Abstract

Rationale: Antiretroviral therapy can effectively suppress HIV-1 replication in the peripheral blood to an undetectable level. However, elimination of the latent virus in reservoirs remains a challenge and is a major obstacle in the treatment of HIV-1-infected patients. Exosomes exhibit huge promise as an endogenous drug delivery nanosystem for delivering drugs to solid tissues given their unique properties, including low immunogenicity, innate stability, high delivery efficiency, and most importantly the ability to penetrate solid tissues due to their lipophilic properties.

Methods: We engineered and expressed the scFv of a high affinity HIV-1-specific monoclonal antibody, 10E8, on the exosomal surface (10E8scFv-exos). Subsequently, the 10E8scFv-exos were loaded with curcumin (Cur), a chemical that kills HIV-1-infected cells, or miR-143, an apoptosis-inducing miRNA. We tested the ability of 10E8scFv-exos to deliver cargo to Env+ target cells and tissues, as well as their ability to suppress HIV-1 infection.

Results: 10E8scFv-exos efficiently targeted CHO cells expressing a trimeric gp140 on their surface (Env+ cells) in vitro, as demonstrated by confocal imaging and flow cytometry. 10E8scFv-exos loaded with Cur or miR-143 showed specific killing of Env+ cells. In addition, 10E8scFv-exos loaded with Cur or miR-143 could suppress p24 expression in an HIV-1 latency cell line ACH2 and in PBMCs from an ART-treated HIV-1-infected patient. In an NCG mouse model grafted with tumorigenic Env+ CHO cells and which had developed solid tissue tumors, intravenously injected 10E8scFv-exos targeted the Env-expressing tissues and delivered Cur to induce a strong suppression of the Env+ tumor growth with low toxicity.

Conclusion: In principle, engineered exosomes can deliver anti-HIV agents to solid tissues by specifically targeting cells expressing viral envelop proteins and inducing cell killing, suggesting that such an approach could be developed for eradicating virus-infected cells in tissue reservoirs.

Keywords: HIV-targeted delivery system, exosome, extracellular vesicles, chemotherapy, RNAi-therapy

Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection remains a global public health challenge, although antiretroviral therapy (ART) has been highly effective in suppressing viral replication. The current generation of ARTs is limited by its inability to inhibit non-replicating viruses and to penetrate solid tissues where the latent viral reservoirs reside 1. Therefore, latent viral reservoirs pose a huge challenge to the eradication of the virus 2.

Extracellular vesicles (EVs), including exosomes, microvesicles, and apoptotic bodies, depending on the size of the structures, are nano-sized, membrane-enveloped structures containing mostly proteins and nucleic acids 3. Exosomes are generally defined as 40-150 nm in diameter and are released from cells after fusion of the multivesicular bodies (MVBs) with the plasma membrane 4. Exosomes are intraluminal vesicles secreted by a variety of cell types and are present in almost all biological fluids, functioning as natural transporters of bioactive molecules between the exosome-producing and recipient cells and playing various roles, including immunomodulation, regulating the activity of target cells and cell-cell communication 5, 6. Exosomes are considered as potential drug delivery vehicles due to their biostability, potential allogenic nature, and lipophilic properties 7. Besides transporting endogenous substances, reports have shown that exosomes can be used as naturally derived nanovesicles to deliver exogenous RNAs (siRNAs and miRNAs) to target tissues or cells in vivo, leading to gene knockdown or inhibiting tumor growth in mouse models 8-10. More importantly, exosome-mediated nucleic acid delivery in vivo did not induce short-term innate immune activation nor cause overt side effects 11. Furthermore, small protein or peptide could be introduced to the surface of exosomes for tissue-specific targeting 12. Cheng et al. found that exosomes engineered with αCD3/αEGFR-specific antibody scFv expressed on their surface could effectively target CD3+ T cells and EGFR+ cancer tissue to deliver therapeutic cargo 13.

HIV-1 envelop protein (Env) is widely expressed on the surface of HIV-1-infected cells 14. To cure HIV-1 infections, a big challenge is eliminating the persistent, quiescent HIV-1 infections within a small population of long-lived CD4+ T cells, which are a latent pool of HIV-1-infected cells 15. The strategy to eradicate HIV-1 infection is to disrupt latency and induce viral antigen expression in cells by activators, such as HDAC inhibitors, to allow the action of antivirals 16. Even on the latently-infected cells or tissues, Env would be expressed once they received stimulation, and the latency would therefore be disrupted 17. We hereby engineered exosomes that express a single chain variable fragment (scFv) of a high affinity HIV-1 Env-specific monoclonal antibody 10E8 to deliver chemotherapeutic drug curcumin (Cur) or apoptosis-inducing miR-143 to the HIV-1-infected cells or tissues, for the elimination of HIV-1 cells. Our study explored the application of engineered EVs to eliminate HIV-1 latently infected cells by using a well-established latent infected model, the ACH2 cell line 18, 19 and PBMCs from chronically HIV-1-infected patients. In addition, we explored the feasibility of delivering the Cur-loaded exosomes via an intravenous route to target an env-expressing tumor in a humanized mouse model 20.

Materials and Methods

Exosome isolation

Prior to cell culture, DMEM containing 20% FBS was centrifuged at 120,000 g for 2 h to deplete serum exosomes. HKT293T cells, used for exosome production, were cultured in 30 ml 5% exosome-depleted FBS in a 150 mm dish and maintained in 5% CO2 at 37°C for 48 h. Exosomes were isolated from the 30 mL harvested supernatant according to a previous report 21. Briefly, the supernatant was centrifuged at 300 g for 10 min, 1200 g for 20 min, and 10,000 g for 30 min at 4°C to remove cells and cellular debris and then filtered through a 0.22 μm filter (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The filtrate was centrifuged at 110,000 g for 120 min at 4°C in a Type Ti70 rotor, using an L-80XP ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). The exosome pellet was resuspended in PBS and ultracentrifuged again at 110,000 g for 120 min 22. The pelleted exosomes were resuspended in PBS and analyzed using a Micro BCA Protein Assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) or by western blotting analysis of exosomal markers using antibodies specific for Alix, Tsg101, and endoplasmic reticulum marker GM130 (Proteintech, Wuhan, China).

Characterization of exosomes by nanoparticle tracking analysis

Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) was performed with a NanoSight LM10-HSB instrument (A&P Instrument Co., UK) using purified exosomes (100 mL; 10 ng/mL). The mean size and size distribution data were captured and analyzed with the NTA 2.2 Analytical Software Suite. All procedures were performed at room temperature.

Construction of 10E8scFv-pDisplay plasmid and transfection

We engineered the vector by replacing the 10E8 scFv with 10E8scFv-pDisplay, which was obtained by insertion of the annealing synthesized single-stranded sequences for 10E8scFv with restriction enzymatic sites BgIII and SaII. HEK293T cells were transfected with the vector expressing the 10E8-pDisplay fusion proteins using PEI transfection reagent (Invitrogen, USA).

Co-culture of exosomes and cells

To investigate the uptake of 10E8scFv-exos by HIV-1 Env+ expressing CHO cells (Env+ CHO), which were generated by using a Env expressing vector described previously (Supplementary S10, S11) 23, the cells were co-cultured in the same dish and incubated with 10 mM DiI-perchlorate (DiI)-labeled exos or DiI-labeled 10E8scFv-exos at 37°C for 30 min 24. The cells were washed and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and nuclei were stained with 5 mM Hoechst 33342 and imaged with a fluorescence microscope A Ti-E microscope (Nikon). Fluorescence at the center wave-length/bandwidths of 440/44, 521/26, and 607/34 was collected using a 60× oil immersion lens and recorded with an Olympus FluoView FV10i (Tokyo, Japan) confocal microscope. The images were processed and analyzed using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MA, USA). ACH2 was is a gift from Prof. Kai Deng at Sun Yet-Sen University.

Inhibition of 10E8scFv-exos binding to Env+ cells by soluble 10E8 IgG

To test binding, exosomes were labeled by DiI. The cells were then pre-incubated with soluble 10E8 IgG (10E8; 20 μg), which was a gift from Prof. Jinghe Huang at Fudan University, in DMEM before DiI-labeled exosomes were loaded. To evaluate the functional relevance of 10E8 for 10E8scFv-exos and Env+ cells, scavenging assays were performed on Env+ cells for an increasing time in the presence or absence of 10E8.

Loading exosomes with therapeutic cargo

To load the exosomes with Cur, saponin, exosomes and Cur were mixed and incubated at 37°C for 10 min to ensure the plasma membrane of the exosomes fully recovered. Recovery was assessed by TEM as described above. Exosomes were then washed twice with cold PBS by ultracentrifugation at 120,000 g for 90 min to remove unincorporated free Cur. The loaded exosomes were quantified for encapsulated Cur by detecting intrinsic fluorescence of Cur using a Fluorescence Spectrophotometer F-4600 (HITACHI, Tokyo, Japan) at 530 nm with excitation at 425 nm. To load the exosomes with miRNA, MiR-143 was transfected by Exo-FectTM Exosomes Transfection Reagent (EXFT20A-1, SBI).

