Abstract

Background:

Identifying factors that affect variation in health care spending among older adults with disabilities may reveal opportunities to better address their care needs while offsetting excess spending.

Objective:

To quantify differences in total Medicare spending among older adults with disability by whether they experience negative consequences due to inadequate support with household, mobility, or self-care activities.

Design:

Observational study of in-person interviews and linked Medicare claims.

Setting:

United States, 2015.

Participants:

3716 community-living older adults who participated in the 2015 National Health and Aging Trends Study and survived 12 months.

Measurements:

Total Medicare spending by spending quartile in multivariable regression models that adjust for individual characteristics.

Results:

Negative consequences were experienced by 18.3% of older adults with household disability, 25.6% with mobility disability, and 20.0% with self-care disability. Median Medicare spending was higher for those who experienced negative consequences with household ($4,866 vs. $4,095), mobility ($7,266 vs. $4,115) and self-care disability ($10,935 vs. $4,436) versus those who did not. In regression-adjusted analyses, differences in median spending did not vary appreciably for older adults who experienced negative consequences in household activities ($338: 95% CI: $−768-$1,444) but was greater for those with mobility ($2,309: 95% CI: $208-$4,409) and self-care disability ($3,187: 95% CI: $432-$5,942). At the bottom spending quartile, differences were observed for self-care only ($1,460: 95% CI: $358-$2,561). No differences were observed at the top spending quartile.

Limitations:

This observational study cannot establish causality.

Conclusion:

Inadequate support with mobility and self-care activities is associated with higher Medicare spending, especially at the middle and lower end of spending, which creates the possibility that better supporting the care needs of older adults could offset some Medicare spending.

Keywords: disability, Medicare spending, long-term services and supports

Nearly 15 million older Americans live in the community with disability. For these Americans, the availability and adequacy of support with daily activities has a profound effect on participation in valued activities, quality of life, and health (1–3). Older adults with disability are heavy users of services and incur high health care spending (4). Although adequacy of support with daily activities may affect health services use and spending, evidence is sparse. Prior studies rely on dated information collected from an earlier era involving a more institutionally-oriented service delivery environment and have been limited to examination of acute hospital and emergency department utilization (5–7): no studies to date have examined health care spending.

A better understanding of the association between adequacy of support with daily activities and health care spending is particularly important at this juncture. There is growing appreciation that the dominant health care payment paradigm prioritizes delivery of medical care rather than non-medical factors that affect root causes of health and well-being, such as housing, supportive services, or personal care that support function and the ability to safely perform daily activities (8, 9). However, recent payment and delivery reform efforts have sought to integrate medical and non-medical services to achieve better health and higher value care (10, 11). As potentially preventable health care spending is highly concentrated in a small subpopulation of frail older adults (12) this population is of high priority to payment and delivery reform (13, 14). Identifying factors that contribute to variation in health care spending may reveal opportunities to offset costs while better addressing older adults’ care needs.

This study draws on a national survey of older adults and linked Medicare claims to quantify differences in health care spending associated with adequate support with daily activities among community-living older adults with disability. We examine the consistency and magnitude of associations separately for those with limitations in household, mobility, and self-care activities as well as by spending quartile. By examining variability in Medicare spending for each activity domain across the spending distribution, we provide evidence for how health care spending is affected by factors in the broader social environment over and above the effects of demographic factors, diseases, and function and we identify sub-groups for which targeting outreach effort are most likely to be cost saving. In doing so, our study contributes insight regarding the potential magnitude of cost savings that could be derived from efforts that address both health and function by meeting older adults’ care needs.

METHODS

Study Sample

Our study draws on the 2015 National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) and linked Medicare files. NHATS is a nationally representative survey of Americans ages 65 and older that relies on Medicare enrollment files for its sampling frame. Annual in-person interviews are conducted with study participants or with proxy respondents if the participant is unable to respond. The analytic sample is drawn from 7,859 older adults who participated in the 2015 wave of NHATS. Due to greater availability of support in institutional settings, NHATS participants living in nursing homes (n=360) and residential care facilities (n=429) were excluded. We also excluded participants without Medicare Part B for the observation period (n=302). Due to the greater needs of persons nearing end of life, NHATS participants who died in the 12 months following interview (n=488) were excluded. Participants enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans (n=3137) were excluded due to lack of information about services use and spending. Spending was assessed from Medicare claims (inpatient, outpatient, skilled nursing facility, home health, hospice, carrier, durable medical equipment). Dates of Medicare Advantage enrollment and death were assessed from linked Medicare enrollment files. All other measures are from the NHATS. We begin with an analytic sample of 3,716 community-living older adults enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare who survived 12 months following interview. Analyses of interest focus on the subset of 1,961 study participants with one or more activity limitations, as defined below.

