Abstract

Glutathione (GSH) is the major intracellular thiol that plays a role in numerous detoxification, bio-reduction, and conjugation reactions. The availability of Cys is thought to be the rate-limiting factor for the synthesis of GSH. The effects of immune system stimulation (ISS) on GSH levels and the GSH synthesis rate in various tissues, as well as the plasma flux of Cys, were measured in starter pigs fed a sulfur AA (SAA; Met + Cys) limiting diet. Ten feed-restricted gilts with initial body weight (BW) of 7.0 ± 0.12 kg were injected i.m. twice at 48-h intervals with either sterile saline (n = 4; ISS−) or increasing amounts of Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide (n = 6; ISS+). The day after the second injection, pigs received a primed constant infusion of 35S-Cys (9,300 kBq/pig/h) for 5 h via a jugular catheter. Blood and tissue free Cys and reduced GSH were isolated and quantified as the monobromobimane derivatives by HPLC. The rate of GSH synthesis was determined by measurement of the specific radioactivity of GSH and tissue free Cys at the end of the infusion period. Plasma Cys and total SAA levels were reduced (16% and 21%, respectively), but plasma Cys flux was increased (26%) by ISS (P < 0.05). Immune system stimulation increased GSH levels in the plasma (48%; P < 0.05), but had no effect on GSH levels in the liver, small and large intestines, heart, muscle, spleen, kidney, lung, and erythrocytes. The fractional synthesis rate (FSR) of GSH was higher (P < 0.05) in the liver (34%), small intestine (78%), large intestine (72%), heart (129%), muscle (37%), and erythrocytes (47%) of ISS+ pigs compared to ISS− pigs. The FSR of GSH tended (P = 0.08) to be higher in the lungs (45%) of ISS+ pigs than in ISS− pigs. The absolute rate of GSH synthesis was increased by ISS (mmol/kg wet tissue/d ± SE, ISS− vs. ISS+; P < 0.05) in the liver (5.22 ± 0.22 vs. 7.20 ± 0.59), small intestine (2.54 ± 0.25 vs. 4.52 ± 0.56), large intestine (0.61 ± 0.06 vs. 1.06 ± 0.16), heart (0.21 ± 0.03 vs. 0.48 ± 0.08), lungs (1.50 ± 0.10 vs. 2.90 ± 0.21), and muscle (0.21 ± 0.03 vs. 0.34 ± 0.04), but it remained unchanged in erythrocytes, the kidney, and the spleen (P > 0.80). The current findings suggest that GSH synthesis is increased during ISS, contributing to enhanced maintenance sulfur amino acid requirements in starter pigs during ISS.

Keywords: cysteine, glutathione, lipopolysaccharide, pig, synthesis rate

INTRODUCTION

In previous studies, it was observed that immune system stimulation (ISS) increased the extrapolated maintenance requirement for sulfur AA (SAA; Met + Cys) in growing pigs in an absorptive state (Rakhshandeh et al., 2014). We also observed that ISS upregulated glutathione (GSH) synthesis and use, as well as transsulfuration pathways, in various tissues at the transcriptional level in pigs (Rakhshandeh et al., 2010a, 2010b). The tripeptide GSH (l-γ-l-glutamyl-cysteinyl-glycine) is the major intracellular thiol that plays a critical role in numerous detoxification, bio-reduction, and conjugation reactions. It is also the second largest Cys reservoir, after skeletal muscle, in humans and animals (Anderson, 1998). Glutathione is synthesized in almost all organs in 2 sequential reactions catalyzed by glutamate-cysteine ligase (EC 6.3.2.2) and GSH synthetase (EC 6.3.2.3) (Lu, 2009). The availability of Cys is considered a rate-limiting factor for the synthesis of GSH (Grimble et al., 1992; Breuillé and Obled, 2000). Thus, the need for GSH during ISS may contribute to muscle protein mobilization when dietary Cys intake is insufficient (Reeds and Jahoor, 2001).

The mechanisms responsible for the maintenance of GSH homeostasis in individual tissues are poorly documented in pigs, especially during ISS. Therefore, the objective of the current study was to investigate the impact of ISS on the synthesis rate of GSH in the blood and in various tissues, thus elucidating the quantitative impact of moderate ISS on one of the major pathways of Cys utilization in growing pigs and providing a greater understanding of how ISS alters SAA utilization. We hypothesized that ISS increases the synthesis rate, and likely the pool size, of GSH, especially in the visceral tissues of pigs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The experimental protocol for this study was reviewed and approved by the University of Guelph Animal Care Committee (ACC approval number 09R104). This study was conducted at the University of Guelph Swine Research facility.

Animals, Housing, Diets, and Feeding

Ten Yorkshire gilts with an initial body weight (BW) of 7.0 ± 0.12 kg were obtained from the Arkell Swine Research Station (Arkell, ON, Canada), housed individually in metabolism crates, as described by Nyachoti et al. (2000), and surgically catheterized in the jugular veins. During the recovery period from the surgery, pigs had free access to a conventional corn-soybean meal based starter diet (NRC, 2012). After recovery from surgery, in a 4-d period, pigs were acclimatized to the semi-purified experimental diet in which SAA were first limiting among AA (Table 1; de Lange et al., 1989). The latter was achieved by ensuring that the ratios of essential standardized ileal digestible AA to SID SAA (Essential standardized ileal digestible amino acid: SAA) exceeded the recommendations of NRC Swine by at least 20% (Wang and Fuller, 1989; NRC, 2012). During the adaptation period and during the course of the study, pigs were fed 2.0 times the maintenance requirement for ME to avoid feed refusal, especially during ISS (NRC, 2012). Pigs were fed equal meals twice a day at 08:00 and 16:00 and had free access to water. Twenty-four hours prior to administering the isotope tracer infusion, pigs were fed at 4-h intervals to minimize the diurnal fluctuation in plasma SAA concentrations (Knipfel et al., 1972).

Table 1.

