Abstract

This study investigated the effects of supplementing late gestation sow diets with processed or unprocessed oat or wheat straw on physiology, early lactation feed intake, and offspring performance. One hundred fifty gestating sows were randomly assigned to 1 of 5 dietary treatments (30 sows per diet) from day 86 of gestation until farrowing. Treatments, arranged as a 2 × 2 factorial plus a control, were a standard gestation diet (control) or control supplemented with 10% wheat or oat straw, processed or unprocessed. Sows were fed a standard lactation diet postfarrowing. The processed straws were produced by high-pressure compaction at 80 °C. On day 101 of gestation (day 15 of the trial), blood samples were collected from a subset of sows (n = 8 per treatment) through ear vein catheters and analyzed for insulin, insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), prolactin, glucose, and urea concentrations. Fecal samples were collected on days 103 to 104 of gestation to determine nutrient digestibility, and feeding motivation was investigated on day 104. Litter characteristics and sow feed intake were recorded for 7 d postfarrowing. Three piglets per litter were selected at weaning, fed standard diets, and followed to market. Treatment had no effect on feeding motivation, piglet characteristics at birth, estimated milk production, and offspring BW at market or carcass quality. Processed straw improved DM digestibility and energy content and the effect was greater with oat straw (straw × processing effect, P < 0.05). Pre- and postprandial glucose concentrations tended to decrease (P < 0.10) with processing of wheat, but not oat straw, and this effect was more apparent in the preprandial samples. Preprandial prolactin concentration increased with oat but decreased with wheat straw, whereas postprandial IGF-1 and prolactin concentration increased with processing of wheat, but not oat straw (straw × processing, P < 0.05). Sow lactation feed intake improved (P < 0.05) with oat straw supplementation relative to wheat straw. Piglet weaning weight increased (P < 0.05) with oat straw supplementation and processing improved (P < 0.05) nursery exit BW. However, straw supplementation, regardless of processing, had no effect on offspring BW at market or carcass quality. Overall, oat straw supplementation had a greater impact on sow physiology and provided benefits for sows in late gestation, and there was some indication that further benefits could be obtained through mild processing.

Keywords: gestating sows, lactation feed intake, piglet growth, sow physiology, straw, swine

INTRODUCTION

Pregnant sows are limit-fed to prevent excessive weight gain and the associated negative consequences on locomotion, farrowing, and feed intake postfarrowing (Ramonet et al., 2000; Meunier-Salaün et al., 2001). Restricted feeding, however, may lead to aggression and stereotypies, which have negative impacts on welfare and production. Although responses are inconsistent, there is some evidence that feeding fiber-rich diets to pregnant sows prolongs satiety reduces the behavioral problems associated with restricted feeding (Meunier-Salaün et al., 2001; de Leeuw et al., 2004), and improves sow and litter performance during lactation (Reese, 1997; Veum et al., 2009). Although the inconsistencies could be related to differences in housing conditions and feeding strategies, they are more likely due to differences in fiber inclusion rate and composition, specifically the proportion of soluble or insoluble fiber (Grieshop et al. 2001; Meunier-Salaün and Bolhuis, 2015).

Sows offered diets rich in fermentable fiber had an extended feeding time, delayed glucose and nutrient absorption, spent less time standing (Ramonet et al., 2000; de Leeuw et al., 2004), and showed reduced aggression (Danielsen et al., 2001) compared with sows fed a diet based on poorly fermentable mixed fiber. However, most of the fiber-rich ingredients available for use in gestating sow diets are high in insoluble and poorly fermentable fiber. There is evidence that processing fiber by either particle size reduction or hydrothermal methods improves the fermentability and utilization of insoluble fiber in pigs due to the reduction in fiber length and disruption of the cell (de Vries et al., 2012). However, it is not clear if fiber source affects the performance response to processing and whether changes associated with processed fiber intake in gestating sows are favorable for sow physiology and piglet development. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to determine the impact of supplementing gestation diets with processed wheat or oat straw on 1) the physiology of group-housed sows and early lactation feed intake; and 2) offspring body weight, growth, and carcass quality.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The experiment was conducted at the Prairie Swine Centre, Inc., Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada. The experimental protocol and procedures involving animals were approved by the University of Saskatchewan’s Animal Research Ethics Board for adherence to the Canadian Council on Animal Care guidelines for humane animal use (CCAC, 2009).

Dietary Treatments

Sows were assigned to 1 of 5 dietary treatments, arranged as a 2 × 2 factorial plus a control (a standard gestation diet) or the control supplemented with processed (Proc) or unprocessed (Unproc) oat or wheat straw at 10% of the daily feed allowance (as-fed basis). A preliminary trial had shown that this level of supplementation resulted in minimal refusals. Straw was obtained from the University of Saskatchewan Rayner Dairy Research and Teaching Facility and ground using a tub grinder. The straws were further ground to pass through a 6-mm screen using a hammer mill (HMS.20x; Colorado milling, Cañon City, CO) The processed straws were produced by hydraulically compressing straw through a briquette maker (model BP-100; Biomass Briquette Systems, LLC, Chico, CA) at a temperature of approximately 80 °C. The standard gestation diet (Table 1) was formulated to meet or exceed nutrient specifications for gestating sows (NRC, 2012). Celite (0.4%; Celite Corporation, Lompoc, CA) was added to a portion of the gestation diet as a source of acid-insoluble ash (AIA) and used as an indigestible marker for determination of dry matter (DM) and energy digestibility.

Table 1.

Ingredient and chemical composition of the gestation and lactation diets

| Ingredient | Gestation | Lactation |

|---|---|---|

| Barley | 68.3 | 15.0 |

| Corn | – | 26.2 |

| Wheat | – | 21.2 |

| Corn DDGS | 10.0 | 10.0 |

| Wheat Shorts | 10.0 | – |

| Soybean meal, 45% CP | – | 7.5 |

| Faba beans | 7.6 | 15.0 |

| Canola oil | 0.30 | 1.30 |

| Salt | 0.45 | 0.47 |

| Limestone | 1.67 | 1.61 |

| Monocalcium phosphate | 0.765 | 0.845 |

| Vitamin-mineral premix1 | 0.150 | 0.150 |

| L-Lysine HCl | 0.200 | 0.400 |

| DL-Methionine | 0.025 | 0.074 |

| L-Threonine | 0.079 | 0.126 |

| L-Tryptophan | – | 0.023 |

| Choline chloride | 0.08 | 0.08 |

| Celite2 | 0.40 | – |

| Calculated chemical composition | ||

| NE, Mcal/kg | 2.25 | 2.40 |

| CP, % | 13.5 | 16.9 |

| Calcium, % | 0.85 | 0.85 |

| Available P, % | 0.45 | 0.45 |

| SID Lys3, % | 0.55 | 0.90 |

| SID Met3, % | 0.19 | 0.28 |

| SID Thr3, % | 0.42 | 0.58 |

| SID Trp3, % | 0.11 | 0.15 |

1Supplied per kilogram of the diet; Zn, 100 mg as zinc sulfate; Fe, 80 mg as ferrous sulfate; Cu, 50 mg as copper sulfate; Mn, 25 mg as manganous sulfate; I, 0.50 mg as calcium iodate; and Se, 0.10 mg as sodium selenite. Vitamin mix provided (per kg of diet): vitamin A, 8250 IU; vitamin D, 825 IU; vitamin E, 40 IU; niacin, 35 mg; D-pantothenic acid, 15 mg; menadione, 4 mg; folacin, 2 mg; thiamine, 1 mg; D-biotin, 0.2 mg; and vitamin B12, 25 mg.

2Celite 545, Celite Corporation, Lompoc CA, USA.

3SID = standardized ileal digestible.

Animals and Housing

A total of 150 gestating sows (Camborough Plus females × C337 sires; PIC, Winnipeg, MB, Canada) were placed on trial over 15 blocks at 86 ± 2 d of gestation (236.7 ± 32.4 kg BW; parity 0–5; backfat thickness, 16–24 mm) with 10 sows per block (each block, n = 2 per treatment). Backfat thickness was measured ultrasonically (iMAGO.S 1411ms51; Echo Control Medical, Angoulême, France) by scanning the right side of each sow longitudinally between the 10th and last rib, 5 cm lateral to the dorsal midline.