Measures

NHATS asks older adults to report how they perform daily activities using a recall period of one month. Questions are asked about household (laundry, shopping, meals, bills and banking), mobility (indoor and outdoor, transferring from bed), and self-care (eating, dressing, bathing, toileting) activities. For each activity, older adults are asked whether they receive help, and the level of difficulty if they performed the activity themselves. Receipt of help with self-care and mobility assistance is understood as being related to health or functioning whereas for household activities, participants are asked whether help was for health or functioning reasons. We constructed binary measures indicating limitations for each activity (e.g., eating) and activity domain (e.g. self-care). For each activity, participants receiving help or reporting difficulty were asked whether they experienced a specific negative consequence due to no one being available to provide help (if help was reported as being received) or the activity being too difficult to perform on their own (if difficulty was reported). Negative consequences included: going without clean clothes, going without groceries or personal items, going without a hot meal, going without handling bills and banking matters, making a mistake in taking medications, having to stay in bed, not being able to go places in their home or building, not being able to leave their home or building, going without eating, going without showering/bathing/washing up, accidentally wetting or soiling their clothes, and going without getting dressed (Table 1).

Table 1.

Negative Consequences Due to Inadequate Support with Daily Activities Among Community-Living Older Adults with Disability

| Disability by Activity and Domain |

Community-Living Older Adults with Disability | Negative Consequences | Percent Experiencing Negative Consequence |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (unweighted n) | (millions)* | (row %)* | ||

| Household Activities † | ||||

| Keeping track of medication | 581 | 2.7 | Made a mistake in taking prescribed medication‡(n=112) | 22.0 (17.4, 26.5) |

| Meal Preparation | 749 | 3.4 | Went without a hot meal (n=86) | 14.4 (11.3, 17.5) |

| Banking and paying bills | 605 | 2.4 | Bills were not paid (n=37) | 9.0 (5.8, 12.2) |

| Shopping | 934 | 4.3 | Went without groceries or personal items (n=54) | 6.2 (4.1, 8.2) |

| Laundry | 620 | 2.8 | Went without clean laundry (n=18) | 3.9 (1.7, 6.0) |

| Any Household Activity | 1438 | 7.0 | Negative Consequence, 1+ Activity (n=243) | 18.3 (15.9, 20.8) |

| Mobility Activities § | ||||

| Going outside the home | 769 | 3.4 | Had to stay inside (n=198) | 27.9 (24.2, 31.7) |

| Getting around inside home | 699 | 3.2 | Did not go places inside the home (n=169) | 24.3 (20.9, 27.8) |

| Getting out of bed | 767 | 3.8 | Had to stay in bed (n=55) | 6.6 (4.5, 8.8) |

| Any Mobility Activity | 1215 | 5.8 | Negative Consequence, 1+ Activity (n=321) | 25.6 (22.9, 28.3) |

| Self Care Activities § | ||||

| Toileting | 297 | 1.4 | Wet or soiled self (n=138) | 39.3 (32.8, 45.9) |

| Washing up | 604 | 2.6 | Went without showering, bathing, or washing up (n=62) | 13.1 (9.7, 16.4) |

| Dressing | 743 | 3.4 | Went without getting dressed (n=45) | 6.2 (4.1, 8.3) |

| Eating | 243 | 1.0 | Went without eating | ---∥ |

| Any Self-Care Activity | 981 | 4.5 | Negative Consequence, 1+ Activity (n=206) | 20.0 (17.4, 22.6) |

| Any Activity Domain | 1961 | 9.3 | Negative Consequence, Any Activity (n=569) | 28.6 (26.4, 30.8) |

Source: National Health and Aging Trends Study, 2015.

Data are weighted to reflect community-living Medicare beneficiaries ages 65 years enrolled in traditional Medicare who survived 12 months following interview. Estimates in the table focus on 1,961 participants with 1+ activity limitation.

Respondents were asked about negative consequences with household activities if they performed the activity with difficulty themselves or received help for health or functioning reasons.

Older adults who reported difficulty managing prescribed medications themselves, or who relied on someone else to manage medications for health and functioning reasons (n=581) were asked about mistakes. Those who always managed medications with someone else (n=55) were not asked about mistakes and excluded.

Respondents asked about negative consequences with mobility and self-care if they performed the activity with difficulty themselves, received help, or did not perform the activity.

Numbers not reportable due to small sample (n<11) but included in aggregated estimates.

Our primary outcome is the total amount paid by Medicare for all Part A and B reimbursed services in the 12 months following the 2015 NHATS community interview. From the NHATS we assess the following socio-demographic factors: age, sex, race, educational attainment, and TRICARE or Medigap supplemental insurance coverage. Medicaid status was defined as having any months of Medicaid enrollment in the Part D Medicare Master Beneficiary File. From the NHATS we assess the following measures of health: self-rated health, numbers of chronic medical conditions, and a composite measure of dementia(15). We additionally include a measure of received help for each activity domain, differentiating between no help, help from family or unpaid caregivers (regardless of paid help), or paid help only.