Ingredient compositions and nutrient contents of the experimental diet

| Ingredient composition, % (as is basis) | |

| Corn starch | 47.0 |

| Cellulose | 4.0 |

| Soy protein concentrate | 22.4 |

| Sucrose | 15 |

| Animal–vegetable fat blend | 7.0 |

| Limestone | 1.7 |

| Dicalcium phosphate | 1.8 |

| Salt | 0.5 |

| Swine premix1 | 0.6 |

| Calculated nutrient content, g/kg (as is basis) | |

| Dry matter | 880 |

| ME2 | 15.5 |

| Crude protein (N × 6.25) | 145.2 |

| Lys | 9.6 |

| Met | 2.0 |

| Cys | 2.3 |

| Thr | 6.4 |

| Trp | 2.0 |

| Leu | 12.2 |

| Ile | 7.6 |

| Val | 7.7 |

| Phe | 8.0 |

| Tyr | 5.8 |

| Ca | 10.6 |

| STTD P3 | 6.0 |

1Provided the following amounts of vitamins and trace minerals per kilogram of diet: vitamin A, 12,000 IU as retinyl acetate; vitamin D3, 1,200 IU as cholecalciferol; vitamin E, 48 IU as dl-α-tocopherol acetate; vitamin K, 3 mg as menadione; pantothenic acid, 180 mg; riboflavin, 6 mg; choline, 600 mg; folic acid, 2.4 mg; niacin, 30 mg; thiamine, 18 mg; pyridoxine, 1.8 mg; vitamin B12, 0.03 mg; biotin, 0.24 mg; Cu, 18 mg from CuSO4.5H2O; Fe, 120 mg from FeSO4; Mn, 124 mg from MnO2; Zn, 126 mg from ZnO; Se, 0.36 mg from Na2SeO3; I, 0.6 mg from KI (DSM Nutritional Products Canada Inc., Ayr, ON, Canada).

2The calculated value is given in MJ/kg.

3STTD P = Standardized total tract digestibility of phosphorus.

Surgery and Immune System Stimulation

Silicon catheters (Micro-Renathane, 0.095 O.D. × 0.066 I.D., Braintree Scientific Inc., Braintree, MA) were surgically inserted in the left and right external jugular veins according to the procedure originally described by Weirich et al. (1970) and modified by de Lange et al. (1989). During recovery, each pig was treated with 1 dose of the antibiotic Draxxin (2.5 mg/kg BW; Pfizer Canada Inc., Kirkland, QC, Canada), anti-inflammatory banamine (2.2 mg/kg BW i.m.), and the analgesic buprenorphine (0.01 mg/kg s.c.). Pigs were allowed to recover from surgery for 6 ± 1 d. At the end of the recovery period, pigs were randomly assigned to one of 2 treatments: control (ISS−; n = 4) and ISS (ISS+; n = 6). Pigs in the ISS+ group received 2 i.m. injections of increasing amounts of Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide (LPS; serotype 055:B5, Sigma-Aldrich Canada, Ltd., Oakville, ON, Canada), with a 48-h interval between injections (60 and 67 μg/kg BW; Rakhshandeh and de Lange, 2012). Pigs in the ISS− group were injected with a sterile saline solution.

Isotope Infusion

A sterile solution of 3.0 mCi/L (3.0 nmol/L) l-[35S] Cys (35S-Cys; PerkinElmer, Montreal, QC, Canada) containing sufficient amounts of the reducing reagent, dithiothreitol (DTT), was prepared in saline and infused via the left jugular catheter within 1 h of preparation. In the morning of the day after the second injection, and 2 h after feeding, a priming dose of 9,300 kBq/pig was given followed by a 5-h constant infusion of 9,300 kBq/pig/h of 35S-Cys using a Watson-Marlow Sci-Q 300 series peristaltic infusion pump (Watson-Marlow Fluid Technology Group, Wilmington, MA).

Observations and Sampling

Body weight was measured at the time of surgery, at the end of the recovery period, and immediately before the isotope infusion. Daily feed intake was monitored during the recovery period and ISS, as described by Rakhshandeh et al. (2014). Eye temperature was measured before surgery, every 48 h during the recovery period, and every 24 h after the start of ISS using an IR camera (ThermaCam SC2000; FLIRSystems, Inc., Wilsonville, OR), as previously described (Montanholi et al., 2008; Rakhshandeh et al., 2014). For monitoring plasma acute-phase proteins and complete blood cell counts, blood samples were taken before surgery and at day 2 and 7 post-surgery. Pre-surgical blood samples were taken by retro-orbital sinus bleeding (Dove and Alworth, 2015). In addition, blood samples were collected just before the start of ISS, as well as 24 and 48 h after the start of ISS. Blood samples were collected and processed as previously described (Rakhshandeh et al., 2014).

For determining specific radioactivity (SRA) and the levels of free Cys and GSH in the plasma, a 5 mL blood sample was drawn into a heparinized tube (BD Vacutainer, BD Franklin Lakes, NJ) via the right catheter just before the isotope infusion started and at 1-h intervals during the infusion. At the end of the infusion, pigs were euthanized by injection of a lethal dose of sodium pentobarbital (0.3 mg/kg BW; Virbac AH, Fort Worth, TX) via the infusion catheter. Immediately after euthanasia, a ventral abdominal incision was made, samples of liver, lung, kidney, small and large intestines, gastrocnemius muscle, spleen and heart were harvested, rinsed with physiological saline, blotted dry, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C. Tissue samples were ground in liquid nitrogen with a mortar and pestle (Fisher Scientific, Mississauga, ON, Canada), subdivided into 3 batches, and kept at −80 °C until further processing.

Chemical Analysis

All chemicals and reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Sigma-Aldrich Canada Ltd.) unless stated otherwise. All samples were analyzed in duplicate. Free Cys and total GSH in the blood and tissues were isolated and quantified using the high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) method, as described previously (Reid and Jahoor, 2000) with minor modifications. Briefly, 1 mL of blood was placed in an equal volume of ice-cold 10 mM monobromobimane (MBB; derivatization reagent, EMD Chemical Inc., Gibbstown, NJ) solution in Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 10 mM DTT, 50 mM serine, and 5 mM boric acid. Samples were incubated at room temperature in the dark for 30 min and centrifuged at 800 × g at 4 °C to separate the upper two thirds of the plasma and the lower two thirds of packed erythrocytes. An internal standard of cysteinyl–glycine (Cys–Gly) was added to an aliquot of the plasma, and packed erythrocytes were then lysed by freeze-thaw. The erythrocytes and plasma samples were deproteinized with ice-cold 7.0 M perchloric acid, neutralized with 7.0 M NaOH, and centrifuged at 800 × g for 15 min. The supernatant solution was filtered through a 0.45-µm syringe filter (Acrodisc, Fisher Scientific) and analyzed for Cys and total GSH simultaneously.

