Abstract

Background:

Dolutegravir is superior to efavirenz for HIV antiretroviral therapy (ART), but may be associated with an increased risk of neural tube defects (NTDs) in newborns if used by women at conception.

Objective:

To project clinical outcomes of ART policies for women of childbearing potential in South Africa.

Design:

Model of 3 strategies: efavirenz (EFV) for all, dolutegravir (DTG) for all, or World Health Organization-recommended efavirenz without contraception or dolutegravir with contraception (WHO approach).

Data Sources:

Published data about NTD risks (efavirenz: 0.05%, dolutegravir: 0.67%, Tsepamo study), 48-week ART efficacy with initiation (efavirenz: 60–91%, dolutegravir: 96%), and age-stratified fertility rates (2–139/1,000 women).

Target Population:

3.1 million South African women with HIV (age 15 to 49 years) starting or continuing first-line ART, and their children.

Time Horizon:

5 years

Perspective:

Societal

Interventions:

EFV, DTG, and WHO approach

Outcome Measures:

Deaths among women and children, sexual and pediatric HIV transmissions, and NTDs.

Results of Base-Case Analysis:

Compared to EFV, DTG averted 13,700 women’s deaths (0.44% decrease) and 57,700 sexual HIV transmissions, but increased total pediatric deaths by 4,400 due to more NTDs. WHO approach offered some benefits compared to EFV, averting 4,900 women’s deaths and 20,500 sexual transmissions, while adding 300 pediatric deaths. Overall combined deaths among women and children were lowest with DTG (358,000) compared to WHO approach (362,800) or EFV (367,300).

Results of Sensitivity Analyses:

Women’s deaths averted with DTG exceeded pediatric deaths added with EFV unless dolutegravir-associated NTD risk was ≥1.5%.

Limitations:

Uncertainty in NTD risks and dolutegravir efficacy in resource-limited settings, each examined in sensitivity analyses.

Conclusion:

Though NTD risks may be higher with dolutegravir than efavirenz, dolutegravir will lead to many fewer deaths among women, and fewer overall HIV transmissions. These results argue against a uniform policy of avoiding dolutegravir in women of childbearing potential.

Keywords: Dolutegravir, efavirenz, neural tube defects, HIV, perinatal transmission

INTRODUCTION

Dolutegravir-based antiretroviral therapy (ART) for people with HIV offers superior efficacy and tolerability compared to the World Health Organization (WHO) longstanding recommendation of efavirenz-based ART as the preferred first-line regimen (1–3). Recent cost negotiations yielding a price of ~$75/person/year make dolutegravir more affordable in resource-limited settings; its global roll-out has been widely anticipated (1, 4, 5). Enthusiasm for dolutegravir was tempered for women of childbearing potential in May 2018, when preliminary data from the Tsepamo study revealed a higher risk of neural tube defects (NTDs; 4/426 infants, 0.94%) in infants born to women who conceived while taking dolutegravir than in infants born to women on efavirenz (0.05%) (6–8). Soon thereafter, the WHO released interim guidance that included dolutegravir-based ART as preferred first-line therapy; however, efavirenz was recommended as a safe and effective alternative for women of childbearing potential desiring pregnancy or lacking access to “consistent and reliable contraception” (1).

NTDs result in substantial morbidity and 75–100% mortality in resource-limited settings (9). From public health, but also clinical and patient perspectives, the risks of NTDs potentially attributable to dolutegravir should be weighed against the benefits conveyed by dolutegravir over efavirenz. Dolutegravir is likely to increase sustained virologic suppression, thereby improving outcomes for women and reducing HIV transmission (3, 10, 11). While recommending dolutegravir for women using contraception would increase access to this therapy for some women, inadequate access to reproductive health services will be a barrier for others (12–14). Policymakers in resource-limited settings may face challenges implementing the WHO guidance, including increased demand for reproductive health services, drug procurement difficulties with multiple first-line ART options, and inadequate provider time and training to discuss an informed choice of ART with women. Therefore, guidelines in some countries (e.g., Kenya and Malawi) may continue to recommend efavirenz for all women of childbearing age, while others (e.g. Zimbabwe) may allow women the choice of dolutegravir (15). To inform this important discussion, we examined clinical trade-offs of ART policies for women of childbearing potential in South Africa using published and validated mathematical models of HIV disease (16–20).

METHODS

We conducted a series of model-based analyses in South Africa over a five-year horizon, examining several outcomes: 1) clinical and sexual transmission outcomes for women of childbearing potential taking or initiating first-line ART; 2) anticipated live births among such women, including projected number of children with NTDs; and 3) clinical outcomes of the children, including overall and HIV-free survival and rates of HIV infection. Together, these outcomes provide a picture of the public health trade-offs of a country-wide policy of efavirenz for all women of childbearing potential, dolutegravir for all, or WHO guideline-concordant use of both, depending upon access to and intended use of effective contraception.

Published data sources were used to derive model inputs (Appendix Tables A2 and A3). We reviewed the published literature (PubMed, EMBASE, and Web of Science; September 25, 2018) and conference abstracts (CROI, International AIDS Society Meeting, and IDWeek 2017–2018), to identify randomized clinical trials that reported 48- and/or 96-week virologic suppression (HIV RNA <50 c/mL) with dolutegravir or efavirenz in combination with two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (Appendix Table A3). Studies that enrolled only tuberculosis co-infected subjects, used stavudine or didanosine, did not exclude pre-treatment drug resistance (PTDR), or omitted reasons for study withdrawal were excluded. Estimates were pooled and weighted by study size to inform 48- and 96-week ART efficacy and discontinuation due to adverse events. Subjects withdrawn due to loss to follow-up, mortality, or adverse events were censored to avoid double-counting these events, which are simulated elsewhere in the model (Appendix). We assumed that an adverse event on first-line ART prompts immediate switch to a protease inhibitor-based regimen without viral rebound, and we tested this assumption in sensitivity analyses.

Modeled Cohort Definition

The modeled cohort of women included three subcohorts reflecting present-day HIV treatment status: ART-naïve women initiating ART (New ART starts), women currently on first-line efavirenz-based ART and virologically suppressed (ART-experienced-suppressed), and women currently on first-line efavirenz-based ART and not virologically suppressed (ART-experienced-not suppressed; Appendix Figures A1 and A2). Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) estimates for South Africa in 2017 informed the number of women of childbearing potential (15–49y) in each subcohort: 219,300 new ART starts (in each year of the simulation), 1,562,600 ART-experienced-suppressed, and 440,700 ART-experienced-not suppressed, for a total of 3,099,800 women estimated to ever be on first-line ART over the next five years (Table A1) (21). In all subcohorts, 24–40% of women were modeled as using long-acting contraception, with 0.05–6% annual contraceptive failure rate that varied by method (22, 23).

Modeled Strategies

We compared three strategies: 1) initiation or continuation of first-line efavirenz-based ART (EFV), 2) initiation of (for New ART starts) or switch to (for ART-experienced) first-line dolutegravir-based ART (DTG), or 3) WHO guideline-concordant initiation or continuation of efavirenz-based ART for women not using long-acting contraception and initiation of or switch to dolutegravir-based ART for women using long-acting contraception (WHO approach) (1, 15). Outcomes in the WHO approach strategy were calculated as a weighted average of the DTG and EFV strategies based on contraceptive use.

