Abstract

The circadian glucocorticoid (GC) rhythm is dependent on a molecular clock in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) and an adrenal clock that is synchronized by the SCN. To determine whether the adrenal clock modulates GC responses to stress, experiments used female and male Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl knockout [side-chain cleavage (SCC)–KO] mice, in which the core clock gene, Bmal1, is deleted in all steroidogenic tissues, including the adrenal cortex. Following restraint stress, female and male SCC-KO mice demonstrate augmented plasma corticosterone but not plasma ACTH. In contrast, following submaximal scruff stress, plasma corticosterone was elevated only in female SCC-KO mice. Adrenal sensitivity to ACTH was measured in vitro using acutely dispersed adrenocortical cells. Maximal corticosterone responses to ACTH were elevated in cells from female KO mice without affecting the EC50 response. Neither the maximum nor the EC50 response to ACTH was affected in male cells, indicating that female SCC-KO mice show a stronger adrenal phenotype. Parallel experiments were conducted using female Cyp11B2 (Aldosterone Synthase)Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl mice and adrenal cortex–specific Bmal1-null (Ad-KO) mice. Plasma corticosterone was increased in Ad-KO mice following restraint or scruff stress, and in vitro responses to ACTH were elevated in adrenal cells from Ad-KO mice, replicating data from female SCC-KO mice. Gene analysis showed increased expression of adrenal genes in female SCC-KO mice involved in cell cycle control, cell adhesion–extracellular matrix interaction, and ligand receptor activity that could promote steroid production. These observations underscore a role for adrenal Bmal1 as an attenuator of steroid secretion that is most prominent in female mice.

Adrenal secretion of glucocorticoids (GCs), the primary output of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, is activated by stress and exhibits a circadian rhythm that provides optimal corticosteroid exposure throughout the day. The adrenal cortex expresses a molecular clock that induces the rhythmic expression of the clock-controlled gene, steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) (1), and has been implicated in gating adrenal sensitivity to ACTH (2). Although disruption of the adrenal molecular clock by Bmal1 knockdown (1) or deletion (3) has not altered GC responses to acute stress, previous examination of stress responses has been limited to experiments in male mice. Recent work has shown that the adrenal clock is sexually dimorphic, whereby female mouse adrenals show lower-amplitude clock gene rhythms in vitro compared with male adrenals (4), providing a foundation for examining whether adrenal clock genes contribute to sex-dependent GC responses to stress. To address this question, we have completed experiments using male and female Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl knockout (KO) mice. The Cyp11A1 gene encodes the cytochrome P450 side-chain cleavage (SCC) enzyme that is expressed in all steroidogenic tissue, so Bmal1 is deleted in the adrenal cortex and gonads (3). We also used female Cyp11B2 [P450 aldosterone synthase (AS)]Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl KO mice to produce Bmal1 deletion that is restricted to the adrenal cortex. Our recent work has shown that female ASCre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl KO mice maintain GC rhythms under normal light/dark photoperiods, but they have a hyperadrenocortical response to aberrant light exposure (5). Results of the current study show that Bmal1 deletion results in augmented GC responses to acute restraint stress in female and male mice, whereas only female KO mice showed increased GC responses to submaximal scruff stress. The hyperadrenocortical response also is observed in female but not male mice, at the cellular level, by increased corticosterone responses to ACTH in vitro. Based on Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis (6), female KO adrenals show uniquely increased expression of genes involved in cellular pathways that could result in hyperadrenocorticoidism, including cell cycle control, cell adhesion–extracellular matrix interactions, and ligand-receptor activity (7).

Methods

Animal welfare assurance

Mice (3 to 9 months old) bred in-house were housed on a 12-hour light/12-hour dark cycle (lights on at 6:00 am). Zeitgeber times (ZTs) of ZT0 and ZT12 were used as the lights-on and lights-off times, respectively. The light intensity at the surfaces of the cages was ∼500 lux. Mice were fed normal, commercial rodent chow and provided with water ad libitum. Prior to tissue collection, mice were humanely euthanized by decapitation and all efforts were made to minimize suffering. Animals were maintained and cared for in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Experimental procedures were approved by the University of Minnesota Animal Care and Use Committee.

Experimental animals

We bred Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl mice lacking Bmal1 expression in all steroidogenic tissues, including the adrenal cortex (3), by intercrossing Cyp11A1Cre/+ mice (strain no. 010988, The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) (8) and Bmal1Fl/Fl mice (strain no. 007668, The Jackson Laboratory). Control mice consisted of Cyp11A1+/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl mice [littermates of KO mice; floxed Bmal1–control (CTRL)] and a separate line of Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1+/+ mice (Cre-CTRL). Functional comparisons in vivo and in vitro were made between Cre-CTRL (single wild-type Cyp11A1 allele) and Bmal1-CTRL (two wild-type Cyp11A1 alleles) to assess possible differences in steroidogenic function produced by Cyp11A1 hemizygosity. We also generated Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl::mPER2Luc/+ KO and CTRL mice to monitor rhythms in adrenal bioluminescence ex vivo as a reflection of the mPER2 clock protein rhythm (9, 10) and examined whether Bmal1 deletion in the adrenal cortex affects the adrenal PER2Luc rhythm.

To generate adrenal cortex–specific Bmal1 KO mice, we intercrossed AS-Cre recombinase (ASCre/+, Cyp11B2tm1.1(cre)Brit) mice (11) and Bmal1Fl/Fl mice (The Jackson Laboratory). ASCre/+ is expressed in the differentiated cells of the outer zona glomerulosa, which subsequently undergo transdifferentiation into the inner zona fasciculata cells during postnatal development (11). Using female ASCre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl mice, we found that postnatal transdifferentiation of the adrenal cortex and loss of Bmal1 protein expression occurred by 7 to 8 months of age (5). Because age-matched male ASCre/+::Bmal1 KO mice showed a decrease in the extent of transdifferentiation and in Bmal1 deletion (5), we used only female ASCre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl mice to assess responses to stress. Control mice consisted of a separate line of ASCre/+::Bmal1+/+ mice.

Experimental design

Acute stressors

Mice underwent tail-clip bleeding between ZT2 and ZT3 to obtain nonstress plasma corticosterone values preceding restraint stress. Mice were restrained by placement in 50-mL conical tubes (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH) with air holes drilled in tube bottoms to permit respiration or in tapered plastic film tubes (DecapiCones; Braintree Scientific, Braintree, MA). Mice were euthanized by decapitation after 15 minutes of restraint.

Mice underwent scruff stress between ZT2 and ZT3 by the experimenter’s grasping of the loose skin behind the neck between the thumb and index finger of one hand and holding of the tail with the other hand; after 10 seconds of scruffing, mice were released into a clean mouse cage for 15 minutes and euthanized by decapitation.

Trunk blood was collected and plasma was frozen for measurement of ACTH and corticosterone. Adrenals were collected, cleaned of fat, and weighed; adrenals were stored frozen at −20°C or were immersion fixed in fresh 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C and stored in PBS at 4°C.

In vitro adrenal cell responses to ACTH

Nonstressed mice were euthanized by decapitation between ZT3 and ZT4 and adrenals were collected in Hanks buffered salt solution on ice. Adrenals were cleaned of fat, weighed, and processed for cell dispersion as reported previously using rat adrenals (12). Modifications consisted of using ACTH 1–24, instead of ACTH 1–39, and incubating for 2 hours, instead of 16 hours, to stimulate corticosterone responses. Adrenals collected from individual KO and CTRL mice were dispersed separately (two adrenals from each mouse per sample). Media was stored frozen at −20°C; corticosterone in media was measured by RIA as described below.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry of adrenal slices was performed as described previously (13). Each adrenal was sectioned at 100 μm on a Vibratome 1000 (Vibratome, St. Louis, MO). Free-floating slices were blocked and permeabilized overnight at 4°C in PBS supplemented with 10% donkey serum and 0.5% Triton X-100. The sections were then incubated in primary antibody for 2 to 3 days at 4°C, rinsed with PBS, and incubated overnight in secondary antibody at 4°C. After rinsing in PBS for 1 hour, sections were mounted directly to glass slides and covered with the antifade agent Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). The primary antibody was rabbit anti-BMAL1 (1:1000) (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO) (14). We used donkey anti-rabbit cyanine 5 or donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 594 as secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, 1:500). Confocal z-stacks were acquired using an Olympus FluoView FV1000 confocal microscope with 20× or 40× objectives. Editing of images was limited to adjusting the brightness and contrast levels using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Real-time monitoring of bioluminescence

Animals were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation/decapitation 3.5 to 4.0 hours before lights out (at ZT8 to ZT8.5). Adrenals were rapidly excised and placed in cold Hanks balanced salt solution. After removing the adherent fat, adrenals were hemisected as described previously (9) or tangential cuts (∼300 μm) were made through the adrenal to produce slices containing both cortex and medullary tissue. Tissue was placed on Millicell organotypic inserts in a 35-mm petri dish with 1.5 mL of warmed culture medium (DMEM without phenol red) supplemented with luciferin and penicillin/streptomycin as described previously (9, 15). Dishes were sealed with circular glass coverslips and silicon grease. Cultures were maintained at 36°C, and bioluminescence was measured for 1 minute at 7.5-minute intervals for 7 days using photomultiplier tubes in an Actimetrics LumiCycle (Actimetrics, Evanston, IL). Data from the first day of recording were omitted from analysis due to transient bioluminescent activity (16). The remaining 6 days of data were smoothed and detrended using a 2-hour and 24-hour running average, baseline subtracted, and fit to a dampened sine wave using LumiCycle Analysis software (Actimetrics). For each adrenal sample, the amplitude of each PER2Luc cycle was quantified as the difference between peak and trough values using the exported baseline subtracted time series. Adrenal samples were classified as having no PER2Luc rhythm when no cycle or only a single cycle was detected.

Plasma corticosterone and ACTH analysis

Blood samples were collected in EDTA-treated tubes and centrifuged at 4°C; plasma was stored at −20°C. Corticosterone was determined by 125I RIA using a commercially available kit (17) (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH). The intraassay and interassay coefficients of variation for plasma corticosterone were 8% and 13%, respectively. Plasma ACTH was measured by RIA using a commercially available kit (18) (MP Biomedicals). The intraassay and interassay coefficients of variation for plasma ACTH were 10% and 12%, respectively.

Gene expression analysis

Adrenals were collected from female and male Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl KO and Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1+/+ CTRL mice in the morning (ZT3 to ZT4) at 15 minutes after either restraint or scruff stress. Total RNA was extracted from whole adrenals using a Direct-zol™ RNA miniprep kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

RNA sequencing.

