Abstract

Background:

Lactobacillus paracasei and Glycyrrhiza glabra have been reported as having beneficial effects on Helicobacter pylori infection. We aimed to assess the efficacy and safety of fermented milk containing L paracasei HP7 and G glabra in patients with H pylori infection.

Methods:

This multicenter, prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial was conducted in 2 hospitals from April to December 2017. Patients with H pylori infection were randomized into either the treatment group (fermented milk with L paracasei HP7 and G glabra) or placebo group (fermented milk only) once daily for 8 weeks. The primary endpoint was the gastric load of H pylori measured by 13C-urea breath test (UBT). Secondary endpoints were histologic and clinical improvement.

Results:

A total of 142 patients were randomly allocated to the treatment (n = 71) or placebo groups (n = 71). Compared to baseline data, the quantitative value of 13C-UBT at 8 weeks was significantly reduced in the treatment group (from 20.8 ± 13.2% to 16.9 ± 10.8%, P = .035), but not in the placebo group (P = .130). Chronic inflammation improved significantly only in the treatment group (P = .013), whereas the neutrophil activity deteriorated significantly only in the placebo group (P = .003). Moreover, the treatment group had significant improvement in gastrointestinal symptoms (P = .049) and quality of life (P = .029). No serious adverse events were observed.

Conclusion:

The combination of fermented milk containing L paracasei and G glabra reduced H pylori density and improved histologic inflammation. However, their mechanisms of action should be elucidated in further studies.

Keywords: fermented milk, Glycyrrhiza glabra, Helicobacter pylori, Lactobacillus paracasei, probiotics

1. Introduction

Helicobacter pylori is a gram-negative spiral-shaped microaerophilic bacteria colonizing the human gastric epithelial cell with more than 50% prevalence and is associated with gastric malignancy as well as chronic atrophic gastritis and peptic ulcer.[1–3] The 1st-line standard regimen used for the eradication of H pylori infection is composed of 2 antibiotics and 1 proton-pump inhibitor (PPI).[4] Unfortunately, this triple therapy has limited efficacy because of antibiotic resistance of the pathogen and poor compliance due to adverse effects.[5] A large number of studies have been conducted to identify the optimal regimen for H pylori eradication; however, its success rate still remains challenging. Even though several studies have evaluated the effects of supplementation with probiotics or alternatives along with standard triple regimen in H pylori eradication,[6,7] no studies showed a beneficial effect in patients with H pylori infection.

Gut microflora may be involved in the pathophysiology of various diseases through immunoregulatory function.[8,9] Dysbiosis, that is, imbalance between the protective and harmful gut microbiome, could lead to stimulation of inflammatory response, dysfunction of the intestinal epithelium, and increased permeability of the mucosa. Therefore, probiotic supplementation might be useful for the management of inflammatory conditions. Recently, probiotics have been added in the treatment of H pylori infection, as it might reduce the adverse effects of antibiotics and improve the success rate of H pylori eradication.[8,10,11] Of these probiotic strains, the genera Lactobacillus has been the most frequently investigated for the anti-H pylori activity in animal studies.[12,13] The genus Lactobacillus can produce extracellular polysaccharides (EPSs),[14] which modulate the host's immune response by either stimulating or suppressing the response in inflammatory disorders.[15]Lactobacillus paracasei, which is one of the representative Lactobacillus strains producing large amounts of EPS,[16] has demonstrated positive effects on health and disease in many clinical trials,[17–26] such as improvement of symptoms in gastroenteritis,[18–20] colonic diverticulitis,[21,22] or irritable bowel syndrome[23] and lowering of serum triacylglycerol level.[24,25] Currently, L paracasei has been widely used as a single probiotic or in combination with other prebiotics.[26]

Glycyrrhiza glabra (licorice) has been traditionally used as a herbal medicine in various countries for many years.[27,28]G glabra has been reported for various clinical effects, such as antiinflammatory, antimicrobial, antiviral, antiprotozoal, antioxidative, hepatoprotective, anxiolytic, and even antitumor.[29] Furthermore, a root extract of G glabra is also reported to have favorable gastrointestinal effects, such as antiulcer activity, gastric epithelial cell protection, and gastrointestinal motility regulation.[30–32] In vitro, aqueous extract of G glabra suppressed H pylori activity through inhibiting the adhesion of H pylori to the gastric cells.[33,34]

In this study, we aimed to assess the efficacy and safety of fermented milk containing L paracasei HP7 and G glabra in patients with H pylori infection with a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study population

Patients between the ages of 19 and 70 years were eligible, if they were confirmed with H pylori infection by 13C-urea breath test (UBT), Campylobacter-like organism (CLO) test, or histologic examination (Giemsa or hematoxylin and eosin stain) within 1 year. Patients were excluded if they had used nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, corticosteroids, antimicrobials, acid-suppressing medications (such as PPIs and H2-blocker), bismuth compounds, or probiotics <2 weeks before the screening visit; had current active gastric or duodenal ulcer; had previous gastric malignancy; had alarm signs (e.g., abnormal weight loss, hematochezia, anemia, or significant bowel habit changes); had lactose intolerance; had uncontrolled comorbidity; were pregnant or breastfeeding; or were drug users or alcoholics. All enrolled patients received comprehensive information about this study, and informed consent was obtained before any study-related processes began. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of our hospital (KHNMC IRB 2017-02-003).

