Abstract

Background: Although it is well established that patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are at increased risk of complicating diseases and vaccination-preventable infections, whether gastroenterologists (GIs) or primary care providers (PCPs) assume responsibility for these patients’ health maintenance is not clear.

Methods: We anonymously surveyed a convenience sample of 94 PCPs and 61 GIs at Saint Louis University School of Medicine in St. Louis, MO, about their practice and perception of the health maintenance and vaccination of patients with IBD.

Results: Response rates were 82% and 93% for GIs and PCPs, respectively. GIs were as likely as PCPs to screen for smoking (88% vs 89%) and were significantly less likely to screen for depression/anxiety (24% vs 54%) or to provide pertussis (14% vs 44%) or diphtheria (20% vs 48%) vaccines. GIs were significantly more likely than PCPs to assess for colonoscopy need (94% vs 80%); to screen for nonmelanoma skin cancer (62% vs 14%), melanoma (56% vs 7%), osteoporosis (72% vs 51%), or tuberculosis (94% vs 44%); to prescribe calcium/vitamin D (74% vs 53%); to perform nutritional assessment (78% vs 33%); or to provide hepatitis A (60% vs 39%) or hepatitis B (86% vs 56%) vaccines. GIs were as likely as PCPs (64% vs 75%) to perceive that PCPs should order vaccinations and significantly more likely to perceive that GIs should track vaccinations (58% vs 16%) and other health maintenance issues (90% vs 49%). We found positive associations between performing the various health maintenance and vaccination tasks and the perception of responsibility.

Conclusion: Several health maintenance aspects are inadequately addressed by GIs and PCPs, in part because of conflicting perceptions of responsibility. Clear guidelines and better GI/PCP communication are required to ensure effective health maintenance for patients with IBD.

Keywords: Delivery of health care, inflammatory bowel diseases, risk, vaccination

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a spectrum of diseases that includes Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis.1 Although IBD primarily targets the gastrointestinal tract, it is associated with several extraintestinal manifestations that require timely screening and management.2

Treatment goals for patients with IBD have transitioned from solely symptomatic remission to mucosal and histochemical remission with an increasing use of early and aggressive therapies, including biologic agents and immune modulators.3 Patients with IBD have a dysregulated immune system that puts them at increased risk of complicating illnesses,2 and it is exaggerated by the use of biologic agents and immune modulators. Kantsø et al showed an increased risk of pneumococcal pneumonia in patients with IBD independent of IBD-specific medications.4 In addition, patients with IBD are at increased risk for nutritional deficiencies, osteoporosis, melanoma, nonmelanoma skin cancers, cervical cancer, depression, and anxiety.2 Further, given their immunocompromised status, these patients require special care regarding vaccinations.2

Patients with IBD often receive all their medical care from their gastroenterologist (GI) or an IBD specialist.5 Although several guidelines for health maintenance of patients with IBD have been published,2,6 patients with IBD may not be receiving routine preventive care at the same rate as general medical patients,7 perhaps in part because of ambiguity about whether primary care providers (PCP) or GIs should assume responsibility for these patients’ health maintenance issues.

The aim of this study was to explore the practice and views of PCPs and GIs regarding the health maintenance issues, including vaccinations, of patients with IBD.

METHODS

For this prospective study, we anonymously surveyed a convenience sample of 94 PCPs and 61 GIs who are affiliates or trainees at Saint Louis University School of Medicine in St. Louis, MO, using a paper or an electronic self-administered questionnaire. To maintain anonymity, the electronic responses were delinked from participants’ identifying information, including email address, IP address, and date and time of participation. The paper questionnaires were distributed to participants in group sessions. Participants completed them on their own time, and to maintain anonymity, deposited the completed questionnaires in a drop box. The study was undertaken as a quality improvement project and was exempt from institutional review board approval.

The authors developed the study questionnaire based on the 2017 American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) Clinical Guideline: Preventive Care in Inflammatory Bowel Disease.2 During the development phase, we wanted to ensure that the questionnaire items would be understood by respondents as intended and that we had covered all intended areas of information. We iteratively evaluated the questionnaire by means of focused probing following completion of the questionnaire. In total, 8 respondents were interviewed: 4 during face validity assessment and 4 during pilot testing of the final version (for acceptability, comprehensibility, and response stability after 2-3 days). We added 1 item and reworded 4 items during the face validity assessment phase but did not make any changes during pilot testing.

