Abstract

Background

ASP8273, a novel, small molecule, irreversible tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) specifically inhibits the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) in patients with activating mutations or EGFR T790M resistance mutations. The current study examines the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of ASP8273 versus erlotinib or gefitinib in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with activating EGFR mutations not previously treated with an EGFR inhibitor.

Patients and methods

This global, phase III, open-label, randomized study evaluated ASP8273 versus erlotinib/gefitinib in patients with locally advanced, metastatic, or unresectable stage IIIB/IV NSCLC with activating EGFR mutations. They were ineligible if they received prior chemotherapy for metastatic disease. The primary end point was progression-free survival (PFS), and secondary end points included overall survival, investigator-assessed PFS, best overall response rate (ORR), disease control rate, duration of response (DoR), and the safety/tolerability profile.

Results

Patients (n = 530) were randomized 1 : 1 to receive ASP8273 (n = 267) or erlotinib/gefitinib (n = 263). Patient demographics between both treatment groups were generally balanced. Median PFS was 9.3 months (95% CI 5.6–11.1 months) for patients receiving ASP8273 and 9.6 months (95% CI 8.8–NE) for the erlotinib/gefitinib group, with a hazard ratio of 1.611 (P = 0.992). The ORR in the ASP8273 group was 33% (95% CI 27.4–39.0) versus 47.9% (95% CI 41.7–54.1) in the erlotinib/gefitinib group. Median DoR was similar for both groups (9.2 months for ASP8273 versus 9.0 months for erlotinib/gefitinib). More grade ≥3 treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) occurred in patients receiving ASP8273 than in those receiving erlotinib/gefitinib (54.7% versus 43.5%). An independent data monitoring committee carried out an interim safety analysis and recommended discontinuing the study due to toxicity and limited predicted efficacy of ASP8273 relative to erlotinib/gefitinib.

Conclusions

First-line ASP8273 did not show improved PFS or equivalent toxicities versus erlotinib/gefitinib.

ClinicalTrial.gov number

Keywords: non-small-cell lung cancer, ASP8273, EGFR inhibitor, phase III clinical trial

Key Message

Although ASP8273 was well tolerated and promoted antitumor activity in prior early phase studies in patients with EGFR-mutated lung cancer with disease progression on prior EGFR TKI therapy, ASP8273 was not superior to a first-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor in the current phase III study.

Introduction

The incidence of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene mutations in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is 10% in Europe/North America and 30% in Asia [1]. Activating mutations, including deletions in exon 19 and L858R point mutations in exon 21, account for ∼90% of EGFR mutations in NSCLC [2]. EGFR regulates tumor cell survival, proliferation, angiogenesis, and invasion; activating EGFR mutations (e.g. L858R) are associated with increased survival and responses to tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy [3, 4]. Growing evidence also suggests that EGFR mutations are predictive of clinical responses. For example, T790M mutations are associated with a failure to respond to TKI therapy; ≥50% of patients with NSCLC resistant to erlotinib/gefitinib acquire T790M mutations [4, 5]. Targeting both EGFR activating and T790M mutations with osimertinib demonstrated superior efficacy to the current standard-of-care EGFR-targeting TKI therapies (erlotinib and gefitinib), with a similar safety profile and fewer serious adverse events [6].

ASP8273 is a novel, small molecule, irreversible TKI that inhibits EGFR activity in patients with exon 19 deletions, L858R substitutions in exon 21, as well as T790M resistance mutations [7, 8]. In early phase studies, ASP8273 demonstrated antitumor activity in patients with EGFR mutation-positive NSCLC. In a first-in-human study in Japanese patients, median progression-free survival (PFS) was 5.6 months [95% confidence interval (CI) 3.6–11.1] and the overall response rate (ORR) was 49% (95% CI 33.7–64.2) in patients treated with 25–600 mg ASP8273 [7]. In North American patients with EGFR T790M mutations who progressed after prior TKI therapy (treated with 25–500 mg ASP8273), median PFS was 6.8 months (95% CI 5.5–10.1 months) and the ORR was 31.0% (95% CI 19.5–44.5) [9].

