Abstract

Fescue toxicosis is a multifaceted syndrome common in cattle grazing endophyte-infected tall fescue and is detrimental to growth and performance. Recent research has shown that supplementing protein has the potential to enhance growth performance in weaned steers. Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate the effect of supplemental CP on physiological parameters in stocker steers experiencing fescue toxicosis. Thirty-six weaned Angus steers (6 mo of age) stratified by weight (196.1 ± 3.6 kg) were assigned to a 2 × 2 factorial arrangement for 56 d: endophyte-free (EF) seed and 14% CP (EF-14; n = 9), EF seed and 18% CP (EF-18; n = 9), endophyte-infected (EI) seed and 14% CP (EI-14; n = 9), and EI seed and 18% CP (EI-18; n = 9). Steer growth and hemodynamic responses were collected weekly during ergot alkaloid exposure. On day 14 of the trial, iButton temperature data loggers were subcutaneously inserted in the lateral neck region to record hourly body temperature for 42 d. Data were analyzed using PROC MIXED of SAS with repeated measures. No differences were observed in DMI, BW, ADG, F:G, or BCS during the treatment period (P > 0.05). Hair shedding scores, rectal temperatures, surface temperatures, and respiration rates were greater in EI steers compared to EF steers regardless of supplemental CP (P < 0.05). However, subcutaneous body temperature was greater in EI-14 steers (37.94 °C) compared to other steer groups (37.60, 37.68, 37.72 ± 0.04 °C for EF-14, EF-18, and EI-18, respectively; P < 0.05). Prolactin concentrations tended to be greater in EF steers when compared to EI steers (P = 0.07). Heart rate and hematocrit were reduced for EI-18 steers compared to other steer groups (P < 0.05). Caudal artery diameter was reduced in EI-18 steers compared to EI-14 steers (2.60 vs. 2.75 ± 0.05 mm, respectively; P < 0.05) and caudal vein diameter was reduced in EI-18 steers (3.20 mm) compared to all other steer groups (3.36, 3.39, 3.50 mm for EF-14, EF-18, and EI-14, respectively; P < 0.05). However, there was no difference observed in systolic or diastolic blood pressure during the treatment period (P > 0.05). Based on the data, exposure to low to moderate levels of ergot alkaloids during the stocker phase had a negative impact on hemodynamic responses and supplemental CP had minimal impact to alleviate symptoms. Therefore, feeding additional protein above established requirements is not expected to help alleviate fescue toxicosis.

Keywords: fescue toxicosis, growth, hemodynamics, stocker steers

INTRODUCTION

Cow–calf operations constitute as the primary beef production system in the Southeast (USDA NASS, 2012). Weaned calves from cow–calf operations are generally placed into a backgrounding program until a sufficient body weight is met for feedlot entry. With forage being the major dietary component for animals in the cow–calf and stocker systems (Allen et al., 2000), stocker production on the same land can improve profitability for Southeastern beef production.

Tall fescue (Lolium arundinaceum [Schreb.] Darbysh.) is the predominant forage utilized in the Southeast (Ball et al., 2007), and would be a viable option for stocker grazing. However, fescue toxicosis is a result of cattle grazing endophyte (Epichloë coenophiala) infected tall fescue, specifically consuming ergot alkaloids. Vasoconstriction induced by ergot alkaloids interaction with biogenic amide receptors (Klotz et al., 2012; 2013) will reduce blood flow and negatively alter thermoregulation, thus an animal is unable to properly dissipate body heat (Aiken et al., 2007; McClanahan et al., 2008). Exposure to ergot alkaloids during the stocker phase could reduce nutrient intake, leading to compromised performance (Parish et al., 2003). Additionally, the altered thermoregulation could lead to hyperthermia in elevated ambient temperature, thus exacerbating these negative effects.

Increasing dietary concentration of nutrients, such as protein, can mitigate some of the animal performance lost during periods of reduced feed intake (Elizalde et al., 1998; Moriel et al., 2015). While calves experience reduced gains while grazing endophyte-infected tall fescue, supplemental protein has been shown to improve growth performance (Elizalde et al., 1998), however, there is minimal information pertaining to its impact on thermoregulation. Therefore, the aim of this study is to evaluate the effect of supplemental protein on growth and physiological responses of steer calves exposed to ergot alkaloids during the stocker phase.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was conducted at the Butner Beef Cattle Field Laboratory (BBCFL) in Bahama, NC, and was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at North Carolina State University (17-043-A).

Animals and Treatment

Steer performance and feed data were collected early May to early July 2017 (day 0 to 56). Angus steers (n = 36) grazing on novel endophyte (nontoxic) tall fescue pastures, were weaned, at approximately 6 mo of age, on 3 April 2017 (day −35) and maintained in a dry lot with ad libitum access to nontoxic fescue hay until the start of the trial. Steers were stratified by weight (196.1 ± 3.6 kg) and randomly assigned to 1 of 12 pens (3 steers/pen) within a slotted floor barn. The pens then were randomly assigned to receive either endophyte-infected fescue seed (EI; 185 µg ergovaline/kg of BW) or noninfected “endophyte-free” fescue seed (EF; control, 0 µg ergovaline/kg of BW) and were also randomly assigned to receive either no supplemental protein (100% NRC requirements; 14% CP) or soybean meal supplementation (18% CP) in a total mixed ration. Crude protein concentrations were selected based on previous research conducted at BBCFL (Moriel et al., 2015). Individual treatments were designated as follows: endophyte-free 14% CP (EF-14; n = 9), endophyte-free 18% CP (EF-18; n = 9), endophyte-infected 14% CP (EI-14; n = 9), and endophyte-infected 18% CP (EI-18; n = 9).

