Abstract

Stakeholder participation is relevant in strengthening priority setting processes for health worldwide, since it allows for inclusion of alternative perspectives and values that can enhance the fairness, legitimacy and acceptability of decisions. Low-income countries operating within decentralized systems recognize the role played by sub-national administrative levels (such as districts) in healthcare priority setting. In Uganda, decentralization is a vehicle for facilitating stakeholder participation. Our objective was to examine district-level decision-makers’ perspectives on the participation of different stakeholders, including challenges related to their participation. We further sought to understand the leverages that allow these stakeholders to influence priority setting processes. We used an interpretive description methodology involving qualitative interviews. A total of 27 district-level decision-makers from three districts in Uganda were interviewed. Respondents identified the following stakeholder groups: politicians, technical experts, donors, non-governmental organizations (NGO)/civil society organizations (CSO), cultural and traditional leaders, and the public. Politicians, technical experts and donors are the principal contributors to district-level priority setting and the public is largely excluded. The main leverages for politicians were control over the district budget and support of their electorate. Expertise was a cross-cutting leverage for technical experts, donors and NGO/CSOs, while financial and technical resources were leverages for donors and NGO/CSOs. Cultural and traditional leaders’ leverages were cultural knowledge and influence over their followers. The public’s leverage was indirect and exerted through electoral power. Respondents made no mention of participation for vulnerable groups. The public, particularly vulnerable groups, are left out of the priority setting process for health at the district. Conflicting priorities, interests and values are the main challenges facing stakeholders engaged in district-level priority setting. Our findings have important implications for understanding how different stakeholder groups shape the prioritization process and whether representation can be an effective mechanism for participation in health-system priority setting.

Keywords: Stakeholder participation, priority setting, low-income countries (LICs), Uganda

Key Messages

There is support for stakeholder participation in priority setting for health; however, most of the literature has omitted in-depth analysis of stakeholders’ roles, their leverages and the challenges with their participation in prioritization processes.

We found that politicians, technical experts and donors are the principal contributors to district-level priority setting in Uganda, and the public is largely excluded from the process.

Decentralization in Uganda is meant to facilitate stakeholder participation in governmental decision-making, however, it seems to be giving more power and legitimacy to politicians—as representatives of the public—rather than to the public itself.

Stakeholders’ different types of leverage affect their ability to influence the priority setting process. Stakeholders who have a weak direct influence may in fact have strong leverages that act indirectly to influence those directly engaged in priority setting.

Background

In setting priorities for health systems, it is critical that the people who stand to gain or lose from the decisions that are made (stakeholders) are involved in the prioritization process (Sibbald et al., 2009; Shayo et al., 2013). Priority setting for health systems involves making decisions about how resources are allocated between different and, at times, competing health programmes and interventions (Kapiriri and Razavi, 2017). Meaningful stakeholder participation in priority setting processes is thought to lead to legitimate and more acceptable policy decisions that reflect the interests of those involved (Martin et al., 2002; Kapiriri et al., 2003; Bruni et al., 2008). In the health sector, stakeholder participation is also thought to foster shared learning about the need to set limits on what can and cannot be funded (Daniels and Sabin, 2008). This article contributes to the priority setting literature by exploring the role and influence of different types of stakeholders in sub-national level (district) health-system priority setting in low-income countries (LICs).

Wide stakeholder involvement is thought to facilitate representation of, and increase the potential for including a range of relevant values and principles the prioritization process (Maluka, 2011). In turn, this involvement is believed to enhance fair priority setting (Martin et al., 2002), acceptability and applicability of the decisions (Bruni et al., 2008; Mitton et al., 2009; Aidem, 2017). In particular, there is a critical need to involve and consider the public as a special stakeholder group whose values should be reflected in the prioritization process, since the public stands to either benefit or lose the most from the priority setting decisions (Bruni et al., 2008; Mitton et al., 2009).

In LICs, the participation of a broad range of stakeholders (including the ‘powerful’, experts and health users) is particularly relevant for strengthening district-level democratic processes, because involving stakeholders allows for the inclusion of alternative perspectives and values. Including all stakeholders also contributes to ensuring that the priority setting process is fair, legitimate and acceptable (Martin et al., 2002; Kapiriri et al., 2003; Bruni et al., 2008).

Decentralization: a tool facilitating stakeholder participation in LICs

In recent years, the role of decentralization in facilitating stakeholder participation in LICs has become more prominent (O’Meara et al., 2011). Decentralization, in its various forms (e.g. devolution, deconcentration, delegation and privatization), involves a shift of power within the formal institutional structures (Mills, 1994; Mogedal et al., 1995; Jeppsson and Okuonzi, 2000). Widespread decentralization of governments and subsequent decentralization of responsibilities for social services such as healthcare have led to the promotion of public participation to enhance transparency and inclusiveness (Bolsewicz Alderman et al., 2013). In fact, as a result of implementing the decentralized framework, public participation in health-sector priority setting has been mandated at sub-national levels in many LICs, including Uganda, Tanzania, Kenya, Indonesia, India, Philippines, among others (Kapiriri et al., 2003; Bolsewicz Alderman et al., 2013; Shayo et al., 2013). For example, decentralization across all sectors in Uganda involved devolution, whereby decision-making powers were redistributed from the central government to lower levels of government, namely districts (Mills, 1994; Gilson and Mills, 1995; Jeppsson and Okuonzi, 2000; Kapiriri et al., 2003). Decentralization is thought to have resulted in local-level autonomy in decision-making, policy implementation, and the allocation of resources received from the national level. Decentralization of responsibilities for social services, including healthcare, is believed to have enhanced transparency and inclusiveness, and to have fostered stakeholder (particularly public) participation in decision-making and priority setting for the health sector (Kapiriri et al., 2003; Bolsewicz Alderman et al., 2013).