This phase III study assessed the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of ASP8273 versus erlotinib/gefitinib in patients with newly diagnosed or recurrent locally advanced, metastatic, or unresectable stage IIIB/IV adenocarcinoma NSCLC with EGFR activating mutations not previously treated with an EGFR inhibitor.

Methods

Study design

This global, phase III, open-label, randomized study (NCT02588261) included eligible patients with histologically confirmed advanced/metastatic or unresectable stage IIIB/IV adenocarcinoma NSCLC, an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) of ≤2, and a life expectancy of ≥12 weeks. Previously untreated patients with activating EGFR mutations (exon 19 deletion or exon 21 L858R), with or without T790M or other rare EGFR mutations associated with lower sensitivity or resistance were eligible; those harboring both exon 19 deletions and L858R were not. Patients were randomized based on local mutation status and remained on study if central results were discordant. Patients could not have symptomatic central nervous system metastases or prior EGFR-targeting therapy, or prior chemotherapy for metastatic disease (except palliative local radiation for painful bone metastases completed ≥1 week before the first dose of study drug). The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Council for Harmonisation, and Good Clinical Practice Guidelines. Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Eligible patients were randomized (1 : 1) via interactive response technology to either the ASP8273 or erlotinib/gefitinib arms. Randomization was stratified by ECOG PS (0 versus 1 versus 2), EGFR mutation type (exon 19 deletion versus L858R mutation in exon 21), choice of TKI (erlotinib versus gefitinib), and race (Asian versus non-Asian) (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). Investigators selected erlotinib/gefitinib before site initiation or shipment of study drug. ASP8273 300 mg, erlotinib 150 mg, or gefitinib 250 mg was administered orally once daily. Concomitant medications were not administered within 2 h of dosing with ASP8273, erlotinib, or gefitinib.

An independent data monitoring committee (IDMC), chartered at study initiation to oversee safety, carried out an interim safety and futility analysis from 417 randomized patients (ASP8273, n = 209; erlotinib/gefitinib, n = 208). During the futility analysis, the predictive probability that the response rate would be higher in patients receiving ASP8273 compared with erlotinib/gefitinib if all 600 subjects are enrolled was 0.00009. Therefore, on 4 May 2017, the IDMC recommended stopping the study before it was fully enrolled based on increased toxicity and limited predicted efficacy of ASP8273 relative to erlotinib/gefitinib. After study discontinuation, patients receiving erlotinib/gefitinib entered a 3-month transition period. No new patients were enrolled in ASP8273 studies, but patients with exon 20 point mutations from another phase I study (NCT02113813) without available standard-of-care therapies could continue ASP8273 under revised consent parameters.

Datasets with scrambled treatment codes were transferred to prepare analysis programs. Randomized treatment codes were not transferred to statistical programmers, the study statistician, or supporting statisticians before the database lock, nor did these individuals have direct access to randomized treatment information before the database lock. Only study managers and team members had access to individual patient treatment information.

End points and assessments

The primary end point was PFS based on blinded, independent radiologic review (IRR). Secondary end points included investigator-assessed PFS, best ORR [complete responses (CR) +partial responses (PR)], disease control rate [CR +PR +stable disease (SD)], duration of response (DoR), and the safety and tolerability profile. Responses were assessed every 8 weeks (±7 days) throughout the duration of the study.

The full analysis set (FAS) represents all randomized patients and was used for efficacy analyses. The safety analysis set (SAF) included all patients taking ≥1 dose of study drug and was used for statistical summaries of safety data. The distribution of PFS was estimated using Kaplan–Meier methodology. A stratified Cox proportional hazard model estimated hazard ratios and corresponding 95% CI. Response and progression were evaluated using Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST v1.1). The statistical analysis plan was finalized before study unblinding, database lock, interim analysis, or accumulation of substantial data. Approximately 600 patients were planned to be randomized. Assuming a hazard ratio of 0.667 (median PFS in the 8273 and erlotinib/gefitinib arm were 15.6 and 10.4 months, respectively), 420 PFS events would provide ∼98.7% power to detect a statistically significant difference at type I error rate of one-sided 0.025.

