Abstract

This cohort study examines whether PBRM1 alterations are associated with response to immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment in patients with metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma.

Nivolumab, an immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) targeting the programmed death-1 (PD-1) pathway, is approved for metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC).1 Loss-of-function (truncating) mutations in PBRM1, a PBAF-complex gene commonly mutated in ccRCC, were previously associated with clinical benefit from anti–PD-1 therapy in a smaller study,2 Herein, this association was examined in an independent cohort from a randomized clinical trial1 to determine whether PBRM1 alterations are a marker of response to ICI treatment.

Methods

Archival tumor tissue (collected before antiangiogenic therapy) was obtained from patients enrolled in a randomized, phase 3 trial that demonstrated improved overall survival (OS) with nivolumab vs everolimus in patients with ccRCC who received prior antiangiogenic therapy.1 This study was conducted under a secondary use protocol, approved by the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. Written informed consent was obtained from participants. This post hoc analysis included 382 of 803 patients who were consented for genomic studies and passed quality control.2 This cohort was not significantly different from the other 421 patients in response or progression-free survival (PFS). Putative truncating mutations (frameshift insertion/deletion, nonsense, splice-site)2 in PBRM1 were manually reviewed using the Integrative Genomics Viewer.3

Clinical response (complete/partial remission by response evaluation criteria in solid tumours [RECIST]), clinical benefit (complementary to RECIST, defined previously as complete/partial response, or stable disease with tumor shrinkage and PFS ≥6 months)2 and survival data were available for all 382 patients. The proportions of patients with truncating PBRM1 mutations in responding (complete/partial response) vs nonresponding (progressive disease) patients, and clinical benefit vs no clinical benefit (progressive disease, PFS ≤3 months),2 were compared using Fisher exact test (1-sided, given prior association of PBRM1 mutations with clinical benefit2; R statistical software; v3.5.2; R Foundation). Other clinical characteristics were compared by χ2 testing. Participant PFS and OS were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, association with PBRM1 truncating mutations assessed using the log-rank test, and hazard ratio (HR) calculated using a Cox proportional hazard model (2-sided; R statistical software; survival/survminer packages v3.5.2; R Foundation).

Results

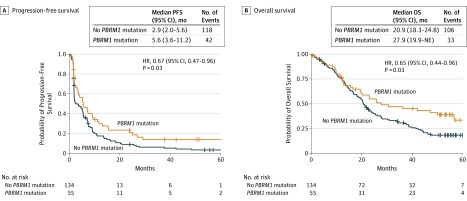

PBRM1 mutations were identified in 55 of 189 nivolumab-treated (29%) and of 45 of 193 everolimus-treated (23%) patients (Table). Among nivolumab-treated patients, 15 of 38 responding (39%) and 16 of 74 nonresponding (22%) patients had truncating PBRM1 mutations (odds ratio [OR], 2.34; 95% CI, 1.05-∞; P = .04). PBRM1 mutations were also associated with clinical benefit2 (18/52 with clinical benefit, 14/71 with no clinical benefit; OR, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.00-∞; P = .0497). PBRM1 mutation was associated with increased PFS (HR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.47-0.96; P = .03) and OS (HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.44-0.96; P = .03) (Figure). Among patients treated with everolimus, 1 of 5 responding (20%) and 10 of 56 nonresponding (17.9%) patients had truncating PBRM1 mutations (OR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.04-∞; P = .64). There was no evidence of an association between PBRM1 mutation and PFS (HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.58-1.2; P = .32) or OS (HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.56-1.18; P = .27) in patients treated with everolimus.

Table. Demographic, Clinical Characteristics, and Tumor Response in the PBRM1 Truncating Mutant and Wild-Type Groups in the Nivolumab and Everolimus Treatment Groupsa.

| Parameter | Nivolumab (N = 189) | Everolimus (N = 193) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBRM1 | P Value | PBRM1 | P Value | |||

| Mutant (N = 55) | Wild-Type (N = 134) | Mutant (N = 45) | Wild-Type (N = 148) | |||