Challenges with stakeholder participation

While stakeholder participation in policy-related decision-making is believed to enhance the legitimacy, acceptability and stakeholder satisfaction with the outcomes, it also has challenges. First, sustained inclusion and participation of a wide range of stakeholders can be time-consuming and cost prohibitive (Martin et al., 2002; Mitton and Donaldson, 2004). Second, meaningful participation may be inhibited by limited expertise of some of the stakeholders—especially the public (Charles and DeMaio, 1993; Rowe and Frewer, 2000; Maluka et al., 2010). Third, different stakeholders may have different values and needs that require balancing (Charles and DeMaio, 1993; Kapiriri and Norheim, 2004; Kapiriri et al., 2004). However, balancing these values may be challenging since the most powerful and influential stakeholders often push their values using the resources they have through their political and/or financial influence. This challenge of balancing different stakeholder values is especially relevant in LICs. In low-income settings, the role of donors as the funding agencies, and their subsequent influence on priority setting in LICs is particularly strong (Glassman and Chalkidou, 2012; Kapiriri, 2012; Shayo et al., 2013; Hipgrave et al., 2014; Colenbrander et al., 2015). This is especially the case at the province or district levels where the influence of donors and other political stakeholders may overshadow that of ‘lower-ranked’ stakeholders (Hipgrave et al., 2014).

Knowledge gaps

Despite the growing body of literature on priority setting in LIC health systems, several key gaps remain: in-depth examination of different stakeholders’ specific roles; and discussion of the power and points of leverages that allow stakeholders to shape priority setting. The priority setting literature often identifies similar sets of stakeholders who are routinely engaged in prioritization processes, among them politicians, government officials, technical experts and health professionals, health administrators and health managers, and patients and the public (Kapiriri et al., 2003; Bolsewicz Alderman et al., 2013; Shayo et al., 2013). Similarly, the meagre literature on stakeholder participation in priority setting in LICs identifies the main stakeholders as health management officials, governmental officials, healthcare providers, administrators and donors (Kapiriri et al., 2003; Bolsewicz Alderman et al., 2013; Shayo et al., 2013). While some of the literature briefly mentions the roles of stakeholders (Martin et al., 2002; Kapiriri et al., 2003; Gibson et al., 2004; Mitton et al., 2009; Regier et al., 2014), they are not often discussed in depth. Rather than expanding on the participation of each type of stakeholder, their participation as a group is typically contrasted with other groups that are involved in priority setting processes.

Moreover, while existing literature discussed district-level priority setting and identified relevant stakeholders, the stakeholders’ power and influence (i.e. leverages), how these factors shape prioritization processes and outcomes, and the related challenges, are rarely discussed. To date, most of the literature that analyses stakeholders’ participation in priority setting for LICs has focused on the national level. The critical role that districts play in the overall prioritization and implementation of health interventions necessitates that a similar critical analysis be conducted to assess the contributions, influences and challenges attributed to the participation of the various stakeholders in district-level priority setting.

Our study addresses these critical knowledge gaps by identifying and exploring the specific roles of stakeholders in priority setting and their leverage within these processes in three Ugandan districts. Specifically, we (1) examine the perspectives of district-level decision-makers about the participation of different stakeholders in district-level priority setting; (2) identify the stakeholders who are involved in district-level priority setting for health and the roles they play in the three districts; (3) describe and analyse the leverages that the different stakeholders use to influence district-level priority setting; and (4) discuss the challenges associated with the participation of the different stakeholders and make recommendations to alleviate these challenges.

Methods and materials

Study approach

This study used an interpretive description methodology involving qualitative interviews to examine the perspectives of district-level decision-makers about the participation of different stakeholders in district-level priority setting and the challenges related to their participation. Interpretive description is a research methodology that originates in clinical research settings. It borrows from phenomenology, grounded theory and ethnography to become more responsive to practical, experience-based research questions, and it can be applied in contemporary healthcare contexts with implications for applications and practice (Thorne et al. 2004). The methodology is a theoretically driven approach that allows for the use of organizing frameworks to analyse data and explore the phenomenon of interest (Thorne, 2016). The researcher uses both inductive reasoning and deductive techniques to answer research questions. The aim is not to discover a new theory, as is done in grounded theory, but to allow for themes and patterns to emerge, and also to identify variations in themes as a way of generating a coherent, conceptual understanding of application-based research questions or phenomena (Thorne et al. 2004). Interpretive description is well-suited to understanding the phenomenon of stakeholder participation in health-systems priority setting and the implications of this participation for future policy-making.

Study context

Study settings

The study was conducted from 2014 to 2016 in three districts of Uganda. Uganda provides a relevant case to study stakeholder participation given its historical commitment to stakeholder participation within its political system. Decentralization in Uganda resulted in the devolution of both political and technical sectors to sub-national levels. To facilitate this division of political power, the country is divided into districts, which are then divided into counties. Counties are divided into sub-counties, which are then divided into parishes and parishes are divided into villages. Within this context, Uganda has mandated representative participation, including a mandate that one-third of the representatives at all administrative levels (parliament, district, sub-county, parish and village councils) are women (Government of Uganda, 1997).

Existing structures for stakeholder participation in district-level priority setting

There are two formal participation structures within the districts: a technical division and a political division (Okello et al., 2015). The political division which governs the district, includes the district council which is elected and is led by the District Chairperson (see Table 1). The technical division is led by the Chief Administrative Officer and is composed of appointed technical individuals who work in the various district departments. Each department is aligned to a sector and has a sectoral committee. For example, the department of health has the health-sectoral committee. The District Health System (DHS) operates within the technical division of the district decision-making structures. The DHS consists of a District Health Team (DHT), which works in collaboration with the extended District Health Management Team (DHMT) and is headed by the District Director of Health Services (Government of Uganda, 1995, 2016; Henriksson et al., 2017). Donors and non-government organizations/civil society organizations (NGO/CSOs) are also technical stakeholders, and they play a role in priority setting in many districts (Kapiriri et al., 2003; Glassman and Chalkidou, 2012; Kapiriri, 2012; Bolsewicz Alderman et al., 2013; Shayo et al., 2013; Colenbrander et al., 2015; Henriksson et al., 2017).

