Abstract

Background:

A large number of patients live with undiagnosed HIV and/or hepatitis C despite broadened national screening guidelines. European studies, however, suggest many patients falsely believe they have been screened during a prior hospitalization. This study aims to define current perceptions among trauma and emergency general surgery (EGS) patients regarding HIV and hepatitis C screening practices.

Methods:

Prospective survey administered to adult (>18 years old) acute care surgery service (trauma and EGS) patients at a Level 1 academic trauma center. The survey consisted of 13 multiple choice questions: demographics, whether admission tests included HIV and hepatitis C at index and prior hospital visits and whether receiving no result indicated a negative result, prior primary care screening. Response percentages calculated in standard fashion.

Results:

One hundred and twenty-five patients were surveyed: 80 trauma and 45 EGS patients. Overall, 32% and 29.6% of patients believed they were screened for HIV and hepatitis C at admission. There was no significant difference in beliefs between trauma and EGS. Sixty-eight percent of patients had a hospital visit within 10 years of these, 49.3% and 44.1% believe they had been screened for HIV and hepatitis C. More EGS patients believed they had a prior screen for both conditions. Among patients who believed they had a prior screen and did not receive any results, 75.9% (HIV) and 80.8% (hepatitis C) believed a lack of results meant they were negative. Only 28.9% and 23.6% of patients had ever been offered outpatient HIV and hepatitis C screening.

Conclusions:

A large portion of patients believe they received admission or prior hospitalization HIV and/or hepatitis C screening and the majority interpreted a lack of results as a negative diagnosis. Due to these factors, routine screening of trauma/EGS patients should be considered to conform to patient expectations and national guidelines, increase diagnosis and referral for medical management, and decrease disease transmission.

Keywords: Hepatitis C, HIV, patient beliefs, screening tests

INTRODUCTION

In the United States, underdiagnosis of HIV and hepatitis C remains a serious public health issue. More than one million people are living with HIV/AIDS and 14% are currently undiagnosed.[1,2] For hepatitis C, approximately 50% of the 2.2–3.2 million people with the disease are currently unaware of their infection status.[3,4] As a result, screening recommendations have been expanded for both conditions. The US Preventative Task Force recommends that clinicians screen all patients aged 15–65 for HIV as part of routine medical care.[5] The Centers for Disease Control currently recommends that patients born between 1945 and 1965, as well as patients with other risk factors (intravenous drug use, intranasal illicit drug use, and history of incarceration) undergo screening for hepatitis C.[4,6] Given that highly specialized care and effective treatments are available for both diseases, timely patient identification is essential to improve prognosis by providing care at an earlier disease stage and to prevent transmission by patients who are unaware of their infection.[7]

Despite the benefits of early identification and expanded screening criteria, multiple diagnostic barriers currently exist. One such barrier is that many patients falsely believe that they were tested during a prior hospital encounter and thus do not require screening. The magnitude of this effect has not been clearly defined in the literature. Two Swiss studies demonstrated that a significant number of patients incorrectly believed that they had been screened for HIV and in one study, 96% of patients believed that not receiving a result meant that they were HIV negative.[8,9] A single American study currently exists and found that 5.8% of patients falsely believed that they had received HIV testing during their emergency room (ER) visit.[10] These studies have been primarily limited to ER care and have not addressed patient beliefs regarding hepatitis C screening.

Given the increased prevalence of hepatitis C and HIV among the trauma population and those presenting for care to the ER, this patient cohort would be most affected by the erroneous assumption that they had been tested and by the false belief that the lack of a result was equivalent to a negative test result.[11,12,13,14] We hypothesized that a significant proportion of the patients admitted to our acute care surgical service would believe that they had undergone a screening test at a prior admission and/or had received a screening test during their current admission. We also believed that many of these patients would assume that the lack of a test result was the equivalent of a negative test result.