Data Analysis and Estimation

We first assess the prevalence of negative consequences with daily activities for each activity and by activity domain. We next examine characteristics of older adults by disability status and, for those with disability, by whether they experienced negative consequences with daily activities. Between-group differences by disability status and negative consequences are compared by activity domain using the Rao-Scott modified chi-square test for categorical variables and the Adjusted Wald Test for continuous measures. We then examine median annual Medicare spending for each subgroup of interest. In supplemental analyses we examine the percentage of each group with non-zero spending by type of service and median spending among users of services (Supplemental Appendix 1). Next, we construct quantile regression models to estimate the relationship between negative consequences and Medicare spending at the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles of the spending distribution. Regressions are separately performed for each activity domain (household activities, mobility, self-care) and we adjust for group differences in demographic factors, health, and experiencing negative consequences. We assess the effects of exclusion criteria by conducting separate sensitivity analyses with participants who otherwise met eligibility criteria but did not survive the observation period or lived in a residential care facility. Descriptive analyses were conducted in SAS 9.4 and Stata 12 using survey sampling weights, design variables, and procedures (proc surveyfreq; svy:means) that account for the complex sampling strategy. Multivariate quantile regression analyses were conducted using the qreg2 command in Stata 12, adjusting for variables related to NHATS sample criteria and clustering our standard errors at the level of the primary sampling unit to account for survey design features.

Role of the Funding Source:

This work was funded by the Commonwealth Fund and the National Institute on Aging. These funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study, the analysis and interpretation of the data, or in the review or approval of the manuscript.

RESULTS

Among community-living older adults with disability, the prevalence of experiencing negative consequences due to no one being available to help or the activity being too difficult to perform alone was variable by activity domain, and ranged from 18.3% for household activities, 20.0% for self-care, and 25.6% for mobility (Table 1). The most common negative consequences included wetting or soiling oneself when toileting (39.3%), having to stay inside (27.9%), not being able to go places inside the home (24.3%), and making mistakes in taking prescribed medications (22.0%).

Community-living older adults with disability were older and in worse health than those without disability (p<0.001 all contrasts, all domains; Table 2). Among older adults with mobility and self-care disability, those who experienced negative consequences due to inadequate support were more likely to be female, enrolled in Medicaid, to report worse self-rated health, and to have dementia and greater numbers of chronic conditions than their counterparts who did not experience negative consequences. Those who experienced negative consequences with household activities were younger, better educated, and reported worse self-rated health than their counterparts who did not experience negative consequences but otherwise few differences were observed. For all 3 activity domains, less than 5% of community-living older adults with disability exclusively relied on paid help, and of those experiencing negative consequences, most were receiving help from family and other unpaid caregivers.

Table 2.

Community Living Older Adults, Stratified by Disability and Negative Consequences with Daily Activities Due to Inadequate Support

| Older Adult Characteristics*,† |

Household Disability | Mobility Disability | Self-Care Disability | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None¶ | Negative Consequence** | None¶ | Negative Consequence** | None¶ | Negative Consequence** | |||||||

| No | Yes | P-Value | No | Yes | P-Value | No | Yes | P-Value | ||||

| Age in years (SE) | 73.8 (.1) | 76.8 (.3) | 75.6 (.5) | 0.041 | 74.0(.1) | 76.5(.3) | 77.2(.5) | 0.175 | 74.1 (.1) | 76.9 (.3) | 78.2 (.7) | 0.089 |

| Female gender, % | 52.0 | 61.1 | 60.1 | 0.83 | 53.3 | 56.9 | 67.2 | 0.017 | 54.1 | 56.4 | 66.3 | 0.014 |

| Race ‡, % | ||||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 87.0 | 82.0 | 81.3 | 0.95 | 87.1 | 82.9 | 74.0 | 0.002 | 86.6 | 80.6 | 80.2 | 0.99 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 6.0 | 8.0 | 8.6 | 5.9 | 8.4 | 10.1 | 6.0 | 9.1 | 9.3 | |||

| Other | 6.9 | 10.0 | 10.1 | 7.0 | 8.7 | 15.9 | 7.3 | 10.3 | 10.5 | |||

| < High School ‡, % | 11.1 | 19.8 | 13.6 | 0.020 | 11.3 | 18.4 | 23.7 | 0.131 | 12.0 | 19.1 | 20.9 | 0.62 |

| Supplemental Insurance, % | ||||||||||||

| Tri-Care or Military | 29.9 | 27.6 | 23.0 | 0.29 | 29.7 | 27.6 | 24.0 | 0.32 | 29.2 | 28.6 | 23.4 | 0.24 |

| MediGap | 72.1 | 64.1 | 66.9 | 0.50 | 71.6 | 65.9 | 59.3 | 0.057 | 71.2 | 63.8 | 63.9 | 0.97 |

| Medicaid | 7.2 | 16.6 | 20.7 | 0.188 | 7.3 | 15.7 | 29.3 | <0.001 | 7.7 | 17.8 | 33.3 | <0.001 |

