Abstract

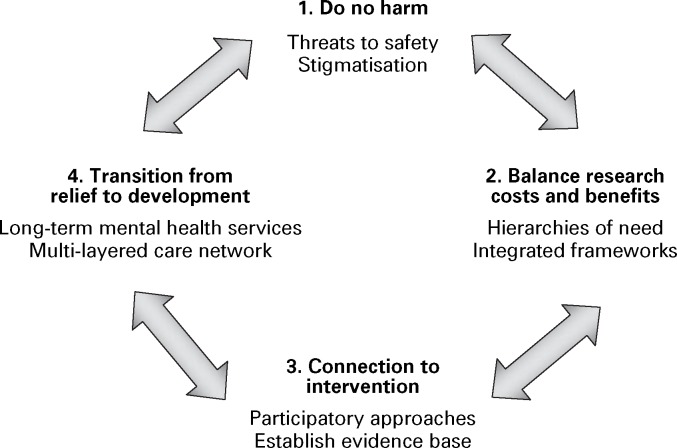

Child soldiers represent a challenging population for mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS), as we have little evidence regarding their needs or the efficacy of interventions. Despite an increasing breadth of MHPSS interventions for children affected by war, very few are supported by evidence (Jordans et al, 2009). In a recent decade-long conflict, Maoists and the government of Nepal conscripted thousands of children to serve as soldiers, sentries, spies, cooks and porters. After the war ended in 2006, we began a project incorporating research into the development of interventions for former child soldiers. Through this work, conducted with Transcultural Psychosocial Organization (TPO) Nepal, we identified four key principles to guide research and intervention with child soldiers (Fig. 1). We present these principles as location-and context-specific examples of the growing effort to develop guidelines and recommendations for research and intervention in acute post-conflict settings (Inter-Agency Standing Committee, 2007; Allden et al, 2009).

Fig. 1. Child Soldier Four-Principle (C4P) approach to mental health research and psychosocial intervention.

Principle 1. Do no harm

While originating in the clinical ethic of non-maleficence, what is meant by ‘do no harm’ when working with child soldiers has not been well defined. In conflict settings, harm can manifest as threats to the safety of former child soldiers, their families and their communities. Research and intervention may expose child soldiers who have tried to hide their association with an armed group, thus placing them and their families in danger of revenge by other soldiers or aggrieved civilians. Many children in Nepal concealed their identity as former combatants. When boy soldiers returned home, they often told family and neighbours they had been working in India rather than disclose they were fighting with an armed group. When girl soldiers returned home, their parents would often send them to live in remote regions with other relatives or they would marry the girls to men in distant villages, where their status as former soldiers would not be known.

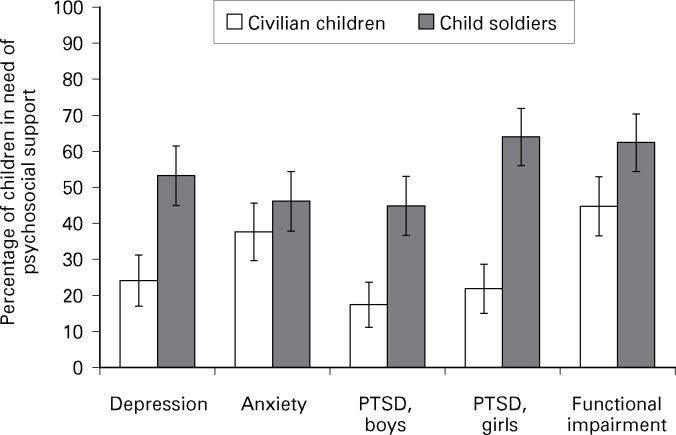

To address this potential harm, we did not limit the research and service provision to child soldiers. Rather, we designed the project to explore the mental health of both child soldiers and civilian children. Participation in the study, therefore, did not automatically identify a child as a former combatant. This was also beneficial from a theoretical and needs assessment perspective. At the time of the study, it was not known empirically whether child soldiers needed more or different interventions than other children, because of the lack of studies comparing child soldiers with never-conscripted children (see Fig. 2) (Kohrt et al, 2008).

Fig. 2. Proportion of child soldiers and civilian children meeting criteria for depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and functional impairment. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Data from Kohrt et al (2008).