Flow cytometry

For fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), exosomes from HEK293T cells were adsorbed onto 4 μm aldehyde-sulphate latex beads (Interfacial Dynamics, Tualatin, OR), incubated with Alexa Fluor PE-conjugated anti-HA tag antibodies, Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-Myc tag antibodies, Alexa Fluor APC-conjugated anti-CD81 antibodies (all BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA), and analyzed on a FACS Calibur system (Becton Dickinson, San Diego, CA).

Western blotting

For western blot analysis, ultracentrifuged exosomal pellets were lysed with RIPA buffer (Cell Signaling Technology) containing a Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Calbiochem). The total protein was determined using a BCA kit, and an equivalent amount (25 μg) of exosomal protein was resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The blots were probed overnight at 4°C with antibodies specific for Alix, Tsg101, HA, GM130 as indicated25. IRDye IgG was used as secondary antibody (1:10,000) for 30 min. Bands were visualized on a Li-COR Odyssey Infrared Imager (Li-COR).

Tumor-bearing mouse model

Six week old female NOD-Prkdcem26Cd52 Il2rgem26Cd22/NJU (NCG) mice were purchased from the Nanjing Institute of Biomedical Research. Env+ CHO cells (2.0 × 106 cells in 100 μL PBS) were transplanted into the mammary fat pads of the mice and allowed to grow to a tumor size of 0.1 cm3 (volume length width2/2, measured with a Vernier caliper). The mice were then randomly divided into different experimental groups as described in the Results. All procedures were approved by the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments of the Health Science Center of Nanjing University (Nanjing, China).

In vivo imaging of xenograft tumors

Mice were anesthetized via isoflurane inhalation, and intraperitoneally injected with 100 μL of 150 mM DiR iodide (DiR)-labeled exosomes. Bioluminescence imaging was performed with an IVIS (Xenogen), 10 min post injection. The section of interest was defined manually, and bioluminescence expressed as photon flux values (photons/s/cm2/steradian). Background photon flux was defined using an area of the tumor that did not receive an intraperitoneal injection of luciferin.

Statistical analysis

All in vitro experiments were performed at least three times. The proliferation assay was performed six times. The results are described as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and comparisons among groups were performed by Tukey's honestly significant difference, or t-test. Tumor growth comparisons were performed by Mauchly's test of sphericity.

Results

Characterization of 10E8scFv-expressing exosomes

We engineered pDisplay-10E8scFv and generated exosomes displaying the scFv of 10E8 (10E8scFv) on the surface (Figure 1A). To generate 10E8scFv-expressing exosomes (10E8scFv-exos), 10E8scFvwas fused to the extra-membrane N terminus of murine pDisplay protein by introducing the HA-10E8-Myc-pDisplay plasmid into HEK293T cells (Figure 1B). We purified exosomes from the culture supernatants of the cells and used nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) to measure exosome diameters. Mock transfected (Exos), transfected HEK293T cells (10E8scFv-exos) were similar in sizes, at 115 and 118 nm, respectively (Figure 2A). Transmission electron microscope (TEM) was used to investigate the morphology of the purified exosomes and a typical exosome structure was observed (Figure 2B). Expression of 10E8scFv on the exosomes was examined using anti-hemagglutinin (HA) antibodies and western blot analysis. A 43 kD band, corresponding to the predicted size of 10E8scFv, was detected (Figure 2C). In addition, FACS was used to measure the surface expression of 10E8scFv on 10E8scFv-exos and showed that 87.6% of the exosome sorted beads displayed 10E8scFv on their outer membranes (Figure 2D), suggesting that majority of the exosomes express 10E8scFv.

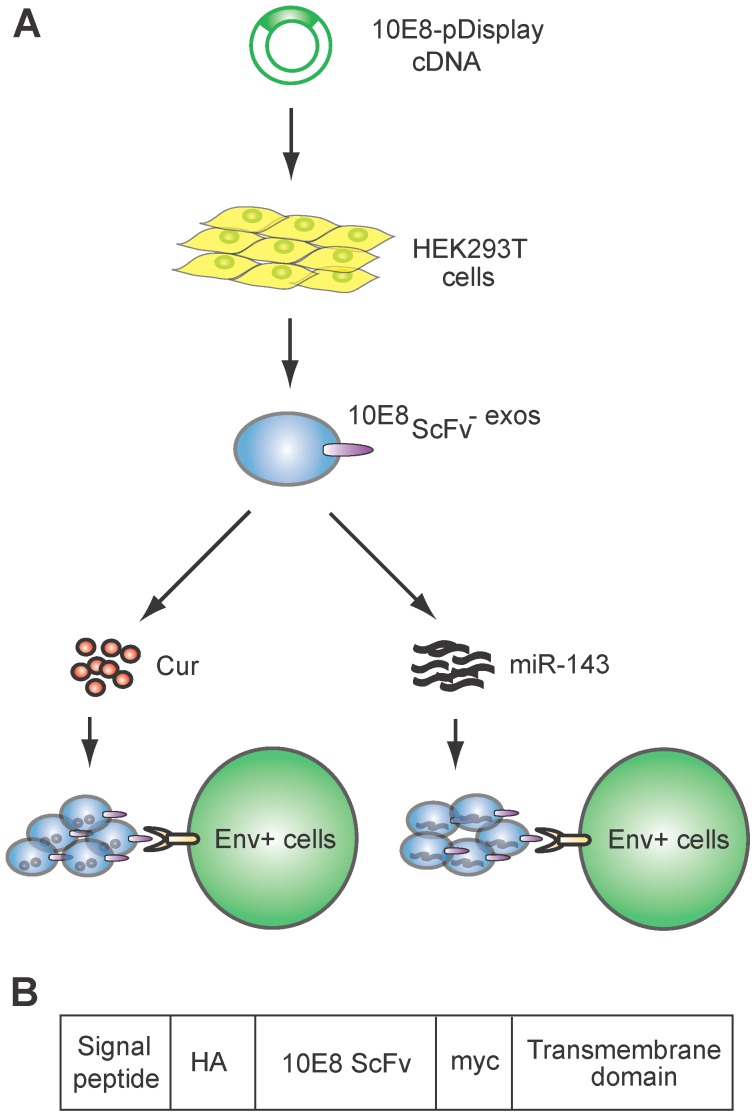

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of exosomes expressing 10E8 single chain fragment and targeting Env+ cells.(A)HEK293T cells were transfected with a plasmid containing the recombinant 10E8scFv-pDisplay. The 10E8scFv-expressing exosomes were loaded with Cur to generate Cur-containing 10E8scFv-exosomes or transfected with miR-143 in order to generate miRNA-containing 10E8scFv-exosomes. The efficacy of engineered exosomes was tested in vitro and in vivo on Env+ cells. (B) Schematic representation of the pDisplay plasmid construct containing scFv of 10E8 monoclonal antibody.

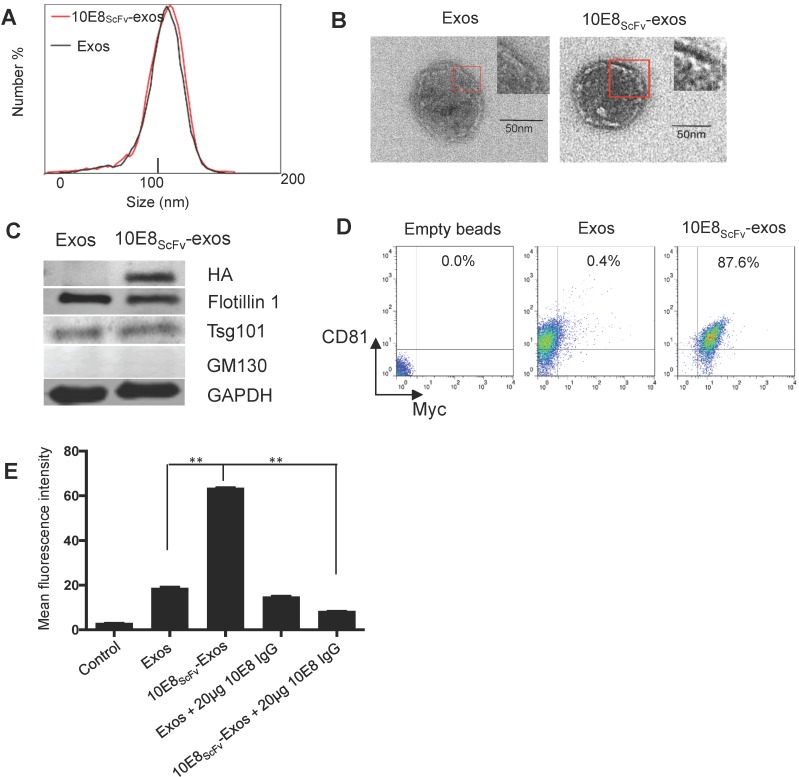

Figure 2.