| Perceived health status‡, % | ||||||||||||

| Excellent/very good | 60.3 | 24.1 | 17.7 | 0.028 | 58.3 | 24.0 | 8.9 | <0.001 | 55.2 | 23.3 | 11.3 | <0.001 |

| Good | 29.2 | 37.0 | 31.3 | 30.0 | 39.6 | 23.3 | 30.9 | 34.6 | 28.7 | |||

| Fair/poor | 10.58 | 38.9 | 51.0 | 11.7 | 36.4 | 67.7 | 13.9 | 42.1 | 60.1 | |||

| Probable dementia | 2.4 | 14.4 | 11.1 | 0.087 | 3.2 | 12.7 | 18.5 | 0.054 | 3.1 | 15.0 | 27.5 | 0.002 |

| No. chronic conditions§, ∥ | 2.18 (.0) | 3.31 (.1) | 3.44 (.1) | 0.37 | 2.24(.0) | 3.22(.1) | 4.05(.1) | <0.001 | 2.30 (.0) | 3.44 (.1) | 3.98 (.1) | <0.001 |

| Receives help, % | ||||||||||||

| No help | 95.9 | 44.0 | 39.9 | 0.037 | 91.9 | 51.6 | 15.5 | <0.001 | 91.5 | 34.8 | 11.8 | <0.001 |

| Family & unpaid help | 4.0 | 54.4 | 55.3 | 7.7 | 46.5 | 81.6 | 8.2 | 62.8 | 83.8 | |||

| Paid help only | ---†† | 1.6 | 4.8 | 0.3 | 1.9 | 2.9 | 0.3 | 2.4 | ---†† | |||

Source: National Health and Aging Trends Study, 2015; all estimates are weighted.

Community-living Medicare beneficiaries ages 65+ surviving 12 months and enrolled in traditional Medicare (n= 3716).

Household=laundry, shopping, meals, bills/banking; Mobility=indoor & outdoor, transferring from bed; Self-care=eating, dressing, bathing, toileting.

Observations with responses of “don’t know”, “refused”, or “not ascertained”; categorized as “white” (n=84), “High School” (n=76) and “poor” self-rated health (n=1).

Self or proxy response to physician diagnosis for: hypertension, heart attack, diabetes, osteoporosis, heart disease, depression, cancer, emphysema-asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, arthritis, stroke, vision impairment||, hearing impairment||, hip fracture.

Includes: “Cannot read newspaper” while wearing glasses or contact lenses; “Cannot use telephone for hearing” or deaf (with a hearing aid).

P - Values<0.001 for all contrasts between older adults without disability and with disability (with and without negative consequences) for domains of household activities (n=2,278 versus 1,438), mobility (n=2,501 versus 1,215), and self-care (n=2,735 versus 981).

Differences for older adults with disability who did and did not report negative consequences due to insufficient help for household activities (n= 1,195 versus 243), mobility (n=894 versus 321), and self-care (n=775 versus 206).

Numbers not reportable due to small sample (n<11).

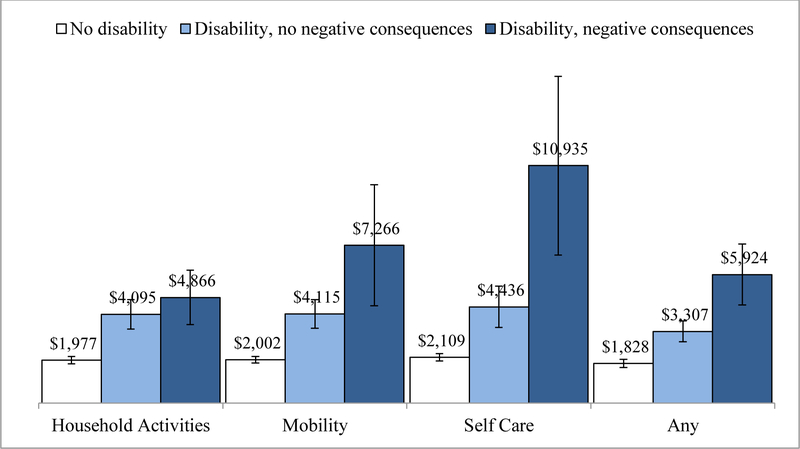

Median annual Medicare spending was higher for older adults with disability as compared with those who were not living with disability, although the magnitude of differences varied by activity domain (Figure 1). For all 3 activity domains, median annual Medicare spending was $2,000-$2,100 for older adults without disability. Among older adults with disability, median annual Medicare spending was higher for those who reported experiencing negative consequences due to inadequate support in household activities ($4,866 vs. $4,095), mobility ($7,266 vs. $4,115) and self-care ($10,935 vs. $4,436) as compared with their counterparts who did not experience negative consequences.

Figure 1. Median Medicare Spending for Community-Living Older Adults, Stratified by Disability and Whether they Experienced Negative Consequences Due to Inadequate Support.

Source: National Health and Aging Trends Study, 2015.