To monitor physiological responses of individual animals to ergot alkaloids; BW, BCS (scale of 1 to 9; adapted from Whitman, 1975), rectal temperature, surface temperature, heart rate, caudal blood pressure, respiration rate, caudal artery and vein diameter, and hematocrit were measured weekly as previously described in Poole et al. (2019). Surface temperature was accessed via thermal imaging camera (Fluke Ti45FT IR Flexcam, Fluke Corporation, Everett, WA). The steers had an 18 × 20 cm square clipped behind the left shoulder using a #10 blade. Each week, images were taken within the square and the highest, lowest, and average temperature were recorded (SmartView 3.5 Thermal Imager Software; Poole et al., 2019; Supplementary Fig. 1). Heart rate and caudal blood pressure were measured three times for each steer weekly using a 16 to 24 cm blood pressure cuff (LifeSource A&D Engineering Inc., San Jose, CA). The tail was held steady during these measurements to minimize variation. Caudal artery and vein diameter were measured using Doppler ultrasonography (M-Turbo, SonoSite Inc, Bothell, WA). Hair coat scores (HCS; adapted from Olson et al., 2003) and hair coat shedding scores [HSS; scale of 1 (slick summer coat) to 5 (full winter coat); adapted from Gray et al., 2011] were collected by 2 trained technicians weekly and composited.

On day 14 of the trial, a calibrated iButton temperature data logger was surgically inserted into the lateral neck region of each steer as reported by Lee et al. (2016). Steers were temporarily restrained, hair-clipped, and locally anesthetized with 10 mL of 2% lidocaine in the lateral neck region. A 2 to 3 cm long incision was made in the skin and undermined to make subcutaneous pocket, temperature data loggers were inserted and then skin was sutured with a medical stapler. The temperature data loggers were recovered by surgery following the procedure above at the end of the feeding period (day 56). The temperature data loggers were set to record the subcutaneous body temperature every hour. Overall retention rate was 86% (EF-14: 8/9, EF-18: 7/9, EI-14: 8/9, EI-18: 8/9). For analysis, subcutaneous body temperature was averaged for the treatment period as well as two 7-day intervals during the treatment period: Period 1 being day 15 to 22 and Period 2 being day 49 to 56.

Temperature and Temperature Humidity Index (THI)

Ambient temperature and humidity were collected weekly during data collection. Additionally, records were obtained from the National Weather Service Henderson Oxford Airport station, approximately 40 km from BBCFL (Fig. 1). Temperature-humidity index (THI, Buffington et al., 1977) was calculated using the formula:

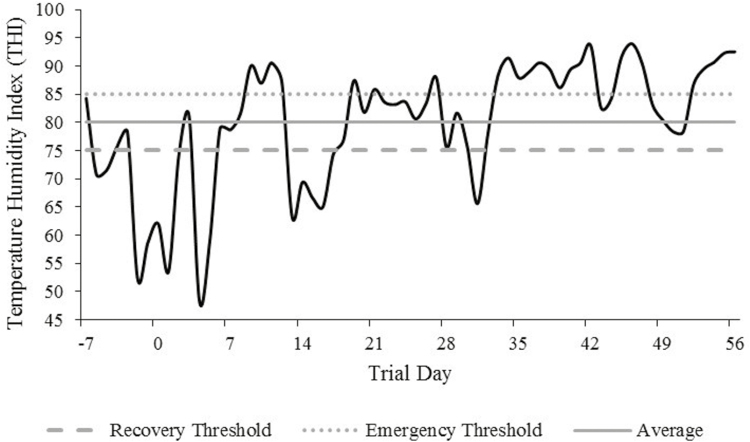

Figure 1.

Environmental temperature humidity index (THI) retrieved daily at noon from early-May to early July 2017. THI = Tdb – [0.55−(0.55 × RH/100) × (Tdb – 58)]; Tdb = dry bulb temperature (°F), and RH = relative humidity. Recovery (nonlife threatening, 75) and emergency (high risk, 85) thresholds as described by Hahn (1999). Average represents the overall average THI (80) throughout the duration of the trial.

Where Tdb represents dry bulb temperature (°F) and RH represents relative humidity.

Diet

The 14% CP diets consisted of a corn silage total mixed ration (TMR) made up of 61.45% corn silage, 11.75% soybean meal, 13.75% fescue seed (EF or EI), 8.75% ground corn, 3.8% commodity pellets, 0.3% trace mineral salt, and 0.2% limestone on a DM basis. The 18% CP diets consisted of 61.45% corn silage, 20.5% soybean meal, 13.75% fescue seed (EF or EI), 3.8% commodity pellets, 0.3% trace mineral salt, and 0.2% limestone on a DM basis. Diets were formulated according to National Research Council (1996) requirements for 1 kg/d ADG at a feed intake of 2.35% of body weight to prevent refusals. Limit feeding to prevent refusals was designed to reduce ergot alkaloid and protein intake variation. Feed offering was adjusted weekly based on average pen BW and silage DM. Cattle were provided ad libitum access to fresh water. Samples of TMR from each treatment were collected every 28 d, composited, and submitted to be analyzed for nutrient content (Cumberland Valley Analytical Services, Waynesboro, PA; Table 1). When refusals were present, they were weighed weekly to calculate actual DMI and visually assessed for presence of fescue seed, in which none was detected.

Table 1.