Mental health research also risks stigmatisation of former child soldiers. Mental health continues to carry a strong stigma in Nepal, as in most parts of the world (Kohrt & Harper, 2008). Mental health enquiries may appear to be accusations that one is ‘crazy’ or ‘mad’, as was the case with terms used to describe post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) by some clinicians in Nepal. Furthermore, even the experience of traumatic events in itself can be stigmatising, because some interpretations of karma attach blame to individuals for their suffering (Kohrt & Hruschka, 2010). Therefore, we focused on normative language related to Nepali concepts of the heart and mind. This language gave children a therapeutic opportunity to share feelings and emotionally support other children in a non-stigmatising atmosphere (Karki et al, 2009).

Principle 2. Balance research costs and benefits

Overriding concerns in relation to studies in post-conflict settings are necessity, feasibility and who will be the direct and indirect beneficiaries (de Jong, 2002). One must consider hierarchies of need in conflict settings. Is mental health research the most pertinent topic to be investigating? Research on food security, livelihood, safety and security or other medical concerns may be more necessary. For the child participants, is time in a research study as beneficial for long-term mental health as engaging in other activities, such as rebuilding damaged structures, going to school or working? In Nepal, child soldiers said MHPSS was a top priority, alongside education and poverty relief. Having opportunities to express feelings, promote belonging and increase social cohesiveness were considered first steps for the successful reintegration of child soldiers. Child soldiers participating in our research highlighted goals of ‘feelings of belonging’, ‘being respected and listened to’, ‘having opportunities to express feelings’ and ‘dealing with fear, regret, and hopelessness’ (Karki et al, 2009).

The balance of costs and benefits raises the need to consider integrated frameworks. Isolated MHPSS interventions may detract from addressing other basic needs, physical health, education and economics. MHPSS interventions in isolation risk inefficacy. Therefore, we incorporated MHPSS alongside ‘reintegration packages’, comprising formal education, non-formal education, vocational training and income generation. Former child soldiers in receipt of mental healthcare services were able to maximise their educational and occupational opportunities. In addition, we provided MHPSS training to teachers. Teachers discriminated against child soldiers because of fear and insecurity related to a transformed balance of power (Kohrt et al, 2010). During the war, child combatants had threatened, abducted and tortured teachers. Now they and their comrades in the classroom were expected to obey teachers’ edicts. Our intervention helped teachers to disclose their fears and consider ways to promote safe classrooms and non-violent expressions of agency for students.

Principle 3. Connection to intervention

The transformation of research results into intervention is centre stage when working with child soldiers. In post-conflict settings, research that does not contribute to interventions should raise ethical concerns. Participatory research avoids this by providing strong connections between research and intervention salient to the local community. We adopted a participatory method to develop ‘child-led indicators’, in a process conducted over 3 days with groups of eight to ten child soldiers (Karki et al, 2009). Child soldiers identified psychosocial problems affecting them and processes to address these needs. The children developed indicators to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions.

Interventions in the absence of research can be even more problematic. Evidence-based interventions are crucial. While interventions have typically prioritised child soldiers over other children affected by conflict, there is a paucity of data demonstrating their greater need. In addition, war trauma is often presumed to be the predominant cause of mental health problems among child soldiers. We found that for some child soldiers their experiences after war were more damaging to their mental and psychosocial health than were their war-related traumas, as we have depicted in the documentary film Returned: Child Soldiers of Nepal’s Maoist Army (Koenig & Kohrt, 2009). Furthermore, we found that girl soldiers in Hindu communities were more vulnerable to MHPSS problems than those in mixed-religion and Buddhist communities (Kohrt et al, 2011). These findings helped us target the type and location of reintegration interventions and to allocate resources to those most vulnerable.

Principle 4. Transition from relief to development

The fourth principle recognises the need to consider the long-term development of mental health services, rather than solely attending to acute relief efforts. World regions affected by war often lack an effective mental healthcare system, especially for children. There is a need to consider how the energy, workforce and finances invested during the post-conflict period can be extended to services that will last beyond the acute phase of support. Moreover, MHPSS problems after war may be as related to chronic structural violence factors as to war-related exposures. Therefore, interventions should address chronic social problems as well as war trauma.

