Abstract

Tuberculosis remains one of the deadliest infectious diseases of humanity. To better understand the evolutionary history of host-adaptation of tubercle bacilli (MTB), we sought for mycobacterial species that were more closely related to MTB than the previously used comparator species Mycobacterium marinum and Mycobacterium kansasii. Our phylogenomic approach revealed some recently sequenced opportunistic mycobacterial pathogens, Mycobacterium decipiens, Mycobacterium lacus, Mycobacterium riyadhense, and Mycobacterium shinjukuense, to constitute a common clade with MTB, hereafter called MTB-associated phylotype (MTBAP), from which MTB have emerged. Multivariate and clustering analyses of genomic functional content revealed that the MTBAP lineage forms a clearly distinct cluster of species that share common genomic characteristics, such as loss of core genes, shift in dN/dS ratios, and massive expansion of toxin–antitoxin systems. Consistently, analysis of predicted horizontal gene transfer regions suggests that putative functions acquired by MTBAP members were markedly associated with changes in microbial ecology, for example adaption to intracellular stress resistance. Our study thus considerably deepens our view on MTB evolutionary history, unveiling a decisive shift that promoted conversion to host-adaptation among ancestral founders of the MTBAP lineage long before Mycobacterium tuberculosis has adapted to the human host.

Keywords: tuberculosis, mycobacteria, host adaption, pathogenomic, pathogen evolution, evolutionary transition

Introduction

Obligate pathogens are specifically adapted to host cells, which represent their ecological niche. Most of these host-adapted organisms are descendants of free-living extracellular ancestors. Their emergence is associated with drastic adaptive changes to cope with new constraints, such as nutrient availability or host defenses (Toft and Andersson 2010). For many bacterial pathogens, comparative genomics identified genomic changes that correlate with this transition, including genome reduction, virulence factor acquisition, and loss of genetic diversity (Pallen and Wren 2007).

Presently, tuberculosis remains the deadliest human infectious disease (Dye and Williams 2010). However, up to now, the evolutionary steps leading to the tubercle bacilli (MTB), responsible for this disease, remain uncertain. MTB belong to the slow growing mycobacteria (SGM), a subgroup of the mycobacterial genus that contains most of the pathogenic mycobacterial species. MTB mainly consist of strains from the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTBC), a clonal group of closely related bacteria that cause TB in selected mammalian species, and a clade of Mycobacterium canettii strains, representing recombinogenic, rare tubercle bacilli, with unusual smooth colony morphology (Fabre et al. 2004; Boritsch et al. 2016a; Madacki et al. 2018). Mycobacteriumtuberculosis and M. canettii share more than 98% nucleotide identity (Supply et al. 2013), and thus can theoretically be classified into a single species (Riojas et al. 2018), whereby often the traditional, host-related names are continued to be used. Comparative genomic approaches, using Mycobacterium marinum or Mycobacterium kansasii as outgroups suggested that massive genomic changes led to MTB differentiation (Stinear et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2015), including marked genomic reduction, horizontal gene transfer (HGT), and toxin–antitoxin massive expansion. These studies revealed a wide evolutionary gap separating the genomic structures of MTB from those of related environmental mycobacteria, suggesting the existence of unknown intermediate evolutionary steps that may have paved the way to MTB host-adaptation (Veyrier et al. 2011; Wang and Behr 2014). Taking advantage of recently released mycobacterial genus sequence data (Tortoli et al. 2017), we investigated a distinct phylogenetic cluster of species associated with MTB, hereafter called MTB-associated phylotype (MTBAP). A dedicated comparative genomic analysis approach revealed that MTBAP members share most of the MTB attributes associated with host adaptation, suggesting ancestral transitional forms leading to host-adaptation conversion.

Our results allowed us to propose a novel phylogenetic scheme of MTB deep evolutionary roots, which is also linked to apparent changes in the ecology of MTB. They unveil a major ancestral evolutionary leap that shaped most genomic characteristics related to host-adaptation, inaugurating an extended co-evolution period, long before MTB speciation.

Materials and Methods

Research Strategy Overview

To evaluate the deeper phylogenetic and pathogenomic relationships between MTB and selected, recently genome-sequenced mycobacterial species, we used following approaches: At first, Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) analyses were performed on whole genome sequences from selected mycobacterial species, followed by the generation of a phylogenetic tree based on maximum likelihood similarities of widely distributed essential bacterial gene products, preselected by the bcgTree software. In addition, synonymous mutation rates on core genomes were calculated. In a second step, species-specific evolutionary dynamics were investigated by analyzing gene gains and gene losses as well as dN/dS ratios. The putative functional specificities of the investigated species were predicted by using multivariate analyses on whole proteomes, as well as determination of gene flux by HGT and identification of putative genomic islands. Based on the different results, an evolutionary scenario was proposed that integrates the putative contributions of a group of closely related mycobacterial species on the shaping of host-associated traits of MTB.

ANI and Phylogeny Analyses

We performed mutual ANI calculations on genome data from 10 defined SGM species, consisting of strains M. tuberculosis H37Rv, M. canettii STB-K, Mycobacteriumdecipiens TBL 1200985, Mycobacteriumshinjukuense CCUG 53584, Mycobacteriumlacus DSM 44577, Mycobacteriumriyadhense DSM 45176, M. kansasii ATCC 12478, M. marinum E11, Mycobacteriumszulgai DSM 44166, and Mycobacteriumgordonae DSM 44160 (table 1), which were selected based on reported findings from genus-wide mycobacterial sequence analyses (Fedrizzi et al. 2017; Tortoli et al. 2017). Pairwise genomic distances between genomes were calculated according to BLAST-based ANI scores (Goris et al. 2007), determined by using JspeciesWS (Richter et al. 2016).

Table 1.

Pairwise Genomic Distances of MTB and Closely Related SGM Species

| ANI [% Aligned] | Mtub | Mcan | Mdec | Mshi | Mlac | Mriy | Mkan | Mmar | Mszu | Mgor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mtub | — | 97.79 [90.62] | 85.18 [70.43] | 82.22 [67.21] | 81.46 [66.70] | 80.51 [67.74] | 79.63 [65.42] | 78.57 [64.75] | 79.28 [64.01] | 77.70 [62.28] |

| Mcan | 97.71 [88.79] | — | 85.15 [69.71] | 81.99 [65.98] | 81.43 [66.31] | 80.63 [67.40] | 79.69 [64.68] | 78.57 [63.34] | 79.28 [63.35] | 77.57 [60.75] |

| Mdec | 84.34 [62.60] | 84.39 [63.23] | — | 80.91 [58.13] | 81.30 [63.57] | 80.42 [67.40] | 79.45 [66.00] | 78.57 [66.67] | 79.32 [65.69] | 77.55 [62.72] |

| Mshi | 82.21 [67.90] | 82.08 [67.84] | 81.48 [65.71] | — | 82.37 [70.53] | 81.43 [69.12] | 80.68 [67.36] | 79.37 [65.38] | 80.35 [66.50] | 78.79 [64.74] |

| Mlac | 81.15 [62.01] | 81.25 [62.28] | 81.63 [65.53] | 82.12 [65.19] | — | 82.04 [70.44] | 80.46 [67.77] | 79.06 [65.30] | 80.49 [67.68] | 78.59 [64.42] |

| Mriy | 79.54 [52.03] | 79.59 [52.38] | 80.17 [57.26] | 80.49 [52.49] | 81.14 [58.74] | — | 79.13 [58.92] | 77.90 [56.69] | 80.93 [64.48] | 77.56 [58.40] |

| Mkan | 78.62 [47.78] | 78.63 [48.36] | 79.07 [54.05] | 79.65 [49.10] | 79.70 [53.48] | 79.13 [56.38] | — | 79.07 [59.76] | 78.92 [58.72] | 77.54 [57.73] |

| Mmar | 77.31 [49.41] | 77.35 [49.69] | 77.98 [57.08] | 78.31 [48.95] | 78.04 [53.76] | 77.59 [56.56] | 78.82 [62.67] | — | 77.37 [59.18] | 76.53 [58.75] |

| Mszu | 77.82 [47.14] | 77.84 [47.64] | 78.53 [55.11] | 78.99 [48.53] | 79.25 [54.46] | 80.39 [62.95] | 78.35 [60.67] | 77.24 [57.97] | — | 77.79 [61.73] |

| Mgor | 76.20 [40.69] | 76.23 [40.77] | 76.76 [45.98] | 77.29 [41.74] | 77.22 [45.49] | 76.96 [50.24] | 76.99 [51.96] | 76.16 [50.79] | 77.60 [54.55] | — |

Notes.—ANI values were calculated from genome to genome BLAST-based comparison. Within brackets: aligned genome percentage.

Bold: higher ANI values with MTBC, as compared with previously studied reference outgroups M. kansasii and M. marinum.

Mtub, M. tuberculosis H37Rv; Mcan, M. canettii STBK; Mdec, M. decipiens; Mlac, M. lacus; Mriy, M. riyadhense; Mkan, M. kansasii; Mmar, M. marinum E11; Mszu, M. szulgai; Mgor, M. gordonae.

For phylogenetic analyses, a larger, representative study data set was established, to obtain robust bootstrap values. Twenty-eight mycobacterial species were selected for the analysis (supplementary table 1, Supplementary Material online), including 25 SGM species, Mycobacterium terrae, belonging to the intermediate M.terrae complex group, as well as Mycobacterium smegmatis and Mycobacterium abscessus, representing rapidly growing mycobacteria. The latter three species were used as outgroup. Putative coding sequences and associated protein sequences were identified, and annotated from contigs and whole genome data, using the Microbial Genome Annotation and Analysis platform “MicroScope” (Vallenet et al. 2017).

For the calculations, 107 essential bacterial genes, which were defined by the bcgTree (bacterial core genome Tree) software (Ankenbrand and Keller 2016) as being present as single copy genes in the majority of bacterial genomes, were retrieved for each of the 28 species. Sequences were concatenated, aligned using clustal Omega, and well-conserved regions were selected using Gblocks. The phangorn R package (Schliep 2011) was then used to generate a phylogenetic tree based on maximum likelihood (ML) estimates (via the pml algorithm), using a JTT_DCMut+I+G best substitution model.

