Abstract

Objective

The aim was to explore how UK South Asian patients living with RA interact with health care professionals and experience receiving health information in an early inflammatory arthritis clinic.

Methods

A semi-structured interview schedule, designed in conjunction with a patient partner, was used for face-to-face interviews. South Asian participants with RA were recruited from Central Manchester University Hospitals National Health Service Foundation Trust. Data were recorded and transcribed by an independent company. Data were analysed using inductive thematic analysis.

Results

Fifteen participants were interviewed. Three predominant themes emerged around participants’ experiences and interaction with health care professionals in early inflammatory arthritis clinic. First, ‘the personal experiences of RA and cultural link to early inflammatory arthritis clinic’, where participants described the impact of RA as individuals and their altered roles within their cultural setting. Second, ‘experiences of interacting and receiving information in the early inflammatory arthritis clinic’, where participants described their limited engagement with health care professionals and the quality of information discussed in the clinic. Third, ‘views on future content for early inflammatory arthritis clinics’, where participants highlighted new innovative ideas to build on current practice.

Conclusion

We believe this to be the first study to generate insight into the experiences of South Asian patients of interacting with health care professionals while attending an early inflammatory arthritis clinic. Policy directives aimed at improving access to services and delivery of information for ethnic minority groups in early inflammatory arthritis clinics should include consideration of the different roles of cultures. Professionals should be cognizant of the factors that drive health inequalities and focus on improving service delivery.

Keywords: rheumatoid arthritis, information, early inflammatory arthritis, illness representation, ethnicity

Key messages

RA information provided to South Asian patients does not allay fears around returning to employment.

The impact of RA symptoms, particularly depression and fatigue, was not fully addressed.

Clinicians dealing with RA need to be aware of widening health inequalities in rheumatology services.

Introduction

Early inflammatory arthritis clinics are the gateways for diagnosing and treating patients within a 3-month period from symptom onset [1]. The concept of early intervention has been accepted globally in rheumatology [2]. Early diagnosis and treatment has been shown to reduce the disease impact on patients [1]. Active engagement in early inflammatory arthritis clinics prepares newly diagnosed patients to be part of the shared decision-making process on their treatment plan [3, 4]. One of the most common conditions seen in early inflammatory arthritis clinics is RA. RA self-management, consisting of education and regular reviews (supporting self-management) is known to improve health outcomes and is recommended in national and international guidelines [4]. The provision of early inflammatory arthritis care in clinics across the UK is guided by evidence-based standards set out by the British Society for Rheumatology (BSR) [5] and in guidelines produced by the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) [6]; these describe processes of care in relationship to clinical management and patient monitoring, education and screening. Despite this, services still have difficulty in meeting the needs of South Asian patients [7].

The EULAR recommendations suggest that when educating patients who attend early inflammatory arthritis clinics, patient cultural diversity and individual approach should be taken into account [4]. Despite this, our general observation of early inflammatory arthritis clinics is that patients from minority ethnic backgrounds are not served to the full potential, where information is delivered mainly through English written materials [4, 8]. This may not meet the needs of certain minority ethnic patients [4]. Furthermore, in a recent BSR national audit survey assessing the delivery of care in early inflammatory arthritis clinics, we investigated the differences in ethnic groups and found that South Asian patients were noted to report greater impact of the disease on functional disability, fatigue, emotional well-being, physical well-being and coping at these early stages. This could have an impact on the way patients perceive RA treatments in the long term. Additionally, our previous cross-sectional research has also shown that South Asian patients with RA have different expectations from a treatment plan than non-South Asian patients [9–11]. Possible explanations for this include differences in health-seeking behaviours [9, 12] related to health beliefs and attitudes towards RA medicines [9]. These factors may be driven by cultural differences [10]. Therefore, the way in which self-management is accessed and delivered to these populations within early inflammatory arthritis clinics is important and timely to explore. Targeted self-management strategies may need to be developed for the ethnicity needs of this population. This study is the first to explore how UK South Asian patients with RA interact with health professionals and experience receiving health information in an early inflammatory arthritis clinic. Patients’ views on the role of culture in provision of information, support and self-management approaches have been explored. We also report patient-derived recommendations that can help to inform UK and global rheumatology policies to improve patient engagement in early inflammatory arthritis clinics.

Methods

A pragmatic approach was identified as the most appropriate method to gain an understanding of living with RA and exploring how South Asian patients interact with health care professionals in early inflammatory arthritis clinics and experience receiving health information. Pragmatism is guided by the researchers’ desire to produce socially useful knowledge and takes a bottom-up approach [13]. The data have been reported in line with consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research [14]. Participants originating from the South Asian continent were invited to participate in individual face-to-face semi-structured interviews. The term South Asian here applies to people originating from the Indian subcontinent, for example, India and Pakistan [15]. Participants were recruited from Central Manchester University Hospitals National Health Service (NHS) Foundation Trust, UK. Participants with clinician-diagnosed RA were invited to participate in the study by clinical staff. Purposive sampling of patients was identified during attendance at the early inflammatory arthritis clinic between January and June 2018. Participants were recruited with a broad range of age, occupation and disease duration. We invited participants into the study who had experienced an interaction with a health care professional in early inflammatory arthritis clinics at the time of diagnosis and starting medical treatment in secondary care. Patient information was given during attendance at the early inflammatory arthritis clinic. Interviews were arranged by the researcher (K.K.) with participants who had agreed to take part in the study. K.K. has extensive experience in conducting qualitative research and is a female researcher from an Indian background. K.K. was able to communicate in English, Urdu and Punjabi during the interviews and built rapport with participants. A pre-study questionnaire captured demographic data and DAS (see Table 1). A topic guide was developed based on a literature review and discussions with the research team, including the patient research partner (J.R.) (see Table 2). The patient research partner (J.R.) was a female with a diagnosis of RA who has been living with the condition for past 5 years. Her experiences of both interacting with the early inflammatory arthritis clinics and living with the condition were valuable in developing the topic guide. Interviews followed an iterative process [16], with new concepts that emerged during data analysis being explored in subsequent interviews [17]. Ethics approval was granted by the South West-Frenchay Research Ethics Committee (reference 234815), and written informed consent was obtained from each patient before interview.

