Abstract

Background

Despite the fact that mental illnesses are highly prevalent, shortage of trained human resource, particularly psychiatrists, in the field is disproportionately low. This is especially challenging in developing countries. We report factors affecting medical students’ choice of psychiatry specialty as a future career.

Methods

A facility-based cross-sectional study design incorporating demographics, psychiatry specialty choice and a list of factors related to psychiatry was administered to fourth year medical students. Chi-squared test was used to identify factors associated with psychiatry choice. Multiple logistic regression analysis was done to identify the association between demographics and history of mental illness against psychiatry choice.

Results

One hundred and sixty-five medical students participated in the study. The majority, 139 (84.2%), of the students were male. From the medical students, 34 (21%) reported that they will choose to specialize in psychiatry for their future career. A chi-squared test result indicated that there were many factors associated with psychiatry choice. Family history of mental illness was found to be significantly associated with the future career choice of the psychiatry discipline (AOR=2.76; CI: 1.05–7.25).

Conclusion

Family history of mental illness seemed to be a significant factor in medical students’ psychiatry choice. Positive attitude to psychiatry, the manner in which psychiatry is taught, satisfaction related to practical and theoretical psychiatry education, having direct involvement in psychiatric patient care and the like were factors that affect psychiatry choice. Therefore, paying due attention to modifiable factors negatively affecting psychiatry choice may increase the selection of the field by medical students as a specialty.

Keywords: psychiatry specialty choice, factors, medical students

Background

Despite the 14% of global burden of diseases (GBDs)1, 450 million people suffer from mental neurological and substance use problems,2 and over 33% of healthy life years lost from disability (YLD) in low and middle income countries (LMICs)3 is accounted for by mental, neurological and substance use disorders. Many individuals with psychiatric disorders, particularly in LMICs, did not get treatment4 due to a significant shortage of psychiatrists5,6 which is accompanied by limited number of medical students choosing psychiatry as specialty.7,8 Specifically, in sub-Saharan African countries, there is less than one psychiatrist is for one million people.9 In Ethiopia, there are a limited number of medical doctors joining the psychiatry specialty, resulting in 0.02 of a psychiatrist for 100,000 people.10

One would expect that exposure to a psychiatry course and clinical rotation might increase the future career choice but medical students who completed a psychiatry clinical attachment had unfavorable/negative attitudes toward psychiatry as opposed to those medical students awaiting psychiatry clinical attachment.11 This is a bottleneck to increase the human resources in the field. The reasons for and against their attitude towards psychiatry has to be explored as it directly affects the career choice.

Researchin developed countries pointed out the reasons affecting the choice of psychiatry as a future specialty by medical students. Studies carried out in the UK and Indonesia reported that the intention of medical students to pursue psychiatry as their future career was predicted by factors including encouragement from consultants, having direct involvement in patient care, and seeing patients who responded well to treatment, female gender, and positive attitude toward psychiatry. But in a study done in Indonesia, gender did not predict psychiatry as a career choice.12–14 A study conducted among Israeli medical students reported that out of the whole study,only 14.9% of participants regarded psychiatry as their future career option.15 A similar study in Italy showed that medical students chose psychiatry as a future career because of experience with mental illness either personally or by a relative or close friend, efficacy of psychiatric treatments, the degree to which psychiatric practice is perceived to be evidence based, research opportunities, and curiosity about the topic of “madness”.16 However, the other medical students in Israel, Italy, UK, Europe and developed Asian countries rejected a career in psychiatry due to the perceived (low) possibility of using their medical training fully, psychiatrists did not pay enough attention to physiology, the perceived (low) efficacy of psychiatric treatments, the experience of psychological problems either personally or by a relative or close friend, low job satisfaction, financial unrewardability.15–17 Similar study done in Portugal revealed that factors such as low prestige of psychiatry (56.2%), negative pressure from peers (27.5%) and family (30.1%) significantly accounted for the medical student’s intention not to choose psychiatry as their future career.18

However, despite the significant level of shortage of psychiatrists and limited number of medical students joining the psychiatry specialty in LMICs, little is studied on the factors affecting medical students’ intention to choose the field as future specialty. Therefore, this research gap inspired the investigators to study the factors affecting the choice of psychiatry as a future specialty by fourth year medical students of Jimma University following their psychiatry clinical rotation.