METHODS

The study was approved by the Medical University of South Carolina Institutional Review Board. From January to November 2017, patients were identified and asked to complete a voluntary survey. Eligible patients included adults (>18 years old) admitted through the emergency department to the acute care surgery service of our Level 1 academic trauma center. These patients consisted of trauma and emergency general surgery (EGS) patients. Elective general surgery patients and hospital-to-hospital transfer patients were excluded from the study. The study and survey instrument were explained by a research coordinator or nurse practitioner and verbal consent was obtained. The administrator was available to answer patient questions regarding the survey content. The survey refusal rate was not recorded.

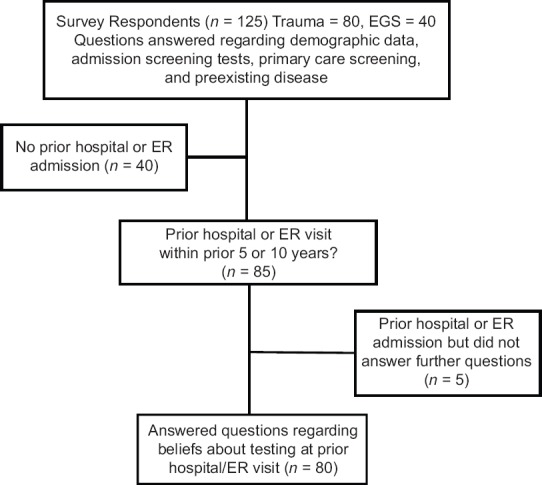

The survey instrument contained 13 multiple-choice questions [Appendix 1]. These questions included patient demographics, beliefs regarding specific tests performed at current admission (alcohol, illegal drugs, other addictive drugs, and sexually transmitted diseases), and whether the patient had experienced a prior hospital admission or ER visit within the last 5 or 10 years. If the patient had a prior hospital or ER visit, the patient was asked questions regarding whether they believed that they received HIV or hepatitis C testing at that time, and if so, the patient was asked if they believed that not receiving a test result at that time was the equivalent of receiving a negative test result [Figure 1]. All the patients were also asked if they had ever been offered a screening test by their primary care for either HIV or hepatitis C and whether they had a known diagnosis of either disease. To maintain survey integrity, HIV or hepatitis C status was based on patient self-reporting and was not verified in the clinical record. These patients were included in the analysis for all questions. SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used to calculate frequencies for all variables and Chi-square tests for selected variables.

Figure 1.

Description of total number of survey responses to various sections of questionnaire

RESULTS

One hundred and twenty-five patients completed the survey. Eighty patients (64%) were admitted secondary to trauma and 45 for an EGS issue. The majority of patients were male (50.8%) and 22% identified as a racial/ethnic minority. Patient ages were: 18–30 = 24%, 31–50 = 31.2%, 51–71 = 36%, and 72 or older = 8.8%. Eight patients reported a prior diagnosis of either hepatitis C or HIV and two did not answer.

The majority of patients (53.7%) believed that they received at least one admission screening test including alcohol or illicit drugs (40%) and some type of infectious disease (36%). Men were more likely to believe that they had received at least one screening test (61% vs. 47%, P = 0.11). There was no difference in screening beliefs among patients that identified as a racial minority versus nonminority (56%, vs. 54%, P = 0.91). A greater percentage of trauma patients (59%) believed that they had received at least one screening test compared to EGS patients (44%, P = 0.12).

Among all patients, 32% believed that they were screened at admission for HIV and 29.6% for hepatitis C. More men believed that they were screened for both HIV and hepatitis C at admission compared to women, but this was not statistically significant [Table 1]. The beliefs regarding admission testing for both HIV and hepatitis C were nearly identical between those that identified as a racial minority versus nonminority. There was no significant difference in testing beliefs between admission for trauma versus EGS conditions with regard to HIV (P = 0.58) or hepatitis C screening (P = 0.89) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Patient beliefs regarding admission and prior hospital-based screening tests for HIV and hepatitis C compared based on gender and race

| Patients | Admit HIV screening test (%) | Admit hepatitis C screening test (%) | Prior HIV screening test (%) | Prior hepatitis C screening test (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender† | ||||

| Male | 38.1 | 34.9 | 61.8* | 48.5 |

| Female | 26.2 | 24.6 | 38.9 | 41.2 |

| Race‡ | ||||

| Minority | 29.6 | 29.6 | 61.5 | 53.9 |

| Nonminority | 33.3 | 30.2 | 48.2 | 41.5 |

*Difference nearly significant (P=0.06), †1 person did not answer gender question: So n=124 for admit hepatitis C/HIV screening, n=70 for prior HIV screening, n=67 for prior hepatitis C screening, ‡2 people did not answer race question: So, n=123 for admit hepatitis C/HIV screening, n=69 for prior HIV screening, n=66 for prior hepatitis C screening

