Abstract

Many time-series analysis techniques use sliding window approaches or are repeatedly applied over a continuous range of parameters. When combined with a significance test, intrinsic correlations among the pointwise analysis results can make falsely positive significant points appear as continuous patches rather than as isolated points. To account for this effect, we present an areawise significance test that identifies such false-positive patches. For this purpose, we numerically estimate the decorrelation length of the statistic of interest by calculating correlation functions between the analysis results and require an areawise significant point to belong to a patch of pointwise significant points that is larger than this decorrelation length. We apply our areawise test to results from windowed traditional and scale-specific recurrence network analysis in order to identify dynamical anomalies in time series of a non-stationary Rössler system and tree ring width index values from Eastern Canada. Especially, in the palaeoclimate context, the areawise testing approach markedly reduces the number of points that are identified as significant and therefore highlights only the most relevant features in the data. This provides a crucial step towards further establishing recurrence networks as a tool for palaeoclimate data analysis.

Keywords: time-series analysis, significance testing, complex networks, tree rings

1. Introduction

Detecting and characterizing anomalies in time series is an important task in dynamical systems theory with many different fields of applications such as medicine, finance or climate [1–3]. Among others, complex networks and recurrence-based methods [4–9] have provided valuable insights into the underlying dynamics of experimentally measured or otherwise observed real-world systems, i.e. systems for which the dynamics cannot be assessed analytically. In particular, recurrence network analysis (RNA) [9–14] has been shown to be related to a generalized notion of dimensionality via the network transitivity and, thus, can be used to classify the complexity of the system's dynamics [15]. Locating possibly interesting effects in a non-stationary time series in time can be achieved by using a sliding window approach, that is, by splitting the time series into several possibly overlapping pieces and performing the analysis for each ‘window’ separately. Thereby, it is possible to quantify time-dependent dynamical complexity from the time series. This sliding window approach along with RNA has already been demonstrated to be particularly useful for detecting dynamical anomalies in time series of different types and to have great potential for characterizing the dynamics of a system from a measured time series [6,16–19].

A common problem in such analysis methods is the question of how to exactly define an anomaly. Usually, this is done by employing surrogate datasets according to some null hypothesis and then pointwise testing the analysis results against this null hypothesis. In the case of a windowed analysis or when repeating the analysis for a certain set of analysis parameters, such as, for example, window size or embedding delay, multiple testing corrections are required as the same null hypothesis is tested multiple times based on (partially) the same data [20]. Also, for windowed analyses with largely overlapping windows, correlations in time can easily lead to sequences of apparently significant points. When an additional varying analysis parameter is considered, correlations may also be present with respect to this parameter. Taken together, false-positive points may also occur as continuous patches in the two-dimensional (time, parameter) plane and not only as isolated points as assumed by classical pointwise tests. Maraun et al. recognized this problem for time scale resolved analyses using wavelets and developed an areawise significance test for the wavelet spectrogram and coherence based on the reproducing kernel of the wavelet [21]. In the following, we refer to the correlations among the pointwise analysis results that lead to such patches of false positives as intrinsic correlations of the analysis method within the time and the parameter domains, respectively.

In fact, an equivalent to the wavelet reproducing kernel that analytically quantifies the intrinsic correlations of a method is generally not available such that a direct translation of this framework to other methods is not possible. Nevertheless, the introduction of a comparable areawise significance test is of utmost importance when trying to detect anomalies in time series. The general idea of an areawise significance test has also been pointed out in [22] in the context of visibility graphs. We here introduce a generalized version of the areawise significance test of Maraun et al. that can in principle be applied to any time-series analysis method that is applied over a certain range of parameters. This generality comes at the cost of no longer having an analytical framework to assess the intrinsic correlations. Instead, a numerical analysis is pursued.

By focusing on an application of windowed (scale-specific) RNA to a palaeoclimate time series of tree ring width indices, we, on the one hand, contribute to a deeper understanding of past climate variability and the climate system itself and, on the other hand, promote the potentials of also using nonlinear analysis methods in this area. Due to the complex and often partially manual preprocessing necessary to account for the supposed growth curves of individual trees, proxy time series from tree ring archives rarely exhibit unambiguously interpretable low-frequency variability, while providing relatively trustworthy recorders of high-frequency (interannual) variability. This mismatch between the actual information contents at different time scales is why previous applications of RNA in a palaeoclimate context have focused on other types of archives. The currently used framework of RNA is expected to provide better interpretable results for archives that equally represent climate variability across all relevant timescales. The concept of the areawise significance test as presented here provides us with a versatile tool to start exploring the suitability of tree ring archives for windowed RNA and related techniques. Still, we stress that an application of the proposed methods to other types of datasets as well as the combination of other methods (such as, for example, analyses based on recurrence quantification analysis [5], visibility graphs [22] or climate networks [23]) with the areawise significance test is equally possible.

This paper is organized as follows: First, we introduce the basic theory of windowed traditional and scale-specific RNA and of the areawise significance tests in §2. Then, we present the results of the areawise significance tests for both methodological approaches with an application to a synthetic time series of a non-stationary Rössler system and a palaeoclimate time series in §4. Finally, we summarize our conclusions in §5.

2. Theory

(a). Windowed recurrence network analysis

RNA transforms a given time series x(t) into a network by making use of the concept of recurrences in phase space [11]. The nodes of the network correspond to the measured values in the system's phase space xi = x(ti) and are associated with a time ti. Edges are drawn between pairs of nodes if the distance between these nodes in phase space measured with respect to a certain norm ∥ · ∥ is smaller than a chosen threshold ϵ. Formally, the entries of the adjacency matrix A of a recurrence network are given as

with θ( · ) being the Heaviside function. The delta functions δi,j exclude self loops in the network. In this work, the threshold ϵ will be chosen such that a fixed recurrence rate is achieved and distances in phase space will be measured using the maximum norm

with m being the dimension of the phase space. This approach is closely related to the concept of recurrence plots [4] and recurrence quantification analysis [5] by reinterpreting the underlying recurrence matrix as the adjacency matrix of the network. Other than recurrence quantification analysis, RNA does not take into account the time ordering of the state vectors, instead it only captures geometric properties of the system's attractor in phase space and, thus, can give complementary insights with respect to recurrence quantification analysis [15]. The transitivity of the recurrence network has been found to be particularly useful to detect anomalies in the system's dynamics. It is defined as

and can be interpreted as the probability that two randomly chosen neighbours of a randomly chosen node are mutually connected. High values of the transitivity have been found to be related to lower-dimensional dynamics of the system while low values of the transitivity have been associated with higher-dimensional dynamics [12,15]. More explicitly, corresponds to a generalized fractal dimension [15].

As this method studies recurrences in phase space, the higher-dimensional phase space of the system usually needs to be reconstructed from the measured, univariate time series prior to the analysis. This can be done using uniform time delay embedding where the higher-dimensional coordinates of the system are given by delayed versions of the measured time series

with m being the embedding dimension and τ the embedding delay [24,25]. For noisy and finite data, the choice of the delay may influence the results significantly [26]. Also, this method requires regularly sampled data, such that, for irregularly sampled data, interpolation is necessary. Given some data, how to choose the optimal embedding is still an open question and will generally also depend on the purpose of the embedding [27]. As we here only deal with regularly sampled time series, we choose the delay time according to the first zero of the autocorrelation function [1,2,28,29] and the embedding dimension following the false nearest neighbour criterion [30].