Table 1.

Decision-making structure in Ugandan district

| Committee/council | Members | Role |

|---|---|---|

| Local Council V (District Council) |

|

|

| District Executive Committee |

|

|

| District Technical Planning Committee |

|

|

| Local Council IV (County council) |

|

|

| Local Council III (Sub-county council) |

|

|

| Local Council II (Parish Council) |

|

|

| Local Council I (Village Council) |

|

|

We recognize that district priority setting happens in the broader context of national healthcare priority setting in Uganda (Kapiriri et al., 2007). National priorities may not always align with those of the districts (Kapiriri et al., 2007; Henriksson et al., 2017). Therefore, decision-making space may be limited for stakeholders within local governments since the priorities set at the national level can have trickle-down effects at sub-national level which limit the districts’ ability to set priorities with input from local stakeholders and according to local needs (Kapiriri et al., 2003, 2007; Alonso-Garbayo et al., 2017).

Study sites

The three districts were selected to represent different regions in the country (District A, from the Eastern region; District B, from the Northern region; and District C, from the Central region), as well as the year the district was formed, ranging from old (56 years), intermediate (44 years) and new (13 years) (Table 2).

Table 2.

District demographics table

| District | Region | Year formed | Administrative structure | Estimated population size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Eastern | 1962 |

|

517 082 |

| B | Northern | 1974 |

|

408 043 |

| C | Central | 2005 |

|

328 964 |

Study population, sampling and data collection

Purposive sampling was used to identify prospective interviewees. Initial respondents were members of the District Executive Committee, specifically the secretaries for health, who are identified as the designated decision-makers for health at the district level (Table 1). The District Executive Committee was selected due to its members’ specialized knowledge with regards to how priority setting and decision-making occur within districts. The index respondent in each district was the District Director of Health Services, who then identified the additional respondents they deemed knowledgeable. In each district, we contacted all seven members of the DHT. In District A, the DHT members identified additional respondents, namely, members of the extended DHMT and District Executive Committee, who they thought were key to decision-making within their district.

Interviews were conducted by two trained Ugandan research assistants using a pilot-tested semi-structured interview guide. The interview guide included questions about the health priorities in the region and details of the prioritization process (e.g. who is involved and the roles they play, factors that influence the process, whether the decisions are publicized, whether the priorities are implemented, and the priority setting challenges). All interviews were conducted in English, audio recorded (with permission from the respondents), and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

Analytical framework

Elster’s (1994) framework was applied iteratively to analyse the study data. The framework categorizes stakeholders (actors) involved in priority setting according to the level of decision-making at which they participate. It further provides four dimensions related to stakeholder participation (see Table 3). Stakeholders, as participants in the priority setting, have roles (functions that they play in the process). Furthermore, stakeholders have concerns that are shaped by their interest in the prioritization process and its outcomes. Different stakeholders embody characteristics that empower and enable them to influence the prioritization process and its outcomes.

Table 3.

Elster framework definitions

| Dimension | Definition |

|---|---|

| Actor | A participant in the priority setting (PS) process. |

| Rolea | The function that is played by an actor in the PS process. |

| Perceived concerns | A matter of interest or importance to the identified stakeholder as perceived by the study respondents. |

| Leveragea | Influence or power that is used to achieve a desired result. |

| Perceived challengesa,b | Problems or difficulties stemming from the participation of stakeholders in PS as perceived by the study respondents. |

Dimension included in our analysis.

Added dimension.

This study examines stakeholder participation based on the stakeholder roles and leverages in Elster’s framework. Elster’s concerns dimension was excluded, since this information was not emphasized in our interviews and also because we found some overlap in respondents’ perspectives about concerns and roles, and about concerns and leverages. However, since participation of different stakeholders also presents challenges (Kapiriri et al., 2003; Kapiriri, 2012; Meetoo, 2013; Shayo et al., 2013; Hipgrave et al., 2014; Regier et al., 2014), we added a new dimension—challenges—to the original Elster framework prior to the analysis. The added challenges dimension explains the problems or difficulties stemming from the participation of stakeholders in priority setting as perceived by the other respondents.

Coding

Interview data were entered into NVIVO-10. A member of the research team read through the initial transcripts to identify texts, which were given code labels. At an abstract level, related codes were grouped together under overarching categories. Related categories were grouped together into broader themes, which contributed to our understanding of priority setting within the districts. The identified themes included: description of the priority setting processes, criteria used in determining priorities, use of evidence, legitimacy, challenges to the implementation of priorities and stakeholder engagement. For the purposes of this study, we expanded on the stakeholder engagement theme. Based on the study objectives, we focused on understanding district-level decision-makers’ perspectives about stakeholder participation in priority setting. Detailed analysis involved applying Elster’s framework to the data to specify the different dimensions of stakeholder participation as outlined by the district-level decision-makers. The broad theme of stakeholder participation was further broken down into sub-themes in accordance with the analytical framework. These included: stakeholders, and the roles, leverages and challenges related to their participation.

Ethics

The study was reviewed by the McMaster University REB as well as the Makerere School of Public Health IRB. All respondents signed a written consent form before participating in the interview.

Results

We interviewed a total of 27 respondents from three districts (District A–15, District B–5, District C–7). Most of our respondents were members of the DHT [e.g. District Director(s) of Health Services, Assistant District Health Officers (ADHO), Chief Administrative Officer(s) (CAO), Health Committee Chairperson(s), district planners, secretaries for health and public health nurses]; depending on the district, respondents also included a small number of individuals from other departments (e.g. labour office, biostatistics, engineering, population, health management and information technology systems). With a minimum of five out of seven representatives of the DHT, we had a fair representation of both technical and non-technical decision-makers.