Core/Variable Genome and dN/dS Analyses

Gene families were determined using the MICFAM (MicroScope gene families) tool, computed with the SiLiX software (Miele et al. 2011) by using a 50% amino acid identity threshold and 80% alignment coverage. Families with exactly one gene per species were selected for core-genome orthologs. For dN/dS ratio calculations, core-genome amino-acid sequences were retrieved, and aligned using clustalW2 (Larkin et al. 2007). Nucleic sequences were then aligned according to the deduced codons from amino-acid alignment using the pal2nal software (Suyama et al. 2006), and gaps were removed. dN/dS calculation was then performed using the PAML program (Yang 1997). To remove saturation effects, genes having dS <0.01, dS >2, and dN >2 were removed from the analysis. For each species, dN/dS distribution values relative to the M. gordonae outgroup were generated and visualized using R boxplot functions (R-Core-Team 2014), and a Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test was used to identify median values significantly lower than M. tuberculosis median values. *P value < 0.05. **P value < 0.001.

Multivariate Analysis of Protein Family Domains, M. tuberculosis Ortholog and Genomic Island Analyses

PFAM is a comprehensive collection of protein domains and families (Finn et al. 2008). For our analysis, PFAM domains associated with translated sequences of all investigated mycobacterial species were retrieved (e value <0.0001) using MicroScope (Vallenet et al. 2017). Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Between Class Analysis (BCA) were performed with centered and scaled data using the ade4 package in R (Thioulouse et al. 1997). Moreover, M. tuberculosis orthologs and synteny regions were identified using BLAST (Altschul et al. 1990) and MicroScope gene Phyloprofile functions, including the Bidirectional Best-Hit (BBH) method (50% identity, 80% query cover). A literature review was also performed on this data set to retain a subset of genes and gene products that were experimentally reported to be involved in animal infection or intracellular mycobacterial survival. For the identification of putative HGT regions, the Regions of Genomic Plasticity (RGP) functions of the MicroScope platform were used, by taking M. kansasii as the outgroup species (50% identity, 80% query cover). Finally, contigs associated with putative genomic islands were retrieved and alignment was performed using the MAUVE software (Darling et al. 2004). Homologous regions were drawn using genoPlotR package in R (Guy et al. 2010).

Results

MTB Phylogeny Revised

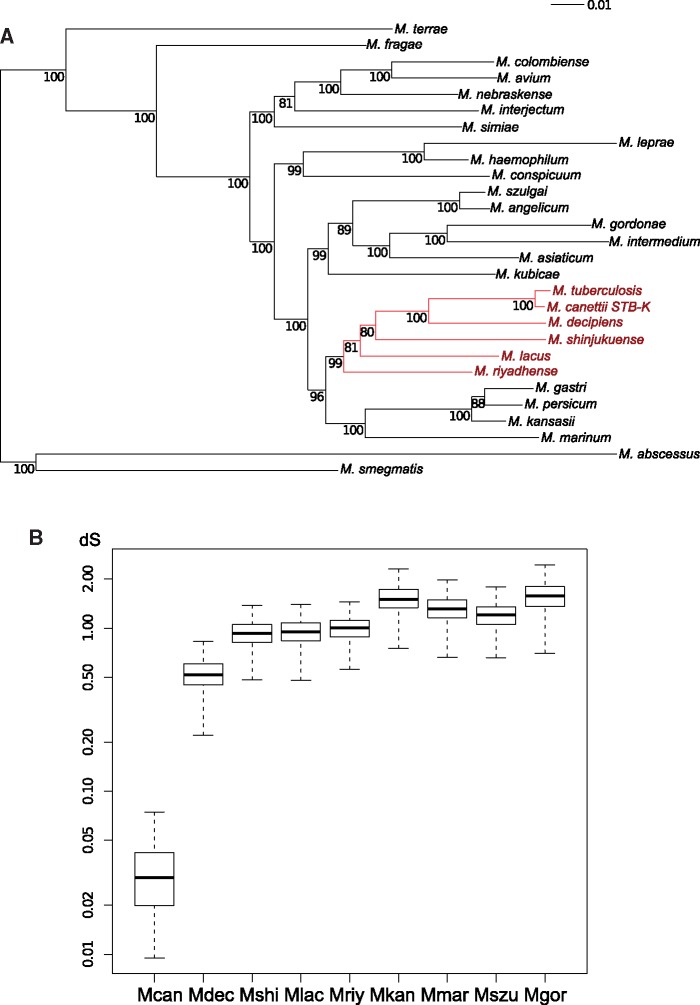

Previous comparative genomic studies on MTB used M. marinum or M. kansasii as closest known outgroups (Stinear et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2015). However, recent 16S rDNA analyses and genomic ANI clustering analyses suggested that certain other mycobacterial species might be closer related to MTB at the genomic level than these two most commonly used comparators (Fedrizzi et al. 2017; Tortoli et al. 2017). To get deeper insights into this matter, we performed ANI calculations on a set of 10 SGM species, which were selected according to previous genus-wide mycobacterial sequence data (Fedrizzi et al. 2017; Tortoli et al. 2017). These analyses revealed that highest ANI values and highest lengths of shared aligned genomic regions were found between MTB and four species (namely M. decipiens, M. shinjukuense, M. lacus, and M. riyadhense). For further phylogenetic analyses, an enlarged set of 28 mycobacterial species (supplementary table 1, Supplementary Material online) was chosen, from each of which the amino acid sequences of 107 broadly conserved, orthologous proteins were selected and retrieved using the bcgTree software (Ankenbrand and Keller 2016). The phylogenetic tree obtained from analyses of these data, using ML estimations generated very robust bootstrap values (fig. 1A) and provides strong evidence that these four aforementioned species are more closely related to MTB than M. kansasii and M. marinum (fig. 1A). Together with MTB, they represent a novel phylogenetic group that is descending from a common ancestor and will be referred to hereafter as the MTBAP lineage. Using core-genome data from MTBAP species and four closely related outgroup-species, namely M. kansasii, M. marinum, M. szulgai, and M. gordonae, referred here after as MGS–MKM outgroup, synonymous mutations were extracted to get an estimate of divergence time between these species and MTB (fig. 1B). From these data, the most recent common ancestor (MRCA) of MTB and other species from the MTBAP lineage was found to be more recent than the MRCA of MTB and the MGS–MKM outgroup species. These data also suggest that MTBAP species are phylogenetically related descendants originating from a common progenitor, with a divergence time estimated to be 15–30 times longer than the one considered for M. tuberculosis and M. canettii within MTB.

Fig. 1.

—Phylogenetic organization of MTB and closely related SGM species. (A) SGM phylogenetic tree. For tree construction, concatenated conserved protein sequences from 107 universally conserved bacterial genes, as defined by the bcgTree software, were extracted from 28 mycobacterial species. For data analysis, a similarity matrix was calculated using the JTT_DCmut+I+G model. The phylogentic tree was constructed using ML estimations. Bootstrap values were calculated from 500 replicates. Red branches: members of the MTBAP lineage. (B) Genetic distance of MTBAP lineage and MGS–MKM outgroup members relative to M. tuberculosis H37Rv. dS distribution of 923 core-genome genes compared with those of M. tuberculosis H37Rv. Synonymous mutation rates (dS) for each gene were determined using the PAML algorithm. y-Axis: logarithmic scale. Mcan, M. canettii STB-K; Mdec, M. decipiens; Mshi, M. shinjukuense; Mlac, M. lacus; Mriy, M. riyadhense; Mkan, M. kansasii; Mmar, M. marinum E11; Mszu, M. szulgai; Mgor, M. gordonae. Bold bar: median. Box edges: 25th and 75th percentiles. Whiskers: extreme values.

Shared Genomic Reduction Profiles

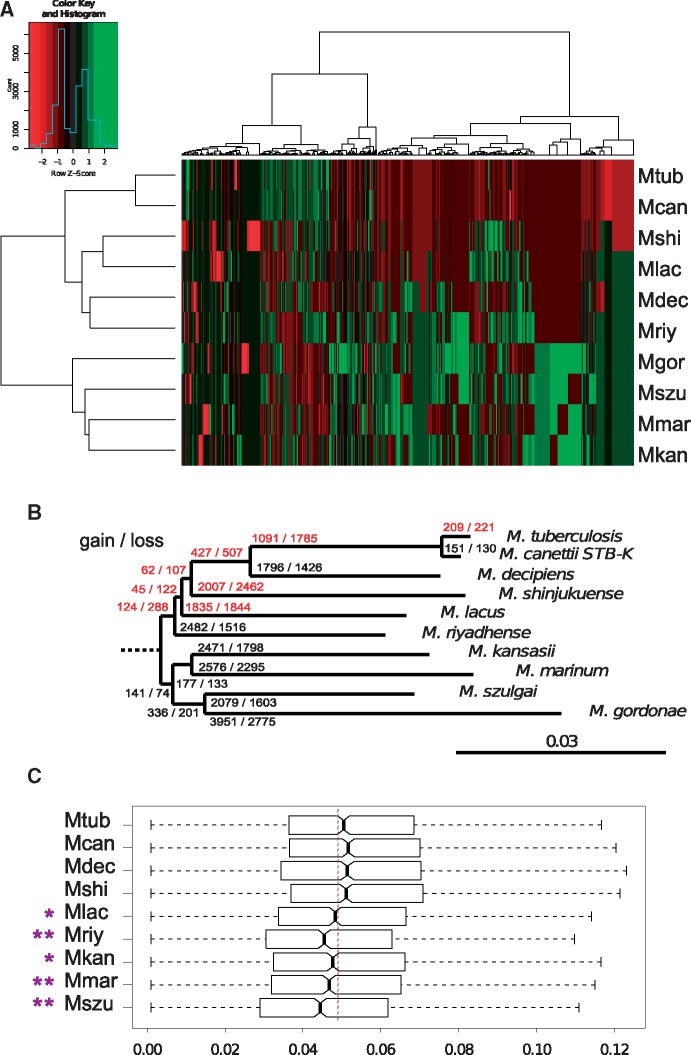

Because MTB are well-known to have undergone genome size reduction (<4.5 Mb) compared with M. kansasii (6.4 Mb) and M. marinum (6.6 Mb) outgroups, we assessed if other species from the MTBAP lineage displayed similar genomic reduction patterns. A preliminary study using EGGNOG gene functional classification from MicroScope (Vallenet et al. 2017) suggests that besides MTB, M. decipiens, M. shinjukuense, and M. lacus harbor significantly less genes in many functional categories (excluding basic, essential cellular functions), compared with other mycobacterial species (table 2), whereas M. riyadhense exhibits a less significant, intermediate pattern that is also associated with a relatively large genome size of 6.3 Mb (supplementary table 1, Supplementary Material online). To evaluate this trend in more detail, we used core-genome data to identify presence or absence of MICFAM gene families in each genome of the MTBAP and MGS–MKM lineages, which were then categorized by large-scale hierarchical clustering. Distance-tree analysis of species based on MICFAM gene family content shows that the MTBAP lineage represents a specific cluster, clearly distinct from the MGS–MKM outgroup, a finding that is further emphasized by the large number of gene families present in the MGS–MKM outgroup that are under-represented in all species of the MTBAP lineage (fig. 2A). A model of gene gain and gene loss (fig. 2B) confirms that loss of certain genes and gene families occurred within the MTBAP lineage. Most of the gene loss occurred within the branches leading to each species. In addition, some gene loss signatures are also shared between different lineages, which suggest that some of these genetic events might have been initiated at deep branching nodes at the base of the MTBAP lineage.