Projecting Outcomes for Women of Childbearing Potential

We used the Cost-effectiveness of Preventing AIDS Complications (CEPAC)-International model of HIV disease to simulate a cohort of women with HIV of childbearing potential (Appendix) (16–18). Women in the model are assigned health states which depend on the degree of immunologic suppression or ART-related reconstitution (CD4) and virologic suppression or rebound (HIV RNA). Women start the model in one of the three subcohorts: New ART starts (mean CD4 0.354 × 10^9 cells/L); ART-experienced-suppressed (0.634 × 10^9 cells/L), and ART-experienced-not suppressed (0.634 × 10^9 cells/L), each with distinct ART efficacy parameterization (Table 1) (24, 25). All modeled women undergo viral load monitoring in accordance with WHO guidelines (26) (Appendix). In all subcohorts, upon diagnosed viremia, women have one opportunity for “re-suppression” on first-line ART after adherence counseling, followed by a switch to a second-line protease inhibitor-based ART regimen if viremia persists (Appendix Figure A2).

Table 1:

Input parameters for an analysis of clinical outcomes of women and children comparing efavirenz- and dolutegravir-based ART for first-line treatment of HIV in South Africa.

| Parameters for Women with HIV | Base Case | Range Examined | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Starting CD4 count (mean, 10^9 cells/L)– | |||

| New ART starts / ART-experienced | 0.354 / 0.634 | (24, 25)a | |

| NNRTI pre-treatment drug resistance, % | 10.7 | 0–30 | (27) |

| ART discontinuation due to early adverse events, %b,c | EFV: 0–8 | 4–19 | (2, 28–30) |

| DTG: 2–4 | 0–4 | (2, 31–34) | |

| ART efficacy – % Virologic suppression at 48 wksd,e | |||

| New ART starts – NNRTI PTDR-b | EFV: 91 | 76–100 | (2, 28–30, 35) |

| DTG: 96 | 95–98 | (2, 32, 33, 36) | |

| New ART starts – NNRTI PTDR+b, | EFV: 60 | 20–80 | (37–40) |

| DTG: 96 | 95–98 | (2, 32, 33, 36) | |

| ART-experienced-suppressed | EFV: 100f | Assumption | |

| DTG: 97 | 96–98 | (31, 34) | |

| ART-experienced-not suppressed | EFV: 0 | Assumption | |

| DTG: 84 | 78–90 | (41, 42) | |

| Second-line protease inhibitor-based ART | 75 | (43) | |

| Re-suppression after first-line treatment failure, % | 45 | 19–88 | (44–48) |

| Sexual transmissions – rate/100 person-years (by HIV RNA) | 0.16–9.03 | (0.5–2X) | (10, 23, 49) |

| Use of long-acting contraception (range by age)g | 24–40% | (23) | |

| Failure rates of long-acting contraception (range by contraceptive method)h | 0.05–6.00% | (22) | |

| Pediatric Parameters | |||

| Breastfed infants, % | 80 | (50–52) | |

| Breastfeeding duration, mean (SD), in mo. | 6 (6) | (52) | |

| Neural tube defects in live births, % | EFV: 0.05 | (6, 8) | |

| DTG: 0.67 | (0.1–2.0) | ||

| Mortality with neural tube defect, % | 100 | Assumption based on (9) | |

| Pediatric HIV infection risksb | |||

| IU/IP – On ART, virologically suppressed, % | 0.25 | (0.5–2X) | (11, 53, 54) |

| IU/IP – On ART, not suppressed, % | 4.64 | (0.5–2X) | (11, 53, 54) |

| IU/IP – Not on ART, % (range by CD4) | 17–27 | (55–57) | |

| PP – On ART, virologically suppressed, %/mo. | 0.05 | (0.5–2X) | (58, 59) |

| PP – On ART, not suppressed, %/mo. | 0.29 | (0.5–2X) | (58, 59) |

| PP – Not on ART, %/mo. (range by CD4) | 0.24–1.28 | (56, 57, 60) | |

ART: antiretroviral therapy, NNRTI: non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, PTDR: pre-treatment drug resistance, EFV: efavirenz strategy, DTG: dolutegravir strategy, SD: standard deviation, IU: intrauterine, IP: intrapartum, PP: postpartum.

The mean CD4 count at model start for ART-experienced women was from CEPAC-generated CD4 count projections of women who had been on efavirenz-based ART for a mean of 34 months (25).

Additional studies informing these inputs are detailed in the Appendix.

Adverse events prompt transition from first-line ART to a protease inhibitor-based regimen without intervening viral rebound.

Most publications of clinical trials count loss to follow up, protocol deviation, consent withdrawal, and discontinuation due to mortality as virologic failures. However, these events are accounted for separately in the model. Therefore, we extract these parameters from our calculation of virologic suppression to calculate as-treated values of HIV RNA suppression to <50 c/ml and avoid double counting in the model. See the Appendix for details.

The 48-week ART efficacy in the DTG new ART starts subcohort was informed by trials involving ART-naïve subjects; ART efficacy data for ART-experienced individuals were taken from switch studies (ART-experienced-suppressed) and from studies of second-line dolutegravir-based ART among treatment experienced subjects (ART-experienced-not suppressed).

In the EFV strategy, women in the ART-experienced-suppressed subcohort who were continued on efavirenz-based ART started with 100% probability of virologic suppression by definition, but then were immediately eligible for a monthly risk of late treatment failure. See the Appendix for details.

Long-acting contraception includes: female or male sterilization, intrauterine devices, injectable contraceptives, or implants.

Failure rates reflect the percent of women who experience an unintended pregnancy within the first year of typical use (22).

ART efficacy and adverse event rates varied by strategy and subcohort (Table 1, Appendix Table A2–6). We modeled 10.7% non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) PTDR leading to reduced efficacy of efavirenz in South Africa where resistance testing is not uniformally performed (27). We calculated first-order sexual transmissions using projected monthly estimates of the number of women in each HIV RNA stratum, multiplied by stratum-specific transmission rates (range 0.16–9.03 transmissions/100 person-years), with a 29% transmission reduction reflecting condom use (10, 16, 49, 61).)

For each strategy, we projected the following clinical outcomes for women over five years: number suppressed on ART, cumulative severe opportunistic infections (OIs), deaths, and first-order sexual transmissions; we then calculated the difference in these outcomes in three pairwise comparisons: DTG versus EFV, WHO approach versus EFV, and DTG versus WHO approach.

Projecting Live Births and NTDs

To project anticipated live births over five years for each strategy, we combined age-stratified fertility rates among women of childbearing potential (2–139 live births/1000 women/year) (23) with age-stratified cohort sizes based on HIV prevalence and then adjusted for CEPAC-derived maternal mortality (61). Based on the most recent Tsepamo estimates from July 2018, we assumed that children born to women taking dolutegravir had a 0.67% risk of NTDs, versus 0.05% with all other ART regimens (6, 8). With a 95% NTD mortality in sub-Saharan Africa (9), we assumed a 100% mortality in this population.

Infant Health Outcomes

We simulated peri- and postnatal HIV transmission with risks stratified by maternal ART use, CD4 count, and virologic suppression (Table 1) (11, 53, 56, 57, 60). We projected pediatric outcomes using the CEPAC-Pediatric model, incorporating the impact of HIV exposure and infection on mortality, as well as disease progression, diagnosis, and treatment for HIV-infected children (19). Outcomes included HIV transmissions and overall and HIV-free pediatric survival (further details at https://www.massgeneral.org/mpec/cepac/).