Table 1.

Demographic data of patients interviewed

| Gender All female | Level of education | Age | Employment status | Disease duration | Current medication and DAS28 at the time of recruitment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | Primary | 61 | Retired | 2 years | DMARDs, CSs and biologic agents (score 3.5) |

| Patient 2 | University | 31 | Retired owing to RA | 9 months | DMARDs and CS agents (score 4.6) |

| Patient 3 | Secondary | 43 | Factory worker | 3 years | DMARDs and biologic agents (score 4.3) |

| Patient 4 | University | 33 | Lawyer | 1.5 years | DMARDs and biologic agents (score 3.8) |

| Patient 5 | University | 42 | Teacher | 2.5 years | DMARDs and biologic agents (score 2.89) |

| Patient 6 | Primary | 50 | Home maker | 1 year | DMARDs (score 4.0) |

| Patient 7 | Secondary | 49 | Retired due to RA | 3 years | DMARDs and biologic agents (score 4.6) |

| Patient 8 | Primary | 29 | Home maker | 1.5 years | DMARDs and biologic agents (score 4.1) |

| Patient 9 | Secondary | 42 | Factory worker | 6 months | DMARDs (score 4.8) |

| Patient 10 | Primary | 38 | Retired owig to RA | 2.5 years | DMARDs and biologic agents (score 5.25) |

| Patient 11 | Secondary | 44 | Sales manager | 3 years | DMARDs and biologic agents (score 2.45) |

| Patient 12 | Secondary | 48 | Office worker | 2.5 years | DMARDs CSs and biologic agents (score 3.2) |

| Patient 13 | University | 26 | Legal officer | 7 months | DMARDs and CSs (score 4.35) |

| Patient 14 | Primary | 50 | Home maker | 1 years | DMARDs, CSs and biologic agents (score 3.67) |

| Patient 15 | Secondary | 38 | Retired owing to RA | 2 years | DMARDs, Steroids and biologic agents (score 3.78) |

DMARDs: biologic: advanced therapy; DAS28 >5.1 implies active disease, <3.2 low disease activity and <2.6 remission. DAS was assessed around the time of interview.

Table 2.

Patient quotes to illustrate the findings

| Quotes relating to: the personal experiences of RA and cultural link to early inflammatory arthritis clinic |

| Q1. When they told me about this disease I was really very upset. For weeks I didn’t get why the swelling was so aggressive. I felt very helpless and resented this part of life because it affected my hands mainly. I wasn’t able to do much of my tasks; that really did bring my mood down, and I felt depressed. [English speaking, teacher] |

| Q2. The shock of it all was too much and I couldn’t believe how quickly it changed my life. I had to stop work then tried controlling the symptoms but never was fully back at work. The condition changed everything in my life. [English speaking, legal officer] |

| Q3. I had a career ahead of me, but I have had to pass on all my big responsibilities to my colleagues. That has left me feeling down and undermined a bit at times. [English speaking, sales manager] |

| Q4. I worked in a factory. First, I had to bring my hours down, but gradually the work wasn’t going to fit in this very up and down disease. One day I was good and next all my joints would be swollen. [Non-English speaking, factory worker] |

| Q5. I feel very weak now to deal with this. I feel as if I don’t have the energy to deal with the unfamiliar pattern of symptoms. [Non-English speaking, retired] |

| Q6. I’m managing rheumatoid arthritis between two worlds. I am trying to understand what’s going on with my body and on the other hand my husband isn’t being supportive. You see, in our culture, having a long-term disease is like a punishment because our family can’t understand why treatments don’t work. [Non-English speaking, factory worker] |

| Q7. You don’t get the same respect when you have an illness as you would otherwise. It is battle in changing the role. [English speaking, legal officer] |

| Q8. You see, in this country it is alright if you are ill, and people or their families will adapt. But in our culture it is very difficult to be in that role. Like in Pakistan it is not welcomed to have long-term illness. The community doesn’t understand as it does in the western world. So it is not easy for us to adapt to the illness; we have to show we are well. [English speaking, retired owing to RA] |

| Q9. I am only young and now I can’t do my work like I used to. I had to give up my job because I couldn’t balance the two things [house and work]. So my husband said it is not right for me not to pay attention to my house. I have to do my duty at home so I feel it is really difficult in our culture to put the two views of western and our views together. [English speaking, retired owing to RA] |

| Q10. My children really support me. My husband didn’t at the start but now he does support me. [Non-English speaking, retired] |

| Q11. When I tell my husband the symptoms are not fully controlled, he does get fed up. He has said to re-marry, which makes me feel very invalid and not valued as a person. It wasn’t my choice to have the disease. [Non-English speaking, home maker] |