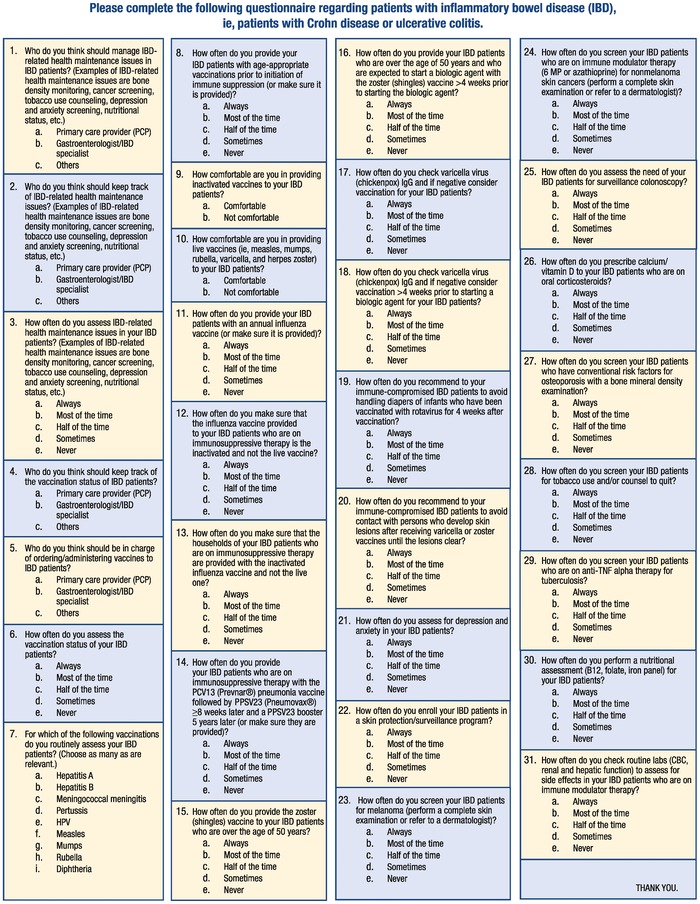

The final questionnaire included 31 questions (Figure). Seventeen questions were related to vaccination, and 14 were related to other health maintenance issues. Questions explored perceived responsibility, frequency of performing various health maintenance tasks, comfort with giving vaccinations, and the vaccines for which patients with IBD should routinely be assessed.

Figure.

Study questionnaire (based on the 2017 American College of Gastroenterology Clinical Guideline: Preventive Care in Inflammatory Bowel Disease2).

For data analysis, we combined the responses “always” and “most of the time.” Data are reported as frequencies (percentages) and were compared using chi-square test. Statistical significance was defined as P≤0.05. Unadjusted 2-tailed P values and 95% confidence intervals are reported.

RESULTS

The response rate was 82% and 93% for GIs and PCPs, respectively. Twenty-four percent of the 50 participant GIs were university faculty, 14% were Veterans Affairs (VA) faculty, 40% were recent GI graduates, and 22% were GI fellows in training. Eleven percent of the 87 participant PCPs were university faculty, 7% were VA faculty, and 82% were medical residents.

Health Maintenance of Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Reported Practice

As shown in Table 1, various health maintenance activities were reportedly performed always/most of the time by 24% (screen for depression/anxiety) to 98% (check routine laboratory investigations in patients on immune modulators) of GIs and by 5% (enroll in a skin protection/surveillance program) to 89% (screen for tobacco use/counsel to quit) of PCPs.

Table 1.

Health Maintenance of Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Reported Practice

| Health Maintenance Task | Gastroenterologists n=50 | Primary Care Providers n=87 | Difference (95% confidence interval) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assess for IBD-related health maintenance issues | 40 (80) | 38 (44) | 36 (19 to 49) | <0.0001 |

| Assess for surveillance colonoscopy | 47 (94) | 70 (80) | 14 (2 to 24) | 0.03 |

| Screen for tobacco use/counsel to quit | 44 (88) | 77 (89) | 1 (−9 to 14) | 0.9 |

| Screen for depression/anxiety | 12 (24) | 47 (54) | 30 (13 to 44) | 0.0007 |

| Screen for melanoma | 28 (56) | 6 (7) | 49 (33 to 62) | <0.0001 |

| Screen for nonmelanoma skin cancers if on immune modulators | 31 (62) | 12 (14) | 48 (32 to 61) | <0.0001 |