Nutritional composition of diets

| Item | Treatments1,2,3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EF-14 | EF-18 | EI-14 | EI-18 | |

| DM % | 43.9 | 42.3 | 42.0 | 42.4 |

| CP %DM | 13.7 | 15.3 | 12.3 | 15.8 |

| NDF %DM | 34.0 | 38.0 | 35.6 | 36.8 |

| ADF %DM | 19.5 | 23.5 | 21.4 | 21.4 |

| TDN %DM4 | 71.5 | 68.8 | 71.3 | 69.8 |

| Ash %DM | 5.00 | 5.51 | 4.61 | 5.45 |

| Ca %DM | 0.58 | 0.61 | 0.53 | 0.62 |

| P %DM | 0.34 | 0.35 | 0.30 | 0.34 |

| Mg %DM | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.23 | 0.25 |

| Na %DM | 0.22 | 0.27 | 0.23 | 0.28 |

| K %DM | 1.01 | 1.18 | 1.00 | 1.18 |

| Cu ppm | 20 | 22 | 19 | 23 |

| Fe ppm | 291 | 307 | 275 | 307 |

| Mn ppm | 55 | 60 | 50 | 55 |

| Zn ppm | 61 | 68 | 58 | 63 |

1EF-14: endophyte-free 14% crude protein; EF-18: endophyte-free 18% crude protein; EI-14: endophyte-infected 14% crude protein; EI-18: endophyte-infected 18% crude protein

2TMR composition for 14% CP (DM basis): 61.45% corn silage, 11.75% soybean meal, 13.75% fescue seed (EF or EI), 8.75% ground corn, 3.8% commodity pellets, 0.3% trace mineral salt, and 0.2% limestone

3TMR composition for 18% CP (DM basis): 61.45% corn silage, 20.5% soybean meal, 13.75% fescue seed (EF or EI), 3.8% commodity pellets, 0.3% trace mineral salt, and 0.2% limestone

4TDN = 92.5135 – (0.7965 × ADF)

Piedmont Tall Fescue seed was added into the EI TMR (Southern States Cooperative, Richmond, VA), while Cajun II Tall Fescue seed was added to the EF TMR (King’s Agri Seed Inc., Ronks, PA) and contained 0 µg/kg total ergot alkaloid (Agrinostics, Ltd., Watkinsville, GA). Based on previous data (Poole et al., 2019), 500 µg/kg ergovaline was targeted for the EI diets, however subsequent analysis of the seed for ergovaline (MU Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Lab; Rottinghaus, 1993) showed that the EI TMRs contained 185 µg/kg ergovaline, the EF TMR contained 0 µg/kg ergovaline. Ergovaline was the only ergot alkaloid detected in these samples.

Blood Sampling and Prolactin Assay

Blood samples were collected from the jugular vein into 10-mL sterile serum blood collection tubes without additive (Vacutainer; Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Blood samples were immediately placed on ice and later centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. The serum was transferred into 5 mL polystyrene vials (BD Falcon, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and stored at −80 °C for analysis.

Serum concentrations of prolactin (PRL) were analyzed on day 0, 14, 28, 42, and 56 for each individual animal. Sample concentrations were determined by a commercially available Bovine Prolactin ELISA kit (MyBioSource; San Diego, CA) and were previously validated in this lab (Poole et al., 2018). A sample control was included in each assay replicate. The interassay coefficient of variation based on the duplicate sample controls was 10.03%, and the intra-assay coefficient of variation was 4.95%.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using the MIXED procedure of SAS 9.3 (SAS Inst. Inc., 1996) with repeated measures. Experimental unit for feeding measurements (i.e., ADG, DMI, and F:G) was pen, while experimental unit for physiological measurements and PRL analysis was individual animal. The model for performance data included fescue treatment (EF vs. EI), protein (14% vs. 18%), sample collection time, and interactions. Results were recorded as least squares means ± SEM. Terms with a significance value of P > 0.20 were removed from the complete model in a stepwise manner to derive the final reduced model for each variable. A statistical significance was reported at a P ≤ 0.05. A tendency was reported at a P > 0.05 and ≤ 0.10.