Sensitivity and Scenario Analyses

We evaluated whether the results were robust to changes in key parameters and assumptions, and generalizable to alternative settings, focusing sensitivity analyses on the EFV and DTG strategies (for others, see Appendix). In univariate analyses, we examined the impact of the following inputs on relevant outcomes: NNRTI PTDR, new ART starts annually, fertility rate, ART efficacy among new ART starts, sexual transmission rates, and peri- and postnatal transmission risks for women on ART. Given the substantial uncertainty around dolutegravir-associated NTD risks, we varied this parameter widely, intentionally beyond the Tsepamo study 95% confidence limits (6, 8). In multivariate analyses, we simultaneously varied influential parameters on deaths among women with HIV and their children: NNRTI PTDR, dolutegravir-associated NTD risk, fertility rates, and new ART starts annually. Finally, we created a scenario analysis with associated univariate sensitivity analyses using data from the New Antiretroviral and Monitoring Strategies in HIV-infected Adults in Low-income countries (NAMSAL) trial (62), assuming equal 48-week ART efficacy for new ART starts with dolutegravir- and (low-dose) efavirenz-based ART (Appendix Table A5, Figure A5).

Role of the Funding Source

Funders had no role in study design, data collection, data interpretation, or writing of this manuscript. The corresponding author had access to all data and accepts responsibility for submission of this manuscript for publication.

RESULTS

Outcomes among Women

At five years, the model projected that for women in the EFV strategy, 1,830,800 women were virologically suppressed, 658,900 had experienced severe OIs, and 276,500 women had died (Table 2). Compared to EFV, outcomes were better in the DTG strategy, which resulted in 70,400 more women being virologically suppressed, 39,700 fewer severe OIs, and 13,700 fewer deaths among women with HIV (0.44% relative decrease in mortality). Compared to EFV, WHO approach resulted in 24,900 more women virologically suppressed, while averting 14,100 severe OIs, and 4,900 deaths among women. However, all outcomes among women were better with DTG than with the WHO approach.

Table 2:

Projected five-year outcomes for the ~3.1 million women of childbearing potential who ever receive first-line ART and their children.

| EFV | DTG | WHO | DTG-EFV Outcome | WHO-EFV Outcome | DTG-WHO Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes among women | ||||||

| Women suppressed on ART | 1,830,800 | 1,901,300 | 1,855,800 | +70,400 D | +24,900 W | +45,500 D |

| Severe OIs among womena | 658,900 | 619,100 | 644,800 | −39,700 D | −14,100 W | −25,700 D |

| Deaths among womenb | 276,500 | 262,800 | 271,700 | −13,700 D | −4,900 W | −8,900 D |

| Sexual transmissions to partners | 251,800 | 194,000 | 231,300 | −57,700 D | −20,500 W | −37,300 D |

| Outcomes among children | ||||||

| Children born to women with HIV | 1,030,400 | 1,033,400 | 1,030,600 | +3,000 | +200 | +2,800 |

| Non-NTD related pediatric deaths | 90,300 | 88,300 | 90,200 | −2,100 D | −100 W | −1,900 D |

| NTDs | 500 | 6,900 | 900 | +6,400 E | +400 E | +6,000 W |

| Pediatric HIV infections | 29,800 | 22,600 | 29,300 | −7,100 D | −400 W | −6,700 D |

| Children alive and HIV-free | 921,800 | 924,700 | 921,900 | +3,000 D | +200 W | +2,800 D |

| Cumulative pediatric deathsc | 90,800 | 95,200 | 91,100 | +4,400 E | +300 E | +4,100 W |

| Combined outcomes among women and children | ||||||

| Cumulative deaths among women and children | 367,300 | 358,000 | 362,800 | −9,300 D | −4,500 W | −4,800 D |

DTG: dolutegravir strategy; EFV: efavirenz strategy; WHO: World Health Organization approach strategy; ART: antiretroviral therapy; OI: opportunistic infection; NTD: neural tube defect.

Superscript “E” indicates outcomes that favor EFV. Superscript “D” indicates outcomes that favor DTG. Superscript “W” indicates outcomes that favor WHO.

Severe OIs are defined as WHO Stage III or IV opportunistic infections or cases of tuberculosis (pulmonary or extrapulmonary). Of the OIs reported with EFV, DTG, and WHO, 232,100; 208,700; and 223,800 and were cases of tuberculosis.

The number of deaths averted among women with DTG compared with EFV (13,700) reflects a 0.44% absolute difference in mortality between strategies at five years (13,700 deaths averted / 3,099,800 total cohort size = 0.44%).

Refers to pediatric deaths over five years from all causes, including NTDs.

Transmission Outcomes

Due to higher rates of durable virologic suppression, women in DTG had 57,700 (vs. EFV) and 37,300 (vs. WHO approach) fewer projected sexual transmissions to partners over five years. Similarly, DTG averted 7,100 (vs. EFV) and 6,700 (vs. WHO approach) pediatric HIV infections.

Outcomes among Children

Reflecting differences in survival among women, DTG resulted in 3,000 more children being born than with EFV and 2,800 more than with the WHO approach over five years (Table 2). EFV led to 90,300 pediatric deaths from non-NTD causes, 500 fatal NTDs, and to 921,800 children alive and HIV-free at five years when accounting for pediatric transmissions. Compared to EFV, DTG resulted in 2,100 fewer non-NTD related deaths and 6,400 more projected NTDs; overall, 3,000 more children were alive and HIV-free at five years. Pediatric outcomes with WHO approach closely resembled those of EFV, since most conceptions in the WHO approach strategy occurred among women on EFV.

Over five years, DTG led to 4,400 more pediatric deaths than EFV, and 4,100 more than the WHO approach. Although EFV led to 4,400 fewer pediatric deaths than DTG, DTG led to 3.1-fold fewer deaths among women (13,700).

Sensitivity Analyses

Univariate

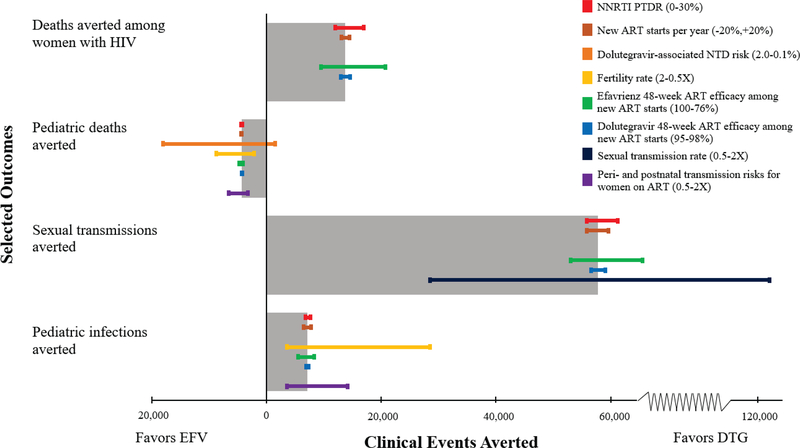

Even when using the highest levels of 48-week ART efficacy of efavirenz observed in clinical trials among new ART starts (100% efficacy) (63), DTG still resulted in 9,470 fewer deaths among women with HIV and 53,100 fewer sexual transmissions compared to EFV (Figure 1, green bars). Conversely, with increased NNRTI PTDR to 30%, DTG averted more deaths among women (16,900) and sexual transmissions (61,200) than in the base case (Figure 1, red bars).

