Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text

Keywords: chemotherapy, cinobufotalin injection, meta-analysis, non-small cell lung cancer, traditional Chinese medicine

Abstract

Background and objective:

Cinobufotalin injection (CFI), a kind of Chinese medicine, has been considered as a promising complementary therapy option for advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), but their efficacy and safety remain controversial. This study aimed to systematically evaluate the efficacy and safety of CFI and chemotherapy-combined therapy for advanced NSCLC.

Methods:

Clinical trials were searched from Web of Science, Cochrane Library, PubMed, Embase, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Chinese Biological Medicine Database (CBM), Chinese Medical Citation Index (CMCI), Wanfang database and Chinese Scientific Journal Database (VIP). Main measurements, including therapeutic efficacy, quality of life (QoL) and adverse events, were extracted from the retrieved publications and were systematically evaluated.

Results:

The 29 trials including 2300 advanced NSCLC patients were involved in this study. Compared with chemotherapy alone, its combination with CFI significantly prolonged the patients’ 1-, 2- and 3-year overall survival rate (OS) (1-year OS, OR = 1.94, 95% CI = 1.42–2.65, P < .0001; 2-year OS, OR = 2.31, 95% CI = 1.55–3.45, P < .0001; 3-year OS, OR = 4.69, 95% CI = 1.78–12.39, P = .002) and improved patients’ overall response (ORR, OR = 1.84, CI = 1.54–2.18, P < .00001), disease control rate (DCR, OR = 2.09, 95% CI = 1.68–2.60, P < .00001) and QoL (quality of life improved rate, QIR, OR = 2.64, 95% CI = 1.98–3.52, P < .00001; karnofsky performance score, KPS, OR = 10.97, 95% CI = 5.48–16.47, P < .0001). Most adverse events caused by chemotherapy were obviously alleviated (P < .05) when CFI was also applied to patients.

Conclusion:

The combination of CFI and chemotherapy is safe, and is more effective in treating NSCLC than chemotherapy alone. Therefore, CFI mediated therapy could be recommended as an adjuvant treatment method for NSCLC.

1. Introduction

Lung cancer represents the first leading cause of death among all cancer types and caused 1,600,000 deaths every year in the whole world.[1,2] China is a high risk area for lung cancer, and has the most new lung cancer cases (733,300 per year) accounting for about 40% in the world.[3,4] Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is constitutes for approximately 85% of all lung cancer cases.[4,5] Approximately 2/3 of NSCLC patients are diagnosed at advanced stages, under which condition they were not able to be applied with radical treatment such as surgery,[4] leaving traditional chemotherapy as their primary treatment option. However, chemotherapy's therapeutic efficacy was unsatisfied for advanced NSCLC, and patients also endured its toxicity and a compromised quality of life (QoL).[6]

In recent years, traditional Chinese medicine has been more widely used as compounds for chemotherapy, and showed promising therapeutic effects in cancer treatment.[7–9] Cinobufotalin contains bufadienolides and cardiotonic steroids extracted from the skin secretions of bufo gargarizans.[10–12] Evidences emerged from in vitro studies have demonstrate cinobufotalin's anti-tumor activity, accompanied with enhanced chemotherapeutic effects.[7,13] Sheng et al[10] found that cinobufotalin can kill lung cancer cells by inducing non-apoptotic death possibly depending on Cyp-D involved pathway. Emam et al[11] showed that cinobufotalin induced lymphoma cells apoptosis through Caspase- mediated Fas apoptotic pathway. In addition, cinobufotalin was also able to induce tumor cell apoptosis by increasing reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and interfering their DNA structure.[11,14]

Several clinic trials have revealed the prominent therapeutic effects of cinobufotalin injection (CFI) and chemotherapy-combined therapy for advanced NSCLC, which was also proved more effective than chemotherapy alone.[15–17] Despite the intensive clinical studies using CFI and chemo-combined therapy in treating NSCLC, its clinical efficacy and safety has not been systematically evaluated. In this study, we performed a meta-analysis to evaluate the efficacy and safety for NSCLC treatment, with a comparison between CFI and chemo-combined therapy and chemotherapy alone, in order to provide scientific reference for the design of future clinical trials.

2. Materials and methods

This meta-analysis was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) guidelines. The ethical approval and patient consent are not required because this study was a meta-analysis.

2.1. Search strategy and selection criteria

Literatures were searched across Web of Science, Cochrane Library, PubMed, Embase, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Chinese Biological Medicine Database (CBM), Chinese Medical Citation Index (CMCI), Wanfang database and Chinese Scientific Journal Database (VIP) from January 2000 to June 2018, with key terms “cinobufotalin” or “cinobufotalin” or “cinobufacini” or “cinobufagin” or “huachansu” combined with “lung cancer” or “lung carcinoma” or “lung neoplasm” or “non-small cell lung cancer” or “NSCLC” without restriction on the language (Supplementary Table 1).

Selection standards: trials brought into this analysis were randomized controlled trials (RCT) with reference to advanced NSCLC, in which patients in the experimental groups were treated by CFI (intravenous infusion) and chemo-combined therapy, and patients in the control groups were treated by solely chemotherapy.