Characterization of exosomes and 10E8scFv ligands on the surface of the exosomes. (A) Size distributions of Exos, 10E8scFv-exos, and Cur-exos based on NTA measurements. The peak diameters were at 113.4 nm for Exos, and 115 nm for 10E8scFv-exos. (B) TEM images of Exos and 10E8scFv-Exos. Scale bar = 50 nm. (C) Western blots of exosomes extracted from supernatants of HEK293T cells. 10E8scFv-Exos were from the cells that had been transfected with pDisplay encoding 10E8 scFv, HA- tag, and Myc- tag. The quality of each exosome preparation was confirmed by hybridization with clear presence of exosome marker Flotillin 1, Tsg101, whereas absence of Golgi marker GM130. (D) CD81 the surface marker of EVs, as well as Myc- tag of 10E8scFv, were detected by flow cytometry for both Exos and 10E8scFv-Exos. Exos extracted from HEK293T cells were absorbed on latex beads and then were submitted to antibody staining. (E) Binding ability of exosomes to recombinant HIV-1 Env were tested. The exosomes were labeled with the fluorescent agent DiI (exos-DiI) and then were incubated with latex beads conjugated with HIV Env protein. MFI of the latex beads which absorbed exos-DiI was determined by flow cytometry. Additionally, soluble 10E8 IgG were used as a competitive inhibitor to block the binding between exos and Env- conjugated beads, in order to proof the specificity of binding mediated by 10E8scFv- Env interaction. Blank (beads only) and naked Exos served as control in the assay. Data are mean ± SEM from triplicated assays. * p< 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

To confirm that 10E8scFv was incorporated onto the surface of exosomes, we analyzed the binding ability of these exosomes to the Env protein. The 10E8scFv-exos were labeled with the fluorescent agent DiI and the binding of the labeled exosomes to aldehyde-sulfate latex beads conjugated with recombinant HIV-1 Env protein was measured by the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the beads. We observed that the beads treated with 10E8-exos had 3-folds higher MFI than those treated with exosomes only, indicating a specific binding mediated by 10E8-gp160 interaction. Moreover, the binding of 10E8scFv-exos to gp160 was almost completely blocked by 10E8IgG (Figure 2E), confirming that the 10E8scFv-exos binding to gp160 was specifically mediated by 10E8scFv-gp160 interaction.

In vitro targeting of HIV-1 env-expressing cells by 10E8scFv-exos

To investigate whether 10E8scFv-exos specifically target the CHO cells expressing trimeric HIV-1 envelop, we determined the binding efficiency of 10E8scFv-exos to Env+ CHO cells. The exosomes were stained with a lipophilic DiI dye (red) and the Env+ CHO cell membranes with GFP (green). Wild type CHO (Env- CHO) cells and exosomes without 10E8scFv(exos) served as negative controls. Confocal laser-scanning microscopic analysis showed that the red fluorescence merged with green fluorescence on Env+ cells treated with 10E8scFv-exos, indicating that 10E8scFv-exos were adsorbed onto the Env+ CHO cell surface. In contrast, the Env- CHO cells treated with 10E8scFv-exos did not excite any red fluorescence (Figure 3A).

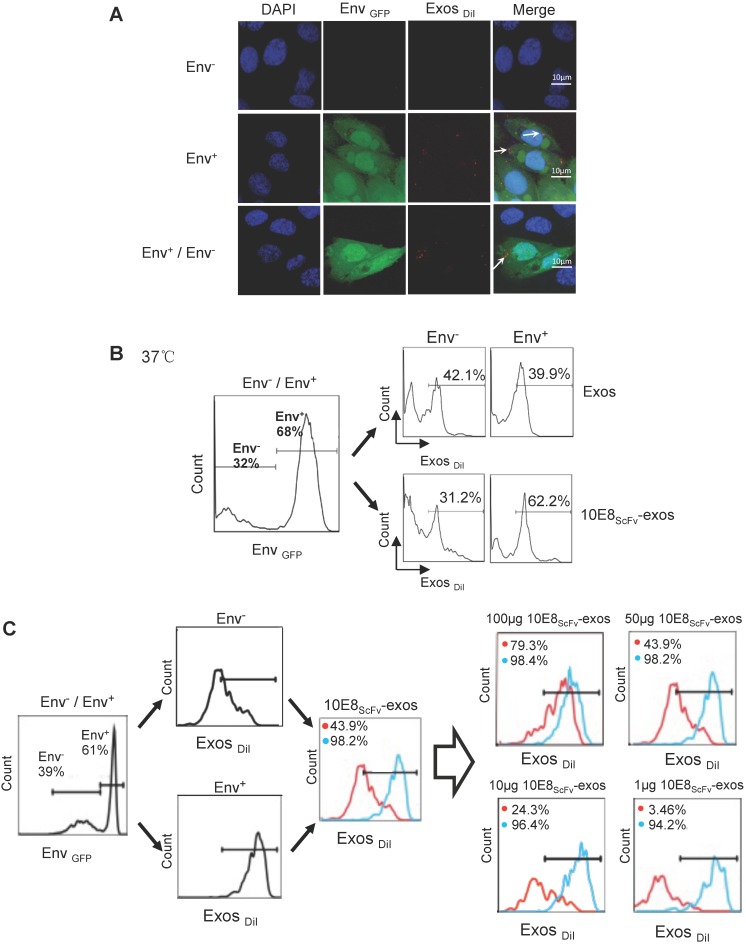

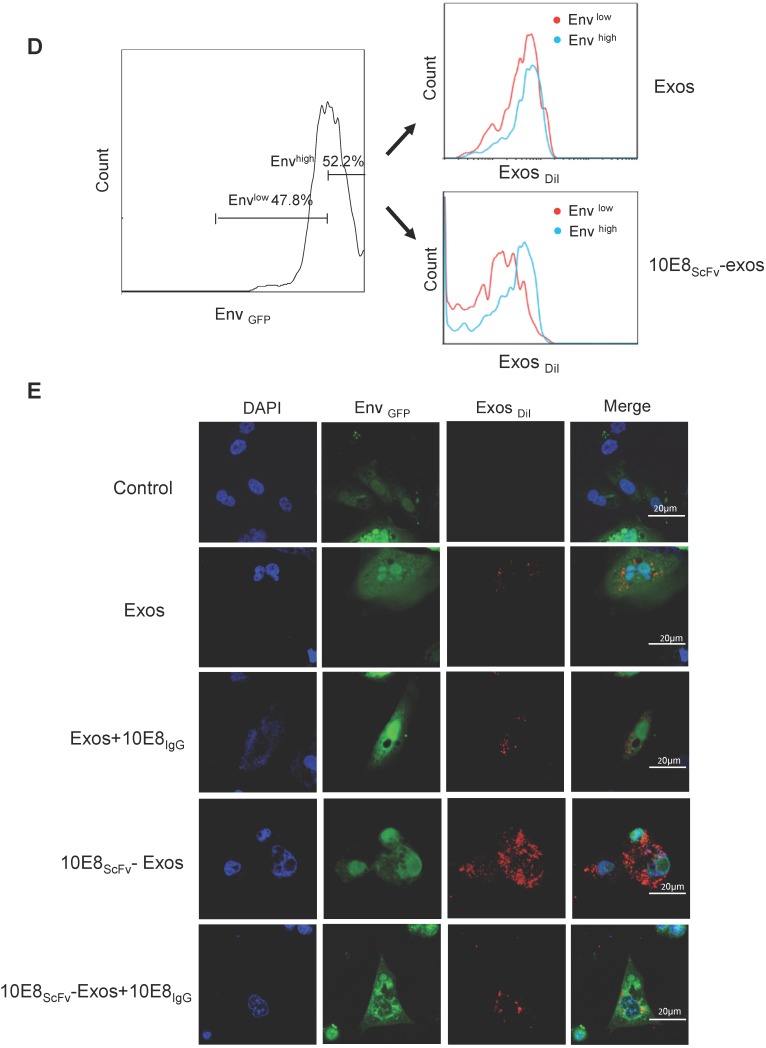

Figure 3.

Binding of 10E8scFv-exos to HIV Env-expressing cells in vitro.(A) Confocal microscopic images show colocalization of the exosomes and the membrane protein Env fused with GFP on the target CHO cells. Significant colocalization of DiI-labeled exosomes (red) with the Env protein was observed. (B) Exosomes purified from HEK293T were labeled with DiI and incubated with Env+ and Env- cells at 37 °C for 24 h. 10E8scFv-exos showed significantly higher binding to Env+ cells compared with the naked exosomes. (C) Env+ cells specifically bound to 10E8scFv-exos. The mixture of Env- and Env+ cells were treated with different doses of 10E8scFv-exos. Binding curve of 10E8scFv-exos to the Env- fraction and the Env+ fraction were measured by the counts of cells that absorbed DiI- labeled exosomes (Exos-DiI). Red line shows the binding curve of the Env- cell fraction; Blue line shows the binding curve of the Env+ cell fraction. Number shows the ratio of Exos-DiI- positive cells in the Env+ fraction (Blue) or Env- fraction (Red). As the dose of 10E8scFv-exos was reduced, Env+ cells retained a high binding curve (Blue) but Env- cells binding curve (Red) decreased. (D) Uptake of DiI-labeled 10E8scFv-exos was compared between that in the Envlow fraction and Envhigh fraction of the Env+ CHO cells. Binding curves are shown by the Exos-DiI counts in each cell fraction. Red line shows the binding curve of the Envlow cell fraction; Blue line shows the binding curve of the Envhigh cell fraction. (E) 10E8scFv-exos adsorption onto Env+ cells could be competitively inhibited by soluble 10E8 IgG. Blank and Exos were used as control.

