Abstract

Objective:

Behçet’s disease (BD), a multisystemic inflammatory disorder, has been associated with a number of cardiovascular dysfunctions, including ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. The mechanism of increased ventricular arrhythmias in BD remains uncertain. The aim of the present study was to assess the ventricular repolarization by using the Tp–e interval, Tp–e/QT ratio, and Tp–e/QTc ratio as candidate markers of ventricular arrhythmias in patients with BD.

Methods:

A total of 42 patients (mean age: 42.71±10.99 years) with BD and 50 sex- and age-matched healthy volunteers (mean age: 39.24±11.32 years) as the control group were evaluated. The risk of ventricular arrhythmia was evaluated by calculating the electrocardiographic, the Tp–e interval, and the QT, QTc, Tp–e/QT, and Tp–e/QTc ratios.

Results:

QTmax (p=0.005), QTcmax (p=0.015), QTmin (p=0.011), and QTcmin (p=0.024) were statistically significantly higher in the BD group than in the control group. The Tp–e, cTp–e, Tp–e/QT, and Tp–e/QTc ratios were also significantly higher in patients with BD than in the control group (80.26±4.55 and 74.74±6.47, respectively, p<0.001; 88.23±6.36 and 82.68±7.81, respectively, p<0.001; 0.21±0.01 and 0.20±0.01, respectively, p=0.008; and 0.19±0.01 and 0.18±0.01, respectively, p=0.01). Positive correlations were found between Tp–e/QTc ratio and disease duration (r=0.382, p=0.013).

Conclusion:

Our study showed that the Tp–e interval, Tp–e/QT ratio, and Tp–e/QTc ratio, which are evaluated electrocardiographically in patients with BD, have been prolonged compared with normal healthy individuals. A positive correlation was determined between disease duration and Tp–e/QTc ratio. These results may be indicative of an early subclinical cardiac involvement in patients with BD, considering the duration of the disease. Therefore, these patients should be more closely screened for ventricular arrhythmias.

Keywords: Behçet’s disease, Tp–e interval, Tp–e/QTd ratio, ventricular arrhythmia

Introduction

Hulusi Behçet, a Turkish doctor, described Behçet’s disease (BD) in 1937 as a triad of recurrent aphthous ulcers in the mouth, genital ulcer, and recurrent uveitis episodes (1). This disease can be seen as the involvement of the mucocutaneous, eye, gastrointestinal, respiratory, neurological, urogenital, joint, and cardiovascular systems (2). Heart involvement is rarely known as “Cardio-Behçet’s disease,” and the mortality rate in the literature is reported between 7% and 46% (3, 4). Cardiovascular involvement of BD consists of pericarditis, myocarditis, endocarditis, dilated cardiomyopathy, right-sided endomyocardial fibrosis, disturbances of the conduction system, atrial fibrillation, life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias, and sudden cardiac death (5, 6). Previous studies have shown that ventricular arrhythmias in patients with BD are more frequent than those in healthy controls (7, 8). However, the mechanism of increased ventricular arrhythmias in BD remains uncertain.

Myocardial repolarization can be assessed with QT interval (QT), corrected QT interval (QTc), QT dispersion (QTd), and transmural dispersion of repolarization (TDR) (9, 10). Tp–e interval, which is the interval between the peak and the end of the T wave on an electrocardiogram (ECG), is accepted as an index of TDR (10). However, in many studies in the literature, Tp–e/QT and Tp–e/QTc ratios were used as a new electrocardiography index for ventricular arrhythmogenesis (11, 12). Previous studies have examined the frequency of qrs fragmentation and QTd in predictors of ventricular arrhythmias in patients with BD (13, 14). However, the Tp–e interval, Tp–e/QT ratio, and Tp–e/QTc ratio, novel repolarization indexes, have not been studied in these patients. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the myocardial repolarization in patients with BD using the Tp–e interval, QT and QTc, Tp–e/QT ratio, Tp–e dispersion, and Tp–e/QTc ratio.

Methods

Study design

This was as an observational, cross-sectional study.

Study population

A total of 42 patients who met our study criterion who were diagnosed with BD according to the International Study Group for BD diagnostic criteria were recruited from our patients’ pool (15). A total of 50 sex- and age-matched healthy volunteers were randomly selected for the control group. The Local Ethics Committee approved the study protocol. Informed written consent was obtained from each patient.