2.2. Data extraction and quality assessment

Two investigators respectively collected and summarized the following information from the involved studies: names of first authors, years of publication, study locations, tumor stages, number of cases, patient ages, study parameter types, treatment regimens and periods, administration route and expected survival time. Quality of the involved clinical trials was assessed as instructed by Cochrane Handbook.[18]

2.3. Outcome definition

The following clinical responses were taken into analysis in this study: therapeutic effects, QoL and adverse events. Therapeutic effects were evaluated by overall survival rate (OS), complete response rates (CR), partial response rates (PR), stable disease rates (SD), progressive disease rates (PD), overall response rate (ORR, ORR = CR + PR), and disease-control rate (DCR, DCR = CR + PR + SD). QoL improved rate (QIR) and karnofsky performance score (KPS) was used to reflect patients QoL. Adverse events taken into assessment included leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, nausea and vomiting, hepatotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, gastrointestinal side effects, diarrhea, peripheral neurotoxicity, granulopenia, phlebitis, alopecia, myelosuppression, constipation, hemoglobin reduction, allergy, and anemia.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Review Manager 5.3 (Cochrane Collaboration) was the main statistical analysis tool in this study. P < .05 indicates difference with statistical significance. Analysis model was determined by heterogeneity among studies assessed by Cochran's Q test, and publication bias was analyzed by Begg and Egger regression asymmetry tests and presented by funnel plots.[19]I2 < 50% or P > .1 indicated the studies were homogenous. Therapeutic effects were mainly represented by odds ratio (OR) presented with a 95% confidence interval (CI).

Pooled analysis with publication bias determined that trim-and-fill method would be applied to coordinate the estimates of unpublished studies, and the adjusted results were compared with the original pooled OR.[20] Sensitivity analysis was conducted to evaluate the impact of different therapeutic regimens and sample sizes.

3. Results

3.1. Search results

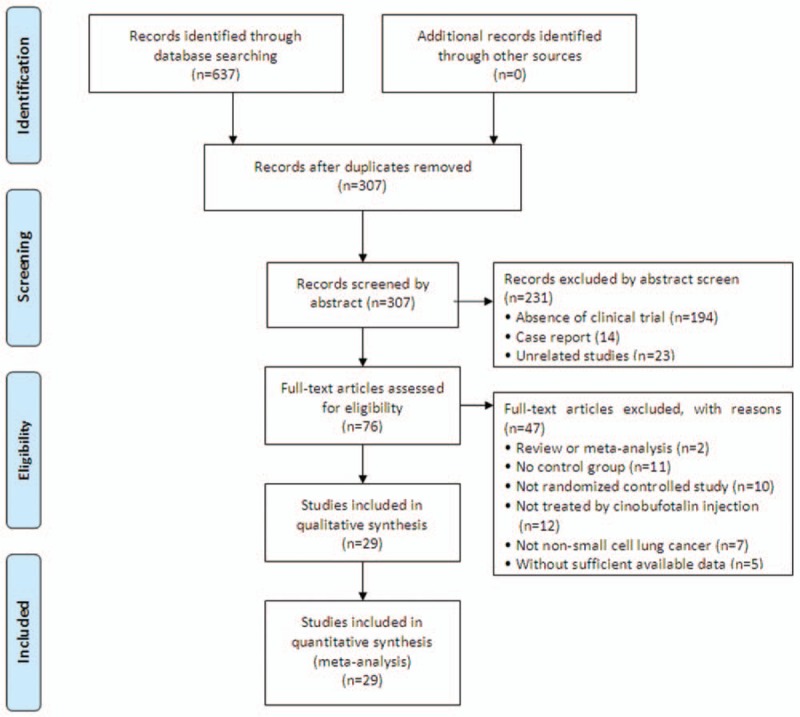

Our retrieve gathered a total of 637 articles initially, and 561 articles were ruled out because they did not including clinical trials (n = 194) or were case report (n = 14), unrelated studies (n = 23) or repetition (n = 330), leaving 76 studies as potentially relevant. Further detailed assessment of full texts screened out reviews or meta-analysis (n = 2), articles without control groups (n = 11), trials that were not randomized controlled (n = 10) or did not included CFI and chemo-combined therapy (n = 12), patients were not NSCLC (n = 7) and studies with insufficient data (n = 5). Finally, 29 trials[15–17,21–46] involving 2300 advanced NSCLC patients were included in this meta-analysis (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the selection process.