Adrenals from female KO (n = 5, 2.7 ± 0.2 months old) and CTRL (n = 5, 2.4 ± 0.4 months old) mice and male KO (n = 4, 2.3 ± 0.2 months old) and CTRL (n = 6, 2.8 ± 0.4 months old) mice were used for RNA sequencing (RNA-seq). RNA quality was evaluated using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA), and only samples with RNA integrity number value >7.0 were used for RNA-seq. Libraries were prepared using a TrueSeq RNA library prep kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA). RNA-seq was performed on an Illumina NextSeq 500 sequencing platform with single-end 75-bp reads. All samples were processed using an RNA-seq pipeline implemented in the bcbio-nextgen project (19). Raw reads were examined for quality issues using FastQC (20) to ensure that library generation and sequencing were suitable for further analysis. Adapter sequences, other contaminant sequences such as polyA tails, and low-quality sequences with Phred quality scores <5 were trimmed from reads using Atropos (21). Trimmed reads were aligned to University of California Santa Cruz build mm10 of the Mus musculus genome, augmented with transcript information from Ensembl release GRCm38 using Star (22). Alignments were checked for evenness of coverage, rRNA content, genomic context of alignments (e.g., alignments in known transcripts and introns), complexity, and other quality checks using a combination of FastQC (version 0.11.3) and Qualimap (version 30-03-15) (23), MultiQC (24), and custom code with the bcbio-nextgen pipeline tools. Counts of reads aligning to known genes were generated by featureCounts (version 1.4.4) (25). In parallel, transcripts per million measurements per isoform were generated by quasialignment using Salmon (26). Normalization at the gene level was called with DESeq2 (25–27) preferring to use counts per gene estimated from the Salmon quasialignments by tximport (25–28). The bcbioRNASeq package was used to load all of the data from the bcbio-nextgen pipeline and QC (20), and the DEGreport Bioconductor package (29) was used for clustering analysis. DESeq2 (30) was used for differential expression analysis. Significantly differentially expressed genes were determined using a false discovery rate cutoff of 0.05 (P values were multiple test corrected using the Benjamini–Hochberg method). Genes showing increased or decreased expression were uploaded separately to the online DAVID Bioinformatics Resources (version 6.7) (31). Functional annotation analysis was performed using the KEGG pathway database (6).

Quantitative real-time PCR.

Complementary DNA was synthesized using a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix and a QuantStudio 6 Flex real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) on adrenals from female and male Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl KO mice compared with their respective Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1+/+ CTRL mice. The TaqMan Gene Expression probes used for qRT-PCR were Per2 (Mm00478099_m1), Per3 (Mm00478120_m1), Nr1d1 (Mm00520708_m1), cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (Cdkn2a; Mm00494449_m1), dual specificity protein kinase (Ttk; Mm00437205_m1), cyclin G2 (Ccng2; Mm00432394_m1), thyroid hormone receptor α (Thra; Mm00579691_m1), integrin β8 (Itgb8; Mm00623991_m1), Star (Mm00441558_m1), TBC1 domain for family member 4 (Tbc1d4; Mm00557659_m1), and β-actin (Actb; Mm026119580_g1). Expression of the genes of interest were normalized to the expression of the housekeeping gene, Actb, and the comparative 2−ΔΔCT method was used to calculate relative gene expression. Results are presented as n-fold changes in gene expression.

Statistical analysis

Body weight, adrenal weight, adrenal gene transcripts, and hormone data represent mean ± SEM from groups of mice. Statistical differences were determined using one-way ANOVA (using a Tukey correction for post hoc analysis), two-way ANOVA (using a Sidak correction for post hoc analysis), or unpaired Student t test where appropriate using Prism software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). To assess in vitro responses to ACTH, basal corticosterone (no ACTH) was subtracted from post-ACTH responses, and a log ACTH concentration–corticosterone response curve was generated for each sample (two adrenals from each mouse per sample) using a nonlinear least squares four-parameter logistic fit (Prism software). Maximum and EC50 responses were calculated for each sample and analyzed by ANOVA or an unpaired Student t test. Also, the mean response for each dose was calculated, and comparisons between groups were made using ANOVA corrected for repeated measures. Individual means within treatment groups were compared using the Sidak test. Differences were considered significant when P < 0.05.

Results

Deletion of adrenocortical Bmal1 using Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl mice reduces mPER2Luc rhythmicity

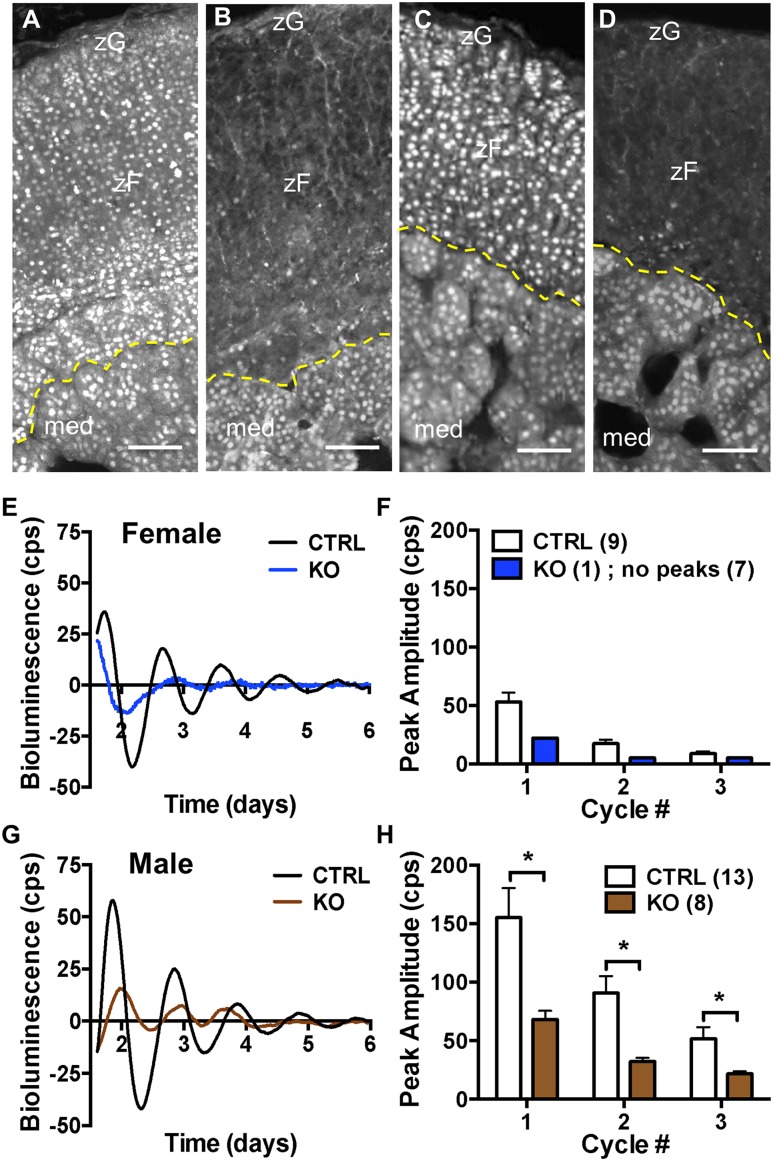

To examine whether deletion of adrenal Bmal1 affects GC responses to acute stress, we initiated experiments using female and male Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl mice. As reported previously in male mice (3), we found that Bmal1 is deleted in the adrenal cortex but not medulla in female (Fig. 1B) and male (Fig. 1D) Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl KO mice compared with Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1+/+ (Cre-CTRL) mice (Fig. 1A and 1C). To determine whether loss of adrenal cortical Bmal1 results in loss of a functioning adrenal clock, we crossed KO, Cre-CTRL, and Cyp11A1+/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl (Bmal1-CTRL) mice with mPER2::Luciferase (mPER2Luc) mice in which ex vivo rhythms in adrenal bioluminescence reflect the endogenous mPER2 clock protein rhythm (10, 32). There were no differences in peak amplitude in adrenal mPER2Luc rhythms between female Cre-CTRL and Bmal1-CTRL mice or between male Cre-CTRL and Bmal1-CTRL mice, so data from Cre-CTRL and Bmal1-CTRL mice were combined for each sex. Deletion of adrenal Bmal1 in female KO mice results in loss of adrenal mPER2Luc rhythms compared with CTRL mice; most KO adrenals (seven of eight) showed no rhythm (Fig. 1E and 1F). In male KO mice, mPER2Luc rhythms persisted but peak amplitudes were decreased compared with CTRL mice (Fig. 1G and 1H). As reported previously (4), female adrenals show reduced amplitude in the mPER2Luc rhythm compared with male adrenals. When sex differences in peak amplitude are taken into account, Bmal1 deletion results in comparable decreases in the amplitude of the mPER2Luc rhythm in female and male mice (Fig. 1F and 1H).

Figure 1.

Adrenal BMAL1 and mPER2Luc rhythms in female and male Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1FL/FL KO mice. In Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1+/+ CTRL mice, nuclear BMAL1 labeling is observed in the adrenal cortex (zona glomerulosa and zona fasciculata) and medulla of (A) female and (C) male mice. In (B) female and (D) male KO mice, nuclear BMAL1 labeling is absent in the adrenal cortex but not the medulla. Mice were 2 to 3 mo of age. (A–D) BMAL1 immunofluorescence labeling; med., medulla; zF, zona fasciculata; zG, zona glomerulosa. Border between cortex and medulla denoted by dashed yellow lines. Scale bars, 50 µm. Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl mice were intercrossed with mPER2Luc mice and adrenal mPER2Luc was monitored ex vivo to assess the mPER2 clock protein rhythm (9). (E) Adrenals from a CTRL female Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1+/+::PER2Luc (Cre-CTRL) mouse show mPER2Luc rhythms that persist for ∼3 to 4 d ex vivo, whereas adrenals from a female Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl::PER2Luc KO mouse show reduced mPER2Luc rhythmicity. (F) Peak amplitude dampened ex vivo over daily cycles in CTRL mice, but most adrenals from female KO mice (seven of eight) showed no peaks. (G) Adrenals from a CTRL male (Cre-CTRL) mouse show a mPER2Luc rhythm for 4 to 5 d, whereas adrenals from a male KO mouse show a lower amplitude rhythm. Peak amplitudes were lower in (F) female vs (H) male CTRL adrenals. (H) Amplitudes in daily cycles of mPER2Luc of male KO adrenals were decreased compared with male CTRL adrenals (mean ± SEM; n = 8 to 13 mice; *P < 0.05). Adrenal Bmal1 deletion results in parallel reduction in the amplitude of the mPER2Luc rhythm in female and male mice.

Deletion of adrenocortical Bmal1 increases adrenal weight in male and female Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl mice

For both male and female mice, no differences were observed in body weight between KO, Cre-CTRL, or Bmal1-CTRL mice. Increases in adrenal weight occurred in male KO mice compared with Bmal1-CTRL mice, but not to Cre-CTRL mice, whereas adrenal weight was increased in female KO mice compared with Bmal1-CTRL and Cre-CTRL mice. Adrenal weight normalized to body weight showed similar differences between genotypes for male and female mice (Table 1). As shown previously in adult mice (33), both absolute and normalized adrenal weight were greater in female mice compared with male mice for each genotype.

Table 1.

