Abstract

A tradition of Romano-Germanic or civil law defines the legal system in Finland. Laws of relevance to psychiatry are the 1990 Mental Health Act and, insofar as it pertains to forensic psychiatry, the Criminal Law (1889) and the Law on State Mental Hospitals (1987, revised 1997). These are outlined in the present paper.

All medical practice is, to a significant degree, controlled by law. Thus, although clinical goals are shared by most doctors around the globe, the practice of psychiatry is profoundly affected by the varying legal frameworks and other preconditions in different countries, ranging from the maximum-security units of some psychiatric hospitals in low- and middle-income countries, sometimes described as ‘ghettos within ghettos’ (Njenga, 2006), to the status of psychiatry and its various subspecialties as scientifically active independent disciplines in most higher-income countries.

Just as the legal tradition of common law defines the judicial system in the UK and Islamic law in the Middle East, it is the tradition of Romano-Germanic law (‘civil law’) that defines the legal system in most of continental Europe (Abdalla-Filho & Bertolote, 2006) and, indeed, in Finland. Finland is a northern European urbanised parliamentary democracy and a member of both the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the European Union (EU), with a total population of approximately 5.4 million. Laws of particular relevance for psychiatry in Finland are the Mental Health Act 1990 and, insofar as it pertains to forensic psychiatry, the Criminal Law (1889) and the Law on State Mental Hospitals (1987, revised 1997) (Eronen et al, 2000).

The Mental Health Act

The Mental Health Act 1990/1116 stipulates that it is the responsibility of the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, and the provincial and municipal administrators acting under it, to organise mental health services. The Act expressly stipulates that these services must be primarily arranged on an out-patient basis, so as to support the independence of psychiatric patients. Indeed, there has been a gradual process of deinstitutionalisation in Finland since the 1990s, although, if the condition of the patient warrants it, involuntary hospital detention can be mandated if certain preconditions are fulfilled (Box 1).

Box 1. The three preconditions for compulsory psychiatric hospital admission

The individual suffers from a mental illness, or, if under 18, a serious mental disorder, which necessitates treatment because leaving the condition untreated would result in:

-

worsening of the psychiatric condition

and/or

a threat to the health or safety of the individual him-

or herself

and/or

a threat to the health or safety of others.

All other mental health services are inapplicable or inadequate

The actual diagnostic term used in the Act as a precondition for involuntary treatment translates as ‘mental illness’ and is understood as a psychotic state, namely delirium, severe dementia and other so-called organic psychoses, schizophrenia and other schizophreniform psychoses, psychotic depression and mania (Putkonen & Völlm, 2007). For people under 18, the diagnostic criteria are more inclusive and ‘serious mental disorder’ (Box 1) is understood as including serious self-harm, serious substance use disorders and anorexia, in addition to the psychoses. It is noteworthy that the acceptance of these illnesses as preconditions for involuntary treatment arises from a non-formal understanding of the terms ‘mental illness’ and ‘serious mental disorder’ by both doctors and administrative bodies, rather than from unambiguous written guidelines or legal statutes. Nevertheless, it is generally accepted that these preconditions are adhered to.

Committal to a hospital based on these diagnoses does not in itself affect patients’ rights in terms of mental capacity. That is to say, detained persons retain their basic right to judge their own best interests in areas other than the involuntary treatment of the mental illness. The process of restricting a person’s right to make autonomous, legally binding decisions and the appointment of a substitute decision-maker for a person with reduced mental capacity do not fall within the remit of the Mental Health Act; they are legal decisions, although a medical statement may be requested.

Compulsory out-patient treatment is not currently permitted, although there have been attempts to instigate a change in the law to this effect in the case of forensic patients.