3.2. Patient characteristics

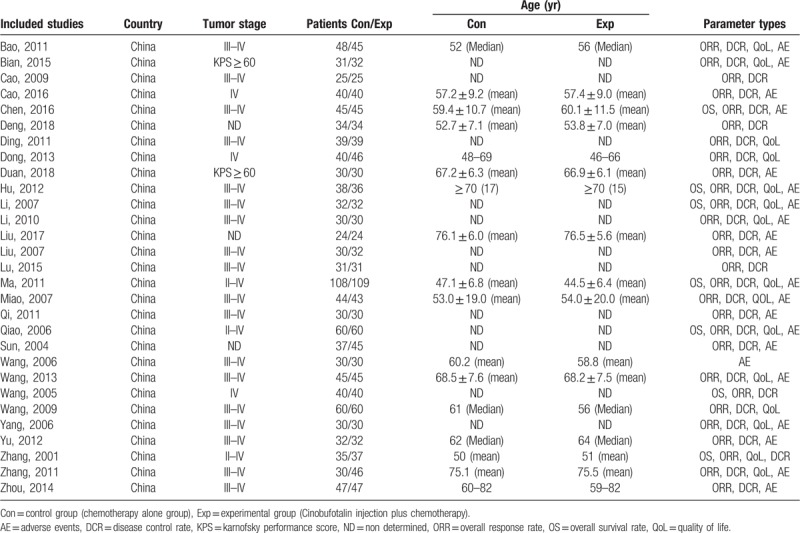

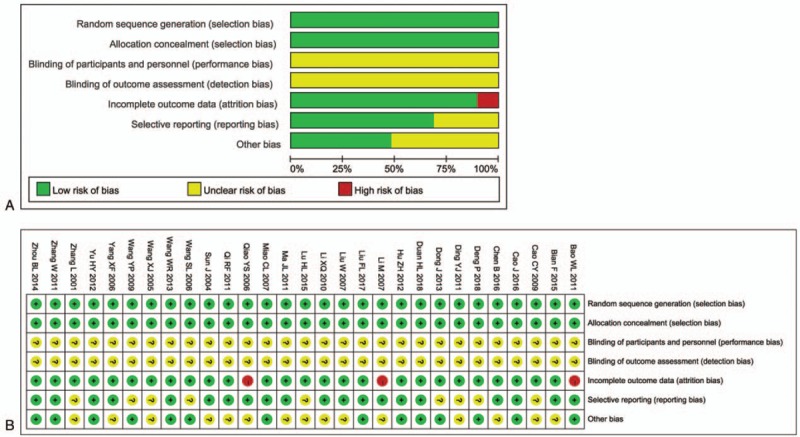

All studies involved in this analysis contained RCT carried out in China since 2000. These trials include 2300 patients with advanced NSCLC, among which 1164 were treated by CFI and chemo-combined therapy, and 1136 were treated by chemotherapy alone. Tables 1 and 2 represent details of the involved trials and patients.

Table 1.

Clinical information from the eligible trials in the meta-analysis.

Table 2.

Information of cinobufotalin injection combined with chemotherapy.

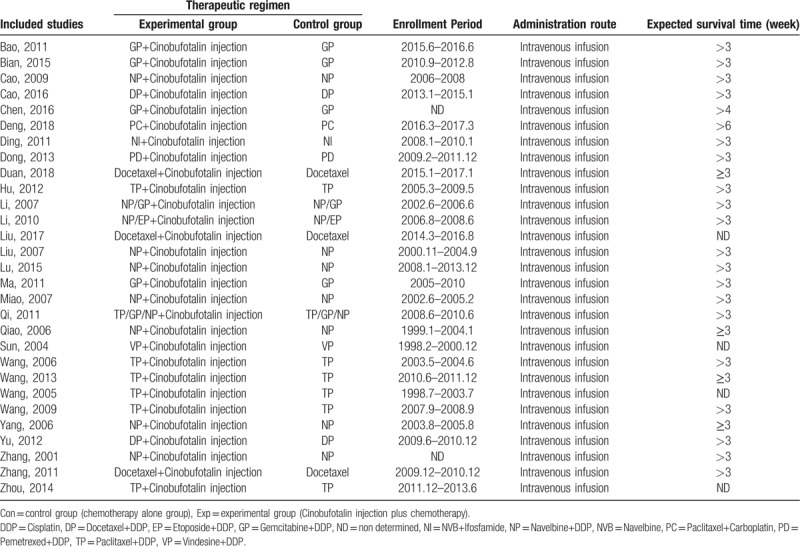

3.3. Quality assessment

All involved trials were subjected to risk assessment of bias. It turns out all trials were randomly controlled with low selection risk, but performance and detection risks were not able to be assessed as relevant information were not shown in the publications (Fig. 2). Among all the included clinical studies, 3 trials[21,28,35] were regarded as high attrition risk owing to absent of follow-up data and 9 studies[22,24–26,32,37,39,40,44] were considered as unclear reporting risk due to lack of efficacy and safety assessment (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

(A) Risk of bias summary: review of authors’ judgments about each risk of bias item for included studies. (B) Risk of bias graph: review of authors’ judgments about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies. Note: Each color represents a different level of bias: red for high-risk, green for low-risk, and yellow for unclear-risk of bias.