Figure 1: Univariate sensitivity analysis of EFV vs. DTG strategies.

Tornado diagram of model-based outcomes for the comparison of EFV and DTG. The WHO approach outcomes represent a weighted average of the EFV and DTG strategies, and are depicted in Appendix Figures A3 and A4. On the vertical axis, each bar represents a different clinical outcome examined, where the length of the bar indicates the absolute number of clinical events averted in the base case, as indicated on the horizontal axis. Bars that extend to the left of the origin indicate situations where there would be a preference, based on the outcome examined, for an efavirenz-based regimen among women of childbearing potential. Bars that extend to the right of the origin indicate situations where there would be a preference for a dolutegravir-based regimen. Thin colored bars demonstrate the changes in each of these outcomes averted when key parameters are varied in univariate sensitivity analyses. The color of the bars indicates which sensitivity analysis is conducted. The range examined in each sensitivity analysis is displayed in the legend in the upper right with the value that most favors EFV on the left and the value that most favors DTG on the right. EFV: efavirenz strategy, DTG: dolutegravir strategy, NNRTI: non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, PTDR: pre-treatment drug resistance, ART: antiretroviral therapy, NTD: neural tube defect.

The dolutegravir-associated NTD risk and the fertility rate (orange and yellow bars) most influenced pediatric mortality. At a dolutegravir-associated NTD risk of <0.24%, there were fewer overall pediatric deaths with DTG than EFV due to fewer pediatric HIV transmissions and associated HIV-related pediatric mortality (orange bar). At the highest dolutegravir-associated NTD risk examined (2.0%), EFV averted 18,100 pediatric deaths compared to DTG (orange bar).

Multivariate

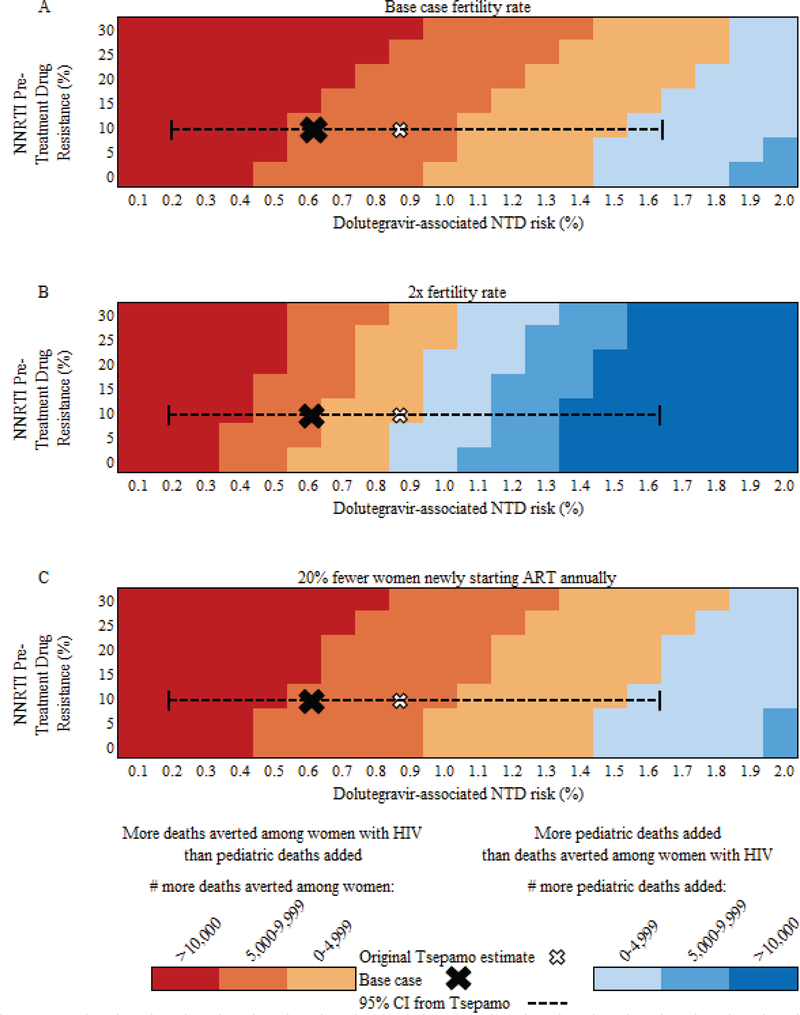

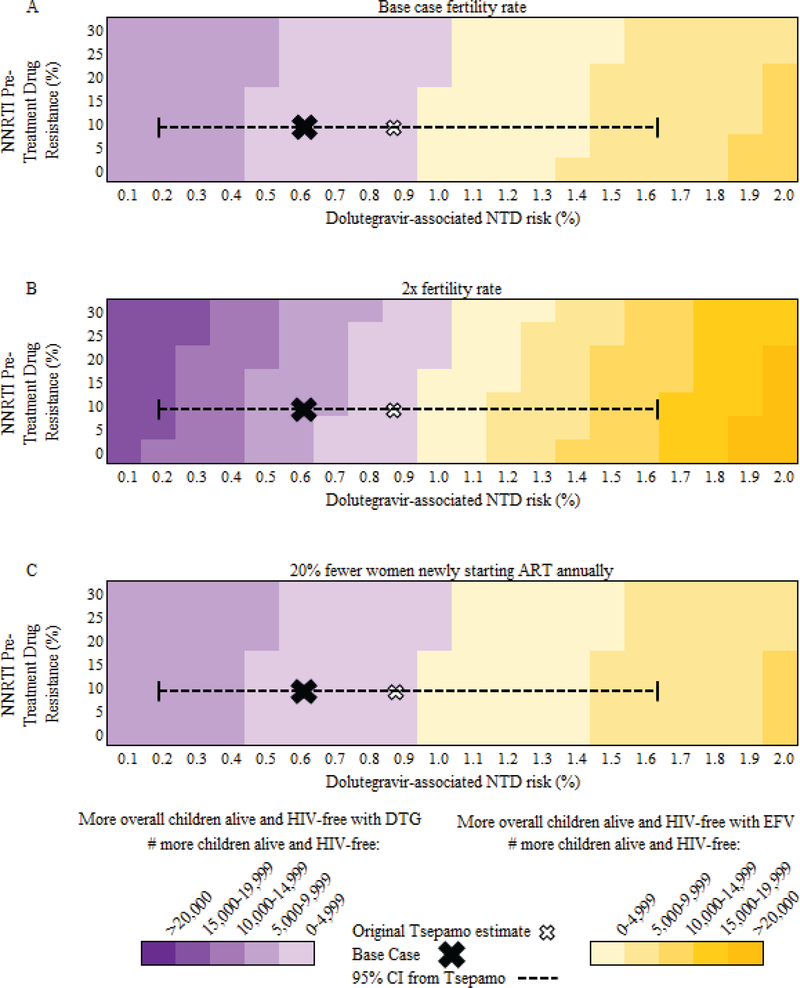

When considering the trade-off between women’s and pediatric mortality, at base case values, deaths averted among women with HIV exceeded pediatric deaths added in DTG compared to EFV regardless of NNRTI PTDR, as long as the dolutegravir-associated NTD risk was ≤1.5% (Figure 2A). At fertility rates twice that of South Africa – as in Tanzania or Uganda (64) – the impact of NTD risk increased (Figure 2B) with deaths averted among women with HIV exceeding additional pediatric deaths in DTG compared to EFV at all values of NNRTI PTDR only if dolutegravir-associated NTD risks were ≤0.8%. If 20% fewer women newly started ART (175,400 annually), the relative impact of NNRTI PTDR decreased (Figure 2C). Considering only pediatric outcomes, with base case NNRTI PTDR, more children were alive and HIV-free with DTG compared to EFV unless the dolutegravir-associated NTD risk was ≥1.0%, irrespective of fertility rates or the number of women newly starting ART each year (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Multivariate sensitivity analyses of DTG vs. EFV: Pediatric deaths added vs. deaths averted among women with HIV.