Materials and methods

Study design

A facility-based cross-sectional study design was employed to examine the factors affecting the intention of fourth year medical students to choose psychiatry as their future specialty following their psychiatry clinical rotation.

Study setting and period

The study was conducted in Jimma University in October 1/2015. Jimma University is located in Jimma Town. The town is 352 km from Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. It is one of the oldest and most reputable universities and centers of excellence in medical education in the country.

Study participants

The study participants were fourth year medical students. These medical students took clinical psychiatry rotation for a duration of six weeks as part of their medical training program. During the six weeks of psychiatry rotation, medical students were attending classroom lectures, morning and ward round meeting sessions all in the same clinical site. In addition, they were involved in patient history taking from inpatient and outpatient departments and presented their clinical reports to senior psychiatrists. All students are thought to be exposed equally during the clinical rotation. Most of the patients admitted in the clinic with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, major depressive disorder with psychotic features or bipolar disorders. Those medical students who were retaking the psychiatry course due to delay or other reasons were excluded from the study. There were a total of 176 medical students during the clinical rotation.

Measurement

The study used a self-administered questionnaire that consisted of factors influencing medical student’s psychiatry career choice (which are developed after reviewing literature). At the end of their clinical attachment, medical students were asked a question; “will you choose psychiatry as your future specialty career?” to answer either Yes or No. Regardless of their answer to the specialty, a list of factors was presented and students were allowed to consider that particular factor influencing their psychiatry future career choice either positively or negatively using Yes/No or related words. To assess their attitude toward psychiatry, attitude towardpsychiatry 30 (ATP-30) scale was used. ATP-30 was developed in Canada by Burra et al19 and has a 5-point Likert type scale responses (1=strongly disagree, 2=disagree, 3=neutral (no opinion), 4=agree, and 5=strongly agree) for the 30 items measuring the medical student’s attitude to psychiatric patients, psychiatric illness, psychiatrists, psychiatry career choice, psychiatric treatment, psychiatric institutions and psychiatry teaching. This scale has been shown to have good psychometric properties among medical students.19 In Ethiopian context, ATP-30 was previously used and reported reliability with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.80 (11). ATP-30 generates a total score between 30 and 150 with a higher score indicating a positive attitude toward psychiatry.

Attitude

Refers to the fourth year medical student’s approach toward psychiatry and related others as measured by the scale of ATP-30. Scores above ATP-30 mean score indicated favorable or positive attitude toward psychiatry and vice versa.

Medical students

Refers to those fourth year undergraduate students of Jimma University who were studying the field of medicine in the academic year of 2015.

Psychiatry clinical rotation

Refers to the psychiatry course that fourth year medical students of Jimma University were expected to take for six weeks as part of their undergraduate medical training at Jimma University Teaching hospit, psychiatry clinic in the academic year of 2015.

Statistical analysis

The collected data were analyzed to give means, frequencies and percentages, chi-squared tests using statistical package for social sciences (SPSS version 20, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Bivariate and multivariable logistic regression was used to identify the variables accounted for medical student’s intention to choose psychiatry as future specialty. P-value of less than 0.05 was taken to consider statistical significance.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics and history of mental illness

One hundred and sixty-five medical students participated in the study with a response rate of 94.0%. The mean age of the students was 23±1.31 years with minimum and maximum age of 20 and 28 years respectively. The majority, 139 (84.2%) of the students were male. Regarding mental illness, 8 (4.8%) of the students reported personal history of mental illness whereas large numbers, 45 (27.7%) and 27 (16.4%), of students reported history of mental illness in their families and close friends respectively. The result indicated that a significant number 66 (40.0%) of medical students had reported negative attitude towardpsychiatry (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and history of mental illness among medical students, October 2015