RESULTS

Animal Performance

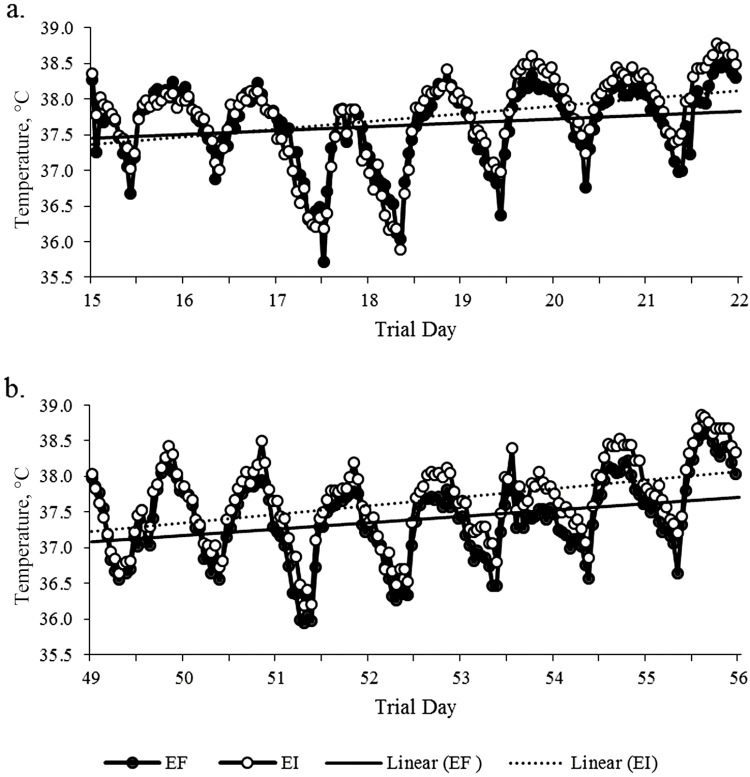

All animal performance data are summarized in Table 2. The DMI was uniform across treatments and no differences were observed in BW, ADG, F:G, or BCS. While HCS tended to differ between fescue treatments (P = 0.06), HSS was greater in EI steers compared to EF steers (4.49 vs. 4.36 ± 0.04, respectively; P < 0.05). Respiratory rate was increased in EI steers when compared to EF steers (56.5 vs. 52.5 ± 1.6 breaths/min, respectively; P < 0.05). Rectal temperatures were elevated in EI steers compared to EF steers (39.7 vs. 39.5 ± 0.06 °C, respectively; P < 0.05). Surface temperatures were also elevated for EI steers compared to EF steers (32.5 vs. 32.2 ± 0.13 °C, respectively; P < 0.05). Surface temperatures were also affected by protein supplementation with steers fed 14% CP having an increased temperature than steers fed 18% CP (32.6 and 32.1 ± 0.13 °C, respectively; P < 0.001). Additionally, there was a treatment interaction with EI-14 steers having greater overall subcutaneous body temperature compared to other steer groups (P < 0.05). There was no difference in subcutaneous body temperature by fescue treatment in Period 1 (37.64 vs. 37.74 ± 0.05 °C for EF and EI, respectively; P = 0.13; Fig. 2a). However, there was a difference by fescue treatment in Period 2 with subcutaneous body temperatures being elevated in EI steers compared to EF steers (37.65 vs. 37.39 ± 0.04 °C, respectively; P < 0.0001; Fig. 2b). In regards to prolactin concentrations, EI steers tended to have reduced concentrations when compared to EF steers (176.3 vs. 203.0 ± 14.7 ng/mL, respectively; P = 0.07). However, there were no differences by CP supplementation.

Table 2.

Physiological parameters for beef steers consuming either endophyte-free (EF) or endophyte-infected (EI) fescue with 14% crude protein (14) or 18% crude protein (18) from early May to early July 2017

| Item | Treatment1,2 | P-value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EF-14 | EF-18 | EI-14 | EI-18 | SEM | Fescue | Protein | Interaction | |

| Initial BW, kg | 191.0 | 191.9 | 195.8 | 192.5 | 6.8 | 0.695 | 0.863 | 0.761 |

| Final BW, kg | 242.1 | 245.4 | 242.7 | 243.9 | 7.8 | 0.957 | 0.776 | 0.895 |

| ADG, kg/d | 0.91 | 0.96 | 0.84 | 0.92 | 0.07 | 0.381 | 0.355 | 0.782 |

| DMI, kg/d3 | 5.03 | 5.10 | 5.09 | 5.08 | 0.05 | 0.701 | 0.570 | 0.541 |

| Feed:Gain4 | 5.68 | 5.41 | 6.15 | 5.60 | 0.26 | 0.209 | 0.125 | 0.594 |

| BCS5 | 4.88 | 4.93 | 4.93 | 4.93 | 0.03 | 0.493 | 0.379 | 0.328 |

| HCS6 | 4.54a | 4.50ab | 4.61ac | 4.56a | 0.04 | 0.062† | 0.286 | 0.790 |

| HSS7 | 4.36a | 4.35a | 4.56b | 4.42a | 0.04 | 0.022* | 0.442 | 0.756 |

| Rectal temp., °C | 39.6a | 39.4b | 39.7a | 39.7a | 0.06 | 0.005* | 0.136 | 0.392 |

| Surface temp., °C | 32.3a | 32.0a | 32.8b | 32.2a | 0.13 | 0.011* | 0.001* | 0.185 |

| SubQ temp., °C8 | 37.60a | 37.68ab | 37.94c | 37.72b | 0.04 | <.0001* | 0.068† | 0.001* |

| Respiration rate | 52.6a | 52.3a | 55.8ab | 57.2b | 1.61 | 0.012* | 0.747 | 0.597 |

| PRL conc., ng/mL | 203.9a | 202.1a | 186.4ab | 166.3b | 14.8 | 0.072† | 0.455 | 0.534 |

a,b,cWithin row, means without a common superscript significantly differ (P ≤ 0.05).

1Values are reported as least square means for the experiment.

2EF-14: endophyte-free 14% crude protein; EF-18: endophyte-free 18% crude protein; EI-14: endophyte-infected 14% crude protein; EI-18: endophyte-infected 18% crude protein.

3Expressed as average DMI/pen/d.

4Calculated by dividing DMI/pen/d and ADG.

5BCS = body condition score (1–9 scale).

6HCS = hair coat score (1–5 scale).

7HSS = hair shedding score (1–5 scale).

8Subcutaneous body temperature averaged from day 14 to 56 of the trial.

*P-values <0.05 determined significant.

† P-values 0.05>P≤0.10 determined a statistical tendency.

Figure 2.

Subcutaneous temperatures recorded by iButton temperature data loggers for steers consuming endophyte-free fescue seed (black circles and solid trend line, EF; n = 15) or endophyte-infected fescue seed (open circles and dashed trend line, EI; n = 16) every hour for two 7-d periods: (a) Period 1 being day 15 to 22 and (b) Period 2 being day 49 to 56.

Hemodynamic Responses

All hemodynamic measurement data are summarized in Table 3. There was a treatment interaction with EI-18 steers having a slower heart rate compared to other steer groups (P < 0.05). For caudal artery diameter, there was a treatment interaction with EI-18 steers having a decreased diameter when compared to EI-14 steers (P < 0.05), however, there was no difference when compared to EF-14 and EF-18 steers (P > 0.05). However, caudal vein diameter was decreased in EI-18 steers when compared to all other steer groups (P < 0.05). Systolic and diastolic blood pressure did not differ between steer groups (P > 0.05). Finally, there was an interaction with hematocrit being reduced in EI-18 steers when compared to EF-18 and EI-14 steers (P < 0.05), however, there was no difference when compared to EF-14 steers (P > 0.05).