Eighty-five patients (68%) had a prior admission within 10 years and 56% (n = 70) of patients were admitted within the prior 5 years. A higher but nonstatistically significant percentage of EGS patients (73.3%) had a prior admission compared to trauma (65%, P = 0.34). Of patients with a prior admission, only 80 of 85 patients responded to further questions. Patients who did not answer or answered “not applicable” were removed from further calculations [Table 2].

Table 2.

Patient beliefs regarding admission testing for HIV and Hepatitis C and beliefs regarding whether they were screened at a prior hospital visit (within last 10 years). Responses also analyzed based on type of admission - trauma vs. emergency general surgery (EGS)

| Patients | Admit HIV screening test (n=125) | Admit hepatitis C screening test (n=125) | Prior HIV screening test (n=71)* | Prior hepatitis C screening test (n=68)† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 40 (32.0) | 37 (29.6) | 35 (49.3) | 30 (44.1) |

| Trauma | 27 (33.8) | 24 (30.0) | 20 (46.5) | 18 (42.9) |

| EGS | 13 (28.9) | 13 (28.9) | 15 (53.6) | 12 (46.2) |

*Nine patients answered N/A - Removed, †12 patients answered N/A - Removed. N/A: Not available, EGS: Emergency general surgery

Among respondents with a prior admission, a greater percentage believed that they were screened at that admission for HIV (49.3%) than hepatitis C (44.1%) [Table 2]. A much larger portion of men (61.8%) believed that they had received HIV screening compared to women (38.9%), which neared statistical significance (P = 0.06). For hepatitis C, men were slightly more likely to believe that they had been screened (P = 0.55) [Table 1]. Minority patients were much more likely to believe that they were screened for both HIV (61.5% vs. 48.2%, P = 0.39) and hepatitis C (53.9% vs. 41.5%, P = 042) [Table 1]. EGS patients were slightly more likely to believe that they had been screened for HIV (P = 0.56) and hepatitis C (P = 0.79) [Table 2].

Among patients who believed that they had a prior hospital-associated screening test, 75.9% (22/29) interpreted the lack of an HIV result as equivalent to a negative test result. For hepatitis C, 80.8% (21/26) interpreted the lack of a result as a negative test result. Patients who did not answer or answered “not applicable” were removed from this calculation. Women were more likely to interpret lack of results as a negative test result for both HIV (83.3% vs. 70.6%, P = 0.66) and hepatitis C (91.7% vs. 71.4%, P = 0.33). For HIV, minority patients were slightly more likely to equate lack of results to a negative result (85.7% vs. 72.7%, P = 0.65). The results for hepatitis C were identical between minority and nonminority patients (80%). Overall, among patients with a prior hospital visit (n = 85), these data translate into approximately one-quarter of patients (HIV = 25.9%, hepatitis C = 24.7%) who believe that they were screened and that their lack of results was equivalent to being negative for disease.

Despite the current national guidelines, only 28.9% of all patients reported being offered HIV screening by their primary care provider. For hepatitis C, 23.6% of patients were offered outpatient screening. Per age group, HIV testing was offered to 40.7% of 18–30 year olds, 36.4% of 31–50, 23.7% of 51–71, and 25% of those 72 or older. For hepatitis C, the following were offered outpatient screening: 37% of 18–30 year olds, 21.2% of 31–50 year olds, 13.2% of 51–71 year olds, and 38% of those 72 or older. Patients responding “not applicable” or not providing an answer were removed from the calculation.