Multivariate sensitivity analysis of the impact of NNRTI pre-treatment drug resistance (PTDR, vertical axis) and dolutegravir-associated NTD risk (horizontal axis) on the number of deaths among women with HIV on ART and their children over a five-year period in South Africa. The base case estimate, with 10.7% NNRTI PTDR and the dolutegravir-associated NTD risk of 0.67% from Tsepamo, is indicated by the X on each figure; the hollow white X indicates the point estimates first reported from the Tsepamo study. Dotted lines indicate the current 95% confidence interval around the dolutegravir-associated NTD risk from the Tsepamo study. Areas shaded in tan to red tones indicate where deaths averted among women with HIV exceed pediatric deaths added (including both NTDs and pediatric HIV-related deaths) in the DTG strategy relative to the EFV strategy; darker red shades indicate an increasing number of excess deaths averted among women with HIV. Areas shaded in blue tones indicate where pediatric deaths added exceed deaths averted among women with HIV in the DTG strategy; darker blue shades indicate an increasing number of added pediatric deaths. Panel A provides results for the base case, Panel B provides results for a fertility rate twice that of the base case, and Panel C provides results for 20% fewer women newly starting ART annually. NNRTI: non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, NTD: neural tube defect, ART: antiretroviral therapy, PTDR: pre-treatment drug resistance, DTG: dolutegravir strategy, EFV: efavirenz strategy.

Figure 3: Multivariate sensitivity analyses of DTG vs. EFV: Number of children alive and HIV-free.

Multivariate sensitivity analysis of the impact of NNRTI pre-treatment drug resistance (PTDR, vertical axis) and dolutegravir-associated NTD risk (horizontal axis) on HIV-free survival among HIV-exposed children born to women on ART over a five-year period in South Africa. The base case estimate is indicated by the X on each figure; the hollow X indicates point estimates as first reported from the Tsepamo study. Dotted lines indicate the current 95% confidence interval around the dolutegravir-associated NTD risk from the Tsepamo study. Areas shaded in purple tones indicate where there are more children alive and HIV-free with DTG than EFV; darker purple shades indicate an increasing excess of children alive and HIV-free with DTG. Areas shaded in yellow tones indicate where there are more children alive and HIV-free with EFV than DTG; darker yellow shades indicate an increasing excess of children alive and HIV-free with EFV. Panel A provides results for the base case, Panel B provides results for a fertility rate twice that of the base case, and Panel C provides results for 20% fewer women newly starting ART annually. NNRTI: non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, PTDR: pre-treatment drug resistance, NTD: neural tube defect, ART: antiretroviral therapy, DTG: dolutegravir strategy, EFV: efavirenz strategy.

The NAMSAL Scenario

Using equal dolutegravir and efavirenz efficacy data from the NAMSAL trial, DTG still averted 6,500 deaths among women and 42,600 sexual transmissions when compared to EFV, but fewer than in the base case (Appendix Table A5). However, DTG still averted 1.3-fold more deaths among women (6,500) than pediatric deaths added (4,900) when compared to EFV. The WHO approach resulted in similar numbers of NTDs, but fewer deaths among women than in the base case, leading to 400 (vs. DTG) and 2,100 (vs. EFV) fewer cumulative deaths among women and children.

DISCUSSION

Recent reports of an increased risk of NTDs in children born to women receiving dolutegravir-based ART at conception raised questions about the best choice of ART for women of childbearing potential. This model-based analysis suggests that a policy that provides efavirenz rather than dolutegravir to women of childbearing potential in South Africa will result in an additional 13,700 deaths among women with HIV, over 39,700 more OIs, and more than 60,000 additional HIV transmissions (including 7,100 pediatric HIV infections) over the next five years, while averting approximately 6,400 neural tube defects. We projected that there would be over three-fold more deaths added among women than pediatric deaths averted with adoption of an efavirenz for all compared with a dolutegravir for all policy. In assessing the relative number of deaths among women with HIV and deaths among children, NTD risks on dolutegravir would need to exceed 1.4% for pediatric deaths added to surpass deaths averted among women with HIV.

We also examined the WHO approach, offering either efavirenz or dolutegravir based on women’s reliable access to contraception. Compared to using dolutegravir for all women of childbearing potential, we find that while the current WHO guidance would reduce deaths among children by 4,100, due primarily to prevention of NTDs, it would still result in over 8,000 more deaths among women. However, our analysis did not account for the logistical challenges of the WHO approach where two ART “alternatives” would need to be stocked and accessible (5). “Harmonization” of HIV regimens – using the same drugs for nearly all people – has markedly improved access to ART worldwide, ensured a more stable drug supply, simplified treatment so that ART can be provided by various cadres of healthcare workers, and facilitated equal treatment access among men and women (5).

The most critical unknown parameter is the risk of NTDs in children born to women taking dolutegravir at conception. The preliminary point estimates from the Tsepamo study reflect either the first description of a major problem or a chance statistical fluctuation that will not be later confirmed. It will take time to distinguish these possibilities empirically; in the interim, model-based analyses reflect the best opportunity to understand the implications of this information at a population level. More than 500 additional women who conceived on dolutegravir will deliver in the next year; even if no NTDs are observed, the cumulative NTD risk would still exceed the 0.05–0.1% observed among those taking other ART regimens or not living with HIV (6, 8, 9). Expanding pharmacovigilance and birth surveillance programs is a vital research priority to inform this uncertainty (65).

Another key uncertainty is the effectiveness of dolutegravir-based ART in resource-limited settings. With escalating rates of NNRTI PTDR to >10% in sub-Saharan Africa, and >18% in some areas of South Africa, widespread use of dolutegravir through a public health approach is likely to offer improved virologic suppression compared to efavirenz (27, 66). However, the NAMSAL study recently reported no statistically significant difference in 48-week virologic suppression (HIV RNA <50 c/mL) between dolutegravir-based and low-dose efavirenz-based ART in Cameroon (62). We found that even with equal 48-week ART efficacy for new ART starts, dolutegravir resulted in fewer projected deaths among women and sexual transmissions over five years than with efavirenz. This benefit was observed primarily among those who are currently on first-line efavirenz-based ART, but not virologically suppressed. Data from ongoing trials comparing the efficacy of dolutegravir and efavirenz in resource-limited settings will further clarify the health tradeoffs between these regimens (67–69).