Respondents identified the following stakeholders as being engaged in priority setting processes: politicians, technical experts, donors, NGO/CSOs, cultural and traditional leaders and the general public (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Description of stakeholder categories

| Stakeholder | Description |

|---|---|

| Politicians |

|

| Technical experts |

|

| Donors |

|

| Non-governmental organizations (NGOs)/Civil society organizations (CSOs)a |

|

| Cultural and traditional leaders |

|

| Public |

|

The respondents did not make a distinction between NGOs and civil society organizations, discussing both types of organizations under the ‘NGO’ label.

For each category of stakeholder, we apply the modified version of Elster’s analytic framework to present the roles, leverages and challenges related to their participation as reported by respondents.

Stakeholder roles

Table 5 presents the reported roles played by the different stakeholders in district-level priority setting supported by illustrative quotes. The roles included politicians as decision-makers, technical experts as evidence producers and synthesizers, donors as funders of priorities, NGO/CSOs as implementing partners, cultural and traditional leaders as cultural knowledge experts, and the public as the primary beneficiaries of health services. While we delineate the roles of the different stakeholders, the interviews revealed overlapping roles between stakeholders. For example, providing evidence and expertise are roles that technical experts, donors and (to a lesser extent) NGO/CSOs share, while local government, donors and NGO/CSOs were identified as playing a role in funding and implementing priorities.

Table 5.

Stakeholders’ roles in district-level decision-making

| Stakeholder | Role | Illustrative quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Politicians |

|

|

| District technical experts |

|

|

| Donors |

|

|

| NGO/CSOs | Support the implementation of programmes and initiatives |

|

| Cultural and traditional leaders |

|

|

| Public/community | Beneficiaries of health services |

|

This overlapping of the roles of the different stakeholders may lead to conflicts. When roles are clearly defined there is the potential to reduce conflict between the stakeholders. As explained by one of the technical key informants, explicit specification of roles (e.g. technical experts as consultants and politicians as decision-makers) enhances the priority setting processes. When stakeholders are aware of their role and other stakeholders’ roles in the process, disagreements can be reduced and resolution of emerging disagreements between stakeholders with differing perspectives can be facilitated. For example, a politician from District B stated the following:

In our committees, I must say that we have very good relationships… because it depends on the leadership… we as [Health] committee members have to know our role. We also have to understand where the role of the technical people starts and ends. So, when you’re aware of that you don’t have any conflicts between your committee members. We always (consider) both technical and political (perspectives) and sometimes we disagree. But disagreement, well that is to bring the way forward, then we agreed and say, ‘Yes this is the priority area that we should work on… (Politician, District B).

Some stakeholders were perceived by respondents as more influential than others. Specifically, politicians were viewed as the final decision-makers and, therefore, were perceived to have significant authority in setting district-level priorities.

Stakeholder leverage in the prioritization process

As defined in Table 3, leverage refers to the stakeholders’ ability to influence decision-making processes, either directly or indirectly. Directly, stakeholders participating in the prioritization process can use their leverage to shape the decisions and priorities that are established. Indirectly, stakeholders influence the decisions by exerting pressure on those who directly participate in the decision-making process.

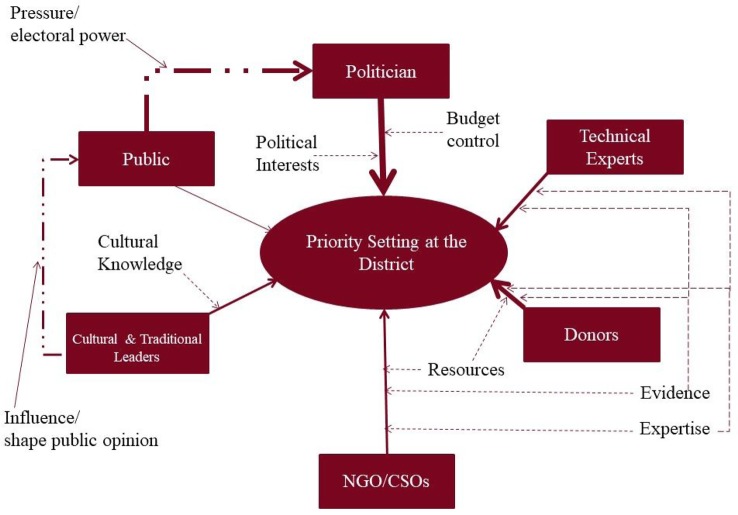

We found that stakeholders such as politicians, technical experts and donors directly influence decisions, while the public and cultural and traditional leaders do so indirectly. While politicians were identified as the ultimate decision-makers with responsibility for budgeting and resource allocation decisions (see Table 5), they can also be influenced by other stakeholders. The public influences politicians, since they elect the politicians to represent their community needs and interests. The public can therefore apply leverage through elections, whereby if they are dissatisfied, they do not re-elect the responsible politician. Thus, the public can pressure politicians to make decisions that are aligned with their needs and goals. Another example of how stakeholders use their leverage indirectly is the case of cultural and traditional leaders and the community. Cultural and traditional leaders are often well-known and respected individuals who hold significant clout with their communities. Their role as leaders allows them to shape public opinion, perspectives and perceptions about health priorities, and they influence community participation and support for government programming. Consequently, cultural and traditional leaders can leverage their unique community and cultural knowledge and guide the priority setting process (Table 6).

Table 6.