To detect dynamical anomalies in a time series using RNA, we use a windowed approach (wRNA); that is, we perform the analysis as outlined above for windows of fixed size W with mutual offset dW. Thereby, we obtain a time series of each considered network measure. The times associated with the values of the network measures correspond to the latest time covered in the network, i.e. we consider the network measure to quantify the dynamics of the preceding W time points. This windowed analysis can be repeated for various choices of the analysis parameter W. In this case, the results can be visualized by colour coding in a plane with time and window width axes.

Given the results of the windowed RNA, we require some kind of significance test to assess at which times the dynamics shows anomalous behaviour. Usually, a pointwise significance test based on surrogate data is applied in this kind of analysis. Following the best practices in the literature, we here use random shuffling surrogates for the pointwise significance test which essentially tests the RNA measures for stationarity. For every window width W, W state vectors of the complete embedded time series are drawn at random. From this set of state vectors, a recurrence network is constructed and the network measure of interest is calculated. This is repeated Ns times. Confidence bounds can then be defined using lower and upper percentiles of the Ns surrogate values of the network measure. Here, we apply 95% two-sided confidence bounds, i.e. use the 2.5% and the 97.5% quantiles of the surrogate network measure distributions estimated from Ns = 1000 surrogates.

(b). Windowed scale-specific recurrence network analysis

Scale-specific recurrence network analysis (SSRNA) provides an extension of traditional RNA where the input time series is filtered for variations at distinct time scales (or, equivalently, frequencies) before transforming it to a network as outlined above. Thereby, different time scales of the system can be studied separately, which has already been successfully applied to classify systems of various types [31–36]. We emphasize that in some cases, the term ‘multi-scale’ analysis has been used in the past to describe this type of analysis. However, previous works have employed the latter term for describing different analysis strategies in a non-unique fashion, allowing for example for different approaches for filtering the time series to assess the different time scales [31,33,34,37,38]. Those approaches comprise, among others, moving averages [39], the empirical mode decomposition [40], singular spectrum analysis [41,42], and the discrete and the continuous wavelet transform [43,44]. All those methods have their own strengths and limitations. The empirical mode decomposition, for example, is an efficient data-adaptive (DA) routine, but due to its adaptivity, the resulting modes are not necessarily frequency-stable. Singular spectrum analysis and the discrete wavelet transform, on the other hand, only filter the data at distinct frequencies and frequency bands, respectively. Given the existence of other established ‘multi-scale’ nonlinear time series analysis concepts like multi-scale entropy [45], which explicitly combines the information obtained for different scales, we here prefer to use the term ‘scale-specific’ to rather highlight that we may also use this analysis technique for studying the dynamics at one specific time scale only. An analogous terminology has been recently adopted in the context of functional climate networks [46], which are known to exhibit close conceptual similarities with recurrence networks [47].

In this work, we combine SSRNA with the sliding window approach (wSSRNA) and, in analogy to reference [46], use the continuous wavelet transform [44] to filter the input time series. To be more precise, given the measured time series x(t), each dimension of the embedded time series x is filtered separately using the continuous wavelet transform WΨ with respect to the wavelet Ψ

at different scales s and times b. The bar denotes the complex conjugate. We use the complex Morlet wavelet

Because of its analytical form and its equal variance in the time and the frequency domain, this mother wavelet is particularly suitable for the continuous wavelet analysis of geoscientific time series [44]. The parameters of the Morlet wavelet are chosen here as B = 2.0 and C = 1.0 and correspond to the bandwidth and the centre frequency, respectively. In general, the centre frequency sets the frequencies on which the analysis is focused (in units of 1/dt with dt the average sampling rate of the data), while the bandwidth is related to the resolution of the wavelet analysis. Both parameters can, for example, be chosen by matching the centre frequency and the bandwidth of the wavelet with the main frequency of the analysed data and its bandwidth. The real part of the wavelet transform for each dimension is then combined to the final filtered time series. For the following wRNA, we cut off the first and last

points where supp(Ψ) is the support of the wavelet. To perform the wavelet transform, we here use the python package pywt where the support is given as supp(Ψ) = 16s + 1, i.e. 8s points to each side. The window size of the wRNA is chosen according to the support and the minimum required window width of W = 100 for reliable results [13,16] as

| 2.1 |

The pointwise significance test is performed for each scale as described above for the common wRNA.

(c). Areawise significance tests

Significance tests doubtlessly play an important role in data analysis, but often, as argued above, the same null hypothesis is tested repeatedly within the analysis which leads to multiple testing problems that need to be corrected for [20]. Additionally, correlations between the analysis results for sliding window approaches or for varying analysis parameters may lead to patches of false positives [21]. Many data analysis techniques suffer from this problem, for example, continuous wavelet analysis, wRNA, and wSSRNA. In wavelet analysis, the reproducing kernel of the wavelet [44] quantifies the intrinsic correlations that are present within the wavelet spectrogram and can thus be used to define an areawise significance test. The basic idea of that areawise test is that a pointwise significant point is considered to be areawise significant if all points in its neighbourhood defined by the reproducing kernel of the wavelet are also pointwise significant [21]. Thereby, pointwise significant patches that are smaller than the reproducing kernel are sorted out.

(i). General idea of the areawise significance test

Even though, for an arbitrary analysis method, an analytical assessment of the intrinsic correlations is not always possible, we can still transfer the idea of the areawise significance test from the continuous wavelet transform to other data analysis techniques. For this, we use numerical estimates of the intrinsic correlations between pointwise analysis results with respect to some distinct null model. In the following, we provide a general recipe for the areawise significance test that we will later apply to the case of windowed RNA and windowed SSRNA:

-

(i)

Identify the domains, e.g. time and systematically varied analysis parameters, in which the pointwise significance test is repeatedly applied.

-

(ii)

For each of those domains, identify the parameters on which the intrinsic correlations depend.

-

(iii)

Choose a null model and quantify the intrinsic correlations by numerically estimating the decorrelation length of the analysis results for the corresponding null model as a function of the parameters identified in the previous step.

-

(iv)

For each pointwise significant point, perform the areawise test by identifying the scale of decay of the correlations for the corresponding values of the analysis parameters and checking whether all points in the neighbourhood with respect to time and analysis parameters of the chosen point are also pointwise significant. The exact size of this neighbourhood is fixed according to the scale of decay of the intrinsic correlations determined in the previous step. If the latter condition applies, then the point is considered to be areawise significant.

More formally, given a time series x(t) that we want to analyse, we first need to identify the domains di, i = 1, …, n, in which the analysis is applied. Here, we restrict ourselves to the case of n = 2 but a generalization to a higher number of dimensions is straightforward. That is, after analysing the time series x(t), we have a matrix R = (Rk1,k2) of analysis results, where k1∈[1, N1] and k2∈[1, N2] with N1,2 being the number of parameter values analysed in the corresponding domain and Pj = (Pj1, …, PjNj) (j = 1, 2) being vectors containing the corresponding analysis parameters. Additionally, we require a pointwise significance test of the data resulting in a binary matrix Spw with Spwk1,k2 = 1 if the result Rk1,k2 is pointwise significant and Spwk1,k2 = 0 if not. Second, the parameters pj, j = 1, …, Np, on which the intrinsic correlations depend, need to be identified. We here set Np = 1 and denote p1 = p, while again, a generalization to higher Np is straightforward.