Table 2.

EGGNOG Functional Category Counts of Annotated Genes in Genomes of MTB and Closely Related Mycobacterial Species

| Function | Mtub | Mcan | Mdec | Mshi | Mlac | Mriy | Mkan | Mmar | Mszu | Mgor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy production and conversion | 212a | 214a | 293a | 230a | 282a | 322b | 347 | 322 | 366 | 379 |

| Cell cycle control, cell division, chromosome partitioning | 45 | 45 | 35 b | 44 | 41 | 49 | 38 | 32 | 42 | 57 |

| Amino acid transport and metabolism | 197a | 196a | 243 | 187a | 210a | 224b | 236 | 265 | 242 | 242 |

| Nucleotide transport and metabolism | 74b | 77 | 77 | 72b | 80 | 82 | 80 | 79 | 74 | 75 |

| Carbohydrate transport and metabolism | 147a | 141a | 175b | 166a | 170a | 197 | 202 | 193 | 232 | 240 |

| Coenzyme transport and metabolism | 136a | 140a | 148a | 115a | 147a | 173 | 158 | 162 | 171 | 157 |

| Lipid transport and metabolism | 213a | 210a | 273b | 216a | 265b | 289b | 311 | 318 | 313 | 386 |

| Translation, ribosomal structure, and biogenesis | 149 | 147 | 150 | 139b | 140b | 150 | 141 | 154 | 146 | 151 |

| Transcription | 227a | 235a | 281b | 221a | 273b | 356b | 306 | 325 | 356 | 429 |

| Replication, recombination, and repair | 233 | 257 | 176 | 176 | 188 | 262 | 248 | 192 | 152 | 328 |

| Cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis | 124a | 124a | 152 | 127a | 123a | 152 | 168 | 149 | 152 | 175 |

| Cell motility | 35a | 37a | 36a | 40b | 43b | 45 | 47 | 42 | 52 | 50 |

| Post-translational modification, protein turnover, chaperones | 103a | 108a | 106a | 115b | 115b | 126b | 142 | 136 | 132 | 167 |

| Inorganic ion transport and metabolism | 138a | 139a | 164a | 139a | 151a | 170a | 197 | 202 | 204 | 235 |

| Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport, and catabolism | 155a | 150a | 292 | 145a | 217a | 273b | 263 | 303 | 351 | 342 |

| Signal transduction mechanisms | 110b | 105a | 131b | 109a | 111b | 147b | 182 | 146 | 186 | 240 |

| Intracellular trafficking, secretion, and vesicular transport | 22 | 21 | 22 | 22 | 24 | 28 | 22 | 20 | 23 | 28 |

| Defense mechanisms | 59 | 59 | 62 | 61 | 64 | 67 | 77 | 59 | 62 | 87 |

Note.—Number of genes in each EGGNOG category.

Values below two standard deviation quantities as compared with the MGS–MKM outgroup.

Values below one standard deviation quantity, as compared with the MGS–MKM outgroup.

Mtub, M. tuberculosis H37Rv; Mcan, M. canettii STB-K; Mdec, M. decipiens; Mlac, M. lacus; Mriy, M. riyadhense; Mkan, M. kansasii; Mmar, M. marinum E11; Mszu, M. szulgai; Mgor, M. gordonae.

Fig. 2.

—Genomic evolution in MTBAP lineage. (A) Color coded table representing a heatmap for which the rows and columns were sorted by hierarchical clustering approaches. The row tree shows the clustering of MICFAM protein families based on species profile similarity calculated by the Ward agglomerative hierarchical clustering algorithm. The column tree represents the clustering of species based on MICFAM profile. Red: under-represented gene families. Green: over-represented gene families. Color-key for Row Z-scores is shown together with a histogram indicating the number of MICFAM protein families associated with each of the Z-scores. (B) Estimated gene gain and loss in the MTBAP lineage and the MGS–MKM outgroup. Variable genome parts of the MTBAP lineage and the MGS–MKM outgroup were computed using the MICFAM tool with a 50% amino-acid identity threshold and 80% alignment coverage. A table representing presence or absence of gene families for each species was then analyzed by Gain Loss Mapping Engine. Red: branches showing more gene loss than gene gain. (C) dN/dS distribution of core-genome orthologs as compared with the M. gordonae outgroup. Bold bars indicate the median dN/dS values for each species. Notch estimates correspond to 95% confidence intervals for median values. Box edges represent 25th and 75th percentiles. Whiskers represent estimated extreme values. Mcan, M. canettii STB-K; Mdec, M. decipiens; Mshi, M. shinjukuense; Mlac, M. lacus; Mriy, M. riyadhense; Mkan, M. kansasii; Mmar, M. marinum E11; Mszu, M. szulgai; Mgor, M. gordonae.

dN/dS Ratios Suggest Common Genome Evolution Dynamics within the MTBAP

To characterize the genome evolution dynamics of the different species, non-synonymous/synonymous mutation rates (dN/dS) were compared for the core genomes of the MTBAP and MGS–MKM group. As shown in figure 2C, by using the commonly found environmental M. gordonae as comparator reference species, we observed dN/dS ratios that were significantly higher for M. tuberculosis than for M. szulgai, M. marinum, and M. kansasii, the latter considered as environmental mycobacteria. Of note, high dN/dS ratios were also obtained for M. canettii, M. decipiens, and M. shinjukuense, whereas M. lacus showed intermediate values.