We have presented a quantitative analysis of outcomes for women of childbearing potential with HIV, their sexual partners, and their children. We intentionally provide separate results for women and for children, rather than providing a measure of combined life-years, to allow for broad and nuanced interpretation of how these results might be weighed. Balancing of values attributed to women and their children is the topic of much discussion and requires considerations which are highly individualized, context-specific, and not easily quantified (70). Data about prioritization of the health of a pregnant woman compared to that of her own child have charged many policy debates, including in HIV (65, 71, 72). Because of the visible and catastrophic nature of NTDs, individuals, clinicians, and policy makers all seek to prevent these birth defects. Meanwhile, fear of adverse birth outcomes should be balanced against other important outcomes associated with providing less effective medications to women who may become pregnant. We project absolute differences in deaths among women between the ART policy approaches; small relative differences in individual mortality are magnified by the large number of women at risk. For each woman with HIV making an informed decision about her choice of ART, the balance of risks and benefits of dolutegravir will depend upon her individual preferences and circumstances.

Fertility rates are lower in South Africa than in many other African settings, as a variety of effective contraception options are provided through the public sector, and 58% of sexually active women use at least one such option (23, 64). Even so, approximately half of pregnancies among women with HIV in South Africa are unplanned, a figure that rises to as high as 65% in other areas of sub-Saharan Africa with more limited access to effective contraception (13, 23). The WHO proposes that women of childbearing potential with “consistent and reliable contraception” can use dolutegravir (1). We found that the relative benefits of implementing dolutegravir compared to efavirenz for women of childbearing potential would likely be attenuated in settings with higher fertility rates and poorer access to reproductive health services, where more total births could result in more neural tube defects.

As with all model-based analyses, there is uncertainty inherent in long-term projections. We assume that trends in HIV prevalence, ART uptake, and fertility will remain relatively consistent over the five-year horizon; policy conclusions, however, are robust to sensitivity analyses varying these parameters. This analysis considers the current, conservative prevalence of NNRTI PTDR; if transmitted drug resistance increases as anticipated (27), we would expect greater relative benefits for women and fewer relative pediatric HIV infections with dolutegravir-based ART than with efavirenz-based ART. We did not model the engagement in care of young women separately from older women; the behavioral characteristics and use of contraception in these unique subpopulations are unlikely to differ substantially by ART regimen. Our projections account for deaths among women over a five-year horizon, but not for subsequent deaths among any sexual partners who become HIV-infected; inclusion of deaths related to sexual transmission of HIV over a lifetime would further favor dolutegravir. We also did not assess the drug interactions of efavirenz with hormonal contraception (73). Finally, and most critically, it is too early to know whether the signal of an increased risk of NTDs associated with dolutegravir will be borne out over time. We evaluated the impact of this key uncertainty as the crux of our analysis.

With a recent report of NTDs associated with dolutegravir at the time of conception, decisions must now be made about expanding the use of dolutegravir-based regimens worldwide. Further data on the impact of dolutegravir use during conception on infants will be forthcoming. In the meantime, as ART policies continue to be re-evaluated, our analysis shows that compared with efavirenz (or the WHO approach), using dolutegravir for all women of childbearing potential would avert over three-fold more deaths among women with HIV than pediatric deaths added in South Africa, despite the current NTD occurrence with dolutegravir. These results argue against a blanket policy of favoring efavirenz over dolutegravir in women of childbearing potential. Rather, this study supports an open, context-specific discussion about the trade-offs between risks of harms and benefits of these treatment options.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Taige Hou, the CEPAC software engineer, for his significant contributions to the CEPAC models. We also gratefully acknowledge the CEPAC-Pediatric and CEPAC-International research teams for their role in model development and revisions.

Sources of Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health through the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease [T32 AI007433, R37 AI058736, R01 AI042006, R37 AI093269], the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development [R01 HD079214], and the Steve and Deborah Gorlin Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Research Scholars Award. This research was funded in part by a 2017 developmental grant from the Harvard University Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH funded program (P30 AI060354) which is supported by the following NIH co-funding and participating Institutes and Centers: NIAID, NCI, NICHD, NIDCR, NHLBI, NIDA, NIMH, NIA, NIDDK, NIGMS, NIMHD, FIC, and OAR. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or MGH.

Funding Source: National Institutes of Health - National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Massachusetts General Hospital, and Harvard University Center for AIDS Research

Footnotes

REPRODUCIBLE RESEARCH STATEMENT

Study protocol: N/A

Sample model code: CEPAC Website: https://www.massgeneral.org/mpec/cepac/

Data set: Comprehensive ART efficacy data derivations and model inputs are available in the Appendix

Conflicts of Interest: EJA participated in a Glaxo Smith Kline global pediatric advisory group. PES has received research funding from Gilead and ViiV Healthcare/Glaxo Smith Kline (GSK), and is on the Scientific Advisory Boards of Gilead, Janssen, Merck, and ViiV Healthcare/GSK. All other authors have no conflicts of interest.

Ethics: This study was approved by the Partners Healthcare Human Subjects Committee, Boston, MA, USA.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Updated recommendations on first-line and second-line antiretroviral regimens and post-exposure prophylaxis and recommendations on early infant diagnosis of HIV. Geneva, Switzerland; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walmsley SL, Antela A, Clumeck N, Duiculescu D, Eberhard A, Gutierrez F, et al. Dolutegravir plus abacavir-lamivudine for the treatment of HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(19):1807–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kanters S, Vitoria M, Doherty M, Socias ME, Ford N, Forrest JI, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of first-line antiretroviral therapy for the treatment of HIV infection: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet HIV. 2016;3(11):e510–e20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clinton Health Access Initiative. New high-quality antiretroviral therapy to be launched in South Africa, Kenya and over 90 low- and middle-income countries at reduced price. Accessed at https://clintonhealthaccess.org/new-high-quality-antiretroviral-therapy-launched-south-africa-kenya-90-low-middle-income-countries-reduced-price/ on November 10, 2018.

- 5.World Health Organization. Transition to new antiretroviral drugs in HIV programmes: Clinical and programmatic considerations. 2017.

- 6.Zash R, Makhema J, Shapiro RL. Neural-tube defects with dolutegravir treatment from the time of conception. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(10):979–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Potential safety issue affecting women living with HIV using dolutegravir at the time of conception. 2018.