Sows were assigned to the diets such that parity, initial BW, and backfat thickness were comparable among treatments. The gestation facility consisted of a free access stall system (INN-O-STALL free access stall; Egebjerg International, Egeberg, Denmark) with 6 group pens; each with 32 individual, free access stalls. Each stall (equipped with a feeder and a nipple drinker) measured 0.66 × 2.10 m (front 1.50 m solid floor, back 0.60 m slatted) providing 2.2 m2 per sow. Sows were allowed to leave their stalls after feeding to be in a group setting, mixing with sows from various treatments and those not included in the experiment.

On day 110 of gestation, sows were transferred from the gestation facility to a farrowing room. Each farrowing room was equipped with 16 individual farrowing crates (INN-O-CRATE farrowing crate; Egebjerg International, Egeberg, Denmark). Each crate measured 1.83 × 2.44 m and had an adjustable sow space and piglet area on the side of the crate. The piglet area measured 0.90 × 0.90 m and contained an easy access hood, rubber mats, and a heat lamp. Individual bowl feeders and nipple drinkers were located at the front of each sow space. Temperature was maintained according to the thermoneutral zone for the specific age and reproduction stage (Zhang et al., 1994).

Feeding and Experimental Procedures

Sows were fed the gestation treatment diets once daily at 0700 h from day 86 ± 2 of gestation until farrowing. During feeding, with the exception of sows on the control treatment, sows were fed their respective treatment straw at 10% of daily feed allowance, which was 2.3 kg from days 86 to 110 of gestation and 3.0 kg from day 110 until farrowing. The daily allowance of processed straw was weighed and soaked in water (1:1, wt:wt) overnight before adding as a top-dress to the gestation diet.

From days 100 to 104 ± 2 of gestation, 1 sow per treatment (i.e., 5 sows per block) were randomly selected and locked in their gestation stalls for serial blood sampling (n = 8 per treatment) and determination of fecal energy digestibility (n = 10 per treatment). Thus, sows for blood and fecal sampling were selected from 10 out of the 15 blocks. On days 100 ± 2, a catheter (0.034 in i.d. and 0.050 in o.d.; Polyethylene tubing, Instech Laboratories, Inc., PA) was inserted into the ear vein of the sows according to a procedure modified from Niiyama et al. (1985). Briefly, the catheter was introduced into the ear vein through a 14-gauge needle. Patency was confirmed by flushing the catheter with physiological saline (9 g NaCl/L) and the catheter adaptor (made from a blunt-edge syringe needle) was capped with an injection port and filled with heparinized saline (10 IU/mL heparin). Thereafter, the catheter was placed in a plastic bag and secured onto the ear of the sow using an adhesive bandage (Tensoplast; BSN Medical, Laval, QC, Canada). On the following day, serial blood samples were collected via the ear vein catheters at −5 min before feeding and at 30, 60, 90, 120, 180, 240, 300, and 360 min postfeeding. The blood samples (10 mL) were collected into heparinized and nonheparinized tubes. Catheters were flushed and filled with 5 mL of 10 IU/mL heparinized saline to prevent clotting between sampling. Blood samples collected into heparinized tubes were centrifuged within 10 min of collection to obtain plasma, whereas blood samples collected into nonheparinized tubes were kept at ambient temperature for 2 h before centrifugation to obtain serum. Thus, plasma and serum were obtained by centrifugation at 830 × g for 15 min at room temperature using a benchtop centrifuge (ALC-PK 130; ALC, Winchester, VA) and stored at −20 °C until analysis. Fresh fecal samples were collected on the mornings of days 103 and 104 of gestation by gentle stimulation of the anus into sample bags, pooled together, and stored at −20 °C. The 2-d fecal collection approach was based on previous research (Agyekum et al. 2016; Woyengo et al., 2016) reporting on nutrient digestibility in pigs.

A rubric was developed to measure indicators of behavior, such as scratches and marks due to aggression, but this measurement was terminated after the first 2 blocks because there was no indication of aggression or fighting on any of the sows, regardless of treatment. Therefore, only feeding rate, as a measure of feeding motivation or satiety (Meunier-Salaun and Bolhuis, 2015), was investigated. Feeding rate was estimated at 1300 h on day 104 of gestation following a procedure modified from that described by Brouns et al. (1997). Briefly, the time required to consume 200 g of the standard gestation diet offered to each sow at 6 h postfeeding was recorded.

After farrowing, the total number of piglets born, mummies, stillbirths, and individual piglet BW were recorded. Piglets were cross-fostered within treatment to standardize litter sizes to 14 to 15 piglets. Cross-fostering of piglets was completed within 24 h of farrowing. After farrowing, sows had free access to a standard lactation diet (Table 1) and feed intake was recorded daily for 7 d. Piglets were individually weighed at weaning (26 ± 2 d postpartum). Sow milk production was estimated according to equations proposed by Hansen et al. (2012).

Upon weaning, 3 piglets per litter with BW closest to the average were selected, placed successively on standard nursery, grower and finisher diets, and followed from weaning to market. Body weight of the selected pigs was recorded at nursery exit (4 wk postweaning). Pigs were identified at market, allowing estimation of treatment effects on carcass characteristics including, backfat thickness, loin thickness, percent lean yield, carcass weight, and dressing percentage. The carcass index was calculated using the carcass weight and percent lean yield based on the Maple Leaf Foods (Brandon, MB, Canada) Grading Grid. Pigs were shipped at approximately 125 kg BW.

Analytical Procedures

Fecal samples were dried in a forced air draft oven at 55 °C for 72 h before grinding. Diet, fecal, and straw samples were ground using a centrifugal mill (ZM 100, RETSCH GmbH & Co. Rheinische Straße, Germany) and passed through a 1-mm sieve before analysis. Diet, fecal, and straw samples were analyzed for DM, AIA, and energy. Diet and straw samples were also analyzed for CP, ADF, NDF, starch, total dietary fiber (TDF), and ether extract. The DM (method 930.15; AOAC, 1990), CP (method 990.03; AOAC, 1990), ADF (ANKOM 08-16-06), NDF (ANKOM 08-16-06), starch (enzymatic; UV method), and ether extract (ANKOM XT20; Am 5-04; AOCS, 2005) analyses were performed by a commercial laboratory (Central Testing Laboratory Ltd., Winnipeg, MB, Canada). Gross energy was determined using an isoperibol bomb calorimeter (Model 1281, Parr Instruments, Moline, IL) with benzoic acid as the calibration standard. Total dietary fiber, soluble dietary fiber, and insoluble dietary fiber of the complete diets were analyzed according to the AOAC (2007) method 991.43 using an ANKOM TDF fiber analyzer (ANKOM Technology, Macedon, NY). Results for the control diet and straw samples are presented in Table 2. The AIA was determined using the procedure described by McCarthy et al. (1974) with some modifications. Briefly, samples were weighed, ashed in a muffle oven at 500 °C for 24 h, digested with 4 M HCl at 120 °C for 80 min, and then centrifuged at 2,500 rpm (1,295 × g) for 10 min. The pellets were rinsed with distilled water 3 times, dried at 80 °C, and then ashed at 500 °C for 24 h and weighed. Acid insoluble ash content was calculated by difference.

Table 2.

Analyzed chemical composition (as-is basis) of the gestation diet and unprocessed (Unproc) and processed (Proc) wheat and oat straws used for this study

| Item | Gestation diet | Oat | Wheat | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unproc | Proc | Unproc | Proc | ||

| DM, % | 88.8 | 93.0 | 95.4 | 94.9 | 95.4 |

| CP, % | 13.6 | 4.52 | 4.83 | 5.18 | 5.42 |

| Ether extract, % | 3.50 | 1.19 | 1.98 | 1.58 | 1.59 |

| GE, kcal/kg | 3,807 | 3,799 | 4,019 | 4,046 | 4,011 |

| Starch,% | 39.2 | 2.00 | 0.63 | 1.11 | 4.88 |

| ADF, % | 6.05 | 48.4 | 47.4 | 51.7 | 46.0 |

| NDF, % | 21.3 | 71.4 | 73.4 | 74.2 | 68.5 |

| Hemicellulose, %1 | 15.3 | 23.0 | 26.0 | 22.5 | 22.5 |

| Dietary fiber | |||||

| Insoluble | 17.4 | 73.7 | 75.7 | 77.4 | 73.8 |

| Soluble | 2.7 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 1.7 | 0.7 |

| Total | 20.2 | 74.9 | 76.4 | 79.1 | 74.5 |

1Hemicellulose = NDF − ADF.