* Community-living Medicare beneficiaries ages 65+ who survive 12 months and are continuously enrolled in traditional Medicare (n= 3716)

† Household activities=laundry, shopping, meals, bills/banking; Mobility=indoor & outdoor, transferring from bed; Self-care=eating, dressing, bathing, toileting.

‡ Median annual Medicare spending, stratified by older adults’ disability status, and reports of experiencing negative consequences due to insufficient help with household activities (n=2278 1195, 243), mobility (n=2501, 894, 321), and self-care (n=2,735, 775, 206) as well as in any activity domain (n=1839, 1308, 569), respectively.

The association between experiencing negative consequences with daily activities and Medicare spending varied by activity domain and spending quartile in regression models that adjusted for demographic factors and health status (Table 3 and Supplemental Appendices 1–6). Among older adults with disability in household activities, Medicare spending did not vary appreciably by whether they experienced negative consequences. Among older adults with mobility disability, experiencing negative consequences was associated with additional spending of $2,309 (95% CI: $208-$4,409) at the 50th percentile of the spending distribution, but differences were not statistically significant at the bottom or top quartiles of spending. Among older adults with self-care disability, experiencing negative consequences was associated with additional spending of $1,460 (95% CI: $358-$2,561) at the bottom quartile and $3,186 (95% CI: $432-$5,942) at the 50th percentile of the spending distribution: differences at the top quartile were larger in magnitude but not statistically significant ($4,797, 95% CI: $−1,485-$11,079).

Table 3.

Additional Medicare Spending Related to Experiencing Negative Consequences with Daily Activities Among Community-Living Older Adults with Disability

| Quantile Regression (95% CI)¶, $ | ||

|---|---|---|

| 75% | ||

| 353 (−136, 842) | 338 (−768, 1444) | 363 (−2734, 3459) |

| 212 (−371, 795) | 2309 (208, 4409) | 1570 (−2318, 5458) |

| 1460 (358, 2561) | 3187 (432, 5942) | 4797 (−1485, 11079) |

Source: National Health and Aging Trends Study, 2015

Community-living Medicare beneficiaries ages 65+ who survive 12 months and continuously enrolled in traditional Medicare (n= 3716).

Household=laundry, shopping, meals, bills/banking; Mobility=indoor & outdoor, transferring from bed; Self-care=eating, dressing, bathing, toileting.

Group differences for those with disability who did and did not report negative consequences due to insufficient help with household activities (n= 1,195 versus 243), mobility (n=894 versus 321), and self-care (n=775 versus 206).

Models adjust for older adults’ age, gender, race, supplemental payer, self-rated health, dementia status, number of chronic conditions.

Estimates reflect the adjusted difference in Medicare spending associated with each characteristic at the specified spending quantile. Positive values reflect higher spending and negative values reflect lower spending while confidence intervals that overlap zero reflect differences that are not statistically significant. 95% confidence intervals based on standard errors clustered at the primary sampling unit to account for the NHATS design.

DISCUSSION

We find that community-living older adults with disability incur Medicare spending that is more than twice as high as their counterparts without disability, but that notable variability exists by activity domain and adequacy of support with daily activities. More than one in five older adults with mobility or self-care disability reported experiencing negative consequences due to no one being available to help or the activity being too difficult to perform alone. Median Medicare spending among these older adults was notably higher than for their counterparts who did not experience negative consequences – on the order of $2,300 for each person with mobility disability and $3,200 for each person with self-care disability. Taken together, our study confirms the foundational importance of adequate support with basic activities of daily living and contributes new information regarding how health care spending is affected by factors in the social environment over and above demographic characteristics, diseases, and function.

Our study quantifies spending on health services that could potentially be offset by better meeting the care needs of older Americans with disabilities and identifies subgroups for whom targeting outreach effort and expanded supports are most likely to be cost saving. That associations between higher Medicare spending and adequacy of support were strongest at the middle and lower end of the spending distribution suggests the potential for modifying health care spending through long-term services and supports may be more limited among those who incur the highest costs. This finding is consistent with prior evidence that acute health events and institutional services drive spending for high-need, high-cost populations (16–18).

The magnitude of additional spending on health services that was found to be associated with inadequate support with mobility and self-care activities at the middle and lower end of the spending distribution is not trivial. At an individual level, the additional Medicare spending on medical costs would be sufficient to absorb the majority if not all of the costs of delivering several evidence-based interventions that target function of older adults with disability and their families in the home (19–24). Assuming the estimated number of older Americans who reported experiencing negative consequences with mobility or self-care incurred additional spending at the median of the spending distribution, the incremental costs to Medicare would have exceeded $4 billion in 2015.

Prior studies find that frail older adults comprise a small segment of Medicare beneficiaries and account for a disproportionate proportion of program spending (12, 14), though to our knowledge this is the first study to assess the relevance of support with daily activities for Medicare spending. Results from our study are both timely and actionable. Potentially avoidable service use and excess health care spending are areas of longstanding concern (25, 26). Policy solutions have traditionally been directed at rationalizing payment across populations, geography, setting, and time (27–29). Our study contributes to an emerging body of evidence emphasizing the need to better coordinate health care and community-based long-term services and supports (30, 31) and the potential cost savings of assessing and addressing the care needs of high-risk sub-populations (32–35).