2.2. Study design

This multicenter, prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial was conducted at Kyung Hee University Hospital and Vievis Namuh Hospital from April to December 2017. After screening of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, enrolled patients were assigned with consecutive allocation numbers, which were matched at a 1:1 ratio to a randomization code through a table of random numbers. Subjects were randomized into either the treatment group (fermented milk with L paracasei HP7 and G glabra) or placebo group (fermented milk only) once daily for 8 weeks. The status of H pylori infection was determined by 13C-UBT, CLO test, and histopathologic examination by gastric biopsy just before intake of study products and at 8 weeks after completion of administration. The participants, nurses, and researchers involved in this study were blinded to the interventions until the final database lock.

2.3. Study products and compliance

The study product was 1 bottle (150 mL) of fermented milk with or without probiotics and licorice extract. The study product contained 1.0 × 106 CFU/mL L paracasei HP7 KCTC 13143BP as probiotics and 100 mg licorice extracted from deglycyrrhizinated roots and rhizomes of G glabra developed by Korea Yakult Co, Ltd (Seoul, South Korea). The placebo was prepared using the same ingredients, but without the L paracasei HP7 KCTC 13143BP and G glabra, and had identical packaging to that of the study product in the treatment group. One bottle (150 mL) of the study product was taken once daily at the same time every morning. During the study period, patients recorded the time of study product intake and adverse events in daily diaries. All unused products had to be returned to the study site, and compliance was calculated at 4- and 8-week follow-up visits. Poor compliance was defined as taking an average of <75% of bottles.

2.4. Assessments and study endpoints

The primary endpoint was the gastric load of H pylori assessed on the 8th week. Gastric load of H pylori was quantified using 13C-UBT. 13C-UBT was performed after 4 hours of fasting using the UBT kit (Crystal Life Science, Bundang, South Korea). The 50-mg 13C-urea was dissolved in water and then administered orally. Baseline and 30-minutes breath samples were assayed with an infrared spectrometer that produced computer-generated results. Positive results were defined as a computer-generated δ13CO2 value ≥2%, and negative results as <2%.[35] The secondary endpoints were histopathologic improvement assessed by the Sydney grading system, negative conversion of H pylori by the CLO test, and clinical improvement by 2 self-administered questionnaires.[36–38] This Sydney grading system categorized gastritis according to intensity of neutrophil activity, chronic inflammation by mononuclear inflammatory cellular infiltrates, mucosal atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, and H pylori density (no = 0, mild = 1, moderate = 2, severe = 3).[36,39] Four biopsy specimens were taken from both the lesser curvature (LC) and greater curvature (GC) sites of the antrum and corpus for histopathologic examination.[40] Four scores at each site were summed up and ranged from 0 to 12 points. To assess clinical improvement, gastrointestinal symptom rating scale (GSRS) and World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment Instrument (WHOQOL)-BREF questionnaires were used.[37,38,41] The GSRS questionnaire includes 15 questions, which assess severity of gastrointestinal symptoms using a 4-point Likert scale, from 0 to 3, in 5 domains: indigestion, diarrhea, constipation, abdominal pain, and reflux.[37] The symptom severity reported in the GSRS increases with increasing score. The WHOQOL-BREF has 26 items divided into 4 factor structures that include physical health, psychologic, social relationship, and environmental domains to measure a person's quality of life (QOL).[38,41]

2.5. Statistical analysis

The sample size was calculated assuming −2.91% quantitative change of 13C-UBT as the primary endpoint in the treatment group and −0.78% in the placebo group based on a previous study conducted under a similar setting.[42] We estimated that a sample size of 56 subjects per group would have a statistical power of 80% and a 2-sided α-risk of 0.05. We planned to enroll 70 subjects in each group, assuming a 20% dropout rate. Efficacy was assessed by per protocol analysis and safety by intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis. The ITT analysis included all participants who had taken at least 1 dose of study drugs.

In comparing the demographic factors between the 2 groups, continuous variables were analyzed using Student t-tests and categorical variables using Chi-squared or Fisher exact tests. To assess the quantitative changes of primary and secondary endpoints before and after the study period in both groups, paired t-tests were performed. To evaluate values between the 2 groups at each time point, Student t-tests were used. All statistical tests were 2 sided, and a P-value <.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using the SAS/STAT software (SAS 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

3. Results

3.1. Baseline characteristics

A total of 253 subjects were invited to participate in the study, and 111 subjects were ineligible as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. A total of 142 subjects consented and were enrolled in the study and then randomly allocated to the treatment group (n = 71) or placebo group (n = 71). After allocation, eight subjects in the treatment group were excluded because of prohibited medication use (n = 2), consent withdrawal (n = 2), newly confirmed pregnancy (n = 1), adverse event (n = 1), and poor compliance (n = 2). Six subjects in the placebo group were also excluded because of prohibited medication use (n = 3), newly detected gastric ulcer on gastroscopy (n = 2), and poor compliance (n = 1). Finally, 128 subjects (treatment group, n = 63; placebo group, n = 65) were analyzed (Fig. 1). For the baseline characteristics of the participants, age, sex, smoking, alcohol, occupation, and comorbidity were not different between the 2 groups (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Patient flow diagram.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study subjects in the treatment and placebo groups.