DISCUSSION

The identification of patients with HIV and hepatitis C is an important public health issue, but successful screening programs face many barriers. Our study clearly demonstrates that one such barrier is erroneous patient beliefs regarding admission and prior screening tests. Approximately one-third of trauma and EGS patients believed that they had received admission screening for HIV and hepatitis C despite never receiving information to substantiate that belief. The majority of these patients had a prior hospital visit within 10 years, and of these, an even greater proportion believed that they had received screening at that time. The most concerning result was that the vast majority of these patients believed that the failure to receive a test result was equivalent to receiving a negative test result. These false beliefs can result in patients continuing high-risk behaviors, refusing future testing that they would deem redundant, and incorrectly reporting their screening history to medical professionals who then fail to offer appropriate screening tests.[15,16]

Our results are supported by data described in several European studies. Favre-Bulle et al. demonstrated that 27% of Swiss patients who presented to the emergency department and had blood drawn incorrectly believed that they had been screened for HIV.[8] In a second Swiss study, Albrecht et al. examined patients presenting for elective orthopedic surgeries and found that 38% of patients incorrectly believed that they had been tested for HIV. Among the patients that falsely believed that they were screened, 96% believed that not receiving a test result was the same as receiving a negative test result.[9] These results were very similar to our findings, despite the differences in clinical settings. In the United States, there is very limited data regarding similar patient beliefs. A single study by Khakoo et al. found that 5.8% of urban emergency department patients erroneously believed that they had received an HIV test.[10] The study failed to exclude patients who had not undergone a blood draw and did not examine patient beliefs regarding the relationship between not receiving test results and negative disease status. As far as we are aware, there have been no other studies examining patient beliefs regarding admission testing for hepatitis C in either Europe or the United States.

Determining patient beliefs regarding prior HIV and hepatitis C screening is particularly important among patients presenting through the emergency department. A higher prevalence of both diseases has been demonstrated among trauma and emergency department patients and many do not have traditional risk factors or fall outside of centers for disease control (CDC) testing guidelines.[12,13,14,17,18] The increased prevalence in this patient population is likely due to a lack of access to routine outpatient care. This theory is supported by Kelen et al. which found that uninsured patients seen in the emergency department had a higher prevalence of HIV than insured patients.[13] The use of routine HIV testing in both low- and high-prevalence settings has been shown to be cost-effective and to influence subsequent patient's behavior.[19,20] Patients who are aware of their HIV-positive status decrease high-risk behaviors, thereby decreasing transmission risk even without medical therapy.[20] Certainly, patients who believe they have received a prior HIV test are less likely to consent to a new test and providers may be less likely to offer testing to patients that self-report a prior test.[10] Due to the significant percentage of our patients who reported a prior hospital admission and believed that they had received screening at that time, this could translate into an appreciable portion of patients who would erroneously refuse or be denied appropriate testing.

In addition to the barrier created by erroneous patient beliefs, our data also suggest that primary care providers are failing to offer appropriate screening tests for both diseases. Despite the current national recommendations that providers screen all patients aged 15–65 for HIV, only 28.9% of our patients reported being offered an outpatient screening test. For hepatitis C, despite the recommendation that all patients born between 1945 and 1965 receive screening, only 13.2% of the target age group (51–71) had been offered screening by their primary care provider. The lack of primary care screening may be due to several factors, such as limited or no patient interaction with a designated provider, erroneous patient reports that they were screened during a hospital or ER visit, or lack of provider knowledge regarding the current recommendations. Regardless of the reason, a large portion of patients is failing to receive recommended screening from their primary care physicians. Given the large percentage of patients with a prior emergency department or hospital visit and prior studies showing the cost-effectiveness of broadened screening programs, adoption of routine emergency department screening could help bridge the gap in health care experienced by this patient population.[21,22]

Although our data are compelling, it has several limitations. Data were collected at a single institution, has a relatively small sample size, and is not a random sample since patients had to agree to participate. However, despite the small size, the participants provided a solid demographic representation, and the results were consistent with the European literature. Our data could also be limited by patient education, health literacy, and comprehension of the survey instrument. These effects were mitigated by the availability of research staff to answer questions, but this cannot completely negate patient misunderstanding. Due to the anonymous nature of the survey, we also had to rely on patient self-reporting of disease positivity and the very small number of disease-positive individuals was not removed from the analysis. Many of these shortcomings could be overcome by continuing data collection, assessing patient education level, and expanding data collection to other institutions to ensure its generalizability.