To numerically assess the intrinsic correlations, we need to specify a null model and create a certain number N0 of realizations of this null model which are analysed over the range of analysis parameters P1 and P2. Then, for each domain di, the decorrelation length τdi can be estimated by calculating correlations between the analysis results for different analysis parameters. The value of each parameter at which the correlation falls below 1/e is used as a proxy for the corresponding decorrelation length. This is repeated for different values of the parameter p and an average over the N0 realizations is taken. By applying a linear fit

| 2.2 |

the decorrelation length is estimated as a function of the respective parameter p which we use as heuristic estimate of the correlation decay. It should be noted that there is no particular reason to prefer a linear fit over some more general fitting procedure. However, for the sake of simplicity and because it seems to capture the behaviour of the decorrelation lengths reasonably well in many cases, we restrict ourselves here to the linear model.

Finally, a pointwise significant point in R, i.e. a point with Spwk1,k2 = 1, is also areawise significant Sawk1,k2 = 1 if

| 2.3 |

i.e. if all points in the neighbourhood of Rk1,k2 are also pointwise significant. The coefficients ldx are given by

where the parameters mdx and ndx are given by the linear fit of the decorrelation length (2.2) for the chosen null model. We here assume that the shape of the correlation kernel is rectangular. Other shapes such as an ellipse or a rhomboid could in principle also be considered and implemented in an analogous way. Still, as we do not have any analytical treatment of the decay of the correlations for arbitrary parameters, the rectangular shape is the one with the least implicit assumptions as, in this case, the decay of correlations in d1 and d2 is assumed to be mutually independent.

(ii). Areawise confidence levels

With this form of the areawise test, it is not directly clear what the areawise confidence levels are. For the wavelet spectrum and coherence, Maraun et al. chose the actual size of the area of the reproducing kernel depending on the scale such that for a given areawise confidence level 1 − αaw the area of the patches of pointwise significant points Apw and the area of the patches of areawise significant points Aaw are related as Aaw = αawApw [21]. Here, we look at the problem of determining the confidence level from the opposite point of view. After having quantified the intrinsic correlations for a given null model, we can apply the areawise significance test to a certain number of sets of data created according to the null model. We can then calculate the average fraction of areawise and pointwise significant points and use this fraction to determine the areawise confidence level saw

| 2.4 |

That is, instead of fixing the number of areawise significant points and varying the size of the correlation kernel, we here fix the scale of decay of the intrinsic correlations (according to some null model) while the number of areawise significant points in a dataset can vary and is not set by the number of pointwise significant points in the dataset and the areawise confidence level. By additionally taking into account the confidence level that was used for the pointwise test spw, we obtain the result that every areawise significant point detected using this framework is significant (with respect to the corresponding null model) up to a confidence level stot = spwsaw.

3. Description of the data

(a). Model system

As a first example, we attempt to detect dynamical anomalies in a Rössler system with time varying parameter b(t). The system is defined by the set of ordinary differential equations [48]

| 3.1 |

with fixed parameters a = 0.2 and c = 5.7 and time varying parameter b(t) = b0 + Δb(t − t0) with b0 = 0.02 and Δb = 0.001. We numerically solve this system of ODEs with a temporal resolution of Δt = 0.1 for times in the range [0, 630], discard the first 300 points and then use every third point of the remaining time series to end up with a time series of length N = 2000. As initial conditions, we use x(0) = 0.5, y(0) = 0 and z(0) = 0. The resulting time series and a bifurcation diagram of the Rössler system are shown in figure 1. The bifurcation diagram was obtained by integrating the system for a long time (in total 10 000 points) for a fixed value of b and then recording the values of x when y changed its sign from positive to negative for the last 2500 points. This was repeated over the relevant range of b values. That is, the bifurcation diagram represents the dynamics of the stationary Rössler system while the time series we use contains transients due to the gradual increase of the bifurcation parameter in every integration step.

Figure 1.

Transient time series of the x-component of the Rössler system with parameter b varying in every integration step (a) and bifurcation diagram (see text) for the corresponding stationary system (b).

(b). Palaeoclimate data

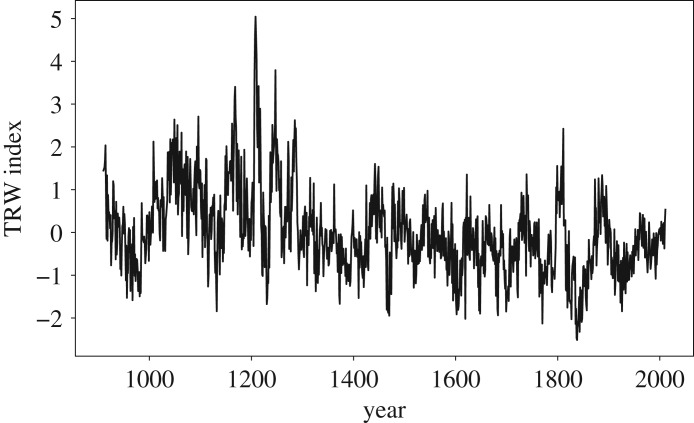

In a second example, we apply our analysis framework to detect dynamical anomalies in a real-world palaeoclimate dataset of tree ring width indices. Tree ring width and other dendrochronological variables play an important role for reconstructing climate variables such as temperature for the recent past, e.g. the last millennium. However, the question whether proxy data from tree rings can also be used for inferring information about past climate variability using wRNA has not yet been reliably answered. As a first step towards studying this question, we here consider a dataset of tree ring width chronologies of subfossil and living black spruce obtained at six lakes in East Canada [49]. This dataset has been ranked high by Esper et al. [50] where different tree ring chronologies have been compared with respect to their data homogeneity, sample replication, growth coherence, chronology development, and climate signal. Thus, this dataset serves as a good starting point to explore the suitability of tree ring archives for wRNA.

The tree ring width chronology from East Canada has been used to reconstruct annual summer temperatures in that region and has been found to strongly respond to volcanic activity. The authors of [49] conjecture that large and successive eruptions can lead to cold episodes that may be sustained due to a complex sea-ice-ocean feedback, which makes this region more sensitive to such events than for example Eurasia. In particular, the Samalas eruption 1257 and the Tambora eruption 1815 have been highlighted to influence tree growth in East Canada. Also other explosive volcanic eruptions have been proposed to particularly influence Northern Hemisphere climate, for example, by triggering the Little Ice Age [51–53]. An overview over the largest explosive volcanic eruptions can be found in table 1. To study whether one can find an imprint of those eruptions in the system dynamics by applying wRNA, we choose the chronology of lake L22 (54.15° N, 70.29° W). It has a good replication of 292 subfossil and 25 living trees and we expect the data from the other lakes to show similar behaviour as this one. The corresponding data are displayed in figure 2.

Table 1.

List of the 10 largest explosive volcanic eruptions with respect to their global aerosol forcing since 1200 AD as reported by Sigl et al. [54]. Unattributed volcanic events are denoted as UE and uncertain attributions are marked by (?).

| volcano | region | year | forcing [Wm−2] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Samalas | Indonesia | 1257 | −32.8 |

| Kuwae | Vanuatu | 1458 | −20.5 |

| Tambora | Indonesia | 1815 | −17.1 |

| UE | 1230 | −15.9 | |

| Laki | Iceland | 1783 | −15.5 |

| UE | 1809 | −12.0 | |

| Parker | Philippines | 1641 | −11.8 |

| Huaynaputina | Peru | 1601 | −11.6 |

| UE | 1695 | −10.2 | |

| Quilotoa (?) | Ecuador | 1286 | −9.7 |

Figure 2.

Tree ring width (TRW) index time series from trees in East Canada [49] as a function of time.

4. Results

(a). Windowed recurrence network analysis

(i). Areawise test for wRNA

For wRNA, the pointwise significance test is repeatedly applied in the time and window width domains. That is, those two are the domains in which intrinsic correlations may play a role, i.e. d1 = t and d2 = W. As those correlations in the analysis should be stationary, we identify the window width as the parameter on which the correlations possibly depend, p = W.