Results

Patients

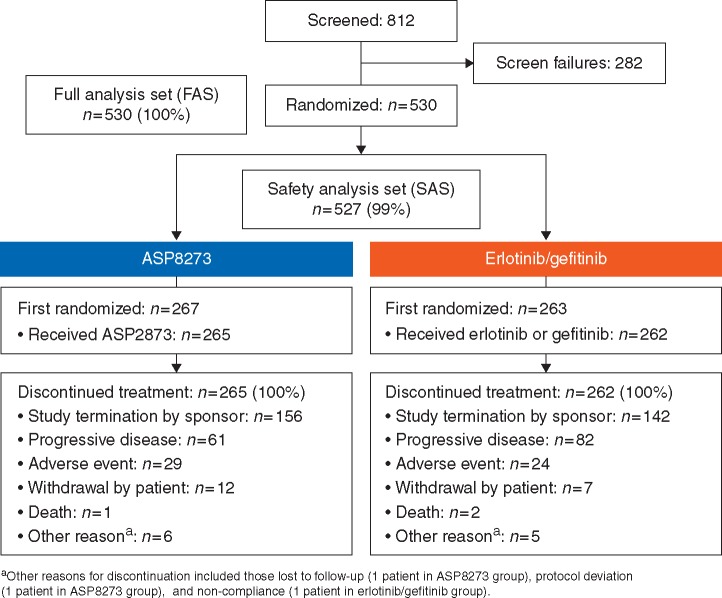

This study was conducted between 11 February 2016 and 21 December 2017 at 201 sites across 23 countries worldwide. A total of 812 patients were screened and signed informed consent; 282 (34.7%) patients discontinued before randomization. A total of 530 patients were randomized; 267 patients received ASP8273 and 263 received erlotinib (n = 151) or gefitinib (n = 112) (Figure 1). Of enrolled patients, 99.4% (n = 527) received ≥1 dose of study drug. In the FAS (n = 530), reasons for discontinuation included termination of study by sponsor (57%; n = 298), disease progression (27%; n = 143), adverse events (10%; n = 53), and death (<1%; n = 3).

Figure 1.

Patient disposition.

Patient demographics and baseline disease characteristics were similar between both treatment arms (Table 1). The median age was 67 years (range 23–89 years) and ∼61% (n = 324) were female. Among all patients, 49.6% (n = 263) had investigator-assessed exon 19 deletions, 41.3% (n = 219) had an L858R mutation, and 1.9% (n = 10) had a T790M mutation. Most patients (96.8%; n = 513) had an ECOG PS ≤1 and 64.5% (n = 342) never used tobacco.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristics (FAS)

| ASP8273 | Erlotinib/ gefitinib | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 267 | n = 263a | N = 530 | |

| Median age, years (range) | 68 (32–88) | 67 (23–89) | 67 (23–89) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 96 (36.0) | 110 (41.8) | 206 (38.9) |

| Female | 171 (64.0) | 153 (58.2) | 324 (61.1) |

| Median time from diagnosis, days (range) | |||

| Duration from initial diagnosis | 50 (15–3303) | 44 (10–3663) | 47 (10–3663) |

| Duration from locally advanced/ metastatic disease diagnosis | 37 (3–1432) | 36 (4–1525) | 36 (3–1525) |

| Most recent NSCLC stage, n (%) | |||

| Stage IIIB | 14 (5.2) | 16 (6.1) | 30 (5.7) |

| Stage IV | 251 (94.0) | 247 (93.9) | 498 (94) |

| Missing | 2 (<1) | 0 | 2 (<1) |

| EGFR mutation type, n (%) | |||

| Exon 19 deletion | 134 (50.2) | 129 (49.0) | 263 (49.6) |

| Exon 21 L858R | 111 (41.6) | 108 (41.1) | 219 (41.3) |

| T790M | 4 (1.5) | 6 (2.3) | 10 (1.9) |

| ECOG PS, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 103 (38.6) | 103 (39.2) | 206 (38.9) |

| 1 | 155 (58.1) | 152 (57.8) | 307 (57.9) |

| 2 | 9 (3.4) | 8 (3.0) | 17 (3.2) |

| Tobacco history, n (%) | |||

| Never | 171 (64.0) | 171 (65.0) | 342 (64.5) |

| Current | 12 (4.5) | 9 (3.4) | 21 (4.0) |

| Former | 84 (31.5) | 83 (31.6) | 167 (31.5) |

One hundred and fifty-one patients received erlotinib and 112 received gefitinib.

ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; FAS, full analysis set; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer.

Efficacy

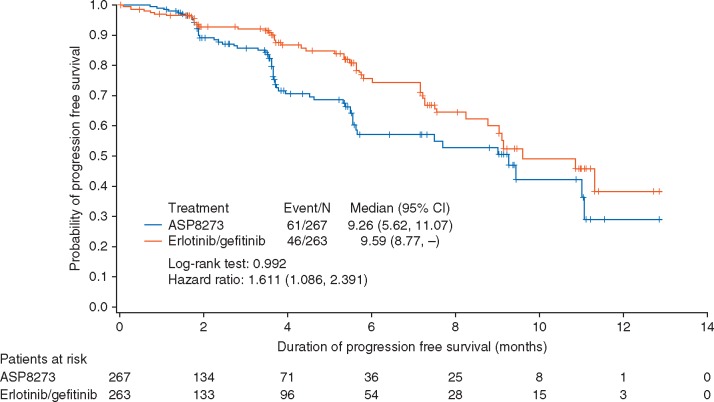

At the time of this interim analysis, there were 107 PFS events assessed by IRR (n = 61, 22.8% for ASP8273 and n = 46, 17.5% for erlotinib/gefitinib). Median duration of follow-up was 3.5 months for patients receiving ASP8273 and 3.6 months for those receiving erlotinib/gefitinib. Median PFS was 9.3 months (95% CI 5.6–11.1 months) in patients receiving ASP8273 and 9.6 (95% CI 8.8–NE) in those receiving erlotinib/gefitinib, with a hazard ratio of 1.611 (P = 0.992) (Figure 2). The 6-month PFS rate was 57% (95% CI 46.8–66.0) for ASP8273 and 76% (95% CI 66.6–82.7) in erlotinib/gefitinib; the 12-month PFS rate was 29% (95% CI 12.8–47.5) and 38% (95% CI 20.8–55.5), respectively.

Figure 2.

Progression-free survival (FAS). CI, confidence interval; FAS, full analysis set.

No CR were seen in either treatment arm (Table 2). Fewer patients receiving ASP8273 achieved PR (33% versus 48%) versus those receiving erlotinib/gefitinib, but more had SD (29% versus 18%). The ORR in patients treated with ASP8273 was 33% (95% CI 27.4–39.0); patients receiving erlotinib/gefitinib had an ORR of 47.9% (95% CI 41.7–54.1). The disease control rate (62% versus 66%) and median DoR (9.2 versus 9.0 months) were similar for both treatment arms.

Table 2.

Response rates (FAS)