Body and Adrenal Weight as a Function of Genotype

| Genotype | Sex | n | Age (mo) | BW (g) | AW (mg) | AW/BW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyp11A1 +/+ ::Bmal1 Fl/Fl (Bmal1-CTRL) | M | 18 | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 28.1 ± 1.2 | 3.40 ± 0.12 | 12.2 ± 0.5 |

| Cyp11A1 Cre/+ ::Bmal1 +/+ (Cre-CTRL) | M | 5 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 26.9 ± 0.7 | 3.97 ± 0.34 | 14.8 ± 1.4 |

| Cyp11A1 Cre/+ ::Bmal1 Fl/Fl (KO) | M | 16 | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 28.1 ± 1.5 | 4.38 ± 0.21a | 15.9 ± 0.8a |

| Cyp11A1 +/+ ::Bmal1 Fl/Fl (Bmal1-CTRL) | F | 15 | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 19.8 ± 0.6 | 6.50 ± 0.23 | 33.4 ± 1.5 |

| Cyp11A1 Cre/+ ::Bmal1 +/+ (Cre-CTRL) | F | 7 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 20.6 ± 0.7 | 6.23 ± 0.15 | 30.4 ± 1.3 |

| Cyp11A1 Cre/+ ::Bmal1 Fl/Fl (KO) | F | 17 | 3.1 ± 0.2 | 20.1 ± 0.4 | 8.06 ± 0.36a,b | 39.9 ± 1.3a,b |

| Cyp11B2 Cre/+ ::Bmal1 +/+ (Cre-CTRL) | F | 11 | 7.9 ± 0.3 | 31.0 ± 2.7 | 6.87 ± 0.16 | 23.7 ± 1.9 |

| Cyp11B2 Cre/+ ::Bmal1 Fl/Fl (KO) | F | 9 | 7.4 ± 0.3 | 25.7 ± 0.9 | 8.77 ± 0.33b | 34.4 ± 1.5b |

Data are presented as means ± SEM. Cyp11B2 or AS. AW (mg)/100 g of BW.

Abbreviations: AW, adrenal weight; BW, body weight; F, female; M, male.

P < 0.05 vs Bmal1-CTRL.

P < 0.05 vs Cre-CTRL.

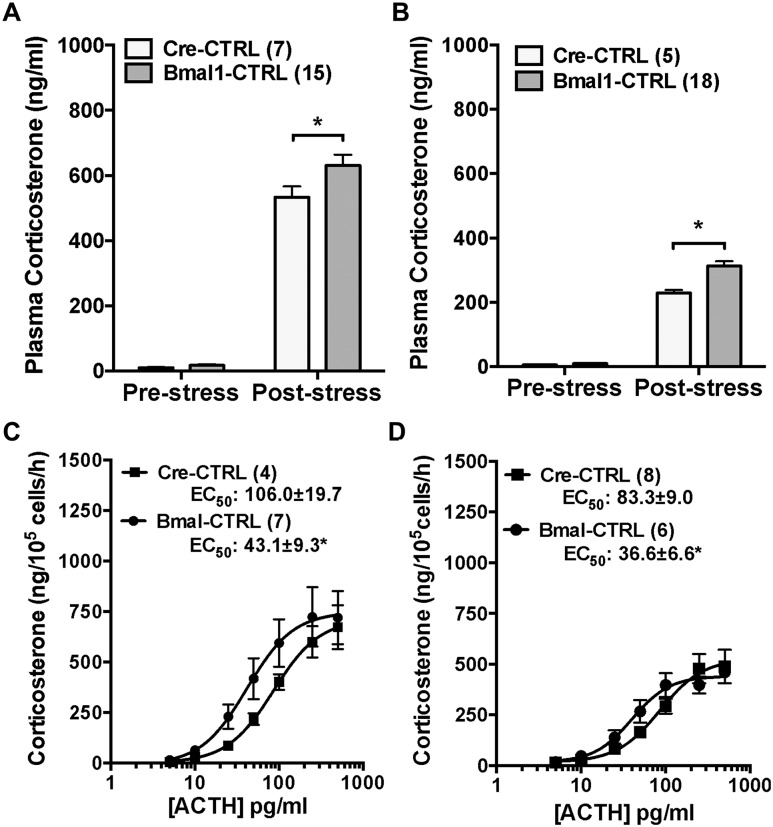

Comparison of Cyp11A1 CTRL groups to assess potential Cyp11A1 haploinsufficiency

Because the Cyp11A1 gene encodes the SCC enzyme that is essential for steroidogenesis (34), using Cyp11A1 as a Cre driver to delete Bmal1 could result in SCC haploinsufficiency, affecting any steroidogenic effect produced by Bmal1 deletion. The functional effect of Cyp11A1 hemizygosity was examined by comparing Cre-CTRL mice (one Cyp11A1 wild-type allele) to Bmal1-CTRL mice (two Cyp11A1 wild-type alleles). There were no differences in prestress plasma corticosterone in male or female CTRL groups, but the plasma corticosterone response to acute restraint stress was reduced in female and male Cre-CTRL mice (Fig. 2A and 2B); poststress plasma ACTH was not different (data not shown). In vitro adrenal cell corticosterone responses to ACTH showed the same maximum in male (Bmal1-CTRL, 538.5 ± 88.1 vs Cre-CTRL, 493.3 ± 28.2 ng/105 cells/h) and female (Bmal1-CTRL, 760.0 ± 142.7 vs Cre-CTRL, 796.2 ± 161.4 ng/105 cells/h) mice but a higher EC50 response in Cre-CTRL male (Bmal1-CTRL, 36.6 ± 6.6 vs Cre-CTRL, 83.3 ± 9.0 pg/mL, P < 0.05) and female (Bmal1-CTRL, 43.1 ± 9.3 vs Cre-CTRL, 106.0 ± 19.0 pg/mL, P < 0.05) mice (Fig. 2C and 2D). Taken together, the in vivo and in vitro results indicate that Cyp11A1 haploinsufficiency occurs in Cre-CTRL mice, supporting their use as optimal CTRLs for functional responses in Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl KO mice that carry a single Cyp11A1 allele.

Figure 2.

Comparison of in vivo plasma corticosterone responses to acute stress and in vitro adrenal cell corticosterone responses to ACTH in male and female CypA1Cre/+::Bmal1+/+ (Cre-CTRL) and CypA1+/+::Bmal1FL/FL (Bmal-CTRL) mice. Prestress plasma corticosterone in the morning did not differ between (A) female or (B) male Cre-CTRL and Bmal1-CTRL mice, but responses to 15-min restraint stress were reduced in (A) female and (B) male Cre-CTRL mice. Corticosterone secretion from adrenal cells in vitro showed the same maximum but higher EC50 responses to ACTH in (C) female and male (D) Cre-CTRL mice. Mean ± SEM; n = 4 to 8 mice; *P < 0.05.

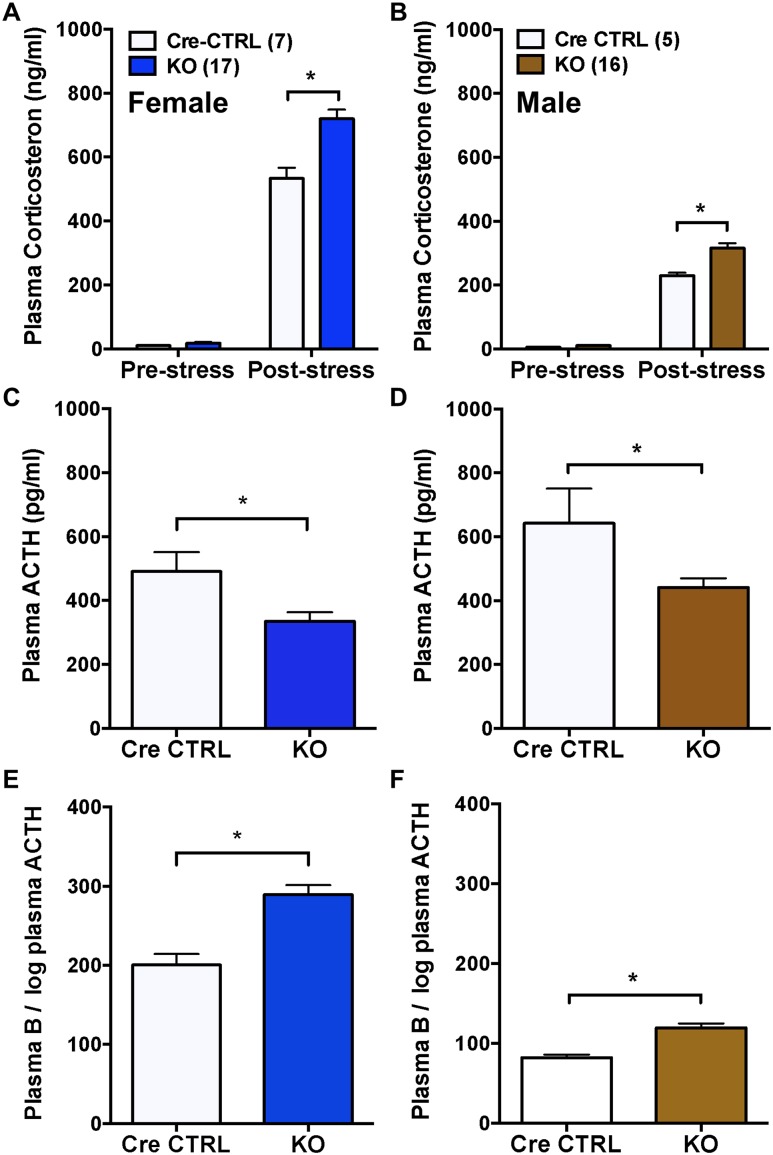

Deletion of adrenocortical Bmal1 results in augmented GC responses to acute restraint stress in male and female Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl mice

Plasma corticosterone from tail bleeds collected prior to stress was not different between female or male Cre-CTRL and KO mice (Fig. 3A and 3B), indicating that adrenal Bmal1 deletion does not alter basal plasma corticosterone. In contrast, plasma corticosterone responses to tail-clip sampling and 15-minute restraint stress were augmented in male and female KO mice compared with Cre-CTRL mice (Fig. 3A and 3B). Plasma ACTH following restraint was decreased in both male and female KO mice (Fig. 3C and 3D), indicating that higher corticosterone responses were associated with reduced plasma ACTH. Calculation of the ratio of plasma corticosterone to the log of plasma ACTH, used as an indirect indicator of adrenal responsiveness to ACTH (35), showed increased adrenal responsiveness in both male and female KO mice compared with Cre CTRLs (Fig. 3E and 3F).

Figure 3.

Augmented corticosterone responses to acute stress in male and female adrenal CypA1Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl KO mice. Prestress plasma corticosterone in (A) female and (B) male mice was not different between CypA1Cre/+::Bmal1+/+ (Cre-CTRL) and CypA1Cre/+::Bmal1FL/FL KO mice. In response to tail-clip sampling and 15-min restraint, plasma corticosterone responses were augmented in (A) female and (B) male KO mice compared with Cre-CTRL mice. Plasma ACTH was increased in (C) female and (D) male Cre-CTRL mice compared with KO mice. The ratio of plasma corticosterone (compound B) to the log plasma ACTH, an indirect assessment of adrenal responsiveness to ACTH, was increased in (E) female and (F) male KO mice compared with Cre-CTRL mice. Mean ± SEM; n = 5 to 17 mice; *P < 0.05.