To quantify the correlations in the time and window width domains, we first need to choose the null model of our significance test. For this, we consider three distinct cases.

-

—The first and simplest case is Gaussian white noise (GWN) with probability density function

where σ is the standard deviation and μ is the mean of the distribution that are chosen in accordance with the mean and standard deviation of the studied data as given in table 2.4.1 -

—In the second case, we consider the null model to be an autoregressive process of order 1 (AR(1) process)

with ϵt being a Gaussian random variable with zero mean μ and constant standard deviation σ(ϵt). The model parameters are the constant offset (drift term) c and the scaling factor α. The standard deviation σ and the model parameters are obtained by fitting an AR(1) process to the studied data. Also the initial condition x(0) is chosen according to the data. The fitting parameters for the two studied time series are given in table 2.4.2 -

—

Finally, we consider a DA null model. For this, we create realizations of iterative amplitude-adjusted Fourier transform (iAAFT) surrogates of the time series that we want to study. Details on the creation of iAAFT surrogates can, for example, be found in [55]. The iAAFT surrogate time series have the same amplitude distribution as the original time series and also the correlation structure of the series is preserved.

Table 2.

Properties and fitting parameters for the AR(1) model of the two datasets presented in §3.

| data | μ | σ | x(0) | c | α | σ(ϵt) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rössler | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.1897 | 0.0 | 0.9427 | 0.3337 |

| TRW index | 1.02 | 0.192 | 1.303 | 0.2738 | 0.7327 | 0.1308 |

In each case, we test whether the analysis results for the respective dataset can be equivalently obtained by a time series of the kind of the corresponding null model, that is, by GWN, an AR(1) process or a time series with the same amplitude distribution and correlation structure as the original one, but otherwise random. Thus, the significance test gives information about structures in the original time series that are absent in the surrogate data [55].

It should be noted that the three different types of null models described above correspond to three different kinds of null hypotheses on the nature of the underlying process. Specifically, while (localized) deviations from the obtained test distributions generally indicate some non-stationarity of the tested time-series property, we assume the latter to originate from either a white noise (uncorrelated) process (GWN), a short-term correlated process (AR(1)), or a process with exactly the same linear correlation structure as the data under study (iAAFT surrogates). Specifically, GWN surrogates retain only the global mean and variance of the original data, while iAAFT surrogates conserve the complete mean linear autocorrelation structure of the data but lose information about possible nonlinear effects on the mutual arrangements of the different components of the embedding vectors in the (reconstructed) phase space. Comparing the test results among such a hierarchy of null models may therefore help identify the actual source of non-stationarity. In this context, more complex types of surrogate data could be considered, too, but shall not be further discussed in this work.

In order to quantify the intrinsic correlations of the different null models in both the time and the window width domain, we create N0 = 100 realizations of the processes according to equations (4.1) and (4.2) and of the iAAFT surrogates for each dataset to be studied. The length of the first two processes is chosen according to the length of the original data. We then embed the resulting univariate time series using uniform time delay embedding with embedding dimension m = 3 and embedding delay τ chosen according to the first zero of the autocorrelation function. Thus, for the DA iAAFT surrogates, the embedding delay is identical to that of the original time series as the correlation structure is preserved, while for the GWN and AR(1) surrogates, the embedding delay will generally differ from that of the original time series. We apply wRNA for window widths W∈[100, 300] with step size ΔW = 1 as outlined in §§2a. For each window width, the offset of the windowed analysis is given as dW = 1, that is, we have largely overlapping windows in the time domain leading to intrinsic correlations.

To assess those correlations, we take the resulting network transitivity as a function of time for a fixed W and calculate the lagged autocorrelation up to a maximum lag of (N − Wmax)/2. This corresponds to calculating the correlation between the transitivity of two recurrence networks of W nodes each where W − l nodes are identical, with l being the time lag. We next estimate the decorrelation length, i.e. the value of the lag at which the autocorrelation falls below 1/e, for every value of W and all 100 realizations. Figure 3a exemplarily shows the lagged autocorrelation function for one realization of GWN and different window widths. Figure 4 shows the mean and the standard deviation of the resulting decorrelation length as a function of the window width obtained from 100 realizations for the different null models adapted to the non-stationary Rössler system and the palaeoclimate time series of tree ring width indices introduced in §3. We observe a behaviour that can be approximated by a linear model. The fitting parameters and the coefficient of determination R2 of the linear model are shown in table 3.

Figure 3.

(a) Lagged autocorrelation function of the transitivity in the time domain and (b) correlation between the transitivity results in the window width domain for different values of the window width (W increasing from light to dark red) for one of the N0 realizations of GWN. The dashed lines denote the value of 1/e and 2/e, respectively (see text). (Online version in colour.)

Figure 4.

Mean (points), standard deviations (error bars) and linear fits (lines) of the decorrelation lengths as a function of the window width W for correlations in the time domain of the wRNA results for (a) the non-stationary Rössler system and (b) the palaeoclimate time series of tree ring width indices using the three different null models: GWN (blue, dash-dotted), AR(1) process (green, dashed) and data-adaptive null model (red, solid). (Online version in colour.)

Table 3.

Parameters and coefficients of determination of the linear fits of the decorrelation length as a function of the window width for the network transitivity of wRNA and corresponding significance levels for the different datasets and null models in the time and the window width domain.

| data | null model | domain | m | n | R2 | saw | spw | stot |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rössler | GWN | t | 0.3813 | −2.364 | 0.9980 | |||

| GWN | W | 0.2527 | −5.081 | 0.9991 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 0.94 | |

| AR(1) | t | 0.5325 | 13.30 | 0.9889 | ||||

| AR(1) | W | 0.3348 | −1.631 | 0.9976 | 0.88 | 0.95 | 0.84 | |

| DA | t | 0.5276 | −12.74 | 0.9976 | ||||

| DA | W | 0.4102 | −32.54 | 0.9967 | 0.90 | 0.95 | 0.86 | |

| TRW index | GWN | t | 0.2460 | 12.36 | 0.9943 | |||

| GWN | W | 0.1678 | 8.753 | 0.9979 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 0.94 | |

| AR(1) | t | 0.2616 | 15.32 | 0.9947 | ||||

| AR(1) | W | 0.2270 | 0.3893 | 0.9913 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 0.94 | |

| DA | t | 0.2217 | 26.77 | 0.9813 | ||||

| DA | W | 0.3148 | −15.74 | 0.9997 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 0.94 |

For the correlations in the window width domain, we calculate the Pearson correlation between the analysis results of a fixed window width W and those of the previous and following window widths. This is repeated for all values of W and all N0 realizations. Figure 3b shows the result for one of the realizations of GWN. We observe a rather symmetric behaviour in forward and backward correlations. Also, the correlations generally remain larger over a wider range of parameters than the correlations in the time domain. Indeed, for many realizations, the correlations in the window width domain stay above 1/e for all analysed parameter values. To evaluate the decorrelation length in the window width domain as a function of the window width, we thus choose the decorrelation length to be the value of ΔW at which the backward correlations fall below 2/e. This choice of the decorrelation threshold ensures that enough values of W fall below the threshold to reasonably fit the decorrelation time. The results are shown in figure 5 analogously to the results for the time domain. Again, we observe an approximately linear dependence of the decorrelation length on the window width. The fitting parameters and the coefficients of determination are shown in table 3. We observe that the values of R2 for the fitting in both the time and the window width domain are very high such that a linear fit seems to be reasonable for those two datasets and wRNA.