Stakeholders’ leverage(s) in district-level decision-making

| Stakeholder | Leverage | Illustrative quote(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Politicians |

|

|

| District technical experts |

|

|

| Donors |

|

At times, we have them as technical advisors. Then at times as they come in with their support [financial and other resources] they also give conditions that we must fulfill. So, it might be a condition, it might be out of sheer giving of technical expertise. So, they definitely play a big role especially in those areas where they’ve got a lot of interest, they play a very big role (Technical expert, District C). |

| NGO/CSOs |

|

|

| Cultural and traditional leaders |

|

The cultural institutions can influence failure or success of any health programme, because they influence attitudes, they have norms (Technical expert, District A). |

| Public/community | Electoral power | We normally, for us politicians mobilize people, especially the counsellors, to gather views from the people they represent. Then also to come into that meeting where we collect the priorities for (Politician, District C). |

Furthermore, we found differences in the perceived ability that stakeholders have for leveraging their influence in priority setting processes. These are demonstrated in Figure 1, whereby the thickness of the lines represents the perceived strength of the stakeholders’ influence. For example, politicians’ influence is demonstrated by the thickest line since they were perceived to be the ultimate decision-makers. As demonstrated by one respondent, ‘Priority setting is done by the politicians’ (Politician, District B). Furthermore, while the public may have a weak direct influence on the priority setting process (represented by the thin arrow in Figure 1) because they may not have a seat at the decision-making table, their indirect influence is stronger through the pressure they can exert on politicians through their electoral power (represented by the dashed arrow). In contrast, NGO/CSOs and donors have a direct seat on technical planning committees and are involved in the decision-making and therefore have a direct influence on priority setting at the district level.

Figure 1.

Stakeholders’ influence on priority setting at the district.

Reported challenges related to the participation of different stakeholders

The most commonly reported challenge for participation of different stakeholders was poor alignment of or conflicting priorities between the stakeholders, most notably between the district officers and donors and NGO/CSOs (see Table 7). According to the respondents, donor funding is often conditional, based on, and aligned with the priorities of the donor organization, and donor priorities may or may not align with the priorities of the district. Therefore, while local governments are not obliged to set priorities in accordance with donor priorities, donors tend to fund programmes that reflect their own interests. Hence, in a context where government funding is inadequate, the districts’ ability to use the donor’s support for the priority programmes (as identified by the district) is limited.

Table 7.

Challenges related to stakeholders’ participation in district-level decision-making

| Stakeholder | Perceived challenges | Illustrative quote(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Politicians | Potential for competing interests between political priorities and those generate from data and evidence | [s]o, the politicians also now come in… and if you don’t have a good backing of your priorities, then they have their own political priorities (Technical expert, District B). |

| District technical experts | None identified | N/A |

| Donors |

|

|

| NGO/CSOs | Organizational priorities may influence or overpower local priorities | Then at times as they [NGOs] come in with their support they also give conditions that we must fulfill (Technical expert, District C). |

| Cultural and traditional leaders | Balancing evidence from technical expert with religious doctrines and traditional beliefs | We realize there are some church doctrines that try to conflict with the health practitioners’ strategies in terms of maybe HIV struggle. When a health practitioner says condoms should be distributed and used, a religious leader will preach something different (Politician, District B). |

| Public/community | Lack of awareness about how priorities are determined | They are not aware. We try to use the centre, actually the office of the Prime Minister tries to create awareness… You are given so much money, what did you do for the community? (Technical expert, District A). |

Additional challenges were associated with stakeholders’ conflicting interests and/or values with respect to the health priorities that are set. For example, respondents discussed the differences between technical experts and cultural and traditional leaders (as illustrated by the quote in Table 7). The extent to which the stakeholders with conflicting interests may affect the prioritization process depends on the nature and strength of their leverage (see Figure 1). Notably, respondents did not identify any challenges related to the participation of district technical experts in priority setting.

Which stakeholders are missing?

All respondents emphasized the need to involve the public (as users of the services and health programmes) in priority setting processes. They identified the various ways the public can be and have been involved the prioritization process, but they also criticized the limited role currently played by the public.

Respondents talked about the existing avenues for public participation, including public meetings such as village council meetings, budget conferences and meetings (open forums that are announced on the radios and advertised), and through communicating with village health teams (VHTs), as illustrated in the quotes below:

Always in planning we involved the beneficiaries of our service delivery. We always either informally or formally meet them in public galleries; we always conduct participatory planning where the political leaders in each and every department sit together… (Politician, District B).

…Leaders and lay people who can come to the budget conference, an open discussion which is announced on the radio: the budget conference is on such and such a date and in such and such a place those who can; attend. Everybody’s free to come and attend (Technical expert, District C).

There was also a sense that the public tends to participate more at the lower levels of decision-making:

I think at parish level in the sub-county they attend. The local people may not but the opinion leaders and other important people in the community attend (Technical person, District C).

For us we want them to plan, we give them the information through the structures that we have, because if you’re asking their [the public] participation, they get involved. We have the village health teams at that level. In the review meetings, they [Village Health Teams] let us know why things have not happened that way. So those are the big voices (Technical person, District B).

Another way that the public contributes to decision-making is through their elected officials (politicians), community leaders, cultural and traditional leaders, and advocacy organizations:

We have the community leaders … they raise issues to the departments or to the committees about their priorities in a certain area. Then action is taken according to where they (the priorities) are raised. And what we do, we normally put as a priority area … we as a committee identify… but also we need to get responses from the lower local government community and the community themselves who are also involved in that (Politician, District B).

Despite these existing structures and avenues for public participation, most of the respondents across all three districts decried the limited participation of the public in district-level priority setting. For example, a respondent commenting on public participation at the budget conferences said, ‘(they are) very few, they (the public) don’t normally attend’ (Technical expert, District C).

Discussion

We found that politicians, technical experts and donors are the principal contributors to district-level priority setting, and the public is largely excluded. Politicians participate primarily through direct mechanisms including budget control and responsibility for resource allocation, while technical experts are viewed as authority figures whose priority recommendations are supported by evidence and expertise, and, in this way, able to exert influence over decision-making. Respondents also strongly emphasized the role of donors and NGO/CSOs in setting healthcare priorities. These stakeholders are directly involved in the priority setting process: they have a seat at the decision-making table and can influence priorities courtesy of the resources they provide in this low-income setting, as well as by using their specialized set of skills in producing evidence and providing expertise. Cultural and traditional leaders are involved to a lesser extent. They can directly influence priority setting and exert an indirect effect on the public in shaping public opinion. Finally, while the public was reported to influence priority setting through exertion of their electoral power, our findings demonstrate that they often do not attend budgeting, planning and priority setting meetings that occur within the district.