Deletion of adrenocortical Bmal1 results in augmented GC responses to acute submaximal scruff stress only in female Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl mice

To examine whether the effect of adrenal Bmal1 deletion was dependent on the intensity of stress, mice were exposed to a brief (10-second duration) scruff stress to elicit a submaximal corticosterone response. Based on comparison with restraint stress (Fig. 3), plasma corticosterone responses to scruff stress were lower in female Cre-CTRL [scruff, 276.2 ± 20.9 ng/mL (n = 5) vs restraint: 533.1 ± 33.5 ng/mL (n = 7); P < 0.05] and male Cre-CTRL [scruff, 183.6 ± 22.2 ng/mL (n = 9) vs restraint, 229.4 ± 9.0 ng/mL (n = 5); P = 0.054] mice. Plasma corticosterone at 15 minutes after scruff stress was increased in female KO mice compared with Cre-CTRL mice (Fig. 4A); in contrast, no differences in plasma corticosterone were observed between male KO and Cre-CTRL mice (Fig. 4B). Plasma ACTH following scruff stress was not different between female (Fig. 4C) or male (Fig. 4D) KO mice and Cre-CRTL mice. The ratio of plasma corticosterone to the log of plasma ACTH was increased in female KO mice (Fig. 4E) but not male KO mice (Fig. 4F), compared with Cre-CTRL mice. These data suggest that corticosterone responses to a submaximal stress are increased by Bmal1 deletion in a sex-dependent fashion that could be due to changes in adrenal responsiveness to ACTH.

Figure 4.

Augmented corticosterone responses to submaximal scruff stress in female but not male adrenal CypA1Cre/+::BmalFl/Fl KO mice. Plasma corticosterone at 15 min after brief (10-s) scruff stress was increased in (A) female KO mice compared with CTRL mice, but not in (B) male KO mice compared with Cre-CTRL mice. (C and D) Plasma ACTH following scruff stress was not different between (C) female or (D) male KO mice compared with CTRL mice. The ratio of plasma corticosterone (compound B) to the log plasma ACTH was increased in (E) female but not (F) male KO mice compared with Cre-CTRL mice. Mean ± SEM; n = 5 to 9 mice; *P < 0.05.

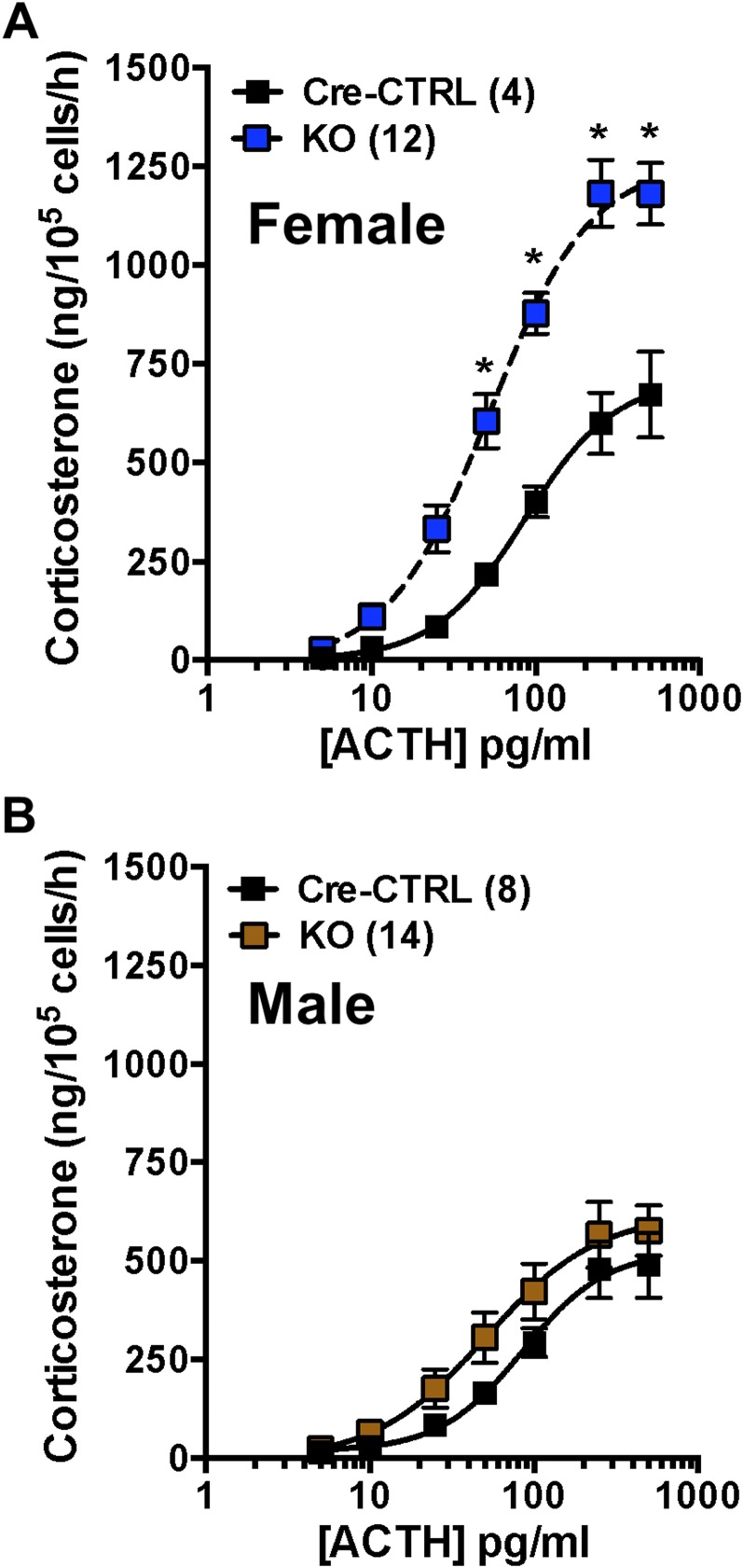

Deletion of adrenocortical Bmal1 results in augmented in vitro GC responses to ACTH only in female Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl mice

To examine whether augmented corticosterone responses to acute stress are due in part to changes in adrenal responsiveness to ACTH, collagenase-dispersed adrenocortical cells were incubated with increasing concentrations of ACTH. Results showed that corticosterone responses at the high range of the ACTH concentration–response curve were increased in adrenal cells from female KO mice compared with Cre-CTRL mice (Fig. 5A). The maximum response of female KO adrenal cells was increased (Cre-CTRL, 796.2 ± 161.4 vs KO, 1391.0 ± 144.9; P < 0.05); the EC50 response (Cre-CTRL, 106 ± 19.7 vs KO, 98.2 ± 24.7) was not different, suggesting that sensitivity to ACTH was not affected. Although there was a trend for higher corticosterone responses of adrenal cells to ACTH from male KO mice, responses were not different from Cre-CTRL mice (Fig. 5B); neither the maximum response (Cre-CTRL, 538 ± 88.1 vs KO: 688.0 ± 81.3) nor the EC50 response [Cre-CTRL, 83.3 ± 9.0 (8) vs KO: 84.2 ± 16.3 (14)] was different.

Figure 5.

Corticosterone responses to ACTH in acutely dispersed adrenal cells from female and male CypA1Cre/+::BmalFl/Fl KO mice. (A) Corticosterone responses to ACTH were increased in adrenal cells from female KO mice compared with Cre-CTRL mice. (B) In contrast, corticosterone responses to ACTH of adrenal cells from male KO mice were not different from Cre-CTRL mice. Mean ± SEM; n = 4 to 14 mice; *P < 0.05.