Tissue Cys and total GSH were extracted and also determined as MBB (EMD Chemical Inc.) derivatives. The pulverized frozen tissue samples were homogenized in 2.5 volume of (wt/vol) PBS buffer containing 50 mM serine, 10 mM MBB, 10 mM DTT, 5 mM boric acid, and Cys–Gly, as an internal standard, using a Wheaton glass tissue grinder (Fisher Scientific Company, Ottawa, ON, Canada; Cotgreave and Moldéus, 1986; Jahoor et al., 1995). After a 30-min incubation, proteins were precipitated from the homogenate with sufficient amounts of ice-cold perchloric acid (70 μL of 7 M). NaOH (7 M) was then added to neutralize the perchloric acid and samples were centrifuged at 800 × g for 15 min. The supernatant was filtered through a 0.45-µm syringe filter (Acrodisc, Fisher Scientific Company) and analyzed for Cys and total GSH.

The isolation and quantification of Cys and total GSH were carried out on a Spectra-Physics HPLC (Spectra-Physics, Arlington, IL) equipped with a SpectraSYSTEM FL 2000 fluorescence detector, SP8780 autosampler, SP8800 Ternary pump, and SP4290 integrator (all Spectra-Physics). Reverse phase separation of Cys and GSH was achieved on an Inertsil ODS-2, 5 µm column, 4.6 × 150 mm (Canadian Life Science, Toronto, ON, Canada; Cat # IN5020-01101-46). Elution of the thiols was accomplished over 20 min with Cys eluting at 9:0 and GSH at 13:0 min, as previously described (Jahoor et al., 1995). Cysteine and GSH peaks were collected starting at 1 min before the elution time for Cys and ending at 1 min after the elution time for GSH using a Cygnet-ISCO fraction collector (Lincoln, NE). The level of radioactivity (RA) in the collected fractions was determined by liquid scintillation counting using a Beckman LS 6000 liquid scintillation system (Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, CA) after adding 5.0 mL of Ecolite biodegradable scintillation fluid (Fisher Scientific Company).

Calculations

Specific radioactivity (dpm/nmol) of Cys and GSH were calculated from measured RA and their concentrations in either the plasma or the tissues were calculated according to Wolfe and Chinkes (2005) using the equation below:

where RA and Traceeconcentration are measured radioactivity of tracer (35S-Cys; dpm) and concentrations of free Cys or GSH (nmol) in the sample, respectively.

Plasma cysteine flux (FCys) was calculated according to Wolfe and Chinkes (2005) from the infusion rate of 35S-Cys (dpm/kg BW/h) and Cys SRA at plateau (dpm/nmol; average of CYS SRA during last 3 h of infusion), using the equation below.

The fractional synthesis rates (FSR; %/d) of GSH in various tissues and in erythrocytes were determined by measuring the rate of incorporation of 35S-Cys into tripeptide GSH using the equation described by Wolfe and Chinkes (2005):

where SRAGSH is the SRA (dpm/nmol) of GSH, SRACys is the SRA (dpm/nmol) of free Cys in the corresponding tissue, and t is the duration (h) of infusion. For each tissue, the absolute synthesis rate (ASR; mmol/kg or L of tissue/d) of GSH was calculated as the product of tissue GSH levels (mmol/kg or L tissue) and the corresponding FSR (%/d). Due to its hazardous nature, combined with the large dose of radioactive material that was infused, tissue weights were not determined. However, for determining 35S-GSH distribution in tissues, the pool size of GSH (PS; µmol/tissue) was estimated as the product of the tissue weight and the corresponding GSH levels, using data from Pluske et al. (2003) and the final BW of each ISS group. It was assumed that ISS increases the weights of liver, spleen, and small intestine by 11%, 58%, and 10%, respectively and reduces the skeletal muscle mass by 15% (Malmezat et al., 2000a; Rakhshandeh et al., 2010c). Distribution (or recovery) of 35S-GSH and 35SO4 in the tissues as a percentage of total 35S infused was determined using the following equation:

where SRA and PS are specific radioactivity (dpm/nmol) and estimated pool size (nmol/tissue) of GSH, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out using SAS software version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). One-time observations, such as the mean of Cys and GSH levels and the SRA in the tissues, were analyzed using a completely randomized design (CRD; PROC MIXED), with ISS as a fixed effect and litter as a random effect. Plasma GSH, SRA, plasma acute-phase protein levels, white blood cell counts, red blood cell counts, eye temperature, hematocrit, and hemoglobin levels were analyzed as repeated measurements in CRD (PROC MIXED). This model included ISS, time, and ISS × time as fixed effects, and litter as a random effect. An appropriate covariance structure was selected for analyses by fitting the model with the structure, which provided the “best” fit, based on Akaike information criterion and Schwarz Bayesian criterion. Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) was used for a comparison test. Treatment effects were considered significant at P ≤0.05. A tendency towards a significant difference between treatment means was also considered at 0.05 < P ≤ 0.10. Values were reported as means ± SE.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Measures of Immune Function, Blood Chemistry, and Final BW

Pigs readily consumed the diets during the recovery and ISS periods. The ISS+ pigs displayed some clinical signs of disease, such as lethargy, vomiting, and mild skin rashes; however, feed intake was not affected by ISS (P = 0.52). Dry matter from the vomit and wasted feed was negligible. At the end of the recovery period, all measures of immune response criteria were similar to those of pre-surgery and they were within the swine reference intervals (University of Guelph, Animal Health Laboratory User’s Guide and Fee Schedule), indicating a similar physiological status for all pigs at the beginning of the study. Repeated injection of increasing amounts of LPS resulted in altered plasma levels of acute-phase proteins, increased eye temperature, reduced red blood cell counts, and lowered final BWs (Table 2; P < 0.05), suggesting successful and effective systemic ISS (Rakhshandeh and de Lange, 2012, 2014). Thus, the experimental design used here allowed for assessment of the impact of ISS on the levels and synthesis rates of GSH in various tissues of pigs at a controlled level of nutrient intake. Importantly, in the current study, actual SAA intake was below the requirements for maximum body protein gains, which allowed SAA partitioning between protein deposition and GSH utilization to be assessed (Wang and Fuller, 1989).

Table 2.