| Q12. I know I shouldn’t feel like this but I do think that I am alone in this journey trying to cope because the community doesn’t like to hear from people who are not well. They can be very harsh. [English speaking, teacher] |

| Q13. I try not to attend family functions because I know what will happen. I get asked about my condition and I don’t feel I want to discuss it so I make excuses not to go. I will sit there very quietly; it makes you feel you are alone in this. [English speaking, retired owing to RA] |

| Q14. I don’t think my husband really understands my symptoms and why I have them despite being on treatment. Sometimes I feel so isolated in this disease. [English speaking, teacher] |

| Quotes relating to: experience of interacting and receiving information in the early inflammatory arthritis clinic |

| Q1. When I was told by my GP [general practitioner] that I was going to see the specialist at the hospital, I thought great, now I was going to get better. I thought I had a very good doctor looking after me and I was told I had the best treatment. After a few months I was still the same. I was disappointed with the information. [English speaking, factory worker] |

| Q2. At the start all was going well. I had my doctor giving me these tablets [CSs] and information on this and how it would make me better. I was really well on them, I was like a new person, but after 9 months things went worse and I am still the same when I first started with the symptoms. But I know now they can’t cure this. [Non-English speaking, home maker] |

| Q3. I was really happy with my treatment. My doctor was trying medicines and I was doing the housework and even used to go out for walks. I used to follow the advice by him. I thought I was really going to get better. I don’t know what happened. After that, I was ill again. I wasn’t getting an answer from my doctor why this came back, and since then it never got better. I kind of lost trust now. I feel the information I was given didn’t match with disease coming back. [Non-English speaking, home maker] |

| Q4. At the beginning, there were so many blood tests and information on that. I thought this is great, they are getting me better. But slowly I realized that focus on blood tests was just on monitoring me, which I understand, but I felt that staff could have talked to me more about what I can do myself. At the end, we all learn it is never going to go away. [English speaking, sales manager] |

| Q5. I would have wanted to know more information on what I could have done. There was a massive focus on blood tests; every visit was about blood tests. This sort of gives you false hope really. [English speaking, lawyer] |

| Q6. What is fatigue? Never heard of it! [English speaking, sales manager] |

| Q7. I didn’t know about fatigue. I don’t really know we manage this. This was not discussed with me. [English speaking, office worker] |

| Q8. The leaflets are given, but what good are they? I don’t see how this can help us, like I have different things I have to deal with in my family. I think this information is based for English people. [Non-English speaking, home maker] |

| Q9. The leaflets are not good for me to understand my long-term life with this disease. [Non-English speaking, retired owing to RA] |

| Q10. I had pictures shown to me on the computer. The nurse explained why the swelling was coming to my joints. I could see that they were trying to stop the swelling getting worse. She would show me the same pictures that reminded me what was being achieved. [English speaking, retired owing to RA] |

| Q11. I don’t think the doctor understands my culture. I had lots of changes to my life, and none of this was discussed. When I was going through a very rough patch with my husband, he couldn’t understand my illness. I felt no point saying this to a doctor who is not from culture. [Non-English speaking, retired owing to RA] |

| Q12. Personally, I don’t think doctors from other backgrounds can understand other cultures. I didn’t discuss much about this. Nor was it asked like how has my role changed and did I need help in understanding that. [English speaking, retired owing to RA] |

| Q13. I felt bad to discuss that my family were not supporting me. I know that I could have talked about it, but I just didn’t want everyone to know all this so didn’t get much help really. [Non-English speaking, home maker] |

| Q14. What I don’t understand is that a doctor knowing this isn’t going to be cured or go away completely – why don’t they discuss what patients can do to help themselves? Like in other diseases, there is a lot about lifestyle changes, but I felt I wasn’t doing enough to help but kept thinking there isn’t anything else I can do. [English speaking, factory worker] |

| Q15. I don’t even know what others in the team do. I must say I didn’t go to the exercise clinic [meaning physio]. I didn’t think they could help my swelling. [Non-English speaking, home maker] |

| Quotes relating to: views on future content for early inflammatory arthritis clinic |

| Q1. You see, if I was told all the things I can do at the beginning it would have made me feel part of the managing the disease. We can’t rely on taking medication alone. Like this tiredness; I get it very bad. You said ‘fatigue’. If I can know what to do with this, I can start doing it. That will keep me thinking that I am psychologically taking part, but at the moment I don’t think I am taking part. [English speaking, factory worker] |

| Q2. Like in diabetes patients, they know how well they are doing. They always try to keep their sugar level down. Is there anything I can do to keep the swelling down? I think if my doctor told me more, like the sugar level, I can try to tell myself, look I am alright. [English speaking, retired owing to RA] |

| Q3. I hear my friends say look my condition is under control. They know about the sugar level. Doesn’t this condition get under control? We need to know all that information. [English speaking, sales manager] |

| Q4. Do you even know how much our Asian people try addition management with being diabetic? They take the tablet but also keep an eye on their sugar level. The problem is that this country isn’t good with weather; otherwise, people would walk and exercise. But I do know lots of people who know that the only way to control their diabetes is to control what they eat. I myself have found that eating or not eating certain things do add to disease control. So put this information to patients. Because people think, or even me when I started, my problem is in my joints, so the swelling can be only be cured by treatment. But you can make it worse by putting the wrong things in your body. [Non-English speaking, home maker] |