Glucose, insulin, insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), and prolactin were assayed in plasma, whereas urea was assayed in serum. Hormone and metabolite analyses, except glucose, were performed at the Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Sherbrooke Research and Development Centre (Sherbrooke, QC, Canada). Glucose was measured at the University of Saskatchewan using commercial kit (PGO Enzymes; Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO), by enzymatic oxidation of glucose to gluconic acid and the subsequent enzymatic oxidation of o-dianisidine in the presence of glucose oxidase and peroxidase enzymes as described by Penner and Oba (2009). Insulin concentrations were measured by radioimmunoassay (RIA) using a double antibody commercial test kit (EMD Millipore Corp., Billerica, MA). Validation for a sow plasma pool was demonstrated, parallelism being 88.6% and average mass recovery being 99.4%. Assay sensitivity was 1.61 µU/mL. Intra- and interassay CV were 3.23% and 3.27%, respectively. Prolactin concentrations were determined using a homologous double antibody RIA according to Robert et al. (1989). The radioinert prolactin and the primary antibody to prolactin were purchased from A. F. Parlow (U.S. National Hormone and Pituitary Program, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Torrence, CA). Assay validation was performed using pooled serum from gestating gilts. Parallelism was 100.6% and average mass recovery was 101.4%. The sensitivity of the assay was 1.5 ng/mL. The intra- and interassay CV were 3.07% and 2.34%, respectively. The IGF-1 concentrations were measured using a commercial RIA kit for humans (ALPCO Diagnostics, Salem, NH) with small modifications as detailed previously (Plante et al., 2011). Validation for a sow plasma pool was demonstrated, parallelism being 101.2%, and average mass recovery being 101.3%. The sensitivity of the assay was 0.10 ng/mL. The intra- and interassay CV were 4.47% and 5.08%, respectively. Urea concentrations were determined by colorimetric analysis using an autoanalyzer (Auto-Analyser 3; Technicon Instruments Inc., Tarrytown, NY) according to the method of Huntington (1984). Intra- and interassay CV were 1.00% and 1.87%, respectively. Glucose analysis was conducted in triplicate, whereas the hormones and urea analyses were conducted in duplicate.

Calculations and Statistics Analysis

Apparent total tract digestibility (ATTD) of energy and DM were calculated using the AIA concentrations of the diets (i.e., gestation diet plus straw, when appropriate) and feces according to the following formula:

where Nfeces is the nutrient content in feces; Ndiet is the nutrient content in diet; AIAfeces is the AIA concentration in feces; and AIAdiet is the AIA concentration in diet. The digestible energy (DE) content of the straws was calculated using the difference method.

The total area under the curve (AUC) for the hormone and metabolite data was calculated by the trapezoidal summation method (Abramobitz and Slegun, 1972) with the preprandial data as baseline.

All data were tested for normality using the univariate procedure of SAS (SAS version 9.3; SAS Inst. Inc., Cary, NC) and for homogeneity of variance using residual plots. Outliers were removed until the Shapiro–Wilk’s test reached P > 0.05 and studentized residual fell within ±3σ. To allow a comparison of straw diets with the control, data were analyzed by ANOVA using the mixed procedure of SAS. Sow was the experimental unit in the statistical model for hormone, metabolite, and sow and litter performance during lactation, whereas individual pig was the experimental unit in the statistical model for offspring BW at nursery exit and market and carcass quality. Nursery entry BW was used as a covariate for offspring BW at nursery exit and market, and carcass quality. Block and treatment were the random and fixed effects, respectively, in the statistical model. The effect of sex was also analyzed for offspring BW at nursery exit and market and carcass quality. Data for processed and unprocessed straws were also analyzed using ANOVA for factorial arrangement of treatments using the mixed procedure of SAS, with the fixed effects of straw, processing and their interaction, and block as the random effect in the model.

The time-related variations in hormone and metabolite concentrations were analyzed using repeated-measures analysis. The model included the effects of treatment, straw source, processing, sampling time, and interactions. Preprandial data were used as a covariate for postprandial hormone and metabolite data. The covariance structure was chosen based on the structure that yielded the lowest Akaike and Bayesian information criteria. The SLICE option of PROC MIXED was used to evaluate treatment, straw source, processing, and straw × type processing effects at each sampling time. Results were reported as least squares means in figures and least square means ± pooled SEM in tables. Significance was defined as P < 0.05 and a trend towards significance at 0.05 < P ≤ 0.10. Means were separated using the PDIFF option with adjustment for the Tukey–Kramer test in SAS when a significant effect was detected. Two data points in the urea data (treatment 4) and 1 in the prolactin data (treatment 1) were defined as outliers and removed from the data set.

RESULTS

The overall effect of the treatments was evaluated as well as the effects of straw source, processing, and their interaction. Herein, treatment effect refers to overall treatment effect, whereas straw, processing, and interaction effects refer to the main effects of straw source (oat straw vs. wheat straw), processing (unprocessed vs. processed), and their interactions (straw source × processing), respectively.

Chemical Composition of Gestation Diet and Straw Samples

Chemical composition of the gestation diet and straw samples is described in Table 2. Data are from the analysis of a composited sample taken throughout the study. As expected, CP, ether extract, and starch are higher in the gestation diet than the straw samples, whereas there is little difference in gross energy, and fiber components are higher in the straw samples. Relative to oat straw, processing appeared to decrease ADF, NDF, and insoluble and total fiber in the wheat straw.

Dry Matter and Energy Digestibility

The ATTD of DM and energy and the dietary DE value of the straws was improved following processing (straw source × processing effect; P < 0.010) and the effect of processing was greater with oat than wheat straw (Table 3). Also, the ATTD of DM and energy and the dietary DE value decreased (P < 0.010) when sows were supplemented with unprocessed straw relative to processed straw (Table 3). Dry matter digestibility of processed straws was similar to the control diet, whereas the ATTD of energy and the DE content of the diet was greater in the control diet than straws, regardless of processing (Table 3, P < 0.050).

Table 3.

Effects of feeding sows a control diet supplemented with processed (Proc) or unprocessed (Unproc) oat and wheat straws during late gestation on total tract DM and energy digestibilities and calculated dietary DE of diets

| Item | Control | Oat | Wheat | SEM1 | P-value 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unproc | Proc | Unproc | Proc | Trt | Factorial | Trt | S | P | S × P | ||

| Number of sows, n | 10 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 9 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Digestibility, % | |||||||||||

| Dry matter | 72.4A | 60.0CZ | 70.9ABXY | 68.8BY | 71.1AX | 0.63 | 0.66 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Energy | 72.9A | 58.7CY | 69.2BX | 67.3BX | 69.9BX | 0.80 | 0.85 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Digestible energy, kcal/kg | 2,777A | 2,234CY | 2,648BX | 2,576BX | 2,673BX | 30.5 | 32.6 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

1SEM = pooled standard error of the means; Trt = SEM for overall dietary treatments; Factorial = SEM for processed vs. unprocessed straw dietary treatments.

2 P: Trt = overall dietary treatment effect; S = effect of straw type; P = effect of straw processing; S × P = effect of interaction between straw and processing.

A–CMeans within a row without a common superscript differ significantly (P < 0.05; overall dietary treatment effect).

X–ZMeans within a row without a common superscript differ significantly (P < 0.05; S × P effect).

Sow Metabolic Status

Two sows (1 control and 1 for unprocessed wheat straw) were excluded from the statistical analysis due to unsuccessful blood collection for the entire sampling duration. There tended (P = 0.057) to be an effect of dietary treatment on glucose concentrations at 300 min postfeeding; sows fed the control diet had the greatest and sows supplemented with unprocessed oat straw had the lowest plasma glucose concentrations (Table 4). There was a tendency for a straw source × processing effect on preprandial (P = 0.057), mean 6 h postprandial (P = 0.089) and total AUC (P = 0.070) glucose concentrations (Table 5). Processing tended (P < 0.100) to increase preprandial, 6 h postprandial and total AUC glucose concentrations in sows supplemented with oat straw, whereas the opposite effect was observed with wheat straw.

Table 4.