3.4. Therapeutic efficacy assessments

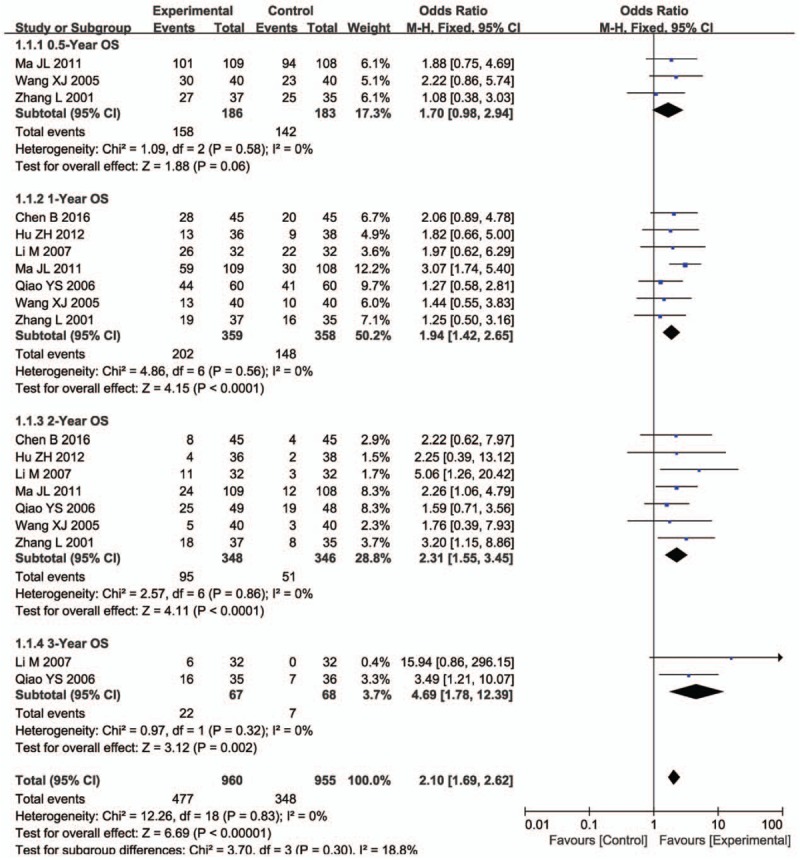

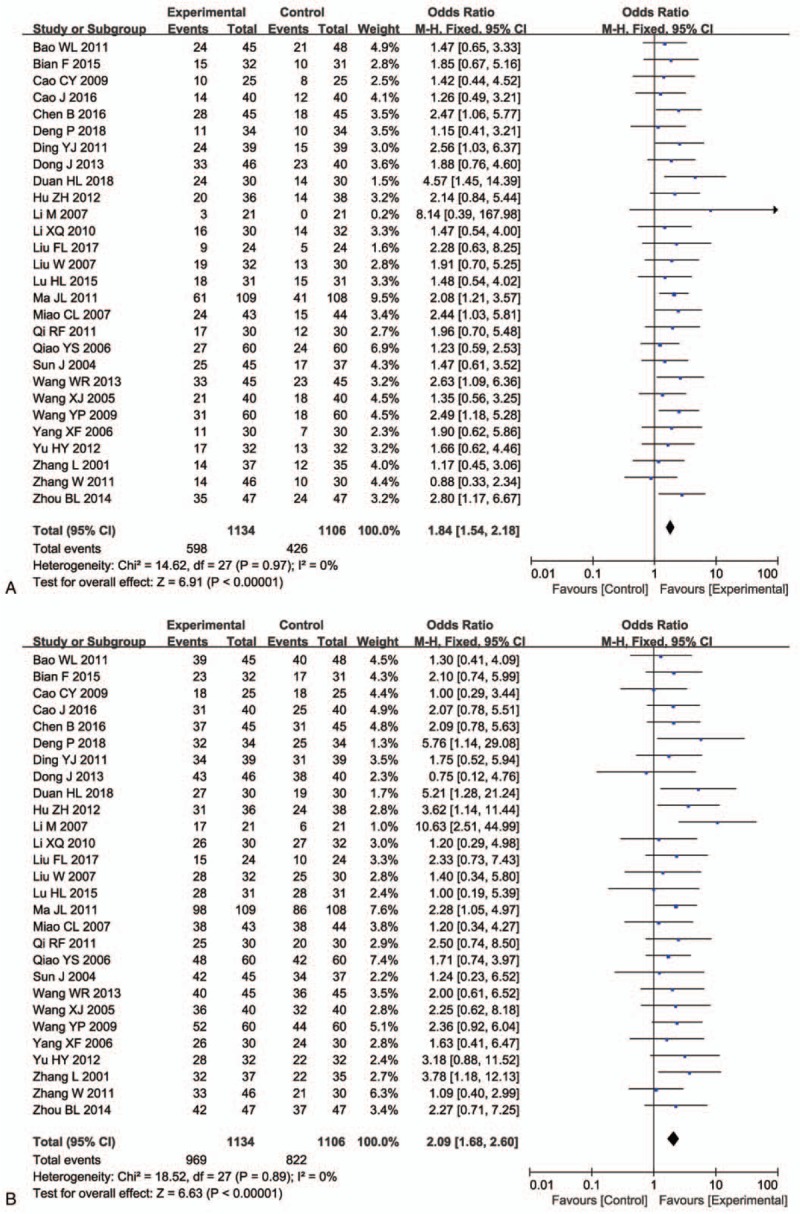

Pooled analysis on treatment effects showed 1-, 2- and 3-year OS of combined therapy treated patients were greatly improved (1-year OS, OR = 1.94, 95% CI = 1.42–2.65, P < .0001; 2- year OS, OR = 2.31, 95% CI = 1.55–3.45, P < .0001; 3-year OS, OR = 4.69, 95% CI = 1.78–12.39, P = .002), CR (OR = 2.01, 95% CI = 1.47–2.75, P < .0001), PR (OR = 1.51, 95% CI = 1.26–1.80, P < .00001), ORR (OR = 1.84, 95% CI = 1.54–2.18, P < .00001) and DCR (OR = 2.09, 95% CI = 1.68–2.60, P < .00001) and significantly decreased PD (OR = 0.47, 95% CI = 0.38–0.59, P < .00001), whereas the 0.5-year OS (OR = 1.70, 95% CI = 0.98–2.94, P = .06) and SD (OR = 0.87, 95% CI = 0.73–1.03, P = .11) did not show significant difference from patients who received chemotherapy alone (Figs. 3 and 4, Supplementary Figure 1 and Table 3). The analysis of OR rate was conducted with fixed-effect models because of low heterogeneity.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the comparison of overall survival (OS) between the experimental and control group. Control group, chemotherapy alone group; Experimental group, Cinobufotalin injection plus chemotherapy. The fixed-effects meta-analysis model (Mantel–Haenszel method) was used.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of the comparison of overall response rate (ORR, A) and disease control rate (DCR, B) between the experimental and control group. Control group, chemotherapy alone group; Experimental group, Cinobufotalin injection plus chemotherapy. The fixed-effects meta-analysis model (Mantel–Haenszel method) was used.