Figure 5.

Same as in figure 4, but for correlations in the window width domain. (Online version in colour.)

Given the fitting parameters mt/W and nt/W for the corresponding null model and the pointwise significance matrix Spw of the transitivity of the wRNA over the parameter set P, we can now define the areawise significance matrix Saw as having entries Sawi,j = 1 if condition (2.3) holds. The confidence levels of the detected areawise significant points calculated according to equation (2.4) over the N0 = 100 different realizations of the null models are also given in table 3. The confidence levels are similarly high for all null models for the tree ring width index and the GWN model for the non-stationary Rössler system. For the AR(1) and the DA null model of the Rössler system, the confidence levels are slightly lower. Those lower values may be due to the fact that we chose the backward correlation for fitting the correlation lengths in the window width domain. This possibly leads to a bias towards shorter decorrelation lengths. Still, when looking at the confidence levels for this choice for the tree ring width index dataset and the GWN null model, we find that the backward correlations manage to prevent most of the spurious pointwise significant points.

(ii). Application to model system

For the wRNA of the non-stationary Rössler system presented in §3, we use time delay embedding with embedding delay τ = 5〈dt〉 corresponding to the first minimum of the autocorrelation function and embedding dimension m = 3 as suggested by the false nearest neighbour criterion. The window width was varied in the interval W∈[100, 300] with step size ΔW = 1 and offset dW = 1. The recurrences were defined using maximum norm and a fixed recurrence rate of RR=0.05.

As described above, we apply the areawise significance test for three different null models, one testing against Gaussian white noise, another testing against an AR(1) process and the third being the DA null model using iAAFT surrogates. The parameters of the linear fits and the corresponding confidence levels are given in table 3. The results of the wRNA including a pointwise random shuffling significance test with 95% confidence bound and the areawise significance test for the three null models are shown in figure 6.

Figure 6.

Transitivity of windowed recurrence network analysis (colour coded) of the non-stationary Rössler system with pointwise significance test using random shuffling surrogates (a) and with areawise significance test (b). The test results for the GWN null model are shown by dark blue, the AR(1) null model by dark green and the data-adaptive null model by dark red lines. The vertical lines indicate the different regimes of the stationary system according to the bifurcation diagram in figure 1. (Online version in colour.)

First, we observe that the results for the areawise significance tests for the different null models are in good agreement. The areas detected with the DA null model are generally smaller than those detected with the other two null models but the regions in which areawise significant points are detected are the same for all null models. In the bifurcation diagram of the Rössler system, as shown in figure 1, we see chaotic behaviour for b in the range b∈[0.09, 0.26] followed by a less chaotic regime for b∈[0.26, 0.37] and an again chaotic behaviour from b = 0.37 onward with short interruption for b∈[0.50, 0.51]. It should be noted that, as the system considered here shows transient dynamics due to the increase in the parameter b in every integration step, bifurcations can emerge later (or not at all) in our system as also observed in [16]. The results for the areawise significance test show three significant patches with anomalously low values of the transitivity, indicating higher-dimensional dynamics, in the range where we would expect for the stationary Rössler system. Between the second and third patch, we observe (non-significant) increased values of the transitivity. Also after the third patch, non-significant but increased values of the transitivity are found corresponding to a lower-dimensional dynamics of the system. Finally, at the end of the time series, we find again a small patch of areawise significant anomalously low values of the transitivity that might result from the higher-dimensional behaviour of the system in that parameter range. In summary, by combining wRNA with the areawise significance tests for a transient Rössler system, we are able to detect dynamical anomalies that are consistent but do not fully agree with the different dynamical regimes in the stationary Rössler system.

(iii). Application to palaeoclimate data

To study the palaeoclimate time series described in §3 using wRNA, we again employ uniform time delay embedding with embedding dimension m = 3 and varying embedding delay τ∈[4, 31] years with a step size of Δτ = 3 years. The other parameters of the wRNA are the same as for the Rössler system. For the areawise test with the DA null model, we apply the same iAAFT procedure as before with an embedding delay of τ = 25 years.

The parameters of the linear fits and the confidence levels for the different null models are given in table 3. The results of the wRNA with areawise test for the three null models and for an embedding delay of τ = 25 years are shown in figure 7. We see that the areawise results for the different null models are again in very good agreement, in particular, those for the AR(1) and the DA null model are almost equivalent.

Figure 7.

Transitivity of windowed recurrence network analysis (colour coded) for embedding delay τ = 25 years of the tree ring width index data from East Canada with pointwise significance test using random shuffling surrogates (a) and with areawise significance test (b). The results for the GWN null model are shown by dark blue, the AR(1) null model by dark green and the data-adaptive null model by dark red lines. The vertical lines denote larger volcanic eruptions that were referred to in [49] and are given in table 1. (Online version in colour.)

We find an areawise significant patch with anomalously low values of the transitivity in the thirteenth century around the time where the Samalas and further larger eruptions took place, coinciding with the onset of the Little Ice Age in Europe. This period has already previously been found to have experienced more complex North Atlantic climate variability [22,56], so that we might have expected a lower value of the network transitivity as compared to the preceding time interval (corresponding to the Medieval Climate Anomaly in Europe) where the climate was relatively stable and thus characterized by less complex dynamics (resulting in a higher value of the transitivity). Interestingly, we do not find any areawise significant patches around the Tambora, the Kuwae and the seventeenth-century eruptions which might indicate that those eruptions did not trigger the same kind of dynamical changes in the climate system as the Samalas eruption or that other processes than the explosive volcanic eruptions initiated or at least contributed substantially to the observed dynamical anomalies.

For the other delay times, we compared the areawise significant patches using the AR(1) null model as this led to results equivalent to the DA null model. The results are shown in figure 8. We observe a consistent pattern of elevated yet not areawise significant values of the network transitivity in the second half of the fourteenth century (i.e. during the Little Ice Age in Europe) for all delay times. We find that for some choices of τ there are no areawise significant patches meaning that the null hypothesis that the underlying process is an AR(1) process cannot be rejected for those values of τ. We also observe that for smaller values of τ we find significant patches at later times after the Tambora eruption while for larger τ we rather find significant patches at earlier times after the Samalas eruption. As the different choices of delay time cover different time scales in the dynamics of the reconstructed system, those results might indicate that the reaction of the climate system to the different eruptions happened on different time scales.

Figure 8.

Transitivity (colour coded) and areawise significance test with respect to the AR(1) null model (green contours) of wRNA of the East Canada tree ring width dataset for different embedding delays τ. (Online version in colour.)

(b). Windowed scale-specific recurrence network analysis

To have a closer look into the dynamics at different time scales, we now define the areawise significance test for windowed SSRNA and apply it to the non-stationary Rössler system and the tree ring width index dataset from East Canada studied in the previous section.

(i). Areawise test for windowed scale-specific recurrence network analysis

For wSSRNA, the domains in which the significance test is repeatedly applied are the time and the scale domain, that is, d1 = t and d2 = s, and the parameter on which intrinsic correlations depend, is the scale, i.e. p = s. Again, we first need to specify the null model against which we want to test the results of the wSSRNA. We choose the same three distinct null models as for the traditional wRNA, GWN, equation (4.1), an AR(1) process, equation (4.2) and the DA null model using iAAFT surrogates of the original time series.