Our findings about the stakeholders that dominate priority setting in the Ugandan districts are reinforced by the broader literature on the stakeholder participation in health-system decision-making. Politicians are often the stakeholder group most involved in priority setting for healthcare (Martin et al., 2002). The participation of district politicians in priority setting decisions at the district level is legitimized by their role as the primary stakeholders responsible for representing the interests of people and communities within the district. However, some literature has questioned the degree to which politicians represent the public’s interests as opposed to the politicians’ own political interests (Charles and DeMaio, 1993; Tenbensel, 2002; Kapiriri et al., 2003; Contandriopoulos, 2004). Politicians may have their own motives and political agendas and therefore may not always act as honest brokers of the public’s healthcare priorities (Henriksson et al., 2017). This calls into question the legitimacy of politicians as representatives of the public, and suggests that they may have compromised abilities when it comes to making fair decisions when setting priorities for health. Our findings further reinforce the literature that asserts that, as evidence producers and knowledge synthesizers, technical experts are essential to guiding the prioritization process (Smith et al., 2014). Finally, as reflected in our results and in the literature, especially in low-income settings, donors are able provide the necessary resources to compensate for local governments’ lack of resources; these resources can be used to fund priorities and priority programmes once they have been confirmed (Kapiriri, 2012; Bolsewicz Alderman et al., 2013; Hipgrave et al., 2014). Furthermore, our respondents claimed that donors and NGO/CSOs had similar roles and leverages over district decision-making. This may be reflective of the nature of partnership relationships in development assistance (Reith, 2010). Donor–NGO partnerships are often characterized by the flow of resources (namely money) with donors controlling the funds that NGOs/CSOs seek to finance their programming with (Reith, 2010). This relationship may explain our respondents’ perceptions of donors and NGO/CSOs throughout the healthcare priority-setting process, and most notably the view that donors have a seat at the decision-making table and have a strong influence in priority setting processes.

Our findings also strengthen the evidence that the general public is missing from priority setting processes where health and health-system priorities are being set. More specifically, the public is not directly participating in the priority setting process. Our respondents appeared to attribute lack of public participation to individual factors such as lack of expertise or lack of time. This is reflected in the literature which attributes this lack of public participation to the public’s perceived lack of knowledge and objectivity, the leadership’s challenges with commitment and lack of time, and an inability to achieve representation (Martin et al., 2002; Kapiriri et al., 2003; Bruni et al., 2008; Meetoo, 2013). However, there are structural factors that impede public participation. While these factors were not explicitly mentioned by our respondents, structural barriers identified in the literature that hinder public participation in healthcare decision-making include poverty, gender, lack of decision-making power (Kapiriri et al., 2003; Denhardt et al., 2009; Bolsewicz Alderman et al., 2013). While some of the literature mentions limited direct public participation and difficulties with achieving representation, there is additional literature that discusses participation through representatives. The literature that supports public participation through representation argues that it may be practically impossible to bring everyone to the decision-making table (Emanuel, 1999; Rowe and Frewer, 2000). Others have questioned the capacity of the public to meaningfully participate and engage in decision-making processes (Emanuel, 1999; Abelson et al., 2003). Our findings contribute to the global literature by providing additional insight into public participation through indirect pathways such as political representation. This may support the politicians’ domination of district-level decision-making (discussed above).

The case of Uganda contrasts with some of the wider literature because there does appear to be commitment from leadership to include the public in decision-making, and there are also structures aimed at achieving representation. Specifically, the Ugandan constitution mandates public (with specific emphasis on vulnerable populations including women, the elderly, people with disabilities, and youths) participation in governmental decision-making, and the subsequent decentralization provided participatory structures to facilitate public participation (Government of Uganda, 1995, 1997, 2010). However, our respondents reported very little, if any, public participation. This is surprising given the existing opportunities, but is consistent with the other literature that identifies limited public participation in priority setting and health-sector decision-making in both high- and low-income settings (Martin et al., 2002; Kapiriri et al., 2003; Bruni et al., 2008; Mitton et al., 2009; Meetoo, 2013). In Uganda, this lack of participation has been attributed to a lack of both individual and community empowerment, poverty, a lack of interest, and a lack of mobilization, as well as a failure to effectively implement policies mandating public participation in health-sector planning and priority setting (Kapiriri et al., 2003; Kapiriri and Martin, 2006).

Challenges with stakeholder participation

The two main challenges with stakeholder participation that emerged in our study—conflicting priorities and/or interests, and conflicting values—are consistent with the literature. For example, as some of the literature identifies, politicians may forgo technical evidence if it does not align with their interests (Tenbensel, 2002). This is demonstrated in findings from our study, as our respondents identified the potential for competing interests between political priorities and evidence-informed priorities as a challenge with respect to the participation of politicians in district-level priority setting. Furthermore, there is literature that specifies challenges with the participation of donors and their ability to skew decisions to reflect their own priorities at the expense of local priorities (Glassman and Chalkidou, 2012; Kapiriri, 2012; Shayo et al., 2013; Hipgrave et al., 2014; Colenbrander et al., 2015). This was exemplified in this study where respondents discussed the impact of the conditions that donors attach to their funding. Since donors and NGO/CSOs often provide funds that the government lacks to support programme implementation, local governments are, to an extent, dependent on these stakeholders. Ugandans may lack a degree of agency, while simultaneously holding their own forms of leverage to influence district decision-making, Anderson and Patterson (2017) term this dependent agency(Anderson and Patterson, 2017), which makes balancing these competing interests a major challenge for district healthcare priority setting.

