary. The calls made by the qPCR and ddPCR systems were consistent, but ddPCR offered more convenient data interpretation with a clear positive–negative separation.

The assay was optimized by testing different combinations of primers and probes since the TNXB locus of interest is abundant in SNPs. However, two false-positive calls were made due to rare SNP types; therefore, confirmation by Sanger sequencing should be considered before making a final diagnosis. There was a unique case of a subject with heterozygous CAH-X CH-1 having two copies of TNXB exon 40 measured due to a TNXB-like haplotype [rs77471377 (C>G) and rs4959086 (C>G)] in TNXA that masks the real exon 40 loss in TNXB. This finding raised a concern of the possibility of false-negative results, should a subject with CAH-X CH-2 have the same TNXA haplotype. Forty-six samples with a TNXB exon 40 copy number of ≥2.5, as determined by ddPCR, were observed, suggesting that those SNPs might be common in TNXA. In fact, SNPs rs77471377 (C>G) and rs4959086 (C>G) have allele frequencies of 0.02 (469/22,344) and 0.18 (4060/22,624), respectively, in the general population, according to the gnomAD browser (https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org, last accessed March 1, 2019).25 However, the allele frequency of the TNXA haplotype containing both variants remains unknown, and both SNPs are listed as “failed random forest filters,” suggesting that they were variants of low quality likely due to the mutual interference between TNXA and TNXB. Although no false-negative calls were observed in our cohort, an expanded study should be conducted to evaluate the prevalence of this TNXA haplotype and hence the risk for false-negatives.

As shown in this study, the EDS caused by the CAH-X chimeras is prevalent in patients and carriers of CAH, especially in those with a 30-Kb deletion genotype. CAH is a rare autosomal recessive genetic disease, and the carrier rate for classic CAH in the general population is 1 in 60.1, 26 Given that approximately 30% of classic CAH mutations are 30-Kb deletions7 and that 30% of deletions are CAH-X chimeras, hypermobile EDS due to CAH-X alone is estimated to affect 1 in 667 individuals in the general population, which is much higher than the previously estimated 1 in 5000 rate of all hypermobile EDS types combined.14 Thus, it appears that CAH-X–causing variants are presently underdetected. Moreover, the CAH-X CH-1 and CH-2 are unlikely to be detected by the commonly used whole-exome sequencing, leaving individuals carrying these variants undiagnosed. It is important to develop an easy means of detecting these variants, making our assay of interest to both clinicians and molecular genetics laboratories.

To date, CAH screening by a hormonal test is part of the mandatory neonatal screenings in the United States and more than 40 other countries. Although often plagued by ambiguous results and false calls, the CAH screening is generally successful in identifying affected patients with classic CAH, especially if combined with a second-tier follow-up.3, 27 Second-tier genetic screening has been proposed as an adjunct to hormonal measurements, but genotyping remains costly and time-consuming and thus has not been widely used. The high-throughput screening assay presented here is cost-effective and may be combined with other genotyping to create a more cost-effective and efficient second-tier screening test. Alternatively, this assay is suitable for a high-throughput CAH-X screening applicable to all CAH patients, carriers, and patients with EDS of unknown etiology, and it would be cost-effective and beneficial by offering early awareness needed for clinical management and the development of long-term preventive strategies in minimizing EDS symptomatology.

Footnotes

Supported by the NIH Intramural Research Program.

Disclosures: D.P.M. received unrelated research funds from Diurnal Limited and Spruce Biosciences through the NIH Cooperative Research and Development Agreement and is a commissioned officer in the US Public Health Service.