Impacts of immune system stimulation (ISS) on blood cell counts, plasma levels of acute-phase proteins, eye temperature, and final body weight (BW) of starter pigs1

| Parameter | ISS− | ISS+ | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 4 | 6 | |

| WBC2, ×109/L | 18.6 ± 1.07 | 18.0 ± 0.81 | 0.62 |

| RBC2, × 1012/L | 5.11 ± 0.116 | 4.75 ± 0.114 | 0.05 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 89.0 ± 2.87 | 86.0 ± 1.82 | 0.40 |

| Hematocrit, L/L | 0.27 ± 0.007 | 0.26 ± 0.006 | 0.24 |

| Haptoglobin, g/L | 1.12 ± 0.079 | 1.35 ± 0.048 | 0.04 |

| Fibrinogen, g/L | 2.08 ± 0.133 | 3.00 ± 0.177 | 0.01 |

| Albumin, g/L | 26.4 ± 1.06 | 23.4 ± 0.76 | 0.05 |

| Eye temperature3, °C | 36.5 ± 0.18 | 37.4 ± 0.19 | 0.01 |

| Final BW, kg | 11.5 ± 0.25 | 10.8 ± 0.23 | 0.03 |

| Average daily feed intake4, g/d | 464.5 ± 9.06 | 461.3 ± 14.30 | 0.85 |

1Data are least square mean values ± SE during the ISS period based on repeated measurements analyses of variance. Pigs with an initial body weight of 7.0 ± 0.12 kg were injected (i.m.) twice with either increasing amounts of lipopolysaccharide (ISS+) or a sterile saline solution (ISS−). The 2 injections occurred 48 h apart.

2WBC and RBC are white and red blood cell count, respectively.

3Eye temperatures were measured using an infrared imaging technique.

4Dry matter basis.

Blood and Tissue GSH Concentrations

The levels of total GSH in the blood and tissues are influenced by the animal’s nutritional and physiological status, i.e., disease (Jahoor et al., 1995; Malmezat et al., 2000a). Intracellular levels of GSH represent the balance between the rates of synthesis, uptake from the circulation, and loss from the cell (i.e., efflux, breakdown, and/or oxidation) (Reid and Jahoor, 2001). Plasma GSH levels, in contrast, primarily reflect the GSH synthesis rate in the liver and its subsequent efflux into the blood (Ookhtens and Mittur, 1994; Reid and Jahoor, 2001). In the current study, ISS increased GSH concentration only in the plasma (P < 0.05) and had no effect (P > 0.10) on GSH concentrations in other tissues (Table 3). Our results are in some contrast to those of other investigators, who reported an increase in GSH levels and pool size in various tissues during the onset of ISS (Grimble et al., 1992; Malmezat et al., 2000a; Alhamdan and Grimble, 2003). However, the increase in tissue GSH pool size in these studies can partially be explained by increased relative organ weights, since systemic inflammation leads to cell hypertrophy, and sometimes cell hyperplasia, in organs that are involved in the immune response (Kohl and Deutschman, 2008). In the present study, organ weights, and therefore the GSH pool size in the tissues, were not determined due to safety concerns associated with using high doses of RA. Therefore, tissue GSH levels were expressed as mmol/kg of tissue, which may account for the difference here versus other studies (Table 3). Alternatively, it is possible that our ISS model, in comparison to the different models used by other investigators, induced only a modest immune response that was insufficient to alter tissue GSH levels (Breuillé and Obled, 2000).

Table 3.

Impacts of immune system stimulation (ISS) on levels of glutathione (GSH) in the blood and various tissues of starter pigs1

| ISS− | ISS+ | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 4 | 6 | |

| Blood | |||

| Plasma2, µmol/L | 7.14 ± 0.88 | 10.6 ± 1.49 | 0.05 |

| Erythrocytes, mmol/L | 5.23 ± 1.52 | 3.45 ± 1.10 | 0.28 |

| Tissue, mmol/kg | |||

| Liver | 2.08 ± 0.11 | 2.06 ± 0.09 | 0.88 |

| Spleen | 1.30 ± 0.15 | 1.08 ± 0.06 | 0.22 |

| Small intestine | 1.09 ± 0.09 | 1.06 ± 0.09 | 0.83 |

| Large intestine | 0.58 ± 0.06 | 0.56 ± 0.03 | 0.80 |

| Heart | 0.61 ± 0.10 | 0.62 ± 0.05 | 0.92 |

| Lung | 0.76 ± 0.11 | 0.76 ± 0.08 | 0.95 |

| Kidney | 3.13 ± 0.27 | 3.12 ± 0.76 | 0.98 |

| Muscle | 0.24 ± 0.03 | 0.29 ± 0.01 | 0.25 |

1Data are least square means ± SE and were observed at the end of a 5-h continuous isotope tracer infusion. Pigs were injected i.m. 2 times with either increasing amounts of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (ISS+; n = 6) or a sterile saline solution (ISS−; n = 4). The 2 injections occurred 48 h apart. In the morning of the day after the second injection with LPS, pigs were given a primed constant i.v. infusion of 35S-cysteine. Total GSH levels were determined as monobromobimane derivatives by HPLC.

2Plasma least square means (±SE) results represent the best estimates of mean values that were obtained during 5 h of a continuous infusion with 35S-cysteine based on repeated measurements analysis of variance.