| Q5. So the diabetic patient, like you said earlier, would know that they need to lose weight, cut on sugar and fried food. In our Asian culture, we have lots of sweet things at wedding parties, like, so that patient will be aware. When I look back, I was told that I need blood tests. I was shown pictures, but what I could do to help wasn’t really clear. [English speaking, retired owing to RA] |

| Q6. Okay, so now when I look back now, it is long-time disease like the sugar disease, like that kind of thing. So you can tell patients, like, it is like sugar disease, it will be better one day and not better on another day. I think the way I have made myself understand this disease, like the sugar disease, like the sugar disease. [Non-English, factory worker] |

| Q7. So I think for the future patients, doctors and nurses should inform us that this is like that sugar control. [English speaking, teacher] |

| Q8. Like in sugar disease, they say oh my sugar level is good, and I will say to my friend what is your level? She will say, oh mine is 4.5 and it remains on that now for last 5 months. You can tell patients what they should do to control this condition. I know physio gets mentioned, but it should be explained that it is part of getting control like diabetic patients do. [English speaking, office worker] |

| Q9. My friend has got her sugar level under control. She will say, I cut down on fatty things and sugar things. But here we could control our fatigue if that can control our mood, can’t we? But that’s never discussed. [English speaking, retired owing to RA] |

| Q10. The pain is big in my condition and sugar level is big in diabetes, but if we look at diabetic patients, they are really on the go to control their condition. Like physio can be part of my clinic when I see the nurse, why separate? I can know how she will help, and we can meet again to make exercise plan, but physio needs to be at my clinic appointment. [English speaking, sales manager] |

| Q11. Please can you make sure that in the future we get some information about diet. Like my Asian people tell me that you should stop red meat and fatty heavy food, some other things don’t suit me. So what they should have said to me at the start, to keep a diary and watch the things that upset me. I asked a number of times about the diet, and they said oh no you can eat, but when I tried my relative suggestion, I found that helped my pain. If I was a diabetic, a dietitian would have spoken to me. Why don’t they in this clinic? [Non-English speaking, home maker] |

| Q12. I think staff should discuss with me the impact of this. I don’t think they talk about this much, maybe because of time or is it they don’t want to. I think there should be an open discussion how this condition is mentally affecting me. [English speaking, lawyer] |

| Q13. I don’t think there is enough discussion about this fatigue or on how it should be managed. Again, if I was a diabetic I would have been told all the points to manage with support. Even depression, no one wants to talk about it. [English speaking, legal officer] |

| Q14. This should also be like the diabetic plan. It is very important, and people need to know of this early. Not 1 year down the diagnosis. I do think if people understood the reasons, and in Asian patients it might take long to understand, but tell us in the form it makes sense. [Non-English speaking, retired owing to RA] |

| Q15. It might not be possible for staff, but it would be nice if they can understand where I am coming from. Like training or something. I don’t think they want to discuss, but that means I have to either try to manage myself or it can be very isolating. [English speaking, sales manager] |

Three interviews were co-facilitated by the patient research partner (J.R.). The presence of the patient research partner at a few interviews provided her with an opportunity to obtain an insight into the patients’ stories, which later helped in understanding the richness of the data collected. The interviews lasted ∼1 h. They were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim by an independent transcription company.

Data analysis

Thematic analysis is known as a method in its own right that is not bound to any theoretical framework, complementing the pragmatic approach that we took in this study [13]. Bearing this in mind, the data of this study were analysed using inductive thematic analysis, a method for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns (themes) [18] within data without trying to fit it into a pre-existing coding frame or the researcher’s preconceptions. For example, the researcher focused on the patient partner’s suggested topics and, during the interview, concepts that were raised by patients during the interview were studied in detail. The transcripts were typed by an independent company with familiarity in translating material in different languages. Transcripts in Urdu and Punjabi were translated into English by trained and experienced employees of the company.

The data analysis approach involved each interview being analysed individually [16] and compared with earlier or subsequent interviews to determine the perspectives of South Asian participants on the delivery of information in early inflammatory arthritis clinics. A multidisciplinary group with different expertise took part in conducting individual data analysis. A rheumatologist (A.A.), health psychologist (R.J.S.), health literacy expert (J.A.) and patient partner (J.G.) discussed the emerging analysis, enhancing the trustworthiness of the findings [16]. This triangulation exercise allowed the team to view data from different perspectives. The patient research partner (J.R.) was able to reflect on the findings generated from this study and her past experiences of engaging with early inflammatory arthritis clinics. Moreover, J.G. resonated with findings after receiving a diagnosis 5 years ago. Memos that summarized the findings were sent to individual patients who took part in the study for agreement.