3.2. Histologic efficacy analysis

Compared to baseline data, the quantitative value of 13C-UBT at 8 weeks was significantly reduced in the treatment group (from 20.8 ± 13.2% to 16.9 ± 10.8%, P = .035), but not in the placebo group (from 19.1 ± 12.7% to 16.9 ± 11.8%, P = .130) (Table 2). However, no significant difference was observed between the 2 groups at baseline and 8 weeks. Two patients in the treatment group and 1 in the placebo group converted to negative status of H pylori infection measured by 13C-UBT after 8 weeks of administration, which was not significant (P = .616).

Table 2.

Efficacy analysis for viral load of the Helicobacter pylori infection before (0 week) and after (8 weeks) the treatment.

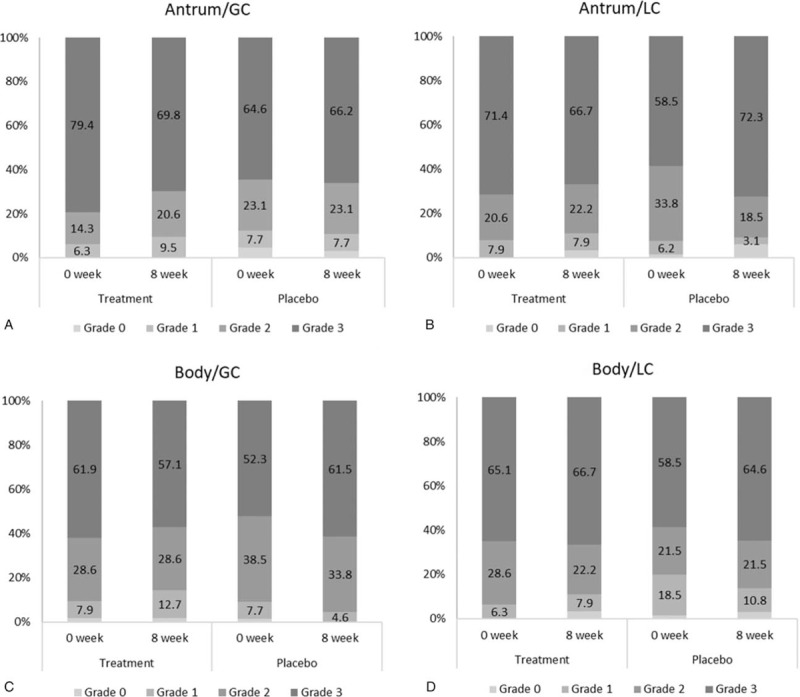

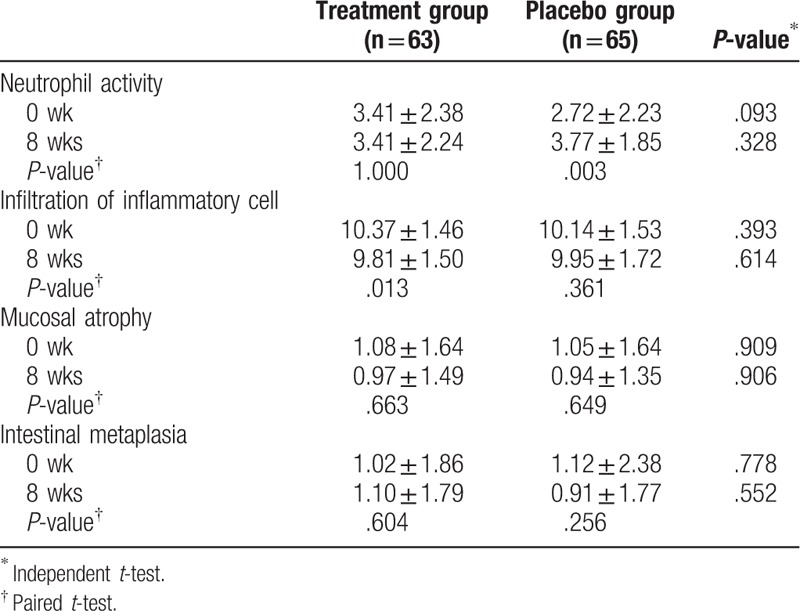

After 8 weeks of intervention, H pylori density on histologic examination showed no significant difference within and between groups in the total score of the Sydney classification (Table 2). In the subgroup analysis, severe inflammation (grade 3) decreased in the treatment group at the antrum/GC, antrum/LC, and body/GC (Fig. 2). However, severe inflammation (grade 3) rather increased in the placebo group at the antrum/GC, antrum/LC, body/GC, and body/LC (Fig. 2). In chronic inflammation judged from infiltration of inflammatory cell, the degree of inflammation improved significantly in the treatment group (P = .013), but not in the placebo group. The neutrophil activity deteriorated significantly in the placebo group (P = .003), but not in the treatment group. There was no significant alteration in mucosal atrophy and intestinal metaplasia in both groups (Table 3).