| Screen conventional risk patients for osteoporosis | 36 (72) | 44 (51) | 21 (4 to 36) | 0.02 |

| Screen for tuberculosis if on anti–tumor necrosis factor alpha | 47 (94) | 38 (44) | 50 (35 to 61) | <0.0001 |

| Enroll in a skin protection/surveillance program | 32 (64) | 4 (5) | 59 (44 to 71) | <0.0001 |

| Prescribe calcium/vitamin D if on corticosteroids | 37 (74) | 46 (53) | 21 (4 to 36) | 0.02 |

| Perform routine nutritional assessment | 39 (78) | 29 (33) | 45 (28 to 58) | <0.0001 |

| Check routine laboratory investigations if on immune modulators | 49 (98) | 57 (66) | 32 (20 to 43) | <0.0001 |

Notes: Data are reported as number (%) of respondents who answered “always” or “most of the time.” The Difference column reports the difference in percentage points. P values are 2-sided.

No significant difference was found between the 2 groups in reported screening for smoking/counseling to quit. PCPs were more likely to report always/most of the time assessing for depression/anxiety (P=0.0007). However, GIs were more likely to report always/most of the time assessing for IBD-related health maintenance issues (P<0.0001), enrolling patients in skin protection/surveillance programs (P<0.0001), screening for melanoma (P<0.0001), screening for nonmelanoma skin cancers when patients are on immune modulators (P<0.0001), assessing the need for surveillance colonoscopy (P=0.03), prescribing calcium/vitamin D to patients on oral corticosteroids (P=0.02), screening for osteoporosis by bone mineral density measurement (P=0.02), screening patients on anti–tumor necrosis factor therapy for tuberculosis (P<0.0001), performing routine nutritional assessments (P<0.0001), and checking routine laboratory investigations for patients taking immune modulators (P<0.0001).

Vaccinations of Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Reported Practice

As shown in Table 2, various vaccination-related tasks were reportedly performed always/most of the time by 10% (warn immune-compromised patients against handling diapers of rotavirus-vaccinated infants for a period of 4 weeks) to 86% (assess for hepatitis-B vaccine) of GIs and by 6% (warn immune-compromised patients against handling diapers of rotavirus-vaccinated infants for a period of 4 weeks) to 91% (provide annual influenza vaccine) of PCPs. No significant differences were found between the 2 groups in assessing vaccination status or in vaccination treatment plans for influenza, varicella/zoster, meningococcal, human papilloma virus, measles-mumps-rubella, and exposure to rotavirus.

Table 2.

Vaccination of Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Reported Practice

| Vaccination Task | Gastroenterologists n=50 | Primary Care Providers n=87 | Difference (95% confidence interval) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Check varicella immunoglobulin G and vaccinate accordingly | 7 (14) | 6 (7) | 7 (−3 to 20) | 0.9 |

| Check varicella immunoglobulin G >4 weeks prior to starting biologics and vaccinate accordingly | 7 (14) | 7 (8) | 6 (−4 to 19) | 0.3 |

| Select inactivated influenza vaccine if on immune-suppressive therapy | 33 (66) | 73 (84) | 18 (3 to 33) | 0.02 |

| Select inactivated influenza vaccine for households if patient on immune-suppressive therapy | 11 (22) | 14 (16) | 6 (−7 to 21) | 0.4 |

| Warn immune-compromised patients against handling diapers of rotavirus-vaccinated infants for 4 weeks | 5 (10) | 5 (6) | 4 (−5 to 16) | 0.4 |

| Warn immune-compromised patients against contact with varicella/zoster-vaccinated persons with skin lesions | 18 (36) | 24 (28) | 8 (−8 to 24) | 0.3 |

| Provide zoster vaccine if age ≥50 years | 14 (28) | 34 (39) | 11 (−6 to 26) | 0.2 |

| Provide zoster vaccine >4 weeks before starting biologics if age ≥50 years | 13 (26) | 19 (22) | 4 (−10 to 19) | 0.6 |

| Provide annual influenza vaccine | 43 (86) | 79 (91) | 5 (6 to 18) | 0.4 |

| Provide age-appropriate vaccinations prior to immune-suppressive therapy | 35 (70) | 44 (51%) | 19 (2 to 34) | 0.03 |

| Provide appropriate pneumonia vaccine if on immune-suppressive therapya | 18 (36) | 54 (62) | 26 (9 to 41) | 0.004 |