Patients with the following conditions were excluded from the study: coronary artery disease and/or previous myocardial infarction, left ventricular (LV) dysfunction, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, moderate-to-severe valve disease, hepatic and renal failures, chronic lung disease, thyroid dysfunction, atrial fibrillation, history of dysrhythmia, history of pacemaker or cardioverter defibrillator implantation, bundle branch block, evidence of any other intraventricular conduction defect, bradycardia (<60 beats/min), tachycardia (>100 beats/min), electrolyte abnormalities, and poor-quality imaging on two-dimensional echocardiography. All the patients were in sinus rhythm, and none of the participants were taking antiarrhythmic drugs, beta-blockers, non-dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers, tricyclic antidepressants, antihistamines, or antipsychotics for at least 6 months before the study.

Weight and height measurements were performed, and body mass index (BMI) was calculated as the ratio of weight to height squared (kg/m2). Blood pressure was measured consecutively three times, 15 min apart in the sitting position, and the mean value was used. The disease duration was estimated by considering the day of the initial examination, in which the patient fulfilled all the International Study Group criteria, to be the onset. Samples for complete blood count (CBC) analysis were collected in EDTA-anticoagulated tubes (VacuSEL, Turkey). Blood samples were analyzed using Sysmex XN 1000 automated hematology analyzer (Sysmex Corporation, Kobe, Japan) for CBC. In addition, the serum C-reactive protein (CRP) was measured by chemiluminescence microparticle immunoassay (ci 4100 ARCHITECT, USA).

Electrocardiographic and echocardiographic assessments

All echocardiographic examinations were performed by the affinity 50 ultrasound imaging system with S4-2 transducer (Philips, Bothell, WA, USA). In the left lateral decubitus position, parasternal long and short axes, apical 4 and 2 chamber images were obtained. Left atrial, LV end-systolic, and LV end-diastolic diameters were obtained from 2D images. The ejection fraction was calculated using Simpson’s biplane method. The apical four-chamber view was acquired by PW Doppler method with the sample volume positioned at the tip of the mitral valve leaflets that allowed to calculate the maximum velocities of early diastolic peak transmitral flow velocity (E) and late diastolic peak transmitral flow velocity (A) in cm/s. The E/A ratio was calculated. E wave deceleration time is calculated in milliseconds (ms). Again, mitral lateral annulus peak early diastolic (Em), peak late diastolic, and systolic wave velocities were measured in cm/s by tissue Doppler in apical four-chamber sections. Thereafter, the same tissue was measured as myocardial isovolumetric relaxation time (IVRT), isovolumetric contraction time, and ejection time (ms) in the Doppler image. E/Em ratio was also calculated.

ECG recorder (Nihon Kohden, Tokyo, Japan) set at 50 mm/s paper speed and 10 mm/mV voltage was used. The maximum and minimum QT and Tp–e intervals were performed by two cardiologists who were blinded to the patient data. QT and Tp–e intervals were measured manually with calipers and magnifying glass to reduce the error rate. Subjects with U waves on their ECGs were excluded from the study. The QT interval was measured from the beginning of the QRS complex to the end of the T wave and corrected for heart rate using the Bazett formula: QTc=QT√ (R–R interval). Maximum (QTmax) and minimum (QTmin) QT-wave durations were defined as the longest and shortest measurable QT-wave durations, respectively, in any lead. Accordingly, corrected QT dispersion (QTcd) was calculated as the difference between maximal and minimal QTc intervals. Tp–e interval was defined as the interval between the peak and the end of T wave. Measurements of Tp–e interval were performed from precordial leads (16). The Tp–e/QT and Tp–e/QTc ratios were calculated from these measurements.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 20.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables were presented as mean±standard deviation, and categorical variables were expressed as number and percentage. Continuous variables were compared between the groups using the Student’s t-test according to whether normally distributed, as tested by the Shapiro–Wilk test. The Chi-square test was used to assess the differences between categorical variables according to their distribution. Pearson’s or Spearman’s correlation coefficient tests were used to assess the strength of the relationship between Tp–e/QTc ratios and BD duration. Bland–Altman plots were used to determine the limits of agreement, and 95% confidence interval about the mean difference both within and between observers was constructed to test for bias between assessors. A p value <0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

Results

Clinical characteristics and echocardiographic findings of patients with BD and control subjects are shown in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences between the groups with respect to age, sex, BMI, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, LV end-diastolic dimension, thickness of the interventricular septum, left atrium dimension, and LV ejection fraction (p>0.05). There was also no difference between the two groups with respect to plasma level of CRP and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (p>0.05). There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups with respect to diastolic parameters (E, E/A IVRT, Sseptal, and E/Em) (p>0.05). The mean disease duration was 14.27±8.5 years.