Table 3.

Comparison of CR, PR, SD, PD, ORR, and DCR between the experimental and control groups.

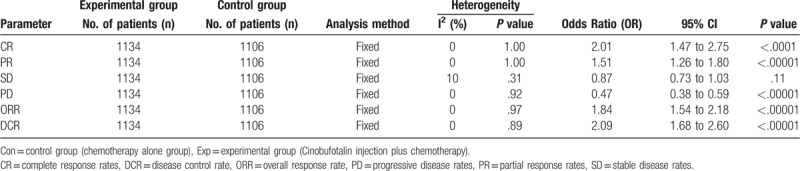

3.5. QoL assessment

The QoL evaluation demonstrated that CFI and chemo-combined therapy-treated patients had improved QoL than those treated solely by chemotherapy, according to QIR (Fig. 5A, OR = 2.64, 95% CI = 1.98–3.52, P < .00001) and KPS (Fig. 5B, OR = 10.97, 95% CI = 5.48–16.47, P < .0001).

Figure 5.

Forest plot of the comparison of quality of life improved rate (QIR, A) and karnofsky performance score (KPS, B) between the experimental and control group. Control group, chemotherapy alone group; Experimental group, Cinobufotalin injection plus chemotherapy.

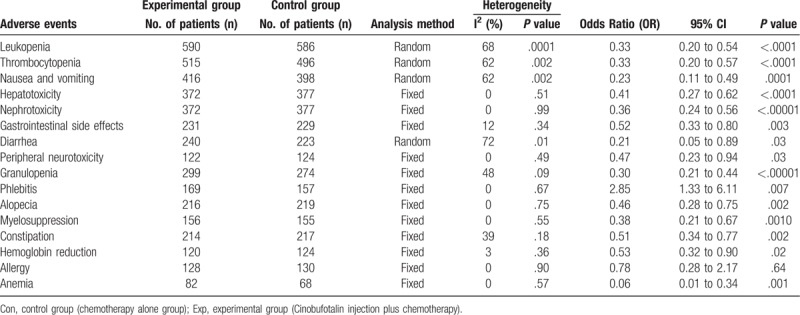

3.6. Adverse events assessment

As shown in Table 4 and Supplementary Figure 2, patients treated by CFI and chemo-combined therapy displayed lower incidences of leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, nausea and vomiting, hepatotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, gastrointestinal side effects, diarrhea, peripheral neurotoxicity, granulopenia, alopecia, myelosuppression, constipation, hemoglobin reduction and anemia (leukopenia: OR = 0.33, 95% CI = 0.20–0.54, P < .0001; thrombocytopenia: OR = 0.33, 95% CI = 0.20–0.57, P < .0001; nausea and vomiting: OR = 0.23, 95% CI = 0.11–0.49, P = .0001; hepatotoxicity: OR = 0.41, 95% CI = 0.27–0.62, P < .0001; nephrotoxicity: OR = 0.36, 95% CI = 0.24–0.56, P < .00001; gastrointestinal side effects: OR = 0.52, 95% CI = 0.33–0.80, P = .003; diarrhea: OR = 0.21, 95% CI = 0.05–0.89, P = .03; peripheral neurotoxicity: OR = 0.47, 95% CI = 0.23–0.94, P = .03; granulopenia: OR = 0.30, 95% CI = 0.21–0.44, P < .00001; alopecia: OR = 0.46, 95% CI = 0.28–0.75, P = .002; myelosuppression: OR = 0.38, 95% CI = 0.21–0.67, P = .0010; constipation: OR = 0.51, 95% CI = 0.34–0.77, P = .002; hemoglobin reduction: OR = 0.53, 95% CI = 0.32–0.90, P = .02; anemia: OR = .06, 95% CI = 0.01–0.34, P = .001), and higher incidence of phlebitis (OR = 2.85, 95% CI = 1.33–6.11, P = .007), whereas no difference was found in the occurrence of allergy (OR = 0.78, 95% CI = 0.28–2.17, P = .64).

Table 4.

Comparison of adverse events between the experimental and control groups.

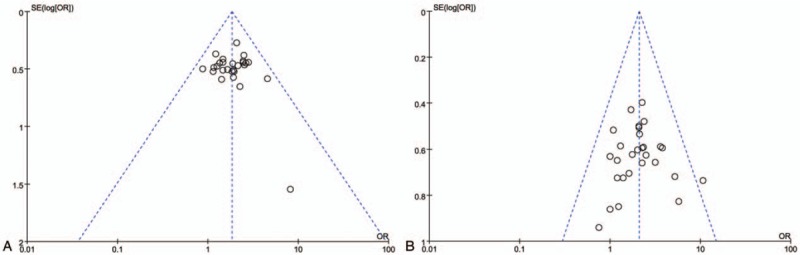

3.7. Publication bias

Publication bias of primary outcomes (CR, PR, SD, PD, ORR, DCR, QIR, and adverse events) were evaluated and presented by funnel plots. All plots were approximately symmetrical, indicating well controlled publication bias and satisfied reliability (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Fig. 3).