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 139 | 84.2 |

| Female | 26 | 15.8 | |

| Age | ≤23 years | 121 | 73.3 |

| ≥24 years | 44 | 26.7 | |

| Personal history of mental illness | Yes | 8 | 4.8 |

| No | 157 | 95.2 | |

| Family history of mental illness | Yes | 27 | 16.4 |

| No | 138 | 83.6 | |

| History of mental illness in close friends | Yes | 45 | 27.7 |

| No | 120 | 72.3 | |

| Residence | Urban | 76 | 46.3 |

| Rural | 88 | 53.7 | |

| Attitude toward psychiatry (based on ATP-30) | Positive | 99 | 60.0 |

| Negative | 66 | 40.0 | |

Factors affecting medical students’ choice of psychiatry as their future career

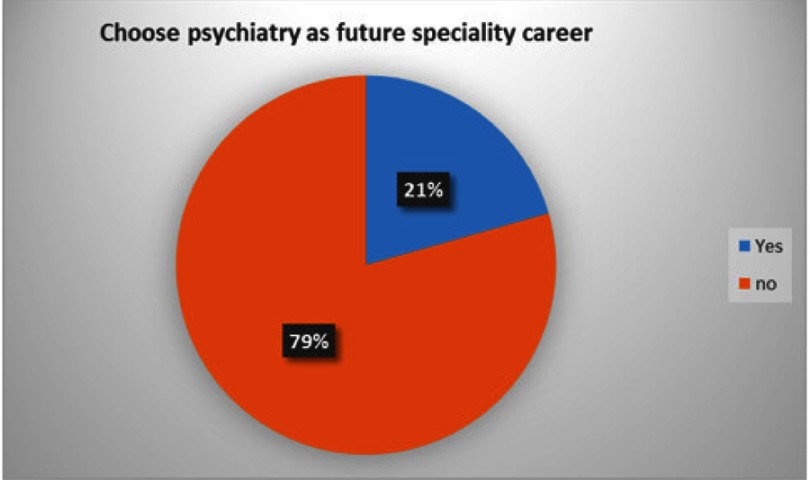

From all participating students, 34 (21%) of students reported that they will choose the specialty of psychiatry for their future career. Female medical students (26.9%), students who had positive attitude to psychiatry (29.3%), students with personal history (50%) and family history (44.4%) of mental illness, and students who reported history of a close friend with mental illness (35.6%) had shown psychiatry as a future career specialty than their counterparts (Figure 1 and Table 3).

Figure 1.

Medical students’ choice of psychiatry specialty as future career.

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of factors affecting medical students’ choice of psychiatry as future specialty career, October, 2015

| Variables | Psychiatry for future specialty | COR (95%CI) | AOR (95%CI) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes N (%) | No N (%) | |||||

| Sex | Male | 27 (19.4) | 112 (80.6) | 1.53 (0.58–4.00) | 0.98 (0.33–2.95) | 0.973 |

| Female | 7 (26.9) | 19 (73.1) | 1 | |||

| Age | ≤23 years | 21 (17.4) | 100 (82.6) | 1.99 (0.90–4.45) | 1.13 (0.46–2.78) | 0.789 |

| ≥24 years | 13 (29.5) | 31 (70.5) | 1 | |||

| Personal history of mental illness | Yes | 4 (50) | 4 (50) | 4.23 (1.00–17.90)* | 2.63 (0.56–12.30) | 0.218 |

| No | 30 (19.1) | 127 (80.9) | 1 | |||

| Family history of mental illness | Yes | 12 (44.4) | 15 (55.6) | 4.23 (1.74–10.22)* | 2.76 (1.05–7.25) | 0.039* |