Figure 2.

The proportion (%) of Helicobacter pylori density divided by the Sydney classification on histopathologic examination at the (A) antrum/greater curvature (GC), (B) antrum/lesser curvature (LC), (C) body/greater curvature, and (D) body/lesser curvature before (0 week) and after (8 weeks) the treatment.

Table 3.

Histopathologic analysis of Helicobacter pylori infection before (0 week) and after (8 weeks) the treatment.

3.3. Clinical efficacy analysis

Overall gastrointestinal symptoms measured by GSRS improved significantly in the treatment group (from 2.6 ± 3.9 to 1.9 ± 2.6, P = .049), but not in the placebo group (from 3.2 ± 3.4 to 2.4 ± 2.8, P = .106) (Table 4). In the WHOQOL-BREF, the QOL score was significantly better in the physical health domain of the treatment group (P = .029); however, the QOL scores were not significantly improved in the psychologic, social relationship, and environmental domains. There was no significant improvement in all four domains of the placebo group. However, between the treatment and placebo groups over the study period, no significant differences were found for clinical symptoms measured by the GSRS and WHOQOL-BREF.

Table 4.

Clinical efficacy analysis before (0 week) and after (8 weeks) the treatment.

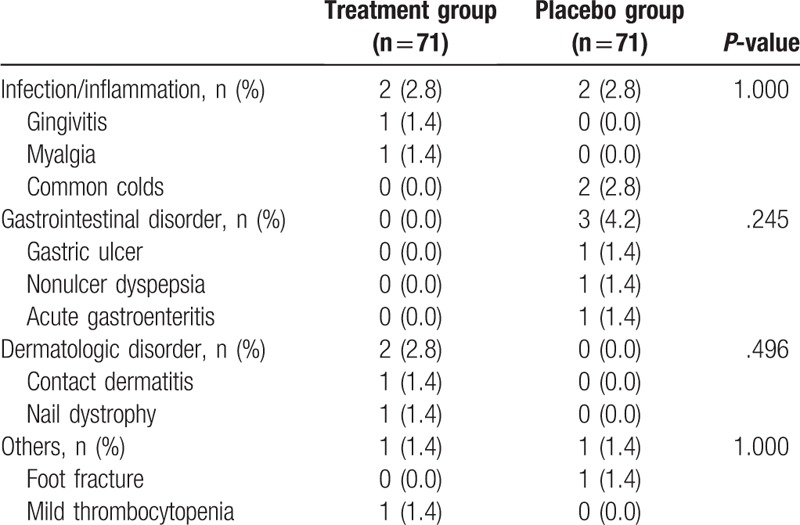

3.4. Safety and tolerability

Adverse events developed in five patients (7.0%) in the treatment group (n = 71) and in 6 (8.5%) in the placebo group (n = 71) without significant difference (P = .771) (Table 5). Common adverse events were minor infection/inflammation (5.6%), gastrointestinal disorders (4.2%), dermatologic disorders (2.8%), and others (2.8%), without significant difference between the 2 groups. All adverse events were mild in intensity without serious events, but one patient in the treatment group abandoned this trial because of allergic contact dermatitis, which has no direct association with this trial. The mean compliance rate was 98.2 ± 3.2% in the treatment group and 97.8 ± 4.5% in the placebo group (P = .509). Two patients in the treatment group and 1 patient in the placebo group showed poor compliance, defined as <75% intake rate (P = .509).

Table 5.

Adverse events reported over the entire treatment period through intention-to-treat analysis.

4. Discussions

The effects of probiotic supplementation along with the standard triple regimen have been evaluated in the management of H pylori.[43] Although several studies have reported the anti-H pylori activity of Lactobacillus alone in vitro or in experimental models, few human studies have evaluated their effects.[44–47] In the present study, the beneficial effect of fermented milk containing L paracasei HP7 and herbal extract (G glabra) for 8 weeks was evaluated as single agent in patients with H pylori infection. We showed reduction in H pylori urease activity and gastric inflammation only in the treatment group. In our study, severe inflammation significantly decreased and the degree of chronic inflammation significantly ameliorated only in the treatment group. Higher density of H pylori in the gastric mucosa is related to more severe gastritis and increased incidence of peptic ulcers; therefore, reduction of the density may suppress the development of pathologic conditions in the gastric mucosa.[48] Furthermore, our combination regimen also led to clinical improvement in gastrointestinal symptoms and QOL. Therefore, our study product may have a beneficial effect in patients with H pylori infection, as it reduced H pylori density detected by the quantitative assessment and improved histologic inflammation, even though it failed to eradicate H pylori.