Figure 6.

Funnel plot of percentage of overall response rate (ORR, A) and disease control rate (DCR, B).

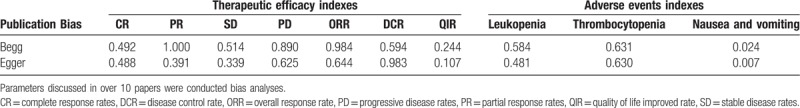

We also assessed publication bias by Begg and Egger regression asymmetry tests, and nausea and vomiting was found with bias (Table 5, Egger: P = .024; Begg: P = .007, P < .05 indicating that there have publication bias in the included studies). To determine if the bias affect the pooled risk, we conducted trim and filled analysis. The adjusted OR indicated same trend with the result of the primary analysis (before: P = 0.00001, after: P = 0.0001), reflecting the reliability of our primary conclusions, except those based on few numbers of trials.

Table 5.

Publication bias on therapeutic efficacy indexes (CR, PR, SD, PD, ORR, DCR, and QIR) and adverse events indexes (Leukopenia, Thrombocytopenia and Nausea and vomiting).

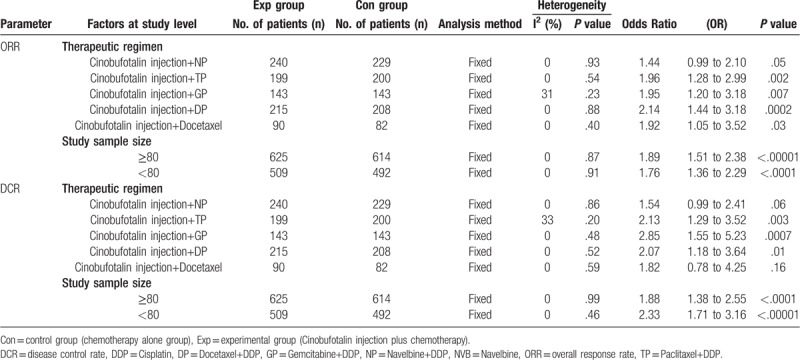

3.8. Sensitivity analysis

Subgroup analysis was performed for ORR and DCR heterogeneity assessment concerning therapeutic regimens and sample sizes of involved trials. No difference with statistical significance was observed on sample sizes of different studies (Table 6). Moreover, CFI combined with TP/GP/DP chemotherapy regimens was found more effective for NSCLC treatment.

Table 6.

Subgroup analyses of ORR and DCR between the experimental and control group.

We also conducted meta-regression analysis for detecting the impact of independent variables: therapeutic regimens and sample sizes, and the primary results were consistent with the subgroup analysis (Supplement Table 2).

4. Discussion

In the common treatment of NSCLC, chemotherapy bears serious side effects such as myelosuppression, hepatotoxicity, nephrotoxicity and gastrointestinal side effects, which severely affected the normal life of NSCLC patients.[47,48] Clinicians have been exploring complementary and alternative medicine treatments for advanced NSCLC, and traditional Chinese medicine, particularly cinobufotalin, has been clinically applied as an adjuvant therapy for decades.[8,9] CFI has been reported beneficial to patients with advanced NSCLC in several trials.[15–17] Despite the published reviews on clinical trials using cinobufotalin, its therapeutic effects have not been systematically demonstrated. These trials had various sample sizes following different protocols, which compounded the difficulties of statistical analysis. To perform a reliable systematic analysis with statistical significance, in this research, we gathered large amounts of data from online databases and conducted comparative analysis in various categorization.

Our meta-analysis revealed that CFI and chemo-combined therapy for NSCLC patients achieved more beneficial effects in comparison with those treated by solely chemotherapy. Combined therapy-treated patients exhibited broadly increased 1 to 3 years OS, CR, PR, ORR, and DCR (P < .05), and also significantly improved QoL. These results indicated that intravenous infusion of CFI improved the curative effects of chemotherapy.

In the evaluation of safety in CFI involved therapy for NSCLC, our analysis showed that most of adverse events caused by chemotherapy were obviously alleviated (P < .05). However, patients received CFI and chemo-combined therapy showed higher incidence of phlebitis, which should be considered before treatment for sensitive groups.

The analysis on therapeutic effects may be influenced by several factors. In our study, no difference was found between sample sizes of trials. Our sensitivity analysis showed that CFI combined with TP/GP/DP chemotherapy was more effective for NSCLC treatment. However, but recent studies on the impact of this factor on the curative effect of CFI mediated therapy remain insufficient and further investigations still should be performed.

There are some limitations in our analysis. Firstly, as a traditional medicine, cinobufotalin was mainly applied in China, which comes with unavoidable regional bias and subsequently has an effect on CFI's widely application out of China. Secondly, since researchers in different clinical studies reported various outcomes, categorization was complicated and making it difficult to summarize the results at the same scale. Moreover, the efficacy of CFI therapy might be related with NSCLC subtypes. However, our data were extracted from publications where this information was not sufficiently provided. Therefore, based on currently available literature, there are insufficient data to perform a statistical analysis to evaluate the correlation. We will keep paying close attention to this concern in our later studies. Finally, as the sources of our data were published articles instead of raw records of clinical trials, analytical bias would be possibly existed. Therefore, more original data would be valuable to achieve a higher reliability of statistical analysis on CFI involved NSCLC treatment.