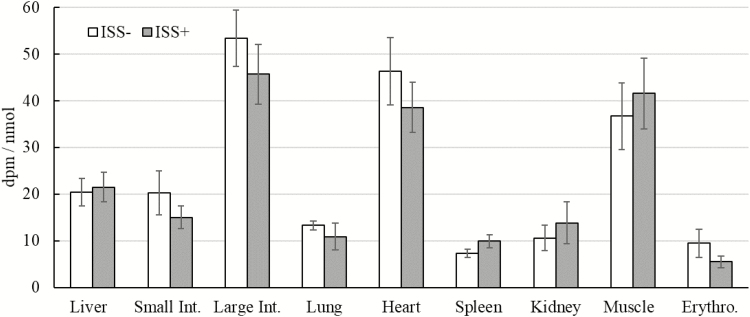

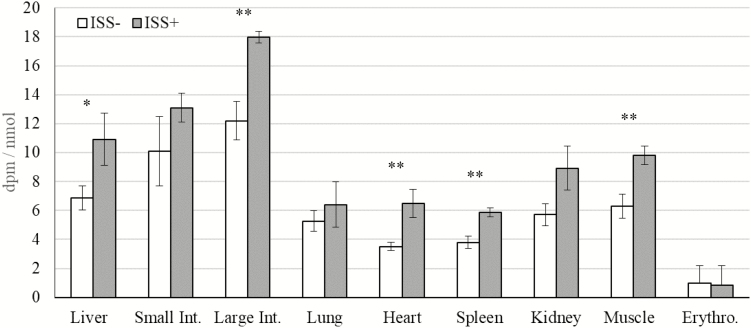

Isotopic Equilibrium in the Precursor Pools, and GSH SRA

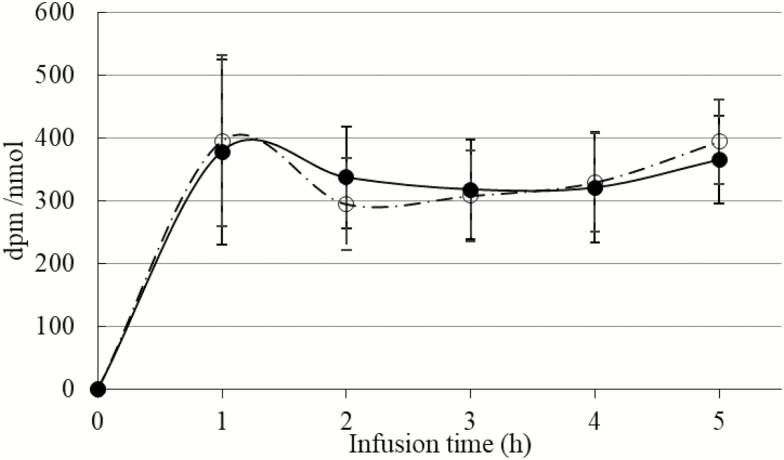

In the present study, a constant infusion of radioactive Cys was utilized to avoid the application of large doses of labeled Cys, which may cause changes in Cys metabolism or induce toxic effects (Stipanuk, 1999, 2004; Wolfe and Chinkes, 2005). In both ISS− and ISS+ pigs, free Cys SRA rose to a plateau within 1 h of starting the infusion and remained steady thereafter (Fig. 1; P > 0.44). Lack of an effect of ISS on plasma Cys SRA (Figs 1 and 2) suggested that the metabolic changes associated with hyper-activation of the immune system had no effect on the equilibrium of labeled Cys in the absorptive state in pigs (Wolfe and Chinkes, 2005). This finding is consistent with the findings in other studies in which various species and models of ISS were used (Jahoor et al., 1995; Malmezat et al., 1998). Also, ISS had no effect on the SRA of free Cys in the tissues (Fig. 3), suggesting that the isotopic equilibrium in the free Cys pool in the tissues was not affected by ISS (Wolfe and Chinkes, 2005). The SRA of GSH was higher in the liver, large intestine, heart, spleen, and muscle of ISS+ pigs than in ISS− pigs (Fig. 4; P < 0.05). A tendency towards an increase in the SRA of GSH was observed in the kidney of ISS+ pigs (Fig. 4; P < 0.09). Thus, our results indicated that in these tissues, ISS increased incorporation of labeled Cys into GSH (Wolfe and Chinkes, 2005).

Figure 1.

Impact of immune system stimulation (ISS) on plasma free cysteine (Cys) specific radioactivity in pigs. Pigs with an initial BW of 7.0 ± 0.12 kg were injected (i.m.) every 48 h (total of 2 injections) with either increasing amounts of lipopolysaccharide (ISS+; n = 6; white circles) or a sterile saline solution (ISS−; n = 4; black circles). Two days after the start of ISS, pigs were given a primed constant i.v. infusion of 35S-Cys. Plasma specific radioactivity of Cys (dpm/nmol) was determined as, Cys radioactivity (dpm)/Cys concentration (nmol).

Figure 2.

Impacts of immune system stimulation (ISS) on plasma levels of free Met + Cys and Cys, as well as the plasma Cys infusion rate, specific radioactivity (SRA) and flux. Data are least square mean values ± SE and were observed at the end of a 5-h continuous infusion of 35S-Cys. Pigs with an initial body weight of 7.0 ± 0.12 kg were injected (i.m.) every 48 h (total of 2 injections) with either increasing amounts of lipopolysaccharide (ISS+; n = 6) or sterile saline solution (ISS−; n = 4). Two days after the start of ISS, pigs were given a primed constant i.v. infusion of 35S-cysteine. Plasma SRA data are the average of the last 3 h of infusion when 35S-Cys SRA was at steady state. Plasma SRA of Cys was measured as, Cys radioactivity (dpm)/metabolite concentration (nmol). Plasma Cys flux was determined as, 35S-Cys infusion rate (dpm/kg BW/h)/SRA of 35S-Cys at steady state (dpm/nmol). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Figure 3.

Impacts of immune system stimulation (ISS) on the specific radioactivity (SRA) of 35S-Cys in selected tissues of starter pigs. Data are the least square means ± SE. Measurements was taken after 5 h of infusion. Six out of 10 pigs were injected (i.m.) every 48 h (total of 2 injections) with increasing amounts of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (ISS+). The remaining pigs (n = 4) were injected with a sterile saline solution (ISS−). In the morning of the day after the second injection with LPS, pigs were given a primed constant i.v. infusion of 35S-Cys for 5 h. Tissue SRA of Cys was measured as, Cys radioactivity (dpm)/metabolite concentration (nmol). Small Int. = small intestine; Large Int. = large intestine; Erythro. = erythrocyte. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Figure 4.

Impacts of immune system stimulation (ISS) on the specific radioactivity of glutathione (GSH) in various tissues of pigs. Data are the least square means ± SE and were observed at the end of a 5-h continuous isotope tracer infusion. Pigs were injected i.m. 2 times with either increasing amounts of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (ISS+; n = 6) or a sterile saline solution (ISS−; n = 4). The 2 injections occurred 48 h apart. In the morning of the day after the second injection with LPS, pigs were given a primed constant i.v. infusion of 35S-Cys. Glutathione was isolated and quantified as monobromobimane derivatives by HPLC. Specific radioactivity of GSH was determined as, GSH radioactivity (dpm)/GSH concentration in the tissue (nmol). Small Int. = small intestine; Large Int. = large intestine; Erythro. = erythrocyte. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Tissue GSH Synthesis Rates (FSR and ASR)

Few in vivo studies have been conducted that determine GSH synthesis in animal tissues using a direct method of measurement (Jahoor et al., 1995; Malmezat et al., 2000a), and to our knowledge, no study has measured the rate of GSH synthesis in pigs. In the current study, the rate of incorporation of labeled Cys into GSH was directly determined based on samples obtained after a 5-h continuous isotope tracer infusion. Several assumptions were made when calculating FSR and ASR: 1) that during the infusion period, the transfer of labeled GSH into and out of the tissue was negligible, 2) that the level of labeling in the free Cys pool was constant during the 5-h infusion period, and 3) that re-entry of labeled Cys from protein and GSH breakdown into the tissue free Cys pool was negligible (Waterlow et al., 1978; Wolfe and Chinkes, 2005). Indeed, import or export of labeled GSH, from the plasma or tissues during the infusion period, was minimal, as less than 4% of the total amount of 35S infused appeared in the plasma (Table 4). These assumptions may contribute to some systematic biases in the estimates of FSR and ASR of GSH in certain tissues. For example, these assumptions likely caused an underestimate of FSR in tissues that actively export GSH, such as the liver. This idea is supported by the observation that some labeled GSH appeared in the plasma, suggesting that some export of GSH occurred during the infusion period, even though this export was minimal. Moreover, the GSH synthesis rate was likely underestimated to a greater extent in ISS+ pigs than in ISS− pigs, since the rate of GSH export from the liver was higher in ISS+ pigs than in ISS− pigs. Despite this potential underestimation, the current study still found that the GSH synthesis rate was higher in the liver of ISS+ pigs, compared to ISS− pigs. Finally, we need to mention that the mathematical logic that was used in the current study to estimate PS might potentially affect the estimates of 35S-GSH distribution in tissues.