To get an estimate of the intrinsic correlations, we pursue the same numerical approach as before. That is, we evaluate the decorrelation length, i.e. the times at which the correlations fall below 1/e in the time and the scale domain for the different null models and use the results as estimates for the intrinsic correlation lengths depending on the scale of the wavelet transform. The results are visualized in figures 9 and 10. The corresponding fitting parameters and confidence levels are given in table 4. In the time domain, the results are similar for all null models. In the scale domain, the AR(1) and the DA null model yield similar results, though a linear fit might not be appropriate for wSSRNA as also indicated by the low values of R2 in those cases. As the obtained confidence levels are still reasonably high, we here stick to the linear model. With those results, the areawise significance test for wSSRNA can now be defined analogously to that for wRNA by replacing the window widths W with the scales s.

Figure 9.

Mean (points), standard deviations (error bars) and linear fits (lines) of the decorrelation lengths as a function of the scale s for correlations in the time domain of the wSSRNA results for (a) the non-stationary Rössler system and (b) the palaeoclimate time series of tree ring width indices using the three different null models: GWN (blue, dashed-dotted), AR(1) process (green, dashed) and data-adaptive null model (red, solid). (Online version in colour.)

Figure 10.

Same as in figure 9, but for correlations in the scale domain. (Online version in colour.)

Table 4.

Parameters and coefficients of determination of the linear fits of the decorrelation length as a function of the scale for the network transitivity of wSSRNA and corresponding significance levels for the different datasets and null models in the time and the scale domain.

| data | null model | domain | m | n | R2 | saw | spw | stot |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rössler | GWN | t | 4.516 | 19.74 | 0.8836 | |||

| GWN | s | 0.2321 | 1.124 | 0.8529 | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.88 | |

| AR(1) | t | 4.757 | 24.86 | 0.9147 | ||||

| AR(1) | s | 0.4070 | 0.3845 | 0.9023 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.92 | |

| DA | t | 3.483 | 31.30 | 0.6361 | ||||

| DA | s | 0.3982 | 0.8128 | 0.7396 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.90 | |

| TRW index | GWN | t | 3.423 | 22.78 | 0.8210 | |||

| GWN | s | 0.1571 | 1.897 | 0.9594 | 0.90 | 0.95 | 0.86 | |

| AR(1) | t | 3.391 | 25.81 | 0.8833 | ||||

| AR(1) | s | 0.5095 | 0.2727 | 0.9350 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.90 | |

| DA | t | 3.178 | 27.84 | 0.8692 | ||||

| DA | s | 0.4971 | -0.06078 | 0.8701 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.92 |

(ii). Application to model system

As a first test of the windowed scale-specific approach, we continue our analysis of the non-stationary Rössler system studied in §§4aii. The model and analysis parameters are the same as before and we perform the wSSRNA as outlined in §§2b for scales in the range s∈[0.4, 16] in steps of Δs = 0.2. The window width of wSSRNA is chosen according to equation (2.1) and the offset of the windowed analysis is again dW = 1. The fitting parameters for the areawise significance test and the confidence levels for the different null models are given in table 4.

The results of wSSRNA are shown in figure 11. The findings of the areawise test for the AR(1) and the DA null model are very similar, while for the GWN null model, we find some additional areawise significant points. In the following, we will concentrate on areawise significant points with respect to the DA null model. In the regime of b∈[0.09, 0.26] we find both significant high and low values of the network transitivity at intermediate to large scales possibly reflecting higher versus lower-dimensional dynamics playing a role at different scales. For large scales, we observe a large patch of areawise significant high values of the transitivity starting around b = 0.3 and extending also to intermediate scales for b∈[0.37, 0.45]. In the latter regime, from the bifurcation diagram, we would expect higher-dimensional dynamics to play a role. The elevated values of the transitivity may thus be related to the transients from the previous lower-dimensional regime (b∈[0.26, 0.37]) and may indicate that at larger scales, the dynamics is lower dimensional than at smaller scales. For scales between 5 and 10, we find significantly low values of the network transitivity for b∈[0.48, 0.55]. This probably reflects the higher-dimensional dynamics of the system that is also expected from the bifurcation diagram in this regime.

Figure 11.

Transitivity (colour coded) of windowed scale-specific recurrence network analysis for embedding delay τ = 5 of the non-stationary Rössler system with pointwise significance test using random shuffling surrogates (a) and with areawise significance test (b). The results for the GWN null model are shown by dark blue, the AR(1) null model by dark green and the data-adaptive null model by dark red lines. (Online version in colour.)

(iii). Application to palaeoclimate data

We now analyse the tree ring width index dataset from East Canada [49] using wSSRNA as defined in §§2b in combination with the areawise significance tests for the different null models. The embedding and wRNA parameters are the same as in the previous section. The fitting parameters for the different null models and the confidence levels are given in table 4.

The results of wSSRNA are shown in figure 12. First, we observe that for the AR(1) and the DD null model, we only get a very small number of areawise significant points. For the GWN null model, we find more areawise significant points. In particular, we find areawise significant points following the Samalas, the Kuwae and the seventeenth-century eruptions at intermediate to large scales. At smaller scales, i.e. high frequencies, we find areawise significant points that cannot be related to any particular volcanic eruption which reflects that tree rings generally show a stronger variability at high than at low frequencies and thus, that other influences such as local boundary conditions play a larger role at those frequencies. Also, as these points are not significant using the DA null model, we conclude that from this dataset, we cannot learn anything about low-frequency climate variability of the last millennium. Furthermore, systematic studies of w(SS)RNA applied to different proxies time series from the tree archive as well as from other types of palaeoclimate archives will reveal the suitability of this approach for understanding past climate dynamics.

Figure 12.

Transitivity (colour coded) of windowed scale-specific recurrence network analysis for embedding delay τ = 25 years of tree ring width index data from East Canada with pointwise significance test using random shuffling surrogates (a) and with areawise signicicance test (b). The results for the GWN null model are shown by dark blue, the AR(1) null model by dark green and the data-adaptive null model by dark red lines. (Online version in colour.)

5. Conclusion

Dynamical anomalies in time series may provide valuable insights into the system under study, as for example, the climate system. A problem in many time-series analysis methods such as windowed RNA and extensions of it is to quantify the significance of the detected anomalies. Generally, both multiple testing and intrinsic correlations lead to high false-positive rates that need to be corrected. Based on the areawise significance test for the wavelet spectrum [21], we here proposed a more general framework for an areawise significance test that can in principle be combined with any time series analysis method. For this, domains in which a significance test is repeatedly applied need to be identified. Intrinsic correlations in the corresponding domains are estimated numerically by calculating the decorrelation length of the results obtained with a particular analysis method with respect to a chosen null model. Those decorrelation lengths are then used as parameters for the areawise test and can be related to a confidence level of the test. In this work, we considered three null models, one of Gaussian white noise, an AR(1) process and a DA routine using iAAFT surrogates. We combined the areawise significance test with windowed traditional and scale-specific RNA and applied them to a transient synthetic time series and a palaeoclimate time series of tree ring width indices from East Canada.

For the model system and wRNA, we found the resulting network transitivity to be consistent with our expectations for the corresponding stationary system though not all expected bifurcations were detected as significant dynamical anomalies, which might be related to the transient nature of the studied time series. wSSRNA revealed more details of the system dynamics by relating the dimensionality of the dynamics to the different time scales. This highlights the potential of wSSRNA as it may give a more complete picture of the system dynamics than wRNA alone. Also, here, we only studied the network transitivity, but other network measures such as the average path length can be studied in a similar way and, in the case of the non-stationary Rössler system, show comparable results to the network transitivity (not shown).