- 8.Zash R Surveillance for neural tube defects following antiretroviral exposure from conception. AIDS 2018. Amsterdam, Netherlands; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blencowe H, Kancherla V, Moorthie S, Darlison MW, Modell B. Estimates of global and regional prevalence of neural tube defects for 2015: a systematic analysis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2018;1414(1):31–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Attia S, Egger M, Muller M, Zwahlen M, Low N. Sexual transmission of HIV according to viral load and antiretroviral therapy: systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2009;23(11):1397–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mandelbrot L, Tubiana R, Le Chenadec J, Dollfus C, Faye A, Pannier E, et al. No perinatal HIV-1 transmission from women with effective antiretroviral therapy starting before conception. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(11):1715–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Afnan-Holmes H, Magoma M, John T, Levira F, Msemo G, Armstrong CE, et al. Tanzania’s countdown to 2015: an analysis of two decades of progress and gaps for reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health, to inform priorities for post-2015. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3(7):e396–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iyun V, Brittain K, Phillips TK, le Roux S, McIntyre JA, Zerbe A, et al. Prevalence and determinants of unplanned pregnancy in HIV-positive and HIV-negative pregnant women in Cape Town, South Africa: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(4):e019979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCoy SI, Buzdugan R, Ralph LJ, Mushavi A, Mahomva A, Hakobyan A, et al. Unmet need for family planning, contraceptive failure, and unintended pregnancy among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women in Zimbabwe. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e105320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vitoria M WHO guidance on the use of TLD: The who, why, and how of transitioning patients. AIDS 2018. Amsterdam, Netherlands; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walensky RP, Borre ED, Bekker LG, Resch SC, Hyle EP, Wood R, et al. The anticipated clinical and economic effects of 90–90-90 in South Africa. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(5):325–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walensky RP, Ross EL, Kumarasamy N, Wood R, Noubary F, Paltiel AD, et al. Cost-effectiveness of HIV treatment as prevention in serodiscordant couples. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(18):1715–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walensky RP, Borre ED, Bekker LG, Hyle EP, Gonsalves GS, Wood R, et al. Do less harm: evaluating HIV programmatic alternatives in response to cutbacks in foreign aid. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(9):618–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dunning L, Francke JA, Mallampati D, MacLean RL, Penazzato M, Hou T, et al. The value of confirmatory testing in early infant HIV diagnosis programmes in South Africa: A cost-effectiveness analysis. PLoS Med. 2017;14(11):e1002446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ciaranello AL, Morris BL, Walensky RP, Weinstein MC, Ayaya S, Doherty K, et al. Validation and calibration of a computer simulation model of pediatric HIV infection. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e83389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). AIDSInfo. Accessed at http://aidsinfo.unaids.org on August 9, 2018. [PubMed]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control. Effectiveness of family planning methods. Accessed at https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/contraception/unintendedpregnancy/pdf/Contraceptive_methods_508.pdf on November 10, 2018.

- 23.South Africa National Department of Health Demographic and Health Survey. Key indicators report. Pretoria, South Africa: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bor J, Ahmed S, Fox MP, Rosen S, Meyer-Rath G, Katz IT, et al. Effect of eliminating CD4-count thresholds on HIV treatment initiation in South Africa: An empirical modeling study. PLoS One. 2017;12(6):e0178249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaplan SR, Oosthuizen C, Stinson K, Little F, Euvrard J, Schomaker M, et al. Contemporary disengagement from antiretroviral therapy in Khayelitsha, South Africa: A cohort study. PLoS Med. 2017;14(11):e1002407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treatment and preventing HIV infection. 2016. [PubMed]

- 27.World Health Organization. HIV Drug Resistance Report 2017.