| ASP8273 | Erlotinib/gefitinib | |

|---|---|---|

| n = 267 | n = 263 | |

| Best overall response, n (%) | ||

| Complete response | 0 | 0 |

| Partial response | 88 (33.0) | 126 (47.9) |

| Stable disease | 78 (29.2) | 48 (18.3) |

| Progressive disease | 17 (6.4) | 9 (3.4) |

| Overall response rate, n (%) | 88 (33.0) | 126 (47.9) |

| 95% CI, % | 27.4, 39.0 | 41.7, 54.1 |

| Stratified one-sided P valuea | 1.0 | NA |

| Disease control rate,bn (%) | 166 (62.2) | 174 (66.2) |

| 95% CI, % | 56.1, 68.0 | 60.1, 71.9 |

| Stratified one-sided P valuea | 0.839 | NA |

| Duration of responseb | ||

| Events, n (%) | 16/88 (18.2) | 24/126 (19.0) |

| Censored, n (%) | 72 (81.8) | 102 (81.0) |

| Median (95% CI), months | 9.17 (5.45, NE) | 9.03 (7.39, NE) |

| Range,c months | 0.03+, 9.46+ | 0.03+, 11.10+ |

| Stratified one-sided P valuea,d | 0.780 | NA |

| Hazard ratioe (95% CI) | 1.298 (0.661, 2.548) | NA |

Stratification factors were ECOG PS (0 and 1 versus 2), EGFR mutation type (exon 19 deletion versus exon 21 L8598R), and chosen TKI (erlotinib versus gefintinib).

Based on the Kaplan–Meier estimate.

Plus sign (+) indicates censoring.

P value was based on the log-rank test.

Based on the Cox proportional hazards model.

CI, confidence interval; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; FAS, full analysis set; NA, not applicable; NE, not evaluable; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Safety and tolerability profile of ASP8273

Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were reported by 251 (94.7%) patients receiving ASP8273 and 261 (99.6%) receiving erlotinib/gefitinib; an overview for both arms is presented in Table 3. Serious TEAEs were reported in 151 (28.7%) patients; 84 (31.7%) in patients receiving ASP8273 and 67 (25.6%) for erlotinib/gefitinib. A total of 74 patient deaths were reported; 31 (5.9%) were due to TEAEs (5.3% of patients and 6.5% receiving ASP8273 or erlotinib/gefitinib, respectively). Two of the TEAEs leading to death were considered related to study drug: acute myocardial infarction and embolic stroke (ASP8273; n = 1) and interstitial lung disease (erlotinib/gefitinib; n = 1). Treatment-emergent AEs led to treatment withdrawal in 67 (12.7%) patients, including 39 (14.7%) receiving ASP8273 and 28 (10.7%) receiving erlotinib/gefitinib. The most common TEAEs leading to withdrawal were increased alanine aminotransferase (n = 13), increased aspartate aminotransferase (n = 9), and interstitial lung disease (n = 7). Treatment-emergent AEs considered related to study drug led to withdrawal in 44 (8.3%) patients, including 27 (10.2%) patients receiving ASP8273 and 17 (6.5%) patients receiving erlotinib/gefitinib.

Table 3.

Incidence of TEAEs (SAF)

| ASP8273 | Erlotinib/ gefitinib | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 265 | n = 262 | N = 527 | |

| TEAEs | 251 (94.7) | 261 (99.6) | 512 (97.2) |

| Serious TEAE | 84 (31.7) | 67 (25.6) | 151 (28.7) |

| Grade ≥3 TEAE | 145 (54.7) | 114 (43.5) | 259 (49.1) |

| TEAE leading to treatment withdrawal | 39 (14.7) | 28 (10.7) | 67 (12.7) |

| TEAE leading to dose interruption | 95 (35.8) | 74 (28.2) | 169 (32.1) |

| TEAE leading to dose reduction | 51 (19.2) | 51 (19.5) | 102 (19.4) |

| Deaths | 39 (14.7) | 35 (13.4) | 74 (14.0) |

| TEAE leading to death | 14 (5.3) | 17 (6.5) | 31 (5.9) |

| Drug-related TEAEs | 235 (88.7) | 246 (93.9) | 481 (91.3) |

| Serious drug-related TEAE | 46 (17.4) | 18 (6.9) | 64 (12.1) |

| Grade ≥3 drug-related TEAE | 122 (46.0) | 67 (25.6) | 189 (35.9) |

| Drug-related TEAE leading to withdrawal | 27 (10.2) | 17 (6.5) | 44 (8.3) |

| Drug-related TEAE leading to dose interruption | 83 (31.3) | 55 (21.0) | 138 (26.2) |

| Drug-related TEAE leading to dose reduction | 51 (19.2) | 50 (19.1) | 101 (19.2) |

| Drug-related TEAE leading to death | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.4) |

Data presented as n (%).