Table 3.

Hemodynamic responses for beef steers consuming either endophyte-free (EF) or endophyte-infected (EI) fescue with 14% crude protein (14) or 18% crude protein (18) from early May to early July 2017

| Item | Treatment1,2 | P-value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EF-14 | EF-18 | EI-14 | EI-18 | SEM | Fescue | Protein | Interaction | |

| Heart rate | 93.2a | 94.8ab | 98.0b | 88.0c | 1.66 | 0.258 | 0.003* | 0.007* |

| Artery diam., mm | 2.63b | 2.68ab | 2.75a | 2.60b | 0.05 | 0.652 | 0.297 | 0.028* |

| Vein diam., mm | 3.36a | 3.39a | 3.50a | 3.20b | 0.06 | 0.735 | 0.037* | 0.010* |

| Systolic BP3, mmHg | 143.2 | 142.0 | 137.7 | 142.2 | 3.3 | 0.426 | 0.628 | 0.386 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | 63.8 | 66.3 | 61.8 | 59.1 | 2.9 | 0.110 | 0.971 | 0.371 |

| Hematocrit4 | 33.2ab | 33.6a | 34.0a | 32.7b | 0.33 | 0.910 | 0.128 | 0.009* |

a,bWithin row, means without a common superscript significantly differ (P ≤ 0.05).

1Values are reported as least square means for the experiment.

2EF-14: endophyte-free 14% crude protein; EF-18: endophyte-free 18% crude protein; EI-14: endophyte-infected 14% crude protein; EI-18: endophyte-infected 18% crude protein.

3BP = blood pressure.

4Hematocrit is represented by the percentage of packed red cells in blood.

*P-values <0.05 determined significant.

† P-values 0.05>P≤0.10 determined a statistical tendency.

DISCUSSION

Retaining calves after weaning as stocker cattle on pastures has the potential to enhance animal welfare, stocking rates, and the value of calves; thus, improving profitability for Southeastern beef production (Allen et al., 1992; Price et al., 2003; Guretzky et al., 2005). With the abundant supply of calves and availability of forage in the Southeast, this would be a viable region for stocker production. Unfortunately, endophyte-infected tall fescue is a prominent forage in this region and has adverse effects on cattle performance (Schmidt and Osborn, 1993; Strickland et al., 2009), thus may negate the value of stocker production. It has been previously shown that fescue seed (3,910 µg/kg ergovaline) can reduce ADG even when DMI remains the same in a confinement setting (Poole et al., 2018). However, when feed intake was held at a consistent percent of BW, fescue seed intake did not alter DMI, ADG, or F:G in the present study. Supplemental protein can improve growth performance of calves postweaning (Moriel et al., 2015), and improve gains in steers grazing endophyte-infected tall fescue (Elizalde et al., 1998). Contrary to this, the current study showed no protein benefit on DMI, ADG, or F:G in the confinement setting. However, few studies have noted similar observations in beef calves (Smith et al., 1987; Wilson et al., 2014). It is important to note that ergovaline concentrations in the current study were reduced (185 µg/kg ergovaline) when compared to previous studies (Poole et al., 2018) and typical concentrations observed in pasture during the summer months (Rottinghaus et al., 1991). While low to moderate levels of ergovaline were used in the current study, previous reports effectively induced symptoms of fescue toxicosis at 20 and 40 μg ergovaline/kg BW/d to 150 µg/kg BW/d of ergovaline (Roberts et al., 2009; Spiers et al., 2012, respectively); therefore, a mild degree of fescue toxicosis was induced in the current study. Interestingly, Lyons et al. (2016) demonstrated that protein supplementation to heifers grazing stockpiled KY-31 tall fescue at low ergovaline concentrations (ranging from 24 to 162 µg/kg ergovaline) in the winter months does improve ADG. Therefore, protein supplementation may be beneficial in a pasture setting where ergovaline concentrations vary and DMI is not regulated. Ultimately, it was concluded in the current study that by limit feeding, DMI remained the same across treatments and allowed for accurate evaluation of the utilization of nutrients on other performance parameters without the confounding effects of reduced nutrient intake. Furthermore, BCS did not differ between treatment groups. Typically, DMI is reduced in cattle consuming endophyte-infected tall fescue diets (Paterson et al., 1995), thus contributing to loss in body condition. Therefore, because there were no differences observed in DMI, BCS would not be expected to differ.

A common symptom of fescue toxicosis is cattle exhibit a retained and rough hair coat (Strickland et al., 2011). Although the mechanism of this physiological effect is not well understood, it is known that the retained hair coat exacerbates heat stress-like symptoms during the summer months. While there were no drastic differences in hair shedding observed between treatment groups, EI steers did have greater HSS scores when compared to EF steers throughout the trial, with a greater score indicating a retained, rough hair coat. In addition to HSS, EI steers tended to have reduced prolactin concentrations, and had elevated rectal temperatures and respiration rates when compared to EF steers, all being typical symptoms exhibited in cattle suffering from heat stress and/or fescue toxicosis (Osborn, 1988; Aldrich et al., 1993; Al-Haidary et al., 2001). Specifically, EI-18 steers had a greater respiration rate when compared to both EF steer groups, however, EI-14 steers did not differ. In order for cattle to properly dissipate excess body heat during heat stress conditions, the thermoregulatory center within the hypothalamus will trigger a vasodilation response to the peripheral tissues (Curtis, 1983), thus increasing skin surface temperatures. Therefore, EI-14 steers exhibited the highest skin surface temperature of all steer groups and greatest overall subcutaneous body temperature when compared to other steer groups. In combination with reduced respiration rates, this would indicate that the EI-14 steers were able to properly dissipate excess body heat. However, skin temperatures were not elevated in EI-18 steers and this group experienced the greatest respiration rate. This would indicate an inability to dissipate body heat via evaporative cooling and that these steers would heavily rely on panting to reduce body temperature. As previously mentioned, EI steers experienced greater HSS and had elevated rectal temperatures, thus displaying heat stress-like symptoms. It has been demonstrated that dairy cattle under heat stress experience a negative energy balance due to reduced feed intake (Higginbotham et al., 1989), thus would have a reduction in nutrient (i.e., protein) intake. However, in the present study with beef cattle, DMI did not differ between treatment groups, and thus too much dietary protein could result in excessive conversion of ammonia to urea and/or ammonia toxicity which can have negative effects on numerous biological functions (Visek, 1984). Hence, this could be one explanation for the results observed in the EI-18 steers.