5. Conclusion

This meta-analysis indicated that CFI and chemo-combined therapy was effective in treating advanced NSCLC. Intravenous infusion of CFI not only greatly improved the therapeutic effects of chemotherapy, but also effectively alleviates the toxicity and most of side effects caused by chemotherapy. Considering the possibility of causing phlebitis, clinician should weigh and consider balance of using CFI for sensitive NSCLC patients. On the other hand, fighting cancer war is a long term task. Therefore, it is necessary to further investigate the cancer mechanism and synthesis of anti-cancer natural medicines.[49–52]

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Fan Zhang, Tiantian Xu.

Data curation: Fan Zhang.

Formal analysis: Fan Zhang, Yantong Yin.

Investigation: Fan Zhang, Yantong Yin.

Methodology: Fan Zhang, Yantong Yin.

Project administration: Tiantian Xu.

Software: Fan Zhang.

Supervision: Tiantian Xu.

Validation: Fan Zhang, Yantong Yin, Tiantian Xu.

Visualization: Fan Zhang, Yantong Yin.

Writing – original draft: Fan Zhang, Yantong Yin.

Writing – review & editing: Tiantian Xu.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CBM = Chinese Biological Medicine Database, CFI = Cinobufotalin injection, CMCI = Chinese Medical Citation Index, CNKI = China National Knowledge Infrastructure, CR = complete response rates, DCR = disease control rate, KPS = karnofsky performance score, NSCLC = advanced non-small cell lung cancer, OR = odds ratio, ORR = overall response rate, OS = overall survival, PD = progressive disease rates, PR = partial response rates, QIR = quality of life improved rate, QoL = quality of life, RCT = randomized controlled trials, ROS = reactive oxygen species, SD = stable disease rates, VIP = Chinese Scientific Journal Database, CI = confidence interval.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article.