SAF, safety analysis set; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

The most common TEAE considered at least possibly related to ASP8273 was diarrhea (59.2% versus 49.2%); skin rash (10.2% versus 70.6%) was the most common TEAE considered related to erlotinib/gefitinib (Table 4). Patients receiving ASP8273 had a higher incidence of hyponatremia (22.6% versus 1.5%), peripheral sensory neuropathy (20.4% versus 0.8%), and fatigue (14.7% versus 7.3%) versus those receiving erlotinib/gefitinib. Compared with those on ASP8273, patients receiving erlotinib/gefitinib had higher incidences of paronychia (25% versus 1%) and stomatitis (19% versus 6%). The most common grade ≥3 TEAEs considered at least possibly related to treatment were hyponatremia (n = 56; 11%), increased alanine aminotransferase (n = 30; 6%), and diarrhea (n = 23; 4%).

Table 4.

Drug-related TEAEs (SAF)

| ASP8273 |

Erlotinib/gefitinib |

Total |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

n = 265 |

n = 262 |

N = 527 |

||||

| Overall | Grade ≥3 | Overall | Grade ≥3 | Overall | Grade ≥3 | |

| Any drug-related TEAE in ≥10% of patients | ||||||

| Diarrhea | 157 (59.2) | 16 (6.0) | 129 (49.2) | 7 (2.7) | 286 (54.3) | 23 (4.4) |

| Skin Rash | 27 (10.2) | 0 | 185 (70.6) | 19 (7.3) | 212 (40.2) | 19 (3.6) |

| Increased ALT | 49 (18.5) | 17 (6.4) | 49 (18.7) | 13 (5.0) | 98 (18.6) | 30 (5.7) |

| Dry skin | 26 (9.8) | 0 | 65 (24.8) | 1 (<1) | 91 (17.3) | 1 (<1) |

| Nausea | 52 (19.6) | 5 (1.9) | 20 (7.6) | 1 (<1) | 72 (13.7) | 6 (1.1) |

| Increased AST | 32 (12.1) | 4 (1.5) | 40 (15.3) | 10 (3.8) | 72 (13.7) | 14 (2.7) |

| Decreased appetite | 44 (16.6) | 5 (1.9) | 27 (10.3) | 1 (<1) | 71 (13.5) | 6 (1.1) |

| Paronychia | 3 (1.1) | 0 | 66 (25.2) | 4 (2.0) | 69 (13.1) | 4 (<1) |

| Stomatitis | 16 (6.0) | 0 | 50 (19.1) | 2 (<1) | 66 (12.5) | 2 (<1) |

| Hyponatremia | 60 (22.6) | 54 (20.4) | 4 (1.5) | 2 (<1) | 64 (12.1) | 56 (10.6) |

| Fatigue | 39 (14.7) | 9 (3.4) | 19 (7.3) | 1 (<1) | 58 (11.0) | 10 (1.9) |

| Peripheral sensory neuropathy | 54 (20.4) | 1 (<1) | 2 (<1) | 0 | 56 (10.6) | 1 (<1) |

Data presented as n (%).

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; SAF, safety analysis set; TEAE; treatment-emergent adverse event.

Discussion

In this phase III study, first-line ASP8273 did not reach its primary efficacy end point. The apparent antitumor effect of ASP8273 was numerically less than the control arm and the study was discontinued due to increased toxicity and limited predicted efficacy of ASP8273 relative to erlotinib/gefitinib. Median PFS was 9.3 months with ASP8273 and 9.6 months with erlotinib/gefitinib. The percentage of patients experiencing grade ≥3 TEAEs was higher in those receiving ASP8273 than those receiving erlotinib/gefitinib (54.7% versus 43.5%, respectively), as was the percentage of patients experiencing serious TEAEs (31.7% versus 25.6%). Importantly, while the gastrointestinal (diarrhea, stomatitis, and mucositis) and cutaneous (rash, dry skin, and paronychia) treatment‐related toxicities seen with ASP8273 were similar to those seen with other TKIs [10], ASP8273 demonstrated additional, unpredicted toxicities. Specifically, patients treated with ASP8273 were more likely to experience hyponatremia (5.3% versus 0.4%) or peripheral sensory neuropathy (38.5% versus 5.3%) versus those treated with erlotinib/gefitinib. While both toxicities had been reported in patients treated with ASP8273 during previous phase I (NCT02113813) and phase II (NCT02500927) studies, differences between patient populations made it unclear how the incidence of these adverse events would compare with patients receiving erlotinib/gefitinib [8, 9]. Preclinical data suggested ASP8273 penetrated the blood–brain barrier and antitumor activity was observed in brain tumors (data on file), similar to other TKIs including gefitinib, erlotinib, and icotinib [11]. Based on data showing limited efficacy and excessive toxicity versus the erlotinib/gefitinib group, this study was discontinued.