Physiological symptoms of fescue toxicosis arise approximately 21 d postexposure to ergot alkaloids as indicated by a reduction in prolactin secretion, urinary excretion of ergot alkaloids, and vasoconstriction (Hill et al., 2000; Klotz et al., 2016). Similarly, in the present study, there was no difference in subcutaneous body temperature during Period 1 (day 15 to day 22 of the trial). In agreement, as the trial progressed the EI steers had significantly increased subcutaneous body temperature during Period 2 (day 49 to day 56 of the trial) indicating that the low to moderate concentration of ergovaline from the seed consumed was sufficient to induce mild symptoms associated with fescue toxicosis (Supplementary Fig. 1). Ultimately, this demonstrates that when ambient temperatures begin to increase after fescue toxicosis has been established, signs and repercussions of this syndrome are amplified.

Interestingly, there were no differences in hemodynamic responses (i.e., heart rate, blood pressure, blood vessel diameter, and hematocrit) solely by fescue treatment. However, there were interactions between the fescue and protein treatments on some hemodynamic responses. As the trial progressed, EI-18 steers had a significant reduction in heart rate when compared to other steer groups. There have been varying reports regarding the impact of fescue toxicosis on heart rate. Numerous findings report that endophyte-infected fescue reduces heart rate (Browning and Leite-Browning, 1997; Aiken et al., 2007; Koontz et al., 2012; Eisemann et al., 2014), while others observe no differences (Rhodes et al., 1991; Poole et al., 2018). However, a reduction in heart rate is typically associated with fescue toxicosis and it has been shown to be independent of ambient temperature. Specifically, Osborn (1988) showed that steers on an EI diet had reduced heart rates in thermoneutral [21 °C; 53 vs. 70 beats per minute (bpm)] and heat stress (32 °C; 49 vs. 65 bpm) conditions when compared to steer on EF diets. Therefore, the reduction in heart rate observed by EI-18 can be attributed to fescue toxicosis rather than a rise in ambient temperature throughout the trial. Additionally, EI-18 steers displayed vasoconstriction of the caudal artery and vein compared to EI-14 steers. This is a well-documented symptom of fescue toxicosis (McCollough et al., 1994; Aiken et al., 2007; Poole et al., 2018) and this could indicate a reduction in blood flow to the extremities. While there was no difference observed in blood pressure, this could be explained by the synonymous reduction in both heart rate and blood vessel diameter in EI-18 steers. The final hemodynamic measurement, hematocrit, is the proportion of blood that consists of red blood cells and is an indicator of dehydration (Nordenson, 2006). Hematocrit values were significantly reduced in EI-18 steers, specifically when compared to EI-14 steers, and this would indicate that the EI-18 steers were overhydrating in attempt to cool down.

In the current study, supplemental protein did not reduce the physiological symptoms of mild exposure to ergovaline, and hemodynamic responses worsened in steers fed 18% CP. Controlling intake at 2.35% of body weight in the current study may have negated the beneficial effect of protein supplementation observed in grazing studies, which report reduced intake as a result of exposure to endophyte-infected fescue. Taken together, weaned calves consuming endophyte-infected tall fescue with the addition of supplemental protein may not be viable option for beef cattle producers in a confined feeding operation. However, it is important to note that in a pasture setting, cattle grazing endophyte-infected tall fescue experience a reduction in nutrient intake and supplementation could ensure that nutrient requirements are met. Therefore, further research is necessary to elucidate if other cost-effective supplemental programs are available to mitigate symptoms of fescue toxicosis and improve stocker grazing on endophyte-infected tall fescue.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Greg Shaeffer, Thomas Cobb, and the rest of the Butner crew (Butner Beef Cattle Field Laboratory, Bahama, NC) for their consistent help with animal care. The authors thank Kyle J. Mayberry, McKayla A. Newsome, Grace C. Ott, and Matthew Davis for all their help with data collection and laboratory analysis. The authors also thank the North Carolina Cattlemen’s Association and Hatch Project 02420 for providing the funds to conduct this study.