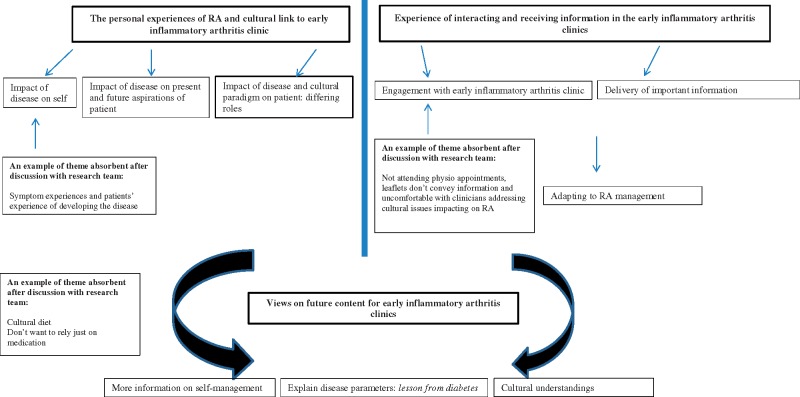

The first author (K.K.) analysed all the transcripts, where data were subjected to line-by-line coding. The patient research partner independently coded three transcripts to develop reliable and inclusive themes informed by multiple perspectives. Discussion of the coding framework took place between researchers (K.K., A.A., R.J.S. and J.A.) and the patient research partner (J.G.). Coding categories that lacked concordance were discussed and absorbed into the coding framework (Fig. 1). The initial codes were then grouped into the most noteworthy and frequently occurring categories. The core themes extracted and presented here focus on the interaction of patients with early the inflammatory arthritis clinic. Initially, 190 codes were identified, which were then grouped into 40 categories and finally combined into three overarching themes. These three predominant themes enhanced our understanding of patients’ experiences with the early inflammatory arthritis clinic. See Fig. 1 for a thematic diagram of South Asian patients’ experiences of interacting with health care professionals and their experience of receiving information in the early inflammatory arthritis clinic.

Fig. 1.

Thematic diagram showing the interaction of patients with health care professionals in the early inflammatory arthritis clinic

Results

In total, 25 patients were approached to take part in the study. Of those, 10 declined owing to the time commitment. Fifteen patients participated in the study, with a mixture of age (range of 26–52 years) and disease duration (range of 1–36 months). All participates were female. Male patients were approached, but because of the time commitment they did not want to take part. Please see Table 1 for further details. Ten interviews were conducted in English, four were in Urdu and one in Punjabi. Patient quotes are presented in Table 2 to illustrate the findings.

The personal experiences of RA and cultural link to early inflammatory arthritis clinic

The impact of RA at the initial stages of the disease was substantial for majority of the participants, including the initial shock of the diagnosis, followed by reported low mood, anxiety, depression and resentment at feeling limited in physical capabilities, especially during severe episodes of disease flare (Q1). Immediate feelings after diagnosis included continued shock and anger, and feelings of ‘life is being unfair’. Importantly, many reported stopping work at the early stages of the disease or reducing working hours (Q2). Work was reported to be a particularly important area relating to self-esteem regardless of occupation (Q3 and Q4). Many expressed financial concerns related to limitations in future employment options, which appeared to have a negative impact on their overall views about the future. Some participants reported having to stop work of their own accord, whereas others stated that a decision from their family was endorsed in order for the individual to prioritize family and house duties. For some younger participants, this altered their life ambitions and aspirations for the future.

There was a self-perception among some participants that RA was difficult to deal with, both mentally and physically (Q5). The change for the future particularly impacted on how the individuals were viewed within their family circle or community (Q6 and Q7). Many participants reported having to be dealing with ‘two worlds’, the disease and cultural expectations of a female individual (Q6). Younger participants born abroad expressed difficulty in managing the western society view on illness with those from their country of origin (Pakistan or India) (Q8). Managing these views presented challenges for younger individuals (Q9). Some older participants expressed family support to be of paramount importance (Q10), and others felt ‘treated as an invalid and less valued’ because of their illness (Q11). To preserve their identity and role after the illness, some participants were particularly keen not to disclose their illness to their community. Some younger participants felt helpless owing to lack of family support and felt alone in dealing with RA (Q12). Participants often felt that their RA set them apart from healthy family members and increased their vulnerability to social isolation and loneliness (Q13). Some younger participants expressed the view that their varied symptom pattern was difficult to explain to family members and, particularly, to spouses. This was brought about by their withdrawal from, or loss of, social activities and the perception that other people could not understand the consequences of RA (Q14).

Examples of patient quotes:

Q1. When they told me about this disease, I was really very upset. For weeks, I didn’t get why the swelling was so aggressive. I felt very helpless and resented this part of life because it affected my hands mainly. I wasn’t able to do much of my tasks. That really did bring my mood down, and I felt depressed. [English speaking, teacher]

Q2. The shock of it all was too much, and I couldn’t believe how quickly it changed my life. I had to stop work, then tried controlling the symptoms but never was fully back at work. The condition changed everything in my life. [English speaking, legal officer]

Q3. I had a career ahead of me, but I have had to pass on all my big responsibilities to my colleagues. That has left me feeling down and undermined a bit at times. [English speaking, sales manager]

Experience of interacting and receiving information in the early inflammatory arthritis clinic

Many participants reported a feeling of relief to have attended an early inflammatory arthritis clinic. Participants reported high expectations towards their health care professional and treatment plan (Q1 and Q2). However, many reported that after attending an early inflammatory arthritis clinic and receiving treatment for some months, their personal desired goal was not met (Q2). Many participants reported an initial excitement on starting treatment and a good level of engagement with the service and health professional, but soon after lost hope of getting symptoms under control (Q3 and Q4). The majority of the participants reported feeling that consultations were unbalanced, with a disproportionate focus on blood monitoring rather than individual participants’ issues around quality of life (Table 2, Q4 and Q5). About half of the participants did not know about fatigue associated with RA and were uncertain about how to manage this (Q6 and Q7). The majority of participants expressed the view that delivery of disease-related information by leaflets often lacked cultural views or perspectives and, importantly, appeared to be written only in English (Q8&9). Those participants who reported having had disease-related information in visual formats found it useful in understanding the disease and the reasons for recurrent symptoms (Q10).