Although the in vitro and in vivo preclinical activity of ASP8273 is similar to osimertinib (data on file), the pyrazine carboxamide-based structure and reactive acrylamide moiety of ASP8273 differs from the pyrimidine-based chemical structure used by other third-generation EGFR-TKIs such as osimertinib and rociletinib [12, 13] and may potentially contribute to differences in efficacy and toxicity. In the current study, both study arms demonstrated lower than expected efficacy and neither treatment resulted in CR. We observed a 48% response rate for patients in the erlotinib/gefitinib arm, despite reports of 65% ORR for erlotinib [14] and ∼70% ORR for gefitinib [15]. The median PFS of 9.6 months for the comparator arm was also lower compared with historic results for erlotinib in the EURTAC trial (10.4 months) [14] and gefitinib (10.9 months) in patients with NSCLC [16].

Patient characteristics, especially with respect to EGFR mutation profile, may have impacted treatment outcomes and toxicities in the current trial. While previous reports of erlotinib efficacy in NSCLC patients from the EURTAC trial had a similar patient population in terms of sex, age, disease stage, and smoking status, there was a difference in EGFR exon 19 deletions (66% versus ∼50%) and EGFR exon 21 (L858R) mutations (34% versus 41%), as well as a higher proportion of ECOG PS 2 (14% versus 3%) compared with the current study [14, 17]. A prior report of ASP8273 in patients with NSCLC with EGFR mutations investigated using circulating free DNA (cfDNA) as a biomarker of ASP8273 clinical responses and found that ASP8273 decreased EGFR T790M cfDNA below the level of detection across all doses, confirming successful on-target inhibition [9]. Clinical response to ASP8273 and disease progression was correlated with EGFR T790M cfDNA, with a strong concordance between cfDNA detection and local tissue testing (96%, 67%, and 79% for EGFR L858R, ex19del, and T790M, respectively) [9]. While cfDNA mutation analysis may have proved useful in the current study, the logistics of collecting patient samples from over 500 patients across 23 countries would have been exceedingly difficult.

In conclusion, although ASP8273 was well tolerated and promoted antitumor activity in prior early phase studies in a similar patient population [7–9], ASP8273 did not reach its primary efficacy end point in the current phase III study. At this time, there are no future developmental plans for ASP2783 in NSCLC.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge all investigators, coordinators, and study site personnel, as well as the patients and their families for their participation in this study.

Data sharing: Access to anonymized individual participant level data collected during the trial, in addition to supporting clinical documentation, is planned for trials conducted with approved product indications and formulations, as well as compounds terminated during development. Conditions and exceptions are described under the Sponsor Specific Details for Astellas on www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com. Study-related supporting documentation is redacted and provided if available, such as the protocol and amendments, statistical analysis plan and clinical study report. Access to participant level data is offered to researchers after publication of the primary manuscript (if applicable) and is available as long as Astellas has legal authority to provide the data. Researchers must submit a proposal to conduct a scientifically relevant analysis of the study data. The research proposal is reviewed by an Independent Research Panel. If the proposal is approved, access to the study data are provided in a secure data sharing environment after receipt of a signed Data Sharing Agreement.

Funding

This study was funded by Astellas Pharma, Inc. (Northbrook, IL; no grant number applicable). All authors had access to the study results, and the lead author vouches for the accuracy and completeness of the data reported. Financial support for the development of this manuscript was provided by the study sponsor. Writing and editorial assistance, provided by Stephan Lindsey, PhD, of OPEN Health Medical Communications (Chicago, IL) under the authors’ guidance, was funded by the study sponsor (no grant number applicable for funding).