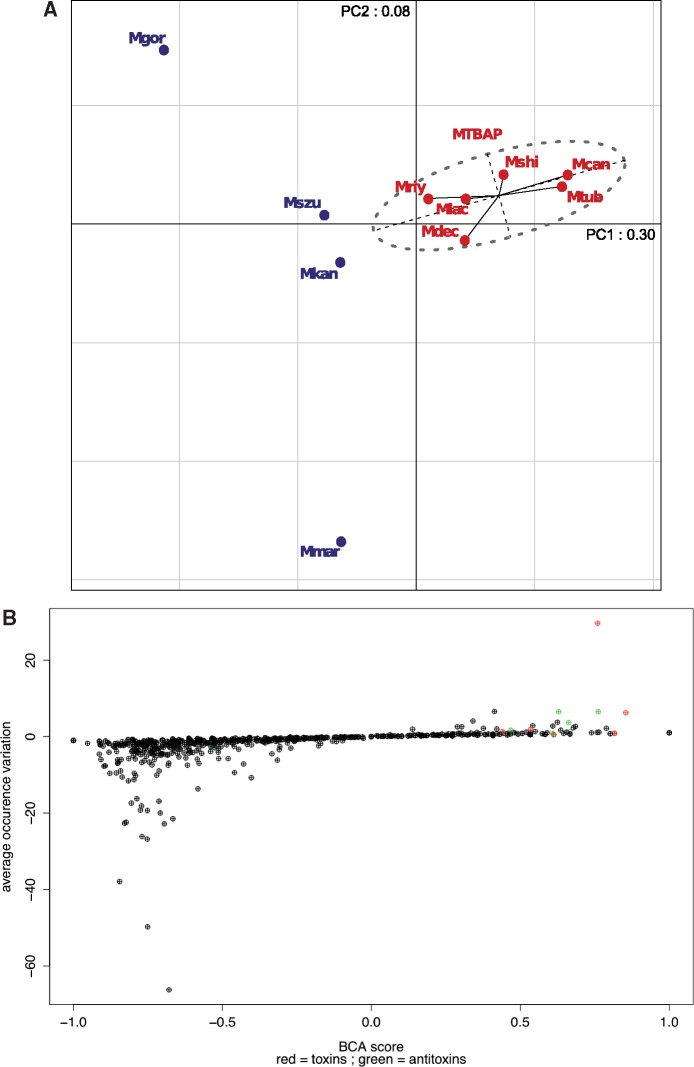

Functional Profile Analysis Reveals Similar Protein Family Clustering

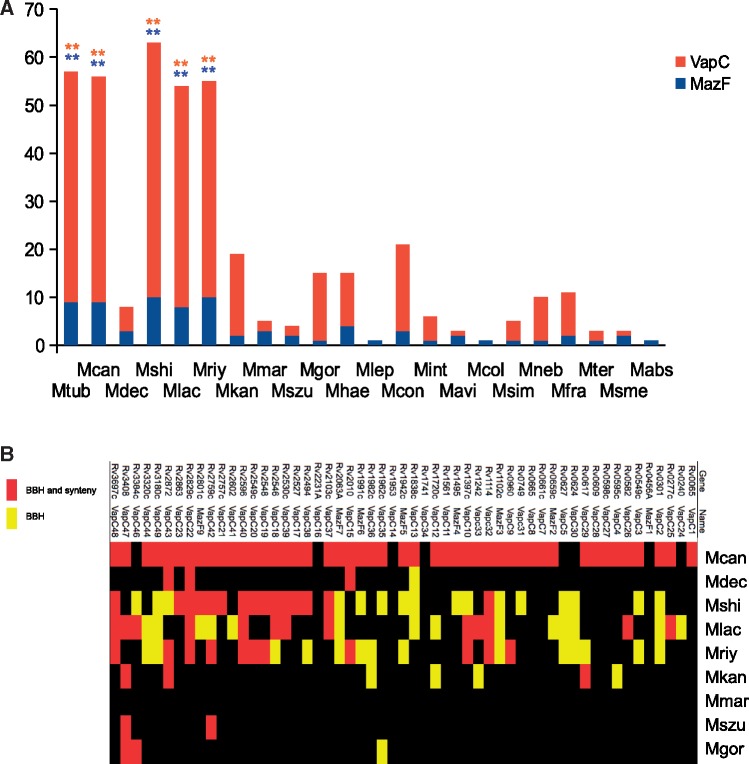

To explore if members of the MTBAP lineage were characterized by a specific protein content in terms of selected functional features, we retrieved the repertoire of PFAM protein family domains (Finn et al. 2006) associated specifically with each of the genomes of the MTBAP and MGS–MKM lineages. Multivariate analysis of these data, performed by PCA, showed that in agreement with aforementioned MICFAM clustering analyses, the MTBAP lineage constitutes a specific cluster (fig. 3A). The first projection axe (PC1) explains 30% of the variance, and allows to clearly distinguish the MTBAP lineage from the species of the MGS–MKM outgroup (fig. 3A). A striking consistency between data derived from MICFAM and PFAM domain analyses emphasize that genome contents of the MTBAP lineage members are substantially different from those of the MGS–MKM outgroup. In addition, BCA results showed that many PFAM domains were under-represented in the MTBAP lineage (negative BCA scores), apparently due to genomic reduction (fig. 3B). However, we also noticed some positive BCA scores, indicating a particular over-representation of selected PFAM domains in MTBAP members, arguing that this lineage is not only defined by gene loss, but also by acquisition of specific functional features. Careful study of these PFAM domains over-represented in the MTBAP lineage revealed that many of them corresponded to toxin–antitoxin domains (red and green dots, respectively, fig. 3B). Among these toxin–antitoxin domains, VapBC and MazEF type II systems appeared to be the most abundant in the MTBAP lineage (highest scores in y axis of fig. 3B). Specific counts of the genes coding for VapC or MazF toxins (containing respectively PIN and PemK domains) confirmed that these families were significantly over-represented in M. shinjukuense, M. lacus, and M.riyadhense together with MTB members M. canettii and M. tuberculosis (fig. 4A). It is clear from this analysis that certain mycobacterial species may harbor a greater repertoire of toxin–antitoxin systems, which were previously only reported for MTB (Ramage et al. 2009; Wang et al. 2015). Our results show now that with some exceptions found for M. decipiens, the MTBPA lineage members share an unexpectedly high number of VapBC and MazEF type II toxin–antitoxin systems. The high diversification of these toxin–antitoxin systems may be explained either by late genomic events that occurred independently in each of the species of the lineage, or by early genomic events that had occurred in a common ancestor of the lineage, followed by subsequent diversification. For the purpose of determining which of the two hypotheses was more likely, BLAST and BBH-based synteny analyses of VapC and MazF sequences of M. tuberculosis were undertaken in a variety of species. This approach revealed that among the 55 studied toxins, more than a third (35%) may be considered as orthologous proteins (BBH + synteny) that are shared among selected species of the MTBAP lineage, without showing orthologs in the MGS–MKM outgroup (fig. 4B), arguing for an early acquisition of a substantial portion of toxin–antitoxin systems in species of the MTBAP lineage and subsequent diversification.

Fig. 3.

—Multivariate and clustering analyses of PFAM domain contributions to the MTBAP lineage. (A) PCA of species from the MTBAP lineage and the MGS–MKM outgroup, based on occurrence of PFAM domains in each genome (only PFAM domains present in more than two species were conserved). Ellipse: 95% confidence value ellipse of MTBAP lineage members. (B) PFAM domain contribution to MTBAP lineage. x-Axis: PFAM domain scores determined by BCA (MTBAP lineage vs. MGS–MKM outgroup). y-Axis: PFAM domain differences in average occurrence for each class (MTBAP lineage vs. MGS–MKM outgroup). Red: toxin-associated domains. Green: antitoxin-associated domains.

Fig. 4.

—Toxin–antitoxin content of mycobacterial species in the MTBAP lineage and other SGM. (A) Number of putative toxin genes bearing PIN and MazF domain in SGM. Toxins from toxin–antitoxin systems were identified from whole proteome data sets, using HMMER (PF02452.16—PemK_toxin; PF01850.20 PIN domain) with a 0.01 threshold e value. Orange: VapC. Blue MazF. **: Values above two standard deviation levels from SGM (outside MTBAP lineage and MGS–MKM outgroup) average. (B) Putative orthologs of M. tuberculosis VapC and MazF toxins. Yellow: BBH 50% translated sequence identity, BBH 80% query cover. Red: BBH and synteny. Mcan, M. canettii STB-K; Mdec, M. decipiens; Mshi, M. shinjukuense; Mlac, M. lacus; Mriy, M. riyadhense; Mkan, M. kansasii; Mmar, M. marinum E11; Mszu, M. szulgai; Mgor, M. gordonae.

HGT and Acquisition of Rare Virulence and Cellular Stress Factors

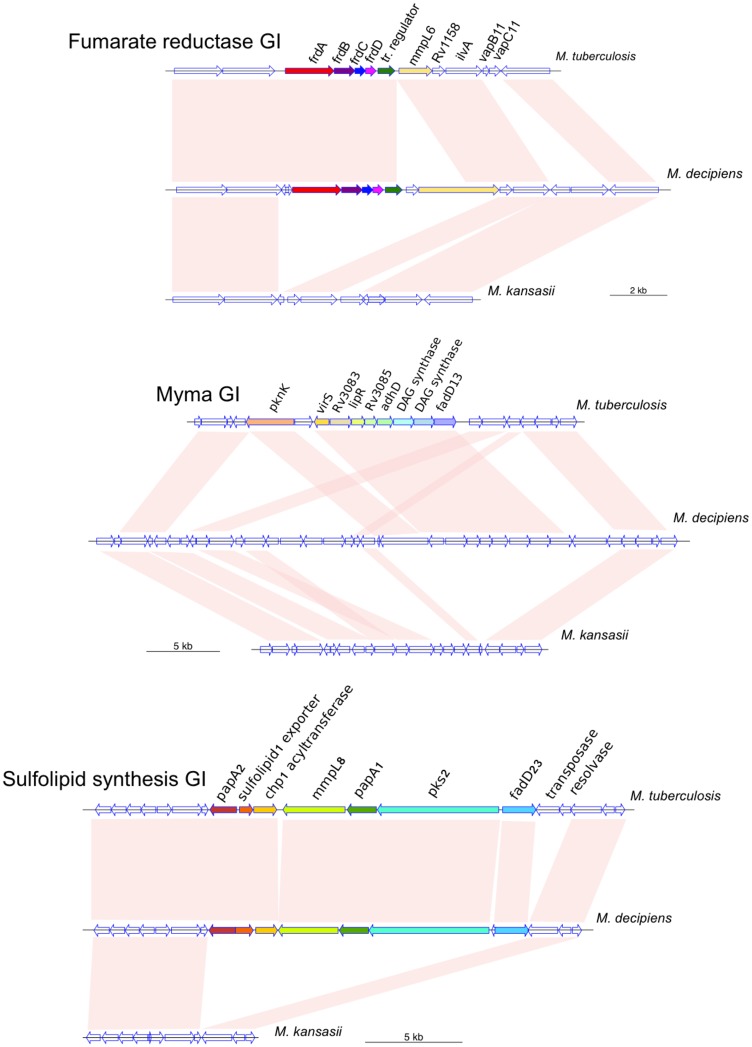

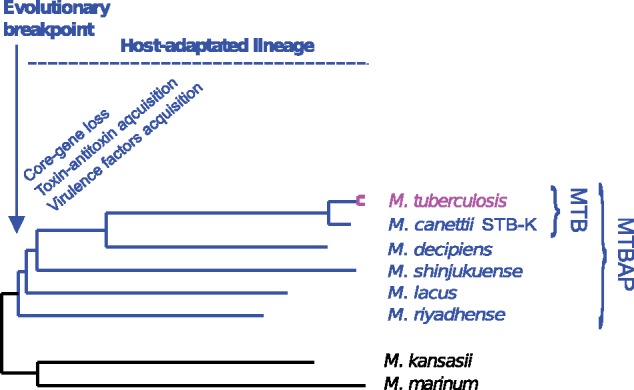

As toxin–antitoxin systems are often found within genomic islands acquired by HGT (Ramage et al. 2009) and may play important roles in shaping MTB gene content (Becq et al. 2007; Supply et al. 2013; Levillain et al. 2017), we performed a genome-wide screen to search for M. tuberculosis genes that likely were acquired in a common progenitor during the evolution of the MTBAP lineage before MTB speciation (i.e., after divergence from the MGS–MKM outgroup, but before branching of M. canettii and M. tuberculosis lineages). Such genes were determined by BBH-analysis to find M. tuberculosis/M. canettii genes with putative orthologs in other species from the MTBAP lineage that had no ortholog in the genomes of any of the other SGM species used in our study (supplementary table 1, Supplementary Material online). Our screen identified 169 genes of M. tuberculosis that were putatively acquired during the evolution of the MTBAP lineage before MTB speciation. These genes were present in 32 of the 46 identified M. tuberculosis RGP (supplementary table 2, Supplementary Material online), suggesting that many these genes, previously considered as M. tuberculosis-specific genomic traits, were acquired by HGT by a common ancestor in the MTBAP lineage before MTB speciation. We then asked if among these genes, some might play a role in pathogenicity. A literature review performed on these 169 genes, allowed us to identify 35 of them that were reported to be involved in survival or growth of MTB during infection of mononuclear phagocytic cells or in animal models (table 3), representing 21% of the initial gene pool, and 33% of the above-identified RGP. Among these genes, some were encoding regulation systems, comprising transcriptional regulation factors such as MosR, VirS, or Rv1359 adenyl cyclase, as well as several toxin–antitoxin systems (VapC24, VapBC19, VapBC20, VapC44). Strikingly, more than a third of these likely virulence-associated genes encode proteins involved in lipid metabolism and/or lipid transport (mosR, mce2B, Rv0895, Rv1288, Rv2954c, Rv2955c, virS, Rv3087, Rv3376, Rv3377c, lipF, fadD23). Many of them are predicted to be involved in biochemical processes linked to the mycomembrane of MTB, being implicated in mycolic acid composition (virS, Rv3087) (Singh et al. 2005), phenolic glycolipid glycosylation (Rv2954c, Rv2955c) (Simeone et al. 2013), and sulfolipid synthesis and accumulation (mce2B, fadD23) (Lynett and Stokes 2007; Marjanovic et al. 2011). Many genes were reported as induced under phagosome-associated stress, such as acidic pH (virS, lipF), and nutrient starvation (Rv0064, mosR, Rv1359, frdA, Rv2275, Rv3087, vapC44) as well as under specific conditions within the phagosome, the granuloma or the lungs (Rv0064, vapC24, frdA, vapC19, vapB19, vapB20, virS, PE_PGRS50) (Betts et al. 2002; Rachman et al. 2006; Watanabe et al. 2011; Mendum et al. 2015; Hudock et al. 2017). Moreover, genes encoding diterpene synthase (Rv3377c), implicated in production of diterpene nucleoside 1-TbAd involved in phagosome maturation arrest, or cyclopeptide synthase (Rv2275), producing mycocyclosin involved in intra-macrophage survival, are shared by selected species of the MTBAP lineage. Finally, we found that some of these potential virulence factors were encoded on obvious genomic islands (fig. 5), for example the fumarate reductase GI (Rv1552-1555), Myma GI (Rv3082c-3087), or sulfolipid synthesis GI (Rv3820c-3826). As summarized in figure 6, our results suggest that many genetic and genomic factors, formerly thought to correspond to MTB-specific virulence factors, are also present in certain other MTBAP species, and were probably acquired long time before MTB speciation, supporting an evolutionary scenario in which tuberculosis-causing mycobacteria emerged from an ancient family of mycobacteria that had “learned” to cope with intracellular stress conditions, likely through long-lasting interaction with yet unknown eukaryotic host organisms.