| No | 22 (15.9) | 116 (84.1) | 1 | |||

| History of mental illness in close friends | Yes | 16 (35.6) | 29 (64.4) | 3.13 (1.42–6.88)* | 1.86 (0.76–4.54) | 0.170 |

| No | 18 (15.0) | 102 (85.0) | 1 | |||

| Residence | Urban | 14 (18.4) | 62 (81.6) | 1 | ||

| Rural | 20 (22.7) | 68 (77.3) | 1.30 (0.61–2.80) | 1.16 (0.49–2.74) | 0.731 | |

| Attitude toward psychiatry (based on ATP-30) | Positive | 29 (29.3) | 70 (70.7) | 5.05 (1.84–13.86)* | 2.61 (0.81–8.37) | 0.107 |

| Negative | 5 (7.6) | 61 (92.4) | 1 | |||

Note: Chi squared=4.6, df=7, Hosmer–Lemeshow test =0.7 (*P<0.05).

Looking in to other factors affecting their future career choice, around two thirds of medical students reported that psychiatric patients did not respond well to treatment and had received no encouragement from consultant psychiatrists, teachers and professionals of other disciplines regarding psychiatry. A similar number of students also reported that there is no opportunity and condition for further education in psychiatry. Whereas, three quarters of medical students reported that they had no exposure to materials related to psychiatry and had negative pressure from family and peers regarding future choice of psychiatry specialty.

The chi-squared test result showed that encouragement from consultant psychiatrists, teachers and professionals of other disciplines (P=0.004), having direct involvement in psychiatric patient care (P=0.0001), curiosity about the topic of “madness” (P=0.006), the degree to which patients are helped is impressive (P=0.005), exposure to materials related to psychiatry (P=0.043), feeling uncomfortable with psychiatric patients (P=0.0001), pressure from family, peers regarding future choice of specialty (P=0.040), satisfaction related to practical and theoretical psychiatry education (P=0.0001), the manner in which psychiatry is taught and presented (P=0.0001), newness/novelty of psychiatry (P=0.0001), hazards in the field (P=0.009) and financial advantages (P=0.009) were associated with choice of psychiatry specialty as a future career (Table 2).

Table 2.

Factors affecting medical students’ choice of psychiatry as future career specialty, October, 2015

| Variables (N=165) | Frequency | Percentage | X2 test P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychiatric patient responds well to treatment | Yes | 59 | 35.8 | 0.52 |

| No | 106 | 64.2 | ||

| Encouragement from consultant psychiatrists, teachers and profession of other discipline | Yes | 58 | 35.2 | 0.004* |

| No | 107 | 64.8 | ||

| Having direct involvement in psychiatric patient care | Yes | 91 | 55.2 | 0.0001** |

| No | 74 | 44.8 | ||

| Curiosity about the topic of “madness” | Yes | 59 | 35.8 | 0.006* |

| No | 106 | 64.2 | ||

| The degree to which patients are helped is impressive | Yes | 81 | 49.1 | 0.005* |

| No | 84 | 50.9 | ||

| Exposure to materials related to psychiatry | Yes | 41 | 24.8 | 0.043* |

| No | 124 | 75.2 | ||

| Opportunity and condition for further education | Yes | 57 | 34.5 | 0.085 |

| No | 108 | 65.5 | ||

| Feeling uncomfortable with psychiatric patients | Yes | 56 | 33.9 | 0.0001** |

| No | 109 | 66.1 | ||

| Pressure from family, peers regarding future choice of specialty | Positive | 42 | 25.5 | 0.040* |

| Negative | 123 | 74.5 | ||

| Satisfaction related to practical and theoretical psychiatry education | Satisfied | 51 | 30.9 | 0.0001** |

| Not satisfied | 114 | 69.1 | ||

| Observed recovery of psychiatric patients in relation to patients with other medical conditions | Yes | 74 | 44.8 | 0.771 |

| No | 91 | 55.2 | ||

| Previously, having close relationship with patients having mental illness/es | Yes | 38 | 23.0 | 0.321 |