LITERATURE CITED

- Aiken G. E., Kirch B. H., Strickland J. R., Bush L. P., Looper M. L., and Schrick F. N.. 2007. Hemodynamic responses of the caudal artery to toxic tall fescue in beef heifers. J. Anim. Sci. 85:2337–2345. doi: 10.2527/jas.2006-821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldrich C. G., Paterson J. A., Tate J. L., and Kerley M. S.. 1993. The effects of endophyte-infected tall fescue consumption on diet utilization and thermal regulation in cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 71:164–170. doi: 10.2527/1993.711164x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Haidary A., Spiers D. E., Rottinghaus G. E., Garner G. B., and Ellersieck M. R.. 2001. Thermoregulatory ability of beef heifers following intake of endophyte-infected tall fescue during controlled heat challenge. J. Anim. Sci. 79:1780–1788. doi: 10.2527/2001.7971780x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen V. G., Fontenot J. P., and Notter D. R.. 1992. Forage systems for beef production from conception to slaughter: II. Stocker systems. J. Anim. Sci. 70:588–596. doi: 10.2527/1992.702588x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen V. G., Fontenot J. P., and Brock R. A.. 2000. Forage systems for production of stocker steers in the upper south. J. Anim. Sci. 78:1973–1982. doi: 10.2527/2000.7871973x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball D. M., Hoveland C. S., and Lacefield G. D.. 2007. Overview of southern forages. In: Southern forages: Modern concepts for forage crop management. 4th ed. IPNI, Norcross, GA: p. 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Browning R. Jr, and Leite-Browning M. L.. 1997. Effect of ergotamine and ergonovine on thermal regulation and cardiovascular function in cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 75:176–181. doi: 10.2527/1997.751176x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffington D. E. 1977. Black globe-humidity comfort index for dairy cows. In: Winter meeting of the American Society of Agricultural Engineers, St. Joseph. Trans. Am. Soc. Agric. Eng pp. 4517. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis S. E. 1983. Environmental management in animal agriculture. Iowa State University Press, Ames, IA: p. 47–96. [Google Scholar]

- Eisemann J. H., Huntington G. B., Williamson M., Hanna M., and Poore M.. 2014. Physiological responses to known intake of ergot alkaloids by steers at environmental temperatures within or greater than their thermoneutral zone. Front. Chem. 2:96. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2014.00096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elizalde J. C., Cremin J. D. Jr, Faulkner D. B., and Merchen N. R.. 1998. Performance and digestion by steers grazing tall fescue and supplemented with energy and protein. J. Anim. Sci. 76:1691–1701. doi: 10.2527/1998.7661691x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guretzky N. A., Russell J. R., Strohbehn D. R., and Morrical D. G.. 2005. Grazing and feedlot performance of yearling stocker cattle integrated with spring- and fall-calving beef cows in a year-round grazing system. J. Anim. Sci. 83:2696–2704. doi: 10.2527/2005.83112696x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray K. A., Smith T., Maltecca C., Overton P., Parish J. A., and Cassady J. P.. 2011. Differences in hair coat shedding, and effect on calf weaning weight and BCS among Angus dams. Livest. Sci. 140:68–71. doi: 10.1016/j/livesci.2011.02.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn G. L. 1999. Dynamic response of cattle to thermal heat loads. J. Anim. Sci. 77:10–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higginbotham G. E., Torabi M., and Huber J. T.. 1989. Influence of dietary protein concentration and degradability on performance of lactating cows during hot environmental temperatures. J. Dairy Sci. 72:2554–2564. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(89)79396-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill N. S., Thompson F. N., Stuedemann J. A., Dawe D. L., and Hiatt E. E. 3rd. 2000. Urinary alkaloid excretion as a diagnostic tool for fescue toxicosis in cattle. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 12:210–217. doi: 10.1177/104063870001200303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klotz J. L., Aiken G. E., Johnson J. M., Brown K. R., Bush L. P., and Strickland J. R.. 2013. Antagonism of lateral saphenous vein serotonin receptors from steers grazing endophyte-free, wild-type, or novel endophyte-infected tall fescue. J. Anim. Sci. 91:4492–4500. doi: 10.2527/jas.2012-5896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klotz J. L., Aiken G. E., Bussard J. R., Foote A. P., Harmon D. L., Goff B. M., Schrick F. N., and Strickland J. R.. 2016. Vasoactivity and vasoconstriction changes in cattle related to time off toxic endophyte-infected tall fescue. Toxins 8:271. doi: 10.3390/toxins8100271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klotz J. L., Brown K. R., Xue Y., Matthews J. C., Boling J. A., Burris W. R., Bush L. P., and Strickland J. R.. 2012. Alterations in serotonin receptor-induced contractility of bovine lateral saphenous vein in cattle grazing endophyte-infected tall fescue. J. Anim. Sci. 90:682–693. doi: 10.2527/jas.2011-4323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koontz A. F., Bush L. P., Klotz J. L., McLeod K. R., Schrick F. N., and Harmon D. L.. 2012. Evaluation of a ruminally dosed tall fescue seed extract as a model for fescue toxicosis in steers. J. Anim. Sci. 90:914–921. doi: 10.2527/jas.2011-4292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y., Bok J. D., Lee H. J., Lee H. G., Kim D., Lee I., Kang S. K., and Choi Y. J.. 2016. Body temperature monitoring using subcutaneously implanted thermologgers from Holstein steers. AJAS 29:299–306. doi: 10.5713/ajas.15.0353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons S. E., Shaeffer A. D., Drewnoski M. E., Poore M. H., and Poole D. H.. 2016. Effect of protein supplementation and forage allowance on the growth and reproduction of beef heifers grazing stockpiled tall fescue. J. Anim. Sci. 94:1677–1688. doi: 10.2527/jas.2015-9969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClanahan L. K., Aiken G. E., and Dougherty C. T.. 2008. Case study: Influence of rough hair coats and steroid implants on the performance and physiology of steers grazing endophyte-infected tall fescue in the summer. The Professional Animal Scientist 24:269–276. [Google Scholar]

- McCollough S. F., Piper E. L., Moubarak A. S., Johnson Z. B., Petroski R. J., and Flieger M.. 1994. Effect of tall fescue ergot alkaloids on peripheral blood flow and serum prolactin in steers. J. Anim. Sci. 72(Suppl. 1):144.8138483 [Google Scholar]