Effects of feeding sows a control diet containing processed (Proc) or unprocessed (Unproc) oat and wheat straws during late gestation on glucose, insulin, IGF-1, prolactin, and urea concentrations

| Sampling time with respect to postfeeding, min | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 30 | 60 | 90 | 120 | 180 | 240 | 300 | 360 | ||

| Glucose, mg/dL | Control | 61.56 | 59.74 | 64.33 | 65.47 | 65.12 | 72.82 | 78.9 | 87.94a | 80.17 |

| Oat straw Unproc | 62.80xy | 62.64 | 71.83 | 72.94 | 75.46 | 73.87 | 71.72 | 75.91b | 79.05 | |

| Oat straw Proc | 64.80x | 64.21 | 69.75 | 77.95 | 73.72 | 76.63 | 77.88 | 80.85ab | 83.6 | |

| Wheat Straw Unproc | 64.17x | 68.07 | 73.4 | 74.86 | 73.34 | 76.05 | 79.19 | 86.13a | 83.81 | |

| Wheat Straw Proc | 55.91y | 58.58 | 70.38 | 68.31 | 67.05 | 75.11 | 74.3 | 77.55ab | 77.87 | |

| SEM1 | Trt | 3.16 | 3.18 | 3.89 | 4.86 | 3.94 | 4.15 | 3.83 | 3.29 | 2.91 |

| Factorial | 2.92 | 2.72 | 3.59 | 4.72 | 3.80 | 3.84 | 3.22 | 3.12 | 2.70 | |

| P2 | Trt | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | 0.057 | NS |

| S | 0.099 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | |

| P | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | |

| S × P | 0.057 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | |

| Urea, mmol/L | Control | 6.95A | 6.99A | 7.10A | 7.16A | 7.34A | 7.46A | 7.68a | 7.73 | 7.76 |

| Oat straw | 6.48AX | 6.49AXY | 6.65AX | 6.81AX | 6.96AX | 7.04ABX | 7.28Xab | 7.40xy | 7.40 | |

| Oat straw Proc. | 6.50AX | 6.58AX | 6.65AX | 6.66AXY | 6.84AXY | 6.93ABXY | 7.09XYab | 7.19xy | 7.07 | |

| Wheat Straw | 5.05BY | 5.30BY | 5.29BY | 5.56BY | 5.72BY | 5.87BY | 6.21Yb | 6.46y | 6.52 | |

| Wheat Straw Proc. | 6.19AX | 6.32AXY | 6.46ABXY | 6.59AXY | 6.87AXY | 7.06ABX | 7.21Xab | 7.45x | 7.64 | |

| SEM1 | Trt | 0.38 | 0.40 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.37 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.41 |

| Factorial | 0.40 | 0.43 | 0.41 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.45 | |

| P2 | Trt | 0.007 | 0.036 | 0.012 | 0.029 | 0.026 | 0.036 | 0.064 | NS | NS |

| S | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.007 | 0.015 | 0.024 | 0.056 | NS | |

| P | 0.007 | 0.032 | 0.013 | 0.054 | 0.031 | 0.027 | 0.078 | 0.078 | NS | |

| S × P | 0.003 | 0.008 | 0.001 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.012 | 0.032 | 0.053 | NS | |

| Insulin, µU/mL | Control | 10.24 | 13.79 | 21.17 | 27.57 | 16.55 | 21.73 | 15.02 | 17.23 | 15.45 |

| Oat straw | 5.43 | 8.47 | 24.80 | 28.51 | 29.07 | 21.71 | 16.42 | 15.52 | 12.28 | |

| Oat straw Proc. | 6.66 | 7.89 | 21.94 | 38.60 | 30.11 | 27.17 | 16.83 | 14.12 | 10.26 | |

| Wheat Straw | 5.71 | 12.26 | 22.03 | 29.18 | 26.51 | 18.57 | 17.73 | 22.20 | 11.40 | |

| Wheat Straw Proc. | 4.49 | 12.69 | 35.29 | 39.32 | 23.39 | 17.80 | 15.46 | 16.78 | 11.00 | |

| SEM1 | Trt | 1.69 | 2.67 | 6.13 | 6.66 | 4.99 | 4.25 | 3.39 | 3.66 | 2.79 |

| Factorial | 1.49 | 2.60 | 6.38 | 6.30 | 5.67 | 4.08 | 3.43 | 4.14 | 2.31 | |

| P-value2 | Trt | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| S | 0.013 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | |

| P | NS | NS | NS | 0.088 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | |

| S × P | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | |

| IGF-1, ng/mL | Control | 49.83 | 49.23ab | 46.65AB | 49.51 | 48.08 | 47.63ab | 47.24 | 48.64 | 49.56 |

| Oat straw | 54.75 | 62.15Xa | 58.92A | 56.00 | 55.98x | 55.20a | 54.94 | 55.72 | 54.37 | |

| Oat straw Proc. | 46.71 | 54.13XYab | 51.15AB | 50.07 | 48.45xy | 48.18ab | 45.92 | 50.32 | 47.94 | |

| Wheat Straw | 45.92 | 45.49Yb | 42.91B | 43.30 | 42.77y | 41.75b | 41.20 | 42.23 | 42.44 | |

| Wheat Straw Proc. | 52.79 | 56.70XYab | 50.88AB | 52.61 | 53.11xy | 53.95ab | 51.45 | 52.24 | 53.55 | |

| SEM1 | Trt | 5.48 | 5.52 | 4.95 | 5.13 | 5.03 | 5.02 | 5.29 | 5.43 | 5.22 |

| Factorial | 6.08 | 5.98 | 5.26 | 5.72 | 5.57 | 5.48 | 5.68 | 5.79 | 5.66 | |

| P-value2 | Trt | NS | 0.084 | 0.042 | NS | NS | 0.099 | NS | NS | NS |

| S | NS | NS | 0.038 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | |

| P | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | |

| S × P | 0.092 | 0.032 | NS | NS | 0.078 | NS | NS | NS | NS | |

| Prolactin, ng/mL | Control | 4.22ab | 4.21 | 4.12 | 3.91 | 4.25 | 4.06 | 3.73 | 3.96 | 3.67 |

| Oat straw | 3.34YZb | 4.55 | 4.41 | 3.63 | 2.91 | 2.90 | 3.23 | 3.13 | 3.60 | |

| Oat straw Proc. | 4.24XYab | 4.30 | 3.76 | 3.06 | 2.88 | 2.85 | 2.92 | 4.25 | 4.10 | |

| Wheat Straw | 5.06Xa | 4.98 | 3.33 | 3.21 | 2.95 | 3.11 | 3.55 | 3.19 | 3.24 | |

| Wheat Straw Proc. | 3.93ZYab | 3.89 | 3.51 | 3.99 | 3.03 | 3.37 | 3.89 | 3.58 | 3.45 | |

| SEM1 | Trt | 0.40 | 0.51 | 0.48 | 0.52 | 0.45 | 0.44 | 0.42 | 0.45 | 0.46 |

| Factorial | 0.46 | 0.53 | 0.41 | 0.50 | 0.33 | 0.39 | 0.43 | 0.54 | 0.50 | |

| P-value2 | Trt | 0.067 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| S | 0.086 | NS | NS | NS | NS | 0.078 | NS | NS | NS | |

| P | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | |

| S × P | 0.032 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

1SEM = pooled standard error of the means; Trt = SEM for overall dietary treatments; Factorial = SEM for processed vs. unprocessed straw dietary treatments.

2 P-values: Trt = overall dietary treatment effect; S = effect of straw type; P = effect of straw processing; S × P = effect of interaction between straw and processing. NS = nonsignificant (P > 0.10).

A,BMeans in a column within a variable without a common superscript differ significantly (P < 0.05; overall dietary treatment effect).

a,bMeans in a column within a variable without a common superscript tended to differ (P < 0.10; overall dietary treatment effect).

X–ZMeans in a column within a variable without a common superscript differ significantly (P < 0.05; S × P effect).

x,yMeans in a column within a variable without a common superscript tended to differ (P < 0.10; S × P effect).

Table 5.