Participants highlighted some barriers in discussing areas with their clinicians, such as their changing role within the family, raised anxiety, depression and concern for the future (Q11 and Q12). Participants felt that clinicians from a White background might not understand their views and experiences and that this was an important element for them (Q12). Their own reluctance to discuss the negative emotional impact of RA led many not to ask for help or clarification around important areas and preferring to manage their own symptoms, but they agreed that discussion could be useful (Q13). The majority of the participants felt they had a minimal part to play in adapting to RA owing to lack of information on lifestyle changes and self-management strategies (Q14). Many participants reported a lack of understanding of the role of other multidisciplinary team members in managing their symptoms. For example, many admitted not knowing about or attending physiotherapy (Q15). The reasons for this related to lack of awareness of the multidisciplinary team members and their role in assisting the patient to manage symptoms.

Examples of patient quotes:

Q4. At the beginning, there were so many blood tests and information on that. I thought, this is great, they are getting me better. But slowly I realized that focus on blood tests was just on monitoring me, which I understand, but I felt that staff could have talked to me more about what I can do myself. At the end, we all learn it is never going to go away. [English speaking, sales manager]

Q5. I would have wanted to know more information on what I could have done. There was a massive focus on blood tests every visit was about blood tests. This sort of gives you false hope really. [English speaking, lawyer]

Q6. What is fatigue? Never heard of it! [English speaking, sales manager]

Q7. I didn’t know about fatigue. I don’t really know we manage this. This was not discussed with me. [English speaking, office worker]

Views on future content for early inflammatory arthritis clinic

The majority of the participants described constructive ways of coping with the psychological impact of their RA and made clear suggestions regarding a range of approaches that they might find helpful (Q1 and Q2). Some participants had co-morbidities, such as diabetes, and many participants when asked about future changes to the delivery of information and engagement made a positive reference to the diabetic model of care (Q3 and Q4). The diabetic model of care was also evident and understandable for family and friends (Q3 and Q4). Participants highlighted a desire to know the level of disease severity during their follow-up clinics in a similar way to understanding ‘sugar level reading’ in diabetes care. Participants’ preferences were informed from their own experiences of having diabetes and from supporting family and friends with diabetes (Q5 and Q6). Participants reported that knowing a disease severity marker would help them to quantify the severity of symptoms and would give them encouragement to stay engaged in their RA management (Q7 and Q8). The desire to receive self-management strategies for adaptation was also compared with the diabetic model. Participants presented stories about how changes in behaviour towards lifestyle adaptation have led people with diabetes to control their ‘sugar level’ better. There was little evidence of shared decision-making in our interviews. However, our participants identified that having information on disease activity from their rheumatology health care professional would make them feel a valued member in their shared care decision-making (Q9–Q11).

Most of the participants reported the need to provide an open opportunity where they could discuss psychological aspects of RA and how this might be impacting on their lives (Q12). Participants felt the need for dialogue around depression and fatigue; this was not covered routinely in the early inflammatory arthritis clinics and, as such, was not well understood by our participants. Participants expressed their view that professional support for discussing and managing fatigue was minimal because their main focus was on assessing physical problems. Participants highlighted a need for better understanding from health care professionals regarding their cultural norms and how these might influence and impact upon their ability to deal with their RA (Q13–Q15).

Examples of patient quotes:

Q12. I think staff should discuss with me the impact of this. I don’t think they talk about this much, maybe because of time or is it they don’t want to? I think there should be an open discussion how this condition is mentally affecting me. [English speaking, lawyer]

Q13. I don’t think there is enough discussion about this fatigue or on how it should be managed. Again, if I was a diabetic I would have been told all the points to manage with support. Even depression, no one wants to talk about it. [English speaking, legal officer]

Q14. This should also be like the diabetic plan. It is very important, and people need to know of this early, not 1 year down the diagnosis. I do think if people understood the reasons, and in Asian patients it might take long to understand, but tell us in the form it makes sense. [Non-English speaking, retired owing to RA]

Q15. It might not be possible for staff, but it would be nice if they can understand where I am coming from. Like training or something. I don’t think they want to discuss, but that means I have to either try to manage myself or it can be very isolating. [English speaking, sales manager]

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first qualitative study to have explored the experiences of South Asian participants’ interaction with health care professionals and receiving information within early inflammatory arthritis clinics. The results of this study pose interesting challenges and opportunities for health care professionals conducting early inflammatory arthritis clinics. Participants reported their experiences of interacting with health care professionals and receiving health information in early inflammatory arthritis clinics and the associated psychological and physical impact. Participants’ initial interactions with the early inflammatory arthritis clinic were positive, with high expectations of both clinicians and treatments. However, participants reported a decline in trust of clinicians if full symptom control was not achieved. Possibly, participants might have unrealistic expectations of symptom control and, in some cases, might have received insufficient information. These expectations needed to be explored and supported more effectively by the health care professionals. Participants’ decisions about staying in employment were found to cause concern. Moreover, self-esteem and future aspirations were also altered. These findings fall in line with studies that have explored the impact of RA on employment but did not include a minority ethnic population [19].