Furthermore, we incubated the DiI-labeled 10E8scFv-exos or the DiI-labeled control exos with a mixture of Env- and Env+ CHO cells and subsequently measured the binding of exosomes to the cells by counting the DiI-positive cells. Results showed that 62.2% Env+ cells were positive with 10E8scFv-exos, in contrast to 31.2% Env- cells. In contrast, the Env+ and Env- cells exhibited similar DiI-positive counts when being incubated with Exos at 39.9% and 42.1%, respectively (Figure 3B). This result demonstrated the specific targeting of 10E8scFv-exos to Env-expressing cells.

In addition, we treated the mixture of Env- and Env+ cells with different doses of 10E8scFv-exos and measured the DiI-positive cell counts the in Env+ or Env- cell fraction (Figure 3C). As the dose of 10E8scFv-exos was reduced, DiI-positive Env- cells decreased dramatically from 79.3% at 100 μg to 3.46% at 1 μg. In contrast, DiI-positive Env+ cells remained relatively unchanged from 98.4% at 100 μg to 94.2% at 1 μg. These results suggest that the binding of 10E8scFv-exos to the Env+ CHO cells was mediated specifically by the interaction between the HIV-1 envelope protein and 10E8scFv. To further demonstrate the specific targeting of Env+ CHO cells, we measured the relative binding of exosomes to an equal mixture of CHO cells expressing high level Env (52.2% Envhigh) and low level Env (47.8% Envlow) with Env- CHO cells as a control. Differential binding of 10E8scFv-exos to Envhigh and Envlow CHO cells strongly suggests that the increased exosome binding was mediated by 10E8scFv whereas Exos exhibited no differential binding to either Envhigh or Envlow cells (Figure 3D). Further analysis of binding at 4°C showed that exosomes failed to bind the cells (Figure 3A and Figure S1), as expected. We further analyzed the competitive block using soluble 10E8 IgG to compete against 10E8-exos binding to Env+ cells by confocal microscopy. 10E8 IgG strongly inhibited 10E8scFv-exos binding to Env+ cells, whereas it did not affect the non-specific Exos binding (Figure 3E), demonstrating the specificity of the 10E8scFv-Env mediated exosomal fusion with the target cells.

10E8scFv-exos efficiently delivered chemotherapeutic agent Cur into Env+ cells

To investigate if 10E8scFv-exos can specifically deliver biologically active agents to target cells, we loaded 10E8scFv-exos with a chemotherapeutic agent Cur, which is known to have anti-HIV activity and kill cells 26. First, we measured the loading efficiency of Cur to exosomes by FACS, since Cur has inherent green fluorescence (Figure 4A). The encapsulated efficiency (EE) of Cur cargo in the exosomes was determined to be 34.46% by absorbance spectrophotometry (Figure 4B). Stability analysis showed that exosomal Cur was more stable than free Cur (Figure 4C) with the half-life of Cur extended by 3 h. Exosomal delivery of Cur to Env+ cells in vitro was determined by treating Env+ cells with free Cur, Exos-Cur or 10E8scFv-exos-Cur containing an equal amount of Cur and the Cur-induced cell killing was measured by MTT assay. As shown in Figure 4D, after 24 h, 50% of CHO cells and 42% of Env+ CHO cells remained viable in Exos-Cur treatment as compared with 60% of CHO cells and less than 10% Env+ CHO cells viable in 10E8scFv-exos-Cur treatment. In contrast, 90% of CHO or Env+ CHO cells remained alive in free Cur treatment, demonstrating that the increased killing of the Env+ cells by 10E8scFv-exos-Cur is likely mediated by 10E8scFv. We did not observe any killing of the cells by exosomes without Cur, suggesting that exosomes alone do not induce cytotoxicity. Our results revealed enhanced cell-entry efficiency of Cur, mediated by exosomes.

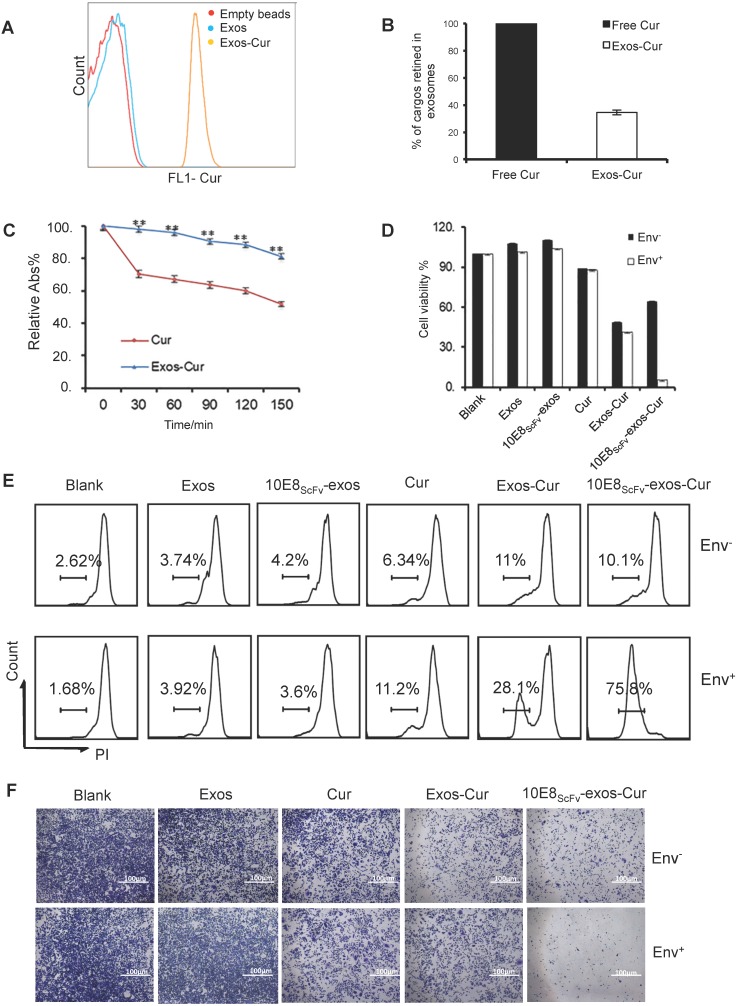

Figure 4.

Characterization of 10E8scFv-exos-Cur. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of exosomal curcumin (Cur). Vesicles were embedded into 4 μm beads. Cur staining was used for detection of exosomes and compared with control exosomes and empty beads. (B) The encapsulated efficiency (EE) of Cur cargoes in the exosomes was determined by absorbance spectrophotometry. EE (%) = ODExos-Cur / ODCur. OD of free Cur in loading process was set as control. (C) Stability of Exos-Cur were tested in comparison with free Cur. Cur and 10E8scFv-exos-Cur were suspended in PBS and incubated in the dark at 37℃. Absorbance curves at 421 nm show their concentration changes for the duration of 150 min. Data are mean ± SEM. Relative Abs (%) = (OD test - OD background ) / (OD start - OD background). (D) In vitro cellular cytotoxicity of Cur delivered by 10E8scFv-exos was tested by the measurement of cell viability. Env+ or Env- cells were incubated with medium (control), Exos, Exos-Cur, 10E8scFv-exos, 10E8scFv-exos-Cur, or free Cur for 24 h. Cur content in various preparations was adjusted to 15 μM. Cell viability was assessed using an MTT assay. 10E8scFv-exos-Cur showed higher cell killing of Env+ cells, as compared with free Cur at the corresponding concentration, which showed almost no cell killing. (E) Env+ or Env- cell lines were treated with medium (control), Exos, Exos-Cur, 10E8scFv-exos, 10E8scFv-exos-Cur, or free Cur for 16 h. Cur content in various preparations was adjusted to 15 μM. Cell death was measured by PI staining and flow cytometry. Numbers shows the ratio of staining of PI in the treated cells. (F) Colony formation of the Env- or Env+ cells treated exosomes were investigated. The sham groups were used as negative control. Data are mean ± SEM.

In addition, the killing of target cells by exosomal Cur was also measured by PI staining and analyzed by FACS. After 12 h, the killing of the Env+ and Env- cells by free Cur were 6.34% and 11.2%, respectively, whereas the killing of the Env+ and Env- cells by Exos-Cur increased to 11% and 28.1%, respectively. Notably, 10E8scFv-exos-Cur induced the strongest killing of Env+ cells at 75.8%, compared with non-specific killing of Env- cells at 10.1% (Figure 4E). Given inhibitory activity of Cur on cell proliferation, we tested the inhibition of cell colony-formation by Cur, Exos-Cur, and 10E8scFv-exos-Cur and showed that 10E8scFv-exos-Cur exhibited the strongest inhibitory activity towards the colony-formation of Env+ cells (Figure 4F).