For the tree ring width index time series and wRNA, we found that, independent of the null model but depending on the embedding delay of the phase space reconstruction, areawise significant dynamical anomalies are apparent either after the Samalas eruption in 1257 or after the Tambora eruption in 1815 while for the Kuwae and the 17th century eruptions, no areawise significant patches appear. This might hint at a reaction at different time scales of the climate system to the different explosive volcanic eruptions. To have a closer look at the time scale dependence, we additionally applied wSSRNA in combination with the areawise significance test to this dataset. In this case, the results depend a lot on the chosen null model. The AR(1) and the DA null model only give a very low number of areawise significant points while the GWN null model shows areawise significant points at lower frequencies after most of the major volcanic eruptions and areawise significant points at higher frequencies that cannot be related to particular eruptions. To draw reliable conclusions about possible dynamical imprints of explosive volcanic eruptions in palaeoclimate archives, a further study of the relation between temperature-sensitive proxies and explosive volcanic eruptions in the last millennium using w(SS)RNA is required. Also, the suitability of different proxy archives for these kinds of analyses should be further studied to better understand methodological potentials and limitations.

Independent of this application to study past climate variability using w(SS)RNA, the areawise significance test can be combined with many other analysis methods. One example where the development of an areawise significance test might yield new insights is that of climate networks [23,57–59] where the results also depend on the chosen window width and intrinsic correlations may be present in time and window width domain. The difference to the example presented here lies in the construction of the networks, which is for climate networks usually based on similarity measures such as the Pearson correlation coefficients between many time series and not on the recurrences in phase space of a single time series. Also, extensions of the current framework of the areawise test are possible. This concerns particularly the fitting procedure of the decorrelation lengths. We here used a linear model but there is no theoretical justification so far to prefer a linear model over any other possible model. For wRNA, we found that the linear model performed very well while for wSSRNA, a nonlinear model seems to be more appropriate. In addition, the shape of the neighbourhood that defines the areawise significance test can be adapted if information about the decay of correlations in the different domains is available. Having this in mind, we think that this general version of an areawise significance test has great potential to improve the identification of anomalies in time-series analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Calculations have been performed with the help of the Python package pyunicorn [60].

Data accessibility

The Python code used to perform the analyses in this work is publicly available at https://gitlab.pik-potsdam.de/lekscha/awsig and the dataset of tree ring width indices from East Canada [49] is publicly available at https://www.blogs.uni-mainz.de/fb09climatology/e-canada/.

Authors' contributions

J.L. and R.D. designed the research. J.L. performed the numerical experiments and data analyses. J.L. and R.D. discussed the results and wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This work has been financially supported by the German Federal Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF) via the BMBF Young Investigators Group CoSy-CC2 - Complex Systems Approaches to Understanding Causes and Consequences of Past, Present and Future Climate Change (grant no. 01LN1306A) and the Studienstiftung des deutschen Volkes.

References

- 1.Kantz H, Schreiber T. 2004. Nonlinear time series analysis, 2nd edn Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abarbanel HDI, Brown R, Sidorowich JJ, Tsimring LS. 1993. The analysis of observed chaotic data in physical systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 65, 1331–1392. ( 10.1103/RevModPhys.65.1331) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grassberger P, Schreiber T, Schaffrath C. 1991. Nonlinear time sequence analysis. Int. J. Bifurcation Chaos 1, 521–547. ( 10.1142/S0218127491000403) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eckmann JP, Kamphorst S, Ruelle D. 1987. Recurrence plots of dynamical systems. Europhys. Lett. 5, 973–977. ( 10.1209/0295-5075/4/9/004) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marwan N, Romano MC, Thiel M, Kurths J. 2007. Recurrence plots for the analysis of complex systems. Phys. Rep. 438, 237–329. ( 10.1016/j.physrep.2006.11.001) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goswami B, Boers N, Rheinwalt A, Marwan N, Heitzig J, Breitenbach SFM, Kurths J. 2018. Abrupt transitions in time series with uncertainties. Nat. Commun. 9, 48 ( 10.1038/s41467-017-02456-6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao ZK, Small M, Kurths J. 2016. Complex network analysis of time series. Europhys. Lett. 116, 50001 ( 10.1209/0295-5075/116/50001) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao Z, Dang W, Mu C, Yang Y, Li S, Grebogi C. 2018. A novel multiplex network-based sensor information fusion model and its application to industrial multiphase flow system. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 14, 3982–3988. ( 10.1109/TII.2017.2785384) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zou Y, Donner RV, Marwan N, Donges JF, Kurths J. 2019. Complex network approaches to nonlinear time series analysis. Phys. Rep. 787, 1–97. ( 10.1016/j.physrep.2018.10.005) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marwan N, Donges JF, Zou Y, Donner RV, Kurths J. 2009. Complex network approach for recurrence analysis of time series. Phys. Lett. A 373, 4246–4254. ( 10.1016/j.physleta.2009.09.042) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donner RV, Zou Y, Donges JF, Marwan N, Kurths J. 2010. Recurrence networks—a novel paradigm for nonlinear time series analysis. New J. Phys. 12, 033025 ( 10.1088/1367-2630/12/3/033025) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donner RV, Zou Y, Donges JF, Marwan N, Kurths J. 2010. Ambiguities in recurrence-based complex network representations of time series. Phys. Rev. E 81, 015101 ( 10.1103/PhysRevE.81.015101) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donner RV, Donges JF, Zou Y, Feldhoff JH. 2015. Complex network analysis of recurrences. In Recurrence Quantification Analysis (eds C Webber, N Marwan), pp. 101–163. Springer International Publishing.

- 14.Donner RV, Small M, Donges JF, Marwan N, Zou Y, Xiang R, Kurths J. 2011. Recurrence-based time series analysis by means of complex network methods. Int. J. Bifurcation Chaos 21, 1019–1046. ( 10.1142/S0218127411029021) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donner RV, Heitzig J, Donges JF, Zou Y, Marwan N, Kurths J. 2011. The geometry of chaotic dynamics—a complex network perspective. Eur. Phys. J. B 84, 653–672. ( 10.1140/epjb/e2011-10899-1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donges JF, Donner RV, Rehfeld K, Marwan N, Trauth MH, Kurths J. 2011. Identification of dynamical transitions in marine palaeoclimate records by recurrence network analysis. Nonlinear Process. Geophys. 18, 545–562. ( 10.5194/npg-18-545-2011) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donges JF, Donner RV, Trauth MH, Marwan N, Schellnhuber HJ, Kurths J. 2011. Nonlinear detection of paleoclimate-variability transitions possibly related to human evolution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 20 422–20 427. ( 10.1073/pnas.1117052108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donner RV, Stolbova V, Balasis G, Donges JF, Georgiou M, Potirakis SM, Kurths J. 2018. Temporal organization of magnetospheric fluctuations unveiled by recurrence patterns in the Dst index. Chaos 28, 085716 ( 10.1063/1.5024792) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eroglu D, McRobie FH, Ozken I, Stemler T, Wyrwoll KH, Breitenbach SFM, Marwan N, Kurths J. 2016. See-saw relationship of the Holocene East Asian-Australian summer monsoon. Nat. Commun. 7, 12929 ( 10.1038/ncomms12929) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller RGJ. 1981. Simultaneous statistical inference, 2nd edn New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maraun D, Kurths J, Holschneider M. 2007. Nonstationary Gaussian processes in wavelet domain: synthesis, estimation, and significance testing. Phys. Rev. E 75, 016707 ( 10.1103/PhysRevE.75.016707) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Franke JG, Donner RV. 2017. Dynamical anomalies in terrestrial proxies of North Atlantic climate variability during the last 2 ka. Clim. Change 143, 87–100. ( 10.1007/s10584-017-1979-z) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsonis AA, Swanson KL, Roebber PJ. 2006. What do networks have to do with climate? Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 87, 585–596. ( 10.1175/BAMS-87-5-585) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takens F. 1980. Detecting strange attractors in turbulence. In Lecture Notes in Mathematics. pp. 366–381. Springer Science and Business Media.