Adapting to RA, both psychologically and physically, appeared to impact more on the younger as opposed to the older participants, which was explained, in part, by juggling roles within the family and RA limiting their employment opportunities. Low mood, anxiety, depression, fatigue and fear for future consequences were themes common to all. Fatigue, in particular, was strongly related to difficulties in returning to employment and was also linked with financial concerns, with resultant negative impact on self-esteem. There is evidence to support this as a widespread issue in ‘all’ RA patients [20]. Our study noted a difference here, where adaptation to RA for younger participants posed a challenge, often related to the cultural setting. For example, participants with RA who were born abroad and living in the UK appeared more conscious of their role within the family and reported RA to be a real challenge for them to fit within their cultural framework now that RA had necessitated an alteration in their role. This has been noted in diabetic South Asian patients [21]. In our study, participants reported that they felt less valued by their family members because of the illness. Our study indicated that older participants were better supported by their families with daily activities than younger participants. These results appear in line with the cultural framework, where elders are respected [22]. Our study also revealed that the early personal impact of disease was not discussed fully in the clinic with the participants. Moreover, our study indicates that within the early inflammatory arthritis clinics there was more emphasis and time spent on disease monitoring, leaving participants to seek their own self-management strategies. Self-management strategies were, however, important for South Asian participants to understand, and further time exploring how these could benefit personal lifestyles and approaches was seen as beneficial.

People from ethnic minority backgrounds may be perceived as disengaging, when the problem is generally within the service delivery that fails to meet the needs of participants. Equitable access to appropriate disease-related information has been shown to have a positive effect on patients’ quality of life [4]. Previous studies have demonstrated that preparing patients with a long-term condition requires a clear understanding and should include patients’ perspectives during consultations and a good patient–health professional relationship [4]. Moreover, it is evident that patients who are well informed and engaged in their long-term condition do well in terms of clinical and quality of life outcomes [4]. The well-prepared patient has further been demonstrated by psychological models that aid our understanding of patients’ behaviours towards engaging with treatments and disease management. Models such as Leventhal’s self-regulatory model [23] and Horne’s necessity concern framework [24] reveal treatment beliefs to be related to adherence and are consistent with findings in a range of chronic illnesses [24]. In line with these models, our results indicate that patients value the rationale and information around disease, treatments and long-term management very early on.

The quality of service provision, appropriate delivery of information and open discussion with health care professionals about managing RA might improve outcomes for South Asian patients with RA during the early stages of RA. Our study reviewed not only the resolution for more innovative ideas but also found that participants were willing to adapt to a certain amount of pain and to cope with RA symptoms, mastering new skills. However, in this process they also emphasized the desire for greater patient involvement and partnership. Similar to our previous work [25], participants demonstrated that visual feedback was better at explaining the disease process than leaflets alone. Again, this appears to be in line with psychological models where patients attempt to see the problem and rationalize decisions around their treatments as the resolution [24]. Leaflets were reported to have a limited effect on participants’ understanding. Moreover, they were not helpful for non-English speaking persons.

Some of the significant recommendations made by South Asian participants with RA were around the models of care delivered in the diabetic setting. Participants in our study highlighted their observation of diabetic patients being more actively involved in their disease management. They felt that the diabetic model included cultural concepts that were better understood by patients. They understood and particularly valued a specific disease parameter, such as ‘sugar level’, in diabetic care, and this concept could be translated well into the RA setting, using DAS. Previous research exploring patients’ value of DAS among non-South Asians revealed that they felt DAS to be a clinical objective measure [26]. In our study, nearly all our participants expressed the desire to quantify their disease activity. Our data suggest that getting South Asian patients on board, showing the change in the disease outcome measures, trying to explain the nature of the disease, plans of therapy and the possible impact on the patient’s life would leave a positive impression. This method, starting the story from the beginning, has been used by the diabetic community [27], where the data suggest that patient and clinician engagement is more likely to be effective if set in cultural frames within which behavioural choices are made. In our study, adding the visual feedback approach to the participants’ management might have an impact on their understanding and level of engagement. Open discussion about depression, fatigue and its early self-management could also help patients to stay connected for longer [4]. Our data suggest that a tighter collaborative combined multidisciplinary clinic approach at the early stages and incorporating new ideas from other health care professionals and models of care will better serve patients from ethnic minority backgrounds. Collaborative combined clinics are traditionally conducted among medical specialities. Our data suggest that there is an opportunity for nurse-led clinics to consider such models. Close working with an interdisciplinary team approach in diabetes has shown patients to achieve their glycaemic control more quickly than the standard approach [28]. These data suggest an opportunity to think outside the box for early inflammatory arthritis clinics.

This study exploring the experiences of a minority ethnic group resulted in a rich description of experiences of RA and service provision in early inflammatory arthritis clinics. The methodological approach also enabled us to identify the direct, rather than perceived, ideas, this study exemplifies, by interviewing South Asians. There were limitations to the study. For example, there was no representation from male participants in the study; therefore, their perspectives about the impact of early stages of RA on their lives could have differed from female perspectives. The current research exploring White British male patients’ experiences of coping styles and support preferences reported concepts linked to masculinity [29]. This could have been the pattern in South Asian males. The participants were recruited from one hospital, and it would have been useful to recruit patients from several rheumatology centres.