The findings also identified challenges stemming from competing values, such as balancing evidence from technical experts with religious doctrines and traditional beliefs. These findings are consistent with the literature, which acknowledges that priority setting in the health sector is a value-laden process that involves balancing stakeholders’ different criteria and values (Kapiriri and Martin, 2007). When different stakeholders hold different values or weights for the criteria (Kapiriri and Norheim, 2004; Mitton and Donaldson, 2004; Baltussen and Niessen, 2006), it is important that the values of all stakeholder groups are presented, and that these values are all carefully and systematically considered when making priority-setting decisions. The inclusion of all views can be achieved through stakeholders’ direct participation (either in the prioritization and decision-making processes, or through the enlisting of their values), or through representation—as long as the representatives present stakeholders’ values (Rowe and Frewer, 2000; Tenbensel, 2002; Abelson et al., 2003).

Study strengths and limitations

The primary strength of this article is that it builds on previous work on stakeholder participation and offers an in-depth analysis of different categories of stakeholders based on their roles, leverages and challenges with their participation in priority setting processes for health. Furthermore, the findings of the paper provide insight into power relations among stakeholders who may or may not have a seat at the decision-making table.

The original intent of the study was to examine the perspectives of district-level decision-makers about priority setting within their districts. Therefore, study respondents were targeted for their unique knowledge of district priority setting as members of the DHT and extended DHMT; however, this limited our respondents to politicians and technical experts. This sampling strategy may have biased the findings (e.g. none of our respondents identified challenges related to the participation of technical experts). However, the people sampled are responsible for setting priorities at the district level. A different group of respondents may not have had detailed understanding of district-level prioritization and stakeholder participation.

While respondents were asked about stakeholder involvement, it was not explored in further detail. Specifically, Elster’s framework was not used to design the study, therefore we lacked information on the detailed leverages and types of influences. A strength of our use of an inductive approach to data analysis is that although the information about leverages and influences emerged from the data, it was not specifically asked of the respondents.

Conclusions

Our research illuminates differential participation and influence over the decision-making process for healthcare priorities in Uganda. There are numerous policies in place in Uganda meant to facilitate stakeholder participation in governmental decision-making. Stakeholders’ different types of leverage affect their ability to influence the priority setting process. Imbalances of power, resources and expertise between the identified stakeholders affect the extent to which they can influence priority setting. Stakeholders appearing to have weak direct influence, may in fact have strong leverages that indirectly influence those directly engaged in priority setting, thus enhancing the ability of the former group of stakeholders to shape priority setting. Stakeholders’ leverages may also have implications for legitimacy. We assert that the current participatory structures seem to give more power and legitimacy to politicians—as representatives of the public—rather than to the public itself. It is evident that decentralization in Uganda has led to the development of devolved structures from the national level all the way down to the village level, with mechanisms for relaying information up through these pathways of communication. This invites the question: is representation an effective mechanism for participation? By exploring the degree to which politicians represent the interests of the public in a decentralized setting enhances our understanding of the mechanisms can be used to access public perspectives about health priorities and to effectively represent these priorities at the district level. Even at the lower levels where the public should participate, the public is reported to not be directly participating. As discussed above, there are certain barriers to participation for members of the public. We recommend enhanced mechanisms for participation at lower levels to facilitate politicians’ ability to gain input from communities, while strengthening channels of communication between the local and district levels so that participation through representation can prove effective. Future studies should focus on the examination of the public as a key stakeholder group and on understanding participation from the perspective of groups missing from the prioritization process to discern how these groups can more thoroughly participate within the district.

Ethical approval

The overall study received ethical approval from the McMaster University REB as well as the Makerere School of Public Health IRB.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our respondents from the three districts, and Dr. David Okumu and Brendan Kwesiga for assisting in the data collection. This work was supported by the Canadian Institute for Health Research, which supplied the funding for this project.

Funding

This work was supported by the Canadian Institute for Health Research (CIHR), which supplied the funding for this project.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

References

- Abelson J, Forest P-G, Eyles J.. 2003. Deliberations about deliberative methods: issues in the design and evaluation of public participation processes. Social Science and Medicine 57: 239–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aidem JM. 2017. Stakeholder views on criteria and processes for priority setting in Norway: a qualitative study. Health Policy 121: 683–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Garbayo A, Raven J, Theobald S. et al. 2017. Decision space for health workforce management in decentralized settings: a case study in Uganda. Health Policy and Planning 32: iii59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E-L, Patterson AS.. 2017. Dependent Agency in the Global Health Regime: Local African Responses to Donor AIDS Efforts. 1st edn. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Baltussen R, Niessen L.. 2006. Priority setting of health interventions: the need for multi-criteria decision analysis. Cost Effectiveness and Resource Allocation 4: 14.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolsewicz Alderman K, Hipgrave D, Jimenez-Soto E.. 2013. Public engagement in health priority setting in low- and middle-income countries: current trends and considerations for policy. PLoS Medicine 10: 8–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruni RA, Laupacis A, Martin DK.. 2008. Public engagement in setting priorities in health care. Canadian Medical Association Journal 179: 15–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles C, DeMaio S.. 1993. Lay participation in health care decision making: a conceptual framework. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 18: 23–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colenbrander S, Birungi C, Mbonye AK.. 2015. Consensus and contention in the priority setting process: examining the health sector in Uganda. Health Policy and Planning 30: 555–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contandriopoulos D. 2004. A sociological perspective on public participation in public health. Social Science & Medicine 58: 321–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels N, Sabin J.. 2008. Setting Limits Fairly: Learning to Share Resources for Health. 2nd edn. New York; Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Denhardt J, Terry L, Delacruz ER. et al. 2009. Barriers to citizen engagement in developing countries. International Journal of Public Administration 32: 1268–88. [Google Scholar]