References

- [1].Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Wang L, Huang M, Ding H, et al. Genetically determined height was associated with lung cancer risk in East Asian population. Cancer Med 2018;7:3445–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin 2016;66:115–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Xu X, Huang Z, Zheng L, et al. The efficacy and safety of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies combined with chemotherapy or CTLA4 antibody as a first-line treatment for advanced lung cancer. Int J Cancer 2018;142:2344–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Yan BD, Cong XF, Zhao SS, et al. Efficacy and safety of antigen-specific immunotherapy in the treatment of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Cancer Drug Targets 2018;19:199–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Zhou C, Liu D, Li J, et al. Chemotherapy plus dendritic cells co-cultured with cytokine-induced killer cells versus chemotherapy alone to treat advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: A meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2016;7:86500–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Meng Z, Yang P, Shen Y, et al. Pilot study of huachansu in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, nonsmall-cell lung cancer, or pancreatic cancer. Cancer 2009;115:5309–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Chen YZ, Feng XB, Li ZD, et al. Clinical study on long-term overall survival of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with Chinese medicine and Western medicine. Chin J Integr Med 2014;20:179–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Jiang Y, Liu LS, Shen LP, et al. Traditional Chinese Medicine treatment as maintenance therapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Med 2016;24:55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kai S, Lu JH, Hui PP, et al. Pre-clinical evaluation of cinobufotalin as a potential anti-lung cancer agent. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2014;452:768–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Emam H, Zhao QL, Furusawa Y, et al. Apoptotic cell death by the novel natural compound, cinobufotalin. Chem Biol Interact 2012;199:154–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Chen KK, Anderson RC, Henderson FG. Comparison of cardiac action of bufalin, cinobufotalin, and telocinobufagin with cinobufagin. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1951;76:372–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Shi Z, Song T, Wan Y, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of traditional insect Chinese medicines combined chemotherapy for non-surgical hepatocellular carcinoma therapy. Sci Rep 2017;7:4355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Cheng L, Chen YZ, Peng Y, et al. Ceramide production mediates cinobufotalin-induced growth inhibition and apoptosis in cultured hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Tumour Biol 2015;36:5763–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Bian F, Wang Y, Liu Y, et al. The clinical observation of cinobufotalin injection in combination with GP chemotherapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Shandong Med J 2015;55:75–6. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Chen B. Clinical efficacy and anti-tumor mechanism of cinobufacini combined with GP regimen for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Pract J Cancer 2016;31:224–7. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hu ZH. Clinical observation of cinobufacini injection combined with TP regimen for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. China Pharm 2012;23:1507–10. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Zeng X, Zhang Y, Kwong JS, et al. The methodological quality assessment tools for preclinical and clinical studies, systematic review and meta-analysis, and clinical practice guideline: a systematic review. J Evid Based Med 2015;8:2–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Jackson D, White IR, Riley RD. Quantifying the impact of between-study heterogeneity in multivariate meta-analyses. Stat Med 2012;31:3805–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Zhang L, Mu Y, Zhang A, et al. Cytokine-induced killer cells/dendritic cells-cytokine induced killer cells immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy for treatment of colorectal cancer in China: a meta-analysis of 29 trials involving 2,610 patients. Oncotarget 2017;8:45164–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bao WL, Zhang YJ, Sun Y. The clinical study of cinobufotalin injection combined with chemotherapy for the treatment of advanced lung cancer. Zhejiang J Tradit Chin Med 2011;46:478–9. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Cao CY. The clinical study of cinobufotalin injection in combination with NP chemotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer. T J Med Theory Pract 2009;22:935–6. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Cao J, Zhou J, Yang D, et al. Clinical curative effect on non-small cell lung cancer patients by cinobufacini injection combined first-line chemotherapy. J Int Oncol 2016;43:741–3. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Deng P. Effect of cinobufotalin injection combined with PC chemotherapy on serum level of CA125 and CEA in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J North Pharm 2018;15:108–9. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ding YJ. Clinical observation of cinobufotalin injection in combination with NI chemotherapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Shandong Med J 2011;51:76–7. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Dong J. The clinical observation of cinobufotalin injection in combination with PD chemotherapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Chin J Trad Med Sci Tech 2013;20:304. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Duan HL, Li XS, Gao JJ, et al. Clinical efficacy of cinobufacini injection combined with docetaxel in elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Res Pract 2018;6:20–1. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Li M, Xu C, Liu X. Clinical observation of Hua Chan Su injection in the adjuvant therapy for 64 patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Tumor 2007;27:666–8. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Li XQ, Bao YC, Zhang HY. Clinical research of combined huachansu injection with chemotherapy on advanced non-small cell luns cancer. J Modern Oncol 2009;17:60–1. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Liu FL. Clinical study of cinobufacini Injection combined with docetaxel chemotherapy in the treatment of elderly patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. China Cotu Med Edu 2017;8:164–5. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Liu W, Sun PM, Zhang PJ. The clinical observation of cinobufotalin in combination with chemotherapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Chin J Clin Oncol Rehab 2007;14:463–4. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Lu HL, Lu HX. Clinical efficacy of cinobufotalin in combination with chemotherapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Chin Remed Clin 2015;15:1609–10. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Ma JL, Lu M. Clinical research on 109 cases of non-small cell lung cancer treated by cinobutacini injection plus gemcitabine and cisplatin. J Trad Chin Med 2011;52:2115–8. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Miao CL, Yu QF, Liang HF. The clinical observation of cinobufotalin injection in combination with chemotherapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Chin J Integr Trad West Med 2007;27:657–8. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Qiao YS, Wang M, Li GY. 60 cases patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated by cinobufotalin injection combined with chemotherapy. Shandong Med J 2006;46:47–8. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Sun J, Sheng ZJ. 45 cases patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated by cinobufotalin. Trad Chin Med Res 2002;15:38–9. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Wang SL. Analysis on the effect of cinobufotalin in combination with chemotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer. Central Plains Med J 2006;33:70. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Wang WR, Hong B, Li K. Evaluation of cinobutacini injection in the adjuvant treatment of patients with advanced no-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Pulmonary Med 2013;18:203–4. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Wang XJ. The clinical observation of the chemotherapy program with cinobufacini associated with cisplatin and paclitaxel in treating 40 cases with advanced lung cancer. Henan J Oncol 2005;18:343–4. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Wang YP, Shu JH. Therapeutics effect observation of bufonin injection combined with chemotherapeutics on the primary NSCLC. Tumour J World 2009;8:183–90. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Yang XF, Xi J. Observation on the effectiveness of cinobufotalin and chemotherapy in the treatment of patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Herald Med 2006;25:1287–8. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Yu HY, Gao SY, Hao YX. Study of huanchansu injection combined with TP regimen in the treatment of patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Pract J Cancer 2012;27:55–7. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Qi RF, Zhang H. Clinical observation of cinobufotalin adjuvant therapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Chin Foreign Health Abstr 2011;8:80–2. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Zhang L, Liu CL, Jin XJ, et al. Evaluation and analysis of the quality of life in patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated by cinobufacini and NP regimen. Modern Rehab 2001;5:113. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Zhang W, Huang CJ, Huang HB, et al. Clinical observation of cinobufotalin combined with docetaxel on advanced non-small cell lung cancer in the elderly. J Clin Med Pract 2011;15:95–7. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Zhou BL. Efficacy evaluation of cinobufotalin injection adjuvant treatment for advanced NSCLC. Med Health Care 2014;22:79. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Ai D, Guan Y, Liu XJ, et al. Clinical comparative investigation of efficacy and toxicity of cisplatin plus gemcitabine or plus Abraxane as first-line chemotherapy for stage III/IV non-small-cell lung cancer. Onco Targets ther 2016;9:5693–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Yang ZY, Liu L, Mao C, et al. Chemotherapy with cetuximab versus chemotherapy alone for chemotherapy-naive advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;11:CD009948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Kou Y, Koag MC, Lee S. N7 methylation alters hydrogen-bonding patterns of guanine in duplex DNA. J Am Chem Soc 2015;137:14067–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Kou Y, Koag MC, Cheun Y, et al. Application of hypoiodite-mediated aminyl radical cyclization to synthesis of solasodine acetate. Steroids 2012;77:1069–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Kou Y, Lee S. Unexpected opening of steroidal E-ring during hypoiodite-mediated oxidation. Tetrahedr Lett 2013;54:4106–9. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Kou Y, Koag MC, Lee S. Structural and kinetic studies of the effect of guanine N7 alkylation and metal cofactors on DNA replication. Biochemistry 2018;57:5105–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.