10E8scFv-exos-mediated miRNA delivery into and induction of Env+ cell apoptosis

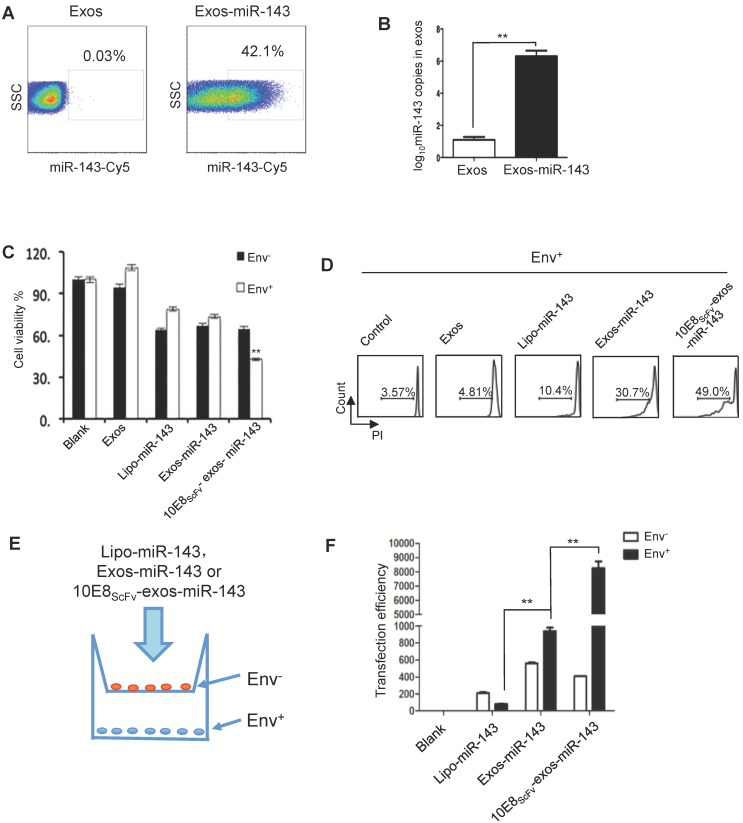

Since miRNAs play multiple regulatory roles in cellular activity and can be introduced into exosomes, we packaged miR-143, an apoptosis-inducing miRNA 27, into exosomes and investigated its ability to induce apoptosis of the target cells in vitro. Exosomes were transfected with miR-143 labeled with florescent Cy5 and were purified. FACS analysis showed that 42.1% of exosomes were successfully loaded with miR-143 (Figure 5A). Approximately 106 copies of miR-143 were determined per 100 μg exosomes by quantitative PCR (qPCR) (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

10E8scFv-exos selectively delivered functional miR-143 into Env+ cells.(A) Percentage of exosomes that contained miR-143-cy5. A hundred micrograms of purified exosomes was used. (B) qPCR analysis of miR-143 levels in the intracellular compartments or purified exosomes of HEK293T cells. (C) In vitro cytotoxicity of miR-143 delivered by 10E8scFv-exos was measured by the viability of cells. Env+ and Env- cells were incubated with medium (control), Exos, Exos-miR-143, 10E8scFv-exos, 10E8scFv-exos-miR-143 or lipo-miR-143 for 24 h and the cell viability was assessed using an MTT assay. (D) Env+ cells were treated with medium (control), Exos, Exos-miR-143, 10E8scFv-exos, 10E8scFv-exos-miR-143, or lipo-miR-143 for 48 h. Cell death was measured by the PI staining method using flow cytometry. (E) Schematic representation of transwell co-culture with Env- cells and Env+ cells are shown. Exosomes of various preparations were added to the top chamber. A porous (0.4 μm) membrane allows transfer of exosomes but precludes direct cell-cell contact. (F) qPCR analysis of miR-143 in the Env+ and Env- cells for 24 h. Mock served as control. Data are mean ± SEM of three independent experiments.

We then evaluated the apoptosis inducing activity of exosomal miR-143 by measuring the viability of Env- and Env+ CHO cells which were treated with Lipo-miR-143, Exos-miR-143, or 10E8scFv-exos-miR-143 (Figure 5C). Less than 35% of the Lipo-miR-143 or Exos-miR-143 treated cells were killed, reflecting the basal level of apoptosis due to the non-specific delivery of the apoptotic miR-143 by lipophilic vectors. Notably, 10E8scFv-exos-miR-143 induced about 60% apoptotic in the Env+ target cells, as compared with about 35% in Env- CHO cells. This differential induction of apoptosis was further substantiated by FACS analysis of PI staining, as shown in Figure 5D.

To further demonstrate the selective absorption and entry of 10E8scFv-exos-miR-143 onto Env+ cells, Lipo-miR-143, Exos-miR-143 or 10E8scFv-exos-miR-143 was added to the Env- or Env+ cells cocultured in transwell as depicted in Figure 5E. The differential entry of 10E8scFv-exos-miR-143 into either Env- or Env+ cells was measured by qPCR analysis of the relative miR-143 quantity in each cell compartment (Figure 5F). As shown in Figure. 5F, 20-fold higher miR-143 was detected in Env+ cell compartment than in the Env- cells. In contrast, comparable levels of miR-143 were detected in Env+ and Env- cell compartments when cells were treated with Exos-miR-143. Together these results suggest that 10E8scFv-exos mediated the selective transfer of miRNA into the Env+ cells.

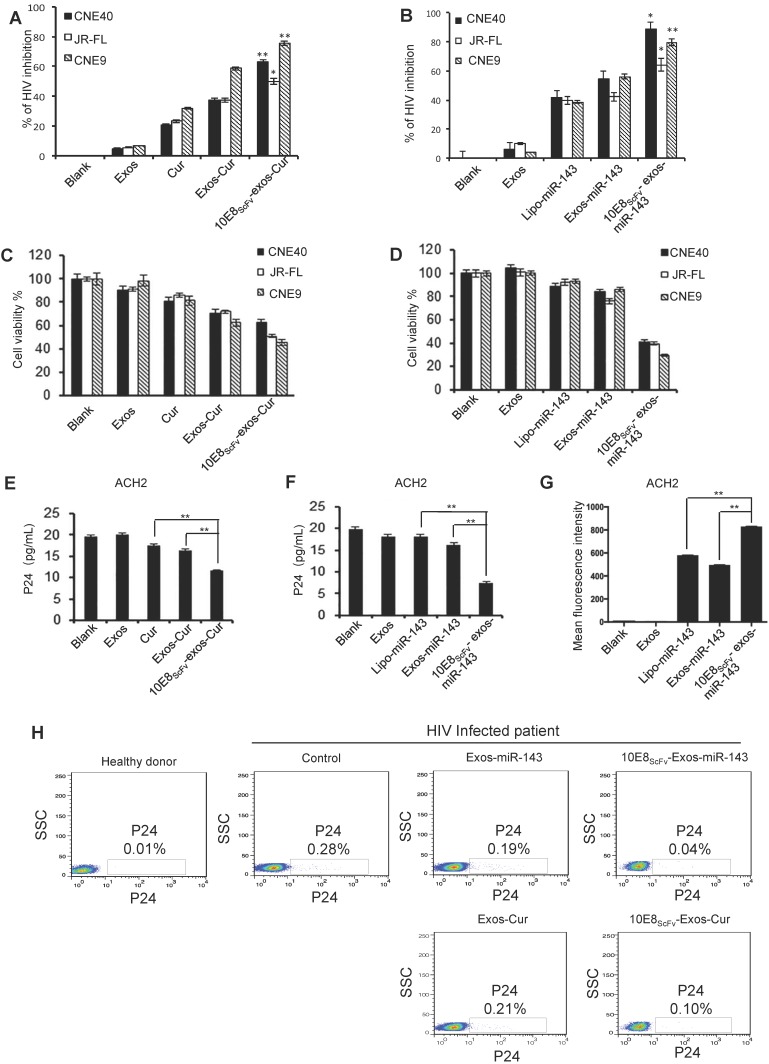

10E8scFv-exos-delivered Cur or miR-143 induced HIV-1-infected cell death

10E8scFv-exos-delivered Cur or miR-143 killing of HIV-1-infected cells was evaluated by treating ghost cells infected with HIV-1 env-pseudotyped virus with 10E8scFv-exos-Cur or -miR-143 and measuring luciferase activity as previously described 28.We showed that both Cur and miR-143 delivered by 10E8scFv-exos resulted in the suppression of HIV-1 infection (Figure 6A and B). The viability of HIV-1-infected cells after exosome treatment was determined by CCK-8, as shown in Figure 6C and 6D. Notably, 10E8scFv-exos-Cur resulted in 60%, 46%, and 70% death in cells infected with HIV-1CNE40 29, JR-FL 30 and CNE9 29, respectively, as compared to the mock-treated cells. In contrast, Exos-Cur only resulted in 30%, 30%, and 54% death in cells infected with CNE40, JR-FL, and CNE9, respectively (Figure 6C). Similarly, 10E8scFv-exos-miR-143 induced 60%, 61%, and 70% killing of CNE-40-, JR-FL-, and CNE-9-infected cells, as compared to 10%, 20%, and 9% killing of the respective cells treated with Exos-miR-143 (Figure 6D).

Figure 6.