Table 1.

Demographic, biochemical, and echocardiographic characteristics of the controls and patients with Behçet’s disease

| Behçet’s disease (n=42) | Controls (n=50) | P values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 42.71±10.99 | 39.24±11.32 | 0.141 |

| Sex (Male/Female) | 23/19 | 28/22 | 0,907 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.62±5.55 | 26.37±3.67 | 0.199 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 117.38±12.55 | 113.90±8.70 | 0.121 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 72.69±9.53 | 71.60±7.85 | 0.549 |

| Disease duration (years) | 14.27±8.5 | --- | --- |

| Glukoz (mg/dL) | 97.74±13.35 | 95.58±11.72 | 0.411 |

| Kreatinin (mg/dL) | 0.83±0.132 | 0.83±0.134 | 0.978 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 159.9±82.58 | 143±61.57 | 0.264 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 45.97±10.36 | 49.56±10.49 | 0.104 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 108.91±26.79 | 112.76±31.95 | 0.538 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 14.21±1.37 | 14.62±1.62 | 0.202 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 6.75±11.49 | 4.23±8.92 | 0.239 |

| Sedimentasyon (mm/h) | 13.20±6.83 | 12.82±8.95 | 0.821 |

| Medications n (%) | |||

| Colchicine | 24 (57) % | --- | --- |

| NSAI drugs | 2 (4.7) % | --- | --- |

| Corticosteroids | 5 (11.9) % | --- | --- |

| Azathioprine | 4 (9.5) % | --- | --- |

| Cyclosporine | 3 (7.1) % | --- | --- |

| Echocardiography (2D) | |||

| LVEF (%) | 61.31±2.94 | 62.04±2.76 | 0.223 |

| LVEDD (mm) | 46.74±3.63 | 46.52±2.89 | 0.749 |

| IVS (mm) | 0.95±0.11 | 0.94±0.78 | 0.769 |

| Left atrial diameter (mm) | 3.44±0.38 | 3.40±0.28 | 0.497 |

| E | 78.7±14.9 | 83.4±12.14 | 0.103 |

| E/A | 1.16±0.29 | 1.24±0.21 | 0.108 |

| IVRT | 76.43±11.4 | 72.6±11.4 | 0.112 |

| Sseptal (cm/sn) | 7.89±1.02 | 7.96±1.08 | 0.747 |

| E/Em | 6.16±1.07 | 5.84±1.14 | 0.166 |

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation.

SBP - systolic blood pressure; DBP - diastolic blood pressure; HDL - high-density lipoprotein; LDL - low-density lipoprotein; CRP - C-reactive protein; LVEF - left ventricular ejection fraction; LVEDD - left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; IVS - interventricular septum; NSAI - nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory

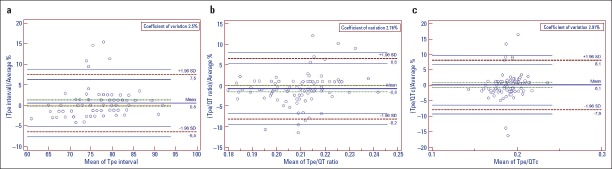

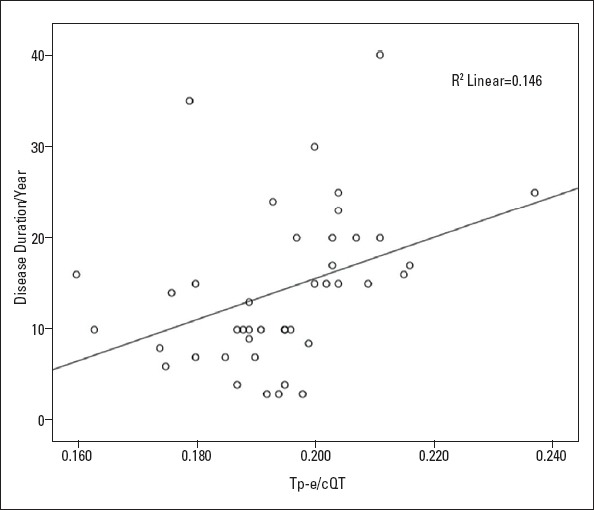

The electrocardiographic parameters of the groups are shown in Table 2. The QTmax (p=0.005), QTcmax (p=0.015), QTmin (p=0.011), and QTcmin (p=0.024) were statistically significantly higher in the BD group than in the control group. The Tp–e, cTp–e, Tp–e/QT, and Tp–e/QTc ratios were also significantly higher in patients with BD than in the control group (80.26±4.55 and 74.74±6.47, respectively, p<0.001; 88.23±6.36 and 82.68±7.81, respectively, p<0.001; 0.21±0.01 and 0.20±0.01, respectively, p=0.008; and 0.19±0.01 and 0.18±0.01, respectively, p=0.01, Table 2). The Bland–Altman plot showed the mean bias±SD for intraobserver Tpe interval measurements as 0.501±3.555 (limits of agreement were −6.467 and 7.468) (Fig. 1a), for intraobserver Tpe/QT ratio measurements as −0.833±3.771 (limits of agreement were −8.225 and 6.559) (Fig. 1b), and for intraobserver Tpe/QTc ratio measurements as 0.064±4.086 (limits of agreement were −7.945 and 8.0723) (Fig. 1c). In addition, we found that QTd and QTcd values increased in patients with BD, but this increase was not statistically significant. Positive correlations were found between Tp–e/QTc ratio and disease duration (r=0.382, p=0.013) (Fig. 2). No significant correlation was found between QT parameters (QT dispersion, QTcmax, and QTcmin) and disease duration.

Table 2.

Electrocardiographic findings of the two groups

| Behçet’s disease (n=42) | Controls (n=50) | P values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| QTmax (ms) | 389.02±17.44 | 375.20±26.57 | 0.005 |

| cQTmax (ms) | 427.35±20.65 | 414.6±27.14 | 0.015 |

| QTmin (ms) | 361.90±18.24 | 350.92±21.77 | 0.011 |

| cQTmin (ms) | 397.88±20.14 | 387.56±22.46 | 0.024 |

| QTd (ms) | 27.11±10.39 | 24.28±13.07 | 0.259 |

| cQTd (ms) | 29.86±11.77 | 26.77±14.27 | 0.268 |

| Tp-e (ms) | 80.26±4.55 | 74.74±6.47 | <0.001 |

| cTp-e (ms) | 88.23±6.36 | 82.68±7.81 | <0.001 |

| Tp-e/QT | 0.21±0.01 | 0.20±0.01 | 0.008 |

| Tp-e/cQT | 0.19±0.01 | 0.18±0.01 | 0.010 |

| Tp-e dispertion | 21.2±4.3 | 14.2±3.4 | <0.001 |

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation QTmax - QTmaximum; QTcmax - corrected QT maximum; QTmin - QT minimum; QTcmin - corrected QT minimum; QTd - QT dispersion; QTcd - corrected QT dispersion; Tp–e - transmural dispersion of repolarization; cTp–e - corrected transmural dispersion of repolarization; Tp–e/QT - transmural dispersion of repolarization/QT; Tp–e/QTc - transmural dispersion of repolarization/corrected QT

Figure 1.

The Bland–Altman plot figure

Figure 2.

Correlations between Tpe–QTc ratio and disease duration

Discussion

We found that the Tp–e, cTp–e, Tp–e/QT, and Tp–e/QTc ratios were longer in patients with BD than in healthy subjects. However, there was a statistically significant positive correlation between disease duration and Tp–e/QTc.

Although cardiac involvement is not common in BD, complications, such as complex ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death, have been reported (13). In the literature, it has been shown that the incidence of ventricular arrhythmia is higher in patients with BD than in normal healthy individuals, but the pathophysiology of this increase has not been fully clarified. Tp–e interval is defined as the total dispersion index of ventricular repolarization (10, 11). The relationship between prolonged Tp–e interval and ventricular arrhythmias and mortality was shown (17, 18). Since Tp–e interval is affected by heart rate variability and body surface area, Tp–e/QTc index is considered to be more meaningful as ventricular repolarization index because it is not affected by these variables (19, 20). We believe that increased Tp–e, Tp–e/QT, Tp–e/QTc, and Tp–e dispersion ratios in patients with BD increase ventricular repolarization heterogeneity and ventricular arrhythmias and may help to clarify the pathophysiological mechanisms in these patients.