Effects of feeding sows a control diet containing processed (Proc) or unprocessed (Unproc) oat and wheat straws during late gestation on the preprandial, mean 6 h postprandial, and area under the curve (AUC) for glucose, insulin, IGF-1, prolactin, and urea concentrations

| Item | Control | Oat | Wheat | SEM1 | P-value 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unproc | Proc | Unproc | Proc | Trt | Factorial | Trt | S | P | S × P | ||

| Number of sows, n | 7 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 8 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Glucose, mg/dL3 | |||||||||||

| Preprandial | 61.56 | 62.80xy | 64.80x | 64.17x | 55.91y | 3.16 | 2.92 | NS | 0.099 | NS | 0.057 |

| Postprandial | 71.98 | 73.12xy | 75.21x | 75.82x | 73.21y | 1.83 | 2.01 | NS | NS | NS | 0.089 |

| Total AUC, mg/dL∙h | 26,294 | 26,188xy | 27,188x | 27,782x | 25,733y | 2,612 | 872 | NS | NS | NS | 0.070 |

| Urea, mmol/L3 | |||||||||||

| Preprandial | 6.95A | 6.48AX | 6.50AX | 5.05BY | 6.19AX | 0.38 | 0.40 | 0.007 | 0.001 | 0.007 | 0.003 |

| Postprandial | 6.75AB | 6.80AB | 6.62B | 6.88AB | 7.03A | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.005 | 0.007 | NS | NS |

| Total AUC, mmol/L∙h | 2,648a | 2,552Xa | 2,462Xa | 2,144Yb | 2,540Xa | 124 | 125 | 0.061 | 0.027 | 0.071 | 0.039 |

| Insulin, µU/mL3 | |||||||||||

| Preprandial | 10.24 | 5.43 | 6.66 | 5.71 | 4.49 | 1.69 | 1.49 | NS | 0.013 | NS | NS |

| Postprandial | 17.04 | 20.28 | 21.22 | 20.13 | 23.48 | 2.08 | 2.18 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Total AUC, µU/mL∙h | 6,476 | 6,830 | 7,302 | 7,035 | 7071 | 873 | 877 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| IGF-1, ng/mL3 | |||||||||||

| Preprandial | 49.83 | 54.75 | 46.71 | 45.92 | 52.79 | 5.48 | 6.08 | NS | NS | NS | 0.092 |

| Postprandial | 47.34BC | 52.29AX | 50.63AX | 45.84CY | 49.76ABX | 1.51 | 1.52 | 0.001 | 0.001 | NS | 0.002 |

| Total AUC, ng/mL∙h | 17,233 | 20,009 | 18,092 | 15,394 | 18,440 | 1,719 | 1,655 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Prolactin, ng/mL3 | |||||||||||

| Preprandial | 4.22ab | 3.34YZb | 4.24XYab | 5.06Xa | 3.96YZab | 0.40 | 0.46 | 0.067 | 0.086 | NS | 0.032 |

| Postprandial | 3.95A | 3.92AX | 3.48ABXY | 3.02BY | 3.69AX | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.001 | 0.029 | NS | 0.001 |

| Total AUC, ng/mL∙h | 1,451 | 1,203 | 1,282 | 1,273 | 1,301 | 110 | 110 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

1 SEM = pooled standard error of the means; Trt = SEM for overall dietary treatments; Factorial = SEM for processed vs. unprocessed straw dietary treatments.

2 P-values: Trt = overall dietary treatment effect; S = effect of straw type; P = effect of straw processing; S x P = effect of interaction between straw and processing. NS = nonsignificant (P > 0.10).

3Preprandial data represent fasted blood samples collected at one time point before feeding, whereas postprandial data represent means for blood samples collected at 8 time points postfeeding. Preprandial data was used as a covariate for postprandial data.

A,BMeans in a column within a variable without a common superscript differ significantly (P < 0.05; overall dietary treatment effect).

a,bMeans in a column within a variable without a common superscript tended to differ (P < 0.10; overall dietary treatment effect).

X–ZMeans in a column within a variable without a common superscript differ significantly (P < 0.05; S × P effect).

x,yMeans in a column within a variable without a common superscript tended to differ (P < 0.10; S × P effect).

Preprandial plasma urea concentration was lower (P < 0.050) in sows fed unprocessed wheat straw compared with the 4 other treatment groups (Table 5), whereas sows fed unprocessed wheat straw had the lowest urea concentrations before feeding and up to 180 min postfeeding (P < 0.050, Table 4). There was also a straw source × processing effect on preprandial (P = 0.059) and total AUC (P < 0.050) urea concentrations (Table 5). Processing resulted in increased preprandial and total AUC urea concentrations when sows were fed wheat- but not oat straw-supplemented diets.

Sow Endocrine Status

Sows fed oat straw had greater (P < 0.050) mean preprandial insulin concentrations than sows fed wheat straw (Table 5). Insulin concentrations peaked at approximately 90 min after feeding (Table 4) and were unaffected by treatment (Table 5). Similarly, total AUC insulin concentrations were unaffected by treatment (Table 5). Sows supplemented with unprocessed oat straw had greater IGF-1 concentrations than sows supplemented with unprocessed wheat straw at 30 (P = 0.084), 60 (P < 0.050), and 180 min (P = 0.099) postprandial (Table 4). Conversely, there was a tendency (P = 0.067) for sows supplemented with unprocessed wheat straw to have the greater preprandial prolactin concentration than sows supplemented with unprocessed oat straw to (Table 5). However, treatment had no effect on preprandial concentrations and total AUC for IGF-1, and total AUC for prolactin concentrations (Table 5). Processing increased the mean 6 h postprandial IGF-1 and prolactin concentrations when sows were fed a diet supplemented with wheat straw, whereas the concentrations did not change when sows were fed oat straw (straw source × processing, P < 0.050; Table 5).

Sow Late Gestation and Lactation Performance

Six sows (4 control, and 1 each for unprocessed oat and wheat straws) were excluded from the statistical analyses due to death (2 sows) or health reasons (4 sows; abortion and not pregnant during late gestation check). At the onset of the experiment (days 86 ± 2 of pregnancy), parity, and backfat thickness were similar among the treatments (Table 6). Treatment had no effect on the total number of piglets born alive, stillbirths, average piglet birth weight, or number weaned (Table 6). Furthermore, treatment had no effect on estimated milk production (Table 6). There were no effects of straw processing or processing × straw source interaction on any of the sow performance variables evaluated throughout lactation (Table 6). Time required to ingest 200 g of feed, determined on day 18 of the trial at 1300 h postfeeding as an indication of feeding motivation, was not affected by dietary treatment and averaged 1.20 ± 0.03 min (data not shown).

Table 6.

Effects of feeding sows a control diet containing processed (Proc) or unprocessed (Unproc) oat and wheat straws during late gestation on sow and piglet performance throughout lactation

| Item | Control | Oat | Wheat | SEM1 | P-value 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unproc | Proc | Unproc | Proc | Trt | Factorial | Trt | S | P | S x P | ||

| Number of sows, n | 26 | 29 | 30 | 29 | 30 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Parity | 2.1 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 1.6 | 0.33 | 0.32 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Back fat thickness, day 86, mm | 20.1 | 20.1 | 20.4 | 20.5 | 20.2 | 0.49 | 0.32 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Litter number, n | |||||||||||

| Born alive | 14.2 | 14.9 | 14.7 | 14.6 | 14.1 | 0.69 | 0.64 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Still birth | 1.70 | 1.31 | 0.87 | 1.55 | 1.00 | 0.25 | 0.27 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| At weaning | 11.7 | 12.2 | 12.4 | 12.2 | 12.1 | 0.24 | 0.24 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Average piglet weight, kg | |||||||||||

| At birth | 1.46 | 1.39 | 1.49 | 1.42 | 1.46 | 0.05 | 0.05 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| At weaning | 6.87 | 7.02 | 7.36 | 6.86 | 6.83 | 0.19 | 0.18 | NS | 0.037 | NS | NS |

| ADG | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.01 | 0.01 | NS | 0.080 | NS | NS |

| Sow lactation ADFI days 1–7, kg/d | 4.26ab | 4.71a | 4.71a | 4.13b | 4.37ab | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.053 | 0.010 | NS | NS |

| Lactation milk production, kg/d3 | 7.61 | 7.86 | 7.91 | 7.90 | 7.81 | 0.13 | 0.13 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

1SEM = pooled standard error of the means; Trt = SEM for overall dietary treatments; Factorial = SEM for processed vs. unprocessed straw dietary treatments.

2 P-values: Trt = overall dietary treatment effect; S = effect of straw type; P = effect of straw processing; S x P = effect of interaction between straw and processing. NS, non-significant (P > 0.10).

3Calculated based on Hansen et al. (2012).

a,bMeans in a column within a variable without a common superscript tended to differ (P < 0.10; overall dietary treatment effect).

