Abstract

Mexico is a culturally, socially and economically heterogeneous country, with a population of over 100 million. Although it is regarded as a country with a medium– high income according to World Bank criteria, inequality continues to be one of its main problems. In addition to this, the country is going through a difficult period. Large parts of the population face economic insecurity, as a result of which feelings of despair, fear and impotence are common. It is hardly surprising, then, that mental disorders should constitute a major public health problem: depression is the main cause of loss of healthy years of life (6.4% of the population suffer from it), while alcohol misuse is the 9th (2.5%) and schizophrenia the 10th (2.1%) most common health problem (González-Pier et al, 2006).

The Mexican health system

The Mexican health system is divided into three types of service provision.

First, social security provides services for the formal, salaried sector of the economy and covers 47% of the population. This type of security guarantees free access to healthcare and is financed through contributions from both employers and employees.

Second, those not covered by social security (45% of the total Mexican population), who are also the poorest, were long regarded as a residual group, for whom the Health Secretariat provided a poorly defined benefits package. In 2000, the Popular Insurance Scheme was created to provide protection for this vulnerable population. The intention was to expand the coverage of this insurance only gradually. Two kinds of mental health service are included under this scheme: preventive medicine and external consultation services. Beneficiaries of the Popular Insurance Scheme are entitled to receive treatment for the diseases included in the Universal Catalogue of Essential Health Services (CAUSES), which covers all the medical services provided at primary health centres and associated medication. In relation to mental health, CAUSES include: attention deficit disorder, eating disorders, alcohol misuse, depression, psychosis, epilepsy, Parkinson’s disease and convulsive crises.

Third, there is a heterogeneous group of private service providers who attend non-insured families who are able to afford them and the population which, despite having some form of social security, is dissatisfied with the quality of services; this group accounts for just 4% of the population (Frenk, 2007).

Mental health services

Mental health policy and legislation

The main axes of the legislative and political actions related to mental health, formulated in 1983, were promotion, prevention, treatment and rehabilitation. In order to restructure these policies, consultations were carried out in 2001 with the participation of politicians, government officials, professionals, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and patients. On the basis of these consultations, the 2001–06 Mental Health Programme of Action proposed an integrated care model. That programme, in addition to psychiatric hospitals, community health centres, day hospitals and intermediate residences, emphasises patients’ rights and their social inclusion. Its main components are: strategies to reform existing services, mental health promotion and prevention, improving mental health training programmes for staff, and the encouragement of research work in this field.

The most recent National Health Programme (2007–12) proposes five social policy objectives:

improve the population’s health conditions

provide efficient health services, guaranteeing quality, warmth and safety for the patient

reduce health inequalities

prevent the impoverishment of the population for health reasons

guarantee that health will contribute to overcoming poverty.

On the basis of these objectives and in order to reinforce and lend continuity to the care model formulated in 2001, a proposal was made to create a national mental health network, comprising specialist units within primary care (UNEMES), organised on the basis of a community model. The aim is for these specialist units to offer out-patient services for timely detection, care and rehabilitation, while offering the necessary services for effective treatment. The aim is for UNEMES to function as the axis around which out-patient and community mental healthcare will function. They must therefore consist of multidisciplinary teams offering integrated care. In addition to their welfare functions, they will be an important space for health prevention and promotion, as well as offering training opportunities for other levels of care.

Although major efforts have been made in Mexico to advance the care of patients with mental disorders, the main challenge at present is to achieve the integration of mental healthcare into general healthcare programmes. This is the only way the gap between care and treatment needs will be bridged.

Mental health service resources

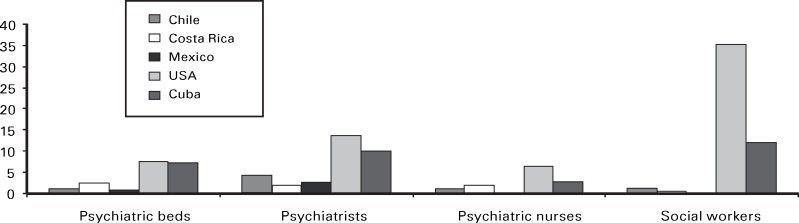

The Mexican mental health system has 0.667 psychiatric beds for every 10 000 inhabitants. There are 0.51 beds in psychiatric hospitals plus 0.051 beds available at general hospitals for this same population rate. As for human resources, it is estimated that for every 100 000 inhabitants there are 2.8 psychiatrists, 44 psychologists, 0.12 psychiatric nurses, 1.5 neurosurgeons, 1.2 neurologists and 0.20 social workers specialising in psychiatry (World Health Organization, 2005). As Fig. 1 illustrates, Mexico has a significant shortfall in resources compared with other countries on the American continent.