In previous studies, increased mortality was observed in patients with both Brugada syndrome and long QT syndrome if they had longer Tp–e intervals (19). BD is a systemic disease that may affect the cardiovascular coronary microcirculation of the pathophysiological changes in the system (14). It is known that the disease is a vasculitis affecting arteries and arterioles, and it causes focal fibrinoid and fibroelastic proliferation in the vessel lumen over time (21). Myocardial ischemia and functional abnormalities and the resulting myocardial fibrosis can stem from vasculitis of the small arteries and arterioles in the coronary vascular bed and impairment of the microcirculation (22). Myocardial fibrosis may prolong these parameters. Ventricular repolarization was previously evaluated using QTd measurements in BD, and these studies have shown that QTd increases in patients with BD (7, 13). Tp–e dispersion, Tp–e/QT ratio, and Tp–e/QTc have been proposed to be better markers of ventricular repolarization than QT parameters (5, 23). In our study, we found that QTd increased, but this increase was not statistically significant in patients with BD. This may be due to the small number of patients and may also be because the QTd deteriorates later than the other ventricular repolarization parameters. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the new parameters of Tp–e interval, Tp–e/QT ratio, and Tp–e/QTc in patients with BD. Therefore, to clarify this issue, larger randomized studies are needed.

Prolongation of Tp–e interval, Tp–e/QT, and Tp–e/QTc duration may be a cause of ventricular arrhythmias in patients with BD. In our study, there was a positive correlation between the duration of the disease and Tp–e/QTc. As in many other chronic diseases, the date of the first diagnosis was taken as the onset of BD in our study. For this reason, it is thought that it will be more beneficial to detect and prevent arrhythmic events that may develop in patients who have long-term BD. We think that our study may be a first on this topic. Many studies are needed to support our findings.

Study limitations

Our study has several limitations. The main limitation of our study was that the cross-sectional design of the study limited the follow-up with respect to ventricular arrhythmias. Long-term Holter recording would be useful to evaluate the incidence of ventricular arrhythmias in these patients. For standardization, to determine the duration of the disease, we based the date of diagnosis at the hospital. This is a limitation of the study and is also an inevitable condition in similar chronic diseases. To show correlations between these parameters and arrhythmic events in this population, large prospective studies are needed.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the myocardial repolarization using the Tp–e interval and Tp–e/QT ratio in patients with BD. We think that it would be useful to follow-up the electrocardiographic parameters of patients who were followed up for BD. Large-scale long-term studies are needed to support our data.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Authorship contributions: Concept – Ş.H., V.D., M.H.T.; Design – Ş.H., V.D., Y.T., G.G.; Supervision – Ş.H., Y.T., M.H.T.; Fundings – Ş.H., Y.T., G.G.; Materials – Y.T., G.G., M.H.T.; Data collection &/or processing – Ş.H., V.D., G.G.; Analysis &/or interpretation – Ş.H., Y.T., G.G.; Literature search – Ş.H., V.D., M.H.T.; Writing – Ş.H., V.D., M.H.T.; Critical review – Ş.H., Y.T., M.H.T.