Table 3.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis Virulence Genes Probably Acquired before MTB Speciation, and within MTBAP Lineage Evolution

| Label | Gene | Product | Function | Phenotype | Intracellular Survival | Animal Infection Model | Mcan | Mdec | Mshi | Mlac | Mriy | SGM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rv0064 | — | Membrane protein | — | — | DC (Mendum et al. 2015) | — | ++ | ++ | − | − | + | − |

| Rv0071 | — | — | — | Deleted in L2/Beijing lineage M. tuberculosis strains (RD105) | M (Stewart et al. 2005) | — | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Rv0240 | vapC24 | Toxin–antitoxin | Regulation | Induced under lysosomal stress conditions (Lin et al. 2016) | — | Macaque (Dutta et al. 2010) | − | − | − | + | − | − |

| Rv0348 | mosR | Transcriptional regulator | Regulation | Hypoxia responsive regulator (Abomoelak et al. 2009) | — | Mouse (Abomoelak et al. 2009) | − | − | ++ | − | − | − |

| Rv0590 | mce2B | Transporter | Transport (lipids) | Belongs to mce2 operon, involved in sulfolipid accumulation (Marjanovic et al. 2011) | — | Mouse (Marjanovic et al. 2010) | ++ | ++ | − | − | − | − |

| Rv0890c | — | Transcriptional regulator | Regulation | — | DC (Mendum et al. 2015) | — | ++ | ++ | − | − | − | − |

| Rv0893c | — | SAM methyltransferase | Secondary metabolism | — | M (Zhang et al. 2013) | — | ++ | ++ | − | − | − | − |

| Rv0895 | — | DAG-O-acyltransferase | Secondary metabolism (lipids) | — | M (Rengarajan et al. 2005) and DC (Mendum et al. 2015) | — | ++ | ++ | − | − | + | − |

| Rv0977 | PE_PGRS16 | PE_PPE | Secreted and surface proteins | — | DC (Mendum et al. 2015) | — | ++ | − | ++ | − | ++ | − |

| Rv1288 | — | Putative mycolyltransferase II | Secondary metabolism (lipids) | — | DC (Mendum et al. 2015) | — | ++ | ++ | − | − | + | − |

| Rv1359 | — | Transcriptional regulator | Regulation | — | DC (Mendum et al. 2015) | — | ++ | + | − | − | − | − |

| Rv1442 | bisC | Biotin sulfoxide reductase | Electron transfer activity | Oxidative stress resistance (putative) | DC (Mendum et al. 2015) | — | ++ | ++ | ++ (p) | + | ++ (p) | − |

| Rv1552 | frdA | Fumarate reductase subunit | Electron transfer activity | Hypoxia adaptation (Watanabe et al. 2011). Phagosome acidification arrest (Stewart et al. 2005) | DC (Mendum et al. 2015) | — | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | − |

| Rv1739c | sulP | Transporter | Transport | Sulfate uptake (Zolotarev et al. 2008) | DC (Mendum et al. 2015) | — | ++ | − | ++ | + | − | − |

| Rv1981c | nrdF1 | DNA-methylase | Regulation | Deleted in M. bovis BCG strains (RD2) | — | Mouse (Kozak et al. 2011) | ++ | ++ | − | − | + | − |

| Rv2275 | — | Cyclopeptide synthase | Secondary metabolism (mycocyclosin) | — | — | Mouse (Sassetti and Rubin 2003) | ++ | + | − | ++ | − | − |

| Rv2328 | PE23 | PE_PPE | Secreted and surface proteins | — | M (Stewart et al. 2005) | — | ++ | + | − | − | − | − |

| Rv2547 | vapC19 | Toxin–antitoxin | Regulation | Induced within granulomas (Hudock et al. 2017). | M (Stewart et al. 2005) | — | ++ | − | ++ | − | ++ | − |

| Rv2548 | vapB19 | Toxin–antitoxin | Regulation | Induced within granulomas (Hudock et al. 2017) | M (Stewart et al. 2005) | — | ++ | − | ++ | − | ++ | − |

| Rv2549c | vapC20 | Toxin–antitoxin | Regulation | — | M (Stewart et al. 2005) | — | ++ | − | ++ | − | ++ | − |

| Rv2550c | vapB20 | Toxin–antitoxin | Regulation | — | M (Stewart et al. 2005) | — | ++ | − | ++ | − | ++ | − |

| Rv2735c | — | — | — | — | DC (Mendum et al. 2015) | — | − | − | ++ | − | + | − |

| Rv2954c | — | Fucosyltransferase | Secondary metabolism (phenolglycolipid) | — | M (Rosas-Magallanes et al. 2007) | — | ++ | ++ | − | − | − | − |

| Rv2955c | — | Fucosyltransferase | Secondary metabolism (phenolglycolipid) | — | M (Rosas-Magallanes et al. 2007) | — | ++ | ++ | − | − | − | − |

| Rv3082c | virS | Transcriptional regulator | Regulation | Activation of Myma operon upon acidic pH and within phagosome (Singh et al. 2003) | M (Singh et al. 2005) | Guinea pig (Singh et al. 2005) | ++ | ++ | − | − | − | − |

| Rv3087 | — | DAG-O-acyltransferase | Secondary metabolism (lipids) | Belongs to Myma operon, involved in mycolic acid content (Singh et al. 2005) | M (Singh et al. 2005) | Mouse (Sassetti and Rubin 2003), Guinea pig (Singh et al. 2005) | ++ | ++ | − | − | − | − |

| Rv3179 | — | — | — | — | DC (Mendum et al. 2015) | — | ++ | − | − | + | + (p) | − |

| Rv3320c | vapC44 | Toxin–antitoxin | Regulation | Induced in nutrient starvation conditions (Albrethsen et al. 2013) | — | Mouse deltaMHC (Zhang et al. 2013) | ++ | − | − | + | + | − |

| Rv3343c | PPE54 | PE_PPE | Secreted and surface proteins | Oxidative stress resistance (Mestre et al. 2013) | DC (Mendum et al. 2015) | — | ++ | − | + | − | ++ | − |

| Rv3345c | PE_PGRS50 | PE_PPE | Secreted and surface proteins | — | DC (Mendum et al. 2015) | — | − | − | + | − | ++ | − |

| Rv3376 | — | Phosphatase | Secondary metabolism (diterpene 1TbAd) | Phagolysosome maturation arrest (Pethe et al. 2004) | M (Rengarajan et al. 2005) | — | ++ | + | − | + | − | − |

| Rv3377c | — | Diterpene synthase | Secondary metabolism (diterpene 1TbAd) | Phagolysosome maturation arrest (Pethe et al. 2004) | DC (Mendum et al. 2015) | — | ++ | ++ | − | ++ | − | − |

| Rv3476c | kgtP | Transporter | Transport | — | DC (Mendum et al. 2015) | — | ++ | ++ | − | − | − | − |

| Rv3487c | lipF | Lipase-esterase | Secondary metabolism (lipids) | Upregulated under acidic pH conditions (Richter and Saviola 2009) | — | Mouse (Camacho et al. 1999) | ++ | ++ | − | − | − | − |

| Rv3826 | fadD23 | Acyl-CoA synthetase | Secondary metabolism (sulfolipids) | Lower binding affinity for macrophages (Lynett and Stokes 2007) | DC (Mendum et al. 2015) | — | ++ | + | − | − | − | − |

Notes.—List of experimentally confirmed M. tuberculosis virulence genes that have at least one ortholog among other species of the MTBAP lineage (M. canettii is not included in the analysis) and no ortholog in any SGM depicted in the representative SGM database.

Presence of a putative ortholog by BBH-analysis.

Presence of a putative ortholog by BBH-analysis and synteny confirmation, -Absence of putative ortholog.

(p)Putative pseudogene.

Mtub, M. tuberculosis H37Rv; Mcan, M. canettii STBK; Mdec, M. decipiens; Mlac, M. lacus; Mriy, M. riyadhense.

Fig. 5.

—Representation of selected genomic islands. The genomic regions depict the fumarate reductase locus (Rv1552-1555), the Myma locus (Rv3082c-3087), or the sulfolipid synthesis locus (Rv3820c-3826), and the surrounding genomic regions in M. tuberculosis, M. decipiens, and M. kansasii. Pink links: homologous genomic regions. Filled arrows: genes in genomic islands.

Fig. 6.

—Hypothetical evolutionary scenario of the members of the MTBAP lineage. In this schematic representation, the likely evolutionary breakpoint is marked, beyond which the concerned members depict shared host-adapted traits.

Discussion

In the more than 20 years since the publication of the first complete mycobacterial genome sequence, featuring the reference strain M. tuberculosis H37Rv (Cole et al. 1998), the phenomenal increase in available sequence data has allowed an important refinement of the phylogenetic structure of the clonal population of M. tuberculosis and the MTBC to be achieved (Brosch et al. 2002; Mostowy et al. 2002; Gagneux and Small 2007; Comas et al. 2013). This information was further enriched by genome data from M. canettii strains, which share at least 98% sequence identity with M. tuberculosis strains, but differ from them by a highly recombinogenic population structure (Supply et al. 2013; Blouin et al. 2014; Boritsch et al. 2016b) and a yet unknown reservoir or environmental source. Apart from M. canettii, the closest known outgroups used until now for identifying M. tuberculosis-genome characteristics, and inferring its evolutionary history, were M. marinum (Stinear et al. 2008) and M. kansasii (Wang et al. 2015), which are both environmental mycobacteria characterized by substantially larger genomes (6.6 and 6.4 Mb, respectively) than M. tuberculosis (4.4 Mb) or M. canettii (4.5 Mb). This situation means that there was still a large gap between M. tuberculosis and the currently used outgroups, which implies that we had still not found the transitional forms (colloquially named “missing link”) between the professional, highly virulent pathogen M. tuberculosis and the more distantly related, much less virulent, environmental mycobacteria such as M. marinum or M. kansasii.