The health and human consequences of unmet care needs are most prevalent among persons who are socially and economically vulnerable (1, 2, 34) as found in this study. Medicaid is the largest payer of long-term services and supports, and states have been at the forefront of testing innovative models to meet the needs of the approximately 11 million Americans who are dually enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid (36, 37). Identifying effective strategies to care for this population is particularly pressing given traditional payment structures that have emphasized nursing home care, the movement to rebalance care to support community living, and anticipated growth in the numbers of persons living into older ages with more severe levels of disability in the decades to come (38–40). Findings from our study substantiate the importance of recent efforts in both Medicare and Medicaid to expand flexibility to address non-medical needs such as transportation, housing, and adult day care that are foundational to health and well-being (11, 41, 42). Effective targeting to ensure that additional benefits are directed to persons with high care needs who are most likely to benefit will be critical to the success of such efforts given prior evidence of the high demand (and thus, costs) of community-based services (43).

Our study confirms the heavy reliance on family and unpaid caregivers among persons with disabilities. Prior work indicates the availability and capacity of family and unpaid caregivers affects adequacy of support and services use (34, 44, 45). In this study, the majority of older adults who experienced negative consequences with daily activities were receiving help from family and other unpaid caregivers; few were receiving no help or paid help alone. In keeping with efforts to assess and address social needs through Medicare and Medicaid, recognizing and supporting the needs of family and other unpaid caregivers has been an area of active attention - in quality reporting of Managed Long-Term Services and Supports plans, in Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services care planning, in CMS Conditions of Participation for home health and hospice, and in new Medicare billing codes (45–47). Washington State’s Medicaid Transformation Waiver is a notable example of a state initiative that seeks to determine whether comprehensive support to unpaid family caregivers avoids or delays use of Medicaid-funded services among near-poor persons with disability (48–50). Our study suggests that if successful, this effort and others could have spillover effects for Medicare.

This study is not without limitations. Results may not generalize to Medicare beneficiaries less than 65 years of age or to those enrolled in Medicare Advantage or to the small segment of beneficiaries who do not select into Medicare Part B. Analyses are constrained to total Medicare spending as opposed to spending by service type or setting of care. We are not able to assess services paid out of pocket or reimbursed by other health care payers, such as the Department of Veterans Affairs or by Medicaid. We cannot discard the possibility of unmeasured confounding. As an observational, cross-sectional survey, we cannot definitively establish the causal processes through which adequacy of support with daily activities affects spending on health services or whether this process varies under specific circumstances, such as for a given health condition or health event. Nevertheless, adequate support with basic activities of daily living is foundational to a range of consequential processes and health events such as access to food, timely medical attention, and injurious falls – all of which have immediate and longer-term effects on health and services use (3, 51). Our finding that observed associations were stronger at the middle and lower ends of the spending distribution is consistent with prior evidence suggesting that catastrophic health events drive spending for Medicare beneficiaries with the highest costs, for whom only a small percentage of spending is preventable with greater supports or more coordinated outpatient care (14, 52).

The quality of home and community-based supports is complex and multidimensional, encompassing choice and control, dignity and respect, community inclusion, and equity (3, 53). This study evaluated a prescribed set of task-specific negative consequences that are linked to questions about daily activities that are posed in the National Health and Aging Trends Study rather than subjective perceptions of need which may be broader in scope. Likewise, we focus on Medicare spending for reimbursable health care services as opposed to broader outcomes relating to quality of life, quality of care, and work impacts that may be affected by the adequacy of supports and services available to persons with disability and their families.

In summary, results from this study find that Medicare spending is higher among older adults who are living in the community with disability and lack adequate support. Results suggest that the beneficial effects of comprehensive community-based long-term services and supports may extend beyond improved health, well-being, and participation to reduced spending on health services. Study findings suggest that efforts to address costs and quality of care may benefit from strategies that target both health and function. Identifying and implementing scalable strategies to better meet the care needs of community-living older adults with disability will only increase in the coming decades given population aging, constrained resources, and ongoing effort to rebalance care toward community living.

Supplementary Material

Primary Funding Source:

The Commonwealth Fund.

Grant support: This study was supported by grants from the Commonwealth Fund and the National Institute on Aging (U01AG032947 and R01AG047859). The sponsors of this research were not involved in its study concept or design, recruitment of subjects or acquisition of data, data analysis or interpretation, or in the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Reproducible research statement: Study protocol: Available from Dr. Wolff (e-mail, jwolff2@jhu.edu). Statistical code: Portions available on request. Please contact jmulcah2@jhu.edu with specific queries. Data set: NHATS is publicly available at www.nhats.org. Linked Medicare claims are not available from the authors; they are obtained and analyzed under a data-use agreement with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Contributor Information

Jennifer L. Wolff, Department of Health Policy and Management and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 624 North Broadway, Room 692, Baltimore, MD 21205

Lauren Hersch Nicholas, Department of Health Policy and Management and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 624 North Broadway, Room 450, Baltimore, MD 21205

Amber Willink, Department of Health Policy and Management and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 624 North Broadway, Room 698, Baltimore, MD 21205

John Mulcahy, Department of Health Policy and Management and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 624 North Broadway, Room 696, Baltimore, MD 21205.