These novel data focusing on South Asian patients living with RA suggest that patients have a range of experiences from developing symptoms to its management. There is a realistic possibility that many South Asian patients living with RA are not being served adequately in early inflammatory arthritis clinics. Further research should investigate the models that better serve South Asian patients’ needs, particularly one that includes the cultural framework. Patients have made recommendations that might help inform inclusive health care policies developed by BSR, Public Health England and the NHS Musculoskeletal Framework. The needs of South Asian patients must be considered when designing early inflammatory arthritis clinics and developing policies related to early inflammatory arthritis clinics. Rheumatology health care professionals need to recognize the limitations of existing early inflammatory arthritis clinics and be receptive to initiatives focused on improving service delivery for South Asian Patients.

Funding: This study was funded by the British Society for Rheumatology [grant number 17-1420].

Disclosure statement: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We thank all patients for taking part in the study, and staff at Central Manchester University hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. We thank our patient research partner (Joti Reehal) for assisting us with study design, development of interview guide and data analysis. K.K., R.J.S., J.A. and A.A. developed the protocol for the study. K.K. conducted the study, analysed the data and prepared the manuscript. R.J.S., J.A. and A.A. verified the data analysis. R.J.S., J.A. and A.A. modified the drafted manuscript. K.K. is the guarantor of this paper.

References

- 1. Smolen JS, Landewé R, Breedveld FC et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:964–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Keystone E.. Superior efficacy of combination therapy for rheumatoid arthritis: fact or fiction? Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:2975–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Bijlsma JW et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:631–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zangi HA, Ndosi M, Adams J et al. EULAR recommendations for patient education for people with inflammatory arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:954–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Luqmani R, Hennell S, Estrach C et al. British Society for Rheumatology and British health professionals in Rheumatology guideline for the management of rheumatoid arthritis (the first two years). Rheumatology 2006;45:1167–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. The management of rheumatoid arthritis in adults. London: NICE guidelines, 2009.

- 7. Kumar K, Raizada SR, Mallen CD, Stack RJ.. UK-South Asian patients' experiences of and satisfaction toward receiving information about biologics in rheumatoid arthritis. Patient Prefer Adherence 2018;12:489–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Adepu R, Swamy MK.. Development and evaluation of patient information leaflets (PIL) usefulness. Indian J Pharm Sci 2012;74:174–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kumar K, Raza K, Nightingale P et al. Determinants of adherence to disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs in White British and South Asian patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a cross sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2015;16:396.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kumar K, Gordon C, Toescu V et al. Beliefs about medicines in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus: a comparison between patients of South Asian and White British origin. Rheumatology 2008;47:690–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kumar K, Gordon C, Barry R et al. “It's like taking poison to kill poison but I have to get better”: a qualitative study of beliefs about medicines in RA and SLE patients of South Asian origin. Lupus 2011;20:837–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kumar K, Daley E, Carruthers DM et al. Delay in presentation to primary care physicians is the main reason why patients with rheumatoid arthritis are seen late by rheumatologists. Rheumatology 2007;46:1438–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ.. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res 2007;42:1758–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J.. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007;19:349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bhopal R. Medicine and public health in a multiethnic world. J Public Health (Oxf) 2009;31:315–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Braun V, Clarke V.. What can “thematic analysis” offer health and wellbeing researchers? Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 2014;9:26152.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dixon-Woods M, Fitzpatrick R, Roberts K.. Including qualitative research in systematic reviews: opportunities and problems. J Eval Clin Pract 2001;7:125–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dixon-Woods M, Agarwal S, Jones D, Young B, Sutton A.. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005;10:45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Barrett EM, Scott DG, Wiles NJ, Symmons DP.. The impact of rheumatoid arthritis on employment status in the early years of disease: a UK community-based study. Rheumatology 2000;39:1403–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dures E, Almeida C, Caesley J et al. Patient preferences for psychological support in inflammatory arthritis: a multicentre survey. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:142–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lawton J, Parry O, Peel E, Douglas M.. Diabetes service provision: a qualitative study of newly diagnosed Type 2 diabetes patients' experiences and views. Diabet Med 2005;22:1246–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lawton J, Ahmad N, Peel E, Hallowell N.. Contextualising accounts of illness: notions of responsibility and blame in white and South Asian respondents' accounts of diabetes causation. Sociol Health Illn 2007;29:891–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Leventhal Nerenz DR, Steele DJ.. Illness representations and coping with health threats In: Taylor SE, Singer JE, eds. Handbook of psychology and health. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, 1984: 219–52. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Horne R, Chapman SC, Parham R et al. Understanding patients' adherence-related beliefs about medicines prescribed for long-term conditions: a meta-analytic review of the necessity-concerns framework. PLoS One 2013;8:e80633.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kumar K, Raza K, Gill P, Greenfield S.. The impact of using musculoskeletal ultrasound imaging and other influencing factors on medication adherence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a qualitative study. Patient Prefer Adherence 2016;10:1091–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. van Tuyl LH, Sadlonova M, Hewlett S et al. The patient perspective on absence of disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis: a survey to identify key domains of patient-perceived remission. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:855–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Greenhalgh T, Clinch M, Afsar N et al. Socio-cultural influences on the behaviour of South Asian women with diabetes in pregnancy: qualitative study using a multi-level theoretical approach. BMC Med 2015;13:120.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McGill M, Blonde L, Chan JCN et al. The interdisciplinary team in type 2 diabetes management: challenges and best practice solutions from real-world scenarios. J Clin Transl Endocrinol 2017;7:21–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Flurey CA, Hewlett S, Rodham K et al. “You obviously just have to put on a brave face”: a qualitative study of the experiences and coping styles of men with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2017;69:330–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]