| Age, y, No. (%) | ||||||

| ≤65 | 37 (67) | 89 (66) | >.99 | 29 (64) | 103 (70) | .69 |

| >65 | 17 (31) | 40 (30) | 15 (33) | 43 (29) | ||

| NA | 1 (2) | 5 (4) | 1 (2) | 2 (1) | ||

| Sex, No. (%) | ||||||

| Male | 42 (76) | 97 (72) | .70 | 31 (69) | 105 (71) | .94 |

| Female | 13 (24) | 37 (28) | 14 (31) | 43 (29) | ||

| Performance status, KPS, No. (%)b | ||||||

| Range | <70-100 | 70-100 | >.99 | 70-100 | <70-100 | .89 |

| ≤80 | 18 (33) | 43 (32) | 18 (40) | 63 (43) | ||

| >80 | 37 (67) | 91 (68) | 27 (60) | 85 (57) | ||

| IMDC risk group | ||||||

| Favorable | 7 (13) | 19 (14) | .84 | 7 (16) | 26 (18) | .42 |

| Intermediate/poor | 46 (84) | 112 (84) | 38 (84) | 117 (79) | ||

| Not reported | 2 (3.6) | 3 (2) | 0 | 5 (3) | ||

| Objective response, No. (%) | ||||||

| CR/PR | 15 (27) | 23 (17) | .04c | 1 (2) | 4 (3) | .64c |

| SD | 19 (35) | 42 (31) | 29 (64) | 77 (52) | ||

| PD | 16 (29) | 58 (43) | 10 (22) | 46 (31) | ||

| NE | 5 (9) | 11 (8) | 5 (11) | 21 (14) | ||

| Clinical benefit, No. (%) | ||||||

| CB | 18 (33) | 34 (25) | .0497d | 13 (29) | 35 (24) | .21d |

| ICB | 18 (33) | 32 (24) | 17 (38) | 48 (32) | ||

| NCB | 14 (25) | 57 (43) | 10 (22) | 44 (30) | ||

| NE | 5 (9) | 11 (8) | 5 (11) | 21 (14) | ||

Abbreviations: CB, clinical benefit; CR/PR, complete response/partial response; ICB, intermediate clinical benefit; IMDC, International Metastatic RCC Database Consortium; KPS, Karnofsky performance status; NA, not available; NCB, no clinical benefit; NE, not evaluable; PD, progressive disease; SD, stable disease.

Some percentages may not add up to 100 owing to rounding.

KPS greater than 80 includes patients with no symptoms or only minor symptoms of disease.

Comparison of proportion of PBRM1 truncating mutants in CR/PR vs PD group, Fisher exact test (1-sided). Using a comparison of CR/PR for response vs SD/PD/NE for nonresponse, there was not a significant association of mutation with response rate for the nivolumab group (P = .09) or the everolimus group (P = .73).

Comparison of proportion of PBRM1 truncating mutations in CB vs NCB group, Fisher exact test (1-sided).

Figure. Progression-Free and Overall Survival Following Treatment With Nivolumab, With or Without PBRM1 Truncating Mutations.

A, Progression-free survival (PFS) with and without a PBRM1 mutation in patients treated with nivolumab. B, Overall survival (OS) with and without a PBRM1 mutation in patients treated with nivolumab. NE Indicates not estimable.

Discussion

The association of PBRM1 truncating mutations with response to anti–PD-1 therapy was confirmed in an independent ccRCC cohort. However, key limitations restrict use of PBRM1 mutations as a clinical biomarker. First, the PBRM1 mutation effect on response and survival was modest. Second, the effect was observed in patients who received prior antiangiogenic therapy, whereas associated studies of PBRM1 mutations in the first-line setting had negative results.2,4 Third, PBRM1 alterations may also be associated with benefit from antiangiogenic therapies.4 Moreover, there are inherent limitations to the current study, including use of archival tissue, lack of data regarding time on initial antiangiogenic therapy, and inclusion of only clear cell histology. The concomitant presence of other cellular or molecular features may further influence the findings described herein. Nonetheless, this validated association between PBRM1 alterations and ICI response in a large randomized study represents a further step toward the development of genomic predictors for immunotherapies in advanced RCC.

References

- 1.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, McDermott DF, et al. ; CheckMate 025 Investigators . Nivolumab versus Everolimus in Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(19):1803-1813. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miao D, Margolis CA, Gao W, et al. . Genomic correlates of response to immune checkpoint therapies in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Science. 2018;359(6377):801-806. doi: 10.1126/science.aan5951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thorvaldsdóttir H, Robinson JT, Mesirov JP. Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV): high-performance genomics data visualization and exploration. Brief Bioinform. 2013;14(2):178-192. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbs017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDermott DF, Huseni MA, Atkins MB, et al. . Clinical activity and molecular correlates of response to atezolizumab alone or in combination with bevacizumab versus sunitinib in renal cell carcinoma. Nat Med. 2018;24(6):749-757. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0053-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]