Decision-making responsibilities

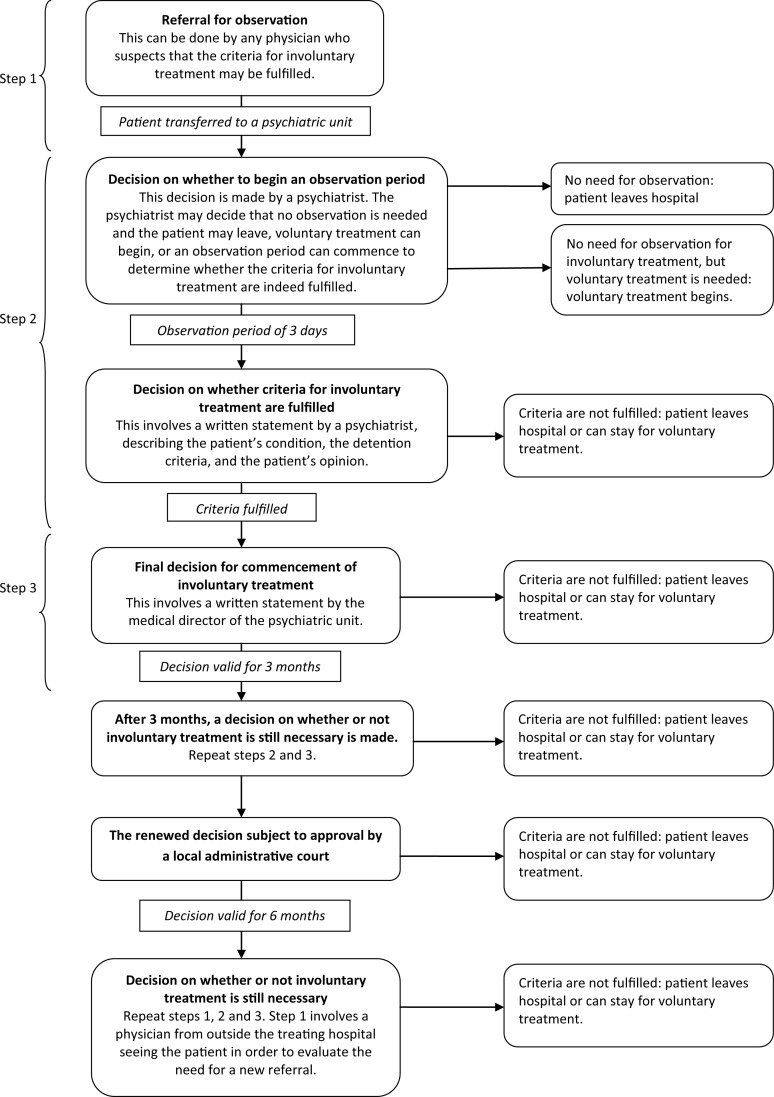

In Finland, the decision-making process for involuntary treatment, including discharge, involves only medical doctors, although the local administrative courts oversee certain decisions (Fig. 1). No other legal authorities are regularly employed as safeguards during the decision-making process for involuntary treatment. Neither does the law require the treating doctors to subject any other treatment decisions, such as those involving involuntary medication or electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), to a second opinion – unlike the situation in the UK, with the SOAD (second-opinion appointed doctor) service – although where involuntary treatment is prolonged, a physician, usually a general practitioner (GP), from outside the treating hospital must evaluate the patient at regular intervals (Fig. 1). In effect, the Mental Health Act places the final responsibility for treatment decisions on the treating doctor, and it is notable that any generally recognised form of treatment can be administered even against the will of the patient, although in the case of ECT and psychosurgery only in life-threatening situations. This notwithstanding, the Mental Health Act stipulates that, whenever possible, the treatment must be in accordance with the wishes of the patient. When this is not possible owing to the psychiatric condition of the patient, the Act defines in detail the preconditions for various restrictions and compulsory measures, such as seclusion, body searches and confiscation of personal possessions. If patients are unhappy with their treatment or restrictions, they have recourse to the chief executive officer of the hospital, the courts, the Regional State Administration Agency, the National Supervisory Authority of Welfare and Health and, in the final instance, the parliamentary ombudsman. Although no comprehensive statistics exist, it can be estimated that these administrative bodies review hundreds of complaints annually concerning psychiatric care. In the majority of cases the decisions made by the treating physicians are upheld (THL, 2012).

Fig. 1. The decision-making process for involuntary treatment. The process involves three doctors: one for each step.

The legal provisions relevant to forensic psychiatry

According to Criminal Law 39/1889, perpetrators of a crime are not criminally responsible if, at the time of the act, they were not able to understand the factual nature or unlawfulness of their act, or their ability to control their behaviour was decisively weakened owing to mental illness, severe mental deficiency, a serious mental disturbance or a serious disturbance of consciousness.