Cur or miR-143 delivered by 10E8scFv-exos induced HIV-infected cell killing. (A, B)Ghost cells were infected with HIV-1 pseudo typed viruses. The infections were measured by a luciferase activity assay based on the luc gene integrated in the backbone of the engineered HIV-1 pseudotyped viruses. Relative luciferase activity (%) = ( Fluorescencesample - Fluorescencenon-infected ) / ( Fluorescencevirus control - Fluorescencenon-infected ). Fluorescencesample is from the HIV-1-infected ghost cells with experimental treatment; Fluorescencenon-infected is from the non-infected ghost cell control; and Fluorescencevirus control is from the ghost cells infected with HIV-1 without any treatment. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n = 3). Exos or 10E8scFv-exos were loaded with Cur (A). Exos or 10E8scFv-exos were loaded with miR-143 (B). (C, D) Cell death of HIV-1-infected host cells induced by the exosome cargo Cur or miR-143 were measured by cell viability. CCK-8 assays were used. Exos or 10E8scFv-exos were loaded with Cur (C). Exos or 10E8scFv-exos were loaded with miR-143 (D). (E, F) Suppression of HIV-1 in latency infected ACH2 cell model were tested by p24 released in the culture supernatant. Exos or 10E8scFv-exos were loaded with Cur (E). Exos or 10E8scFv-exos were loaded with miR-143 (F). (G) 10E8scFv-exos effectively targeted latency HIV-1-infected ACH2 cells. ACH2 cells were treated with exosomes or liposomes carrying miR-143-Cy5 and Cy5 fluorescence of the cells was tested. Mock and Exos without cargo were used as controls. (H) Killing of HIV-1-infected host cells were test in ex vivo PBMC directly from a chronic HIV-1-infected patient. P24-positive cells in the PBMC were determined by intracellular staining and flowcytometry. The PBMC without exosome treatment was used as control. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n =3).

In order to evaluate the ability of the engineered exosomes to kill latently infected cells and eradicate latent HIV reservoir, we utilized a widely used HIV-1 latently infected ACH2 cell line 18, 31. As previously described, ACH2 cells, activated to switch from latency to active replication 32, were treated with exosomes and viral replication was determined by p24 release. The cells treated with free Cur or Exos-Cur resulted in a baseline suppression of HIV-1, due to nonspecific adsorption of Cur 26. Notably, 10E8scFv-exos-Cur resulted in strong suppression of the viral replication as revealed by significant reduction of p24 level in the treated ACH2 cells, as shown in Figure 6E. Similarly, 10E8scFv-exos-miR-143 also significantly suppressed the virus level in the treated ACH2 cells compared with lipo-miR-143 or Exos-miR-143, as shown in Figure 6F. Moreover, ACH2 cells treated with exosomes loaded with Cy5 fluorescence-labeled miR-143 (miR-143-Cy5) confirmed that 10E8scFv-exos could specifically deliver miRNA to HIV-infected ACH2 more efficiently than exosomes or liposome vectors (Figure 6G).

We further tested 10E8scFv-exos-Cur or -miR-143 in PBMCs collected from an ART-treated chronic HIV-1-infected patient. Both 10E8scFv-exos-Cur and 10E8scFv-exos-miR-143 efficiently suppressed HIV-1 replication in the host cells as compared with Exos-Cur or Exos-miR-143, as shown in Figure 6H.

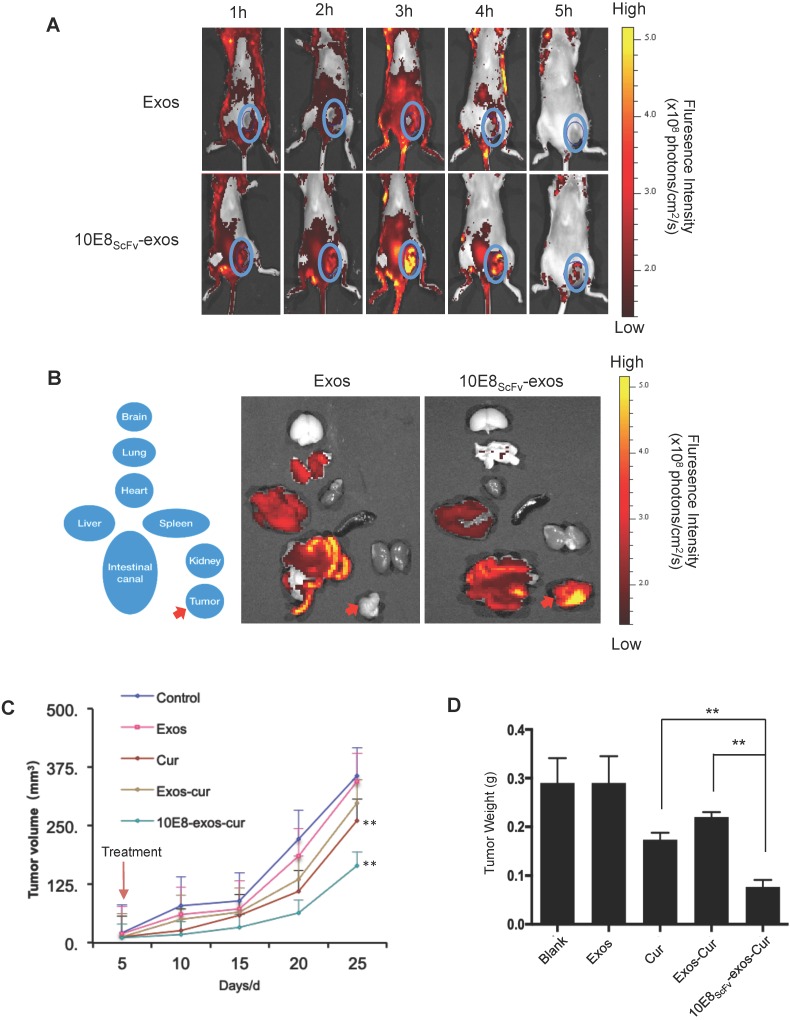

10E8scFv-Exos-Cur inhibited the growth of an Env+ tumor in vivo

In previous research, Env+ tumors were exploited to study the targeting and eradication of HIV-1 in solid tissue reservoirs, including the gut, lymphoid, and central nervous system tissues 33-36. In order to demonstrate Env-mediated targeting by 10E8scFv-exos in vivo, we induced solid tumors by inoculating 106 Env+ CHO cells into NCG mice, as previously described 37. Although Env+ CHO cells formed a tumor in NCG mice, 10E8scFv-exos could still efficiently target the Env+ cells and deliver cargo to them. In the present study, DiR dye-labeled 10E8scFv-exos or Exos was injected into NCG mice bearing ~0.2 cm3 tumors and the distribution of the injected exosomes was monitored in real time over 8 h using a MaestroTM in vivo optical imaging system. Exos rapidly disseminated to all major organs after injection (Figure 7A). The strongest fluorescence was detected in the liver after 2 h. At the earliest time point analyzed (1 h), a fluorescence signal from 10E8scFv-exos was detected at the tumor sites where it peaked approximately 3 h after injection (Figure 7A, lower panel). The signal then began to decline, remained detectable at 4 h, but only a minimal level of signal was detected at 5 h. In contrast, no specific fluorescence was observed at the tumor sites at any time point after Exos injection. A close examination revealed that in animals treated with Exos, the Exos appeared to be excluded from the site of the tumor (Figure 7A, upper panel).

Figure 7.

In vivo tumor targeting by 10E8scFv-exos. (A)Mice bearing Env+ tumors (~0.4 cm3) were given a single intravenous injection of DiR-labeled Exos or 10E8scFv-exos. In vivo fluorescence signals were recorded hourly for up to 5 h post-injection. Three hours after injection of 10E8scFv-exos, maximal fluorescence was detected at the tumor sites (blue boxes). No fluorescence changes were associated with the tumors of naked exos- treated mice at any time point. (B) Ex vivo fluorescence imaging of major organs from tumor-bearing mice 5 h after intravenous injection with DiR-labeled exos or 10E8scFv-exos are shown. Exos accumulated mainly in the liver, intestinal tract, heart, and lung, while, apart from small amounts in the liver and intestinal tract, 10E8scFv-exos was highly enriched in the tumor tissue. (C) In vivo anti-tumor activity of 10E8scFv-exos-Cur are shown by the tumor volumes. Mice bearing tumors (~0.1 cm3) were injected intravenously with different reagents, PBS (Control), Exos, Exos-Cur, 10E8scFv-exos-Cur or Cur (15 mg/kg) every five days for a total of 5 injections. (D) 10E8scFv-exos-Cur suppression of tumor growth as assayed on day 25 when the animals were sacrificed additionally. Statistical analyses were performed using a Mauchly's test of sphericity, *, p < 0.1 (n=5-6).

The distribution of the injected 10E8scFv-exos was thoroughly analyzed. 5 h after animals were injected with 10E8scFv-exos and ex vivo fluorescence imaging showed strong fluorescence signals in the tumor tissue, and relatively strong signals in the liver and intestinal tract (Figure 7B, right panel). In contrast, no specific fluorescence was detected in the tumor tissue from mice treated with Exos (Figure 7B, left panel), and the liver showed a similarly strong signal. These data are consistent with 10E8scFv-exos specifically delivering Cur to Env+ cells in vitro. We next assessed the effect of 10E8scFv-exos-Cur on tumor growth in the mouse model. Mice bearing ~0.1 cm3 Env+ tumors were randomly sorted into five groups and were treated as follows: (i) PBS, as a control; (ii) Exos; (iii) Exos-Cur; (iv) 10E8scFv-exos-Cur; and (v) an equivalent dose of free Cur. Mice were treated every five days for a total of 5 injections via the tail vein. Tumor volumes were measured by Vernier caliper every 5 days. The animals were sacrificed on day 25, tumors excised and weighted.