Karen Davis, Department of Health Policy and Management and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 624 North Broadway, Room 690, Baltimore, MD 21205

Judith D. Kasper, Department of Health Policy and Management and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 624 North Broadway, Room 641, Baltimore, MD 21205

REFERENCES

- 1.Freedman VA, Spillman BC. Disability and care needs among older americans. Milbank Q. 2014;92(3):509–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen SM, Piette ER, Mor V. The adverse consequences of unmet need among older persons living in the community: dual-eligible versus Medicare-only beneficiaries. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2014;69 Suppl 1:S51–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.IOM. The Future of Disability in America. In: Field MJ, Jette AM, eds. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2007:618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayes SL, Salzberg CA, McCarthy D, Radley DC, Abrams MK, Shah T, et al. High-Need, High-Cost Patients: Who Are They and How Do They Use Health Care? A Population-Based Comparison of Demographics, Health Care Use, and Expenditures. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2016;26:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu H, Covinsky KE, Stallard E, Thomas J 3rd, Sands LP. Insufficient help for activity of daily living disabilities and risk of all-cause hospitalization. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60(5):927–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Depalma G, Xu H, Covinsky KE, Craig BA, Stallard E, Thomas J 3rd, et al. Hospital Readmission Among Older Adults Who Return Home With Unmet Need for ADL Disability. Gerontologist. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hass Z, DePalma G, Craig BA, Xu H, Sands LP. Unmet Need for Help With Activities of Daily Living Disabilities and Emergency Department Admissions Among Older Medicare Recipients. Gerontologist. 2017;57(2):206–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kindig DA, Asada Y, Booske B. A population health framework for setting national and state health goals. JAMA. 2008;299(17):2081–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bradley EH, Canavan M, Rogan E, Talbert-Slagle K, Ndumele C, Taylor L, et al. Variation In Health Outcomes: The Role Of Spending On Social Services, Public Health, And Health Care, 2000–09. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(5):760–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DHHS 2013;Pageshttp://www.ahrq.gov/workingforquality/nqs/nqs2013annlrpt.htm#improvequal on 6/20/2014.