Table 4.

Impacts of immune system stimulation (ISS) on the distribution of 35S-glutathione (GSH) in the tissues of starter pigs (% of total amount of 35S infused)1

| Tissue weight2, g | GSH, % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISS− | ISS+ | ISS− | ISS+ | P | |

| Liver | 278 | 309 | 0.28 ± 0.027 | 0.44 ± 0.063 | 0.05 |

| Small intestine | 322 | 354 | 0.16 ± 0.023 | 0.13 ± 0.019 | 0.42 |

| Large intestine | 103 | 103 | 0.02 ± 0.001 | 0.03 ± 0.001 | 0.01 |

| Lung | 136 | 136 | 0.02 ± 0.003 | 0.03 ± 0.010 | 0.70 |

| Heart | 63 | 63 | 0.005 ± 0.001 | 0.009 ± 0.001 | 0.05 |

| Spleen | 27 | 43 | 0.004 ± 0.001 | 0.009 ± 0.001 | 0.01 |

| Kidney | 70 | 70 | 0.019 ± 0.002 | 0.020 ± 0.002 | 0.82 |

| Muscle | 4,130 | 3,510 | 0.22 ± 0.045 | 0.31 ± 0.038 | 0.17 |

| Erythrocytes | 189 | 189 | 0.031 ± 0.01 | 0.029 ± 0.01 | 0.88 |

| Plasma | 531 | 531 | 0.013 ± 0.003 | 0.034 ± 0.003 | 0.01 |

| Urine | 158 | 140 | ND3 | ND | |

| Total | 0.78 ± 0.045 | 1.02 ± 0.087 | 0.04 |

1Data are least square means ± SE and were observed at the end of a 5-h continuous isotope tracer infusion. Pigs with an initial body weight of 7.0 ± 0.12 kg were injected (i.m.) every 48 h (total of 2 injections) with either increasing amounts of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (ISS+; n = 6) or a sterile saline solution (ISS−; n = 4). In the morning of the day after the second injection with LPS, pigs were given a primed constant i.v. infusion of 35S-cysteine. Radioactivity was measured for each end product and expressed as the percentage of total radioactivity infused during the 5-h infusion.

2Tissue weights were adapted from Pluske et al. (2003). It was assumed that ISS increases the weight of the liver, spleen, and small intestine by 11%, 58%, and 10%, respectively, and reduces the muscle mass by 15%.

3ND = Not determined.

Glutathione FSR was higher in the liver (34%), small intestine (78%), large intestine (72%), heart (129%), muscle (37%), and erythrocytes (47%) of ISS+ pigs compared to ISS− pigs (Table 5; P < 0.05). In lung tissue, GSH FSR tended to be higher (45%) in ISS+ pigs than in ISS− pigs (P = 0.08). Values for ASR were also higher in the liver, small intestine, large intestine, heart, lung, and muscle of ISS+ pigs than in those of ISS− pigs (Table 5; P < 0.05). The current findings suggest that pigs are able to at least maintain tissue GSH levels during moderate ISS, even with an increase in the net loss of GSH from the cell. In addition, these findings indicate that pigs increase whole-body GSH synthesis and turnover in response to the enhanced production and release of free radicals that often occur during ISS (Jahoor et al., 1995; Breuillé and Obled, 2000; Malmezat et al., 2000a; Grimble, 2008). This finding is consistent with our previous findings in which ISS altered the partitioning of SAA in favor of non-protein sulfur containing nitrogenous compounds, of which GSH is the main component (Hamadeh and Hoffer, 2001; Hou et al., 2003; Rakhshandeh et al., 2010c). Increased whole-body FSR and ASR of GSH may also have a quantitative impact on the metabolic demand and dietary requirements for Cys. In turn, impacts on the dietary requirements for Cys may then impact demands for Met and total sulfur-containing AA. Indeed, a study with rats showed that sepsis increased the irreversible conversion of Met to Cys via transsulfuration, which indicates an enhanced metabolic demand for Cys (Malmezat at al., 2000b). This idea may further be supported by the findings here, in conjunction with findings from another recent study, in which we observed a 111% increase in Met utilization in ISS pigs, as determined by plasma Met flux (McGilvray et al., 2019). Glutathione FSR was not affected by ISS in the kidney and spleen (P > 0.05), indicating that GSH utilization was not affected by ISS in these tissues (Grimble, 2008). Glutathione ASR was also not affected by ISS in the kidney, spleen, and erythrocytes (P > 0.05; Table 5). The lack of a statistical difference in erythrocyte ASR between ISS− and ISS+ pigs can in part be attributed to a numerical decrease in GSH levels of erythrocytes and a reduced erythrocyte count in ISS+ pigs. The findings of the current study are in general agreement with those in pigs and rats (Jahoor et al., 1995; Malmezat et al., 2000a). These results also indicated that the liver is the main site of GSH synthesis in both ISS− and ISS+ pigs (Tables 4 and 5; Fig. 4). Finally, ISS reduced (P < 0.05) the plasma levels of free Cys (16.3%) and Met + Cys, (19.3%), while it increased (P < 0.05) the plasma Cys flux (25.5%) suggesting an enhanced Cys utilization in immune challenged pigs (Fig. 2). The enhanced Cys utilization in ISS pigs can mainly be attributed to an increased use of Cys for the synthesis of GSH (as observed in this study), acute-phase proteins (Reeds et al., 1994), Cys-rich protective mucins/mucus (Faure et al., 2007), and taurine (Stipanuk, 1999; Rakhshandeh et al., 2010d). The increased Cys flux that was observed in ISS pigs in the current study is consistent with observed Cys flux in immune challenged humans, rats, and mice (Malmezat et al., 1998, 2000b; Lyons et al., 2001).

Table 5.