| No | 127 | 77.0 | ||

| Negative comment from teachers and professionals of other discipline on psychiatry or mental illness | Yes | 31 | 18.8 | 0.763 |

| No | 134 | 81.2 | ||

| The manner in which psychiatry is taught and presented | Yes | 73 | 44.2 | 0.0001** |

| No | 92 | 55.8 | ||

| Newness/novelty of psychiatry | Yes | 55 | 33.3 | 0.0001** |

| No | 110 | 66.7 | ||

| Hazards in the field | Yes | 61 | 37.0 | 0.009* |

| No | 104 | 63.0 | ||

| Fear of stigma for working in psychiatry | Yes | 55 | 33.3 | 0.785 |

| No | 110 | 66.7 | ||

| Financial advantage | Rewarding | 25 | 15.8 | 0.009* |

| Unrewarding | 140 | 84.8 | ||

Note: P-value based on chi-squared test (*P<0.05, **P<0.001).

In the univariate analysis reporting personal history of mental illness (COR=4.23; CI: 1.00–17.90), family history of mental illness (COR=4.23; CI: 1.74–10.22), history of mental illness in close friends by medical students (COR=3.13; CI: 1.42–6.88) and a positive attitude toward psychiatry (COR=5.05; CI: 1.84–13.86) were significantly associated with future psychiatry specialty choice.

However, in the multivariate analysis reporting only family history of mental illness was found to be significantly associated with the future career choice of the psychiatry discipline. It was indicated that the chance of choosing psychiatry specialty career was about three times, (AOR=2.76; CI: 1.05–7.25), higher among medical students who reported presence of mental illness among their family members than students who did not report family history of mental illness (Table 3). Test of multicollinearity was done for variables and entered into final model and the VIF values indicated no multicollinearity.

Discussion

Based on the results of the current study, (21%; CI: 15–27%) of medical students reported that they will choose psychiatry as their future career specialty. Similar results were obtained from UK final year medical students where 17% were seriously considering psychiatry specialty.20 A slightly higher number 27.9% of medical students choosing psychiatry were reported from a Canadian study on psychiatry residents who actually decided to choose specialty during their undergraduate medical school.21 This result was less than a study from Singapore which reported that 44% of medical students showed intention to choose psychiatry specialty.22 This could be due to inclusion of medical students from yearI to year V in the later study and only fourth year medical students who actually were exposed to psychiatry courses in the current study. It will be encouraging to fill the shortage of psychiatrists if this number of students choose psychiatry as they plan. It was indicated that students who enter medical school planning to become psychiatrists are likely to do so, and the vast majority of students who choose psychiatry do so during medical school.23 At the same time, the current result could not be relied upon as there was a report that medical students' decision, particularly those seriously considering the field, has been found low at the final year of medical education.20 This might be due to medical students choice being affected by the educators approach during the course and clinical rotation in which its effect wanes with time after the training. This is particularly true in Ethiopia where only very few choose it as their specialty and join the residency in the field. Therefore, it could be crucial for mental health professionals and educators to encourage and engage medical practitioners in mental health related training and clinical works so that they can maintain the passion and choice of joining the field. This can greatly improve the specialist shortage faced by LMICs.