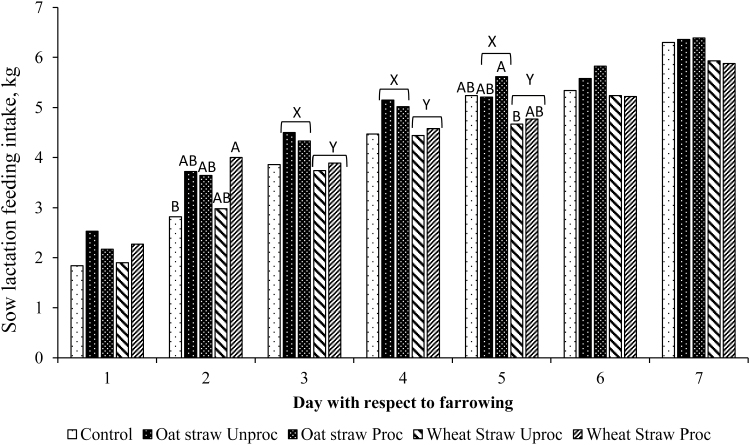

Sows fed oat straw during late gestation had a greater feed intake on days 3, 4, and 5 postfarrowing than sows fed wheat straw (P < 0.050; Figure 1) resulting in a greater (P < 0.050) ADFI from days 1 to 7 postpartum (Table 6). Similarly, average piglet BW at weaning increased (P < 0.050) and ADG throughout lactation tended to increase (P = 0.080) for piglets from sows supplemented with oat straw during late gestation (Table 6).

Figure 1.

Daily feed intake in lactating sows fed a control diet containing processed or unprocessed oat and wheat straws during late gestation. Values are means for overall dietary treatments. A,BBars within a variable with different superscripts differ (overall treatment effect: P < 0.05). X,YBars within a variable with different superscripts differ (effect of straw type: P < 0.05).

Body Weight and Carcass Quality of Offspring at Market

There was a tendency for a straw source × processing effect on BW at nursery entry (P = 0.056), whereas piglets from sows consuming processed oat straw during gestation had a greater (P < 0.05) BW at weaning (7.51 kg) than piglets from sows consuming unprocessed oat straw (7.16 kg, data not shown). This effect of processing was not observed with wheat straw. However, offspring from sows fed unprocessed straws had a lower BW at nursery exit than those fed processed straws (24.4 vs. 25.1 kg; effect of processing; P < 0.050). Treatment had no effect and there were no straw source × processing effects on BW at market (132.7 ± 0.95 kg; mean ± Trt SEM), carcass weight (107.5 ± 1.02), dressing percentage (81.0 ± 0.46), backfat depth (15.8 ± 0.47), loin depth (67.6 ± 0.97), carcass yield (62.2 ± 0.24), or index (108.8 ± 0.15).

DISCUSSION

Nutrient Digestibility

Processing the oat and wheat straws resulted in improvements in the ATTD of energy and DM. Renteria-Flores et al. (2008) reported that intake of insoluble fiber in gestating sows decreased dietary energy digestibility, whereas intake of soluble fiber improved energy digestibility. However, the results of our dietary fiber analysis suggest minimal effects of processing on solubility as measured by the TDF method 991.43 (AOAC). Nonetheless, we suspect that the processing technique employed in our study might have improved digestibility by mechanisms not directly related to changes in solubility but such as changes in fiber matrix, reduction in fiber length, and opening up the cell wall structure to enhance utilization by the sows.

Sow Metabolic and Endocrine Status

Studies have shown that incorporating fiber-rich ingredients into pregnant sow diets can alter hormonal and metabolic responses and thereby positively influence sow satiety, behavior (Ramonet et al. 2000; Farmer et al., 2002; de Leeuw et al. 2004), and performance (Quesnel et al., 2009). In the current study, a tendency for an interaction between straw source and processing was observed on pre- and postprandial glucose concentrations. Specifically, processing numerically increased glucose concentrations in the sows fed oat straw and decreased glucose concentrations in sows fed wheat straw. It is not clear why glucose concentration tended to increase when processing was applied to oat but not wheat straw. However, differences in fiber matrix and components, and processing effect on the fiber in oat and wheat straws could be the reason. For instance, as indicated previously in this study, processing had a greater impact on the ATTD of DM for sows fed oat straw vs. wheat straw (10.9% vs. 2.3% improvement with processing for oat and wheat straw, respectively), suggesting that processing had a greater impact on the fiber in oat straw relative to wheat straw. Preprandial insulin concentrations were also greater in sows fed oat straw vs. wheat straw, which was consistent with the tendency for increased preprandial glucose concentrations with oat straw. However, the mean 6 h postprandial concentration of insulin was not affected by straw source or processing in the current study, albeit a tendency for an interaction between straw source and processing on postprandial glucose concentrations. The reason for this observation is not clear; although it is possible that elevated postprandial glucose concentrations may be below the minimum threshold required for glucose-induced insulin secretion. Additionally, it is known that the liver extracts substantial amounts of insulin and thus peripheral plasma insulin may not accurately reflect insulin secretion (Leighton et al., 2017).

The lack of a treatment effect on postprandial insulin concentrations coincided with the lack of a treatment effect on feeding motivation tested in sows at 1300 h postprandial. Postprandial insulin concentrations have been linked to feeding motivation and hunger in sows (Meunier-Salaün et al., 2001). Therefore, the absence of a treatment effect on the mean 6 h postprandial insulin concentration in this study may in part explain the lack of effect on sow feeding motivation. However, the current study focused on investigating feeding motivation 6 h after a once-daily feeding, which can be considered short term. Therefore, the effect of the dietary treatments used in the current study and (or) fed twice daily on long-term (e.g., 12 h postprandial) feeding motivation should be investigated.

Processing interacted with straw source to numerically decrease the AUC for urea concentrations in sows supplemented with oat straw, whereas an increase in urea AUC was observed for wheat straw with processing. Urea is a nitrogen source for the gut microbes and can be used to estimate the state of protein metabolism in pigs. Dietary fibers are fermented to some extent in the gut of the pig to influence microbial mass and activity (Zijlstra et al., 2012; Jha and Berrocoso, 2015; Agyekum and Nyachoti, 2017). However, highly fermentable fibers tend to increase microbial mass, which leads to a greater transfer of urea from the blood to the gut, thereby reducing plasma concentrations (Younes et al., 1995). Results for the urea AUC suggest that the processing method used in this study had a greater impact on the fiber in wheat than that of oat straw. However, the lower preprandial urea concentrations observed in sows fed wheat straw suggest lower protein oxidation in the liver that may be correlated with lower intestinal absorption of protein in the fasted state when feeding wheat straw to sows (Zervas and Zijlstra, 2002a,b).

In swine, prolactin is a key hormone for the initiation and maintenance of milk production (Farmer et al., 1998) and a high-fiber intake tends to increase prolactin concentrations in pregnant sows (Farmer et al., 1995; Quesnel et al., 2009). Current findings showed that processing increased preprandial prolactin concentrations in sows fed the oat relative to wheat straw, whereas the opposite was true for postprandial prolactin concentrations. Farmer et al. (1995) reported a tendency for greater prolactin concentrations in pregnant sows fed a high-fiber diet containing wheat bran and corn cobs, but not oat hull and oats, compared with a low fiber diet. Quesnel et al. (2009) reported greater concentrations of prolactin during gestation in sows fed a high fiber diet (NDF content, 30.7%) containing a mixture of soybean hulls, wheat bran, sunflower meal, and sugar beet pulp (nearly 20%) compared with a low fiber diet (NDF content, 17.2%). In a companion study, Loisel et al. (2013) saw no effect on prolactin concentrations when sows were fed a high-fiber diet (NDF content, 20.3%) containing lower levels of the same fibrous ingredients compared with the lower fiber diet (NDF content, 13.1%). Collectively, data from the current study and the above references suggest that the level and source of fiber affect the prolactin response in pregnant sows. It is not clear why processing had contrasting effects on prolactin concentrations when sows were supplemented with oat and wheat straw.

Insulin-like growth factor-1 plays an essential role in normal growth and development, including prenatal and postnatal growth (Baker et al., 1993) and lactation in sows (Lucy, 2008). In the study by Quesnel et al. (2009), preprandial IGF-1 concentrations were not affected when pregnant sows were fed a high-fiber diet containing a mixture of soybean hulls, wheat bran, sunflower meal, and sugar beet pulp compared with the control diet. In the current study, dietary treatments had no effect on preprandial IGF-1 concentrations, yet processing increased postprandial IGF-1 concentrations in sows fed wheat straw (by 8.7%) while decreasing that of sows fed oat straw (by 3.2%). There is a scarcity of information on the effects of dietary fiber on concentrations of IGF-1 and other growth factors. Based on current findings, we can speculate that fiber source and solubility can affect postprandial IGF-1 concentrations in the late pregnant sow. Further studies are required to elucidate the biological relevance of this observation.