Impacts of immune system stimulation (ISS) on fractional and absolute synthesis rates (FSR and ASR) of glutathione (GSH) in the tissues of starter pigs1

| FSR2 (%/d) | ASR2 (mmol/kg) tissue/d) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISS− | ISS+ | P | ISS− | ISS+ | P | |

| N | 4 | 6 | 4 | 6 | ||

| Erythrocyte | 49.6 ± 7.02 | 72.8 ± 5.62 | 0.03 | 0.65 ± 0.21 | 0.61 ± 0.15 | 0.87 |

| Liver | 262 ± 22.3 | 350 ± 9.83 | 0.01 | 5.22 ± 0.22 | 7.20 ± 0.59 | 0.02 |

| Spleen | 254 ± 22.6 | 286 ± 35.7 | 0.47 | 3.21 ± 0.21 | 3.11 ± 0.39 | 0.83 |

| Small intestine | 235 ± 29.3 | 419 ± 26.3 | 0.01 | 2.54 ± 0.25 | 4.52 ± 0.56 | 0.01 |

| Large intestine | 112 ± 30.4 | 193 ± 16.1 | 0.05 | 0.63 ± 0.06 | 1.06 ± 0.16 | 0.04 |

| Heart | 35.2 ± 80.6 | 80.6 ± 13.6 | 0.01 | 0.21 ± 0.03 | 0.48 ± 0.08 | 0.01 |

| Lung | 194 ± 34.2 | 281± 27.9 | 0.08 | 1.50 ± 0.10 | 2.09 ± 0.21 | 0.04 |

| Kidney | 245 ± 38.7 | 318 ± 55.1 | 0.32 | 3.30 ± 0.31 | 3.73 ± 1.36 | 0.77 |

| Muscle | 85.9 ± 6.58 | 118 ± 11.9 | 0.05 | 0.21 ± 0.03 | 0.34 ± 0.04 | 0.05 |

1Data are least square means ± SE and were observed at the end of a 5-h continuous isotope tracer infusion. Pigs were injected i.m. 2 times with either increasing amounts of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (ISS+; n = 6) or a sterile saline solution (ISS−; n = 4). The 2 injections occurred 48 h apart. In the morning of the day after the second injection with LPS, pigs were given a primed constant i.v. infusion of 35S-cysteine (Cys). Cysteine and GSH were isolated and quantified as monobromobimane derivatives by HPLC.

2The FSR of GSH was calculated as [35S-GSH SRA (dpm/nmol)/35S-Cys SRA at steady state] × [24/5 h] × 100, where SRA is specific radioactivity. The ASR (mmol/kg or L tissue/d) was calculated as the product of tissue GSH levels (mmol/kg or L tissue) and the corresponding FSR (%/d).

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

The current findings indicated that in a fed state and during moderate systemic ISS, starter pigs are capable of at least maintaining tissue GSH levels. This maintenance is achieved by increasing GSH synthesis within a number of tissues. The observed increase in plasma Cys flux during ISS can be largely attributed to an increase in the utilization of Cys for the synthesis of GSH and other immune system metabolites. The present study suggests that increased Cys utilization during ISS may contribute to increased maintenance sulfur-containing amino acid requirements in starter pigs.

Footnotes

Financial support for this project was provided by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, Ontario Pork, Evonik Nutrition & Care GmbH, and Texas Tech University. This study was conducted at the University of Guelph Swine Research facility. All authors have no conflicts of interest.

LITERATURE CITED

- Alhamdan A. A., and Grimble R. F.. 2003. The effect of graded levels of dietary casein, with or without methionine supplementation, on glutathione concentration in unstressed and endotoxin-treated rats. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 73:468–477. doi: 10.1024/0300-9831.73.6.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M. E. 1998. Glutathione: an overview of biosynthesis and modulation. Chem. Biol. Interact. 111–112: 1–14. doi: 10.1016/S0009-2797(97)00146-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breuillé D., and Obled C.. 2000. Cysteine and glutathione in catabolic states. In: Fürst P. and Young V., editors, Proteins, peptides and amino acids in enteral nutrition. Nestlé Nutrition Workshop Series Clinical and Performance Program. Karger Publishers, Basel Switzerland: Vol. 3, p. 173–198. doi: 10.1159/000061807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotgreave I. A., and Moldéus P.. 1986. Methodologies for the application of monobromobimane to the simultaneous analysis of soluble and protein thiol components of biological systems. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods 13:231–249. doi:10.1016/0165-022X(86)90102-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dove C. R., and Alworth L. C.. 2015. Blood collection from the orbital sinus of swine. Lab Anim. (NY) 44:383–384. doi: 10.1038/laban.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faure M., Choné F., Mettraux C., Godin J. P., Béchereau F., Vuichoud J., Papet I., Breuillé D., and Obled C.. 2007. Threonine utilization for synthesis of acute phase proteins, intestinal proteins, and mucins is increased during sepsis in rats. J. Nutr. 137:1802–1807. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.7.1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimble R. 2008. Sulfur amino acids, glutathione, and immune function. In: Masella R. and Mazza G., editors, Glutathione and sulfur amino acids in human health and disease. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Hoboken, NJ: p. 273–288. [Google Scholar]