References

- 1.Behçet H. Ueber rezidivierende aphtose, durch ein virus verursachte geschwure am mund, am auge und an den genitalien. Dermatol Wochenschr. 1937;105:1152–7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akar H, Konuralp C, Akpolat T. Cardiovascular involvement in Behçet's disease. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg. 2003;3:261–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nojiri C, Endo M, Kayanagi H. Conduction disturbance in Behçet's disease. Association with ruptured aneurysm of the sinus of valsalva into the left ventricular cavity. Chest. 1984;86:636–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.86.4.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Duffy JD. Vasculitis in Behçet's disease. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1990;16:423–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lakhanpal S, Tani K, Lie JT, Katoh K, Ishigatsubo Y, Ohokubo T. Pathologic features of Behçet's syndrome:a review of Japanese autopsy registry data. Hum Pathol. 1985;16:790–5. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(85)80250-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morelli S, Perrone C, Ferrante L, Sgreccia A, Priori R, Voci P, et al. Cardiac involvement in Behçet's disease. Cardiology. 1997;88:513–7. doi: 10.1159/000177401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Göldeli O, Ural D, Komsuoğlu B, Ağaçdiken A, Dursun E, Cetinarslan B. Abnormal QT dispersion in Behçet's disease. Int J Cardiol. 1997;61:55–9. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(97)00120-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schiff S, Moffatt R, Mandel WJ, Rubin SA. Acute myocardial infarction and recurrent ventricular arrhythmias in Behçet's syndrome. Am Heart J. 1982;103:438–40. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(82)90289-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antzelevitch C, Shimizu W, Yan GX, Sicouri S. Cellular basis for QT dispersion. J Electrocardiol. 1998;30(Suppl 168-75) doi: 10.1016/s0022-0736(98)80070-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kors JA, Ritsema van Eck HJ, van Herpen G. The meaning of the Tp-Te interval and its diagnostic value. J Electrocardiol. 2008;41:575–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2008.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Antzelevitch C, Sicouri S, Di Diego JM, Burashnikov A, Viskin S, Shimizu W, et al. Does Tpeak-Tend provide an index of transmural dispersion of repolarization? Heart Rhythm. 2007;4:1114–6. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaplan O, Kurtoglu E, Nar G, Yasar E, Gozubuyuk G, Dogan C, et al. Evaluation of Electrocardiographic T-peak to T-end Interval in Subjects with Increased Epicardial Fat Tissue Thickness. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2015;105:566–72. doi: 10.5935/abc.20150124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aytemir K, Ozer N, Aksoyek S, Ozcebe O, Kabakci G, Oto A. Increased QT dispersion in the absence of QT prolongation in patients with Behcet's disease and ventricular arrhythmias. Int J Cardiol. 1998;67:171–5. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(98)00322-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sayin MR, Akpinar İ, Gursoy YC, Kiran S, Gudul NE, Karabag T, et al. Assessment of QRS duration and presence of fragmented QRS in patients with Behçet's disease. Coron Artery Dis. 2013;24:398–403. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0b013e328361a978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.[No authors listed] Criteria for diagnosis of Behçet's disease. International Study Group for Behçet's Disease. Lancet. 1990;335:1078–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castro Hevia J, Antzelevitch C, Tornés Bárzaga F, Dorantes Sánchez M, Dorticós Balea F, Zayas Molina R, et al. Tpeak-Tend and Tpeak-Tend dispersion as risk factors for ventricular tachycardia/ventricular fibrillation in patients with the Brugada syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:1828–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.12.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smetana P, Schmidt A, Zabel M, Hnatkova K, Franz M, Huber K, et al. Assessment of repolarization heterogeneity for prediction of mor-tality in cardiovascular disease:Peak to the end of the T wave interval and nondipolar repolarization components. J Electrocardiol. 2011;44:301–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Erikssen G, Liestøl K, Gullestad L, Haugaa KH, Bendz B, Amlie JP. The terminal part of the QT interval (T peak to T end):A predictor of mortality after acute myocardial infarction. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2012;17:85–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-474X.2012.00493.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zehir R, Karabay CY, Kalaycı A, Akgun T, Kılıcgedik A, Kırma C. Evaluation of Tpe interval and Tpe/QT ratio in patients with slow coronary flow. Anatol J Cardiol. 2015;15:463–7. doi: 10.5152/akd.2014.5503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta P, Patel C, Patel H, Narayanaswamy S, Malhotra B, Green JT, et al. T(p-e)/QT ratio as an index of arrhythmogenesis. J Electrocardiol. 2008;41:567–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2008.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gürün C, Ercan E, Ceyhan C, Yavuzgil O, Zoghi M, Aksu K, et al. Cardiovascular involvement in Behçet's disease. Jpn Heart J. 2002;43:389–98. doi: 10.1536/jhj.43.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Güllü IH, Benekli M, Müderrisoğlu H, Oto A, Kansu E, Kabakçi G, et al. Silent myocardial ischemia in Behçet's disease. J Rheumatol. 1996;23:323–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shimizu M, Ino H, Okeie K, Yamaguchi M, Nagata M, Hayashi K, et al. T-peak to T-end interval may be a better predictor of high-risk patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy associated with a cardiac troponin I mutation than QT dispersion. Clin Cardiol. 2002;25:335–49. doi: 10.1002/clc.4950250706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]