| Assess vaccination status in general | 35 (70) | 53 (61) | 9 (−8 to 24) | 0.3 |

| Assess for hepatitis-A vaccine | 30 (60) | 34 (39) | 21 (4 to 37) | 0.02 |

| Assess for hepatitis-B vaccine | 43 (86) | 49 (56) | 30 (14 to 43) | 0.0003 |

| Assess for pertussis vaccine | 7 (14) | 38 (44) | 30 (14 to 43) | 0.0003 |

| Assess for diphtheria vaccine | 10 (20) | 42 (48) | 28 (11 to 42) | 0.001 |

| Assess for meningococcal vaccine | 13 (26) | 24 (28) | 2 (−14 to 16) | 0.8 |

| Assess for human papilloma vaccine | 14 (28) | 18 (21) | 7 (−7 to 22) | 0.4 |

| Assess for measles vaccine | 11 (22) | 25 (29) | 7 (−9 to 21) | 0.4 |

| Assess for mumps vaccine | 11 (22) | 25 (29) | 7 (−9 to 21) | 0.4 |

| Assess for rubella vaccine | 11 (22) | 25 (29) | 7 (−9 to 21) | 0.4 |

aProvide pneumonia vaccination with PCV13 (Prevnar), followed by PPSV23 (Pneumovax) ≥8 weeks later, followed by PPSV23 booster after 5 years.

Notes: Data are reported as number (%) of respondents who answered “always” or “most of the time” or who routinely assessed for the listed vaccines. The Difference column reports the difference in percentage points. P values are 2-sided.

PCPs were more likely to report assessing for pertussis (P=0.0003) and diphtheria (P=0.001) vaccines, selecting inactivated influenza vaccine if the patient was on immune-suppressive therapy (P=0.02), and providing immune-suppressed patients with a pneumococcal conjugated vaccine (PCV13 or Prevnar 13), followed by a pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23 or Pneumovax) ≥8 weeks later and a booster every 5 years (P=0.004). However, GIs were more likely to report assessing for hepatitis A (P=0.02) and hepatitis B (P=0.0003) vaccines and providing age-appropriate vaccinations prior to initiation of immune-suppressive therapy (P=0.03).

Health Maintenance of Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Perceived Responsibility

Large and significant differences were found in perceived responsibility for health maintenance issues of patients with IBD between the 2 groups (Table 3). Overall, questionnaire respondents perceived that GIs, not PCPs, should both manage (P<0.0001) and track (P<0.0001) IBD-related health maintenance issues.

Table 3.

Health Maintenance of Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): Perceived Responsibility

| Gastroenterologists | Primary Care | Difference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Responsible Practitioner/Task | n=50 | Providers n=87 | (95% confidence interval) | P Value |

| Gastroenterologists should manage IBD-related health maintenance issues | 47 (94) | 45 (52) | 42 (28 to 53) | <0.0001 |

| Primary care providers should manage IBD-related health maintenance issues | 2 (4) | 41 (47) | 37 (23 to 47) | <0.0001 |

| Gastroenterologists should keep track of IBD-related health maintenance issues | 45 (90) | 43 (49) | 41 (26 to 53) | <0.0001 |

| Primary care providers should keep track of IBD-related health maintenance issues | 2 (4) | 41 (47) | 43 (29 to 54) | <0.0001 |

Notes: Data are reported as number (%) of respondents. Respondents who perceived the responsibility to be that of other practitioners were excluded. The Difference column reports the difference in percentage points. P values are 2-sided.

Vaccinations of Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Perceived Responsibility

Although most GIs (64%) and PCPs (75%) had the perception that PCPs should order/administer vaccines with no significant difference between the 2 groups (Table 4), the groups were comfortable to similar degrees in providing inactivated (92% of GIs and 84% of PCPs) and live attenuated (58% of GIs and 56% of PCPs) vaccines.

Table 4.