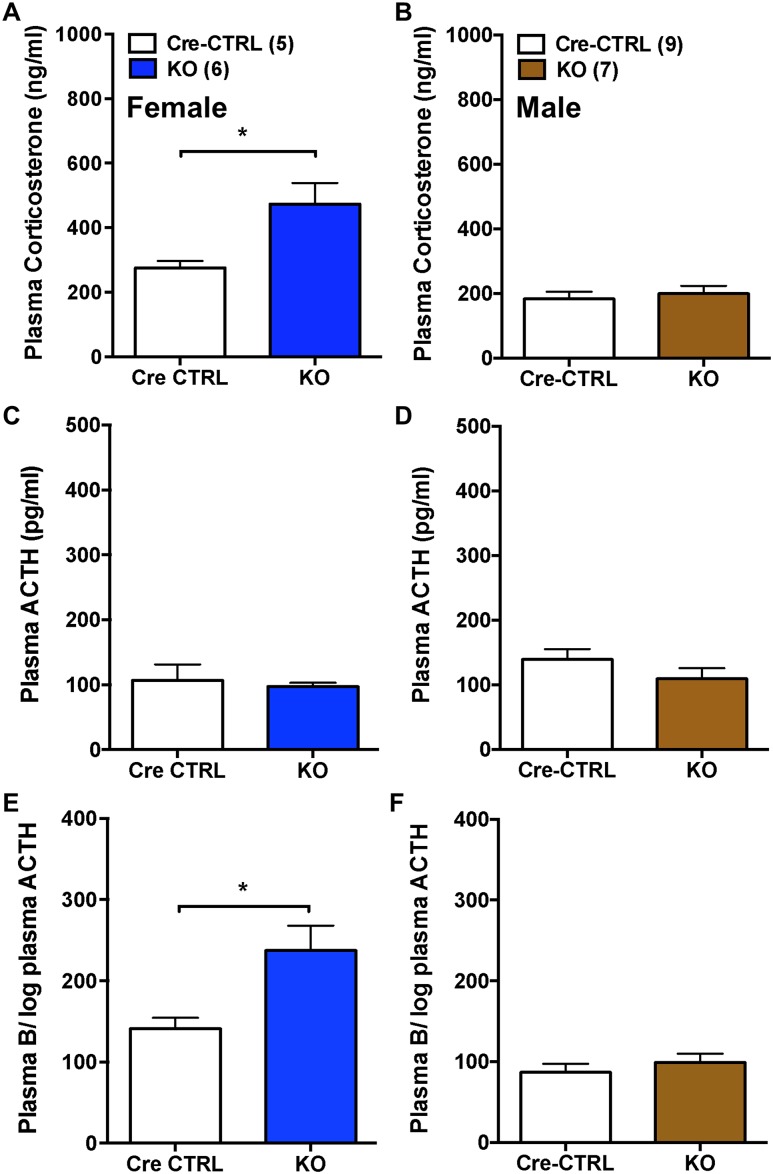

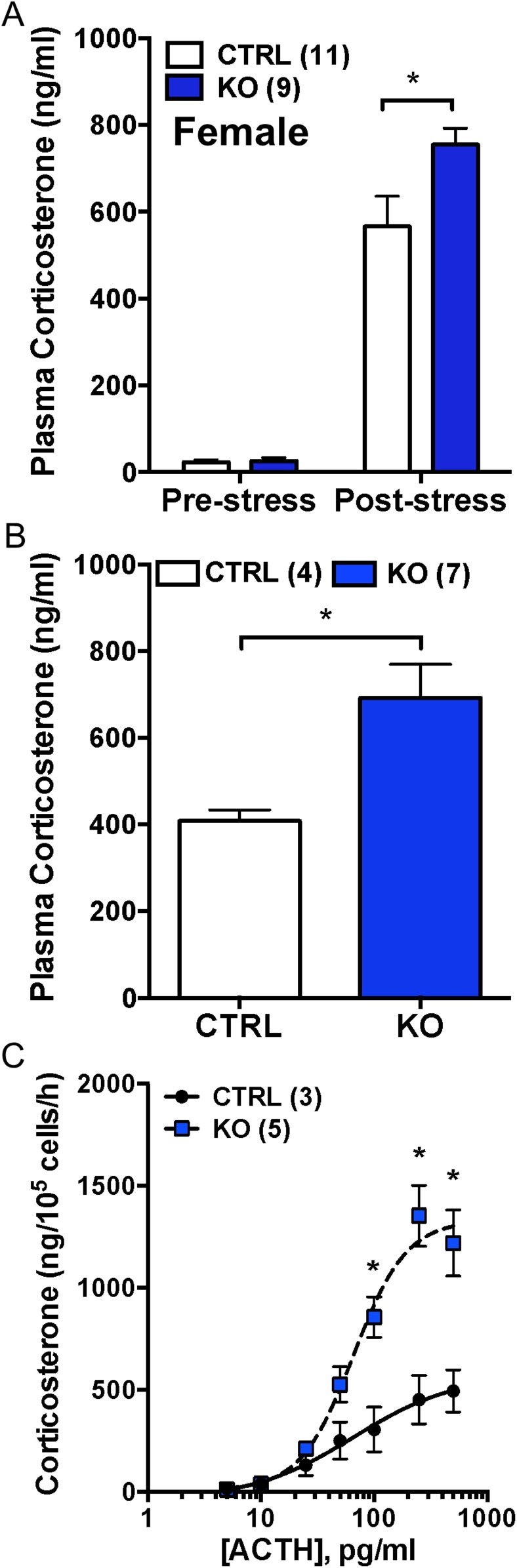

Deletion of adrenocortical Bmal1 using female Cyp11B2 (AS)Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl mice confirms hyperadrenocortical responses in vivo and in vitro

To confirm that the hyperadrenocortical response observed in Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl KO mice was due to Bmal1 deletion in the adrenal cortex, responses to acute restraint stress were measured in female ASCre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl KO and ASCre/+::Bmal1+/+ CTRL mice. Similar to female Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl KO mice, adrenal weight was increased in female ASCre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl KO mice compared with CTRL mice (Table 1). Although there were no differences in prestress plasma corticosterone, corticosterone responses to restraint were augmented in female ASCre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl KO mice (Fig. 6A). The plasma ACTH response to restraint stress was not different between ASCre/+::Bmal1+/+ CTRL (592 ± 95 pg/mL, n = 11) and ASCre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl KO (520 ± 72 pg/mL, n = 9) mice. In response to scruff stress, plasma corticosterone also was increased in KO compared with CTRL mice (Fig. 6B). There were no differences in plasma ACTH between CTRL (167 ± 37 pg/mL, n = 4) and KO (182 ± 53 pg/mL, n = 7) mice. Adrenal cell responses to ACTH also were measured in vitro. Similar to results observed in female Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl mice, corticosterone responses at the high range of the ACTH concentration–response curve were increased in adrenal cells from female ASCre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl KO mice compared with CTRL mice (Fig. 6C). The maximum response of female KO adrenal cells was increased (CTRL, 566.2 ± 122.4; KO, 1335 ± 164.9; P < 0.05); the EC50 response (CTRL, 66.6 ± 7.3 vs KO, 108.5 ± 56.5) was not different. These data confirm that adrenal cortex–specific deletion of Bmal1 results in a hyperadrenocortical response to acute stress, as well as increased adrenal cell responsiveness to ACTH.

Figure 6.

Augmented corticosterone responses in female adrenal ASCre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl KO mice to acute stress in vivo and to ACTH in vitro. (A) Prestress plasma corticosterone was not different between female CTRL and KO mice. In response to tail-clip sampling and 15-min restraint, plasma corticosterone was augmented in female ASCre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl KO mice compared with ASCre/+::Bmal1+/+ CTRL mice. (B) Plasma corticosterone at 15 min after brief (10-s) scruff stress also was increased in female KO mice compared with CTRL mice. *P < 0.05. (C) Acutely dispersed adrenal cells from female ASCre/+::Bmal1FL/FL KO mice secreted increased corticosterone to ACTH in vitro compared with female CTRL mice. Mean ± SEM; n = 3 to 5 mice; *P < 0.05.