This study has also attempted to identify factors affecting medical students’ choice of psychiatry as future specialty. According to the chi-squared test result a number of factors were associated with psychiatry specialty choice. Encouragement from consultant psychiatrists, teachers and profession of other discipline, having direct involvement in psychiatric patient care (P=0.0001), curiosity about the topic of “madness” (P=0.006), the degree to which patients are helped is impressive (P=0.005), exposure to materials related to psychiatry (P=0.043), feeling uncomfortable with psychiatric patients (P=0.0001), pressure from family, peers regarding future choice of specialty (P=0.040), satisfaction related to practical and theoretical psychiatry education (P=0.0001), the manner in which psychiatry is taught and presented (P=0.0001), newness/novelty of psychiatry (P=0.0001), hazards in the field (P=0.009) and financial advantages (P=0.009) were associated with choice of psychiatry specialty as a future career. Similar previous study results also supported the current study findings that various factors were playing a role in medical students’ psychiatry specialty choice. Attitude toward psychiatry or mental health,22,24 opportunity for further education or training and salary were reported to be associated with psychiatry choice.25 A rating of “excellent” for the psychiatry clerkship and longer psychiatry rotation,23,26 the degree to which psychiatric practice is perceived to be evidence based, research opportunities, and curiosity about the topic of “madness”,16 external and internal stigma, quality of teaching of the subject as well as research exposure, effective college neuroscience courses and clinical experience and exposure during placements affects the psychiatry specialty choice.27,28 Hence, it is vital to look into and intervene infactors that affect the choice of psychiatry as future specialty career so that it will be possible to attract many medical practitioners to the discipline.

In this study having family history of mental illness was a stronger predictor of choice of psychiatry specialty. Medical students with family history of mental illness reported to choose psychiatry specialty 3 times more than students without family history of the illness. It was in agreement with previous study result that which showed that more students were reporting their interest in psychiatry with a family history of psychiatric illness as compared to without family history.27 However, in another study medical students experiencing mental illness personally through relatives or close friends were found to choose psychiatry specialty negatively.25 The probable difference could be in the later study population were first year psychiatry residents who already joined the field whereas in the current study they were fourth year medical students.

Limitation of the study

The results of this study haveto be interpreted taking into consideration some of the limitations. The current study did not provide other specialty choices than psychiatry and providing a single choice might increase the selection. The data collection was made immediately following the end of psychiatry rotation, which may affect their response and did not investigate whether the choice was maintained some time later. The questionnaire assessing factors was developed from literatures and was not validated to local context and also the specialty choice was assessed from students of one medical school from the same clinical attachment site where there is a relatively well-established psychiatry clinic in the general hospital setting in the country. The charisma of the educators delivering the course might also have played a role for a relatively high choice of psychiatry as future specialty in current study, but which could wane with time and students joining other specialty fields.

Conclusion

Family history of mental illness seemed to be a significant factor in medical students’ psychiatry choice. Positive attitude to psychiatry, the manner in which psychiatry is taught, satisfaction related to practical and theoretical psychiatry education, having direct involvement in psychiatric patient care and the like were factors that affect psychiatry choice. Therefore, paying due attention to modifiable factors negatively affecting psychiatry choice may increase the selection of the field by medical students as a specialty, therebyincreasing future psychiatry specialists for better mental health service in the country. Furthermore, follow-up studies, studies exploring reasons and factors affecting specialty choice and including medical students from many medical schools including general practitioners needed to be conducted.

Acknowledgment

The authors of this study should like to thank the study participants and Jimma University for facilitating the study.