Vaccination of Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Perceived Responsibility and Comfort in Giving Inactivated and Live Attenuated Vaccines

| Responsible Practitioner/Task/Comfort | Gastroenterologists n=50 | Primary Care Providers n=87 | Difference (95% confidence interval) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastroenterologists should order/administer vaccines | 17 (34) | 20 (23) | 11 (–4 to 27) | 0.2 |

| Primary care providers should order/administer vaccines | 32 (64) | 65 (75) | 11 (–5 to 27) | 0.2 |

| Gastroenterologists should keep track of vaccination status | 29 (58) | 14 (16) | 42 (25 to 56) | <0.0001 |

| Primary care providers should keep track of vaccination status | 19 (38) | 71 (82) | 44 (27 to 58) | <0.0001 |

| Comfortable providing inactivated vaccines | 46 (92) | 73 (84) | 8 (–5 to 18) | 0.9 |

| Comfortable providing live attenuated vaccinesa | 29 (58) | 49 (56) | 2 (–15 to 18) | 0.8 |

aMeasles-mumps-rubella, varicella, and herpes zoster.

Notes: Data are reported as number (%) of respondents. Respondents who perceived the responsibility to be that of other practitioners were excluded. The Difference column reports the difference in percentage points. P values are 2-sided.

However, as shown in Table 4, GIs were less likely to perceive that PCPs should keep track of vaccination status (P<0.0001) and more likely to perceive that GIs should keep track of vaccination status (P<0.0001).

Association Between Reported Practice and Perception of Responsibility for Health Maintenance and Vaccinations of Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease

To explore the association between practice and perceived responsibility, we divided the GIs and PCPs into subgroups according to their reported practice (task assessed always/most of the time vs half of the time/sometimes/never) and perception of responsibility (GI responsibility vs PCP responsibility) in regard to managing IBD-related health maintenance issues, tracking IBD-related health maintenance issues, ordering vaccines, and tracking vaccination status (ie, crossing question 3 with questions 1 and 2 and crossing question 6 with questions 4 and 5; refer to the Figure).

All associations were positive; ie, tasks were reportedly assessed always/most of the time more often when either group perceived them as their responsibility. Further, the results were significant in all 4 associations for PCPs and in 1 of the 4 associations for GIs (Table 5).

Table 5.

Association Between Reported Practice and Perception of Responsibility for Health Maintenance and Vaccinations

| Task Assessed Always/ | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Most of the Time | |||

| Task/Respondent/Response | Yes | No | P Value |

| Managing IBD-related health maintenance issues | |||

| GI respondents | 0.34 | ||

| GIs are responsible | 38 | 9 | |

| PCPs are responsible | 1 | 1 | |

| PCP respondents | <0.0001 | ||

| GIs are responsible | 5 | 40 | |

| PCPs are responsible | 33 | 8 | |

| Tracking IBD-related health maintenance issues | |||

| GIs respondents | 0.38 | ||

| GIs are responsible | 36 | 9 | |

| PCPs are responsible | 1 | 1 | |

| PCP respondents | <0.0001 | ||

| GIs are responsible | 2 | 41 | |

| PCPs are responsible | 35 | 6 | |

| Ordering vaccinations | |||

| GI respondents | 0.74 | ||

| GIs are responsible | 13 | 4 | |

| PCPs are responsible | 22 | 10 | |

| PCP respondents | <0.0001 | ||

| GIs are responsible | 3 | 17 | |

| PCPs are responsible | 48 | 17 | |

| Tracking vaccination status | |||

| GI respondents | 0.01 | ||

| GIs are responsible | 24 | 5 | |

| PCPs are responsible | 9 | 10 | |

| PCP respondents | 0.006 | ||

| GIs are responsible | 4 | 10 | |

| PCPs are responsible | 49 | 22 | |

Notes: Data are presented as number of respondents. Respondents who perceived the responsibility to be that of other practitioners were excluded. P values are 2-sided. GIs, gastroenterologists; PCPs, primary care providers.

DISCUSSION

In our survey of the practice and views of university hospital–affiliated PCPs and GIs regarding health maintenance issues and vaccinations for patients with IBD, we found that 72% to 98% of GIs always/most of the time performed the recommended individual health maintenance tasks except for skin cancer surveillance and depression/anxiety screening that were reportedly performed by less than two-thirds and less than one-fourth of respondents, respectively. PCP performance was similar to GI performance in tobacco use, better in depression/anxiety screening, but worse otherwise. In contrast, except for hepatitis A, hepatitis B, influenza vaccines (providing annual influenza vaccine in general and selecting inactivated influenza vaccine for patients on immunosuppression), and providing age-appropriate vaccines prior to immunosuppression, <50% of GIs (10%-36%) followed vaccination recommendations always or most of the time. Similarly, except for hepatitis B, influenza vaccines (providing annual influenza vaccines in general and selecting inactivated influenza vaccine for patients on immunosuppression), providing age-appropriate vaccines prior to immunosuppression, and providing appropriate pneumonia vaccine while on immunosuppression, <50% of PCPs (6%-48%) followed vaccination recommendations always or most of the time. Although most GIs and PCPs were reportedly comfortable providing inactivated vaccines, only 58% and 56%, respectively, were comfortable providing live attenuated vaccines. Twenty-three percent and 52% of PCPs had the perception that GIs rather than PCPs are responsible for vaccination and IBD-related health maintenance, respectively. In contrast, 4%, 38%, and 64% of GIs perceived that PCPs are responsible for IBD-related health maintenance, keeping track of vaccination status, and administering vaccines, respectively. Finally, the reported adherence to recommendations was positively associated with the perception of responsibility in both groups.