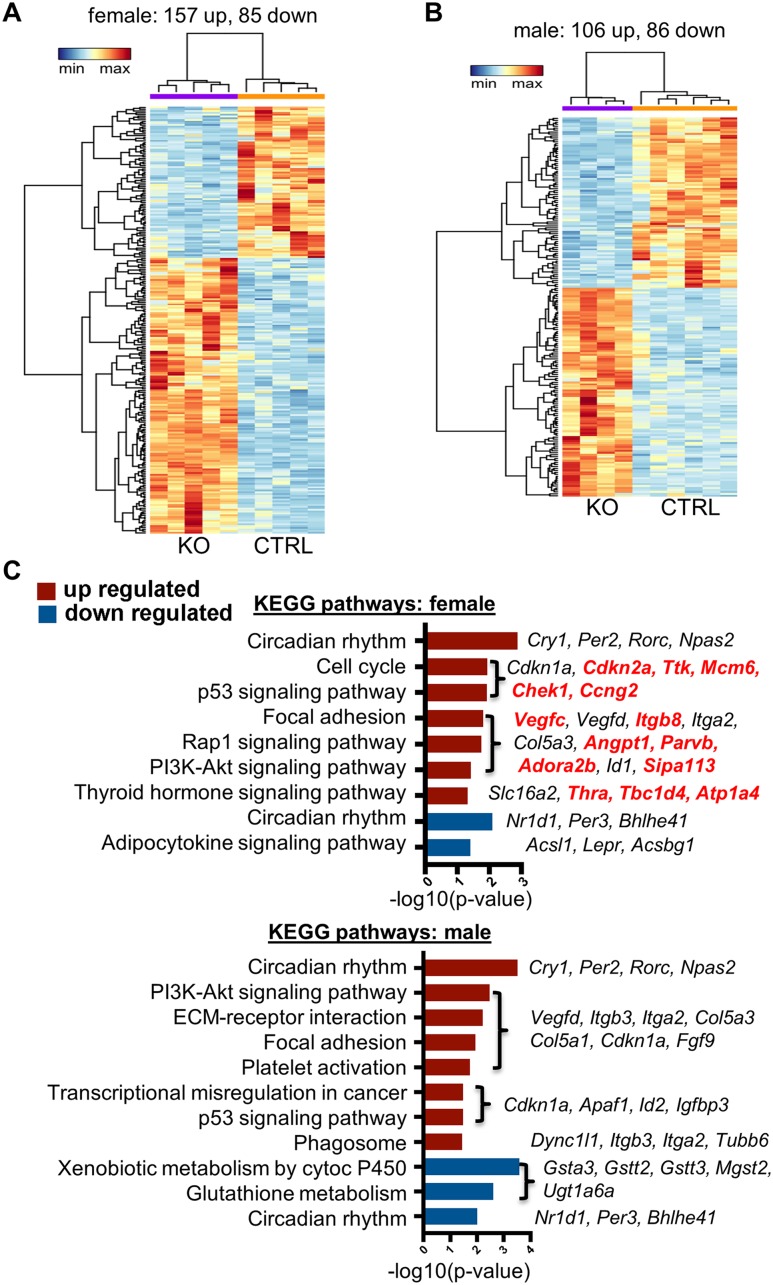

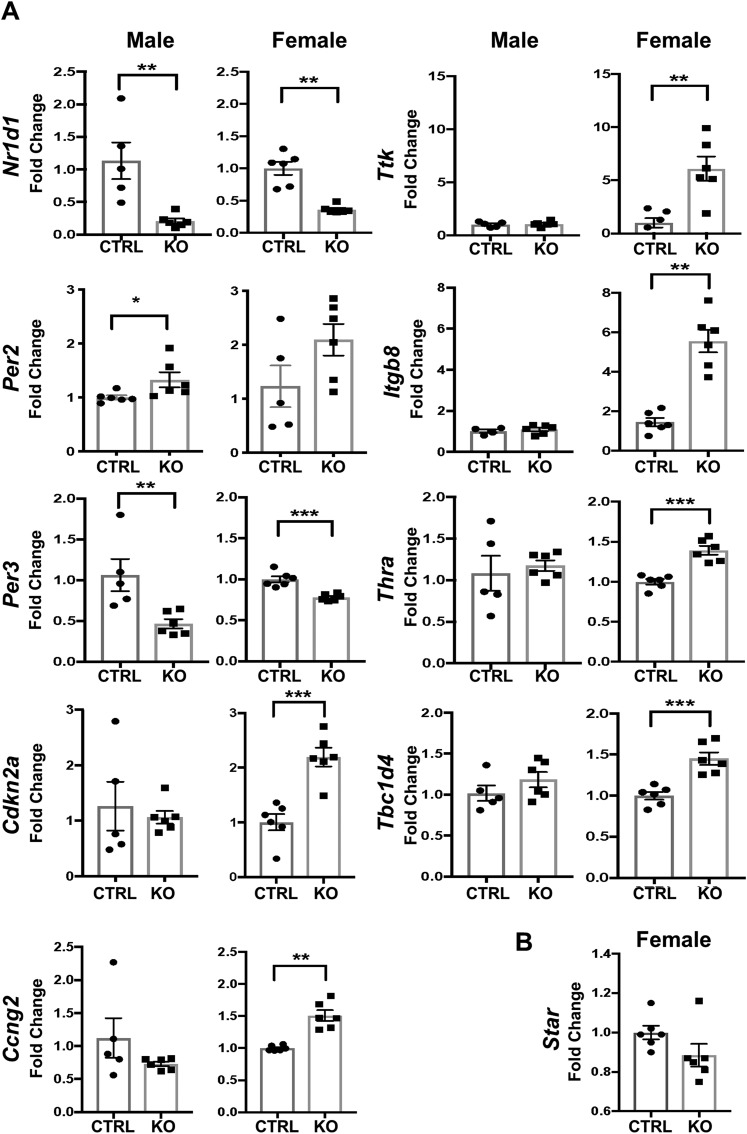

Sex differences in differentially expressed adrenal genes in Bmal1 KO mice

To identify potential Bmal1-dependent mechanisms involved in (i) the hyperadrenocortical response to acute stress and to ACTH and (ii) the sex-specific response, we assessed mRNA expression profiles by RNA-seq analysis. Initial comparisons were made between female Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl KO and Cre-CTRL mice and between male KO and Cre-CTRL mice. Comparisons in female mice found 242 differentially expressed transcripts in KO adrenals with 157 increased and 85 decreased (Fig. 7A), whereas comparisons in male mice found 192 differentially expressed transcripts in KO adrenals with 106 increased and 86 decreased (Fig. 7B). Comparisons of female and male KO adrenals revealed 82 dysregulated transcripts that were shared (53 increased, 29 decreased). These genes included circadian clock genes Cry1 (36), Per2 (37), Rorc (38), and Npas2 (39) that were increased and Nr1d1 (40), Per3 (41), and Bhlhe41 (42) that were decreased (Fig. 7C). Complete data sets for these comparisons are available via the Gene Expression Omnibus repository of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (43). To identify potential genes responsible for sexually dimorphic steroidogenic responses, we searched for enrichment of KEGG pathways in each data set and identified genes that were upregulated uniquely in female KO adrenals. This comparison revealed 14 genes that were specifically increased in adrenals from female KO mice. KEGG analysis showed gene enrichment in multiple pathways, including cell cycle control (Cdkn2a, Ttk, Chek1, Mcm6, Ccng2); focal adhesion, Rap1, and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase–Akt signaling (Vegfc, Itgb8, Angpt1, Parvb, Adora2b, Sipa1l3); and thyroid hormone signaling (Thra, Tbc1d4, Atp1a4) (Fig. 7C). To validate the results of the RNA-seq analysis, we used independent samples and analyzed a subset of the differentially expressed genes by qRT-PCR. Results confirmed that circadian genes Nr1d1 and Per3 were decreased in female and male KO mice, whereas Per2 and Cry1 (data not shown) were increased in female but not in male KO mice. Cell cycle genes Cdkn2A, Ttk, and Ccng2, thyroid hormone receptor signaling genes Thra and Tbc1d4, and focal adhesion gene Itgb8 were increased selectively in female KO mice (Fig. 8A). Thus, most genes identified by RNA-seq analysis were validated by qRT-PCR. Notably, we measured no increase in expression of Star mRNA in adrenals from female KO mice (Fig. 8B), suggesting that StAR is not involved in the increased adrenocortical response in female KO mice. Collectively, these data suggest that adrenocortical Bmal1 deletion results in sex-dependent changes in gene expression that may account for the augmented GC response in female KO mice.

Figure 7.

RNA-seq of CypA1Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl KO and CypA1Cre/+::Bmal1+/+ Cre-CTRL adrenals reveals sex-biased gene expression. (A) RNA-seq analysis revealed 242 genes in female adrenals (157 upregulated and 85 downregulated) and (B) 192 genes in male adrenals (106 upregulated and 86 downregulated) significantly changed, with a false discovery rate <0.05 and fold change >1.5 (upregulated) or <0.5 (downregulated) (n = 4 to 6). Heat maps of reads per kilobase million values from (A) female and (B) male CypA1Cre/+::Bmal1fl/fl KO and Cre-CTRL adrenals. Dendrograms represent hierarchical clustering of genes (left) and samples (top). (C) KEGG pathways enriched in upregulated (red) or downregulated (blue) genes in female and male data sets. Genes enriched in specific KEGG pathways are listed, with red font indicating uniquely upregulated genes in female KO adrenals.

Figure 8.

Validation of the RNA-seq analysis. (A) Selected genes that emerged from the RNA-seq data set as differentially expressed either in female or male CypA1Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl KO adrenals were validated by quantitative PCR using independent samples. (B) Star transcripts were not affected by loss of Bmal in female adrenals. Mean ± SEM; n = 5 to 6 mice; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

Experiments were done to determine whether adrenal Bmal1 was required to maintain the corticosteroid response to acute stress. Using two different lines of adrenal Bmal1 KO mice, that is, Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl (3) and ASCre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl (5) mice, we found that the plasma corticosterone response to acute restraint stress was augmented in male and female mice by adrenal Bmal1 deletion. However, following acute scruff stress that resulted in a submaximal corticosterone response, only female Bmal1 KO mice showed an augmented plasma corticosterone response. In vitro experiments showed that corticosterone responses to ACTH were elevated in primary cultures of adrenocortical cells from female, but not male, adrenal Bmal1-null mice, suggesting that increased plasma corticosterone response to stress may result in part from increased adrenal responsiveness to ACTH. These observations underscore an important role for adrenal Bmal1 as an attenuator of steroidogenesis that is most prominent in female mice.

The strategy for using Cyp11A1-Cre mice to delete Bmal1 in the adrenal cortex via a Cre-LoxP approach was based on previous work showing successful loss of adrenal molecular clock gene rhythms in male Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl mice (3). Based on monitoring adrenal mPER2Luc rhythms ex vivo, our results confirm that adrenal Bmal1 deletion results in attenuation of adrenal clock gene rhythms in male and female Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl KO mice. The Cyp11A1 gene encodes the SCC enzyme that is essential for corticosteroid formation (34). Using Cyp11A1 as a Cre driver was successful in deleting adrenal Bmal1; however, Cyp11A1Cre/+ mice could have reduced steroidogenic potential due to Cyp11A1 haploinsufficiency (8) that could offset or enhance the effect of Bmal1 deletion on corticosteroid responses. For example, clinical case studies have reported that heterozygous mutations in Cyp11A1 can result in adrenal insufficiency (44, 45). Therefore, we examined the potential functional effect of Cyp11A1 hemizygosity on in vivo and in vitro corticosteroid responses by comparing two lines of CTRL mice, Cre-CTRL and Bmal1-CTRL mice, that are Cyp11A1 hemizygous and wild type, respectively. Both male and female Cre-CTRL mice produced lower stress-induced plasma corticosterone than did Bmal1-CTRL mice. In vitro corticosterone responses of adrenal cells to ACTH from male and female Bmal1-CTRL and Cre-CTRL mice showed the same response maximum; however, adrenal cells from male and female Cre-CTRL mice showed higher EC50 responses to ACTH compared with Bmal1-CTRL mice, suggesting decreased sensitivity to ACTH in adrenal cells from Cre-CTRL mice. Although comparisons between CTRL groups indicated Cyp11A1 haploinsufficiency in Cre-CTRL mice, these effects on corticosterone production did not preclude our use of Cre-CTRL mice as the optimal CTRL group for determining functional responses produced by adrenal Bmal1 deletion in Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl KO mice.

Both male and female Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl KO mice demonstrated augmented plasma corticosterone responses to acute restraint stress compared with Cre-CTRL mice. By using Cyp11A1 as a driver of Cre-recombinase, Bmal1 is deleted from all steroidogenic tissues, including the gonads (3). Therefore, we completed parallel experiments using female Cyp11B2 (AS)Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl KO mice in which Bmal1 deletion is restricted to the adrenal cortex (5). Female ASCre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl KO mice also showed augmented plasma corticosterone responses to acute restraint stress, confirming the hyperadrenocorticism observed in Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl KO mice. Because plasma corticosterone responses to restraint stress may have approached a maximum in female and male mice that limited observation of Bmal1 deletion-induced augmentation due to a ceiling effect, we exposed mice to a less intense scruff stress that produced submaximal plasma corticosterone responses. Results showed that adrenal Bmal1 deletion produces a hyperadrenocortical response to scruff stress in female mice, but not in male mice. These data indicate that a stress phenotype induced by Bmal1 deletion is affected by stress intensity and is most prominent in female mice. Our finding of increased stress-induced corticosterone in adrenal Bmal1 KO mice differs from previous work that reported no stress phenotype in transgenic lines that target adrenal Bmal1 (1, 3). Because corticosteroid responses to stress vary with sex (46, 47), time of day (46, 48–50), and the severity or type of stressor (48, 50), differences in these variables [reviewed in (51)] could account for the absence of a phenotype in previous work. We tested both male and female mice at the nadir (ZT3) of the circadian rhythm using a brief restraint stress or submaximal scruff stress. By applying a stressor at a circadian time when adrenal sensitivity to ACTH in male and female rodents is low (52, 53), higher stress-induced corticosterone was observed in adrenal Bmal1 KO mice that was dependent on stress intensity. In contrast to our results, exposure of male Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl mice to forced swim stress at the peak of the circadian rhythm showed no phenotype (3). Differences in sex, stress severity, or application of stress when adrenal sensitivity to ACTH is highest (52, 53) may have prevented observation of a stress phenotype. In MC2R-AS-BMAL transgenic mice, in which the adrenal clock is knocked down by expressing part of the BMAL1 coding region in an antisense orientation under adrenal cortex-specific CTRL using the ACTH receptor (MC2R) promoter (1), no differences were observed in corticosterone responses to immobilization stress in male mice tested at the nadir or peak of the circadian rhythm; however, immobilization is a high-intensity stressor that may maximally stimulate corticosterone, preventing observation of a stress phenotype.

The mechanism for hyperadrenocortical responses in adrenal Bmal1 KO mice is unknown. In male and female Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl KO mice, plasma ACTH after restraint stress was decreased in KO mice compared with Cre CTRLs, suggesting that higher corticosterone responses were associated with reduced plasma ACTH. Based on this relationship, we determined the ratio of plasma corticosterone to the log of plasma ACTH as an indirect indicator of adrenal responsiveness to ACTH (35); the ratio was increased in male and female Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl KO mice following restraint stress and in female Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl KO mice following scruff stress, suggesting that augmented plasma corticosterone responses to stress may reflect changes in adrenal responsiveness to ACTH. Concomitant with changes in adrenal responsiveness, lower plasma ACTH at 15 minutes after stress could result from inhibition by rapid increases in plasma corticosterone acting via steroid-negative fast feedback (48). To address adrenal responsiveness directly, we completed a series of experiments using acutely dispersed adrenal cells to test adrenal sensitivity to ACTH. Adrenals were collected in the morning at the nadir of the circadian rhythm (ZT3) when adrenal sensitivity to ACTH is low in rodents in vivo (52, 53) and in vitro (2, 54). Results showed that adrenal cells from female Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl KO mice produced a higher maximum corticosterone response to ACTH compared with Cre-CTRL mice; there was no difference in the EC50 response, suggesting that Bmal1 deletion increases the ability of ACTH to produce maximum steroidogenesis without affecting ACTH sensitivity or potency. In contrast, corticosterone responses of adrenal cells from male Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl KO mice showed no consistent alteration in the maximum response or the EC50 response to ACTH, indicating that the adrenal phenotype was limited to female mice. A similar augmentation of the maximum corticosterone response to ACTH was observed in adrenal cells from female ASCre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl KO mice, supporting the conclusion that adrenal Bmal1 deletion results in increased adrenal responsiveness to ACTH. These results differ from those reported previously in which in vitro corticosterone responses of adrenal slices to ACTH were not affected in male Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl KO mice (3). However, adrenals were collected in the evening at the peak of the rhythm in adrenal sensitivity to ACTH (2, 52, 54), raising the possibility that diurnal increases in adrenal sensitivity in CTRL mice offset heightened sensitivity produced by adrenal Bmal1 deletion. Additional experiments comparing morning and evening sensitivity to ACTH are necessary to address whether loss of adrenal Bmal1 prevents the adrenal sensitivity rhythm by increasing adrenal sensitivity in the morning relative to CTRLs; this finding would support previous work suggesting that the adrenal clock gates rhythms in adrenal sensitivity to ACTH (2). Any work on this question requires consideration of possible sex differences, because our in vitro data indicate that adrenal Bmal1 deletion produces a stronger adrenal phenotype in female mice. There is strong evidence that gonadal steroids can effect adrenal responsiveness to ACTH (55), so Bmal1 deletion in the gonads of Cyp11A1Cre/+::Bmal1Fl/Fl KO mice could indirectly affect adrenal function by changing gonadal steroid secretion. However, we also found enhanced corticosterone responses in female Cyp11B2 KO mice in which gonadal function likely would not be directly affected by Bmal1 deletion. Nonetheless, it would be of interest to determine whether differences in gonadal steroids could contribute to the sexual dimorphism observed in either mouse model of Bmal1 deletion.