- Grimble R. F., Jackson A. A., Persaud C., Wride M. J., Delers F., and Engler R.. 1992. Cysteine and glycine supplementation modulate the metabolic response to tumor necrosis factor alpha in rats fed a low protein diet. J. Nutr. 122:2066–2073. doi: 10.1093/jn/122.11.2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamadeh M. J., and Hoffer L. J.. 2001. Use of sulfate production as a measure of short-term sulfur amino acid catabolism in humans. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 280:E857–E866. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.280.6.E857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou C., Wykes L. J., and Hoffer L. J.. 2003. Urinary sulfur excretion and the nitrogen/sulfur balance ratio reveal nonprotein sulfur amino acid retention in piglets. J. Nutr. 133:766–772. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.3.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahoor F., Wykes L. J., Reeds P. J., Henry J. F., del Rosario M. P., and Frazer M. E.. 1995. Protein-deficient pigs cannot maintain reduced glutathione homeostasis when subjected to the stress of inflammation. J. Nutr. 125:1462–1472. doi: 10.1093/jn/125.6.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knipfel J. E., Keith M. O., Christensen D. A., and, Owen B. D.. 1972. Diet and feeding interval effects on serum amino acid concentrations of growing swine. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 52: 143–153. doi: 10.4141/cjas72-016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kohl B., and Deutschman C.. 2008. The inflammatory response in organ injury. In: Newman M. F., Fleisher L. A., and Fink M. P., editors, Perioperative medicine: managing for outcome. Elsevier Health Sciences, Philadelphia, PA: p. 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- de Lange C. F., Sauer W. C., and Souffrant W.. 1989. The effect of protein status of the pig on the recovery and amino acid composition of endogenous protein in digesta collected from the distal ileum. J. Anim. Sci. 67:755–762. doi: 10.2527/jas1989.673755x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu S. C. 2009. Regulation of glutathione synthesis. Mol. Aspects Med. 30:42–59. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, J., A. Rauh-Pfeiffer, Y. Ming-Yu, X. Lu, D. Zurakowski, M. Curley, S. Collier, C. Duggan, S. Nurko, J. Thompson, et al. 2001. Cysteine metabolism and whole blood glutathione synthesis in septic pediatric patients. Crit. Care Med. 29:870–877. doi:10.1097/00003246-200104000-00036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmezat T., Breuillé D., Capitan P., Mirand P. P., and Obled C.. 2000a. Glutathione turnover is increased during the acute phase of sepsis in rats. J. Nutr. 130:1239–1246. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.5.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmezat T., Breuillé D., Pouyet C., Buffière C., Denis P., Mirand P. P., and Obled C.. 2000b. Methionine transsulfuration is increased during sepsis in rats. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 279:E1391–E1397. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.279.6.E1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmezat T., Breuillé D., Pouyet C., Mirand P. P., and Obled C.. 1998. Metabolism of cysteine is modified during the acute phase of sepsis in rats. J. Nutr. 128:97–105. doi: 10.1093/jn/128.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGilvray W. D., Klein D., Wooten H., Dawson J. A., Hewitt D., Rakhshandeh A. R., de Lange C. F.M., and Rakhshandeh A.. 2019. Immune system stimulation induced by porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus alters amino acid kinetics and dietary nitrogen utilization in nursery pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 97:315–326. doi: 10.1093/jas/sky401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montanholi Y. R., Odongo N. E., Swanson K. C., Schenkel F. S., McBride B. W., and Miller S. P.. 2008. Application of infrared thermography as an indicator of heat and methane production and its use in the study of skin temperature in response to physiological events in dairy cattle (Bos taurus). J. Therm. Biol. 33:468–475. doi: 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2008.09.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council (NRC). 2012. Nutrient requirements of swine. 11th ed. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Nyachoti C. M., de Lange C. F., McBride B. W., Leeson S., and Gabert V. M.. 2000. Endogenous gut nitrogen losses in growing pigs are not caused by increased protein synthesis rates in the small intestine. J. Nutr. 130:566–572. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.3.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ookhtens M., and Mittur A. V.. 1994. Developmental changes in plasma thiol-disulfide turnover in rats: a multicompartmental approach. Am. J. Physiol. 267(2 Pt 2):R415–R425. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.267.2.R415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluske J., Kerton D., Cranwell P., Campbell R., Mullan B., King R., Power G., Pierzynowski S., Westorm B., Rippe C., Peulen O., and Dunshea F. R.. 2003. Age, sex, and weight at weaning influence organ weight and gastrointestinal development of weanling pigs. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 54:515–527. doi: 10.1071/AR02156 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rakhshandeh A., Holliss A., Karrow N., and de Lange C. F. M.. 2010a. Immune system stimulation and sulfur amino acid intake alter the pathways of glutathione metabolism at transcription level in pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 88 (E-Suppl. 2):256. [Google Scholar]

- Rakhshandeh A., Holliss A., Karrow N. A., and de Lange C. F. M.. 2010b. Impact of sulfur amino acid intake and immune system stimulation on pathways of sulfur amino acid metabolism at transcriptional level in growing pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 88 (E-Suppl. 2):489. [Google Scholar]

- Rakhshandeh A., Htoo J. K., Karrow N., Miller S. P., and de Lange C. F.. 2014. Impact of immune system stimulation on the ileal nutrient digestibility and utilisation of methionine plus cysteine intake for whole-body protein deposition in growing pigs. Br. J. Nutr. 111:101–110. doi: 10.1017/S0007114513001955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakhshandeh A., Htoo J. K., and de Lange C. F. M.. 2010c. Immune system stimulation of growing pigs does not alter apparent ileal amino acid digestibility but reduces the ratio between whole body nitrogen and sulfur retention. Livest. Sci. 134:21–23. doi: 10.1016/j.livsci.2010.06.085 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rakhshandeh A., and de Lange C. F.. 2012. Evaluation of chronic immune system stimulation models in growing pigs. Animal 6:305–310. doi: 10.1017/S1751731111001522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakhshandeh A., de Ridder K., Htoo J. K., and de Lange C. F. M.. 2010d. Immune system stimulation alters plasma cysteine kinetics in growing pigs. In: Crovetto G. M., editor, Energy and protein metabolism and nutrition. Wageningen Academic Publishers, Wageningen, the Netherlands: Vol. 127 p. 509–510. [Google Scholar]

- Reeds P. J., Fjeld C. R., and Jahoor F.. 1994. Do the differences in amino acid composition of acute phase and muscle proteins have a bearing on nitrogen loss in traumatic states? J. Nutr. 124:906–910. doi: 10.1093/jn/124.6.906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeds P. J., and Jahoor F.. 2001. The amino acid requirements of disease. Clin. Nutr. 20:15–22. doi: 10.1054/clnu.2001.0402 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reid M., and Jahoor F.. 2000. Methods for measuring glutathione concentration and rate of synthesis. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 3:385–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid M., and Jahoor F.. 2001. Glutathione in disease. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 4:65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stipanuk M. H. 1999. Homocysteine, cysteine and taurine. In: Shils M. E., Olson J. A., Shike M., and Ross A. C., editors, Modern nutrition in health and disease. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, MD: p. 543–558. [Google Scholar]

- Stipanuk M. H. 2004. Sulfur amino acid metabolism: pathways for production and removal of homocysteine and cysteine. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 24:539–577. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.24.012003.132418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T. C., and Fuller M. F.. 1989. The optimum dietary amino acid pattern for growing pigs. 1. Experiments by amino acid deletion. Br. J. Nutr. 62:77–89. doi:10.1079/BJN19890009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterlow J. C., Garlick P. J., and Millward D. J.. 1978. General principles of the measurement of whole-body protein turnover. In: Protein turnover in mammalian tissues and in the whole body. North-Holland Publishing Company, Amsterdam, the Netherlands: p. 225–249. [Google Scholar]

- Weirich W. E., Will J. A., and Crumpton C. W.. 1970. A technique for placing chronic indwelling catheters in swine. J. Appl. Physiol. 28:117–119. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1970.28.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe R. R., and Chinkes D. L.. 2005. Calculation of substrate kinetics: single pool model. In: Isotope tracers in metabolic research: principles and practice of kinetic analysis. 2nd ed. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ: p. 21–50. [Google Scholar]