CONCLUSIONS

Our data suggest that a significant portion of patients believed that they are routinely screened for hepatitis C and HIV at admission and a large portion are not receiving recommended screening in the primary care setting. Due to these factors, routine screening of trauma and EGS patients should be considered during nonelective hospital admissions. Adoption of routine screening for hepatitis C and HIV would conform to patient expectations, increase diagnosis and referral for medical management, improve clinical outcomes with earlier referral, and decrease overall disease transmission.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

APPENDIX

Appendix 1: Survey instrument

ID #: _______ ? Trauma ? General Surgery

You are being asked to participate in a brief survey for research purposes. The purpose of this research study is to understand what types of testing patients think they receive in the Emergency Department. The survey should take no more than 5 min and involves answering 13 questions. The survey is anonymous – we will not record your name, your medical record number, or look at your medical record in connection with the survey. You are free to skip any questions that you prefer not to answer. Your participation in this survey is voluntary, and your decision whether to participate will not affect your medical care. This study is being conducted by Dr. Alicia Privette, from the Division of General Surgery, and Dr. Lauren Richey, from the Division of Infectious Disease, at the Medical University of South Carolina. If you have any questions, please contact Alicia Privette, MD, at 843-792-8395.

-

When you were admitted to this hospital, what conditions do you believe we tested for when we drew blood for laboratory tests? (select all that apply)

- Alcohol

- Illegal drugs/drugs of abuse (marijuana, cocaine, IV drugs, etc.)

- Other addictive drugs (narcotics such as oxycodone and methadone or benzodiazepines such as xanax and valium)

- HIV

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Other sexually transmitted infections

- None of the above

-

Before this current visit, have you been seen in an Emergency Department or admitted to a hospital in the last 10 years?

- Yes

- No (skip to question 8)

-

Before this current visit, have you been seen in an Emergency Department or admitted to a hospital in the last 5 years?

- Yes

- No

-

If yes to either question 2 or 3, do you believe you were screened for HIV at that time?

- Yes

- No (skip to question 6)

- Not applicable (skip to question 6)

-

If yes to question 4, do you believe that you were screened for HIV during a past visit and that since you did not specifically receive any results regarding HIV, that you must therefore be HIV negative?

- Yes

- No

- Not applicable

-

If yes to either question 2 or 3, do you believe you were screened for hepatitis C at that time?

- Yes

- No (skip to question 8)

- Not applicable (skip to question 8)

-

If yes to question 6, do you believe that you were screened for hepatitis C during a past visit and that since you did not specifically receive any results regarding hepatitis C, that you must therefore be hepatitis C negative?

- Yes

- No

- Not applicable

-

Have you ever been offered a screening test for HIV by your regular physician/doctor's office?

- Yes

- No

- Not applicable

-

Have you ever been offered a screening test for hepatitis C by your regular physician/doctor's office?

- Yes

- No

- Not applicable

-

Do you have a known diagnosis of hepatitis C or HIV prior to this hospital admission?

- Yes

- No

- I would prefer not to answer

-

Are you:

- Male

- Female

-

How old are you?

- 18–30

- 31–50

- 51–71

- 72 or older

-

Do you identify as a racial or ethnic minority?

- Yes

- No

Please place your completed survey in the envelope provided and return to the study team member.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control. HIV in the United States Fact Sheet. 2011. Nov, [Last accessed on 2015 Mar 12]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/resources/factsheets/PDF/us.pdf .

- 2.Centers for Disease Control. HIV/AIDS, Basic Statistics. [Last accessed on 2015 Mar 12; Last updated on 2015 Jan 16]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/statistics.html .

- 3.Denniston MM, Jiles RB, Drobeniuc J, Klevens RM, Ward JW, McQuillan GM, et al. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, national health and nutrition examination survey 2003 to 2010. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:293–300. doi: 10.7326/M13-1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C. [Last update on September 2017 and Last accessed on 2017 Nov 20]. Available from: http://www.hcvguidelines.org .