In this study, we thus undertook a global comparative genomic analysis of M. tuberculosis, M. canettii, and closely related mycobacterial species. Among them were some recently described mycobacterial species, which were reported to have high ANI values, and to be closely related to M. tuberculosis (Tortoli et al. 2017). ANI is a global pairwise similarity index that is a useful tool to delineate species delimitation (Konstantinidis and Tiedje 2007). However, ANI was never proven to be a faithful measure for longer evolutionary distances, and previous ANI-based studies did not rely on explicit bootstrap confidence values associated with the inferred phylogenetic trees. Hence, we used multi-gene concatenated sequence multiple alignment (Ankenbrand and Keller 2016), to establish a phylogenetic model with strong bootstrap values, which indicates that M. decipiens, M. lacus, M. riyadhense, and M. shinjukuense, as well as M. canettii and M. tuberculosis belong to a single phylogenetic lineage, termed MTBAP. Phenotypic and epidemiological characteristics of mycobacteria belonging to this MTBAP lineage suggest that they share some specific traits that are different from related environmental mycobacteria of the closest outgroup. Whereas M. gordonae, M. szulgai, M. marinum, or M. kansasii is commonly isolated from environmental water samples (Leoni et al. 1999; Le Dantec et al. 2002; Vaerewijck et al. 2005), species from the MTBAP lineage were exclusively recovered from human clinical patient samples (Turenne et al. 2002; Saad et al. 2015; Takeda et al. 2016; Brown-Elliott et al. 2018). Contrary to most environmental mycobacteria of the MGS–MKM group, all of the MTBAP members are nonpigmented and show optimal growth temperatures higher than 25 °C. Our results show that the nontuberculous members of the MTBAP lineage constitute a specific group of mycobacterial species sharing several genomic characteristics associated with host-adaptation, strongly supporting the hypothesis that ancestral founders of this lineage might represent pivotal evolutionary intermediates between the non- or low-virulent environmental mycobacteria and the highly virulent professional pathogens such as M. tuberculosis.

The study unveiled that specific genomic characteristics of MTB genomes, such as massive acquisition of toxin–antitoxin systems, were shared with most of the members of the MTBAP lineage. Indeed, our results suggest that the acquisition of a substantial part of the repertoire of M. tuberculosis VapBC and MazEF type II toxin–antitoxin systems was acquired in the MTBAP lineage before MTB speciation. In this perspective, M. decipiens represents as exception to the trend as this recently defined species does not seem to harbor the plethora of toxin–antitoxin encoding genes present in other members. To answer the question how this could happen, two working hypotheses may be proposed. The first hypothesis evokes that massive toxin–antitoxin acquisition occurred twice in the MTBAP lineage, due to convergent evolution dynamics whereas the second possible hypothesis suggests that massive toxin–antitoxin acquisition was initiated early in the MTBAP lineage ancestor, and that M. decipiens underwent a subsequent loss of most of these systems due to yet unknown reasons. Gene orthology and synteny analyses of toxin–antitoxin encoding genes suggest an ancestral acquisition for a significant part of these genes, and partial loss by certain members of the MTBAP lineage. This scenario means that a pivotal evolutionary breakpoint was initiated a long time before MTB speciation, giving rise to a distinct group of mycobacteria that likely evolved into opportunistic pathogens and acquired many of the characteristic features that today define the professional pathogen M. tuberculosis. Our attempts to estimate the putative emergence time of the last common ancestor of the MTBAP lineage using synonymous substitution comparisons with M. tuberculosis H37Rv, are consistent with previous calculations performed on a small gene set for M. canettii (Gutierrez et al. 2005). Synonymous mutations can be considered as neutral markers (Zuckerkandl and Pauling 1965; Kimura 1979) that linearly accumulate over time (Kishimoto et al. 2015). If we infer a constant mutation rate, our results suggest that the divergence between the MRCA of reference strain M. tuberculosis H37Rv and M. riyadhense occurred about 30 times earlier than the divergence between M. tuberculosis H37Rv and M. canettii STB-K, which is the most distantly related M. canettii strain relative to M. tuberculosis, known today (Supply et al. 2013; Blouin et al. 2014; Boritsch et al. 2014). Moreover, the MRCA of M. tuberculosis and either M. riyadhense, M. lacus, or M. shinjukuense is very close, suggesting an adaptive radiation process that might have occurred during, or soon after, the genomic evolutionary breakpoint that we can observe in the data sets. The estimations on the molecular clock rates for M. tuberculosis and the MTBC are still debated, as is it is difficult to calculate such rates for clonal organisms given certain evolutionary bottlenecks that may induce strong biases in long-term fixed mutation data (Comas and Gagneux 2009). Recent estimations based on genome analyses of ancient mycobacterial DNA from 1,000-year-old mummies placed the divergence of the clonal MTBC at about 6,000 years before present (Bos et al. 2014), which is one of the shortest evolutionary estimates for the MTBC, as by the use of other models the divergence time of the MTBC has been postulated to be up to 70,000 years (Comas et al. 2013). Using the shortest estimates, this would still suggest that the evolutionary breakpoint at the root of the MTBAP lineage occurred at least several hundred thousand years before M. tuberculosis specialization to the human host. However, previous studies on M. canettii genomic diversity reported phylogenetic profiles suggesting that M. canettii diversification might be 5–25 time more ancient than the rise of the clonal MTBC (Supply et al. 2013). Hence, under constant mutation rates, a rough estimate of the emergence of the MTBAP lineage would be 150–750 times earlier than the rise of the clonal MTBC. Although precise time estimates about the emergence of the MTBC are still under debate and will require further investigations on ancient DNAs (Donoghue 2016), our study reveals that major transitions in the evolutionary history of tuberculosis-causing mycobacteria occurred much earlier than previously thought, and were marked by early acquisition of host-adaptation characteristics shared with other nontuberculous mycobacteria of the MTBAP lineage. These reflections suggest a very long initiating period of co-evolution, with yet unknown hosts, that pre-dated MTB speciation and M. tuberculosis specialization as a human pathogen. Genomic reduction and expansion of toxin–antitoxin systems has been suggested to be correlated with gain in virulence (Dawson et al. 2018). Thus, the evolutionary breakpoint that gave rise to the MTBAP lineage might correspond to an, at least partial, transition point toward host-adapted lifestyle. Other features observed in our study, such as the loss of core genes observed in MTB, M. decipiens, M. shinjukuense, M. lacus, and to a lesser extent in M. riyadhense, and the specific MICFAM profiles support this hypothesis. The shift in core-genome dN/dS distribution pattern that we observe for MTB, M. decipiens, M. shinjukuense, and to a lesser extent for M. lacus, is a characteristic trait usually interpreted as a genomic marker associated with reduced population size and/or a genetic bottleneck that is consistent with specialized pathogen population dynamics. In agreement with previous reports, this pattern is considered as highly correlated with host-adaptation (Kuwahara et al. 2008; Kuo and Ochman 2009; Kjeldsen et al. 2012). Conversely, as observed for M. szulgai, M. marinum, and M. kansasii, this parameter is very stable within free-living, related bacteria (Kuo and Ochman 2009; Novichkov et al. 2009). Taken together, these trends are consistent with an early transition from free-living environmental to a specialized life-style within reduced ecological niches. Thereby, our results further support the hypothesis that the emergence of the MTBAP lineage included important steps toward a host-adapted lifestyle. This framework is consistent with a “quantum” evolutionary dynamic initiated by extensive genome-scale shifts, rather than by gradual evolution (Simpson 1944; Gould 1980). In this scenario, M. riyadhense, which is most distantly related to MTB within the MTBAP lineage, shows an intermediate pattern (with large toxin–antitoxin expansion, but only limited core-gene loss, a still-large genome size, and a dN/dS ratio similar to environmental species), suggesting a possible transitional form (“missing link”) at the root of the MTBAP lineage, that acquired some host-adaptation traits, but also conserved several traits associated with classical environmental life-style. These and all other results shed light on the emergence of MTB, and unveil pivotal transition that early shaped its major genomic characteristics, allowing us to propose a large-scale evolutionary model (fig. 6). Interestingly, this evolutionary scenario shows some similarities to a recently established extended model of the leprosy bacilli (Stinear and Brosch 2016). For many years it was thought that the etiological agent of human leprosy, Mycobacterium leprae, was an isolated, clonal species that had undergone massive genome decay (Cole et al. 2001) and was the sole agent of all forms of leprosy. However, more recent genome-based studies revealed that related leprosy bacilli, named Mycobacterium lepromatosis, shared significant genomic characteristics with M. leprae (Singh et al. 2015) and were responsible for particular leprosy-like pathologies in humans and in squirrels (Avanzi et al. 2016). Extensive genome analyses also established that these leprosy bacilli were closely related to the emerging pathogen Mycobacterium haemophilum (Tufariello et al. 2015), as well as to the most recently defined Mycobacterium uberis, an emerging skin pathogen in dairy animals (Benjak et al. 2018). It is clear from these observations that with the ongoing massive increase in the availability of bacterial genome sequences, important new insights into the evolution, phylogeny and population structure of key human pathogens may be obtained that can substantially revise our view on these agents and the diseases they cause.