A significant suppression of tumor growth was observed in the animals treated with 10E8scFv-exos-Cur, as shown by the reduction of tumor volumes (Figure 7C) and weight (Figure 7D). Injection with 10E8scFv-exos-Cur induced tumor weight reduction by 71.26% as compared with the PBS-treated control (Table S1). Notably, the tumor volumes between the PBS- or the Cur-treated groups and 10E8scFv-exos-Cur treated groups indicated specific inhibition of tumors by 10E8scFv-exos-Cur. No morbidity or mortality occurred during the 25-day treatment with 10E8scFv-exos-Cur. The body weight of mice showed no differences among the animals treated with PBS or various exosomal preparations and the histology of major organs showed no toxicity with any of the exosomal preparations (Figure S6, S8, and S9). Our results suggest that 10E8scFv-exos-Cur is not generally toxic to the animals.

Discussion

Nano-carriers using various materials have been developed recently for polyethylene glycol-coated liposomes, which are frequently used as carriers for in vivo drug or miRNA delivery, benefiting from easy preparation, acceptable toxicity profiles and in vivo persistence 38. Liposomes, however, have several drawbacks, including low efficiency of targeting and accelerated blood clearance 39. Extracellular vesicles (EVs or exosomes) are enveloped subcellular nanostructures secreted by various cell types into the extracellular medium, and can carry a variety of cargo, including proteins and RNA. They also play a central role in cellular signaling and regulation 40, 41. On the other hand, exosomes are potential drug delivery carriers. In particular, engineering specific targeting molecules on the exosomal surface can facilitate their accumulation at desired sites of diseased tissues in vivo. Thus, the biocompatibility, low toxicity profiles, and possibly allogenic property of exosomes support their application in drug delivery 42.

The clearance of potential HIV reservoirs during highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) is key for treatment. It is widely accepted that latent HIV reservoirs could be stimulated to express viral proteins, such as envelop proteins, by various clinical means, providing a possibility to target the envelop in the HIV-1 reservoir 43. Therefore, we engineered our exosomes to express the scFv of high affinity 10E8 and assessed the efficiency and specificity of 10E8scFv-exos as bespoke, specific targeting vehicles to deliver cytotoxic molecules both in vitro and in vivo. Our results indicated 10E8scFv-exos could specifically target Env+ cells and tissues. In addition, systemic delivery was possible by conventional intravenous administration. Furthermore, exosomes carrying Cur or miR-143 induced the death of HIV-1-infected cells. We demonstrated that 10E8scFv-exos were effective in cargo-induced killing of HIV-1 Env+ cell lines, reactivated HIV-1 latently infected ACH2 cells, as well as PBMCs isolated from an HIV-1 patient receiving ART. Notably, the 10E8scFv-exos more efficiently suppressed HIV-1 replication in these difficult-to-transduce T cells. These results, taken together, provide proof of concept of engineering exosomes expressing scFv of an HIV-1-specific antibody as a targeted delivery system for the eradication of HIV-1 infection.

In the present study, we used Cur or miR-143 as a cargo in exosomes to treat Env+ target cells, including HIV-1 infected cells. Cur has been shown to inhibit HIV-1 RT 44, 45 and to down-modulate the CD4 receptor 46. On the other hand, miR-143 is a miRNA which induces cell apoptosis 47. Thus, we demonstrated the feasibility of loading exosomes with two distinct class of molecules and inducing killing of the target cells.

Current synthetic carrier systems, such as lipid nanoparticles or polymeric nanoparticles, often have undesirable intrinsic properties such as immune activation as foreign particles and potential toxicity. Exosomes, however, can potentially overcome these drawbacks. By histological analysis and measurement of serum biochemical markers after intravenous administration of 10E8scFv-exos-Cur, neither tissue damage nor other abnormalities were detected in the major organs. In the present study, we provided an example of using exosomes for the targeted delivery of the chemotherapeutic drug Cur to solid tumors expressing Env+ in mice. As previous study revealed, solid lymphoid tissues in gut, the nervous system, and lymph nodes are important reservoirs of HIV-1 in infected patients. Although HAART could effectively suppress HIV-1 in the periphery, interruption of ART often allows the quick rebound of virus from these tissue reservoirs 48, 49. Therefore, previous study used Env+ cell tumor as a model for the eradication the HIV-1 reservoir 37. In the current study, our results showed that 10E8scFv-exos could deliver drugs to the target tissue and inhibit growth of tumors, suggesting that exosomes as a delivery vehicle could penetrate solid tissues. In addition, histological analysis did not show overt toxicity in the major organs of the experimental animals. Therefore, our results indicated that engineered exosomes could be an effective delivery system to treat solid tissue reservoirs of HIV-1 infection.

Although HIV-1 envelop protein was used as the target molecule in the present study, other molecules, such as tumor markers, can be selected as targets depending on the purpose of the treatment and the availability of high affinity monoclonal antibodies. Considering the possibility that tumors could down-modulate expression of some cell-surface receptors for immune evasion, it is plausible to target receptors that are required for tumor growth, such as EGFR in breast cancer 50. Engineered exosomes may well serve as the next generation of RNA-based anti-HIV drug delivery tools. Their lipophilic nature may give them unique potential to deliver therapeutics to tissues for eradicating latent virus residing in solid tissues, such as lymphoid tissues. However, further research is needed to understand all the components that exosomes inherit from their parental cells and to improve the production of large amounts of well-characterized exosomal carriers with high loading capacity. Ongoing studies will attempt to address these questions.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by The Major Research and Development Project from the National Health Commission (Grant# 2018ZX10301406), the Key Project of Research and Development of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region of China (Grant# 2017BN04), the National Key Research and Development Program of China from the Ministry of Sciences and Technologies (Grant# 2016YFC1201000), and the 2018 Annual general project of Nanjing medical science and technology development fund (Grant# YKK18153).

Abbreviations

- 10E8scFv-exos

the scFv of a high affinity HIV-1-specific monoclonal antibody, 10E8, on exosomal surface

- ART

antiretroviral therapy

- CHO cells

Chinese hamster ovary cells

- Cur

curcumin

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immune sorbent assay

- Env+ cells

CHO cell expressing a trimeric gp140 on its surface

- EVs

Extracellular vesicles

- FACS

fluorescence-activated cell sorting

- HAART

highly active antiretroviral therapy

- HEK293T cells

human epithelial kidney 293T cells

- HIV-1

human immunodeficiency virus

- IgG

Immunoglobulin G

- MVBs

multivesicular bodies

- NCG mouse

NOD-Prkdcem26Cd52 Il2rgem26Cd22/NJU

- PBMCs

Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells

- scFv

single chain variable fragment

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures and tables.