Overall, the GIs’ reported performance of health maintenance tasks in our study is acceptable (72%-98%), except for skin cancer surveillance (56%-64%) and depression/anxiety screening (24%). Patients with IBD are at increased risk for developing melanoma,8 and the risk is nearly double in the setting of anti–tumor necrosis factor therapy.9,10 IBD is not an independent risk factor for the development of nonmelanoma skin cancer; however, the risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer is increased with the use of thiopurines.11 The ACG recommends that all patients with IBD be counseled to decrease sun exposure by wearing protective clothing and using sunscreens with a sun protection factor of at least 30 and to undergo routine melanoma screening. In addition, patients with IBD who are taking immune modulators should be screened for nonmelanoma skin cancer, particularly patients who are >50 years of age.2

Bhandari et al found that patients with IBD were nearly twice as likely (49% vs 23%) to report depressive symptoms compared to patients without IBD, and IBD was a predictor of depressive symptoms.12 A systematic review found anxiety in 19% of patients with IBD compared to 10% of the background population and depression in 21% of patients with IBD compared to 13% in non-IBD controls.13 Depression rates as measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale were similar in both active and inactive disease groups.13 Nigro et al found that the presence of depression or other psychiatric disorders in patients with IBD was significantly associated with medication noncompliance.14 As a conditional recommendation with low-level evidence, the ACG recommends screening patients with IBD for depression and anxiety.2

In contrast to their performance of health maintenance tasks, we found the GIs’ reported performance of vaccination tasks to be poor overall. This finding is consistent with the results of a study showing that only 28% and 9% of 146 patients with IBD who were on current or previous immunosuppression received yearly influenza and pneumococcal vaccines, respectively.15 In another study, only 12% of 2,076 patients with IBD were vaccinated against hepatitis B virus,16 a rate much lower than the 86% reported assessment rate for hepatitis B vaccination in our study. Patients with IBD are at increased risk for preventable infections, so adherence to age-appropriate vaccination schedules is strongly recommended.2,15 In accordance with national guidelines, regardless of immunosuppression status, all adult patients with IBD should receive non-live vaccines,2,17-21 including trivalent inactivated influenza, pneumococcal (PCV13 and PPSV23), hepatitis A, hepatitis B, haemophilus influenzae B, human papilloma virus, tetanus, and pertussis vaccines. On the other hand, the live attenuated vaccines for patients with IBD have important restrictions.2,22 Per the Infectious Disease Society of America and current ACG guidelines, varicella and herpes zoster vaccines are recommended for patients with IBD who are on low level but not high level immunosuppression.2,17 The ACG defines patients on low level immunosuppression as those with significant protein calorie malnutrition or those receiving (or who received in the previous 3 months) systemic corticosteroids equivalent to 20 mg prednisone/day for ≥14 days, methotrexate ≤0.4 mg/kg/week, azathioprine ≤3.0 mg/kg/day, or 6-mercaptopurine ≤1.5 mg/kg/day.2 On the other hand, the guidelines strongly suggest that varicella and herpes zoster vaccines be avoided in patients who have been on high-dose immunosuppressive therapy within the past 3 months or in patients who plan to start high-dose immunosuppressive therapy within the next 6 weeks.2,22 Although administering varicella or herpes zoster vaccines to household members of immunosuppressed patients is not contraindicated, if vaccine recipients develop a postvaccination rash, immunosuppressed patients should maintain contact precautions until rash resolution.2,17 The measles-mumps-rubella vaccine is contraindicated for patients who are receiving, who received in the previous 3 months, or who plan to receive within 6 weeks any immunosuppressive therapy.2

Potential reasons of noncompliance with guidelines include guideline unawareness, discomfort in performing unfamiliar tasks such as administering live vaccines to immune-suppressed patients, inadequate communication, and conflicting perceptions of responsibility among healthcare providers. One study demonstrated poor knowledge among 108 GIs about which vaccines to recommend to patients with IBD.23 Despite almost unanimously perceiving that they are responsible for managing IBD-related health maintenance issues, GIs were not compliant with skin cancer surveillance and depression/anxiety screening, suggesting inadequate guideline awareness.