To identify candidate genes that could mediate the sexually dimorphic GC response in adrenal Bmal1 KO mice, we used RNA-seq to compare adrenal gene expression between KO and CTRL mice as a function of sex. We found 242 and 192 differentially expressed genes in female and male KO mice, respectively; of these, 82 dysregulated transcripts (53 upregulated, 29 downregulated) were common to female and male KO adrenals. These transcripts included circadian clock genes Cry1 (36), Per2 (37), Rorc (38), and Npas2 (39) that were upregulated and Nr1d1 (40), Per3 (41), and Bhlhe41 (42) that were downregulated, confirming sex-independent dysregulation of the circadian clock by Bmal1 deletion. Using KEGG enrichment analysis, we identified 14 genes that were uniquely upregulated in female KO adrenals. These transcripts are associated with multiple cellular pathways, including cell cycle control, cell adhesion, Rap1 and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase–Akt signaling, and thyroid hormone signaling. We used quantitative PCR to validate the RNA-seq results, confirming upregulation of cell cycle control genes Cdkn2A, Ttk, and Ccng2, thyroid hormone receptor signaling genes Thra and Tbc1d4, and the focal adhesion gene Itgb8. Based on our initial screen, we can consider multiple possible mechanisms mediating the hyperadrenocortical response in female KO mice. Because increased steroidogenesis is associated with adrenal cell hyperplasia and hypertrophy after chronic stress (56), differences in adrenal weight observed in female adrenal Bmal1 KO mice could contribute to augmented corticosterone responses. Although we have not established whether the basis for the increased adrenal mass is cell hypertrophy, hyperplasia, or both processes, the upregulation of cell cycle control genes may reflect increased cell proliferation. Upregulated genes related to cell–extracellular matrix interaction such as Itgb8 (57) and β parvin (Parvb) (58) or to angiogenesis-like vascular endothelial growth factor C (Vegfc) (59) and angiopoietin 1 (Angpt1) (60) likely would promote adrenal growth. However, our in vitro experiments, which control for adrenal cell number, show increased adrenal cell responsiveness to ACTH. These results would argue that adrenal mass alone does not account for the enhanced plasma corticosterone responses to stress. Instead, deletion of adrenal Bmal1 increases steroidogenesis through an unknown mechanism at the cellular level. We considered the possibility that Star, the clock-controlled gene encoding StAR that is required for steroidogenesis (61), would be upregulated. However, similar to male adrenal Bmal1-null mice (3), Star mRNA was not increased in adrenals from female KO mice, suggesting that StAR is not involved in the hyperadrenocortical response in female KO mice. Our observation that the thyroid hormone receptor α gene, Thra, is upregulated could reflect a role for thyroid hormone receptors in steroidogenesis. Previous work has shown sexually dimorphic expression of thyroid hormone receptor β, Thrb, in mouse adrenals that may be responsible for maintaining transient inner cortical zone cells in female adrenals and for their regression in male adrenals (62). However, adrenal expression of Thra was not sexually dimorphic (62), and stimulation of rat adrenals with thyroid hormone inhibits corticosterone responses to ACTH (63). A more promising candidate is adenosine receptor 2B, encoded by the Adora2b gene, which has been shown to stimulate rodent adrenal fasciculata cell secretion of corticosterone via a Janus kinase 2 signaling pathway (64). Although this initial genomic screen has identified possible candidates, additional investigation is warranted to identify mechanisms responsible for enhanced GC responses in female adrenal Bmal1 KO mice. Moreover, adrenals were collected at 15 minutes after acute stress. Previous work has shown that adrenal StAR and steroidogenic enzyme mRNA expression (65, 66) do not change within 15 minutes of adrenal stimulation, so it is possible that our data represent basal gene expression. However, additional experiments are required to examine whether the adrenal genes identified in our study represent basal or stress-induced gene expression.

The loss of Bmal1 resulted in augmented steroidogenic responses to acute stress, suggesting that adrenal Bmal1 acts as an attenuator of steroidogenic activity in the adrenal cortex. As a core clock gene, Bmal1, serves as a positive regulatory element in the transcriptional–translational feedback loop that is a hallmark of the molecular clock (67). In most tissues, Bmal1 deletion results in loss of clock gene rhythmicity and reduced tissue function (68–71). However, repression by BMAL1 has been observed in inflammatory monocytes (72) and in pulmonary epithelial club cells (73); in both tissues, Bmal1 deletion results in augmented inflammatory responses when triggered by infection due to the upregulation of tissue-specific chemokines. A similar phenomenon was observed in adrenal Bmal1 KO mice in which stress triggers hyperadrenocortical responses, implicating Bmal1 as an attenuator of steroidogenic function.

In summary, we have used two different mouse models to show that adrenal Bmal1 deletion results in augmented plasma corticosterone responses to acute stress in vivo and increased corticosterone responses to ACTH from adrenal cells in vitro, supporting a role for adrenal Bmal1 as an attenuator of adrenal steroidogenesis. Because the phenotype is most apparent in female mice, previous work limited to use of male mice may have failed to identify a phenotype due to sex differences. An initial genomic screen identified multiple differentially expressed adrenal genes in female KO mice that could be responsible for enhanced GC responses to stress. Additional experiments are required to determine whether the hyperadrenocortical response to adrenal Bmal1 deletion reflects a noncanonical effect on steroidogenesis or the loss of repression at the nadir of the circadian corticosterone rhythm due to loss of the adrenal molecular clock.

Acknowledgments

We thank Maggie Yang, Rachel Koehler, and Nicola Beilman, undergraduate students who provided technical assistance.

Financial Support: This work was supported in part by National Science Foundation Grant IOS1025119 (to W.C.E.), Wallin Discovery Fund Grant CON00000041231 (to W.C.E.), and National Institutes of Health Grant R01-DK100653 (to D.T.B.).

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- AS

aldosterone synthase

- Ccng2

cyclin G2

- Cdkn2a

cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A

- CTRL

control

- GC

glucocorticoid

- Itgb8

integrin β8

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- KO

knockout

- mPER2Luc

mPER2::Luciferase

- qRT-PCR

quantitative real-time PCR

- RNA-seq

RNA sequencing

- SCC

side-chain cleavage

- SCN

suprachiasmatic nucleus

- StAR

steroidogenic acute regulatory protein

- Tbc1d4

TBC1 domain for family member 4

- Thra

thyroid hormone receptor α

- Ttk

dual-specificity protein kinase

- ZT

Zeitgeber time

Additional Information

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Data Availability:

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or in the data repositories listed in References.

References and Notes

- 1. Son GH, Chung S, Choe HK, Kim HD, Baik SM, Lee H, Lee HW, Choi S, Sun W, Kim H, Cho S, Lee KH, Kim K. Adrenal peripheral clock controls the autonomous circadian rhythm of glucocorticoid by causing rhythmic steroid production. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(52):20970–20975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Oster H, Damerow S, Kiessling S, Jakubcakova V, Abraham D, Tian J, Hoffmann MW, Eichele G. The circadian rhythm of glucocorticoids is regulated by a gating mechanism residing in the adrenal cortical clock. Cell Metab. 2006;4(2):163–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dumbell R, Leliavski A, Matveeva O, Blaum C, Tsang AH, Oster H. Dissociation of molecular and endocrine circadian rhythms in male mice lacking Bmal1 in the adrenal cortex. Endocrinology. 2016;157(11):4222–4233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kloehn I, Pillai SB, Officer L, Klement C, Gasser PJ, Evans JA. Sexual differentiation of circadian clock function in the adrenal gland. Endocrinology. 2016;157(5):1895–1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Engeland WC, Massman L, Mishra S, Yoder JM, Leng S, Pignatti E, Piper ME, Carlone DL, Breault DT, Kofuji P. The adrenal clock prevents aberrant light-induced alterations in circadian glucocorticoid rhythms. Endocrinology. 2018;159(12):3950–3964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(1):27–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gallo-Payet N. 60 Years of POMC: adrenal and extra-adrenal functions of ACTH. J Mol Endocrinol. 2016;56(4):T135–T156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. O’Hara L, York JP, Zhang P, Smith LB. Targeting of GFP-Cre to the mouse Cyp11a1 locus both drives Cre recombinase expression in steroidogenic cells and permits generation of Cyp11a1 knock out mice. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e84541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yoder JM, Brandeland M, Engeland WC. Phase-dependent resetting of the adrenal clock by ACTH in vitro. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2014;306(6):R387–R393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Razzoli M, Karsten C, Yoder JM, Bartolomucci A, Engeland WC. Chronic subordination stress phase advances adrenal and anterior pituitary clock gene rhythms. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2014;307(2):R198–R205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Freedman BD, Kempna PB, Carlone DL, Shah M, Guagliardo NA, Barrett PQ, Gomez-Sanchez CE, Majzoub JA, Breault DT. Adrenocortical zonation results from lineage conversion of differentiated zona glomerulosa cells. Dev Cell. 2013;26(6):666–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jasper MS, Engeland WC. Splanchnicotomy increases adrenal sensitivity to ACTH in nonstressed rats. Am J Physiol. 1997;273(2 Pt 1):E363–E368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Purrier N, Engeland WC, Kofuji P. Mice deficient of glutamatergic signaling from intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells exhibit abnormal circadian photoentrainment. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e111449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. RRID:AB_10000794, https://scicrunch.org/resolver/AB_10000794.

- 15. Yoo SH, Yamazaki S, Lowrey PL, Shimomura K, Ko CH, Buhr ED, Siepka SM, Hong HK, Oh WJ, Yoo OJ, Menaker M, Takahashi JS. PERIOD2:LUCIFERASE real-time reporting of circadian dynamics reveals persistent circadian oscillations in mouse peripheral tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(15):5339–5346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Davidson AJ, Castanon-Cervantes O, Leise TL, Molyneux PC, Harrington ME. Visualizing jet lag in the mouse suprachiasmatic nucleus and peripheral circadian timing system. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;29(1):171–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. RRID:AB_2783720, https://scicrunch.org/resolver/AB_2783720.