References

- 1.Mathe G. The failure of HARRT to cure the HIV-1/AIDS complex. Suggestions to add integrase inhibitors as complementary virostatics, and to replace their continuous long combination applications by short sequences differing by drug rotations. Biomed Pharmacother. 2001;55:295–300. doi: 10.1016/s0753-3322(01)00074-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gebo KA, Fleishman JA, Conviser R, Hellinger J, Hellinger FJ, Josephs JS. et al. Contemporary costs of HIV healthcare in the HAART era. Aids. 2010;24:2705–15. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833f3c14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel AN, Atkinson D, Bartlett C, Silva F. Exosomes based therapy for the treatment of a mouse model of lung injury using extracellular vesicles derived from umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Mol Ther. 2018;26:71. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thery C, Zitvogel L, Amigorena S. Exosomes: composition, biogenesis and function. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:569–79. doi: 10.1038/nri855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thery C, Ostrowski M, Segura E. Membrane vesicles as conveyors of immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:581–93. doi: 10.1038/nri2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao K, Deng X, He C, Yue B, Wu M. Pseudomonas aeruginosa outer membrane vesicles modulate host immune responses by targeting the Toll-like receptor 4 signaling pathway. Infect Immun. 2013;81:4509–18. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01008-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 7.Arora UK, Dhir M, Cintron G, Strom JA. Successful multi-vessel percutaneous coronary intervention with bivalirudin in a patient with severe hemophilia A: a case report and review of literature. J Invasive Cardiol. 2004;16:330–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alvarez-Erviti L, Seow Y, Yin H, Betts C, Lakhal S, Wood MJ. Delivery of siRNA to the mouse brain by systemic injection of targeted exosomes. Nat biotechnol. 2011;29:341–5. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tian Y, Li S, Song J, Ji T, Zhu M, Anderson GJ. et al. A doxorubicin delivery platform using engineered natural membrane vesicle exosomes for targeted tumor therapy. Biomaterials. 2014;35:2383–90. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.11.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohno S-i, Takanashi M, Sudo K, Ueda S, Ishikawa A, Matsuyama N. et al. Systemically injected exosomes targeted to EGFR deliver antitumor microRNA to breast cancer cells. Mol Ther. 2013;21:185–91. doi: 10.1038/mt.2012.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun DM, Zhuang XY, Xiang XY, Liu YL, Zhang SY, Liu CR. et al. A novel nanoparticle drug delivery system: The anti-inflammatory activity of curcumin is enhanced when encapsulated in exosomes. Mol Ther. 2010;18:1606–14. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Longatti A, Schindler C, Collinson A, Jenkinson L, Matthews C, Fitzpatrick L. et al. High affinity single-chain variable fragments are specific and versatile targeting motifs for extracellular vesicles. Nanoscale. 2018;10:14230–44. doi: 10.1039/c8nr03970d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng Q, Shi X, Han M, Smbatyan G, Lenz HJ, Zhang Y. Reprogramming exosomes as nanoscale controllers of cellular immunity. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140:16413–7. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b10047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frey S, Marsh M, Gunther S, Pelchen-Matthews A, Stephens P, Ortlepp S. et al. Temperature dependence of cell-cell fusion induced by the envelope glycoprotein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1995;69:1462–72. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.3.1462-1472.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duzgunes N, Konopka K. Eradication of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 (HIV-1)-infected cells. Pharmaceutics. 2019;11:E255. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics11060255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia-Vidal E, Badia R, Pujantell M, Castellvi M, Felip E, Clotet B. et al. Dual effect of the broad spectrum kinase inhibitor midostaurin in acute and latent HIV-1 infection. Antiviral Res. 2019;168:18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2019.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kong D, Wang Y, Ji P, Li W, Ying T, Huang J. et al. A defucosylated bispecific multivalent molecule exhibits broad HIV-1-neutralizing activity and enhanced antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity against reactivated HIV-1 latently infected cells. Aids. 2018;32:1749–61. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Brien MC, Ueno T, Jahan N, Zajac-Kaye M, Mitsuya H. HIV-1 expression induced by anti-cancer agents in latently HIV-1-infected ACH2 cells. Biochem and biophys Res Commun. 1995;207:903–9. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prevost J, Richard J, Medjahed H, Alexander A, Jones J, Kappes JC. et al. Incomplete downregulation of CD4 expression affects HIV-1 Env conformation and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity responses. J Virol. 2018;92:e00484–18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00484-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Demangel C, Zhou J, Choo AB, Shoebridge G, Halliday GM, Britton WJ. Single chain antibody fragments for the selective targeting of antigens to dendritic cells. Mol Immunol. 2005;42:979–85. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang YS, Hong YS, Nam GH, Chung JH, Koh E, Kim IS. Virus-mimetic fusogenic exosomes for direct delivery of integral membrane proteins to target cell membranes. Adv Mater. 2017;29:201605604. doi: 10.1002/adma.201605604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thery C, Amigorena S, Raposo G, Clayton A. Isolation and characterization of exosomes from cell culture supernatants and biological fluids. Curr Protoc Cell Biol; 2006. Chapter 3: Unit 3 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoshimura K, Shibata J, Kimura T, Honda A, Maeda Y, Koito A. et al. Resistance profile of a neutralizing anti-HIV monoclonal antibody, KD-247, that shows favourable synergism with anti-CCR5 inhibitors. Aids. 2006;20:2065–73. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000247587.31320.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fu Y, Zhang L, Zhang F, Tang T, Zhou Q, Feng C. et al. Exosome-mediated miR-146a transfer suppresses type I interferon response and facilitates EV71 infection. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13:e1006611. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen D, Feng C, Tian X, Zheng N, Wu Z. Promyelocytic leukemia restricts enterovirus 71 replication by inhibiting autophagy. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1268. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.da Silva TAL, Medeiros RMV, de Medeiros DC, Medeiros R, de Medeiros JA, de Medeiros G. et al. Impact of curcumin on energy metabolism in HIV infection: A case study. Phytother Res. 2019;33:856–8. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liang B, Song Y, Zheng W, Ma W. miRNA143 induces K562 cell apoptosis through downregulating BCR-ABL. Med Sci Monit. 2016;22:2761–7. doi: 10.12659/MSM.895833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fenyo EM, Heath A, Dispinseri S, Holmes H, Lusso P, Zolla-Pazner S. et al. International network for comparison of HIV neutralization assays: the NeutNet report. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4505. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shang H, Han X, Shi X, Zuo T, Goldin M, Chen D. et al. Genetic and neutralization sensitivity of diverse HIV-1 env clones from chronically infected patients in China. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:14531–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.224527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Merrill JE, Koyanagi Y, Zack J, Thomas L, Martin F, Chen IS. Induction of interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor alpha in brain cultures by human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1992;66:2217–25. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.4.2217-2225.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Folks TM, Clouse KA, Justement J, Rabson A, Duh E, Kehrl JH. et al. Tumor necrosis factor alpha induces expression of human immunodeficiency virus in a chronically infected T-cell clone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:2365–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.7.2365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clouse KA, Powell D, Washington I, Poli G, Strebel K, Farrar W. et al. Monokine regulation of human immunodeficiency virus-1 expression in a chronically infected human T cell clone. J Immunol. 1989;142:431–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanchez-Taltavull D, Vieiro A, Alarcon T. Stochastic modelling of the eradication of the HIV-1 infection by stimulation of latently infected cells in patients under highly active anti-retroviral therapy. J Math Biol. 2016;73:919–46. doi: 10.1007/s00285-016-0977-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moron-Lopez S, Puertas MC, Galvez C, Navarro J, Carrasco A, Esteve M. et al. Sensitive quantification of the HIV-1 reservoir in gut-associated lymphoid tissue. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0175899. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lambotte O, Deiva K, Tardieu M. HIV-1 persistence, viral reservoir, and the central nervous system in the HAART era. Brain Pathol. 2003;13:95–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2003.tb00010.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Marle G, Gill MJ, Kolodka D, McManus L, Grant T, Church DL. Compartmentalization of the gut viral reservoir in HIV-1 infected patients. Retrovirology. 2007;4:87. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-4-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Song E, Zhu P, Lee SK, Chowdhury D, Kussman S, Dykxhoorn DM. et al. Antibody mediated in vivo delivery of small interfering RNAs via cell-surface receptors. Nat biotechnol. 2005;23:709–17. doi: 10.1038/nbt1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liao W, Du Y, Zhang C, Pan F, Yao Y, Zhang T. et al. Exosomes: The next generation of endogenous nanomaterials for advanced drug delivery and therapy. Acta biomater. 2019;86:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2018.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gomari H, Forouzandeh Moghadam M, Soleimani M. Targeted cancer therapy using engineered exosome as a natural drug delivery vehicle. Onco Targets Ther. 2018;11:5753–62. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S173110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Golchin A, Hosseinzadeh S, Ardeshirylajimi A. The exosomes released from different cell types and their effects in wound healing. J cell biochem. 2018;119:5043–52. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li LM, Liu ZX, Cheng QY. Exosome plays an important role in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Pathol Res Pract; 2019. p. 152468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Familtseva A, Jeremic N, Tyagi SC. Exosomes: cell-created drug delivery systems. Mol and cell biochem; 2019. s11010-019-03545-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Archin NM, Liberty AL, Kashuba AD, Choudhary SK, Kuruc JD, Crooks AM. et al. Administration of vorinostat disrupts HIV-1 latency in patients on antiretroviral therapy. Nature. 2012;487:482–5. doi: 10.1038/nature11286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cancio R, Silvestri R, Ragno R, Artico M, De Martino G, La Regina G. et al. High potency of indolyl aryl sulfone nonnucleoside inhibitors towards drug-resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase mutants is due to selective targeting of different mechanistic forms of the enzyme. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:4546–54. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.11.4546-4554.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ali A, Banerjea AC. Curcumin inhibits HIV-1 by promoting Tat protein degradation. Sci Rep. 2016;6:27539. doi: 10.1038/srep27539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vermeire K, Bell TW, Choi HJ, Jin Q, Samala MF, Sodoma A. et al. The Anti-HIV potency of cyclotriazadisulfonamide analogs is directly correlated with their ability to down-modulate the CD4 receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:203–10. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.1.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao K, Zhang Y, Kang L, Song Y, Wang K, Li S. et al. Epigenetic silencing of miRNA-143 regulates apoptosis by targeting BCL2 in human intervertebral disc degeneration. Gene. 2017;628:259–66. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2017.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Colby DJ, Trautmann L, Pinyakorn S, Leyre L, Pagliuzza A, Kroon E. et al. Rapid HIV RNA rebound after antiretroviral treatment interruption in persons durably suppressed in Fiebig I acute HIV infection. Nat Med. 2018;24:923–6. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0026-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Palmer A, Gabler K, Rachlis B, Ding E, Chia J, Bacani N. et al. Viral suppression and viral rebound among young adults living with HIV in Canada. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e10562. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu C, Liu F, Xiang G, Cao L, Wang S, Liu J. et al. beta-Catenin nuclear localization positively feeds back on EGF/EGFR-attenuated AJAP1 expression in breast cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2019;38:238. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1252-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figures and tables.