- 11.Alley DE, Asomugha CN, Conway PH, Sanghavi DM. Accountable Health Communities--Addressing Social Needs through Medicare and Medicaid. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(1):8–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Figueroa JF, Joynt Maddox KE, Beaulieu N, Wild RC, Jha AK. Concentration of Potentially Preventable Spending Among High-Cost Medicare Subpopulations: An Observational Study. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(10):706–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blumenthal D, Chernof B, Fulmer T, Lumpkin J, Selberg J. Caring for High-Need, High-Cost Patients - An Urgent Priority. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(10):909–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joynt KE, Figueroa JF, Beaulieu N, Wild RC, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Segmenting high-cost Medicare patients into potentially actionable cohorts. Healthc (Amst). 2017;5(1–2):62–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kasper JD, Freedman VA, Spillman BC. Classification of Persons by Dementia Status in the National Health and Aging Trends Study: Technical Paper #5. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitra S, Findley PA, Sambamoorthi U. Health care expenditures of living with a disability: total expenditures, out-of-pocket expenses, and burden, 1996 to 2004. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(9):1532–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wodchis WP, Austin PC, Henry DA. A 3-year study of high-cost users of health care. CMAJ. 2016;188(3):182–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen J, Vargas-Bustamante A, Mortensen K, Thomas SB. Using quantile regression to examine health care expenditures during the Great Recession. Health Serv Res. 2014;49(2):705–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szanton SL, Alfonso YN, Leff B, Guralnik J, Wolff JL, Stockwell I, et al. Medicaid Cost Savings of a Preventive Home Visit Program for Disabled Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(3):614–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jennings LA, Laffan AM, Schlissel AC, Colligan E, Tan Z, Wenger NS, et al. Health Care Utilization and Cost Outcomes of a Comprehensive Dementia Care Program for Medicare Beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jutkowitz E, Gitlin LN, Pizzi LT, Lee E, Dennis MP. Cost effectiveness of a home-based intervention that helps functionally vulnerable older adults age in place at home. J Aging Res. 2012;2012:680265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Samus QM, Johnston D, Black BS, Hess E, Lyman C, Vavilikolanu A, et al. A multidimensional home-based care coordination intervention for elders with memory disorders: the Maximizing Independence at Home (MIND) pilot randomized trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22(4):398–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nichols LO, Martindale-Adams J, Zhu CW, Kaplan EK, Zuber JK, Waters TM. Impact of the REACH II and REACH VA Dementia Caregiver Interventions on Healthcare Costs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(5):931–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Counsell SR, Callahan CM, Tu W, Stump TE, Arling GW. Cost analysis of the Geriatric Resources for Assessment and Care of Elders care management intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(8):1420–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zuckerman RB, Sheingold SH, Orav EJ, Ruhter J, Epstein AM. Readmissions, Observation, and the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(16):1543–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Werner RM, Konetzka RT. Trends in Post-Acute Care Use Among Medicare Beneficiaries: 2000 to 2015. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1616–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.IOM. Variation in health care spending: Target decision making, not geography. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McWilliams JM, Gilstrap LG, Stevenson DG, Chernew ME, Huskamp HA, Grabowski DC. Changes in Postacute Care in the Medicare Shared Savings Program. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(4):518–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mor V, Intrator O, Feng Z, Grabowski D. The revolving door of rehospitalization from skilled nursing facilities. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(1):57–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boyd CM, Leff B, Bellantoni J, Rana N, Wolff JL, Roth DL, et al. Interactions Between Physicians and Skilled Home Health Care Agencies in the Certification of Medicare Beneficiaries’ Plans of Care: Results of a Nationally Representative Survey. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(10):695–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Auerbach AD, Kripalani S, Vasilevskis EE, Sehgal N, Lindenauer PK, Metlay JP, et al. Preventability and Causes of Readmissions in a National Cohort of General Medicine Patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(4):484–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lage DE, Jernigan MC, Chang Y, Grabowski DC, Hsu J, Metlay JP, et al. Living Alone and Discharge to Skilled Nursing Facility Care after Hospitalization in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(1):100–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosati RJ, Russell D, Peng T, Brickner C, Kurowski D, Christopher MA, et al. Medicare home health payment reform may jeopardize access for clinically complex and socially vulnerable patients. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(6):946–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beach SR, Schulz R. Family Caregiver Factors Associated with Unmet Needs for Care of Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(3):560–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ash AS, Mick EO, Ellis RP, Kiefe CI, Allison JJ, Clark MA. Social Determinants of Health in Managed Care Payment Formulas. JAMA Intern Med. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.MedPAC, MacPAC. Beneficiaries dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eiken S, Sredl K, Burwell B, Amos A. Medicaid Expenditures for Long-Term Services and Supports (LTSS) in FY 2016. . Washington, DC: IBM Watson Health; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim H, Charlesworth CJ, McConnell KJ, Valentine JB, Grabowski DC. Comparing Care for Dual-Eligibles Across Coverage Models: Empirical Evidence From Oregon. Med Care Res Rev. 2017:1077558717740206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grabowski D Medicare and Medicaid: conflicting incentives for long-term care. Milbank Q. 2007;85(4):579–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaye HS. Gradual rebalancing of Medicaid long-term services and supports saves money and serves more people, statistical model shows. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(6):1195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Willink A, DuGoff EH. Integrating Medical and Nonmedical Services - The Promise and Pitfalls of the CHRONIC Care Act. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(23):2153–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lewis E, Eiken S, Amos A, Saucier P. The Growth of Managed Long-Term Services and Supports: 2017 Update. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weissert W Seven reasons why it is so difficult to make community-based long-term care cost-effective. Health Serv Res. 1985;20(4):423–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wolff JL, Mulcahy J, Roth DL, Cenzer IS, Kasper JD, Covinsky K. Long-term nursing home entry: A prognostic model for older adults with a family or unpaid caregiver. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(10):1887–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.NASEM. Families Caring for an Aging America. Washington, DC: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 46.CMS. Measures for Medicaid Managed Long Term Services and Supports Plans: Technical Specifications and Resource Manual. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shugrue N, Kellett K, Gruman C, Tomisek A, Straker J, Kunkel S, et al. Progress and Policy Opportunities in Family Caregiver Assessment: Results From a National Survey. J Appl Gerontol. 2017:733464817733104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Authority WHC 2018;Pageshttps://www.hca.wa.gov/about-hca/healthier-washington/initiative-2-long-term-services-and-supports2018.

- 49.Musameci MB, Rudowitz R, Hinton E, Antonisse L, Hall C 2018;Pages. Accessed at Kaiser Family Foundation at https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/section-1115-medicaid-demonstration-waivers-the-current-landscape-of-approved-and-pending-waivers/ on 7/4/2018.

- 50.Lavelle B, Mancuso M, Huber A, Felver BEM. Expanding eligibility for the family caregiver support program in SFY 2012 RDA Report 8.31 Olympia, WA; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 51.WHO. Towards a common language for functioning, disability, and health: ICF. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Joynt KE, Gawande AA, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Contribution of preventable acute care spending to total spending for high-cost Medicare patients. JAMA. 2013;309(24):2572–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.NQF. Addressing performance measure gaps in home and community based services to support community living. Washington DC; 2015. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.