The main pathogenesis of inflammation induced by H pylori is characterized by neutrophil infiltration into the epithelial cell layer.[49] Interleukin (IL)-8 is known as a key modulator, which initially leads to the migration and activation of neutrophils in H pylori-infected gastric epithelium.[50] After IL-8 expression, local release of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines also induced recruitment of monocytes and lymphocytes and increased H pylori attachment to the surface of the gastric epithelium.[50,51] Persistent inflammatory process caused by chronic H pylori infection might bring about mucosal damage, such as atrophic change, intestinal metaplasia, ulcer, and even cancer.

There is no golden standard in measuring H pylori load; however, 13C-UBT has been used as a quantitative assessment of H pylori density. In previous studies, H pylori load was measured indirectly by the UBT, because the bacterial urease activity is correlated with values of UBT.[52,53] Therefore, in our study, a decrease in UBT values in the treatment group could reflect a decrease in the H pylori bacterial load. H pylori load may be clinically important, as Tokunaga et al reported that the higher the increase in H pylori density, the greater the risk of H pylori-associated disease.[54] In contrast, we failed to show significant change in H pylori load measured by histopathologic examination. However, unequal distribution of H pylori in the gastric mucosa might make histopathologic examination less reliable than UBT in the measurement of H pylori density.[55]

The role of probiotics in the treatment of H pylori infection has been more widely known as a supplement to standard regimens than as a main therapy.[10,11,56,57] Currently, there are several clinical trials on probiotics alone to identify their anti-H pylori effect, as it may have beneficial effects on gastric H pylori through several possible mechanisms.[10,11] Probiotics may prevent colonization of H pylori by competing with H pylori for adhesion to the epithelium, strengthen gastric mucosal barrier by synthesizing antimicrobial compound, and stimulate mucin production.[58–60] Probiotics also reduce gastric activity and regulate the balance between proinflammatory and antiinflammatory cytokines.[13,61] Most effective strain of probiotics has not been determined yet for the management of H pylori infection, but Lactobacillus species showed proven efficacy because they are resistant to acidic environment, pancreatic enzyme, and bile salts and release lactic acid inhibiting the adhesion of H pylori to the cells.[43,62–64] In our study, L paracasei was used because it can produce a remarkable amount of lactic acid, which is regarded as the origin of anti-H pylori activity,[65] and has better immunomodulatory function in preventing intestinal inflammation than L plantarum or L rhamnosus.[16,66] Furthermore, L paracasei inhibited the elevation of IL-8 and regulated upon activation, normal T-cell expressed and presumably secreted (RANTES) released from the H pylori-infected gastric epithelium.[62,67]

In our study, severe inflammation (grade 3) improved dominantly in the antrum than in the corpus of the stomach after the 8-week treatment, which was consistent with previous findings where probiotics improved H pylori-induced histopathologic features predominantly in the antrum.[68] The gastric antrum is a major colonization site of H pylori as there are few acid-secretory parietal cells[48]; therefore, probiotics may have more beneficial effects in H pylori infection in the antrum than the body. The gut microbiome may be altered by a standard regimen for H pylori eradication including high-dose PPI and 2 antibiotics.[10] Previous meta-analysis about the role of probiotics in the H pylori eradication demonstrated that overall adverse effect rates significantly decreased with probiotics combination by stabilizing or restoring gut microflora.[6] In our study, general gastrointestinal symptoms measured by GSRS and QOL measured by WHOQOL-BREF improved significantly in the treatment group compared with those in the placebo group, which may be explained by the beneficial effect of probiotics on gut microbiota.

Glycyrrhiza glabra, commonly known as licorice, has been traditionally used to treat patients with peptic ulcers in Oriental medicine[27] and showed anti-H pylori and antiulcer activities in in vitro studies.[30,33,34,69] Aqueous extract from the roots of this plant was also reported to suppress H pylori activity through antiadhesion effects of H pylori to the gastric epithelium and antioxidative effects against gastric mucosal injury.[31,33,69] These results recently led to produce a commercial compound, namely GutGard, a flavonoid-rich root extract of G glabra.[42,69,70] Puram et al reported a 48% (24/50 subjects) H pylori eradication rate in patients taking 150 mg GutGard alone for 60 days compared with only 2% (1/50 subjects) H pylori eradication rate in the placebo group measured by 13C-UBT.[42] In our study, no eradication occurred in both treatment and placebo groups; however, H pylori bacterial load was decreased in the treatment group only. Further study is necessary to validate our findings as we used less dose of G glabra than that in the GutGard study.[42]

There were several limitations in this study. First, we could not evaluate the individual effect of probiotics or licorice because we did not perform a clinical trial to evaluate each of its efficacy. Second, we found only significant interval change in the intragroup analysis, but not in the intergroup analysis. This discrepancy may be explained by insufficient duration of therapy or the relatively small dosage. Previous studies reported that efficacy of probiotics could vary according to the duration of therapy; however, the optimal duration of therapy is still uncertain.[71,72] Third, we did not assess intestinal microbiome analysis results after administration of the study product. If fecal microbiome analysis is conducted, more information on altered composition by supplying L paracasei and G glabra can be gained. Lastly, we did not evaluate the effect of this combination as an adjunctive agent on improving H pylori eradication rates and ameliorating adverse events associated with the standard regimen. Furthermore, the role of this mixture in the prevention of clinical consequences related to H pylori infection requires further evaluation.