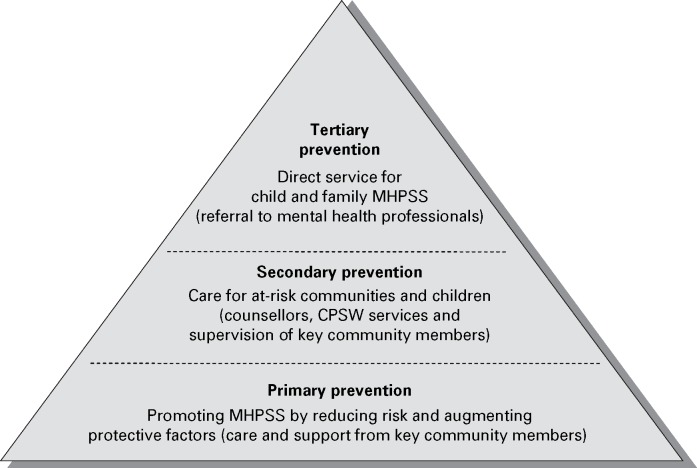

In Nepal, we accounted for these concerns by designing a multi-layered care approach, which aimed to have a multiplicative effect (Jordans et al, 2010) (see Fig. 3). We trained a small group of community psychosocial workers (CPSWs) in a number of districts and these individuals were then able to transmit skills, engage with, support and mobilise community stakeholders. The CPSWs’ training was done alongside the training of psychosocial counsellors, who received 6 months of instruction and provided a second level of care, bridging community-focused and individual-focused care. The training focused on improving the resources within children’s social networks rather than just dispensing individualised care to children. This approach also benefited other child soldiers and civilian children (in that those who did not receive individualised care profited from the augmented community services).

Fig. 3. Mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) intervention pyramid for the child soldier intervention in Nepal. CPSW, community psychosocial worker. Adapted from Inter-Agency Standing Committee (2007) and Jordans et al (2010).

Conclusion

Even in areas with scarce clinical resources, there are opportunities to address the mental health needs of child soldiers. Working in acute post-conflict settings, the Child Soldier Four-Principle (C4P) approach comprises addressing the costs and benefits of research amid limited time and resources, transforming research into intervention to assure that programmes are evidence-based, and designing interventions that can be translated from emergency relief efforts to long-term sustainable development of mental health services. Taken together, these principles represent a do no harm framework that maximises well-being in clinically resource-poor environments.

References

- Allden, K., Jones, L., Weissbecker, I., et al. (2009) Mental health and psychosocial support in crisis and conflict: report of the Mental Health Working Group. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 24 (suppl. 2), s217–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong, J. T. V. M. (2002) Public mental health, traumatic stress, and human rights violations in low-income countries. In Trauma, War, and Violence: Public Mental Health in Socio-cultural Context (ed. de Jong J. T. V. M.), pp. 1–91. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Inter-Agency Standing Committee (2007) IASC Guidelines on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency Settings. IASC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordans, M. J. D., Tol, W. A., Komproe, I. H., et al. (2009) Systematic review of evidence and treatment approaches: psychosocial and mental health care for children in war. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 14, 2–14. [Google Scholar]

- Jordans, M. J. D., Komproe, I. H., Tol, W. A., et al. (2010) Practice-driven evaluation of a multi-layered psychosocial care package for children in areas of armed conflict. Community Mental Health Journal, DOI 10.1007/s10597-10010-19301-10599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karki, R., Kohrt, B. A. & Jordans, M. J. D. (2009) Child led indicators: pilot testing a child participation tool for psychosocial support programmes for former child soldiers in Nepal. Intervention: International Journal of Mental Health, Psychosocial Work and Counselling in Areas of Armed Conflict, 7, 92–109. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig, R. A. & Kohrt, B. A. (2009) Returned: Child Soldiers of Nepal’s Maoist Army. Documentary film (HD DVD-Widescreen, 57 minutes). Adventure Production Pictures/Documentary Educational Resources (DER) See http://www.der.org/films/returned.html. [Google Scholar]

- Kohrt, B. A. & Harper, I. (2008) Navigating diagnoses: understanding mind–body relations, mental health, and stigma in Nepal. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 32, 462–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohrt, B. A. & Hruschka, D. J. (2010) Nepali concepts of psychological trauma: the role of idioms of distress, ethnopsychology, and ethnophysiology in alleviating suffering and preventing stigma. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, DOI 10.1007/s11013-11010-19170-11012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohrt, B. A., Jordans, M. J. D., Tol, W. A., et al. (2008) Comparison of mental health between former child soldiers and children never conscripted by armed groups in Nepal. JAMA, 300, 691–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohrt, B. A., Tol, W. A., Pettigrew, J., et al. (2010) Children and revolution: the mental health and psychosocial wellbeing of child soldiers in Nepal’s Maoist army. In The War Machine and Global Health (eds Singer M. & Hodge G. D.), pp. 89–116. Altamira Press/Rowan & Littlefield Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Kohrt, B. A., Jordans, M. J. D., Tol, W. A., et al. (2011) Social ecology of child soldiers: child, family, and community determinants of mental health, psychosocial wellbeing, and reintegration in Nepal. Transcultural Psychiatry, 47, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]