- 25.Packard NH, Crutchfield JP, Farmer JD, Shaw RS. 1980. Geometry from a time series. Phys. Rev. Lett. 45, 712–716. ( 10.1103/PhysRevLett.45.712) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Casdagli M, Eubank S, Farmer JD, Gibson J. 1991. State space reconstruction in the presence of noise. Physica D 51, 52–98. ( 10.1016/0167-2789(91)90222-U) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Judd K, Mees A. 1998. Embedding as a modeling problem. Physica D 120, 273–286. ( 10.1016/S0167-2789(98)00089-X) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fraser AM, Swinney HL. 1986. Independent coordinates for strange attractors from mutual information. Phys. Rev. A 33, 1134–1140. ( 10.1103/PhysRevA.33.1134) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liebert W, Schuster H. 1989. Proper choice of the time delay for the analysis of chaotic time series. Phys. Lett. A 142, 107–111. ( 10.1016/0375-9601(89)90169-2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kennel MB, Brown R, Abarbanel HDI. 1992. Determining embedding dimension for phase-space reconstruction using a geometrical construction. Phys. Rev. A 45, 3403–3411. ( 10.1103/PhysRevA.45.3403) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gao Z, Yang Y, Fang P, Zou Y, Xia C, Du M. 2015. Multiscale complex network for analyzing experimental multivariate time series. EPL 109, 30005 ( 10.1209/0295-5075/109/30005) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xiang R, Zhang J, Xu X, Small M. 2012. Multiscale characterization of recurrence-based phase space networks constructed from time series. Chaos 22, 013107 ( 10.1063/1.3673789) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen Y, Yang H. 2012. Multiscale recurrence analysis of long-term nonlinear and nonstationary time series. Chaos, Solitons Fractals 45, 978–987. ( 10.1016/j.chaos.2012.03.013) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deng L. 2014. Multi-scale recurrence analysis of complex temporal-spatial system. In Proc. of the 33rd Chinese Control Conf ., pp. 7383–7387.

- 35.Yi G, Wang J, Bian H, Han C, Deng B, Wei X, Li H. 2013. Multi-scale order recurrence quantification analysis of EEG signals evoked by manual acupuncture in healthy subjects. Cogn. Neurodyn. 7, 79–88. ( 10.1007/s11571-012-9221-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yin Y, Shang P. 2016. Multiscale recurrence plot and recurrence quantification analysis for financial time series. Nonlinear Dyn. 85, 2309–2352. ( 10.1007/s11071-016-2830-1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu M, Shang P, Lin A. 2017. Multiscale recurrence quantification analysis of order recurrence plots. Physica A 469, 381–389. ( 10.1016/j.physa.2016.11.058) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gao Z, Li S, Dang W, Yang Y, Do Y, Grebogi C. 2017. Wavelet multiresolution complex network for analyzing multivariate nonlinear time series. Int. J. Bifurcation Chaos 27, 1750123 ( 10.1142/S0218127417501231) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith SW. 2003. Digital signal processing. London, UK: Newnes. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang NE, Shen Z, Long SR, Wu MC, Shih HH, Zheng Q, Yen N, Tung CC, Liu HH. 1998. The empirical mode decomposition and the Hilbert spectrum for nonlinear and non-stationary time series analysis. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 454, 903–995. ( 10.1098/rspa.1998.0193) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Broomhead DS, King GP. 1986. Extracting qualitative dynamics from experimental data. Physica D 20, 217–236. ( 10.1016/0167-2789(86)90031-X) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Elsner JB, Tsonis AA. 1996. In Foundations of SSA, pp. 39–50. Springer US.

- 43.Daubechies I. 1992. Ten lectures on wavelets. Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics.

- 44.Torrence C, Compo GP. 1998. A practical guide to wavelet analysis. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 79, 61–78. ( 10.1175/1520-0477(1998)079[0061:APGTWA]2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Costa M, Goldberger AL, Peng CK. 2005. Multiscale entropy analysis of biological signals. Phys. Rev. E 71, 021906 ( 10.1103/PhysRevE.71.021906) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paluš M. 2018. Linked by dynamics: wavelet-based mutual information rate as a connectivity measure and scale-specific networks. In Advances in Nonlinear Geosciences (ed. A Tsonis), pp. 427–463. Springer International Publishing.

- 47.Wiedermann M, Donges JF, Kurths J, Donner RV. 2017. Mapping and discrimination of networks in the complexity-entropy plane. Phys. Rev. E 96, 042304 ( 10.1103/PhysRevE.96.042304) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rössler O. 1976. An equation for continuous chaos. Phys. Lett. A 57, 397–398. ( 10.1016/0375-9601(76)90101-8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gennaretti F, Arseneault D, Nicault A, Perreault L, Bégin Y. 2014. Volcano-induced regime shifts in millennial tree-ring chronologies from northeastern North America Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 10 077–10 082. ( 10.1073/pnas.1324220111) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Esper J. et al. 2016. Ranking of tree-ring based temperature reconstructions of the past millennium. Quat. Sci. Rev. 145, 134–151. ( 10.1016/j.quascirev.2016.05.009) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Robock A. 2000. Volcanic eruptions and climate. Rev. Geophys. 38, 191–219. ( 10.1029/1998RG000054) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Crowley TJ, Zielinski G, Vinther B, Udisti R, Kreutzs K, Cole-Dai J, Castellano E. 2008. Volcanism and the little ice age. PAGES Newsl. 16, 22–23. ( 10.22498/pages.16.2.22) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miller GH. et al. 2012. Abrupt onset of the Little Ice Age triggered by volcanism and sustained by sea-ice/ocean feedbacks. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L02708 ( 10.1029/2011GL050168) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sigl M. et al. 2015. Timing and climate forcing of volcanic eruptions for the past 2500 years. Nature 523, 543–549. ( 10.1038/nature14565) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schreiber T, Schmitz A. 2000. Surrogate time series. Physica D 142, 346–382. ( 10.1016/S0167-2789(00)00043-9) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schleussner CF, Divine DV, Donges JF, Miettinen A, Donner RV. 2015. Indications for a North Atlantic ocean circulation regime shift at the onset of the little Ice Age. Clim. Dyn. 45, 3623–3633. ( 10.1007/s00382-015-2561-x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Donges JF, Zou Y, Marwan N, Kurths J. 2009. Complex networks in climate dynamics. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 174, 157–179. ( 10.1140/epjst/e2009-01098-2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Radebach A, Donner RV, Runge J, Donges JF, Kurths J. 2013. Disentangling different types of El Niño episodes by evolving climate network analysis. Phys. Rev. E 88, 052807 ( 10.1103/PhysRevE.88.052807) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wiedermann M, Radebach A, Donges JF, Kurths J, Donner RV. 2016. A climate network-based index to discriminate different types of El Niño and La Niña. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 7176–7185. ( 10.1002/2016GL069119) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Donges JF. et al. 2015. Unified functional network and nonlinear time series analysis for complex systems science: the pyunicorn package. Chaos 25, 113101 ( 10.1063/1.4934554) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The Python code used to perform the analyses in this work is publicly available at https://gitlab.pik-potsdam.de/lekscha/awsig and the dataset of tree ring width indices from East Canada [49] is publicly available at https://www.blogs.uni-mainz.de/fb09climatology/e-canada/.