In our study, PCPs outperformed GIs in tasks more related to primary care (such as screening for depression and anxiety and providing pneumonia, pertussis, and diphtheria vaccines), and GIs outperformed PCPs in tasks more specific to IBD and its management or to their subspecialty (such as screening for tuberculosis in patients on immune modulators and for osteoporosis in patients on oral corticosteroids and assessing for hepatitis A and hepatitis B vaccines). We also found a low comfort rate in providing live vaccines in association with a very low assessment rate for measles-mumps-rubella and varicella vaccination. Together, the data suggest that adherence to guidelines may be related to familiarity with the tasks. In this vein, Selby et al found that only 29% of family physicians were comfortable making vaccination recommendations for their patients with IBD.24

Alternatively, noncompliance with the guidelines may be attributable to conflicting perceptions of responsibility for the various health maintenance tasks among healthcare providers. This idea is supported by the association between adherence to recommendations and the perception of responsibility among PCPs and, to some extent, among GIs that was observed in the current study. For vaccines that are given in series, GIs may think that traveling to their specialist's office could be cumbersome for patients and because patients visit their PCPs more frequently, the PCP's office may be more suitable for managing such vaccinations. On the other hand, PCPs may have concerns about the complexity of managing patients with IBD, especially when disease activity is not under control or new medications are being started or titrated, and therefore may think the GI's office may be more suitable for vaccination management.

Several measures have been shown to improve vaccination rates in patients with IBD, including the availability of vaccines in the GI's office, education of healthcare professionals,25-27 and using checklists.28

Limitations

Limitations of this study include the relatively small sample size and sampling being restricted to affiliates of one university hospital. All 137 respondents were involved in training trainees from Saint Louis University School of Medicine or practiced/completed their training at Saint Louis University School of Medicine in either internal medicine or gastroenterology. In addition, many PCP respondents were current trainees. Thus, our results may not apply to other settings, as a lack of knowledge may have contributed to the results this setting. Also, we examined questionnaires rather than actual practice, and survey responses have an inherent, self-serving bias. However, such bias would be expected to strengthen rather than weaken the main conclusions of the study.

CONCLUSION

We conclude that several health maintenance aspects for patients with IBD are inadequately addressed by GIs and PCPs, perhaps attributable in part to conflicting perceptions of responsibility. Guidelines that not only recommend tasks to be performed but also which party should perform the tasks may be required. In addition, better dissemination of guidelines and better GI/PCP communication and coordination, such as sharing medical documentation and using electronic alerts, are required for effective health maintenance in patients with IBD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors have no financial or proprietary interest in the subject matter of this article. Portions of the manuscript have been presented as abstracts at the following meetings: American College of Gastroenterology, Orlando, FL, October 2017; Advances in Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Orlando, FL, November 2017; and Crohn's and Colitis Congress, Las Vegas, NV, January 2018.

This article meets the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and the American Board of Medical Specialties Maintenance of Certification competencies for Patient Care, Medical Knowledge, Interpersonal and Communication Skills, and Practice-Based Learning and Improvement.