If necessary, the question of responsibility can be assessed in a court-ordered forensic examination, the most common form of which is the so-called full mental state examination. These examinations are performed in the most serious cases, namely violent and sexual crimes, at a rate of around 120–130 a year. If a person is not fully absolved from responsibility according to the terms of the law, but their ability to understand the nature of the act or its illegality or their ability to control their actions is, for the same reasons, severely impaired, this can result in a less severe sentence due to diminished responsibility. However, although the questions of responsibility and need for treatment usually coincide, the need for treatment is separately assessed, regardless of the level of responsibility.

Discussion

The rate of involuntary hospitalisation in Finland has been high in comparison with other countries in Western Europe (Salize & Dressing, 2004), but has gradually begun to fall during the past decade. In 2010, 8455 people were subject to compulsory psychiatric hospitalisation and 2610 people were subject to compulsory treatment measures, including seclusion and involuntary medication (Rautiainen & Pelanteri, 2012). Thus, Finnish legislation and psychiatric units still prioritise the need for treatment over personal autonomy, particularly on the basis of risk of self-harm (Tuohimaki et al, 2003). Importantly, in a Finnish study focusing on seclusion, psychiatric patients themselves viewed compulsory measures as necessary in a psychiatric hospital setting (Keski-Valkama et al, 2010). Similarly, at the risk of paternalism, Finnish legislation emphasises the responsibility of the medical profession in ultimately deciding on treatment, albeit within clearly defined legal constraints. Although Finland is a liberal democracy, the population is as yet culturally quite homogeneous and holds a relatively high regard for expert opinion, somewhat counteracting pressures towards less medical discretion and stronger legal regulation of psychiatric treatment, of the kind which has been adopted in the USA and elsewhere in the EU. That said, although Finnish mental health law is generally seen to work well in practice (Putkonen & Völlm, 2007), the treatment of psychiatric disorders, which by their nature tend not to adhere to rigid legal concepts, continues to cause debate, if not controversy, between various interest groups, professions and within the psychiatric community.

References

- Abdalla-Filho, E. & Bertolote, J. M. (2006) Sistemas de psiquiatria forense no mundo [Forensic psychiatric systems in the world]. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 28 (suppl. 2), S56–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eronen, M., Repo, E., Vartiainen, H., et al. (2000) Forensic psychiatric organization in Finland. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 23, 541–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keski-Valkama, A., Koivisto, A.-M., Eronen, M., et al. (2010) Forensic and general psychiatric patients’ view of seclusion: a comparison study. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry and Psychology, 21, 446–461. [Google Scholar]

- Njenga, F. G. (2006) Forensic psychiatry: the African experience. World Psychiatry, 5(2), 97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putkonen, H. & Völlm, B. (2007) Compulsory psychiatric detention and treatment in Finland. Psychiatric Bulletin, 31, 101–103. [Google Scholar]

- Rautiainen, H. & Pelanteri, S. (2012) Tilastoraportti: psykiatrinen erikoissairaanhoito 2010 [Statistical Report: Specialised Psychiatric Care 2010]. Suomen virallinen tilasto (SVT) 3/12 Available at http://www.stakes.fi/tilastot/tilastotiedotteet/2012/Tr03_12.pdf (accessed March 2012).

- Salize, H. J. & Dressing, H. (2004) Epidemiology of involuntary placement of mentally ill people across the European Union. British Journal of Psychiatry, 184, 163–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THL [Terveyden ja hyvinvoinnin laitos; Department of Health and Welfare] (2012) Kantelu aluehallintovirastoon tai Valviraan [Submitting a Complaint to the Regional State Administration Agency or the National Supervisory Authority of Welfare and Health]. Available at http://www.thl.fi/fi_FI/web/potilasturvallisuus-fi/kantelu-aluehallintovirastoon-tai-valviraan (accessed May 2012).

- Tuohimaki, C., Kaltiala-Heino, R., Korkeila, J., et al. (2003) The use of harmful to others-criterion for involuntary treatment in Finland. European Journal of Health Law, 10, 183–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]