Genome comparisons can reveal the molecular tools bacteria employ to establish a pathogenic lifecycle in selected hosts, that is to survive and proliferate within intracellular and/or extracellular host environments and induce lesions and disease. For M. tuberculosis these features represent key requirements for its efficient transmission to new hosts. Some major virulence factors of M. tuberculosis are very common functions shared by many mycobacteria, such as ESX systems (Dumas et al. 2016; Newton-Foot et al. 2016), which were refined and adapted by SGM pathogens for survival in the host (Groschel et al. 2016), whereby the independent acquisition of an apparent genomic island harboring ESX-associated genes espACD has likely played an important role (Ates and Brosch 2017; Orgeur and Brosch 2018). Other examples are the many genes involved in lipid metabolism, a most important feature for M. tuberculosis, given its lipid-rich cell envelope and its capacity to use host lipids as nutrients (Madacki et al. 2018). However, although such functions are necessary for virulence of M. tuberculosis, they cannot solely explain the specific transition to host-adaptation and pathogenicity, because many of them are also found in environmental mycobacteria. Previous studies on genomic comparisons of M. kansasii or M. marinum and MTB, detected major HGT events which were thought to have contributed to MTB emergence as host-associated mycobacteria (Rosas-Magallanes et al. 2006; Becq et al. 2007; Stinear et al. 2008; Wang and Behr 2014; Wang et al. 2015). However, in these former studies a wide evolutionary gap remained between MTB and the environmental mycobacteria that served as a comparison point, leaving decisive steps of MTB differentiation unexplored. Here, our RGP analysis showed that most of these genomic domains, previously thought to have been acquired by HGT during MTB differentiation from M. kansasii and/or M. marinum common ancestors, were also present in other species of the MTBAP lineage and thus apparently occurred already before MTB speciation. This observation was particularly striking for the toxin–antitoxin systems, which are reported to be involved in dormancy and resistance against environmental stresses induced by antibiotics or host immune defenses (Coussens and Daines 2016), as well as in pathogenicity (Lobato-Marquez et al. 2016). Indeed, our results suggest that some of these systems, which were apparently already acquired by early members of the MTBAP lineage, are involved in virulence, because M. tuberculosis vapC24 and vapC44 transposon insertion mutants are attenuated in selected animal infection models (Dutta et al. 2010; Zhang et al. 2013), whereas vapBC19 and vapBC20 were reported to be induced in granulomas (Hudock et al. 2017). Our study highlights the likely early acquisition of other major regulatory functions such as transcriptional regulators linked with pathogenicity (MosR, VirS, Rv1359 adenylate cyclase). All of these regulators are associated with mycobacterial lipids. A deletion mutant for the gene virS, for example, is affected in mycolic acid composition, spleen persistence in guinea pigs, and resistance to acidic stress (Singh et al. 2005), whereas a strain with a mosR deletion is deficient in phthiocerol dimycocerosate (PDIM) synthesis (Abomoelak et al. 2009). Moreover, the Rv1359 adenylate cyclase is probably involved in PDIM regulation (Camacho et al. 1999). PDIMs are among the first virulence factors that were identified for M. tuberculosis by using transposon insertion mutants and mouse infection models (Camacho et al. 1999; Cox et al. 1999). PDIMs were also shown to be involved in resistance to oxidative burst produced by macrophages, and modulation of immunity (Rousseau et al. 2004). Tight regulation of PDIM was shown to impact phagosomal damage and autophagy in host cells (Quigley et al. 2017), a finding that is also linked to the combined action with the ESX secretion system (Augenstreich et al. 2017). Our study shows that many potential virulence factors that were likely acquired during evolution of the MTBAP lineage before speciation of MTB exhibit many lipid-associated functions, and are involved in M. tuberculosis synthesis of specific mycomembrane components (such as sulfolipid synthesis, glycolipid glycosylation, and mycolic acid composition) (table 3). As outlined in the “Results” section, acquisition of concerned genes or gene clusters by HGT seems to have paved the way of selected MTBAP members to adopt a pathogenic lifestyle. The obtained insights allow prediction of the lipid content of the different MTBAP members, a feature that can thus be experimentally compared in future wet-lab-based lipid analyses and cell culture infection experiments. Based on our results from genome-based comparisons and analyses that place several species of nontuberculous mycobacteria into the immediate phylogenetic proximity of M. tuberculosis, a range of experiments can be designed to explore the specific roles played by the various molecular systems potentially involved in dormancy, survival under anaerobic conditions, and persistence of M. tuberculosis. Selected members of the MTBAP lineage could thereby serve as promising model organisms to find new, vulnerable features of M. tuberculosis, which can then be targeted by innovative new intervention strategies.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data are available at Genome Biology and Evolution online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the French National Research Council ANR (ANR-10-LABX-62-IBEID, ANR-16-CE35-0009, ANR-16-CE15-0003), the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (DEQ20130326471) and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program (643381). We thank Wafa Frigui and Jan Madacki for help and fruitful discussions. We are also grateful to the whole team of the Atelier de Bioinformatique (Museum d'Histoire Naturelle, ISYEB) for support and advice, and to Ariane Chaudot for participating in preliminary datamining approaches during a student internship.

Data deposition: No new sequence data.

Literature Cited

- Abomoelak B, et al. 2009. mosR, a novel transcriptional regulator of hypoxia and virulence in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Bacteriol. 191(19):5941–5952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrethsen J, et al. 2013. Proteomic profiling of Mycobacterium tuberculosis identifies nutrient-starvation-responsive toxin–antitoxin systems. Mol Cell Proteomics 12(5):1180–1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ.. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 215(3):403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ankenbrand MJ, Keller A.. 2016. bcgTree: automatized phylogenetic tree building from bacterial core genomes. Genome 59(10):783–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ates LS, Brosch R.. 2017. Discovery of the type VII ESX-1 secretion needle? Mol Microbiol. 103(1):7–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augenstreich J, et al. 2017. ESX-1 and phthiocerol dimycocerosates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis act in concert to cause phagosomal rupture and host cell apoptosis. Cell Microbiol. 19(7):e12726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avanzi C, et al. 2016. Red squirrels in the British Isles are infected with leprosy bacilli. Science 354(6313):744–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becq J, et al. 2007. Contribution of horizontally acquired genomic islands to the evolution of the tubercle bacilli. Mol Biol Evol. 24(8):1861–1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjak A, et al. 2018. Highly reduced genome of the new species Mycobacterium uberis, the causative agent of nodular thelitis and tuberculoid scrotitis in livestock and a close relative of the leprosy bacilli. mSphere 3(5):e00405–18.doi: 3/5/e00405-00418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betts JC, Lukey PT, Robb LC, McAdam RA, Duncan K.. 2002. Evaluation of a nutrient starvation model of Mycobacterium tuberculosis persistence by gene and protein expression profiling. Mol Microbiol. 43(3):717–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blouin Y, et al. 2014. Progenitor “Mycobacterium canettii” clone responsible for lymph node tuberculosis epidemic. Emerg Infect Dis. 20(1):21–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boritsch EC, et al. 2014. A glimpse into the past and predictions for the future: the molecular evolution of the tuberculosis agent. Mol Microbiol. 93(5):835–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boritsch EC, et al. 2016a. pks5-recombination-mediated surface remodelling in Mycobacterium tuberculosis emergence. Nat Microbiol. 1(2):15019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boritsch EC, et al. 2016b. Key experimental evidence of chromosomal DNA transfer among selected tuberculosis-causing mycobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 113(35):9876–9881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos KI, et al. 2014. Pre-Columbian mycobacterial genomes reveal seals as a source of New World human tuberculosis. Nature 514(7523):494–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosch R, et al. 2002. A new evolutionary scenario for the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 99(6):3684–3689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown-Elliott BA, et al. 2018. Mycobacterium decipiens sp. nov., a new species closely related to the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 68(11):3557–3562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho LR, Ensergueix D, Perez E, Gicquel B, Guilhot C.. 1999. Identification of a virulence gene cluster of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by signature-tagged transposon mutagenesis. Mol Microbiol. 34(2):257–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole ST, et al. 1998. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 393(6685):537–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole ST, et al. 2001. Massive gene decay in the leprosy bacillus. Nature 409(6823):1007–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comas I, et al. 2013. Out-of-Africa migration and Neolithic coexpansion of Mycobacterium tuberculosis with modern humans. Nat Genet. 45(10):1176–1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comas I, Gagneux S.. 2009. The past and future of tuberculosis research. PLoS Pathog. 5(10):e1000600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coussens NP, Daines DA.. 2016. Wake me when it's over—bacterial toxin–antitoxin proteins and induced dormancy. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 241(12):1332–1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox JS, Chen B, McNeil M, Jacobs WR Jr.. 1999. Complex lipid determines tissue-specific replication of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mice. Nature 402(6757):79–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling AC, Mau B, Blattner FR, Perna NT.. 2004. Mauve: multiple alignment of conserved genomic sequence with rearrangements. Genome Res. 14(7):1394–1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson CC, Cummings JE, Slayden RA.. 2018. Toxin–antitoxin systems and regulatory mechanisms in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Pathog Dis. 76(4):fty039:doi: 10.1093/femspd/fty039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donoghue HD. 2016. Paleomicrobiology of human tuberculosis. Microbiol Spectr. 4(4):PoH-0003-2014. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.PoH-0003–2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas E, et al. 2016. Mycobacterial pan-genome analysis suggests important role of plasmids in the radiation of type VII secretion systems. Genome Biol Evol. 8(2):387–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta NK, et al. 2010. Genetic requirements for the survival of tubercle bacilli in primates. J Infect Dis. 201(11):1743–1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dye C, Williams BG.. 2010. The population dynamics and control of tuberculosis. Science 328(5980):856–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabre M, et al. 2004. High genetic diversity revealed by variable-number tandem repeat genotyping and analysis of hsp65 gene polymorphism in a large collection of “Mycobacterium canettii” strains indicates that the M. tuberculosis complex is a recently emerged clone of “M. canettii”. J Clin Microbiol. 42(7):3248–3255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedrizzi T, et al. 2017. Genomic characterization of nontuberculous mycobacteria. Sci Rep. 7(1):45258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn RD, et al. 2006. Pfam: clans, web tools and services. Nucleic Acids Res. 34(Database issue):D247–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn RD, et al. 2008. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 36(Database issue):D281–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagneux S, Small PM.. 2007. Global phylogeography of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and implications for tuberculosis product development. Lancet Infect Dis. 7(5):328–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goris J, et al. 2007. DNA–DNA hybridization values and their relationship to whole-genome sequence similarities. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 57(Pt 1):81–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould SJ. 1980. G. G. Simpson, paleontology and the modern synthesis In:Mayr E, Provine WB, editors. The evolutionary synthesis. Cambridge (MA: ): Harvard University Press; p. 153–172. [Google Scholar]