Ethical approval

The study obtained ethical approval from the Research Ethical Review Board of the Institute of Health Sciences of Jimma University. In each questionnaire, an information sheet was attached that showed details of the study and the rights of the participants. Written informed consent was obtained from the study participants. Data were kept anonymous and confidential during all stages of the study.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Kessler RC, Aguilar-gaxiola S, Alonso J, et al. The global burden of mental disorders: an update from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) Surveys. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2009;18(1):23–33. doi: 10.1017/S1121189X00001421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Who. Investing in Mental Health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO. Reducing Risks, Promoting Healthy Life. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kohn R, Saxena S, Levav I, Saraceno B. The treatment gap in mental health care. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82(03):858–866. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel V. The future of psychiatry in low- and middle-income countries. Psychol Med. 2009;39:1759–1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO. Human Resources for Mental Health: Workforce Shortages in Low- and Middle-income Countries. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morris J, Lora A, McBain R, Saxena S. Global mental health resources and services: a WHO survey of 184 countries. Public Health Rev. 2012;34(2):1–19.26236074 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kakuma R, Minas H, Ginneken NV, et al. Human resources for mental health care: current situation and strategies for action. Lancet. 2011;378(5):1654–1663. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61093-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weintraub W, Plaut SM, Weintraub E. Recruitment into psychiatry: Increasing the pool of applicants. Can J Psychiatry. 1999;44(5):473–477. doi: 10.1177/070674379904400507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Who A. Mental Health System in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hailemariam H, Habtamu K, Alemayehu N, Eshetu G, Mathias S, Markos T. Attitude of medical students towards psychiatry: the case of Jimma University, Southwest Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2017;27(3):207–2014. doi: 10.4314/ejhs.v27i3.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McParland M, Noble L, Livingston G, McManus C. The effect of a psychiatric attachment on student’s attitudes to and intention to pursue psychiatry as career. Med Educ. 2003;37:447–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldacre MJ, Fazel S, Smith F, Lambert T. Choice and rejection of psychiatry as a career: surveys of UK medical graduates from 1974 to 2009. Br J Psych. 2013;202:228–234. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.111153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiguna T, Yap KS, Tan BW, Siew T, Danaway J. Factors related to choosing psychiatry as a future medical career among medical students at the faculty of medicine of the University of Indonesia. East Asian Arch Psychiatry. 2012;22:57–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gat I, Abramowitz MZ, Bentov-Gofrit D, Cohen R. Changes in the attitudes of Israeli students at the Hebrew University medical school toward residency in psychiatry: a cohort study. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2007;44(3):194–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galeazzi GM, Secchi C, Curci P. Current factors affecting the choice of psychiatry as a specialty: an Italian study. Acad Psychiatry. 2003;27(2):74–81. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.27.2.74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stuart H, Sartorius N, Liinamaa T, et al. Images of psychiatry and psychiatrists. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2015;131(1):21–28. doi: 10.1111/acps.12368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xavier M, Almeida JC. Impact of clerkship in the attitudes toward psychiatry among Portuguese medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10(56):1–8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-10-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burra P, Kalin R, Leichner P, et al. The ATP 30-a scale for measuring medical students’ attitudes to psychiatry. Med Educ. 1982;16(1):31–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halder N, Hadjidemetriou C, Pearson R, Farooq K, GJ Lydall, Malik A, et al. Student career choice in psychiatry: findings from 18 UK medical schools. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2013;25(4):438–444. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2013.824414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cameron P, Persad E. Recruitment into psychiatry: a study of the timing and process of choosing psychiatry as a career. Can J Psychiatry. 1984;29(8):676–680. doi: 10.1177/070674378402900808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seow LSE, Chua BY, Mahendran R, et al. Psychiatry as a career choice among medical students: a cross-sectional study examining school-related and non-school factors. BMJ Open. 2018;8(8):e022201. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldenberg MN, Williams DK, Spollen JJ. Stability of and factors related to medical student specialty choice of psychiatry. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(9):859–866. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17020159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sadr SS, Nayerifard R, Ardestani SMS, Namjoo M. Factors affecting the choice of psychiatry as a specialty in psychiatry residents in Iran. Iran J Psychiatry. 2016;11(3):185. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ozer U, Ceri V, Carpar E, Sancak B, Yildirim F. Factors affecting the choice of psychiatry as a specialty and satisfaction among Turkish psychiatry residents. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40(2):299–303. doi: 10.1007/s40596-015-0346-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aslam M, Taj T, Ali A, et al. Psychiatry as a career: a survey of factors affecting students’ interest in psychiatry as a career. Mcgill J Med. 2009;12(1):7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhugra D. Medical students choice of psychiatry–an international survey. Eur Psychiatry. 2016;33:S29. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2016.01.850 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kamour AH, Mannino DM, Hessler AB, Kedar S. Factors that impact medical student and house-staff career interest in brain related specialties. J Neurol Sci. 2016;369(15):312–317. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2016.08.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]