- 5.Final Recommendation Statement: Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Infection: Screening. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. [Last update on December 2016 and Last accessed on 2017 Nov 20]. Available from: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/humanimmunodeficiency-virus-hiv-infection-screening .

- 6.Smith BD, Morgan RL, Beckett GA, Falck-Ytter Y, Holtzman D, Teo CG, et al. Recommendations for the identification of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among persons born during 1945-1965. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2012;61:1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dieffenbach CW, Fauci AS. Universal voluntary testing and treatment for prevention of HIV transmission. JAMA. 2009;301:2380–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Favre-Bulle T, Baudat D, Darling KE, Mamin R, Peters S, Cavassini M, et al. Patients' understanding of blood tests and attitudes to HIV screening in the emergency department of a Swiss teaching hospital: A cross-sectional observational study. Swiss Med Wkly. 2015;145:w14206. doi: 10.4414/smw.2015.14206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albrecht E, Frascarolo P, Meystre-Agustoni G, Farron A, Gilliard N, Darling K, et al. An analysis of patients' understanding of 'routine' preoperative blood tests and HIV screening. Is no news really good news? HIV Med. 2012;13:439–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2012.00993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khakoo NM, Lindsell CJ, Hart KW, Ruffner AH, Wayne DB, Lyons MS, et al. Patient perception of whether an HIV test was provided during the emergency department encounter. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2014;13:506–10. doi: 10.1177/2325957414520718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaplan AJ, Zone-Smith LK, Hannegan C, Norcross ED. The prevalence of hepatitis C in a regional level I trauma center population. J Trauma. 1992;33:126–8. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199207000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Rapid HIV testing in emergency departments – three U.S. Sites, January 2005-march 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:597–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelen GD, Hexter DA, Hansen KN, Tang N, Pretorius S, Quinn TC, et al. Trends in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection among a patient population of an inner-city emergency department: Implications for emergency department-based screening programs for HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:867–75. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.4.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lyss SB, Branson BM, Kroc KA, Couture EF, Newman DR, Weinstein RA, et al. Detecting unsuspected HIV infection with a rapid whole-blood HIV test in an urban emergency department. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44:435–42. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31802f83d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ubhayakar ND, Lindsell CJ, Raab DL, Ruffner AH, Trott AT, Fichtenbaum CJ, et al. Risk, reasons for refusal, and impact of counseling on consent among ED patients declining HIV screening. Am J Emerg Med. 2011;29:367–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown J, Kuo I, Bellows J, Barry R, Bui P, Wohlgemuth J, et al. Patient perceptions and acceptance of routine emergency department HIV testing. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(Suppl 3):21–6. doi: 10.1177/00333549081230S304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsieh YH, Rothman RE, Laeyendecker OB, Kelen GD, Avornu A, Patel EU, et al. Evaluation of the centers for disease control and prevention recommendations for hepatitis C virus testing in an urban emergency department. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:1059–65. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Monitoring Selected National HIV Prevention and Care Objectives by Using HIV Surveillance Data-United States and 6 Dependent Areas-2011. [Last accessed on 2017 Nov 20];HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2013 Oct;18 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/surveillance/ [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paltiel AD, Weinstein MC, Kimmel AD, Seage GR, 3rd, Losina E, Zhang H, et al. Expanded screening for HIV in the united states – An analysis of cost-effectiveness. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:586–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa042088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marks G, Crepaz N, Senterfitt JW, Janssen RS. Meta-analysis of high-risk sexual behavior in persons aware and unaware they are infected with HIV in the United States: Implications for HIV prevention programs. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39:446–53. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000151079.33935.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coward S, Leggett L, Kaplan GG, Clement F. Cost-effectiveness of screening for hepatitis C virus: A systematic review of economic evaluations. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011821. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dowdy DW, Rodriguez RM, Hare CB, Kaplan B. Cost-effectiveness of targeted human immunodeficiency virus screening in an urban emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18:745–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]