- 18. RRID:AB_2783719, https://scicrunch.org/resolver/AB_2783719.

- 19. RRID:SCR_004316, https://scicrunch.org/resolver/SCR_004316.

- 20. RRID:SCR_014583, https://scicrunch.org/resolver/SCR_014583.

- 21. Didion JP, Martin M, Collins FS. Atropos: specific, sensitive, and speedy trimming of sequencing reads. PeerJ. 2017;5:e3720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pertea M, Kim D, Pertea GM, Leek JT, Salzberg SL. Transcript-level expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with HISAT, StringTie and Ballgown. Nat Protoc. 2016;11(9):1650–1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. García-Alcalde F, Okonechnikov K, Carbonell J, Cruz LM, Götz S, Tarazona S, Dopazo J, Meyer TF, Conesa A. Qualimap: evaluating next-generation sequencing alignment data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(20):2678–2679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ewels P, Magnusson M, Lundin S, Käller M. MultiQC: summarize analysis results for multiple tools and samples in a single report. Bioinformatics. 2016;32(19):3047–3048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(7):923–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Patro R, Duggal G, Love MI, Irizarry RA, Kingsford C. Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat Methods. 2017;14(4):417–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15(12):550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Soneson C, Love MI, Robinson MD. Differential analyses for RNA-seq: transcript-level estimates improve gene-level inferences. F1000 Res. 2015;4:1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. RRID:SCR_012915, https://scicrunch.org/resolver/SCR_012915.

- 30. RRID:SCR_015687, https://scicrunch.org/resolver/SCR_015687.

- 31. Huang W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4(1):44–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Engeland WC, Yoder JM, Karsten CA, Kofuji P. Phase-dependent shifting of the adrenal clock by acute stress-induced ACTH. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2016;7:81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bielohuby M, Herbach N, Wanke R, Maser-Gluth C, Beuschlein F, Wolf E, Hoeflich A. Growth analysis of the mouse adrenal gland from weaning to adulthood: time- and gender-dependent alterations of cell size and number in the cortical compartment. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293(1):E139–E146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Miller WL, Auchus RJ. The molecular biology, biochemistry, and physiology of human steroidogenesis and its disorders. Endocr Rev. 2011;32(1):81–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ulrich-Lai YM, Engeland WC. Adrenal splanchnic innervation modulates adrenal cortical responses to dehydration stress in rats. Neuroendocrinology. 2002;76(2):79–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. van der Horst GT, Muijtjens M, Kobayashi K, Takano R, Kanno S, Takao M, de Wit J, Verkerk A, Eker AP, van Leenen D, Buijs R, Bootsma D, Hoeijmakers JH, Yasui A. Mammalian Cry1 and Cry2 are essential for maintenance of circadian rhythms. Nature. 1999;398(6728):627–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zheng B, Larkin DW, Albrecht U, Sun ZS, Sage M, Eichele G, Lee CC, Bradley A. The mPer2 gene encodes a functional component of the mammalian circadian clock. Nature. 1999;400(6740):169–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ueda HR, Chen W, Adachi A, Wakamatsu H, Hayashi S, Takasugi T, Nagano M, Nakahama K, Suzuki Y, Sugano S, Iino M, Shigeyoshi Y, Hashimoto S. A transcription factor response element for gene expression during circadian night. Nature. 2002;418(6897):534–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. DeBruyne JP, Weaver DR, Reppert SM. CLOCK and NPAS2 have overlapping roles in the suprachiasmatic circadian clock. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10(5):543–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cho H, Zhao X, Hatori M, Yu RT, Barish GD, Lam MT, Chong LW, DiTacchio L, Atkins AR, Glass CK, Liddle C, Auwerx J, Downes M, Panda S, Evans RM. Regulation of circadian behaviour and metabolism by REV-ERB-α and REV-ERB-β. Nature. 2012;485(7396):123–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bae K, Jin X, Maywood ES, Hastings MH, Reppert SM, Weaver DR. Differential functions of mPer1, mPer2, and mPer3 in the SCN circadian clock. Neuron. 2001;30(2):525–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Honma S, Kawamoto T, Takagi Y, Fujimoto K, Sato F, Noshiro M, Kato Y, Honma K. Dec1 and Dec2 are regulators of the mammalian molecular clock. Nature. 2002;419(6909):841–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Engeland WC, Breault DT. Data from: Deletion of adrenocortical Bmal1 results in sex-biased gene expression. NCBI GEO 2019. Deposited 12 April 2019. Available at: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE129725.

- 44. Tajima T, Fujieda K, Kouda N, Nakae J, Miller WL. Heterozygous mutation in the cholesterol side chain cleavage enzyme (P450scc) gene in a patient with 46,XY sex reversal and adrenal insufficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(8):3820–3825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rubtsov P, Karmanov M, Sverdlova P, Spirin P, Tiulpakov A. A novel homozygous mutation in CYP11A1 gene is associated with late-onset adrenal insufficiency and hypospadias in a 46,XY patient. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(3):936–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dunn J, Scheving L, Millet P. Circadian variation in stress-evoked increases in plasma corticosterone. Am J Physiol. 1972;223(2):402–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Goel N, Workman JL, Lee TT, Innala L, Viau V. Sex differences in the HPA axis. Compr Physiol. 2014;4(3):1121–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Engeland WC, Shinsako J, Winget CM, Vernikos-Danellis J, Dallman MF. Circadian patterns of stress-induced ACTH secretion are modified by corticosterone responses. Endocrinology. 1977;100(1):138–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bradbury MJ, Cascio CS, Scribner KA, Dallman MF. Stress-induced adrenocorticotropin secretion: diurnal responses and decreases during stress in the evening are not dependent on corticosterone. Endocrinology. 1991;128(2):680–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kalsbeek A, Ruiter M, La Fleur SE, Van Heijningen C, Buijs RM. The diurnal modulation of hormonal responses in the rat varies with different stimuli. J Neuroendocrinol. 2003;15(12):1144–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Koch CE, Leinweber B, Drengberg BC, Blaum C, Oster H. Interaction between circadian rhythms and stress. Neurobiol Stress. 2016;6:57–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Dallman MF, Engeland WC, Rose JC, Wilkinson CW, Shinsako J, Siedenburg F. Nycthemeral rhythm in adrenal responsiveness to ACTH. Am J Physiol. 1978;235(5):R210–R218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sage D, Maurel D, Bosler O. Involvement of the suprachiasmatic nucleus in diurnal ACTH and corticosterone responsiveness to stress. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2001;280(2):E260–E269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Richter HG, Torres-Farfan C, Garcia-Sesnich J, Abarzua-Catalan L, Henriquez MG, Alvarez-Felmer M, Gaete F, Rehren GE, Seron-Ferre M. Rhythmic expression of functional MT1 melatonin receptors in the rat adrenal gland. Endocrinology. 2008;149(3):995–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Handa RJ, Weiser MJ. Gonadal steroid hormones and the hypothalamo–pituitary–adrenal axis. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2014;35(2):197–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ulrich-Lai YM, Figueiredo HF, Ostrander MM, Choi DC, Engeland WC, Herman JP. Chronic stress induces adrenal hyperplasia and hypertrophy in a subregion-specific manner. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;291(5):E965–E973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Akiyama SK. Integrins in cell adhesion and signaling. Hum Cell. 1996;9(3):181–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sepulveda JL, Wu C. The parvins. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63(1):25–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Pepper MS, Mandriota SJ, Jeltsch M, Kumar V, Alitalo K. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-C synergizes with basic fibroblast growth factor and VEGF in the induction of angiogenesis in vitro and alters endothelial cell extracellular proteolytic activity. J Cell Physiol. 1998;177(3):439–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Thomas M, Augustin HG. The role of the Angiopoietins in vascular morphogenesis. Angiogenesis. 2009;12(2):125–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Stocco DM. StAR protein and the regulation of steroid hormone biosynthesis. Annu Rev Physiol. 2001;63(1):193–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Huang CC, Kraft C, Moy N, Ng L, Forrest D. A novel population of inner cortical cells in the adrenal gland that displays sexually dimorphic expression of thyroid hormone receptor-β1. Endocrinology. 2015;156(6):2338–2348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lo MJ, Kau MM, Chen YH, Tsai SC, Chiao YC, Chen JJ, Liaw C, Lu CC, Lee BP, Chen SC, Fang VS, Ho LT, Wang PS. Acute effects of thyroid hormones on the production of adrenal cAMP and corticosterone in male rats. Am J Physiol. 1998;274(2):E238–E245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Chen YC, Huang SH, Wang SM. Adenosine-stimulated adrenal steroidogenesis involves the adenosine A2A and A2B receptors and the Janus kinase 2–mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase–extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling pathway. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40(12):2815–2825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Spiga F, Liu Y, Aguilera G, Lightman SL. Temporal effect of adrenocorticotrophic hormone on adrenal glucocorticoid steroidogenesis: involvement of the transducer of regulated cyclic AMP-response element-binding protein activity. J Neuroendocrinol. 2011;23(2):136–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Liu Y, Smith LI, Huang V, Poon V, Coello A, Olah M, Spiga F, Lightman SL, Aguilera G. Transcriptional regulation of episodic glucocorticoid secretion. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2013;371(1–2):62–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Reppert SM, Weaver DR. Coordination of circadian timing in mammals. Nature. 2002;418(6901):935–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lamia KA, Storch KF, Weitz CJ. Physiological significance of a peripheral tissue circadian clock. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(39):15172–15177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Sadacca LA, Lamia KA, deLemos AS, Blum B, Weitz CJ. An intrinsic circadian clock of the pancreas is required for normal insulin release and glucose homeostasis in mice. Diabetologia. 2011;54(1):120–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Xie Z, Su W, Liu S, Zhao G, Esser K, Schroder EA, Lefta M, Stauss HM, Guo Z, Gong MC. Smooth-muscle BMAL1 participates in blood pressure circadian rhythm regulation. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(1):324–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Mereness AL, Murphy ZC, Forrestel AC, Butler S, Ko C, Richards JS, Sellix MT. Conditional deletion of Bmal1 in ovarian theca cells disrupts ovulation in female mice. Endocrinology. 2016;157(2):913–927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Nguyen KD, Fentress SJ, Qiu Y, Yun K, Cox JS, Chawla A. Circadian gene Bmal1 regulates diurnal oscillations of Ly6Chi inflammatory monocytes. Science. 2013;341(6153):1483–1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Gibbs J, Ince L, Matthews L, Mei J, Bell T, Yang N, Saer B, Begley N, Poolman T, Pariollaud M, Farrow S, DeMayo F, Hussell T, Worthen GS, Ray D, Loudon A. An epithelial circadian clock controls pulmonary inflammation and glucocorticoid action. Nat Med. 2014;20(8):919–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or in the data repositories listed in References.