REFERENCES

- 1.Talley NJ, Abreu MT, Achkar JP, et al. . An evidence-based systematic review on medical therapies for inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011. April;106 Suppl 1:S2-25; quiz S26. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farraye FA, Melmed GY, Lichtenstein GR, Kane SV. ACG clinical guideline: preventive care in inflammatory bowel disease. Am Gastroenterol. 2017. February;112(2):241-258. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levesque BG, Sandborn WJ, Ruel J, Feagan BG, Sands BE, Colombel JF. Converging goals of treatment of inflammatory bowel disease from clinical trials and practice. Gastroenterology. 2015. January;148(1):37-51. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kantsø B, Simonsen J, Hoffmann S, Valentiner-Branth P, Petersen AM, Jess T. Inflammatory bowel disease patients are at increased risk of invasive pneumococcal disease: a nationwide Danish cohort study 1977-2013. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015. November;110(11):1582-1587. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kane SV. Health maintenance assessment for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2017. August;13(8):500-503. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reich J, Wasan S, Farraye FA. Vaccinating patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2016. September;12(9):540-546. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Selby L, Kane S, Wilson J, et al. . Receipt of preventive health services by IBD patients is significantly lower than by primary care patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008. February;14(2):253-258. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh S, Nagpal SJ, Murad MH, et al. . Inflammatory bowel disease is associated with an increased risk of melanoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014. February;12(2):210-218. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Long MD, Martin CF, Pipkin CA, Herfarth HH, Sandler RS, Kappelman MD. Risk of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2012. August;143(2):390-399.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McKenna MR, Stobaugh DJ, Deepak P. Melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer in inflammatory bowel disease patients following tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor monotherapy and in combination with thiopurines: analysis of the Food and Drug Administration adverse event reporting system. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2014. September;23(3):267-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ariyaratnam J, Subramanian V.. Association between thiopurine use and nonmelanoma skin cancers in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014. February;109(2):163-169. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhandari S, Larson ME, Kumar N, Stein D. Association of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) with depressive symptoms in the United States population and independent predictors of depressive symptoms in an IBD population: a NHANES study. Gut Liver. 2017. Jul 15;11(4):512-519. doi: 10.5009/gnl16347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mikocka-Walus A, Knowles SR, Keefer L, et al. . Controversies revisited: a systematic review of the comorbidity of depression and anxiety with inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016. March;22(3):752-762. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nigro G, Angelini G, Grosso SB, Caula G, Sategna-Guidetti C. Psychiatric predictors of noncompliance in inflammatory bowel disease: psychiatry and compliance. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001. January;32(1):66-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Melmed GY, Ippoliti AF, Papadakis KA, et al. . Patients with inflammatory bowel disease are at risk for vaccine-preventable illnesses. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006. August;101(8):1834-1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loras C, Saro C, Gonzalez-Huix F, et al. . Prevalence and factors related to hepatitis B and C in inflammatory bowel disease patients in Spain: a nationwide, multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009. January;104(1):57-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rubin LG, Levin MJ, Ljungman P, et al. . IDSA clinical practice guideline for vaccination of the immunocompromised host. Clin Infect Dis. 2014. February;58(3):e44-e100. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sands BE, Cuffari C, Katz J, et al. . Guidelines for immunizations in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004. September;10(5):677-692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Long MD, Gulati A, Wohl D, Herfarth H. Immunizations in pediatric and adult patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a practical case-based approach. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015. August;21(8):1993-2003. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim DK, Bridges CB, Harriman KH; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP); ACIP Adult Immunization Work Group. Advisory committee on immunization practices recommended immunization schedule for adults aged 19 years or older–United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015. Feb 6;64(4):91-92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim DK, Bridges CB, Harriman KH; Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Advisory committee on immunization practices recommended immunization schedule for adults aged 19 years or older: United States, 2016. Ann Intern Med. 2016. Feb 2;164(3):184-194. doi: 10.7326/M15-3005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reich J, Wasan SK, Farraye FA. Vaccination and health maintenance issues to consider in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2017. December;13(12):717-724. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wasan SK, Coukos JA, Farraye FA. Vaccinating the inflammatory bowel disease patient: deficiencies in gastroenterologists knowledge. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011. December;17(12):2536-2540. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Selby L, Hoellein A, Wilson JF. Are primary care providers uncomfortable providing routine preventive care for inflammatory bowel disease patients? Dig Dis Sci. 2011. March;56(3):819-824. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1329-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parker S, Chambers WL, Spangler C, et al. . A quality improvement project significantly increased the vaccination rate for immunosuppressed patients with IBD. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013. August;19(9):1809-1814. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e31828c8512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reich JS, Miller HL, Wasan SK, et al. . Influenza and pneumococcal vaccination rates in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2015. June;11(6):396-401. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Christensen KR, Steenholdt C, Buhl SS, et al. . Systematic information to health-care professionals about vaccination guidelines improves adherence in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in anti-TNF alpha therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015. November;110(11):1526-1532. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Health maintenance checklist for adult IBD patients. Crohn's & Colitis Foundation. www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/science-and-professionals/programs-materials/health-maintenance-checklist.pdf. Accessed September 1, 2018.