Sow and Litter Performance During Lactation

Dietary supplementation with straw during late pregnancy did not increase total number of piglets born alive or piglet birth weight. The effect of high-fiber intake during the entire or late gestation on litter size and piglet birth weight has been inconsistent among studies. In some studies, high-fiber intake during gestation had no effect (Guillemet et al., 2007; Oliviero et al., 2009; Loisel et al., 2013); in others it increased (Matt et al., 1994; Che et al., 2011) or even decreased (Vestergaard and Danielsen, 1998; Holt et al., 2006) litter size and (or) piglet BW at farrowing. These inconsistencies are likely due to differences in treatment duration, source and level of dietary fiber, sow genetics, and parity.

In the present study, sows fed oat straw had a greater feed intake in the first week of lactation compared with sows fed wheat straw. An increase in lactation feed intake with high-fiber diets during gestation has been attributed to the bulkiness of the gestation diet, which, in turn, facilitates adaptation of the sows to the abrupt increase in feed intake necessary to meet lactation demands (Matte et al., 1994). Although differences in physicochemical properties between oat and wheat straw can be implicated, it is not clear why wheat straw diets in late pregnancy did not increase feed intake postfarrowing in the present study. Results from other studies (Farmer et al., 1996; Guillement et al., 2006) also suggest beneficial effects of providing a fibrous diet during pregnancy on feed intake during lactation, and this, especially in early lactation.

Piglet BW and ADG from birth to weaning were greater for sows fed oat straw relative to sows fed wheat straw during gestation. This was consistent with the greater early postpartum feed intake in those same sows. Thus, it could be speculated that increased feed intake postfarrowing improved litter growth rate. Increased sow lactation feed intake has been linked to greater milk production (Strathe et al., 2017). However, the estimated milk production for the entire lactation period in the current study did not differ among dietary treatments. This absence of effect may be partly due to “artifacts” of the determinations, variability, and sensitivity of the model used to predict milk yield. Indeed, milk yield was estimated using equations based on growth rate, litter size, and sow parity, whereas sow parity and litter size were equalized among the dietary treatments. This method was chosen over the weigh–suckle–weigh or isotope dilution methods to measure milk output because it does not disrupt the normal social interaction of sow and litter or require fasting. On the other hand, the main endpoint is the growth rate of piglets and that was affected by straw type in the current study.

Offspring Performance

Studies in the literature looking at the effects of high fiber intake during late gestation on litter performance have focused on the lactation period. Therefore, it is not clear if there is a “carry-over” effect for the improvement, if any, on litter growth during lactation to the grow-finish phase. To the best of our knowledge, the current study was the first investigating the effects of supplementing late gestation diets with processed or unprocessed straw on offspring BW at nursery exit, growth to market weight, and carcass quality indices. Offspring from sows fed oat straw had greater BW at weaning than piglets from sows fed wheat straw, but it was offspring from sows fed processed straws that had greater BW at nursery exist. Yet, these BW were not superior to BW of piglets from Control sows. The BW of piglets at weaning tends to influence nursery exit BW (Douglas et al. 2013; Collins et al., 2017); therefore, one would have expected straw source to influence nursery exit BW because it affected weaning weight. It is not clear why the effect of straw processing, but not straw source, results in heavier pigs at nursery exit, but it will be imperative to ascertain the effect on feed efficiency in future studies.

In this study, the increase in offspring BW observed at weaning and at nursery exit due to supplementing late gestation diet with processed and (or) unprocessed straw did not influence market BW or any of the carcass quality indices measured. Therefore, supplementing late gestation diets with processed and unprocessed straw had no major impact on offspring production measures during the finishing stage or on carcass quality.

Conclusions and Perspective

Data on aggression and (or) satiety were not conclusive in the current study. However, processing improved diet digestibility and energy content, and these effects were greater with oat straw than wheat straw. Processing the oat straw increased plasma glucose in sows, whereas the opposite effect was observed with the wheat straw. Moreover, pregnant sows fed oat straw from day 86 of gestation to farrowing had increased feed intake in early lactation and greater average piglet weaning weights. Overall, results suggest that oat, but not wheat, straw affected sow physiology and provided benefits for gestating sows. There was some indication that further benefits could be obtained through processing. Even though producers need to consider the challenges of straw handling at the feed mill and for manure management, the opportunity exists for pork producers to use processed oat straw as a feeding strategy in gestating sows to improve sow lactation and piglet performance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to acknowledge the support and expertise of Raelene Petracek and Doug Gillis at the Prairie Swine Centre Inc., John Smillie at the Canadian Feed Research Centre, and Anne Bernier and Lynda Marier at AAFC Sherbrooke R&D Centre.

Footnotes

This project is funded by Swine Innovation Porc within the Swine Cluster 2: Driving Results Through Innovation research program. Funding is provided by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada through the Agri-Innovation Program, provincial producer organizations and industry partners, Mitacs-Elevate, and Sask Pork (Saskatoon, SK, Canada).

LITERATURE CITED

- Abramobitz M., and Slegun I. A.. 1972. Handbook of mathematical functions. Dover Publ. Inc, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Agyekum A. K. and Nyachoti C. M.. 2017. Nutritional and metabolic consequences of feeding high-fiber diets to swine: a review. Engineering 3:716–725. doi: 10.1016/J.ENG.2017.03.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Agyekum A. K., Regassa A., Kiarie E., and Nyachoti C. M.. 2016. Nutrient digestibility, digesta volatile fatty acids, and intestinal bacterial profile in growing pigs fed a distillers dried grains with solubles containing diet supplemented with a multi-enzyme cocktail. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 212:70–80. doi; 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2015.12.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- AOAC, Int 2007. Official methods of analysis of AOAC International. AOAC International, Gaithersburg, MD. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC 1990. Official methods of analysis of the AOAC. 15th ed. Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC), Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- AOCS 2005. Approved Procedure Am 5-04, Rapid determination of oil/fat utilizing high temperature solvent extraction. American Oil Chemists Society, Urbana, IL. [Google Scholar]

- Baker J., Liu J. P., Robertson E. J., and Efstratiadis A.. 1993. Role of insulin-like growth factors in embryonic and postnatal growth. Cell 75:73–82. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(05)80085-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouns F., Edwards S. A., and English P. R.. 1997. The effect of dietary inclusion of sugar-beet pulp on the feeding behaviour of dry sows. Anim. Sci. 65:129–133. doi; 10.1017/S1357729800016386 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- CCAC 2009. Guidelines on: the care and use of farm animals in research, teaching and testing. Can. Council. Anim. Care, Ottawa, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Che L., Feng D., Wu D., Fang Z., Lin Y., and Yan T.. 2011. Effect of dietary fibre on reproductive performance of sows during the first two parities. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 46:1061–1066. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0531.2011.01787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins C. L., Pluske J. R., Morrison R. S., McDonald T. N., Smits R. J., Henman D. J., Stensland I., and Dunshea F. R.. 2017. Post-weaning and whole-of-life performance of pigs is determined by live weight at weaning and the complexity of the diet fed after weaning. Anim. Nutr. 3:372–379. doi: 10.1016/j.aninu.2017.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielsen V., and Vestergaard E.-M.. 2001. Dietary fibre for pregnant sows: effect on performance and behaviour. Anim. Feed Sci. Tech. 90:71–80. doi: 10.1016/S0377-8401(01)00197-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries S., Pustjens A., Schols H., Hendriks W., and Gerrits W.. 2012. Improving digestive utilization of fiber-rich feedstuffs in pigs and poultry by processing and enzyme technologies: a review. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 178:123–138. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2012.10.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas S. L., Edwards S. A., Sutcliffe E., Knap P. W., and Kyriazakis I.. 2013. Identification of risk factors associated with poor lifetime growth performance in pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 91:4123–4132. doi: 10.2527/jas.2012-5915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer C., Meunier-Salaün M. C., Bergeron R., and Robert S.. 2002. Hormonal response of pregnant gilts fed a high-fiber or a concentrate diet once or twice daily. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 82:159–164. doi: 10.4141/A01-039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer C., Robert S., and Matte J. J.. 1996. Lactation performance of sows fed a bulky diet during gestation and receiving growth hormone-releasing factor during lactation. J. Anim. Sci. 74:1298–1306. doi: 10.2527/1996.7461298x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer C., Robert S., Matte J. J., Girard C. L., and Martineau G. P.. 1995. Endocrine and peripartum behavioral responses of sows fed high-fiber diets during gestation. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 75:531–536. doi: 10.4141/cjas95-080 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer C., Robert S., and Rushen J.. 1998. Bromocriptine given orally to periparturient of lactating sows inhibits milk production. J. Anim. Sci. 76:750–757. doi: 10.2527/1998.763750x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieshop C. M., Reese D. E., and Fahey G. C.. 2001. Nonstarch polysaccharides and oligosaccharides in swine nutrition. In: Lewis A. J. and Southern L. L., editors, Swine nutrition. 2nd ed. Taylor & Francis Group, LLC (CRC Press), Boca Raton, FL. p.107–130. [Google Scholar]