- Groschel MI, Sayes F, Simeone R, Majlessi L, Brosch R.. 2016. ESX secretion systems: mycobacterial evolution to counter host immunity. Nat Rev Microbiol. 14(11):677–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez MC, et al. 2005. Ancient origin and gene mosaicism of the progenitor of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog. 1(1):e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy L, Kultima JR, Andersson SG.. 2010. genoPlotR: comparative gene and genome visualization in R. Bioinformatics 26(18):2334–2335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudock TA, et al. 2017. Hypoxia sensing and persistence genes are expressed during the intragranulomatous survival of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 56(5):637–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M. 1979. Model of effectively neutral mutations in which selective constraint is incorporated. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 76(7):3440–3444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishimoto T, et al. 2015. Molecular clock of neutral mutations in a fitness-increasing evolutionary process. PLoS Genet. 11(7):e1005392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjeldsen KU, et al. 2012. Purifying selection and molecular adaptation in the genome of Verminephrobacter, the heritable symbiotic bacteria of earthworms. Genome Biol Evol. 4(3):307–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konstantinidis KT, Tiedje JM.. 2007. Prokaryotic taxonomy and phylogeny in the genomic era: advancements and challenges ahead. Curr Opin Microbiol. 10(5):504–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak RA, Alexander DC, Liao R, Sherman DR, Behr MA.. 2011. Region of difference 2 contributes to virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 79(1):59–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo CH, Ochman H.. 2009. Inferring clocks when lacking rocks: the variable rates of molecular evolution in bacteria. Biol Direct 4(1):35–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwahara H, et al. 2008. Reductive genome evolution in chemoautotrophic intracellular symbionts of deep-sea Calyptogena clams. Extremophiles 12(3):365–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin MA, et al. 2007. ClustalW and ClustalX version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23(21):2947–2948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Dantec C, et al. 2002. Occurrence of mycobacteria in water treatment lines and in water distribution systems. Appl Environ Microbiol. 68(11):5318–5325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leoni E, Legnani P, Mucci MT, Pirani R.. 1999. Prevalence of mycobacteria in a swimming pool environment. J Appl Microbiol. 87(5):683–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levillain F, et al. 2017. Horizontal acquisition of a hypoxia-responsive molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis pathway contributed to Mycobacterium tuberculosis pathoadaptation. PLoS Pathog. 13(11):e1006752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W, et al. 2016. Transcriptional profiling of Mycobacterium tuberculosis exposed to in vitro lysosomal stress. Infect Immun. 84(9):2505–2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobato-Marquez D, Diaz-Orejas R, Garcia-Del Portillo F.. 2016. Toxin–antitoxins and bacterial virulence. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 40:592–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynett J, Stokes RW.. 2007. Selection of transposon mutants of Mycobacterium tuberculosis with increased macrophage infectivity identifies fadD23 to be involved in sulfolipid production and association with macrophages. Microbiology 153(Pt 9):3133–3140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madacki J, Mas Fiol G, Brosch R.. 2018. Update on the virulence factors of the obligate pathogen Mycobacterium tuberculosis and related tuberculosis-causing mycobacteria. Infect Genet Evol. 10:30955–30959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marjanovic O, Iavarone AT, Riley LW.. 2011. Sulfolipid accumulation in Mycobacterium tuberculosis disrupted in the mce2 operon. J Microbiol. 49(3):441–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marjanovic O, Miyata T, Goodridge A, Kendall LV, Riley LW.. 2010. Mce2 operon mutant strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is attenuated in C57BL/6 mice. Tuberculosis (Edinburgh) 90(1):50–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendum TA, Wu H, Kierzek AM, Stewart GR.. 2015. Lipid metabolism and Type VII secretion systems dominate the genome scale virulence profile of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in human dendritic cells. BMC Genomics 16(1):372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mestre O, et al. 2013. High throughput phenotypic selection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis mutants with impaired resistance to reactive oxygen species identifies genes important for intracellular growth. PLoS One 8(1):e53486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miele V, Penel S, Duret L.. 2011. Ultra-fast sequence clustering from similarity networks with SiLiX. BMC Bioinform. 12:116.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostowy S, Cousins D, Brinkman J, Aranaz A, Behr MA.. 2002. Genomic deletions suggest a phylogeny for the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. J Infect Dis. 186(1):74–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton-Foot M, Warren RM, Sampson SL, van Helden PD, Gey van Pittius NC.. 2016. The plasmid-mediated evolution of the mycobacterial ESX (Type VII) secretion systems. BMC Evol Biol. 16:62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novichkov PS, Wolf YI, Dubchak I, Koonin EV.. 2009. Trends in prokaryotic evolution revealed by comparison of closely related bacterial and archaeal genomes. J Bacteriol. 191(1):65–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orgeur M, Brosch R.. 2018. Evolution of virulence in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Curr Opin Microbiol. 41:68–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallen MJ, Wren BW.. 2007. Bacterial pathogenomics. Nature 449(7164):835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pethe K, et al. 2004. Isolation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis mutants defective in the arrest of phagosome maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 101(37):13642–13647. Epub 12004 Aug 13631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley J, et al. 2017. The cell wall lipid PDIM contributes to phagosomal escape and host cell exit of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. MBio 8(2):e00148-00117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachman H, et al. 2006. Unique transcriptome signature of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in pulmonary tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 74(2):1233–1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramage HR, Connolly LE, Cox JS.. 2009. Comprehensive functional analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis toxin–antitoxin systems: implications for pathogenesis, stress responses, and evolution. PLoS Genet. 5(12):e1000767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R-Core-Team. 2014. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. [Internet]. Vienna (Austria): R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

- Rengarajan J, Bloom BR, Rubin EJ.. 2005. Genome-wide requirements for Mycobacterium tuberculosis adaptation and survival in macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 102(23):8327–8332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter L, Saviola B.. 2009. The lipF promoter of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is upregulated specifically by acidic pH but not by other stress conditions. Microbiol Res. 164(2):228–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter M, Rossello-Mora R, Oliver Glockner F, Peplies J.. 2016. JSpeciesWS: a web server for prokaryotic species circumscription based on pairwise genome comparison. Bioinformatics 32(6):929–931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riojas MA, McGough KJ, Rider-Riojas CJ, Rastogi N, Hazbon MH.. 2018. Phylogenomic analysis of the species of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex demonstrates that Mycobacterium africanum, Mycobacterium bovis, Mycobacterium caprae, Mycobacterium microti and Mycobacterium pinnipedii are later heterotypic synonyms of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 68:324–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosas-Magallanes V, et al. 2006. Horizontal transfer of a virulence operon to the ancestor of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Biol Evol. 23(6):1129–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosas-Magallanes V, et al. 2007. Signature-tagged transposon mutagenesis identifies novel Mycobacterium tuberculosis genes involved in the parasitism of human macrophages. Infect Immun. 75(1):504–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau C, et al. 2004. Production of phthiocerol dimycocerosates protects Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the cidal activity of reactive nitrogen intermediates produced by macrophages and modulates the early immune response to infection. Cell Microbiol. 6(3):277–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saad MM, et al. 2015. Mycobacterium riyadhense infections. Saudi Med J. 36(5):620–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassetti CM, Rubin EJ.. 2003. Genetic requirements for mycobacterial survival during infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 100(22):12989–12994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schliep KP. 2011. phangorn: phylogenetic analysis in R. Bioinformatics 27(4):592–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simeone R, et al. 2013. Functional characterisation of three o-methyltransferases involved in the biosynthesis of phenolglycolipids in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS One 8(3):e58954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson GG. 1944. Tempo and mode in evolution. New York (NY: ): Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Singh P, et al. 2015. Insight into the evolution and origin of leprosy bacilli from the genome sequence of Mycobacterium lepromatosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 112(14):4459–4464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R, et al. 2003. Disruption of mptpB impairs the ability of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to survive in guinea pigs. Mol Microbiol. 50(3):751–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R, Singh A, Tyagi AK.. 2005. Deciphering the genes involved in pathogenesis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinburgh) 85(5–6):325–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart GR, Patel J, Robertson BD, Rae A, Young DB.. 2005. Mycobacterial mutants with defective control of phagosomal acidification. PLoS Pathog. 1(3):269–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinear TP, Brosch R.. 2016. Leprosy in red squirrels. Science 354(6313):702–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinear TP, et al. 2008. Insights from the complete genome sequence of Mycobacterium marinum on the evolution of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Genome Res. 18(5):729–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supply P, et al. 2013. Genomic analysis of smooth tubercle bacilli provides insights into ancestry and pathoadaptation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat Genet. 45(2):172–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suyama M, Torrents D, Bork P.. 2006. PAL2NAL: robust conversion of protein sequence alignments into the corresponding codon alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 34(Web Server issue):W609–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda K, et al. 2016. Six cases of pulmonary Mycobacterium shinjukuense infection at a single hospital. Intern Med. 55(7):787–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thioulouse J, Chessel D, Dolédec S, Olivier JM.. 1997. ADE-4: a multivariate analysis and graphical display software. Stat Comput. 7(1):75–83. [Google Scholar]

- Toft C, Andersson SGE.. 2010. Evolutionary microbial genomics: insights into bacterial host adaptation. Nat Rev Genet. 11:465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortoli E, et al. 2017. The new phylogeny of the genus Mycobacterium: the old and the news. Infect Genet Evol. 56:19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tufariello JM, et al. 2015. The complete genome sequence of the emerging pathogen Mycobacterium haemophilum explains its unique culture requirements. MBio 6(6):e01313-01315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turenne C, et al. 2002. Mycobacterium lacus sp. nov., a novel slowly growing, non-chromogenic clinical isolate. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 52(Pt 6):2135–2140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaerewijck MJ, Huys G, Palomino JC, Swings J, Portaels F.. 2005. Mycobacteria in drinking water distribution systems: ecology and significance for human health. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 29(5):911–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallenet D, et al. 2017. MicroScope in 2017: an expanding and evolving integrated resource for community expertise of microbial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 45(D1):D517–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veyrier FJ, Dufort A, Behr MA.. 2011. The rise and fall of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis genome. Trends Microbiol. 19(4):156–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Behr MA.. 2014. Building a better bacillus: the emergence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Front Microbiol. 5:139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, et al. 2015. Insights on the emergence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the analysis of Mycobacterium kansasii. Genome Biol Evol. 7(3):856–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe S, et al. 2011. Fumarate reductase activity maintains an energized membrane in anaerobic Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog. 7(10):e1002287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. 1997. PAML: a program package for phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Comput Appl Biosci. 13:555–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YJ, et al. 2013. Tryptophan biosynthesis protects mycobacteria from CD4 T-cell-mediated killing. Cell 155(6):1296–1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolotarev AS, et al. 2008. Increased sulfate uptake by E. coli overexpressing the SLC26-related SulP protein Rv1739c from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Comp Biochem Physiol Part A: Mol Integr Physiol. 149(3):255–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerkandl E, Pauling L.. 1965. Molecules as documents of evolutionary history. J Theor Biol. 8(2):357–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data