- Moriel P., Artioli L. F., Poore M. H., Confer A. W., Marques R. S., and Cooke R. F.. 2015. Increasing the metabolizable protein supply enhanced growth performance and led to variable results on innate and humoral immune response of preconditioning beef steers. J. Anim. Sci. 93:4473–4485. doi: 10.2527/jas.2015-9238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council 1996. Nutrient requirements of beef cattle, 7th Rev. Edn. National Academy Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Nordenson N. 2006. Gale encyclopedia of medicine. 3rd ed. Gale Group, Detroit, MI. [Google Scholar]

- Olson T. A., Lucena C., Chase C. C. Jr, and Hammond A. C.. 2003. Evidence of a major gene influencing hair length and heat tolerance in Bos taurus cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 81:80–90. doi: 10.2527/2003.81180x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn T. G. 1988. Effect of consuming fungus-infected and fungus-free tall fescue and ergotamine tartrate on certain physiological variables of cattle in environmentally-controlled conditions. M.S. Thesis. Auburn University, AL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parish J. A., McCann M. A., Watson R. H., Paiva N. N., Hoveland C. S., Parks A. H., Upchurch B. L., Hill N. S., and Bouton J. H.. 2003. Use of nonergot alkaloid-producing endophytes for alleviating tall fescue toxicosis in stocker cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 81:2856–2868. doi: 10.2527/2003.81112856x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson J., Forcherio C., Larson B., Samford M., and Kerley M.. 1995. The effects of fescue toxicosis on beef cattle productivity. J. Anim. Sci. 73:889–898. doi: 10.2527/1995.733889x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole R. K., Devine T. L., Mayberry K. J., Eisemann J. H., Poore M. H., Long N. M., and Poole D. H.. 2019. Impact of slick hair trait on physiological and reproductive performance in beef heifers consuming ergot alkaloids from endophyte-infected tall fescue1. J. Anim. Sci. 97:1456–1467. doi: 10.1093/jas/skz024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole D. H., Lyons S. E., Poole R. K., and Poore M. H.. 2018. Ergot alkaloids induce vasoconstriction of bovine uterine and ovarian blood vessels. J. Anim. Sci. 96:4812–4822. doi: 10.1093/jas/sky328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price E. O., Harris J. E., Borgward R. E., Sween M. L., and Connor J. M.. 2003. Fenceline contact of beef calves with their dams at weaning reduces the negative effects of separation on behavior and growth rate. J. Anim. Sci. 81:116–121. doi: 10.2527/2003.811116x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes M. T., Paterson J. A., Kerley M. S., Garner H. E., and Laughlin M. H.. 1991. Reduced blood flow to peripheral and core body tissues in sheep and cattle induced by endophyte-infected tall fescue. J. Anim. Sci. 69:2033–2043. doi: 10.2527/1991.6952033x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts C. A., Kallenbach R. L., Hill N. S., Rottinghaus G. E., and Evans T. J.. 2009. Ergot alkaloid concentrations in tall fescue hay during production and storage. Crop Sci. 49:1496–1502. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2008.08.0453 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rottinghaus G. E., Garner G. B., Cornell C. N., and Ellis J. L.. 1991. HPLC method for quantitating ergovaline in endophyte-infested tall fescue: Seasonal variation of ergovaline levels in stems with leaf sheaths, leaf blades and seed heads. J. Agric. Food Chem. 39:112–115. [Google Scholar]

- Rottinghaus G. E., Schultz L. M., Ross P. F., and Hill N. S.. 1993. An HPLC method for the detection of ergot in ground and pelleted feeds. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 5:242–247. doi: 10.1177/104063879300500216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS. 1996. SAS system for mixed models. SAS Inst. Inc., Cary, NC. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt S. P. and Osborn T. G.. 1993. Effects of endophyte-infected tall fescue on animal performance. Agr Ecosyst Environ 44:233–262. [Google Scholar]

- Smith W. L., Gay N., Boling J. A., and Muntifering R. B.. 1987. Growth and metabolism of growing beef calves fed tall fescue haylage supplemented with protein and(or) energy. J. Anim. Sci. 65:1094–1100. doi: 10.2527/jas1987.6541094x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiers D. E., Wax L. E., Eichen P. A., Rottinghaus G. E., Evans T. J., Keisler D. H., and Ellersieck M. R.. 2012. Use of different levels of ground endophyte-infected tall fescue seed during heat stress to separate characteristics of fescue toxicosis. J. Anim. Sci. 90:3457–3467. doi: 10.2527/jas.2012-5099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland J. R., Aiken G. E., Spiers D. E., Fletcher L. R., and Oliver J. W.. 2009. Physiological basis of fescue toxicosis. Chapter 12; pp. 203–227. In: Fribourg H. A., Hannaway D. B., and West C. P., editors. Tall fescue for the twenty-first century. Agronomy Monographs 53. ASA, CSSA, SSSA, Madison, WI. [Google Scholar]

- Strickland J. R., Looper M. L., Matthews J. C., Rosenkrans C. F. Jr, Flythe M. D., and Brown K. R.. 2011. Board-invited review: St. Anthony’s Fire in livestock: Causes, mechanisms, and potential solutions. J. Anim. Sci. 89:1603–1626. doi: 10.2527/jas.2010-3478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USDA NASS 2012. Census of Agriculture, Ag Census Web Maps.

- Visek W. J. 1984. Ammonia: Its effects on biological systems, metabolic hormones, and reproduction. J. Dairy Sci. 67:481–498. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(84)81331-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitman R. W. 1975. Weight change, body condition and beef-cow reproduction. Ph.D. Diss. Colorado State Univ, Fort Collins, CO. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson T. B., Milnamow M. R., West M. A., Faulkner D. B., Ireland F. A., and Shike D. W.. 2014. Grazing novel endophyte-infected fescue following grazing endophyte-infected fescue to alleviate fescue toxicosis in beef calves. J. Anim. Sci. 92(E Suppl. 2). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.