- Emanuel EJ. 1999. Choice and representation in health care. Medical Care Research and Review 56(Suppl. 1): 113–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson JL, Martin D, Singer PA.. 2004. Setting priorities in health care organizations: criteria, processes, and parameters of success. BMC Health Services Research 4: 25.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilson L, Mills A.. 1995. Health sector reforms in sub-Saharan Africa: lessons of the last 10 years. Health Policy 32: 215–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glassman A, Chalkidou K.. 2012. Priority-Setting in Health Building Institutions for Smarter Public Spending. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Uganda. 1995. Constitution of the Republic of Uganda. Kampala: Republic of Uganda. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Uganda. 1997. Local Governments Act 1997. Kampala: The Republic of Uganda. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Uganda. 2010. Health Sector Strategic Plan III 2010/11–2014/15. Kampala: Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Uganda. 2016. Health Sector Supplement 2016 Guidelines to the Local Government Planning Process. Kampala: Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Henriksson DK, Ayebare F, Waiswa P. et al. 2017. Enablers and barriers to evidence based planning in the district health system in Uganda; perceptions of district health managers. BMC Health Services Research 17: 103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hipgrave DB, Alderman KB, Anderson I. et al. 2014. Health sector priority setting at meso-level in lower and middle income countries: lessons learned, available options and suggested steps. Social Science and Medicine 102: 190–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeppsson A, Okuonzi SA.. 2000. Vertical or holistic decentralization of the health sector? Experiences from Zambia and Uganda. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management 15: 273–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapiriri L. 2012. Priority setting in low income countries: the roles and legitimacy of development assistance partners. Public Health Ethics 5: 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- Kapiriri L, Arnesen T, Norheim OF.. 2004. Is cost-effectiveness analysis preferred to severity of disease as the main guiding principle in priority setting in resource poor settings? The case of Uganda. Cost Effectiveness and Resource Allocation 2: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapiriri L, Martin DK.. 2006. Priority setting in developing countries health care institutions: the case of a Ugandan hospital. BMC Health Services Research 6: 127.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapiriri L, Martin DK.. 2007. A strategy to improve priority setting in developing countries. Health Care Analysis 15: 159–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapiriri L, Norheim OF.. 2004. Criteria for priority-setting in health care in Uganda: exploration of stakeholders’ values. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 82: 172–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapiriri L, Norheim OF, Heggenhougen K.. 2003. Public participation in health planning and priority setting at the district level in Uganda. Health Policy and Planning 18: 205–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapiriri L, Norheim OF, Martin DK.. 2007. Priority setting at the micro-, meso- and macro-levels in Canada, Norway and Uganda. Health Policy 82: 78–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapiriri L, Razavi D.. 2017. How have systematic priority setting approaches influenced policy making? A synthesis of the current literature. Health Policy 121: 937–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maluka S, Kamuzora P, San Sebastián M. et al. 2010. Improving district level health planning and priority setting in Tanzania through implementing accountability for reasonableness framework: perceptions of stakeholders. BMC Health Services Research 10: 322.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maluka SO. 2011. Strengthening fairness, transparency and accountability in health care priority setting at district level in Tanzania. Global Health Action 4: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin DK, Abelson J, Singer PA.. 2002. Participation in health care priority-setting through the eyes of the participants. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy 7: 222–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meetoo D. 2013. The setting of healthcare priorities through public engagement. British Journal of Nursing 22: 372–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills A. 1994. Decentralization and accountability in the health sector from an international perspective: what are the choices? Public Administration and Development 14: 281–92. [Google Scholar]

- Mitton C, Donaldson C.. 2004. Health care priority setting: principles, practice and challenges. Cost Effectiveness and Resource Allocation 2: 3.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitton C, Smith N, Peacock S. et al. 2009. Public participation in health care priority setting: a scoping review. Health Policy 91: 219–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogedal S, Steen SH, Mpelumbe G.. 1995. Health sector reform and organizational issues at the local level: lessons from selected African countries. Journal of International Development 7: 349–67. [Google Scholar]

- O’Meara WP, Tsofa B, Molyneux S, Goodman C, McKenzie FE.. 2011. Community and facility-level engagement in planning and budgeting for the government health sector—a district perspective from Kenya. Health Policy 99: 234–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okello WO, Muhanguzi D, MacLeod ET.. 2015. Contribution of draft cattle to rural livelihoods in a district of southeastern Uganda endemic for bovine parasitic diseases: an economic evaluation. Parasites & Vectors 8: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regier DA, Bentley C, Mitton C. et al. 2014. Public engagement in priority-setting: results from a pan-Canadian survey of decision-makers in cancer control. Social Science and Medicine 122: 130–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reith S. 2010. Money, power, and donor-NGO partnerships. Development in Practice 20: 446–55. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe G, Frewer LJ.. 2000. Public participation methods: a framework for evaluation. Science Technology & Human Values 25: 3–29. [Google Scholar]

- Shayo EH, Mboera LEG, Blystad A.. 2013. Stakeholders’ participation in planning and priority setting in the context of a decentralised health care system: the case of prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV programme in Tanzania. BMC Health Services Research 13: 273.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibbald SL, Singer PA, Upshur R, Martin DK.. 2009. Priority setting: what constitutes success? A conceptual framework for successful priority setting. BMC Health Services Research 9: 43.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith N, Mitton C, Davidson A. et al. 2014. A politics of priority setting: ideas, interests and institutions in healthcare resource allocation. Public Policy and Administration 29: 331–47. [Google Scholar]

- Tenbensel T. 2002. Interpreting public input into priority-setting: the role of mediating institutions. Health Policy 62: 173–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S. 2016. Interpretive Description. 2nd edn. New York; London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S, Kirkham SR, O’Flynn-Magee K.. 2004. The analytic challenge in interpretive description. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 3: 1–11. [Google Scholar]