Fig. 1. Mental healthcare human resources per 100 000 inhabitants (does not include psychologists because the data are not available in Mexico) (World Health Organization, 2005).

Organisation of services

There are three types of service at the primary healthcare level: mental healthcare modules integrated into general hospitals; health modules integrated into health centres; and psychiatric units integrated into general hospitals. However, many of these units or modules lack sufficient minimum personnel to be able to cover the demand for treatment; also, they are not uniformly distributed geographically.

At the secondary healthcare level, the Health Secretariat only has eight specialised mental healthcare units designed for out-patients and the provision of specialised psychological medical care. At this level of care, 41% of all institutional psychiatrists and psychologists are concentrated in Mexico City.

Lastly, there are the psychiatric hospitals. Mexico has 31 public institutions, distributed unevenly throughout 23 of the country’s 31 states. The units operate on the basis of two main schemes: short and long hospital stays. Although these are their main activities, in recent years they have largely been devoted to specialist out-patient care, because of the high demand for and the limited supply of services of this nature. ‘Day hospital management’ is a concept that is currently being implemented at certain institutions. The experience has been satisfactory, since this form of management reduces the number of relapses and increases patients’ social inclusion (Secretaria de Salud, 2004).

In rural areas there are no local specialist mental healthcare institutions. A visit to the psychiatrist or psychologist may involve a day’s travelling as well as considerable expense. Consequently, the rural population often consults traditional doctors and other informal agents.

Psychiatric training

The teaching of psychiatry in Mexico is relatively recent. The earliest psychiatry hospital residences began in 1948. In 1951 a clinical course was established at the National Autonomous University (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, UNAM); it is now a 3-year programme. Since 1971, the UNAM has offered specialist courses in the different areas of psychiatry and provides master’s degree and PhD programmes.

In 1994, the UNAM with the National Academy of Medicine and other institutions created the Single Medical Specialisation Programme. This has been taught at all schools of medicine and medical faculties, which ensures that the academic course is standardised.

There is only one specialisation in psychiatric social work, taught at the National Institute of Psychiatry and coordinated by the UNAM. There are two formal courses for psychiatric nursing, one taught at the UNAM National School of Nursing and another at the Instituto Politecnico Nacional (IPN) School of Nursing. Courses are also taught after the basic nursing degree at Mexico’s largest psychiatric hospitals and at the National Institutes of Neurology and Psychiatry.

Mental health research

Mental health research in Mexico faces difficulties due to the shortage of trained professionals and a lack of high-technology equipment. Despite this, various Mexican institutions undertake research in the clinical, neuroscience, epidemiological and social spheres of mental health.

The main clinical areas researched are genetics, clinimetry, neurochemistry, psychopharmacology, immunology, phytopharmacology, brain cartography and imaging. The most important fields of research in the field of neuroscience are: neurophysiology, chronobiology, neurobiology, bioelectronics, ethology and comparative psychology. The main lines of research related to the epidemiological and social areas are: psychiatric epidemiology, health systems, drug dependence, suicide, violence, mental health in vulnerable groups and evaluation of intervention models.

Human rights and future challenges

In 1995, an official Mexican regulation for the provision of psychiatric services in medical care hospital units was issued. This regulation focuses on two areas: quality specialised medical care and the preservation of the user’s human rights. This regulation fits in with the United Nations’ Principles for the Protection of Persons Suffering from Mental Illness and for the Improvement of Mental Health Care (1991). One of the shortcomings of the Mexican regulation is that it fails to mention the rights of children and teenagers with mental illness, and it therefore needs revision.

Important advances have included increasing the budget to treat mental illness and the creation of innovative primary mental healthcare approaches. Nevertheless, the proportion of people suffering from mental diseases who receive treatment remains low. The greatest challenge is to expand coverage and achieve universal mental healthcare services, in order to reach the most neglected groups, but also to develop new, improved, culturally sensitive treatments that can meet the population’s needs, fostering help seeking and treatment compliance.

Sources

- Comisión Nacional de Derechos Humanos (1995) Lineamientos para la Preservación de los Derechos Humanos en los Hospitales Psiquiátricos. [Guidelines for the Preservation of Human Rights in Psychiatric Hospitals.] Comisión Nacional de Derechos Humanos. [Google Scholar]

- Frenk, J. (2007) Bridging the divide: global lessons from evidence-based health policy in Mexico. Salud Publica, 49 (suppl. 1), S14–S22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Pier, E., Gutiérrez-Delgado, C., Stevens, G., et al. (2006) Priority setting for health interventions in Mexico´s system of social protection in health. Lancet, 368, 1608–1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secretaría de Salud (2004) Salud México 2004. Información para la rendición de cuentas. [Health Mexico 2004. Accounting Information.] Secretaría de Salud. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2005) Mental Health Atlas: Mexico. Available at http://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/atlas/ (last accessed July 2009).