- Guillemet R., Dourmad J. Y., and Meunier-Salaün M. C.. 2006. Feeding behavior in primiparous lactating sows: impact of a high-fiber diet during pregnancy. J. Anim. Sci. 84:2474–2481. doi: 10.2527/jas.2006-024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillemet R., Hamard A., Quesnel H., Père M. C., Etienne M., Dourmad J. Y., and Meunier-Salaün M. C.. 2007. Dietary fibre for gestating sows: effects on parturition progress, behaviour, litter and sow performance. Animal 1:872–880. doi: 10.1017/S1751731107000110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen A. V., Strathe A. B., Kebreab E., France J., and Theil P. K.. 2012. Predicting milk yield and composition in lactating sows: a bayesian approach. J. Anim. Sci. 90:2285–2298. doi: 10.2527/jas.2011-4788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt J. P., Johnston L. J., Baidoo S. K., and Shurson G. C.. 2006. Effects of a high-fiber diet and frequent feeding on behavior, reproductive performance, and nutrient digestibility in gestating sows. J. Anim. Sci. 84:946–955. doi: 10.2527/2006.844946x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntington G. B. 1984. Net absorption of glucose and nitrogenous compounds by lactating holstein cows. J. Dairy Sci. 67:1919–1927. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(84)81525-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha R., and Berrocoso J. D.. 2015. Review: dietary fiber utilization and its effects on physiological functions and gut health of swine. Animal 9:1441–1452. doi: 10.1017/S1751731115000919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Leeuw J. A., Jongbloed A. W., and Verstegen M. W.. 2004. Dietary fiber stabilizes blood glucose and insulin levels and reduces physical activity in sows (sus scrofa). J. Nutr. 134:1481–1486. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.6.1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leighton E., Sainsbury C. A., and Jones G. C.. 2017. A practical review of C-peptide testing in diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 8:475–487. doi: 10.1007/s13300-017-0265-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loisel F., Farmer C., Ramaekers P., and Quesnel H.. 2013. Effects of high fiber intake during late pregnancy on sow physiology, colostrum production, and piglet performance. J. Anim. Sci. 91:5269–5279. doi: 10.2527/jas.2013-6526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucy M. C. 2008. Functional differences in the growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor axis in cattle and pigs: implications for post-partum nutrition and reproduction. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 43 (Suppl 2):31–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0531.2008.01140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matte J. J., Robert S., Girard C. L., Farmer C., and Martineau G. P.. 1994. Effect of bulky diets based on wheat bran or oat hulls on reproductive performance of sows during their first two parities. J. Anim. Sci. 72:1754–1760. doi: 10.2527/1994.7271754x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy J. F., Aherne F. X., and Okai D. B.. 1974. Use of HCl-insoluble ash as an index material for determining apparent digestibility with pigs. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 54:107–109. doi: 10.4141/cjas74-016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meunier-Salaün M. C., and Bolhus J. E.. 2015. High-fiber feeding in gestation. In: Farmer C., editor, The gestating and lactating sow. Wageningen Academic Publisher, Wageningen, the Netherlands: p. 95–116. [Google Scholar]

- Meunier-Salaün M. C., Edwards S. A., and Robert S.. 2001. Effect of dietary fibre on the behaviour and health of the restricted fed sow. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 90:53–69. doi: 10.1016/S0377-8401(01)00196-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Niiyama M., Yonemichi H., Harada E., Syuto B., and Kitagawa H.. 1985. A simple catheterization from the ear vein into the jugular vein for sequential blood sampling from unrestrained pigs. Jpn. J. Vet. Res. 33:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NRC 2012. Nutrient requirement of swine. 11th ed. National Academy Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Oliviero C., Kokkonen T., Heinonen M., Sankari S., and Peltoniemi O.. 2009. Feeding sows with high fibre diet around farrowing and early lactation: impact on intestinal activity, energy balance related parameters and litter performance. Res. Vet. Sci. 86:314–319. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penner G. B., and Oba M.. 2009. Increasing dietary sugar concentration may improve dry matter intake, ruminal fermentation, and productivity of dairy cows in the postpartum phase of the transition period. J. Dairy Sci. 92:3341–3353. doi: 10.3168/jds.2008-1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plante P.-A., Laforest J.-P., and Farmer C.. 2011. Effect of supplementing the diet of lactating sows with NuPro® on their performances and that of their piglets. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 91:295–300. doi: 10.4141/cjas2010-008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quesnel H., Meunier-Salaün M. C., Hamard A., Guillemet R., Etienne M., Farmer C., Dourmad J. Y., and Père M. C.. 2009. Dietary fiber for pregnant sows: influence on sow physiology and performance during lactation. J. Anim. Sci. 87:532–543. doi: 10.2527/jas.2008-1231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramonet Y., Robert S., Aumaitre A., Dourmad J. Y., and Meunier-Salaun M. C.. 2000. Influence of the nature of dietary fibre on digestive utilization of some metabolite and hormone profiles and the behaviour of pregnant sows. Anim. Sci. 70:275–286. doi: 10.1017/S1357729800054734 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reese D. E.1997. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1209&context=coopext_swine Dietary fiber in sow gestation diets—a review. Nebraska Swine Report. (Accessed 12 June 2018).

- Renteria-Flores J. A., Johnston L. J., Shurson G. C., and Gallaher D. D.. 2008. Effect of soluble and insoluble fiber on energy digestibility, nitrogen retention, and fiber digestibility of diets fed to gestating sows. J. Anim. Sci. 86:2568–2575. doi: 10.2527/jas.2007-0375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert S., de Passillé A. M. B., St-Pierre N., Dubreuil P., Pelletier G., Petitclerc D., and Brazeau P.. 1989. Effect of the stress of injections on the serum concentration of cortisol, prolactin, and growth-hormone in gilts and lactating sows. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 69:663–672. doi: 10.4141/cjas89-080 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strathe A. V., Bruun T. S., and Hansen C. F.. 2017. Sows with high milk production had both a high feed intake and high body mobilization. Animal. 15:1–9. doi: 10.1017/S1751731117000155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vestergaard E. M., and Danielsen V.. 1998. Dietary fibre for sows: effect of large amounts of soluble and insoluble fibres in the pregnancy period on the performance of sows during three reproductive cycles. Anim. Sci. 68:355–362. doi: 10.1017/S1357729800010134 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Veum T. L., Crenshaw J. D., Crenshaw T. D., Cromwell G. L., Easter R. A., Ewan R. C., Nelssen J. L., Miller E. R., Pettigrew J. E., and Ellersieck M. R.. 2009. The addition of ground wheat straw as a fiber source in the gestation diet of sows and the effect on sow and litter performance for three successive parities. J. Anim. Sci. 87:1003–1012. doi: 10.2527/jas.2008-1119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woyengo T. A., Sánchez J. E., Yáñez J., Beltranena E., Cervantes M., Morales A., and Zijlstra R. T.. 2016. Nutrient digestibility of canola co-products for grower pigs. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 222:7–16. doi; 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2016.09.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Younes H., Garleb K., Behr S., Rémésy C., and Demigné C.. 1995. Fermentable fibers or oligosaccharides reduce urinary nitrogen excretion by increasing urea disposal in the rat cecum. J. Nutr. 125:1010–1016. doi: 10.1093/jn/125.4.1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zervas S., and Zijlstra R. T.. 2002a. Effects of dietary protein and oathull fiber on nitrogen excretion patterns and postprandial plasma urea profiles in grower pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 80:3238–3246. doi: 10.2527/2002.80123238x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zervas S., and Zijlstra R. T.. 2002b. Effects of dietary protein and fermentable fiber on nitrogen excretion patterns and plasma urea in grower pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 80:3247–3256. doi: 10.2527/2002.80123247x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. 1994. Swine building ventilation – a guide to confinement swine housing in cold climates. Prairie Swine Centre Inc., Saskatoon, SK: http://www.prairieswine.com(Accessed 10 March 2018). [Google Scholar]

- Zijlstra R. T., Jha R., Woodward A. D., Fouhse J., and van Kempen T. A.. 2012. Starch and fiber properties affect their kinetics of digestion and thereby digestive physiology in pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 90 (Suppl 4):49–58. doi: 10.2527/jas.53718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]