Disclosure

RJK has served in a consultancy or advisory role for Astellas, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, AstraZeneca, Novartis, Gritstone Oncology, and Cardinal Health and has received research support/grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and AstraZeneca. FS has served in a consultancy or advisory role for and has received personal fees from Astellas. AK owns stock in Abbvie and Abbott, has a patent licensed by Abbott to Abbvie, and has received personal fees from and is employed by Astellas. FJ is employed by Astellas. AZ has served in a consultancy or advisory role for AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, AbbVie, Incyte, EMD Serono, Genentech, Xcovery, and Merck.

References

- 1. Bell DW, Lynch TJ, Haserlat SM. et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations and gene amplification in non-small-cell lung cancer: molecular analysis of the IDEAL/INTACT gefitinib trials. JCO 2005; 23(31): 8081–8092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ladanyi M, Pao W.. Lung adenocarcinoma: guiding EGFR-targeted therapy and beyond. Mod Pathol 2008; 21(Suppl 2): S16–S22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Herbst RS, Heymach JV, Lippman SM.. Lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2008; 359(13): 1367–1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Esposito L, Conti D, Ailavajhala R. et al. Lung cancer: are we up to the challenge? Curr Genomics 2010; 11(7): 513–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ohashi K, Maruvka YE, Michor F, Pao W.. Epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor-resistant disease. JCO 2013; 31(8): 1070–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Soria JC, Ohe Y, Vansteenkiste J. et al. Osimertinib in untreated EGFR-mutated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2018; 378(2): 113–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Murakami H, Nokihara H, Hayashi H. et al. Clinical activity of ASP8273 in Asian patients with non-small-cell lung cancer with EGFR activating and T790M mutations. Cancer Sci 2018; 109(9): 2852–2862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Azuma K, Nishio M, Hayashi H. et al. ASP8273 tolerability and antitumor activity in tyrosine kinase inhibitor-naive Japanese patients with EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Sci 2018; 109(8): 2532–2538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yu HA, Spira A, Horn L. et al. A phase I, dose escalation study of oral ASP8273 in patients with non-small cell lung cancers with epidermal growth factor receptor mutations. Clin Cancer Res 2017; 23(24): 7467–7473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Califano R, Tariq N, Compton S. et al. Expert consensus on the management of adverse events from EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in the UK. Drugs 2015; 75(12): 1335–1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tan J, Li M, Zhong W. et al. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors show different anti-brain metastases efficacy in NSCLC: a direct comparative analysis of icotinib, gefitinib, and erlotinib in a nude mouse model. Oncotarget 2017; 8: 98771–98781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cross DA, Ashton SE, Ghiorghiu S. et al. AZD9291, an irreversible EGFR TKI, overcomes T790M-mediated resistance to EGFR inhibitors in lung cancer. Cancer Discov 2014; 4(9): 1046–1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Walter AO, Sjin RT, Haringsma HJ. et al. Discovery of a mutant-selective covalent inhibitor of EGFR that overcomes T790M-mediated resistance in NSCLC. Cancer Discov 2013; 3(12): 1404–1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Khozin S, Blumenthal GM, Jiang X. et al. U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval summary: erlotinib for the first-line treatment of metastatic non-small cell lung cancer with epidermal growth factor receptor exon 19 deletions or exon 21 (L858R) substitution mutations. Oncologist 2014; 19(7): 774–779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Douillard JY, Ostoros G, Cobo M. et al. First-line gefitinib in Caucasian EGFR mutation-positive NSCLC patients: a phase-IV, open-label, single-arm study. Br J Cancer 2014; 110(1): 55–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iressa (Gefitinib) [Prescribing Information]. Wilmington, DE: AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP 2018.

- 17.Terceva (Erlotinib) [Prescribing Information]. Northbrook, IL: Astellas Pharma US, Inc. 2016.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.