- 28.Cohen CJ, Molina JM, Cahn P, Clotet B, Fourie J, Grinsztejn B, et al. Efficacy and safety of rilpivirine (TMC278) versus efavirenz at 48 weeks in treatment-naive HIV-1-infected patients: pooled results from the phase 3 double-blind randomized ECHO and THRIVE Trials. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60(1):33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lennox JL, DeJesus E, Lazzarin A, Pollard RB, Madruga JV, Berger DS, et al. Safety and efficacy of raltegravir-based versus efavirenz-based combination therapy in treatment-naive patients with HIV-1 infection: a multicentre, double-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;374(9692):796–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gallant JE, DeJesus E, Arribas JR, Pozniak AL, Gazzard B, Campo RE, et al. Tenofovir DF, emtricitabine, and efavirenz vs. zidovudine, lamivudine, and efavirenz for HIV. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(3):251–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trottier B, Lake JE, Logue K, Brinson C, Santiago L, Brennan C, et al. Dolutegravir/abacavir/lamivudine versus current ART in virally suppressed patients (STRIIVING): a 48-week, randomized, non-inferiority, open-label, Phase IIIb study. Antivir Ther. 2017;22(4):295–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sax PE, Pozniak A, Montes ML, Koenig E, DeJesus E, Stellbrink HJ, et al. Coformulated bictegravir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir alafenamide versus dolutegravir with emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide, for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection (GS-US-380–1490): a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2017;390(10107):2073–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Orrell C, Hagins DP, Belonosova E, Porteiro N, Walmsley S, Falco V, et al. Fixed-dose combination dolutegravir, abacavir, and lamivudine versus ritonavir-boosted atazanavir plus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine in previously untreated women with HIV-1 infection (ARIA): week 48 results from a randomised, open-label, non-inferiority, phase 3b study. Lancet HIV. 2017;4(12):e536–e46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gatell JM, Assoumou L, Moyle G, Waters L, Johnson M, Domingo P, et al. Switching from a ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitor to a dolutegravir-based regimen for maintenance of HIV viral suppression in patients with high cardiovascular risk. AIDS. 2017;31(18):2503–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Post FA, Moyle GJ, Stellbrink HJ, Domingo P, Podzamczer D, Fisher M, et al. Randomized comparison of renal effects, efficacy, and safety with once-daily abacavir/lamivudine versus tenofovir/emtricitabine, administered with efavirenz, in antiretroviral-naive, HIV-1-infected adults: 48-week results from the ASSERT study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55(1):49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raffi F, Rachlis A, Stellbrink HJ, Hardy WD, Torti C, Orkin C, et al. Once-daily dolutegravir versus raltegravir in antiretroviral-naive adults with HIV-1 infection: 48 week results from the randomised, double-blind, non-inferiority SPRING-2 study. Lancet. 2013;381(9868):735–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Armenia D, Di Carlo D, Calcagno A, Vendemiati G, Forbici F, Bertoli A, et al. Pre-existent NRTI and NNRTI resistance impacts on maintenance of virological suppression in HIV-1-infected patients who switch to a tenofovir/emtricitabine/rilpivirine single-tablet regimen. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72(3):855–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li JZ, Paredes R, Ribaudo HJ, Svarovskaia ES, Metzner KJ, Kozal MJ, et al. Low-frequency HIV-1 drug resistance mutations and risk of NNRTI-based antiretroviral treatment failure: a systematic review and pooled analysis. JAMA. 2011;305(13):1327–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lim C, McFaul K, Kabagambe S, Sonecha S, Jones R, Asboe D, et al. Comparison of efavirenz and protease inhibitor based combination antiretroviral therapy regimens in treatment-naive people living with HIV with baseline resistance. AIDS. 2016;30(11):1849–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lockman S, Hughes MD, McIntyre J, Zheng Y, Chipato T, Conradie F, et al. Antiretroviral therapies in women after single-dose nevirapine exposure. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(16):1499–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cahn P, Pozniak AL, Mingrone H, Shuldyakov A, Brites C, Andrade-Villanueva JF, et al. Dolutegravir versus raltegravir in antiretroviral-experienced, integrase-inhibitor-naive adults with HIV: week 48 results from the randomised, double-blind, non-inferiority SAILING study. Lancet. 2013;382(9893):700–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aboud M, Kaplan R, Lombaard J, Zhang F, Hidalgo J, Mamedova E, et al. Superior efficacy of dolutegravir (DTG) plus 2 nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) compared with lopinavir/ritonavir (LPV/r) plus 2 NRTIs in second-line treatment - 48-week data from the DAWNING Study. AIDS 2018. Amsterdam, Netherlands; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paton NI, Kityo C, Hoppe A, Reid A, Kambugu A, Lugemwa A, et al. Assessment of second-line antiretroviral regimens for HIV therapy in Africa. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(3):234–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fox MP, Berhanu R, Steegen K, Firnhaber C, Ive P, Spencer D, et al. Intensive adherence counselling for HIV-infected individuals failing second-line antiretroviral therapy in Johannesburg, South Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2016;21(9):1131–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoffmann CJ, Charalambous S, Sim J, Ledwaba J, Schwikkard G, Chaisson RE, et al. Viremia, resuppression, and time to resistance in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) subtype C during first-line antiretroviral therapy in South Africa. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(12):1928–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McCluskey SM, Boum Y 2nd, Musinguzi N, Haberer JE, Martin JN, Hunt PW, et al. Brief report: appraising viral load thresholds and adherence support recommendations in the World Health Organization guidelines for detection and management of virologic failure. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;76(2):183–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shet A, Neogi U, Kumarasamy N, DeCosta A, Shastri S, Rewari BB. Virological efficacy with first-line antiretroviral treatment in India: predictors of viral failure and evidence of viral resuppression. Trop Med Int Health. 2015;20(11):1462–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hermans LE, Tempelman H, Carmona S, Nijhuis M, Grobbee D, Richman DD, et al. High rates of viral resuppression on first-line ART after initial virological failure. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections Boston, MA; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Holmes KK, Levine R, Weaver M. Effectiveness of condoms in preventing sexually transmitted infections. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82(6):454–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chetty T, Carter RJ, Bland RM, Newell ML. HIV status, breastfeeding modality at 5 months and postpartum maternal weight changes over 24 months in rural South Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2014;19(7):852–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mnyani CN, Tait CL, Armstrong J, Blaauw D, Chersich MF, Buchmann EJ, et al. Infant feeding knowledge, perceptions and practices among women with and without HIV in Johannesburg, South Africa: a survey in healthcare facilities. Int Breastfeed J. 2016;12:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Myer L, Phillips TK, Zerbe A, Brittain K, Lesosky M, Hsiao NY, et al. Integration of postpartum healthcare services for HIV-infected women and their infants in South Africa: A randomised controlled trial. PLoS Medicine. 2018;15(3):e1002547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Myer L, Phillips TK, McIntyre JA, Hsiao NY, Petro G, Zerbe A, et al. HIV viraemia and mother-to-child transmission risk after antiretroviral therapy initiation in pregnancy in Cape Town, South Africa. HIV Med. 2017;18(2):80–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Townsend CL, Byrne L, Cortina-Borja M, Thorne C, de Ruiter A, Lyall H, et al. Earlier initiation of ART and further decline in mother-to-child HIV transmission rates, 2000–2011. AIDS. 2014;28(7):1049–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fawzi W, Msamanga G, Spiegelman D, Renjifo B, Bang H, Kapiga S, et al. Transmission of HIV-1 through breastfeeding among women in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;31(3):331–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Petra Study Team. Efficacy of three short-course regimens of zidovudine and lamivudine in preventing early and late transmission of HIV-1 from mother to child in Tanzania, South Africa, and Uganda (Petra study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet. 2002;359(9313):1178–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thior I, Lockman S, Smeaton LM, Shapiro RL, Wester C, Heymann SJ, et al. Breastfeeding plus infant zidovudine prophylaxis for 6 months vs formula feeding plus infant zidovudine for 1 month to reduce mother-to-child HIV transmission in Botswana: a randomized trial: the Mashi Study. JAMA. 2006;296(7):794–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gill MM, Hoffman HJ, Ndatimana D, Mugwaneza P, Guay L, Ndayisaba GF, et al. 24-month HIV-free survival among infants born to HIV-positive women enrolled in Option B+ program in Kigali, Rwanda: The Kabeho Study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(51):e9445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ngoma MS, Misir A, Mutale W, Rampakakis E, Sampalis JS, Elong A, et al. Efficacy of WHO recommendation for continued breastfeeding and maternal cART for prevention of perinatal and postnatal HIV transmission in Zambia. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18:19352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Iliff PJ, Piwoz EG, Tavengwa NV, Zunguza CD, Marinda ET, Nathoo KJ, et al. Early exclusive breastfeeding reduces the risk of postnatal HIV-1 transmission and increases HIV-free survival. AIDS. 2005;19(7):699–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi LC, Zuma K, Jooste S, Zungu N, Labadarios D, Onoya D et al. South African national HIV prevalence, incidence and behaviour survey, 2012. Cape Town: HSRC Press; 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cournil A, Kouanfack C, Eymard-Duvernay S, Lem S, Mpoudi-Ngole M, Omgba P, et al. Dolutegravir- versus an efavirenz 400mg-based regimen for the initial treatment of HIV-infected patients in Cameroon: 48-week efficacy results of the NAMSAL ANRS 12313 trial. HIV Drug Therapy 2018. Glasgow, UK; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Albini L, Cesana BM, Motta D, Foca E, Gotti D, Calabresi A, et al. A randomized, pilot trial to evaluate glomerular filtration rate by creatinine or cystatin C in naive HIV-infected patients after tenofovir/emtricitabine in combination with atazanavir/ritonavir or efavirenz. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;59(1):18–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.The World Bank. Fertility rate, total (births per woman) Accessed at https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TFRT.IN?locations=US&name_desc=true on June 18, 2018.

- 65.Rasmussen SA, Barfield W, Honein MA. Protecting mothers and babies - a delicate balancing act. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(10):907–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Communicable Dis Communiqué. Prospective sentinel surveillance of human immunodeficiency virus–related drug resistance http://nicd.ac.za/assets/files/NICD%20Communicable%20Diseases%20Communique_Mar2016_final.pdf.

- 67.Waitt C Dolutegravir in pregnant HIV mothers and their neonates (DolPHIN-2). Accessed at ClinicalTrials.gov at https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03249181?term=dolphin-2&cond=dolutegravir&rank=1 on November 20, 2018.

- 68.Venter F ADVANCE study of DTG + TAF + FTC vs DTG + TDF + FTC and EFV + TDF+FTC in first-line antiretroviral therapy (ADVANCE). Accessed at ClinicalTrials.gov at https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03122262?term=ADVANCE&cond=dolutegravir&rank=1 on November 20, 2018.

- 69.National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Evaluating the efficacy and safety of dolutegravir-containing versus efavirenz-containing antiretroviral therapy regimens in HIV-1-infected pregnant women and their infants (VESTED). Accessed at https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03048422?term=vested&cond=dolutegravir&rank=1 on November 20, 2018.

- 70.Goldhaber-Fiebert JD, Brandeau ML. Evaluating cost-effectiveness of interventions that affect fertility and childbearing: how health effects are measured matters. Med Decis Making. 2015;35(7):818–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bayer R Ethical challenges posed by zidovudine treatment to reduce vertical transmission of HIV. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(18):1223–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Macklin R Enrolling pregnant women in biomedical research. Lancet. 2010;375(9715):632–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sevinsky H, Eley T, Persson A, Garner D, Yones C, Nettles R, et al. The effect of efavirenz on the pharmacokinetics of an oral contraceptive containing ethinyl estradiol and norgestimate in healthy HIV-negative women. Antivir Ther. 2011;16(2):149–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.