References

- 1.Speiser P.W., Arlt W., Auchus R.J., Baskin L.S., Conway G.S., Merke D.P., Meyer-Bahlburg H.F., Miller W.L., Murad M.H., Oberfield S.E., White P.C. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to steroid 21-hydroxylase deficiency: an Endocrine Society Clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103:4043–4088. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-01865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hannah-Shmouni F., Morissette R., Sinaii N., Elman M., Prezant T.R., Chen W., Pulver A., Merke D.P. Revisiting the prevalence of nonclassic congenital adrenal hyperplasia in US Ashkenazi Jews and Caucasians. Genet Med. 2017;19:1276–1279. doi: 10.1038/gim.2017.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.White P.C. Neonatal screening for congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2009;5:490–498. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2009.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blanchong C.A., Zhou B., Rupert K.L., Chung E.K., Jones K.N., Sotos J.F., Zipf W.B., Rennebohm R.M., Yung Yu C. Deficiencies of human complement component C4A and C4B and heterozygosity in length variants of RP-C4-CYP21-TNX (RCCX) modules in Caucasians. The load of RCCX genetic diversity on major histocompatibility complex-associated disease. J Exp Med. 2000;191:2183–2196. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.12.2183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang Y., Chung E.K., Wu Y.L., Savelli S.L., Nagaraja H.N., Zhou B., Hebert M., Jones K.N., Shu Y., Kitzmiller K., Blanchong C.A., McBride K.L., Higgins G.C., Rennebohm R.M., Rice R.R., Hackshaw K.V., Roubey R.A., Grossman J.M., Tsao B.P., Birmingham D.J., Rovin B.H., Hebert L.A., Yu C.Y. Gene copy-number variation and associated polymorphisms of complement component C4 in human systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE): low copy number is a risk factor for and high copy number is a protective factor against SLE susceptibility in European Americans. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:1037–1054. doi: 10.1086/518257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banlaki Z., Doleschall M., Rajczy K., Fust G., Szilagyi A. Fine-tuned characterization of RCCX copy number variants and their relationship with extended MHC haplotypes. Genes Immun. 2012;13:530–535. doi: 10.1038/gene.2012.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finkielstain G.P., Chen W., Mehta S.P., Fujimura F.K., Hanna R.M., Van Ryzin C., McDonnell N.B., Merke D.P. Comprehensive genetic analysis of 182 unrelated families with congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:E161–E172. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burch G.H., Gong Y., Liu W., Dettman R.W., Curry C.J., Smith L., Miller W.L., Bristow J. Tenascin-X deficiency is associated with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Nat Genet. 1997;17:104–108. doi: 10.1038/ng0997-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schalkwijk J., Zweers M.C., Steijlen P.M., Dean W.B., Taylor G., van Vlijmen I.M., van Haren B., Miller W.L., Bristow J. A recessive form of the Ehlers-Danlos syndrome caused by tenascin-X deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1167–1175. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa002939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zweers M.C., Bristow J., Steijlen P.M., Dean W.B., Hamel B.C., Otero M., Kucharekova M., Boezeman J.B., Schalkwijk J. Haploinsufficiency of TNXB is associated with hypermobility type of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:214–217. doi: 10.1086/376564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen W., Kim M.S., Shanbhag S., Arai A., VanRyzin C., McDonnell N.B., Merke D.P. The phenotypic spectrum of contiguous deletion of CYP21A2 and tenascin XB: quadricuspid aortic valve and other midline defects. Am J Med Genet A. 2009;149a:2803–2808. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merke D.P., Chen W., Morissette R., Xu Z., Van Ryzin C., Sachdev V., Hannoush H., Shanbhag S.M., Acevedo A.T., Nishitani M., Arai A.E., McDonnell N.B. Tenascin-X haploinsufficiency associated with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome in patients with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:E379–E387. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-3148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morissette R., Chen W., Perritt A.F., Dreiling J.L., Arai A.E., Sachdev V., Hannoush H., Mallappa A., Xu Z., McDonnell N.B., Quezado M., Merke D.P. Broadening the spectrum of Ehlers Danlos syndrome in patients with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:E1143–E1152. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beighton P., De Paepe A., Steinmann B., Tsipouras P., Wenstrup R.J. Ehlers-Danlos syndromes: revised nosology, Villefranche, 1997. Ehlers-Danlos National Foundation (USA) and Ehlers-Danlos Support Group (UK) Am J Med Genet. 1998;77:31–37. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19980428)77:1<31::aid-ajmg8>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bristow J., Tee M.K., Gitelman S.E., Mellon S.H., Miller W.L. Tenascin-X: a novel extracellular matrix protein encoded by the human XB gene overlapping P450c21B. J Cell Biol. 1993;122:265–278. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.1.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zweers M.C., Dean W.B., van Kuppevelt T.H., Bristow J., Schalkwijk J. Elastic fiber abnormalities in hypermobility type Ehlers-Danlos syndrome patients with tenascin-X mutations. Clin Genet. 2005;67:330–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2005.00401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Demirdas S., Dulfer E., Robert L., Kempers M., van Beek D., Micha D., van Engelen B.G., Hamel B., Schalkwijk J., Loeys B., Maugeri A., Voermans N.C. Recognizing the tenascin-X deficient type of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: a cross-sectional study in 17 patients. Clin Genet. 2017;91:411–425. doi: 10.1111/cge.12853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Penisson-Besnier I., Allamand V., Beurrier P., Martin L., Schalkwijk J., van Vlijmen-Willems I., Gartioux C., Malfait F., Syx D., Macchi L., Marcorelles P., Arbeille B., Croue A., De Paepe A., Dubas F. Compound heterozygous mutations of the TNXB gene cause primary myopathy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2013;23:664–669. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen W., Perritt A.F., Morissette R., Dreiling J.L., Bohn M.F., Mallappa A., Xu Z., Quezado M., Merke D.P. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome caused by Biallelic TNXB variants in patients with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Hum Mutat. 2016;37:893–897. doi: 10.1002/humu.23028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen W., Xu Z., Sullivan A., Finkielstain G.P., Van Ryzin C., Merke D.P., McDonnell N.B. Junction site analysis of chimeric CYP21A1P/CYP21A2 genes in 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Clin Chem. 2012;58:421–430. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2011.174037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mao J.R., Taylor G., Dean W.B., Wagner D.R., Afzal V., Lotz J.C., Rubin E.M., Bristow J. Tenascin-X deficiency mimics Ehlers-Danlos syndrome in mice through alteration of collagen deposition. Nat Genet. 2002;30:421–425. doi: 10.1038/ng850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mueller P.W., Lyons J., Kerr G., Haase C.P., Isett R.B. Standard enrichment methods for targeted next-generation sequencing in high-repeat genomic regions. Genet Med. 2013;15:910–911. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lao Q., Jardin M.D., Jayakrishnan R., Ernst M., Merke D.P. Complement component 4 variations may influence psychopathology risk in patients with congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Hum Genet. 2018;137:955–960. doi: 10.1007/s00439-018-1959-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hogan G.J., Vysotskaia V.S., Beauchamp K.A., Seisenberger S., Grauman P.V., Haas K.R., Hong S.H., Jeon D., Kash S., Lai H.H., Melroy L.M., Theilmann M.R., Chu C.S., Iori K., Maguire J.R., Evans E.A., Haque I.S., Mar-Heyming R., Kang H.P., Muzzey D. Validation of an expanded carrier screen that optimizes sensitivity via full-exon sequencing and panel-wide copy number variant identification. Clin Chem. 2018;64:1063–1073. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2018.286823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lek M., Karczewski K.J., Minikel E.V., Samocha K.E., Banks E., Fennell T. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature. 2016;536:285–291. doi: 10.1038/nature19057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pang S.Y., Wallace M.A., Hofman L., Thuline H.C., Dorche C., Lyon I.C., Dobbins R.H., Kling S., Fujieda K., Suwa S. Worldwide experience in newborn screening for classical congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Pediatrics. 1988;81:866–874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kopacek C., Prado M.J., da Silva C.M.D., de Castro S.M., Beltrao L.A., Vargas P.R., Grandi T., Rossetti M.L.R., Spritzer P.M. Clinical and molecular profile of newborns with confirmed or suspicious congenital adrenal hyperplasia detected after a public screening program implementation. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2019;95:282–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2018.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]