In conclusion, the combination of fermented milk containing L paracasei and G glabra reduced H pylori density and improved histologic inflammation. However, their mechanisms of action should be elucidated, and their role in the prevention of clinical consequences related to H pylori infection requires further evaluation.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Jae Myung Cha.

Data curation: Jin Young Yoon, Hyung Kyung Kim.

Formal analysis: Jin Young Yoon.

Investigation: Hyung Kyung Kim, Min Seob Kwak.

Methodology: Jung Won Jeon.

Resources: Min Seob Kwak, Jung Won Jeon, Hyun Phil Shin.

Supervision: Jae Myung Cha, Seong Soo Hong.

Writing – original draft: Jin Young Yoon.

Writing – review & editing: Jae Myung Cha.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CLO = Campylobacter-like organism, EPS = extracellular polysaccharide, GC = greater curvature, GSRS = gastrointestinal symptom rating scale, ITT = intention to treat, LC = lesser curvature, PPI = proton pump inhibitor, QOL = quality of life, UBT = urea breath test, WHOQOL = World Health Organization Quality of Life.

JMC and SSH contributed equally to this work as corresponding authors.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Suerbaum S, Michetti P. Helicobacter pylori infection. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1175–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lim SH, Kwon JW, Kim N, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of Helicobacter pylori infection in Korea: nationwide multicenter study over 13 years. BMC Gastroenterol 2013;13:104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hooi JKY, Lai WY, Ng WK, et al. Global prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2017;153:420–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kim SG, Jung HK, Lee HL, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection in Korea, 2013 revised edition. Korean J Gastroenterol 2013;62:3–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Gerrits MM, van Vliet AH, Kuipers EJ, et al. Helicobacter pylori and antimicrobial resistance: molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. Lancet Infect Dis 2006;6:699–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lu M, Yu S, Deng J, et al. Efficacy of probiotic supplementation therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One 2016;11:e0163743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ayala G, Escobedo-Hinojosa WI, de la Cruz-Herrera CF, et al. Exploring alternative treatments for Helicobacter pylori infection. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:1450–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Fuller R. Probiotics in human medicine. Gut 1991;32:439–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ng SC, Hart AL, Kamm MA, et al. Mechanisms of action of probiotics: recent advances. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2009;15:300–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Patel A, Shah N, Prajapati JB. Clinical application of probiotics in the treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection--a brief review. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2014;47:429–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lesbros-Pantoflickova D, Corthesy-Theulaz I, Blum AL. Helicobacter pylori and probiotics. J Nutr 2007;137:812S–8S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Aiba Y, Suzuki N, Kabir AM, et al. Lactic acid-mediated suppression of Helicobacter pylori by the oral administration of Lactobacillus salivarius as a probiotic in a gnotobiotic murine model. Am J Gastroenterol 1998;93:2097–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kabir AM, Aiba Y, Takagi A, et al. Prevention of Helicobacter pylori infection by lactobacilli in a gnotobiotic murine model. Gut 1997;41:49–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Sun Z, Harris HM, McCann A, et al. Expanding the biotechnology potential of lactobacilli through comparative genomics of 213 strains and associated genera. Nat Commun 2015;6:8322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Zannini E, Waters DM, Coffey A, et al. Production, properties, and industrial food application of lactic acid bacteria-derived exopolysaccharides. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2016;100:1121–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Mileti E, Matteoli G, Iliev ID, et al. Comparison of the immunomodulatory properties of three probiotic strains of Lactobacilli using complex culture systems: prediction for in vivo efficacy. PLoS One 2009;4:e7056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Morelli L, Zonenschain D, Callegari ML, et al. Assessment of a new synbiotic preparation in healthy volunteers: survival, persistence of probiotic strains and its effect on the indigenous flora. Nutr J 2003;2:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Vandenplas Y, De Hert SG, group PR-s. Randomised clinical trial: the synbiotic food supplement probiotical vs. placebo for acute gastroenteritis in children. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011;34:862–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Passariello A, Terrin G, Cecere G, et al. Randomised clinical trial: efficacy of a new synbiotic formulation containing Lactobacillus paracasei B21060 plus arabinogalactan and xilooligosaccharides in children with acute diarrhoea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2012;35:782–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Sarker SA, Sultana S, Fuchs GJ, et al. Lactobacillus paracasei strain ST11 has no effect on rotavirus but ameliorates the outcome of nonrotavirus diarrhea in children from Bangladesh. Pediatrics 2005;116:e221–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Morelli L, Garbagna N, Rizzello F, et al. In vivo association to human colon of Lactobacillus paracasei B21060: map from biopsies. Dig Liver Dis 2006;38:894–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Annibale B, Maconi G, Lahner E, et al. Efficacy of Lactobacillus paracasei sub. paracasei F19 on abdominal symptoms in patients with symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease: a pilot study. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol 2011;57:13–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Andriulli A, Neri M, Loguercio C, et al. Clinical trial on the efficacy of a new symbiotic formulation, Flortec, in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a multicenter, randomized study. J Clin Gastroenterol 2008;42:S218–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Rizzardini G, Eskesen D, Calder PC, et al. Evaluation of the immune benefits of two probiotic strains Bifidobacterium animalis ssp. lactis, BB-12(R) and Lactobacillus paracasei ssp. paracasei, L. casei 431(R) in an influenza vaccination model: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Br J Nutr 2012;107:876–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Bjerg AT, Kristensen M, Ritz C, et al. Four weeks supplementation with Lactobacillus paracasei subsp. paracasei L. casei W8(R) shows modest effect on triacylglycerol in young healthy adults. Benef Microbes 2015;6:29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ibnou-Zekri N, Blum S, Schiffrin EJ, et al. Divergent patterns of colonization and immune response elicited from two intestinal Lactobacillus strains that display similar properties in vitro. Infect Immun 2003;71:428–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Dastagir G, Rizvi MA. Review - Glycyrrhiza glabra L. (Liquorice). Pak J Pharm Sci 2016;29:1727–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Nazari S, Rameshrad M, Hosseinzadeh H. Toxicological effects of Glycyrrhiza glabra (Licorice): a review. Phytother Res 2017;31:1635–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Hosseinzadeh H, Nassiri-Asl M. Pharmacological effects of Glycyrrhiza spp. and its bioactive constituents: update and review. Phytother Res 2015;29:1868–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Aly AM, Al-Alousi L, Salem HA. Licorice: a possible anti-inflammatory and anti-ulcer drug. AAPS PharmSciTech 2005;6:E74–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Oh HM, Lee S, Park YN, et al. Ammonium glycyrrhizinate protects gastric epithelial cells from hydrogen peroxide-induced cell death. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2009;234:263–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Chen G, Zhu L, Liu Y, et al. Isoliquiritigenin, a flavonoid from licorice, plays a dual role in regulating gastrointestinal motility in vitro and in vivo. Phytother Res 2009;23:498–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Wittschier N, Faller G, Hensel A. Aqueous extracts and polysaccharides from liquorice roots (Glycyrrhiza glabra L.) inhibit adhesion of Helicobacter pylori to human gastric mucosa. J Ethnopharmacol 2009;125:218–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Asha MK, Debraj D, Prashanth D, et al. In vitro anti-Helicobacter pylori activity of a flavonoid rich extract of Glycyrrhiza glabra and its probable mechanisms of action. J Ethnopharmacol 2013;145:581–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Ferwana M, Abdulmajeed I, Alhajiahmed A, et al. Accuracy of urea breath test in Helicobacter pylori infection: meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2015;21:1305–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, et al. Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney system. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994. Am J Surg Pathol 1996;20:1161–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Svedlund J, Sjodin I, Dotevall G. GSRS--a clinical rating scale for gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and peptic ulcer disease. Dig Dis Sci 1988;33:129–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL): development and general psychometric properties. Soc Sci Med 1998;46:1569–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, et al. Histological classification of gastritis and Helicobacter pylori infection: an agreement at last? The International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis. Helicobacter 1997;2Suppl 1:S17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Kuo CH, Hu HM, Kuo FC, et al. Efficacy of levofloxacin-based rescue therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection after standard triple therapy: a randomized controlled trial. J Antimicrob Chemother 2009;63:1017–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Min SK, Lee CL, Kim KI, et al. Development of Korean version of WHO quality of life scale abbreviated version (WHOQOL-BREF). Korean J Neuropsyciatry Ass 2000;39:571–9. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Puram S, Suh HC, Kim SU, et al. Effect of GutGard in the management of Helicobacter pylori: a randomized double blind placebo controlled study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013;2013:263805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Zheng X, Lyu L, Mei Z. Lactobacillus-containing probiotic supplementation increases Helicobacter pylori eradication rate: evidence from a meta-analysis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2013;105:445–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Isobe H, Nishiyama A, Takano T, et al. Reduction of overall Helicobacter pylori colonization levels in the stomach of Mongolian gerbil by Lactobacillus johnsonii La1 (LC1) and its in vitro activities against H. pylori motility and adherence. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 2012;76:850–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Yang YJ, Chuang CC, Yang HB, et al. Lactobacillus acidophilus ameliorates H. pylori-induced gastric inflammation by inactivating the Smad7 and NFkappaB pathways. BMC Microbiol 2012;12:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Sunanliganon C, Thong-Ngam D, Tumwasorn S, et al. Lactobacillus plantarum B7 inhibits Helicobacter pylori growth and attenuates gastric inflammation. World J Gastroenterol 2012;18:2472–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Cui Y, Wang CL, Liu XW, et al. Two stomach-originated Lactobacillus strains improve Helicobacter pylori infected murine gastritis. World J Gastroenterol 2010;16:445–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Emara MH, Elhawari SA, Yousef S, et al. Emerging role of probiotics in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection: histopathologic perspectives. Helicobacter 2016;21:3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Kusters JG, van Vliet AH, Kuipers EJ. Pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Clin Microbiol Rev 2006;19:449–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Shimada T, Terano A. Chemokine expression in Helicobacter pylori-infected gastric mucosa. J Gastroenterol 1998;33:613–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Crabtree JE. Gastric mucosal inflammatory responses to Helicobacter pylori. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1996;10:29–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].De Francesco V, Zullo A, Perna F, et al. Helicobacter pylori antibiotic resistance and [13C]urea breath test values. J Med Microbiol 2010;59:588–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Kobayashi D, Eishi Y, Ohkusa T, et al. Gastric mucosal density of Helicobacter pylori estimated by real-time PCR compared with results of urea breath test and histological grading. J Med Microbiol 2002;51:305–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Tokunaga Y, Shirahase H, Hoppou T, et al. Density of Helicobacter pylori infection evaluated semiquantitatively in gastric cancer. J Clin Gastroenterol 2000;31:217–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Michetti P, Dorta G, Wiesel PH, et al. Effect of whey-based culture supernatant of Lactobacillus acidophilus (johnsonii) La1 on Helicobacter pylori infection in humans. Digestion 1999;60:203–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Graham DY, Fischbach L. Helicobacter pylori treatment in the era of increasing antibiotic resistance. Gut 2010;59:1143–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Talebi Bezmin Abadi A, Yamaoka Y. Helicobacter pylori therapy and clinical perspective. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2018;14:111–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Servin AL. Antagonistic activities of lactobacilli and bifidobacteria against microbial pathogens. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2004;28:405–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Sgouras D, Maragkoudakis P, Petraki K, et al. In vitro and in vivo inhibition of Helicobacter pylori by Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota. Appl Environ Microbiol 2004;70:518–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Gotteland M, Cruchet S, Verbeke S. Effect of Lactobacillus ingestion on the gastrointestinal mucosal barrier alterations induced by indometacin in humans. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2001;15:11–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Gill HS. Probiotics to enhance anti-infective defences in the gastrointestinal tract. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2003;17:755–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Takeda S, Igoshi K, Tsend-Ayush C, et al. Lactobacillus paracasei strain 06TCa19 suppresses inflammatory chemokine induced by Helicobacter pylori in human gastric epithelial cells. Hum Cell 2017;30:258–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Vesa T, Pochart P, Marteau P. Pharmacokinetics of Lactobacillus plantarum NCIMB 8826, Lactobacillus fermentum KLD, and Lactococcus lactis MG 1363 in the human gastrointestinal tract. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2000;14:823–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Fernandez MF, Boris S, Barbes C. Probiotic properties of human lactobacilli strains to be used in the gastrointestinal tract. J Appl Microbiol 2003;94:449–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Takeda S, Yamasaki K, Takeshita M, et al. The investigation of probiotic potential of lactic acid bacteria isolated from traditional Mongolian dairy products. Anim Sci J 2011;82:571–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Oliveira M, Bosco N, Perruisseau G, et al. Lactobacillus paracasei reduces intestinal inflammation in adoptive transfer mouse model of experimental colitis. Clin Dev Immunol 2011;2011:807483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].von der Weid T, Bulliard C, Schiffrin EJ. Induction by a lactic acid bacterium of a population of CD4(+) T cells with low proliferative capacity that produce transforming growth factor beta and interleukin-10. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 2001;8:695–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Pantoflickova D, Corthesy-Theulaz I, Dorta G, et al. Favourable effect of regular intake of fermented milk containing Lactobacillus johnsonii on Helicobacter pylori associated gastritis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2003;18:805–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Mukherjee M, Bhaskaran N, Srinath R, et al. Anti-ulcer and antioxidant activity of GutGard. Indian J Exp Biol 2010;48:269–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Raveendra KR, Jayachandra, Srinivasa V, et al. An extract of Glycyrrhiza glabra (GutGard) alleviates symptoms of functional dyspepsia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2012;2012:216970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Matsushima M, Takagi A. Is it effective?” to “How to use it?”: the era has changed in probiotics and functional food products against Helicobacter pylori infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;27:851–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Bell GD, Powell K, Burridge SM, et al. Experience with ’triple’ anti-Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy: side effects and the importance of testing the pre-treatment bacterial isolate for metronidazole resistance. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1992;6:427–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]